1. Introduction

Leptospirosis, one of the most common global neglected zoonotic infections caused by pathogenic spirochetes of the genus

Leptospira, significantly impacts global human health, infecting more than a million people and causing approximately 60,000 deaths annually [

1,

2]. Current recommendations for treating human leptospirosis involve beta-lactam antibiotics such as penicillin, ampicillin, ceftriaxone, or cefotaxime [

3,

4]. Alternative therapeutic options, particularly for those with allergies to beta-lactam antibiotics, include oral doxycycline or azithromycin [

5,

6,

7].

Importantly, antibiotic treatment, while targeting infection, can lead to gut dysbiosis, characterized by reduced diversity, altered abundance of specific taxa (e.g., an increase in the abundance of

Clostridium difficile and, as a result, the risk of developing pseudomembranous colitis), and the emergence of antibiotic-resistant microbes [

8,

9,

10]. Due to their tendency to target specific hosts, phages generally have minimal impact on beneficial bacteria and may be good therapeutic options in the future [

11]. However, we have not yet found clinical data about the use of phages for treating leptospirosis.

Leptospira species primarily inhabit damp environments, where they are prone to encountering diverse phages and plasmids, in addition to their ability to infect both humans and animals. In 1990, Saint Girons et al. successfully extracted bacteriophages from Leptospira species [

12].

Currently, only 3 types of phages that infect Leptospira (referred to as leptophages) are known: vB_LbiM_LE1 (also known as LE1), vB_LbiM_LE3 (LE3), and vB_LbiM_LE4 (LE4) [

12,

13]. It is interesting to note that a search for prophages closely related to LE4 in Leptospira genomes led to the identification of a corresponding plasmid in

L. interrogans and a prophage-like region in the genome of a clinical strain of

L. mayottensis [

14]. Additionally, Schiettekatte et al. demonstrated that leptophages utilize lipopolysaccharides (LPS) as receptors on bacterial cells [

15].

Considering the presence of leptophages, it is likely that leptospires should have appropriate natural protection systems against phages to limit phage infection [

16]. Guohui Xiao et al. described the presence of the CRISPR‒Cas system; however, as is known, microorganisms have a whole arsenal of defense systems against phages [

17,

18]. Antiphage defense systems exhibit a nonrandom distribution in microbial genomes, often forming "defense islands" where multiple systems cluster together [

19,

20,

21]. Several studies have revealed that different strains of the same bacterial species may encode distinct defense systems [

21]. Given the limited data on the diversity of antiphage systems in leptospirosis, this study aimed to characterize antiphage systems in leptospirosis.

2. Materials and Methods

We downloaded 402 genomes of

Leptospira interrogans in FASTA format from the Bacterial and Viral Bioinformatics Resource Center (BV-BRC) database in December 2023 (consisting of 52 complete genomes and 350 whole-genome shotgun (WGS) sequences) [

22].

DefenseFinder was used to identify defense systems in each

Leptospira strain [

23]. DefenseFinder is a specialized computational tool designed to detect prokaryotic antiviral defense systems within genomic sequences. It utilizes MacSyFinder, which employs a two-step process: first, proteins are detected using hidden Markov model (HMM) profiles, and then decision rules are applied to filter hits based on genetic architecture [

24]. DefenseFinder constructs or adapts HMM profiles for relevant proteins and incorporates system-specific decision rules for accuracy. Statistical analysis and visualization were performed using SRplot, jvenn, and Python [

25,

26]. The raw data are available in the Supplementary File.

3. Results

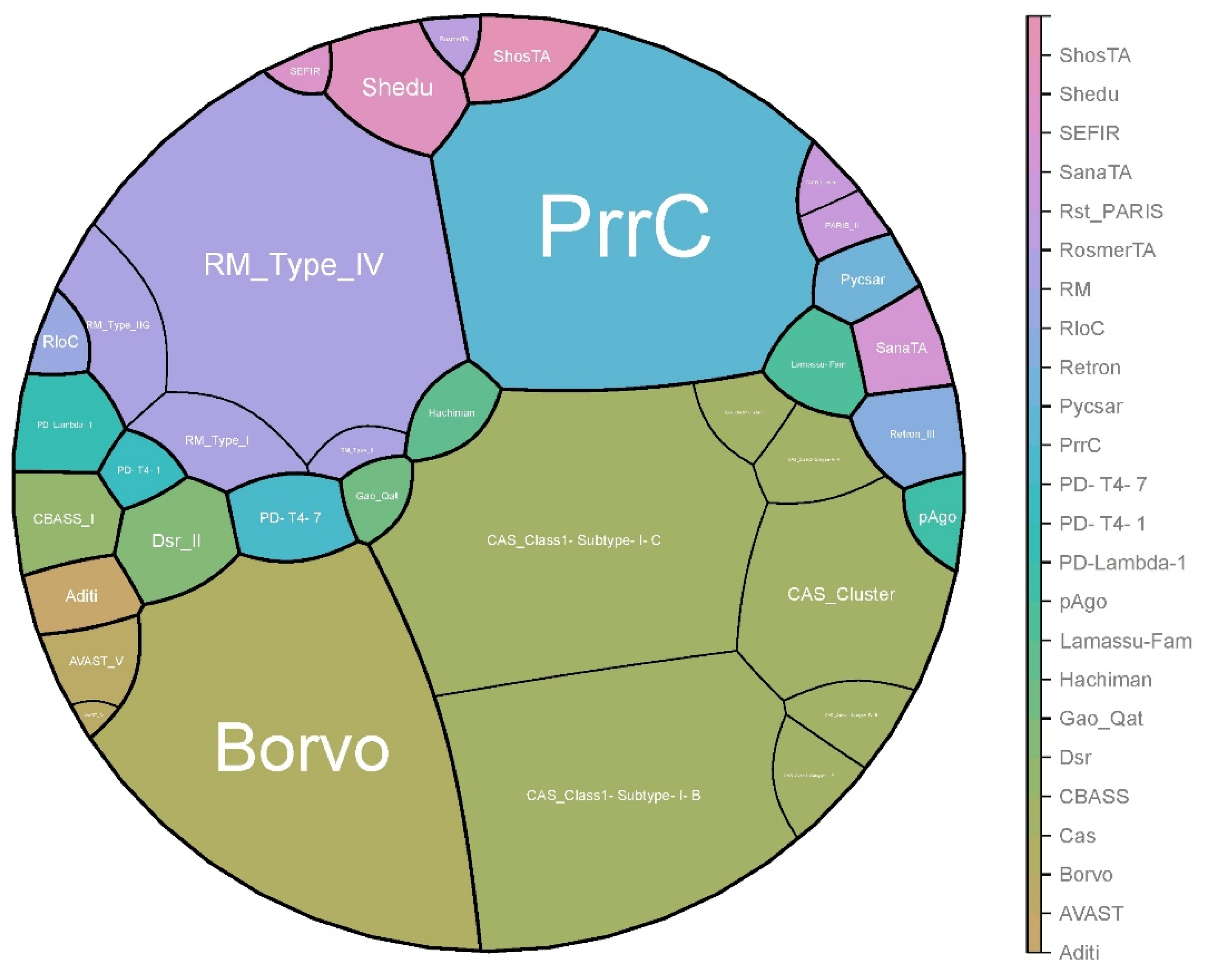

In total, 24 antiphage systems were identified among all studied strains. The most widespread systems were Cas (all strains), PrrC (n = 391 strains), Borvo (n = 388 strains), and R-M (R-M_Type_IV, n = 348 strains). CAS_Class1-Subtype-I-C (n = 399 strains) and CAS_Class1-Subtype-I-B (n = 354 strains) were the most common CRIPSR-Cas subtypes.

The rarest were AVAST_IV, CAS_Class1-Subtype-I-E, CAS_Class1-Subtype-IV-B, CAS_Class1-Type-I, Gao_Qat, PD-T4-1, and RosmerTA, which were detected in only one strain (

Figure 1).

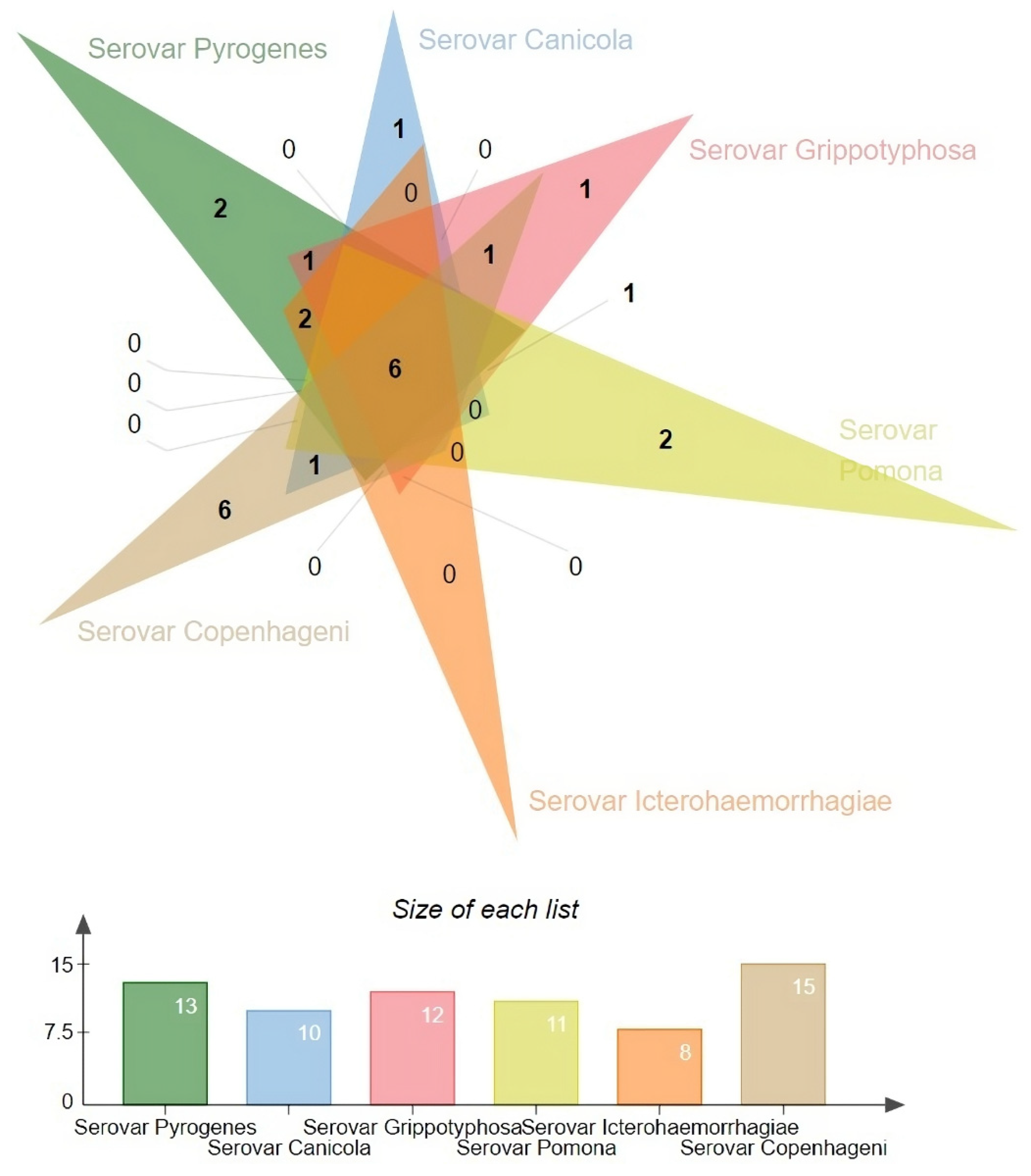

We also analysed the diversity of antiphage systems depending on the serovar (

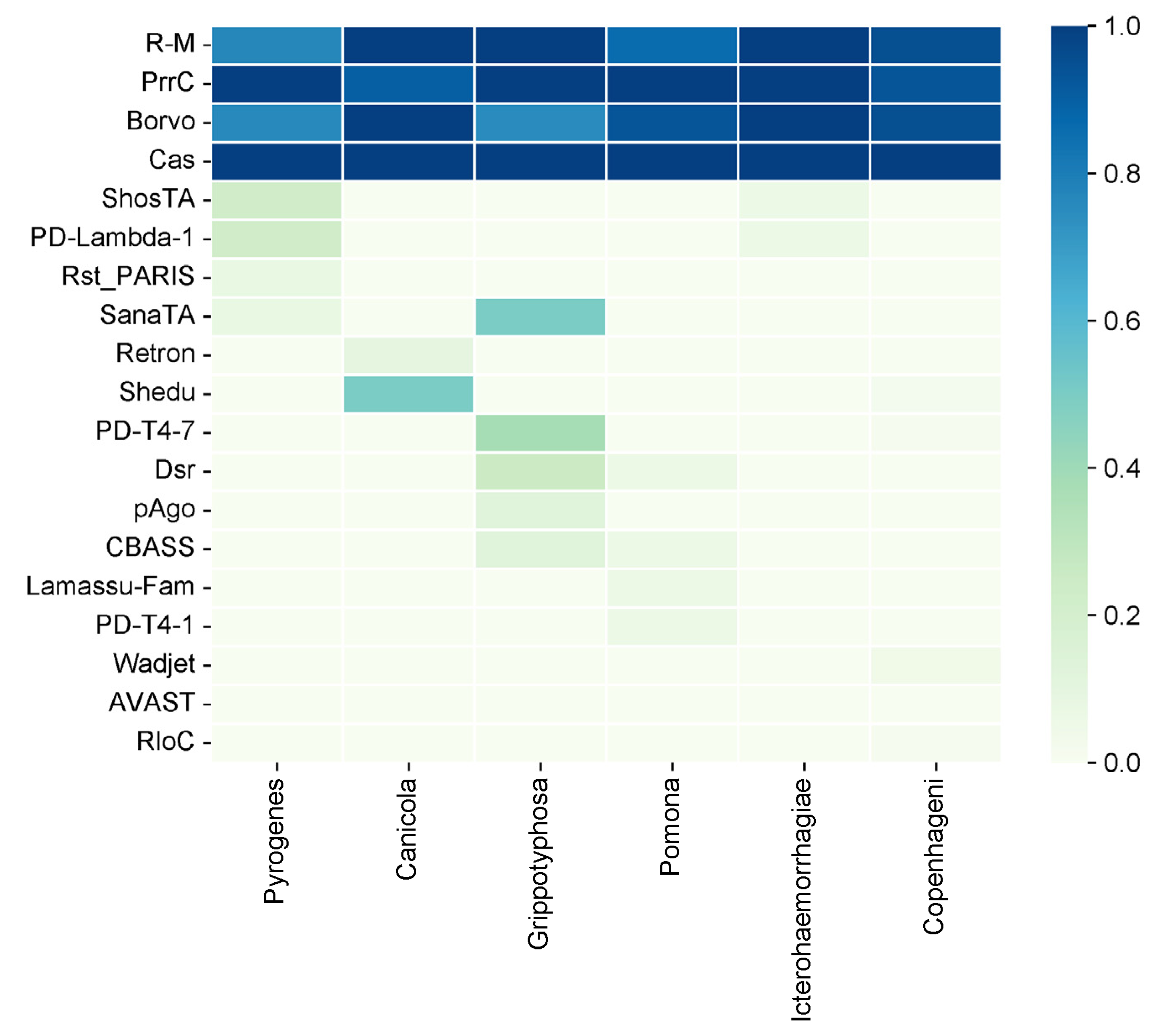

Figure 2). The following six main serovars were considered: Pyrogenes, Canicola, Grippotyphosa, Pomona, Icterohaemorrhagiae, and Copenhageni. Among all the antiphage systems that have been identified, the Cas system is present in all serovars. This shows that it is widely used as a defence mechanism. Similarly, the PrrC system has a high prevalence, being present at 90% or more in all serovars except for Pyrogenes, where it is observed at a 100% frequency

The R-M system, on the other hand, exhibits variable prevalence across different serovars. Ranging from 86.67% in Pomona to 100% in Canicola and Icterohaemorrhagiae. The Borvo system is found at a frequency of 75% in Grippotyphosa and 100% in other serovars (Canicola, Icterohaemorrhagiae).

Several less common antiphage systems, including ShosTA, PD-Lambda-1, Rst_PARIS, and SanaTA, exhibit varying degrees of occurrence among the serovars. ShosTA, for instance, is detected at a 23.08% frequency in Pyrogenes and a 6.25% frequency in Icterohaemorrhagiae. PD-Lambda-1 was detected at 23.08% in Pyrogenes and 6.25% in Icterohaemorrhagiae. Rst_PARIS is present at 7.69% in Pyrogenes. The frequency of SanaTA was 50% in Grippotyphosa (

Figure 3).

Some antiphage systems, such as Retron, Shedu, PD-T4-7, Dsr, pAgo, CBASS, Lamassu-Fam, PD-T4-1, Wadjet, AVAST, and RloC, show lower frequencies and are sometimes only found in certain serovars. For example, Shedu is detected in 50% of Canicola strains and 2.04% of Copenhageni strains. PD-T4-7 is found in 37.5% of Grippotyphosa strains and 1.02% of Copenhageni strains. Dsr is present in 25% of Grippotyphosa strains and 6.67% of Pomona strains. pAgo was detected in 12.5% of the Grippotyphosa strains. CBASS was found in 12.5% of the Grippotyphosa strains and 6.67% of the Pomona strains. Lamassu-Fam was present in 6.67% of the Pomona strains. PD-T4-1 was detected in 6.67% of the Pomona strains. Wadjet was detected in 4.08% of the Copenhageni strains, and RloC was detected in 1.02% of the Copenhageni strains.

4. Discussion

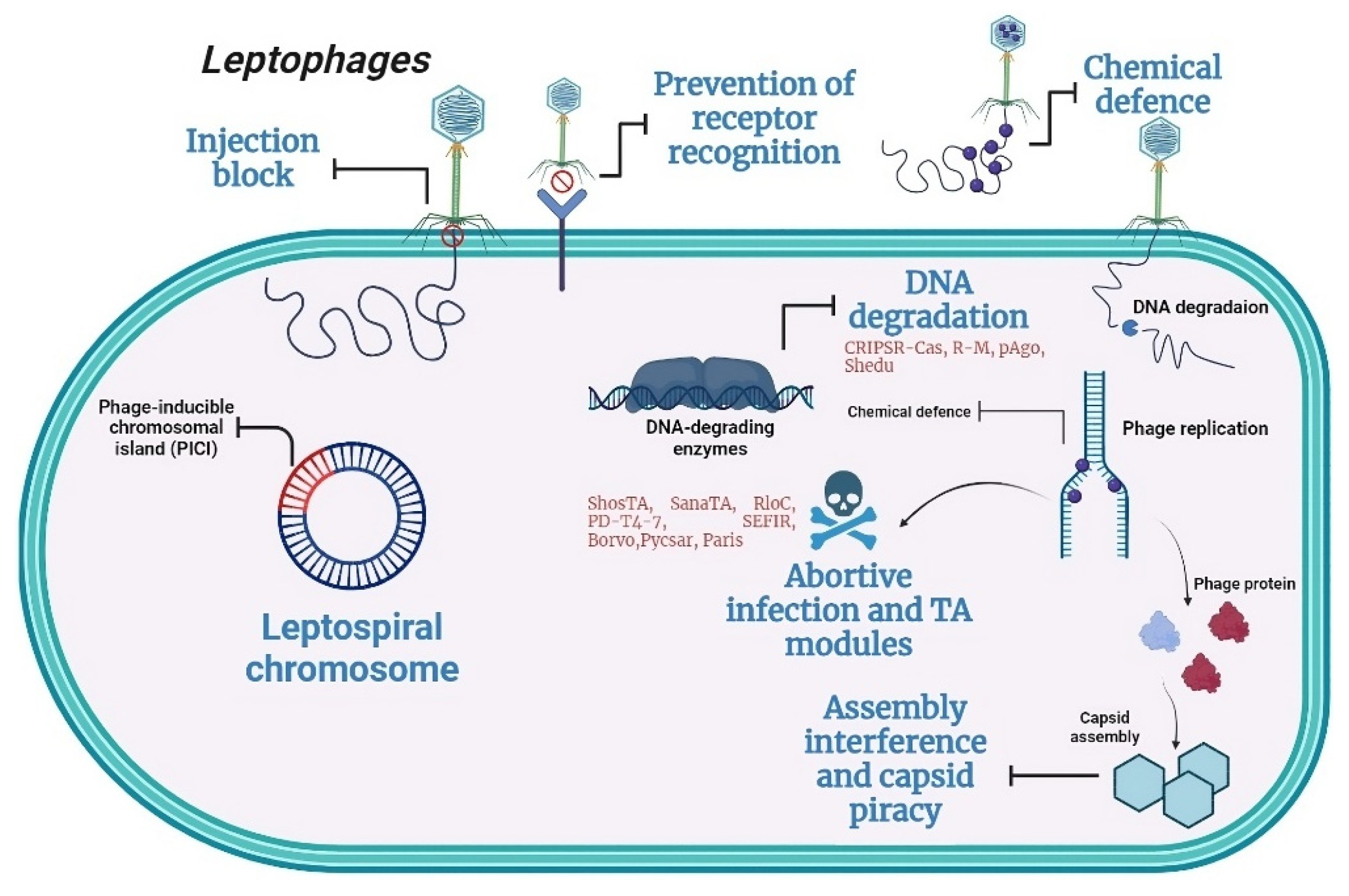

Recent pangenome analysis has unveiled various new systems within bacterial genomes, some of which elucidate novel defense mechanisms at the population level (

Figure 4) [

19]. These bacterial defense systems pose challenges to the effectiveness of phage application. A thorough characterization of phage defense systems, along with their potential drawbacks, is essential for a deeper comprehension of the hurdles in practical phage application and for advancing phage technology. Of the 151 antiphage systems known today, 24 were found in the investigated

Leptospira strains.

Just as antibiotic resistance genes confer bacterial resistance, genes from defense systems can equip host cells with the ability to fend off phages. These defense mechanisms are commonly observed in bacteria. For instance, the restriction-modification (RM) system, initially discovered in the 1950s, is highly prevalent and is present in approximately 90% of diverse bacterial strains.

The functional subunits of R-M systems include methyltransferase (MTase), which transfers a methyl group from the S-adenosyl methionine (SAM) donor molecule to cytosine or adenine in DNA, along with the corresponding restriction endonuclease (REase). Certain systems additionally encode a translocase that employs ATP hydrolysis energy for motor functions. They also feature a specificity subunit containing target recognition domains (TRDs), which define the sequence specificity of the REase and MTase. R-M systems are categorized into four types based on their subunit composition, co-factor requirements, and mode of action.

Type II R-M systems typically recognize palindromic sites, cleaving both DNA strands within or near the nonmethylated sites. Type I R‒M systems modify both strands of bipartite asymmetric DNA sites, requiring interaction between two restriction complexes bound to nonmethylated sites via ATP-dependent DNA looping. Cleavage occurs at nonfixed positions between sites. Type III R-M systems modify only one strand of asymmetric recognition sites, cleaving at a fixed position from one recognition site. This occurs when the restriction complex bound to the nonmethylated site interacts with another complex activated by recognition of a nearby nonmethylated site in the inverted repeat orientation. Type IV R-M systems lack a modification module and cleave DNA after recognizing modified sites. Among the Leptospira strains studied, Type IV R-M (n = 348), Type I R-M (n = 27), and Type II R-M (n = 7) were the most common. Type III R-M was not detected in any of the studied strains.

Unlike DNA modification-based innate immune systems, which rely on predetermined sequence interactions with defense proteins within a phage genome, prokaryotes possess adaptive immune CRISPR‒Cas systems. Decades after R-M, CRISPR‒Cas comprises a CRISPR array and associated cas genes. A CRISPR array consists of short repeated DNA fragments separated by unique spacer sequences, some originating from foreign DNA, with an AT-rich leader region preceding it. Classification is based on effector complex protein composition, yielding two classes, six types, and 33 subtypes. The class 1 (types I, III, and IV) systems use multisubunit effectors, while the class 2 (types II, V, and VI) systems employ single-subunit effectors [

27]. CRISPR–Cas systems are present in less than half of bacteria and in most Archaea [

28]. Type I Cas systems are the most prevalent and are found in 30% of all genomes, followed by type II (8%) and type III (6%) systems in research by Aude Bernheim et al. [

29]. All three genes were distributed across multiple phyla. Types IV, V, and VI are exceedingly rare, have been identified in fewer than 70 genomes, and are primarily confined to specific clades such as Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, and Bacteroidetes.

Only two studies on Leptospira antiphage systems were identified, with both studies exclusively focused on CRISPRs and their subtypes [

17,

30]. The dominant CRISPR types for Leptospira are CRISPR types I and III. In our study, we identified the following types and subtypes of Cas systems: CAS_Class1-Subtype-I-C (n = 399 strains), CAS_Class1-Subtype-I-B (n = 354 strains), and CAS_Cluster (n = 149 strains). Rare types were found, including CAS_Class2-Subtype-V-A in two strains (

Leptospira interrogans serovar Copenhageni str. Fiocruz LV4231 and

Leptospira interrogans serovar Copenhageni str. Fiocruz LV3992), CAS_Class1-Subtype-IV-B in one strain (

Leptospira interrogans str. HAI1536), and CAS_Class1-Subtype-I-E in one strain (

Leptospira interrogans serovar Bataviae str. HAI135).

The third most common antiphage system across

L. interrogans strains was PrrC, an anticodon nuclease that specifically targets tRNALys. This system supports the R-M system by breaking down tRNALys and suppressing phage proliferation [

31,

32,

33]. PrrC is categorized as an abortive infection system due to its disruption of the host translation machinery [

31,

32,

33,

34]

The last of the most frequently encountered defense systems is Borvo, which is a single-gene antiphage system acquired through a combination of bioinformatic prediction and experimental validation [

35]. Borvo is potentially an abortive infection mechanism, but to the best of our knowledge, the precise molecular mechanism underlying Borvo activity remains unidentified [

35,

36]. Regarding the prevalence of this antiphage system, the Borvo gene was found in 177 genomes, accounting for approximately 1% of the total [

22]. Although this antiphage system is relatively rare, we were able to detect it in most of our strains.

The Shedu antiphage system was used for half of the Canicola strains. It consists of a single protein, SduA, which acts as a nuclease with a conserved DUF4263 domain belonging to the PD-(D/E)XK nuclease superfamily. The Shedu protein is proposed to act as a nuclease, and its N-terminal domain inhibits its activation until it is triggered by phage infection [

37]. Its frequency is relatively low, accounting for only 2.3% of other bacteria [

19].

PD-T4-7, found in 37.5% of Grippotyphosa strains, is a single-gene system that functions through an abortive infection mechanism. Among the 22,803 complete RefSeq genomes, PD-T4-7 was detected in 155 (0.68%) [

38]. Dsr, which is also present in 25% of Grippotyphosa strains, has 2 subsystems. In our strains, we found only subsystem II. Among the more than twenty-two thousand complete RefSeq genomes, Dsr was detected in 246 genomes across 162 different species (1.08%).

5. Conclusions

To the best of our knowledge, this study represents the first investigation into the antiphage systems of Leptospira pathogen strains. We identified four major antiphage systems present in the vast majority of strains, namely, Cas, PrrC, Borvo, and R-M. The significant prevalence of the relatively uncommon Borvo antiphage system in the studied strains underscores the importance of further research in this field. Additionally, certain serovar-dependent features were revealed. Retron was found only in serovar Canicola, pAgo was found only in serovar Grippotyphosa, and Wadjet and RloC were found only in serovar Copenhageni.

Supplementary Information: Supplementary File.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.P. and O.K.; methodology, P.P.; software, P.P.; validation, P.P., Y.K. and O.K.; formal analysis, P.P.; investigation, P.P.; data curation, P.P.; writing—original draft preparation, P.P.; writing—review and editing, V.O.; visualization, O.K.; supervision, O.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, and further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bharti AR, Nally JE, Ricaldi JN, Matthias MA, Diaz MM, Lovett MA, et al. Leptospirosis: a zoonotic disease of global importance. J Lancet Infect Dis. 2003;3:757-71. [CrossRef]

- Petakh P, Oksenych V, Kamyshna I, Boisak I, Lyubomirskaya K, Kamyshnyi O. Exploring the complex interplay: gut microbiome, stress, and leptospirosis. 2024;15. [CrossRef]

- Haake DA, Levett PN. Leptospirosis in humans. J Leptospira leptospirosis. 2015:65-97. [CrossRef]

- Adler B, de la Peña Moctezuma A. Leptospira and leptospirosis. Vet Microbiol. 2010;140(3-4):287-96. [CrossRef]

- Petakh P, Rostoka L, Isevych V, Kamyshnyi A. Identifying risk factors and disease severity in leptospirosis: A meta-analysis of clinical predictors. Tropical doctor. 2023;53(4):464-9. [CrossRef]

- Petakh P, Isevych V, Kamyshnyi A, Oksenych V. Weil's Disease-Immunopathogenesis, Multiple Organ Failure, and Potential Role of Gut Microbiota. Biomolecules. 2022;12(12). [CrossRef]

- Petakh P, Isevych V, Mohammed IB, Nykyforuk A, Rostoka L. Leptospirosis: Prognostic Model for Patient Mortality in the Transcarpathian Region, Ukraine. Vector borne and zoonotic diseases (Larchmont, NY). 2022;22(12):584-8. [CrossRef]

- Ramirez J, Guarner F, Bustos Fernandez L, Maruy A, Sdepanian VL, Cohen H. Antibiotics as Major Disruptors of Gut Microbiota. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2020;10:572912. [CrossRef]

- Neuman H, Forsythe P, Uzan A, Avni O, Koren O. Antibiotics in early life: dysbiosis and the damage done. FEMS microbiology reviews. 2018;42(4):489-99. [CrossRef]

- Strati F, Pujolassos M, Burrello C, Giuffrè MR, Lattanzi G, Caprioli F, et al. Antibiotic-associated dysbiosis affects the ability of the gut microbiota to control intestinal inflammation upon fecal microbiota transplantation in experimental colitis models. Microbiome. 2021;9(1):39. [CrossRef]

- Hyman P, Abedon ST. Bacteriophage host range and bacterial resistance. Advances in applied microbiology. 2010;70:217-48. [CrossRef]

- Girons IS, Margarita D, Amouriaux P, Baranton G. First isolation of bacteriophages for a spirochaete: Potential genetic tools for Leptospira. Research in Microbiology. 1990;141(9):1131-8. [CrossRef]

- Kropinski AM, Prangishvili D, Lavigne R. Position paper: the creation of a rational scheme for the nomenclature of viruses of Bacteria and Archaea. Environmental microbiology. 2009;11(11):2775-7. [CrossRef]

- Zhu W, Wang J, Zhu Y, Tang B, Zhang Y, He P, et al. Identification of three extrachromosomal replicons in Leptospira pathogenic strain and development of new shuttle vectors. BMC genomics. 2015;16(1):90. [CrossRef]

- Schiettekatte O, Vincent AT, Malosse C, Lechat P, Chamot-Rooke J, Veyrier FJ, et al. Characterization of LE3 and LE4, the only lytic phages known to infect the spirochete Leptospira. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):11781. [CrossRef]

- Bernheim A, Sorek R. The panimmune system of bacteria: antiviral defence as a community resource. Nature reviews Microbiology. 2020;18(2):113-9. [CrossRef]

- Xiao G, Yi Y, Che R, Zhang Q, Imran M, Khan A, et al. Characterization of CRISPR‒Cas systems in Leptospira reveals potential application of CRISPR in genotyping of Leptospira interrogans. APMIS : acta pathologica, microbiologica, et immunologica Scandinavica. 2019;127(4):202-16. [CrossRef]

- Yuan X, Huang Z, Zhu Z, Zhang J, Wu Q, Xue L, et al. Recent advances in phage defense systems and potential overcoming strategies. Biotechnology advances. 2023;65:108152. [CrossRef]

- Doron S, Melamed S, Ofir G, Leavitt A, Lopatina A, Keren M, et al. Systematic discovery of antiphage defense systems in the microbial pangenome. Science. 2018;359(6379). [CrossRef]

- Makarova KS, Wolf YI, Koonin EV. Comparative genomics of defense systems in archaea and bacteria. Nucleic acids research. 2013;41(8):4360-77. [CrossRef]

- Hochhauser D, Millman A, Sorek R. The defense island repertoire of the Escherichia coli pangenome. PLoS genetics. 2023;19(4):e1010694. [CrossRef]

- [Available from: https://defensefinder.mdmlab.fr/wiki/defense-systems/borvo#ref-10.1016/j.cell.2023.02.029. [CrossRef]

- Abby SS, Néron B, Ménager H, Touchon M, Rocha EPC. MacSyFinder: A Program to Mine Genomes for Molecular Systems with an Application to CRISPR‒Cas Systems. PLOS ONE. 2014;9(10):e110726. [CrossRef]

- Néron B, Denise R, Coluzzi C, Touchon M, Rocha EPC, Abby SS. MacSyFinder v2: Improved modelling and search engine to identify molecular systems in genomes. 2022:2022.09.02.506364. [CrossRef]

- Tang D, Chen M, Huang X, Zhang G, Zeng L, Zhang G, et al. SRplot: A free online platform for data visualization and graphing. PLOS ONE. 2023;18(11):e0294236. [CrossRef]

- Bardou P, Mariette J, Escudié F, Djemiel C, Klopp C. jvenn: an interactive Venn diagram viewer. BMC Bioinformatics. 2014;15(1):293. [CrossRef]

- Nussenzweig PM, Marraffini LA. Molecular Mechanisms of CRISPR‒Cas Immunity in Bacteria. 2020;54(1):93-120. [CrossRef]

- Makarova KS, Wolf YI, Alkhnbashi OS, Costa F, Shah SA, Saunders SJ, et al. An updated evolutionary classification of CRISPR‒Cas systems. Nature reviews Microbiology. 2015;13(11):722-36. [CrossRef]

- Bernheim A, Bikard D, Touchon M, Rocha EPC. Atypical organizations and epistatic interactions of CRISPRs and cas clusters in genomes and their mobile genetic elements. Nucleic acids research. 2019;48(2):748-60. [CrossRef]

- Senavirathna I, Jayasundara D, Warnasekara J, Matthias MA, Vinetz JM, Agampodi S. Complete genome sequences of twelve strains of Leptospira interrogans isolated from humans in Sri Lanka. Infection, Genetics and Evolution. 2023;113:105462. [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann G, David M, Borasio GD, Teichmann A, Paz A, Amitsur M, et al. Phage and host genetic determinants of the specific anticodon loop cleavages in bacteriophage T4-infected Escherichia coli CTr5X. Journal of molecular biology. 1986;188(1):15-22. [CrossRef]

- Sirotkin K, Cooley W, Runnels J, Snyder LR. A role in true-late gene expression for the T4 bacteriophage 5′ polynucleotide kinase 3′ phosphatase. Journal of molecular biology. 1978;123(2):221-33. [CrossRef]

- Huiting E, Bondy-Denomy J. Defining the expanding mechanisms of phage-mediated activation of bacterial immunity. Current opinion in microbiology. 2023;74:102325. [CrossRef]

- Penner M, Morad I, Snyder L, Kaufmann G. Phage T4-coded Stp: Double-Edged Effector of Coupled DNA and tRNA-Restriction Systems. Journal of molecular biology. 1995;249(5):857-68. [CrossRef]

- Millman A, Melamed S, Leavitt A, Doron S, Bernheim A, Hör J, et al. An expanded arsenal of immune systems that protect bacteria from phages. Cell Host & Microbe. 2022;30(11):1556-69.e5. [CrossRef]

- Stokar-Avihail A, Fedorenko T, Hör J, Garb J, Leavitt A, Millman A, et al. Discovery of phage determinants that confer sensitivity to bacterial immune systems. Cell. 2023;186(9):1863-76.e16. [CrossRef]

- Gu Y, Li H, Deep A, Enustun E, Zhang D, Corbett KD. Bacterial Shedu immune nucleases share a common enzymatic core regulated by diverse sensor domains. 2023:2023.08.10.552793. [CrossRef]

- Vassallo CN, Doering CR, Littlehale ML, Teodoro GIC, Laub MT. A functional selection reveals previously undetected anti-phage defence systems in the E. coli pangenome. Nature microbiology. 2022;7(10):1568-79. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).