Submitted:

30 March 2024

Posted:

01 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. The Nucleoid as a Low-Density Structure

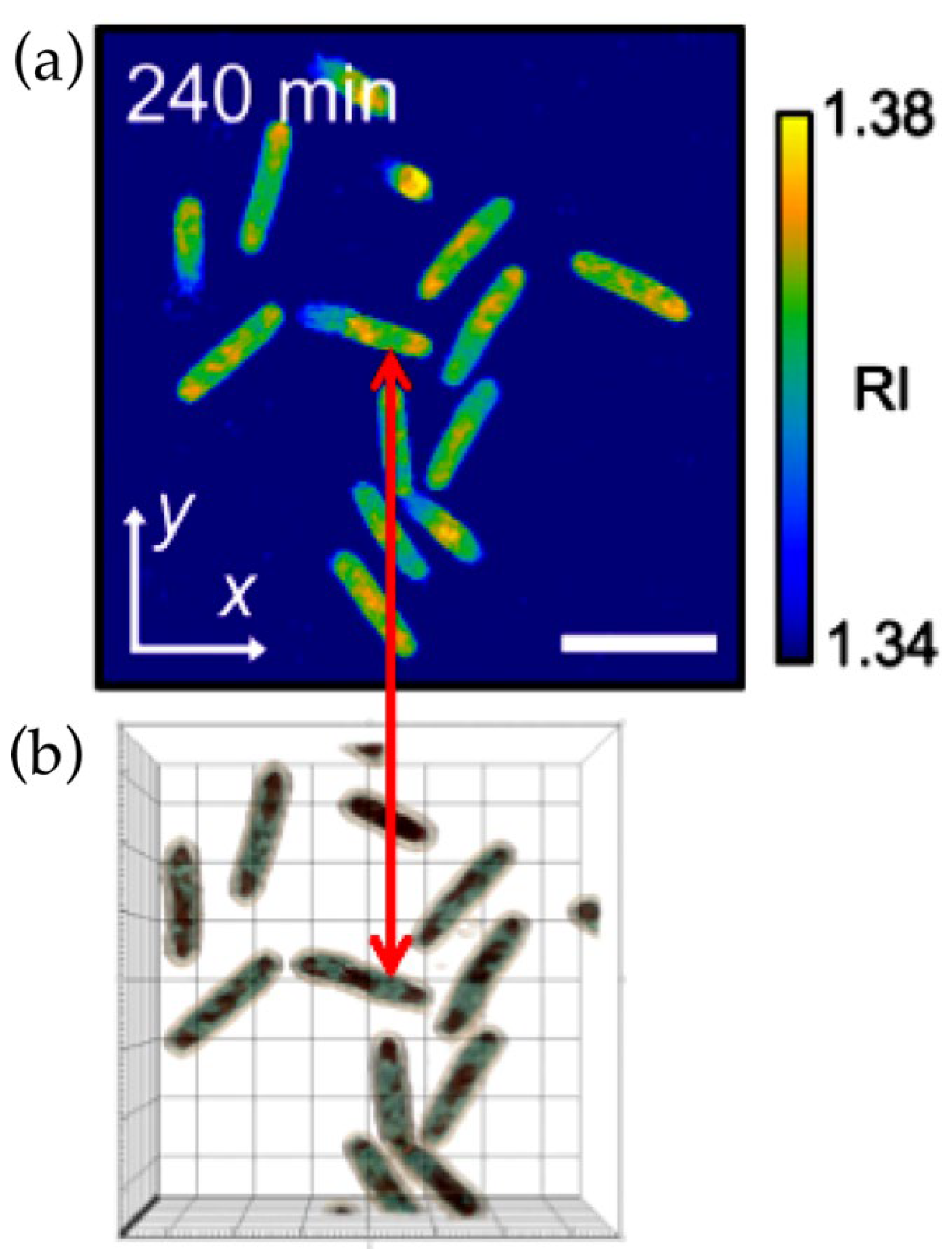

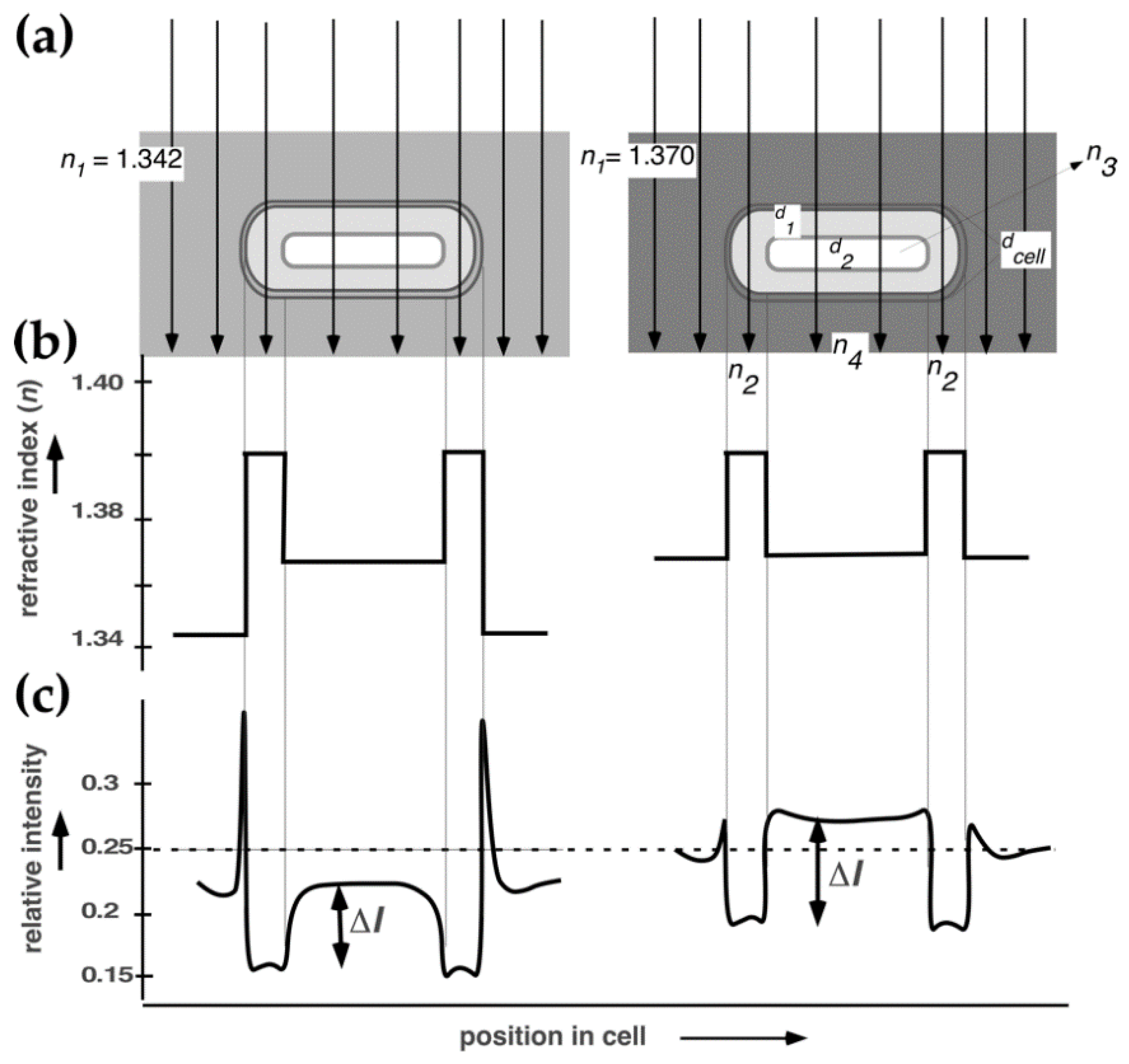

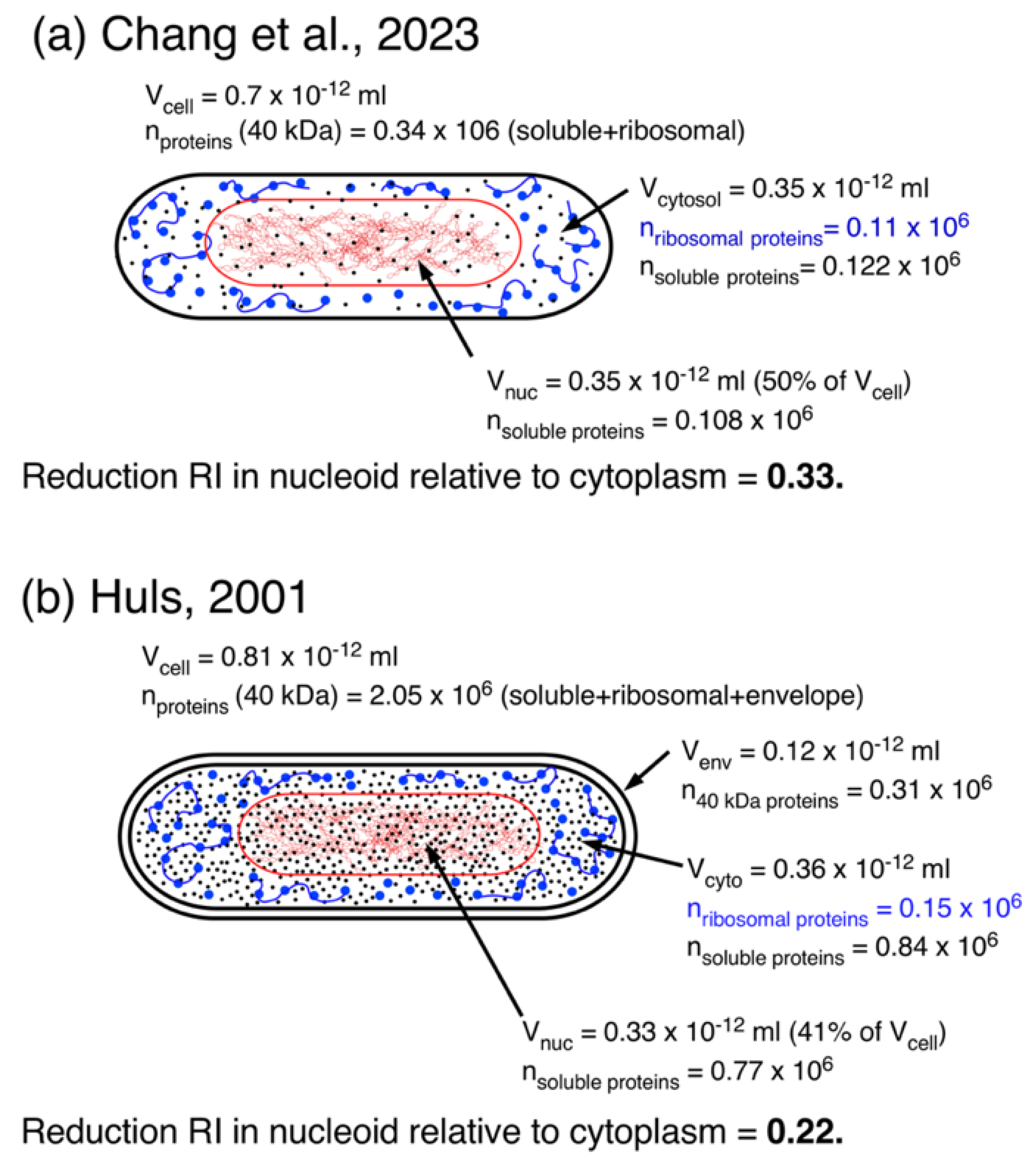

2.1. Immersive Refractometry

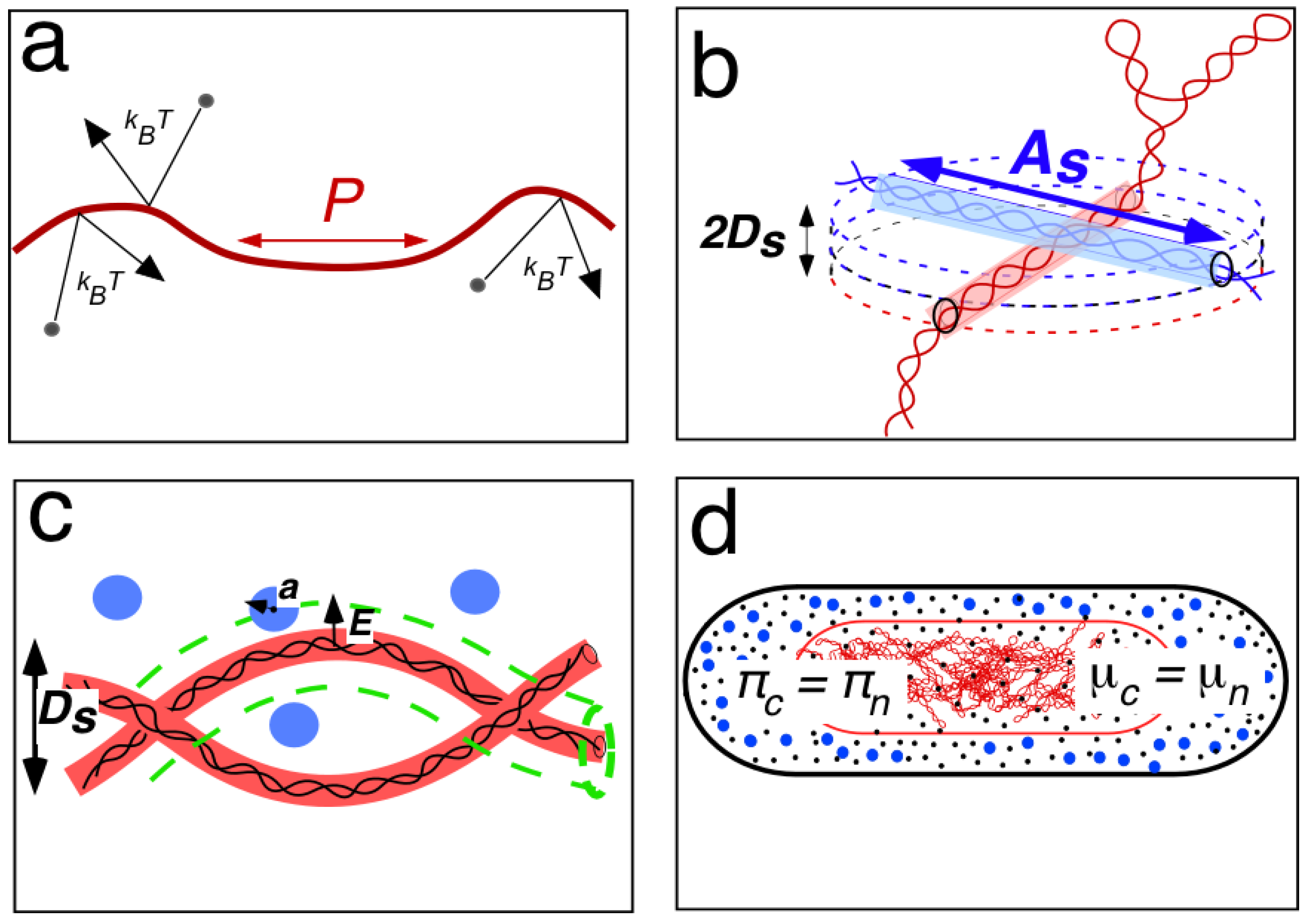

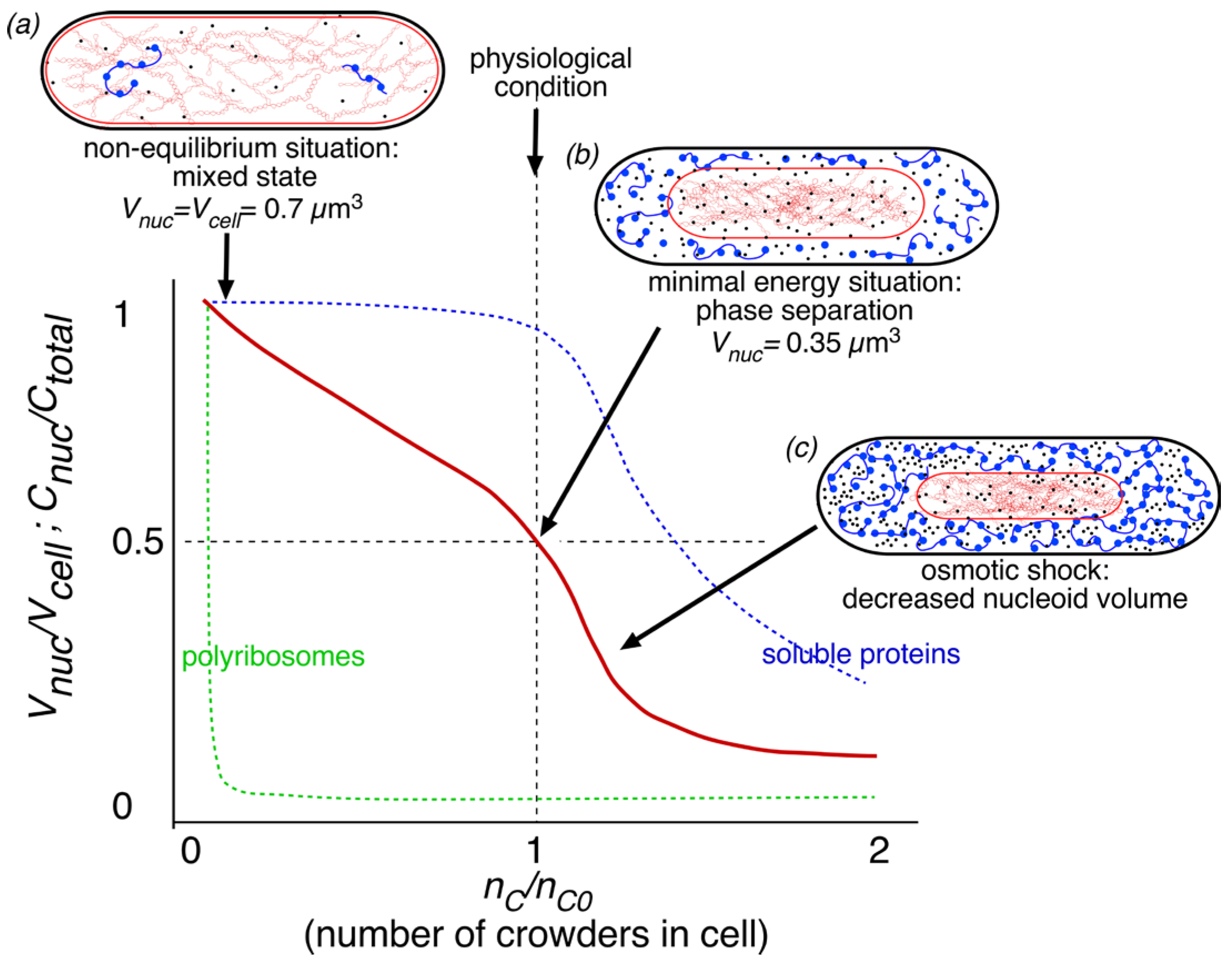

2.2. Polymer-Physical Explanation of a Low-Density Nucleoid by Odijk’s Depletion Theory

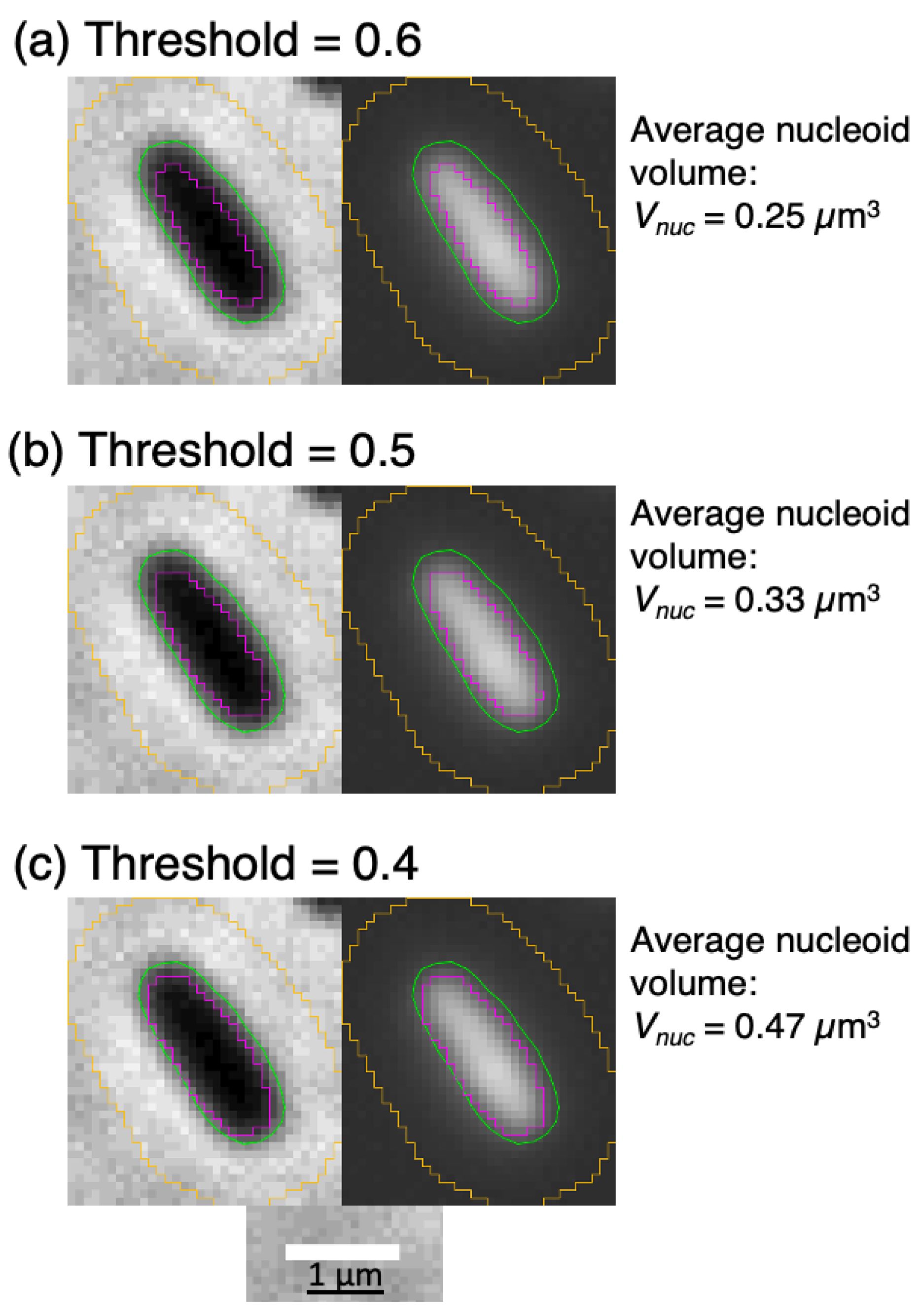

2.3. Fluorescence Microscopy: New Estimates of Nucleoid Volume

3. Different Views on DNA Compaction

3.1. Compaction through Polyribosome Exclusion

3.2. Compaction through Transcriptional Activities

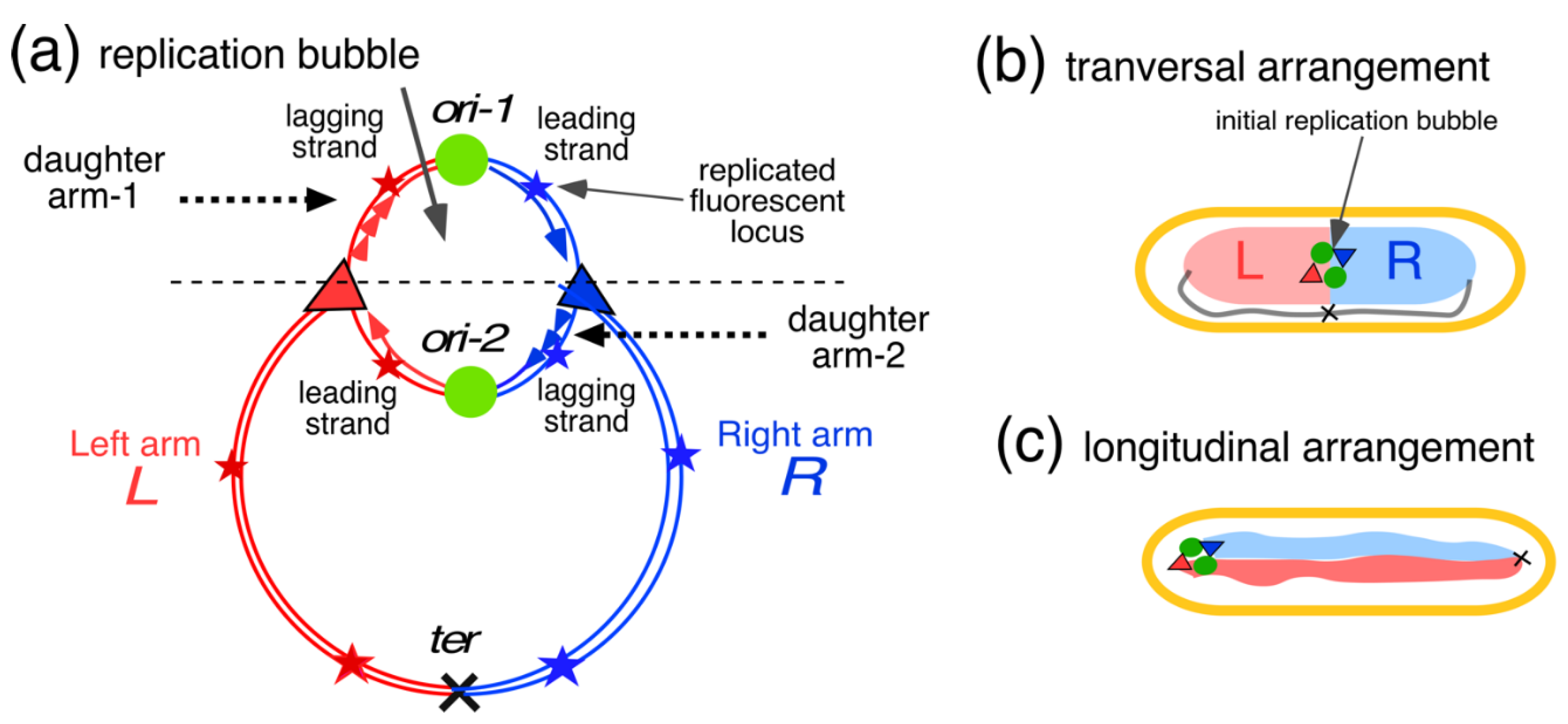

4. Segregation and Movement of Chromosome Arms (Replichores)

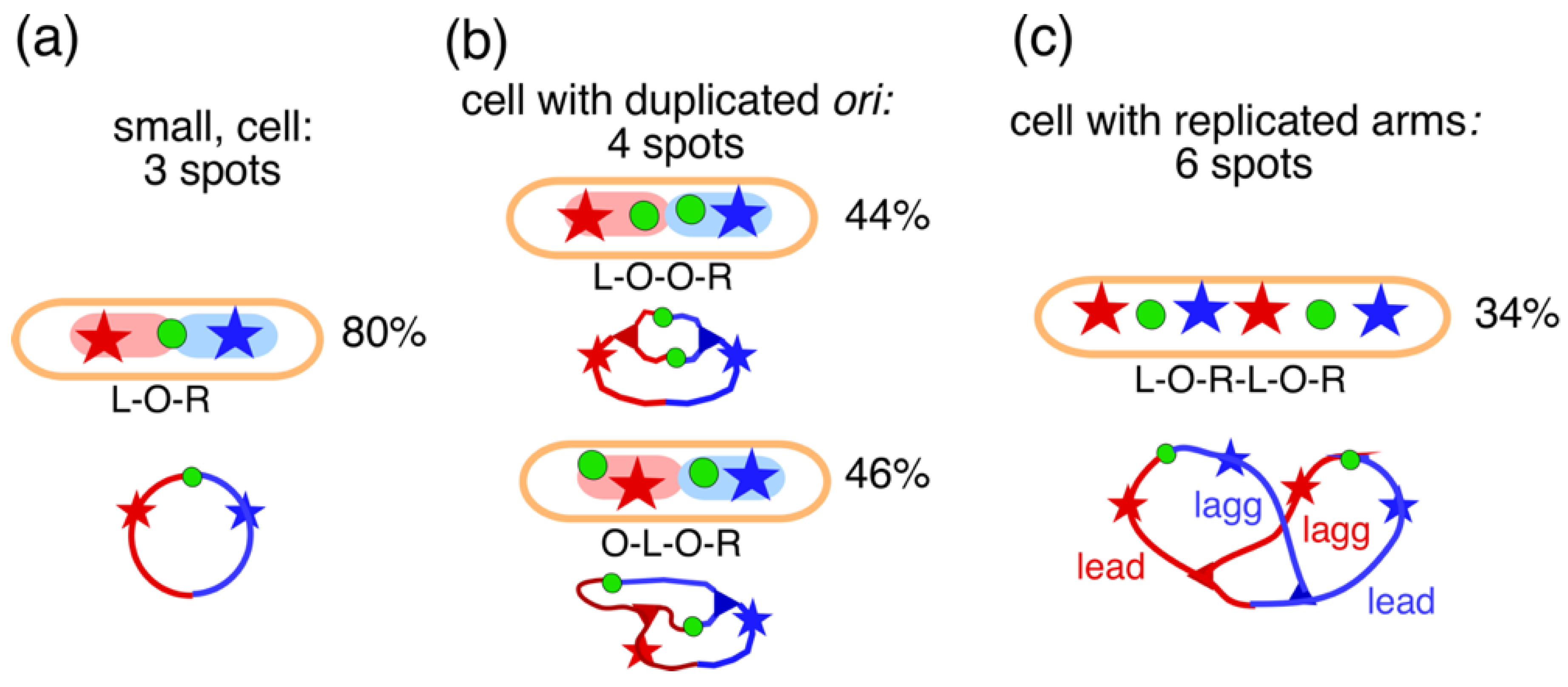

4.1. Replichore Movement to Opposite Halves of the Nucleoid

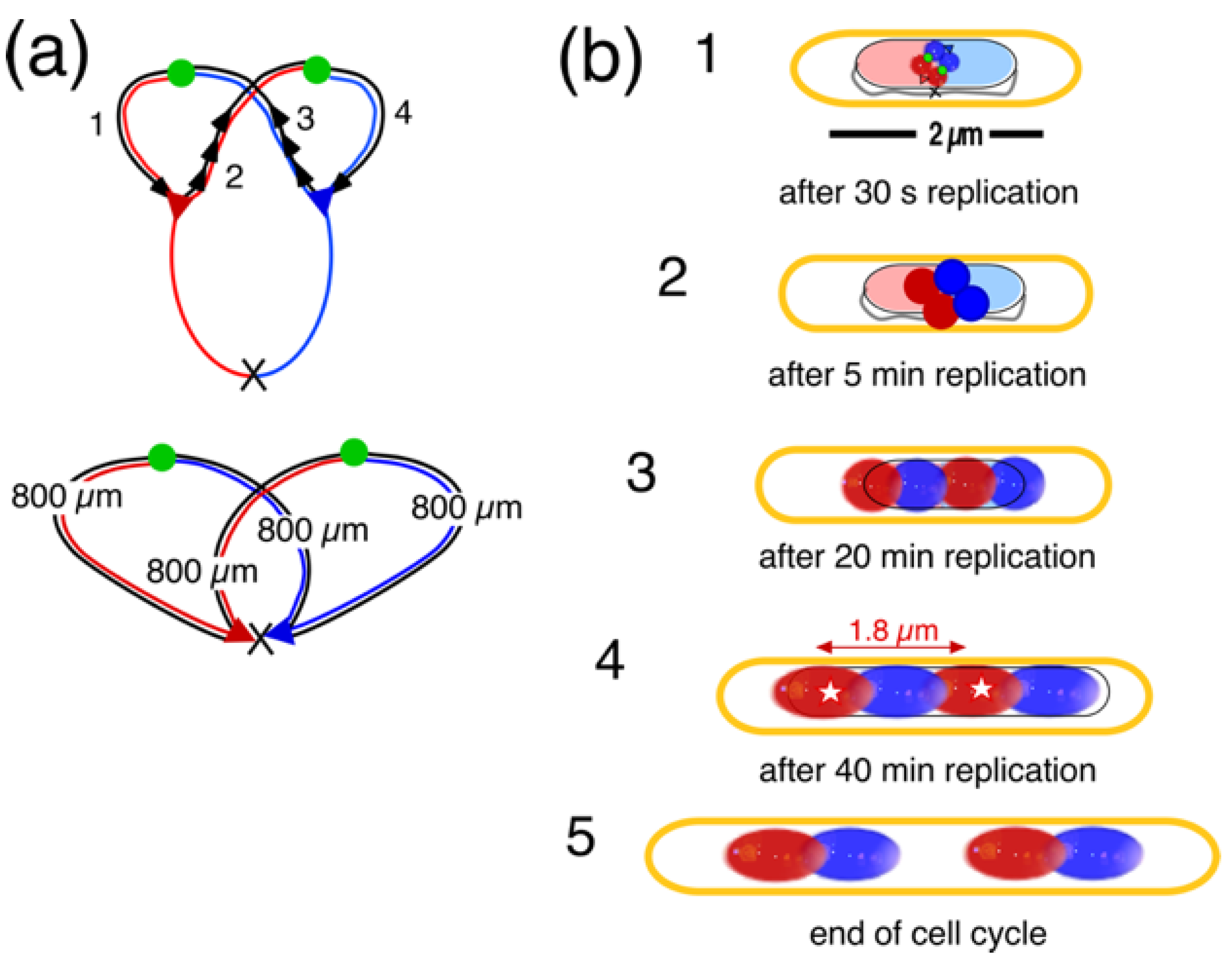

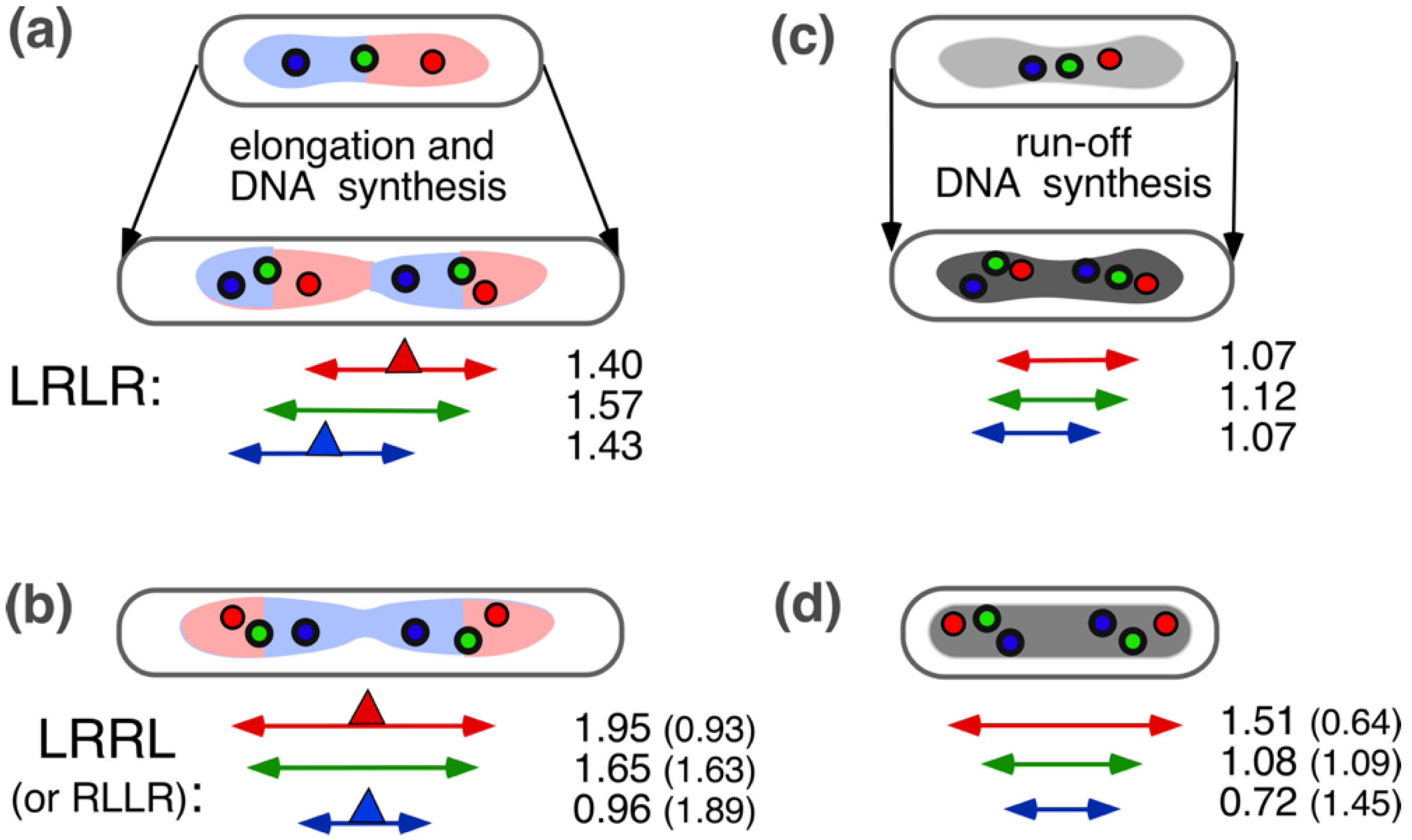

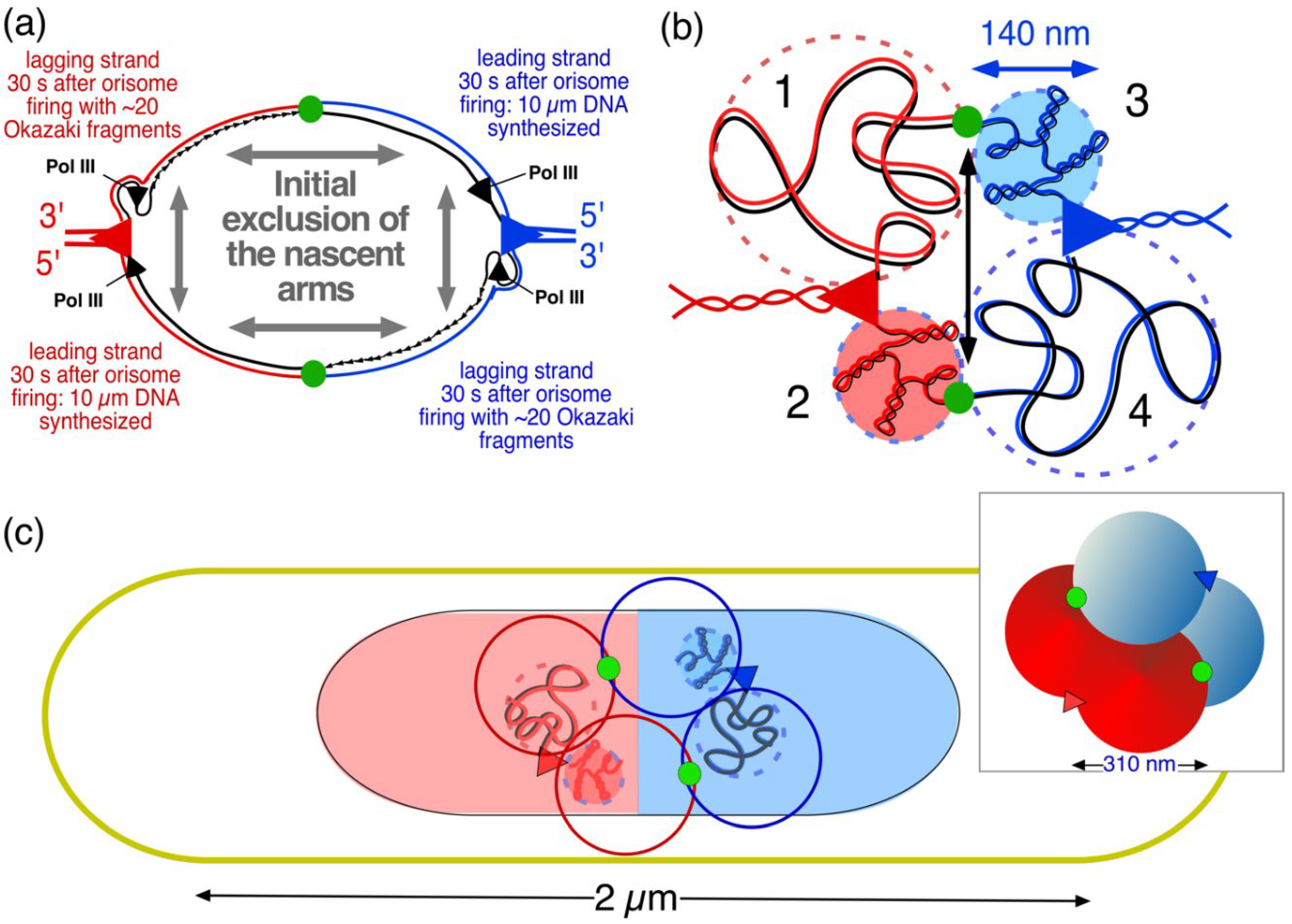

4.2. Four-Excluding-Arms Model for Segregation (1)

4.3. Comparison between Bacteria and Eukaryotic Cells and the Phenomenon of Cohesion

5. Conclusion

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variable | Input value |

| Volume cell (cytoplasm + nucleoid), Vcell; see Table 1, note (2) in main text. |

0.81 µm3 |

| Double helix contour length, L | 1600 µm |

| Superhelix contour length, Ls | 640 µm |

| Superhelix diameter, Ds | 22 nm |

| Radius average 40 kDal protein, a volume of spherical 40 kDal protein: |

2.3 nm 0.051 x 10-6 µm3 |

| Supercoil Kuhn length, As | 158 nm |

| Number supercoiled Kuhn segments, Ns = Ls/ As = | 4000 |

| DNA self-excluded volume Bs = = | 7073 µm3 |

| Fself = Bs/Vcell = 7073/0.81= | 0.87 x 104 kBT |

| Number soluble proteins, m (in cytoplasm (0.77x106) plus nucleoid (0.84x106)); see Figure 7b in main text. | 1.6 x 106 |

| Exclusion radius, E ( | 4.7 nm |

| DNA-protein excluded volume, = | 0.11 µm3 |

| Fcross = = | 22 x 104 kBT |

| Volume fraction total proteins, = | 0.101 |

Appendix B

|

Volume (x 10-12 ml), mass (x 10-12 mg) and numbers |

Cells of Chang(1a) |

Cells of Huls (2001)1b) |

| Doubling time at 37°C | 60 min | 150 min |

| Volume cell (Vcell) |

0.7 (Table S1) |

0.81(2b) |

| Volume nucleoid (Vnuc) | 0.35 | 0.33(2b) |

| Volume envelope (Venv) | - | 0.12 (3b) |

| Volume “cytosolic phase”, Vcyto | 0.35 (4a) | 0.36 (4b) |

| Volume cytoplasm + nucleoid, Vcyto+nuc | - | 0.69(5b) |

| Total mass of proteins | 22.59(6a) | 136 (6b) |

| Total mass soluble and ribosomal proteins (considered as 40 kDa proteins) divided over: - cytosol - nucleoid |

15.3(6a) 8.1 7.17 |

116(6b) cytosol+nucleoid: 116 |

| Total number of 40 kDa proteins (soluble + ribosomal proteins) | 0.34x106 | 2.05x106 |

| Number of ribosomes | 6000(7a) | 8000 (7b) |

| DNA mass (1 chromosome equivalent) | 4.72 (8a, b) | |

| Average number chrom. equivalents per cell, Gc | 1.67 | 1.35(9b) |

| Total mass of stable RNA for 6000(10a) or 8000 ribosomes(10b) | 19.2(10a) | 23(10b) |

| Mass ribosomal proteins in cytosol | 7.32(11a) | 9.76(11b) |

| Number ribosomal proteins considered as 40 kDa proteins | 0.11x106 | 0.15x106 |

| Mass non-ribosomal, soluble 40 kDa proteins in cytosol | 8.1 | 106(11b) |

| Number of non-ribosomal (soluble) proteins in cytoplasm | 0.84x106 | |

| Number of non-ribosomal (soluble) proteins in nucleoid | 0.108x106 | 0.77x106 |

| Total number of non-ribosomal (soluble) proteins | 0.23 x 106 | 1.61 x 106 |

| Concentrations (g/100 ml) (12) | ||

| DNA concentration in nucleoid (DNA mass x number chrom.equiv./ Vnuc) | 2.25 | 1.93 |

| Concentration soluble proteins in nucleoid | 2.05(6a) | 15.4(6b) |

| Concentration stable RNA in cytosol (Vcyto) | 5.49(10a) | 6.39(10b) |

| Concentration soluble proteins in cytosol | 2.32(6a) | 15.4(6b) |

| Concentration ribosomal proteins in cytosol (Vcyto) | 2.09(11a) | 2.71(11b) |

Appendix C

| Time after initiation |

Length of newly replicated DNA per domain (1) (µm) |

Approximate volume nascent domain (2) (µm3) |

Domain diameter sphere or diameter/length cylinder (µm) |

Used for panels in Figure A1b |

| 30 s | 10 | 0.0015 | 0.14 | 1 |

| 5 min | 100 | 0.015 | 0.31 | 2 |

| 10 min | 200 | 0.031 | 0.39 | - |

| 20 min | 400 | 0.062 | 0.46/0.53 | 3 |

| 30 min | 600 | 0.093 | 0.46/0.7 | - |

| 40 min | 800 | 0.124 | 0.46/0.9 | 4 |

References

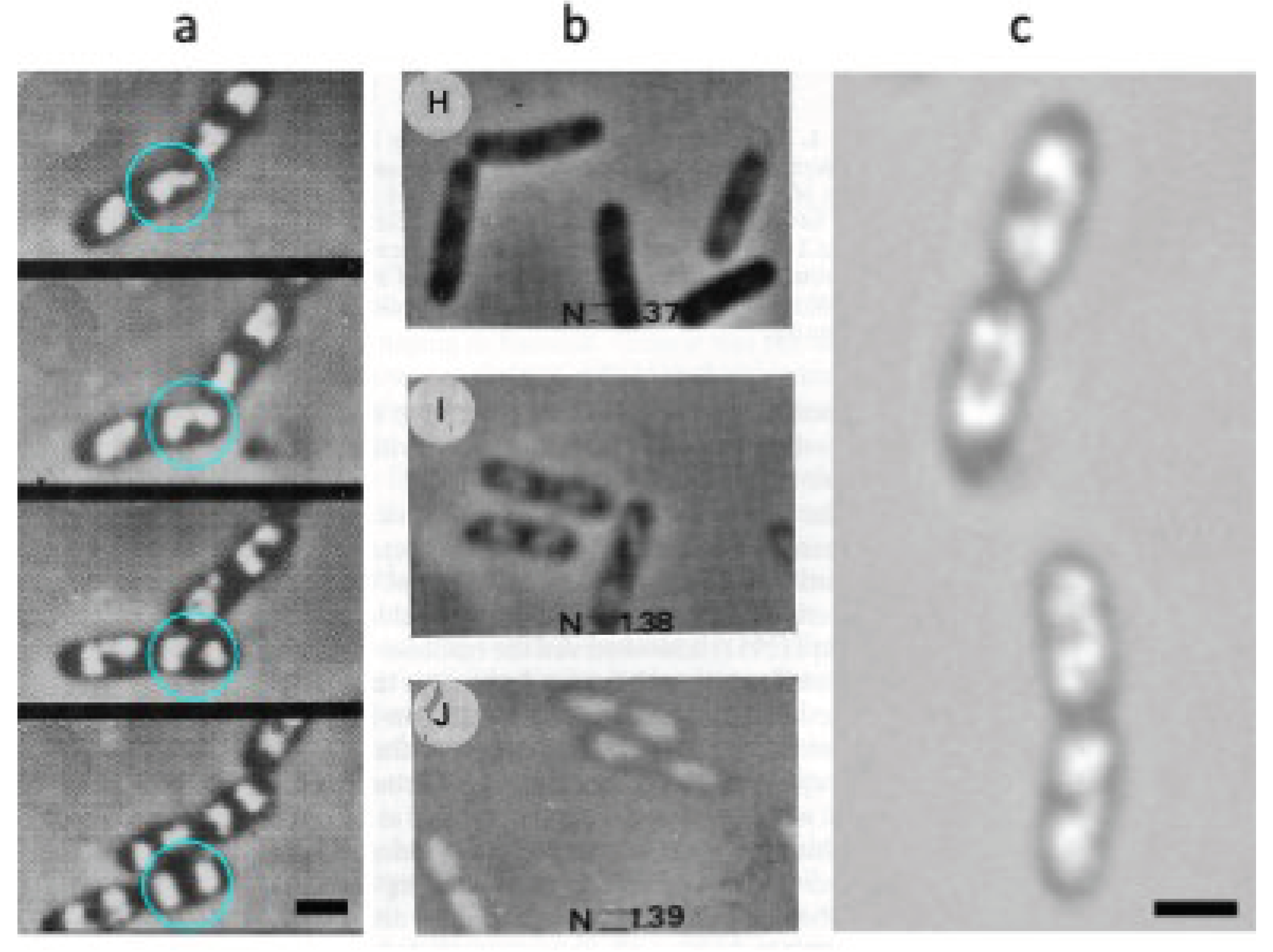

- Mason, D.J.; Powelson, D.M. Nuclear division as observed in live bacteria by a new technique. J Bacteriol 1956, 71, 474–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinow, C.; Kellenberger, E. The bacterial nucleoid revisited. Microbiol Rev 1994, 58, 211–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Jeon, C.; Jeong, H.; Jung, Y.; Ha, B.Y. A polymer in a crowded and confined space: Effects of crowder size and poly-dispersity. Soft Matter 2015, 11, 1877–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyeux, M. Organization of the bacterial nucleoid by DNA-bridging proteins and globular crowders. Front Microbiol 2023, 14, 1116776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odijk, T. Osmotic compaction of supercoiled DNA into a bacterial nucleoid. Biophys Chem 1998, 73, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.H.; Lavrentovich, M.O.; Mannik, J. Differentiating the roles of proteins and polysomes in nucleoid size homeostasis in Escherichia coli. Biophys J 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Mannik, J.; Retterer, S.T.; Mannik, J. The effects of polydisperse crowders on the compaction of the Escherichia coli nucleoid. Mol Microbiol 2020, 113, 1022–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.; Surovtsev, I.V.; Chang, Y.; Govers, S.K.; Parry, B.R.; Liu, J.; Jacobs-Wagner, C. Interconnecting solvent quality, transcription, and chromosome folding in Escherichia coli. Cell 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.B.; Imakaev, M.V.; Mirny, L.A.; Laub, M.T. High-resolution mapping of the spatial organization of a bacterial chromosome. Science 2013, 342, 731–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bignaud, A.; Cockram, C.; Borde, C.; Groseille, J.; Allemand, E.; Thierry, A.; Marbouty, M.; Mozziconacci, J.; Espéli, O.; Koszul, R. Transcription-induced domains form the elementary constraining building blocks of bacterial chromosomes. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, A.C.; Grimwade, J.E. The orisome: Structure and function. Front Microbiol 2015, 6, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, X.; Possoz, C.; Sherratt, D.J. The two Escherichia coli chromosome arms locate to separate cell halves. Genes Dev 2006, 20, 1727–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, H.J.; Ottesen, J.R.; Youngren, B.; Austin, S.J.; Hansen, F.G. The Escherichia coli chromosome is organized with the left and right chromosome arms in separate cell halves. Mol Microbiol 2006, 62, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawalek, A.; Wawrzyniak, P.; Bartosik, A.A.; Jagura-Burdzy, G. Rules and exceptions: The role of chromosomal ParB in DNA segregation and other cellular processes. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livny, J.; Yamaichi, Y.; Waldor, M.K. Distribution of centromere-like pars sites in bacteria: Insights from comparative genomics. J Bacteriol 2007, 189, 8693–8703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viollier, P.H.; Thanbichler, M.; McGrath, P.T.; West, L.; Meewan, M.; McAdams, H.H.; Shapiro, L. Rapid and sequential movement of individual chromosomal loci to specific subcellular locations during bacterial DNA replication. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science U.S.A. 2004, 101, 9257–9262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robalino-Espinosa, J.S.; Zupan, J.R.; Chavez-Arroyo, A.; Zambryski, P. Segregation of four agrobacterium tumefaciens replicons during polar growth: PopZ and PodJ control segregation of essential replicons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020, 117, 26366–26373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badrinarayanan, A.; Le, T.B.; Laub, M.T. Bacterial chromosome organization and segregation. Annual review of cell and developmental biology 2015, 31, 171–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogou, C.; Japaridze, A.; Dekker, C. Mechanisms for chromosome segregation in bacteria. Front Microbiol 2021, 12, 685687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaechter, M.; Williamson, J.P.; Hood, J.R., Jr.; Koch, A.L. Growth, cell and nuclear divisions in some bacteria. J Gen Microbiol 1962, 29, 421–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binnerts, J.S.; Woldringh, C.L.; Brakenhoff, G.J. Visualization of the nucleoid in living bacteria on poly-lysine coated surfaces by the immersion technique. J Microsc 1982, 125, 359–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barer, R.; Joseph, S. Refractometry of living cells, Part I. Basic principles. Journal of Cell Science 1954, s3-95, 399–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaichi, Y.; Niki, H. Migs, a cis-acting site that affects bipolar positioning of oric on the Escherichia coli chromosome. EMBO Journal 2004, 23, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woldringh, C.L. Morphological analysis of nuclear separation and cell division during the life cycle of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 1976, 125, 248–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldewurtel, E.R.; Kitahara, Y.; van Teeffelen, S. Robust surface-to-mass coupling and turgor-dependent cell width determine bacterial dry-mass density. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2021, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.; Ryu, J.S.; Lee, M.; Jung, J.; Han, S.; Chung, H.J.; Park, Y. Three-dimensional label-free observation of individual bacteria upon antibiotic treatment using optical diffraction tomography. Biomed Opt Express 2020, 11, 1257–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valkenburg, J.A.; Woldringh, C.L. Phase separation between nucleoid and cytoplasm in Escherichia coli as defined by immersive refractometry. J Bacteriol 1984, 160, 1151–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchward, G.; Bremer, H.; Young, R. Macromolecular composition of bacteria. Journal of theoretical biology 1982, 94, 651–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brakenhoff, G.J.; Blom, P.; Barends, P. Confocal scanning light microscopy with high aperture immersion lenses. Journal of Microscopy 1979, 117, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanninga, N. Molecular cytology of ‘little animals’: Personal recollections of Escherichia coli (and Bacillus subtilis). Life (Basel) 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woldringh, C.L.; Nanninga, N. Structure of the nucleoid and cytoplasm in the intact cell. In Molecular cytology of Escherichia coli., Nanninga, N., Ed. Academic Press: London, 1985; pp 161-197.

- Zimmerman, S.B.; Murphy, L.D. Release of compact nucleoids with characteristic shapes from Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 2001, 183, 5041–5049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, S.; Woldringh, C.L.; Odijk, T. Polymer-mediated compaction and internal dynamics of isolated Escherichia coli nucleoids. J Struct Biol 2001, 136, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woldringh, C.L.; Odijk, T. Structure of DNA within the bacterial cell: Physics and physiology. In Organization of the prokaryotic genome, R.L. Charlebois Ed. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C., 1999; pp 171-187.

- Pelletier, J.; Halvorsen, K.; Ha, B.Y.; Paparcone, R.; Sandler, S.J.; Woldringh, C.L.; Wong, W.P.; Jun, S. Physical manipulation of the Escherichia coli chromosome reveals its soft nature. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012, 109, E2649–E2656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosberg, A.Y.; Khokhlov, A.R. Giant molecules: Here, there, and everywhere. Academic Press: New York, 1997; p 242.

- Reisner, W.; Pedersen, J.N.; Austin, R.H. DNA confinement in nanochannels: Physics and biological applications. Rep Prog Phys 2012, 75, 106601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, J.K.; Bourniquel, A.; Witz, G.; Weiner, B.; Prentiss, M.; Kleckner, N. Four-dimensional imaging of E. coli nucleoid organization and dynamics in living cells. Cell 2013, 153, 882–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, D.; Kleckner, N. Chromosome and replisome dynamics in Escherichia coli: Loss of sister cohesion triggers global chromosome movement and mediates chromosome segregation. Cell 2005, 121, 899–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blattner, F.R.; Plunkett, G., 3rd; Bloch, C.A.; Perna, N.T.; Burland, V.; Riley, M.; Collado-Vides, J.; Glasner, J.D.; Rode, C.K.; Mayhew, G.F. , et al. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science 1997, 277, 1453–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberger, M.; Helmstetter, C.E. Chromosome replication and cell division in plasmid-containing Escherichia coli B/r. J Bacteriol 1979, 137, 1151–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, W.T.; Govers, S.K.; Xiang, Y.; Parry, B.R.; Campos, M.; Kim, S.; Jacobs-Wagner, C. Nucleoid size scaling and intracellular organization of translation across bacteria. Cell 2019, 177, 1632–1648.e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bremer, H.; Dennis, P.P. Modulation of chemical composition and other parameters of the cell at different exponential growth rates. EcoSal Plus 2008, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegner, A.S.; Alexeeva, S.; Odijk, T.; Woldringh, C.L. Characterization of Escherichia coli nucleoids released by osmotic shock. J Struct Biol 2012, 178, 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Junier, I.; Ghobadpour, E.; Espeli, O.; Everaers, R. DNA supercoiling in bacteria: State of play and challenges from a viewpoint of physics based modeling. Front Microbiol 2023, 14, 1192831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endesfelder, U. From single bacterial cell imaging towards in vivo single-molecule biochemistry studies. Essays Biochem 2019, 63, 187–196. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.; Mustafi, M.; Weisshaar, J.C. Biophysical properties of Escherichia coli cytoplasm in stationary phase by superresolution fluorescence microscopy. mBio 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spahn, C.K.; Glaesmann, M.; Grimm, J.B.; Ayala, A.X.; Lavis, L.D.; Heilemann, M. A toolbox for multiplexed super-resolution imaging of the Escherichia coli nucleoid and membrane using novel paint labels. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 14768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spahn, C.; Hurter, F.; Glaesmann, M.; Karathanasis, C.; Lampe, M.; Heilemann, M. Protein-specific, multicolor and 3d STED imaging in cells with DNA-labeled antibodies. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2019, 58, 18835–18838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stracy, M.; Lesterlin, C.; Garza de Leon, F.; Uphoff, S.; Zawadzki, P.; Kapanidis, A.N. Live-cell superresolution microscopy reveals the organization of RNA polymerase in the bacterial nucleoid. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015, 112, E4390–E4399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, D.J.; Cagliero, C.; Zhou, Y.N. Role of rna polymerase and transcription in the organization of the bacterial nucleoid. Chem Rev 2013, 113, 8662–8682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lioy, V.S.; Junier, I.; Boccard, F. Multiscale dynamic structuring of bacterial chromosomes. Annu Rev Microbiol 2021, 75, 541–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, J.; Bratton, B.P.; Li, Y.; Yethiraj, A.; Weisshaar, J.C. Entropy-based mechanism of ribosome-nucleoid segregation in Escherichia coli cells. Biophys J 2011, 100, 2605–2613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, J.E.; Cagliero, C.; Quan, S.; Squires, C.L.; Jin, D.J. Active transcription of rrna operons condenses the nucleoid in Escherichia coli: Examining the effect of transcription on nucleoid structure in the absence of transertion. J Bacteriol 2009, 191, 4180–4185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spahn, C.; Middlemiss, S.; Gómez-de-Mariscal, E.; Henriques, R.; Bode, H.B.; Holden, S.; Heilemann, M. Transertion and cell geometry organize the Escherichia coli nucleoid during rapid growth. bioRxiv, 2023; 2023.2010.2016.562172. [Google Scholar]

- Dworsky, P.; Schaechter, M. Effect of rifampin on the structure and membrane attachment of the nucleoid of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 1973, 116, 1364–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrington, E.W.; Trun, N.J. Unfolding of the bacterial nucleoid both in vivo and in vitro as a result of exposure to camphor. J Bacteriol 1997, 179, 2435–2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Helvoort, J.; Huls, P.G.; Vischer, N.O.E.; Woldringh, C.L. Fused nucleoids resegregate faster than cell elongation in Escherichia coli pbpB(ts) filaments after release from chloramphenicol inhibition. Microbiology (Reading) 1998, 144, 1309–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Margolin, W. Effects of perturbing nucleoid structure on nucleoid occlusion-mediated toporegulation of FtsZ ring assembly. J Bacteriol 2004, 186, 3951–3959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakshi, S.; Siryaporn, A.; Goulian, M.; Weisshaar, J.C. Superresolution imaging of ribosomes and RNA polymerase in live Escherichia coli cells. Mol Microbiol, 2012; 85, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakshi, S.; Choi, H.; Mondal, J.; Weisshaar, J.C. Time-dependent effects of transcription- and translation-halting drugs on the spatial distributions of the Escherichia coli chromosome and ribosomes. Mol Microbiol 2014, 94, 871–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakshi, S.; Choi, H.; Weisshaar, J.C. The spatial biology of transcription and translation in rapidly growing Escherichia coli. Front Microbiol 2015, 6, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

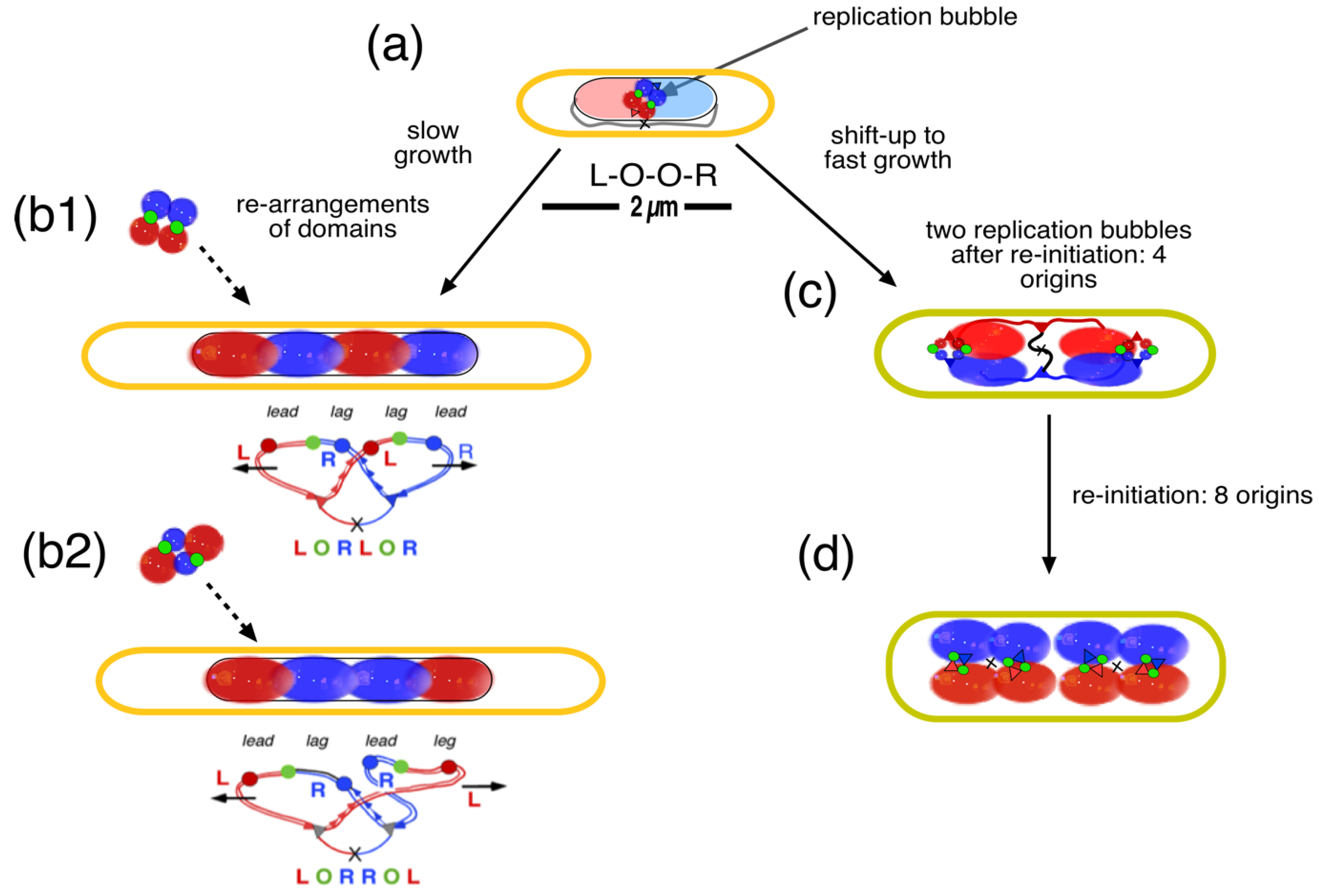

- Woldringh, C.L.; Hansen, F.G.; Vischer, N.O.; Atlung, T. Segregation of chromosome arms in growing and non-growing Escherichia coli cells. Front Microbiol 2015, 6, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohiyama, M.; Herrick, J.; Norris, V. Open questions about the roles of DnaA, related proteins, and hyperstructure dynamics in the cell cycle. Life 2023, 13, 1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, H.J.; Youngren, B.; Hansen, F.G.; Austin, S. Dynamics of Escherichia coli chromosome segregation during multifork replication. J Bacteriol 2007, 189, 8660–8666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, X.; Reyes-Lamothe, R.; Sherratt, D. Replication-directed sister chromosome alignment in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol 2010, 75, 1090–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reyes-Lamothe, R.; Nicolas, E.; Sherratt, D.J. Chromosome replication and segregation in bacteria. Annu Rev Genet 2012, 46, 121–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reyes-Lamothe, R.; Sherratt, D.J. The bacterial cell cycle, chromosome inheritance and cell growth. Nat Rev Microbiol 2019, 17, 467–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmstetter, C.E. DNA synthesis during the division cycle of rapidly growing Escherichia coli B/r. J Mol Biol 1968, 31, 507–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makela, J.; Uphoff, S.; Sherratt, D.J. Nonrandom segregation of sister chromosomes by Escherichia coli MukBEF. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2021, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norris, V.; Madsen, M.S. Autocatalytic gene expression occurs via transertion and membrane domain formation and underlies differentiation in bacteria: A model. J Mol Biol 1995, 253, 739–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woldringh, C.L. The role of co-transcriptional translation and protein translocation (transertion) in bacterial chromosome segregation. Mol Microbiol 2002, 45, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemon, K.P.; Grossman, A.D. The extrusion-capture model for chromosome partitioning in bacteria. Genes Dev 2001, 15, 2031–2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youngren, B.; Nielsen, H.J.; Jun, S.; Austin, S. The multifork Escherichia coli chromosome is a self-duplicating and self-segregating thermodynamic ring polymer. Genes Dev 2014, 28, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiggins, P.A.; Cheveralls, K.C.; Martin, J.S.; Lintner, R.; Kondev, J. Strong intranucleoid interactions organize the Escherichia coli chromosome into a nucleoid filament. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010, 107, 4991–4995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Sherratt, D.J. Independent segregation of the two arms of the Escherichia coli ori region requires neither RNA synthesis nor MreB dynamics. J Bacteriol 2010, 192, 6143–6153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dame, R.T.; Rashid, F.M.; Grainger, D.C. Chromosome organization in bacteria: Mechanistic insights into genome structure and function. Nat Rev Genet 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makela, J.; Sherratt, D.J. Organization of the Escherichia coli chromosome by a mukbef axial core. Mol Cell 2020, 78, 250–260.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jun, S.; Mulder, B. Entropy-driven spatial organization of highly confined polymers: Lessons for the bacterial chromosome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006, 103, 12388–12393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jun, S.; Wright, A. Entropy as the driver of chromosome segregation. Nat Rev Microbiol 2010, 8, 600–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elmore, S.; Muller, M.; Vischer, N.; Odijk, T.; Woldringh, C.L. Single-particle tracking of oriC-GFP fluorescent spots during chromosome segregation in Escherichia coli. J Struct Biol 2005, 151, 275–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khodursky, A.; Guzman, E.C.; Hanawalt, P.C. Thymineless death lives on: New insights into a classic phenomenon. Annu Rev Microbiol 2015, 69, 247–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woldringh, C.L. The bacterial nucleoid: From electron microscopy to polymer physics-a personal recollection. Life (Basel) 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, M.C.; Bourniquel, A.; Fisher, J.; Ho, B.T.; Magnan, D.; Kleckner, N.; Bates, D. Escherichia coli sister chromosome separation includes an abrupt global transition with concomitant release of late-splitting intersister snaps. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011, 108, 2765–2770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaritsky, A.; Vollmer, W.; Mannik, J.; Liu, C. Does the nucleoid determine cell dimensions in Escherichia coli? Front Microbiol 2019, 10, 1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaritsky, A.; Woldringh, C.L.; Fishov, I.; Vischer, N.O.E.; Einav, M. Varying division planes of secondary constrictions in spheroidal Escherichia coli cells. Microbiology (Reading) 1999, 145 Pt 5, 1015–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valens, M.; Penaud, S.; Rossignol, M.; Cornet, F.; Boccard, F. Macrodomain organization of the Escherichia coli chromosome. EMBO J 2004, 23, 4330–4341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javer, A.; Kuwada, N.J.; Long, Z.; Benza, V.G.; Dorfman, K.D.; Wiggins, P.A.; Cicuta, P.; Lagomarsino, M.C. Persistent super-diffusive motion of Escherichia coli chromosomal loci. Nat Commun 2014, 5, 3854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reyes-Lamothe, R.; Wang, X.; Sherratt, D. Escherichia coli and its chromosome. Trends Microbiol 2008, 16, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaritsky, A.; Wang, P.; Vischer, N.O. Instructive simulation of the bacterial cell division cycle. Microbiology 2011, 157, 1876–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woldringh, C.L.; Grover, N.B.; Rosenberger, R.F.; Zaritsky, A. Dimensional rearrangement of rod-shaped bacteria following nutritional shift-up. Ii. Experiments with Escherichia coli B/r. Journal of theoretical biology 1980, 86, 441–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadde, S.; Heald, R. Mechanisms and molecules of the mitotic spindle. Curr Biol 2004, 14, R797–R805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goloborodko, A.; Imakaev, M.V.; Marko, J.F.; Mirny, L. Compaction and segregation of sister chromatids via active loop extrusion. Elife 2016, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirano, T. Condensin-based chromosome organization from bacteria to vertebrates. Cell 2016, 164, 847–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanninga, N.; Roos, M.; Woldringh, C.L. Models on stickiness of replicated Escherichia coli oriC. Microbiology (Reading) 2002, 148, 3327–3328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Reyes-Lamothe, R.; Sherratt, D.J. Modulation of Escherichia coli sister chromosome cohesion by topoisomerase iv. Genes Dev 2008, 22, 2426–2433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woldringh, C.L.; Nanninga, N. Structural and physical aspects of bacterial chromosome segregation. J Struct Biol 2006, 156, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roos, M.; Van Geel, A.B.; Aarsman, M.E.; Veuskens, J.T.; Woldringh, C.L.; Nanninga, N. The replicated ftsQAZ and minB chromosomal regions of Escherichia coli segregate on average in line with nucleoid movement. Molecular Microbiology 2001, 39, 633–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, I.F.; Filipe, S.R.; Soballe, B.; Okstad, O.A.; Barre, F.X.; Sherratt, D.J. Spatial and temporal organization of replicating Escherichia coli chromosomes. Mol Microbiol 2003, 49, 731–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helgesen, E.; Fossum-Raunehaug, S.; Saetre, F.; Schink, K.O.; Skarstad, K. Dynamic Escherichia coli SeqA complexes organize the newly replicated DNA at a considerable distance from the replisome. Nucleic Acids Res 2015, 43, 2730–2743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, F.; Japaridze, A.; Zheng, X.; Wiktor, J.; Kerssemakers, J.W.J.; Dekker, C. Direct imaging of the circular chromosome in a live bacterium. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Japaridze, A.; Gogou, C.; Kerssemakers, J.W.J.; Nguyen, H.M.; Dekker, C. Direct observation of independently moving replisomes in Escherichia coli. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 3109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir, M.; Babacan, S.D.; Bednarz, M.; Do, M.N.; Golding, I.; Popescu, G. Visualizing Escherichia coli sub-cellular structure using sparse deconvolution spatial light interference tomography. PLoS One 2012, 7, e39816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, S. In Experiments on the bacterial nucleoid of Escherichia coli viewed as a physical entity, Thesis Technical University of Delft 2004. ISBN 90-77595-77-5.

- Boles, T.C.; White, J.H.; Cozzarelli, N.R. Structure of plectonemically supercoiled DNA. J Mol Biol 1990, 213, 931–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, G.; Park, Y.; Lue, N.; Best-Popescu, C.; Deflores, L.; Dasari, R.R.; Feld, M.S.; Badizadegan, K. Optical imaging of cell mass and growth dynamics. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2008, 295, C538–C544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrenberg, M.; Bremer, H.; Dennis, P.P. Medium-dependent control of the bacterial growth rate. Biochimie 2013, 95, 643–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milo, R. What is the total number of protein molecules per cell volume? A call to rethink some published values. Bioessays 2013, 35, 1050–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, J.P. Physical characterization of the 16s and 23s ribosomal ribonucleic acids from Escherichia coli. Graduate student thesis, University of Montana, 1978.

- Xu, Z.-Q.; Dixon, N.E. Bacterial replisomes. Current Opinion Structural Biology 2018, 53, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, M. Replisome architecture and dynamics in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem 2006, 281, 10653–10656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

E. coli strain |

Doubling time at 37°C (min) 1) |

Volume of newborn cell 2) (µm3) (cell number measured) |

Nucleoid volume in newborn cell (µm3) (threshold) |

DNA concentr. in nucleoid 3) (mg/ml) |

Reference (microscopy/staining: figure in reference) |

| B/rH266 | 150 | 0.33 (10) |

0.07 0.12 4) |

69 40 |

[27] (CSLM/ unstained: Figure 1) |

| K-12 (NK9387) |

~70 (125 at 30°C) |

0.33 (2) |

0.27 (0.5) | 18 | [38,39] (Fluor. microscopy/HupA-mCherry: Figure 1B and 3B) |

| K-12 (MG1655) |

110 (220 at 28°C) |

0.45 0.50 5) |

0.23 0.25 |

21 19 |

[7] (Fluor. microscopy/ HupA- mNeonGreen: Tables S2 and S5) [6] (Fluor. microscopy: Figure 2) |

| K-12 (CJW6324) |

81 6) |

- (B-period cells) (n = 19,510) |

0.7 |

7 | [8] (Fluor. microscopy/DAPI: Figure 7A |

| B/rH266 | 150 | 0.58 (281) |

0.18 (0.6) 7) 0.24 (0.5) 8) 0.34 (0.4) |

27 20 14 |

Huls, 2001 (unpublished) (Fluor. microscopy/DAPI: Figure 5 main text) |

| Reference | Cells and growth condition (Growth rate: fast/slow) |

Rifampicin treatment and imaging/preparation/ staining |

Appearance nucleoid (figure) and interpretation |

Fully dispersed nucleoid (1) Yes/No |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [56] |

E. coli K-12; M9+glucose+Casa, 37°C (fast) |

100 µg/ml; 30 min; electron microscopy; OsO4 - fixation |

“axial” appearance; (Figure 1b) |

no |

| [57] |

E. coli K-12 (NT3) LB medium, 37°C (fast) |

20 µg/ml; 60 min; Light microscopy; poly-lysine slide; no fixation |

“nucleoids decondense” (Figure 2D) |

yes |

| [58] |

E. coli K-12 (MC4100) Glucose minimal medium; 30°C; (slow) |

100 µg/ml; 30 min; Light microscopy, OsO4-fixation; DAPI stained |

“nucleoid fusion”; (Figure 4B) |

no |

| [32] |

E. coli K-12 (C600) LB medium, 37°C (fast) |

40 µg/ml; 60 min; no fixation. |

“compact nucleoids” (Figure 6B) |

no |

| [54] |

E. coli K-12 (DJ2599) M63+glucose+Casa, 30°C; (fast) |

50 µg/ml (?); 10 min; DIC-microscopy; formalde-hyde fixation; DAPI stained; |

“less condensed”; (Figure 2B) |

yes |

| [59] |

E. coli K-12 M9+glucose+Casa, 30°C; (fast) |

100 µg/ml; 30 min; Phase-contrast; methanol-fixed cells; DAPI stained |

“staining uniform throughout cells” (Figure 3F) |

yes |

| [54] |

E. coli K-12 (DJ2599) LB medium, 32°C (fast) |

100 µg/ml; 20 min; Light microscopy; formaldehyde fixation; DAPI stained |

Quick expansion; elongated nucleoid, phase separated (Figure 1B) |

no |

| [60] |

E. coli K-12 (MG1655 ) Low-phosphate EZRDM; 30°C: Td = 60 min; (slow) |

200 µg/ml; 30 min; Widefield epifluorescence microscopy; no fixation; DNA stain DRAQ5 |

radial compaction and axial expansion; (Figure 7B) |

no |

| [51] |

E. coli K-12 () LB medium, 37°C; (fast) |

50 µg/ml (?); 30 or 60 min. fixation? |

“fully expanded nucleoid”; phase separation (Figure 11 and Figure 13) |

no |

| [61] |

E. coli K-12 (MG1655 ) Low-phosphate EZRDM; 30°C: Td = 60 min; (slow) |

300 µg/ml; 20 min; Phase contrast microscopy; no fixation; time-lapse; SYTOX Orange staining |

“radial contraction”; axial contraction followed by expansion; (Figure 2) |

no |

| [62] | idem | idem |

(Figure 8b) |

no |

| [50] |

E. coli MG1655 LB medium; 37°C; (fast) |

50 µg/ml; 3o min; SIMicroscopy; no fixation; DAPI-stained |

Expanded nucleoid (Figure 4C) |

yes |

| [63] |

E. coli MG1655 (FH4035) Minimal glycerol medium (slow) |

300 µg/ml; 210 min; 28°C; Fluorescence microscopy; OsO4-fixation.; DAPIstained |

Compact nucleoids: 9% show divided nucleoids (Figure 3B) |

no |

| [48] |

E. coli K-12 (MG1655 /KF26 cells) LB medium; 32°C; (fast) |

100 µg/ml (Sigma); 30 min; Fixation with 2% formaldehyde+0.05% glutaraldehyde. PAINT-SMLM imaging |

Contraction and expansion nucleoid. Nucleoid fusion? (Figure 5b) |

no |

| [7] |

E. coli K-12 (MG1655) Slow: M9 glycerol minimal medium; Td=60 min at 28°C. Moderately fast: M9+glucose +CASA; Td = 30 min at 28°C. |

300 µg/ml; 20-90 min; Epifluoresc. microscopy; no fixation |

Length expansion at mod. fast growth (Figure 4). volume expansion at fast growth (Figure S13) |

Slow: no fast: yes |

| [8] |

E. coli K-12 (MG1655) M9-glycerol + Casa; 37°C; (fast) |

300 µg/ml; 40 min; no fixation; DAPI-stained |

Expansion nucleoid; nucleoid fusion; (Figure 7A) |

yes |

| [6] |

E. coli K-12 (MG1655-JM57) EZ-Rich medium + glucose; 37°C; (fast) |

300 µg/ml; 20-90 min; Epifluoresc. microscopy; no fixation; HupA-mNeon Green |

“expansion nucleoid” (Figure S4a) |

yes |

| [55] |

E. coli K-12 (NO34) LB at 32°C; (fast) |

100 µg/ml; 60 min. CSLMicroscopy. Fixation with 2% formaldehyde+0.05% glutaraldehyde. |

contraction followed by expansion after 20 min to elongated structure (Figure 2B) |

no |

| Strain FH4035(1) |

Number of sequences analyzed | Average number of spots/cell | % cells with 4-5 spots |

% cells with 6 spots | Average length 6 spot cells (µm) |

% RLRL/ LRLR

|

% RLLR

|

% LRRL

|

% LLRR |

| Control (average of 8 experiments) |

4072 |

4.2 |

13/5 |

39 |

3.02 |

64 |

19 |

17 |

3 |

| Rifampicin treatment (average of 3 experiments) |

2848 |

4.6 |

1/1 |

53 |

2.73 |

51 |

28 |

21 |

0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).