1. Introduction

The remarkable energy efficiency of the brain in tackling logical and numerical challenges inspired researchers to explore the feasibility of developing novel hardware devices capable of emulating neurons to solve complex practical problems. However, current artificial neurons (ANs) predominantly rely on conventional MOSFET electronics with von Neumann architecture, which imposes limitations due to their high energy consumption and speed constraints. A paradigm shift in hardware design is imperative to enhance energy efficiency and downsize device dimensions.

In recent years, a number of nanoscale devices and materials have been proposed for employment in neuromorphic data processing, including materials featuring resistive switches, spintronics, and photonic structures (see [

1] for a recent review). While Joule heating, speed and scalability are among the main challenges for neuromorphic elements based on resistive switching [

2], spin-based data processing could offer scalability, sub-nanosecond speeds and low-dissipation if the operation is mediated by spin waves. Systems utilizing spintronics nanostructures for non-conventional computing currently include magnetic tunnel junctions for neuromorphic [

3] or stochastic [

4] computing (see [

5] for a recent review), spin wave logics [

6,

7] and lithographically patterned nanowires [

8]. In magnetic nanostructures, information can be encoded and processed by using magnetic signals detected through electromagnetic induction or tunneling magnetoresistance and manipulated using spin torque [

8].

A great advantage of using ferromagnetic nanowires is that they can be integrated with other nanoscale components and materials to produce complex neuromorphic systems. For example, they could be combined with memristors (particularly with those based on magnetic tunnel junctions [

9]) to create hybrid neuromorphic architectures leading to novel computing paradigms. The manipulation of magnetic textures in nanoscale ferromagnetic devices is one of the most promising routes being currently explored for neuromorphic computing. Some of the ways proposed during the last years to implement neuromorphic hardware by using magnetic nanostructures include magnetic skyrmions [

10], magnetic domain walls [

11,

12] or chiral magnets hosting skyrmions [

13].

Here, we introduce an artificial neuron concept centered around the reversible control of a Bloch-point domain wall (BP-DW) in ferromagnetic nanowires. We elucidate the methodologies and present experimental trials, demonstrating that the proposed device meets the requisites and characteristics akin to those of biological neurons. We envision that employing short ferromagnetic nanowires as the foundation for hardware could pave the way for the development of Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) based on reversible topology control. This innovation has the potential to realize low-power ferromagnetic nanowire array chips capable of learning and resolving real-time problems.

2. Methods

Previously, Caso et al. [

14] demonstrated by means of micromagnetic simulations that the energy gap between the two-level system formed by the stable single vortex (SV) and BP-DW metastable states in short ferromagnetic NWs can be overcome by using either spin currents or frequency tuned magnetic pulses. The main goal of the current study is to numerically investigate the control over the transition between SV and the BP-DW states (see

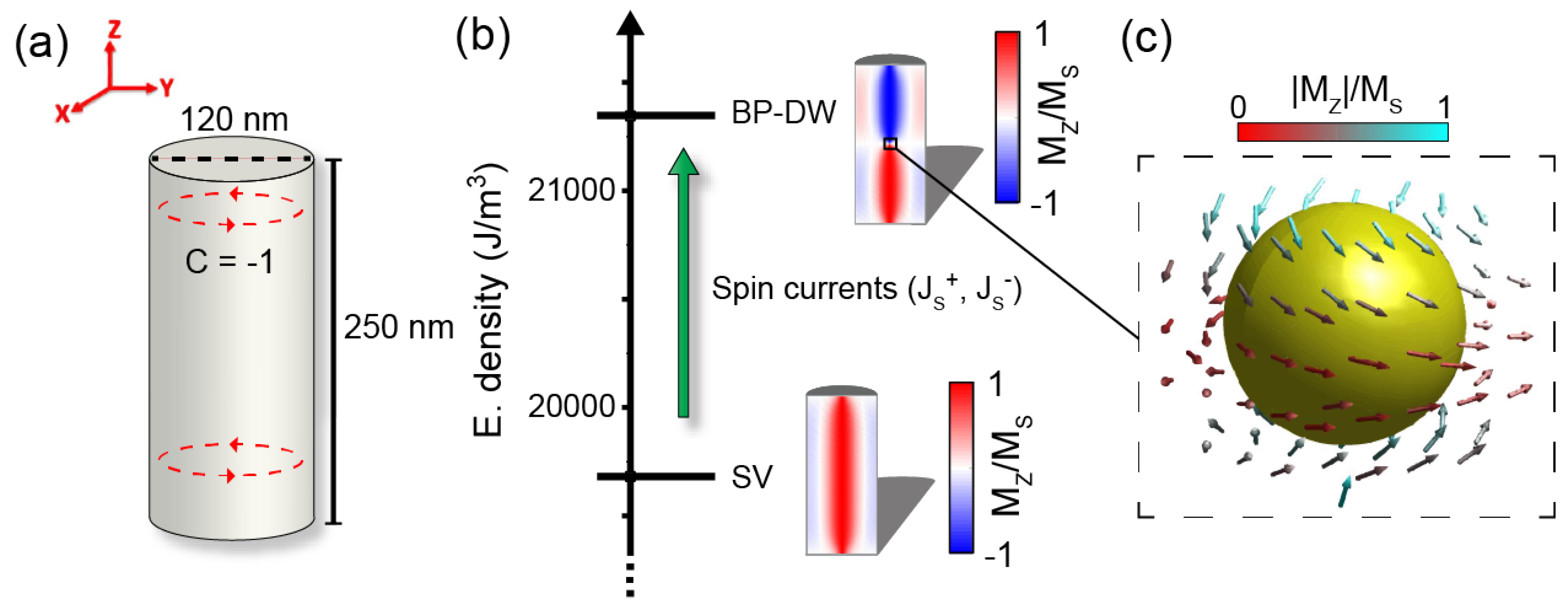

Figure 1b) using a train of spin current pulses with the aim of creating an artificial neuron based on short ferromagnetic nanowires.

Simulation details

Micromagnetic simulations were conducted using the open-source software MuMax3 [

15]. The simulated systems consist of individual NWs composed of FeCoCu. A discretization cell size of

nm was chosen, significantly smaller than the exchange length of approximately 3 nm for FeCoCu [

16]. The cell size is chosen based on the typical scale of the magnetic topological textures which can appear in the system. We estimate a DW and vortex core thickness of about 10 nm. The NW diameter was set at 120 nm and its length at 250 nm. This length was chosen because in previous studies [

14] it resulted in the lowest energy gap between the NW’s stable states. Previously studied NWs were either much longer (more than

m in length) or were almost disk-shaped (circular dots with a thickness of much less than 100 nm). We used typical magnetic parameters of ferromagnetic FeCoCu NWs in our simulations [

17,

18]:

T;

rad/sT;

;

J/m, where

is the saturation magnetization of the NW,

is the gyromagnetic ratio and A

ex and

refer to the exchange stiffness constant and the damping of the NW respectively.

is reduced to 10

−4 in the dynamic simulations to better resolve the modes of the system. The NWs axis was set to be parallel to the

z axis in the cartesian coordinate system (see

Figure 1(a)), i.e., the bases of the NW are placed parallel to the

plane.

Due to their cylindrical geometry, the NWs display a considerable shape anisotropy, which favours the magnetization to be aligned with the NWs axis direction. Its circular shape also invites the NW magnetization to circulate along the axis. For this reason, the SV state is stable in our system and has a slightly lower energy than the other stable state in the NW, the BP-DW state, as seen in

Figure 1(b), emulating two states of different membrane potential in our neuron.

Figure 1(c) depicts the vicinity of the Bloch Point in our system, corresponding to a singularity enclosed in a head-to-head vortex domain wall. No additional magneto-crystalline anisotropies have been introduced in the simulations.

To reveal the primary spin wave (SW) modes, we examined the averaged in-plane magnetization of the system using a Fourier Transform [

19] to transition into the frequency domain. The analysis was conducted following the application of a homogeneous magnetic field pulse of the form:

where H

pulse is the amplitude of the applied field pulse (2 mT), and t

0 denotes the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the pulse (1×10

−12 s). The pulse is modeled using the sinc

function, which demonstrated a better performance than a Gaussian function. This choice of pulse shape results in narrower and more well-defined peaks in the spin wave excitation spectrum obtained through Fourier Transform analysis.

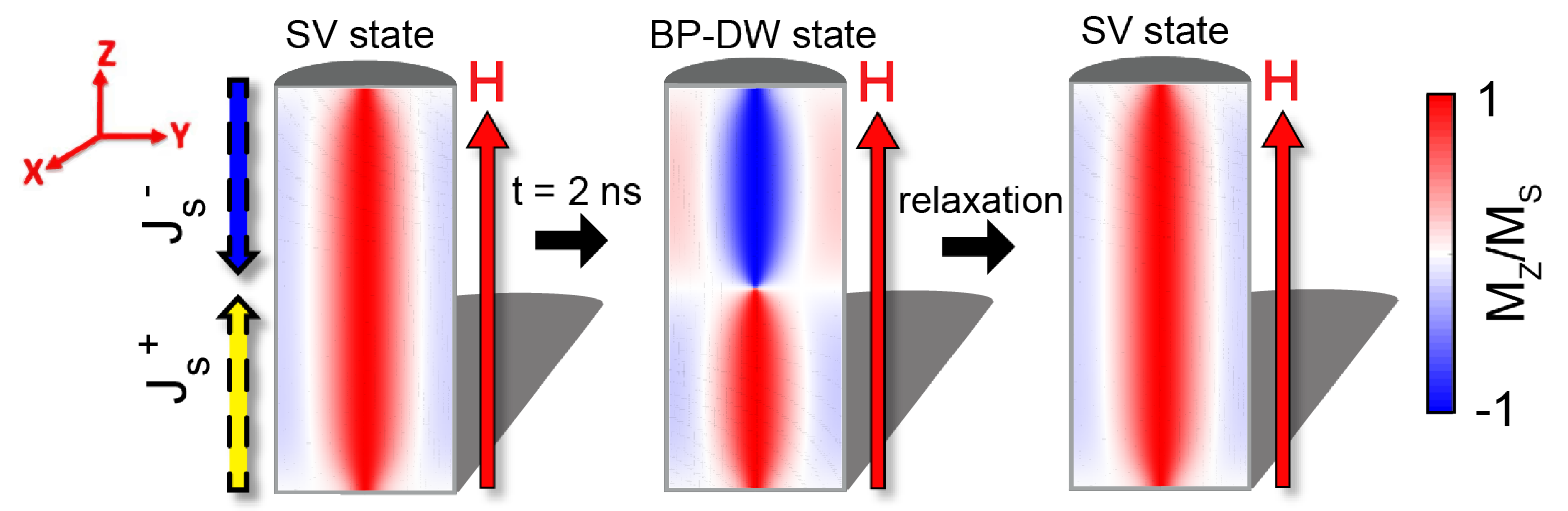

As previously explored by Caso et al. [

14], we examined the transition between the SV and BP-DW states. We claim that this switch fulfills the characteristics of biological neurons under certain field and spin-current conditions. In order to demonstrate that, the initial configuration of the system was set to be a SV state. Afterwards, squared pulsed trains of spin-currents were applied at the opposite faces of the cylinder. These currents are fully polarized (

) and their frequencies are based on those of the SW-modes. Furthermore, we have verified the sensitivity of the AN up to much higher (about 1000 GHz) and much lower (below 1 GHz) frequency in trains of squared pulses. Additionally, a uniform magnetic field in the axial direction (

mT

) was introduced to break axial symmetry and facilitate the system’s return to its initial SV configuration after the transition (see

Figure 2).

3. Proof of concept of the artificial neuron: results and discussion

The LIF (Leaky-Integrate-and-Fire) neuron model [

20] simulates the behavior of a biological neuron by accumulating incoming synaptic currents (integrate with some leak) until it reaches a threshold, triggering a spike or action potential (fire). Here we investigate the different functionalities of a LIFR neuron in relation with our NW system.

3.1. Integrate functionality

To be biofidelic, our artificial neuron must exhibit sensitivity to input pulsed signals (integrate functionality). In the context of our NWs, this criterion is unequivocally met when the spin current pulses reach a sufficient amplitude, causing the axial projection of the magnetization in the SV state to oscillate (see

Figure 3). The energy barrier between the BP-DW and the SV states is overcome for sufficiently high spin current pulses. Introducing a baseline DC spin current of 7

A/m

2 along with the AC (i.e. periodic pulse) spin current inputs with an amplitude of 5

A/m

2, reaching a maximum of 12

A/m

2, ensures a controlled transition, preventing an erratic behavior in the shift from SV to BP-DW states.

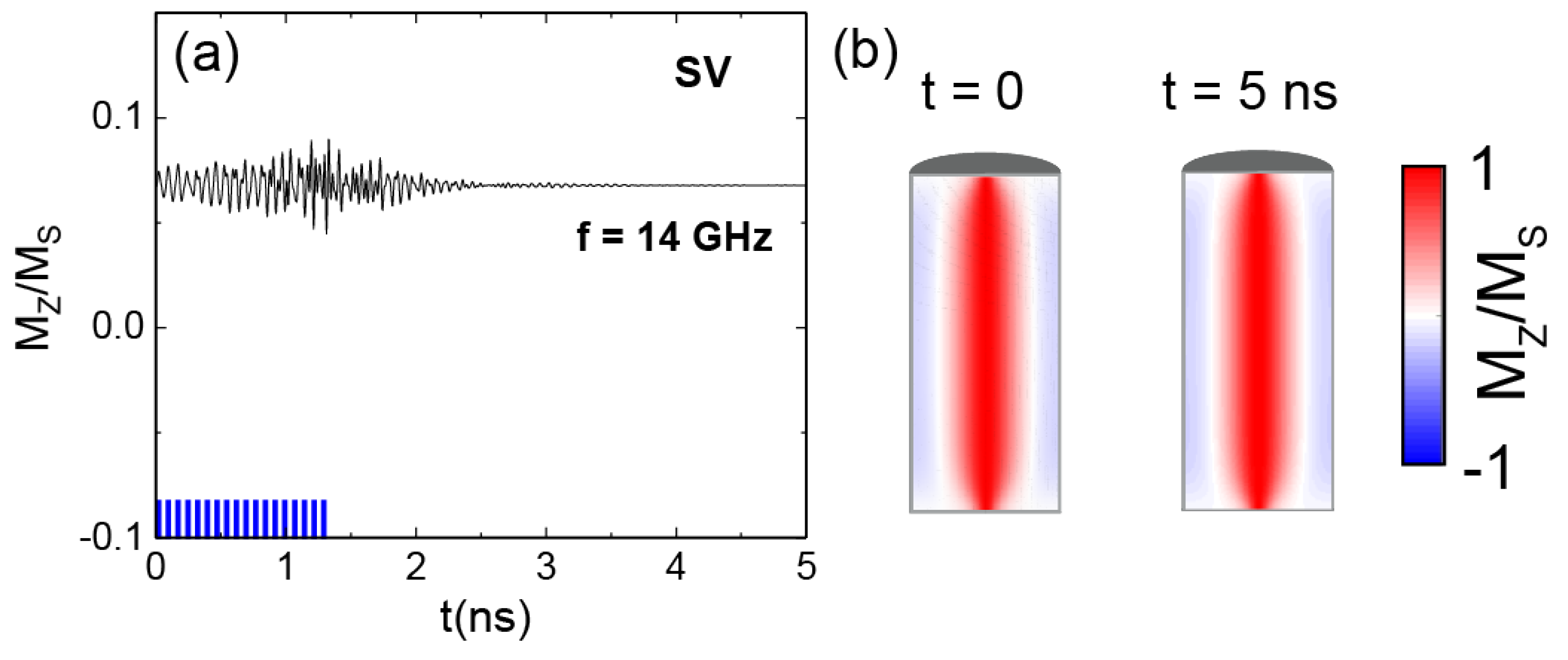

3.2. Leak functionality

The leak functionality in a neuron is fulfilled once there is a passive decay of the membrane potential in the absence of a pulsed input, reflecting the tendency of the membrane in the natural neuron to return to its resting state. Our AN reflects this behavior. Indeed, once the injection of the spin currents is stopped before the fire output, the oscillating AN recovers back into the SV state when sufficient time has passed.

Figure 4(a) shows this behaviour, as the input spin current pulses were introduced just in the first 1.3 nanoseconds and then suddenly stopped. We observe the behavior of the axial SV magnetization configuration in the NW for 5 ns, concluding in the disappearance of the small oscillations.

Figure 4(b) displays is a comparison of axial magnetization cross-sections of the initial magnetization and the magnetization after the 5 ns when the pulses are applied on the first 1.3 nanoseconds, clearly concluding in the same magnetization state and therefore demonstrating the leak functionality of our AN.

3.3. Fire functionality

Once the accumulation of input pulses is large enough, the NW reaches the BP-DW state, identified with the fire functionality in the artificial neuron, reaching a threshold of axial magnetization in the NW of

(see

Figure 3). This activation is a key element for a future neural network based on the proposed NW system, allowing the network to learn and make decisions based on patterns.

Figure 3 shows the controlled transition into the BP-DW for three different frequencies of the applied spin current pulses. Two of them, 16.3 GHz (

Figure 3(a)) and 11.9 GHz (

Figure 3(c)), correspond to eigenmodes of the system (see

Appendix A for the spin wave spectra). On the other hand, 14 GHz (

Figure 3(b)) does not coincide with any eigenmode. In our case, the AN reaches the BP-DW state even if the injected spin current pulses do not precisely align with an eigenfrequency of the system, as it is shown in

Figure 3(b) for 14 GHz. However, it is mandatory that the frequency of these pulses is in the range of the eigenmode. If the frequency of the pulses is too low or too high, the transition is accomplished only due to the DC spin current baseline. For this type of state transition with only DC spin currents, Caso et al [

14] demonstrated a switching time of

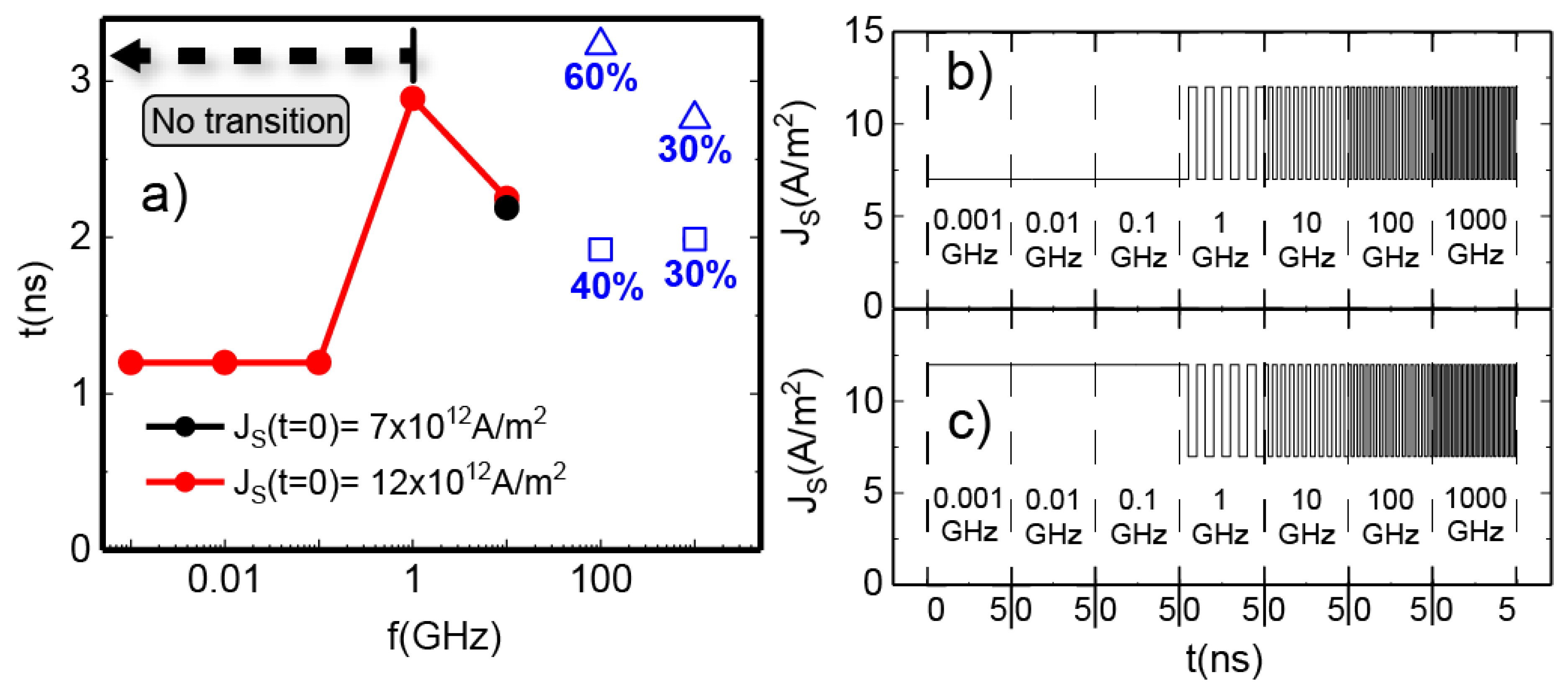

ns, which is not improved for either very high or very low frequency input pulses (see

Figure 5). However, for an input oscillating signal in the GHz range, the switching time is improved to up to 2 ns (see

Figure 3), proving the effect of the AC spin currents.

Figure 5 shows the SV to BP-DW transition stimulated by input AC spin current pulses in a broad frequency range. At very low input pulse frequencies (10

−3-10

−1 GHz), the AC component of the spin currents remains constant for the duration of the simulation until the transition occurs (or if there is no transition, up to at least 5 ns, see

Figure 5(b,c)). In such cases, the switch behaves as if there was only an injection of a DC spin current. Initiating the amplitude of the spin currents at 7

A/m

2 for

, the current density is so low at low frequencies that the system enters in a chaotic behaviour before undergoing any transition, as demonstrated in [

14]. When the pulses start at the maximum of 5

A/m

2, the system behaves as if a constant current of 12

A/m

2 was being applied, transitioning into BP-DW state in 1.2 ns. In

Figure 5, it is shown that only in the range of the tenths of GHz a consistent firing time around 2.2 ns is achieved whether the pulses start behave as sine or as cosine functions. The input AC spin currents are of great importance for the switch, since the transition fails to occur with just a baseline of DC spin currents when the baseline is not extremely high and thus, very energetically inefficient. It was also checked that a low DC baseline (4

A/m

2) with an AC input of 5

A/m

2 did not achieve any transition, demonstrating that both components are helpful in the switch of states.

In

Figure 5 we also show the stochastic nature of the system at high input pulses frequencies: for the ranges of 100 GHz and 1000 GHz, the time of transition or even its presence have a strong dependence on the initial conditions of the pulses. To confirm the stochasticity of the system at high frequencies, simulations at these ranges were repeated ten times. In both cases, the amplitude of the spin current pulses at t=0 was not a factor, since the frequency was so high. Remarkably, for 100 GHz, all simulations resulted in the NW entering the BP-DW state, but they were distributed between being stable at 1.9 ns (40% of the time) or 3.2 ns (60% of the time). For 1000 GHz, the transition was stabilized in 60% of cases, 30% in 2 ns and 30% in 2.8 ns. The remaining 40% of the time the transition was uncontrolled and the result was a chaotic system behavior. Rather than being considered a drawback, this stochastic nature is also observed in the brain and neurons. Hence, stochasticity becomes a trait that an artificial neuron may posses in order to be implemented in neuromorphic computing [

1], and could be leveraged particularly in this high-frequency ranges. However, for tenths of GHz, (aligning with the frequency range of the spin wave modes, see

Appendix A) the transition becomes more efficient and controlled. This frequency range showcases not only deterministic behavior but also similar transition times for the two AC input pulses starting points in several simulations.

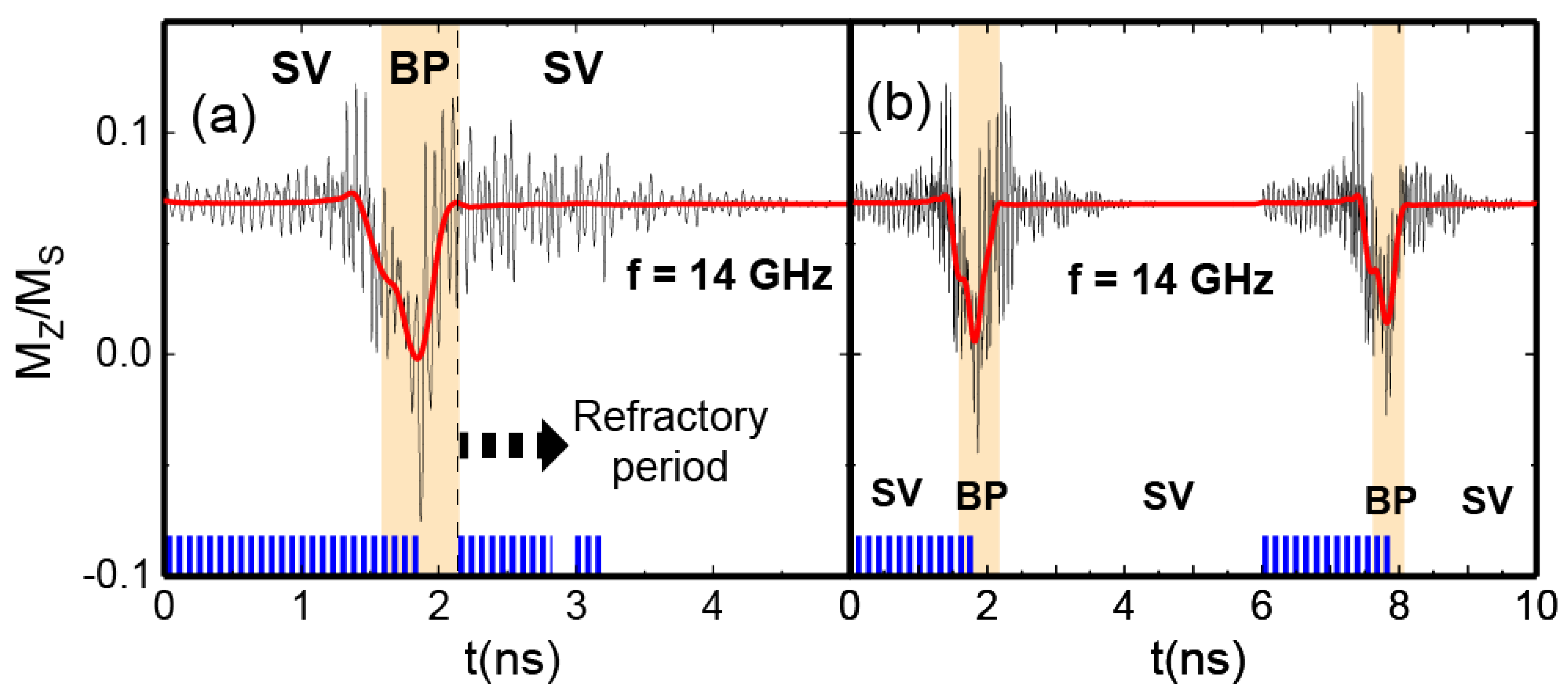

3.4. Refractory period

The basic LIF concept can be extended by adding a refractory period in which the neuron is unresponsive to new inputs, mimicking the biological neuron brief recovery phase after firing an activation potential. In the case of our NW based AN, this is accomplished after firing in the BP-DW state and switching again to the SV, for 1 ns, as shown in

Figure 6(a). Once enough time has passed and the system has relaxed correctly, it can be restarted and the same process may be accomplished again.

Figure 6(b) shows this. We can determine that the refractory period in our NW-based AN is between 3 and 4 ns.

4. Conclusions and outlook

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that short ferromagnetic nanowires (with a length of twice the diameter), where the energies of two topologically different magnetic states (Bloch-point and single vortex) are close, could be used to create a versatile device for neuromorphic computing. The stable functionality of the suggested artificial neuron has been verified through testing its functionalities such as integration, leakage, firing and having a refractory period.

One significant advantage of magnetic nanowires, compared to other proposed magnetic nanostructures for serving as artificial neurons, is the availability of expertise in growing self-organized arrays of cylindrical ferromagnetic nanowires using templates [

21,

22]. Such AN arrays would also facilitate large areal density, interconnections between ANs and input (output) communication. These advantages in crafting ANNs using ferromagnetic NWs are in contrast with the difficulty and requirements needed to fabricate arrays of ANs based on magnetic tunnel junctions, memristors, or skyrmions [

8] via nanolithography, which could stimulate the development of the ANs proposed here.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.G.A.; methodology, C.S., D.C. and F.G.A.; software, C.S., D.C.; validation, C.S., D.C. and F.G.A.; formal analysis, C.S., D.C.; investigation, C.S., D.C., and F.G.A.; resources, F.G.A.; data curation, C.S. and D.C.; writing—original draft preparation, F.G.A., D.C., C.S.; writing—review and editing, F.G.A., D.C., and C.S.; visualization, D.C. and C.S.; supervision, F.G.A.; project administration, F.G.A.; funding acquisition, F.G.A.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. Authors thank Pablo Tuero and Cesar González-Ruano for the discussions.

Funding

The work in Madrid was supported by Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (PID2021-124585NB-C32 and TED2021-130196B-C22). F.G.A. also acknowledges financial support from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation through the María de Maeztu Programme for Units of Excellence in R&D (CEX2018-000805-M) and “Acción financiada por la Comunidad de Madrid en el marco del convenio plurianual con la Universidad Autónoma de Madrid en Línea 3: Excelencia para el Profesorado Universitario”. C.S. Acknowledges Material Science Institute Nicolas Cabrera INC for Research Award 2023.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest

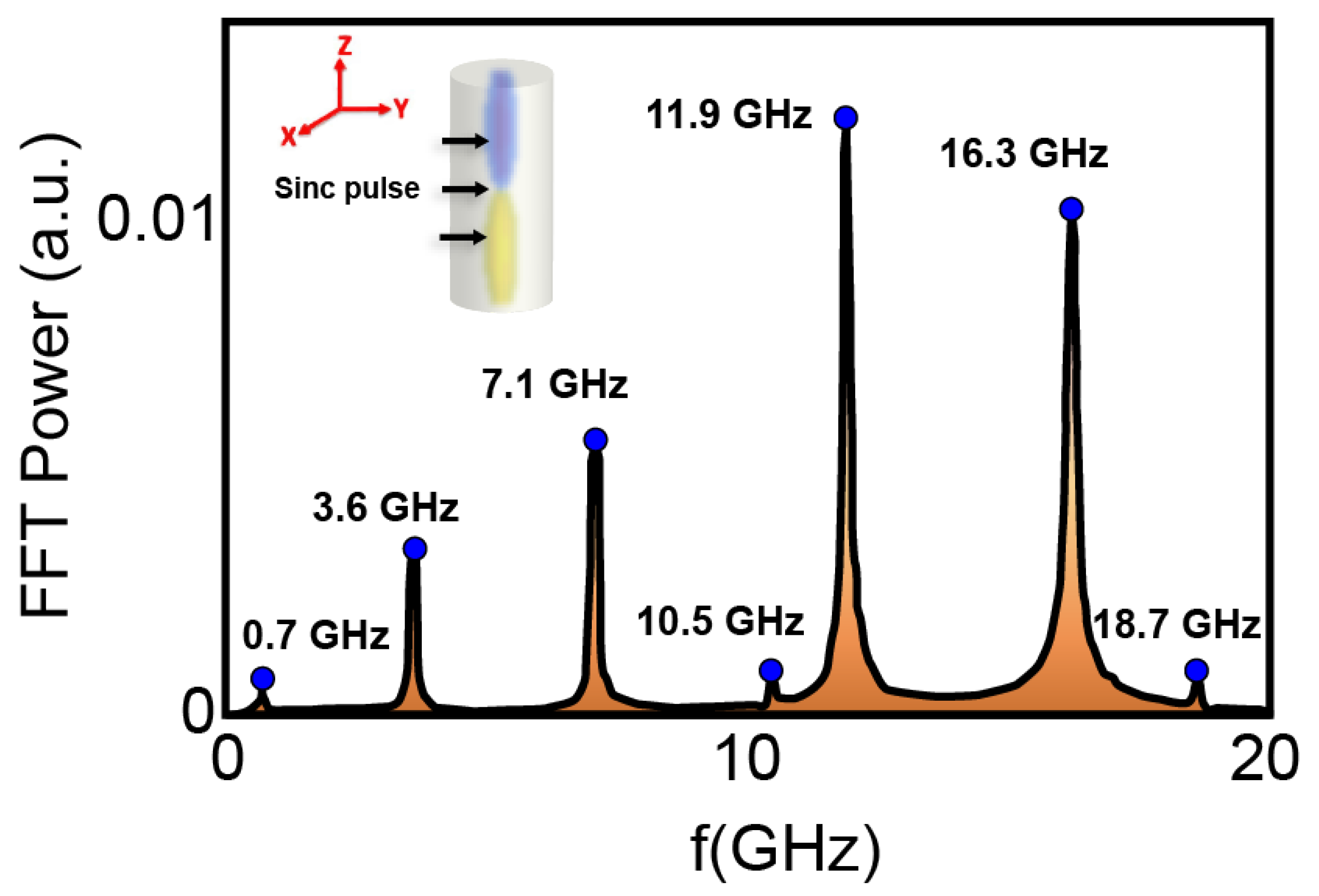

Appendix A. Eigenmodes of the NW in the BP-DW state

Figure A1.

Spin wave modes of the 250 nm length NW investigated in the BP-DW magnetization state. Inset shows the direction of the applied microwave magnetic field sinc pulse to excite the spin eigenmodes of the system

Figure A1.

Spin wave modes of the 250 nm length NW investigated in the BP-DW magnetization state. Inset shows the direction of the applied microwave magnetic field sinc pulse to excite the spin eigenmodes of the system

The main spin wave modes of the BP-DW state in a 250 nm FeCoCu NW are investigated. We found the typical low frequency gyrotropic mode (0.7 GHz), and other higher frequency azimuthal modes [

14]. The most intense mode corresponds to 11.9 GHz, as expected. This frequency range is used in our input spin current pulses to make the SV to BP-DW switch.

References

- Marković, D.; Mizrahi, A.; Querlioz, D.; Grollier, J. Author Correction: Physics for neuromorphic computing. Nature Reviews Physics 2021, 3, 671–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Valle, J.; Ramírez, J.G.; Rozenberg, M.J.; Schuller, I.K. Challenges in materials and devices for resistive-switching-based neuromorphic computing. Journal of Applied Physics 2018, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romera, M.; Talatchian, P.; Tsunegi, S.; Abreu Araujo, F.; Cros, V.; Bortolotti, P.; Trastoy, J.; Yakushiji, K.; Fukushima, A.; Kubota, H.; Yuasa, S.; Ernoult, M.; Vodenicarevic, D.; Hirtzlin, T.; Locatelli, N.; Querlioz, D.; Grollier, J. Vowel recognition with four coupled spin-torque nano-oscillators. Nature 2018, 563, 230–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borders, W.A.; Pervaiz, A.Z.; Fukami, S.; Camsari, K.Y.; Ohno, H.; Datta, S. Integer factorization using stochastic magnetic tunnel junctions. Nature 2019, 573, 390–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, B.; He, Y.; Xin, Y.; Yuan, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, Z.; Liang, G. Unconventional computing based on magnetic tunnel junction. Applied Physics A 2023, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chumak, A.V.; Kabos, P.; Wu, M.; Abert, C.; Adelmann, C.; Adeyeye, A.O.; Akerman, J.; Aliev, F.G.; Anane, A.; Awad, A.; Back, C.H.; Barman, A.; Bauer, G.E.W.; Becherer, M.; Beginin, E.N.; Bittencourt, V.A.S.V.; Blanter, Y.M.; Bortolotti, P.; Boventer, I.; Bozhko, D.A.; Bunyaev, S.A.; Carmiggelt, J.J.; Cheenikundil, R.R.; Ciubotaru, F.; Cotofana, S.; Csaba, G.; Dobrovolskiy, O.V.; Dubs, C.; Elyasi, M.; Fripp, K.G.; Fulara, H.; Golovchanskiy, I.A.; Gonzalez-Ballestero, C.; Graczyk, P.; Grundler, D.; Gruszecki, P.; Gubbiotti, G.; Guslienko, K.; Haldar, A.; Hamdioui, S.; Hertel, R.; Hillebrands, B.; Hioki, T.; Houshang, A.; Hu, C.M.; Huebl, H.; Huth, M.; Iacocca, E.; Jungfleisch, M.B.; Kakazei, G.N.; Khitun, A.; Khymyn, R.; Kikkawa, T.; Klaui, M.; Klein, O.; Klos, J.W.; Knauer, S.; Koraltan, S.; Kostylev, M.; Krawczyk, M.; Krivorotov, I.N.; Kruglyak, V.V.; Lachance-Quirion, D.; Ladak, S.; Lebrun, R.; Li, Y.; Lindner, M.; Macedo, R.; Mayr, S.; Melkov, G.A.; Mieszczak, S.; Nakamura, Y.; Nembach, H.T.; Nikitin, A.A.; Nikitov, S.A.; Novosad, V.; Otalora, J.A.; Otani, Y.; Papp, A.; Pigeau, B.; Pirro, P.; Porod, W.; Porrati, F.; Qin, H.; Rana, B.; Reimann, T.; Riente, F.; Romero-Isart, O.; Ross, A.; Sadovnikov, A.V.; Safin, A.R.; Saitoh, E.; Schmidt, G.; Schultheiss, H.; Schultheiss, K.; Serga, A.A.; Sharma, S.; Shaw, J.M.; Suess, D.; Surzhenko, O.; Szulc, K.; Taniguchi, T.; Urbanek, M.; Usami, K.; Ustinov, A.B.; van der Sar, T.; van Dijken, S.; Vasyuchka, V.I.; Verba, R.; Kusminskiy, S.V.; Wang, Q.; Weides, M.; Weiler, M.; Wintz, S.; Wolski, S.P.; Zhang, X. Advances in Magnetics Roadmap on Spin-Wave Computing. IEEE Transactions on Magnetics 2022, 58, 1–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara, A.; Robledo Moreno, J.; Guslienko, K.Y.; Aliev, F.G. Information processing in patterned magnetic nanostructures with edge spin waves. Scientific Reports 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blachowicz, T.; Ehrmann, A. Magnetic Elements for Neuromorphic Computing. Molecules 2020, 25, 2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, J.Y.; Chen, C.Y.; Ling, D.C.; Martínez, I.; González-Ruano, C.; Aliev, F.G. Low-Frequency 1/f Noise Characteristics of Ultra-Thin AlOx-Based Resistive Switching Memory Devices with Magneto-Resistive Responses. Electronics 2021, 10, 2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro de Assis, I.; Mertig, I.; Göbel, B. Biskyrmion-based artificial neuron. Neuromorphic Computing and Engineering 2023, 3, 014012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brigner, W.H.; Friedman, J.S.; Hassan, N.; Jiang-Wei, L.; Hu, X.; Saha, D.; Bennett, C.H.; Marinella, M.J.; Incorvia, J.A.C.; Garcia-Sanchez, F. Shape-Based Magnetic Domain Wall Drift for an Artificial Spintronic Leaky Integrate-and-Fire Neuron. IEEE Transactions on Electron Devices 2019, 66, 4970–4975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mah, W.L.W.; Chan, J.P.; K. R., G.; Naik, V.B.; Piramanayagam, S.N. Leakage function in magnetic domain wall based artificial neuron using stray field. Applied Physics Letters 2023, 123. [CrossRef]

- Lee, O.; Wei, T.; Stenning, K.D.; Gartside, J.C.; Prestwood, D.; Seki, S.; Aqeel, A.; Karube, K.; Kanazawa, N.; Taguchi, Y.; Back, C.; Tokura, Y.; Branford, W.R.; Kurebayashi, H. Task-adaptive physical reservoir computing. Nature Materials 2023, 23, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caso, D.; Tuero, P.; García, J.; Guslienko, K.Y.; Aliev, F.G. Dynamics and Reversible Control of the Bloch-Point Vortex Domain Wall in Short Cylindrical Magnetic Nanowires. Physical Review Applied 2023, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vansteenkiste, A.; Leliaert, J.; Dvornik, M.; Helsen, M.; García-Sánchez, F.; Waeyenberge, B.V. The design and verification of MuMax3. AIP Advances 2014, 4, 107133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berganza, E.; Bran, C.; Jaafar, M.; Vázquez, M.; Asenjo, A. Domain wall pinning in FeCoCu bamboo-like nanowires. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 29702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Roldán, J.A.; del Real, R.P.; Bran, C.; Vazquez, M.; Chubykalo-Fesenko, O. Magnetization pinning in modulated nanowires: from topological protection to the “corkscrew” mechanism. The Royal Society of Chemistry, Nanoscale 2018, 10, 5923–5927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, J.M.; Nembach, H.T.; Silva, T.J.; Boone, C.T. Precise determination of the spectroscopic g-factor by use of broadband ferromagnetic resonance spectroscopy. Journal of Applied Physics 2013, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.P.; Eames, P.; Engebretson, D.M.; Berezovsky, J.; Crowell, P.A. Single-shot dynamics of spin–orbit torque and spin transfer torque switching in three-terminal magnetic tunnel junctions. Phys. Rev. B 2003, 67, 020403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunel, N.; van Rossum, M.C.W. Quantitative investigations of electrical nerve excitation treated as polarization: Louis Lapicque 1907 · Translated by:. Biological Cybernetics 2007, 97, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, R.; Carvalho-Santos, V.L.; Espejo, A.P.; Laroze, D.; Chubykalo-Fesenko, O.; Altbir, D. Oscillatory behavior of the domain wall dynamics in a curved cylindrical magnetic nanowire. Physical Review B 2017, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazquez, M. Cylindrical nanowire arrays: From advanced fabrication to static and microwave magnetic properties. Journal of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials 2022, 543, 168634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).