1. Introduction

More than 7,000,000 patients have died of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) worldwide [

1]. Acute myocardial damage, cardiac conduction disturbances, and chronic cardiovascular injuries, including thrombosis, can occur with COVID-19 [

2,

3]. The increased risk of cardiac death in patients with COVID-19 who may or may not have had previous cardiovascular diseases has also been reported [

4]. Although risk stratification in the early stages of COVID-19 is important when considering therapeutic strategies, surrogate markers have not yet been established to predict prognosis. Changes in the electrocardiograms of patients with COVID-19 include QT prolongation, ST-T changes, and other repolarization abnormalities [

5].

Recently, noninvasive 24-h Holter electrocardiograms have been used to measure electrocardiographic markers as predictors of sudden cardiac death or lethal arrhythmia in patients with cardiac diseases, including ischemic heart disease and heart failure [

6,

7,

8,

9]. Noninvasive electrocardiogram markers derived from ambulatory electrocardiogram devices indicate late potential (LP), T-wave alternans (TWA), heart rate turbulence (HRT), and heart rate variability (HRV); these parameters can be measured simultaneously during a single sampling inspection for predicting fatal arrhythmias or sudden cardiac death in patients with structural heart disease [

6,

7,

8,

9]. These parameters are known as ambulatory electrocardiographic markers (AECG-Ms). However, the usefulness of AECG-Ms in the early phases of treating COVID-19 pneumonia has been seldom reported. Herein, we report three cases in which all AECG-Ms were positive in patients with COVID-19.

2. Case Presentation

2.1. Case 1

A 78-year-old woman presented with coughing and dyspnea and was hospitalized with a diagnosis of COVID-19. She had a history of chronic kidney disease but no prior history of significant cardiovascular diseases. Her vital signs on admission are shown in

Table 1. QT prolongation and ST-T changes are not shown (

Table 1).

To validate the usefulness of AECG-Ms in the acute phase of COVID-19, a high-resolution Holter electrocardiogram (1.5 V, 1000 Hz; Fukuda Denshi Co, Tokyo, Japan) was attached to the patient for 24 h within 48 h of admission, and LPs, TWA, HRV, and HRT were measured. LPs were determined as positive when at least two of the following three criteria were met: (1) a filtered QRS duration of >135 milliseconds, (2) a root-mean-square voltage of the signals of <20 μV in the last 40 milliseconds, and (3) a duration of >38 milliseconds of the low-amplitude signal after the voltage decreased to less than 40 μV [

10]. TWA was determined to be positive when the reference value was exceeded: the TWA reference values were 19.9 μV when the noise level was less than 10 mV and 23.6 μV when the noise level remained between 10 and 20 mV [

11]. For HRV, the standard deviation of normal NN intervals was used as a parameter, and the cutoff value for poor prognosis was set as a standard deviation of normal NN intervals of <75 milliseconds [

12]. For HRT, turbulence onset and turbulence slope were used as parameters, and a patient was determined to have abnormal HRT if the turbulence onset was ≥0% and the turbulence slope was ≤2.5 milliseconds per RR interval (Category 2) [

9]. In addition, the cardiac function of the right and left ventricles was evaluated using cardiac ultrasonography. Procalcitonin and C-reactive protein levels were used as inflammatory markers. Soluble fibrin monomer complex, which is included in the evaluation of disseminated intravascular coagulation syndrome, was used as a coagulation marker. Laboratory data are summarized in

Table 2.

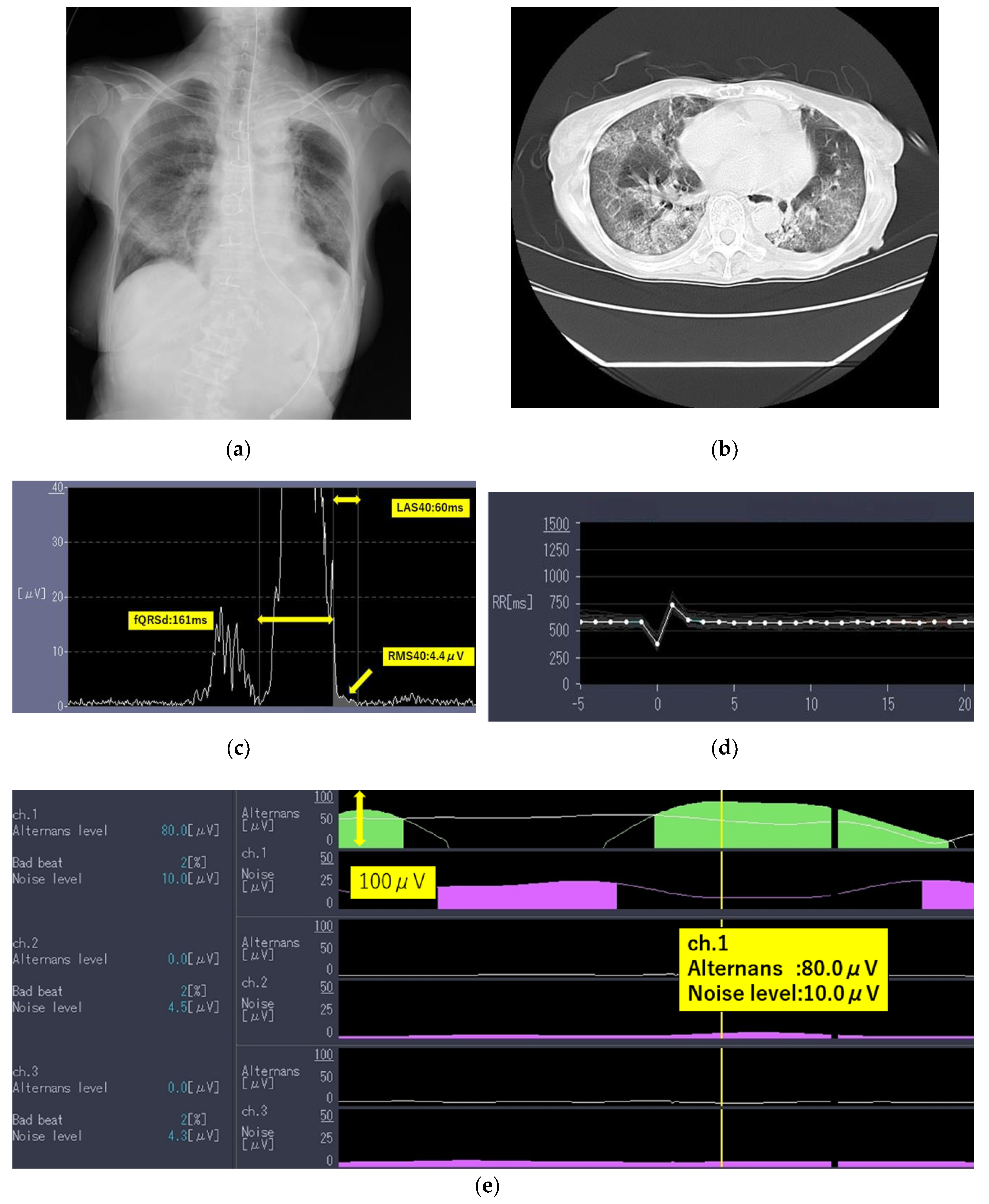

The laboratory test findings of Case 1 indicated that inflammatory marker and brain natriuretic peptide levels were moderately to highly elevated. Chest radiographs (

Figure 1a) and computed tomography images (

Figure 1b) showed extensive ground-glass opacities and a crazy-paving pattern. The 24-h Holter electrocardiography performed on admission showed that all AECG-Ms were positive (

Table 3;

Figure 1c–e).

The patient was treated with heparin at 10,000 U/day for 10 days, methylprednisolone at 1000 mg/day for 3 days, and dexamethasone at 6.6 mg/day for 5 days. She was not treated with any antiviral agents as she had poor renal function. The patient showed signs of improvement; however, an increase in BNP levels from 178 pg/mL up to 338 pg/mL, unexpected deterioration in renal function, electrolyte imbalance, and bleeding from the gastrointestinal tract were observed. She died of respiratory failure mainly because of pneumonia with mild heart failure preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) on day 12 after admission.

2.2. Case 2

A 76-year-old man complaining of dyspnea was hospitalized after being diagnosed as having COVID-19 using a real-time polymerase chain reaction test. He had a past history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and cerebral infarction but no prior history of significant cardiovascular diseases. His vital signs on admission are shown in

Table 1. QT prolongation and ST-T changes are not shown (

Table 1). The laboratory data gathered are summarized in

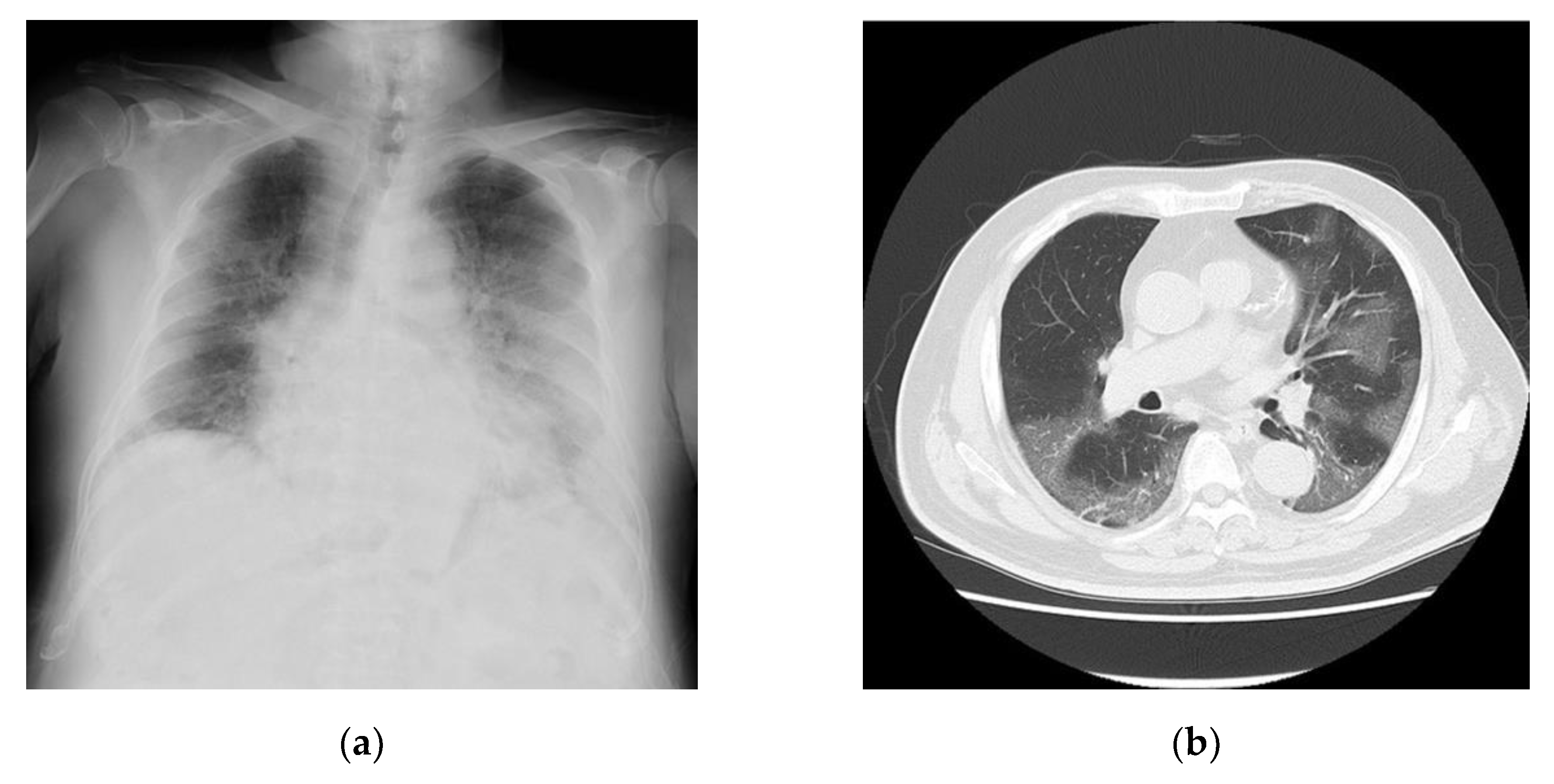

Table 2. The findings indicated that the inflammatory markers for this patient were moderately to highly elevated. Chest radiographs (

Figure 2a) and computed tomography images (

Figure 2b) revealed extensive ground-glass opacities. A 24-h Holter electrocardiography performed on admission showed that all AECG-Ms were positive (

Table 3). The patient was treated with heparin at 14,000 U/day for 12 days, remdesivir at 200 mg/day for 10 days, and dexamethasone at 6.6 mg/day for 10 days. However, his dyspnea worsened, chest radiographs showed spreading ground-glass opacities, and he died owing to respiratory failure on day 12 after admission.

2.3. Case 3

A 67-year-old man complaining of coughing and dyspnea was hospitalized with a diagnosis of COVID-19. He had a history of renal and lung cancers and pancreatic diabetes but no significant cardiovascular diseases. His vital signs on admission are shown in

Table 1. QT prolongation and ST-T changes are not shown (

Table 1). The laboratory data are summarized in

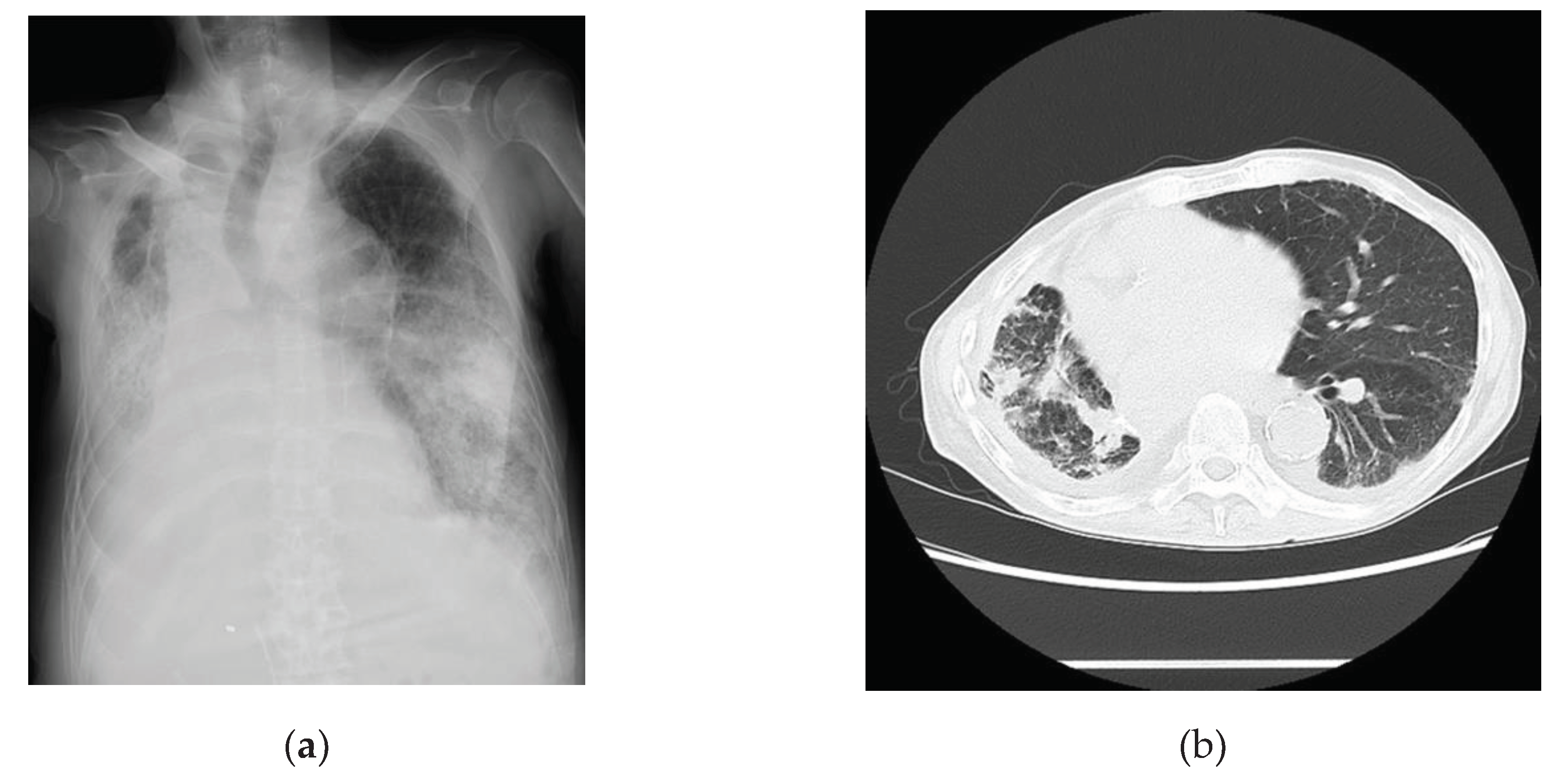

Table 2. Examination findings for this patient indicated that the levels of inflammatory markers were mildly elevated. Chest radiographs (

Figure 3a) and computed tomography images (

Figure 3b) revealed pneumonia. A 24-h Holter electrocardiography performed on admission showed that all AECG-Ms were positive (

Table 3). The patient was treated with heparin, remdesivir, and dexamethasone at 6.6 mg/day for 5 days. Oxygen saturation showed improvement on day 4 after admission, but the patient’s condition worsened from day 6, the BNP level increased from 162 pg/mL up to 611 pg/mL, and carbon dioxide narcosis was induced. He was treated with methylprednisolone at 1000 mg/day for 3 days, remdesivir at 100 mg/day for 9 days, and heparin at 5,000 U/day for 4 days, but he died owing to pneumonia with mild HFpEF on day 10 after admission.

Table 4.

Ambulatory echocardiographic marker data recordings.

Table 4.

Ambulatory echocardiographic marker data recordings.

| Marker |

Abnormal value or cutoff value |

Case 1 |

Case 2 |

Case 3 |

| Late potential |

|

|

|

|

| fQRS, millisecond |

>135 |

128 |

136 |

160 |

| RMS40, μV |

<20 |

4.4 |

1.5 |

10.4 |

| LAS40, millisecond |

>38 |

60 |

53 |

57 |

| Determination |

|

Positive |

Positive |

Positive |

| T-wave alternans |

|

|

|

|

| Noise level, mV |

(*1), (*2) |

10.0 |

9.6 |

12.3 |

| TWA, μV |

(*1), (*2) |

80.0 |

28.4 |

35.7 |

| Determination |

|

Positive |

Positive |

Positive |

| Heart rate variability |

|

|

|

|

| SDNN, millisecond |

<75 |

41.6 |

64.0 |

64.0 |

| Determination |

|

Positive |

Positive |

Positive |

| Heart rate turbulence |

|

|

|

|

| TO, % |

≥0 |

0.01 |

0.01 |

0.01 |

| TS, millisecond/RR interval |

≤2.5 |

1.30 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

| Determination |

|

Abnormal

(Category 2) |

Abnormal

(Category 2) |

Abnormal

(Category 2) |

4. Discussion

All three patients died owing to respiratory failure caused by COVID-19; in all three patients, the AECG-Ms—LPs, TWA, HRT, and HRV—were positive. In Cases 1 and 3, the patients were suspected to have comorbid HFpEF. In Case 2, there was a possibility that the patient had mild HFpEF. Although no remarkable consistent increases in clinical markers were observed, there is a possibility that the AECG-Ms have the potential to be risk stratifiers of COVID-19 pneumonia in the early phase of admission. AECG-Ms are reportedly useful in patients with structural cardiac diseases or chronic kidney disease; the markers could be used as predictors in cases where no obvious history of cardiac diseases is present at the time of admission to the hospital. The probability of each AECG-M parameter being positive in the absence of cardiovascular diseases ranges from 5% to 10% [

9,

11,

13,

14]. Therefore, the probability of all four AECG-Ms being positive in a healthy heart is extremely low. Cases 1 and 3 had mild HFpEF at the time of admission, and heart failure worsened slightly during the clinical course. In contrast, case 2 had no apparent heart failure initially, but mild HFpEF also progressed during the clinical course. HFpEF might be triggered by COVID-19 pneumonia but very mildly. Notably, the AECG-Ms were positive for all parameters in these cases.

In patients who die because of COVID-19, the cardiovascular, immune, and coagulation mechanisms necessary to support life are disrupted approximately 3–4 weeks after viral exposure owing to cytokine storms [

15]. Consequently, the levels of cardiac biomarkers such as troponin and brain natriuretic peptide increase in patients with COVID-19 depending on disease severity.

No obvious cardiac disease was noted in Case 2 initially; however, a diabetic comorbidity and chronic kidney disease were present, and the risk of atherosclerosis seemed to be high. In all cases, systolic function was preserved, but increased BNP and/or cardio-thoracic ratio suggested the possibility of mild-to-moderate HFpEF at the time of UCG. However, the AECG-Ms—considered to be prognostic predictors of sudden cardiac death—were positive. We speculate that myocardial remodeling and ischemia were involved in these cases, as described below. Although no obvious cardiac disease was noted, Case 1 had a history of chronic kidney disease, and the AECG-Ms may have been useful for investigating cardiorenal syndrome. Hashimoto et al. reported that AECG-Ms are useful for predicting sudden cardiac death and fatal arrhythmias in patients with chronic kidney disease [

16]; our findings of Case 1 are consistent with those of their study. Furthermore, Cases 1 and 3 also showed elevated BNP levels, suggesting the presence of mild HFpEF. In contrast, surprisingly, the AECG-Ms were positive for all items in Case 2, even though there was no obvious cardiac disease initially. In COVID-19 pneumonia, AECG-Ms might have the potential to predict sudden cardiac death in patients without obvious cardiac disease.

In the cases reported here, we analyzed four specific parameters: LPs, TWA, HRV, and HRT. These markers have been reported to be predictive of fatal arrhythmias and/or cardiac death in patients with both cardiac and chronic kidney diseases [

6]. All AECG-Ms have been reported to be highly useful, especially for treating ischemic heart disease [

17,

18,

19,

20]. LPs and TWA are more likely to be positive for remodeling resulting from cardiac diseases. LPs reflect a conduction delay at sites of myocardial degeneration between the necrotic and healthy myocardia; they are useful for predicting the occurrence of lethal ventricular arrhythmias because conduction delays can be an electrical substrate for VT such as myocardial infarction and cardiomyopathy. TWA is a well-established method for testing beat-to-beat T-wave amplitude alternations at the microvolt level and is thought to reflect repolarization abnormalities that lead to fetal arrhythmias. Similar to LPs, TWA is particularly useful in predicting lethal ventricular arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death in patients with ischemic heart disease. Tondas et al. reported that TWA levels are elevated at discharge compared with those at admission in patients with COVID-19 initially [

21]. HRV evaluates autonomic function based on variability in RR intervals. Many studies have revealed that patients with a small variability have poor prognosis. In patents with COVID-19, HRV alone has been described as useful for predicting prognosis [

22]. The HRT measures acceleration in the early phase and deceleration in the late phase of the RR interval derived from baroreceptor reflexes after ventricular extrasystoles to assess the autonomic imbalance associated with poor prognosis, especially in ischemic heart disease.

In the current communication, the AECG-Ms were positive in patients with COVID-19 who did not show prominent abnormalities in inflammatory and coagulation laboratory and UCG markers or have a history of cardiac disease. We speculate that two pathophysiological considerations may support these findings. 1) Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 may cause angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptor-mediated myocardial remodeling. 2) Global myocardial ischemia is caused by hypoxemia due to spasms and thrombus formation.

Regarding myocardial remodeling, the expression of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptors decreases in conjunction with that of intramyocardial angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptors and viral spike protein, and then, angiotensin 2 expression increases through positive feedback. This, in turn, activates ADAM17, which activates TNF-α, thereby triggering inflammation. This mechanism is thought to cause progressive remodeling of myocardial tissues, resulting in electrophysiological substrate abnormalities.

Global myocardial ischemia may play an important role as a modifier. Unlike localized ischemia, such as in coronary artery disease, global myocardial ischemia may present as diffuse myocardial injury caused by various mechanisms. Myocardial ischemia in patients with COVID-19 may be caused by 1) an oxygen supply-and-demand imbalance caused by pneumonia, 2) a vascular spasm due to immune cell activation, and 3) plaque disruption and embolization due to virus-induced endothelial cell injury [

23].

The direct cause of death in all three cases in this study was mainly respiratory failure due to severe pneumonia and comorbidities with mild HFpEF. The AECG-Ms, markers for cardiac death, were positive in all cases. The reason for this is that in severe COVID-19 cases, myocardial remodeling and global myocardial ischemia progress in parallel with respiratory failure; although patients often eventually die owing to respiratory failure, myocardial damage may also occur. The markers may acutely reflect a condition that is becoming more severe owing to a cytokine storm at an earlier stage; however, we only report on three cases here, and the usefulness of AECG-Ms should be examined in studies with large populations.

The phenomena of all four AECG-M parameters being positive is unusual in patients without a prior history of significant cardiac disease. Therefore, COVID-19 might cause electrophysiological modifications as a result of mild HFpEF. Further studies are needed to accumulate more data and statistically determine the usefulness of the AECG-Ms.

This study had some limitations. We could not evaluate tissue Doppler using UCG because the UCG equipment at the COVID-19 department of our hospital did not have the tissue Doppler function. Furthermore, we could not measure the E/e', and therefore, the precise diastolic function was unknown for the three cases. However, apparently, the systolic function was preserved in all three cases and the BNP level progressively increased during the clinical course, especially in Cases 1 and 3. Therefore, the cases could have been affected by HFpEF.

5. Conclusions

Although AECG-Ms are prognostic markers for cardiac death in patients with apparent heart diseases, these markers were all positive in all three patients who had mild HFpEF and died owing to COVID-19. AECG-Ms have the potential to acutely capture damage to the cardiac system in patients in the early phase of COVID-19 and thus may become predictive tools for detecting cytokine storms and respiratory failure with mild heart failure in the near future. If the clinical utility of AECG-Ms is made evident through studies using a large number of patients with COVID-19, the markers may be used as an early diagnostic tool to determine whether a patient should be critically managed.

Author Contributions

The following statements should be used: Conceptualization, Mo.K., K.H. and N.H.; methodology, Mo.K., K.H. and N.H.; software, K.H.; validation, Yu.K.; formal analysis, Mo.K., K.H. and N.H.; investigation, Mo.K., K.H. and N.H.; resources, Yo.K., Y.F., Ma.K., N.K., Y.S., T.K., and A.K.; data curation, Mo.K., K.H., N.H. and N.I.; writing—original draft preparation, Mo.K. and K.H.; writing—review and editing, Yu.K., Yo.K., Y.F., Ma.K., N.K., Y.S., T.K., A.K., S.M., and Y.T.; visualization, Mo.K., K.H. and N.H.; supervision, S.M. and Y.T.; project administration, K.H. and Y.T.; funding acquisition, K.H.

Funding

This research was funded by the FUKUDA FOUNDATION FOR MEDICAL TECHNOLOGY 2019.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the National Defense Medical College (protocol code 4772, and date of approval: April 14, 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all patients involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patients to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thamk Editage for providing professional English editing of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- World Health Organization. Title of Site. Available online: https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19/deaths?n=c (accessed on 21 February 2024).

- Sharma, Y.P.; Agstam, S.; Yadav, A.; Gupta, A.; Gupta, A. Cardiovascular manifestations of COVID-19: An evidence-based narrative review. Indian J. Med. Res. 2021, 153, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madjid, M.; Safavi-Naeini, P.; Solomon, S.D.; Vardeny, O. Potential effects of coronaviruses on the cardiovascular system: A review. JAMA Cardiol. 2020, 5, 831–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, R.B.; Botelho, B.G.; Hollanda, J.V.G.; Ferreira, L.V.L.; Junqueira de Andrade, L.Z.; Oei, S.S.M.L.; Mello, T.S.; Muxfeldt, E.S. Covid-19 and the cardiovascular system: A comprehensive review. J. Hum. Hypertens. 2021, 35, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, B.; Brady, W.J.; Bridwell, R.E.; Ramzy, M.; Montrief, T.; Singh, M.; Gottlieb, M. Electrocardiographic manifestations of COVID-19. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2021, 41, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinoshita, T.; Hashimoto, K.; Yoshioka, K.; Miwa, Y.; Yodogawa, K.; Watanabe, E.; Nakamura, K.; Nakagawa, M.; Nakamura, K.; Watanabe, T.; et al. Risk stratification for cardiac mortality using electrocardiographic markers based on 24-hour Holter recordings: The JANIES-SHD study. J. Cardiol. 2020, 75, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashimoto, K.; Amino, M.; Yoshioka, K.; Kasamaki, Y.; Kinoshita, T.; Ikeda, T. Combined evaluation of ambulatory-based late potentials and nonsustained ventricular tachycardia to predict arrhythmic events in patients with previous myocardial infarction: A Japanese noninvasive electrocardiographic risk stratification of sudden cardiac death (JANIES) substudy. Ann. Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2021, 26, e12803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatzoulis, K.A.; Tsiachris, D.; Arsenos, P.; Antoniou, C.K.; Dilaveris, P.; Sideris, S.; Kanoupakis, E.; Simantirakis, E.; Korantzopoulos, P.; Goudevenos, I.; et al. Arrhythmic risk stratification in post-myocardial infarction patients with preserved ejection fraction: The PRESERVE EF study. Eur. Heart J. 2019, 40, 2940–2949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, A.; Malik, M.; Schmidt, G.; Barthel, P.; Bonnemeier, H.; Cygankiewicz, I.; Guzik, P.; Lombardi, F.; Müller, A.; Oto, A.; et al. Heart rate turbulence: Standards of measurement, physiological interpretation, and clinical use: International Society for Holter and Noninvasive Electrophysiology Consensus. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2008, 52, 1353–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshioka, K.; Amino, M.; Zareba, W.; Shima, M.; Matsuzaki, A.; Fujii, T.; Kanda, S.; Deguchi, Y.; Kobayashi, Y.; Ikari, Y.; et al. Identification of high-risk Brugada syndrome patients by combined analysis of late potential and T-wave amplitude variability on ambulatory electrocardiograms. Circ. J. 2013, 77, 610–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, K.; Harada, N.; Kasamaki, Y. Reference values for a novel ambulatory-based frequency domain T-wave alternans in subjects without structural heart disease. J. Cardiol. 2020, 76, 506–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trachanas, K.; Sideris, S.; Arsenos, P.; Tsiachris, D.; Antoniou, C.K.; Dilaveris, P.; Triantafyllou, K.; Xenogiannis, I.; Tsimos, K.; Efremidis, M.; et al. Noninvasive risk factors for the prediction of inducibility on programmed ventricular stimulation in post-myocardial infarction patients with an ejection fraction ≥40% at risk for sudden cardiac arrest: Insights from the PRESERVE-EF study. Ann. Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2022, 27, e12908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakubo, S.; Ozawa, Y.; Saito, S.; Kasamaki, Y.; Komaki, K.; Hanakawa, K.; Sasaki, Y.; Aruga, M.; Miyazawa, I.; Kanda, T.; et al. Normal limits of high-resolution signal-averaged ECG parameters of Japanese adult men and women. J. Electrocardiol. 2000, 33, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.F.; Macfarlane, P.W. New sex dependent normal limits of the signal averaged electrocardiogram. Br. Heart J. 1994, 72, 197–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lui, P.P.; Blet, A.; Smyth, D.; Li, H. The science underlying COVID-19: Implications for the cardiovascular system. Circulation 2020, 142, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, K.; Kinoshita, T.; Miwa, Y.; Amino, M.; Yoshioka, K.; Yodogawa, K.; Nakagawa, M.; Nakamura, K.; Watanabe, E.; Nakamura, K.; et al. Ambulatory electrocardiographic markers predict serious cardiac events in patients with chronic kidney disease: The Japanese Noninvasive Electrocardiographic Risk Stratification of Sudden Cardiac Death in Chronic Kidney Disease (JANIES-CKD) study. Ann. Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2022, 27, e12923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinberg, J.S.; Regan, A.; Sciacca, R.R.; Bigger, J.T. Jr; Fleiss, J.L. Predicting arrhythmic events after acute myocardial infarction using the signal-averaged electrocardiogram. Am. J. Cardiol. 1992, 69, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amit, G.; Rosenbaum, D.S.; Super, D.M.; Costantini, O. Microvolt T-wave alternans and electrophysiologic testing predict distinct arrhythmia substrates: Implications for identifying patients at risk for sudden cardiac death. Heart Rhythm 2010, 7, 763–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, M.A.; Schmidt, G. Heart rate turbulence: A 5-year review. Heart Rhythm 2004, 1, 732–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindgren, K.S.; Mäkikallio, T.H.; Seppänen, T.; Raatikainen, M.J.; Castellanos, A.; Myerburg, R.J.; Huikuri, H.V. Heart rate turbulence after ventricular and atrial premature beats in subjects without structural heart disease. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2003, 14, 447–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tondas, A.E.; Munawar, D.A.; Marcantoni, I.; Liberty, I.A.; Mulawarman, R.; Hadi, M.; Trifitriana, M.; Indrajaya, T.; Yamin, M.; Irfannuddin, I.; et al. Is T-wave alternans a repolarization abnormality marker in COVID-19? An investigation on the potentialities of portable electrocardiogram device. Cardiol. Res. 2023, 14, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mol, M.B.A.; Strous, M.T.A.; van Osch, F.H.M.; Vogelaar, F.J.; Barten, D.G.; Farchi, M.; Foudraine, N.A.; Gidron, Y. Heart-rate-variability (HRV), predicts outcomes in COVID-19. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0258841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duca, Ș.T.; Chetran, A.; Miftode, R.Ș.; Mitu, O.; Costache, A.D.; Nicolae, A.; Iliescu-Halițchi, D.; Halițchi-Iliescu, C.O.; Mitu, F.; Costache, I.I. Myocardial ischemia in patients with COVID-19 infection: Between pathophysiological mechanisms and electrocardiographic findings. Life (Basel) 2022, 12, 1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).