1. Introduction

Currently, more than 20% of the EU-27 population are aged 65 years and over and projections suggest an increase to 31.3% by 2100 [

1]. An ageing population comes with the increased risk of non-communicable diseases that have the potential to precipitate a healthcare crisis [

2]. This potential healthcare crisis will be further perpetuated by physical inactivity, which is the fourth leading cause of death worldwide, costing approximately US

$67.5 billion per year to health care systems globally [

3]—making it imperative to promote healthy, active ageing.

The promotion of active lifestyles and healthy ageing is contingent on social and community networks, and general socioeconomic, cultural, and environmental conditions as well as upon the individual [

4]. Previous studies have provided insight into barriers and facilitators for having an active life [

5,

6,

7,

8] and its effects on ageing [

9,

10]. The domains that these studies identified included: personal, environmental, ecological, socio-cultural, economic and political issues. The integration of such information included in several of these domains previously identified (i.e.; community health assets, individual and environmental data) [

10] is important to design feasible interventions to promote physical activity. Citizen science can play a key role in capturing the influence of these domains by enabling active participation of the general population in research projects. It could be through the engagement in steering committees/advisory councils of the active living projects [

11] and by providing data via ecological momentary assessments (EMAs) that capture active living prospectively [

12,

13]. The implementation of such citizen science methodology helps to provide more insights into the strategies to promote healthy living considering the smart city infrastructure [

5].

The objectives of this study are: (1) to co-design and prototype, in a community of stakeholders, a mHealth intervention to promote active living and to identify barriers and facilitators for active living in individuals older than 55 years; (2) to test the performance of the intervention in a pilot study.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Community of Stakeholders

Every Walk You Take started with the constitution of a community of stakeholders that acted as the steering committee of the project. Citizens, researchers, health professionals, health planners, policymakers, and teachers, familiar with the social and economic burden of aging in developed societies took part of this community that had representatives from both economically deprived and privileged areas of the city. The public-owned life-long learning centres of two deprived neighbourhoods of Barcelona (Trinitat Vella and Bon Pastor) were the executive offices of the project and meeting points for the community of stakeholders. They had the following responsibilities: (1) to supervise the project management in periodic meetings; (2) to co-design and prototype Every Walk You Take mHealth intervention addressed to promote active living; (3) to discuss and interpret the data collected in the pilot study, and (4) to codesign the communication strategy of the project.

2.2. Pilot Study

The mHealth intervention co-designed and prototyped by the community of stakeholders was tested in a pilot study conducted in two 7-day cycles, one in each neighbourhood (Trinitat Vella and Bon Pastor). All the citizen scientists included were aged 55 or over and owned a smartphone. The estimated sample size was 15 citizen scientists according to the most recent usability studies [

14,

15].

All citizen scientists attended a 2-h formative session in the corresponding life-long learning centre according to their neighbourhood of residence. During that session, the citizen scientists learned to download, register, and use the mobile app, and to register EMAs to capture the barriers and facilitators for active living. All the questions that arose during the sessions regarding the functioning of the app were answered. Citizen scientists were also encouraged to use all functionalities of the application: (1) to answer the project questionnaires (socio-demographic data), (2) to follow the personalized recommendations according to individual preferences and environmental data and (3) to register EMAs using the app installed in their own smartphones. The citizen scientists were prompted to take pictures and to describe, using an audio recording, if they perceived their environment indoor or outdoor) to be either a barrier or a facilitator of active living. These images and audio recordings were automatically geo-coded to the exact latitude-longitude location as measured via smartphone-based location services. The study was approved by the local ethics committee.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

To describe the sample included, the mean and the standard deviation for continuous variables and the proportions for categorical variables were estimated as appropriate. The EMAs (pictures and voice notes) were analyzed to reveal patterns of perceptions (i.e.; barriers and facilitators) for active living in the community of stakeholders. Moreover, intrinsic motivations at individual level and key factors at an environmental level were identified.

3. Results

Every Walk You Take was conducted between June and December of 2023 in Trinitat Vella and Bon Pastor, two neighbourhoods in the city of Barcelona.

3.1. Co-Design and Validation of the mHealth Intervention

The mHealth intervention to promote physical activity in individuals older than 55 years was co-designed with 10 community leaders familiar with the social and economic burden of aging in developed societies (e.g.; two citizen scientists, one researcher, one health professional, one policy maker, two teachers and three community agents).

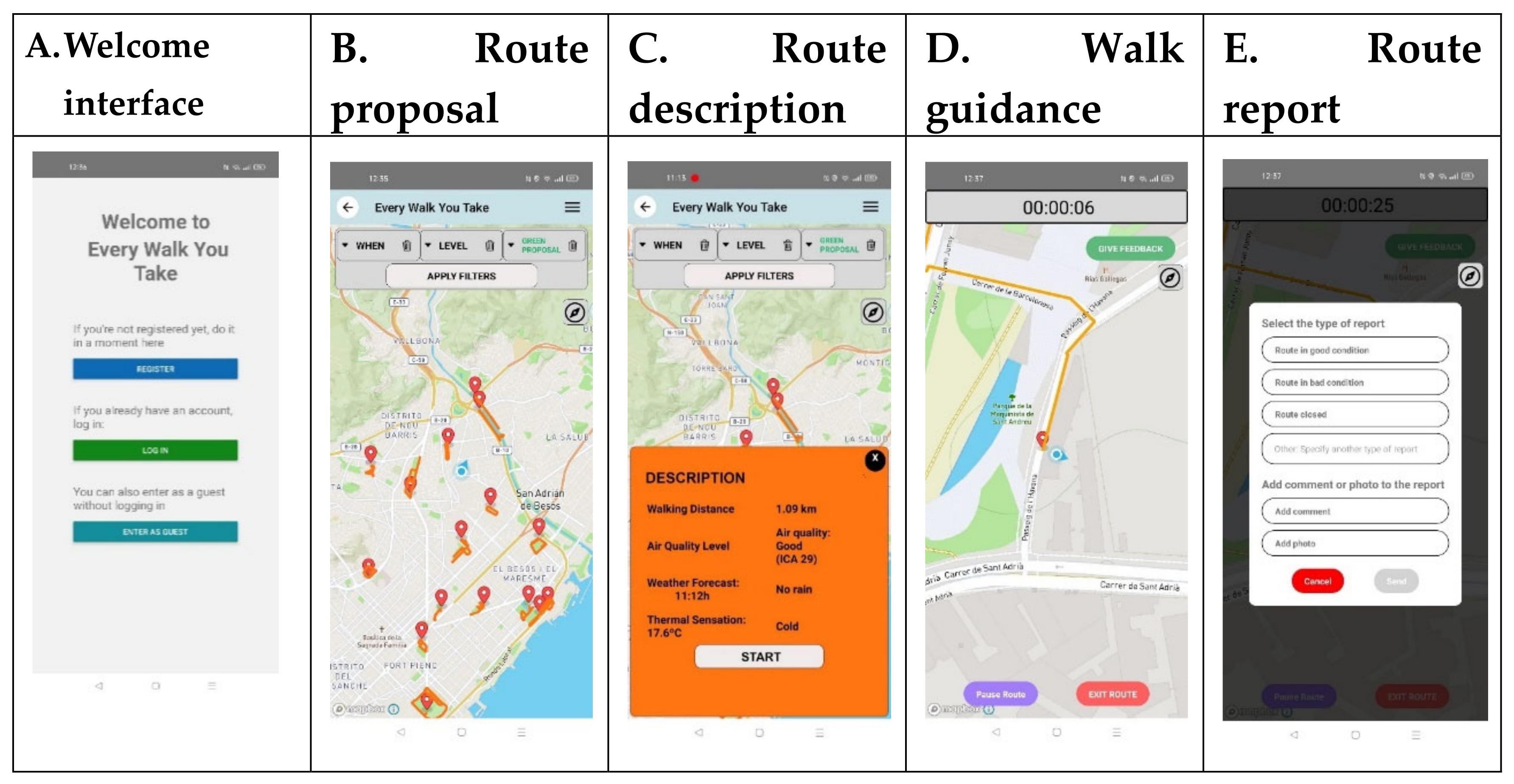

In a meeting held in June 2023, this community agreed that a mobile app was the best channel for the co-designed mHealth intervention and the functionalities that such app were discussed. In September 2023, the first prototype of the mobile app was presented to the community of stakeholders. This app was designed with a user experience adapted to the target population (i.e.; people older than 55 years). The app recommended healthy routes in the city, defined as routes that maximize passage through pedestrian-friendly areas (parks, pedestrian lanes and streets). The recommendations took into account environmental variables in the current global context of climate crisis (i.e.; air quality and climate), personal preferences (i.e.; route difficulty and distance) and geolocalization; as well as barriers and facilitators to perform the routes, previously identified through EMAs (collection of pictures and voice notes) considering material and emotional perceptions captured by all citizen scientists. The application was multilingual (English, Spanish or Catalan) (

Figure 1). This prototype was validated by the community of stakeholders.

3.2. Pilot Study

The study included 21 citizen scientists with mean age 67 (standard deviation 7), 86% were female. The most common education level was primary studies (76%), followed by university studies (14%) and secondary level (10%) (

Table 1).

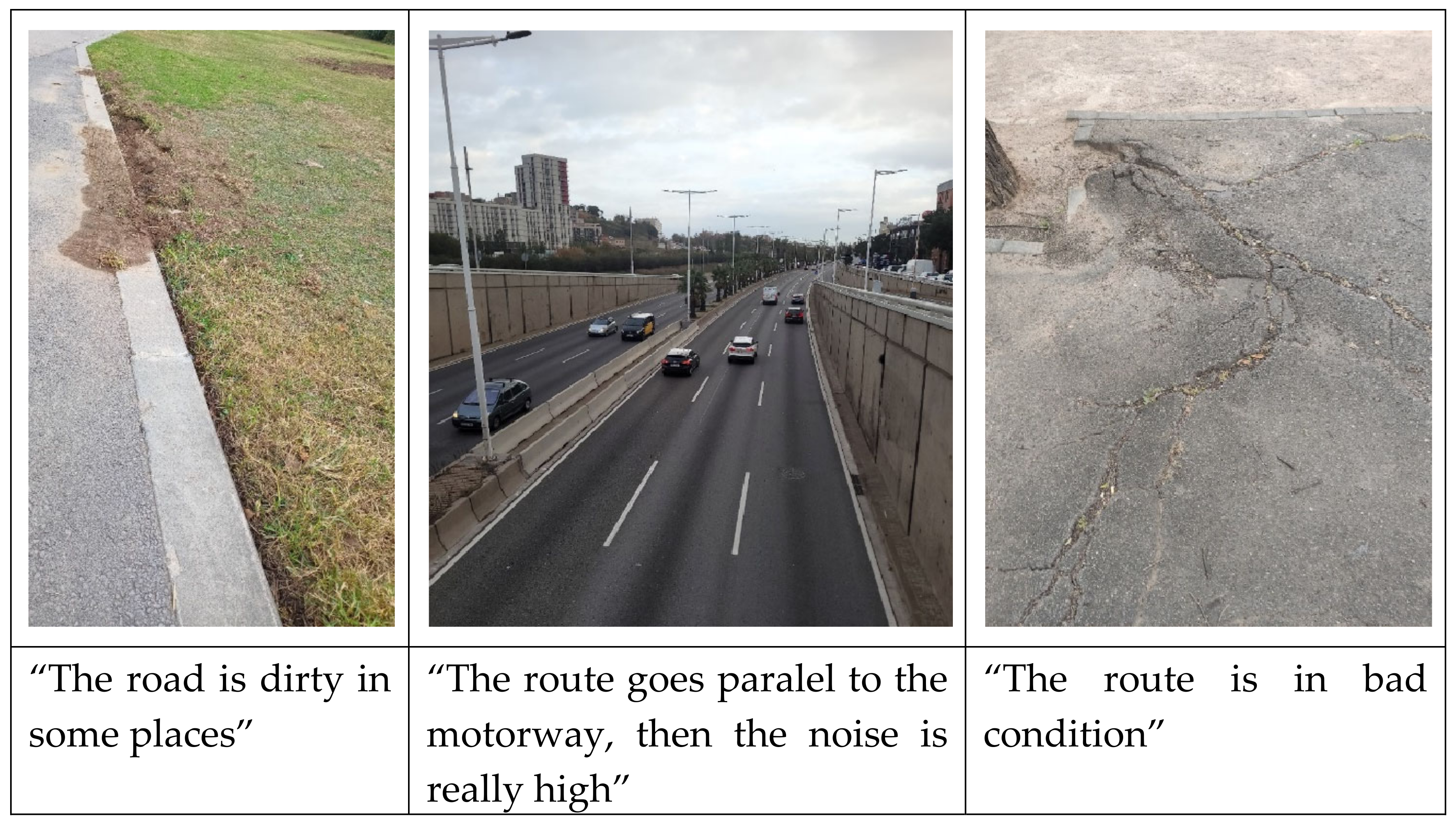

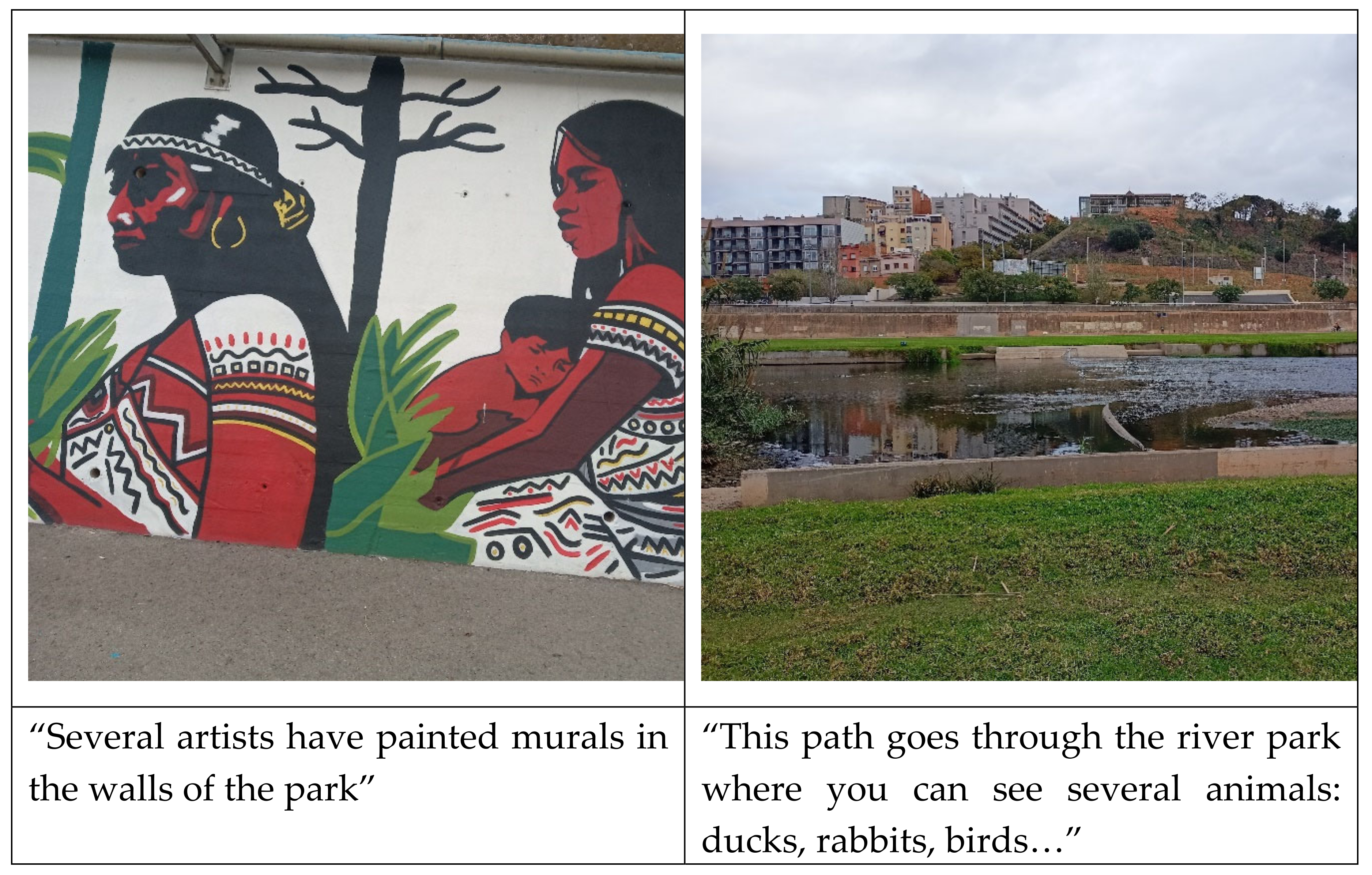

During the pilot study, a total of 112 EMAs were collected. Particularly, 64 reports were sent, 92% of them pointed out that the routes were in good condition. In addition, the citizen scientists sent 48 pictures of the barriers and facilitators identified for active living.

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 include examples of the images and the associated reports of the barriers and facilitators, respectively. Thus, the barriers most commonly described were related to dirtiness and damaged roads; whereas the facilitators included murals on the roads and urban green spaces.

4. Discussion

Every Walk You Take, a mHealth intervention that promoted physical activity through the recommendation of healthy routes in the city, helped to identify barriers and facilitators for active living in individuals older than 55 years. This comprehensive mHealth intervention provided the best choice of healthy routes (i.e.; community health asset) outlined by considering information on determinants of health from an individual perspective (e.g.; age, physical condition and geolocalization), and from the community perspective (e.g.; environmental variables—air quality and climate—and city infrastructures to that end—parks, pedestrian streets and lanes). In addition, the co-designed mobile app allowed for the evaluation of the barriers and facilitators in following the proposed routes considering material and emotional perceptions. Thus, this intervention has the potential to be implemented in different cities around the world that collect information on community determinants of health and health assets.

4.1. Citizen Science as a Tool to Improve Health Literacy

There are scientific and societal implications derived from the lack of diversity in citizen science participants [

16]. In Every Walk You Take, to tackle the issue of underrepresentation of people from deprived areas, we focused our efforts within the economically disadvantaged Barcelona neighbourhoods of Trinitat Vella and Bon Pastor. In this context, community engagement strategies are crucial, as indicated in the Smart Framework, which integrates citizen science with community-based participatory research [

11]. Through the inclusion of community leaders in our stakeholder community, we could increase the effectiveness of health interventions [

17].

We established a scientific collaboration with the public network of life-long learning centres in the neighbourhoods. These centres offer a set of learning activities that, within the framework of life-long learning, allows adults to develop their capabilities, enrich their knowledge and improve their technical and professional skills. The executive office of this citizen science project was the life-long learning centers. Thus, the meetings of the community of stakeholders, the formative sessions and the pilot study were conducted in such dependencies. Most of the included citizen scientists were students attending an alphabetization course that also covered basic computer skills. Every Walk You Take significantly contributed to these learnings, for the following two reasons: firstly, the citizen scientists put into practice the theoretical content acquired at the life-long learning centre classes by validating a new mobile app designed for individuals older than 55 [

18]. Secondly, the strategies for improving healthy behaviour and reducing health inequalities may benefit from adopting a stronger focus on health literacy within prevention and public health interventions [

19]. Thus, our citizen scientists, most of them with primary studies, might have benefited from the relationship between educational attainment and healthy behaviour. Indeed, the World Health Organization, in the conceptual framework for action in the social determinants of health, identified education as an inequality axis [

20]. Concurring with this, Wister et al. highlighted that programs and policies that encourage life-long and life-wide educational resources and practices by older persons are needed [

21]. In consequence, the existence of a public network of life-long learning centres, like the centres involved in Every Walk You Take, has important benefits for the most vulnerable groups.

4.2. Barriers and Facilitators for Active Living

Using EMAs, images of the barriers to active living, captured and uploaded by the citizen scientists noteworthy insights into their perceptions and revealed significant patterns within the barriers they encountered. Concurring with previous publications, the most common observation regarded the bad state of road, which acted as a deterrent hindering their inclination towards walking and partaking in physical activities [

22,

23]. This observation highlights a key point of consideration for policymakers and urban planners. The negative impact of dirty or damaged roads on citizen scientists’ motivation to engage in physical activity proves that city infrastructure influences the public’s inclination toward adopting active lifestyles. This relationship is particularly important in low income neighbourhoods where walkability, (defined as the extent to which the built environment is friendly to the presence of people living, shopping, visiting, enjoying or spending time in an area); was related to healthier weight status [

24]. By addressing these issues, policymakers possess the ability to support healthier lifestyle choices, ultimately benefiting the overall well-being of communities. Conversely, the images of facilitators uploaded and described by the citizen scientists were varied—some people were impressed by murals on the roads, which made their walks more enjoyable and stimulating, while others were pleased by being surrounded by nature and found this to be a serene experience that motivated them to engage in more physical activity. Thus, there are general public benefits from investments in art, culture and green spaces as these are aesthetically attractive to see and pleasurable to be around. Concurring with this observation, Balcetis et al. also pointed out that neighbourhoods with visually engaging, eye-catching objects and locations increase the frequency, duration, and vigorousness of residents’ and visitors’ exercise [

25]. New possibilities for the development of urban spaces could derive from co-design practices. In fact, the implications that city infrastructures have on health requires the diversification of the group of stakeholders involved. The aim is to reconfigure urban spaces and to translate the diverse user perspectives on urban life to planning practices, since these interventions can impact the socio-technical development of the city [

26].

This study has several limitations. On the one hand, an unbalanced gender representation within the sample, with a majority of participants being women. This introduces potential gender-based biases, which would impact the generalisability of the findings. The overrepresentation of women could skew perspectives and insights that have been gathered from the study, which limits a comprehensive understanding of active living barriers and facilitators among diverse gender demographics. This gender imbalance might reflect a propensity among women to participate in health-related initiatives more readily than men. Therefore, to address this limitation in future studies, further efforts should be made to ensure that recruitment strategies are inclusive and balanced; this could be done by emphasising the benefits of participation [

16]. On the other hand, this project aimed to validate a prototype of Every Walk You Take mHealth intervention, but no information was collected on its effect on the citizen scientists’ health status (e.g.; quality of life). Further randomized controlled trials should be performed to evaluate the effectiveness of such an intervention, particularly by taking into account the compliance of citizen scientists in using EMAs to report data [

27].

5. Conclusions

Every Walk You Take tackles three core objectives of public health policy: prevention, protection, and health promotion. The project is directly involved in health promotion as it increases the health literacy of the citizens of Barcelona, empowering them to play an active part in their own healthcare. Further to this, it provides the foundation for the development of novel models of health surveillance to address gaps in the current research landscape of active living. Moreover, the increased healthy literacy of the individuals ensures that they are more conscious about the role of physical activity in healthy ageing.

Funding

IMPETUS: European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation programme under grant agreement number 101058677.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Bioethics committee of the University of Barcelona (#IRB00003099).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the management teams and the students of the life-long learning centers Trinitat Vella and Bon Pastor in Barcelona and Laura Lopez Crespo for her contribution to the project dissemination.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Eurostat. The home of high-quality statistics and data on Europe. 2024. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat.

- World Health Organization. Noncommunicable diseases. 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases.

- Ding, D.; Lawson, K.D.; Kolbe-Alexander, T.L.; Finkelstein, E.A.; Katzmarzyk, P.T.; van Mechelen, W.; Pratt, M.; Lancet Physical Activity Series 2 Executive Committee. The economic burden of physical inactivity: A global analysis of major non-communicable diseases. Lancet 2016, 388, 1311–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahlgren, G.; Whitehead, M. European strategies for tackling social inequities in health: Levelling up Part 2. 2006. Available online: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0018/103824/E89384.pdf.

- Odunitan-Wayas, F.A.; Hamann, N.; Sinyanya, N.A.; King, A.C.; Banchoff, A.; Winter, S.J.; Hendricks, S.; Okop, K.J.; Lambert, E.V. A citizen science approach to determine perceived barriers and promoters of physical activity in a low-income South African community. Glob Public Health 2020, 15, 749–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winter, S.J.; Goldman Rosas, L.; Padilla Romero, P.; Sheats, J.L.; Buman, M.P.; Baker, C.; King, A.C. Using Citizen Scientists to Gather, Analyze, and Disseminate Information About Neighborhood Features That Affect Active Living. J Immigr Minor Health 2016, 18, 1126–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katapally, T.R.; Rainham, D.; Muhajarine, N. Factoring in weather variation to capture the influence of urban design and built environment on globally recommended levels of moderate to vigorous physical activity in children. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e009045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katapally, T.R.; Bhawra, J.; Leatherdale, S.T.; Ferguson, L.; Longo, J.; Rainham, D.; Larouche, R.; Osgood, N. The SMART Study, a Mobile Health and Citizen Science Methodological Platform for Active Living Surveillance, Integrated Knowledge Translation, and Policy Interventions: Longitudinal Study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2018, 4, e31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrie, H.; Soebarto, V.; Lange, J.; Mc Corry-Breen, F.; Walker, L. Using Citizen Science to Explore Neighbourhood Influences on Ageing Well: Pilot Project. Healthcare 2019, 7, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, G.E.R.; Pykett, J.; Daw, P.; Agyapong-Badu, S.; Banchoff, A.; King, A.C.; Stathi, A. The Role of Urban Environments in Promoting Active and Healthy Aging: A Systematic Scoping Review of Citizen Science Approaches. J Urban Health 2022, 99, 427–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katapally, T.R. The SMART Framework: Integration of Citizen Science, Community-Based Participatory Research, and Systems Science for Population Health Science in the Digital Age. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2019, 7, e14056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katapally, T.R.; Chu, L.M. Digital epidemiological and citizen science methodology to capture prospective physical activity in free-living conditions: A SMART Platform study. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e036787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hognogi, G.G.; Meltzer, M.; Alexandrescu, F.; Ștefănescu, L. The role of citizen science mobile apps in facilitating a contemporary digital agora. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 2023, 10, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, J.L.; Codern-Bové, N.; Zomeño, M.D.; Lassale, C.; Schröder, H.; Grau, M. Quantitative and qualitative evaluation of the COMPASS mobile app: A citizen science project. Inform Health Soc Care 2021, 46, 412–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhns, L.M.; Hereth, J.; Garofalo, R.; Hidalgo, M.; Johnson, A.K.; Schnall, R.; Reisner, S.L.; Belzer, M.; Mimiaga, M.J. A Uniquely Targeted, Mobile App-Based HIV Prevention Intervention for Young Transgender Women: Adaptation and Usability Study. J Med Internet Res 2021, 23, e21839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pateman, R.M.; Dyke, A.; West, S.E. The Diversity of Participants in Environmental Citizen Science. Citizen Science: Theory and Practice. ISSN 2057–4991.

- Phillips, T.B.; Ballard, H.L.; Lewenstein, B.V.; Bonney, R. Engagement in science through citizen science: Moving beyond data collection. Science Education 2019, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iancu, I.; Iancu, B. Designing mobile technology for elderly. A theoretical overview. Technol Forecast Soc Change 2020, 155, 119977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friis, K.; Lasgaard, M.; Rowlands, G.; Osborne, R.H.; Maindal, H.T. Health Literacy Mediates the Relationship Between Educational Attainment and Health Behavior: A Danish Population-Based Study. J Health Commun 2016, 21 (Suppl. 2), 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solar, O.; Irwin, A. A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health. Social Determinants of Health Discussion. Paper 2 (Policy and Practice). 2010. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241500852.

- Wister, A.V.; Malloy-Weir, L.J.; Rootman, I.; Desjardins, R. Lifelong educational practices and resources in enabling health literacy among older adults. J Aging Health 2010, 22, 827–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, R.L.; Maantay, J.A.; Fahs, M. Promoting Active Urban Aging: A Measurement Approach to Neighborhood Walkability for Older Adults. Cities Environ 2010, 3, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gkavra, R.; Nalmpantis, D.; Genitsaris, E.; Naniopoulos, A. The walkability of Thessaloniki: Citizens’ perceptions. In Conference on Sustainable Urban Mobility 191–198. Cham: Springer International Publishing. 2018.

- Van Cauwenberg, J.; Van Holle, V.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Van Dyck, D.; Deforche, B. Neighborhood walkability and health outcomes among older adults: The mediating role of physical activity. Health & place 2016, 37, 16–25. [Google Scholar]

- Balcetis, E.; Cole, S.; Duncan, D.T. How Walkable Neighborhoods Promote Physical Activity: Policy Implications for Development and Renewal. Policy Insights Behav Brain Sci 2020, 7, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munthe-Kaas, P. Agonism and co-design of urban spaces. Urban Res Prac 2015, 8, 218–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katapally, T.R.; Hammami, N.; Chu, L.M. A randomized community trial to advance digital epidemiological and mHealth citizen scientist compliance: A smart platform study. PloS One 2021, 16, e0259486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).