1. Introduction

400 million tons – the average amount of plastic waste (PW) generated worldwide nowadays annually [

1]. Unfortunately, only 9% undergoes mechanical recycling, with the majority of PW being deposited in landfills and subsequently entering the global ocean [

2]. The inadequate handling of these abundant waste materials raises significant concerns regarding the enduring issue of microplastic pollution, stemming from the extremely slow decomposition of PW, thereby contaminating water and soil and adversely impacting various organisms. For example, marine fauna faces severe consequences, including ingestion and entanglement in PW, resulting in increased mortality. In addition to that, plastics containing chlorine, such as polyvinyl chloride (PVC), present additional environmental threats through the release of toxic substances that contaminate the biosphere. [

3]. The well-known problems associated with PW create a need for research aimed at comprehensively understanding and managing the life cycle of plastics, with the ultimate goal of reducing the associated environmental hazards.

Thermochemical conversion processes such as pyrolysis and gasification are one of the possible solutions to address the problems related to PW by upcycling it into valuable products. Many research studies have shown that PW are easily converted into gaseous or liquid energy and chemical products via the aforementioned processes [

4,

5,

6,

7]. When plastic thermally degrades, it releases high contents of volatile matter, consequently, the main products are VOC (volatile organic compounds), while the composition of evolved chemical species mainly depends on selected process conditions. Substantial amounts of volatile matter along with low fixed carbon contents in plastic determine the very limited formation of valuable, multifunctional product – pyrolytic char from such carbon-rich material. Pyrolytic char has gained considerable attention due to its wide range of applications, encompassing energy generation [

8], accumulation [

9], catalyst support [

10], as well as its employment for water [

11] and air purification [

12] when activated, among other uses. The applicability of pyrolysis char across diverse fields, including but not limited to energy, underscores its potential for substantial demand in the future, addressing environmental concerns and the ever-increasing need for energy resources.

Carbon materials can be obtained from plastics via different techniques depending on the type of solid product desired, e.g. carbon black, carbon nanotubes (CNTs), char, etc. Carbon black can be produced through the soot formation at high temperatures (>1000 °C) which is driven by the secondary reactions – cyclization and aromatization which occur in the gas-phase VOC. An example of such a technique application on the conversion of plastic materials is presented by H. Jiang et al. [

13], who have succeeded in producing 47.9–56.7% yield of carbon black from waste tyres via pyrolysis at 1300 °C. While, CNTs from plastics are majorly produced through catalytic processing, in which VOC emitted during pyrolysis undergo chemical vapour deposition reactions on the surface of the transition metals catalyst. For instance, J. C. Acomb et al. [

14] have described the influence of different transition metals on the yields of filamentous carbon and H2 gas and concluded that Fe catalyst performance for LDPE conversion is the best – CNTs and H2 were the main products with 26% and 50%wt. yield respectively. The production of pyrolytic char from plastic material is another available pathway, which is advantageous in terms of multifunctionality this product serves, but also due to the milder process conditions – lower temperature and avoidance of the need for a catalyst. Nevertheless, the constraint for this path is the absence or very low content of fixed carbon in plastics, thus additional treatment is required to carbonise such material into char.

To increase the fixed carbon content in polymers of liner structure, specific pre-treatment is applied, which includes thermal oxidation or chemical stabilization after which an intermediate cyclic structure is built. Both of these techniques cover the oxidation of a material followed by cross-linking reactions, which determine the higher stability of a polymer. The difference between these stabilization approaches is that during thermal oxidation, air acts as an oxidising agent at a high temperature that usually is equal to 200–300 °C [

15], whereas the most common chemical stabilization technique is sulfonation in which strong oxidisers are employed, such as sulfuric acid, fuming sulphuric acid or chlorosulphonic acid [

16]. The first technique has been well-known and applied industrially since the early 1960s in carbon fiber production from polyacrylonitrile (PAN) fibers, in which thermal oxidation stabilisation (TOS) is considered a crucial step to achieve successful carbonisation [

17]. The stabilizing effect of this approach on a plastic material was confirmed by D. Choi et al. [

15,

18]. Authors have revealed that 330 °C stabilization temperature for 10 min is sufficient to produce graphitic carbon from PE microfilms at 1200 °C pyrolysis temperature. The same conditions of TOS were reported decent to convert PE, PP and PET into char by E. M. Iwanek & D. W. Kirk [

19] by obtaining a maximum 33–55 % yield of char. In comparison, sulfonation as a sufficient stabilisation method for plastic materials was first reported by A. Postema et al. [

20], who showed that this type of stabilisation requires lower temperatures, although longer conditioning along with a high concentration of chemical stabilisation agent. Investigations covering this technique [

16,

21,

22,

23] have published that up to 50 % yield of plastic-derived char can be produced by the pre-treatment of up to 12 h at 120–170 °C by submerging fibrous plastics into highly concentrated sulfonating agents.

In this study, several of the main PW were selected –PE as the most extensively utilized plastic worldwide [

24] which therefore contributes to plastic waste generation substantially, and PVC, which serves some additional problems such as the formation of dioxins and other toxic substances during combustion [

25]. Complicated recycling due to the high content of plasticizers added is another disadvantageous feature of PVC plastic which triggers the need to research alternative approaches for these waste management. The aim was set to evaluate the potential of the thermochemical conversion of these PW to multifunctional char by increasing the fixed carbon proportion through stabilisation. Previous research has mainly concentrated on liner, halogen-free plastic carbonisation by applying chemical or thermal oxidation stabilisation techniques. This work, on the other hand, focused on comparing the influence of the both most common techniques influence on the physical and chemical properties of char derived from PE and chlorine-rich PVC together with the assessment of their surface properties and eventually their potential to be applied as a catalyst support material.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental design

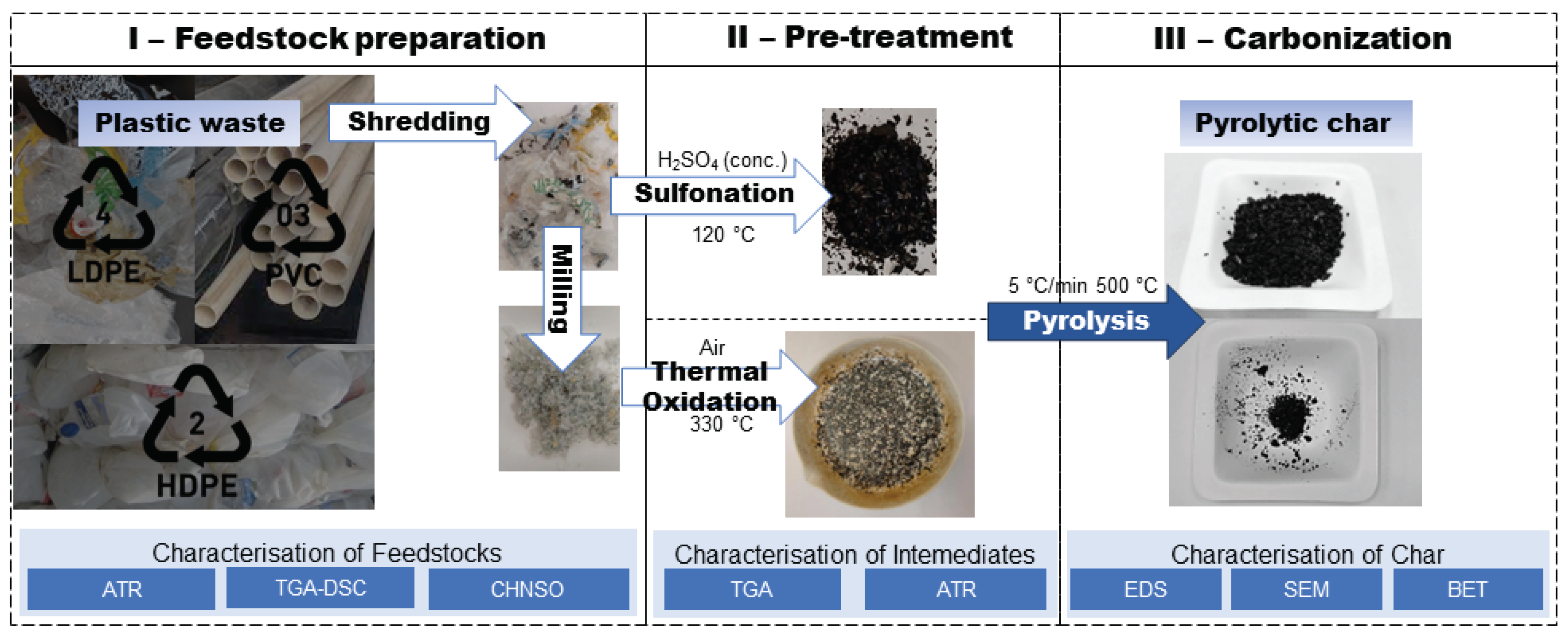

Figure 1 illustrates the sequence of the experiments implemented in this research. The experimental part was divided into three stages: I – PW separation, shredding/ milling followed by compositional and thermal characterisation of prepared feedstock, II – application of chemical and thermal oxidation stabilisation pretreatment to increase fixed carbon content in PW, III – carbonisation experiments of treated PW in a fixed bed reactor and subsequent characterisation and comparison of plastic-derived char. The stages of the study and the conditions applied are presented in detail in the following sections.

2.2. Feedstock collection and preparation

Plastic wastes investigated in this research were collected from different sources according to plastic recycling symbols. Low-density polyethylene (LDPE) was collected and separated from public recycle bins, whereas high-density polyethylene (HDPE) wastes were obtained from local producers of plastic products and PVC samples were from collection point of old PVC pipes. PW were separately shredded by FilaMaker Textile shredder (blades of 15 mm width) and particles of approximately 1×1 cm dimensions were obtained. Shredded plastics were cryo-milled into fine powder (

Figure 1) by FRITSCH analysette 3 pulverisette 0 applying the amplitude of the grinding ball vibrations to 1.5–2.0 mm. Plastic samples were characterised by proximate and ultimate analyses following ASTM D7582-15 and ISO 17247:2020 international standard methods respectively (

Table 1 and

Table 3).

Generally, among analyzed plastic wastes, LDPE and HDPE have high contents of carbon and hydrogen with low amounts of oxygen, originating from plasticizers added, which mainly are ester compounds [

26]. While in PVC dominant element is chlorine and carbon compiles only up to 30% of this waste material.

2.3. Stabilisation pre-treatment of PW

To produce char from plastic material, the stabilization must be applied prior to carbonization. As explained in the introduction section, the inner structure of the aliphatic polymer (plastic) is reinforced by cross-linking between polymeric chains through the stabilization treatment, thus increasing the thermal stability of plastic. Ground PW were separately stabilised by sulfonation and thermal oxidation techniques to compare the influence on the formation of char and its properties.

2.3.1. Sulfonation

To select optimum conditions for the treatment and reach a high degree of sulfonation, shredded LDPE, HDPE and PVC plastic samples were chemically stabilized in accordance with previously conducted research [

16,

20,

21,

22,

23,

27,

28,

29]. Samples were separately submerged in sulfuric acid 96% p.a., Lach-Ner, Ltd., and heated for 20 h at 120 ± 1 °C in a silicone oil bath. After the treatment, the residual acid from the filtered samples was removed by washing with distilled water until the neutral pH. Finally, drying at 80 °C for 8 h was accomplished and sulfonated plastics were considered to be ready for the carbonization.

2.3.2. Thermal oxidation stabilisation

In parallel, ball-milled PW samples underwent thermal oxidation treatment in a muffle furnace following the method approved by D. Choi et al. [

15,

18]. The temperature ramping rate was set at 5 °C/min, and the samples were maintained at 330 °C for 30 minutes in the air-rich ambient. Subsequently, the stabilized samples were carbonized as described in the section below.

2.4. Carbonisation procedure

Plastic samples were carbonized in a vertical, fixed-bed tube reactor made of steel (5 cm inner diameter and 40 cm length). The optimum pyrolysis temperature of 500 °C was selected for the process with the retention of 2 h to reach sufficient carbonization [

30]. Slow pyrolysis was conducted by elevating the temperature at a 5 °C/min rate under the N2 gas flow of 0.5 l/min.

2.5. Analysis methods

2.5.1. Simultaneous thermogravimetric – differential scanning calorimetry analysis (TGA-DSC)

TGA of pre-treated and raw plastics was performed to gain an understanding of differences in the pattern of decomposition during the pyrolysis process. The equipment used for this part was a NETZSCH STA 449 F3 Jupiter analyser with a SiC furnace. Samples of 10 ± 2 mg weight were heated in Al2O3 crucibles from 40 to 900 °C temperature at a heating rate of 35 °C/min. An inert ambient was established by supplying N2 gas in the furnace with a constant flow rate of 60 ml/min. Obtained thermograms were processed by NETZSCH Proteus® software version 8.0.3 and the first derivative of TGA curves was calculated to determine the rate of the weight changes during the decomposition. Ball-milled plastics were analysed by TGA-DSC simultaneous analysis to determine precisely the temperatures of thermal processes occurring under heating in a nitrogen environment. Analysis was carried out following the ISO 11358 standard method.

2.5.2. Attenuated total reflectance spectroscopy(ATR-FTIR)

ATR-FTIR was applied to establish chemical changes in polymers occurred during the pre-treatment triggered partial oxidation. The FTIR spectra of plastic samples were measured using ALPHA series Platinum spectrometer. The total internal reflection of IR beams was measured in a wavenumber range of 600–4000 cm−1 with a scan resolution of 4 cm-1, automatically calculating average values of reflected IR beams from the data of 32 scans for each spectrum.

2.5.3. Brunauer–Emmett–Teller analysis (BET)

The specific surface area of plastic-derived carbon was determined by employing Quantachrome Autosorb-iQ-KR/MP automated gas sorption analyser. Analysis of specific surface area was based on adsorption-desorption isotherms of N2 gases at liquid nitrogen temperature (–196°C) by calculating the particular value with the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller equation. ASiQwin (Version 2.0) program developed by Quantachrome Instrument 24 was used for the accomplishment of calculations.

2.5.4. Scanning electron microscopy with an energy-dispersive spectroscopy (SEM-EDS)

SEM-EDS was utilized to examine the plastic-derived char morphology and elemental composition. Analysis was performed on Zeiss EVO MA10 scanning electron microscope by applying 20 kV voltage under vacuum conditions. The constituent elements were determined by the Bruker AXSX Flash 6/10 detector at an overall accuracy of about 1% and detection sensitivity.

3. Results

3.1. Thermal analysis

3.1.1. Simultaneous TGA-DSC analysis of the raw plastics

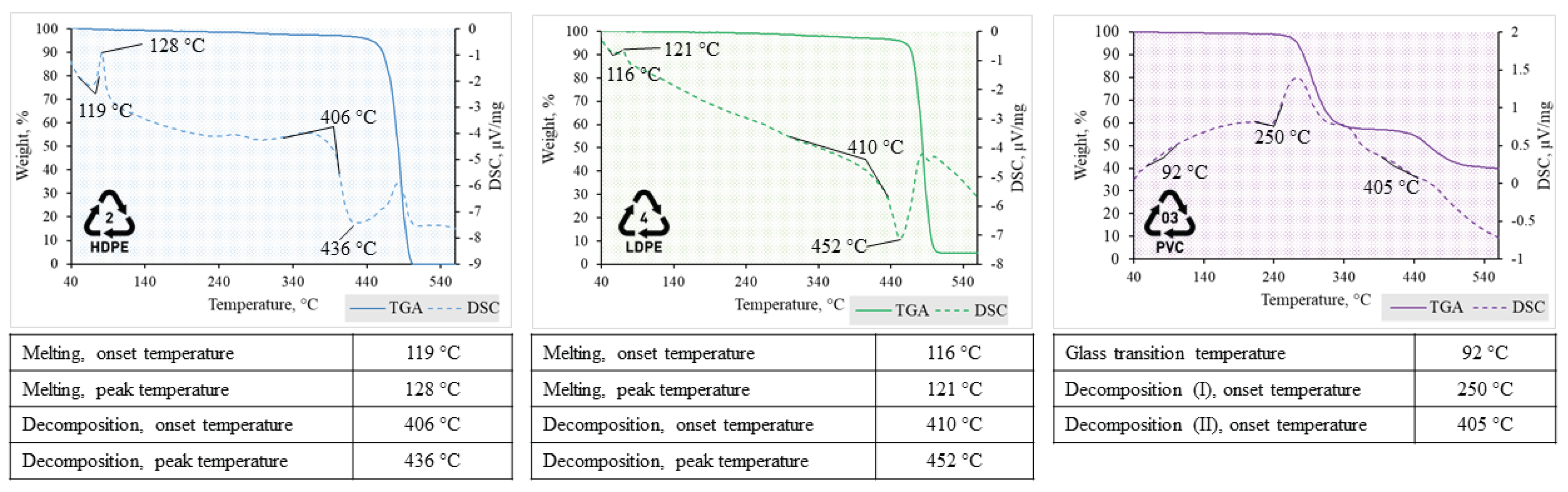

Figure 2 illustrates the TGA-DSC thermograms and the main temperatures of characteristic phase transitions observed under heating of ball-milled PW.

Both types of PE undergo similar transitions at corresponding temperatures, while another polymeric waste – PVC consequently had dissimilar peaks of ongoing thermal processes. The first transition of PE (low and high density) is an endothermal process of semicrystalline polymeric structure turning into amorphous state, which is determined from the first endothermic peak in the thermogram at 121 – 128 °C temperature. Upon further heating PE thermally degrades when the decomposition onset temperature is reached (406 – 410 °C). At this temperature point breakdown of liquid phase polymer into gaseous state decomposition products is triggered [

31]. PVC, on the other hand, firstly underwent glass transition and then melted. PVC polymer has polarity due to the presence of Cl atoms in its chemical composition, which determines stronger intermolecular forces compared to non-polar PE. Consequently, polymer structure becomes amorphous, but stiff due to interchain attractions and polymer has glassy state at 92 °C [

32]. Another important difference is multistep-degradation of PVC compared to that of PE. Decomposition onset was determined by exothermal peak, which depicts heat release due to the breakage of chemical bonds [

33]. Degradation patterns during pyrolysis is described more detailed in the next section.

3.1.2. TGA-DTG analysis of raw and pre-treated plastics

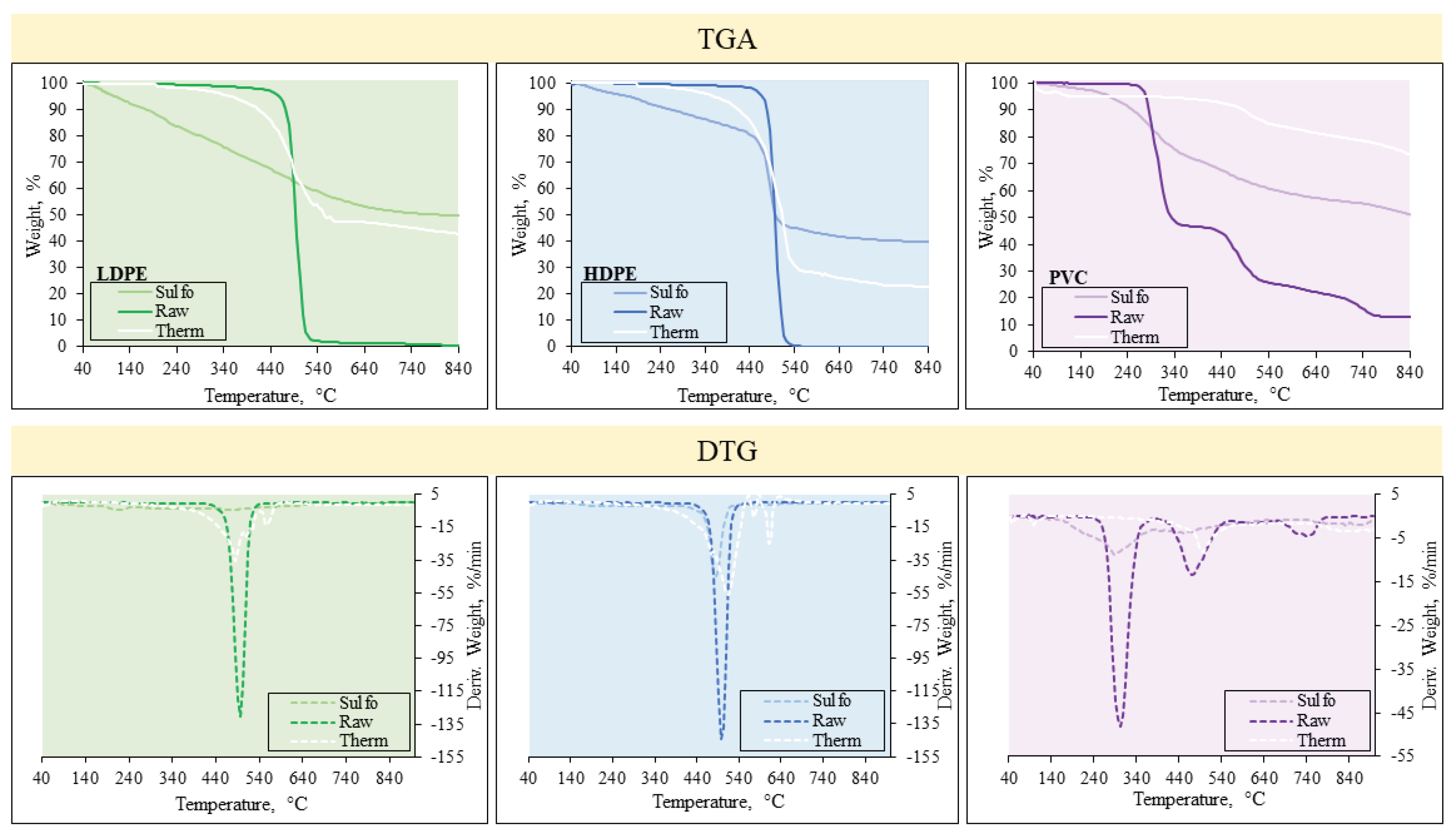

Changes in weight and major decomposition points of raw and pre-treated (stabilized) precursors during pyrolysis were determined by fulfilling TGA. The first derivative of TGA curve – DTG – was calculated which depicts the rate of weight changes. TGA-DTG curves are presented in

Figure 3.

Both LDPE and HDPE feedstock degraded in one sharp step with the degradation onset at around 408 °C within a single DTG peak at 497 °C which is characteristic to polyethylene. Whereas, the pre-treated samples had a different degradation pattern. It was determined that the decomposition of the stabilized PE occurred in a considerably lower rates contrary to the untreated samples. Together with that, residual mass, which corresponds to char rates, increased significantly when the stabilization was applied. B. Xie et al. [

21] have revealed that sulfonated linear LDPE undergoes a matching thermal decomposition pattern with a residual mass of >40 % after pyrolysis. A very similar decomposition trend was also confirmed on thermally stabilized LDPE in previous research [

15].

PVC had a completely different thermal decomposition pattern compared to PE samples. The decomposition during pyrolysis is eventuated in three distinct stages. The first degradation stage occurred when the temperature was elevated from 253 °C to 411 °C which corresponds to the release of chlorine via the formation of HCl [

34]. The second stage occurred by increasing the temperature to approximately 660 °C with the DTG peak at 478 °C which was particularly close to those of PE samples and corresponded to the degradation of the olefin structure in PVC polymer. The last stage until 800 °C indicated the carbonisation of a sample. Similarly to the case of PE, PVC modified via stabilization had lower rates of degradation and the formation of residue was substantially enhanced Respective results were obtained by J. T. S. Allan et al. [

35], who showed that the highest yield of char of approximately 40% was formed from the PVC sulfonated for 24 h. Overall, the results of TGA-DTG analysis provide a clear evidence that both stabilisation pre-treatments have a major influence on the formation of char from selected PW with a significant impact on their decomposition pattern.

3.2. ATR spectroscopy analysis

Chemical changes in the surface of pre-treated and raw plastic samples were determined using ATR spectroscopy (

Figure 4). The major effect of both treatments was the decrease in the intensity of IR absorbance peaks characteristic to analysed polymeric wastes along with the development of new chemical bonds.

Functional groups and bonds identified via ATR-FTIR spectroscopy of raw and pre-treated precursors of char are displayed in

Table 2.

Oxidation reactions during both stabilization procedures caused a decrease in the intensity of peaks associated with olefinic C-H stretching vibrations [

34] due to the consumption of double bonds. In addition to that, the attachment of new functional groups such as hydroxyl and the formation new of chemical bonds – C=C was determined in pre-treated PVC due to dechlorination upon exposure to heat and oxygen, leading to the removal of hydrogen chloride (HCl) molecules. Furthermore, during the sulfonation pre-treatment sulfuric acid has introduced sulfonic acid (–SO

3H) groups onto the polymer backbone. Analogous results were demonstrated by J. W. Kim & J. S. Lee [

36] – the intensity of –SO

3H vibration peaks has increased together with a substantial decrease in C-H stretching bonds in LDPE fibers exposed to concentrated H

2SO

4 at 140 °C for the longest exposure time.

3.3. Proximate analysis and char yields

As was seen in the TGA-DTG analysis, both stabilization techniques had an important influence on the formation of carbonaceous residues through pyrolysis. In

Table 3. the yields of char in correlation with fixed carbon content in precursors are presented. Electrophilic substitution of hydrogen to oxygen-containing groups which is followed by hydride ion loss causes conjugation of polymer chains via cross-linking [

27], thus fixed carbon (FC) content is increased. The cross-linked polymer has higher stability under heating – devolatilization is diminished and thus carbonization progresses successfully [

37]. According to the obtained results, the sulfonation stabilization technique had higher efficiency on all analyzed PW samples, due to the major influence on the FC contents.

Table 3.

Proximate analysis results and char yields from raw and treated plastics, here: M corresponds to % wt. of moisture, VM – volatile matter, FC – fixed carbon, A – ash content.

Table 3.

Proximate analysis results and char yields from raw and treated plastics, here: M corresponds to % wt. of moisture, VM – volatile matter, FC – fixed carbon, A – ash content.

| LDPE |

| |

M |

VM |

FC |

A |

Char yield (%) |

| Raw |

0 |

99.62 |

0.16 |

0.22 |

3.03 |

| Sulfo |

5.27 |

44.87 |

37.93 |

11.93 |

56.64 |

| Therm |

0.84 |

55.85 |

30.96 |

12.35 |

17.96 |

| HDPE |

| |

M |

VM |

FC |

A |

Char yield (%) |

| Raw |

0 |

99.44 |

0.56 |

0 |

1.32 |

| Sulfo |

3.66 |

48.51 |

42.16 |

5.67 |

49.12 |

| Therm |

0.18 |

73.4 |

25.7 |

0.72 |

10.06 |

| PVC |

| |

M |

VM |

FC |

A |

Char yield (%) |

| Raw |

0 |

83.48 |

14.52 |

2 |

13.01 |

| Sulfo |

1.37 |

52.49 |

27.6 |

18.54 |

55.23 |

| Therm |

3.31 |

35.91 |

24.76 |

36.02 |

48.09 |

3.4. Surface properties and composition of plastic-derived char

3.4.1. Surface morphology

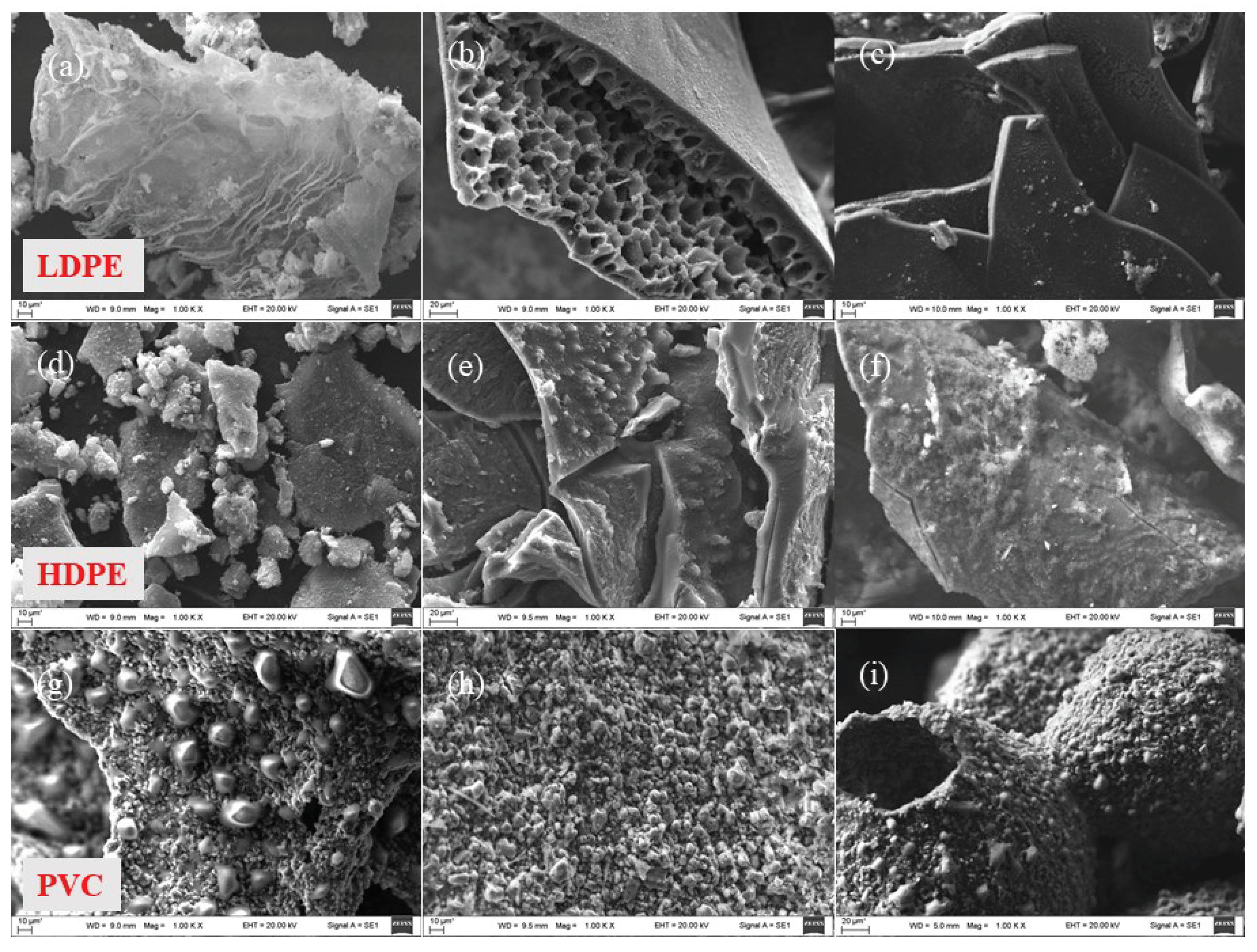

The surface morphology analysis of carbonaceous residues obtained from the raw and pre-treated plastics was performed by employing SEM and BET analyses. Obtained images (

Figure 5) have illustrated that the treatments have a considerable influence on the surface appearance, the particles' size and the char's structure.

Both sulfonation and thermal oxidation pre-treatments applied on PE samples have caused the reinforcement of the plastic surface and the formation of rigid and large char particles. Treatments reduced soot formation from PE and charring progressed during slow pyrolysis – carbon particles maintained a larger size compared with that produced from untreated PE. The outer layer of char obtained from sulfonated LDPE was flat, while in the inner space, a highly porous structure formed. Such influence on char from sulfonated HDPE was not defined, while thermal oxidation treatment has not triggered a similar effect on any sample. Cross-linking reactions have caused shrinkage of plastic particles' surface, following that, the pyrolysis process triggered inner polymeric matter to boil along with the formation of pores. Additionally, it was determined the outer surface of sulfonated polyethylene-derived carbons had cracks which occurred due to the outer layer shrinkage. This effect was also highlighted in previous research [

27,

36].

The surface morphology of PVC-derived carbon was distinct compared to previously described PE samples. Char produced from untreated PVC distinguished itself by >100 mµ cavities formed during carbonisation. Moreover, the surface of PVC-char was covered with small droplets – condensed tars. This suggests, that a higher carbonisation temperature should be selected for this polymer. The outer surface, similarly to sulfonated PE-char samples, was flat and rigid which was influenced by both treatments.

The significant influence of the applied pre-treatments was determined on the specific surface area (SSA) of produced chars by BET analysis (

Table 4). Sulfonation treatment has caused the biggest increase in the SSA of char compared to that of raw or thermally treated precursors. The greatest effect appeared on the char obtained from sulfonated LDPE of BET value equal to 334.5 m

2/g comparable to that of γ-Al

2O

3 (Alfa Aesar), which is the most widely used catalyst support material employed in various chemical processing reactions [

38]. This further suggests the applicability perspective for this particular case in catalytic processing.

PVC-char, compared to PE-char maintained the lowest BET value. Small droplets of pyrolysis tars visible on the surface of PVC-char (

Figure 5g–i) have blocked the pores, thus SSA was diminished. The increase of specific surface area in all cases suggests that during the pre-treatments, especially when samples were exposed to concentrated sulphuric acid, the surface of a polymer was affected by the oxidising effect of the oxidizing agent and therefore cracks have formed on the surface that directly affected the surface area [

39].

3.4.2. Elemental composition

An energy-dispersive X-ray Spectrometer (EDS) was employed to determine the elemental composition of derived carbonaceous matter (Table . Naturally, the major component detected was elemental carbon, which percentage amount has increased significantly in char obtained from stabilized plastic samples compared to untreated ones. This reveals the purity of produced char. Oxygen was the second element in terms of abundance in all samples, originating from different inorganic additives and catalytic compounds applied in plastic production. Chlorine as a natural PVC plastics constituent was determined in all PVC-derived char samples, although char produced from polymers free of Cl in their chemical structure also contained trace amounts of it due to the usage of Cl compounds as catalysts for the polymerization reactions. The presence of Ca and Ti elements also originated from catalysts used in the plastic production process [

40]. Barium and silicon originated in LDPE-derived char from the filling material used to produce plastics – BaSO

4 and Si

2O respectively [

41,

42]. Overall, the char of the greatest purity was obtained from raw and pretreated HDPE and pretreated LDPE plastic waste.

Table 5.

EDS analysis results of plastic-derived char (s – sulfonated, t – thermally oxidized) (%wt.).

Table 5.

EDS analysis results of plastic-derived char (s – sulfonated, t – thermally oxidized) (%wt.).

| |

LDPE |

LDPE s

|

LDPE t

|

HDPE |

HDPE s

|

HDPE t

|

PVC |

PVC s

|

PVC t

|

| C |

27.97 |

86.03 |

80.78 |

90.28 |

90.53 |

92.92 |

53.04 |

73.65 |

41.33 |

| Cl |

0.12 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.08 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

8.43 |

1.47 |

7.50 |

| O |

45.95 |

12.91 |

16.01 |

7.84 |

8.85 |

6.90 |

27.94 |

18.34 |

38.51 |

| S |

8.47 |

0.74 |

0.76 |

0.56 |

0.37 |

0.01 |

0.08 |

2.02 |

0.10 |

| Ca |

0.30 |

0.04 |

0.19 |

0.27 |

0.03 |

0.11 |

9.36 |

3.44 |

11.42 |

| Ba |

14.77 |

0.00 |

0.88 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

| Ti |

0.00 |

0.28 |

1.14 |

0.12 |

0.04 |

0.02 |

1.11 |

1.01 |

1.04 |

| Si |

2.42 |

0.00 |

0.23 |

0.85 |

0.18 |

0.04 |

0.04 |

0.06 |

0.10 |

| Total |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

4. Discussion

The results of this study highlight the effectiveness of sulfonation and thermal oxidation stabilization techniques in enhancing the fixed carbon content of waste polyethylene and polyvinyl chloride (PVC) for the production of pyrolytic char. Sulfonation treatment exhibited superior performance, resulting in higher yields of pyrolytic char formation compared to thermal oxidation. Moreover, sulfonation positively influenced the surface properties of the produced char, making it comparable to traditional catalyst support materials such as Al2O3. Specifically, the specific surface area of char obtained from sulfonated low-density polyethylene (LDPE) exceeded 300 m2/g, indicating its potential as a catalyst support material.

On the other hand, thermal oxidation stabilization increased the fixed carbon content in plastic, `but with a significant portion of mass being devolatilized during treatment, resulting in a lower yields of pyrolytic char. Additionally, this method had negligible impact on the surface properties of the produced char. However, the approach is more environmentaly friendly compared to sulfonation stabilization, which requires the use of concentrated sulfuric acid (hazardous chemical wastes).

Overall, both stabilization methods demonstrated effectiveness in enhancing the fixed carbon content of plastic waste, contributing to the potential utilization of plastic-derived char in various industrial applications and in particular as catalyst support materials. The findings suggest sulfonation as a more advantageous technique due to its higher char yield and beneficial effects on char surface properties. This underscores the importance of exploring innovative approaches to plastic waste management, ultimately contributing to the development of a circular economy and sustainable resource utilization. Further research could focus on optimizing the conditions of the stabilization step and exploring additional applications of plastic-derived char.

5. Conclusions

This investigation suggests a feasible route for plastic waste conversion to solid carbon of wide application potential. It was determined that the chemical stabilisation by employing hot sulfuric acid for a prolonged time has a significant impact on yields of carbon and is greater compared to the thermal oxidation stabilization technique. Another advantage was the improved surface properties of plastic-derived char determined by sulfonation treatment. The stabilization has caused cross-linking of investigated plastic waste by increasing fixed carbon content and pyrolytic char yields consequently. The findings reveal that polyethylene and polyvinylchloride waste can be successfully converted to high yields of solid carbon with upgraded surface properties and has potential to be employed in catalytic processes as catalyst support materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I. Kiminaitė and N. Striūgas; methodology, I. Kiminaitė and N. Striūgas.; investigation, I. Kiminaitė, K. Zakarauskas and A. Baltušnikas; data curation, N. Striūgas; writing—original draft preparation, I. Kiminaitė; writing—review and editing, I. Kiminaitė and N. Striūgas; visualization, I. Kiminaitė and A. Baltušnikas; supervision, N. Striūgas; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We extend our sincere gratitude to our colleague, R. Kriūkiene, for her contribution to this research and dedication in carrying out SEM-EDS analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- UN Environment Programme Beat Plastic Pollution. Available online: https://www.unep.org/interactives/beat-plastic-pollution/#:~:text=Today%2C we produce about 400,of plastic waste every year (accessed on 20 March 2023).

- OECD Global Plastics Outlook Database Plastic Pollution Is Growing Relentlessly as Waste Management and Recycling Fall Short, Says OECD. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/environment/plastic-pollution-is-growing-relentlessly-as-waste-management-and-recycling-fall-short.htm#:~:text=22%2F02%2F2022 - The,to a new OECD report (accessed on 20 March 2023).

- Okunola, A.A.; Kehinde, I.O.; Oluwaseun, A.; Olufiropo, E.A. Public and Environmental Health Effects of Plastic Wastes Disposal: A Review. J. Toxicol. Risk Assess. 2019, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.W.; Kim, Y.T.; Tsang, Y.F.; Lee, J. Sustainable Ethylene Production: Recovery from Plastic Waste via Thermochemical Processes. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 903, 166789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baena-González, J.; Santamaria-Echart, A.; Aguirre, J.L.; González, S. Chemical Recycling of Plastic Waste: Bitumen, Solvents, and Polystyrene from Pyrolysis Oil. Waste Manag. 2020, 118, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, B.P.S.; Almeida, D.; Marques, M. de F. V.; Henriques, C.A. Petrochemical Feedstock from Pyrolysis of Waste Polyethylene and Polypropylene Using Different Catalysts. Fuel 2018, 215, 515–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiminaitė, I.; González-Arias, J.; Striūgas, N.; Eimontas, J.; Seemann, M. Syngas Production from Protective Face Masks through Pyrolysis/Steam Gasification. Energies 2023, 16, 5417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaijak, P.; Sato, C.; Lertworapreecha, M.; Sukkasem, C.; Boonsawang, P.; Paucar, N. Potential of Biochar-Anode in a Ceramic-Separator Microbial Fuel Cell (CMFC) with a Laccase-Based Air Cathode. Polish J. Environ. Stud. 2019, 29, 499–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Zhang, Y.; Ouyang, Q.; Hao, J.; Huang, X.; Li, J.; Chen, X. An Investigation of the Structure and Electrochemical Performance of N-Doped Carbon Anodes Derived from Poly (Acrylonitrile-Co-Itaconic Acid) /Pyrolytic Lignin/Zinc Borate. Electrochim. Acta 2022, 429, 141018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seng-eiad, S.; Jitkarnka, S. Untreated and HNO3-Treated Pyrolysis Char as Catalysts for Pyrolysis of Waste Tire: In-Depth Analysis of Tire-Derived Products and Char Characterization. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2016, 122, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopu, C.; Gao, L.; Volpe, M.; Fiori, L.; Goldfarb, J.L. Valorizing Municipal Solid Waste: Waste to Energy and Activated Carbons for Water Treatment via Pyrolysis. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2018, 133, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, H.; Wang, S.; Jeong, H.-R. TMA and H 2 S Gas Removals Using Metal Loaded on Rice Husk Activated Carbon for Indoor Air Purification. Fuel 2018, 213, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Shao, J.; Hu, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Cheng, W.; Zhang, J.; Fan, T.; Yu, J.; Yang, H.; Zhang, X.; et al. Carbon Black Production Characteristics and Mechanisms from Pyrolysis of Rubbers. Fuel Process. Technol. 2024, 253, 108011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acomb, J.C.; Wu, C.; Williams, P.T. The Use of Different Metal Catalysts for the Simultaneous Production of Carbon Nanotubes and Hydrogen from Pyrolysis of Plastic Feedstocks. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2016, 180, 497–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, D.; Jang, D.; Joh, H.-I.; Reichmanis, E.; Lee, S. High Performance Graphitic Carbon from Waste Polyethylene: Thermal Oxidation as a Stabilization Pathway Revisited. Chem. Mater. 2017, 29, 9518–9527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wortberg, G.; De Palmenaer, A.; Beckers, M.; Seide, G.; Gries, T. Polyethylene-Based Carbon Fibers by the Use of Sulphonation for Stabilization. Fibers 2015, 3, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Wang, C.; Bai, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Liu, H. Combined Effect of Processing Parameters on Thermal Stabilization of PAN Fibers. Polym. Bull. 2006, 57, 525–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, D.; Yeo, J.-S.; Joh, H.-I.; Lee, S. Carbon Nanosheet from Polyethylene Thin Film as a Transparent Conducting Film: “Upcycling” of Waste to Organic Photovoltaics Application. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 12463–12470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwanek (nee Wilczkowska), E.M.; Kirk, D.W. Application of Slow Pyrolysis to Convert Waste Plastics from a Compost-Reject Stream into Py-Char. Energies 2022, 15, 3072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postema, A.R.; De Groot, H.; Pennings, A.J. Amorphous Carbon Fibres from Linear Low Density Polyethylene; 1990; Volume 25. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, B.; Hong, L.; Chen, P.; Zhu, B. Effect of Sulfonation with Concentrated Sulfuric Acid on the Composition and Carbonizability of LLDPE Fibers. Polym. Bull. 2016, 73, 891–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, M.; Güillen Obando, A.; Emery, J.; Qiang, Z. Multifunctional Carbon Fibers from Chemical Upcycling of Mask Waste. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 12278–12287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.-W.; Lee, H.-M.; Kim, B.S.; Hwang, S.-H.; Kwac, L.-K.; An, K.-H.; Kim, B.-J. Preparation and Thermal Properties of Polyethylene-Based Carbonized Fibers. Carbon Lett. 2015, 16, 62–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plastic Oceans The Basics On 7 Common Types of Plastic. Available online: https://plasticoceans.org/7-types-of-plastic/#:~:text=Collectively%2C Polyethylene is the most,pipes and other building materials (accessed on 4 December 2023).

- Zhang, M.; Buekens, A.; Jiang, X.; Li, X. Dioxins and Polyvinylchloride in Combustion and Fires. Waste Manag. Res. J. a Sustain. Circ. Econ. 2015, 33, 630–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niaounakis, M. Manufacture of Films/Laminates. In Biopolymers: Processing and Products; Elsevier, 2015; pp. 361–386. [Google Scholar]

- Kazimi, M.R.; Shah, T.; Shima Binti Jamari, S.; Ahmed, I.; Ku Mohammad Faizal, C. Sulfonation of Low-Density Polyethylene and Its Impact on Polymer Properties. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2014, 54, 2522–2530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartel, M.T.; Sych, N.V.; Tsyba, M.M.; Strelko, V.V. Preparation of Porous Carbons by Chemical Activation of Polyethyleneterephthalate. Carbon N. Y. 2006, 44, 1019–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, B.E.; Patton, J.; Hukkanen, E.; Behr, M.; Lin, J.-C.; Beyer, S.; Zhang, Y.; Brehm, L.; Haskins, B.; Bell, B.; et al. The Chemical Transformation of Hydrocarbons to Carbon Using SO3 Sources. Carbon N. Y. 2015, 94, 465–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harussani, M.M.; Sapuan, S.M.; Rashid, U.; Khalina, A.; Ilyas, R.A. Pyrolysis of Polypropylene Plastic Waste into Carbonaceous Char: Priority of Plastic Waste Management amidst COVID-19 Pandemic. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 803, 149911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiran, N.; Ekinci, E.; Snape, C.E. Recycling of Plastic Wastes via Pyrolysis. Fuel Energy Abstr. 2000, 41, 417–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agapov, A.L.; Wang, Y.; Kunal, K.; Robertson, C.G.; Sokolov, A.P. Effect of Polar Interactions on Polymer Dynamics. Macromolecules 2012, 45, 8430–8437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snegirev, A.Y.; Talalov, V.A.; Stepanov, V.V.; Korobeinichev, O.P.; Gerasimov, I.E.; Shmakov, A.G. Autocatalysis in Thermal Decomposition of Polymers. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2017, 137, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.M.; Jiang, X.G.; Yan, J.H.; Chi, Y.; Cen, K.F. TG-FTIR Analysis of PVC Thermal Degradation and HCl Removal. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2008, 82, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, J.T.S.; Prest, L.E.; Easton, E.B. The Sulfonation of Polyvinyl Chloride: Synthesis and Characterization for Proton Conducting Membrane Applications. J. Memb. Sci. 2015, 489, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.W.; Lee, J.S. Preparation of Carbon Fibers from Linear Low Density Polyethylene. Carbon N. Y. 2015, 94, 524–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kim, J.; Ku, B.-C.; Kim, J.; Joh, H.-I. Structural Evolution of Polyacrylonitrile Fibers in Stabilization and Carbonization. Adv. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2012, 02, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prins, R. On the Structure of γ-Al2O3. J. Catal. 2020, 392, 336–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon Cameron, G.; Main, B.R. The Action of Concentrated Sulphuric Acid on Polyethylene and Polypropylene: Part 2—Effects on the Polymer Surface. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 1985, 11, 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turku, I.; Kärki, T.; Rinne, K.; Puurtinen, A. Characterization of Plastic Blends Made from Mixed Plastics Waste of Different Sources. Waste Manag. Res. J. a Sustain. Circ. Econ. 2017, 35, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, A.; Filella, M. The Influence of Additives on the Fate of Plastics in the Marine Environment, Exemplified with Barium Sulphate. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 158, 111352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siraj, S.; Al-Marzouqi, A.H.; Iqbal, M.Z.; Ahmed, W. Impact of Micro Silica Filler Particle Size on Mechanical Properties of Polymeric Based Composite Material. Polymers 2022, 14, 4830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).