Submitted:

14 March 2024

Posted:

15 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

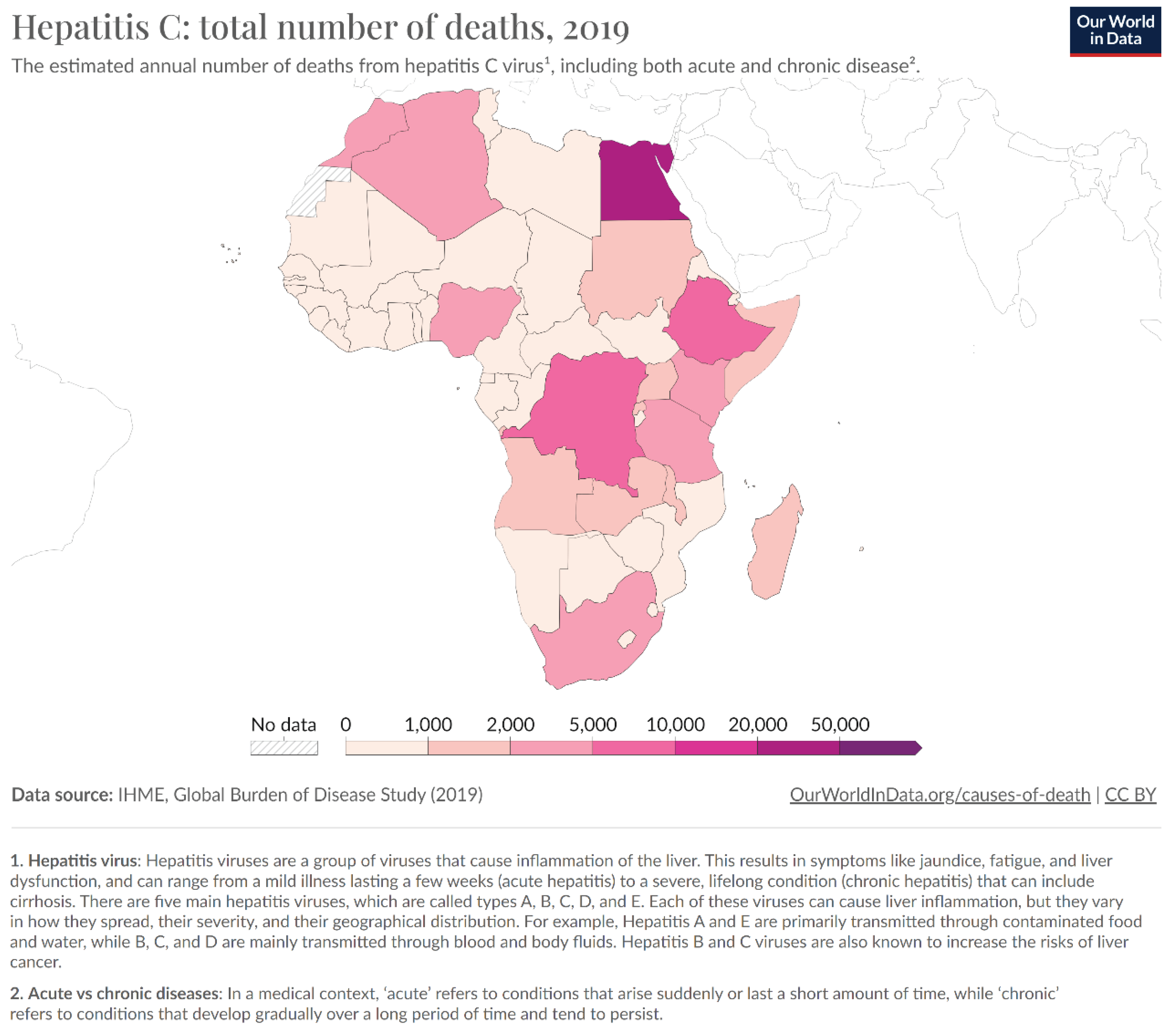

Prevalence of Hepatitis C in Africa

Strategies to Eradicate Hepatitis C in Africa

Lessons to Learn from Egypt’s Hepatitis C Elimination Program and Recommendations to Other African Countries

- o

- Conduct a situation analysis and a gap assessment to understand the magnitude and characteristics of the hepatitis C epidemic, and the strengths and weaknesses of the existing response. This could include conducting seroprevalence surveys, reviewing policies and guidelines, and mapping stakeholders and resources [16,39].

- o

- o

- Establish a national coordination mechanism and a governance structure to oversee and monitor the program, and to ensure accountability and transparency. This could include setting up a national committee or a technical working group, involving representatives from the government, civil society, academia, and development partners

- o

- Mobilize domestic and external resources and partnerships to finance and implement hepatitis C elimination programs, and to leverage existing platforms and initiatives. This could include advocating for increased budget allocation, applying for grants from the Global Fund and other donors, negotiating with pharmaceutical companies for price reductions and voluntary licenses, and collaborating with other health programs such as HIV, tuberculosis, and noncommunicable diseases [18,29,34,38].

- o

- Implement hepatitis C elimination programs in a phased and prioritized manner, starting with the most affected and vulnerable populations and areas, and scaling up gradually and systematically [11,13,41,42]. The programs should cover the following components: screening, diagnosis, treatment, prevention, and surveillance, and should use a patient-centered and human rights-based approach.

- o

- Strengthen health systems and health workforce capacity to deliver quality and safe hepatitis C services, and to ensure the availability and accessibility of diagnostics and medicines [24,26,43]. This could include training and motivating health workers, improving infection control and blood safety practices, and enhancing supply chain and logistics management.

- o

- Monitor and evaluate the program's progress and impact, using a robust and standardized data collection and reporting system, and applying the WHO validation criteria and tools [18,26]. The program should also conduct regular reviews and evaluations and disseminate and use the findings and lessons learned to improve the program.

- o

- Enhance public awareness and community engagement to increase the demand and uptake of hepatitis C services, and to address stigma and discrimination against people living with or at risk of hepatitis C. This could include conducting social and behavior change communication campaigns, providing accurate and reliable information, and involving civil society organizations, religious groups, and celebrities in the program [44,45].

Conclusion

References

- WHO, “Hepatitis C.” Accessed: Jan. 16, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hepatitis-c.

- M. W. Sonderup et al., “Hepatitis C in sub-Saharan Africa: the current status and recommendations for achieving elimination by 2030,” Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol., vol. 2, no. 12, pp. 910–919, Dec. 2017. [CrossRef]

- G. Taha, L. Ezra, and N. Abu-Freha, “Hepatitis C Elimination: Opportunities and Challenges in 2023,” Viruses, vol. 15, no. 7, Art. no. 7, Jul. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. J. Karoney and A. M. Siika, “Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection in Africa: a review,” Pan Afr. Med. J., vol. 14, no. 44, Art. no. 44, Jan. 2013. [CrossRef]

- L. J. de Oliveria Andrade, A. D’Oliveira, R. C. Melo, E. C. De Souza, C. A. Costa Silva, and R. Paraná, “Association Between Hepatitis C and Hepatocellular Carcinoma,” J. Glob. Infect. Dis., vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 33–37, 2009. [CrossRef]

- “Pathogenesis of hepatitis C virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma: evidence from recent studies - Maruyama - Journal of Public Health and Emergency.” Accessed: Jan. 16, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://jphe.amegroups.org/article/view/7483/html.

- “Hepatitis C Virus and Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Narrative Review - PMC.” Accessed: Jan. 16, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5863002/.

- “Systematic review of prevalence and risk factors of transfusion transmissible infections among blood donors, and blood safety improvements in Southern Africa | Request PDF,” ResearchGate, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Syed Hasan Mohamed El-Sagheer, Oswaldo Castro, and Samuel A Giday, “HCV in sickle cell disease.” Accessed: Jan. 16, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/9065255_HCV_in_sickle_cell_disease.

- “Trends of the Global Hepatitis C Disease Burden: Strategies to Achieve Elimination.” Accessed: Jan. 16, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.jpmph.org/journal/view.php?number=2154.

- R. Seu et al., “Challenges and Best Practices for Hepatitis C Care among People Who Inject Drugs in Resource Limited Settings: Focus Group Discussions with Healthcare Providers in Kenya,” Glob. Public Health, vol. 17, no. 12, p. 3627, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Mohd Suan, S. M. Said, P. Y. Lim, A. Z. F. Azman, and M. R. Abu Hassan, “Risk factors for hepatitis C infection among adult patients in Kedah state, Malaysia: A case–control study,” PLOS ONE, vol. 14, no. 10, p. e0224459, Oct. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Diana Nurutdinova, Arbi B. Abdallah, Susan Bradford, Catina C. O’Leary, and Linda B. Cottler, “Risk factors associated with Hepatitis C among female substance users enrolled in community-based HIV prevention studies - PMC.” Accessed: Jan. 17, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3095996/.

- WHO africa region, “Hepatitis Scorecard for the WHO Africa Region Implementing the hepatitis elimination strategy,” WHO | Regional Office for Africa. Accessed: Jan. 17, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.afro.who.int/publications/hepatitis-scorecard-who-africa-region-implementing-hepatitis-elimination-strategy.

- WHO africa, “New WHO scorecard shows poor progress of the viral hepatitis response in the African region,” WHO | Regional Office for Africa. Accessed: Jan. 17, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.afro.who.int/news/new-who-scorecard-shows-poor-progress-viral-hepatitis-response-african-region.

- Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD USA, “Progress towards elimination goals for viral hepatitis - PMC.” Accessed: Jan. 17, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7376316/.

- S. Popping et al., “The global campaign to eliminate HBV and HCV infection: International Viral Hepatitis Elimination Meeting and core indicators for development towards the 2030 elimination goals,” J. Virus Erad., vol. 5, no. 1, p. 60, Jan. 2019. [CrossRef]

- WHO, “Access to treatment and care for all: the path to eliminate hepatitis C in Egypt.” Accessed: Jan. 17, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/access-to-treatment-and-care-for-all--the-path-to-eliminate-hepatitis-c-in-egypt.

- Ahmed Hassanin, “Egypt’s Ambitious Strategy to Eliminate Hepatitis C Virus: A Case Study - PMC.” Accessed: Jan. 17, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8087425/.

- Ammal M. Metwally, ..., “Accelerating Hepatitis C virus elimination in Egypt by 2030: A national survey of communication for behavioral development as a modelling study - PMC.” Accessed: Jan. 17, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7901784/.

- K. H. Ismail and D. E. L.-P. Iii, “The need to re-invigorate initiatives against Hepatitis C in Egypt,” Popul. Med., vol. 5, no. February, pp. 1–2, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Mohamed Hassany, Wael Abdel-Razek, and Mohamed AbdAllah, “WHO awards Egypt with gold tier status on the path to eliminate hepatitis C - The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology.” Accessed: Jan. 17, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/langas/article/PIIS2468-1253(23)00364-3/fulltext. [CrossRef]

- Mario J. Azevedo, “The State of Health System(s) in Africa: Challenges and Opportunities - PMC.” Accessed: Jan. 17, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7123888/.

- S. E. Schröeder et al., “Innovative strategies for the elimination of viral hepatitis at a national level: A country case series,” Liver Int., vol. 39, no. 10, pp. 1818–1836, Oct. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Mohamed A. Daw, 1 , * Abdallah El-Bouzedi, 2 Mohamed O. Ahmed, 3 Aghnyia A. Dau, 4 and Mohamed M. Agnan 5, “Hepatitis C Virus in North Africa: An Emerging Threat - PMC.” Accessed: Jan. 17, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5004010/.

- WHO, “WHO releases first-ever global guidance for country validation of viral hepatitis B and C elimination.” Accessed: Jan. 17, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.who.int/news/item/25-06-2021-who-releases-first-ever-global-guidance-for-country-validation-of-viral-hepatitis-b-and-c-elimination.

- WHO, “Manual for the development and assessment of national viral hepatitis plans.” Accessed: Jan. 17, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241509350.

- Raad et al., “Challenge of hepatitis C in Egypt and hepatitis B in Mauritania,” World J. Hepatol., vol. 10, pp. 549–557, Sep. 2018. [CrossRef]

- “The Opportunity to Eliminate Hepatitis C through Alternative Financing Mechanisms.” Accessed: Jan. 17, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://endhep2030.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Policy-Brief_HCV.pdf.

- Felix Klein, “100 Million Seha: Egypt’s War against Hepatitis C,” PharmaBoardroom. Accessed: Jan. 17, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://pharmaboardroom.com/articles/100-million-seha-egypts-war-against-hepatitis-c/.

- WHO, “WHO commends Egypt for its progress on the path to eliminate hepatitis C.” Accessed: Jan. 17, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://assumption-prod.modolabs.net/parents__families/au_news/detail?feed=wr_crisis_response_who_news&id=7a0bad49-4b30-55eb-be91-6f9af408d33c&_kgoui_bookmark=f0f0ee60-484b-5273-9b0d-3c0e7b37a3fa.

- WHO, “Egypt becomes the first country to achieve WHO validation on the path to elimination of hepatitis C,” World Health Organization - Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean. Accessed: Jan. 17, 2024. [Online]. Available: http://www.emro.who.int/media/news/egypt-becomes-the-first-country-to-achieve-who-validation-on-the-path-to-elimination-of-hepatitis-c.html.

- James Jordano, Nina Curkovic, Sachin Aggarwal, and Kasey Hutcheson, “(PDF) Hepatitis C Treatment for Patients Without Insurance in a Student-Run Free Clinic: Analysis of Demographics, Cost, and Outcomes.” Accessed: Jan. 17, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/374954336_Hepatitis_C_Treatment_for_Patients_Without_Insurance_in_a_Student-Run_Free_Clinic_Analysis_of_Demographics_Cost_and_Outcomes.

- Margaret Hellard,1,2,3,4 Sophia E. Schroeder,1,2 Alisa Pedrana, “The Elimination of Hepatitis C as a Public Health Threat - PMC.” Accessed: Jan. 17, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7117951/.

- Elbahrawy, M. K. Ibrahim, A. Eliwa, M. Alboraie, A. Madian, and H. H. Aly, “Current situation of viral hepatitis in Egypt,” Microbiol. Immunol., vol. 65, no. 9, pp. 352–372, 2021. [CrossRef]

- T. Deress, Y. Million, T. Belachew, M. Jemal, and M. Girma, “Seroprevalence of Hepatitis C Viral Infection in Ethiopia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,” Sci. World J., vol. 2021, p. e8873389, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- “Prevalence of Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C in Migrants from Sub-Saharan Africa Before Onward Dispersal Toward Europe | Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health.” Accessed: Jan. 17, 2024. [Online]. Available:. [CrossRef]

- WHO, “Prevention and Control of Viral Hepatitis Infection: Framework for Global Action.” Accessed: Jan. 17, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/prevention-and-control-of-viral-hepatitis-infection-framework-for-global-action.

- “Viral hepatitis in resource-limited countries and access to antiviral therapies: current and future challenges | Future Virology.” Accessed: Jan. 17, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.futuremedicine.com/doi/10.2217/fvl.13.11. [CrossRef]

- “The Art and Science of Eliminating Hepatitis: Egypt’s Experience.” Accessed: Jan. 17, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_The_Art_and_Science_of_Eliminating_Hepatitis_Egypt's_Experience_2022.pdf.

- Petruzziello, S. Marigliano, G. Loquercio, A. Cozzolino, and C. Cacciapuoti, “Global epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection: An up-date of the distribution and circulation of hepatitis C virus genotypes,” World J. Gastroenterol., vol. 22, no. 34, pp. 7824–7840, Sep. 2016. [CrossRef]

- ministry of health malaysia, “National Institutes of Health - NIH Official Portal.” Accessed: Jan. 17, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://nih.gov.my/.

- Andrea L. Cox, Manal H. El-Sayed, Jia-Horng Kao, Jeffrey V. Lazarus, Maud Lemoine, Anna S. Lok & Fabien Zoulim, “Progress towards elimination goals for viral hepatitis | Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology.” Accessed: Jan. 17, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41575-020-0332-6.

- S. Ha and K. Timmerman, “Awareness and knowledge of hepatitis C among health care providers and the public: A scoping review,” Can. Commun. Dis. Rep., vol. 44, no. 7–8, pp. 157–165, Jul. 2018. [CrossRef]

- T. Li, R. Wang, Y. Zhao, S. Su, and H. Zeng, “Public awareness and influencing factors regarding hepatitis B and hepatitis C in Chongqing municipality and Chengdu City, China: a cross-sectional study with community residents,” BMJ Open, vol. 11, no. 8, p. e045630, Aug. 2021. [CrossRef]

- WHO, “Consolidated strategic information guidelines for viral hepatitis planning and tracking progress towards elimination: guidelines.” Accessed: Jan. 17, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789241515191.

- I. of M. (US) C. on the P. and C. of V. H. Infection, H. M. Colvin, and A. E. Mitchell, “Knowledge and Awareness About Chronic Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C,” in Hepatitis and Liver Cancer: A National Strategy for Prevention and Control of Hepatitis B and C, National Academies Press (US), 2010. Accessed: Jan. 17, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK220038/.

| Indicator | Baseline- 2020 | Targets-2025 | Targets-2030 | |

| Impact | Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) prevalence among children younger than 5 years old | 0.94% | 0.5% | 0.1% |

| Number of new hepatitis B infections per year | 1.5 million new cases 20 per 100 000 | 850 000 new cases 11 per 100 000 | 170 000 new cases 2 per 100 000 | |

| Number of new hepatitis C infections per year | 1.575 million new cases 20 per 100 000 | 1 million new cases 13 per 100 000 | 350 000 new cases 5 per 100 000 | |

| Number of new hepatitis C infections per year among people who inject drugs per year | 8 per 100 | 3 per 100 | 2 per 100 | |

| Number of people dying from hepatitis B per year | 820 000 deaths 10 per 100 000 | 530 000 deaths 7 per 100 000 | 310 000 deaths 4 per 100 000 | |

| Number of people dying from hepatitis C per year | 290 000 deaths 5 per 100 000 | 240 000 deaths 3 per 100 000 | 140 000 deaths 2 per 100 000 | |

| Coverage | Hepatitis B – percentage of people living with hepatitis B diagnosed / and treated | 30%/30% | 60%/50% | 90%/80% |

| Hepatitis C – percentage of people living with hepatitis C diagnosed / and cured | 30%/30% | 60%/50% | 90%/80% | |

| Percentage of newborns who have benefitted from a timely birth dose of hepatitis vaccine and from other interventions to prevent the vertical (mother-to-child) transmission of hepatitis B virus | 50% | 70% | 90% | |

| Hepatitis B vaccine coverage among children (third dose) | 90% | 90% | 90% | |

| Number of needles and syringes distributed per person who injects drugs | 200 | 200 | 300 | |

| Blood safety - proportion of blood units screened for bloodborne diseases | 95% | 100% | 100% | |

| Safe injections - proportion of safe health-care injections | 95% | 100% | 100% | |

| Milestones | Planning – number of countries with costed hepatitis elimination plans | TBD | 30 | 50 |

| Surveillance - number of countries reporting burden and cascade annually | 130 | 150 | 170 | |

| Hepatitis C virus drug access – percentage average reduction in prices (to equivalent generic prices by 2025) | 20% | 50% | 60% | |

| Hepatitis B virus drug access - percentage average reduction in average prices (alignment with HIV drug prices by 2025) | 20% | 50% | 60% | |

| Elimination of vertical (mother-to-child) transmission - number of countries validated for the elimination of vertical transmission of either HIV, hepatitis B, or syphilis | 15 | 50 | 100 | |

| Elimination - number of countries validated for elimination of hepatitis C and/or hepatitis B | 0 | 5 | 20 | |

| Integration - proportion of people living with HIV tested for/and cured from hepatitis C | TBD | 60%/50% | 90%/80% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).