Submitted:

05 May 2024

Posted:

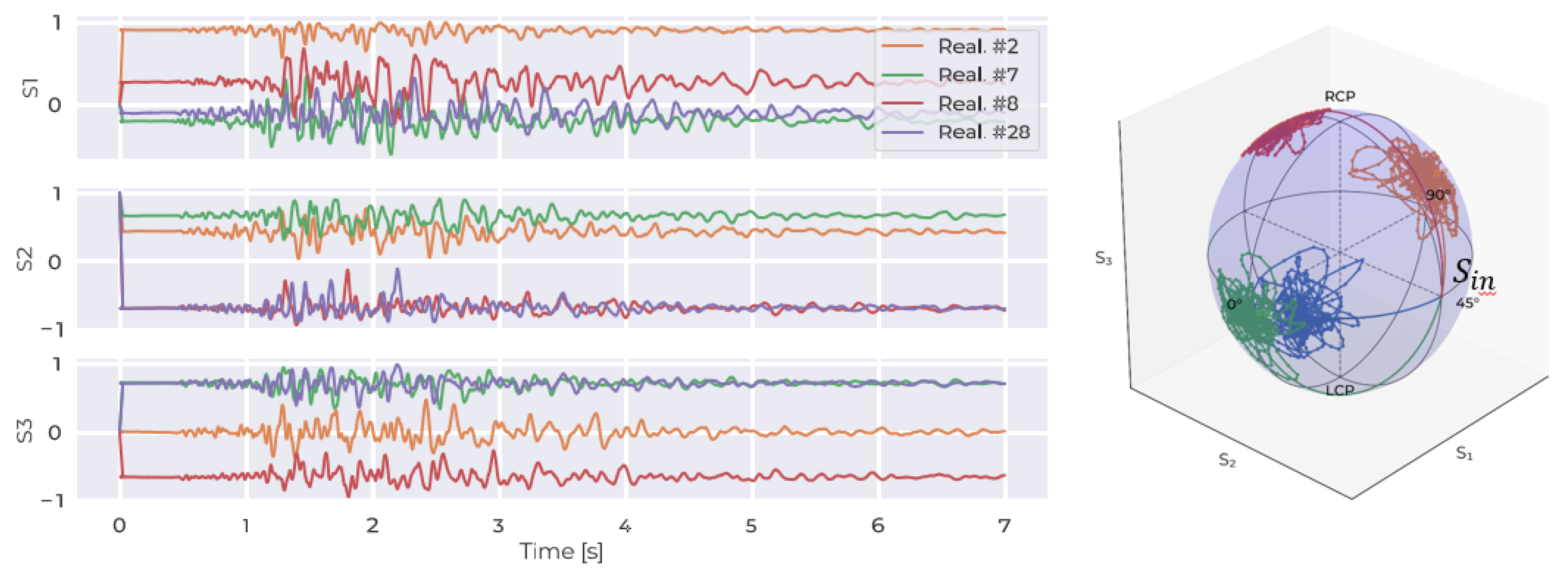

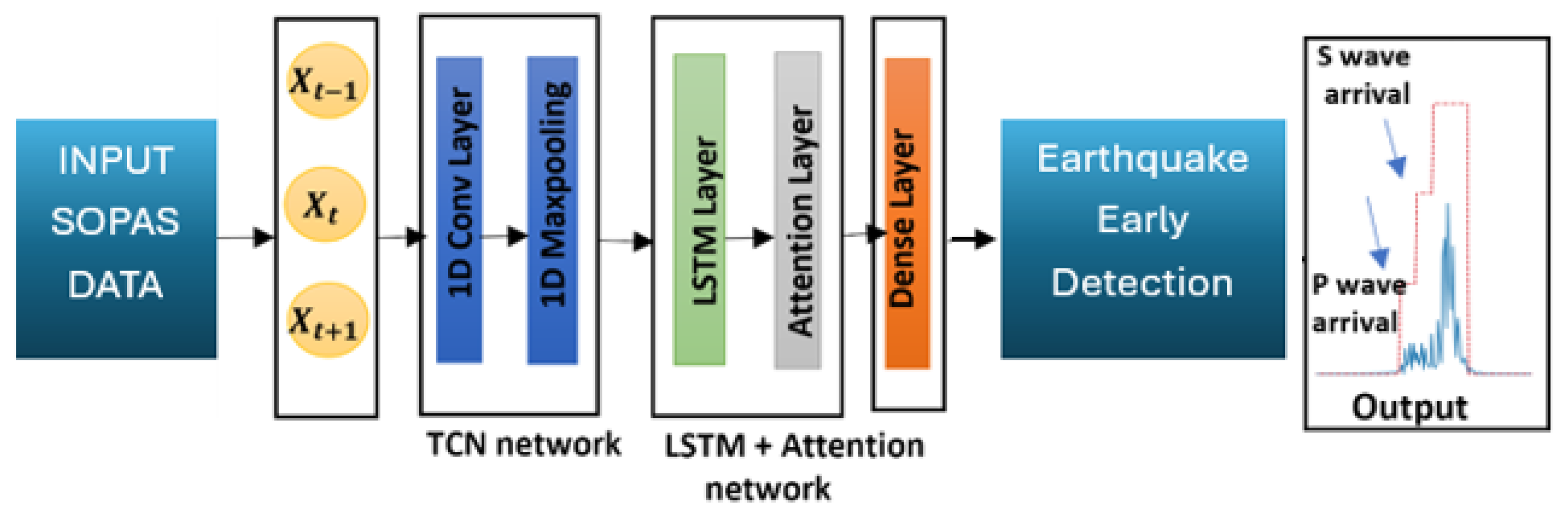

07 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

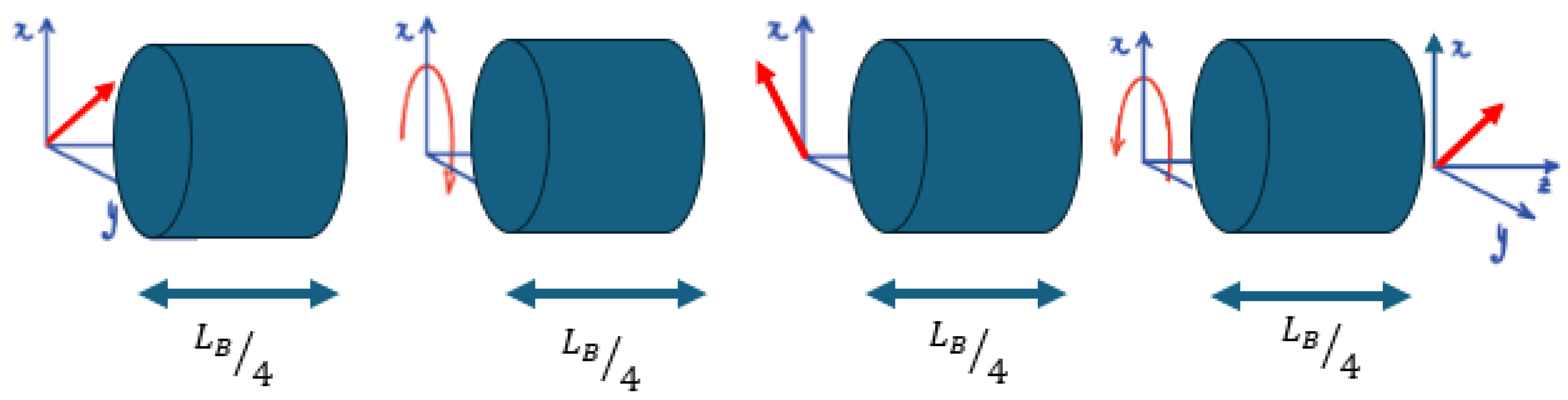

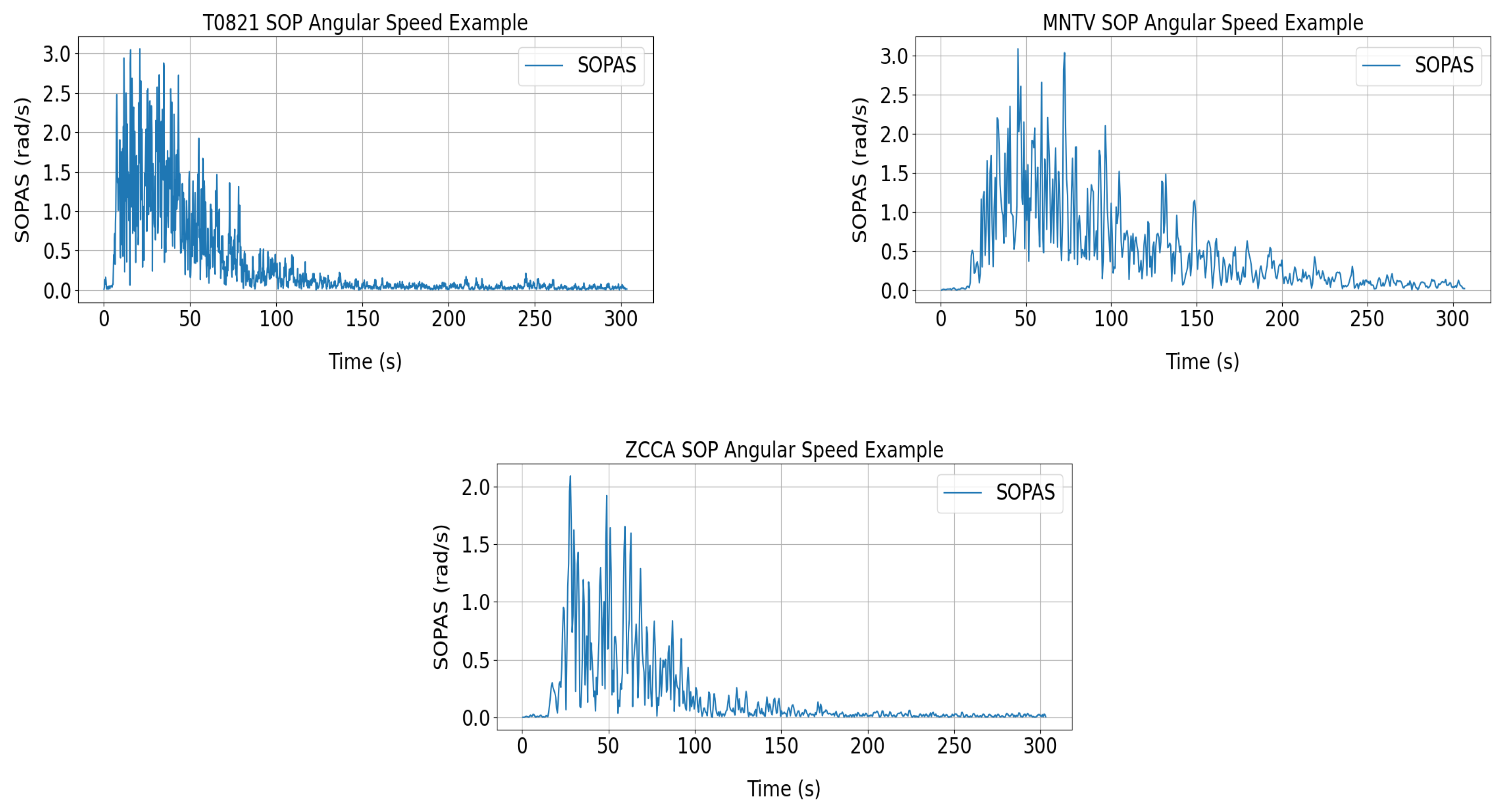

2. Waveplate Model

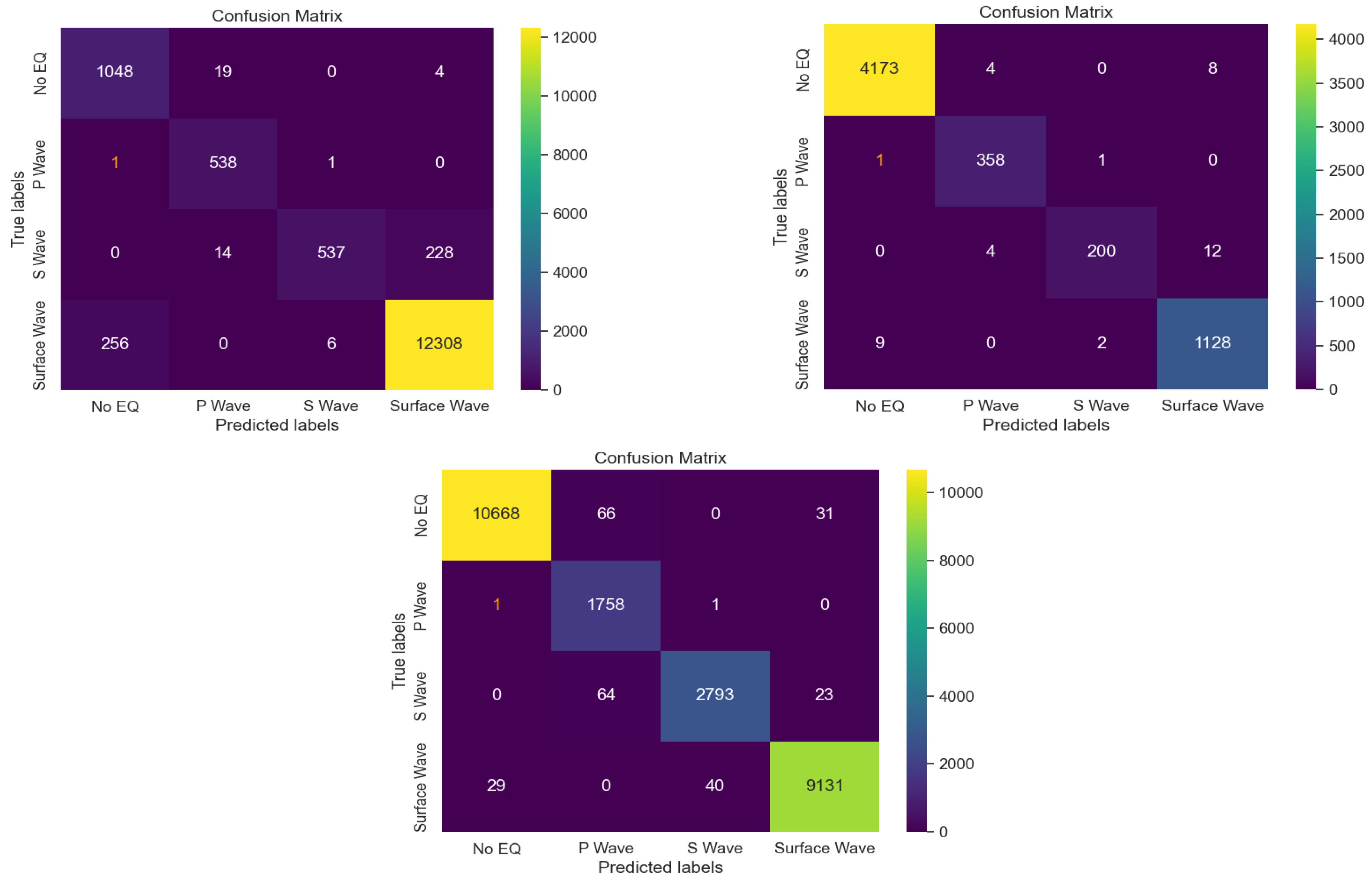

3. Machine Learning Model Training and Validation

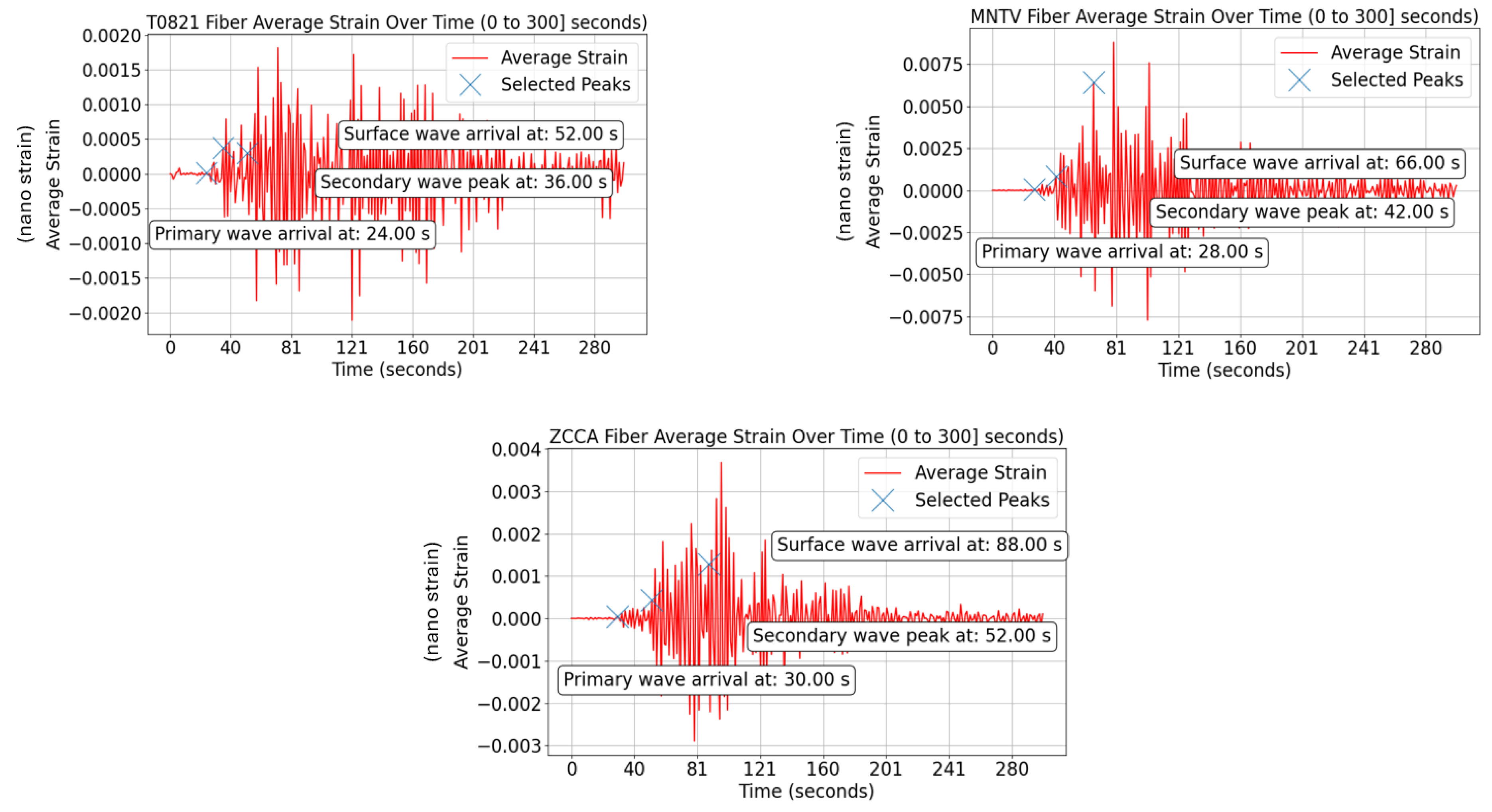

4. Smart Sensing Grid Approach: Seismic Network Implementation

4.1. Case Scenario

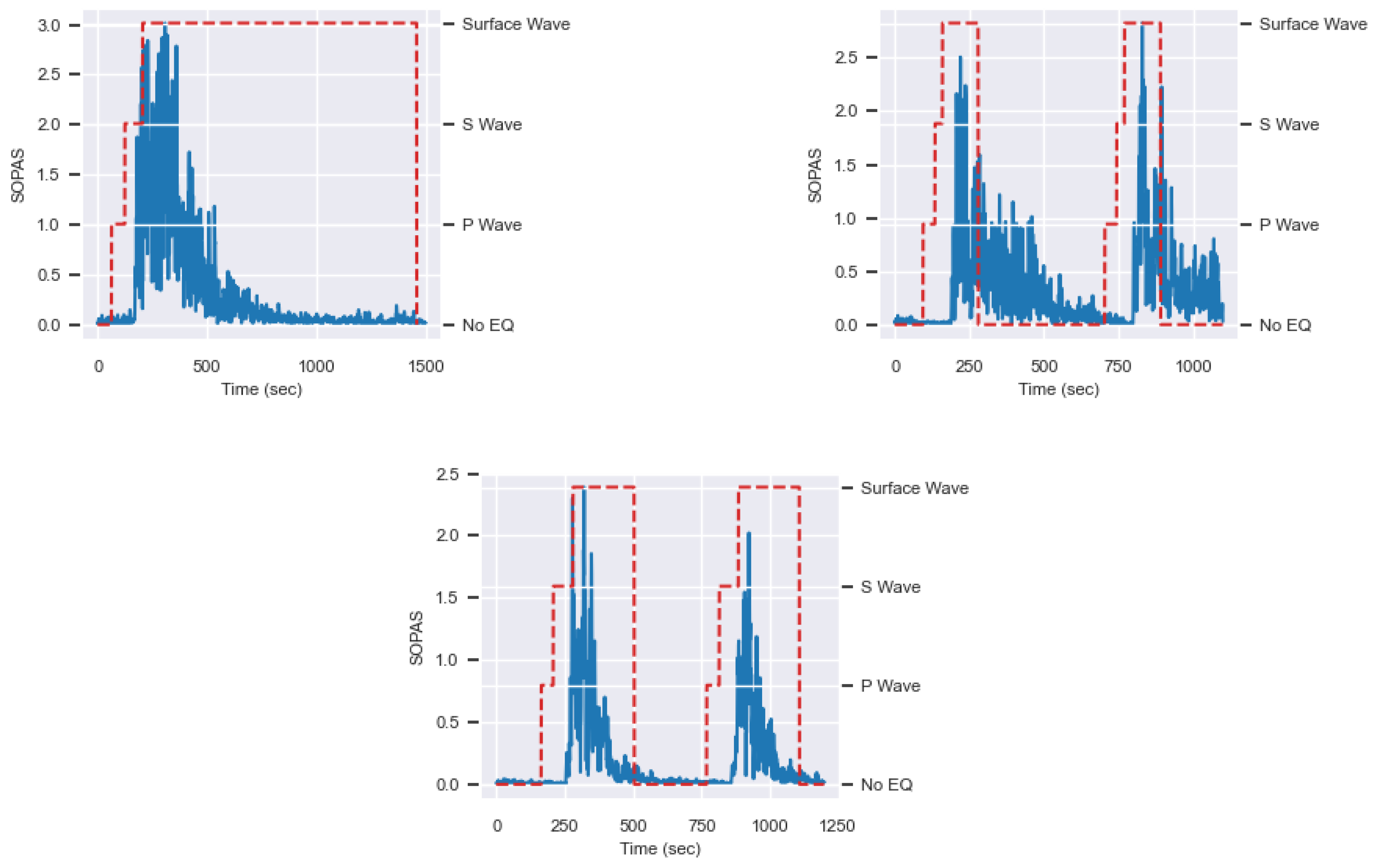

4.2. ML Model Testing Results

5. Triangulation Method for Localization Purposes

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SAFOD | San Andreas Fault Observatory at Depth |

| GPS | Global Positioning System |

| IASPEI | International Association of Seismology and Physics of the Earth’s Interior |

| P waves | Primary waves |

| S waves | Secondary waves |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| OTDR | Optical Time Domain Reflectometer |

| OFDR | Optical Frequency Domain Reflectometry |

| DAS | Distributed Acoustic Sensing |

| SOP | State of Polarization |

| SOPAS | State of Polarization Angular Speed |

| INGV | National Institute of Geophysics and Volcanology |

| CIA | Central Italian Apennines |

| ONC | Optical Network Controller |

| API | Application Programming Interface |

| NE | Network Element |

| ROADM | Re-configurable Optical Add-Drop Multiplexer |

| TRX | Transceiver |

| OSC | Optical Supervisory Channel |

| IM-DD | Intensity Modulated-Direct Detected |

| PBS | Polarization Beam Splitter |

| LSTM | Long Short - Term Memory |

| UTC | Coordinated Universal Time |

Appendix A. Waveplate Model Theory

Appendix B. State of Polarization Angular Speed (SOPAS) Theorem

References

- He, M.; Ren, S.; Tao, Z. Cross-fault Newton force measurement for Earthquake prediction. Rock Mechanics Bulletin 2022, 1, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.; Conin, M.; Moore, J.; Chester, F; Nakamura, Y. ; Mori, J; Anderson, L; Brodsky, E. Stress State in the Largest Displacement Area of the 2011 Tohoku-Oki Earthquake. Science 2013, 339, 687–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hickman, S; Zoback, M. Stress orientations and Magnitudes in the SAFOD Pilot Hole. Advanced Earth and Space Sciences 2004, 31, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Ishii, H.; Asai, Y. Development of a Borehole Stress Meter for Studying Earthquake Predictions and Rock Mechanics, and Stress Seismograms of the 2011 Tohoku Earthquake (M 9.0). SpringerOpen 2015, 67, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gladwin, M. High-Precision Multicomponent Borehole Deformation Monitoring. American Institute of Physics 1984, 55, 2011–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M; Zhang, C; Fan, T. Stress State of the Baoxing Segment of the Southwestern Longmenshan Fault Zone before and after the Ms 7.0 Lushan Earthquake. Asian Earth Sciences 2016, 121, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinlai, X; Zhaohua, X. Infrasound waves caused by earthquake on 12 July 1993 in Japan. Acta Acustica 1996, 12, 55–61. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, R; Kanamori, H. The Potential for Earthquake Early Warning in Southern California. Science 2003, 300, 786–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geller, R; Jackson, D; Kagan, Y; Mulargia, F. Earthquakes Cannot Be Predicted. Science 1997, 275, 1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, T.; Chen, Y.; Gasparini, P.; Madariaga, R.; Main, I.G.; Marzocchi, W.; Papadopoulos, G.A.; Sobolev, G.A.; Yamaoka, K.; Zschau, J. Operational Earthquake Forecasting: State of Knowledge and Guidelines for Utilization. Annals of Geophysics 2011, 54, 316–391. [Google Scholar]

- Mecozzi, A; Antonelli, C; Mazur, M; Fontaine, N; Chen, H; Dallachiesa, L; Ryf, R. Use of Optical Coherent Detection for Environmental Sensing. Journal of Lightwave Technology 2023, 41, 3350–3357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazur,M;Parkin,N;Ryf,R;Iqbal,A;Wright,P;Farrow,K;Fontaine,N;Börjeson,E;Kim,K;Dallachiesa,L; Chen, H;Larsson-Edefors,P;Lord,A;Neilson,D.ContinuousFiberSensingoverField-DeployedMetro Link usingReal-TimeCoherentTransceiverandDAS.InProceedingsoftheEuropeanConferenceonOptical Communication (ECOC),Basel,Switzerland,(18September2022)

- Kulhánek, O. Seismic Waves. In Anatomy of Seismograms, 1st ed; Elsevier Science: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 1990. 18,pp.13–45. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Ruiz, M; Soto, M; Williams, E; Martin-Lopez, S; Zhan, Z; Gonzalez-Herraez, M; Martins, H. Distributed Acoustic Sensing for Seismic Activity Monitoring. APL Photonics 2020, 5, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Boffi, P. Sensing Applications in Deployed Telecommunication Fiber Infrastructures. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Optical Communication (ECOC), Basel, Switzerland, (18 September 2022). [Google Scholar]

- Eiselt, M.; Azendorf, F.; Sandmann, A. Optical Fiber for Remote Sensing with High Spatial Resolution. In Proceedings of the EASS 2022; 11th GMM-Symposium, Erfurt, Germany, (05 July 2022).

- Fichtner, A.; Bogris, A.; Nikas, T.; Bowden, D.; Lentas, K.; Melis, N.S.; Simos, C.; Simos, I.; Smolinski, K. Theory of Phase Transmission Fibre-Optic Deformation Sensing. Geophysical Journal International 2022, 231, 1031–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrier, S. High Bandwidth Detection of Mechanical Stress in Optical Fibre Using Coherent Detection of Rayleigh Scattering. PhD Thesis, Institut polytechnique de Paris, Paris, France, 03 February 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, B; Popescu, A; Tribaldos, V; Byna, S; Ajo-Franklin, J; Wu, K. Real-Time and Post-Hoc Compression for Data from Distributed Acoustic Sensing. Computers & Geosciences 2022, 166, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Lellouch, A; Yuan, S; Ellsworth, W; Biondi, B. Velocity-based Earthquake Detection using Downhole Distributed Acoustic Sensing—Examples from the San Andreas Fault Observatory at Depthvelocity-based Earthquake Detection using Downhole Distributed Acoustic Sensing. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America 2019, 109, 2491–2500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marra, G; Clivati, C; Luckett, R; Tampellini, A; Kronjäger, J; Wright, L; Mura, A; Levi, F; Robinson, S; Xuereb, A; Bapite, B; Calonico, D. Ultrastable Laser Interferometry for Earthquake Detection with Terrestrial and Submarine Cables. Science 2018, 361, 486–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantono, M; Castellanos, J; Batthacharya, S; Yin, S; Zhan, Z; Mecozzi, A; Kamalov; V. Optical Network Sensing: Opportunities and Challenges. In Proceedings of the Optical Fiber Communication Conference (OFC) 2022; San Diego, California, United States, (06 March 2022).

- Barcik, P; Munster, P. Measurement of Slow and Fast Polarization Transients on a Fiber-Optic Testbed. OPTICA 2020, 10, 15250–15257. [Google Scholar]

- Zhan, Z; Cantono, M; Kamalov, V; Mecozzi, A; Müller, R; Yin, S; Castellanos, J. Supplementary Materials for Optical Polarization–Based Seismic and Water Wave Sensing on Transoceanic Cables. Science 2021, 371, 931–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhan, Z; Cantono, M; Kamalov, V; Mecozzi, A; Müller, R; Yin, S; Castellanos, J. Optical Polarization–Based Seismic and Water Wave Sensing on Transoceanic Cables. Science 2021, 371, 931–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curti, F; Daino, B; De Marchis, G; Matera, F. Statistical Treatment of the Evolution of the Principal States of Polarization in Single-Mode Fibers. Journal of Lightwave Technology 1990, 8, 1162–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, S; Rizzelli, G; Barla, M; Gaudino, R. Algorithm Optimization for Rockfalls Alarm System Based on Fiber Polarization Sensing. IEEE Photonics Journal 2023, 15, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Feigl, K. Overview and Preliminary Results from the PoroTomo Project at Brady Hot Springs, Nevada: Poroelastic Tomography by Adjoint Inverse Modeling of Data from Seismology, Geodesy, and Hydrology. In Proceedings of the 42nd Workshop on Geothermal Reservoir Engineering 2017; Stanford, California, United States, (13 February 2022). [Google Scholar]

- Italian National Institute of Geophysics and Volcanology (INGV). Available online: http://ismd.mi.ingv.it/ismd.php?tipo=lista (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- H, Li; T, Qiu. Continuous Manufacturing Process Sequential Prediction using Temporal Convolutional Network. Computer Aided Chemical Engineering 2022, 49, 1789–1794. [Google Scholar]

- Hochreiter, S; Schmidhuber, J. Seismic Waves. In Long Short-Term Memory, Neural Computation, MIT Press: Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1997; 9, pp.:1735–1780.

- 18 September 2022, Bratovich, R; Martinez, F; Straullu, S; Virgillito, E; Castoldi, A; D’Amico, A; Aquilino, F; Pastorelli, R; Curri, V. Surveillance of Metropolitan Anthropic Activities by WDM 10G Optical Data Channels. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Optical Communication (ECOC) 2022; Basel, Switzerland, ().

- 02 July 2023, Virgillito, E; Straullu, S; Aquilino, F; Bratovich, R; Awad, H; Proietti, R; D’Amico, A; Pastorelli, R; Curri, V. Detection, Localization and Emulation of Environmental Activities Using SOP Monitoring of IMDD Optical Data Channels. In Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on Transparent Optical Networks (ICTON) 2023; Bucharest, Romania, ().

- 13 November 2022, Straullu, S; Aquilino, F; Bratovich, R; Rodriguez, F; D’Amico, A; Virgillito, E; Pastorelli, R; Curri, V. Real-time Detection of Anthropic Events by 10G Channels in Metro Network Segments. In Proceedings of the IEEE Photonics Conference (IPC) 2022; Vancouver, Canada, ().

- Herrman, R; Malagnini, L; Munafò, I. Regional Moment Tensors of the 2009 L’Aquila Earthquake Sequence. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America 2009, 101, 975–993. [Google Scholar]

| Epicenter Location | Station to Epicenter Distance (km) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Longitude | Latitude | MNTV | ZCCA | T0821 | |

| INGV Recording | 11.251 | 44.868 | 47.88 | 61.45 | 23.14 |

| Triangulation Simulator | 11.2846 | 44.8705 | 49.59 | 63.08 | 20.48 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).