3.1. Differential Investment in Translation Machinery

Ribosomes represent parallel protein-production factories and their abundance in

E. coli and their abundance increases linearly with growth rate [

108,

109]. Short-generation species may have not only more efficient factories but also more factories than LGB. Each ribosome features a set of 16S, 23S, and 5S rRNAs that are transcribed from the same operon and processed into individual rRNAs [

110].

E. coli has seven rRNA operons (

rrnA to

rrnE, rrnG, rrnH) with promotors that are almost identical to the -10 and -35 consensus [

111,

112], suggesting a high demand for rRNA molecules met by both efficient and parallel transcription of multiple rRNA operons. The production of ribosomes in

E. coli is limited by rRNA production [

113], which explains why

E. coli maintains multiple

rrn operons in its genome for parallel transcription. A generalization of this would lead to the prediction that SGB should have more

rrn operons than LGB. This prediction should also apply to tRNA genes because, with more ribosomes, more tRNA molecules are needed [

114].

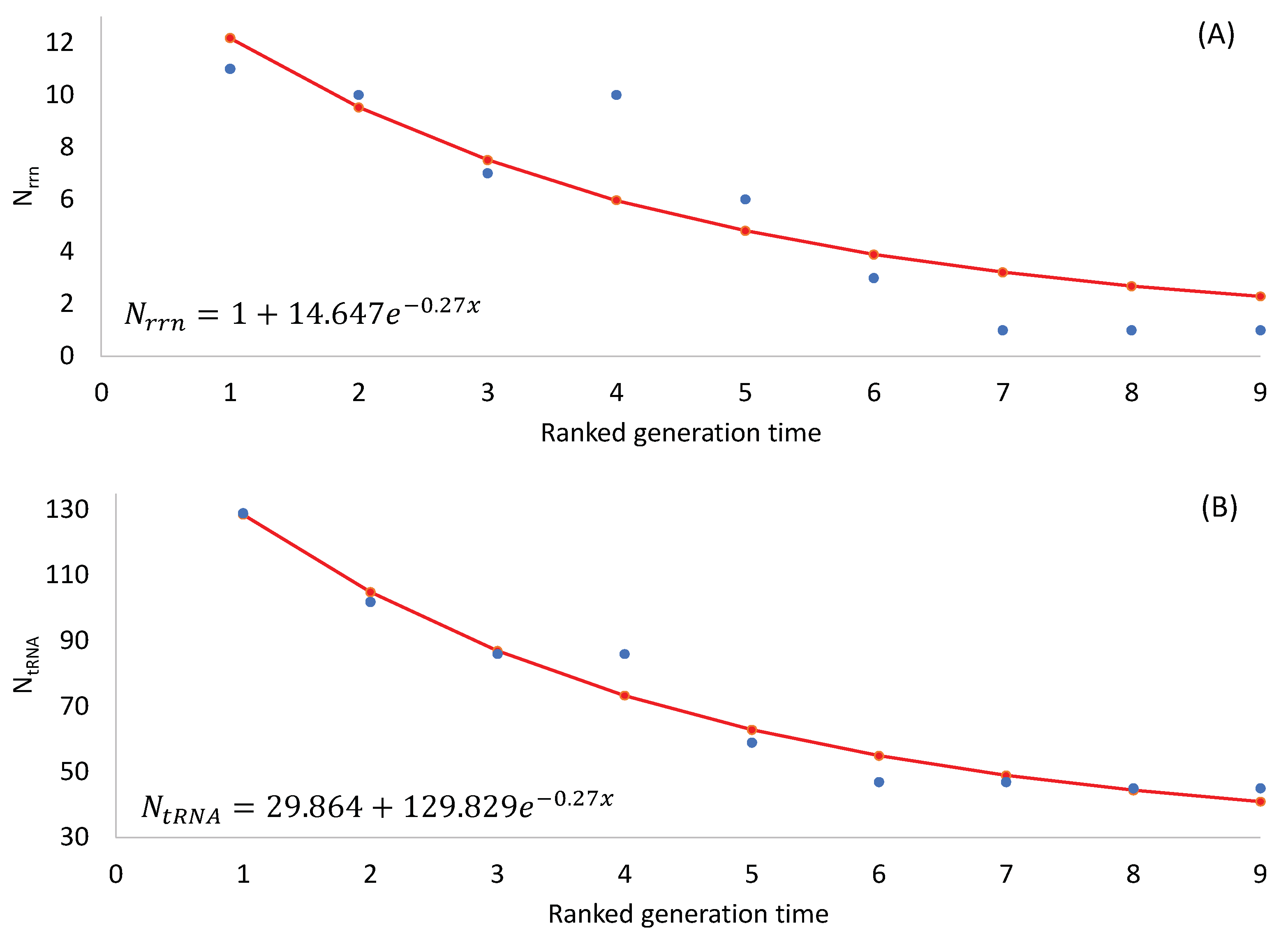

The two predictions are both supported by empirical evidence (

Table 2), with the number of rRNA and tRNA genes decreasing highly significantly with increasing generation time (p < 0.0001 for any rank-based nonparametric tests). The observation that SGB maintains more rRNA and tRNA genes in their genomes than LGB is consistent with the interpretation of stronger selection for translation efficiency in SGB than in LGB.

Note that an organism needs at least one

rrn operon for translation, so the number of

rrn operons cannot be smaller than 1. Also, there should be a minimum set of tRNA genes to decode all 61 sense codons. One might use the following two equations to model the number of

rrn operons and tRNA genes, respectively:

where

x is RankGT in

Table 2 Eq. (1) ensures a minimum

Nrrn of 1, and Eq. (2) ensures a minimum

NtRNA of c. The parameters were estimated by the least-squares approach, and the fitted equations were plotted in

Figure 1.

3.2. Differential Preference of Start Codon AUG

Among the three canonical start codons (AUG, GUG, and UUG), translation initiation efficiency is consistently in the order of AUG > GUG > UUG [

115,

116]. HEGs in bacteria and bacteriophages tend to prefer AUG as a start codon [

5,

9,

18,

115,

116,

117]. This is true for all nine bacterial species in which the percentage of AUG (AUG%,

Table 3) is consistently higher in HEGs than those in REST (

Table 3) which includes all genes not in the HEGs group and consequently contains both highly expressed and lowly expressed genes. This suggests that AUG is the most efficient start codon and is consistent with previous empirical studies based on within-species comparisons [

5,

8,

9].

Given that AUG is the most efficient start codon, one would predict that SGB should use more AUG as start codons than LGB. AUG% in

Table 3 is indeed strongly associated with ranked generation time in

Table 1 as predicted. However, AUG% is also affected by genomic GC% because GC-rich genomes tend to have more GC-rich codons [

29]. In terms of start codon usage, GC-rich genomes may use more GUG as start codons than AUG. Because the four LGB all have higher GC% than the five species with relatively short generations, they may use fewer AUG and more GUG as start codons simply because of their genomic GC-richness. For this reason, it is necessary to include genomic GC as a control variable. Also, HEGs and REST genes may differ in the relationship. A conceptually more comprehensive and explicit model is therefore needed.

Here the dependent variable is AUG%, and independent variables include ranked generation time (RankGT), genomic GC content (GC%), and gene expression (GE with two categories, HEGs and REST encoded as 0 and 1, respectively). The input data (

Table 4) is used to fit the model.

A regression analysis of the input data in

Table 4 shows that all three independent variables are statistically significant, but interaction terms are not (

Table 5). The regression model was then fitted without interaction terms. This reduced model accounts for 82.0% of the variation in the dependent variable AUG%. The two regression equations derived from the regression coefficients in

Table 5, one for HEGs and the other for REST, are

Eqs. (3) and (4) and

Table 5 show that AUG% decreases highly significantly with generation time, and that AUG% is significantly higher in HEGs than REST genes (

Table 5). This is consistent with the interpretation of stronger selection operating on SGB than on LGB. That is, a non-AUG start codon mutating to AUG is more strongly favored by natural selection in SGB than in LGB.

We should emphasize that Eqs. (3) and (4) are descriptive models. They do not explicitly prevent AUG% from taking values smaller than 0 or larger than 1. A sigmoidal function would have been more appropriate if there were enough data for parameter estimation.

3.3. Differential Preference of Stop Codon UAA

As reviewed previously, stop codon UAA exhibits the smallest readthrough error rate among the three nonsense codons [

55,

59,

60,

61,

62,

63,

64]. Consequently, HEGs favor stop codon UAA over other stop codons in multiple bacterial species [

9,

65,

72]. This is true for all nine bacterial species (data not shown). Given that UAA is the best stop codon, we predict that SGB should use more UAA as stop codons than LGB. Similar to our analysis of the start codon AUG usage, the dependent variable now is UAA%, and independent variables include ranked generation time (RankGT), genomic GC content (GC%), and gene expression (GE with two categories, HEGs and REST encoded as 0 and 1, respectively). The genomic GC% is particularly relevant in studying UAA usage because protein-coding genes in a GC-rich genome tend to use more UGA and UAG stop codons than those in an AT-rich genome [

65].

A regression analysis shows that all three independent variables are statistically significant (

Table 6). The model accounts for 94.7% of the total variation in UAA%. The two regression equations derived from the regression coefficients in

Table 6, one for HEGs and the other for REST, are

Eqs. (5) and (6) and

Table 6 show that UAA% decreases highly significantly with generation time, and that HEGs use UAA significantly more frequently than REST genes (

Table 6, a 17.35326% difference between the two). This is consistent with the interpretation of stronger selection operating on SGB than on LGB. A non-UAA stop codon mutating to UAA is more strongly favored by natural selection in SGB than in LGB.

UAA usage also decreases significantly with genomic GC% (

Table 6), which is understandable. As genomic GC% increases, GC-biased mutations would favor UAG and UGA codons against UAA codons [

65]. It is for this reason that the genomic GC content needs to be taken into consideration when assessing codon usage bias.

3.4. Differential Selection on Sense Codons

It is difficult to evaluate tRNA-mediated selection on codon usage across species because the codon adaptation index (CAI) [

48,

49] and the index of translation efficiency (I

TE) [

7] are both for comparing genes within-species. The effective number of codons (ENC) [

50,

118] could potentially be used for among-species comparisons, but all these indices are strongly affected by genomic mutation bias [

119,

120]. For example, protein-coding genes in strongly GC-biased genomes will have mostly G-ending and C-ending codons, leading to a reduced ENC that has little to do with selection.

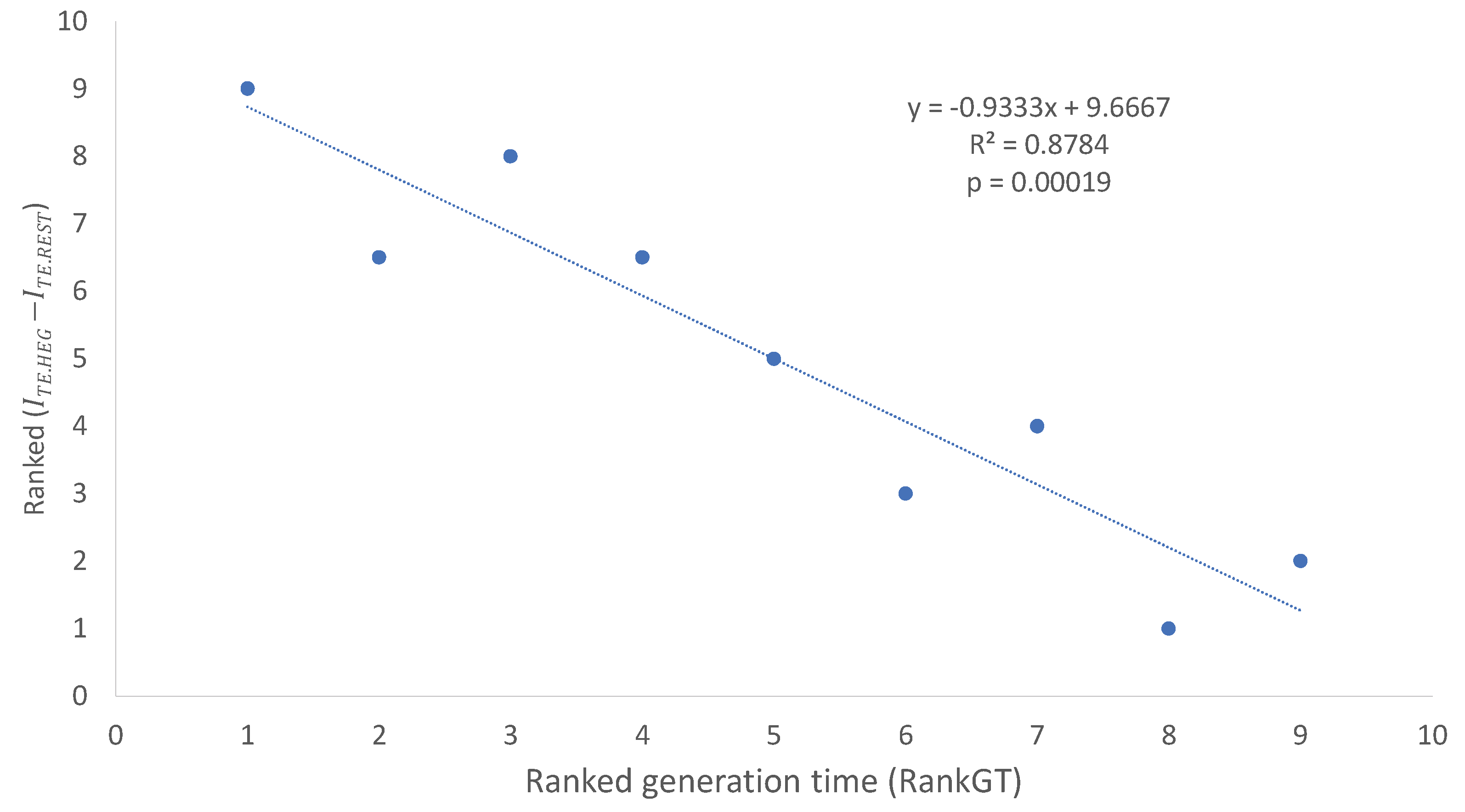

It is reasonable to assume that mutation bias affects both HEGs and REST genes. Thus, the difference in mean I

TE between HEGs and REST, i.e.,

, should be relatively independent of mutation bias. should increase with selection intensity for translation elongation efficiency. If there is no selection for translation elongation efficiency, then is expected to be 0. With increasing strong selection for translation elongation efficiency, should also increase because the selection is expected to be stronger for HEGs than for REST genes. In other words, strong selection for translation efficiency in SGB should drive HEGs towards better codon adaptation than the REST genes, thereby increasing .

The

values and its ranks (Rank

,

Table 7 ) are depends strongly on generation time (RankGT,

Table 7). The relationship is best illustrated with two ranked variables, i.e., ranked generation time (RandGT) and ranked

(

Figure 2). The fitted regression line accounts for 87.84% of the total variation in ranked

(

Figure 2).

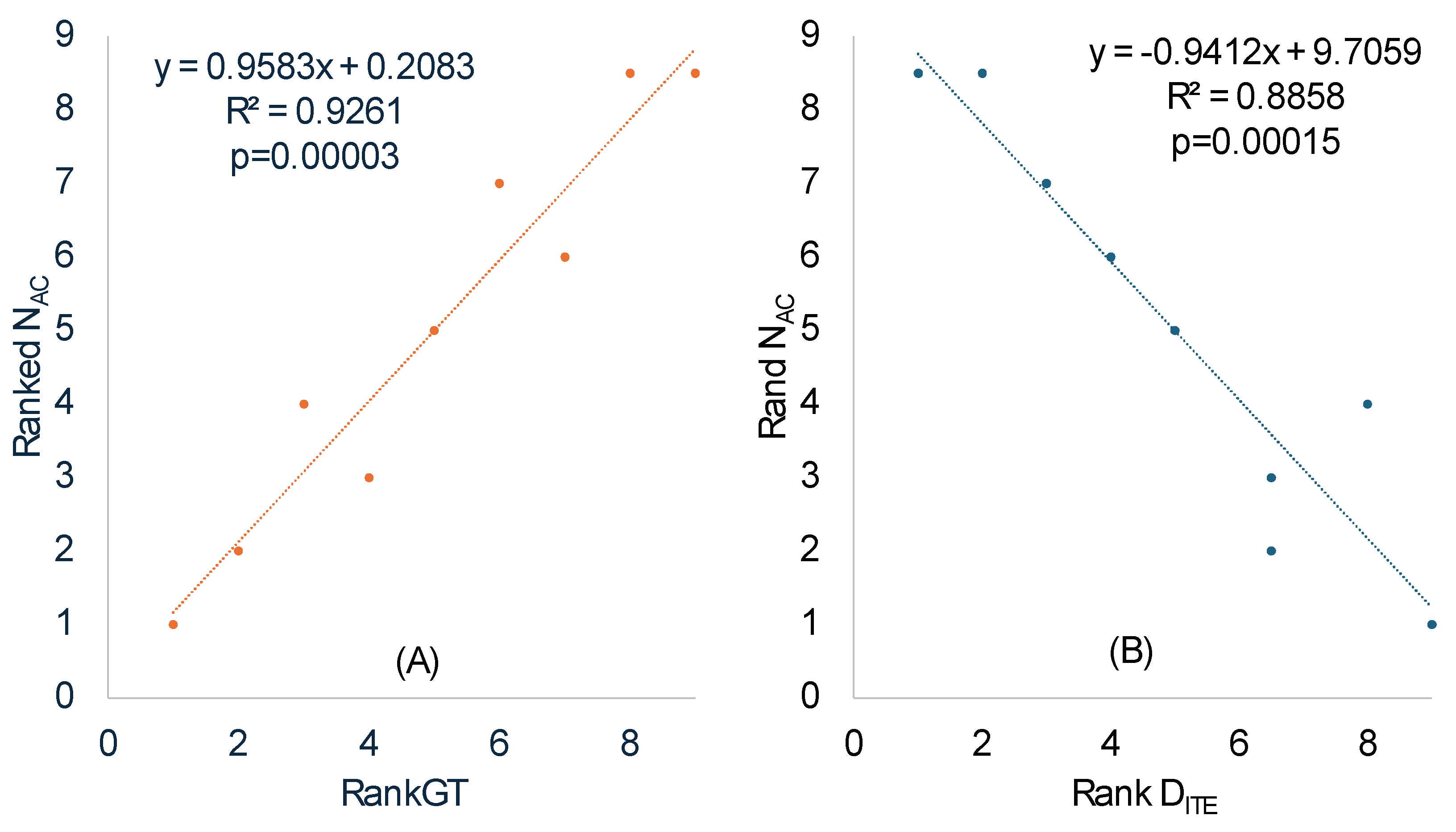

3.5. Differential Selection Drives tRNA Adaptation

Codon and tRNA are expected to coevolve and adapt to each other [

2,

6,

28,

29], especially in highly expressed genes [

6,

7,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

121]. Given the better codon optimization in SGB than in LGB (

Figure 2 and

Table 7), one would predict more tRNA genes for highly used codons than rarely used codons. If we focus on the anticodon of tRNA genes, then the prediction above implies a smaller effective number of anticodons (N

AC), equivalent to the concept of the effective number of codons [

50,

118], in SGB than in LGB. Specifically, N

AC should increase with RankGT (ranked generation time).

We calculated N

AC in the same way the effective number of codons is calculated [

50] except that codons in coding sequences are replaced by anticodons in tRNA genes. The ranked N

AC increases highly significantly with ranked RankGT (

Table 8 and

Figure 3A), consistent with our prediction that SGB should have a smaller N

AC than LGB. One should note the difference between a codon replacement and an anticodon replacement. A codon replacement may have only a minor effect on the translation of a single gene, but an anticodon replacement would affect the translation of numerous codons. For this reason, anticodons are strongly constrained and much less affected by genomic GC%.

N

AC also exhibits a statistically highly significant (p =0.00015,

Figure 3B) positive correlation with Rank

(

Table 7) which measures codon adaptation. This is consistent with our prediction. The major codons are strongly favored, more tRNAs with the corresponding decoding anticodon will be needed to translate such overused codons, leading to decreased N

AC.

The analysis above assumes that tRNA gene copy numbers in the bacterial genomes are proportional to the abundance of tRNA molecules in the cell. With the availability of transcriptomic data, it has been found that the assumption is generally true, i.e., the copy number of a tRNA is highly correlated with the transcriptomic representation of the tRNA [

122].

3.6. Secondary Structure Stability Near the Start and Stop Codons

Sequences immediately flanking translation signals in bacteria (e.g., Shine-Dalgarno sequence, and start and stop codons) tend to have reduced secondary structure to avoid embedding translation signals in a stable secondary structure [

18,

27,

107,

116,

123,

124]. This pattern has also been observed in bacteriophage genes [

5,

9,

15]. The weakening of the secondary structure near, or immediately upstream of, the start codon has also been observed in highly expressed eukaryotic mRNAs [

8,

125], especially in mRNAs requiring internal ribosome entry for translation [

126].

Secondary structure stability in RNA is typically measured by the minimum folding energy (MFE). MFE equal to 0 means no secondary structure, and a stronger secondary structure corresponds to a more negative MFE value. Experiments involving engineered

E. coli genes have shown that translation initiation efficiency depends heavily on MFE of the sequence upstream and including the start codon [

3,

7,

14]. We follow the convention of previous studies [

5,

9,

15] measuring MFE with a sliding window of 40 nt along mRNA sequences to quantify the change of secondary structure stability

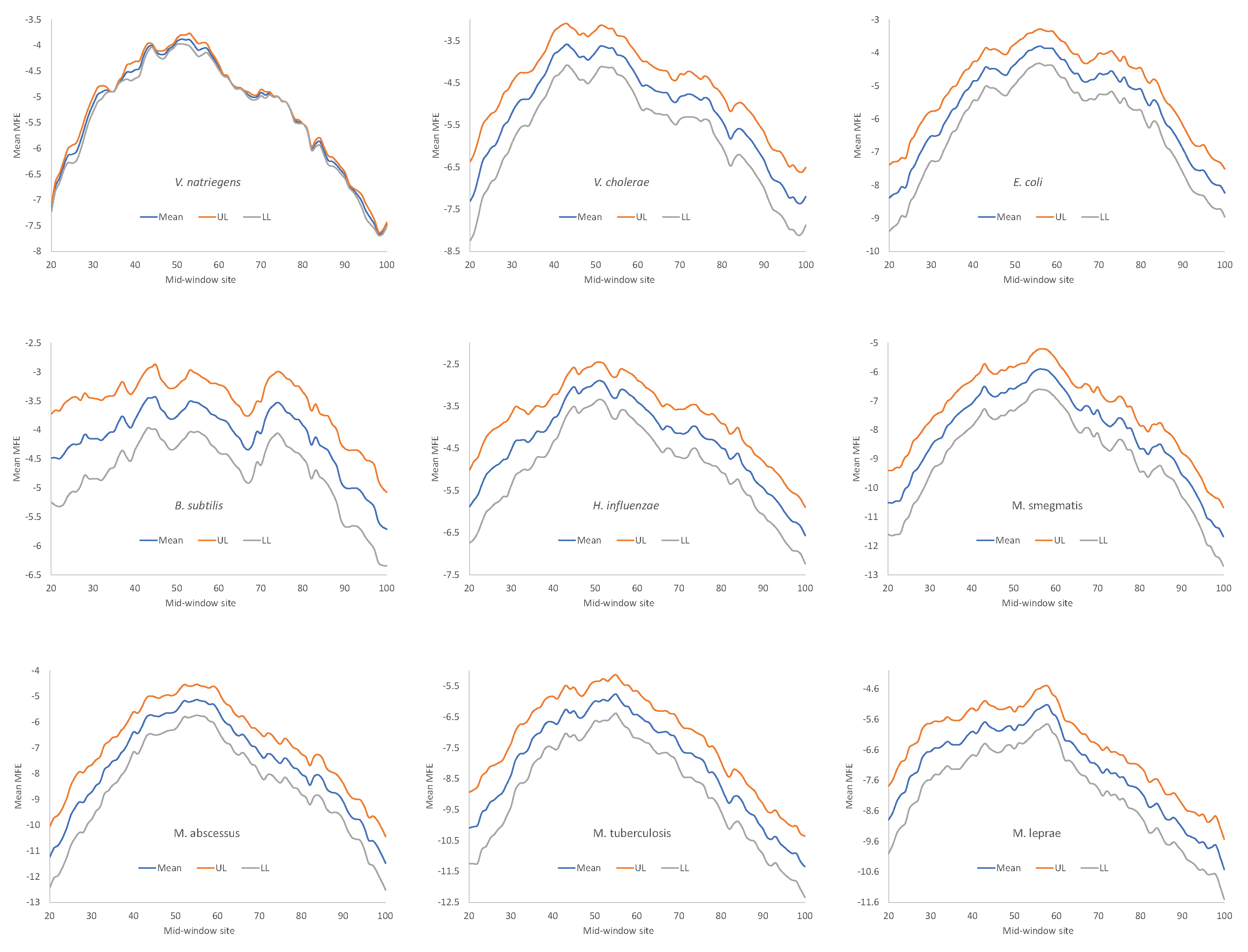

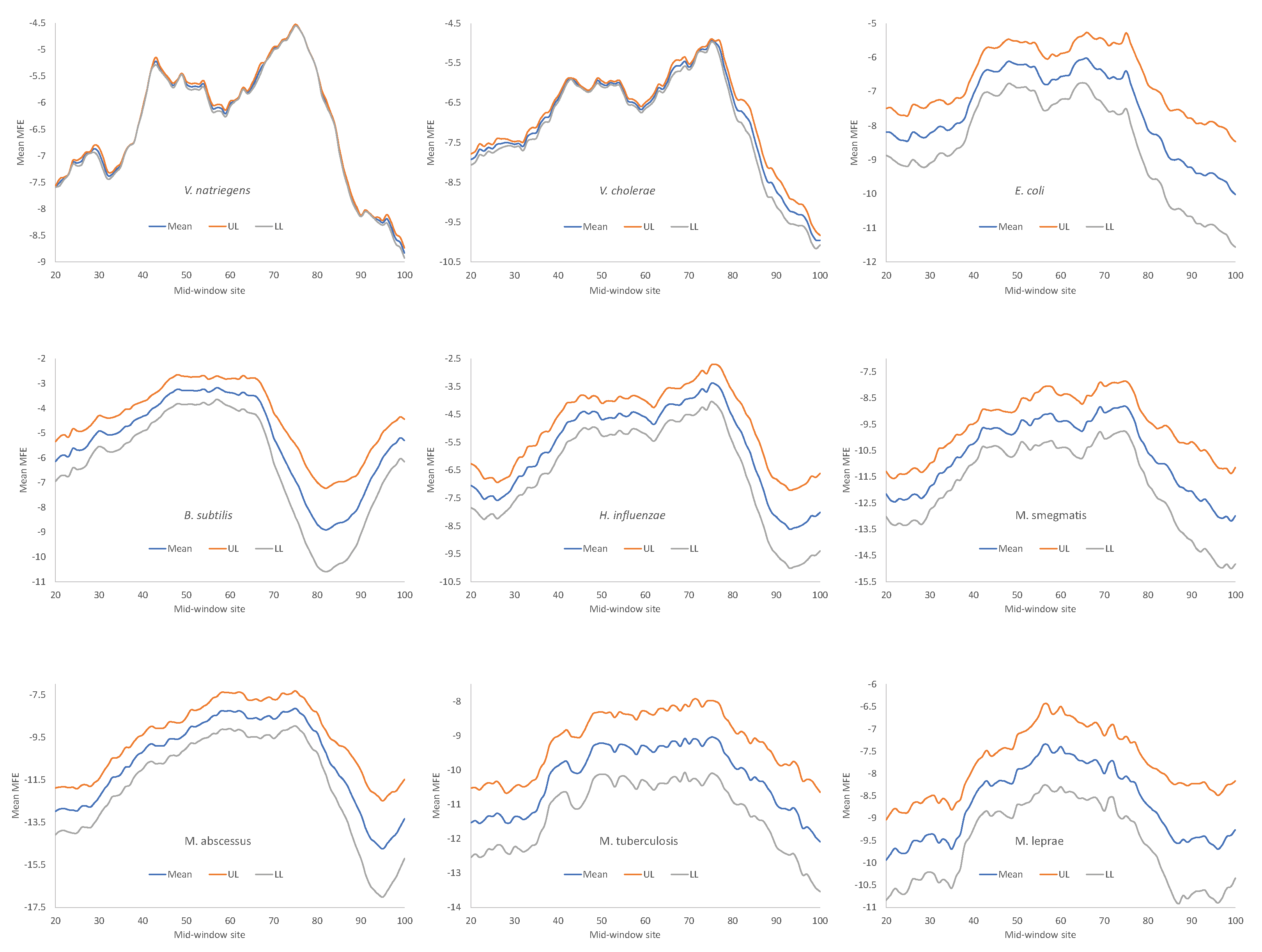

Secondary structure stability, as measured by MFE, decreases near the start codon, but the weakest secondary structure is observed slightly upstream of the start codon (

Figure 4), corresponding to the SD sequence. This pattern has been observed before in bacteriophage genes and their host genes [

5,

9,

15], and is consistent with the interpretation that a strong secondary structure embedding the SD sequence or the start codon is selected against because it prevents the translation initiation signal (SD and start codon) from being decoded by the aSD sequence and the initiation tRNA, respectively.

One might argue against the interpretation that the reduced secondary structure near the translation initiation is to avoid embedding crucial translation initiation signals such as SD sequences and start codons in a stable secondary structure. The SD sequences are purine-rich and cannot form a secondary structure within them. Thus, the reduced secondary structure near the SD sequence (

Figure 4) is a direct consequence of the purine-richness in the SD sequences, with nothing to do with the hypothesized avoidance of secondary structure embedding important translation initiation signals. To test this possibility, we simulated equivalent sequences with a purine-rich core about 10 nt upstream of the start codon, with the rest of the upstream sequences randomly drawn from a nucleotide pool derived from intergenic sequences. The result (not shown) does not support this possibility. The purine-rich core decreases the secondary structure stability only negligibly.

All nine bacterial species exhibited decreased secondary structure (

Figure 4), and the minor differences in MFE among species are not straightforward to interpret, partly because MFE is strongly affected by GC content, i.e., stronger secondary structure with higher GC content in mRNA. As we can see from

Table 9,

H. influenzae has the lowest genomic GC% (38.2%), and its mean MFE is the closest to 0 (which means no secondary structure). In contrast,

M. smegmatis and

M. tuberculosis have the highest genomic GC%, and their mRNAs tend to have more negative MFE values (

Figure 4). For this reason, without controlling for GC%, the observation that the LGB have a stronger secondary structure than the SGB cannot be attributed to a reduced selection in these LGB against stable secondary structure.

Given that a weak secondary structure near the SD sequence and the start codon is favorable (

Figure 4), one would predict that SGB should have weaker secondary structures (larger MFE values) than LGB. In order to test this prediction, we characterized the MFE plot of sliding windows for each species by a single value. That is, for each plot in

Figure 4, we calculated the mean value for mid-window-sites 46-65 (with the start codon occupying sites 58-60). These sites should include both the SD sequence and the start codon. The mean MEF (

Table 9) is now the dependent variable. It is expected to 1) decrease with increasing generation time (RankGT), 2) decrease with increasing GC%, and 3) change with gene expression (GE, i.e., be greater for HEGs than for REST genes). These three independent variables are also included in

Table 9.

The best model, which accounts for 98.2% of the total variation in MeanMFE in

Table 9, includes the three dependent variables and an interaction term (

Table 10). The two-tailed p for RankGT is 0.064 (

Table 10). However, because we have an explicit one-tailed prediction of a negative slope (i.e., MeanMFE should decrease with increasing RankGT), p should be half of 0.064, i.e., 0.032. Other regression terms for GC%, GE and their interaction are highly significant (

Table 10).

As before, we write the two regression equations separately for HEGs and REST from regression coefficients in

Table 10:

Eqs. (8) and (9) show that, for both HEGs and REST genes, secondary structure stability increases with generation time (MFE becomes more negative with increasing generation time). This is consistent with our prediction that selection against secondary structure near the translation start signals (SD sequence and start codon) is stronger in SGB than LGB.

MeanMFE decreases more sharply with GC% in Eq. (9) than in Eq. (8), i.e., secondary structure stability increases more rapidly with GC% for the REST genes than for HEGs. This is easy to understand if the selection against secondary structure stability is on average stronger in HEGs than in REST genes. MeanMFE decreases by only 0.10038 (Eq. 8) for an increase of GC% by 1% with the strong selection in HEGs, but decreases by 0.21009 (Eq. 9) for the same change in GC% with the relatively weak selection in REST genes.

The selectionist interpretation above does not consider the effect of mutations which offers an alternative interpretation. In general, spontaneous mutations in AT-rich genomes tend to be AT-biased, based on comparison between pseudogenes and their functional counterparts [

127,

128], on mutation pattern of pathogenic bacteria with relaxed selection [

129,

130], and on nucleotide bias at the three codon sites across multiple bacterial species [

131].

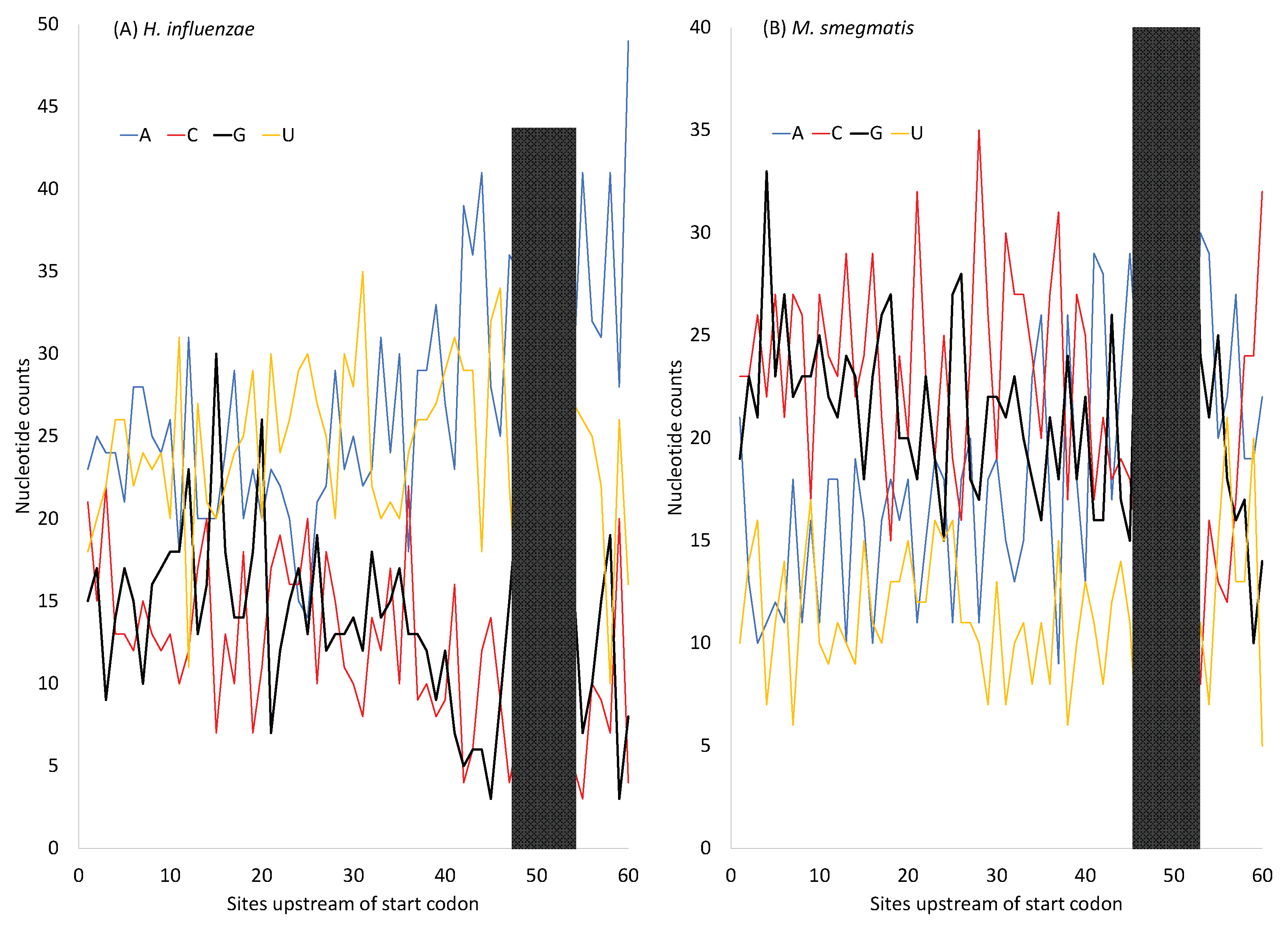

H. influenzae has an AT-rich genome, suggesting AT-biased mutation, in contrast to

M. smegmatis which has a GC-rich genome. However, protein-coding genes in both species have SD sequences that are purine-rich (especially G-rich) (

Figure 5). The G-rich SD will form base pairs with nearby C nucleotides so MFE will not go to 0. In pseudogenes where selection for maintaining the G-rich SD sequence is absent or in lowly expressed genes where the selection is weak, the AT-rich

H. influenzae will lose these G nucleotides in the SD sequence, leading to an MFE closer to 0. Indeed, the MeanMFE value for the 19 pseudogenes in

H. influenzae -2.2887, closer to 0 than all MeanMFE values in

Table 9. Similarly, the MeanMFE is -3.2660 for HEGs and -2.5466 for REST genes (

Table 9). This is consistent with the interpretation that the G-rich SD is more likely to be hit by G→A and G→T mutations and lose G/C base pairs in REST genes than in HEGs. For example,

H. influenzae has a GC% of 37.9329% for HEGs but only 33.7986% for REST genes, leading to a MeanMFE value closer to 0 in REST genes than in HEGs.

In short, although the purine rich SD sequences (

Figure 5) can hardly form secondary structures within itself, the dramatically increased G nucleotides within the SD sequence could base-pair with the neighboring C nucleotides and contribute to secondary structure stability. If there is no selection maintaining the G-richness in the SD sequences, then these G nucleotides may be replaced by A and T, leading to a further decrease in secondary structure stability. Thus, both selection and mutation could contribute to secondary structure stability in sequences near the translation initiation signals (the SD sequence and the start codon). The models in Eqs. (8) and (9) are therefore oversimplified and should be interpreted with caution. The secondary structure in sequences near the stop codon exhibits a similar pattern as those near the start codon (

Figure 6).

The decrease in secondary structure stability may not necessarily be related to the avoidance of embedding SD sequences and start codons. Efficiently translated yeast mRNAs (i.e., mRNAs in polysomes with high ribosome density) often have a short poly(A) tract before the start codon [

125], with the poly(A) interpreted as long enough to recruit translation initiation factors but short enough to avoid binding by the poly(A)-binding proteins. However, the presence of poly(A) also weakens the secondary structure stability as a secondary consequence.