1. Introduction

Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) have started to be used in various fields in recent years due to their versatility and ease of operation, such as national ecological protection, aerial photography, mapping, mineral resources exploration, disaster surveillance, traffic patrols, and power line patrols [

1]. However, the increasing demand for spectrum conflicts with the limited spectrum resources, UAVs also face a spectrum shortage problem. And yet, in another respect, research by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) has proven that the scarcity of spectrum resources is largely due to its low utilization by licensed primary users (PUs) in the time or spatial domains. In this context, cognitive radio (CR) is proposed, in which by means of spectrum sensing technology, SUs are allowed to opportunistically access licensed spectrum, i.e., SUs are allowed to access the channel without causing harmful interference to the PU if the PU is detected as inactive in the channel. Otherwise, SUs are not allowed to access it [

2,

3]. But the single-user spectrum sensing is not reliable, and its performance is prone to be affected by the unfavorable channel condition of wireless transmission, such as multipath fading, hidden terminal problems, shadowing and receiver uncertainty problem, and so forth, etc. [

4]. Therefore, cooperative spectrum sensing (CSS) has been proposed to overcome this problem and improve the sensing performance, i.e., each SU individually submits own sensing result about the PU signal to a fusion center (FC), and then the FC makes the final decision by a specific fusion rule about the PU state.

In this regard, integrating the CR technology into UAV communication is beneficial for solving the spectrum usage demand of UAVs. Nevertheless, based on the cooperative mode among multiple SUs, CSS among multiple UAVs has two limitations: (a) the flexible location of UAVs poses challenges in swiftly implementing cooperative modes [

5]; (b) the cooperative mode among multiple UAVs requires a relatively low overhead (minimal additional communication or computational resources required between the FC and each UAV to enable and maintain the cooperative mode among multiple UAVs) between the FC and UAVs [

6]. Moreover, although the original intention of CSS aims to improve the sensing accuracy, considering the gradual popularity of UAV communication, in large-scale cognitive UAV networks (CUAVNs), both the performance and efficiency of CSS need to be further considered in order to provide more available spectrum for UAVs [

7].

1.1. Related Works and Motivation

In fact, in order to provide a better quality of service (QoS) for UAVs, many efforts have been devoted to studying CUAVN related to the CSS performance and efficiency [

8].

In [

9], J. Zhang et al. developed a CSS framework among mini-sensing slots for CUAVNs under flexible sensing delay constraints. In [

10], J. Wu et al. proposed a multi-slot CSS among multiple mini-slots of a UAV sensing node and analyzed its performance and cost/benefit. A multi-UAV spectrum sensing algorithm based on group cooperation was proposed by Z. Liu in [

11], which improves the detection probability based on the combination of feature extraction and clustering algorithm. Based on [

12], to cope with the problem of low energy efficiency (EE) in CUAVNs, J. Xiong et al. introduced the normalized spectrum sensing algorithm into multi-UAV CUAVN to investigate EE based on CSS. In [

13], M. S. Hosen et al. used fuzzy logic algorithm to solve the channel allocation problem in a CUAVN. A constrained optimization problem was proposed to maximize the residual energy subject to the constraint of secondary secrecy outage in [

14]. Besides, H. Hu et al. optimized spectrum efficiency (SE) and EE for CUAVNs based on location information in [

15]. In [

16], the virtual CSS optimization problem was taken into consideration in a UAV-based interweave CR system. The optimization problem of sensing radian and the real-time trajectory of UAV was proposed in [

17] to improve SE. In [

18], X. Liu et al. proposed virtual CSS to maximize effective throughput by jointly optimizing the local sensing arc and the number of sensing time slots. Not limited to 2D spectrum space, J. Zhang et al. in [

19] proposed a multi-slot mode within a UAV to improve SE and EE and reduce energy consumption (EC). Similar to [

19], F. Shen et al. investigated spatial-temporal spectrum sensing problem at UAV nodes. In [

21], Y. Pan et al. maximized EE problem to jointly optimize the sensing time and secondary transmit power in UAV-based coverage of CR networks. While most of the literature mentioned above has focused on studying the EE aspects of CSS in UAVs, there has been a noticeable oversight regarding the issue of cooperative efficiency between the FC and UAVs. Additionally, it is worth noting that the assumed PU scenario in these studies is relatively simplistic. Hence, there is an urgent need to address these gaps and provide a more comprehensive analysis that encompasses the cooperative efficiency between the FC and UAVs, while considering more realistic and complex PU scenarios.

With the continuous evolution of machine learning, the proper application of machine learning algorithms in the field of CUAVNs has become more crucial in recent years, allowing them to learn and adapt to their surroundings effectively, so as to obtain the best QoS and EE. In [

22], considering the limitations of the long short-term memory algorithm in terms of the UAV’s EC, Z. Luo and X. Wang proposed a spectrum sensing algorithm based on the gated recurrent unit, which reduces EC by 1/4 compared to long short-term memory and can be applied to multiple UAV scenarios. In [

23], R. Nie et al. presented a clustering-based distributed CSS scheme, which significantly enhances the spectrum detection performance of CUAVNs compared to the non-clustered distributed CSS scheme. For the spectrum-sensing-data-falsification attack, a support vector machine (SVM)-based scheme was proposed in [

24] to analyze SU behavior from multiple rounds of energy value recording to obtain classification accuracy. In [

25], N. Gu et al. presented a hybrid boosted tree algorithm which combines differential evolution and the boosted tree algorithm to mitigate the negative impact of malicious users on CSS. What’s more, H. Luan et al. proposed a machine learning algorithm to provide real-time per frame training and decision-based CSS. Apart from that, the performance comparison of multiple supervised machine learning classifiers was present in [

26]. However, different voting rules can affect the number of reporting samples required to make the global decision, thus affecting the performance metric, such as throughput, EE, etc. In [

27], an energy-efficient sequential decision fusion approach based on K-out-of-N rule was proposed. J. Liang et al. analyzed the impact of different voting rules on the throughput and EC of the system in [

28]. However, the aforementioned research has made contributions to the integration of UAVs and CR technology and have employed machine learning algorithms to address QoS and EE challenges, it is significant to note that these investigations predominantly focus on a single PU scenario. Moreover, there has been a limited amount of research conducted to explore the influence of different voting rules on cooperative performance and efficiency, including aspects such as global detection performance, sample size, and EE. Therefore, there is a significant demand for extensive investigation in this domain to comprehensively comprehend the consequences and advantages of different voting rules concerning cooperative performance and efficiency in CUAVN.

1.2. Our Contributions

In accordance with the studies mentioned above, it can be seen that the performance and efficiency of CSS still pose significant research challenges in CUAVNs. Additionally, a variety of complex PU scenarios in practice are also suitable for different voting rules. Hence, we have selected the detection performance (i.e., the global false alarm probability and the detection probability), the sample size, and EE as the performance metric of a CUAVN. Further, considering the disadvantages of the simple PU activity and the traditional cooperative mode among multiple UAVs, this paper makes three major contributions as follows.

To provide a comprehensive description of PU activity, we consider three scenarios that encompass various situations of channel usage. To overcome unfavorable factors of the cooperative mode among multiple UAVs, we further propose the cooperative mode among multiple mini-slots with a single UAV to guarantee the cooperative gain and improve the cooperative efficiency.

Based on the proposed PU scenario and cooperative mode, we conduct a detailed analysis of the advantages and disadvantages of voting rules including conventional voting rule (CVR), sequential voting rule (SVR), and sequential 1 (S1) in different scenarios. To further improve the cooperative efficiency, we utilize the sequential idea and differential mechanism to develop a differential sequential 1 (DS1), with the aim of improving the cooperative efficiency without affecting the detection performance. The simulation results also demonstrate the superiority of our method, primarily attributed to the substantial advantage of DS1 in terms of sample size.

In order to realize the optimal selection under different PU scenarios, we introduce SVM to classify the proposed DS1 and other voting rules according to the global false alarm probability and the detection probability, the sample size, and EE. On the basis of SVM dynamic selection, the numerical results demonstrate that the proposed DS1 is consistently superior in the CSS performance and efficiency. Moreover, the dynamic selection framework offers the potential for improved voting rules and the ability to handle more complex scenarios in the future.

1.3. Organization

The rest of this paper is as follows. In

Section 2, a cooperation mode among multiple mini-slots in a CUAVN is established.

Section 3 makes a preliminary analysis on CVR, SVR and S1 and on basis of it, further proposes DS1 for a high-efficient CSS and evaluates its performance and efficiency. A SVM dynamic selection is proposed to choose the optimal voting rule in various environments in

Section 4. The simulation results in

Section 5 verify the proposed DS1. Eventually, Section6 draws a conclusion about this paper.

2. System Model

In this section, following a circular flight trajectory, we propose a CUAVN model including a PU and a UAV. On the basis of such a network model, we further develop a local spectrum sensing (LSS) model based on the energy detection and a CSS model among multiple mini-slots according to the periodic spectrum sensing frame structure.

2.1. Network Model

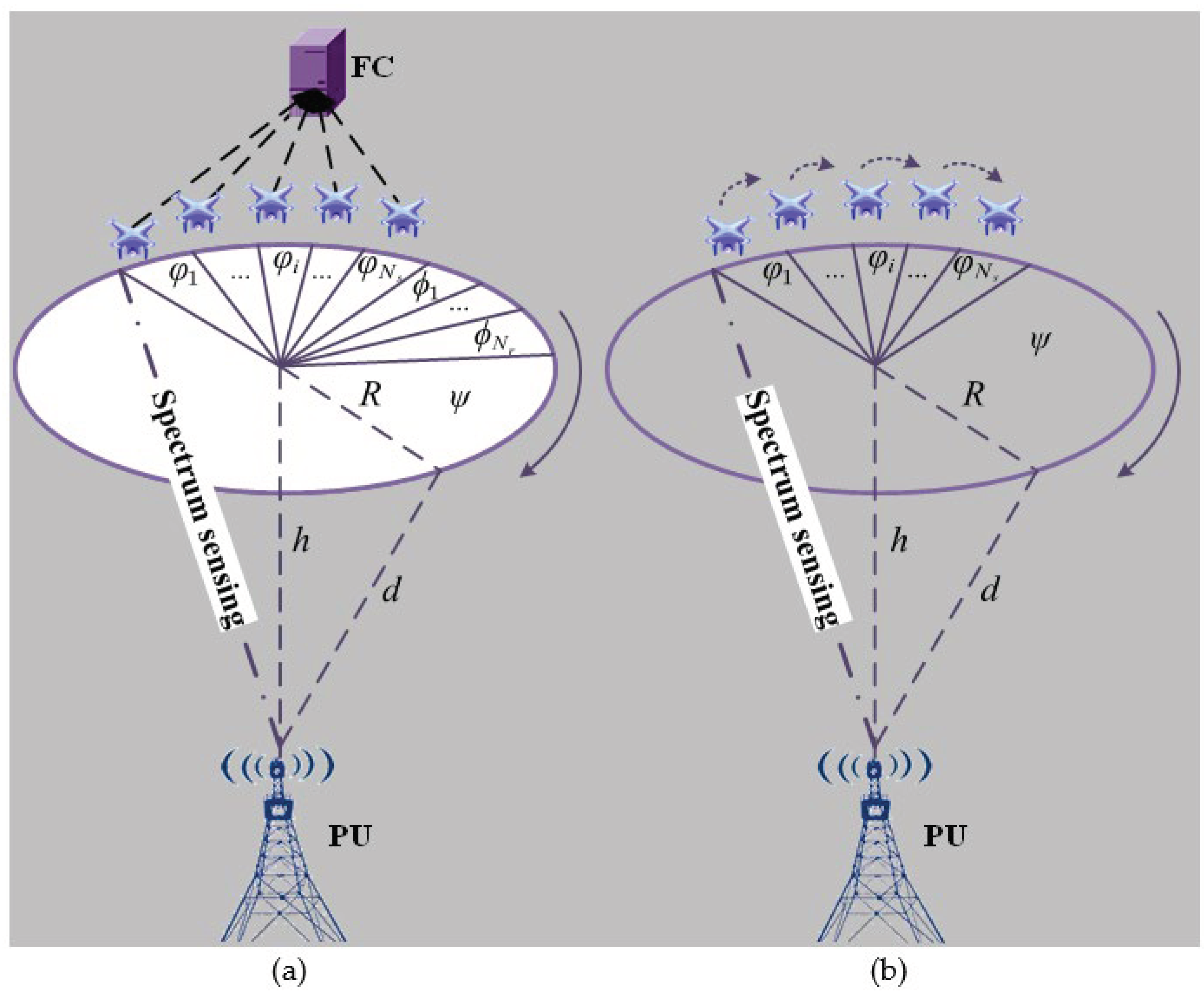

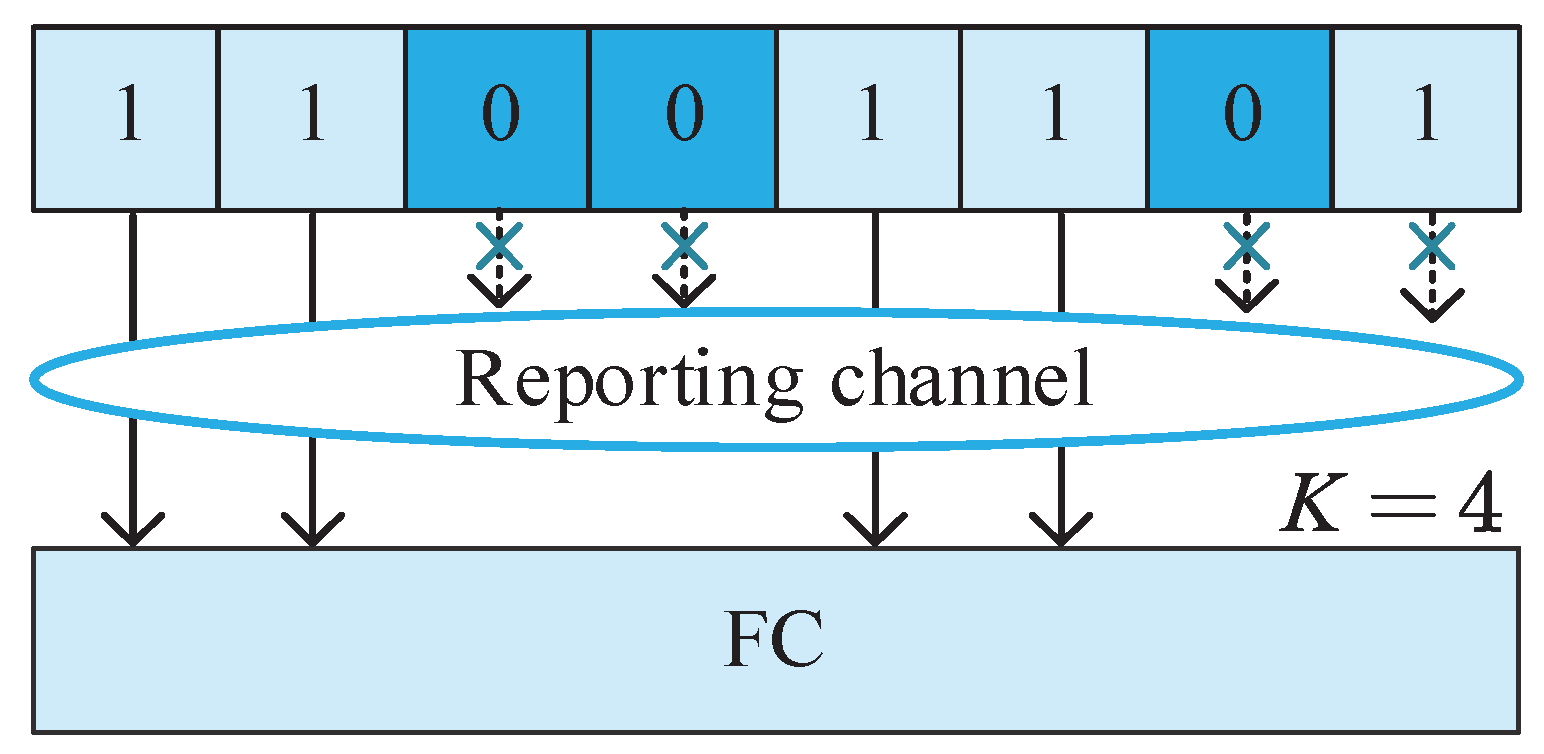

In order to achieve the available spectrum resources and not cause harmful interference to the PU’s communication, the CSS paradigm is applied for CUAVNs to detect the PU signal by spatially located UAVs. Before describing the CSS model among multiple mini-slots within the single UAV, we make a brief presentation of the traditional CSS model among multiple UAVs. As illustrated in

Figure 1(a), the CUAVN model consisting of a PU and multiple UAVs in a traditional cooperative model. Assuming that the UAV follows a circular flight trajectory around the PU from a vertical perspective, the flight radius is

(as shown in

Table 1) and the height is

, the spectrum sensing distance of

radius is

(as shown in

Table 1) and the height is

, the spectrum sensing distance of the UAV is

.

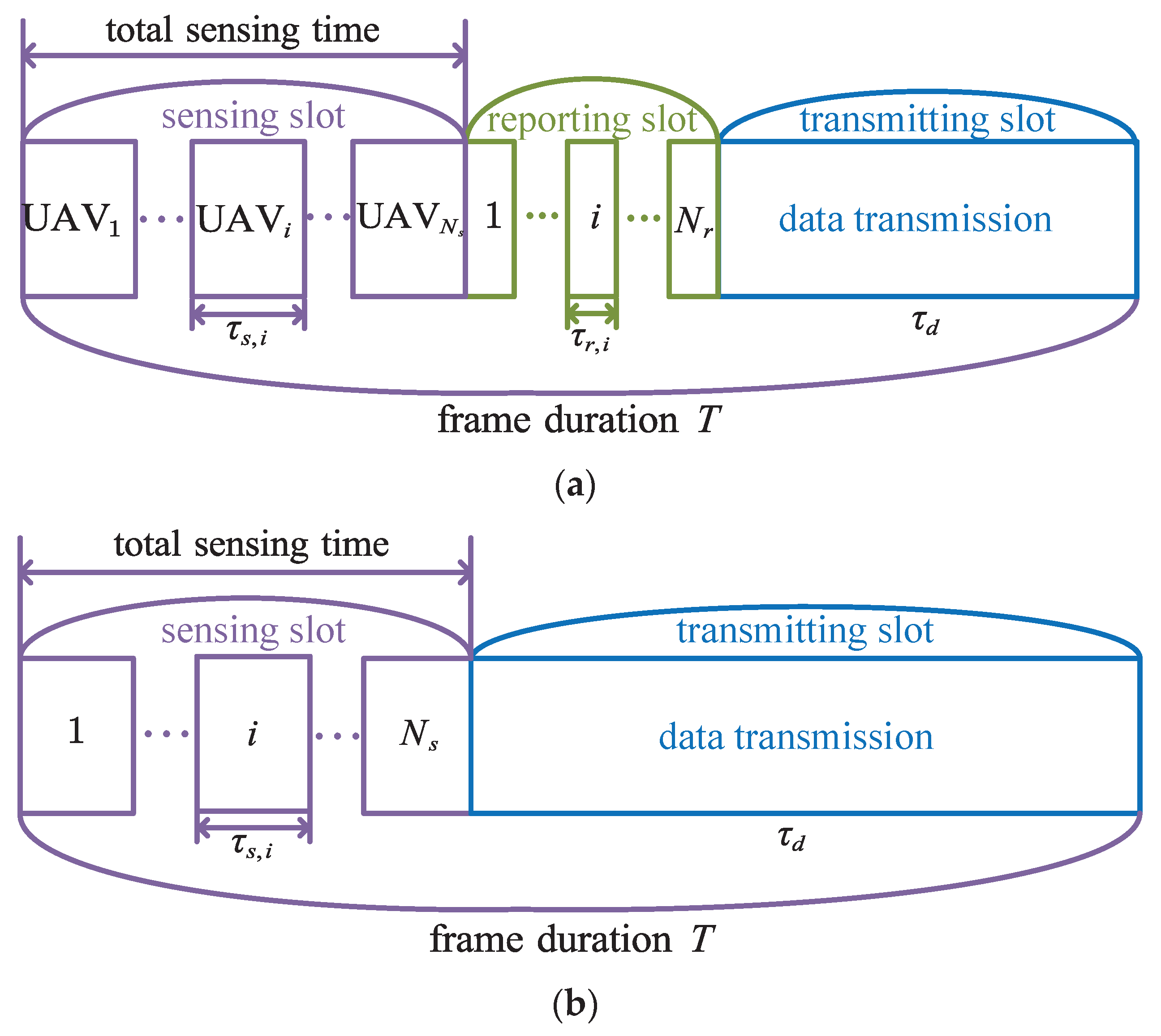

In a periodic spectrum sensing frame structure of CUAVNs, a fixed frame is divided into a sensing slot, a reporting slot, and a data transmission slot. In a cooperative model among multiple UAVs, as depicted in

Figure 2(a), the

-th UAV utilizes the LSS technology detects the PU signal within the sensing time

, subsequently, the UAV submits individual sensing result within the reporting time

to the FC through the common reporting channel at the reporting slot. Finally, the FC makes a global decision about the PU status via a specific rule in accordance with the received sensing results, which decides whether UAVs are allowed to access the channel or not. All UAVs are not allowed to access the channel to protect the PU from the harmful interference and then continue on the next sensing frame if the global decision is declared as 1, otherwise, UAVs are allowed to access the channel within

at the data transmission slot because of the PU’s absence. Correspondingly, the whole flight radian at each frame can be grouped into

,…,

, …,

(where

represents the flight radian of the

-th UAV at the sensing slot and

is the number of UAVs involved in the cooperative sensing, the total number of UAVs is

, and

),

,…,

, …,

(where

represents the flight radian of the

-th UAV at the reporting slot,

is the number of samples required at the FC, and

), and

is the flight radian of the UAV at the data transmission slot.

2.2. Local Performance

According to the CUVAN model, we further conduct an evaluation of the LSS performance at the UAV. The energy detection is commonly adopted as the LSS scheme because of its low computational and operational complexity [

29]. The spectrum sensing problem is usually regarded as a binary hypothesis test in energy detection scheme, i.e., the hypotheses

and

represent the the PU’s absence and presence, respectively, then the received signal at the

-th UAV can be presented as [

20]

where

denotes the circularly symmetric complex Gaussian (CSCG) noise with mean 0 and variance

,

is the complex-valued phase shift keying (PSK) signal transmitted by the PU,

and

are independent,

is the attenuated received PU signal with a distance

from the PU.

On the basis of above assumptions about the PU signal and noise model, we denote

as the transmitting power of the PU signal, the received signal at the

-th UAV is presented as

where

denotes the carrier frequency,

is the light speed,

and

are line of sight (LOS) and non-line of sight (NLOS) link occurrence probabilities, which depend on

,

and

[

26], where the parameters

,

are determined by the environment,

is the elevation angle of the UAV,

and

are the free space propagation loss [

20].

The energy statistic of the

-th UAV is described as

where

is the number of samplings. Considering a large

, according to central limit theorem,

is regarded as a random variable that follows a Gaussian distribution, i.e.,

where

,

indicates the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). In LSS, the local measured energy is compared to a pre-determining

for making a local binary decision, the local false alarm and the detection probabilities are given by

where

is the complementary distribution function of the standard Gaussian.

2.3. Cooperative Mode Among Multiple Mini-Slots

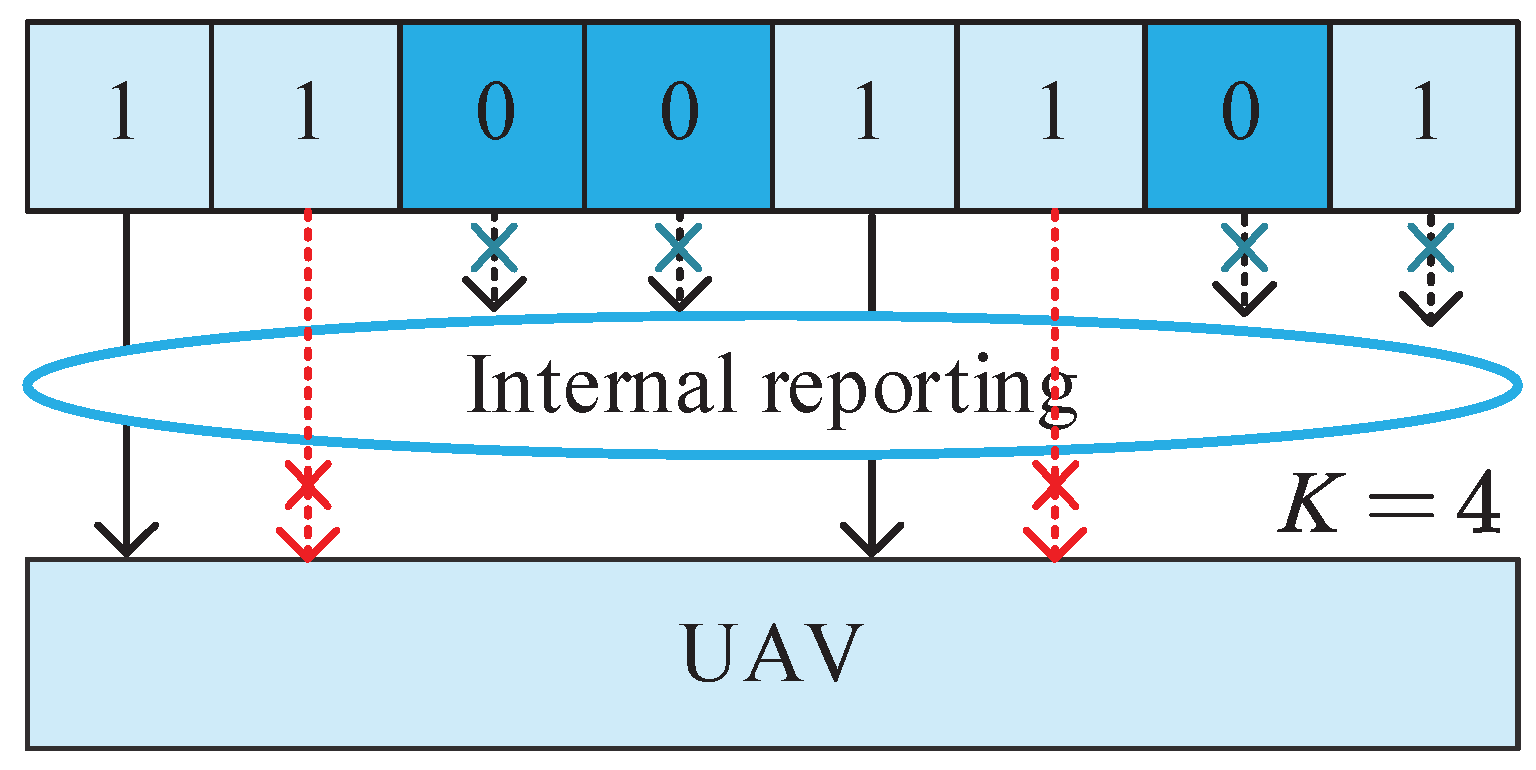

Based on the flight trajectory and frame structure of the traditional cooperative mode among multiple UAVs, it is evident that the cooperative efficiency is not good enough. This is particularly true in scenarios involving fixed-sample-size voting rules or large-scale CUAVNs, where the communication overhead is relatively large. For example, all UAVs are required to collaborate in spectrum sensing within the voting rule and the FC also needs to receive all local decision samples from UAVs, that is, . As a result, in a fixed frame duration , the more UAVs participate in collaboration (which can improve the CSS performance of collaborative spectrum sensing), increasing the number of generated samples leads to a decrease in the achievable throughput of CUAVNs, i.e., the data transmission duration is lower. Additionally, the flexible location of UAVs presents a challenge in promptly implementing CSS.

Motivated by above analyses on the cooperative mode among multiple UAVs, we take the cooperative mode among multiple mini-slots into consideration in the circular flight trajectory. In details, there is only an UAV in the cooperative mode among multiple mini-slots, of which the total sensing time consists of

mini-slots. That is to say, the cooperative paradigm has evolved from external cooperative mode among multiple UAVs (each UAV occupies a sensing time slot and generates a local decision) to internal cooperative mode among multiple mini-slots within a single UAV (the same UAV generates a local decision in multiple mini-slots), as illustrated in

Figure 1(a) and

Figure 2(a). Undoubtedly, the advantage of this mode is that the UAV nevermore need to submit local decisions to the FC via the reporting channel (which increases communication overhead and cannot guarantee the security of spectrum sensing data transmission), while not reducing cooperative gain.

3. Voting Rule Based on DS1 for CSS

In this section, we conduct a preliminary introduction of CVR, SVR, and S1. Inspired by the performance and efficiency exhibited in CSS, we take advantage of the sequential idea and differential mechanism to propose DS1 based on voting rule, aiming to further reduce the number of samples and improve EE.

3.1. Preliminary Analysis

Based on the CUAVN model and the proposed cooperative mode among multiple mini-slots, the UAV utilizes the decision sample at each mini-slot to make a global decision about the PU state according to the fusion rule. In fact, there are various fusion rules being applied for CSS, i.e., voting rule (a.k.a.

-out-of-

rule, namely, more than

decision samples demonstrate the presence of the PU,

is accepted, otherwise

is accepted), Neyman-Pearson, Bayesian detection, sequential detection, etc. Since the voting rule has a low implementation complexity and requires no deterministic knowledge of the PU signal, considerable effort has been dedicated to enhancing its efficiency [

30]. Now, we make a brief presentation of CVR, SVR, and S1 in the cooperation mode among multiple UAVs.

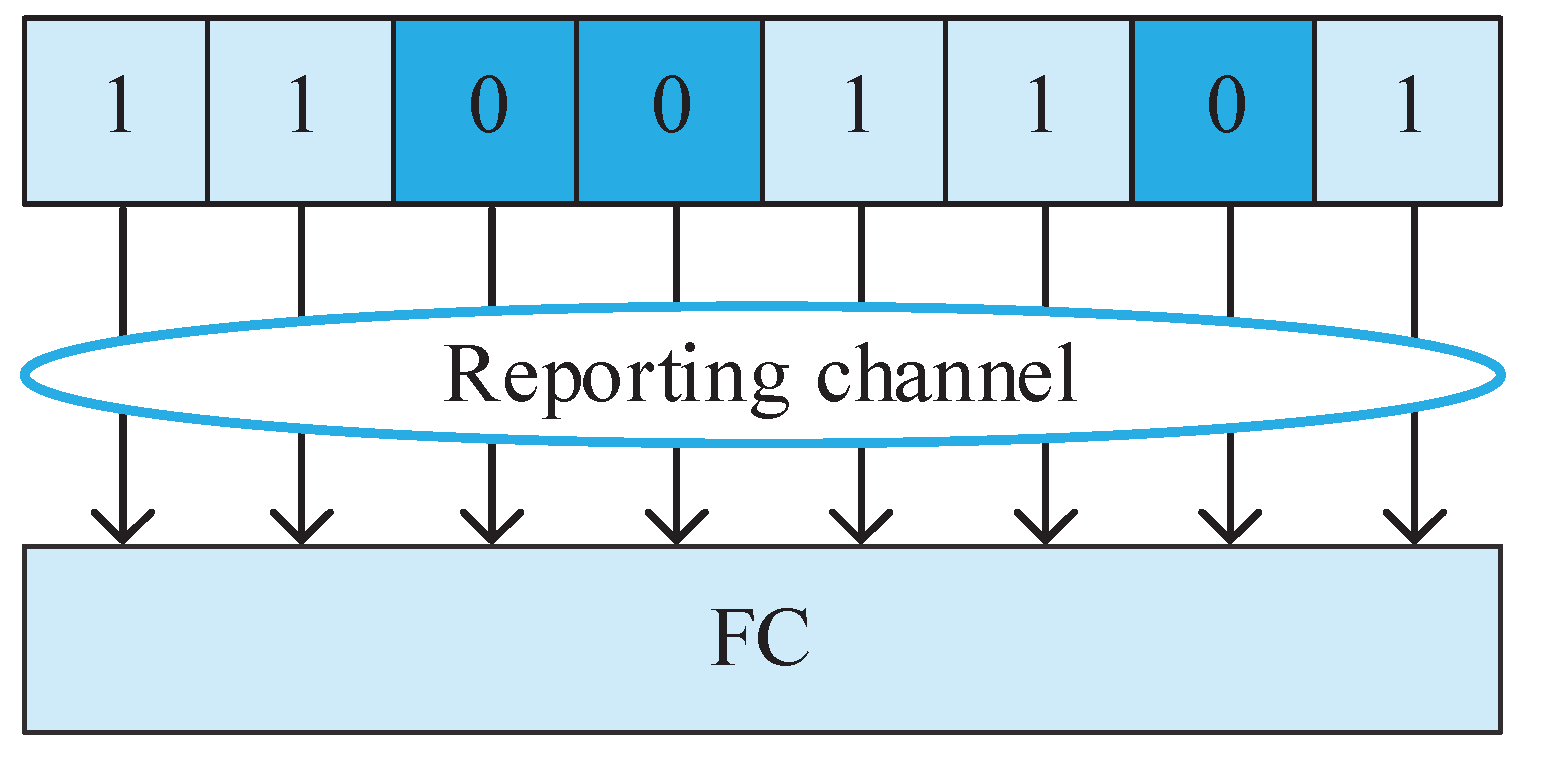

3.1.1. CVR

In the cooperative mode among multiple UAVs using the CVR, all

samples from

UAVs are required to be transmitted to the FC via the reporting channel. The FC then makes the global decision, as depicted in

Figure 3. In this scenario, the sample size required at the FC remains fixed, meaning

.

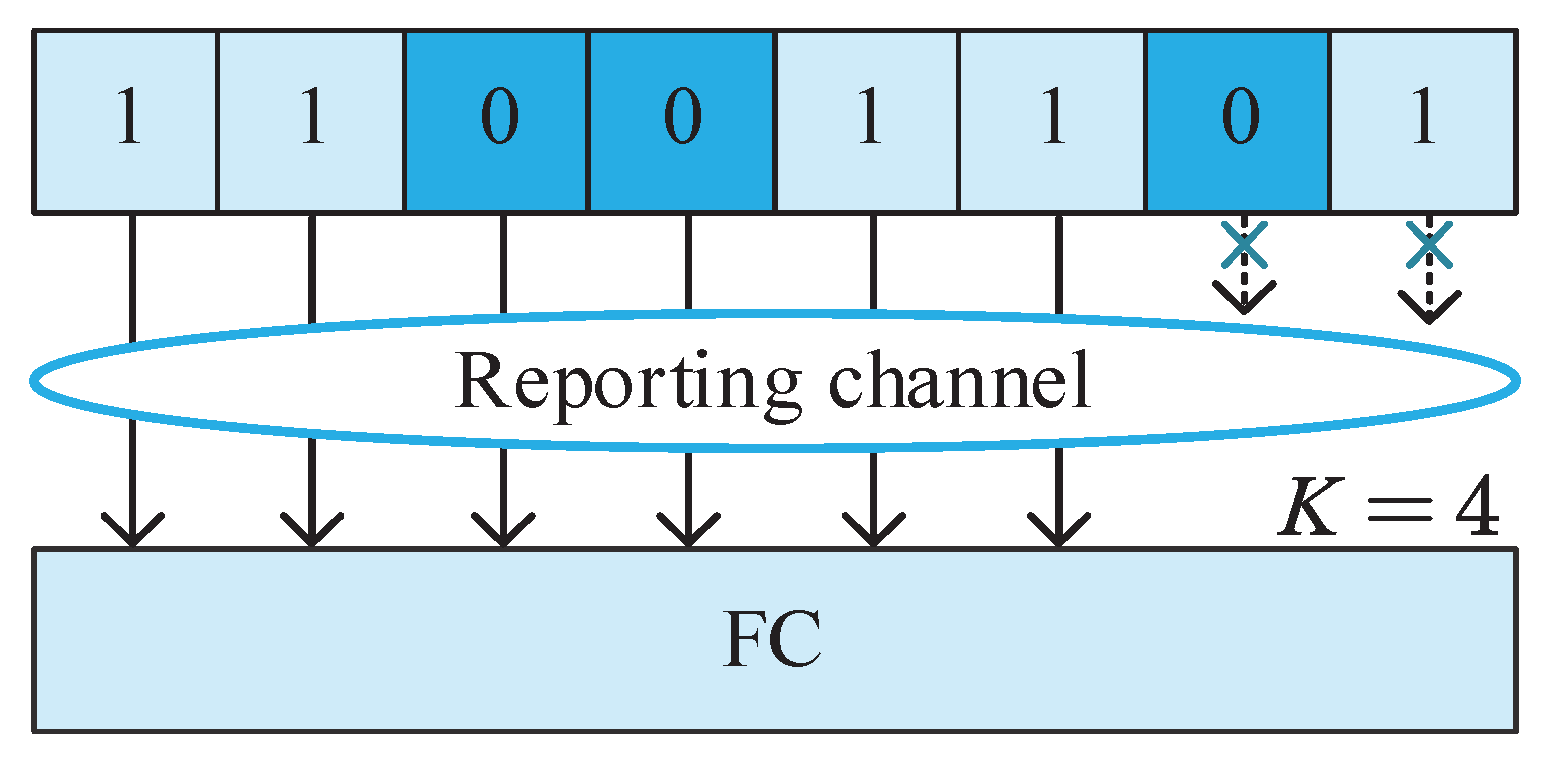

3.1.2. SVR

Contrary to CVR, SVR takes advantage of the sequential detection to accept the samples from UAVs at the FC. According to the decision condition

of the voting rule, when the FC receives

1s (the number of decision samples of 1 is

) or

0s (the number of decision samples of 0 is

), the global decision about the PU state can be naturally decided as 1 or 0. Sequentially, the remaining samples are not required to be submitted, in other words,

and

, as shown in

Figure 4. To be specific, the decision condition for the SVR aligns with that of the CVR. However, the advantage of SVR lies in its ability to reduce the number of samples required for CSS without compromising CSS performance.

3.1.3. S1

On the basis of SVR, the decision sample 1 is allowed to be submitted but 0 is not allowed, as shown in

Figure 5. When the sequentially cumulative number of 1s exceeds

, the FC declares the global decision as 1, similar to SVR, the remaining samples 1s are not required to be submitted. When all

samples are submitted to the FC, the cumulative number of 1s still does not exceed

, the global decision is 0 at the FC. It should be noted that the efficiency of S1 is higher than that of SVR when the usage of the PU channel is lower.

3.2. DS1

According to above description, the consideration of the sequential idea and the usage of the PU channel is beneficial for CSS to improve the efficiency in the voting rule, but in a large CUAVN, there is still room for the efficiency improvement. Therefore, we integrate the differential mechanism into the proposed cooperation mode among multiple mini-slots on the basis of S1 to further propose DS1.

Since there is no longer a need to submit the sample to the FC in the proposed cooperation mode, the UAV itself can process spectrum sensing information very conveniently and quickly, i.e., it is straightforward for the UAV to determine whether the decision samples from the front and the back mini-slots are consistent. The phenomenon of whether the decision samples of the front and back mini-slots are consistent is called “differential”. Hence, we apply such a differential mechanism for the sample reduction. As shown in

Figure 6, we take

and

for example to further explain the differential mechanism. When the first sample is 1, then the second sample is no longer needed because it is also 1. Moreover, the third and fourth samples are not needed either according to S1. Because the fifth decision sample 1 is different from the fourth decision sample 1, the UAV needs to process, while the sixth one is 1 and not required. Therefore, only two decision samples are needed to achieve the decision condition of

. This combination of this differential mechanism and the sequential idea can greatly reduce the sample size required for making final decisions without disturbing the detection performance, resulting in higher efficiency compared to the previous three voting rules.

3.3. Performance Evaluation and Analysis

For the simplicity of measuring the performance and efficiency of four voting rules mentioned above, we assume that the local performance and the sensing/reporting time is the same in each UAV/mini-slot, i.e., .

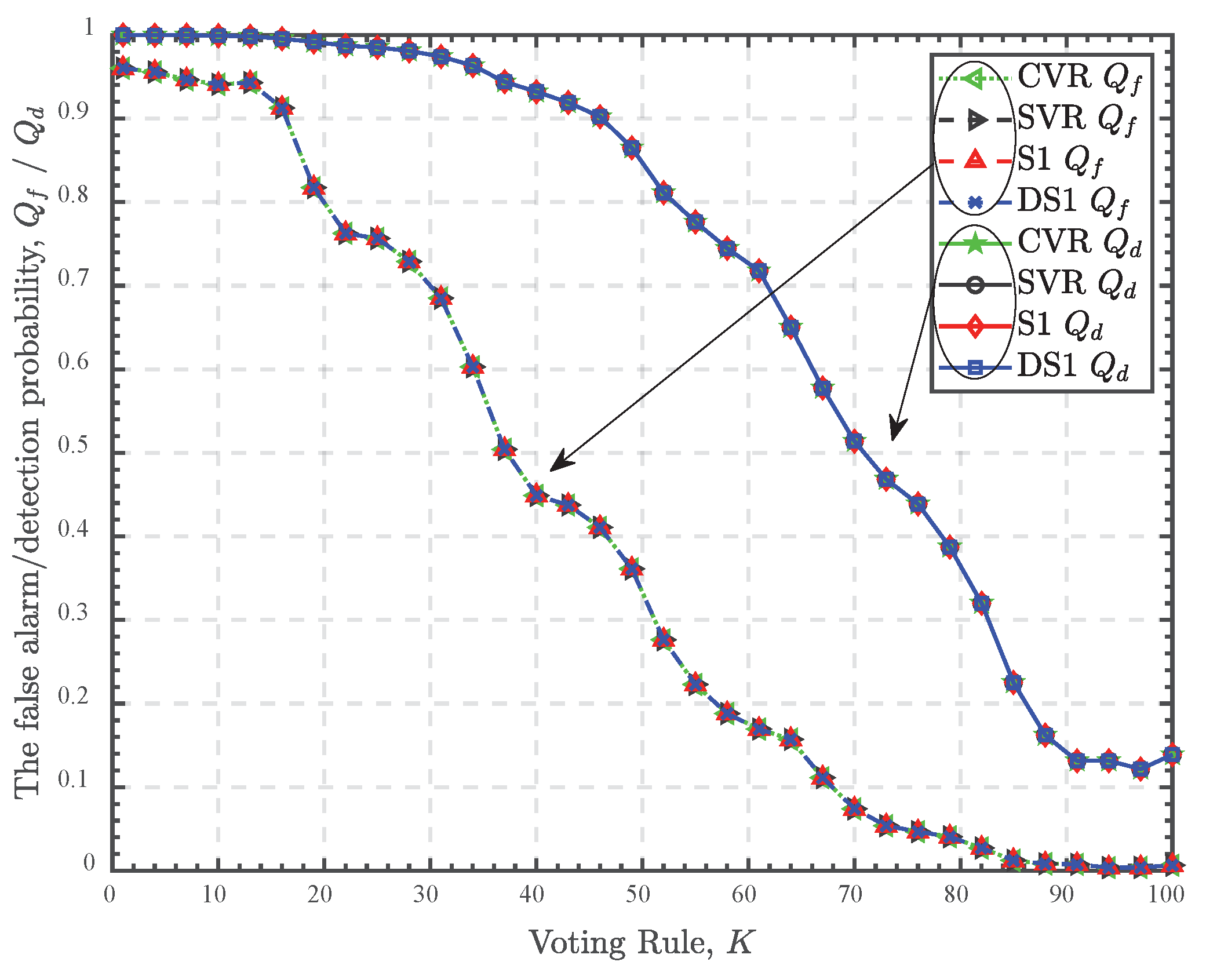

3.3.1. Detection Performance

According to the decision condition

, the global false alarm and detection probabilities is expressed as [

27]

However, regardless of the voting rule, the decision condition

remains unchanged, and there is no loss or falsifying of the diverse decision samples. It is only through changing the processing method to improve the efficiency of sample processing or transmission. Hence, these voting rules theoretically have the same global detection performance. Additional details of the mathematical proof can be found in [

27,

30].

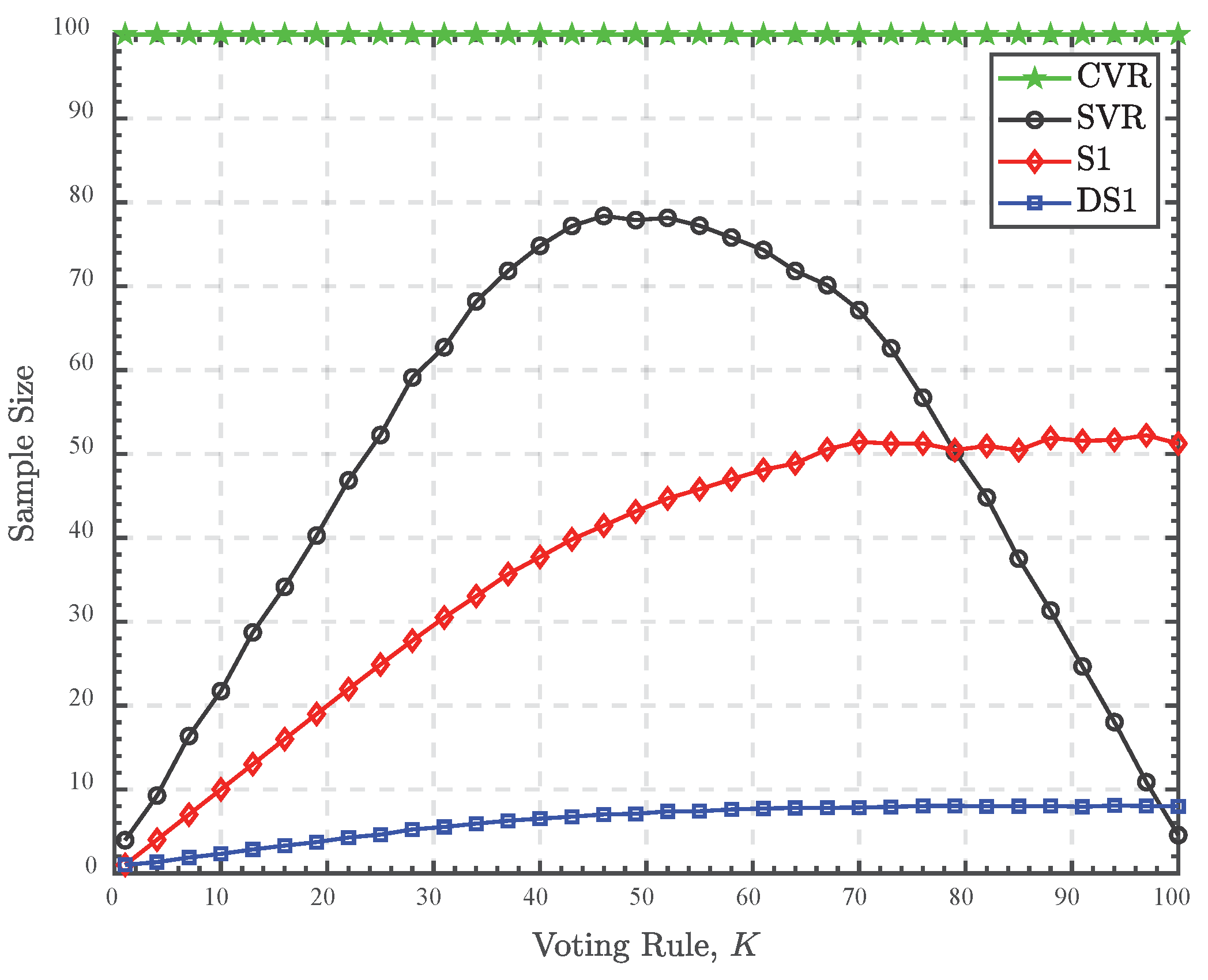

3.3.2. Sample Size Analysis

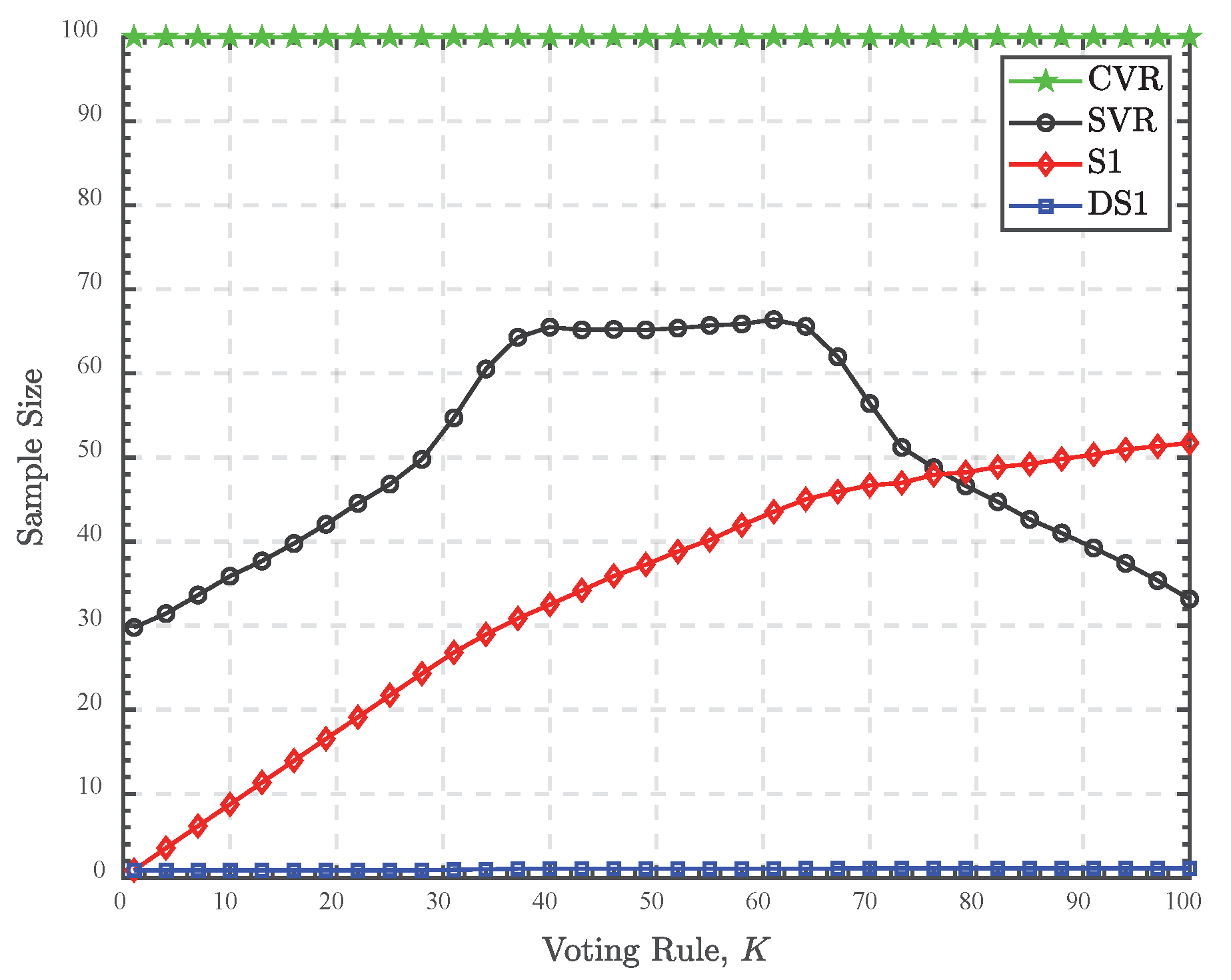

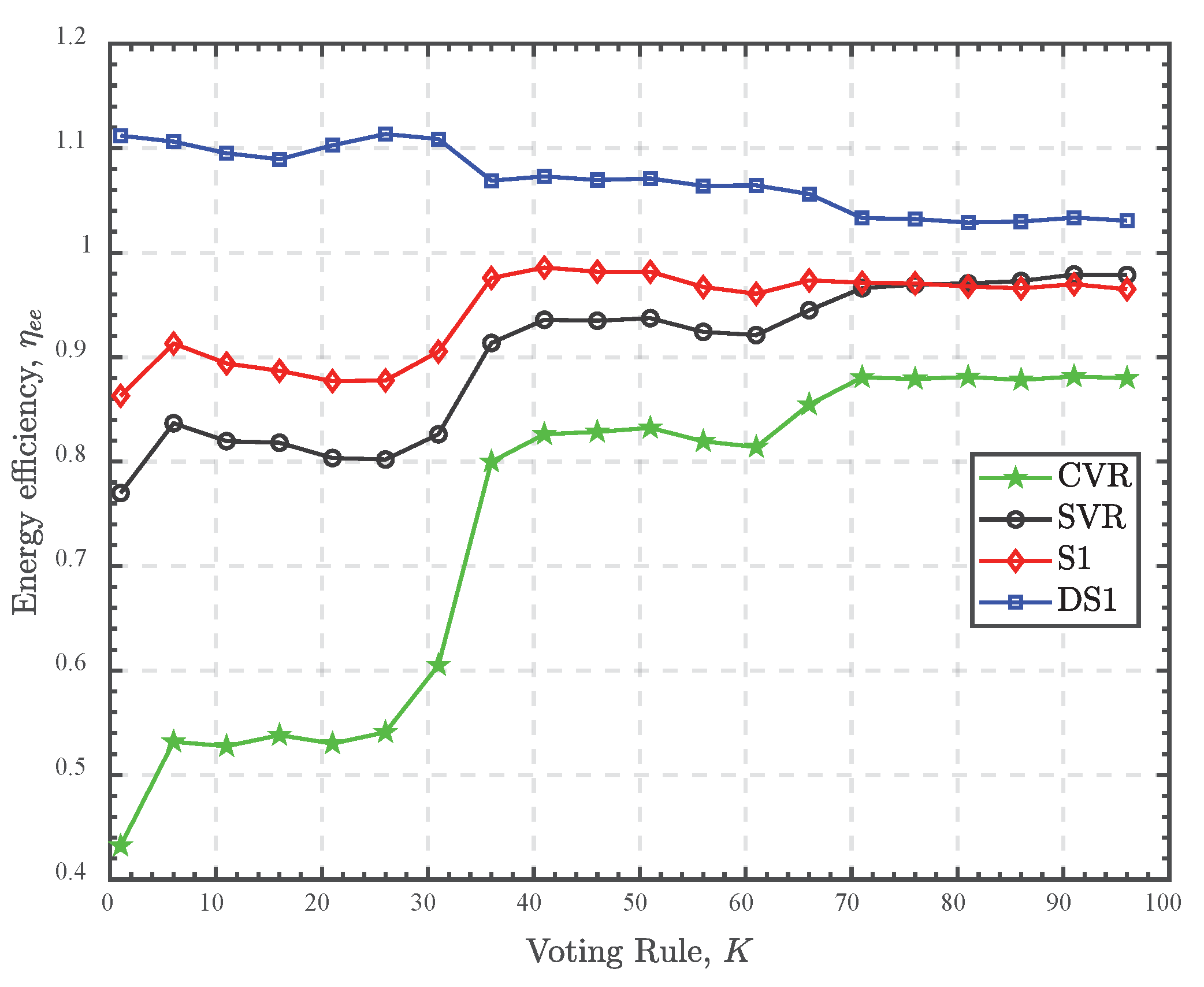

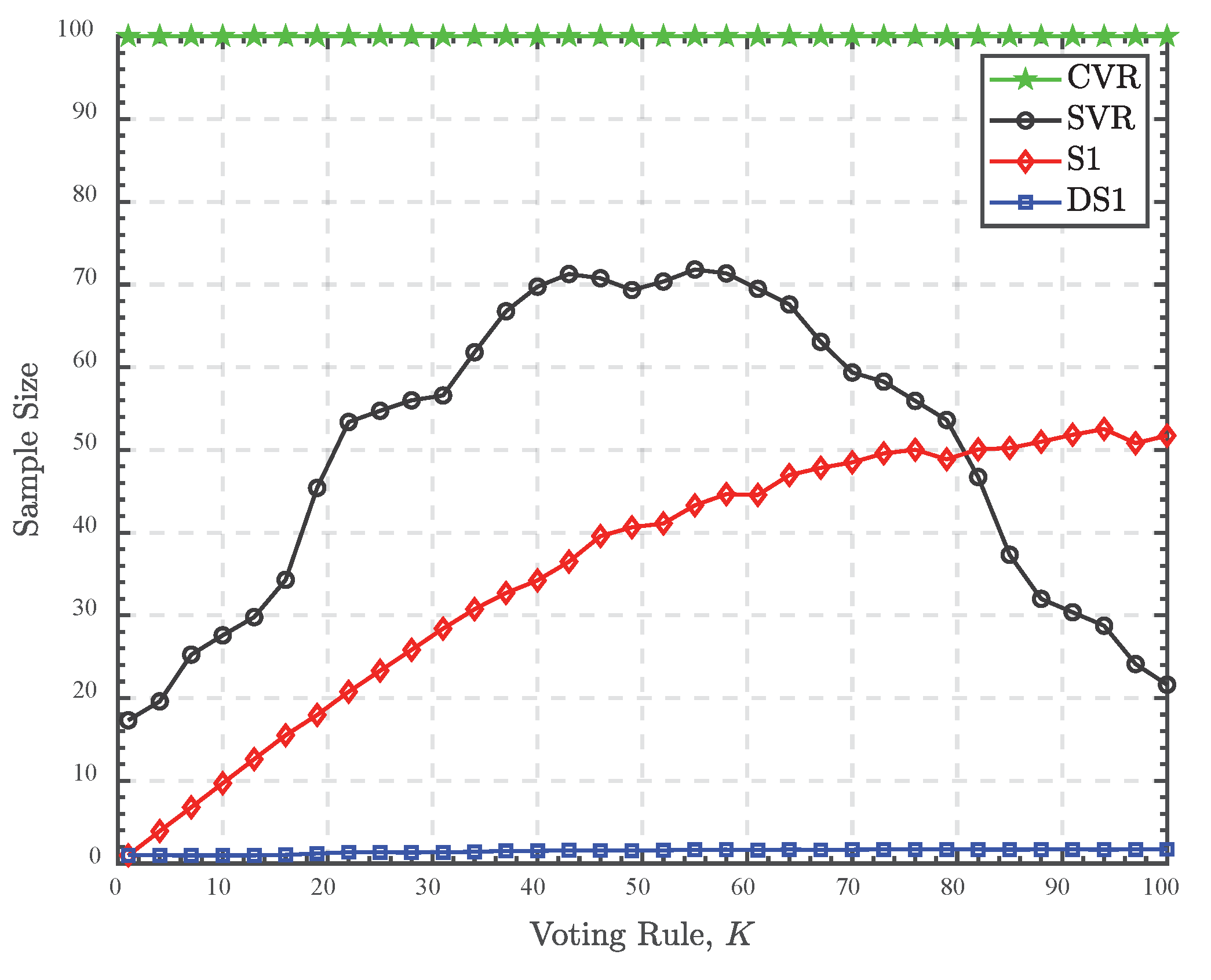

In terms of the sample size, it is obvious that CVR sends all samples to the FC via the reporting channel, and SVR accepts the samples sequentially until the decision condition is met. In addition, based on SVR, S1 has the capability to decrease the required number of samples of 0 for making decision. The advantage of DS1 lies in its differential mechanism which can greatly reduce the number of samples for making global decisions compared to S1. In summary, unlike detection performance (which has the same global detection performance under the same decision condition), the sample size of the four voting rules of the same decision condition are also affected by the PU activity scenario.

3.3.3. EE Evaluation

In addition to the detection performance and sample size, we further evaluate EE and start with conducting SE and EC in the process of CSS. In CUAVNs, the achievable throughput in the absence of the PU can be expressed as

where

is SNR during UAV transmission,

,

is UAV’s transmitting power. Similarly the achievable throughput in the presence of the PU can be expressed as

where

,

is the PU’s transmitting power.

The SE of the proposed cooperation mode among multiple UAVs and mini-slots can be given by

where

are the probability of hypotheses

and

, respectively.

In order to further evaluate EE, it is also necessary to analyze the EC of the proposed cooperation mode among multiple UAVs and mini-slots as

where

is the sensing power consumed by UAV, the power consumed by the circuit is

,

is the reporting power required in reporting slot. Following SE and EC, EE can be given by

4. SVM Dynamic Selection

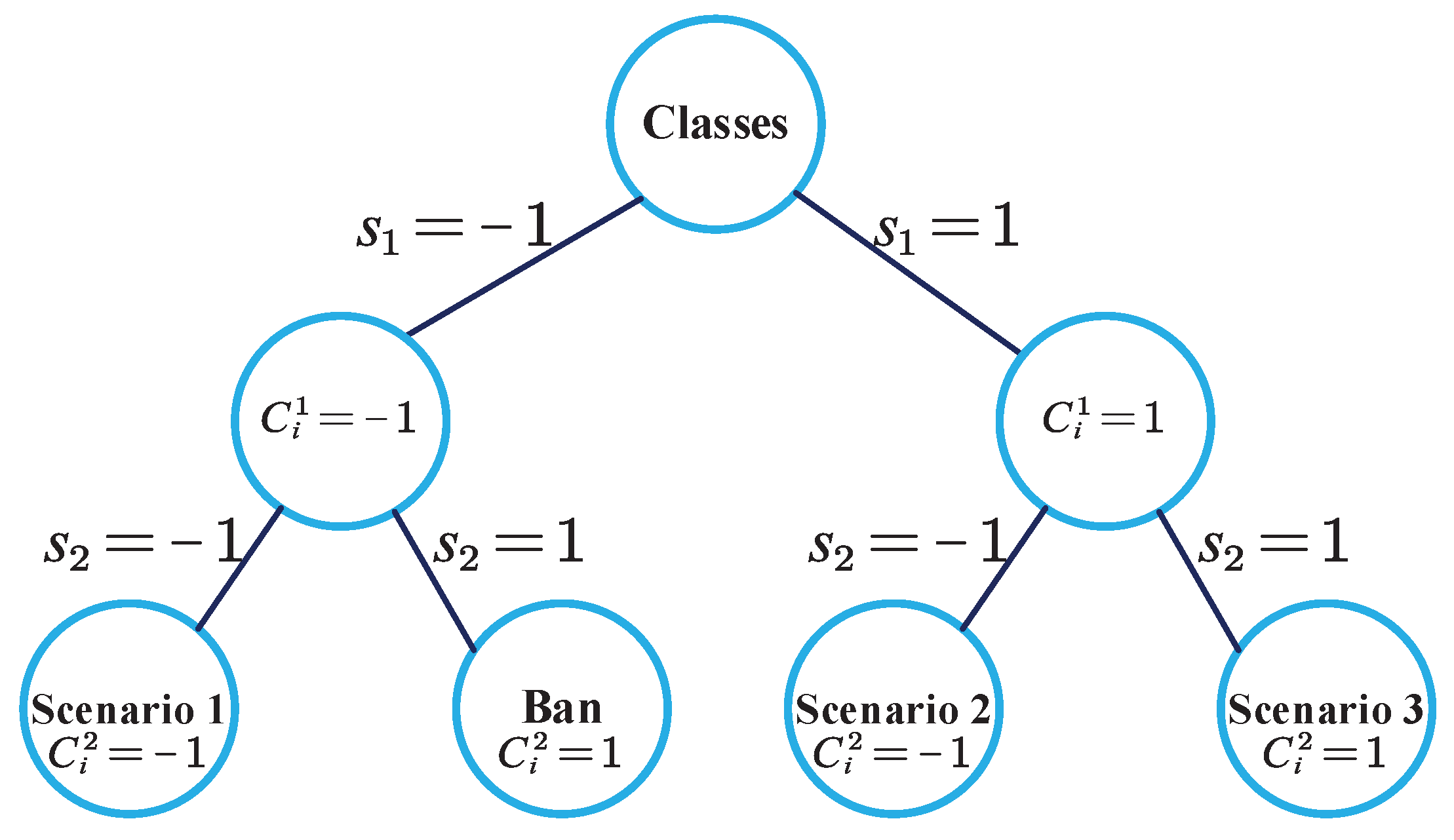

According to above investigation and analysis, a series of voting rules have the same detection performance, but the number of samples or EE still depends on the PU activity and decision condition. In this section, SVM is used to classify the four voting rule corresponding to the different PU scenarios. Through SVM, it is straightforward for CUAVNs to select the optimal voting rule and achieve the best detection performance and efficiency.

4.1 Training Sample Set

To improve the generalizability of the model and algorithm, meanwhile, considering the different peak periods of the PU utilizing the channel in different regions, the status of the PU changes as time goes by, the PU activity divides into three scenarios, Scenarios 1, 2, and 3 respectively correspond to the PU status, i.e., inactive, relatively active, and active. The active and inactive correspond to the duration of the same state of the PU. If the PU frequently changes state after a small number of spectrum sensing frames, the PU is regarded as the active state, and the state is changed only after a large number of spectrum sensing frames, and the PU is regarded as the inactive state. The relatively active is the intermediate state between the inactive state and the active state.

As shown in

Figure 7, the three-category of the PU activity is decomposed into two binary classification problem, so the training sample sets of SVM are formed as

where

respectively correspond to the mean and variance of the

-th mini-slot,

indicates the training label. As a result of being transformed into two binary classification problems, there are two datasets

. In order to find the partition hyperplane with “maximum margin” in the two-dimensional sample set, its parameters must meet the following conditions

To maximize the interval, we only need to maximize

, which is equivalent to minimizing

, hence (20) can be rewritten as

4.2 SVM Dynamic Selection

Considering the difference of the cooperative performance and efficiency of the voting rule, we adopt SVM to classify the three scenarios of the PU before the FC fully accepts all/partial samples to predict the current state of the PU, so as to always select the best voting rule in various sensing environments and parameters.

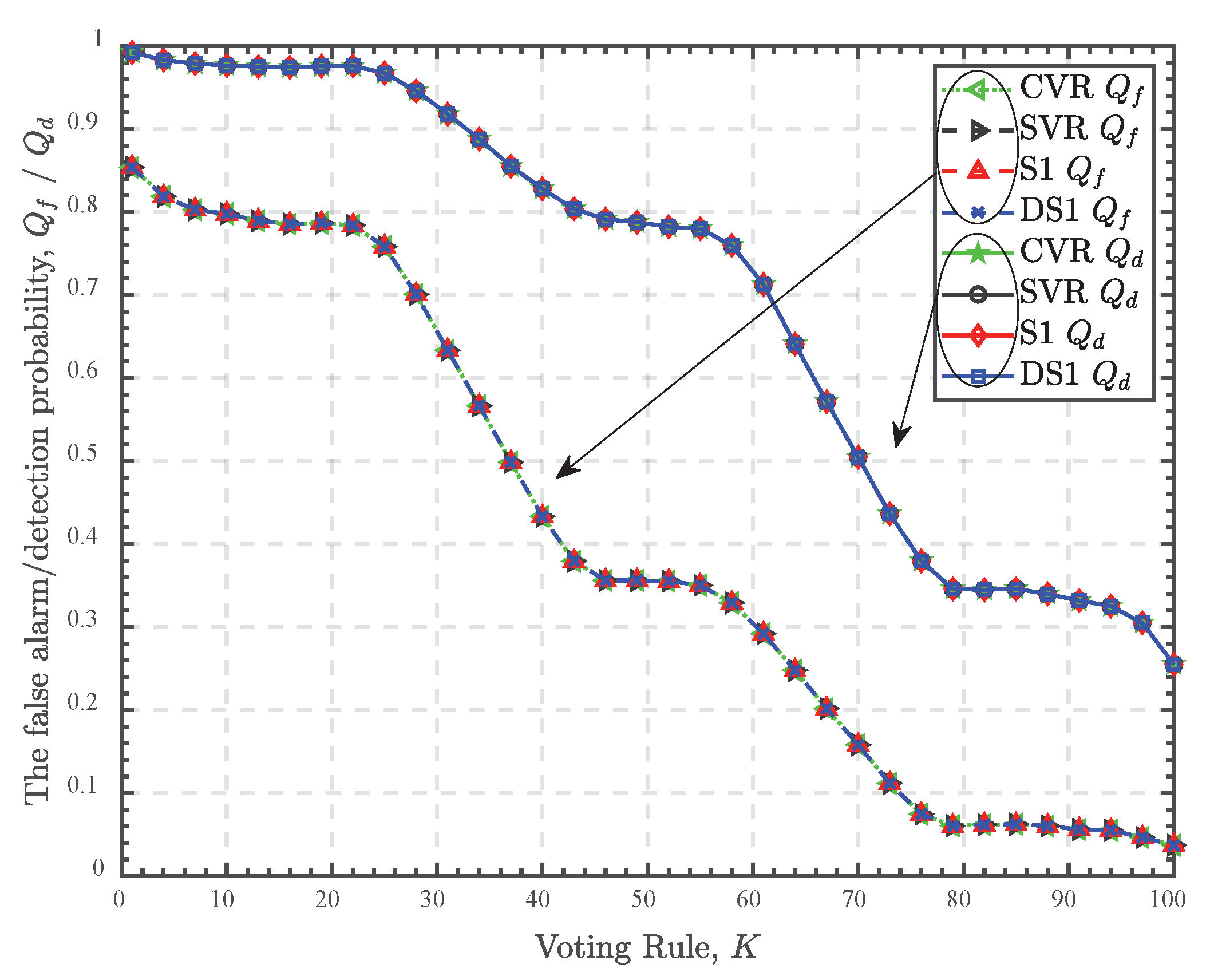

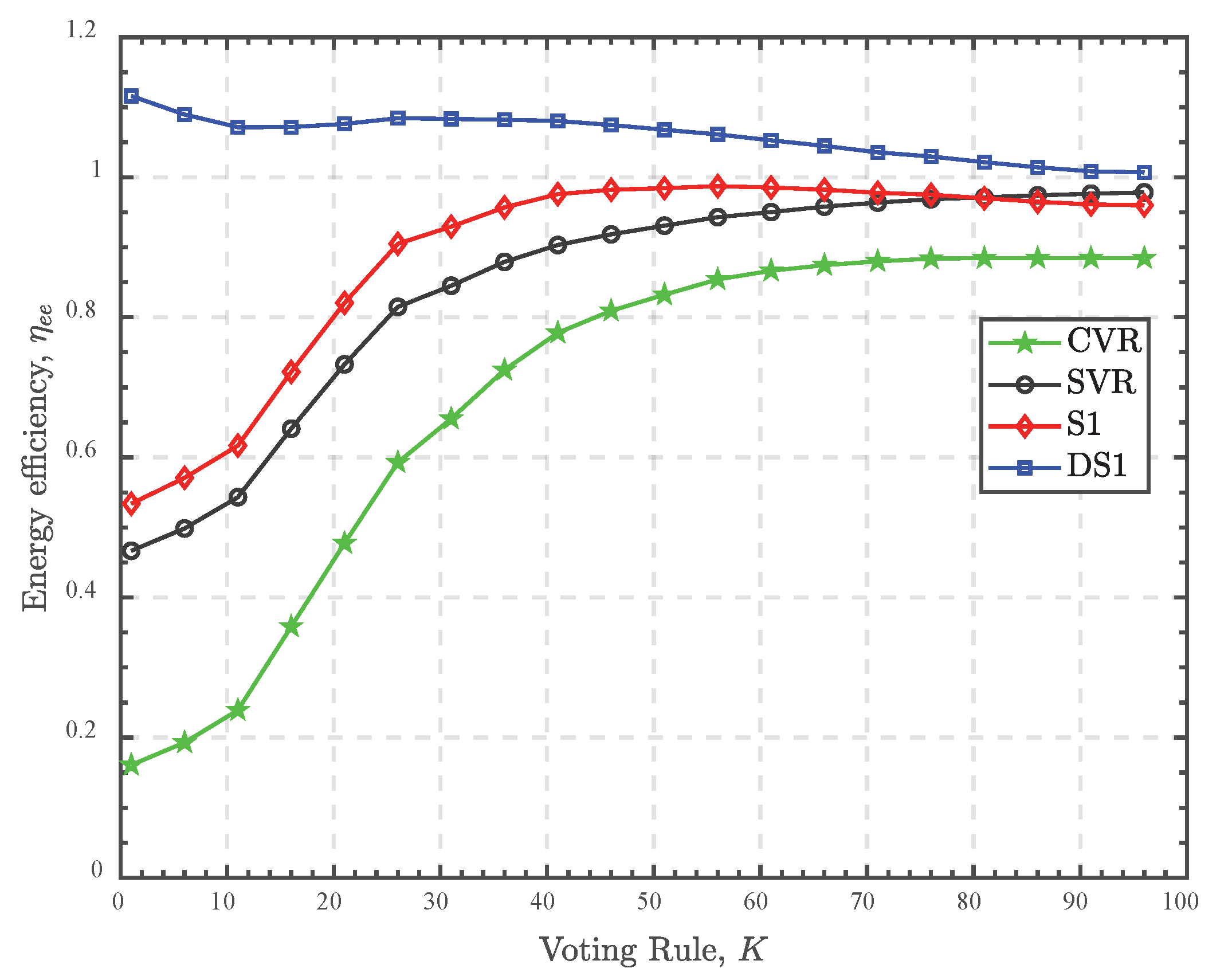

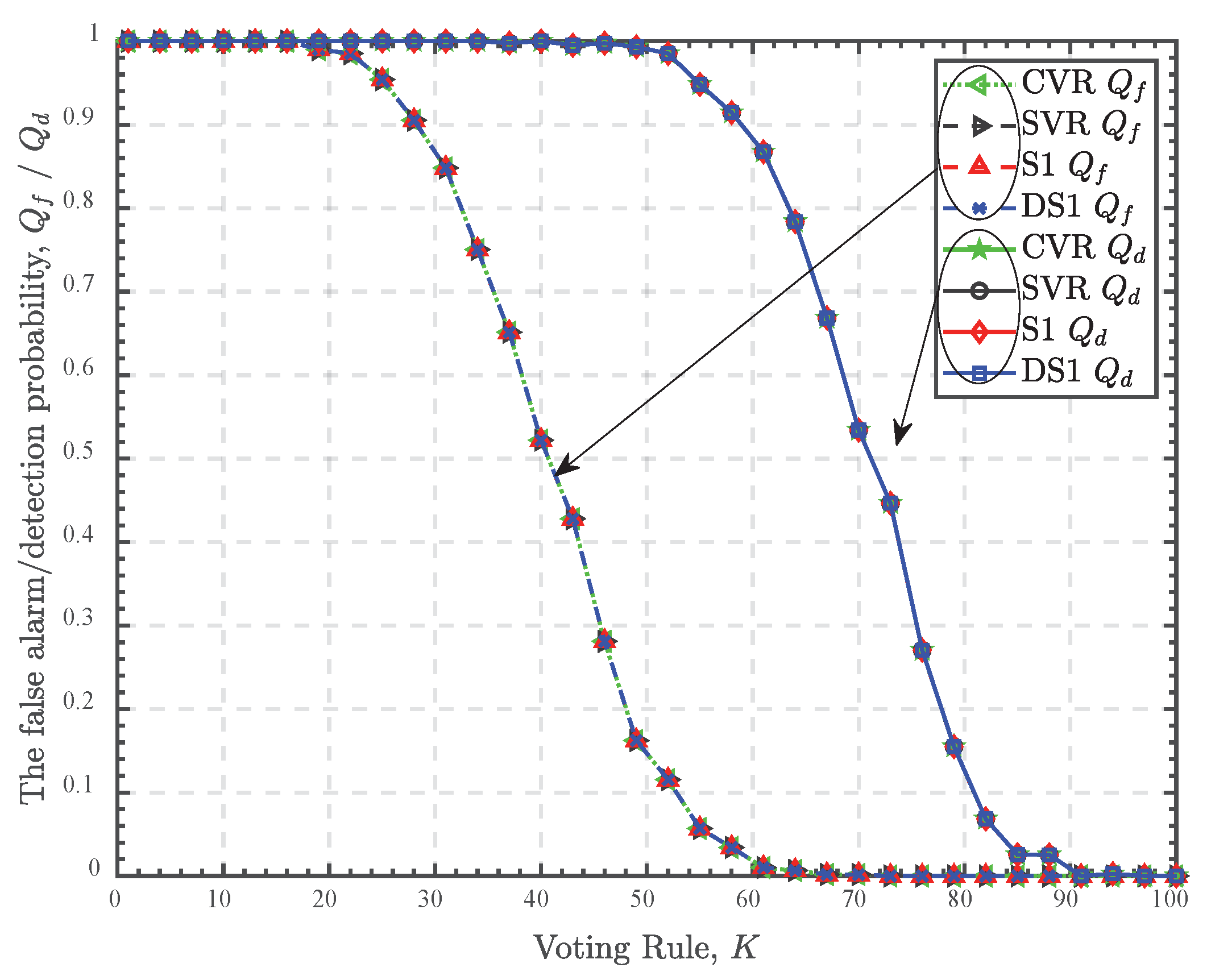

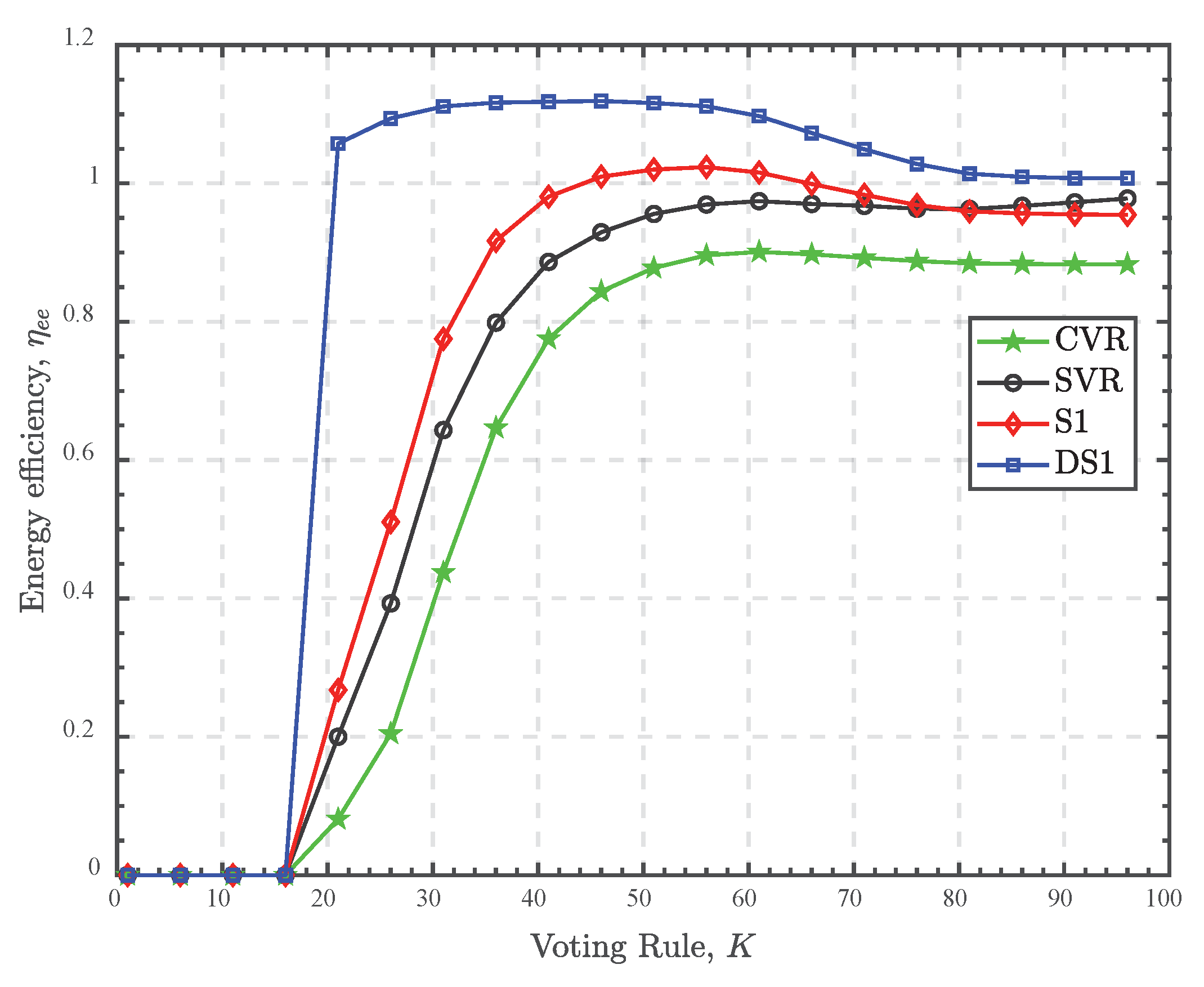

5. Simulation Results

In this section, numerical simulations are presented to verify the proposed DS1. Meanwhile, we also make a comprehensive performance comparison between DS1 and CVR, SVR, and S1, in term of the detection performance, sample size and EE. Further, SVM is used to dynamically select the optimal voting rule in various PU scenarios to achieve the best cooperative performance and efficiency.

5.1 Simulation Environments

To build a fair comparison framework, the sensing slot is divided into 100 mini-slots (the number of UAVs

in the cooperation mode among multiple UAVs). The parameters, i.e., the local performance, EC, reporting time, and transmission time etc., are all summarized in

Table 2.

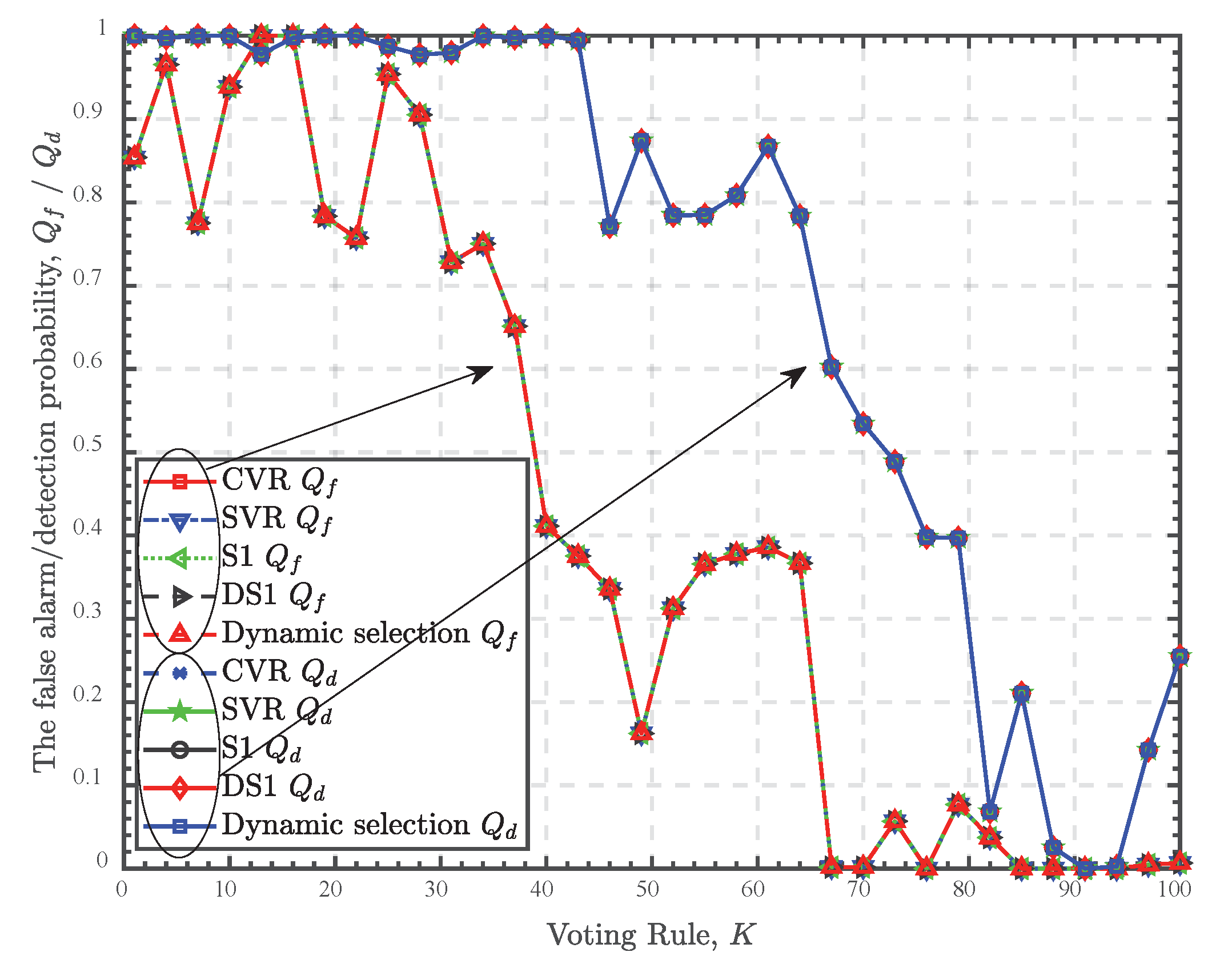

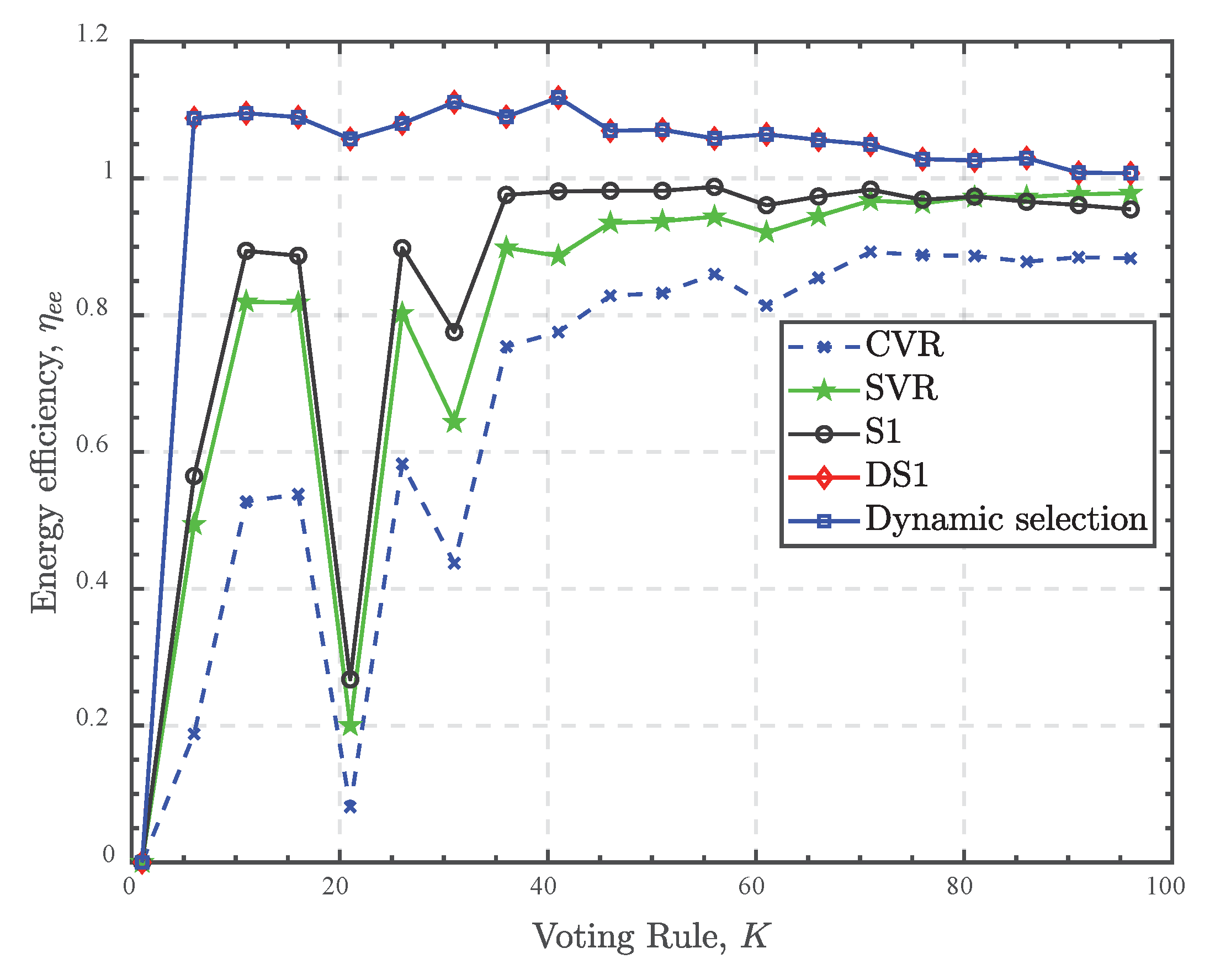

5.3. Analysis of SVM Dynamic Selection

In a rich variety of sensing environments, the PU may be present or absent as time goes by, then the PU activity randomly varies from

Scenarios 1,

2, and

3. In front of this, the optimal performance and efficiency can be achieved by means of SVM, as shown in

Figure 17 and

Figure 18.

Since the PU randomly switches among

Scenarios 1,

2, and

3, the false alarm and detection probability decrease in a jittery manner as

increases. Following previous simulation results, SVM dynamic selection has the same detection performance as well as four voting rules regardless of the decision condition in

Figure 17. Different from the detection performance, SVM dynamic selection is provided with the same EE as well as DS1 in

Figure 18, which demonstrates that DS1 always has the best EE among four voting rules at different

. That is to say, SVM dynamic selection can select the optimal voting rule in a timely manner based on the changes in the PU scenario or decision condition.

6. Conclusions and Future Works

In this paper, we have conducted a comprehensive investigation of the voting rules (i.e., CVR, SVR, and S1) for CSS and proposed DS1 based on the voting rule. In view of this, motivated by drawbacks of the cooperative mode among multiple UAVs, we propose a cooperative mode among multiple mini-slots to realize CSS, in which the decision samples are not needed to be submitted to the FC via the reporting channel. Furthermore, through a series of analyses on CVR, SVR, and S1, we are encouraged by the sequential idea and differential mechanism to propose a DS1 which significantly reduces the number of decision samples required by the global decision making. Additionally, we adopt SVM to dynamically select the optimal voting rule according to various scenarios of the PU activity. This adaptive switching between voting rules enhances the capability to handle complex PU scenarios in the future and enables the exploration of more efficient voting rule. Finally, numerical simulation results demonstrate that the proposed DS1 always efficiently achieve the best EE without the detection performance loss and the SVM dynamic selection is beneficial for CUAVNs to choose the best voting rule.

Although the impact of different voting rules in various PU scenarios has been taken into consideration, in practice, the optimization of detection performance and EE remains a challenging problem due to factors such as flight trajectories, channel models, and Byzantine attacks. Furthermore, it should be noted that the method proposed in this paper is specifically designed for voting rules as a data fusion technique. It may not be directly applicable or suitable for other data fusion methods, highlighting the need for further exploration in the future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.W.; methodology, J.S., J.W., and J.G.; software, J.S.; validation, J.S.; formal analysis, J.S and J.W.; investigation, J.W.; resources, J.W.; data curation, J.S.; writing—original draft preparation, J.S.; writing—review and editing, J.S. and R.Z.; visualization, J.S.; supervision, J.W.; project administration, C.Y., J.W., M.S., L.Q., and W.C.; funding acquisition, C.Y., J.W., and W.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant No. 62201186, Open Fund of Key Laboratory of Flight Techniques and Flight Safety, CAAC (No. FZ2022KF12).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Stamatescu, G.; Popescu, D.; Dobrescu, R. Cognitive radio as solution for ground-aerial surveillance through WSN and UAV infrastructure. In Proceedings of the 2014 6th International Conference on Electronics, Computers and Artificial Intelligence (ECAI), Bucharest, Romania, 2014; pp. 51-56. [Google Scholar]

- Bostian, C.W.; Young, A.R. The application of cognitive radio to coordinated unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) missions; Virginia Polytechnic Inst and State Univ Blacksburg. Crystal City, VA, USA, 2011.

- Saleem, Y.; Rehmani, M.H.; Zeadally, S. Integration of Cognitive Radio Technology with unmanned aerial vehicles: Issues, opportunities, and future research challenges. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2015, 50, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, H.; Kaabouch, N. Improving the Reliability of Unmanned Aircraft System Wireless Communications through Cognitive Radio Technology. Commun. Netw. 2013, 05, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, H.; Gellerman, N.; Kaabouch, N. A cognitive radio system for improving the reliability and security of UAS/UAV networks. In 2015 IEEE Aerospace Conference, Big Sky, MT, USA, 2015; pp. 1-9.

- Santana, G.M.D.; de Cristo, R.S.; Branco, K.R.L.J.C. Integrating Cognitive Radio with Unmanned Aerial Vehicles: An Overview. Sensors 2021, 21, 830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana, G.M.D.; Cristo, R.S.; Dezan, C.; Diguet, J.-P.; Osorio, D.P.M.; Branco, K.R.L.J.C. Cognitive Radio for UAV communications: Opportunities and future challenges. In 2018 International Conference on Unmanned Aircraft Systems (ICUAS), Dallas, TX, USA, 2018; pp. 760-768.

- Ruan, L.; Wang, J.; Chen, J.; Xu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Jiang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, Y. Energy-efficient multi-UAV coverage deployment in UAV networks: A game-theoretic framework. China Commun. 2018, 15, 194–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wu, J.; Gan, J.; Chen, Z.; He, J.; Chen, Z. Energy Efficiency of Cooperative Spectrum Sensing Under Sensing Delay Constraint for CUAVNs. In 2022 IEEE 95th Vehicular Technology Conference:(VTC2022-Spring), Helsinki, Finland, 2022; pp. 1-6.

- Wu, J.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Z. Optimal Utility of Cooperative Spectrum Sensing for CUAVNs. 2021 IEEE 93rd Vehicular Technology Conference (VTC2021-Spring), Helsinki, Finland, 2021; pp. 1-6.

- Liu, Z. , Li, R., Zhao, D.; Yang, J. Research on spectrum sensing of multiple UAVs based on group cooperative. In 2022 7th International Conference on Intelligent Computing and Signal Processing (ICSP), Xi'an, China, 2022; pp. 1858-1862.

- Xiong, J.; Luo, Z. Energy-efficient for Multi-UAV Cognitive Radio Network with Normalized Spectrum Algorithm. In 2022 International Conference on Computing, Communication, Perception and Quantum Technology (CCPQT), Xiamen, China, 2022; pp.334-3381.

- Hosen, M.S.; Peng, Y. Dynamic channel allocation technique for cognitive radio based UAV networks. In 2021 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Big Data Analytics, Bandung, Indonesia, 2021; pp. 152-155.

- Khalid, W.; Yu, H. Residual Energy Analysis with Physical-Layer Security for Energy-Constrained UAV Cognitive Radio Systems. In 2020 International Conference on Electronics, Information, and Communication (ICEIC), Barcelona, Spain, 2020; pp. 1-3.

- Hu, H.; Da, X.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Ni, L.; Pan, Y. SE and EE Optimization for Cognitive UAV Network Based on Location Information. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 162115–162126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Chen, Y.; Li, P.; Zhang, J.; Wang, C.; Tang, J.; Xia, L.; Lu, C.; Song, T. Optimisation of virtual cooperative spectrum sensing for UAV-based interweave cognitive radio system. IET Commun. 2021, 15, 1368–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; An, Q.; Han, H.; Fu, Y.; Zhang, Y. Optimization of Spectrum Efficiency in UAV Cognitive Communication Network Based on Trajectory Planning. In Proceedings of the 2021 11th International Conference on Communication and Network Security, New York, USA; 2021; pp. 35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Guan, M.; Zhang, X.; Ding, H. Spectrum Sensing Optimization in an UAV-Based Cognitive Radio. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 44002–44009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wu, J.; Chen, Z.; Chen, Z.; Gan, J.; He, J.; Wang, B. Spectrum- and Energy- Efficiency Analysis Under Sensing Delay Constraint for Cognitive Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Networks. KSII Trans. Internet Inf. Syst. 2022, 16, 1392–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, F.; Ding, G.; Wang, Z.; Wu, Q. UAV-Based 3D Spectrum Sensing in Spectrum-Heterogeneous Networks. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2019, 68, 5711–5722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Da, X.; Hu, H.; Zhu, Z.; Xu, R.; Ni, L. Energy-Efficiency Optimization of UAV-Based Cognitive Radio System. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 155381–155391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Wang, X. A High-efficiency Collaborative Spectrum Sensing with Gated Recurrent Unit for Multi-UAV Network. In 2021 31st International Telecommunication Networks and Applications Conference (ITNAC), Sydney, Australia, 2021: pp. 180-187.

- Nie, R.; Xu, W.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, P.; Pan, M.; Lin, J. Max-Min Distance Clustering Based Distributed Cooperative Spectrum Sensing in Cognitive UAV Networks. In ICC 2019-2019 IEEE International Conference on Communications, Shanghai, China, 2019; pp. 1-6.

- Zhu, H.; Song, T.; Wu, J.; Li, X.; Hu, J. Cooperative Spectrum Sensing Algorithm Based on Support Vector Machine against SSDF Attack. In 2018 IEEE international conference on communications workshops (ICC workshops), Kansas City, MO, USA, 2018; pp. 1-6.

- Gul, N.; Kim, S.M.; Ahmed, S.; Khan, M.S.; Kim, J. Differential Evolution Based Machine Learning Scheme for Secure Cooperative Spectrum Sensing System. Electronics 2021, 10, 1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikaeil, A.M.; Guo, B.; Wang, Z. Machine learning to data fusion approach for cooperative spectrum sensing. In 2014 International Conference on Cyber-Enabled Distributed Computing and Knowledge Discovery, Shanghai, China, 2014; pp. 429-434.

- Luan, H.; Li, O.; Zhang, X. Cooperative Spectrum Sensing with energy-efficient Sequential Decision Fusion rule. In 2014 23rd Wireless and Optical Communication Conference (WOCC), Newark, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 1-4.

- Liang, J.; Dai, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, X.; Xu, M. Energy-efficient analysis of cooperative spectrum sensing in CRN. Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Wireless Communications, Networking and Mobile Computing (WiCOM), Shanghai, China, 2015; pp. 1-5.

- Mahendru, G. A Novel Double Threshold-Based Spectrum Sensing Technique at Low SNR Under Noise Uncertainty for Cognitive Radio Systems. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2022, 126, 1863–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Yu, Y.; Song, T.; Hu, J. Sequential 0/1 for cooperative spectrum sensing in the presence of strategic Byzantine attack. IEEE Wireless Communications Letters, 2018, 8, 500–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, J. , Wu, J., Li, P., Chen, Z., Chen, Z., Zhang, J.; He, J. Malicious Exploitation of Byzantine Attack for Cooperative Spectrum Sensing. In 2022 IEEE 23rd International Workshop on Signal Processing Advances in Wireless Communication (SPAWC), Oulu, Finland, 2022; pp. 1-5.

- Liang, Y.-C.; Zeng, Y.; Peh, E.C.; Hoang, A.T. Sensing-Throughput Tradeoff for Cognitive Radio Networks. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2008, 7, 1326–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).