2.1. Modelling a Terrestrial Acidification Hypothesis

The ocean surface is considered as having an active mixing zone varying from about 25 metres depth near the equator to 100 metres or more at high latitudes, with little or no penetration deeper except on much longer time scales [

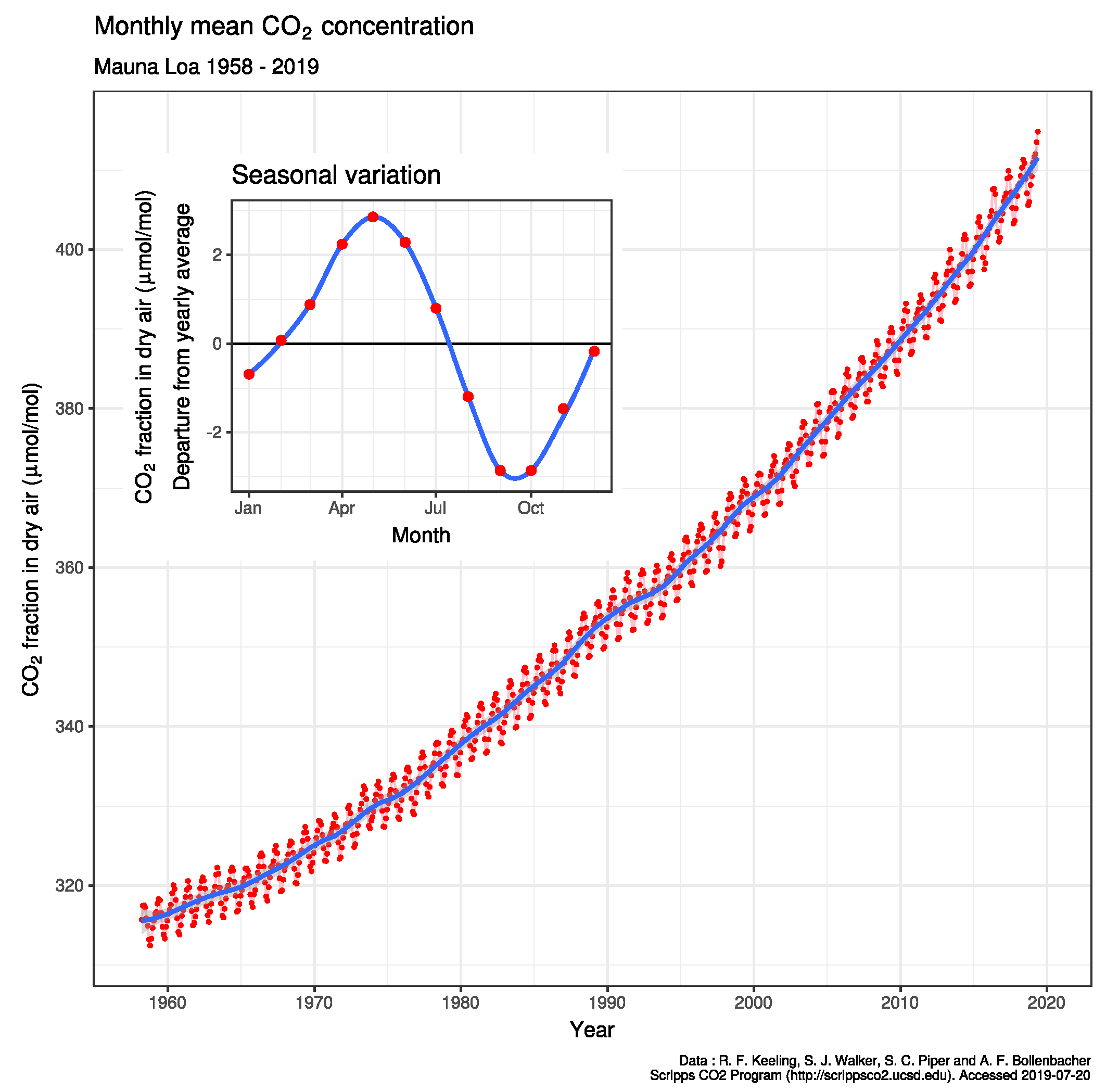

3]. This assumption of a separate well mixed compartment from the bulk of the deeper ocean is very useful for short term modelling the increasing level of

pCO

2 in the atmosphere. At least in the short term of 12 months, composition globally is approximately homogeneous, so that we were able to model the influence of seasonal variation in temperature on the

pCO

2 in the atmosphere.

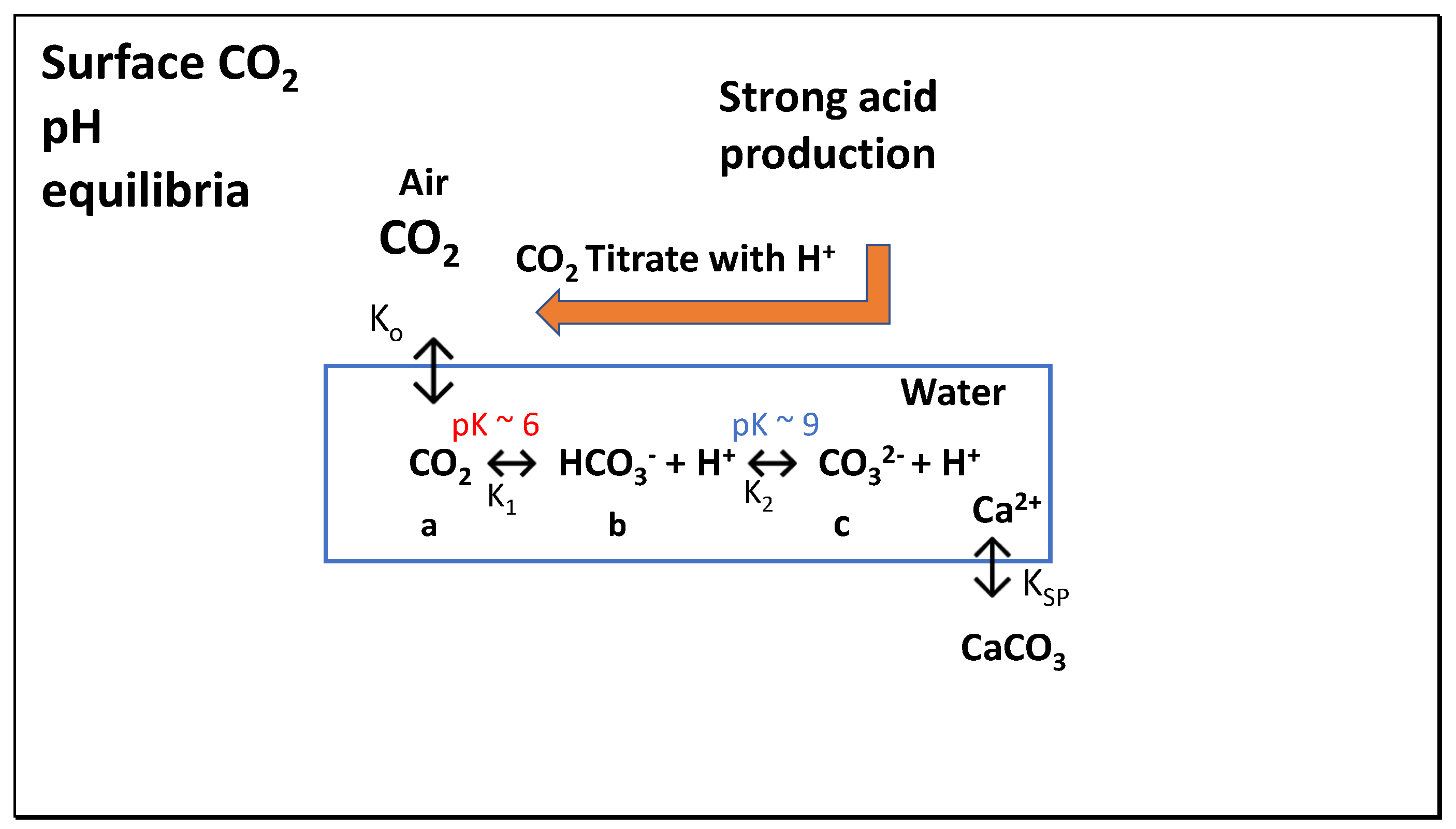

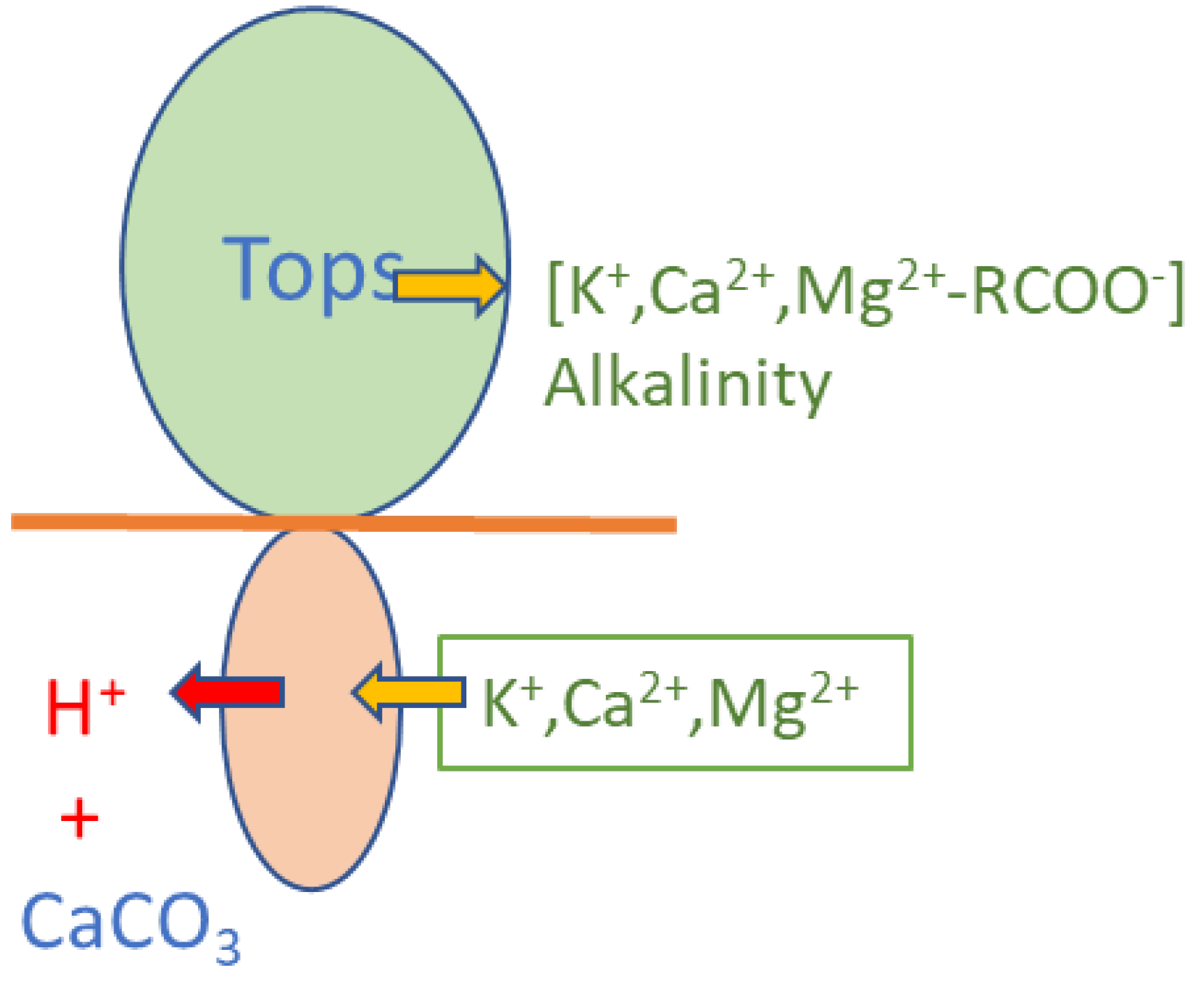

On land, no such general assumption can be made regarding dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) species, given the high local variability of pH in soil and associated water. Only heterogeneous equilibria are possible between the DIC species shown in

Figure 2 and the CO

2 in the atmosphere. Nevertheless, as long as the pH value falls between 6.5 and 9.0 bicarbonate (HCO

3-) will be the predominant species and irresistible thermodynamic action as a function of temperature and pH value will ensure that a tendency to equilibrium will exist, despite this being less easily achieved in the ocean. In all such cases, the generation of strong acid species will result in CO

2 evolution and below pH 8, this will be almost equal to the equivalents of acid generated. Rather than attempt to model such a heterogeneous systems which would be possible, we preferred to use conditions in seawater to establish relationships between additions of strong acid and weak acid like carbonic. While salt concentration will affect the activity of species such as carbonate and calcium ions, we are able to calculate such effects approximately using available algorithms described in this section.

Our hypothesis regarding the influence of falling surface pH on the increasing trend of atmospheric

pCO

2 will be tested with our model Titrate (

Figure 2), similar in programming structure to the Thermal model [

1]. School laboratory chemistry usually includes dropwise titrations from burettes of one chemical solution with another; an indicator shows colour changes of pH value when the solution is near neutrality in hydrogen ion concentration. Equations (1) and (2) are possible for absorption of strong acid, with only (1) directly yielding emission of CO

2. The relative concentration of carbonate and bicarbonate determines the statistical stoichiometry for the reaction. At pH 8.2 in sea water, this ratio is about 1 in 8 and the destruction of alkalinity at each pH by each equivalent of hydrogen ions will be partitioned in this ratio, taking into account the double alkalinity of carbonate. To a small extent given its concentration of only 0.5 mM, borate in sea water will also absorb acidity without CO

2 emission, having most effect at its pK value of 8.7, but less in seawater near 8.2.

By comparison with water on land, seawater is relatively strongly buffered in pH value with more than 2 mM bicarbonate as DIC. As a result, pH values can change more rapidly with processes like photosynthesis in freshwater. Below pH 7.5 in seawater and even at the lower acidity of pH 8.0 in freshwater as shown later, nearly all destruction of alkalinity involves stoichiometric conversion of bicarbonate to an equivalent of weakly acid CO

2. To the extent that the concentration and fugacity of [CO

2] generated exceeds that allowed by the Henry coefficient at the water temperature, CO

2 will be transferred to the atmosphere at a rate dictated by the ratio of fugacities in water and air, a function of temperature as explained earlier [

1]. It is likely that heterogeneous equilibria on land will be achieved on an annual timescale, not requiring longer times to establish clear trends between acidification of atmospheric

pCO

2, certainly not many years. We will examine how this thermodynamic principle affects the fate of emissions of CO

2 from fossil fuels in this article.

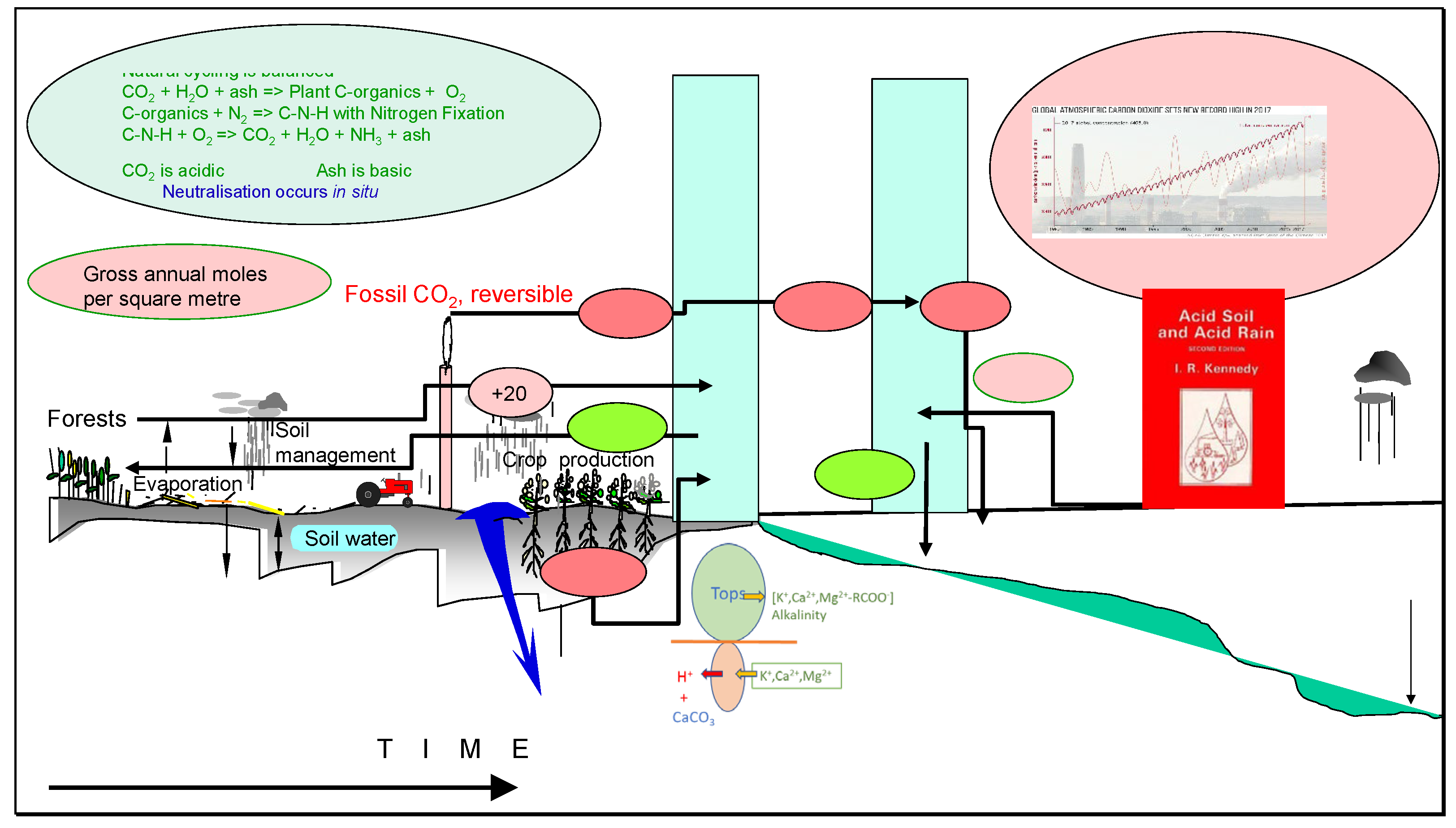

Thermodynamic interaction of atmospheric CO

2 will occur with the highly heterogenous land surface to an extent governed by the variable hydration of soil as well as by reaction with DIC in lakes and river systems. Some absorption of CO

2 in highly alkaline waters will also occur erratically though continuously. For a hypothesis to be credible as shown in

Figure 2, the possible rates of strong acid production must have a rational quantitative relationship with the observed increases of CO

2 in the atmosphere. In a closed system, each aliquot of acid will eventually generate an exact

pCO

2 depending on concentrations of DIC and temperature. In an open system like the global environment, this is true within the constraints of variable conditions of temperature in water and air and other factors, with the actual

pCO

2 in air usually in disequilibrium with that in water, but with transfer rates between the liquid and gaseous phases dependent on the extent of this disequilibrium condition. We will make estimates of this condition and predict time constants for these processes in this article.

For modelling, the strategy is to demonstrate the capability of the Titrate model to estimate equilibrium values, taking into account alkalinity (A), total dissolved inorganic carbon species (C), and pH values in surface waters and

pCO

2 values in air at equilibrium. As in all environmental systems, equilibrium is rarely achieved, subject to macroscopic variations in conditions such as temperature, density or pressure and process rates of chemical reaction. On different time scales systems will evolve showing a natural tendency to increase their action and entropy in their approach to equilibrium [

6], including for gases in the troposphere. Using the Titrate model, rates of acidification in seawater, soil water or in lakes and rivers on land can be examined, to gauge the possible effects of adding strong acids on the

pCO

2 (ppmv) in air. Finally, these possibilities will be tested for their global significance, using available data to predict risk and the validity of the IPCC models for control of global

pCO

2. Readers are advised to consult the previous article [

1] for a more comprehensive account of the background inorganic chemistry and thermodynamics regarding CO

2. Most of the chemical processes of inorganic nitrogen and sulphur were considered in the earlier treatise entitled

Acid Soil and Acid Rain [

4], although the magnitude of CO

2 emissions was not then of interest with focus on aluminium ion toxicity, released below pH 5.

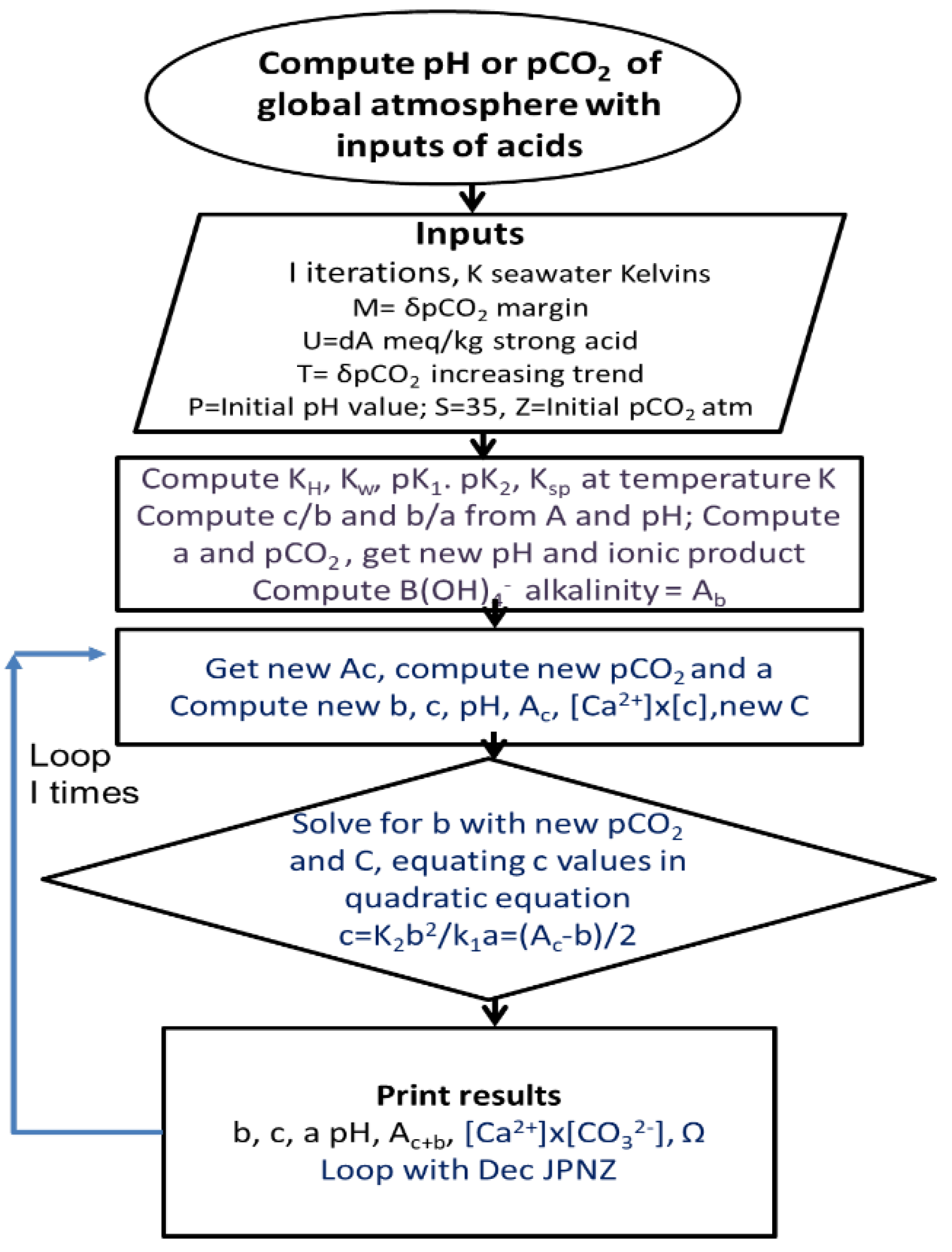

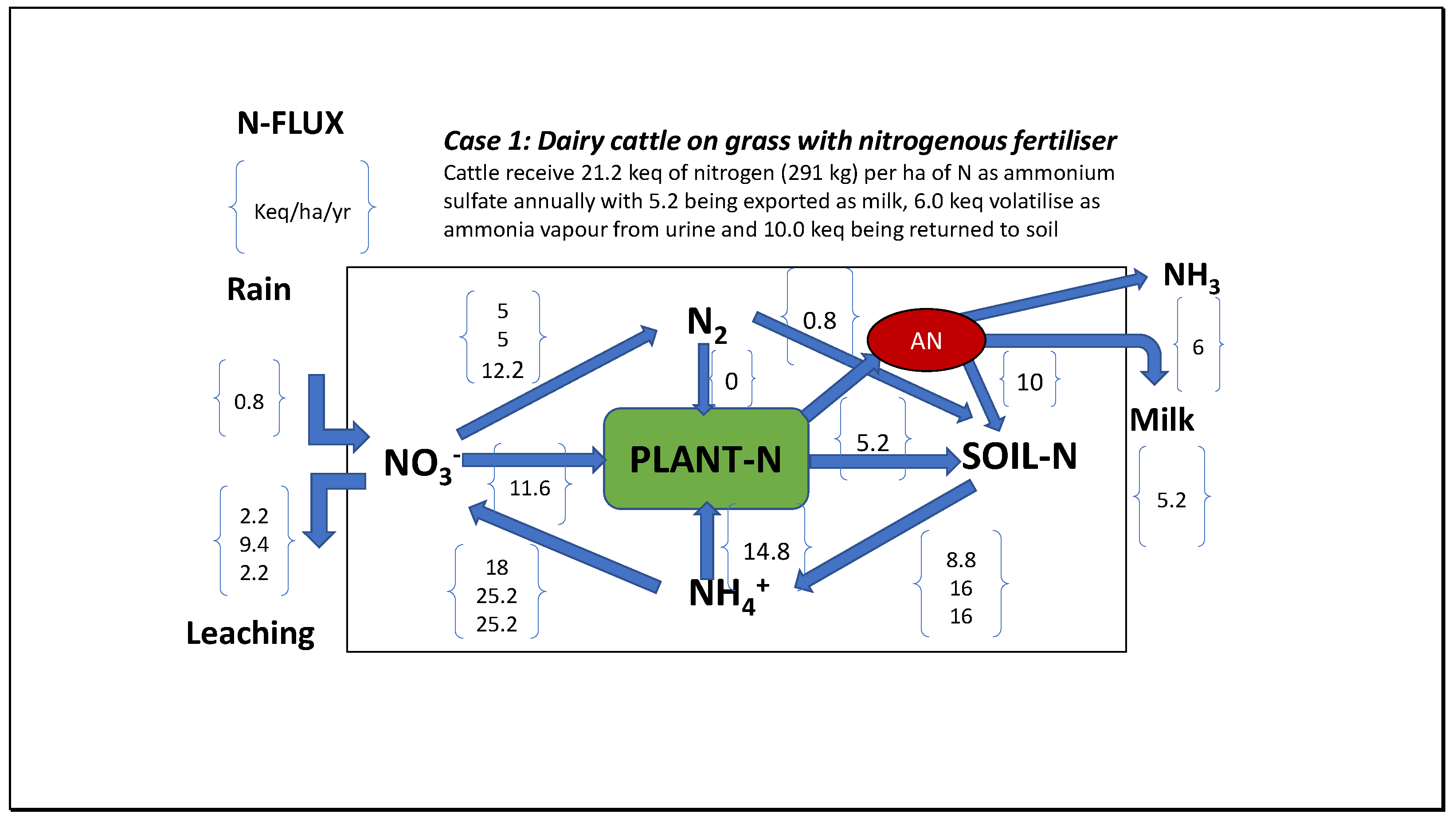

For modelling processes, robust algorithms [

1] previously established by oceanographic authorities performing research on seawater were employed (

Figure 3). These include those described by Dickson and Millero [

10] in documents of the United States Department of Energy [

11,

12,

13,

14], particularly the algorithms used to calculate fluctuations in key equilibrium constants with temperature or salt concentration given by Emerson and Hedges [

14]. There are at least 10 computing packages available for calculating key inorganic properties of DIC in seawater [

15] based on the principle of setting input pairs of variables to particular values and then calculating all other values of interest. These models all give similar results with minor exceptions, as modifications of the methods recommended by Dickson and Millero [

10], employed mainly for accuracy in data collection and recording.

A more flexible approach was adopted here in the various programs called collectively Titrate (

Figure 3). When executed this program first estimates as functions of temperature and salt concentration all key constants (Henry coefficient K

o, the equilibrium of bicarbonate with dissolved CO

2, K

1; the equilibrium of carbonate with bicarbonate, K

2; the solubility product for calcite, K

sp) occurring in key reactions. Then levels are estimated (mmoles per kg of water) of inorganic intermediates ([CO

2]=a; [HCO

3-] = b; [CO

32-]=c) under the prevailing conditions of temperature and pH value as controlled by alkalinity (A) or atmospheric

pCO

2. Where reiterations of acid and CO

2 are included in programs, a unique quadratic solution is used to obtain new values of bicarbonate using simultaneous Equations. This solution was given in more detail in an earlier study [

1] on the seasonal oscillations in atmospheric

pCO

2 caused by variations in seawater temperature..

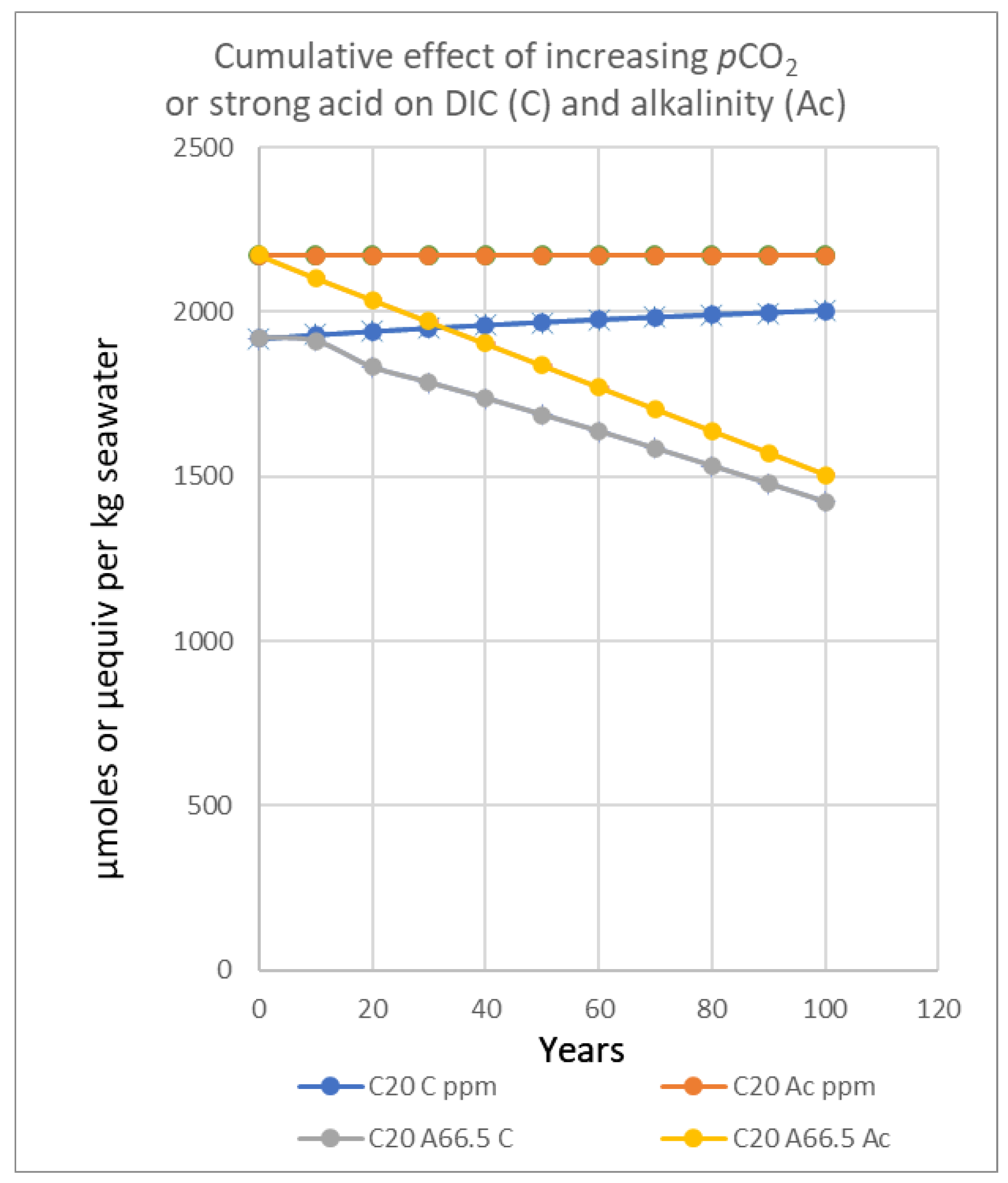

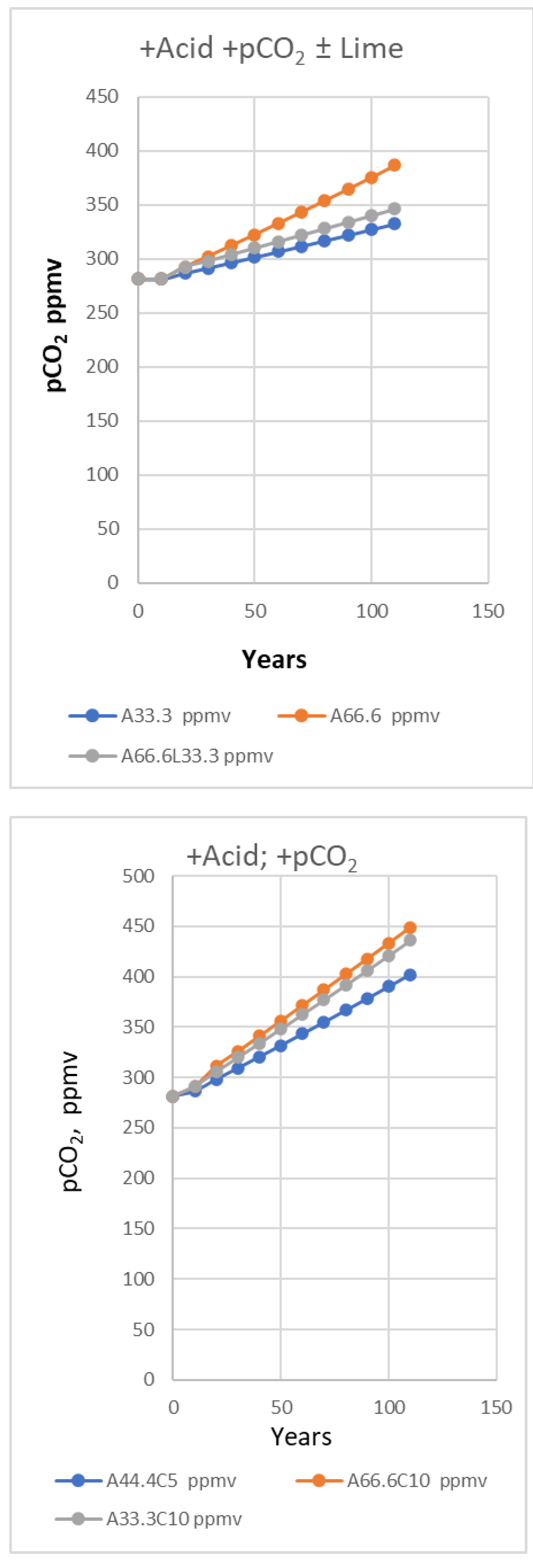

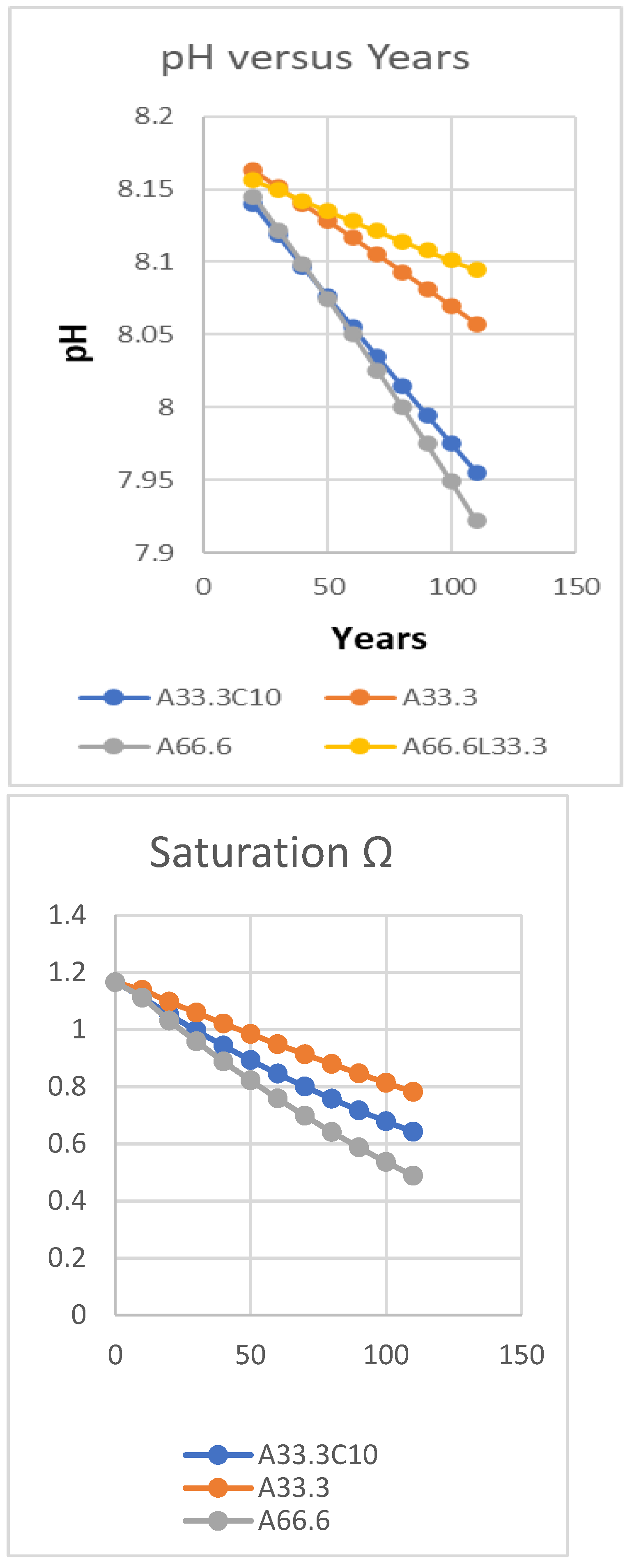

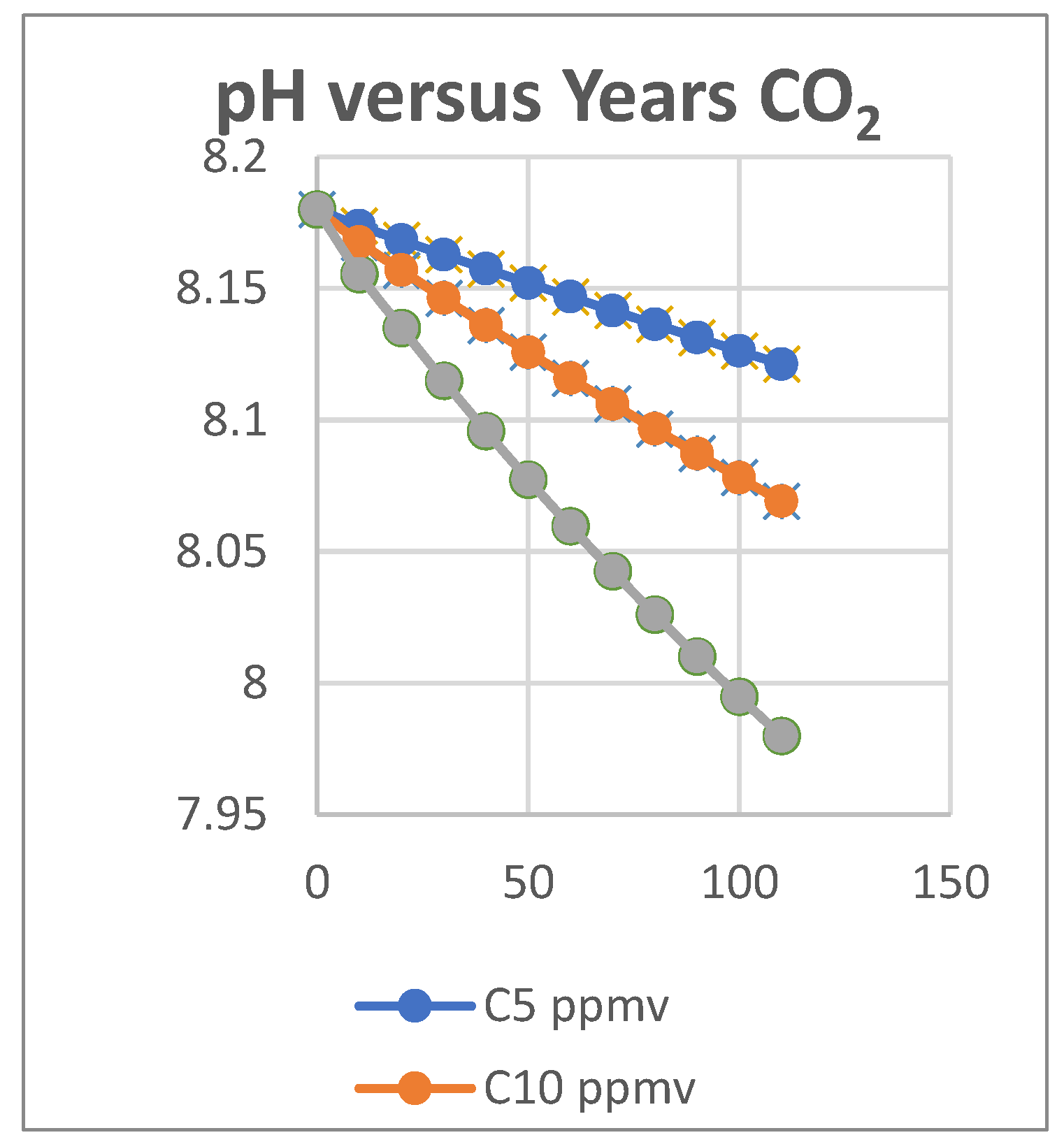

Reiterative processes with time for injections of acids (or bases), both strong and weak were established, yielding variations for pH, pCO2 (atm), residual alkalinity for inorganic carbon (Ac) and borate (Ab). A uniform mixing zone in seawater of 65 m depth was assumed for calculations, although this depth is known to vary with latitude and is generally deeper in the southern hemisphere. That may mean that equilibration is faster in southern waters, from a stronger gradient. For soils to 1 metre depth and surface waters on land, representative values for temperature, salt concentration and pH are assumed.

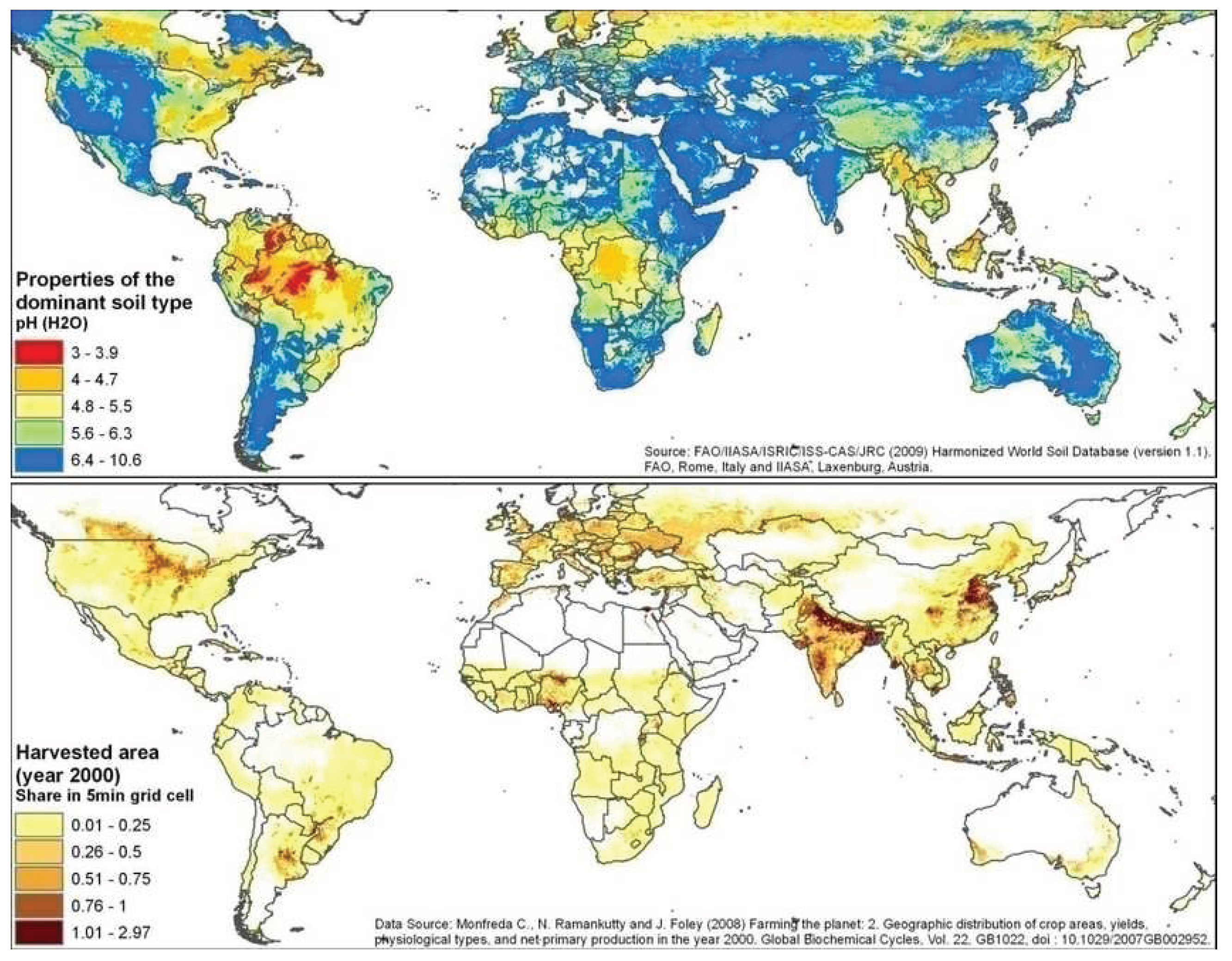

A key difference between seawater and water on land or in soil is its pH value, generally held near 8.1-8.2 in the ocean surface, but far more variable in soil, often below pH 7 and as low as pH 4, depending on histories of soil development and methods of cultivation [

4]. A second difference is the salt (NaCl) concentration, generally ca. 3.5% (S=35‰) in seawater except where diluted by rivers but highly variable in water on land, usually with much less salt.

Millero [

13] has cautioned that algorithmic methods for estimating constants with seawater become less accurate with saline content less than 0.5%, so we do not expect similar accuracy for freshwater in this article, while continuing to use the same computer code as for seawater. However, refinement would only make marginal differences in the values, not important enough for the purpose of this article. Specific details of the programs used to obtain numerical results are given in

Supplementary Materials. including all computer coding.

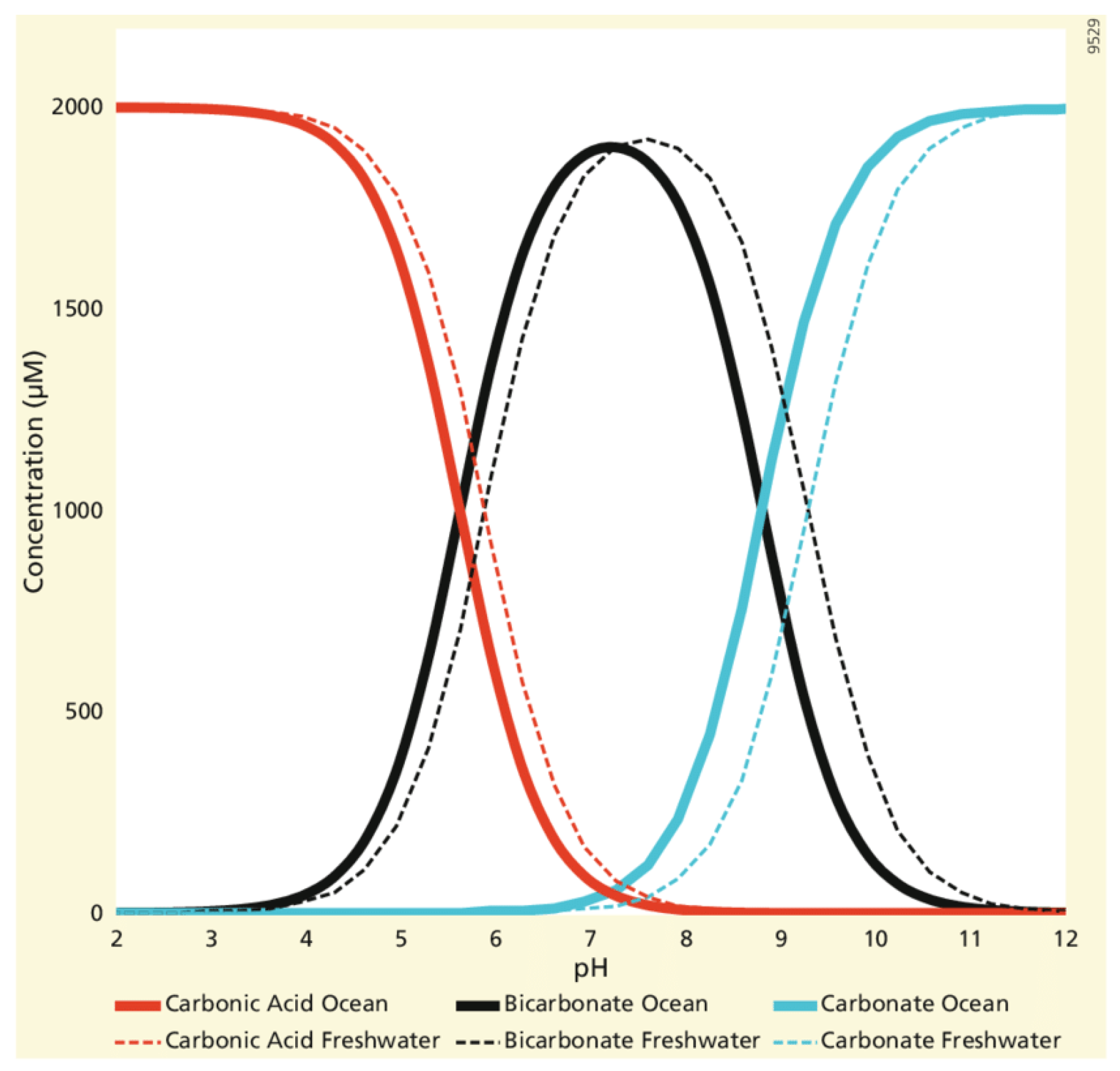

Figure 4 illustrates the relative distribution of inorganic carbon (2 mM) species with pH for ocean or freshwater within a closed vessel with the same total concentration of carbon species (C) at all pH values. The diagram shows how the equilibria are displaced to lower pH values in ocean water, where sea salt reduces the chemical potential of water. However, this Bjerrum diagram is misleading for this article because it is a closed system, not equilibrating with the atmospheric fugacity for CO

2. To be at equilibrium at pH 2, the atmosphere would be 8% CO

2,, some 200 times greater than at present, making human life impossible. If allowed to equilibrate with the actual

pCO

2 in air, the level of dissolved CO

2 would be much lower, a function of temperature and pressure.

However, more realistic environmental distributions for DIC in sea and land are investigated in Results and Discussion. Initially, an analysis of possible rates of acidification from fossil fuel emissions will be made. Then, modelling effects of strong acidification on the fugacity of CO2 in the mixing zone of seawater will be executed. Finally, acidification processes on land will be examined before weighing the overall evidence for a significant role of surface pH in regulating atmospheric pCO2.