To define the following terms, we have carried out extensive research in the major and most authoritative dictionaries and encyclopedias. In particular, we found C. Guastella [

11] and F. Masci [

12] work particularly enlightening. Although inherently indefinable, knowledge can be described as expressing a unique relationship between the mind and any object, whereby the object exists not only in itself but also for consciousness. It is therefore an active operation of the spirit, occurring under certain conditions and presupposing three elements: a subject that knows, an object known, and a specific relationship between the two (author’s translation of "Conoscenza" in [

13]). The definition provided by the resources sometimes refers to other terms that need definition but is not within our scope or belongs to specific contexts for which it is not adequate. In this regard, we considered it appropriate to depart slightly from the original text of the definition reported by the resource to adapt it to our needs. We would like to clarify, however, that the coherence of meaning was solidly maintained so that there was a hierarchical dependence between the definitions: each term is used only after it has been defined and each use of a defined term has been highlighted to show the dependence between one definition and another.

2.1. Language and communication

Definition 1.

An alphabet is a finite set of symbols [MWE] [CAM] [COL] [BRI].

Consider, for example, the alphabet made up of the English alphabet, consisting of 26 symbols from A to Z, plus the space symbol .

Definition 2.

A string is a contatenation of a finite set of symbols from an alphabet[MWE] [CAM] [COL] [BRI].

From the alphabet, GJWQTUT, TILE, EYVLY, KEYBOARD are examples of strings. The concatenation of strings is a string.

Definition 3.

A dictionary is a finite set of string s, called word s [MWE] [COL].

Definition 4.

An expression is a concatenations of finite set of word s.

[MWE] and [COL] defines an expression as “something that manifests, embodies, or symbolizes something else”. To avoid clutter, we shall no longer indicate the character with its explicit representation but with the graphic symbol of space-between-words as usual. Then, TILE GJWQTUT KEYBOARD TILE is an example of expression, this is simply string concatenation without any constraint.

Definition 5.

A grammar is a finite set of rules of concatenation of symbols, word s and expression s to form clause s [MWE] [CAM] [COL] [BRI].

In particular, [BRI] defines grammar as “rules of a language governing the sounds, words, sentences, and other elements, as well as their combination and interpretation” where we have not yet introduced the concepts of sentences and interpretation (which evidently the dictionary can use). The expression TILE GJWQTUT GJWQTUT is not a clause while KEYBOARD IS A TILE is (given that IS and A are within the dictionary and play the correct role in accordance with the rules of the given grammar).

Clause are generally defined as “a group of words containing a subject and predicate and functioning as a member of a complex”[MWE] or “the part of sentence with a subject and a verb”[CAM]. This allows us to use clauses as the building blocks for the construction of sentences. Now we can build clauses but we cannot yet guarantee that their content is meaningful as there are no constraints to not construct strings like THE THREADY CHAIR IS HEALED.

Definition 6.

A language is a pair formed by analphabet and a grammar[MWE] [CAM].

Given an alphabet it is possible to generate multiple languages by modifying the grammar and vice versa.

Definition 7.

A sentence is a concatenations of finite set of clause s according to the rules of grammar

.

In [MWE] a sentence is “a word, clause, or phrase or a group of clauses or phrases forming a syntactic unit which expresses an assertion, a question, a command, a wish, an exclamation, or the performance of an action, that in writing usually begins with a capital letter and concludes with appropriate end punctuation, and that in speaking is distinguished by characteristic patterns of stress, pitch, and pauses” and in [COL] is “a sentence is a group of words which, when they are written down, begin with a capital letter and end with a full stop, question mark, or exclamation mark”. Basically it is a complete construction contained between distinctive signs that mark the beginning and the end making it significant and complete. We cannot absolutely establish whether the sentence THE THREADY CHAIR IS HEALED is significant (i.e. whether all the information that was intended to be transmitted has actually been codified), but we can define, with respect to a frame of reference, how informative it is that is (i.e. how much information content has actually been encoded).

Definition 8.

information is the meaning of a sentence[MWE] [CAM] [COL] [BRI].

Definition 9.

communication is a process by which information s is exchanged [MWE] [CAM] [COL] [BRI].

In a purely linguistic study, we would have to engage in semantic analysis. However, in a more general context, we aim to gauge the “measure” of information encoded within a sentence so that, between a maximum (which we could assume as 1) and a minimum (which we could assume as 0), if the information in the sentence is 0, no meaningful communication has taken place. The term meaningful is added to distinguish the absence of communication from the absence of meaningful communication, indicating even the mere attempt at communication is itself an information, contributing to the overall measure of information. The lack of meaningful communication does not imply a lack of communication in general, while the vice versa holds true.

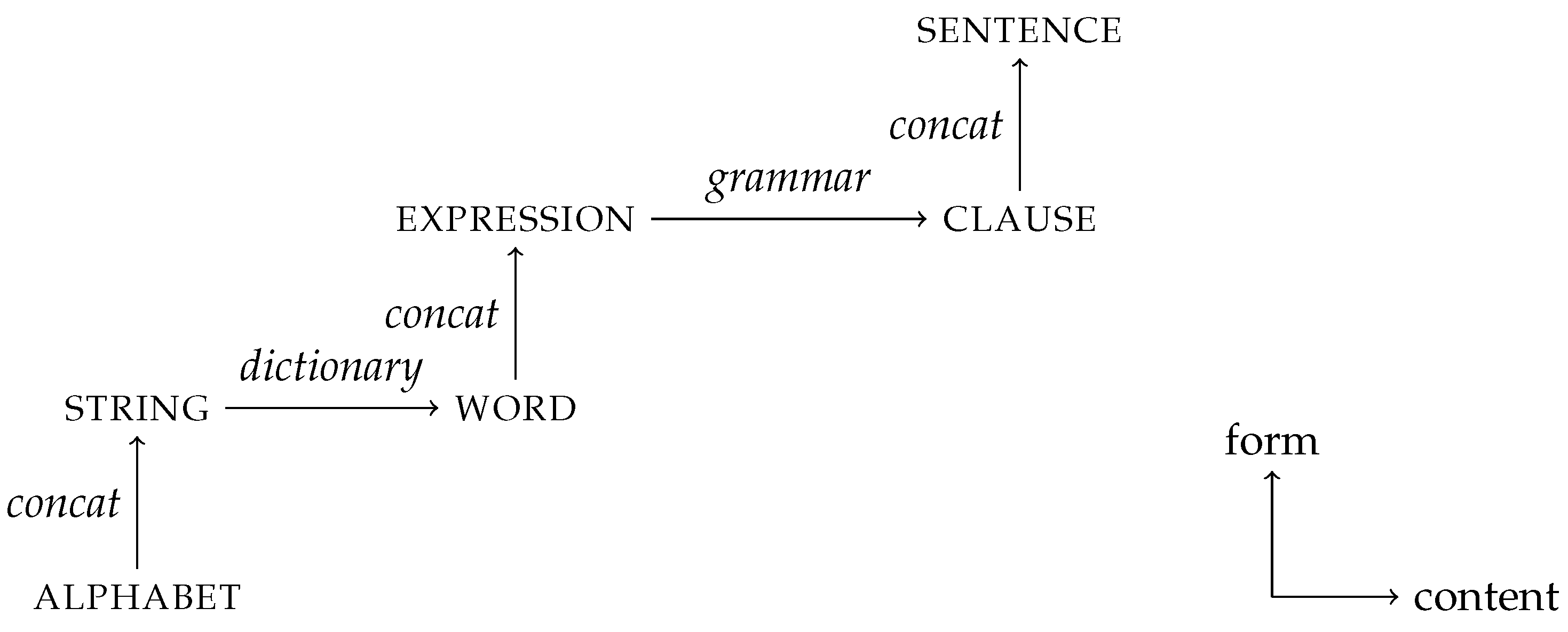

The structure that emerges from the definitions is depicted in

Figure 1, illustrating a content-form plane. Conventionally positioned at the origin of the axes, the alphabet, by definition, has no content and no form since symbols do not represent anything on their own and lack any substructure. The sole form operation conducted is concatenation, which, by acting on symbols, generates strings that acquire content through the constraint of the dictionary, distinguishing between words and non-words. Once again, concatenation produces expressions that, constrained by grammar, result in clauses. Concatenated clauses give rise to sentences, and they generate communication as an exchange of their informational content.

2.3. Knowledge

Defining knowledge is a very complex task, however, among the many definitions proposed, there are common and more widespread elements that we will synthesize. Knowledge can be innate, acquired by observation, thinking or thinking-plus-observing and through different sources

[IEP]. A widespread but not universally accepted definition states that knowledge is the justification of true beliefs (also known as JTB) [

20]. So knowledge is characterized by 3 features: it is a belief, it is true and it is justified. This concept is known as the tripartite theory of knowledge, which is often attributed to philosopher Edmund Gettier [

3]. The theory proposes that for a belief to qualify as knowledge, it must satisfy three conditions: belief, truth, and justification. At its core, knowledge involves holding a belief about something. This means that an individual must accept or affirm a proposition. In addition to being a belief, knowledge requires that the belief is true. A belief might be sincere and strongly held, but if it does not correspond to reality, it does not qualify as knowledge. The belief not only needs to be true but also justified. Justification refers to having good reasons or evidence that support the belief. In other words, there should be a rational basis for holding the belief. This criterion helps distinguish knowledge from mere lucky guesses.

Knowledge is something that is believed from the moment of acquiring knowledge for which such knowledge is believed to be true. Indeed, the most consensus feature about knowledge is the truth: one can believe in something false (one can have false information according to definition 8), yet one cannot have false knowledge (know something false) [

21]. Definition 8 of a sentence imposes no constraint on the truth of the sentence itself because the fact is not involved in the process of creating a sentence, nor in the overall communicative process. Ultimately, the main controversy is related to the third feature of knowledge, justification. In particular all those cases where justification is subjective or the true belief is not part of knowledge such as luck or superstition, scenarios that are not deterministically reproducible or based on some random pattern

[PLA][

20,

21,

22,

23]. The disagreement on the exact definition of knowledge develops in different strands. In particular, JTB is a necessary but not a sufficient condition. Then, there must be an unknown feature X (which leads to the definition of knowledge as JTB+X) where X is a condition or list of conditions logically independent from justification, truth, and belief [

22]. Or, justification feature is replaced with an other feature F such as reliability or other, leading to JTF. In any case, it is possible to relate condition F to condition J+X, where X is logically independent from J, T, and B, thus reducing the definition to the previous case, making FTB the more general definition. To distinguish from mere justification, we shall use the term

argumentation with the intention of representing a broader process.

Formally, we shall define knowledge as follows.

Definition 11.

Let a finite set of fact s and a language able to encode fact s into communicable sentence s. Then, knowledge is the argumentation of true beliefs by means of that set of fact s in the given language

.

From definition 11, knowledge is a believed and true fact (or finite set of facts) based on criteria of truth around which arguments, evidence, and demonstrations can be presented in a given language. Let a language and a finite set of facts, than finite knowledge is obtained by argumentation of true beliefs on given facts and can be incorporated into another set of facts to produce new knowledge

1. Hence, new knowledge proceeds by extension of the previous one. When it is not possible to extend the previous knowledge, then new knowledge stand alongside the previous one with no intersection

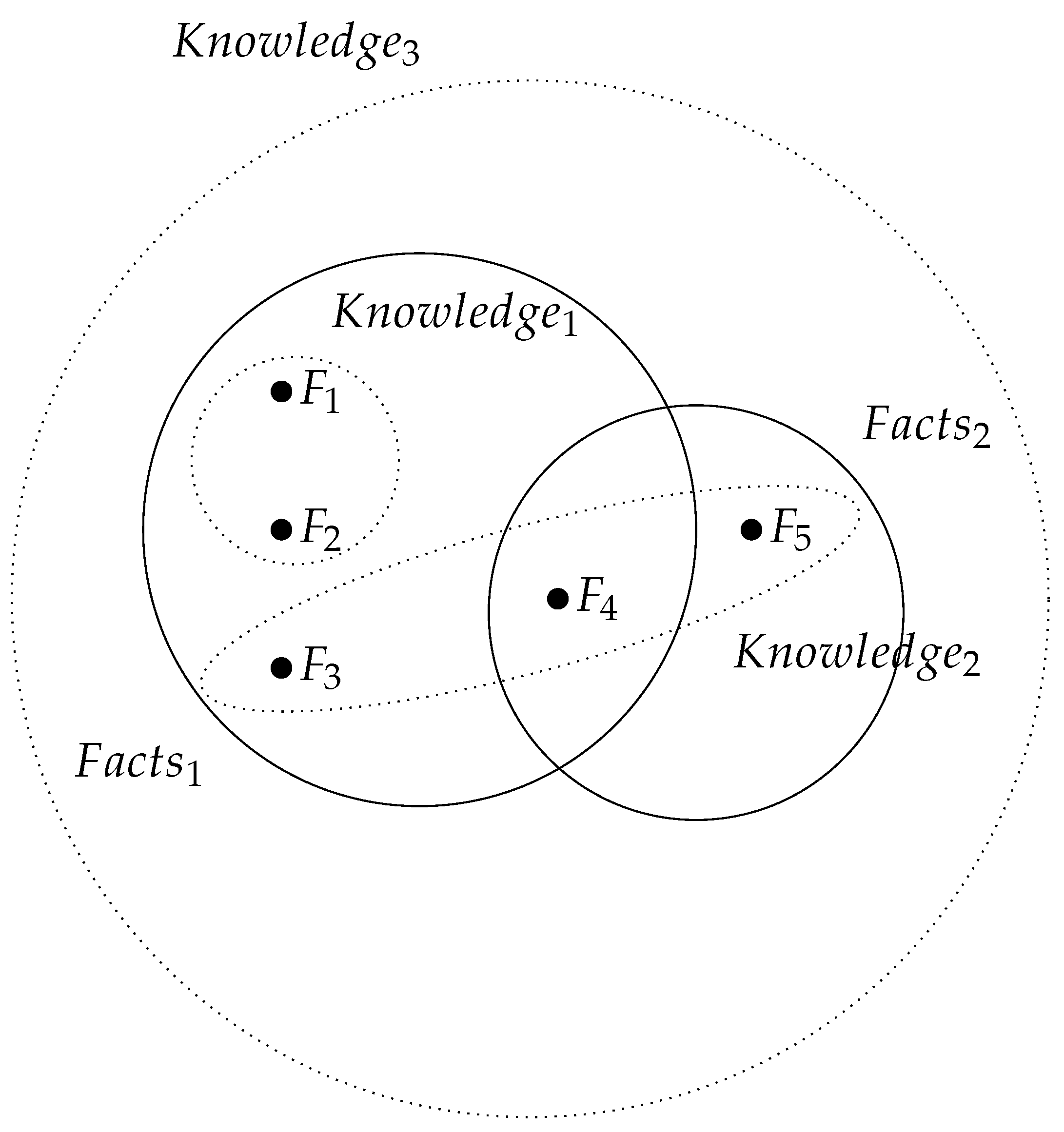

In

Figure 2 there are 2 sets of facts (solid line). The set

contains 4 facts

and the set

contains 2 facts

and

. Given a language, a finite set of true beliefs can be argued by using only facts

and

to produce knowledge

(dotted line). Adding fact

, new knowledge can be argued by

and

(or directly by

,

and

) and when

is also added, than is produced the whole knowledge that

can argued. Using

,

and

(belonging to differents sets to point out that facts do not need to belong to the same set) knowledge

is produced. Just as before, it is possible to extend

with

to produce

just as it is possible to produce

by facts

. This can be extended arbitrarily and applied to all configurations of sets of facts, languages and knowledge.

2.4. Research

[CAM] employs a definition in line with the convention of terms used. It defines research as “a detailed study of a subject, especially in order to discover (new) information or reach a (new) understanding”. The definition (rightly) makes no reference to the choice of criteria of truth because research is a process of study, exploration, discovery, much like communication. In fact, research can take various forms such as scientific, personal, spiritual, and can involve different phases. We need to take a step further and narrow down the definition in the scientific context to assert that scientific research is “a method of investigation in which a problem is first identified and observations, experiments, or other relevant data are then used to construct or test hypotheses that purport to solve it”[COL]. Let the set of all known facts through observation and measurement of nature, then the process of arguing true belief through these known facts is undoubtedly science. In our convention, science, is commonly defined as “the finite set of knowledge obtained through a methodical and rigorous research activity that organizes knowledge in such a way as to provide verifiable explanations and predictions about nature” [CAM][COL][BRI].

Definition 12.

Let a language and a finite set of information s. researchfor a given language and a finite set of information s, is the process of arguing (using that language) true beliefs by means of that set of fact s[MWE][CAM][PLA].

Hence, knowledge is produced through research. The process of arguing precedes knowledge itself, in the sense that the success of the argumentation marks the birth of new knowledge. In the event of a failure in the process, no knowledge has been produced.

Definition 13.

universe is a triad formed by a finite set of information s, a research and knowledge s.

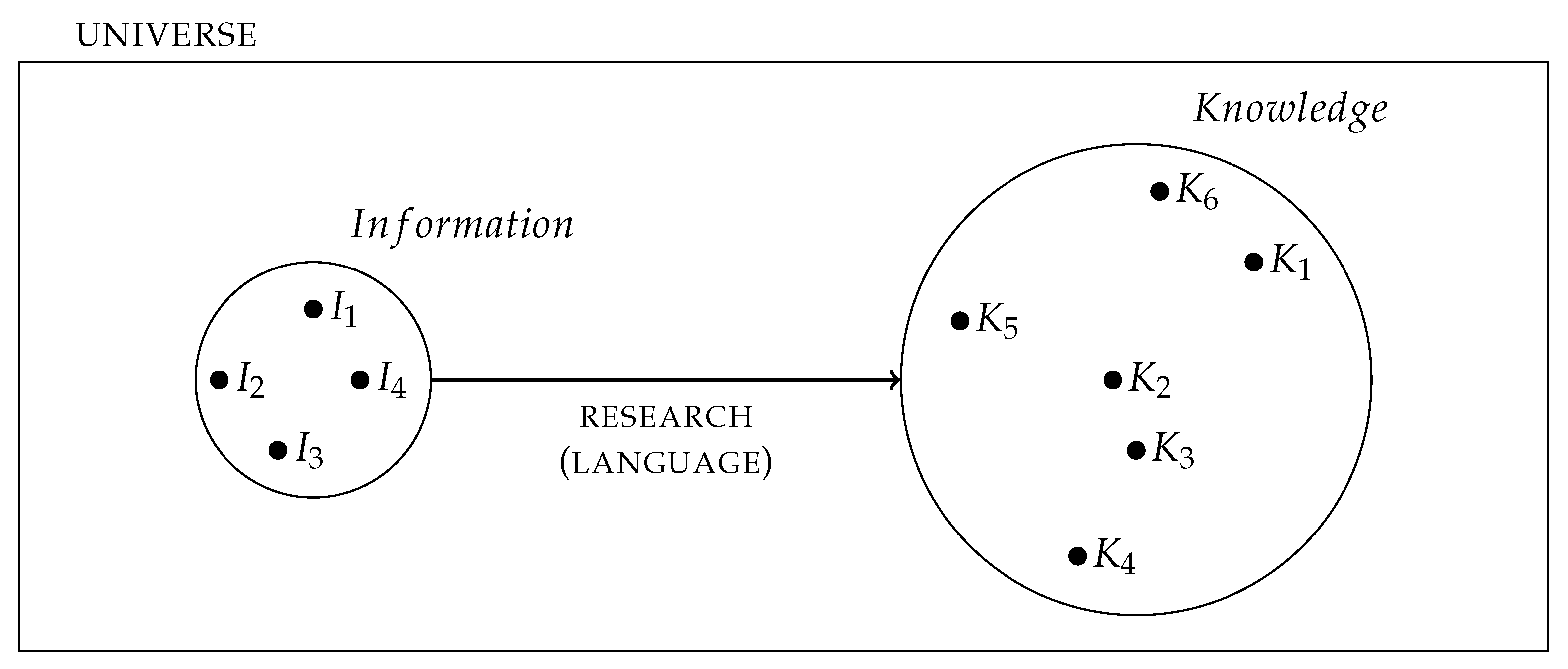

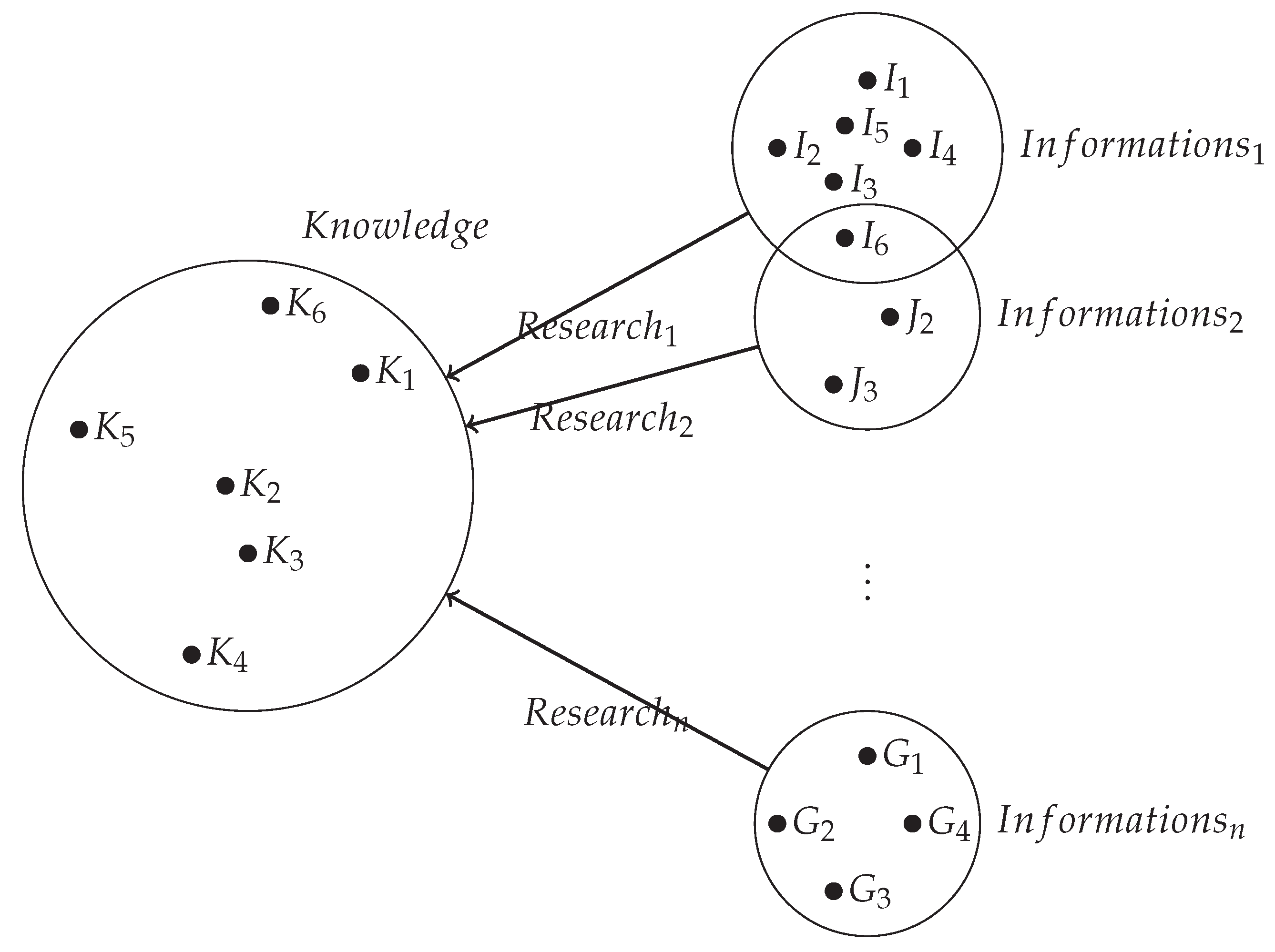

In

Figure 3 there is a finite set

of 4 informations

. From definition 12, research is the process that uses facts (encoded in informations by a language) to argue true beliefs and produce knowledge

in

set, according to definition 11. A finite set of informations, a research and a knowledge produced by that research, completely identify a universe. Equivalently, universe can also be defined by a quadruplet formed by a finite set of facts, a language, a research and the knowledge produced. Or, stating all the key ingredients, a finite set of facts, an alphabet, a grammar, a research and the knowledge produced. Once again, we want to point out that the definition of research is not limited to scientific research (it is a particular type of research, scientific in nature). It is a process (provided it is defined) during which the facts are argued through language in an attempt to concatenate them and raise them to knowledge. Given the finitude of information and the research process, producible knowledge is also finite. However, new knowledge is added to previous knowledge expanding the universe. It might be useful to provide a definition for the universe composed of the knowledge actually produced and the universe composed of all the knowledge that can be produced (having unlimited time to argue). The parallelism with cosmology is interesting: the

observable universe (universe composed of the knowledge actually produced) is defined as “the region of space that humans can actually or theoretically observe [...]. [...] Unlike the observable universe, the universe is possibly infinite and without spatial edges.”

[BRI]. We shall denote the observable universe as

o-universe.