1. Introduction

Football and all the parameters that affect performance (conditional, technical, tactical, age, gender, etc.), have evolved over the years towards a more specific and individual work from the area of professional performance and areas of training and talent detection [

1]. However, few studies focus on the body composition (BC) variable for the direct assessment of performance in football and the adaptations produced by the different training cycles during the season [

2]. Although it is a relatively recent assessment method, there are studies that attempt to define the individual characteristics of players in terms of BC, somatotype and morphological proportionality [

3,

4]. At present, the BC and anthropometric characteristics of young players are little considered in the selection of young football players, as the focus is often placed on the skills that each individual has in their respective speciality [

5] or much more time is devoted to increasing the physical aptitudes of athletes without taking into account the evaluation of their CC and nutritional status [

6], even though we know that there are currently differences in terms of physiological demands according to the position of the player and with respect to their weight, height and body mass index (BMI) [

7].

If we refer to the study of CC in football and its relationship with health and injuries, BMI is commonly referred to instead of %BMG, however, it has been determined that abdominal fat and circumference, as well as overweight indicated in %BMG are better discriminators of injury risk and health status than BMI [

8,

9]. We should point out that BMI does not distinguish between fat-free mass, where we include muscle mass (MM) or bone, and fat mass (FM), nor does it distinguish between fat distribution, knowing that abdominal fat, especially intra-abdominal fat, and fat in the gluteal-femoral region may even have a greater impact on health [

10,

11]. We can indicate that a high body weight and an increase in %MG, with a greater impact on locomotor actions typical of football such as running or jumping, create a mechanical stress on the joint system and the axial skeleton, increasing the risk of injury [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. Other authors who have related CC to injuries suffered by football players have shown that the ratio of fat mass to bone mass of a body segment correlates inversely with the risk of injury [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. In this sense, we can indicate that low fat-free mass (FFM) values are associated with low levels of strength, which leads to sports injuries [

14]. Similarly, there is a relationship between increased BMI and low %FMG values with an increased risk of injury for young football players [

15]. Finally, there is evidence that higher WM values and lower GM allow the player to avoid traumatic injuries resulting from contact [

16].

Generally speaking, CC is usually measured at the beginning of the pre-season period and then monitored at regular intervals during the season, usually every 1-2-3 months [

17]. The assessment of CC is a fundamental aspect of the functional assessment of the human body in health, clinical and physical performance [

18]. The methods and frequency of QC assessment are numerous and of varying complexity depending on the level of analysis, methods, number of compartments estimated or quantified, resources available to the team, as well as their preferences. Currently, CC analysis methods are divided into three groups: direct, indirect and doubly indirect. The direct method involves cadaveric dissection and although it has excellent reliability, its application and usefulness is very limited [

19]. These methods are validated on the basis of the direct method or densitometry and make it possible to measure/estimate body tissues [

20]. Despite their high reliability, indirect methods are not very accessible, limited and costly [

21]. Double indirect methods were validated on the basis of indirect methods and therefore have a very large margin of error when compared to indirect methods [

19]. However, in view of the high costs of indirect methods and methodological sophistication, dual indirect methods such as anthropometry and BIA are gaining importance due to their simplicity, safety, ease of interpretation and low cultural constraints [

21].

In short, the control and evaluation of CC can be a key factor in football, as it can be used to determine the degree of preparation of young players to assimilate training loads, to evaluate their training capacity, as well as to evaluate the effectiveness of training programmes [

22]. To compare the percentages of quarterly change for each of the variables analysed (height, weight, body fat percentage and muscle mass) as a function of the quarter in a sample of adolescent football players and 2. To compare the percentages of quarterly changes as a function of the variables analysed (height, weight, body fat percentage and muscle mass).

2. Materials and Methods

The CC evaluation was carried out during the 21-22 season (September-June) and always once a month (Match Day -3 in the second week of each month). The assessment session was conducted in the same well-ventilated room with controlled temperature and humidity following the standard food and fluid protocol so that they presented in a rested state, fasted overnight and hydrated before the test. They were also asked to arrive with an empty bladder and bowel [

23]. Subjects wore only shorts during testing and removed any metal and jewellery prior to testing. They were asked to avoid strenuous exercise, alcohol and any stimulants for 24 h prior to testing [

24].

Participants

The sample consisted of young male football players of different categories belonging to a high-performance football academy, with more than 5 years in the sport of football and who spent 1 full year at the academy. Twelve players were excluded from the sample, of which seven were on a temporary basis (days, weeks or months) and five players were injured for more than two months during the intervention period. All players, parents and/or guardians, together with the academy managers, were notified of the research design and its requirements, as well as the potential benefits and risks prior to the start of the study, by providing and signing the informed consent form for under-aged and over-aged players. Prior to the start of the study, the players were given the protocol of the physical testing procedure and the corresponding training programme. In addition, it was explained collectively in a group meeting and by means of audiovisual tools. They all voluntarily accepted to participate in this study.

Material

A SECA® wall stadiometer (model 206, Hamburg, Germany) with an accuracy of 0.5 cm was used to monitor height. For the control of body composition variables (weight, % fat and muscle mass), a Tanita® (model MC-980MA PLUS, Arlington Heights, Illinois) was used for Bioimpedance Analysis (BIA). Before the BIA measurement, the hands and feet of the participants were wiped with an electrolyte wipe [

24].

Data collection was always performed at the same time (7:45 am) and on a monthly basis. First, the height was checked (without shoes) and then the height, age and sex data were entered into the Tanita®, where the players were taken barefoot, fasting and without any metallic material [

1]. The QC was performed with the players standing with their feet in contact with the electrodes in the foot area of the scale and their hands on the handles, placing their fingers in the standard locations [

24].

3. Results

Two-way repeated measures ANOVA revealed for anthropometric variable (

Table 1), P_value < 0.001 (F = 103.7; df = 514), so we can conclude that the effect of trimester reaches conventional levels of statistical significance. Similarly, we can also conclude that anthropometric variable *age is not significant (p = 0.97; F = 0.44; df = 1548). If we consider the effect of trimester x age, it can be found how the BFP and Muscle mass variables show significant improvements (P_value < 0.001). Likewise, trimestral perceptual change shows significant differences in weight, height and muscle mass (P_value < 0.001), but not in the height variable.

The within-group analysis for trimester, the P_value is < 0.001, so anthropometric variable has significant effect on subjects. Interaction anthropometric variable*age have not significant effect (P_value = 0.63). Regarding between-subjects analysis, in this case there were no significant differences (p = 0.35).

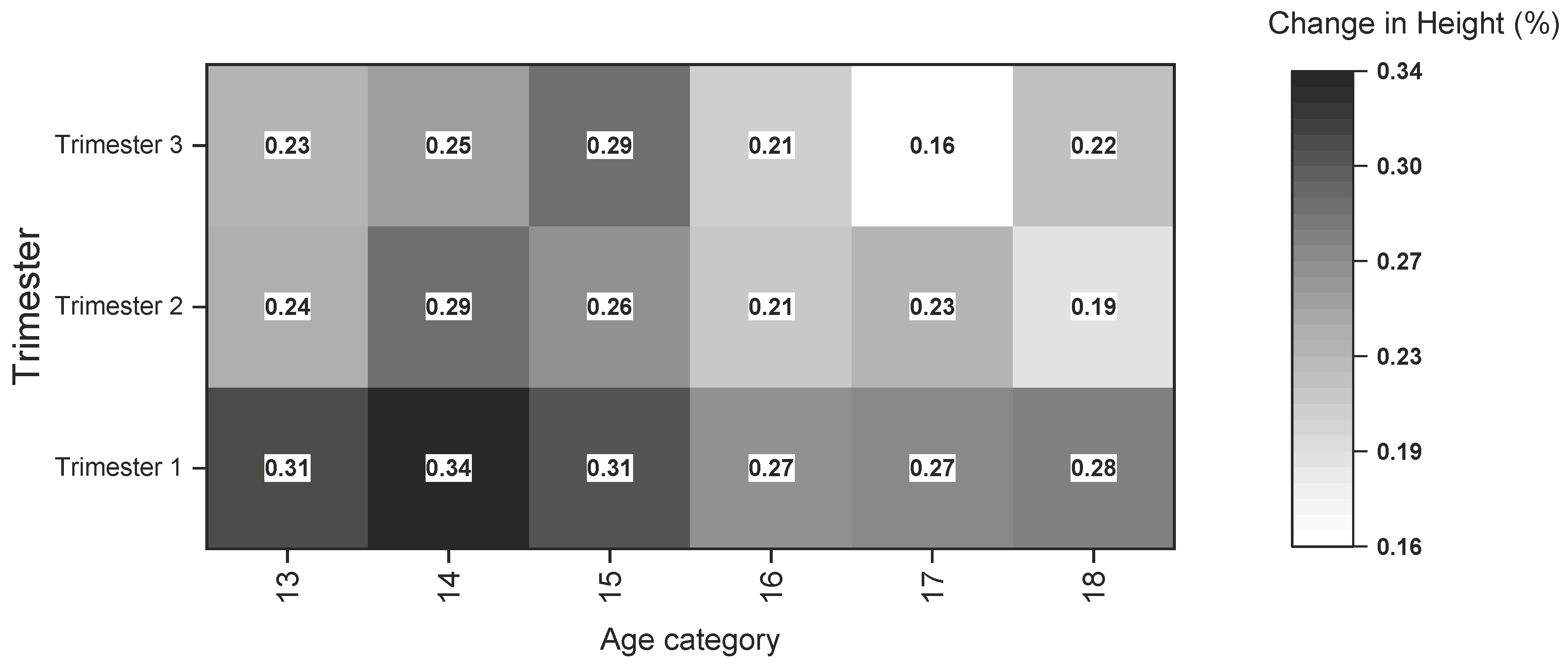

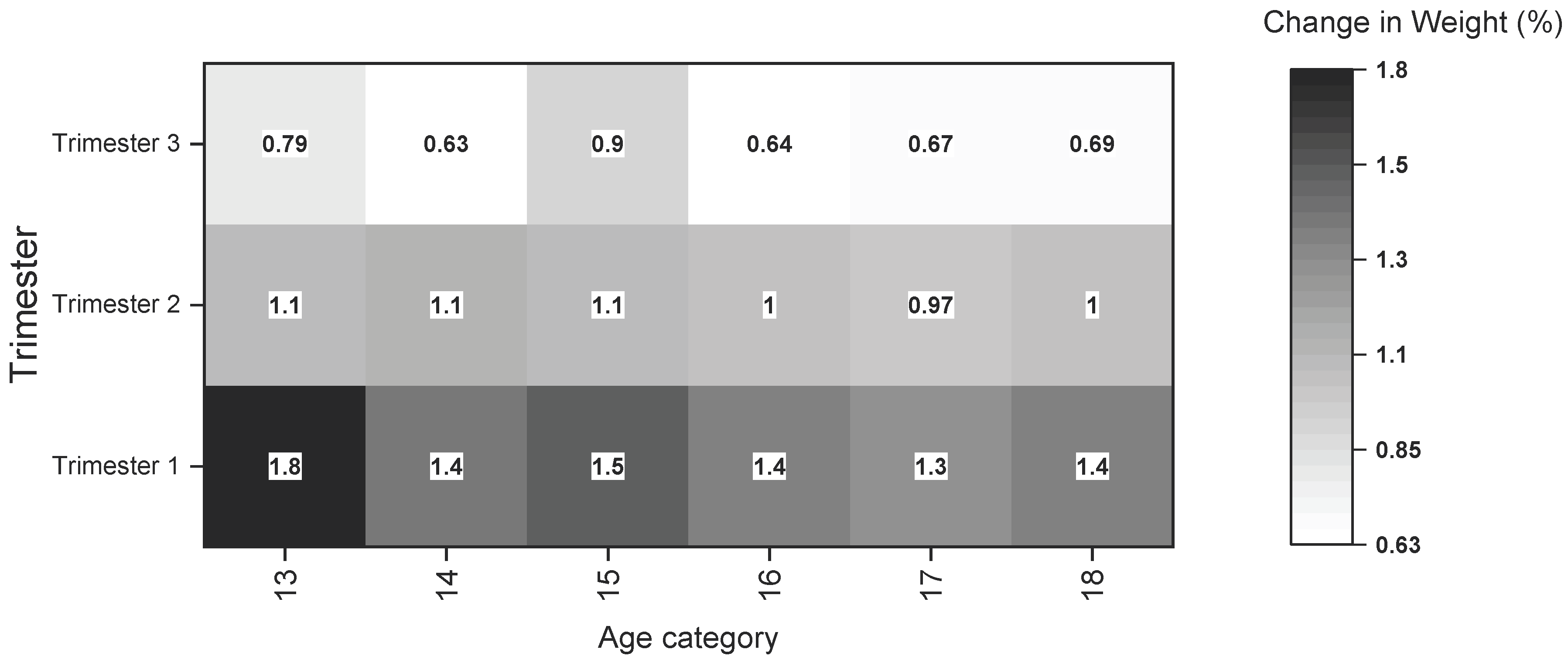

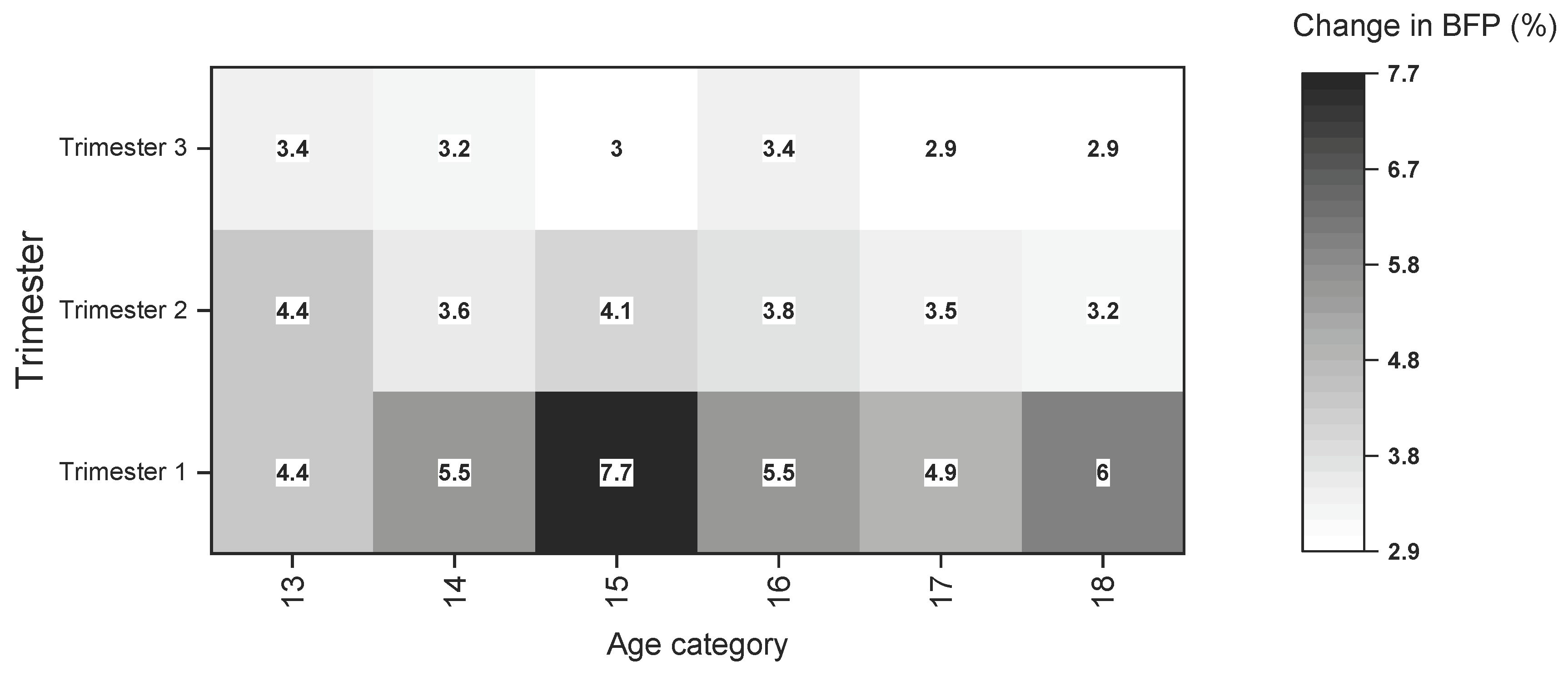

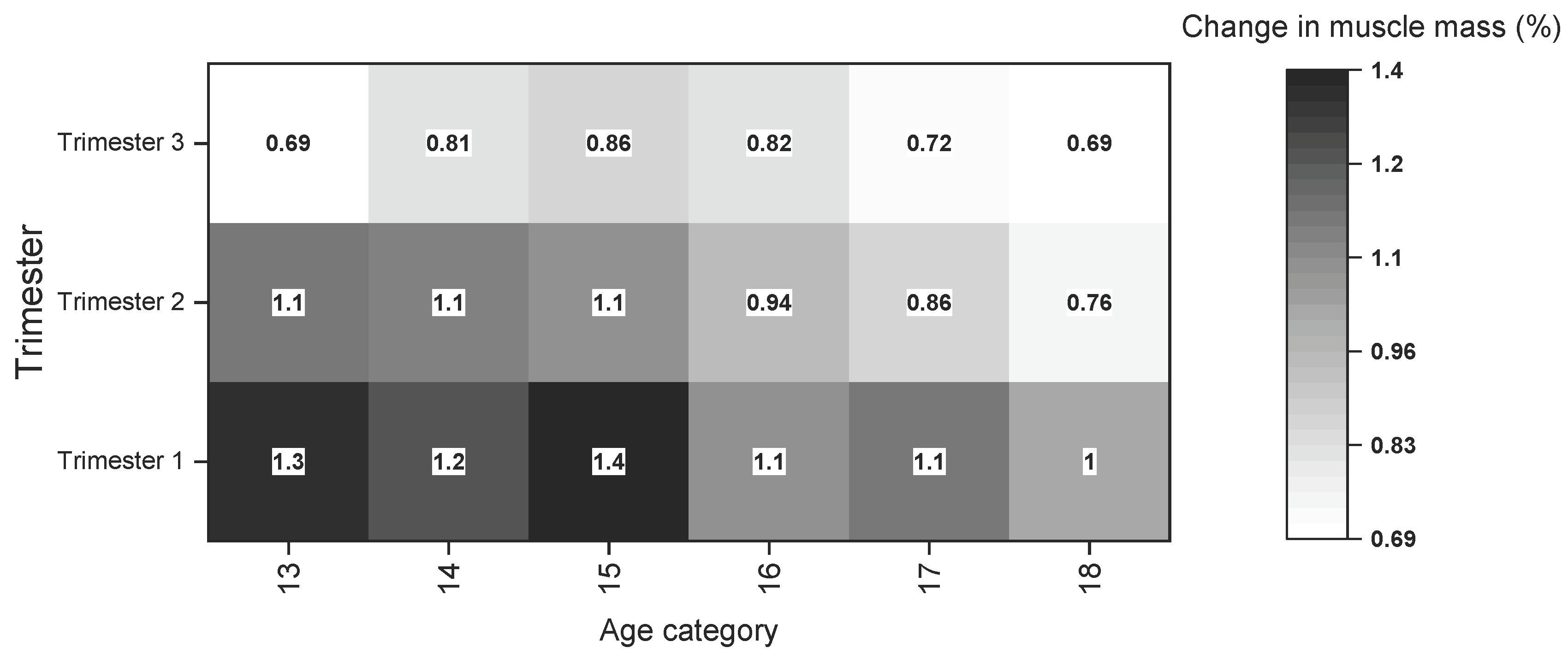

In the following figures (

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4), you can see the percentage changes in each trimester according to the age of the participants.

4. Discussion

The purpose of this study was two-fold, to compare the trimestral change percentages for each of the variables analyzed (height, weight, body fat percentage, and muscle mass) as a function of the trimester in a sample of adolescent soccer players and to compare the trimestral change percentages as a function of the variables analyzed. Several studies have reported seasonal variations in the physical fitness and anthropometrical variables of young soccer players [

25,

26]. This study revealed a significant improvement in all the anthropometrical indicators analyzed from the start to the end of the season. However, it must be recognized that maturity state is a variable that can influence such changes [

25].

According to the results found in the present study, it is observed that from 13 to 15 years of age, there are greater changes per quarter in the height of the players. As expected from a previous study of European youth players [

27], the highest increases in height and weight occurred when players turned 14 years of age. When analyzing body composition, it was noticed an interesting nuance, as it turns out that the peak gain in muscle mass occurs a year after the peak gain in body weight [

26]. This is possible because fat mass decreases due to rapid growth and testosterone secretion increases while muscle mass increases. Testosterone is known to reduce triglyceride synthesis [

28]. Muscle mass as a percentage of body weight improved from 3.09% at age 13 to 3.36% at age 15, which is consistent with results for the general population [

28,

29]. According to [

25], several physical fitness variables such as limb movement speed, core strength, explosive power, running speed, agility, cardiorespiratory endurance, and anaerobic capacity all show greatest development at peak height, with weight and height gain occurring at the age of 13.8 years. Therefore, it is very relevant to prepare physical exercise programs aimed at improving these physical capacities in this age range.

Based on the results shown in this study on BFP and muscle mass, it can be seen that there is a reduction in the percentage of fat mass, to a greater extent in the first trimester, and an increase in the percentage of muscle mass. It is worth noting that the decrease in BFP observed at this age was due to athletes gaining muscle due to maturational development rather than losing fat mass [

22,

30]. This fact is also consistent with the observations of Hannon et al (2020) [

31] and to some extent corroborates the idea that muscle mass is of greater importance for football player performance throughout development than body fat, especially in young soccer players. In this sense, it is well known that body composition, especially body fat percentage, can negatively affect aerobic and anaerobic capacity, strength, power and speed as players advance in age [

32,

33]. Likewise, there is evidence that muscle mass plays a vital role in improving physical performance.

In this sense, this study shows how the changes in each of the variables occur in a greater proportion during the first trimester. As the season continues, the rate of change slows down. When individuals start a new exercise program, especially one that includes medium and high intensity aerobic training (for instance, soccer), they often experience significant changes in anthropometric variables such as body mass, body fat percentage, and muscle mass during the first few weeks (first trimester) [

34,

35]. This is because the body has adapted to the new level of physical demand and requires more advanced or intensive training to continue progressing [

36]. Additionally, diet and genetics can play a significant role in how these variables change over time [

29]. It's also crucial to remember that everyone's body responds differently to exercise, and individual results can vary.

This study had some limitations. To begin with, this study only incorporates anthropometric variables and does not refer to their influence on the physical or sports performance of young players. Therefore, it would be important to research into these correlations to better understand the changes produced and their influence on physical development. On the other hand, it would be important to know what type of training the players carry out at each of the ages in order to be able to discern if the changes produced in each of the anthropometric variables may be influenced by it.

5. Conclusion

As a practical implication, this study showed that between the ages of 13 and 15, results in body composition, improve in soccer players with a strong relationship with the increase in muscle mass and decrease on body fat percentage due to growth development, and that changes in each variable occurred to a greater extent in the first trimester. As the season progresses, the rate of change slows down. Therefore, it seems important to modulate the training load based on the specific age response, especially in young soccer players. However, it's important to note that these improvements can vary significantly between individuals, depending on factors such as genetics, diet, sleep, and the specific type and intensity of training. Monitoring these variables should be done with care, keeping the players' health as the top priority. Also, coaches and trainers should foster a balanced view of these metrics, encouraging players to focus on skill development and enjoyment of the sport rather than solely on physical changes.

Author Contributions

All authors confirm that meet the criteria: conceived and planned the work that led to the paper and interpreted the evidence it presents; they wrote the paper and took part in the revision process; the authors approved the final version. Therefore, all authors declare that they have read and approved the final submitted manuscript. Conceptualization, M.FP., R.MM., G.GD. and J.C.CM.; methodology, M.FP., R.MM., R.M.S. and J.C. CM.; software, M-FP.,R.MM., R.M.S. and J.C.CM.; validation, M.FP., R.MM., G.GD. and R.M.S.; formal analysis, M.FP. and J.C.CM.; investigation, M., F.P-. R.,MM. and J.C.MM.; resources, M-FP-. R.MM-,R-M-S. and H.I.C.; data curation, M.FP., G.GD. and H.I.C.; writing—original draft preparation, M.FP., R.MM, R.M.S. and J.C. CM.; writing—review and editing, M.FP., and J.C.CM.; visualization, M.FP.,R.MM. and J.C.CM.; supervision, M.FP and JC.CM.; project administration, R-MM. H.I.C and J.C.CM.; funding acquisition, H.I.C.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This research received no external funding. No specific sources of funding were used to assist in the preparation of this article.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Universidad Pontificia de Comillas (Madrid, Spain) under reference number 2021/86, and signed on 13 October 2021. Players and their parents or guardian were invited to sign an informed consent document before any of the tests were performed.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Records from this study will be kept for at least 5 years.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the coaches and players for their willingness to participate in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The researchers affirm that there were no financial or commercial ties that might be seen as creating a conflict of interest during the research's conduct.

References

- Falces-Prieto, M.; González-Fernández, F.T.; Baena-Morales, S.; Benítez-Jiménez, A.; Martín-Barrero, A.; Conde Fernández, L.; Suárez Arrones, L.; Sáez de Villarreal, E. Effects of strength training program with self-loading on countermovement jump performance and body composition in young soccer players. J. Sport Health Res. 2020, 12, 112–125. Available online: https://recyt.fecyt.es/index.php/JSHR/article/view/80797 (accessed on 18 March 2024).

- Brocherie, F.; Girard, O.; Forchino, F.; Al Haddad, H.; Dos Santos, G.A.; Millet, G.P. Relationships between anthropometric measures and athletic performance, with special reference to repeated-sprint ability, in the Qatar national soccer team. J.Sports Sci. 2014, 32, 1243–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardasevic, J.; Bjelica, D. Body Composition Differences between Football Players of the Three Top Football Clubs. Int. J. Morphol, 2020, 38, 153–158. Available online: https://d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net/72804116/0717-9502-ijmorphol-38-01-153-libre.pdf?1634384158=&response-content-disposition=inline%3B+filename%3DBody_Composition_Differences_between_Foo.pdf&Expires=1710870896&Signature=Xh9EH~Ox1PBH~tRkqVhbch8jqIeic~RGFMxmVjh8Mcxo-rqh1~8WXs8GEj2dLWGvTExmuwQvEVyu2RgFJqB9e1hg2nAJJH9MBG-Iw1V0TKkz6EsU3x~ML4HoUsBfZ8ZQ42cghl14wWgLVheeLKn~NT8goBCP8E9vF-jCV10pONSOabivMDiyh98k3YjmuTBzAiTSY~rpcnE4npZ9U~2U8FGO103l8pIh5FWNTyTXkneyHpwqDoaq2RNCWEUCb4FgeqNAl0SqDkzwB-~VGm-StKUVMvPKS77M5QyBQ1~dI-0KvbjQOAOEteCjwTvTCQr8Kfnbga4faM4IQ54XLt4JXg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAJLOHF5GGSLRBV4ZA (accessed on 18 March 2024). [CrossRef]

- Gardasevic, J.; Bjelica, D.; Vasiljevic, I. Morphological Characteristics and Body Composition of Elite Soccer Players in Montenegro. Int. J. Morphol, 2019, 37, 284–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorquera-Aguilera, C.; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, F.; Torrealba-Vieira, M.I.; Barraza-Gómez, F. Body Composition and Somatotype of Chilean Soccer Players Sub 16 y Sub 17. Int. J. Morphol, 2012, 30, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triki, M.; Rebai, H.; Abroug, T.; Masmoudi, K.; Fellmann, N.; Zouari, M.; Tabka, Z. Comparative study of body compositionand anaerobic performance between football and judo groups. Sci Sports, 2012, 27, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, P.L.; Chamari, K.; Dellal, A.; Wisløff, U. Relationship between anthropometric and physiological characteristics in youth soccer players. J. Strength Cond. Res, 2009, 23, 1204–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, D.; Lizarraga, A.; Drobnick, F. Injury prevention and nutrition in football. Sports Sci Exch, 2014, 27, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Nye, N.S.; Carnahan, D.H.; Jackson, J.C.; Covey, C.J.; Zarzabal, L.A.; Chao, S.Y.; Crawford, P.F. Abdominal Circumference Is Superior to Body Mass Index in Estimating Musculoskeletal Injury Risk. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 2014, 46, 1951–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez-Carmona, W.; Sánchez-Oliver, A.J. Índice de masa corporal: ventajas y desventajas de su uso en la obesidad. Relación con la fuerza y la actividad física. Nutr Clin Med, 2018, 12, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellido, D. ; Bellido; V Body composition in children and adolescents: looking for the best technique. Nutr Hosp. 2016, 33, 1013–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunc, V.; Hráský, P.; Skalská, M. Changes in body composition, during the season, in highly trained soccer players. Open Sports Sci. J., 2015, 8, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chena-Sinovas, M.; Pérez-López, A.; Álvarez-Valverde, I.; Bores-Cerezal, A.; Ramos- Campo, D.J.; Rubio-Arias, J.A.; Valadés-Cerrato, D. Influence of body composition on vertical jump performance according with the age and the playing position in football players. Nutr Hosp, 2015, 32, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campos RA, G.; Bolaños MA, C.; Hespanhol, J.E.; Germano, Y.; Maria, T.S.; Gamero, D.; Arruda, M. Body composition of professional footballers based on chronological age. Conexões, 2014, 12, 70–81. [Google Scholar]

- Kemper GL, J.; Van der Sluis, A.; Brink, M.S.; Visscher, C.; Frencken WG, P.; Elferink-Gemser, M.T. Anthropometric injury risk factors in elite-standard youth soccer. Int. J. Sports Med, 2015, 36, 1112–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perroni, F.; Vetrano, M.; Camolese, G.; Guidetti, L.; Baldari, C. Anthropometric and Somatotype Characteristics of Young Soccer Players: Differences Among Categories, Subcategories, and Playing Position. J. Strength Cond. Res, 2015, 29, 2097–2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lesinski, M.; Prieske, O.; Helm, N.; Granacher, U. Effects of soccer training on anthropometry, body composition, and physical fitness during a soccer season in female elite young athletes: a prospective cohort study. Front. Physiol, 2017, 8, 1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carnero, E.A.; Alvero-Cruz, J.R.; Giráldez, M.A.; Sardinha, L.B. La evaluación de la composición corporal" in vivo": parte I: perspectiva histórica. Nutr Hosp, 2015, 31, 1957–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa-Moreira, O.; Alonso-Aubin, D.A.; Patrocinio-de Oliveira, C.E.; Candia- Luján, R.; de Paz, J.A. Métodos de evaluación de la composición corporal: una revisión actualizada de descripción, aplicación, ventajas y desventajas. Arch Med Deporte, 2015, 32, 387–394. Available online: https://archivosdemedicinadeldeporte.com/articulos/upload/rev1_costa_moreira.pdf (accessed on 18 March 2024).

- Piñeda-Geraldo, A.; Amórtegui-Monroy, I.; Rodríguez-Posada, C.; Rojas-Sandoval, Y.; Santana-Gutiérrez, L. Methods and anthropometric techniques for the calculation of body composition. Rev. Ing. Mat. Cienc. Inf. 2018, 5, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sousa, M.; Priore, S.E.; Franceschini SD, C. Métodos de avaliação da composição corporal em crianças. Rev Paul Pediatr, 2009, 27, 315–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toselli, S.; Mauro, M.; Grigoletto, A.; Cataldi, S.; Benedetti, L.; Nanni, G.; Di Miceli, R.; Aiello, P.; Gallamini, D.; Fischetti, F. Assessment of Body Compositionand Physical Performance of Young Soccer Players: Differences According to the Competitive Level. Biology 2022, 11, 823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, Y.; Nishizawa, M.; Uchiyama, T.; Kasahara, Y.; Shindo, M.; Miyachi, M. Developing and validating an age-independent equationusing multi-frequency bioelectrical impedance analysis for estimation ofappendicular skeletal muscle mass and establishing a cutoff for sarcopenia. Int.J. Environ. Res. Public Health, 2017, 14, E809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez, F.J.; Munguía-Izquierdo, D.; Suárez-Arrones, L. Validity of Field Methods to Estimate Fat-Free Mass Changes Through out the Season in Elite Youth Soccer Players. Front. Physiol 2020, 11, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, R.; Emmonds, S.; Jones, B.; Myers, T.D.; Clarke, N.D.; Lake, J.; Till, K. Seasonal changes in physical qualities of elite youth soccer players according to maturity status: comparisons with aged matched controls. Sci. Med. Footb, 2018, 2, 272–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vänttinen, T.; Blomqvist, M.; Nyman, K.; Häkkinen, K. Changes in body composition, hormonal status, and physical fitness in 11-, 13-, and 15-year-old Finnish regional youth soccer players during a two-year follow-up. J Strength Cond Res, 2011, 25, 3342–3351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovell, R.; Towlson, C.; Parkin, G.; Portas, M.; Vaeyens, R.; Cobley, S. Soccer player characteristics in English lower-league development programmes: The relationships between relative age, maturation, anthropometry and physical fitness. PloS one, 2015, 10, e0137238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, C. H.; Choi, S. H. Metabolism of Estrogen and Testosterone and Their Role in the Context of Metabolic Diseases. Sex/Gender-Specific Medicine in the Gastrointestinal Diseases, Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2022; 27–35. Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-981-19-0120-1_3 (accessed on 18 March 2024).

- Hannon, M.P.; Flueck, J.L.; Gremeaux, V.; Place, N.; Kayser, B.; Donnelly, C. Key nutritional considerations for youth winter sports athletes to optimize growth, maturation and sporting development. Front. Sports Act. Living, 2021, 3, 599118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abarghoueinejad, M.; Baxter-Jones, A.D.; Gomes, T.N.; Barreira, D.; Maia, J. Motor performance in male youth soccer players: a Systematic Review of Longitudinal Studies. Sports, 2021, 9, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannon, M.P.; Close, G.L.; Morton, J.P. Energy and macronutrient considerations for young athletes. Strength Cond J, 2020, 42, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahraman, M.Z.; Arslan, E. The relationship between body composition and biomotor performance parameters in U18 football players. Phys. educ. stud., 2023, 27, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spehnjak, M.; Gušić, M.; Molnar, S.; Baić, M.; Andrašić, S.; Selimi, M.; Mačak, D.; Madić, D.M.; Žilič Fišer, S.; Sporiš, G.; et al. Body composition in elite soccer players from youth to senior squad. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health, 2021, 18, 4982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rinaldo, N.; Toselli, S.; Gualdi-Russo, E.; Zedda, N.; Zaccagni, L. Effects of anthropometric growth basketball experience on physical performance in pre-adolescent male players Int, J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.F.; Aghidemand, M.H.; Kharatzadeh, M.; Ahmadi, V.K.; Oliveira, R.; Clemente, F.M.; Murawska-Ciałowicz, E. Effects of high-intensity resistance training on physical fitness, hormonal and antioxidant factors: a randomized controlled study conducted on young adult male soccer players. Biology, 2022, 11, 909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña-González, I.; Fernández-Fernández, J.; Cervelló, E.; Moya-Ramon, M. Effect of biological maturation on strength-related adaptations in young soccer players. PloS one 2019, 14, e0219355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).