Submitted:

19 March 2024

Posted:

20 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

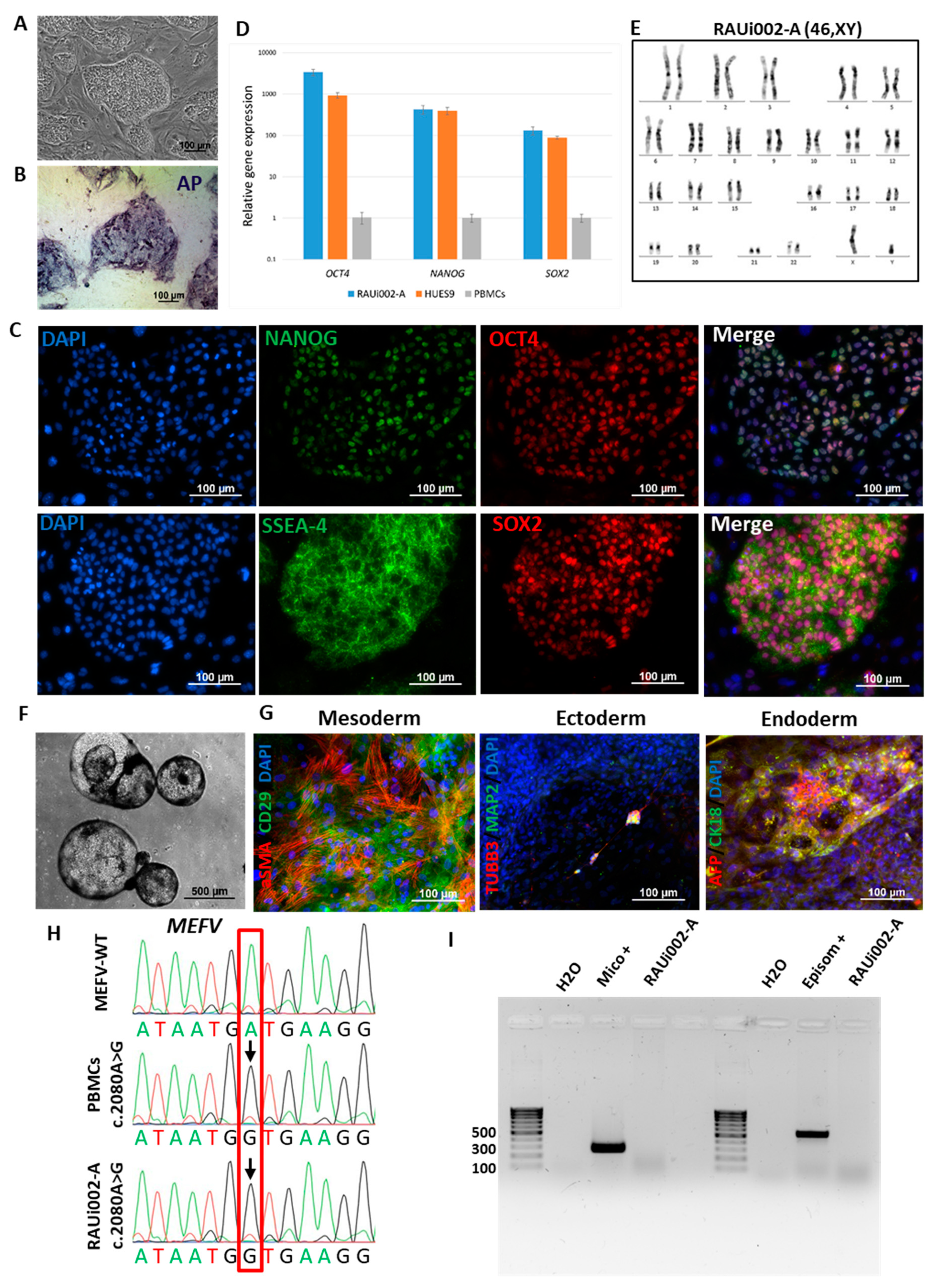

2.1. Generation and Characteristics of iPSCs Associated with the MEFV Gene Mutation

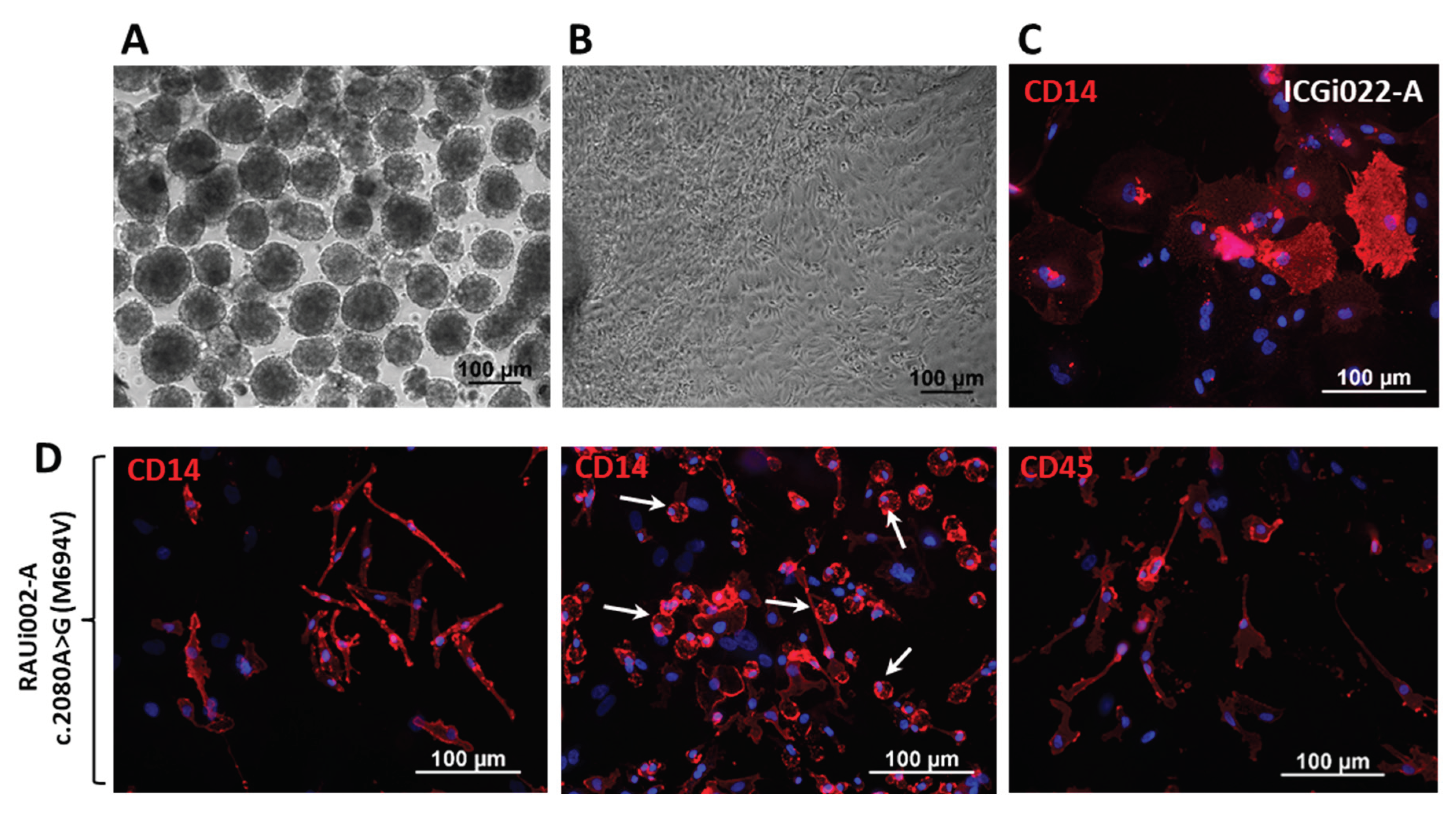

2.2. Generation and Characteristic of Macrophages from RAUi002-A iPSCs

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Ethics Statement

4.2. Detection of MEFV Mutation

4.3. Reprogramming of PBMCs into iPSCs

4.4. In Vitro Spontaneous Differentiation of RAUi002-A into Three Germ Layers

4.5. Immunofluorescent Staining of RAUi002-A iPSC Line

4.6. qPCR Analysis of Expression of Pluripotency Markers in RAUi002-A iPSC Line

4.7. Karyotyping of RAUi002-A iPSC Line

4.8. Genotyping of RAUi002-A iPSC Line

4.9. Detection of Mycoplasma and Reprogramming Vectors in RAUi002-A iPSC Line

4.10. Differentiation of RAUi002-A iPSC Line into Macrophages

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chae, J.J.; Aksentijevich, I.; Kastner, D.L. Advances in the understanding of familial Mediterranean fever and possibilities for targeted therapy. Br J Haematol. 2009, 146, 467–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Booty, M.G.; Chae, J.J.; Masters, S.L.; Remmers, E.F.; Barham, B.; Le, J.M.; Barron, K.S.; Holland, S.M.; Kastner, D.L.; Aksentijevich, I. Familial Mediterranean fever with a single MEFV mutation: where is the second hit? Arthritis Rheum. 2009, 60, 1851–1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantarini, L.; Rigante, D.; Brizi, M.G.; Lucherini, O.M.; Sebastiani, G.D.; Vitale, A.; Gianneramo, V.; Galeazzi, M. Clinical and biochemical landmarks in systemic autoinflammatory diseases. Ann Med. 2012, 44, 664–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- French FMF Consortium. A candidate gene for familial Mediterranean fever. Nat Genet. 1997, 17, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özen, S.; Batu, E.D.; Demir, S. Familial Mediterranean Fever: recent developments in pathogenesis and new recommendations for management. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sargsyan, A.; Sahakyan, H.; Nazaryan, K. Effect of colchicine binding site inhibitors on the tubulin intersubunit interaction. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 29448–29454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arakelov, G.; Arakelov, V.; Nazaryan, K. Complex formation dynamics of native and mutated pyrin's B30.2 domain with caspase-1. Proteins 2018, 86, 676–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martirosyan, A.; Poghosyan, D.; Ghonyan, S.; Mkrtchyan, N.; Amaryan, G.; Manukyan, G. Transmigration of neutrophils from patients with Familial Mediterranean fever causes increased cell activation. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 672728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkaya-Ulum, Y.Z.; Akbaba, T.H.; Tavukcuoglu, Z.; Chae, J.J.; Yilmaz, E.; Ozen, S.; Balci-Peynircioglu, B. Familial Mediterranean fever-related miR-197-3p targets IL1R1 gene and modulates inflammation in monocytes and synovial fibroblasts. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezher, N.; Mroweh, O.; Karam, L.; Ibrahim, J.N.; Kobeissy, P.H. Experimental models in Familial Mediterranean Fever (FMF): Insights into pathophysiology and therapeutic strategies. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2024, 135, 104883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Jin, T.; Jian, Sh.; Han, X.; Song, H.; Zhou, Q.; Yu, X. A dominant pathogenic MEFV mutation causes atypical pyrin-associated periodic syndromes. JCI Insight. 2023, 8, e172975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volpato, V.; Webber, C. Addressing variability in iPSC-derived models of human disease: guidelines to promote reproducibility. Dis. Model. Mech. 2020, 13, dmm042317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorringe, K.L.; Chin, S.F.; Pharoah, P.; Staines, J.M.; Oliveira, C.; Edwards, P.A.W.; Caldas, C. Evidence that both genetic instability and selection contribute to the accumulation of chromosome alterations in cancer. Carcinogenesis 2005, 26, 923–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiba, T.; Tanaka, T.; Ida, H.; Watanabe, M.; Nakaseko, H.; Osawa, M.; Shibata, H.; Izawa, K.; Yasumi, T.; Kawasaki, Y.; Saito, M.K.; Takita, J.; Heike, T.; Nishikomori, R. Functional evaluation of the pathological significance of MEFV variants using induced pluripotent stem cell-derived macrophages. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2019, 144, 1438–1441.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito, M.K. Elucidation of the pathogenesis of autoinflammatory diseases using iPS cells. Children (Basel) 2021, 8, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowe, R.G. & Daley, G.Q. Induced pluripotent stem cells in disease modelling and drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2019, 20, 377–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hew, M.; O’Connor, K.; Edel, M.J.; Lucas, M. The possible future roles for iPSC-derived therapy for autoimmune diseases. J. Clin. Med. 2015, 4, 1193–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, T.; Shiba, T.; Honda, Y.; Izawa, K.; Yasumi, T.; Saito, M.K.; Nishikomori, R. Induced pluripotent stem cell-derived monocytes/macrophages in autoinflammatory diseases. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 870535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okano, H. & Morimoto, S. iPSC-based disease modeling and drug discovery in cardinal neurodegenerative disorders. Cell Stem Cell 2022, 29, 189–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, Sh.; Jirásko, M.; Lochman, J.; Chvátal, A.; Dvorakova, M.C.; Kučera, R. iPSCs in neurodegenerative disorders: a unique platform for clinical research and personalized medicine. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigor’eva, E.V.; Malankhanova, T.B.; Surumbayeva, A.; Pavlova, S.V.; Minina, J.M.; Kizilova, E.A.; Suldina, L.A.; Morozova, K.N.; Kiseleva, E.; Sorokoumov, E.D.; et al. Generation of GABAergic striatal neurons by a novel iPSC differentiation protocol enabling scalability and cryopreservation of progenitor cells. Cytotechnology. 2020, 72, 649–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grigor’eva, E.V.; Kopytova, A.E.; Yarkova, E.S.; Pavlova, S.V.; Sorogina, D.A.; Malakhova, A.A.; Malankhanova, T.B.; Baydakova, G.V.; Zakharova, E.Y.; Medvedev, S.P.; Pchelina, S.N.; et al. Biochemical Characteristics of iPSC-Derived Dopaminergic Neurons from N370S GBA Variant Carriers with and without Parkinson’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malankhanova, T.B.; Suldina, L.A.; Grigor’eva, E.V.; Medvedev, S.P.; Minina, J.M.; Morozova, K.N.; Kiseleva, E.; Zakian, S.M.; Malakhova, A.A. A human induced pluripotent stem cell–derived isogenic model of Huntington’s disease based on neuronal cells has several relevant phenotypic abnormalities. J. Pers. Med. 2020, 10, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ustyantseva, E.; Pavlova, S.V.; Malakhova, A.A.; Ustyantsev, K.; Zakian, S.M.; Medvedev, S.P. Oxidative stress monitoring in iPSC-derived motor neurons using genetically encoded biosensors of H2O2. Sci Rep. 2022, 12, 8928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fidan, K.; Kavaklıoğlu, G.; Ebrahimi, A.; Özlü, C.; Ay, N.Z.; Ruacan, A.; Gül, A.; Önder, T.T. Generation of integration-free induced pluripotent stem cells from a patient with Familial Mediterranean Fever (FMF). Stem Cell Res. 2015, 15, 694–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malakhova, A.A.; Grigor’eva, E. V.; Pavlova, S. V.; Malankhanova, T.B.; Valetdinova, K.R.; Vyatkin, Y. V.; Khabarova, E.A.; Rzaev, J.A.; Zakian, S.M.; Medvedev, S.P. Generation of induced pluripotent stem cell lines ICGi021-A and ICGi022-A from peripheral blood mononuclear cells of two healthy individuals from Siberian population. Stem Cell Res. 2020, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okita, K.; Yamakawa, T.; Matsumura, Y.; Sato, Y.; Amano, N.; Watanabe, A.; Goshima, N.; Yamanaka, S. An efficient nonviral method to generate integration-free human-induced pluripotent stem cells from cord blood and peripheral blood cells. Stem Cells. 2013, 31, 458–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savran, Y.; Sari, I.; Kozaci, D.L.; Gunay, N.; Onen, F.; Akar, S. Increased levels of macrophage migration inhibitory factor in patients with Familial Mediterranean Fever. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2013, 10, 836–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, M.W.; Ting, C.Y.; Chan, D.Z.H.; Cheng, Y.; Lee, Y.; Hsu, C.; Huang, C.; Hsieh, P.C.H. Utility of iPSC-derived cells for disease modeling, drug development, and cell therapy. Cells 2022, 11, 1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamberlain, S.J. Disease modelling using human iPSCs. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2016, 25, R173–R181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csöbönyeiová, M.; Polák, S.; Danišovič, L. Perspectives of induced pluripotent stem cells for cardiovascular system regeneration. Exp. Biol. Med (Maywood). 2015, 240, 549–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rikhtegar, R.; Pezeshkian, M.; Dolati, S.; Safaie, N.; Rad, A.A.; Mahdipour, M.; Nouri, M.; Jodati, A.R.; Yousefi, M. Stem cells as therapy for heart disease: iPSCs, ESCs, CSCs, and skeletal myoblasts. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 109, 304–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrotta, E.I.; Lucchino, V.; Scaramuzzino, L.; Scalise, S.; Cuda, G. Modeling cardiac disease mechanisms using induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes: progress, promises and challenges. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danisovic, L.; Culenova, M.; Csobonyeiova, M. Induced pluripotent stem cells for Duchenne muscular dystrophy modeling and therapy. Cells 2018, 7, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoda, H.; Natsumoto, B.; Fujio, K. Investigation of immune-related diseases using patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells. Inflamm. Regen. 2023, 43, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monkley, S.; Krishnaswamy, J.K.; Göransson, M.; Clausen, M.; Meuller, J.; Thörn, K.; Hicks, R.; Delaney, S.; Stjernborg, L. Optimised generation of iPSC-derived macrophages and dendritic cells that are functionally and transcriptionally similar to their primary counterparts. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0243807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigor’eva, E.V.; Malakhova, A.A.; Ghukasyan, L.; Hayrapetyan, V.; Atshemyan, S.; Vardanyan, V.; Zakian, S.M.; Zakharyan, R.; Arakelyan, A. Generation of three induced pluripotent stem cell lines (RAUi001-A, RAUi001-B and RAUi001-C) from peripheral blood mononuclear cells of a healthy Armenian individual. Stem Cell Research. 2023, 71, 103147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choppa, P.C.; Vojdani, A.; Tagle, C.; Andrin, R.; Magtoto, L. Multiplex PCR for the detection of mycoplasma fermentans, M. hominis and M. penetrans in cell cultures and blood samples of patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. Mol. Cell. Probes. 1998, 12, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilgenburg, B.; Browne, C.; Vowles, J.; Cowley, S.A. Efficient, long term production of monocyte-derived macrophages from human pluripotent stem cells under partly-defined and fully-defined conditions. PLoS One. 2013, 8, e71098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Classification | Test | Result | Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| Morphology | Photography Bright field | Normal | Figure 1A |

| Pluripotency status | Qualitative analysis: Alkaline phosphatase staining | Positive | Figure 1B |

| Qualitative analysis: Immunocytochemistry | Positive staining for pluripotency markers: OCT3/4, SOX2, NANOG, SSEA-4 | Figure 1C | |

| Quantitative analysis: RT-qPCR | Expression of pluripotency markers: NANOG, OCT4, SOX2 | Figure 1D | |

| Genotype | Karyotype (G-banding) | 46,XY | Figure 1E |

| Mutation analysis | Sanger sequencing of DNA from patient's PBMCs and iPSCs | Homozygous p.M694V (c.2080A>G, rs61752717) in exon 10 of the MEFV gene | Figure 1H |

| Differentiation potential | Embryoid body formation | Positive staining for germ layer markers: ɑSMA and CD29 (mesoderm); MAP2 and TUBB3/TUJ1 (ectoderm); CK18/AFP (endoderm) | Figure 1G |

| Specific pathogen-free status | Mycoplasma | Negative | Figure 1I |

| Antibodies used for immunocytochemistry | |||

| Antibody | Dilution | Company Cat # and RRID | |

| Pluripotency Markers | Mouse IgG2b anti-OCT3/4 (C-10) | 1:200 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA, Cat# sc-5279, RRID:AB_628051 |

| Mouse IgG3 anti-SSEA-4 | 1:200 | Abcam, Cambridge, UK, Cat# ab16287, RRID:AB_778073 | |

| Mouse IgG1 anti-NANOG | 1:200 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA, Cat# sc-293121, RRID:AB_2665475 | |

| Rabbit IgG anti-SOX2 | 1:500 | Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, USA, Cat# 3579, RRID:AB_2195767 | |

| Differentiation Markers | Mouse IgG2a anti- αSMA | 1:100 | Dako, Glostrup, Denmark, Cat# M0851, RRID:AB_2223500 |

| Mouse IgG1 anti-CD29 (Integrin beta 1) (TS2/16) | 1:100 | Thermo Fisher Scientific,Waltham, MA, USA, Cat # 14-0299-82, RRID:AB_1210468 | |

| Mouse IgG2a anti-AFP | 1:250 | Sigma-Aldrich, Darmstadt, Germany,Cat# A8452, RRID:AB_258392 | |

| Mouse IgG2a anti-Tubulin β 3 (TUBB3)/ Clone: TUJ1 | 1:1000 | BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA, Cat# 801201, RRID:AB_2313773 | |

| Chicken IgG anti MAP2 | 1:1000 | Abcam, Cambridge, UK, Cat# аb5392, RRID:AB_2138153 | |

| Mouse IgG1 anti-CK18 | 1:200 | Millipore, Burlington, VT, USA Cat# MAB3234, RRID:AB_94763 | |

| Macrophage-specific Markers | Mouse IgG2b, κ anti-CD14 APC (Clone MφP9) | 1:30 | BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA, Cat# 345787, RRID:AB_2868813 |

| Mouse IgG1, κ anti-CD45 PerCP-Cy5.5 CE | 1:20 | BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA, Cat# 332784, RRID:AB_2868632 | |

| Secondary antibodies | Goat anti-Mouse IgG3 Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor 488 | 1:400 | Thermo Fisher Scientific,Waltham, MA, USA, Cat# A-21151, RRID:AB_2535784 |

| Goat anti-Mouse IgG2b Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor 568 | 1:400 | Thermo Fisher Scientific,Waltham, MA, USA, Cat# A-21144, RRID:AB_2535780 | |

| Goat anti-Rabbit IgG (H + L) Alexa Fluor 568 | 1:400 | Thermo Fisher Scientific,Waltham, MA, USA, Cat# A-11011, RRID:AB_143157 | |

| Goat anti-Mouse IgG1 Alexa Fluor 488 | 1:400 | Thermo Fisher Scientific,Waltham, MA, USA, Cat# A-21121, RRID:AB_2535764 | |

| Goat anti-Mouse IgG1 Alexa Fluor 568 | 1:400 | Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA, Cat# A21124, RRID:AB_2535766 | |

| Goat anti-Mouse IgG2a Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor 568 | 1:400 | Thermo Fisher Scientific,Waltham, MA, USA, Cat # A-21134, RRID:AB_2535773 | |

| Goat anti-Chicken IgY (H + L) Alexa Fluor 488 | 1:400 | Abcam, Cambridge, UK, Cat # ab150173, RRID:AB_2827653 | |

| Primers | |||

| Target | Size of band | Forward/Reverse primer (5′-3′) | |

| Episomal plasmid vectors detection | EBNA-1 | 61 bp | TTCCACGAGGGTAGTGAACC/ TCGGGGGTGTTAGAGACAAC |

| Mycoplasma detection | 16S ribosomal RNA gene | 280 bp | GGGAGCAAACAGGATTAGATACCCT/ TGCACCATCTGTCACTCTGTTAACCTC |

| House-keeping gene (RT-qPCR) | beta-2-microglobulin | 280 bp | TAGCTGTGCTCGCGCTACT/ TCTCTGCTGGATGACGTGAG |

| Pluripotency marker (RT-qPCR) | NANOG | 116 bp | TTTGTGGGCCTGAAGAAAACT/ AGGGCTGTCCTGAATAAGCAG |

| OCT4 | 94 bp | CTTCTGCTTCAGGAGCTTGG/ GAAGGAGAAGCTGGAGCAAA |

|

| SOX2 | 100 bp | GCTTAGCCTCGTCGATGAAC/ AACCCCAAGATGCACAACTC |

|

| Targeted mutation analysis | MEFV | 297 bp | TGGGATCTGGCTGTCACATTG/ CATTGTTCTGGGCTCTCCGAG |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).