1. Introduction

Shigella and

Salmonella spp. are among Enterobacteriaceae designated as global priority pathogens with consequent public health crisis [

1]. They are associated with an array of severe infections including food-poisoning, salmonellosis/shigellosis, bacteremia and recently infant sepsis [

2]. Chronic infections caused by

Salmonella and

Shigella spp. as opportunistic pathogens are of global concerns with increasing mortality rate [

1]. Some of these infections are difficult to threat as the bacteria develop resistance to antibiotics. Also, some of the infections have been attributed to formation of biofilms facilitating bacterial-surface attachment, thereby contributing to antimicrobial resistance (AMR) and the rising challenges of multidrug-resistance (MDR).

As antibiotics continue to lose effectiveness, AMR is increasingly becoming a global threat with an annual mortality case of almost 1 million and possible increase to 10 million by 2050 [

3]. This is enhanced by consistent bacterial evolution and progressive development of AMR mechanisms. AMR mechanisms could be intrinsic or acquired [

4]; however, some of these mechanisms are unclear and difficult to understand. This is compounded by the dearth of novel antibiotics in the development pipeline, necessitating the need to potentiate or repurpose existing antibiotics to enhance effectiveness. Small molecules like riboflavin have been indicated to have the ability to enhance antibiotics by inhibiting bacterial growth [

5].

Riboflavin is a water-soluble class B vitamin naturally present in some plant- and animal-based foods [

5]. Riboflavin, which is necessary for healthy skin development, contributes to the function of innate immune systems as microbiological barriers and a first line of protection against pathogens [

5]. It helps in the treatment of cancer and keratitis and aids in the production of antibodies in the host to fight infection [

6]. Its antimicrobial and antibiofilm activities against resistant

Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococcus faecalis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and

Streptococcus pneumoniae have been indicated [

5]. Also, it increases host resistance to

Plasmodium falciparum infections and suppresses the growth of

Candida albicans [

5,

6].

Enhancing macrophage phagocytic activity for rapid pathogen eradication is one of riboflavin's defense mechanisms [

6]. Its anti-inflammatory property increases toxins and induces Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacterial infection clearance [

7]. Additionally, riboflavin in combination with antibiotics such as ciprofloxacin and azithromycin limit

S. aureus infection [

8]. It achieves this by triggering macrophage phagocytosis and increase the formation of superoxide to suppress the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines including IFN-γ, IL-6, TNF-α [

5,

6,

7]. These cytokines are expressed in sepsis, especially in association with multidrug-resistant and biofilm producing bacteria. It also has the tendency to regulate the modifications of lipopolysaccharides, and consequently regulate the expression of associated AMR markers [

6].

In Ghana, our recent studies indicated the emergence of multi-drug resistant bacteria from hospital Intensive Care Units (ICUs). These bacterial strains were resistant to frontline conventional and last-resort antibiotics including carbapenems and colistin. Some of these strains, especially Shigella and Salmonella spp. were implicated in neonate sepsis with high levels of AMR. Leveraging alternative therapeutics and antibiotic potentiator like riboflavin might help to circumvent these rising AMR challenges. This study assessed riboflavin as a potential adjuvant to potentiate antibiotics against MDR Shigella and Salmonella spp. associated with cases of sepsis in Ghanaian hospital ICUs.

2. Results

Growth profile and antimicrobial resistance profile of bacterial strains

Salmonella (SAL901, SALAB) and

Shigella (SH701, SHAB) displayed more than 80 % resistance to the fluroquinolones and carbapenem relative to ATCC25922 with 30 – 50 % resistance (

Figure 1B). The highest level of resistance (90 - 95%) was observed in the presence of Levofloxacin, followed by Ofloxacin (90-92 %), Meropenem (80-85 %) and Ciprofloxacin (81-85 %). Growth rate increased significantly with increase in incubation time for all strains (

Figure 1B). Standard growth profile indicated that strains grew appreciably well at 37 ℃ with initial log phase of 2 h. Relative to ATCC25922, strains displayed exponential growth over 18 h indicating robust and actively dividing bacterial cells at 37 ℃.

2.1. MIC, FIC and Biofilm Profiles of Strains

Microbroth dilution and checkerboard assay was used to establish the MIC and FIC of the strains (

Table 1A). Individual MIC for

Salmonella SAL901 ranged between 160 – 320 µg/ml against tested fluroquinolones with Ofloxacin recording the highest MIC (320 µg). Combinations of the 4 antibiotics exhibited an MIC value range between 160 – 320 µg, however, there was a 2-fold reduction in the MIC for fluroquinolones when combined with meropenem. The fractional inhibitory concentration (FIC) index value (

Table 1B) for

Salmonella SAL901 for combinations with fluroquinolones and meropenem showed no interaction (

Table 1B); however, combination affected the inhibitory activity of the antibiotics on the strains. MIC for SALAB ranged between 160 – 320 µg, similar to SAL901 (

Table 1a). No interaction was observed for

Salmonella SALAB when treated with combinations of fluroquinolones and meropenem evident with FIC values between 1.5 – 2.0 (

Table 1b). For

Shigella SH701 and SHAB

, MIC values ranged between 320 – 640 µg /ml for individual antibiotic groups (

Table 1a), however, fluroquinolone combinations with meropenem resulted in a 2-fold reduction in MIC (160 – 320 µg /ml). The FIC values between 0.5 – 2.0 indicative of no interaction with slight increase in inhibitory activity when combined with antibiotics. For the biofilm profile,

Salmonella and

Shigella strains were strong biofilm formers (

Table 2). When challenged with standard concentrations of the antibiotics, the biofilm index indicated strong formers; however, when combined with riboflavin at 40 µg, all strains displayed a weak biofilm phenotype (

Table 1C).

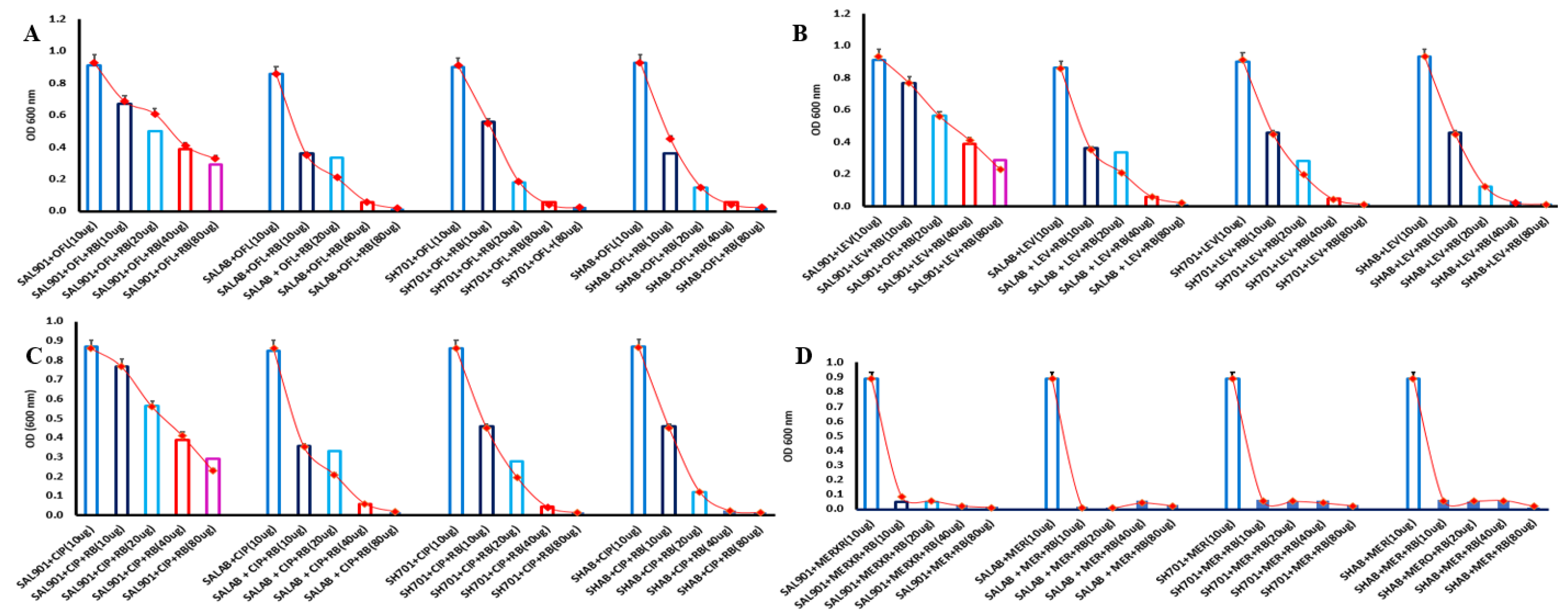

2.2. Riboflavin challenge assay

To determine the effect of riboflavin on bacterial strains treated with fluroquinolones and meropenem,

Salmonella and

Shigella strains were challenged with increasing concentration of riboflavin (2 -fold increase). Strains grew appreciably well with OD of 0.8 at 24 h with 10 µg of the test antibiotic (

Figure 2a); however, 10-40 µg of 2-fold riboflavin reduced bacterial growth. All strains displayed gradual reduction in bacterial survival with increasing riboflavin concentrations. At 40-80 µg riboflavin, there was significant bacterial growth inhibition with all the tested antibiotics. Two-fold Levofloxacin, addition of 2-fold dilutions of riboflavin resulted in a gradual reduction in bacterial growth relative to strains in the presence of only 10 µg of Levofloxacin (

Figure 2B). Significant reduction (60 %) was observed at 40 µg and 80 µg of riboflavin concentration with optical density below 0.2.

Salmonella SAL901 recorded a 38 % survival rate SALAB at 80 µg riboflavin concentration whereas SALAB, SH701and SHAB less than 10 % survival in the presence of 40 – 80 µg of riboflavin. Growth rate was also significantly reduced in Ciprofloxacin with gradual in bacterial concentration following addition of riboflavin (

Figure 2C). Survival rate was less than 40 % with SALAB, SH701and SHAB significantly inhibited in the presence of 40-80 µg riboflavin concentration. Meropenem - riboflavin challenge exhibited the most significant reduction in bacterial concentration (

Figure 2D). At 10 µg riboflavin, survival rate of

Salmonella and

Shigella strains were below 10 % relative to standard meropenem treatment (10 µg). Survival rate for the strains at the 4 riboflavin concentrations was below 10 % indicating significant bacterial inhibition in meropenem treated strains challenged with riboflavin. All strains including SAL901 exhibited this reduced survival rate in meropenem.

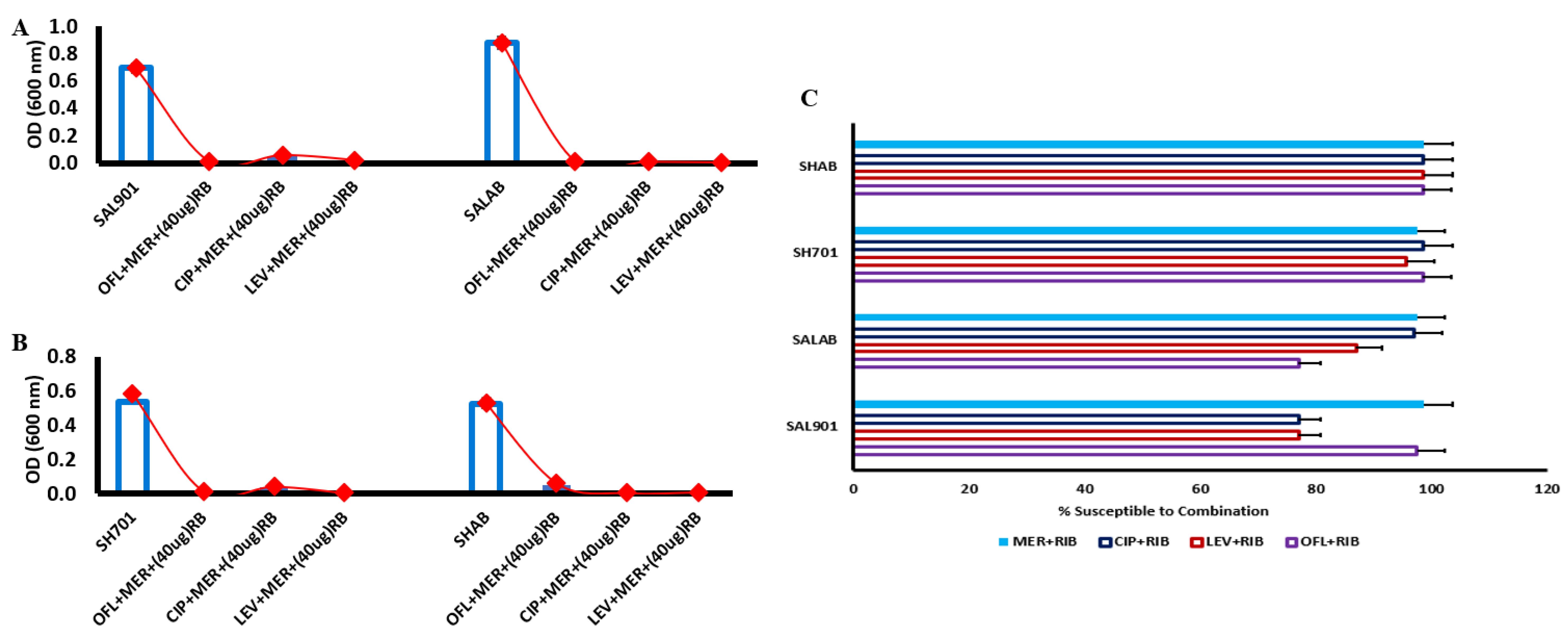

2.3. Meropenem - Riboflavin challenge

Due to reduction in MIC of fluroquinolones – meropenem combination, antibiotic treated strains were challenged with riboflavin at 40 µg. In the presence of 40 µg riboflavin (

Figure 3A), there was significant reduction in bacterial concentration for

Salmonella SAL901 and SALAB. Survival rate was less than 10 % for the strains challenged with the 3 fluoroquinolones and meropenem. For

Shigella SH701 and SHAB, 95 % inhibition of bacterial strains was observed relative to untreated

Shigella (

Figure 3B). The combination of the individual fluroquinolones with meropenem in the presence of riboflavin resulted in significant reduction in bacterial concentration. FIC index of 0.075 was observed for meropenem with riboflavin indicating a highly synergistic activity of meropenem and riboflavin (

Figure 3C). The decreased inhibitory concentration corelates with the FIC index observed.

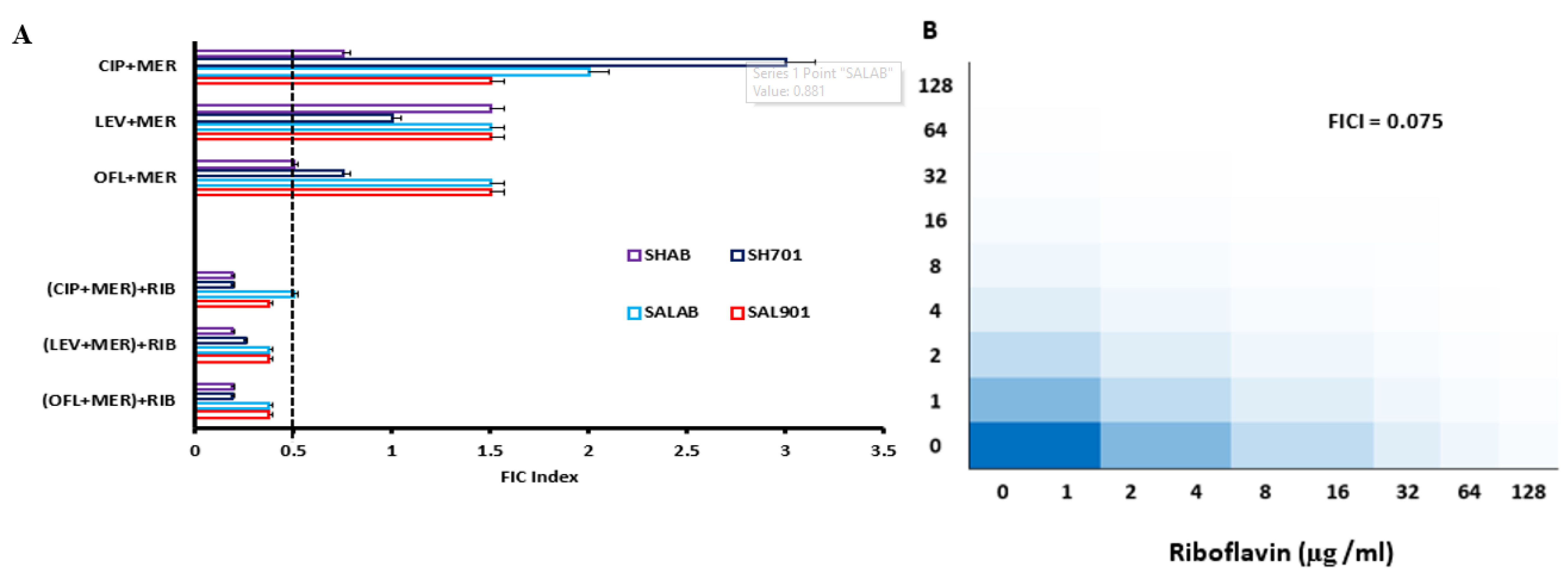

2.4. Percentage susceptibility of individual antibiotics to riboflavin

The FIC index value of individual fluroquinolones challenged with meropenem was above 0.5 with ofloxacin displaying the lowest FIC index of 0.5 and 0.8 for

Shigella strains, indicative of minimal synergistic activity. When treated strains (fluroquinolone-meropenem) were challenged with riboflavin, the FIC index values were below 0.5 (

Figure 4A), indicative of synergistic activity and evident with the reduction in bacterial concentration following riboflavin challenge (

Figure 3A & 3B). Percentage susceptibility of the strains to riboflavin combination with the antibiotics was greater than 70 % (

Figure 4B). The combination of meropenem and riboflavin displayed the highest level of susceptibility (95%) indicative of increased bacterial inhibition in all the strains. The level of susceptibility of the strains to fluroquinolone-riboflavin challenge particularly for ciprofloxacin was high (> 90 %) in

Shigella strains with

Salmonella strains recording levels above 70 % (

Figure 4B).

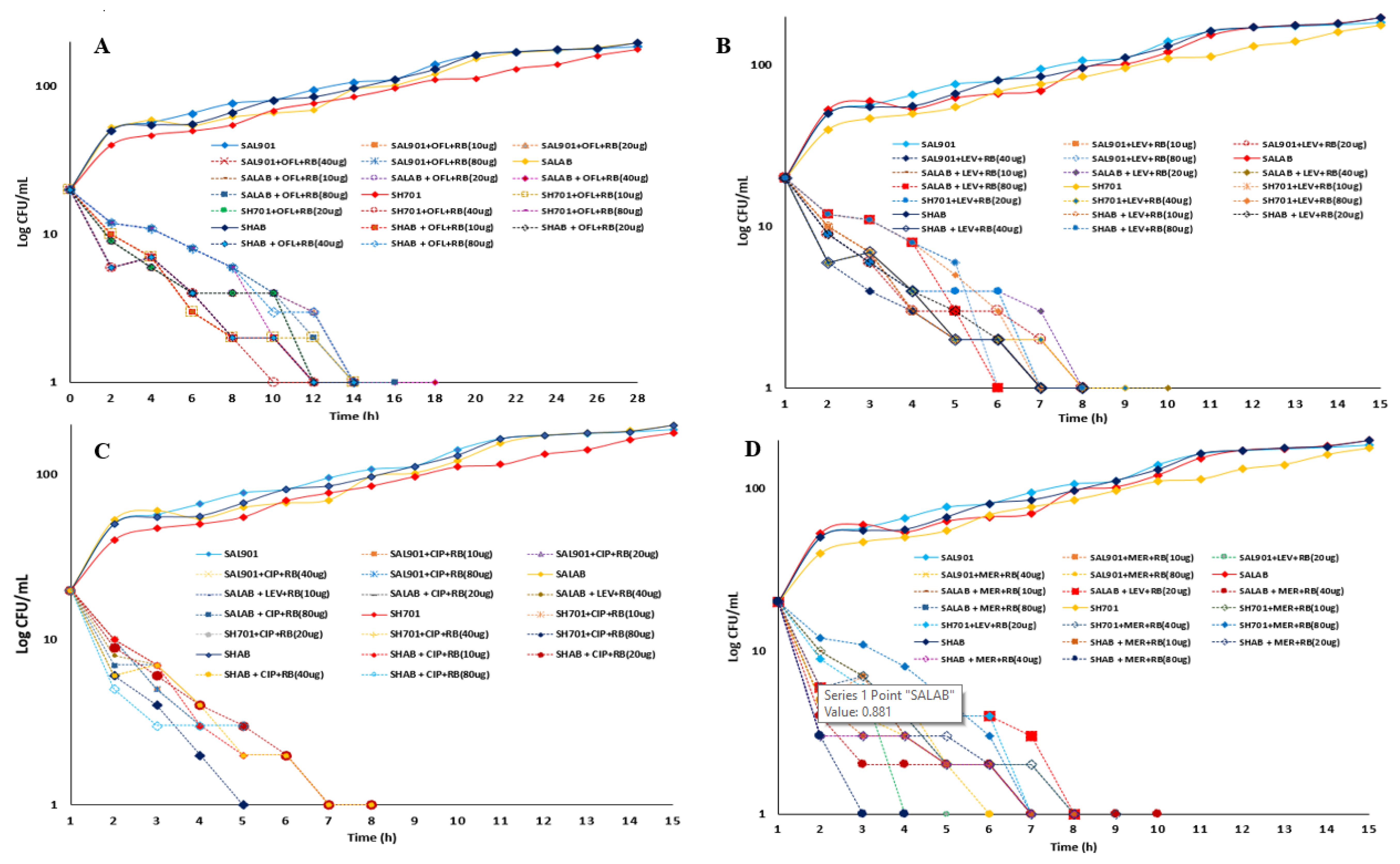

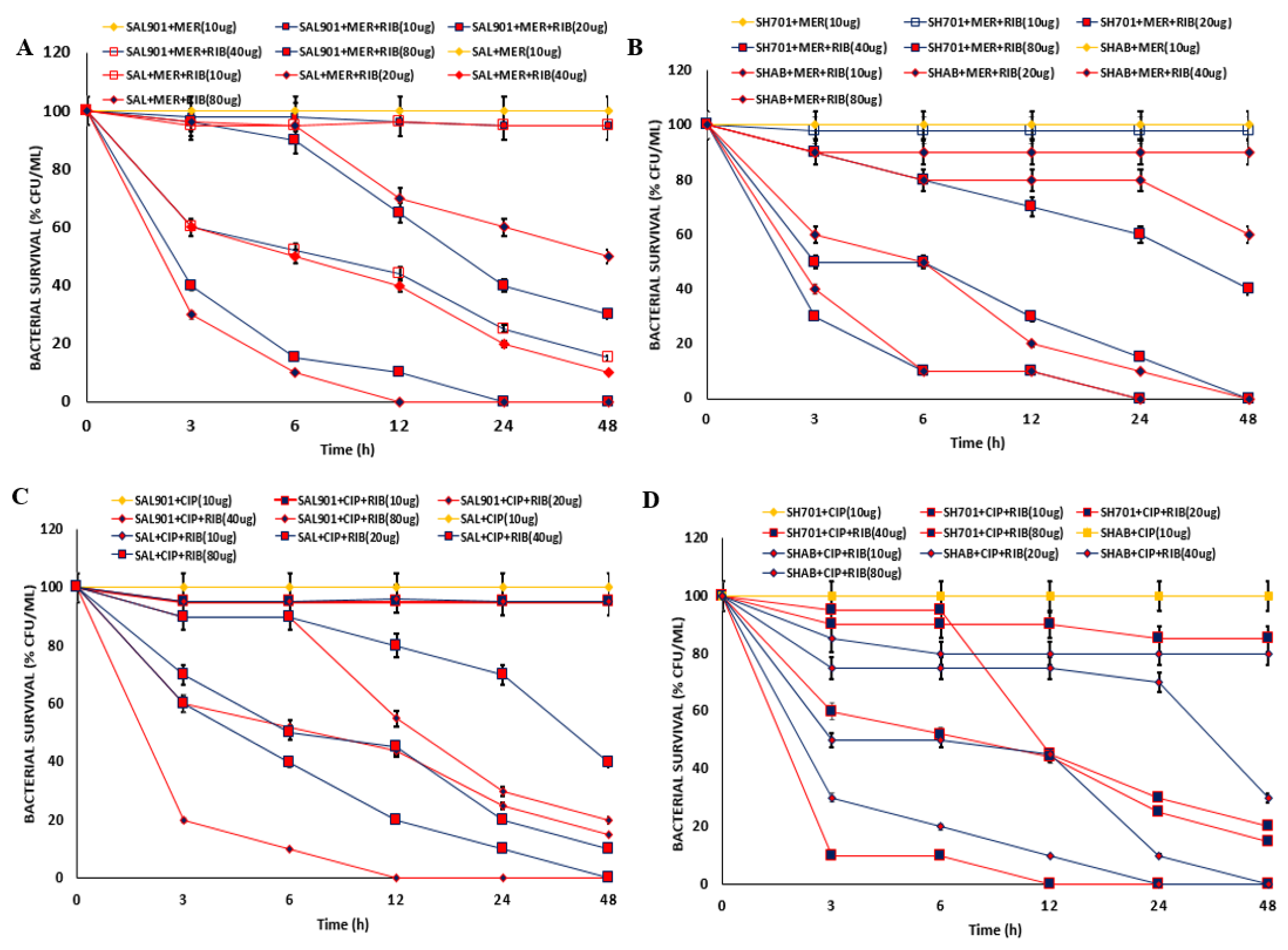

2.5. Time kill curve for riboflavin challenge

A time kill curve assay was performed for strains treated with antibiotics and challenged with 2-fold increasing concentration of riboflavin (10-80 µg /ml) and plotted against log CFU/ml (

Figure 5). Starting with 30 log CFU/ml concentration of bacterial cells 100 log CFU/ml was observed 16 h after incubation with a gradual increase in log CFU/ml over 24 h (

Figure 5A). Addition of riboflavin to ofloxacin treated strains resulted in significant reduction (> 90 %) in log CFU/ml (

Figure 5A). 15 – 20% reduction was observed within the first 2 h of incubation, with gradual decrease in cell concentration to 1 log CFU/ml between 10 to 18 h (

Figure 5B). For Levofloxacin treated strains (

Figure 5C), addition of increasing concentration of riboflavin resulted in 10 - 25 % reduction in log CFU/ml after 2 h challenge. A reduction from 30 log CFU/ml concentration to 1 log CFU/ml was observed between 6 to 10 h incubation at 10 - 80 µg /ml riboflavin treatment. Treatment with ciprofloxacin and riboflavin resulted in 3 – 5-fold reduction in log CFU/ml at 2 h. With increased incubation time ≥ 95 % reduction was observed between 5 to 8 h incubation). Meropenem treated strains recorded a significant reduction (≥ 50) in some strains within 2 h riboflavin challenge. 95 % reduction in viable strains was observed 3 h for

Shigella strains at 80 µg riboflavin addition and Salmonella strains displaying 95 % reduction after 5 h challenge (

Figure 5D).

2.6. Infection assay

Bacterial viability after intracellular infection in RAW cells was examined for meropenem and ciprofloxacin treated strains. Meropenem (10 µg) treated strains of

Salmonella sp. (SAL901 and SAL) exhibited 90 - 100% recovery on plate following macrophage lysis (

Figure 6A). For SAL901 and SAL at 10 µg riboflavin treatment, 90 % bacterial load (% CFU/ml) was recovered after 6 hours. There was a 40 – 70 % reduction in bacterial concentration in macrophages post 3 hours infection for meropenem strains challenged with 20 - 80 µg riboflavin. When meropenem treated strains were challenged with 80 µg riboflavin, 90 % reduction in bacterial concentration was recorded after 6 hours with complete reduction after 24 hours. For

Shigella sp. (SH701 and SHAB) (

Figure 6B), 100 % recovery was observed for 10 µg meropenem treated strains at 3, 6, 12, 24 and 48 hours post infection assay. Addition of 10 µg riboflavin resulted in 10 % reduction in viable bacteria at the different time points. At 20 µg riboflavin treatment, 60 - 80 % of bacterial concentration was recovered at 24 h post infection with a 2-fold reduction at 48 hours. Treatment with 40 – 80 µg of riboflavin resulted in significant reduction (60 %) at 3 hours post infection with 90% reduction at 6 hours; total inhibition was observed at 24 to 48 hours incubation. For 10 µg ciprofloxacin treatment, 100 % bacterial load was recovered at the 5 time points for both

Salmonella sp. and

Shigella strains (

Figure 6C & D). Treatment with 10 µg riboflavin resulted in 5 % reduction in bacterial load for

Salmonella sp., and 10 - 30 % reduction in

Salmonella strains after 3 hours post infection. With increasing concentration of riboflavin (2-fold increase), there was significant reduction in bacterial load (

Figure 6C), where 80 µg resulted in 80-100 % reduction in bacterial concentration with increasing incubation. For

Shigella treated strains addition of increasing concentration of riboflavin resulted in significant reduction in bacterial load with 85 % reduction post 12 hours infection and 100 % reduction at 24 hours incubation (

Figure 6D).

3. Discussion

Emergence of multidrug-resistant

Salmonella and

Shigella coupled with reduction in effective antibiotics for treatment necessitates development of new antibiotics or resensitization of existing antibiotics. Riboflavin or vitamin B

2, a precursor for production of cofactors FMN and FAD is increasingly being reported as a promising antimicrobial agent in modulating host immune responses, enhancing antimicrobial properties of antibiotics and exhibiting antimicrobial effects on diverse microorganisms such as parasites, fungi and viruses [

5]. In this study, we explored Riboflavin as an adjuvant in resensitizing fluroquinolones and carbapenems against biofilm forming and multidrug-resistant

Salmonella and

Shigella strains from the Ghanaian hospital environment.

Salmonella and

Shigella species are characterized as successful pathogens as they readily adapt to varying environmental and clinical conditions. Within the natural environment and during intracellular host interactions, temperature plays a major role in adaptation, growth kinetics and survival in bacteria. At 37 ℃ strains exhibited substantial growth with short lag phases (1-2 h) relative to control strain.

Salmonella and

Shigella species have been reported to have optimum growth temperature at 37 ℃ with short lag phases that allows adaptation and expression of virulence for colonization and infection [

14].

Strains also exhibited high level of resistance (> 80 %) to fluroquinolones and carbapenems. minimum inhibitory concentration established for fluroquinolones ranged between 320-640 µg/ml with 160 – 640 µg/ml meropenem. AMR to antibiotics commonly used in the treatment of diarrhea related infections from

Salmonella and

Shigella species such as ampicillin, tetracycline and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole have been indicated [

15]. Reliance on alternative treatment options such as fluoroquinolones and carbapenems has also resulted in the development of resistant strains [

15,

16].

Due to the incidence of resistance from monotherapy, combination of antibiotics is frequently employed to combat infections. Combination of fluroquinolones and meropenem showed a moderate (2-fold) reduction in MIC of

Salmonella and

Shigella strains; however, the FIC values indicated no synergistic interaction between fluoroquinolones and meropenem. Synergistic interaction of β-lactams and aminoglycosides have been explored with significant efficacy on bacterial strains. Combination of fluroquinolones with meropenem has been shown to reduce bacterial burden in

Pseudomonas aeruginosa [

17]. Similarly, combination of levofloxacin and ciprofloxacin in adult patients was effective against nosocomial pneumonia [

18]. This study showed a 2-fold reduction in MIC following combination of fluroquinolones with meropenem; however, the MIC was significantly higher than the recommended standard for individual antibiotics or combined therapy.

Formation of biofilm has been recognized as a defense mechanism bacterium employ to circumvent environmental stresses such as antibiotics and host immune defenses. Bacteria biofilms have been implicated in bacteria pathogenesis as it allows for colonization and establishment of infection [

4]. Eradication of biofilms are particularly difficult and require diverse intervention strategies.

Salmonella and

Shigella species have demonstrated ability to establish biofilms under different environmental conditions and surfaces [

19]. In this study, all strains formed biofilms and exhibited a strong biofilm phenotype both in the presence and absence of antibiotic. However, addition of 40 µg/ml riboflavin in combination with antibiotics reduced biofilm from strong to weak phenotype. Antibiofilm potential of riboflavin has been reported in

S. aureus, E. coli [

20],

C. albicans and

Enterococcus where reduction in biofilm was observed following UV irradiation of riboflavin [

5].

To determine if riboflavin could also reduce the level of resistance following MIC determination, strains were challenged with 2-fold increasing concentration of riboflavin. There was a 2-fold reduction in bacterial survival at 10 µg/ml riboflavin and 95% bacterial reduction at 80 µg/ml for all the antibiotics tested. Combination of fluroquinolones with meropenem in the presence of 40 ug/ml of riboflavin resulted in a significant reduction in bacterial survival. There was significant synergistic interaction between meropenem and riboflavin resulting in greater than 95% reduction in

Salmonella and

Shigella population relative to their untreated control. The FIC index of meropenem against riboflavin also showed a high level of synergy with significant reduction in bacterial population. Riboflavin alone has been reported to display bactericidal activity in the presence or absence of ultraviolet light radiation [

21,

22]; however, significant bactericidal activity was observed when bacterial strains were pre-treated with antibiotics and challenged with riboflavin [

22]. Riboflavin best exhibits it antimicrobial activity when combined with other antibiotics such as meropenem and or fluoroquinolones to induce synergistic bactericidal activity.

Time kill curve was used to observe the bactericidal activity of antibiotic-riboflavin combinations at different time points and concentrations. The combination of riboflavin and antibiotics, particularly meropenem displayed rapid bactericidal activity within the first few hours (3 – 6 h). All the concentrations of riboflavin exhibit bactericidal activity with antibiotics; however, 40 µg/ml - 80 µg/ml displayed higher activity relative to 10 µg/ml – 20 µg/ml. Based on the observations, the antimicrobial effect of riboflavin in combination with antibiotics occurs within the first few hours of incubation, and concentrations of riboflavin above 20 µg/ml provides an enhanced synergistic bactericidal activity.

To explore riboflavin’s role in host immune responses, macrophage infection assays were conducted. Riboflavin has been indicated to induce non-specific host defense systems by enhancing the activity of macrophages and neutrophils [

8]. There was significant reduction in bacterial concentration for both

Salmonella and

Shigella strains within the macrophage cell lines. This reduction was dose dependent with riboflavin in the presence of the antibiotics tested. Complete clearance of bacterial strains from macrophages was between 12 – 24 h. Macrophages function to phagocytose, digest and destroy invading microorganisms such as bacteria. The phagolysosome created during engulfment of bacteria is a nutrient-limiting environment with reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (NO) produced. ROS and NO produced by macrophages function to disrupt bacterial pathogens [

8]. Production of ROS requires the NADPH oxidase enzyme complex which depends on FAD for proper function. Riboflavin acts as a precursor for the production of FAD which enhances respiratory burst of macrophages during pathogen clearance. In a previous study, macrophage viability and activity were inhibited when riboflavin was deficient [

23]. Also, the introduction of riboflavin induced mice resistance to bacterial infections by increasing production of neutrophils, macrophages and enhancing phagocytic activity of macrophages [

5,

8]. This study indicated that riboflavin could modulate innate immune response for pathogen clearance.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Strain Information

Four archived Salmonella enterica (SAL901, SALAB) and Shigella flexneri (SH701, SHAB) strains from AbiMosi™ Bacterial Culture Library at West African Centre for Cell Biology of Infectious Pathogens (WACCBIP), University of Ghana was used in this study. The strains were isolated from neonatal sepsis and are MDR to fluoroquinolones, carbapenems, β-lactams, penicillins, macrolides, chloramphenicol, sulfonamides, and cephalosporins. All the strains were revived on MacConkey Agar media (37oC for 24 h) (Oxoid, England, CM0003) prior to the experiments.

4.2. Antimicrobial Resistance Profiling Assays

Kirby-Bauer disc diffusion was used to determined AMR profiles of the strains to ciprofloxacin (10 µg), levofloxacin (10 µg), ofloxacin (10 µg) and meropenem (10 µg) (Mast Diagnostics, Mast Group Ltd., Merseyside, U.K) as previously described (Abiola Isawumi et al., 2018). Sterile Mueller Hinton agar plates (Oxoid, Basingtoke, UK) were inoculated with standardized overnight culture (0.5 at 600 nm) of the strains, the antibiotic discs applied aseptically and incubated (37oC for 24 h). The zone of inhibition determined using CLSI guidelines in two independent experiments with three replicates. The ratio of antibiotics resisted by test strains to the total number of antibiotics tested expressed in percentages was used to determine percentage of resistance. To determine the minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC), 100 µl of the standardized culture was added to 100 µl of the tested antibiotics in a 96-well plate and incubated (37oC for 24 h, 120 rpm). The OD (600 nm) was measured and ratio of the OD of the test strain to the control expressed in percentages was used to determine the MIC. The percentage OD < 10 was the assigned MIC of the strains at the indicated concentrations. The fractional resistance was achieved in a colony-spotting assay by comparing the percentage of colonies from antibiotic-resistant wells to the control without antibiotics as previously described (Abiola Isawumi et al., 2023).

4.3. Riboflavin Challenge and Chequerboard Assays

A cocktail of riboflavin and test antibiotic was prepared to reduce AMR levels of the strains. Briefly, 50 µl of the standardized concentrations of the antibiotics (10 µg/ml - meropenem, ofloxacin, ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin) was combined with 50 µl of riboflavin (10, 20, 40, 80 µg/ml) in 96-well plates. 100 µl of the standardized culture of the strains was added to the cocktail, incubated (37

oC for 24 h) and optical density determined (600 nm). To determine the

in vitro synergistic activity of riboflavin and the tested antibiotics (meropenem, ofloxacin, ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin) against MDR

S. flexneri and

S. enterica, a checkerboard experiment was conducted. Firstly, the effects of the test antibiotics at their standard concentrations (10 µg/ml) in combination without the riboflavin was determined. Briefly, the antibiotics were prepared in two-fold increasing concentrations of (10, 20, 40, 80, 160, 320, 640, 1240 µg/ml). A 50 ul of MHB was transferred into the each well of microtiter plates and first antibiotic was serially diluted along the ordinate (96-well plate y-coordinate), while the second along the abscissa (96-well plate x-axis) as previously described [

9]. The microtiter wells were inoculated with 50-100 ul of the standardized inoculum (0.5 at 600 nm) of the strains and incubated (37

oC for 24 h, 120 rpm) under aerobic conditions. The MICs were determined as previously described, while fractional inhibitory concentrations (FIC) index was calculated as FICI = (MIC antibiotic X in combination/MIC antibiotic X) + (MIC antibiotic Y in combination/MIC antibiotic Y) [

9]. Synergistic activity was defined as FIC ≤ 0.5, no interaction with 0.5<FICI ≤ 4 and FICI > 4 as antagonistic. The same experimental procedure was repeated to determine the effects of riboflavin in combinations with the tested antibiotics, however with varying and different concentrations per assay. For riboflavin with meropenem, double concentrations of both were used in increasing orders (1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, 128 ug/ml) and FICI determined as previously indicated. Since meropenem is a last-resort antibiotic, the effects of riboflavin on combinations of meropenem and other test antibiotics (ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, ofloxacin) was determined in a three-dimensional chequerboard assay as previously described [

10]. Similar to the previously described procedure, 40 µg/ml of riboflavin was added to two-fold increasing concentrations of ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, ofloxacin (10, 20, 40, 80, 160, 320, 640, 1240 µg/ml) in the 96-well plates with 100 µl of standardized inoculum and incubated at already stated conditions and interpreted as previously described. All the assays were conducted in two independent experiments with three replicates.

4.4. Riboflavin-Antibiotic Biofilm and Time-Kill Curve Assays

Crystal violet biofilm assay was conducted as previously described [

11]. Bacterial cultures were prepared in 96-well microtiter plates containing minimal media supplemented with glucose. The plates were incubated for 48-72 h at 37

oC; the planktonic cells (non-adherent cells) were removed with 0.9% normal saline (2-3 times) and washed gently with sterile ultrapure water. 200 µl of 0.1% crystal violet was added to each well and incubated at room temperature for 30 min. The crystal violet (solubilized with 96% ethanol or glacial acetic acid) was transferred into another fresh microtiter plate and OD was measured (590 nm) and the experiment was conducted in triplicate. Biofilm biomass was calculated by first establishing OD cut-off value (ODc) as previously described [

12]. ODc is Average OD of negative control + 3 x standard deviation (SD) of negative control. OD of the tested strain is average OD of strain reduced by ODc value. The results were interpreted as non (OD ≤ ODc) or weak (ODc < OD ≤ 2 x ODc) or moderate (2 x ODc < OD ≤ 4 x ODc) or strong (4 x ODc < OD) biofilm formation. To determine the effects of riboflavin on biofilm formation of the strains, established MIC of the strains were used as baseline for biofilm inhibition or eradication assay. 100 µl of the standardized culture (OD – 0.5) was transferred into 96-well plates seeded with various concentrations of antibiotics: 160-320 ug/ml of the antibiotics for the

Salmonella strains, 320-640 ug/ml for the

Shigella strains, incubated (37 ℃, 48-72 h) and biofilm formation was determined as previously indicated and products quantified with resazurin dyes. Time-kill activity of the riboflavin-antibiotic cocktail was performed in triplicate according to the microbroth dilution protocol guided by CLSI criteria and as previously described [

13]. As already indicated, 500 ul of (10, 20, 40, 80 µg/ml) riboflavin-antibiotic (10 µg/ml of each antibiotic) cocktail prepared in 1:1. 500 µl of the strains at the log phase was adjusted to 10

6 CFU/mL and 1 ml of the inoculum with 1 ml of the prepared cocktail in test-tubes were incubated at 37

oC for 24 h with shaking (125 rpm). To determine the time-kill activity in log

10 CFU/mL, 30-50 µL was withdrawn at 1 h intervals for 24 h, spread on LB plates and incubated as earlier stated.

4.5. Infection and Bacterial Survival Index Assays

The survival index of the strains was determined using THP-1 cell line cultured in DMEM supplemented with penicillin and streptomycin (50-100 µg/ml) and 10% FBS as previously described (). Briefly, the macrophage cell was initially seeded at a 1 x 106 cells/ml for 24-48 h for adherence. The bacterial cultures were standardized to 1 x 106 – 1 x 108 cells/ml and cocultured with the cell line at standard concentrations of ciprofloxacin (10 µg/ml), meropenem (10 µg/ml); however, at increasing 2-fold concentrations of riboflavin (10, 20, 40, 80 µg/ml) and incubated (24-48 h, 37°C in 5% CO2) with controls (untreated cell line). Viability was determined with 10 % (v/v) Resazurin and incubated as previously indicated. Absorbance was determined at 570 nm and bacterial survival was estimated and expressed in percentage relative to the control.

5. Conclusions

The challenge resistance poses necessitate the development of new therapeutic approaches in combating infections. Approaches which include antibiotic combination with adjuvant potentiation to enhance antimicrobial activity and induce host immune response provide insights to AMR reduction. In this study, riboflavin displayed a potentiating activity by synergistically enhancing the antimicrobial activity of fluroquinolones and meropenem leading to reduction in resistant Salmonella and Shigella strains. Also, riboflavin enhanced the immunomodulatory properties of host cell lines in combination with meropenem to clear intracellular resistant bacterial pathogens. This in vitro resensitization of antibiotics could serve as therapeutic targets in mitigating resistance in selected bacterial pathogens.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org. Sheet Table 1: Time-kill data; Sheet 2 Table 2: Challenge Assays; Sheet 3 Table 3: Growth Assay; Sheet 4 Table 4: Biofilms Data

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.I..; methodology, A.I., M.K.A..; validation, A.I..; formal analysis, A.I., M.K.A., E.A.A.; investigation, A.I., M.K.A., E.A.A., B.G., M.M., G.K.A., M.O.O.; resources, A.I..; data curation, A.I., M.K.A., E.A.A., M.M., B.G., M.O.O.; writing—original draft preparation, A.I., M.K.A..; writing—review and editing, A.I., M.K.A., E.A.A.; visualization, A.I.; supervision, A.I.; project administration, A.I.; funding acquisition, A.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by World Bank ACE Seed Grant (to Abiola Isawumi), ACE02-WACCBIP: Awandare

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate AMR Research Group led by Dr. Abiola Isawumi at West African Centre for Cell Biology of Infectious Pathogens, Department of Biochemistry, Cell and Molecular Biology, University of Ghana.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Almansour, A.M.; Alhadlaq, M.A.; Alzahrani, K.O.; Mukhtar, L.E.; Alharbi, A.L.; Alajel, S.M. The Silent Threat: Antimicrobial-Resistant Pathogens in Food-Producing Animals and Their Impact on Public Health. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2127. [CrossRef]

- Ararsa T, Wolde D, Alemayehu H, Bizuwork K, Eguale T. Prevalence and Antimicrobial Susceptibility Profile of Salmonella and Shigella among Diarrheic Patients Attending Selected Health Facilities in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2023;2023:6104416. Published 2023 Oct 14. [CrossRef]

- Tang, K. W. K., Millar, B. C., & Moore, J. E. (2023). Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR). British journal of biomedical science, 80, 11387. [CrossRef]

- Abban MK, Ayerakwa EA, Mosi L, Isawumi A. The burden of hospital acquired infections and antimicrobial resistance. Heliyon. 2023;9(10):e20561. Published 2023 Oct 2. [CrossRef]

- Farah, N., Chin, V. K., Chong, P. P., Lim, W. F., Lim, C. W., Basir, R., Chang, S. K., & Lee, T. Y. (2022). Riboflavin as a promising antimicrobial agent? A multi-perspective review. Current research in microbial sciences, 3, 100111. [CrossRef]

- Lei, J., Xin, C., Xiao, W., Chen, W., & Song, Z. (2021). The promise of endogenous and exogenous riboflavin in anti-infection. Virulence, 12(1), 2314–2326. [CrossRef]

- Suwannasom N, Kao I, Pruß A, Georgieva R, Bäumler H. Riboflavin: The Health Benefits of a Forgotten Natural Vitamin. Int J Mol Sci. 2020 Jan 31;21(3):950. [CrossRef]

- Dey S, Bishayi B. Riboflavin along with antibiotics balances reactive oxygen species and inflammatory cytokines and controls Staphylococcus aureus infection by boosting murine macrophage function and regulates inflammation. J Inflamm (Lond). 2016 Nov 28;13:36. [CrossRef]

- Black, C.; Al Mahmud, H.; Howle, V.; Wilson, S.; Smith, A.C.; Wakeman, C.A. Development of a Polymicrobial Checkerboard Assay as a Tool for Determining Combinatorial Antibiotic Effectiveness in Polymicrobial Communities. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1207. [CrossRef]

- Stein C, Makarewicz O, Bohnert JA, Pfeifer Y, Kesselmeier M, Hagel S, Pletz MW. Three Dimensional Checkerboard Synergy Analysis of Colistin, Meropenem, Tigecycline against Multidrug-Resistant Clinical Klebsiella pneumonia Isolates. PLoS One. 2015 Jun 11;10(6):e0126479. [CrossRef]

- O'Toole GA. Microtiter dish biofilm formation assay. J Vis Exp. 2011 Jan 30;(47):2437. [CrossRef]

- Stepanovic S, Vukovic D, Dakic I, Savic B, Svabic-Vlahovic M. A modified microtiter-plate test for quantification of staphylococcal biofilm formation. J Microbiol Methods. 2000 Apr;40(2):175-9. [CrossRef]

- Isawumi A, Abban MK, Ayerakwa EA, Mosi L. Calcium Potentiated Carbapenem Effectiveness Against Resistant Enterobacter Species. Microbiology Insights. 2022;15. [CrossRef]

- Andino A, Hanning I. Salmonella enterica: survival, colonization, and virulence differences among serovars. ScientificWorldJournal. 2015;2015:520179. [CrossRef]

- Ranjbar R, Farahani A. Shigella: Antibiotic-Resistance Mechanisms And New Horizons For Treatment. Infect Drug Resist. 2019 Oct 7;12:3137-3167. [CrossRef]

- Salleh MZ, Nik Zuraina NMN, Hajissa K, Ilias MI, Banga Singh KK, Deris ZZ. Prevalence of Multidrug-Resistant and Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamase-Producing Shigella Species in Asia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Antibiotics (Basel). 2022 Nov 18;11(11):1653. [CrossRef]

- Louie A, Grasso C, Bahniuk N, Van Scoy B, Brown DL, Kulawy R, Drusano GL. The combination of meropenem and levofloxacin is synergistic with respect to both Pseudomonas aeruginosa kill rate and resistance suppression. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010 Jun;54(6):2646-54. [CrossRef]

- West M, Boulanger BR, Fogarty C, Tennenberg A, Wiesinger B, Oross M, Wu SC, Fowler C, Morgan N, Kahn JB. Levofloxacin compared with imipenem/cilastatin followed by ciprofloxacin in adult patients with nosocomial pneumonia: a multicenter, prospective, randomized, open-label study. Clin Ther. 2003 Feb;25(2):485-506. [CrossRef]

- Ellafi, A., Abdallah, F.B., Lagha, R. et al. Biofilm production, adherence and morphological alterations of Shigella spp. under salt conditions. Ann Microbiol 61, 741–747 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, Satarupa, et al. "Photodynamic antimicrobial chemotherapy (PACT) using riboflavin inhibits the mono and dual species biofilm produced by antibiotic resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli." Photodiagnosis and Photodynamic Therapy 32 (2020): 102002.. [CrossRef]

- Mirshafiee H, Sharifi Z, Hosseini SM, Yari F, Nikbakht H, Latifi H. The Effects of Ultraviolet Light and Riboflavin on Inactivation of Viruses and the Quality of Platelet Concentrates at Laboratory Scale. Avicenna J Med Biotechnol. 2015 Apr-Jun;7(2):57-63. PMID: 26140182; PMCID: PMC4483315..

- Aarthi Ahgilan, Vikineswary Sabaratnam & Vengadesh Periasamy (2016) Antimicrobial Properties of Vitamin B2, International Journal of Food Properties, 19:5, 1173-1181. [CrossRef]

- Mazur-Bialy AI, Buchala B, Plytycz B. Riboflavin deprivation inhibits macrophage viability and activity - a study on the RAW 264.7 cell line. Br J Nutr. 2013 Aug 28;110(3):509-14. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).