Submitted:

26 June 2024

Posted:

27 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and Methods

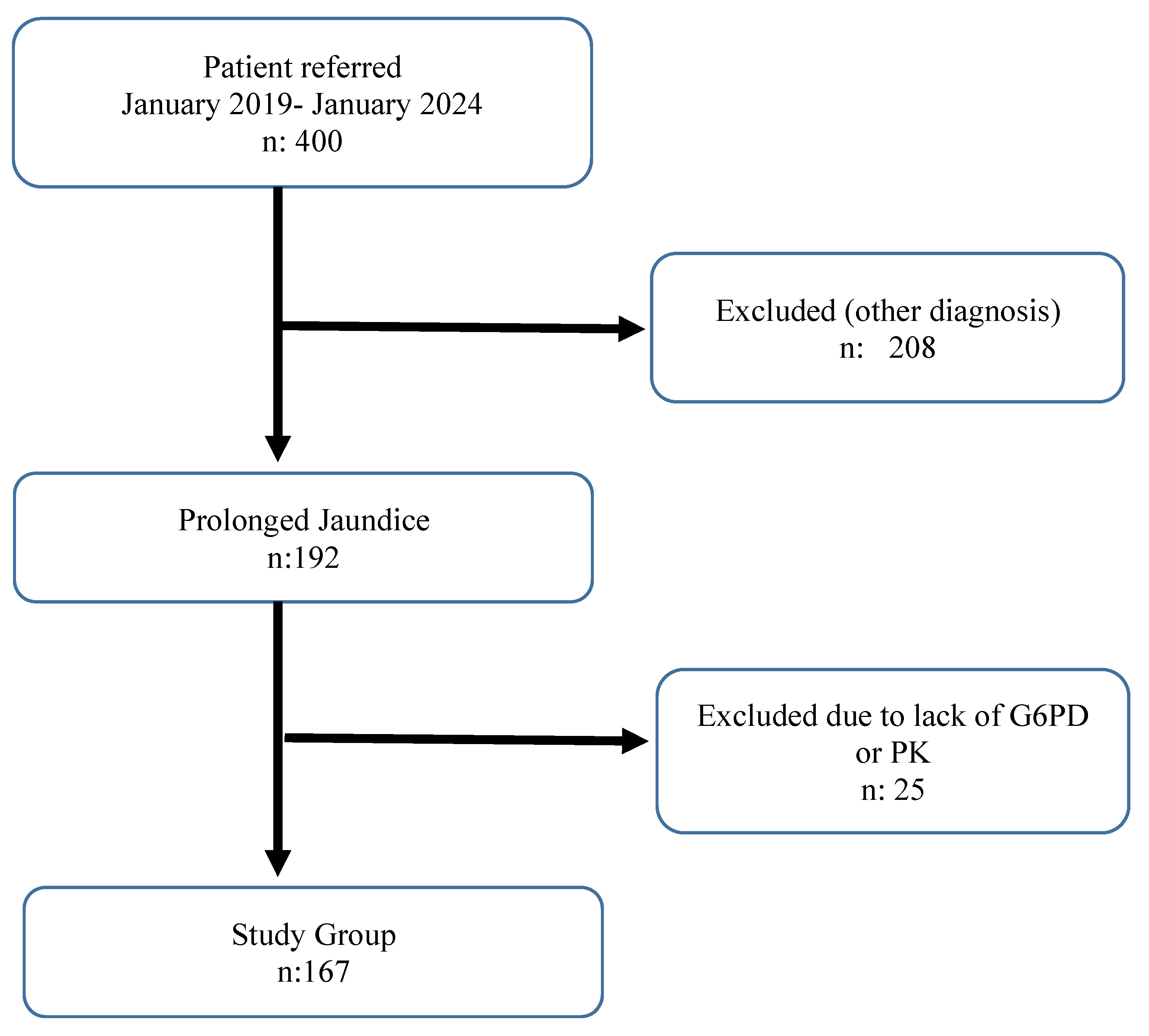

Study Design and Participants

Inclusion criteria

Exclusion Criteria

Laboratory Assessments

Measurement of Glucose 6 Phosphate Dehydrogenase (G6PD)

Measurement of Pyruvate Kinase (PK)

Statistical Analysis

Results

Discussion

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Behrman RE, Kliegman RM, Jenson HB. Jaundice and hyperbilirubinemia in the newborn. In: Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 16th ed. Saunders; 2021, part 11, chap 102:753-766.

- Giannattasio A, Ranucci G, Raimondi F. Prolonged neonatal jaundice. Ital J Pediatr. 2015;41(Suppl 2):A36. [CrossRef]

- Kaplan M, Merlop P, Regev R. Israel guidelines for the mamagement of neonatal hyperbilirubinemia and prevention of kernicterus. J Perinatol 2008;28:389-97. [CrossRef]

- Weng YH, Cheng SW, Yang CY, Chiu YW. Risk assessment of prolonged jaundice in infants at one month of age: A prospective cohort study. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):14824. [CrossRef]

- Kassahun W, Tunta A, Abera A, Shiferaw M. Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency among neonates with jaundice in Africa; systematic review and meta-analysis. Heliyon. 2023;9(7):e18437. [CrossRef]

- Zakerihamidi M, Moradi A, Boskabadi H. Comparison of severity and prognosis of jaundice due to Rh incompatibility and G6PD deficiency. Transfus Apher Sci. 2023;62(4):103714. [CrossRef]

- Abdel Fattah M, Abdel Ghany E, Adel A, Mosallam D, Kamal S. Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase and red cell pyruvate kinase deficiency in neonatal jaundice cases in egypt. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2010;27(4):262-271. [CrossRef]

- Grace RF, Barcellini W. Management of pyruvate kinase deficiency in children and adults. Blood. 2020;136(11):1241-1249. [CrossRef]

- Cunningham AD, Hwang S, Mochly-Rosen D. Glucose-6- Phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency and the need for a novel treatment to prevent kernicterus. Clin Perinatol 2016;43:341-54. [CrossRef]

- Kemper AR, Newman TB, Slaughter JL, et al. Clinical Practice Guideline Revision: Management of Hyperbilirubinemia in the Newborn Infant 35 or More Weeks of Gestation. Pediatrics. 2022;150(3): e2022058859. [CrossRef]

- Okuyan O, Elgormus Y, Sayili U, Dumur S, Isık OE, Uzun H. The Effect of Virus-Specific Vaccination on Laboratory Infection Markers of Children with Acute Rotavirus-Associated Acute Gastroenteritis. Vaccines (Basel). 2023;11(3):580. [CrossRef]

- Ullah S, Rahman K, Hedayati M. Hyperbilirubinemia in Neonates: Types, Causes, Clinical Examinations, Preventive Measures and Treatments: A Narrative Review Article. Iran J Public Health 2016.45(5): 558- 568.

- Hall V, Avulakunta ID. Hemolytic diseases of the newborn. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2023. Updated November 22, 2022. Accessed August 20, 2023.

- Rodie MD, Barclay A, Harry C, et al. NICE recommendations for the formal assessment of babies with prolonged jaundice: too much for well infants? Arch Dis Child. 2011;96(1):112-3. [CrossRef]

- Bhutani VK, Maisels MJ, Stark AR, Buonocore G: Expert Committee for Severe Neonatal Hyperbilirubinemia, Eurepean Society for Pediatric Research and American Academy of Pediatrics. Management of Jaundice and Prevention of Severe Hyperbilirubinemia in Infants ≥35 Weeks Gestation. Neonatology 2008; 94: 63-7. [CrossRef]

- Satrom KM, Farouk ZL, Slusher TM. Management challenges in the treatment of severe hyperbilirubinemia in low- and middle-income countries: Encouraging advancements, remaining gaps, and future opportunities [published correction appears in Front Pediatr. 2023 May 02;11:1181023]. Front Pediatr. 2023;11:1001141. [CrossRef]

- Gao C, Guo Y, Huang M, He J, Qiu X. Breast Milk Constituents and the Development of Breast Milk Jaundice in Neonates: A Systematic Review. Nutrients. 2023;15(10):2261. [CrossRef]

- Gartner LM. Breastfeeding and jaundice. J Perinatol 2001; 21: 25-9. [CrossRef]

- Arias IM, Gartner LM, Seifter S, Furman M. Prolonged neonatal unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia associated with breast feeding and a steroid, pregnane-3 (alpha), 20 (beta)-diol in maternal milk that inhibits glucuronide formation in vitro. J Clin Invest 1964;43: 2037-47. [CrossRef]

- Buiter HD, Dijkstra SS, Oude Elferink RF, Bijster P, Woltil HA, Verkade HJ. Neonatal jaundice and stool production in breast-or formula-fed term infants. Eur J Pediatr 2008; 167: 501-7. [CrossRef]

- Eghbalian F, Raeisi R, Faradmal J, Asgharzadeh A. The Effect of Clofibrate and Phototherapy on Prolonged Jaundice due to Breast Milk in Full-Term Neonates. Clin Med Insights Pediatr. 2023; 17:11795565231177987. [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir A, Kurtoglu S, Halis H, Bastug O. An evaluation of ursodeoxycholic acid treatment in prolonged unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia due to breast milk. Niger J Clin Pract. 2023;26(9):1226-1233. [CrossRef]

- Christensen RD, Eggert LD, Baer VL, et al. Pyruvate kinase deficiency as a cause of extreme hyperbilirubinemia in neonates from a polygamist community. J Perinatol 2010;30:233-6. [CrossRef]

- Aygün E, Yilmaz Semerci S. Prolonged Jaundice in Newborn [Internet]. Topics on Critical Issues in Neonatal Care. IntechOpen; 2022.

- McMahon JR, Stevenson DK, Oski FA. Physiologic Jaundice. In: Taeusch HW,Ballard RA, eds. Avery’s Disease of the Newborn 7th ed. Philadelphia, WBSaunders, 1998, pp 1003-1007.

- Yang YK, Lin CF, Lin F, et al. Etiology analysis and G6PD deficiency for term infants with jaundice in Yangjiang of western Guangdong. Front Pediatr. 2023; 11:1201940. [CrossRef]

- Kurt A, Tosun MS, Altuntaş N, Erol S. Effect of Phototherapy on Peripheral Blood Cells in Hyperbilirubinemic Newborns. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2020;30(5):547-549. [CrossRef]

- Karabulut B, Alatas SO. Diagnostic Value of Neutrophil to Lymphocyte Ratio and Mean Platelet Volume on Early Onset Neonatal Sepsis on Term Neonate. J Pediatr Intensive Care. 2021;10(2):143-147. [CrossRef]

- Li T, Dong G, Zhang M, et al. Association of Neutrophil-Lymphocyte Ratio and the Presence of Neonatal Sepsis. J Immunol Res. 2020; 2020:7650713. [CrossRef]

- Cakir U, Tayman C, Tugcu AU, Yildiz D. Role of Systemic Inflammatory Indices in the Prediction of Moderate to Severe Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia in Preterm Infants. Arch Bronconeumol. 2023;59(4):216-222. [CrossRef]

- Zhang S, Luan X, Zhang W, Jin Z. Platelet-to-Lymphocyte and Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio as Predictive Biomarkers for Early-onset Neonatal Sepsis. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2021;31(7):821-824. [CrossRef]

- Pan R, Ren Y, Li Q, et al. Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratios in blood to distinguish children with asthma exacerbation from healthy subjects. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2023; 37:3946320221149849. [CrossRef]

- Chang LS, Lin YJ, Yan JH, Guo MM, Lo MH, Kuo HC. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and scoring system for predicting coronary artery lesions of Kawasaki disease. BMC Pediatr. 2020;20(1):398. [CrossRef]

- Cine HS, Uysal E, Gurbuz MS. Is neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio a prognostic marker for traumatic brain injury in the pediatric population? Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2023;27(20):9729-9737. [CrossRef]

| n mean±std |

% Median(Q1-Q3) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 106 | 63.5% |

| Female | 61 | 36.5% |

| Age (days) | 31±6 | 30(28-33) |

| Direct Cooms test | ||

| Negative | 167 | 100.0% |

| Urine Culture | ||

| No reproduction | 167 | 100.0% |

| Abdominal USG | ||

| Normal | 167 | 100.0% |

| Breast feeding | ||

| Yes | 167 | 100.0% |

| Formula | ||

| No | 155 | 92.8% |

| Yes | 12 | 7.2% |

| ABO incompatibility | ||

| No | 157 | 94.0% |

| Yes | 10 | 6.0% |

| Rh incompatibility | ||

| No | 152 | 91.0% |

| Yes | 15 | 9.0% |

| Reductant substance | ||

| No | 140 | 83.8% |

| Yes | 27 | 16.2% |

| Hospitalization | ||

| No | 160 | 95.8% |

| Yes | 7 | 4.2% |

| Length of stay | 2±2 | 1(1-1) |

| Day of onset of jaundice | 2±0 | 2(1-2) |

| Time to fall below TB=8 (days) | 78±6 | 80 (80-80) |

| Gestational week | 37±1 | 37(36-38) |

| Mean±std | Median (Q1-Q3) | Reference values | |

|---|---|---|---|

| WBC (103cells/µL) | 9687±2580 | 9110 (7910-11100) | 9.4-38 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 13.22±2.27 | 13.1(11.6-14.8) | 13.4-19.8 |

| Hct (%) | 37.49±6.7 | 37.1(32.5-41.4) | 41-65 |

| Reticulocyte (%) | 2.10 ± 0.80 | 1.93(0.50-2.12) | 0.5%–2.5% |

| PLT (103/uL) | 344±95 | 328(277-400) | 150-400 |

| LYMPH (103cells/µL) | 6.14±1.57 | 5.98(5.01-6.84) | 2.8-9.1 |

| NEU (103cells/µL) | 2.04±2.45 | 1.69(1.2-2.22) | 1.8-5.4 |

| NLR | 0.38±0.91 | 0.3(0.21-0.37) | |

| PLR | 59.28±22.28 | 55.38(43.05-70.76) | |

| SII | 114.88±112.5 | 95.73(64.61-125.96) | |

| MONO (103cells/µL) | 1.31±4.39 | 0.94(0.7-1.27) | 0-1.7 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L) | 2.28±1.42 | 2.3(1.1-3.5) | >5 |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 139.26±2.99 | 139(137-141) | 136-145 |

| Potassium (mmol/L) | 4.53±0.58 | 4.6(4-5) | 3.5-5.1 |

| Urea (mg/dL) | 8.3±5.14 | 6.8(4.6-12) | 5-20 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.45±0.34 | 0.42(0.35-0.51) | Male: 0.74-1.35 Female: 0.59-1.04 |

| Total biluribin (mg/ dL) | 12.54±2.67 | 12.26(10.86-14.21) | 0.2-16.6 |

| Direct biluribin (mg/ dL) | 0.60±0.45 | 0.54 (0.48-0.62) | 0.3-0.7 |

| G6PD (U/g Hb) | 21.95±6.19 | 21.3(17.11-25.63) | 7.00-16.50 |

| Pyruvate kinase (mU/109 RBC/mL) | 284.07±91.56 | 278(198-356) | 111-406 |

| fT4 (ng/dL) | 1.13±0.29 | 1.09(1.01-1.19) | 1.05-3.21 |

| TSH (mU/ L) | 3.37±1.88 | 3.14(2.2-4.25) | 0.73-4.77 |

| AST (U/L) | 39.11±12.19 | 38(31-47) | 25-75 |

| ALT (U/L) | 23.80±8.93 | 24(17-36) | 7-56 |

| GGT (U/L) | 110.50±31.04 | 125(88-136) | 12-147 |

| ALP (U/L) | 250.67±40.34 | 287 (248-315) | Male: 75-316 Female: 48-406 |

| Protein (g/ dL) | 5.53±0.59 | 5.6(5.2-5.89) | 6.0-8.3 |

| Albumin (g/ dL) | 3.63±0.56 | 3.6(3.24-4.1) | 1.90 to 4.90 |

| NLR | p | PLR | p | SII | p | G6PD | p | PK | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||||||||

| Male | 0.3(0.21-0.38) | 0.286 | 56.61(43.05-73.12) | 0.854 | 97.7(63.14-132.09) | 0.379 | 21.22(16.78-25) | 0.288 | 265(188-354) | 0.071 |

| Female | 0.28(0.18-0.35) | 53.58(44.15-70.24) | 90.92(65.69-114.08) | 21.82(18.23-27.56) | 302(231-358) | |||||

| Hospitalization | ||||||||||

| No | 0.3(0.21-0.37) | 0.701 | 56.61(43.33-70.69) | 0.539 | 95.81(65.67-123.94) | 0.917 | 21.27(17.16-25.58) | 0.701 | 279.5(196.5-356) | 0.358 |

| Yes | 0.21(0.17-0.74) | 50.11(40.65-78.44) | 76.17(45.68-201.94) | 25.45(11.57-28.39) | 245(212-345) | |||||

| Formula | ||||||||||

| No | 0.3(0.2-0.38) | 0.862 | 55.35(43.05-70.63) | 0.406 | 94.69(64.61-125.96) | 0.488 | 21.23(17.02-25.63) | 0.865 | 280(204-356) | 0.095 |

| Yes | 0.26(0.24-0.33) | 61.7(51.71-73.23) | 108.31(86.5-121.12) | 22.68(19.44-24.49) | 243(188-280.5) | |||||

| ABO incompatibility | ||||||||||

| No | 0.3(0.21-0.37) | 0.254 | 56.7(43.81-70.76) | 0.287 | 95.88(67.35-125.96) | 0.082 | 21.2(17.11-25.55) | 0.257 | 278(195-356) | 0.744 |

| Yes | 0.25(0.15-0.32) | 48.02(40.03-62.84) | 67.65(47.27-111.85) | 23.33(20.44-29.72) | 278(235-354) | |||||

| Rh incompatibility | ||||||||||

| No | 0.3(0.21-0.37) | 0.991 | 55.37(43.05-70.58) | 0.455 | 95.34(65.13-125.96) | 0.878 | 21.25(17.16-25.63) | 0.989 | 274(201-354) | 0.437 |

| Yes | 0.28(0.21-0.44) | 58.74(44.53-99.4) | 99.17(64.61-106.78) | 21.82(14.56-25.55) | 312(189-400) | |||||

| Reductant substance | ||||||||||

| No | 0.3(0.21-0.36) | 0.931 | 55.37(42.88-70.69) | 0.788 | 94.82(63.87-124.67) | 0.512 | 21.22(17.24-25.63) | 0.934 | 272(189-355) | 0.328 |

| Yes | 0.29(0.23-0.39) | 56.7(44.56-75.42) | 95.88(71.54-131.06) | 21.78(16.74-24.65) | 303(228-356) | |||||

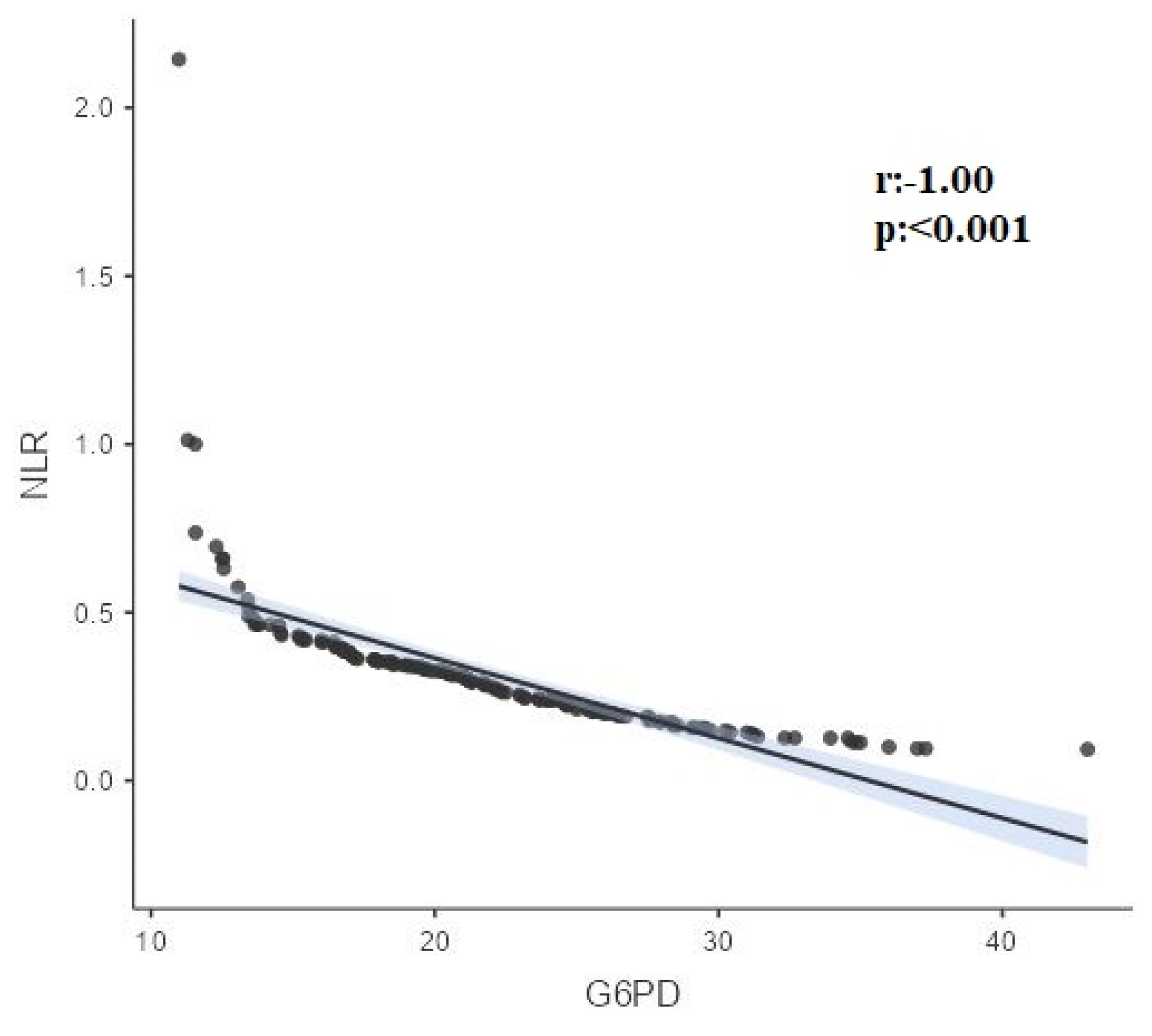

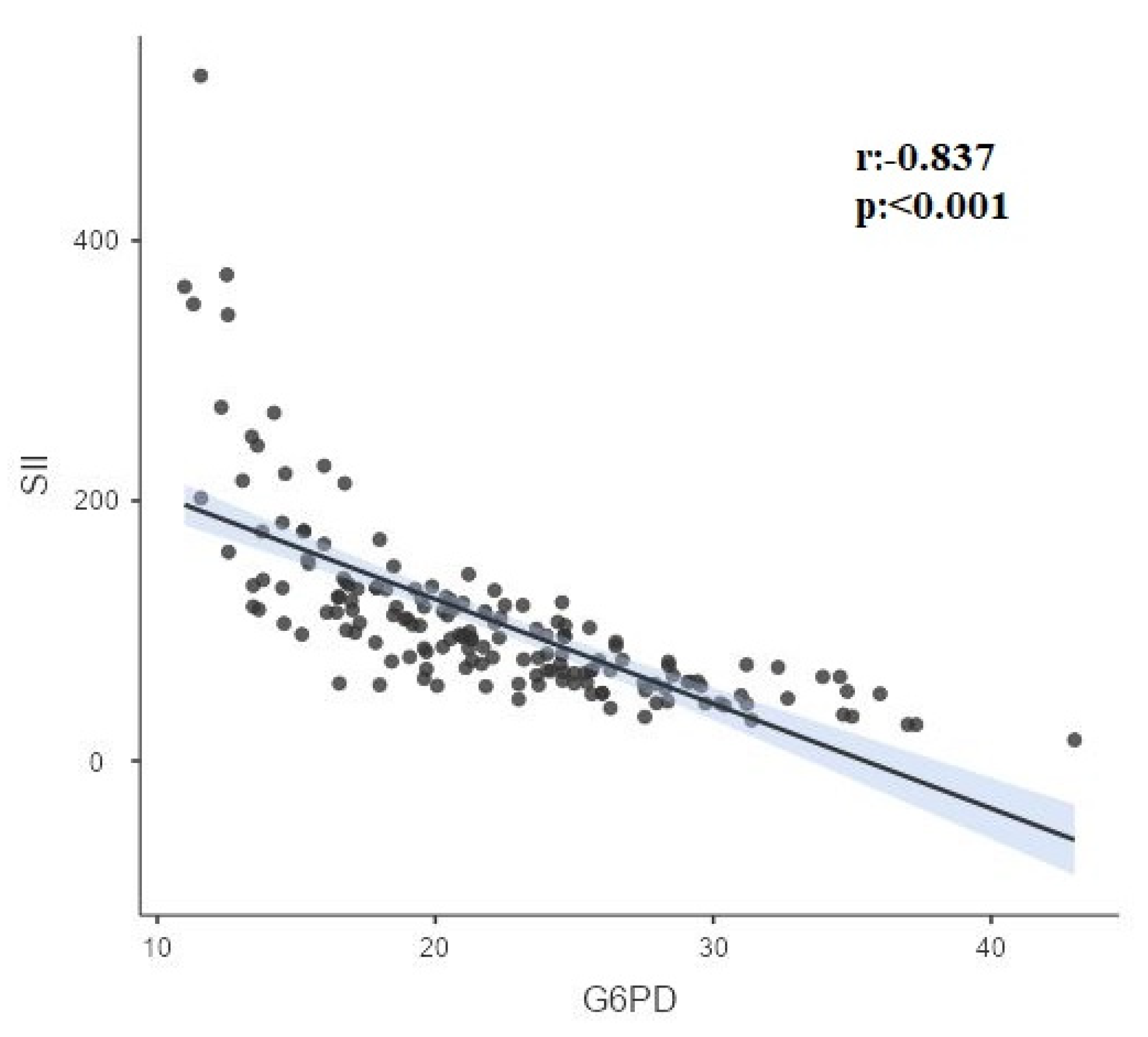

| Variables | r-p | PK | NLR | PLR | SII | Age | Hct |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G6-PD | r | 0.00 | -1.000 | -0.12 | -0.837 | 0.296 | -0.285 |

| p | 0.960 | <0.001 | 0.132 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| PK | r | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.05 | -0.04 | -0.04 | |

| p | 0.968 | 0.501 | 0.510 | 0.617 | 0.613 | ||

| NLR | r | 0.12 | 0.837 | -0.295 | 0.285 | ||

| p | 0.132 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| PLR | r | 0.472 | 0.07 | -0.290 | |||

| p | <0.001 | 0.340 | <0.001 | ||||

| SII | r | -0.227 | 0.191 | ||||

| p | 0.003 | 0.014 | |||||

| Age | r | -0.286 | |||||

| p | <0.001 |

| NLR | SII | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| G6PD | Correlation coefficient (r) | -0.212 | -0.470 |

| p value | 0.006 | <0.001 |

| Model | Unstandardized Coefficients (B) | 95,0% Confidence Interval for B | P value | R Square |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | 0.198 | |||

| (Constant) | 23.786 | 16.210/31.363 | <0.001 | |

| Age (days) | 0.199 | 0.061/0.338 | 0.005 | |

| HCT | -0.199 | -0.340/-0.059 | 0.006 | |

| NLR | -1.407 | -2.411/-0.402 | 0.006 | |

| Model 2 | 0.346 | |||

| (Constant) | 24.339 | 17.565/31.113 | <0.001 | |

| Age (days) | 0.152 | 0.026/0.278 | 0.018 | |

| HCT | -0.110 | -0.238/0.018 | 0.091 | |

| SII(100 unit) | -2.581 | -3.331/-1.831 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).