Submitted:

15 March 2024

Posted:

18 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Specific Aims and Hypotheses

Materials and Methods

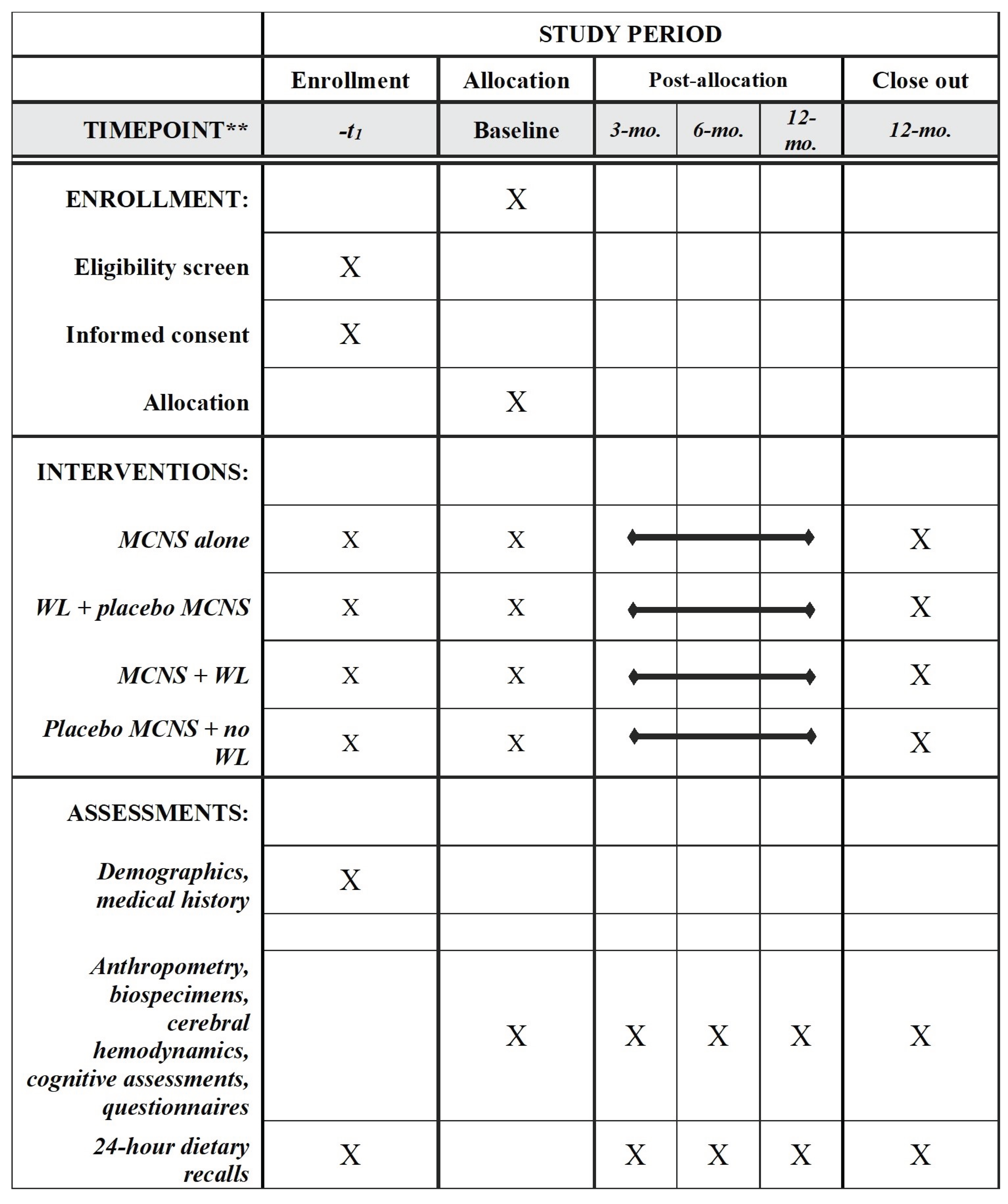

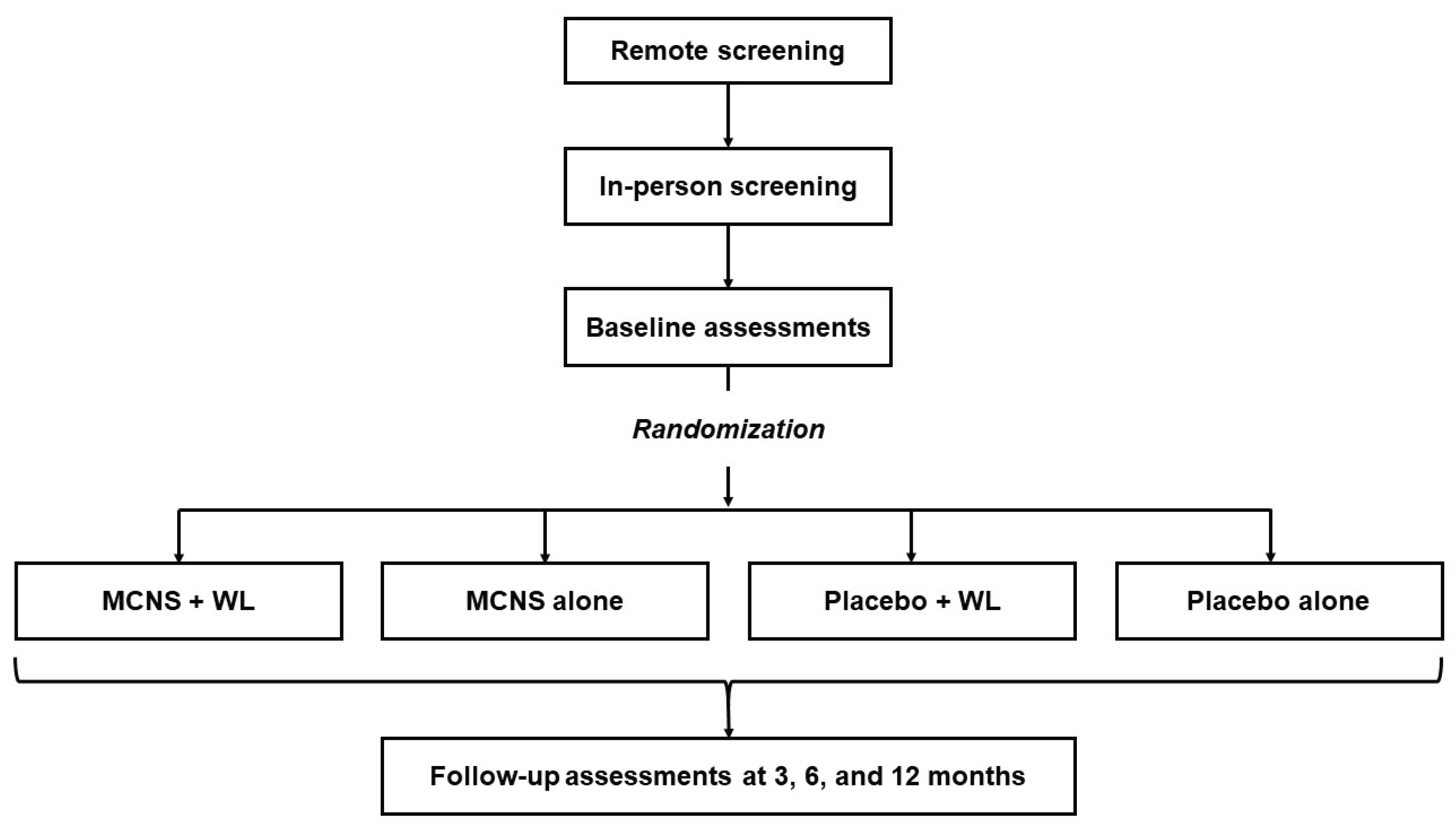

Study Design

Setting and Recruitment

Participants

Inclusion Criteria

Exclusion Criteria

Screening

Randomization and Blinding

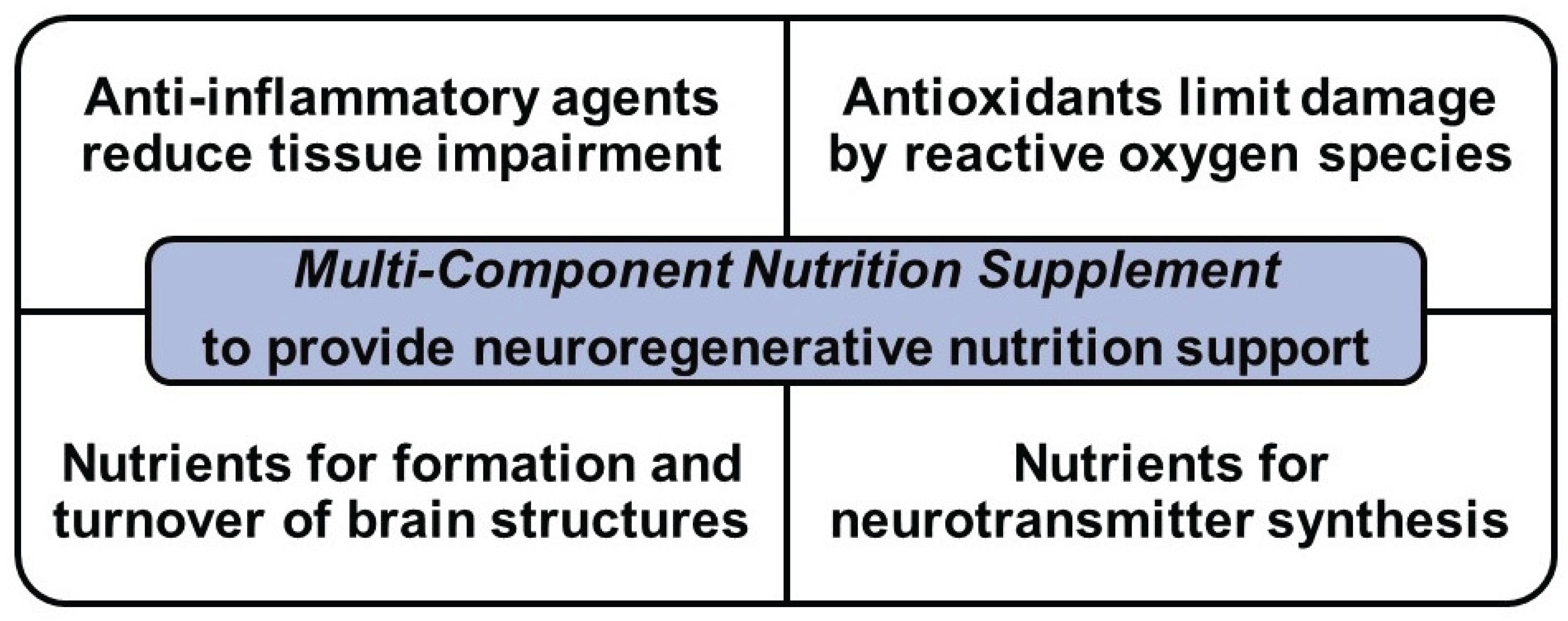

MCNS Intervention

MCNS Control

Weight Loss Intervention

Weight Loss Control

Monitoring Participant Adherence to the Administered Interventions

Data collection and Measures

Procedures and Training

Measures

| Measure | Screening | Baseline | 3-month | 6-month | 12-month |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | x | ||||

| Medical history | x | ||||

| Anthropometry | |||||

| Height (cm) | x | ||||

| Weight (kg) | x | x | x | x | x |

| Blood pressure (mmHg) | x | x | x | x | x |

| Pulse (BPM) | x | x | x | x | x |

| Biological samples | |||||

| Blood | x | x | x | x | |

| Urine | x | x | x | x | |

| Cerebral hemodynamics | |||||

| Fasted | x | x | x | x | |

| Post-prandial | x | x | x | x | |

| Cognitive assessments | |||||

| Auditory Verbal Learning Test (AVLT) | x | x | x | x | |

| Controlled Oral Word Association Test (COWAT) | x | x | x | x | |

| Single Digit Modalities Test (SDMT) | x | x | x | x | |

| Stroop Interference Test | x | x | x | x | |

| Trails Making Test (A) | x | x | x | x | |

| Trails Making Test (B) | x | x | x | x | |

| NIH Toolbox (NIH-TB) | x | x | x | x | |

| Dietary | |||||

| Multi-pass 24-hour recall | x | x | x | x | |

| Questionnaires | |||||

| 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) | x | x | x | x | |

| Adult Eating Behavior | x | x | x | x | |

| Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) | x | x | x | x | |

| Cognitive & Leisure Activity Scale (CLAS) | x | x | x | x | |

| Community Healthy Activities Model Programs for Seniors (CHAMPS) | x | x | x | x | |

| Factors Influencing Food Choice (FCQ) | x | x | x | x | |

| General Nutrition Knowledge Survey | x | x | x | x | |

| Sarason Social Support (SSQSR) | x | x | x | x | |

| Self-Regulation of Eating Behavior (SREBQ) | x | x | x | x | |

| Stigmatizing Situations Inventory | x | x | x | x | |

| Three-Factor Eating (TFEQ) | x | x | x | x | |

| Weight-Striving Stress Scale | x | x | x | x | |

| Yale Food Addiction Scale | x | x | x | x |

- Cognitive function (primary outcome). Assessments of cognitive function were derived from performance on well-established neuropsychological tests and the NIH-Toolbox cognitive module. All cognitive assessments were completed at baseline, 3 months, 6 months, and 12 months at 30 minutes postprandial. Five standardized scores from five tests were obtained and summed to yield a composite executive function z-score as the primary outcome. These tests include: Controlled Oral Word Association Test (COWAT),[70,71] Single Digit Modalities Test (SDMT),[72] Stroop Interference Test (Stroop),[73] Trails Making Test (TMTA, B).[74,75] The Auditory Verbal Learning Test (AVLT): Total Learning and Delayed Recall[76] and the NIH Toolbox (NIH-TB) will also be administered and were considered secondary outcomes. A detailed overview of the cognitive assessments is presented in Table 2. All cognitive assessments were audiotaped for quality control and proper coding of verbal tasks and were reviewed by a member of the research team.

| TEST | DOMAIN(S) ASSESSED | DESCRIPTION |

| Primary Outcomes | ||

| COWAT | Controlled response generation | Examines phonemic verbal fluency and response generation. Participants verbalize during 1-minute periods as many words as possible that begin with particular letters (e.g., H, O). The restriction of response set requires executive control and executive function for controlled response production. |

| SDMT | Working memory, focused attention, processing speed | Widely used and well standardized test speed and accuracy in the coding symbols associated with specific numbers is a highly sensitive tests of brain dysfunction. The final score is the total number of correctly entered symbols in 90 seconds. |

| Stroop | Executive inhibitory control, focused attention | Assesses the extent of slowing created by attentional interference created by the demand of naming colors that are discordant with the printed word of a different color. The score on the Color-Word interference trial is compared with scores on color word reading and color naming in the absence of interference. For each of the 3 tasks, scores are based on the number of colors correctly named in 45 seconds, with these scores computed to yield a Stroop Interference z-score. |

| TMT-A | Attention, speed of processing | Involves the use of a pencil to connect a series of numbers in ascending order that are distributed over a sheet of paper as quickly as possible. Completion time provides the performance measure that is converted to a z-score. |

| TMT-B | Attention and executive control – inhibition (set switching, processing speed) | Similar to Trail A, except that alternation of an ascending sequence between numbers and letters distributed over the page is required (e.g., 1-A-2-B…). The number-letter sequence is connected by pencil. Completion time provides the performance measure that is converted to a z-score. |

| Additional Outcomes | ||

| AVLT | Learning and memory | The AVLT is a verbal learning and memory test. A list of 15 words is presented to the participant over five trials with recall assessed immediately following each trial. Recall for these words is assessed after presentation of an interference list B after the five trials. Delayed recall of the first 15 word list is then assessed after a 15-minute interval. |

| NIH-TB | Fluid and crystalized cognitive function | The cognitive module of the NIH-TB was developed to assess fluid and crystalized cognitive functions via computerized (IPAD) administration. It takes 30-45 minutes to complete and contains seven primary tasks (Flanker Inhibitory Control and Attention Test, Dimensional Change Card Sort Test, List Sorting Test, Pattern Comparison Processing Speed Test, Picture Sequence Memory Test, Picture Vocabulary Test, and Oral Reading Test). |

- 2.

- Cerebral hemodynamics. Measures of cerebral blood flow (CBF) and oxygenation were collected at each study visit in fasted and two-to three-hours postprandial states. Microvascular CBF was measured using continuous-wave diffuse correlation spectroscopy (CW-DCS) equipped with a 785 nm laser source and four single-photon avalanche diode detectors, which provided a continuous index of blood flow (BFi).[77,78] A 3D-printed flexible sensing probe was designed with a short source-detector distance of 5 mm for scalp blood flow and two long distances of 25 and 30 mm for cerebral blood flow monitoring, which was connected to the DCS source and detectors and positioned on the subject’s forehead.[79,80,81] The DCS optical data were acquired at 150 MHz. On the opposite forehead, cerebral oxygenation was measured using near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS), an established method which measures light attenuation due to absorption of hemoglobin to non-invasively monitor hemoglobin oxygen saturation in biological tissues.[82,83] This metric was also used as a surrogate measure of cerebral blood volume (CBV) changes. The NIRS was a battery-operated headband with source-detector distances of 8, 28, and 33 mm, made of 735 and 850 nm LED light sources and photodiode detectors on a flexible printed circuit board, as originally described.[84] The NIRS data were acquired at 266 Hz. Together, DCS and NIRS provide an array of cerebral hemodynamic biomarkers that uniquely characterize brain health and function. Respiratory pattern and EKG was recorded via Biopac. The acquired data were time-synchronized using the devices’ timestamps and common trigger signals.

- 3.

- Fasting duplicate measurements of weight were taken to ±0.1 kg at each study visit. Our standard protocol[85,86] requires the use of the same calibrated scale, and removal of shoes, outer clothing, and heavy items. Brachial systolic and diastolic blood pressure were measured after weight measurements, as an index of the effects of the supplements on cardiometabolic health. Three measurements were performed after a defined rest period, with the last 2 averaged.[86] An automatic blood pressure cuff was used, with cuff sizes based on each subject’s left arm circumference.

- 4.

- Biospecimens. Fasting blood samples (25 ml) were taken at baseline, 6, and 12 months, and processed for storage in our Clinical Laboratory Improvements Amendment (CLIA)-certified laboratory. Because of anticipated changes in blood glucose and insulin sensitivity,[87] HbA1c, fasting plasma glucose and fasting serum insulin levels were measured at each timepoint. Apolipoprotein E4 (ApoE4) genotypes also influence risk of AD and were measured in our core facility.[88,89] Fasting urine samples were also collected in order to evaluate adherence to supplement consumption by assessing catechin metabolites.

- 5.

- Self-reported health outcomes via validated questionnaires. Demographic variables and family history of dementia and AD were assessed at the start of the study and updated as relevant. In addition, health-related quality of life, functional activities, sleep, depression, eating behaviors, activity and activities of daily living were assessed, using NIH-recommended instruments when available.[90,91,92,93,94,95,96] A complete list of questionnaires is included in Table 1.

- 6.

- Dietary adherence. For dietary adherence, we used the multiple-pass interviewer-administered 24-hour dietary recall method.[97] In past studies, we have achieved 90% accuracy relative to gold-standard assessments with this method.[98] Three daily recalls were performed on random days by telephone at screening (to determine if plausible records can be obtained[99]) and these data were used as baseline data for enrollees. Three recalls were collected on random days after each visit at the 3-, 6- and 12-month timepoints. The collected data includes efforts to obtain both general dietary intake information for the period of collection and specific information relevant to this study (e.g., type of chocolate consumed, if any). The records will be analyzed to quantify daily nutrient intakes and intakes of nutrients of particular interest (cocoa polyphenols, DHA+EPA, % adequacy of micronutrients relative to Dietary Reference Intakes), using Nutrition Data System for Research software (Nutrition Coordinating Center, University of Minnesota, Version 2021 or latest). Information will be used to calculate a Healthy Eating Index score[100] and a MIND diet score,[24] which will be used as metrics for adherence to the dietary recommendations of the WL intervention.

Participant Rights and Safety

Power Calculations

Data Management

Statistical Analysis Plan

Cognition (Primary Outcome)

Cerebral Hemodynamics (Secondary Outcomes)

Time-Course Effects and Adherence (Exploratory Outcomes)

Predictors of Cognitive and Cerebral Hemodynamic Responses (Exploratory Outcomes)

Individual Cognitive Functions (Exploratory Outcomes)

Discussion

Funding Sources

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

References

- Harada, C.N.; Natelson Love, M.C.N.; Triebel, K.L. Normal Cognitive Aging. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 2013, 29, 737–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dye, L.; Boyle, N.B.; Champ, C.; Lawton, C. The relationship between obesity and cognitive health and decline. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2017, 76, 443–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gauthier S, Reisberg B, Zaudig M; et al. Mild cognitive impairment. Lancet 2006, 367(9518), 1262-70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, K.; Hughes, C.F.; Ward, M.; Hoey, L.; McNulty, H. Diet, nutrition and the ageing brain: current evidence and new directions. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2018, 77, 152–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estimation of the global prevalence of dementia in 2019 and forecasted prevalence in 2050: an analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Public Health 2022, 7(2), e105-e25.

- Livingston, G.; Huntley, J.; Sommerlad, A.; Ames, D.; Ballard, C.; Banerjee, S.; Brayne, C.; Burns, A.; Cohen-Mansfield, J.; Cooper, C.; et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. Lancet 2020, 396, 413–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bischof GN, Park DC. Obesity and Aging: Consequences for Cognition, Brain Structure, and Brain Function. Psychosom Med. 2015, 77(6), 697–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alosco, M.L.; Spitznagel, M.B.; Raz, N.; Cohen, R.; Sweet, L.H.; Colbert, L.H.; Josephson, R.; van Dulmen, M.; Hughes, J.; Rosneck, J.; et al. Obesity Interacts with Cerebral Hypoperfusion to Exacerbate Cognitive Impairment in Older Adults with Heart Failure. Cerebrovasc. Dis. Extra 2012, 2, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willeumier, K.C.; Taylor, D.V.; Amen, D.G. Elevated BMI Is Associated With Decreased Blood Flow in the Prefrontal Cortex Using SPECT Imaging in Healthy Adults. Obesity 2011, 19, 1095–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selim, M.; Jones, R.; Novak, P.; Zhao, P.; Novak, V. The effects of body mass index on cerebral blood flow velocity. Clin. Auton. Res. 2008, 18, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anstey, K.J.; Cherbuin, N.; Budge, M.; Young, J. Body mass index in midlife and late-life as a risk factor for dementia: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Obes. Rev. 2011, 12, e426–e437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zhao, M.; Han, Z.; Li, D.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Kong, X.; Sun, N.; Zhang, Q.; Lei, P. Association of body mass index with amnestic and non-amnestic mild cognitive impairment risk in elderly. BMC Psychiatry 2017, 17, 334–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, E.; Hay, P.; Campbell, L.; Trollor, J.N. A review of the association between obesity and cognitive function across the lifespan: implications for novel approaches to prevention and treatment. Obes. Rev. 2011, 12, 740–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parletta, N.; Milte, C.M.; Meyer, B.J. Nutritional modulation of cognitive function and mental health. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2013, 24, 725–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miquel S, Champ C, Day J; et al. Poor cognitive ageing: Vulnerabilities, mechanisms and the impact of nutritional interventions. Ageing Res Rev. 2018, 42, 40–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez, L.J.; Barbagallo, M. Nutritional prevention of cognitive decline and dementia. Acta Biomed. 2018, 89, 276–290. [Google Scholar]

- Key, M.N.; Szabo-Reed, A.N. Impact of Diet and Exercise Interventions on Cognition and Brain Health in Older Adults: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamasaki, T. Preventive Strategies for Cognitive Decline and Dementia: Benefits of Aerobic Physical Activity, Especially Open-Skill Exercise. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesse-Guyot E, Peneau S, Ferry M; et al. Thirteen-year prospective study between fish consumption, long-chain n-3 fatty acids intakes and cognitive function. The Journal of Nutrition, Health & Aging 2011, 15(2), 115-20. [Google Scholar]

- Daiello, L.A.; Gongvatana, A.; Dunsiger, S.; Cohen, R.A.; Ott, B.R.; Initiative, A.D.N. Association of fish oil supplement use with preservation of brain volume and cognitive function. Alzheimer's Dement. 2014, 11, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrott, M.D.; Shatenstein, B.; Ferland, G.; Payette, H.; Morais, J.A.; Belleville, S.; Kergoat, M.-J.; Gaudreau, P.; Greenwood, C.E. Relationship between Diet Quality and Cognition Depends on Socioeconomic Position in Healthy Older Adults. J. Nutr. 2013, 143, 1767–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangney, C.C.; Kwasny, M.J.; Li, H.; Wilson, R.S.; Evans, A.D.; Morris, M.C. Adherence to a Mediterranean-type dietary pattern and cognitive decline in a community population. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 93, 601–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masana, M.F.; Koyanagi, A.; Haro, J.M.; Tyrovolas, S. n-3 Fatty acids, Mediterranean diet and cognitive function in normal aging: A systematic review. Exp. Gerontol. 2017, 91, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, M.C.; Tangney, C.C.; Wang, Y.; Sacks, F.M.; Bennett, D.A.; Aggarwal, N.T. MIND diet associated with reduced incidence of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's Dement. 2015, 11, 1007–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van den Brink AC, Brouwer-Brolsma EM, Berendsen AAM. The Mediterranean, Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH), and Mediterranean-DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay (MIND) Diets Are Associated with Less Cognitive Decline and a Lower Risk of Alzheimer’s Disease-A Review. Adv Nutr. 2019, 10(6), 1040-65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nurk, E.; Refsum, H.; Bjelland, I.; Drevon, C.A.; Tell, G.S.; Ueland, P.M.; Vollset, S.E.; Engedal, K.; Nygaard, H.A.; Smith, D.A. Plasma free choline, betaine and cognitive performance: the Hordaland Health Study. Br. J. Nutr. 2012, 109, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- La Fata, G.; Weber, P.; Mohajeri, M.H. Effects of Vitamin E on Cognitive Performance during Ageing and in Alzheimer’s Disease. Nutrients 2014, 6, 5453–5472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.-W.; Hou, W.-S.; Li, M.; Tang, Z.-Y. Omega-3 fatty acids and risk of cognitive decline in the elderly: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2015, 28, 165–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, N.; Vandal, M.; Calon, F. The benefit of docosahexaenoic acid for the adult brain in aging and dementia. Prostaglandins, Leukot. Essent. Fat. Acids 2014, 92, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, A.; Diógenes, M.J.; de Mendonça, A.; Lunet, N.; Barros, H. Chocolate Consumption is Associated with a Lower Risk of Cognitive Decline. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 2016, 53, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Alonso M. Cocoa flavanols and cognition: regaining chocolate in old age? : Oxford University Press; 2015.

- Ellinger, S.; Stehle, P. Impact of Cocoa Consumption on Inflammation Processes—A Critical Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Nutrients 2016, 8, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vauzour, D. Polyphenols and brain health. OCL 2017, 24, A202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolov, A.N.; Pavlova, M.A.; Klosterhalfen, S.; Enck, P. Chocolate and the brain: Neurobiological impact of cocoa flavanols on cognition and behavior. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2013, 37, 2445–2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calder, P.C. Omega-3 Fatty Acids and Inflammatory Processes. Nutrients 2010, 2, 355–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyall, S.C. Long-chain omega-3 fatty acids and the brain: a review of the independent and shared effects of EPA, DPA and DHA. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2015, 7, 52–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael-Titus AT, Priestley JV. Omega-3 fatty acids and traumatic neurological injury: from neuroprotection to neuroplasticity? Trends Neurosci. 2014, 37(1), 30-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsukada, H.; Kakiuchi, T.; Fukumoto, D.; Nishiyama, S.; Koga, K. Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) improves the age-related impairment of the coupling mechanism between neuronal activation and functional cerebral blood flow response: a PET study in conscious monkeys. Brain Res. 2000, 862, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joris, P.J.; Mensink, R.P.; Adam, T.C.; Liu, T.T. Cerebral Blood Flow Measurements in Adults: A Review on the Effects of Dietary Factors and Exercise. Nutrients 2018, 10, 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwarz, C.; Wirth, M.; Gerischer, L.; Grittner, U.; Witte, A.V.; Köbe, T.; Flöel, A. EFFECTS OF OMEGA-3 FATTY ACIDS ON RESTING CEREBRAL PERFUSION IN PATIENTS WITH MILD COGNITIVE IMPAIRMENT: A RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED TRIAL. J. Prev. Alzheimer's Dis. 2017, 5, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schliebs, R.; Arendt, T. The cholinergic system in aging and neuronal degeneration. Behav. Brain Res. 2011, 221, 555–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crichton, G.E.; Elias, M.F.; Alkerwi, A. Chocolate intake is associated with better cognitive function: The Maine-Syracuse Longitudinal Study. Appetite 2016, 100, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teo, L.; Crawford, C.; Snow, J.; Deuster, P.A.; Bingham, J.J.; Gallon, M.D.; O’connell, M.L.; Chittum, H.K.; Arzola, S.M.; Berry, K. Phytochemicals to optimize cognitive function for military mission-readiness: a systematic review and recommendations for the field. Nutr. Rev. 2017, 75, 49–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Dyck CH, Swanson CJ, Aisen P; et al. Lecanemab in Early Alzheimer’s Disease. N Engl J Med. 2023, 388(1), 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pervin, M.; Unno, K.; Takagaki, A.; Isemura, M.; Nakamura, Y. Function of Green Tea Catechins in the Brain: Epigallocatechin Gallate and its Metabolites. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afzal, O.; Dalhat, M.H.; Altamimi, A.S.A.; Rasool, R.; Alzarea, S.I.; Almalki, W.H.; Murtaza, B.N.; Iftikhar, S.; Nadeem, S.; Nadeem, M.S.; et al. Green Tea Catechins Attenuate Neurodegenerative Diseases and Cognitive Deficits. Molecules 2022, 27, 7604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unno, K.; Nakamura, Y. Green Tea Suppresses Brain Aging. Molecules 2021, 26, 4897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.A.; Mandal, A.K.A.; Khan, Z.A. Potential neuroprotective properties of epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG). Nutr. J. 2015, 15, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nehlig, A. The neuroprotective effects of cocoa flavanol and its influence on cognitive performance. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2013, 75, 716–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Socci, V.; Tempesta, D.; Desideri, G.; De Gennaro, L.; Ferrara, M. Enhancing Human Cognition with Cocoa Flavonoids. Front. Nutr. 2017, 4, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gratton G, Weaver SR, Burley CV; et al. Dietary flavanols improve cerebral cortical oxygenation and cognition in healthy adults. Sci Rep. 2020, 10(1), 19409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bapir, M.; Campagnolo, P.; Rodriguez-Mateos, A.; Skene, S.S.; Heiss, C. Assessing Variability in Vascular Response to Cocoa With Personal Devices: A Series of Double-Blind Randomized Crossover n-of-1 Trials. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 886597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mastroiacovo, D.; Kwik-Uribe, C.; Grassi, D.; Necozione, S.; Raffaele, A.; Pistacchio, L.; Righetti, R.; Bocale, R.; Lechiara, M.C.; Marini, C.; et al. Cocoa flavanol consumption improves cognitive function, blood pressure control, and metabolic profile in elderly subjects: the Cocoa, Cognition, and Aging (CoCoA) Study—a randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 101, 538–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francis, S.T.; Head, K.; Morris, P.G.; Macdonald, I.A. The Effect of Flavanol-rich Cocoa on the fMRI Response to a Cognitive Task in Healthy Young People. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2006, 47, S215–S220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farzaneh; A Sorond, F. ; A Lipsitz, L.; Hollenberg, N.K.; Fisher, N.D. Cerebral blood flow response to flavanol-rich cocoa in healthy elderly humans. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2008, 4, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholey, A.; Owen, L. Effects of chocolate on cognitive function and mood: a systematic review. Nutr. Rev. 2013, 71, 665–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelli V, Grassi D, Bocale R; et al. Diet and Brain Health: Which Role for Polyphenols? Curr Pharm Des. 2018, 24(2), 227-38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, S.B.; E Silver, R.; Das, S.K.; A Fielding, R.; Gilhooly, C.H.; Jacques, P.F.; Kelly, J.M.; Mason, J.B.; McKeown, N.M.; A Reardon, M.; et al. Healthy Aging—Nutrition Matters: Start Early and Screen Often. Adv. Nutr. Int. Rev. J. 2021, 12, 1438–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A McCrory, M.; Fuss, P.J.; E McCallum, J.; Yao, M.; Vinken, A.G.; Hays, N.P.; Roberts, S.B. Dietary variety within food groups: association with energy intake and body fatness in men and women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1999, 69, 440–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desideri G, Kwik-Uribe C, Grassi D; et al. Benefits in cognitive function, blood pressure, and insulin resistance through cocoa flavanol consumption in elderly subjects with mild cognitive impairment: the Cocoa, Cognition, and Aging (CoCoA) study. Hypertension 2012, 60(3), 794–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamport, D.J.; Pal, D.; Moutsiana, C.; Field, D.T.; Williams, C.M.; Spencer, J.P.E.; Butler, L.T. The effect of flavanol-rich cocoa on cerebral perfusion in healthy older adults during conscious resting state: a placebo controlled, crossover, acute trial. Psychopharmacol. 2015, 232, 3227–3234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karl, J.P.; Meydani, M.; Barnett, J.B.; Vanegas, S.M.; Goldin, B.; Kane, A.; Rasmussen, H.; Saltzman, E.; Vangay, P.; Knights, D.; et al. Substituting whole grains for refined grains in a 6-wk randomized trial favorably affects energy-balance metrics in healthy men and postmenopausal women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 105, 589–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilhooly, C.H.; Das, S.K.; Golden, J.K.; McCrory, M.A.; Rochon, J.; DeLany, J.P.; Freed, A.M.; Fuss, P.J.; Dallal, G.E.; Saltzman, E.; et al. Use of cereal fiber to facilitate adherence to a human caloric restriction program. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2008, 20, 513–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howarth, N.C.; Saltzman, E.; Roberts, S.B. Dietary Fiber and Weight Regulation. Nutr. Rev. 2001, 59, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe, P.R.C.; Evans, H.M.; Kuszewski, J.C.; Wong, R.H.X. Effects of Long Chain Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids on Brain Function in Mildly Hypertensive Older Adults. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kramer, M.K.; Kriska, A.M.; Venditti, E.M.; Miller, R.G.; Brooks, M.M.; Burke, L.E.; Siminerio, L.M.; Solano, F.X.; Orchard, T.J. Translating the Diabetes Prevention Program: A Comprehensive Model for Prevention Training and Program Delivery. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2009, 37, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taetzsch, A.; Gilhooly, C.H.; Bukhari, A.; Das, S.K.; Martin, E.; Hatch, A.M.; E Silver, R.; Montain, S.J.; Roberts, S.B. Development of a Videoconference-Adapted Version of the Community Diabetes Prevention Program, and Comparison of Weight Loss With In-Person Program Delivery. Mil. Med. 2019, 184, 647–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Control CfD, Prevention. National diabetes fact sheet: national estimates and general information on diabetes and prediabetes in the United States, 2011. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2011;201(1):1-12.

- Das, S.K.; Bukhari, A.S.; Taetzsch, A.G.; Ernst, A.K.; Rogers, G.T.; Gilhooly, C.H.; Hatch-McChesney, A.; Blanchard, C.M.; A Livingston, K.; E Silver, R.; et al. Randomized trial of a novel lifestyle intervention compared with the Diabetes Prevention Program for weight loss in adult dependents of military service members. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 114, 1546–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaton, R.K.; Akshoomoff, N.; Tulsky, D.; Mungas, D.; Weintraub, S.; Dikmen, S.; Beaumont, J.; Casaletto, K.B.; Conway, K.; Slotkin, J.; et al. Reliability and Validity of Composite Scores from the NIH Toolbox Cognition Battery in Adults. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2014, 20, 588–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benton AL, Abigail B, Sivan AB, Hamsher Kd, Varney NR, Spreen O. Contributions to neuropsychological assessment: A clinical manual: Oxford University Press, USA; 1994.

- Smith, A. Symbol digit modalities test: Western psychological services Los Angeles; 1973.

- Stroop, JR. Studies of interference in serial verbal reactions. Journal of Experimental Psychology 1935, 18(6), 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reitan RM, Wolfson D. The Halstead-Reitan neuropsychological test battery: Theory and clinical interpretation: Reitan Neuropsychology; 1985.

- Reitan, R.M. VALIDITY OF THE TRAIL MAKING TEST AS AN INDICATOR OF ORGANIC BRAIN DAMAGE. Percept. Mot. Ski. 1958, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, D.M.; Harrison, D.W. Alternate forms of the AVLT: a procedure and test of form equivalency. . 1990, 5, 405–10. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung C, Culver JP, Takahashi K. In vivo cerebrovascular measurement combining diffuse near-infrared absorption and correlation spectroscopies. Phys Med Biol. 2001, 46(8), 2053-65. [Google Scholar]

- Sunwoo, J.; Zavriyev, A.I.; Kaya, K.; Martin, A.; Munster, C.; Steele, T.; Cuddyer, D.; Sheldon, Y.; Orihuela-Espina, F.; Herzberg, E.M.; et al. Diffuse correlation spectroscopy blood flow monitoring for intraventricular hemorrhage vulnerability in extremely low gestational age newborns. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mesquita, R.C.; Durduran, T.; Yu, G.; Buckley, E.M.; Kim, M.N.; Zhou, C.; Choe, R.; Sunar, U.; Yodh, A.G.; C., M.R.; et al. Direct measurement of tissue blood flow and metabolism with diffuse optics. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A: Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2011, 369, 4390–4406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durduran, T.; Yodh, A.G. Diffuse correlation spectroscopy for non-invasive, micro-vascular cerebral blood flow measurement. NeuroImage 2013, 85, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, E.M.; Parthasarathy, A.B.; Grant, P.E.; Yodh, A.G.; Franceschini, M.A. Diffuse correlation spectroscopy for measurement of cerebral blood flow: future prospects. Neurophotonics 2014, 1, 011009–011009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green MS, Sehgal S, Tariq R. Near-Infrared Spectroscopy: The New Must Have Tool in the Intensive Care Unit? Semin Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2016, 20(3), 213-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hogue, C.W.; Levine, A.; Hudson, A.; Lewis, C. Clinical Applications of Near-infrared Spectroscopy Monitoring in Cardiovascular Surgery. Anesthesiology 2021, 134, 784–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, K.-C.; Tamborini, D.; Renna, M.; Peruch, A.; Huang, Y.; Martin, A.; Kaya, K.; Starkweather, Z.; Zavriyev, A.I.; Carp, S.A.; et al. Open-source FlexNIRS: A low-cost, wireless and wearable cerebral health tracker. NeuroImage 2022, 256, 119216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, S.K.; Gilhooly, C.H.; Golden, J.K.; Pittas, A.G.; Fuss, P.J.; A Cheatham, R.; Tyler, S.; Tsay, M.; A McCrory, M.; Lichtenstein, A.H.; et al. Long-term effects of 2 energy-restricted diets differing in glycemic load on dietary adherence, body composition, and metabolism in CALERIE: a 1-y randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 85, 1023–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinardi, T.C.; Batra, P.; Roberts, S.B.; E Urban, L.; Robinson, L.M.; Pittas, A.G.; Lichtenstein, A.H.; Deckersbach, T.; Saltzman, E.; Das, S.K. Lifestyle intervention reduces body weight and improves cardiometabolic risk factors in worksites. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 97, 667–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, J.C.; Matthews, D.R.; Hermans, M.P. Correct Homeostasis Model Assessment (HOMA) Evaluation Uses the Computer Program. Diabetes Care 1998, 21, 2191–2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangen, K.J.; Beiser, A.; Delano-Wood, L.; Nation, D.A.; Lamar, M.; Libon, D.J.; Bondi, M.W.; Seshadri, S.; Wolf, P.A.; Au, R. APOE Genotype Modifies the Relationship between Midlife Vascular Risk Factors and Later Cognitive Decline. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2013, 22, 1361–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Basak, J.M.; Holtzman, D.M. The Role of Apolipoprotein E in Alzheimer's Disease. Neuron 2009, 63, 287–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ware, J.E., Jr.; Sherbourne, C.D. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med. Care 1992, 30, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ware JE, Snow KK, Kosinski M, Gandek B. SF-36 health survey: manual and interpretation guide. Boston: The Health Institute, New England Medical Center; 1993.

- Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, 3rd. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989, 28(2), 193–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Beck Depression Inventory-II. San Antonio. 1996;78(2):490-8.

- Karlsson, J.; Persson, L.-O.; Sjöström, L.; Sullivan, M. Psychometric properties and factor structure of the Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire (TFEQ) in obese men and women. Results from the Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) study. Int. J. Obes. 2000, 24, 1715–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer, R.I.; Kurosaki, T.T.; Harrah, C.H.; Chance, J.M.; Filos, S. Measurement of Functional Activities in Older Adults in the Community. J. Gerontol. 1982, 37, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keating, X.D.; Zhou, K.; Liu, X.; Hodges, M.; Liu, J.; Guan, J.; Phelps, A.; Castro-Piñero, J. Reliability and Concurrent Validity of Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ): A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2019, 16, 4128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lytle, L.A.; Nicastro, H.L.; Roberts, S.B.; Evans, M.; Jakicic, J.M.; Laposky, A.D.; Loria, C.M. Accumulating Data to Optimally Predict Obesity Treatment (ADOPT) Core Measures: Behavioral Domain. Obesity 2018, 26, S16–S24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bathalon, G.P.; Tucker, K.L.; Hays, N.P.; Vinken, A.G.; Greenberg, A.S.; A McCrory, M.; Roberts, S.B. Psychological measures of eating behavior and the accuracy of 3 common dietary assessment methods in healthy postmenopausal women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2000, 71, 739–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.T.; Roberts, S.B.; Howarth, N.C.; McCrory, M.A. Effect of Screening Out Implausible Energy Intake Reports on Relationships between Diet and BMI. Obes. Res. 2005, 13, 1205–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwingshackl, L.; Bogensberger, B.; Hoffmann, G. Diet Quality as Assessed by the Healthy Eating Index, Alternate Healthy Eating Index, Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension Score, and Health Outcomes: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2018, 118, 74–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Napoli, N.; Shah, K.; Waters, D.L.; Sinacore, D.R.; Qualls, C.; Villareal, D.T. Effect of weight loss, exercise, or both on cognition and quality of life in obese older adults. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 100, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stillman, C.M.; Jakicic, J.; Rogers, R.; Alfini, A.J.; Smith, J.C.; Watt, J.; Kang, C.; Erickson, K.I. Changes in cerebral perfusion following a 12-month exercise and diet intervention. Psychophysiology 2020, 58, e13589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorond, F.A.; Hurwitz, S.; Salat, D.H.; Greve, D.N.; Fisher, N.D. Neurovascular coupling, cerebral white matter integrity, and response to cocoa in older people. Neurology 2013, 81, 904–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Hopewell, S.; Schulz, K.F.; Montori, V.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Devereaux, P.; Elbourne, D.; Egger, M.; Altman, D.G. CONSORT 2010 Explanation and Elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. J. Clin. Epidemiology 2010, 63, e1–e37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrman, H.; Kieling, C.; McGorry, P.; Horton, R.; Sargent, J.; Patel, V. Reducing the global burden of depression: a Lancet–World Psychiatric Association Commission. Lancet 2018, 393, e42–e43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prince, M.J.; Wu, F.; Guo, Y.; Robledo, L.M.G.; O'Donnell, M.; Sullivan, R.; Yusuf, S. The burden of disease in older people and implications for health policy and practice. Lancet 2014, 385, 549–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, W.; Sanderson, W.; Scherbov, S. The coming acceleration of global population ageing. Nature 2008, 451, 716–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, B.K.; Berger, S.L.; Brunet, A.; Campisi, J.; Cuervo, A.M.; Epel, E.S.; Franceschi, C.; Lithgow, G.J.; Morimoto, R.I.; Pessin, J.E.; et al. Geroscience: Linking Aging to Chronic Disease. Cell 2014, 159, 709–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milte, C.M.; McNaughton, S. Dietary patterns and successful ageing: a systematic review. Eur. J. Nutr. 2015, 55, 423–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crimmins, E.M. Lifespan and Healthspan: Past, Present, and Promise. Gerontol. 2015, 55, 901–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, S.B.; Franceschini, M.A.; Krauss, A.; Lin, P.-Y.; de Sa, A.B.; Có, R.; Taylor, S.; Brown, C.; Chen, O.; Johnson, E.J.; et al. A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial of a New Supplementary Food Designed to Enhance Cognitive Performance during Prevention and Treatment of Malnutrition in Childhood. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2017, 1, e000885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts SB, Franceschini MA, Taylor SF; et al. Effects of food supplementation on cognitive function, and cerebral blood flow and nutritional status, in young children at risk of undernutrition: a family-randomized controlled trial. BMJ 2020, 370, m2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roust, L.R.; DiBaise, J.K. Nutrient deficiencies prior to bariatric surgery. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2017, 20, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caulfield LE, Richard SA, Rivera JA, Musgrove P, Black RE. Stunting, Wasting, and Micronutrient Deficiency Disorders. In: Jamison DT, Breman JG, Measham AR, Alleyne G, Claeson M, Evans DB, et al., editors. Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries. 2nd ed. Washington (DC) New York: The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank; 2006.

- Mattson, M.P.; Magnus, T. Ageing and neuronal vulnerability. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2006, 7, 278–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gemma, C.; Vila, J.; Bachstetter, A.; Bickford, P.C. Oxidative stress and the aging brain: From theory to prevention. In Frontiers in Neuroscience. Brain Aging: Models, Methods, and Mechanisms; Riddle, D.R., Ed.; CRC Press; American Publishing Group: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2007; pp. 353–374. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, K.N.; Girard, S.; Holmes, W.M.; Parkes, L.M.; Williams, S.R.; Parry-Jones, A.R.; Allan, S.M. Systemic Inflammation Impairs Tissue Reperfusion Through Endothelin-Dependent Mechanisms in Cerebral Ischemia. Stroke 2014, 45, 3412–3419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Lin, H.; Lu, C.; Chen, P.; Huang, C.; Chou, K.; Su, M.; Friedman, M.; Chen, Y.; Lin, W. Systemic inflammation and alterations to cerebral blood flow in obstructive sleep apnea. J. Sleep Res. 2017, 26, 789–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekdahl, C.T.; Claasen, J.-H.; Bonde, S.; Kokaia, Z.; Lindvall, O. Inflammation is detrimental for neurogenesis in adult brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 13632–13637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- John, C.C.; Black, M.M.; Nelson, C.A. Neurodevelopment: The Impact of Nutrition and Inflammation During Early to Middle Childhood in Low-Resource Settings. PEDIATRICS 2017, 139, S59–S71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fryar C, Carrol M, Afful J. Prevalence of overweight, obesity, and severe obesity among adults aged 20 and over: United States, 1960–1962 through 2017–2018. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020;NCHS Health E-Stats.

- Attwell, D.; Buchan, A.M.; Charpak, S.; Lauritzen, M.J.; MacVicar, B.A.; Newman, E.A. Glial and neuronal control of brain blood flow. Nature 2010, 468, 232–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabayan B, van der Grond J, Westendorp RG; et al. Total cerebral blood flow and mortality in old age: a 12-year follow-up study. Neurology 2013, 81(22), 1922-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vestergaard, M.B.; Jensen, M.L.; Arngrim, N.; Lindberg, U.; Larsson, H.B. Higher physiological vulnerability to hypoxic exposure with advancing age in the human brain. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2018, 40, 341–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beason-Held, L.L.; Goh, J.O.; An, Y.; Kraut, M.A.; O'Brien, R.J.; Ferrucci, L.; Resnick, S.M. Changes in Brain Function Occur Years before the Onset of Cognitive Impairment. J. Neurosci. 2013, 33, 18008–18014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorrance, A.M.; Matin, N.; Pires, P.W. The effects of obesity on the cerebral vasculature. Curr. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2014, 12, 462–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, S.K.; Kumar, R.; Macey, P.M.; Richardson, H.L.; Wang, D.J.; Woo, M.A.; Harper, R.M. Regional cerebral blood flow alterations in obstructive sleep apnea. Neurosci. Lett. 2013, 555, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, M.L.F.; Vestergaard, M.B.; Tønnesen, P.; Larsson, H.B.W.; Jennum, P.J. Cerebral blood flow, oxygen metabolism, and lactate during hypoxia in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep 2018, 41, zsy001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Zhao, B.; Yan, L.; Jann, K.; Wang, G.; Wang, J.; Wang, B.; Pfeuffer, J.; Qian, T.; Wang, D.J.J. Cerebral Hemodynamic and White Matter Changes of Type 2 Diabetes Revealed by Multi-TI Arterial Spin Labeling and Double Inversion Recovery Sequence. Front. Neurol. 2017, 8, 717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, RA. Hypertension and cerebral blood flow: implications for the development of vascular cognitive impairment in the elderly. Stroke 2007, 38(6), 1715-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stopa, E.G.; Butala, P.; Salloway, S.; Johanson, C.E.; Gonzalez, L.; Tavares, R.; Hovanesian, V.; Hulette, C.M.; Vitek, M.P.; Cohen, R.A.; et al. Cerebral Cortical Arteriolar Angiopathy, Vascular Beta-Amyloid, Smooth Muscle Actin, Braak Stage, and APOE Genotype. Stroke 2008, 39, 814–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salloway, S.; Gur, T.; Berzin, T.; Zipser, B.; Correia, S.; Hovanesian, V.; Fallon, J.; Kuo-Leblanc, V.; Glass, D.; Hulette, C.; et al. Effect of APOE genotype on microvascular basement membrane in Alzheimer's disease. J. Neurol. Sci. 2002, 203-204, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsop, D.C.; Dai, W.; Grossman, M.; Detre, J.A. Arterial Spin Labeling Blood Flow MRI: Its Role in the Early Characterization of Alzheimer's Disease. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 2010, 20, 871–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bangen KJ, Clark AL, Edmonds EC; et al. Cerebral Blood Flow and Amyloid-beta Interact to Affect Memory Performance in Cognitively Normal Older Adults. Front Aging Neurosci. 2017, 9, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bangen, K.J.; Werhane, M.L.; Weigand, A.J.; Edmonds, E.C.; Delano-Wood, L.; Thomas, K.R.; Nation, D.A.; Evangelista, N.D.; Clark, A.L.; Liu, T.T.; et al. Reduced Regional Cerebral Blood Flow Relates to Poorer Cognition in Older Adults With Type 2 Diabetes. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2018, 10, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolui, S.; Tisdall, D.; Vidorreta, M.; Jacobs, D.R.; Nasrallah, I.M.; Bryan, R.N.; Wolk, D.A.; Detre, J.A. Characterizing a perfusion-based periventricular small vessel region of interest. NeuroImage: Clin. 2019, 23, 101897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glodzik, L.; Rusinek, H.; Brys, M.; Tsui, W.H.; Switalski, R.; Mosconi, L.; Mistur, R.; Pirraglia, E.; de Santi, S.; Li, Y.; et al. Framingham Cardiovascular Risk Profile Correlates with Impaired Hippocampal and Cortical Vasoreactivity to Hypercapnia. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2010, 31, 671–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry, V. The influence of systemic inflammation on inflammation in the brain: implications for chronic neurodegenerative disease. Brain, Behav. Immun. 2004, 18, 407–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elwood, E.; Lim, Z.; Naveed, H.; Galea, I. The effect of systemic inflammation on human brain barrier function. Brain, Behav. Immun. 2016, 62, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).