1. Introduction

In the high-income countries cervical disc herniation (CDH) and degenerative cervical spondylosis (DCS) represent common clinical conditions determining pain and functional impairment. While neurological deficits represent indications for surgery, conservative management is usually the first line of treatment in case of painful conditions providing progressive functional impairment [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6].

At the clinical examination the patient may report cervical and/or brachial pain, sensory disfunction consisting of paresthesia or dysesthesia in a single- or multiple radicular territories, some grade of impairment of hands and fingers movements, and restricted range of motion of the neck, while the physician can objectivize neurological signs of myelopathy or nerve roots palsy.

Conservative management consists of physical therapy protocols and medications aiming to reduce the pain rate, while restoring the functional status. Conventionally, this strategy is pursued for 3- to 6-months before considering surgical interventions, according to the neurological status [

7,

8].

In case of neurological deterioration or failure of conservative treatment, surgery is discussed as an option with patients. During the last two decades anterior approaches to the cervical spine have been progressively preferred to posterior ones, according to the clinical-radiological outcome and complications rate. Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (ACDF) has become the standard surgical procedure for cervical disc herniation over time, progressively supplanting the anterior cervical discectomy (ACD), which was related to higher risks of segmental kyphosis and post-operative cervical pain [

1,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

9].

The mostly reported risks related to ACDF are surgical site infections, perioperative hematoma, inferior laryngeal nerve palsy, dysphagia, esophageal lesions, implant failure, and adjacent segment disorder/disease [

3,

4,

7,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. Nonetheless, it is commonly experienced by surgeons that after surgery these patients report interscapular pain, which is usually self-recovering in few weeks up to two months [

16]. However, patients frequently complain about this symptom, which is usually not reported preoperatively, and poorly discussed as a postoperative complication eventually affecting the quality of life until solved.

The present investigation aims to identify any risk factor for developing interscapular pain after ACDF for CDH or CDS.

2. Materials and Methods

Study Design

The present study is a retrospective investigation conducted at a single academic institution. Patients enrolled signed an informed consent form, that included the authorization for their anonymous data analysis for scientific purposes. The IRB approved the retrospective data collection with the following protocol registration number – Prot. 3195/2024.

The institutional database was screened for patients admitted with the diagnosis of “cervical spondylosis” and/or “cervical disc herniation” and/or “cervicalgia” and/or “brachialgia” and/or “cervical nerve root palsy” and/or “cervical myelopathy”, then filtered according to the unique surgical procedure identified for inclusion, which was “anterior cervical discectomy and fusion”.

Patients were considered for eligibility if the full medical-radiological documentation was available on the informatic system. The following inclusion criteria were adopted: age >18yo, single cervical level disc herniation determining cervical nerve root palsy and/or cervical myelopathy and/or cervical-brachial pain from 3 months after failing the conservative treatment, clinical follow-up 12 months. Exclusion criteria were history of previous cervical spine surgery or traumatic injuries prior to the current hospitalization, interscapular pain or ache at cervical-thoracic junction reported during the preoperative evaluation, fibromyalgia, oncological disease, surgical procedure different from single level ACDF without plating. A time range for screening was set from January 2019 to December 2022.

Surgical Technique

All the patients included in the present investigation were operated with the standardized institutional technique. Patients were placed supine with a gently extension of the neck on a C-shaped head holder. Shoulders were fixed to the surgical table using Tensoplast for gently lifting them caudally, without over stretching for avoiding brachial plexus injuries. The surgical approach was always performed on the left side, using a 3-to-5 cm horizontal paramedial incision exploiting a neck-skin wrinkle projecting on the target disc space, as intraoperatively verified with fluoroscopy[

17]. A standard Smith-Robinson approach was used for reaching the anterior cervical spine and a Caspar self-retaining soft-tissues retractor was placed with its tips underneath the medial aspects of the anterior longus colli muscles, properly detached from their insertion. Somatic pins (14mm) were placed and gently retracted using the Caspar self-retaining somatic retractor, avoiding any over distraction through a fluoroscopy check. Discectomy was performed under Exoscopic magnification (B-braun Aesculap), using dedicated micro instruments such as rongeur, curette, and forceps, while avoiding the use of the high-speed drill for minimizing the risk of violating and injuring the endplates. The posterior longitudinal ligament was sectioned in all the cases. A probe was used for implant sizing, aiming to identify the minimum prosthesis height capable to resist to the surgeon gently pulling after releasing the intersomatic Caspar retraction. A stand-alone Carbon implant (Brantigan – Depuy, Raynham, MA, U.S.) cage full filled by a synthetic, bioactive and osteoconductive bone void filler (Attrax Putty - Nuvasive, San Diego, CA, US) was implanted under fluoroscopic guidance [

18,

19,

20]. A subfascial drainage was always placed and removed on the first postoperative day. Cervical orthosis was never prescribed[

2,

21].

Clinical and Radiological Outcome

- -

From the dataset collection file standardized at our Department of Neurosurgery and Spine Surgery, we anonymously retrieved, for every eligible patient its demographic. Symptoms and their duration were registered at the admission, together with the ten-points itemized visual analogue scale (VAS) score for cervical and brachial pain and the mJOA score. Clinical outcome was evaluated in terms of onset of interscapular pain postoperatively and its duration, perioperative complications, and through 1-, 6-, and 12-months mJOA score calculated during outpatient follow-up.

- -

At the admission all the patients were evaluated through preoperative cervical spine CT scan and MRI, while a 1-month CT scan then cervical spine x-rays from 6 months after surgery onwards were required of all patients for assessing their radiological outcome. Level of disc herniation was usually identified on the preoperative MRI, while the disc height, defined as the distance between the upper and lower endplate measured at their middle point, the segmental zygapophyseal joint (ZAJ) distance, considered as the gap between the cortical rims of the joint measured at their middle point (mean measurement between the R and L distance),, and cervical lordosis were all calculated on pre- and postoperative CT scan. One single experienced spine surgeon performed all the measurements on the institutional Picture archiving and communication system (PACS).

Statistics and Data Analysis

Values were reported as mean ± standard deviation. The Student t-test was used to compare the quantitative continuous variables. Fisher’s exact test (2-sided) was used to compare categorical variables. Statistical significance was predetermined at an alpha level of 0.05. Univariate and multivariate multiple regression analyses were performed. StatPlus (AnalystSoft Inc.) was used for data analysis.

3. Results

Patient Demographics

The institutional dataset was screened according to the selection criteria from the methods section. A total of 113 patients were eligible for the present study, 72 were excluded according to the aforementioned criteria (29 diagnosis, 27 incomplete clinical-radiological documentation, 16 surgical procedure). A total of 31 patients were included in the present investigation. The mean age was 57.6 ± 10.8 years, the M:F ratio was 2.1 (21M:10F), 7 out of the 31 patients were smokers (22.6%), diabetes was reported in 5 patients (16.1%).

Brachialgia was reported by 20 patients (64.5%), cervicalgia by 9 (29%), and cervical-brachialgia by 6 (19.4%). Preoperative mean VAS-arm was 7.15 ± 0.81 among the 20 patients reporting brachialgia, and mean VAS-neck was 4.36 ± 1.43 among those 9 patients reporting cervicalgia. Cervical myelopathy was diagnosed in 7 patients (22.6%), 3 suffering from brachialgia (9.68%) and 4 suffering from cervicalgia (12.9%).

Mean preoperative duration of symptoms (cervicalgia and/or brachialgia) was 7,04 ± 2,68 months, while the mean mJOA score at the admission among the 7 patients with myelopathy was 14.29 ± 1.60. – see

Table 1

Surgical Data

The operated cervical levels were C3-4 in 4 (12.9%) patients, C4-5 in 12 (38.7%) patients, C5-6 in 10 (32.3%) patients, and C6-7 in 5 (16.1%) patients. Implants height was 5mm in 15 patients, 6mm in 14, and 7mm in 2. The standard width/depth size (15x12mm) was used in all the cases. No intraoperative complications were recorded.

Clinical Outcome

In one patient the intradermic suture failed in 2 days and re-suturing was needed. Postoperative pain at surgical site was reported by 5 patients, but it self-recovered in 24h, while 8 patients complained dysphagia, although not limiting solid or liquids deglutition and self-recovering within 7 days in all of them. There were no cases of postoperative dysphonia, surgical site infection, or implant failure in this series. Interscapular pain arose in 17 cases (54.8%). In 4 out of the 17 patients this symptom developed within 24 hours from the surgical procedure, while in the other 13 it was reported on the second or third postoperative day. One month after surgery mean VAS-arm score among patients with preoperative brachialgia was 2.7 ± 0.92, mean VAS-neck score among those with cervicalgia was 1 ± 1.10, while interscapular pain was still present in 8 out of the 17 patients who experienced it postoperatively.

Six-months after surgery, mean VAS-arm score among patients with preoperative brachialgia was 0.25 ± 0.44, mean VAS-neck score among those ones with preoperative cervicalgia was 0.27 ± 0.9,while mean mJOA score among myelopathic patients was 15 ± 1.73. Postoperative interscapular pain was no longer reported by any patient and those who suffered from it declared that it self-recovered within two months after surgery.

At twelve-months follow-up mean VAS-arm score among patients preoperatively suffering from brachialgia was 0.1 ± 0.45, while mean VAS-neck among those complaining for cervicalgia at the admission was 0.27 ± 0.91. The mean mJOA score among myelopathic patients was 15.43 ± 0.72. – see

Table 2.

Radiological Outcome

The mean cervical lordosis was 24.13° ± 3.37° preoperatively and 24.65° ± 2.52° postoperatively, with no significative differences between pre- and postoperative values (p=0,50).

The mean disc space height at the disc herniation level was 5.19mm ± 0.32 in those patients who had experienced postoperative interscapular pain and 5.02mm ± 0.43 in those who did not. No significative differences existed between the two subgroups in terms of preoperative disc height (p=0,22).

After surgery the mean disc height at the operated level was 5.46mm ± 0.48, with a significative increase compared to preoperative measurement (p<0,01). The subgroup analysis showed that the mean postoperative disc height in patients reporting interscapular pain was 5.71mm ± 0.44, showing a significative improvement compared to their mean preoperative height (p<0,01). A mean height of 5,15mm ± 0,32 was measured among those patients not reporting interscapular pain, showing no significative differences when compared to preoperative measurements (p=0,49).

At the admission the mean ZAJ distance at the disc herniation level was 1,05mm ± 0.14 in those patients who had experienced postoperative interscapular pain and 0,99mm ± 0.13 in those who did not. No significative differences existed between the two subgroups in terms of preoperative ZAJ mean distance (p=0,23).

The mean postoperative ZAJ distance was 1.22mm ± 0.20, with a significative increase compared to the preoperative measurement (p<0,01). The subgroup analysis showed that the mean postoperative ZAJ distance in patients reporting interscapular pain was 1.36mm ± 0.14, showing a significant improvement compared to their mean preoperative height (p<0,01), and a mean height of 1,05mm ± 0,11 among those who did not report interscapular pain, showing no significative differences when compared to preoperative measurements (p=0,20).

No mobilizations of the implants were detected at follow-up, while fusion of the treated level was appreciated in all the patients at the 12-month x-rays. – see

Table 3.

4. Discussion

Cervical disc herniation represents a common cause of disability, due to painful conditions and/or neurological impairment. High-income countries are burdened by CDH direct and indirect costs related to disability, specialistic evaluations, diagnostic, hospitalization, surgeries, rehabilitation, and sick leaves. Therefore, there is a high medical and social interest in identifying any factor for ameliorating clinical outcomes of these patients [

22].

Cervical nerve root palsy, cervical and/or arm pain resistant to conservative strategies, and cervical myelopathy are generally accepted as indications for surgery in case of cervical disc herniation[

7].

Other than surgical-related peri- and postoperative complications, patients are particularly demanding to manage especially for postoperative pain rate and early functional recover, despite the current minimally invasive techniques and medical-anesthesiologic advancements. Accordingly, physicians are also required to minimize the postoperative discomfort, therefore the identification of factors potentially affecting patients’ postsurgical comfort, satisfaction, and early functional restoration should be identified and conceived as part of the treatment itself [

9,

23].

It is commonly experienced by spine surgeons that postoperative interscapular pain may occur in patients undergoing ACDF procedures. This localized ache usually outbreaks within the first 48-72h after surgery, and it may negatively influence the early outcome, forcing to bed rest and discouraging mobilization[

16]. This painful condition is usually poorly responsive to common medications, such as NSAIDs and painkillers, while normally self-recovers within 2 months after surgery. Although patients often fully improve from preoperative symptoms, they complain about the interscapular pain that was not present at the admission and may eventually counteract the postoperative overall amelioration.

The present retrospective investigation aimed to identify any potential factor influencing the onset of interscapular pain after elective ACDF for CDH. Accordingly, the retrospective study was design for retrieving demographical, clinical, and radiological data of patients scheduled for elective ACDF surgery in a time range of 3 years at a single Academic Hospital. The minimum follow-up for inclusion was set at 1 year according to the characteristics of the assessed condition.

The primary outcome of this study was to evaluate the incidence of postoperative interscapular pain and any possible factor independently increasing the chances for experiencing it.

Postsurgical interscapular pain was experienced and reported by 17 (54.8%) out of the 31 included patients. In all cases it appeared in the first 3 days after surgery: 4 cases in 24h, 14 cases in the subsequent 48h. All the patients reported a spontaneous resolution of the interscapular discomfort within 1 month (9 patients) or 2 months (8 patients).

The analysis of demographical data showed that neither age, gender, smoking status, nor diabetes influenced the onset of postoperative interscapular pain. Nonetheless, baseline clinical data, such as type of pain (cervicalgia and/or brachialgia) and its intensity (VAS-neck and VAS-arm), symptoms duration, and severity of myelopathy were not identified as factors influencing interscapular pain appearance after surgery.

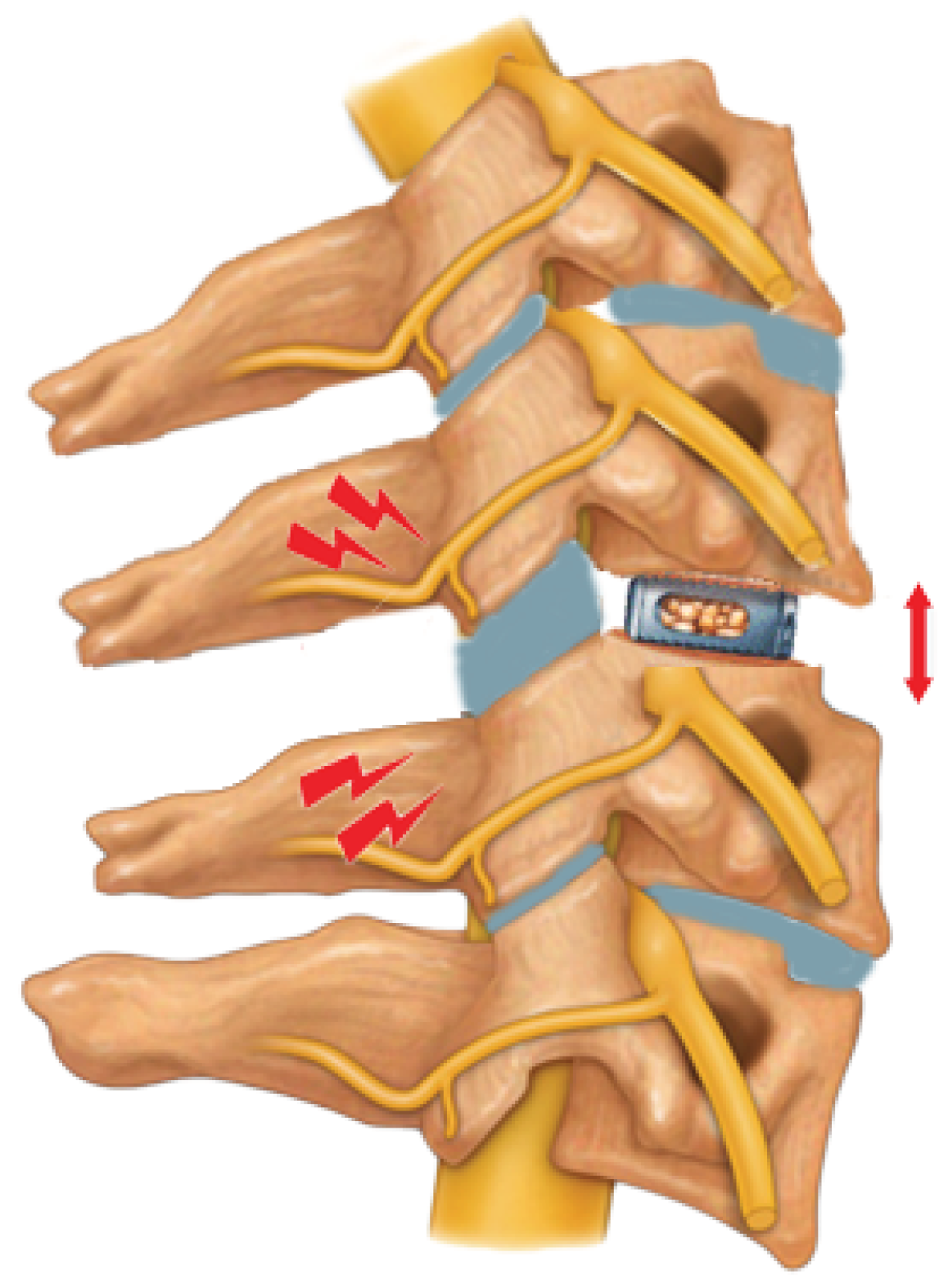

Contrarywise, going through the radiological data, while the pre- to postoperative variation of the disc space height at the operated level and cervical lordosis variation were not independently associated with the postoperative interscapular pain, our study revealed how the over-distraction of the segmental zygapophyseal joints at the operated level may represent a higher risk for developing post-operative interscapular pain. – See

Figure 1.

The implant of a cage (red arrow) which determine the posterior over distraction of the homo-segmental zygapophyseal joints (red bolts) may underlay the pathogenesis of the postoperative interscapular pain, as we found in the multivariate analysis of the raw data from this case series.

The pre-to-postoperative cervical lordosis modification was not statistically significative, and it was not associated to the postoperative interscapular pain according to the linear regression analysis.

The critical analysis of this results seems to suggest that a single factor may play a major role in this phenomenon, while we cannot exclude that any other factor, not evaluated in the present study, may participate in this. However, zygapophyseal joints distraction grade is not standardly evaluated after ACDF, then this could have been under noticed in previous investigations.

The rationale of our results can be easily identified in the capsular over distraction of these synovial joints, in which the nociceptive innervation of their capsules could underlay the clinical phenomenon of interscapular pain after ACDF. The etiopathogenesis of such condition could be related to the choice of cages higher than the original intersomatic space or determined by some grade of posterior distraction when operating on the anterior column. The self-recovering scenario in few weeks, instead, could be explained as the progressive spontaneous accommodation of the treated segment and a sort of compensation by the adjacent cervical levels. Nonetheless, to identify the mechanism underlaying the postoperative interscapular pain may influence the rehabilitation protocols, then a faster symptoms recovering[

12,

24].

Our radiological data suggest that few millimeters of over distraction may lead to postoperative interscapular pain, and this could be not detected using intraoperative fluoroscopy. Nevertheless, even when using an intraoperative CT, the detection of few millimeters over distraction of the posterior ZAJ should be carefully considered for evaluating implant substitution. Furthermore, the use of cages higher than the estimated original disc height is not reported to ameliorate clinical-radiological outcome. Therefore, the use of prosthetic implants fitting the space without providing segmental over distraction, then a posterior stretching of the zygapophyseal joints, should be preferred in these cases.

The standard use of intraoperative CT scan for verifying implant size and ZAJ distraction grade may reduce the risk for postoperative interscapular pain once the underlying mechanism we are hypothesizing in the present paper will be verified in future studies[

25].

Limitations

There are limitations of the present investigation that should be carefully considered for a proper interpretation of its results. Firstly, this is a retrospective study and its design influences its quality and level of evidence; secondly, our results are based on a relatively small patient sample from a single institution, eventually limiting the power of the analysis; thirdly, the primary outcome (postoperative interscapular pain) was retrieved from the clinical documentation and outpatient follow-up, while it is not part of any standard form, then we should consider that some patients may experience it without reporting to the physician and could have not been specifically asked for it; lastly, there is not a score for interscapular pain, and we were able to retrieve only its presence/absence in a dichotomous manner.

5. Conclusions

Postoperative interscapular pain after ACDF is commonly experienced by patients, although this is poorly discussed as a complication while commonly considered as a transitory consequence. Nonetheless, this may affect the postoperative surgery-related quality of life, eventually affecting patients’ satisfaction and functional restoration after surgery, regardless of preoperative symptoms regression. Our data suggest that ZAJ distraction may underly this symptomatology which usually recover within two months. Intraoperative CT scan for properly evaluating implant size and local anatomy modification might prevent this painful consequence. Further properly designed prospective studies are needed for validating our results.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.R. and G.L.; methodology, D.B., A.P., and L.Z.; software, A.M., and S.T.; validation, G.L.; formal analysis,L.R.; investigation,L.R., N.N., L.Z, and G.L.; data curation,N.N., and E.B.; writing—original draft preparation,L.R..; writing—review and editing, D.B., S.T., and G.L.; visualization, A,P., and E.B.; supervision, L.R., and G.L..All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of AOU Sant’Andrea di Roma (protocol code X Prot. 3195/2024.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be provided on request after the approval of the local IRB for data sharing.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sahai, N.; Changoor, S.; Dunn, C.J.; Sinha, K.; Hwang, K.S.; Faloon, M.; Emami, A. Minimally Invasive Posterior Cervical Foraminotomy as an Alternative to Anterior Cervical Discectomy and Fusion for Unilateral Cervical Radiculopathy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2019, 44, 1731–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricciardi, L.; Scerrati, A.; Olivi, A.; Sturiale, C.L.; De Bonis, P.; Montano, N. The Role of Cervical Collar in Functional Restoration and Fusion after Anterior Cervical Discectomy and Fusion without Plating on Single or Double Levels: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur Spine J 2020, 29, 955–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montano, N.; Ricciardi, L.; Olivi, A. Comparison of Anterior Cervical Decompression and Fusion versus Laminoplasty in the Treatment of Multilevel Cervical Spondylotic Myelopathy: A Meta-Analysis of Clinical and Radiological Outcomes. World Neurosurg 2019, 130, 530–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shangguan, L.; Ning, G.-Z.; Tang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Luo, Z.-J.; Zhou, Y. Discover Cervical Disc Arthroplasty versus Anterior Cervical Discectomy and Fusion in Symptomatic Cervical Disc Diseases: A Meta-Analysis. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0174822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byvaltsev, V.A.; Stepanov, I.A.; Riew, D.K. Mid-Term to Long-Term Outcomes After Total Cervical Disk Arthroplasty Compared With Anterior Diskectomy and Fusion: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Clin Spine Surg 2020, 33, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavras, A.G.; Federico, V.P.; Butler, A.J.; Nolte, M.T.; Dandu, N.; Phillips, F.M.; Colman, M.W. Relative Efficacy of Cervical Total Disc Arthroplasty Devices and Anterior Cervical Discectomy and Fusion for Cervical Pathology: A Network Meta-Analysis. Global Spine J 2024, 14, 322–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Zheng, B.; Zhang, L.; Wang, W. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Compare Surgical Treatment and Conservative Treatment in Patients with Cervical Spondylotic Myelopathy. Ann Palliat Med 2021, 10, 7671–7680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atalay, B.; Gadjradj, P.S.; Sommer, F.S.; Wright, D.; Rawanduzy, C.; Ghogawala, Z.; Härtl, R. Natural History of Degenerative Spondylolisthesis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. World Neurosurg 2023, 176, e634–e643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goh, G.S.; Yue, W.-M.; Guo, C.-M.; Tan, S.-B.; Chen, J.L.-T. Does the Predominant Pain Location Influence Functional Outcomes, Satisfaction and Return to Work After Anterior Cervical Discectomy and Fusion for Cervical Radiculopathy? Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2021, 46, E568–E575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quinto, E.S.; Paisner, N.D.; Huish, E.G.; Senegor, M. Ten-Year Outcomes of Cervical Disc Arthroplasty Versus Anterior Cervical Discectomy and Fusion : A Systematic Review With Meta-Analysis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2024, 49, 463–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takase, H.; Haze, T.; Yamamoto, D.; Inagaki, N.; Nitta, M.; Murata, H.; Yamamoto, T. Network Meta-Analysis of C5 Palsy After Anterior Cervical Decompression of Three to Six Levels: Comparing Three Different Procedures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2024, 49, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustafa, I.M.; Diab, A.A.; Harrison, D.E. The Efficacy of Cervical Lordosis Rehabilitation for Nerve Root Function and Pain in Cervical Spondylotic Radiculopathy: A Randomized Trial with 2-Year Follow-Up. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2022, 11, 6515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, J.; Moore, R.; Smith, W.; Wu, C.; Oakley, P.; Harrison, D. SYNERGISTIC TREATMENT METHODS OF STRUCTURAL REHABILITATION (CBP®) AND NEUROSURGERY MAXIMIZING PRE- AND POST-OPERATIVE CERVICAL LORDOSIS AND PATIENT OUTCOME IN CERVICAL TOTAL DISC REPLACEMENT. JCC 2022, 5, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Ricciardi, L.; Scerrati, A.; Bonis, P.D.; Miscusi, M.; Trungu, S.; Visocchi, M.; Papacci, F.; Raco, A.; Proietti, L.; Pompucci, A.; et al. Long-Term Radiologic and Clinical Outcomes after Three-Level Contiguous Anterior Cervical Diskectomy and Fusion without Plating: A Multicentric Retrospective Study. J Neurol Surg A Cent Eur Neurosurg 2021, 82, 556–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nijim, W.; Cowart, J.H.; Banerjee, C.; Postma, G.; Paré, M. Evaluation of Outcome Measures for Post-Operative Dysphagia after Anterior Cervical Discectomy and Fusion. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2023, 280, 4793–4801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, J.; Hurlbert, R.J. Discectomy versus Discectomy with Fusion versus Discectomy with Fusion and Instrumentation: A Prospective Randomized Study. Neurosurgery 2007, 61, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miscusi, M.; Bellitti, A.; Peschillo, S.; Polli, F.M.; Missori, P.; Delfini, R. Does Recurrent Laryngeal Nerve Anatomy Condition the Choice of the Side for Approaching the Anterior Cervical Spine? J Neurosurg Sci 2007, 51, 61–64. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lehr, A.M.; Oner, F.C.; Delawi, D.; Stellato, R.K.; Hoebink, E.A.; Kempen, D.H.R.; van Susante, J.L.C.; Castelein, R.M.; Kruyt, M.C. ; Dutch Clinical Spine Research Group Efficacy of a Standalone Microporous Ceramic Versus Autograft in Instrumented Posterolateral Spinal Fusion: A Multicenter, Randomized, Intrapatient Controlled, Noninferiority Trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2020, 45, 944–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehr, A.M.; Oner, F.C.; Delawi, D.; Stellato, R.K.; Hoebink, E.A.; Kempen, D.H.R.; van Susante, J.L.C.; Castelein, R.M.; Kruyt, M.C. ; Dutch Clinical Spine Research Group Increasing Fusion Rate Between 1 and 2 Years After Instrumented Posterolateral Spinal Fusion and the Role of Bone Grafting. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2020, 45, 1403–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berjano, P.; Langella, F.; Damilano, M.; Pejrona, M.; Buric, J.; Ismael, M.; Villafañe, J.H.; Lamartina, C. Fusion Rate Following Extreme Lateral Lumbar Interbody Fusion. Eur Spine J 2015, 24 (Suppl 3), 369–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricciardi, L.; Stifano, V.; D’Arrigo, S.; Polli, F.M.; Olivi, A.; Sturiale, C.L. The Role of Non-Rigid Cervical Collar in Pain Relief and Functional Restoration after Whiplash Injury: A Systematic Review and a Pooled Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Eur Spine J 2019, 28, 1821–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nin, D.Z.; Chen, Y.-W.; Kim, D.H.; Niu, R.; Powers, A.; Chang, D.C.; Hwang, R.W. Healthcare Costs Following Anterior Cervical Discectomy and Fusion or Cervical Disc Arthroplasty. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S.L.; Godil, S.S.; Shau, D.N.; Mendenhall, S.K.; McGirt, M.J. Assessment of the Minimum Clinically Important Difference in Pain, Disability, and Quality of Life after Anterior Cervical Discectomy and Fusion: Clinical Article. J Neurosurg Spine 2013, 18, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bębenek, A.; Dominiak, M.; Godlewski, B. Cervical Sagittal Balance: Impact on Clinical Outcomes and Subsidence in Anterior Cervical Discectomy and Fusion. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 3310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Battistelli, M.; Polli, F.M.; D’Alessandris, Q.G.; D’Ercole, M.; Izzo, A.; Rapisarda, A.; Montano, N. An Overview of Recent Advances in Anterior Cervical Decompression and Fusion Surgery. Surg Technol Int 2023, 43, sti43–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).