Submitted:

30 March 2024

Posted:

01 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics

2.2. Depersonalized Online Survey

2.3. Sample Size Calculation

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

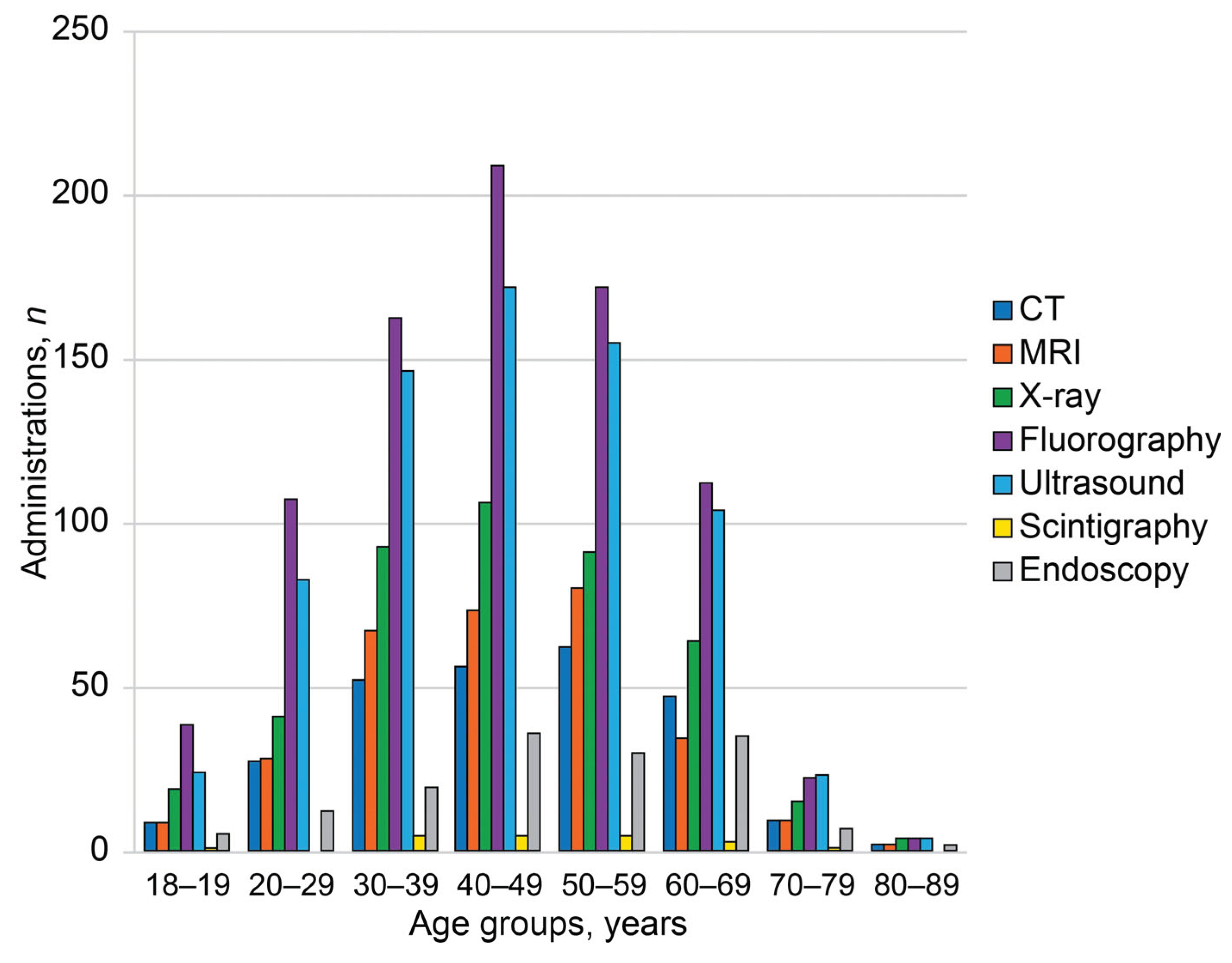

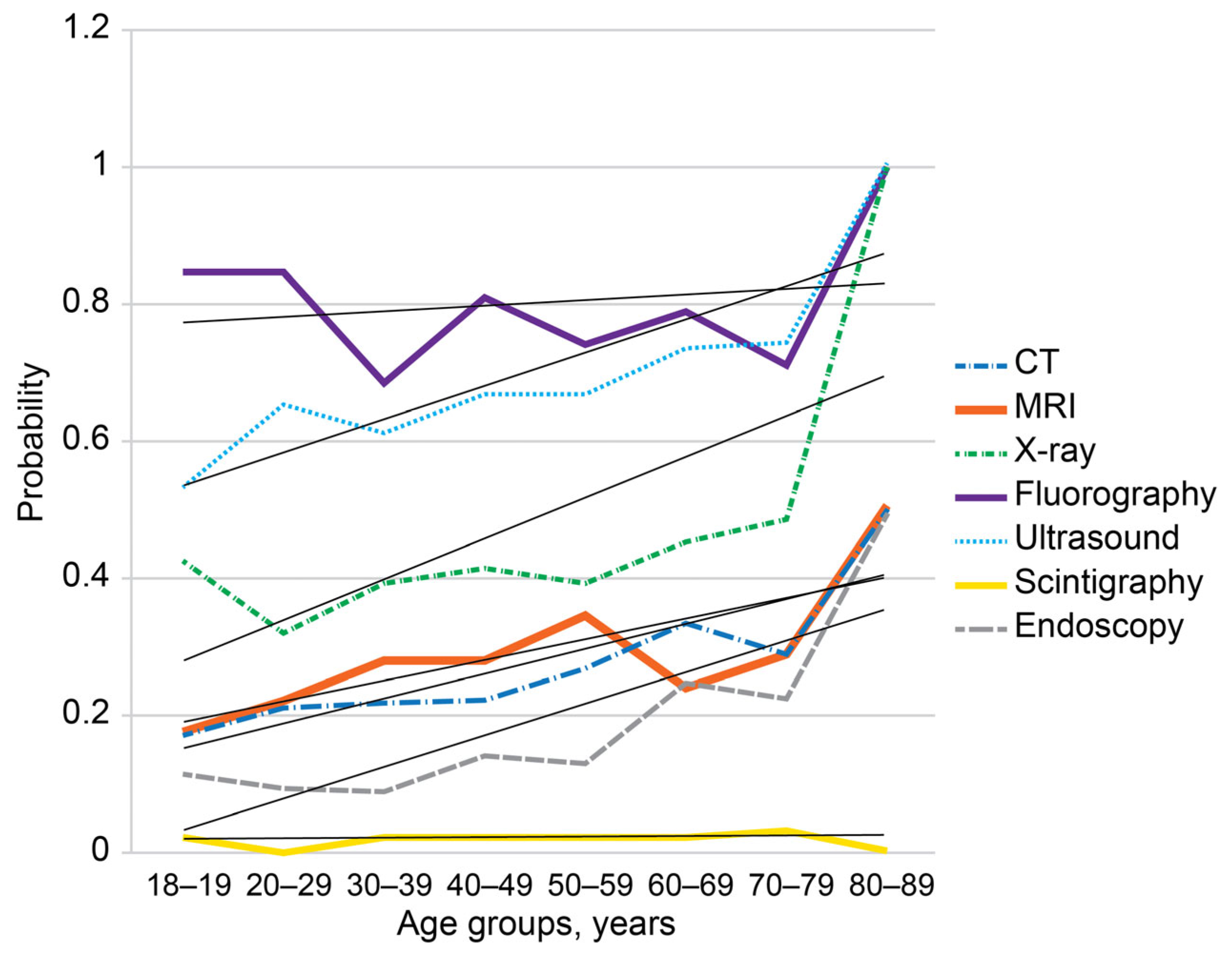

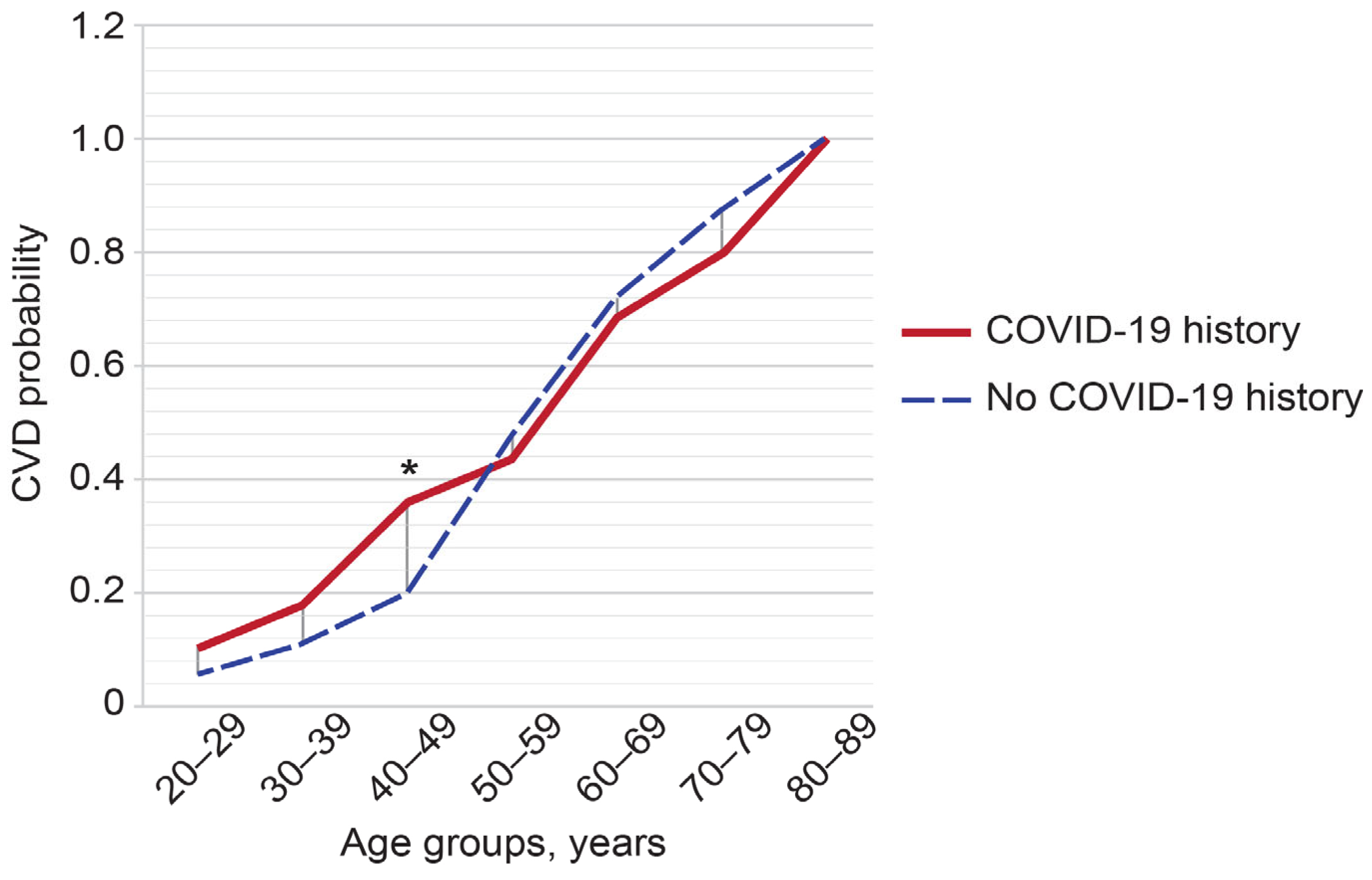

3.2. Age-Related Associations

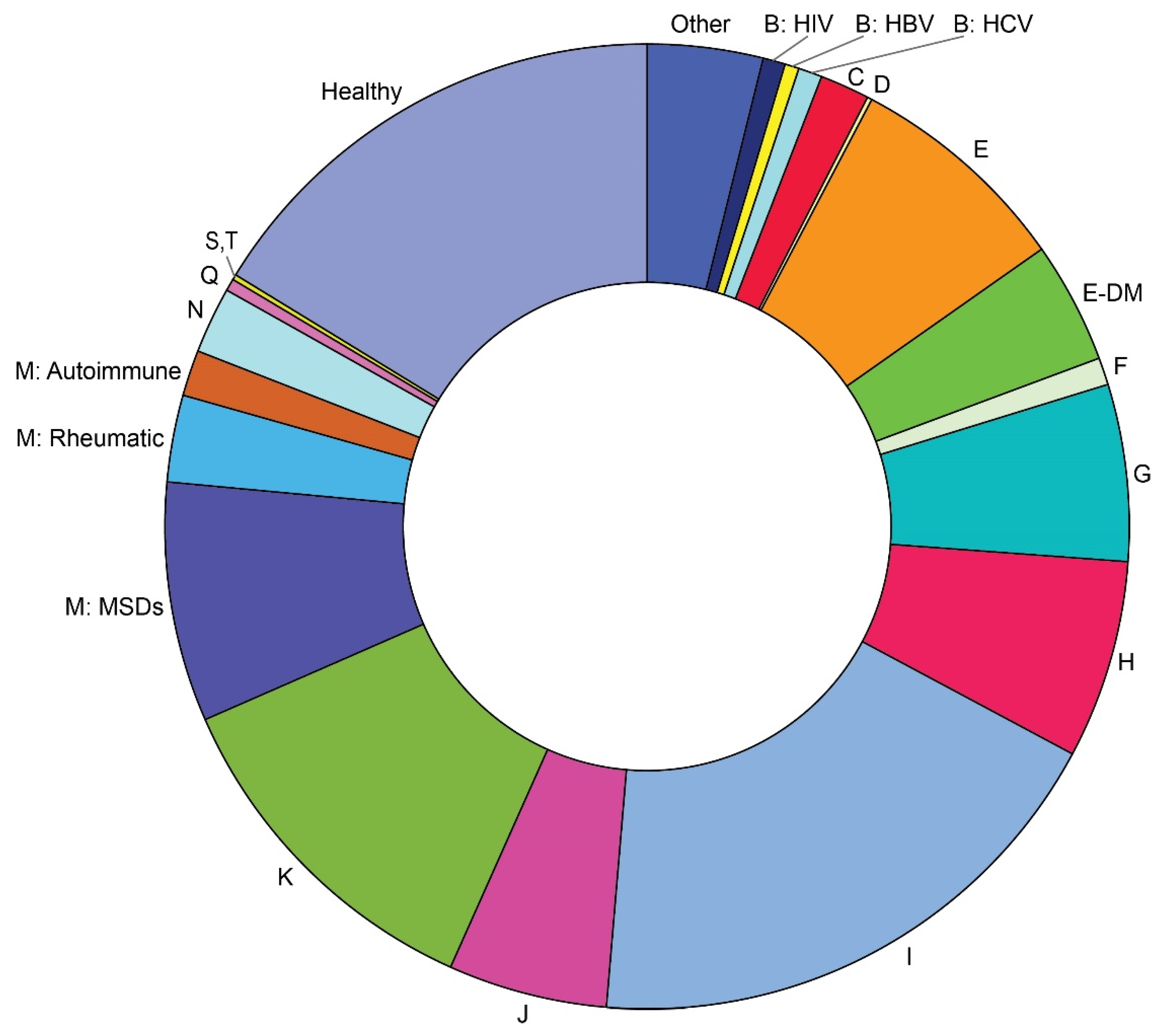

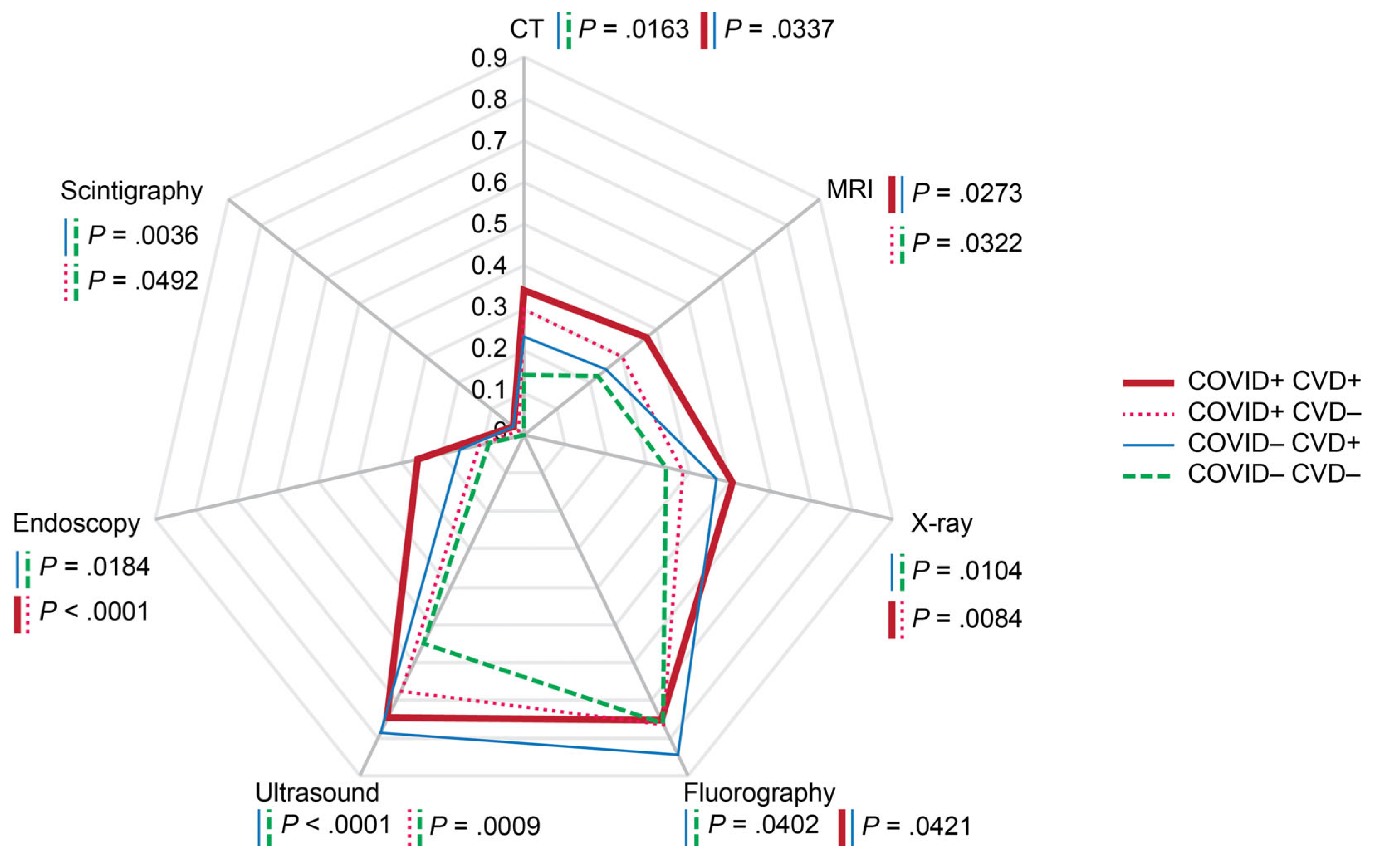

3.3. Morbidity-Related Characteristics

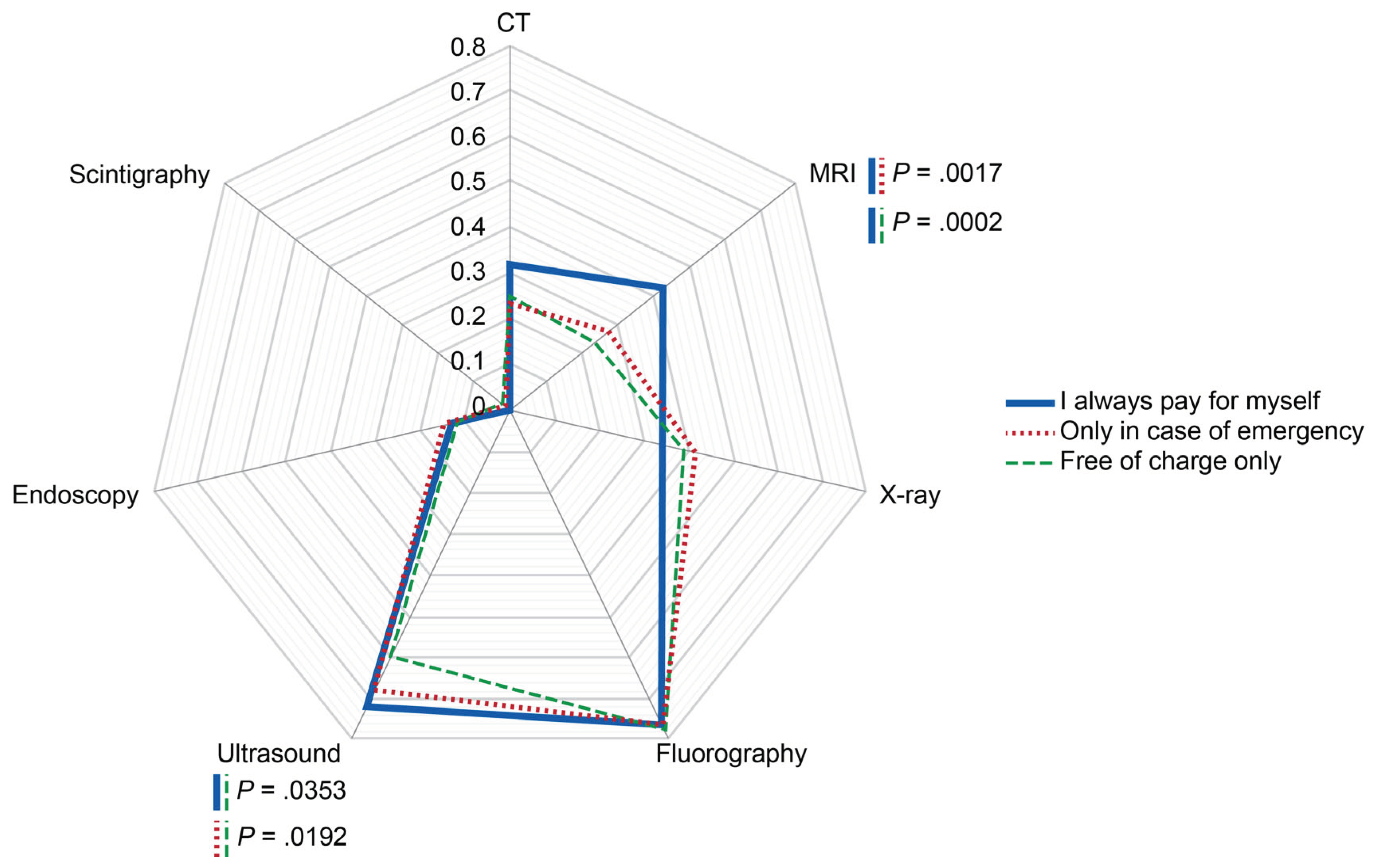

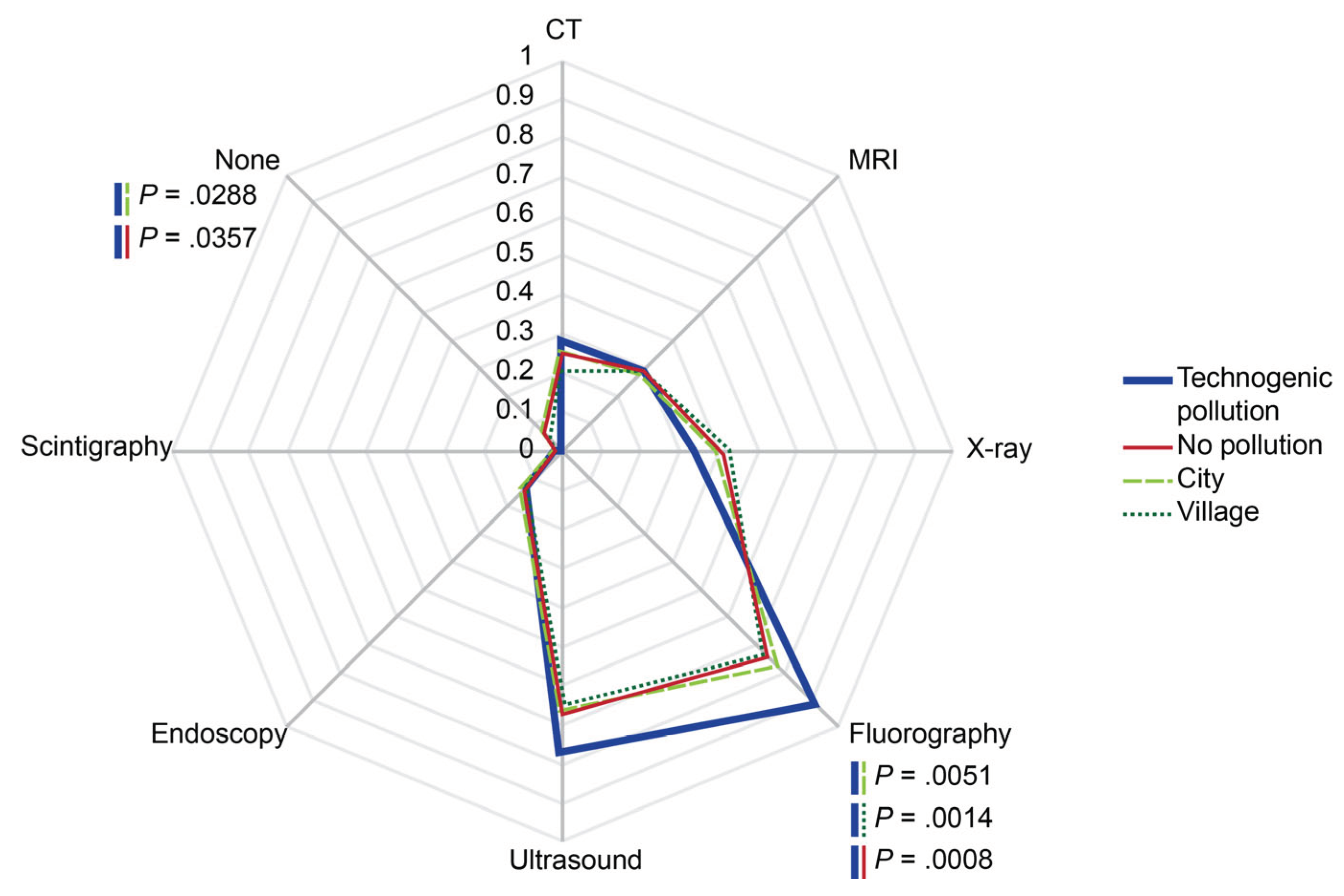

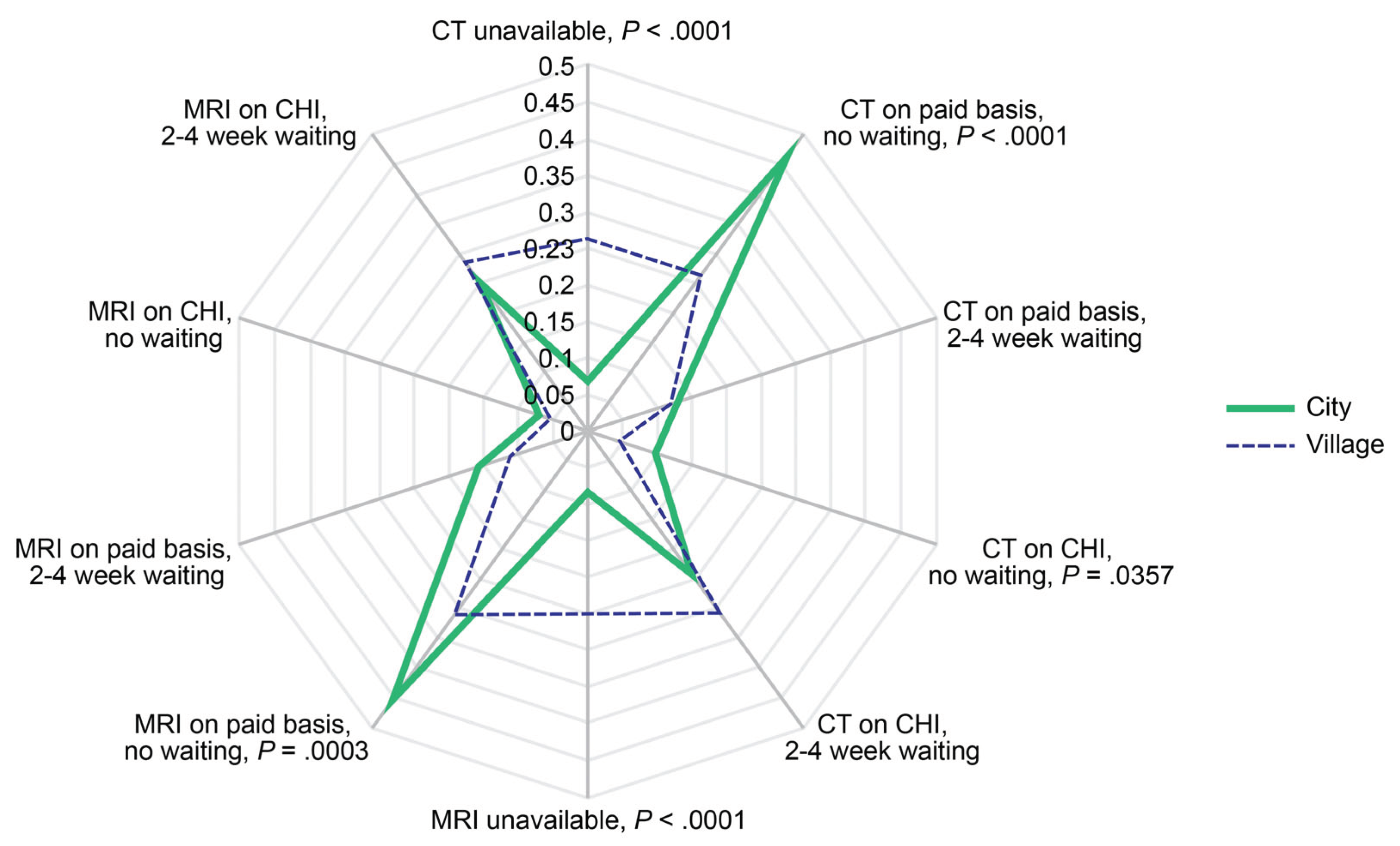

3.4. Diagnostic Imaging Affordability

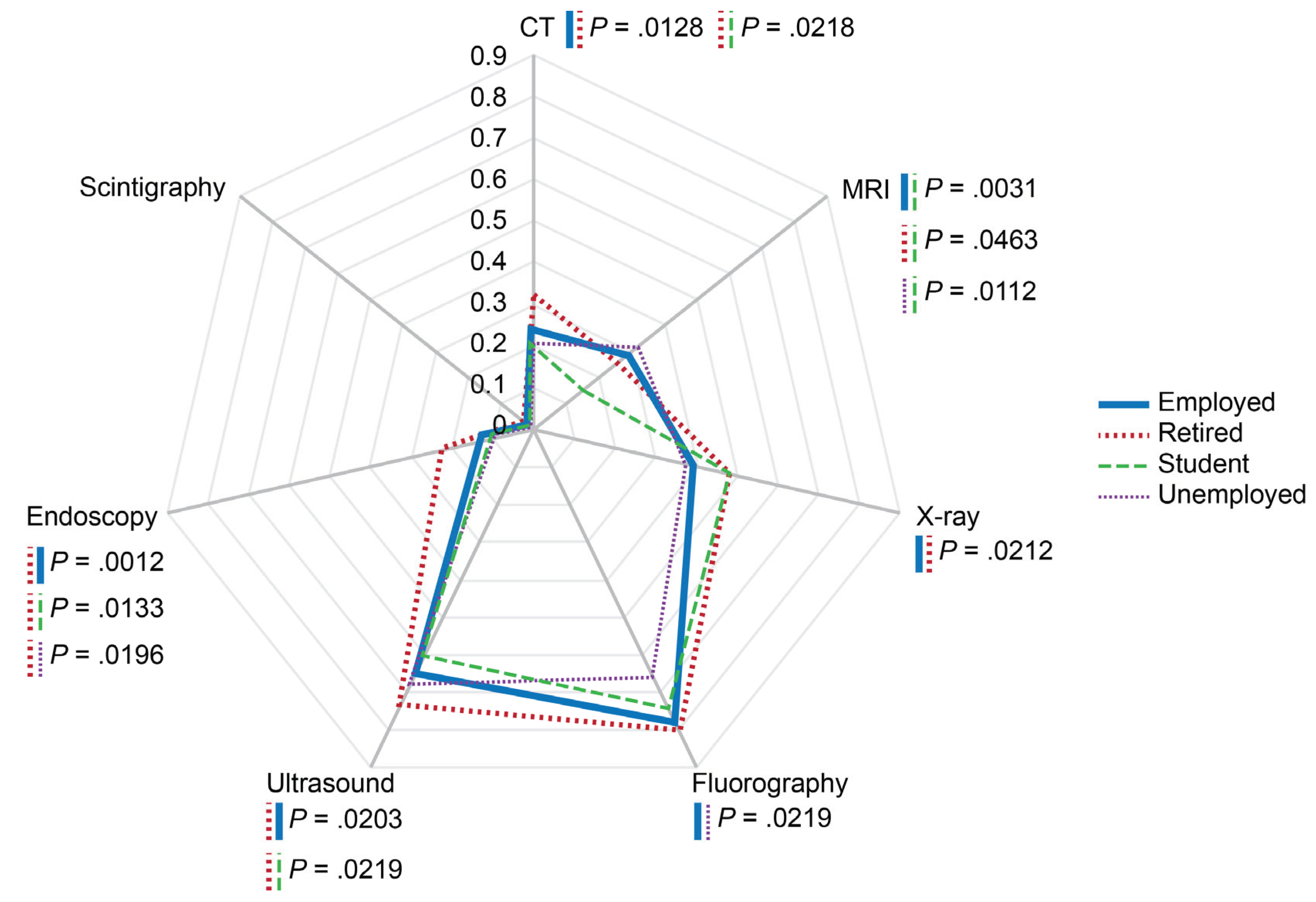

3.5. Professional Status

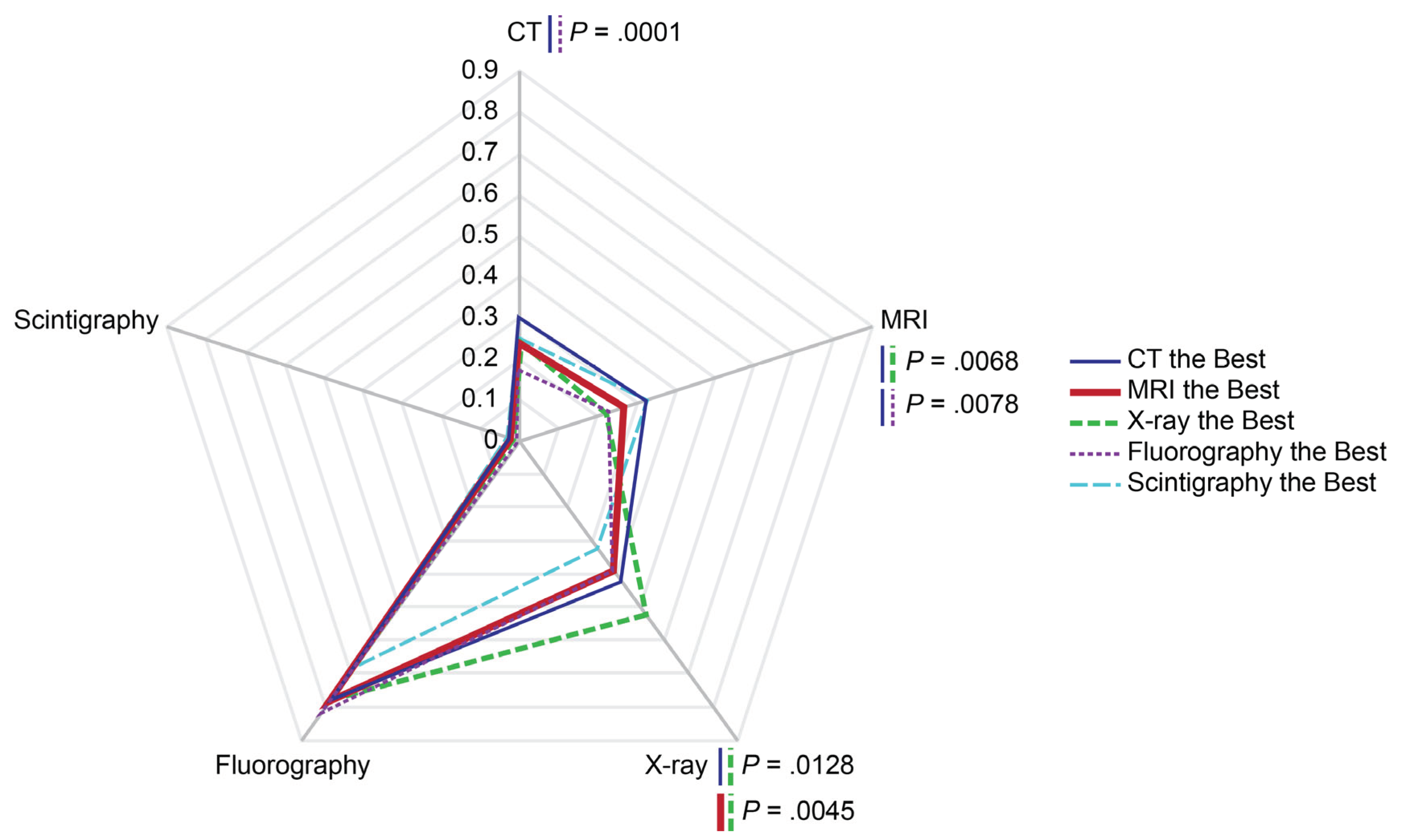

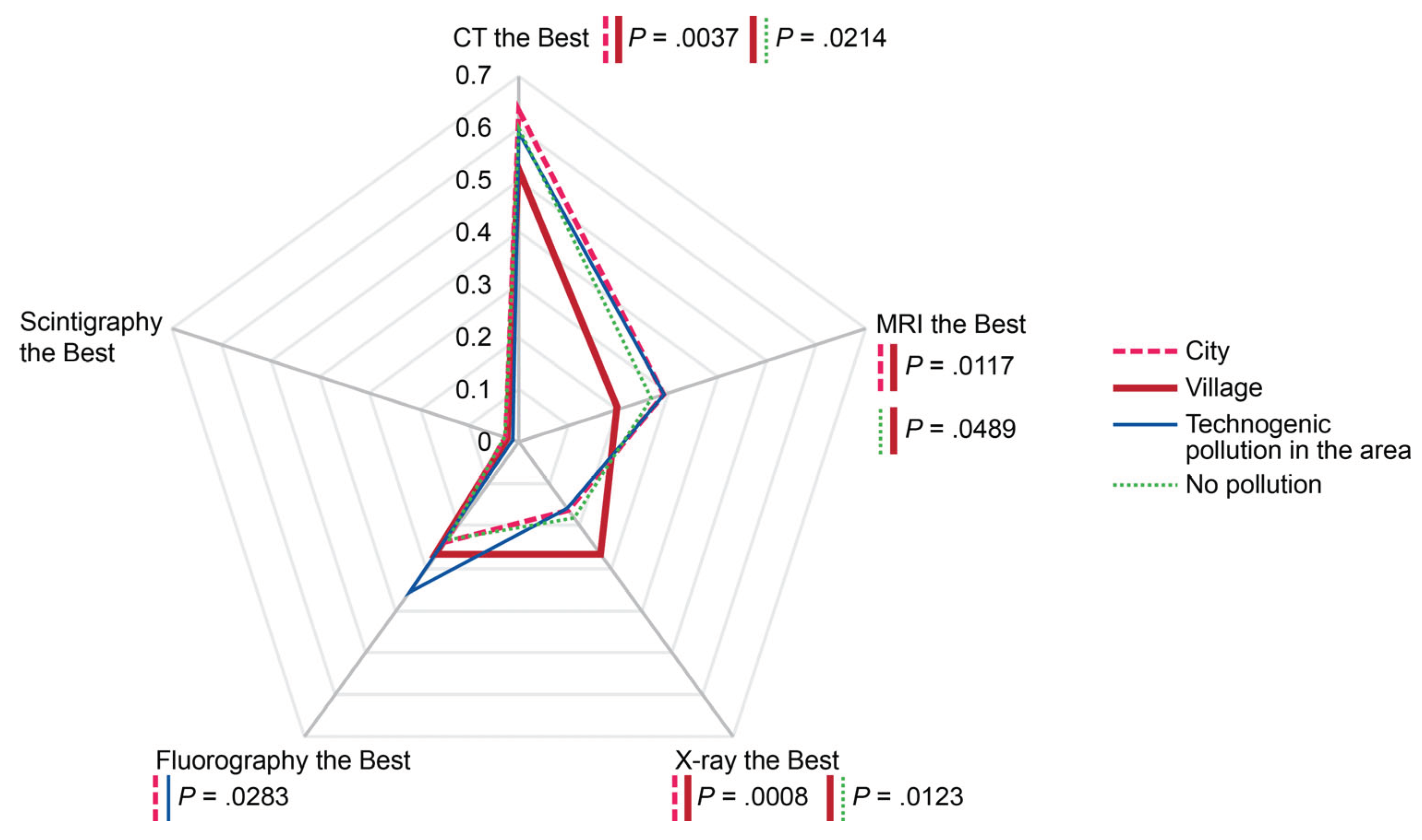

3.6. Perceived Superiority of Diagnostic Imaging Modalities

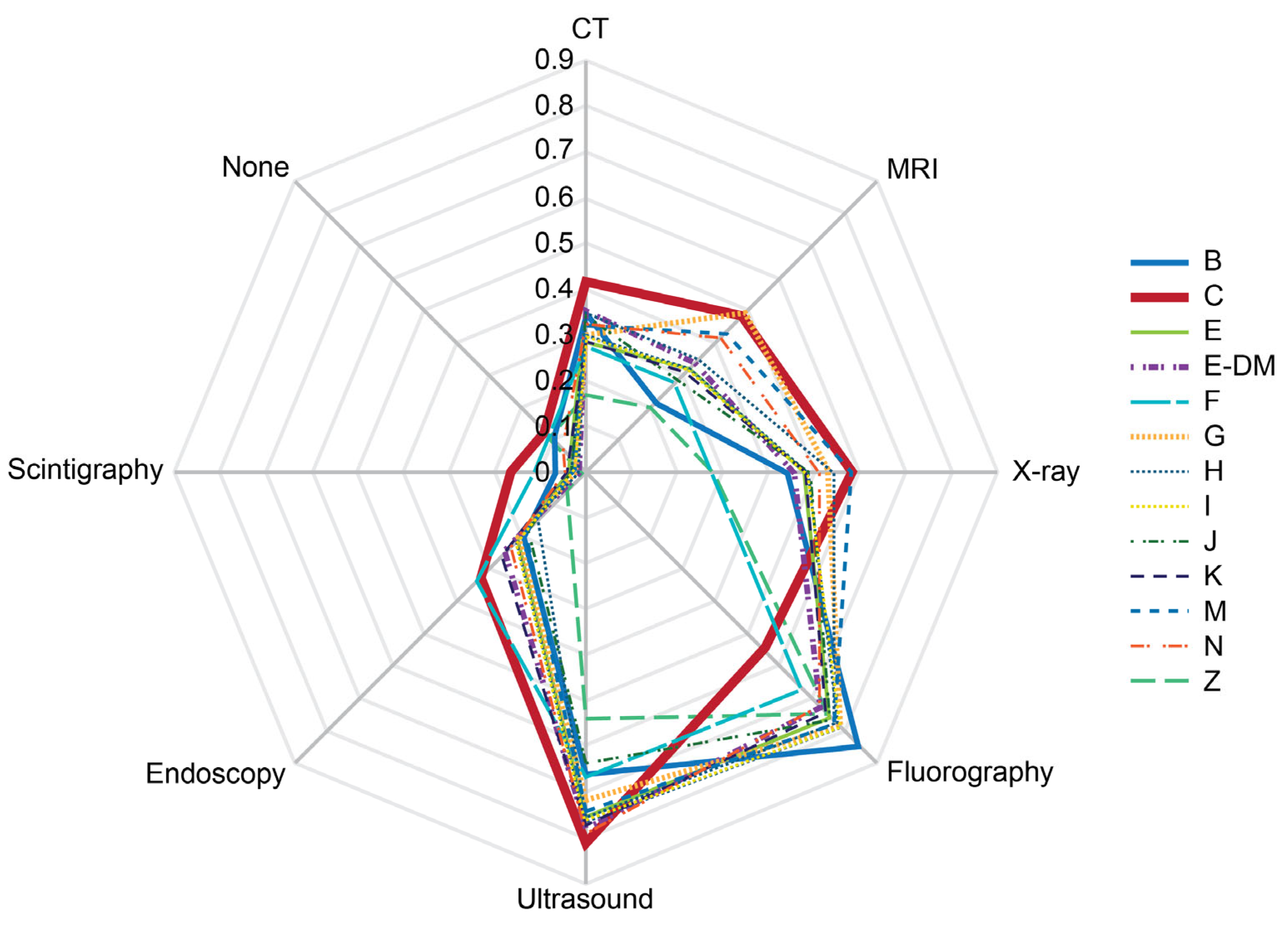

3.7. Local Factors

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fernandez Alonso, C.; Fuentes Ferrer, M.; Llorens, P.; Burillo, G.; Alquézar-Arbé, A.; Jacob, J.; Montero-Pérez, F.J.; Aguiló, S.; Abad Cuñado, V.; Amer Al Arud, L.; et al. Impact of first wave of COVID-19 pandemic on mortality at emergency department in elderly patients with covid and non-covid diagnoses. Gerontology 2023. Dec 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelkovnikova, T.A.; Maksimova, A.S.; Ryumshina, N.I.; Mochula, O.V.; Vaizov, V.K.; Ussov, W.Y.; Anfinogenova, N.D. Transformative Effect of COVID-19 Pandemic on Magnetic Resonance Imaging Services in One Tertiary Cardiovascular Center. J. Imaging 2023, 9, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shelkovnikova, T.A.; Pushnikova, E.Y.; Baev, A.E.; Ryabov, V.V.; Ussov, W.Y. Magnetic resonance syndromes of myocardial damage in patients after new coronavirus infection (COVID-19) - two typical clinical cases. Siberian Journal of Clinical and Experimental Medicine 2022, 37, 135–141, (In Russ.). https://www.sibjcem.ru/jour/article/view/1364. [CrossRef]

- Higgins, V.; Sohaei, D.; Diamandis, E.P.; Prassas, I. COVID-19: from an acute to chronic disease? Potential long-term health consequences. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2021, 58, 297–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Todorovic, V. Mild SARS-CoV-2 infection leaves long-lasting effects on cardiovascular health. Nat. Cardiovasc. Res. 2022, 1, 870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinds, Z.; Lockwood, P. A cross-sectional student survey of the impact of the Covid-19 lockdowns on clinical placement in England. Radiography (Lond.) 2023, 29, 190–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luchian, M.-L.; Higny, J.; Benoit, M.; Robaye, B.; Berners, Y.; Henry, J.-P.; Colle, B.; Xhaët, O.; Blommaert, D.; Droogmans, S.; et al. Unmasking Pandemic Echoes: An In-Depth Review of Long COVID’s Unabated Cardiovascular Consequences beyond 2020. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 3368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, H.E.; Assaf, G.S.; McCorkell, L.; Wei, H.; Low, R.J.; Re'em, Y.; Redfield, S.; Austin, J.P.; Akrami, A. Characterizing long COVID in an international cohort: 7 months of symptoms and their impact. EClinicalMedicine 2021, 38, 101019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Y.; Xu, E.; Bowe, B.; Al-Aly, Z. Long-term cardiovascular outcomes of COVID-19. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Y.; Al-Aly, Z. Risks and burdens of incident diabetes in long COVID: a cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2022, 10, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancini, D.M.; Brunjes, D.L.; Lala, A.; Trivieri, M.G.; Contreras, J.P.; Natelson, B.H. Use of Cardiopulmonary Stress Testing for Patients With Unexplained Dyspnea Post-Coronavirus Disease. JACC Heart Fail. 2021, 9, 927–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, N.W.; Stiles, L.E.; Shaik, R.; Schneider, L.; Muppidi, S.; Tsui, C.T.; Geng, L.N.; Bonilla, H.; Miglis, M.G. Characterization of autonomic symptom burden in long COVID: A global survey of 2,314 adults. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 1012668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demko, Z.O.; Yu, T.; Mullapudi, S.K.; Varela Heslin, M.G.; Dorsey, C.A.; Payton, C.B.; Tornheim, J.A.; Blair, P.W.; Mehta, S.H.; Thomas, D.L.; et al. Post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 (PASC) impact quality of life at 6, 12 and 18 months post-infection. medRxiv [Preprint] 2022, arXiv:2022.08.08.22278543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, M.J.; Cotton, M.; Phan, M.V.T.; Becker, K.; Espasa, M.; Leegaard, T.M.; Lisby, G.; Schneider, U.V.; Casals-Pascual, C. Viral epidemic preparedness: a perspective from five clinical microbiology laboratories in Europe. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2023, 8, S1198-743X(23)00198-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghafoori, M.; Hamidi, M.; Modegh, R.G.; Aziz-Ahari, A.; Heydari, N.; Tavafizadeh, Z.; Pournik, O.; Emdadi, S.; Samimi, S.; Mohseni, A.; et al. Predicting survival of Iranian COVID-19 patients infected by various variants including omicron from CT Scan images and clinical data using deep neural networks. Heliyon 2023, 9, e21965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Gessa, G.; Price, D. Changes in health and social well-being in the COVID-19 clinically vulnerable older English population during the pandemic. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2021, 75, 1070–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bann, D.; Villadsen, A.; Maddock, J.; Hughes, A.; Ploubidis, G.B.; Silverwood, R.; Patalay, P. Changes in the behavioural determinants of health during the COVID-19 pandemic: gender, socioeconomic and ethnic inequalities in five British cohort studies. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2021, 75, 1136–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Questionnaire. Online survey-based clinical study: Risk factors and new challenges for the population on the path to achieving active aging. Available online: https://zdorov.expert/1-1 (accessed on 03 March 2024).

- Online survey-based clinical study: Risk factors and new challenges for the population on the path to achieving active aging. Available online: https://zdorov.tpu.ru/forms (accessed on 03 March 2024).

- Ranjan, Y.; Althobiani, M.; Jacob, J.; Orini, M.; Dobson, R.J.; Porter, J.; Hurst, J.; Folarin, A.A. Remote Assessment of Lung Disease and Impact on Physical and Mental Health (RALPMH): Protocol for a Prospective Observational Study. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2021, 10, e28873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- West, B.T.; Zhang, S.; Wagner, J.; Gatward, R.; Saw, H.W.; Axinn, W.G. Methods for improving participation rates in national self-administered web/mail surveys: Evidence from the United States. PLoS One 2023, 18, e0289695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, P.J.; Roberts, I.; Clarke, M.J.; DiGuiseppi, C.; Woolf, B.; Perkins, C. Methods to increase response to postal and electronic questionnaires. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2023, 11, MR000008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schilling, J.; Klein, D.; Bartholmae, M.M.; Shokouhi, S.; Toepp, A.J.; Roess, A.A.; Sill, J.M.; Karpov, M.V.; Maney, K.; Brown, K.P.; et al. A Digital Health Initiative (COVIDsmart) for Remote Data Collection and Study of COVID-19's Impact on the State of Virginia: Prospective Cohort Study. JMIR Form. Res. 2023, 7, e37550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakhoo, K.; Almario, C.V.; Khalil, C.; Spiegel, B.M.R. Prevalence and Characteristics of Abdominal Pain in the United States. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 19, 1864–1872.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.J.; Poon, C.Y.; O'Connor, S.; Wong, J.Y.H.; Kwok, J.Y.Y.; Choi, E.P.H.; Tsang, W.N.; Wang, M.P. Associations of eHealth literacy and knowledge with preventive behaviours and psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic: a population-based online survey. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e069514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlDukhail, S.; Bahdila, D. Self-perception of health and physical activity among adults before and amidst the COVID-19 pandemic: United States, 2019-2020. Prev. Med. 2022, 158, 107037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, P.; Valtonen, H. Inequalities in perceived health in the Russian Federation, 1994-2012. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Number of COVID-19 cases reported to WHO (cumulative total): Russian Federation. Available online: https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19/cases?m49=643&n=c (accessed on 03 March 2024).

- Federal State Statistics Service (March 17, 2023). Estimation of the resident population as of January 1, 2023 and on average for 2022 and the components of its change (taking into account the results of the All-Russian Population Census of 2020). Available online: https://rosstat.gov.ru/compendium/document/13282 (accessed on 03 March 2024).

- Koyama, A.K.; Imperatore, G.; Rolka, D.B.; Lundeen, E.; Rutkowski, R.E.; Jackson, S.L.; He, S.; Kuklina, E.V.; Park, S.; Pavkov, M.E. Risk of Cardiovascular Disease After COVID-19 Diagnosis Among Adults With and Without Diabetes. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2023, 12, e029696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ussov, W.Y.; Ignatenko, G.A.; Nudnov, N.V.; Bergen, T.A.; Gulyaev, V.M.; Pervak, M.B.; Yaroshevsky, S.P.; Dubovaya, A.V.; Karmazanovsky, G.G. Comprehensive MRI of the chest and brain in the diagnosis of injury to thoracic organs, myocardium, and brain in COVID-19. The University Clinic 2021, Suppl.I, 144–145, (In Russ.). Available online: https://dnmu.ru/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/materConfCovid_010221.pdf.

- Ussov, W.Y.; Nudnov, N.V.; Ignatenko, G.A.; Fisenko, A.Y.; Gulyaev, V.M.; Maritskii, S.V.; Kalyuzhin, V.V.; Lukyanenok, P.I. Evaluation of lung damage in pneumonia, from chest magnetic resonance imaging, in primary diagnosis and in the follow-up of treatment. Medical Visualization 2020, 24, 63–77. Abstract available online: https://medvis.vidar.ru/jour/article/view/914. [CrossRef]

- Ussov, W.Y.; Nudnov, N.V.; Ignatenko, G.A.; Gulyaev, V.M.; Pervak, M.B.; Shelkovnikova, T.A.; Dubovaya, A.V.; Bergen, T.A. Primary and prospective imaging of the chest using magnetic resonance imaging in patients with viral lung damage in COVID-19. Medical Visualization 2020, 24, 11–26. Abstract available online: https://medvis.vidar.ru/jour/article/view/967. [CrossRef]

- Halfmann, M.C.; Luetkens, J.A.; Langenbach, I.L.; Kravchenko, D.; Wenzel, P.; Emrich, T.; Isaak, A. Cardiac MRI Findings in Patients Clinically Referred for Evaluation of Post-Acute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohseni, A.; Di Girolamo, A.; Cangiano, R.; Ascione, M.; di Marzo, L.; Mansour, W. High-Grade Infection after Branched Endovascular Aortic Repair in Patient with Recent COVID-19 Hospitalization. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anfinogenova, N.D.; Sinitsyn, V.E.; Kozlov, B.N.; Panfilov, D.S.; Popov, S.V.; Vrublevsky, A.V.; Chernyavsky, A.; Bergen, T.; Khovrin, V.V.; Ussov, W.Y. Existing and Emerging Approaches to Risk Assessment in Patients with Ascending Thoracic Aortic Dilatation. J. Imaging 2022, 8, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostberg, N.P.; Zafar, M.A.; Ziganshin, B.A.; Elefteriades, J.A. The Genetics of Thoracic Aortic Aneurysms and Dissection: A Clinical Perspective. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babar, M.; Jamil, H.; Mehta, N.; Moutwakil, A.; Duong, T.Q. Short- and Long-Term Chest-CT Findings after Recovery from COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilev, Y.; Blokhin, I.; Khoruzhaya, A.; Kodenko, M.; Kolyshenkov, V.; Nanova, O.; Shumskaya, Y.; Omelyanskaya, O.; Vladzymyrskyy, A.; Reshetnikov, R. Routine Brain MRI Findings on the Long-Term Effects of COVID-19: A Scoping Review. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 2533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, R.; Bahadur, A.R.; Singh, S.B.; Sher, J.; Todua, M.; Moradi, L.; Bastakoti, S.; Arslan, M.; Ajmal, H.; Lee, G.Y.; et al. Neurological and Psychiatric Manifestations of Long COVID-19 and Their [18F]FDG PET Findings: A Review. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Pelsemaeker, M.C.; Guiot, Y.; Vanderveken, J.; Galant, C.; Van Bockstal, M.R. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic and the Associated Belgian Governmental Measures on Cancer Screening, Surgical Pathology and Cytopathology. Pathobiology 2021, 88, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keizman, E.; Ram, E.; Kachel, E.; Sternik, L.; Raanani, E. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on cardiac surgery in Israel. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2020, 15, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saban, M.; Reznik, A.; Shachar, T.; Wilf-Miron, R.; Sivan-Hoffmann, R. The effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on ED referrals and care for stroke patients: A four-year comparative study. J. Crit. Care 2021, 62, 230–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartnett, K.P.; Kite-Powell, A.; DeVies, J.; Coletta, M.A.; Boehmer, T.K.; Adjemian, J.; Gundlapalli, A.V.; National Syndromic Surveillance Program Community of Practice. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Emergency Department Visits - United States, January 1, 2019-May 30, 2020. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020, 69, 699–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anfinogenova, N.D.; Trubacheva, I.A.; Popov, S.V.; Efimova, E.V.; Ussov, W.Y. Trends and concerns of potentially inappropriate medication use in patients with cardiovascular diseases. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2021, 20, 1191–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anfinogenova, N.D.; Novikova, O.M.; Trubacheva, I.A.; Efimova, E.V.; Chesalov, N.P.; Ussov, W.Y.; Maksimova, A.S.; Shelkovnikova, T.A.; Ryumshina, N.I.; Stepanov, V.A.; et al. Prescribed Versus Taken Polypharmacy and Drug–Drug Interactions in Older Cardiovascular Patients during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Observational Cross-Sectional Analytical Study. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 5061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoven, H.; Backhaus, I.; Gerő, K.; Kawachi, I. Characteristics of employment history and self-perceived barriers to healthcare access. Eur. J. Public Health 2023, 33, 1080–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Yu, C.; Qu, J.; Zhang, L.; Jiang, S.; Huang, D.; Chen, B.; Zhang, Z.; Guan, W.; Ling, Z.; et al. Imaging and clinical features of patients with 2019 novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2020, 47, 1275–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakaş, H.M.; Yıldırım, G.; Çiçek, E.D. The reliability of low-dose chest CT for the initial imaging of COVID-19: comparison of structured findings, categorical diagnoses and dose levels. Diagn. Interv. Radiol. 2021, 27, 607–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahanmehr, N.; Bigdeli, A.S.; Salari, H.; Mokarami, H.; KhodaKarim, S.; Damiri, S. Analyzing inappropriate magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) prescriptions and resulting economic burden on patients suffering from back pain. Int. J. Health Plann. Manage. 2019, 34, e1437–e1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karpov, A.B.; Takhauov, R.M.; Zerenkov, A.G.; Semenova, Y.V.; Bogdanov, I.M.; Kazantceva, S.B.; Blinov, A.P.; Kalinkin, D.E.; Gorina, G.V.; Litvinova, O.V.; et al. Descriptive characteristics of occupational exposures and medical follow-up in the cohort of workers of the Siberian Group of Chemical Enterprises in Seversk, Russia. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 2021, 97, 848–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdorf, B.T. Comparing magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography machine accessibility among urban and rural county hospitals. J. Public Health Res. 2021, 11, 2527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, L.E.; Gruber, S.; Lee, H.; Dahabreh, I.J.; Stuart, E.A.; Williamson, B.D.; Wyss, R.; Díaz, I.; Ghosh, D.; Kıcıman, E.; et al. A causal roadmap for generating high-quality real-world evidence. J. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2023, 7, e212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).