Introduction

The most significant threat being faced by humanity is of road traffic accidents (RTAs), that can cause injuries, disabilities and loss of lives among people of all ages. The number of yearly fatalities from road traffic accidents has climbed to 1.35 million, which equates to nearly 3,700 people dying on the world's roads every day. RTAs are rated as the eighth most common cause of deaths among all causes. (WHO, 2018). The increasing rate of road traffic fatalities can be associated with a variety of factors, including increased urbanization, insufficient safety standards and enforcement, distracted or fatigued driving, impaired driving due to drugs or alcohol, speeding, and failure to wear a seat belt or wear a helmet (WHO, 2018). Researchers, around the globe believe that about 70% of crashes occur due to human factors (G.D. & Sayer, 1983). The human factors responsible for causation of traffic accidents as reported by Bucsuházy et al. (2020) are lack of concentration; tiredness and brief intervals of inadvertent sleep; misjudging the situation; driving too fast without adapting to the conditions; willfully violating traffic laws, lack of experience; weakened mental and physical capacities owing to age; the impact of alcohol and drugs; risky overtaking maneuvers ; reacting out of panic; health concerns; impaired visibility; being affected by luminous lights; and willful self-harm. In road safety studies, driver behavior (what a driver decides to do) is of greater concern than other human factors. Among driving behaviors, dangerous driving is an empirical and practical concern that includes behaviors such as aggressive driving, driving while under the influence of negative emotions, and getting involved in risky actions while operating a vehicle (Qu, Ge, Jiang, Du, & Zhang, 2014). It is commonly acknowledged that this phenomenon is one of the leading causes of traffic accidents on a global scale (Dahlen & White, 2006; Dula & Ballard, 2003; Qu et al., 2014). According to Pakistan Beaurau of Statistics (PBS, 2020), 94,358 accidents occurred from 2011 to 2020. In these accidents, a total of 164,742 people either got injured or lost their precious lives (deaths: 49,801; injuries: 114,941). In Pakistan, careless driving (55%) and driver tiredness (11%), are the leading causes of road accidents (A. Klair & Arfan, 2017). Over speeding, dangerous driving, reckless overtakes, a lack of situational awareness, and poor driving habits are the primary causes of careless driving. When compared to Western countries, Pakistan has a higher rate of unforeseen incidents while driving. According to a recent study in Pakistan, lack of proper training before driving is major cause of accidents. Moreover, in Pakistan 45% drivers do not possess driving licenses, 75 % drivers have learnt driving from friends and family members and more than 30% are involved directly or indirectly in road traffic accidents over a period of last 3 years (M. Hussain & Shi, 2020). Therefore, it can be argued that compared to drivers with license and proper training the risk of deaths from injuries is high in drivers without license and proper training. Drivers without license and training are more vulnerable to commit dangerous driving behaviors. Due to Pakistan's peculiar social and traffic situations, there is an urgent need for precise approaches to assess dangerous driving behaviors.

Dangerous driving behaviors comprises of aggression with intent to harm (behaviors and cognitive or emotional states that makes driving situation more dangerous), negative emotions (frustration, anger and rumination), as well as risky driving behaviors (lacking actual intent to harm) (Dula & Ballard, 2003; Qu et al., 2014; Willemsen, Dula, Declercq, & Verhaeghe, 2008). The Dula Dangerous Driver Index (DDDI) is one of the various instruments that measures the driver’s likelihood to dangerous driving, negative emotions while driving and risky driving whereas other instruments like Driving Anger Scale (DAS), the Driving Anger Expression Inventory (DAX), the Driver’s Angry Thought Questionnaire (DATQ) and the Propensity for Angry Driving Scale (PADS) measure anger only. Additionally, the transcribed variants of DDDI exhibit strong internal consistency. i.e., the US (Dula & Ballard, 2003), the French (Richer & Bergeron, 2012) and Romanian (Iliescu & Sarbescu, 2013) versions support the three-factor structure while the Flemish (Willemsen et al., 2008) and the Chinese (Qu et al., 2014), supports a four-factor structure. As far as our understanding goes, the DDDI has not undergone adequate validation in Pakistan thus far.

Aggressive driving contributes considerably to motor vehicle accidents, and is a main factor in dangerous driving instances (Dula & Ballard, 2003). A plethora of scientific studies have been conducted in order to conceptualize and investigate this phenomenon. Aggressive driving is distinguished from risky driving by the driver's intentional activities to physically or psychologically harm others. An aggressive driver expresses annoyance in a variety of ways, such as verbal (e.g., yelling, cursing), physical (e.g., confrontations, fights), or by using the vehicle they are driving to intimidate others (e.g., flashing lights, honking, tailgating, cutting off) (Deffenbacher, Lynch, Oetting, & Swaim, 2002). Driving infractions such as accidents and traffic citations are associated with aggressive driving. Anger, frustration, provocation, and aggravation, such as being upset or judging the acts of other drivers as inappropriate or dumb, are examples of negative cognitions and emotions when driving (Dula & Ballard, 2003; Iliescu & Sarbescu, 2013; Qu et al., 2014). The relationship between negative emotions and driving behaviors has been extensively researched, with one study finding a positive association between negative emotional driving and speeding (Richer & Bergeron, 2012). Studies have consistently found a link between negative emotions and increased instances of aggressive driving and traffic offences (Dahlen & White, 2006). Negative emotions can distract drivers, thinning their focus and increasing the likelihood of an accident (Willemsen et al., 2008). Risk-taking behaviors are classified into two types: socially unacceptable activities with potentially bad effects due to a lack of precautions, and socially acceptable but risky behaviors (Qu et al., 2014). Rushing red lights, cutting through traffic, and violating speed limits are all examples of risky driving behavior. Risky drivers do not want to do harm to others and may not be experiencing negative emotions or thoughts (Willemsen et al., 2008). Drivers with higher self-reported risky driving scores are more commonly engaged in traffic accidents than those with lower scores (Iversen & Rundmo, 2002).

Personal attributes also have an important influence on dangerous driving. Young drivers involved in vehicular crashes take more risks and drive more aggressively than senior drivers (Deffenbacher et al., 2002; Dula & Ballard, 2003; Qu et al., 2014). Different translations of the DDDI produce consistent findings as well. Young motorists exhibit more dangerous driving behaviors than elderly, showing an association between dangerous driving and age (Iliescu & Sarbescu, 2013; Richer & Bergeron, 2012). Driving expertise and gender also contributes to risky driving (Iliescu & Sarbescu, 2013). Inexperienced and young drivers are especially vulnerable to the effects of negative emotions (Iliescu & Sarbescu, 2013; Willemsen et al., 2008). Aside from individual differences, failure to use a seatbelt contributes to dangerous driving behaviors, i.e. risky driving (National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, 2021). In 2021, half of the passengers killed in car accidents were not wearing seatbelts in US and in 2017, seat belts saved about 14,955 lives, and an additional 2,549 lives may have been saved if they had been wearing seat belts (National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, 2021).

The main aim behind selecting Pakistan for this study is that driving in Pakistan is difficult because drivers don’t obey the traffic rules and regulations properly. Over speeding, violation of one-way zones, tail gating, over loading, over seating in public transport vehicles, emotional driving non adherence to seat belt laws etc., are a few examples of dangerous driving which eventually lead to road traffic accidents (A. Klair & Arfan, 2017). The seatbelt law has been documented in Pakistan through Motor Vehicle Ordinance (MVO) since 1965 (Governemnt of Pakistan, 1965) but the implementation level is very low. Drivers in Pakistan wear seat belts only while travelling on Motorways and National highways just to avoid fines as the enforcement level on these roads is high and fines are imposed if caught driving without seat belt (Khaliq et al., 2020). The enforcements levels to seatbelt usage are high in national capital, the provincial capitals and the highways which are in control of National Highway & Motorway (NH&MP) while on rural roads the enforcement level is very rare. The non-adherence to seat belt usage is very dangerous and can cost one’s life in case of accidents.

Driver training is another issue which promotes dangerous driving behaviors if not handled properly. In Pakistan it is very common to learn driving from friends, relatives or family members instead of proper driving institutes being operated by traffic enforcement agencies (Khaliq et al., 2020). Reason behind such a trend is the lack of availability of driving institutes at grass root levels within the country. If the instructor (anyone from friends, family members or relatives) is himself not fully aware of traffic rules and regulations cannot train properly others. As a result of which the newly trained drivers behave similarly as their trainers. When discussing the ineffectiveness of driver education in creating safer drivers, Williams (2005) also stated that "...safety messages communicated through education can be overshadowed by continuous parental, peer, individual, and various societal factors that mold driving behaviors and involvement in accidents." For instance; M. Hussain and Shi (2020) reported that lack of driving training and driving license influences the aberrant driving behaviors. In the United States, typical driver training programs (comprising 30 hours in the classroom plus 6 hours of on-the-road teaching) are anticipated to result in a 5% reduction in crash rates per newly licensed driver within the first 6 to 12 months of driving (Peck, 2011).

Because existing research in the context of Pakistani drivers have mostly investigated aberrant driving behavior i.e., (Batool & Carsten, 2016, 2017; M. Hussain & Shi, 2020; Muhammad Hussain, Shi, & Batool, 2020). As a result, there is a great need in Pakistan for adequately created or updated research methods for analyzing dangerous driving behaviors. The DDDI used in this study to assess drivers' self-reported likelihood of engaging in dangerous driving, is motivated by three distinct factors. First and foremost, the DDDI spans a broader scope by addressing negative cognitive processes and emotional sensations related with driving, as opposed to the DBQ (Reason, Manstead, Stradling, Baxter, & Campbell, 1990), which exclusively tackles aggressive driving. Second, while this instrument assesses aggressive and risky driving using independent subscales, there is a widespread propensity in many research to mix up these two distinct traits (Willemsen et al., 2008). Third, DDDI has never been validated in the context of Pakistani drivers. Analyzing dangerous driving behaviors displayed by Pakistani drivers is critical for understanding the core determinants and devising efficient methods to promote the adoption of safer driving practices. The main objectives of the present study were as follows:

- 1)

To identify the factor structure of DDDI among Pakistani drivers.

- 2)

To verify the internal consistency and convergent validity of DDDI.

- 3)

To examine the association among dangerous driving, sociodemographic variables, seat belt usage, driver training and road traffic accidents.

In Pakistan, a self-report questionnaire survey was conducted in order to meet the precise objectives. The survey was designed to assess the sociodemographic, driving-related characteristics, and involvement in dangerous driving behaviors of the participants. The individuals' propensities for dangerous driving were assessed using the 27-item Dula dangerous Driving Index (DDDI). Principal component analysis with varimax rotation was performed to determine the factor structure of dangerous driving behaviors among Pakistani drivers. The effect of demographic factors, the use of seatbelts, and driving training on dangerous driving habits and crashes (RTAs) among Pakistani drivers was also examined using a generalized linear model (GLM) and a binary logistic regression model.

Methods

Participants

Through online surveys and in-person interviews, 796 Pakistani participants in all completed the questionnaire voluntarily and confidentially. Upon necessary data screening and filtration 623 responses came out to be valid and were selected for further analysis. The participants age ranged from 18 to 65 years (M: 2.41, SD: 1.44), the sample consists of 81.2% male (N:506) and 18.8% female (N:117) participants. 72% of participants had a valid driving license. Most of the participants (50%) were the undergraduate, graduate students and employees of different universities while the remaining were drivers recruited from different bus stops, markets, residential areas. See

Table 1 for descriptive statistics of sample.

Measures

The DDDI: In this study, the Dula dangerous Driving Index (DDDI), a self-report instrument created by Dula and Ballard in 2003 to identify personal bias for unsafe driving, was employed. The original scale has 28 items and three components: risky driving (12 items), negative emotions while driving (9 items), and aggressive driving (7 items). Because alcohol intake is prohibited in Pakistan, one item linked to drunk driving was eliminated, and a 27-item DDDI was employed in this study. On a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 ("never") to 5 ("always"), respondents ranked the frequency of each item voluntarily.

The Urdu version of the DDDI unique to Pakistan was used in this study. The original English version was translated to accommodate the bulk of individuals (drivers) who, due to poor education, have difficulty grasping the English language. The translation of the original version of DDDI into Urdu was done by adopting the procedure explained as follows. Firstly, we requested four professors from the language department to interpret the DDDI into Urdu individually at the same time. Upon completion of translation, a consolidated single draft was formulated by through discussion on the individual translations. Secondly, five experienced drivers were hired to check and discuss the draft to make sure that items have no ambiguity. Finally, based upon the feedback and group discussion with five probable participants (drivers) that were hired to pretest the translated draft, the scale was modified and finalized.

Sociodemographic: The demographics section included questions related to age, gender, education, and driving experience etc. Participants were also required to respond to questions related to driving license (if they had a valid driver's license), seatbelt usage (if they utilized a seatbelt while driving?), driving training (from where they learnt to drive), their preferred time of travel (morning, evening, midnight etc.) and accidents in last three years (if they had ever been in a traffic accident in past three years).

Procedure

Data collection was accomplished in two steps, first by running an online survey and second through physical data collection using a self-report and anonymous questionnaire. Google forms were used to develop the online questionnaire and the links were shared through social media platforms. Whereas the physical data collection was accomplished by recruiting willing drivers from bus terminals, parking’s of shopping malls, restaurants, and other commercial places. All the participants were briefed that their information will not be shared publicly and will be utilized for research purposes. All the respondents were drivers representing different profession in Pakistan. Once the data collection was completed the data screening and sorting was performed to remove the unwanted data. Data analysis was performed using SPSS version 26.0. The descriptive statistics were determined as shown above in

Table 1, followed by principal component analysis to find the factor structure of DDDI. Once the factor structure was determined, the reliability (internal consistency) and convergent validity of the DDDI factors was determined using the reliability analysis i.e., Cronbach alpha coefficients and Pearson bivariate correlation analysis. Generalized linear models were used to find the predictors of dangerous driving behaviors among Pakistani drivers. A versatile statistical framework called the Generalized Linear Model (GLM) expands on the linear model to manage response variables that are not normally distributed, developed by Robert Wedderburn and statistician Sir John Nelder in 1972 (McCullagh, 1989). GLM provides a familiar technique to a wide range of response modeling problems for example, when the response variables are not normally distributed or “variance is a function of mean” for many continuous variables. GLM techniques are also applicable to categorical data. GLM has two components; The random component of the probability function that describes the variation in the values of the response variable, and the structural component of the probability function that links the mean of the response variable to the values of the predictors (Smyth, 2018). The DDDI factors were incorporated in the model as dependent variables (DVs) while the demographic factors, the seatbelt usage, driving training and driving license variables were used as independent variables (IV). The DVs and IVs coding used in the analysis is shown in

Table 2 respectively. Similarly, the effect on dangerous driving behavior dimensions, demographics and other study variables on occurrence of traffic accidents was also determined using binary logistic regression model as the dependent variable has two outcomes i.e., either involved in a traffic accident or not involved in a traffic accident (yes/No). The variables mentioned in table including the DVs (i.e., aggressive, risky and negative emotional driving) were used as independent variables to predict traffic accidents among Pakistani drivers.

Results

Factor Structure of DDDI

To obtain the factor structure of DDDI, Principal component analysis (PCA) with varimax rotation was performed using SPSS statistical software (version 25). Suitability of data before performing PCA was checked on two parameters; Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy and Bartlett's Test of Sphericity (BTS). The KMO ratio of sample came out to be 0.821 indicating that sample is adequate for analysis. Likewise, the BTS was also significant for the data (p<0.000) thus, after meeting the pre-requisites the data was factor analyzed with varimax rotation. The PCA analysis revealed three families of DDDI dimensions which represent a vivid picture of dangerous driving behaviors amongst drivers in Pakistan. Each dangerous driving dimension was named based on the dominating contributing factor to that dimension; Risky driving, Aggressive driving and Negative emotions while driving. The items extracted in PCA analysis are shown below in

Table 2 respectively.

The first extracted factor was named, “Risky driving” as it contains four items and accounts for 17.80% variance. This factor is dominated by item related to risky driving i.e. I will drive in the shoulder lane or median to get around traffic jam. The second factor was, “negative emotions while driving” containing five items and accounts for 16.75% variance. The negative emotions factor is dominated by items which reflects negative emotions while driving of Pakistani drivers, i.e. I get irritated when a car/truck in front of me slows down for no reason. Dominated by traits of aggressive driving, i.e., tail gating, making rude gestures, flashing lights etc., this factor was named, “Aggressive driving”. It contains three items (i.e., I flash my headlights when I am annoyed by another driver) and accounts for 17.01% of variance. See

Table 3 for detailed information.

Internal Consistency

To check the reliability of DDDI sub scales, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient were evaluated. The three subscales and overall DDDI score showed good internal consistency. The alpha (α) value of the overall DDDI score was 0.771. Whereas, all the subscale α values were within the acceptable ranges, i.e., risky driving (α value: 0.702), negative emotion while driving (α value: 0.698) and aggressive driving (α value: 0.716). See

Table 4 for detailed information.

Convergent Validity

Pearson’s correlation: Pearson’s (bivariate) correlation was employed to study the association among Dula Dangerous Driving Index (DDDI) dimensions, DDDI score, demographic variables (age, driving experience), accident involvement, driving license and seat belt usage. A positive and significant correlation exist among the three DDDI dimensions and DDDI score (p < 0.01). Age was negatively related with risky and aggressive driving DDDI subscales and DDDI score (p < 0.01), which shows that the novice drivers are more prone to involve in dangerous driving as compared to older drivers. Driving experience was also negatively related with aggressive driving (AD) (r = -0.093, p <0.01), risky driving (RD) (r = -0.153, p < 0.01) and DDDI score (r = -0.049, p < 0.01), which suggest that inexperience drivers were more prone to commit dangerous and risky driving as compared to experienced drivers. Furthermore, a significant correlation was evident between accidents and aggressive driving (r = 0.151, p < 0.01), accidents and risky driving (r = 0.142, p < 0.01), accidents and negative emotional driving (r = 0.119, p < 0.05) accidents and DDDI score (r = 0.102, p < 0.05), which describes a direct association among these variables. See

Table 5 for detailed information.

Factors Predicting Dangerous Driving Behaviors

To assess the effects of demographics variables, seatbelt usage and driving training on dangerous driving behaviors regression analysis was performed. Our aim was to assess, whether demographics, Seat belt usage and driving training predict the dangerous driving behaviors”. To achieve this aim generalized linear model (GLM) with gamma link was applied. GLM provide a familiar technique to a wide range of response modelling problems for example, when the response variables are not normally distributed or “variance is a function of mean” for many continuous variables. GLM techniques are also applicable to categorical data. GLM has two components; The random component of the probability function that describes the variation in the values of the response variable, and the structural component of the probability function that links the mean of the response variable to the values of the predictors. (Dunn, 2023).

Three GLM models were utilized in regression analysis to investigate the association between seat belt usage, driving training and DDDI dimensions along with demographics. The first GLM model examines, the association between all the predictor variables and risky driving. The results showed that the drivers who got training from traffic police operated driving schools (β: -0.398, odds ratio [OR]: 0.672, p < 0.01), from a private driving school (β: -0.229, odds ratio [OR]: 0.795, p < 0.05), from a friend (β: -0.292, odds ratio [OR]: 0.747, p < 0.01), and from a relative or a family member (β: -0.242, odds ratio [OR]: 0.785, p < 0.05) negatively predicted the risky driving behaviors which implies that trained drivers are less involved in risky driving behaviors as compared to untrained drivers. Seat belt usage (β: -0.093, odds ratio [OR]: .911, p < 0.05) was found to be significant predictor of risky driving behaviors suggesting that the drivers who use seat belt are less involved in risky driving as compared to those who do not use seatbelt. Furthermore, among demographics, age, gender and driving experience had a significant association with risky driving. The drivers aged 18-24 years (β: 0.150, odds ratio [OR]: 1.161, p < 0.05) and 25-34 years (β: 0.037, odds ratio [OR]: 1.038, p < 0.05) came out to be a significant predictor of risky driving as compared to drivers aged 65 years and above. Male drivers (β: 0.056, odds ratio [OR]: 1.058, p < 0.05) were found to be more risk takers as compared to female drivers. Drivers having an experience of less than one year (β: 0. 53, odds ratio [OR]: 1.055, p < 0.01) and drivers with an experience of 1-5 years (β: 0.151, odds ratio [OR]: 1.163, p < 0.01) were found to be involved in risky driving behaviors as compared to drivers with experience of more than 20 years. While education and travel time could not reach the significance levels. See

Table 6 for detailed information.

The second GLM mode was run to check the associations of predictor variables with negative emotion (NE) dimension of DDDI. The results showed that only age and driving experience were the significant predictors of negative emotional driving. Drivers aged 18-24 years (β: 0.103, odds ratio [OR]: 1.202, p < 0.05), and 25-34 years (β: 0.160, odds ratio [OR]: 1.278, p < 0.05) were found to be the significant positive predictors of negative emotional driving while drivers aged 55-64 years (β: -0.123, odds ratio [OR]: .885, p < 0.05) were found to be a negative predictor of negative emotional driving. Drivers having an experience of 16-20 years (β: --0.165, odds ratio [OR]: .880, p < 0.05) came out to be a significant predictor of negative emotional driving which suggest that drivers having more driving experience are less involved in negative emotional driving as compared to inexperienced drivers. Whereas gender, education, seat belt usage, driving training, driving license and travel time variables were not found to be significant predictor. See

Table 7 for detailed information.

The last GLM model predicted the associations of predictor variables with Aggressive driving dimension of DDDI. The results indicated that gender had a significant association with aggressive driving (β: 0.141, odds ratio [OR]: 1.152, p < 0.01) which suggest that male drivers are found to be involved in aggressive driving more as compared to female drivers. Age was also a significant predictor of aggressive driving. The drivers aged 18-24 years (β: 0.426, odds ratio [OR]: 1.530, p < 0.01), drivers aged 25-34 years (β: 0.360, odds ratio [OR]: 1.434, p < 0.05) and drivers aged 35-44 years (β: 0.413, odds ratio [OR]: 1.511, p < 0.01) came out to be a significant predictor of aggressive driving as compared to drivers with age over 65 years. Drivers with less than 1 year experience (β: .217, odds ratio [OR]: 1.346, p < 0.05) and drivers having an experience of 1-5 years (β: 0.122, odds ratio [OR]: 1.130, p < 0.05) were found to be the significant predictor of aggressive driving as compared to drivers with more than 20 years’ experience. Furthermore, seat belt usage (β: -0.086, odds ratio [OR]: 0.917, p < 0.05) was found to be significant negative predictor of aggressive driving as compared to people who do not use seat belt. Drivers who got training from traffic police driving school (β: -0.242, odds ratio [OR]: 0.785, p < 0.05) were also found to be a significant predictor of aggressive driving behaviors as compared to untrained drivers. Whereas, education, driving license and driving training variables could not reach the significance levels. See

Table 8 for detailed information.

DDDI as a Predictor of Road Traffic Accidents

The primary aim of this section is to investigate the influence of Dula dangerous driving index (DDDI) dimensions, seat belt usage, driving training, and sociodemographic variables on road traffic accidents involvement. Binary logistic regression modelling technique was implied to discover the factors responsible for road traffic accidents. In the model road traffic accidents (RTA) were introduced as dependent variables (DV) and dangerous driving behaviors (DDDI) dimensions as independent variables (IV). The dependent variable coding used in the model is specified as; not involved in an accident on road ever: 0 and involved in an accident on road: 1. Two binary logistic regression models were used to discover the variables responsible for accident engagement. The first binary logistic model was run by incorporating the dangerous driving behaviors (DDDI) together to assess the impact on accident involvement (see

Table 9 for detailed information).

The results implied that aggressive driving (AD) and risky driving (RD) have a positive impact on accident engagement that can be debated as; the drivers engaged in aggressive driving (β: 0.335, p < 0.01) and risky driving (β: 0.198, p < 0.05), have higher probability of accident involvement. In the second binary logistic model all the IVs (including demographic variables, seat belt and driving training) were introduced to assess their impact on accident engagement. The results showed that aggressive driving (β: 0.358, p < 0.01), and risky driving (β: 0.196, p < 0.05) had a significant association with accident involvement. seatbelt usage (β: -0.252, p < 0.05) had a significant association with accident involvement. Among demographics only drivers age (β: -.215, p < 0.01) came out to be a significant predictor of traffic accidents while driving experience and driving training variables did not achieve the significance. See

Table 10 for detailed information.

Comparison of Dangerous Driving Behaviors of Pakistani and Chinese Drivers

Given that road deaths vary among cultures, it is imperative to examine the effects of driving behaviors through cross-cultural comparisons to obtain a greater knowledge of them. These disparities in driving behaviors are probably the result of large cultural differences. For instance, Lajunen, Corry, Summala, and Hartley (1998) discovered that Australian drivers had more accidents and were less concerned with safety than Finnish drivers. In another instance, Warner, Özkan, Lajunen, and Tzamalouka (2011) found that Compared to drivers in Greece and Turkey, drivers in Finland and Sweden report aggressive violations less frequently. Also, it was found that compared to Greek and Turkish drivers, drivers from Finland and Sweden report engaging in aberrant driving behavior and experiencing fewer accidents overall. Furthermore, discrepancies in the quality of the road infrastructure may be associated with differences in driver behavior throughout regions.

Traffic safety has been a major concern for both China and Pakistan as a result of increasing motorization and fast urbanization. In 2021, the total road traffic accidents reported in China were 273, 098 resulting in loss of 62,218 precious lives and 281,447 injuries (National Bureau of statistics 2022). The deaths due to road traffic accident per 100,000 population as reported by Zhao (2009) has increased from 2.1 in year 1980 to 7.60 in year 2005 but the situation as worsen overtime with increased motorization, this fatality rate has reached 18.2 per 100,000 of population in year 2016 (WHO, 2018). Similarly, in Pakistan the road safety issues are on the rise, which is evident from the fact that the fatality rate per 100, 000 of population is 14.3 (WHO, 2018), which is also on the rise.

China and Pakistan have a long friendship history the most recent example of which is the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) project. After the completion of CPEC, cross-border travel will be more frequent. China and Pakistan have different norms and cultures. Cultural differences can be the reason for the differences in driving behaviors between these two nations. By examining these variations, one might learn more about how culture affects traffic safety and perhaps put improvements in place to facilitate cross border travel. However, the fourth objective of this research was to provide an overview of dangerous driving behaviors of Pakistani drivers compared to the Chinese drivers. To achieve this objective, data was gathered from drivers in China using the same questionnaire as was used to collect data from Pakistani drivers. Data collection was performed using the online platform through Wenjuanxing (

https://www.wjx.cn/), the biggest online Chinese survey platform. The Wenjuanxing platform and social networks were used to disseminate the survey link. After spending an average of 17 minutes answering the questionnaire, participants received 10 Chinese Yuan in remuneration. A total of 630 valid samples were collected and included in the comparative analysis. The participants' age ranged from 18 to 65 years (M:2.40, S.D: 0.98), the sample consist of 63.2% male (N:398) and 36.7% female (N: 232) participants. All the participants in sample reported to have a valid driving license and 48% of participants reported of being involved in a traffic accident.

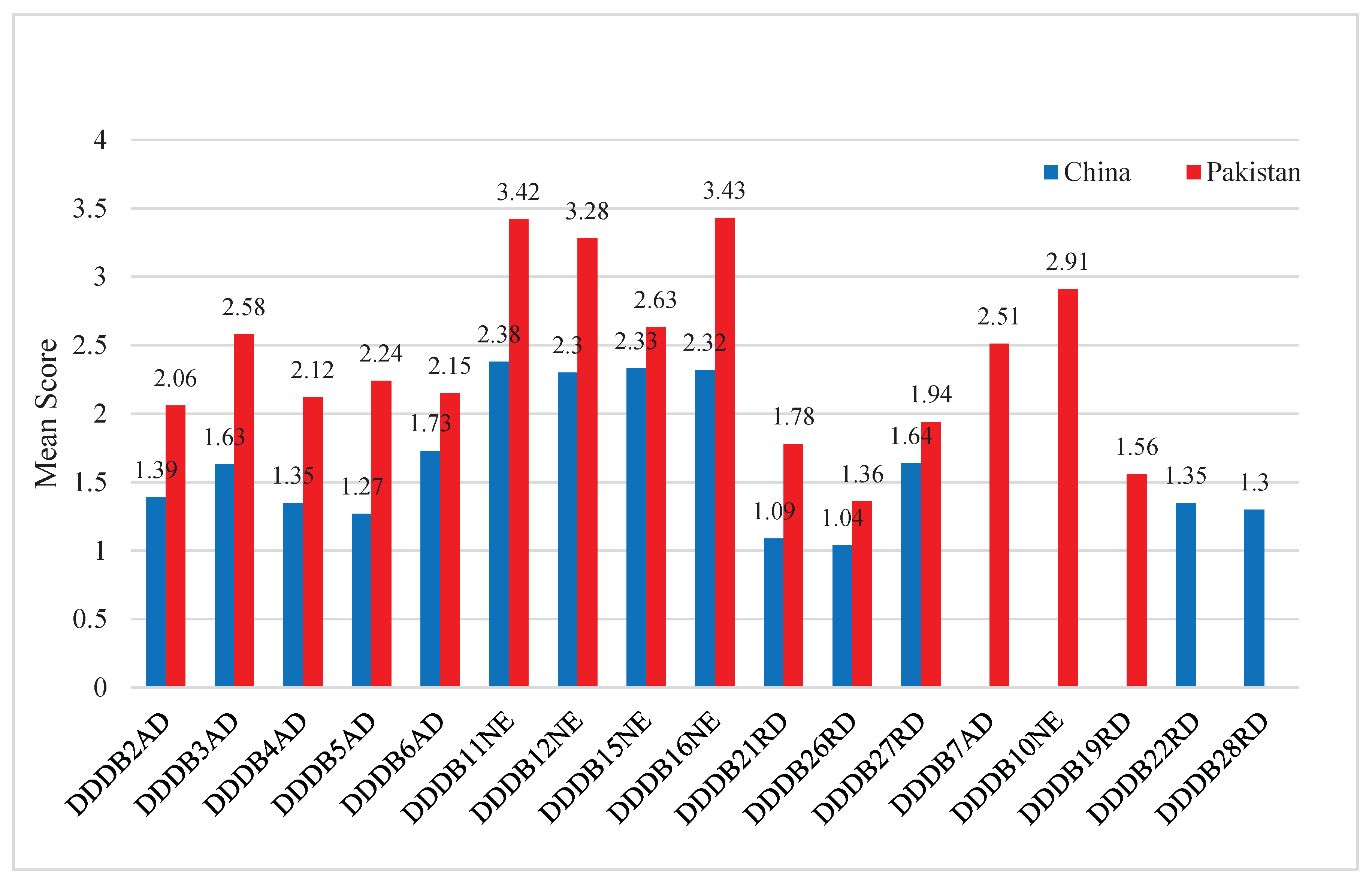

Table 11 compares the mean scores of dangerous driving behaviors of Pakistani drivers and Chinese drivers determined in this study. The results show that Pakistani drivers commit dangerous driving behaviors more frequently compared to Chinese drivers i.e., the mean score of item no 16, “I get irritated when a car/truck in front of me slows down for no reason” for Chinese drivers is 2.32 while, the score for Pakistani drivers is 3.43. similarly, the mean score of item no 3, “I verbally insult drivers who annoys me” for Chinese driver is 1.63 while for Pakistani driver it is 2.58. The item no 11, “when I get stuck in traffic jam, I get irritated” with a mean score of 2.38 is the most reported dangerous driving behavior drivers while, the item no 26, “I consider myself to be a risk taker” is the most least reported driving behavior among the Chinese drivers. Among the Pakistani drivers, the most reported dangerous driving behavior is, item no 16 (mean score: 3.43) and the least reported dangerous driving behavior is, item no 26 (mean score: 1.36). Several items have similar mean scores, for example, item no 21, “I will drive if I am mildly intoxicated or buzzed” have a mean score of 1.09 for Chinese and 1.28 for Pakistani drivers. Figure 2 shows further comparison of dangerous driving behaviors of Pakistani and Chinese drivers. The overall, results show that Chinese drivers behave less dangerously on roads compared to Pakistani driver. The reasons for such trend in China can be attributed to the state-of-the-art road infrastructure, traffic management systems in place and governments policies on road safety whereas, in Pakistan, less attention is paid on road safety.

Discussion

The main purpose of this study was to explore the influence of dangerous driving behaviors, seat belt usage, driving training and demographic variables on accidents involvement in a sample of Pakistani drivers. The DDDI scale has never been used in Pakistan to predict the road accidents or driving behaviors so, the original DDDI scale (Dula & Ballard, 2003) was translated in to Pakistani language (Urdu) its factor structure, reliability and validity was determined. The results showed that the Pakistani version of DDDI possess reliable psychometric qualities. The Pakistani DDDI version had higher reliabilities and a stable structure which can be compared to other DDDI translated versions;(Iliescu & Sarbescu, 2013; Qu et al., 2014; Richer & Bergeron, 2012). The Pakistani DDDI supports a three-factor structure i.e., aggressive driving, risky driving and negative emotional driving which were also in accordance with previous studies, Dula and Ballard (2003); Iliescu and Sarbescu (2013); Richer and Bergeron (2012). Furthermore, to strengthen the empirical validity of Pakistani version of DDDI, traffic accidents and violations (seatbelt usage) were used as criteria. All the DDDI dimensions were positively and strongly correlated with traffic accidents and negatively correlated with seatbelt usage. According to previous studies, both traffic violations and accidents play important roles in predicting dangerous driving behaviors (Lansdown, 2012; Qu et al., 2014). The present results show that these variables are associated with risky driving, aggressive driving, negative emotional driving and overall DDDI score. The results from this study imply that the DDDI is sensitive in its capacity to identify drivers who exhibit dangerous behavior.

The motivation for selecting Pakistan was the increasing number of road accidents and violation of traffic rules (Javed, 2016; A. A. Klair, 2017; A. A. Klair & Arfan, 2014). The problem in Pakistan is that people are hesitant to learn driving from the driving institutes either government or private owned. Instead, their preferred choice is to learn driving from friends or family members. This lack of proper training and knowledge prior to driving leads to increase in road traffic accidents. This fact is eminent considering that in this sample 72.5% participants and 86.7% participants in a previous study (Khaliq et al., 2020) learned driving from friends or family members instead of training institutes. The other very common issue is the non-usage of seat belts while driving, although the compulsory seat belt law exists in country but the implementation is very low. According to a previous study in Pakistan only 20% people use seatbelts while driving, 53% of which is on motorways only (A. A. Klair & Arfan, 2014), while in another study, it was reported that 72.2% of drivers use seatbelts just to avoid fines and penalties and 45.6% drivers feel ashamed to wear a seat belt while driving (Khaliq et al., 2020). The results show that Pakistani drivers drive fast when upset or angry, flash headlights when annoyed by other drivers, perform illegal overtaking moves, show aggression towards others while driving on roads and violate the traffic laws. The involvement in these types of behaviors promotes dangerous driving behaviors which results in traffic accidents. These facts encourage us to study the effect of dangerous driving behaviors on accident involvement among Pakistani drivers.

Figure 1.

Comparison of dangerous driving behaviors.

Figure 1.

Comparison of dangerous driving behaviors.

GLM models and binary logistic regression models were used in this study to identify the predictors of dangerous driving behaviors (DDDI) and accident involvement. The results of GLM models indicated that using a seatbelt while driving had a significant effect on risky driving and aggressive driving. Which can be concluded as the drivers who use seatbelt are less involved in risky and aggressive driving behaviors. Wearing a seat belt raises the risk perception linked with probable accidents. This increased awareness can lead to more cautious driving behavior, such as driving at slower speeds, keeping a safe distance from other vehicles, and following traffic rules. Drivers receiving prior training either from friends, relatives or training institutes negatively influenced the risky driving while, drivers who received training from traffic police driving schools negatively influenced aggressive driving behavior. Whereas, it had no significant influence on negative emotional driving. It can be concluded that drivers who have got training either from a driving school or a friend and family member are less involved in risky and aggressive driving behaviors as compared to drivers without appropriate training. Driving training can improve abilities, improve risk perception, promote responsible attitudes, and build a safety-conscious driving culture, all of which can have a beneficial and long-term impact on dangerous driving behaviors and improve road safety (Mayhew & Simpson, 2002).

Previous literature suggests that sociodemographic variables can describe the dangerous driving behaviors (Iliescu & Sarbescu, 2013). Among sociodemographic variables, age was the significant predictor of risky, negative emotional and aggressive driving. It is believed that younger drivers exhibit more dangerous and risky behaviors as compared to elderly one (Dula & Ballard, 2003; Iliescu & Sarbescu, 2013; Qu et al., 2014), the results of this study were also consistent with previous studies. The reason could be argued as the higher percentage of young drivers (58.7%) in our sample as compared to elderly ones. While, gender (males) was the significant predictor of aggressive and risky driving behaviors only. In our data set female driver representation is very less (18.8%) as compared to males (81.2%). This can also be understood as the number of female drivers in the country are very less due to cultural obligations as compared to men (Zehra, 2017). Males involvement in aggressive driving behaviors was significantly high with regard to females in this study, this is in accordance with previous study (Iliescu & Sarbescu, 2013). Driving experience significantly influenced the aggressive and risky driving behavior while having no significant influence on negative emotional driving. It can be concluded that young and inexperienced drivers were more involved in aggressive driving behaviors as reported in previous studies by Ellison-Potter, Bell, and Deffenbacher (2001) and Iliescu and Sarbescu (2013) as well. Therefore, it could be argued that age, gender, lack of driving training, inexperience and non-usage of seat belt are the significant predictors of dangerous driving behaviors among Pakistani drivers.

To find the predictors of accident involvement, the dangerous driving behaviors, socio demographic variables, sea belt, driving license and driving training were introduced into binary logistic regression model. Accident involvement was introduced as dependent variable while others (dangerous driving behaviors, socio demographic variables, sea belt, driving license and driver training) as independent variable in the model. Aggressive driving and risky driving were found to be the significant predictor of accident involvement. Whereas, negative emotional driving showed no significant influence on accident involvement. Aggressive and risky driving behavior has been reported as a significant contributor of traffic accident by various previous researches as well (Mohammadpour & Nassiri, 2021; Sullman, Stephens, & Yong, 2015; Wickens, Mann, Ialomiteanu, & Stoduto, 2016). Many studies concluded that sociodemographic variables are predictors of traffic accidents (M. Hussain & Shi, 2020; Lourens, Vissers, & Jessurun, 1999; Shi, Bai, Ying, & Atchley, 2010). Sociodemographic variables along with seatbelt and driver training variables were also studied to predict the traffic accidents in this study. Using seat belt while driving (as a predictor variable) negatively effects the traffic accidents. It can be argued that people violating the seat belt usage law are more involved in traffic accidents (severe injury) as compared to those who abide by this law which is consistent with the fact that in USA, out of all the vehicle occupants killed 51.1% were not wearing seat belt during year 2020 (National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, 2021). The seat belt usage law (Governemnt of Pakistan, 1965) exists in country but its implementation is limited i.e. is only on highways and motorways under the control of national highway and motorway police (NH&MP) while on local roads or roads with less importance the implementation level is very low (Khan & Fatmi, 2014; A. A. Klair & Arfan, 2014). The act of fastening a seat belt can serve as a reminder of the significance of driving safely and responsibly. This mental association can deter drivers from engaging in risky behavior by reminding them that they have done one vital safety precaution. Among demographic variables, only drivers age was found to be a significant negative predictor of traffic accidents. Which can be argued as the with the increase in drivers age the probability of involvement in traffic accidents reduces as reported by (Regev, Rolison, & Moutari, 2018).

One of the objectives of this study was to give an overview of the Pakistani and Chinese driver’s dangerous driving behaviors. Compared to Chinese drivers Pakistani drivers are found to be more aggressive and risk takers which, is also evident from the mean item score comparison between both countries. The possible reason for such a trend can be attributed to the lack of comprehensive and standardized driving training and education programs, in consistent enforcement of traffic laws, the quality of road infrastructure and lack of public awareness campaigns. The Chinese drivers on the other hand are found to be more disciplined and less aggressive due to the stringent measures being taken in country to improve road safety. Therefore, it can be concluded that Pakistani drivers are more aggressive and risk takers, which poses a significant threat to the road safety for cross border travels between both countries after the completion of CPEC project.

Limitations

The current study has a few limitations. The main limitation is the dependence on drivers’ self-reports to determine accidents and illicit driving behaviors, a cost-effective method but often presumed to be biased. Although, the findings of our study were based on 623 respondents (81.2% male respondents) in which female representation is very limited therefore, we strongly presume that future researches with increased female representation could better implicate the results for whole population. This DDDI measure is studied for the first time in Pakistan, so more research work is advocated to validate it for country with specific focus on negative emotional driving.

Implications

The current study is the first to utilize the Dula dangerous driving index (DDDI) to identify the dangerous driving behaviors in Pakistan. In context of Pakistani drivers dangerous driving behaviors, the DDDI demonstrates good internal consistency and validity. Thus, the DDDI is useful tool for Pakistani researchers examining the driving behaviors. Also, this study used seatbelt and driving training as predictors of dangerous driving behaviors and road traffic accidents first time in context of Pakistani drivers. The study also offers important practical suggestions for improving road safety and accident reduction. The road safety agencies and authorities can further improve the road safety in the country by utilizing the findings of this study which provides ample knowledge about the dangerous driving behaviors of Pakistani drivers. Based on the findings it is recommended that current policies related to road safety should be revised to promote safer transportation system at the cost of minimal casualties. It is also highlighted that transportation agencies should make interventions in order to give safe and effective transportation system for general public. In order to control dangerous driving behaviors, government officials must get insight from comparable experiences in other nations e.g., China.

Author Contributions

For “Conceptualization, A. Yousaf. and J. Wu.; methodology, A. Yousaf. and J. Wu.; software, A. Yousaf., A. moiz., L. Sethi. and S. A. Khan.; validation, A. Yousaf. and J. Wu.; formal analysis, A. Yousaf. and A. moiz.; investigation, A. Yousaf., A. moiz., L. Sethi. and S. A. Khan; resources J. Wu; data curation, A. Yousaf., A moiz., L. Sethi. and S. A. Khan.; writing—original draft preparation, A. Yousaf. and J. Wu.; writing—review and editing A. Yousaf. and J. Wu.; visualization, A. Yousaf. and J. Wu.; supervision, J. Wu.; project administration, J. Wu All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”.

Funding

“This research received no external funding”

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge the technical support provided by STARS (A Socio-Technical Approach to Road Safety) team.

Conflict of interest:

“The others declare no conflict of interest.”

References

- Batool, Z.; Carsten, O. Attitudinal Determinants of Aberrant Driving Behaviors in Pakistan. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2016, 2602, 52–59,. [CrossRef]

- Batool, Z.; Carsten, O. Self-reported dimensions of aberrant behaviours among drivers in Pakistan. Transp. Res. Part F: Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2017, 47, 176–186,. [CrossRef]

- Bucsuházy, K.; Matuchová, E.; Zůvala, R.; Moravcová, P.; Kostíková, M.; Mikulec, R. Human factors contributing to the road traffic accident occurrence. Transp. Res. Procedia 2020, 45, 555–561,. [CrossRef]

- Dahlen, E.R.; White, R.P. The Big Five factors, sensation seeking, and driving anger in the prediction of unsafe driving. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2006, 41, 903–915,. [CrossRef]

- Deffenbacher, J.L.; Lynch, R.S.; Oetting, E.R.; Swaim, R.C. The Driving Anger Expression Inventory: a measure of how people express their anger on the road. Behav. Res. Ther. 2002, 40, 717–737,. [CrossRef]

- Dula, C.S.; Ballard, M.E. Development and Evaluation of a Measure of Dangerous, Aggressive, Negative Emotional, and Risky Driving1. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 33, 263–282,. [CrossRef]

- Dunn, P. K. (2023). Generalized linear models⋆. In R; Elsevier: J. Tierney, F. Rizvi, & K. Ercikan (Eds.), International Encyclopedia of Education (Fourth Edition) (pp. 583-589). Oxford.

- Ellison-Potter, P.; Bell, P.; Deffenbacher, J. The Effects of Trait Driving Anger, Anonymity, and Aggressive Stimuli on Aggressive Driving Behavior. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 31, 431–443,. [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, G.; Sayer, I. Road accidents in developing countries. Accid. Anal. Prev. 1983, 15, 337–353,. [CrossRef]

- Motor Vehicle Ordinance (MVO), § 89A, 89B (1965).

- Hussain, M.; Shi, J. Effects of proper driving training and driving license on aberrant driving behaviors of Pakistani drivers–A Proportional Odds approach. J. Transp. Saf. Secur. 2019, 13, 661–679,. [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.; Shi, J.; Batool, Z. An investigation of the effects of motorcycle-riding experience on aberrant driving behaviors and road traffic accidents-A case study of Pakistan. Int. J. Crashworthiness 2020, 27, 70–79,. [CrossRef]

- Iliescu, D.; Sârbescu, P. The relationship of dangerous driving with traffic offenses: A study on an adapted measure of dangerous driving. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2013, 51, 33–41,. [CrossRef]

- Iversen, H.; Rundmo, T. Personality, risky driving and accident involvement among Norwegian drivers. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2002, 33, 1251–1263,. [CrossRef]

-

Javed, A. (2016). Driving licences issuance through agents. The Nation. Retrieved from https://www.nation.com.pk/09-Mar-2016/driving-licences-issuance-through-agents.

- Khaliq, A. , Khan, M. N., Ahmad, F., Khattak, F. A., Ullah, I., Akram, M.,... Haq, Z. U. (2020). Seat-belt use and associated factors among drivers and front passengers in the metropolitan city of Peshawar, Pakistan: A cross sectional study. Critical Care Innovations, 3(2), 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Khan, A. A., & Fatmi, Z. (2014). Strategies for Prevention of Road Traffic Injuries (RTIs) in Pakistan: Situational Analysis. Jcpsp-Journal of the College of Physicians and Surgeons Pakistan, 24(5), 356-360. Retrieved from <Go to ISI=://WOS:000336420200014.

- Klair, A., & Arfan, M. (2017). TRENDS, PATTERNS AND CAUSES OF ROAD ACCIDENTS ON N-5, NORTH-3, PAKISTAN: A DECADE STUDY (2006-2015).

-

Klair, A. A. (2017, 25 Decenver,2022). Risky behaviours of motorised two-wheelers. The News International. Retrieved from https://www.thenews.com.pk/print/257766-risky-behaviours-of-motorised-two-wheelers.

- Klair, A.A.; Arfan, M. Use of Seat Belt and Enforcement of Seat Belt Laws in Pakistan. Traffic Inj. Prev. 2013, 15, 706–710,. [CrossRef]

- Lajunen, T.; Corry, A.; Summala, H.; Hartley, L. Cross-cultural differences in Drivers' self-assessments of their perceptual-motor and safety skills: Australians and Finns. Pers. Individ. Differ. 1998, 24, 539–550,. [CrossRef]

- Lansdown, T.C. Individual differences and propensity to engage with in-vehicle distractions – A self-report survey. Transp. Res. Part F: Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2012, 15, 1–8,. [CrossRef]

- Lourens, P.F.; Vissers, J.A.; Jessurun, M. Annual mileage, driving violations, and accident involvement in relation to drivers’ sex, age, and level of education. Accid. Anal. Prev. 1999, 31, 593–597,. [CrossRef]

- Mayhew, D. R., & Simpson, H. M. (2002). The safety value of driver education and training. Injury prevention : journal of the International Society for Child and Adolescent Injury Prevention, 8 Suppl 2, ii3-7; discussion ii7-8. Retrieved from ://.

- McCullagh, P. a. N., J.A. (1989). Generalized Linear Models (2nd Edition ed.). London: Chapman and Hall.

- Mohammadpour, S.I.; Nassiri, H. Aggressive driving: Do driving overconfidence and aggressive thoughts behind the wheel, drive professionals off the road? Transp. Res. Part F: Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2021, 79, 170–184,. [CrossRef]

-

National Bureau of statistics, N. C. (2022). China Statistical Year Book 2022. China: China Statistics Press Retrieved from http://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/ndsj/2022/indexeh.htm.

-

National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, N. (2021). Seat belts. Retrieved from https://www.nhtsa.gov/risky-driving/seat-belts. Retrieved 1/08/2023, from United States Department of Transportation https://www.nhtsa.gov/risky-driving/seat-belts.

- PBS. (2020). Pakistan Statistical Year Book 2020. Pakistan: Ministru of Planning Development and Special Initiatives Retrieved from www.pbs.gov.pk.

- Peck, R.C. Do driver training programs reduce crashes and traffic violations? — A critical examination of the literature. IATSS Res. 2011, 34, 63–71,. [CrossRef]

- Qu, W.; Ge, Y.; Jiang, C.; Du, F.; Zhang, K. The Dula Dangerous Driving Index in China: An investigation of reliability and validity. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2014, 64, 62–68,. [CrossRef]

- Reason, J.; Manstead, A.; Stradling, S.; Baxter, J.; Campbell, K. ERRORS AND VIOLATIONS ON THE ROADS - A REAL DISTINCTION? Ergonomics 1990, 33, 1315–1332,. [CrossRef]

- Regev, S.; Rolison, J.J.; Moutari, S. Crash risk by driver age, gender, and time of day using a new exposure methodology. J. Saf. Res. 2018, 66, 131–140,. [CrossRef]

- Richer, I.; Bergeron, J. Differentiating risky and aggressive driving: Further support of the internal validity of the Dula Dangerous Driving Index. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2012, 45, 620–627,. [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Bai, Y.; Ying, X.; Atchley, P. Aberrant driving behaviors: A study of drivers in Beijing. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2010, 42, 1031–1040,. [CrossRef]

- Smyth, P. K. D. G. K. (2018). Generalized Linear Models With Examples in R (L. Springer Science+Business Media, part of Springer Nature 2018 Ed. 1 ed. Vol. 1). New York, NY: Springer New York, NY.

- Sullman, M.J.; Stephens, A.N.; Yong, M. Anger, aggression and road rage behaviour in Malaysian drivers. Transp. Res. Part F: Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2015, 29, 70–82,. [CrossRef]

- Warner, H.W.; Özkan, T.; Lajunen, T.; Tzamalouka, G. Cross-cultural comparison of drivers’ tendency to commit different aberrant driving behaviours. Transp. Res. Part F: Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2011, 14, 390–399,. [CrossRef]

- WHO. (2018). WHO Global status report on road safety 2018. Retrieved from Geneva Switzerland:.

- Wickens, C.M.; Mann, R.E.; Ialomiteanu, A.R.; Stoduto, G. Do driver anger and aggression contribute to the odds of a crash? A population-level analysis. Transp. Res. Part F: Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2016, 42, 389–399,. [CrossRef]

- Willemsen, J.; Dula, C.S.; Declercq, F.; Verhaeghe, P. The Dula Dangerous Driving Index: An investigation of reliability and validity across cultures. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2008, 40, 798–806,. [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.F. Commentary: Next Steps for Graduated Licensing. Traffic Inj. Prev. 2005, 6, 199–201,. [CrossRef]

-

Zehra, A. (2017). Negative perceptions about female drivers in Pakistan. Retrieved from https://pamirtimes.net/2017/04/24/negative-perception-about-female-drivers-in-pakistan/. Retrieved 30 December,2022 https://pamirtimes.net/2017/04/24/negative-perception-about-female-drivers-in-pakistan/.

- Zhao, S. Road Traffic Accidents in China. IATSS Res. 2009, 33, 125–127,. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).