Introduction

Autoimmunity occurs when a reduction in regulatory T lymphocytes causes a breakdown of immune tolerance toward self-antigens.[

1,

2,

3] Hashimoto’s thyroiditis (HT) is an autoimmune thyroid disorder characterized by the presence of anti-thyroglobulin (Ab-TG) and/or anti-thyroid peroxidase (Ab-TPO) autoantibodies that cause a cellular and humoral immune response that destroys the thyroid gland. The resulting tissue fibrosis and gland atrophy lead to hypothyroidism in 20–30% of patients and are the most common causes of hypothyroidism in developed countries.[

4,

5] An early

post-mortem study that analyzed patients with no evidence of thyroid disease during their lifetime revealed that 27% of adult women and 7% of men had thyroiditis, suggesting that the prevalence of autoimmune thyroiditis is probably underestimated.[

6,

7] The reported incidence of HT is higher in women, in iodine-deficient areas, and in older patients.[

5,

8] Detecting the presence of autoantibodies in peripheral blood enables the HT diagnosis; however, diagnosis can be challenging, and delays are not uncommon.[

8] Ab-TPO antibody titer can also predict the development of overt thyroid dysfunction (in which thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) and thyroid hormone abnormalities are present). In contrast, the Ab-TG sensitivity is lower (30–50%).[

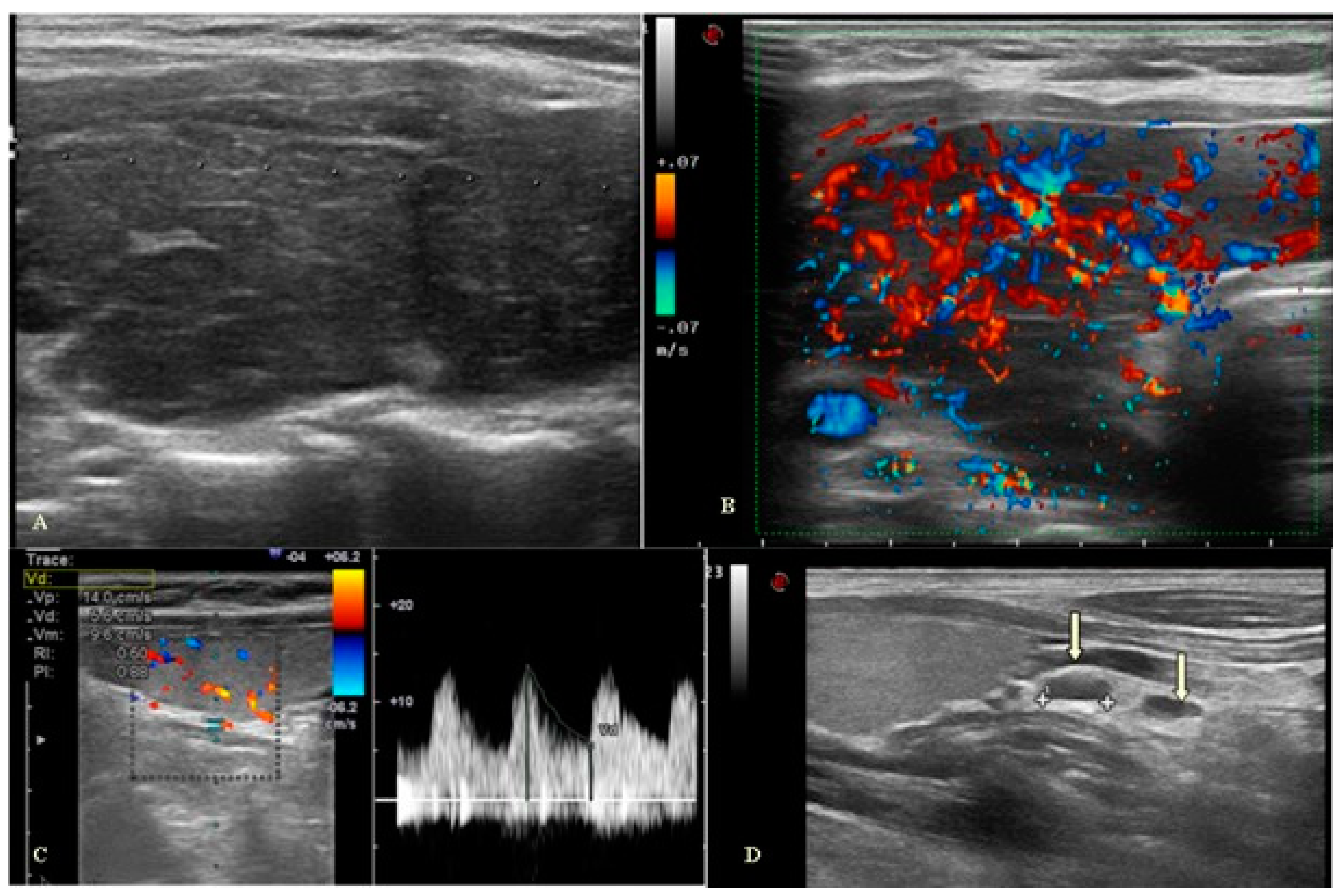

5] On ultrasound examination, HT may initially present as an enlarged thyroid gland with multiple small hypoechoic nodules surrounded by areas of healthy, fibrosis thyroid parenchyma in a pattern resembling that of giraffe skin.[

9] The gland appearance progresses to chronic hypertrophic thyroiditis, which is diffusely enlarged and characterized by multiple hypoechoic pseudo nodules separated by fibrotic bands. In some cases, the gland may further progress to the atrophic form, thus becoming smaller, with ill-defined contours and diffusely heterogeneous parenchyma. In the latter chronic phase of HT, ultrasound findings include a small, ill-defined gland with diffusely heterogeneous parenchyma and absence of flow on Doppler ultrasound due to extensive fibrosis.[

10] The parenchymal vascularity can vary from hypovascular to diffusely hypervascular.[

11] Hypervascularity results from the action of elevated levels of TSH and decreases when TSH levels normalize.[

12,

13] In HT, hypervascularity is usually mild, and blood flow rates are within normal limits.[

14] The resistive index (RI) value in patients with thyroiditis is significantly lower than that in healthy subjects, regardless of the degree of vascularization. This value, especially in pediatric patients, assumes a key role in the ultrasound diagnosis of thyroiditis and appears to correlate positively with the degree of glandular fibrosis.[

15] Patients with HT frequently display reactive cervical lymph node enlargement, which seems related to the autoimmune process.[

16]

The association between HT and dermatological disorders has been widely demonstrated. Skin manifestations associated with HT fall into two categories: i) diseases caused by the action of thyroid hormones on the skin and ii) immune-mediated inflammatory skin diseases (IMID) that have a known or suspected autoimmune etiology.[

17,

18,

19] This second type of skin disease is significantly more frequent in patients with HT because of the genetic predisposition to develop autoimmunity.[

20] Indeed, it has been found to be associated with vitiligo, alopecia areata, systemic lupus erythematosus, systemic sclerosis, bullous pemphigoid, and vulgar pemphigus.[

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]

This study aims to evaluate clinical and ultrasound parameters in patients with HT and their possible association with the concomitant presence of dermatological pathologies.

Patients and Methods

Study Design

This is a cross-sectional observational study in which 100 patients with HT, defined by the presence of positive Ab-TPO (regardless of the time of the diagnosis), aged ≥18 years, were enrolled. These patients attended the endocrinology outpatient clinic and signed a regular informed consent.

Endocrinological Examination

According to clinical practice, enrolled patients underwent endocrinological examination with evaluation of thyroid function, including TSH, free thyroxine (FT4), free triiodothyronine (FT3), and autoantibodies against the two thyroid-specific antigens: Ab-TG and Ab-TPO.

Ultrasound Evaluation

All ultrasound examinations were performed with an Esaote MyLab Eight XP ultrasound machine by two sonographers with more than 10 years of experience.

Ultrasound parameters that contribute to the diagnosis of thyroiditis consist of the B-mode assessment (glandular volume, echotexture and echogenicity of thyroid parenchyma, presence of nodulations), the color Doppler vascularity with calculation of the RI of the inferior thyroid artery (ITA) and the presence and location of reactive lymph nodes were also evaluated. The analysis of the echogenicity of the thyroid parenchyma was performed subjectively by comparing it with the echogenicity of the prethyroid muscles and submandibular gland, classifying it as isoechogenic, hyperechogenic, and hypoechogenic with respect to these structures. The normal thyroid gland typically exhibits greater echogenicity than the prethyroid muscles and is slightly higher than the submandibular glands. Thyroid parenchyma is considered hypoechoic when its echo levels are similar or lower than those of the submandibular glands but higher than those of the muscles (slightly hypoechoic) or are similar to those of the prethyroid muscles (hypoechoic). On sonography examinations, cervical lymph nodes are usually classified into eight regions. Normal and reactive lymph nodes are usually found in submandibular, parotid, superior cervical, and posterior triangle regions. On gray-scale ultrasonography, normal and reactive lymph nodes tend to be hypoechoic with respect to adjacent muscles and oval (short to long axis ratio (S/L) <0.5), except for submandibular and parotid lymph nodes, which are usually round (S/L ≥0.5) and have an echogenic hilum. On color Doppler, power Doppler, and 3D sonography, normal cervical lymph nodes show hilar vascularity or appear avascular, whereas reactive lymph nodes show predominantly hilar vascularity. Inflammation causes vasodilatation, which increases blood flow velocity in reactive lymph nodes.

Dermatological Examination

All enrolled patients were examined by a dermatologist who collected a detailed medical history (personal or family medical history, occupational exposures, long-term exposure to sunlight or other forms of radiation, drug use, etc.) and performed an examination of the entire skin surface, as well as hair, nails and mucous membranes to assess dermatological diseases. The dermatological examination was performed using an appropriate light source and magnification, assessing the skin lesions’ distribution, location, size, demarcation, morphology, and color. Dermoscopy and Wood's lamp were used, microscopic and culture examinations for germ and fungal were carried out, and skin biopsy was used as an additional diagnostic tool when needed.

Statistical Analysis

Categorical variables were reported through absolute and relative frequencies, while continuous variables were reported through median values and min–max intervals. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov normality test was calculated for all the continuous variables. The Mann–Whitney U test or Student’s t-test was performed to explore the differences between continuous variables, depending on the nature of the data distribution. The relationships between categorical variables were analyzed using Pearson's chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. The correlations between variables were evaluated using Spearman’s Rank correlation coefficient. p≤0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS version 21.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

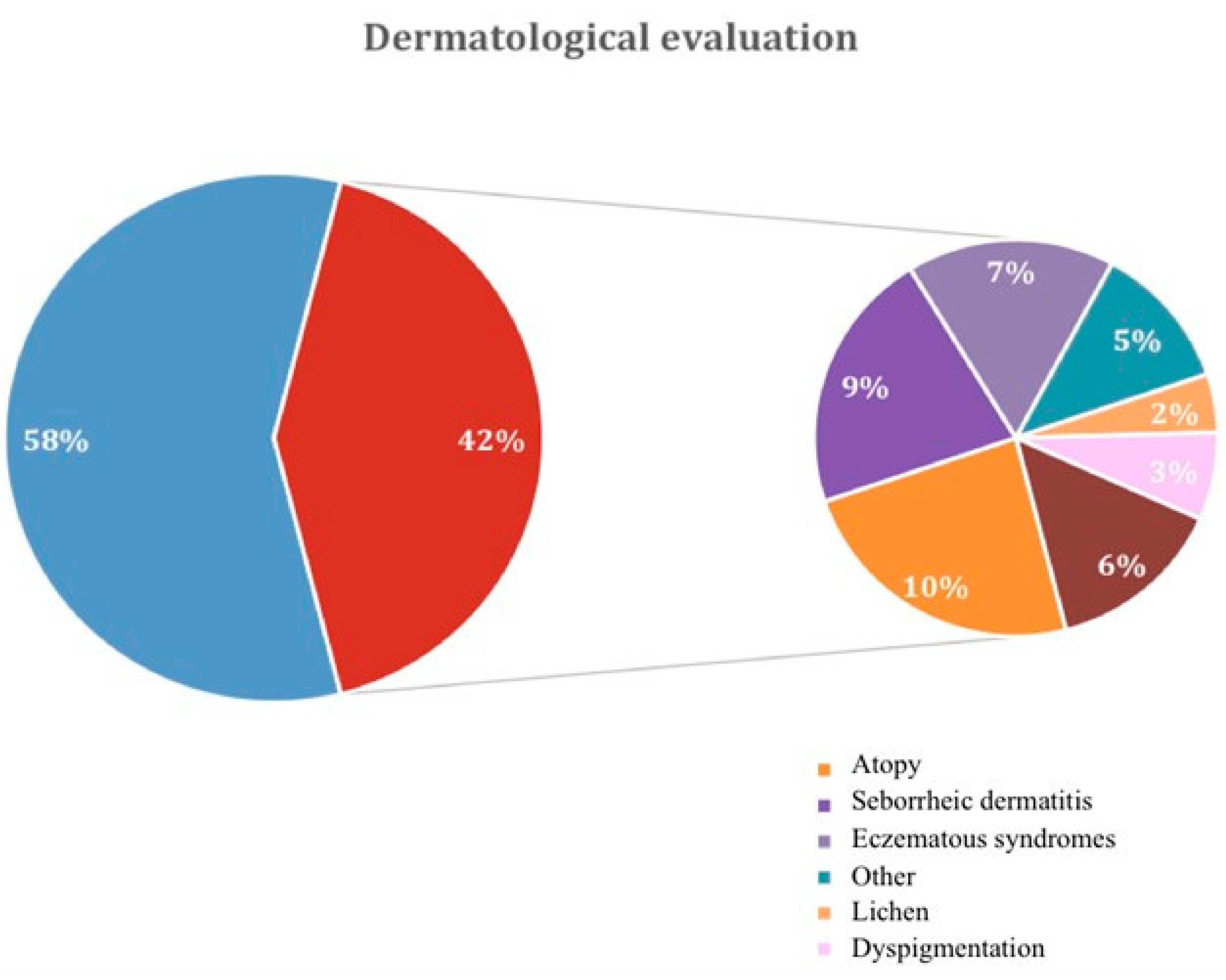

One hundred patients were enrolled in this cross-sectional study, 92% female and 8% male, with a median age of 43.66±12.40 years. Dermatological diseases were detected in 53% of patients, including 42% with immune-related pathologies and 11% with non-immune-related dermatological diseases, as summarized in

Figure 1 and

Supplementary Table S1. To assess the factors that increased the risk of dermatological manifestations, patients were categorized into two groups: patients without concomitant dermatological diseases (group 1, 58 patients) and those with dermatological diseases (group 2, 42 patients). Data about age, sex, body mass index, and familiarity for thyroid disorders (

Table 1), as well as TSH, FT3, FT4, Ab-TPO, Ab-TG (

Table 2) and thyroid ultrasound parameters levels (

Table 3) were collected. The two groups were homogeneous for sex and age, while there was a statistically significant difference in the percentage of family history of thyroid disorders (22.4% in group 1

vs 52.4% in group 2, p=0.002,

Table 1). In most cases, patients had normal thyroid function; thyroid function was not different between groups (

Table 2). Based on the diagnosis of HT, the mean antibody titer was significantly altered in all patients (Ab-TPO: 155.5 (9–11,728) UI/ml in group 1; Ab-TPO: 193 (10–13,000) UI/ml in group 2; Ab-TG: 152.5 (9–3,854) UI/ml in group 1; Ab-TG: 97.0 (4.6–1,000) UI/ml in group 2 (

Table 2)). At ultrasound examination, the most prevalent thyroid features were enlargement and hypervascularization of the gland accompanied by lymphadenopathy (

Figure 2). Our study found that within patients with thyroiditis and increased ITA diameter was observed in the case of concomitant dermatological pathologies. Indeed, there was a statistically significant difference in either the left ITA diameter, 1.2 (0.8–16) mm in group 1 and 1.6 (0.8–16) mm in group 2 (p=0.023), or in the right ITA diameter, 1.2 (0.7–3) mm in group 1 and 1.5 (0.9–2.9) mm in group 2 (p=0.005,

Table 3). No statistical difference in RI was found between the two groups, with a mean RI of 0.6 in group 1 and 0.7 in group 2. In addition, 86.3% of patients in group 1 and 100.0% in group 2 showed the presence of reactive lymph nodes, with a statistically significant difference between groups (p=0.016,

Table 3).

Discussion and Conclusions

HT is characterized by strong genetic susceptibility and polymorphism of several genes associated with disease occurrence and severity. Its autoimmune etiology and altered thyroid hormone levels implicate the association between HT and IMID.[

26,

28] IMID comprise atopic dermatitis, acne, vitiligo, psoriasis, and alopecia areata, which share the features of chronic inflammation[

29,

30,

31] and are characterized by a complex multifactorial etiology in which genetic and environmental factors contribute to disease development.[

17,

32]

Our study showed a high prevalence of both autoimmune and non-autoimmune dermatological disorders in our cohort of patients with HT. Accordingly, the association between HT and several dermatological disorders was demonstrated. Indeed, the association between HT and vitiligo is strongly supported by available data from large cohort studies.[

33,

34,

35,

36,

37] Additionally, multiple explanations for the molecular mechanisms of this association have been proposed, such as the presence of shared hereditary susceptibility genes or the expression of melanocyte-specific antigens in the thyroid gland.[

33,

37] In a meta-analysis, the authors found a statistically significant increased incidence of thyroiditis in the group of patients with melasma compared with controls.[

38] In addition, a retrospective study on 9,654 patients with psoriasis demonstrated a significant association between this dermatological disorder and HT.[

29,

39] HT is also associated with urticaria,[

40,

41,

42] lupus erythematosus,[

26,

37,

43] alopecia areata,[

44,

45] lichen[

19,

46,

47,

48] and scleroderma.[

23] Specifically, in patients with scleroderma presenting with complications in pregnancy, authors found that 53% had thyrotoxicosis due to HT.[

49] However, less is known about the prevalence of non-autoimmune dermatological disorders in patients with thyroiditis. Prevalence differs significantly among studies, probably because of the different ranges of antibody titers used as a normal reference and the possibility that antibody titers may change during the natural history of the disease.[

50]

Furthermore, while no association was found between thyroid hormone levels and the presence of dermatological diseases in our cohort, a more frequent family history of thyroid disease was observed in the group of patients with dermatological problems. Accordingly, for both thyroiditis and dermatitis, familiarity has been extensively demonstrated and linked to the human leukocyte antigens (HLA) locus.[

17,

32,

51] Regarding family history in HT, linkage and association studies have identified several genes involved in the occurrence of autoimmune thyroid disease (AITD), including the thyroglobulin gene and genes shared with other autoimmune diseases involved in regulating immunity. Genetic screenings have identified the

HLA locus, in particular

HLA-DR3, as a predisposing factor for HT.[

52] Another important AITD immune response susceptibility gene is

CD40, which plays a key role in the cross-talk between antigen-presenting cells and T cells.[

51] Studies involving families, populations, and epidemiological research have shown that genetic risk patterns of skin diseases such as psoriasis are linked to HLA locus.[

53]

Finally, clinical and radiological characteristics were evaluated to determine whether they could predict the presence of dermatological diseases, considering both those with and those without an autoimmune etiology in our cohort of patients. Interestingly, our study showed that a significantly higher thyroid vascularization and cervical lymphadenopathy characterized our cohort of patients with HT displaying dermatological disorders. In the literature, there is no reference level characterizing thyroid vascularization in HT, as this pathology presents with varying degrees of vascularity.[

54] Indeed, increased glandular vascularization does not seem related to thyroid function and appears purely expressive of inflammatory activity.[

55] Thus, the increased thyroid vascularization observed in patients with HT presenting with dermatological disorders could reflect the hyper-inflammatory state of this population. On the other hand, lymph node assessment is critical in diagnosing patients with thyroid pathology, especially considering the frequency of coexisting benign and malignant diseases and the propensity of malignant thyroid disease to metastasize to regional lymph nodes. Paratracheal lymph node hyperplasia was found more often in patients with HT than in controls.[

16] In another study, enlarged cervical lymph nodes were detected during neck ultrasound examination in 62.5% (n=25) of patients with HT.[

56] However, the presence of lymph nodes in intrathyroidal and pretracheal sites indicated HT with a specificity of 97.8%. Hyperplasia of regional lymph nodes is associated with clonal expansion of autoreactive T and B cells. It represents an early stage of the disease, while later lymphoid tissue frequently develops in the thyroid itself.[

57] However, to our knowledge, there is no study in the literature associating cervical lymphadenopathy in patients with HT and the presence of dermatological disorders.

The study's main limitation lies in the number of patients included, which impedes the drawing of more robust conclusions. However, the study evidenced a higher frequency of dermatological disease in patients with HT, particularly in the case of a family history of thyroid disease and in the presence of vascular flow alteration and cervical lymphadenopathy. Furthermore, based on the results obtained, it is possible to speculate on the usefulness of ultrasound evaluation of cervical lymph nodes and ITA in determining the risk of developing dermatological disorders. Early recognition and treatment of dermatological diseases would promote a better quality of life for patients.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

F.D. was responsible for the conception and design of the study. F.D., A.G., F.E. and F.M.S. were responsible for ultrasound evaluation. A.B., G.P. and M.M. were responsible for follow-up of patients and F.S. was responsible for statistical analysis. All the authors were responsible for data interpretation, writing, revision, and final approval of the manuscript.

Ethics

This study was approved by the Central Ethical Committee IRCCS Lazio Sezione IFO - Fondazione G.B. Bietti on 22/11/2016 under the number 878/16 RX ISG. The study was conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice (GCP), ICH topic E6 (R2 and CFDA GCP) guidelines, the rules of the Declaration of Helsinki, all applicable local law requirements and regulations concerning the privacy and security of personal information, including the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) (EU) 2016/679. Informed consent was obtained from all patients participating in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated and analyzed during this study are available within the paper. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Aashni Shah, Lara Vecchi, Ph.D., and Valentina Attanasio, Ph.D., (Polistudium Srl, Milan, Italy) for medical writing, editorial assistance and language editing and Vito Campagna, Silvia La Rosa, and Laura Di Buono for their patients’ support activities. They also thank the patients for their participation in the study.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Skevaki, C.; Wesemann, D.R. Antibody repertoire and autoimmunity. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2023, 151, 898–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huffaker, M.F.; Sanda, S.; Chandran, S.; Chung, S.A.; St Clair, E.W.; Nepom, G.T.; Smilek, D.E. Approaches to establishing tolerance in immune mediated diseases. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 744804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Chen, H.; Liu, X.; Zheng, X.; Shi, H.; Jiang, L.; Cui, D. Analysis of regulatory T cell subsets and their expression of helios and PD-1 in patients with Hashimoto thyroiditis. Int J Endocrinol 2019, 2019, 5368473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caturegli, P.; De Remigis, A.; Rose, N.R. Hashimoto thyroiditis: Clinical and diagnostic criteria. Autoimmun Rev 2014, 13, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ragusa, F.; Fallahi, P.; Elia, G.; Gonnella, D.; Paparo, S.R.; Giusti, C.; Churilov, L.P.; Ferrari, S.M.; Antonelli, A. Hashimotos' thyroiditis: Epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinic and therapy. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2019, 33, 101367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braverman LECooper DSWerner SCIngbar, S.H. Werner & Ingbar's the Thyroid: A Fundamental and Clinical Text. 10th ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Health; 2013.

- Weetman, A.P. An update on the pathogenesis of Hashimoto's thyroiditis. J Endocrinol Invest 2021, 44, 883–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mincer, D.L.; Jialal, I. Hashimoto Thyroiditis. [Updated 2023 Jul 29]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459262/.

- Virmani, V.; Hammond, I. Sonographic patterns of benign thyroid nodules: Verification at our institution. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2011, 196, 891–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khati, N.; Adamson, T.; Johnson, K.S.; Hill, M.C. Ultrasound of the thyroid and parathyroid glands. Ultrasound Q 2003, 19, 162–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, L.; Middleton, W.D.; Teefey, S.A.; Reading, C.C.; Langer, J.E.; Desser, T.; Szabunio, M.M.; Hildebolt, C.F.; Mandel, S.J.; Cronan, J.J. Hashimoto thyroiditis: Part 1, sonographic analysis of the nodular form of Hashimoto thyroiditis. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2010, 195, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogazzi, F.; Bartalena, L.; Brogioni, S.; Burelli, A.; Manetti, L.; Tanda, M.L.; Gasperi, M.; Martino, E. Thyroid vascularity and blood flow are not dependent on serum thyroid hormone levels: Studies in vivo by color flow doppler sonography. Eur J Endocrinol 1999, 140, 452–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagalla, R.; Caruso, G.; Novara, V.; Cardinale, A.E. Analisi flussimetrica nelle malattie tiroidee: Ipotesi di integrazione con lo studio qualitativo con color-Doppler [Flowmetric analysis of thyroid diseases: Hypothesis on integration with qualitative color-Doppler study]. Radiol Med 1993, 85, 606–610. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Ceylan, I.; Yener, S.; Bayraktar, F.; Secil, M. Roles of ultrasound and power Doppler ultrasound for diagnosis of Hashimoto thyroiditis in anti-thyroid marker-positive euthyroid subjects. Quant Imaging Med Surg 2014, 4, 232–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarikaya, B.; Demirbilek, H.; Akata, D.; Kandemir, N. The role of the resistive index in Hashimoto's thyroiditis: A sonographic pilot study in children. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2012, 67, 1253–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.R.; Mohamed, H.; Catlin, J.; April, D.; Al-Qurayshi, Z.; Kandil, E. The presentation of lymph nodes in Hashimoto's thyroiditis on ultrasound. Gland Surg 2015, 4, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campanati, A.; Martina, E.; Offidani, A. The challenge arising from new knowledge about immune and inflammatory skin diseases: Where we are today and where we are going. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cianfarani F, Baldini E, Cavalli A, Marchioni E, Lembo L, Teson M, Persechino S, Zambruno G, Ulisse S, Odorisio T, D'Armiento M. TSH receptor and thyroid-specific gene expression in human skin. J Invest Dermatol 2010, 130, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brankov, N.; Conic, R.Z.; Atanaskova-Mesinkovska, N.; Piliang, M.; Bergfeld, W.F. Comorbid conditions in lichen planopilaris: A retrospective data analysis of 334 patients. Int J Womens Dermatol 2018, 4, 180–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasumagic-Halilovic, E.; Begovic, B. Thyroid autoimmunity in patients with skin disorders. In: Thyroid Hormone. Agrawal NK. (Eds). InTech Open. (2012). [CrossRef]

- Aithal, S.; Ganguly, S.; Kuruvila, S. Coexistence of mucous membrane pemphigoid and vitiligo. Indian Dermatol Online J 2014, 5, 485–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonelli, A.; Fallahi, P.; Mosca, M.; Ferrari, S.M.; Ruffilli, I.; Corti, A.; Panicucci, E.; Neri, R.; Bombardieri, S. Prevalence of thyroid dysfunctions in systemic lupus erythematosus. Metabolism 2010, 59, 896–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagnato, G.L.; Roberts, W.N.; Fiorenza, A.; Arcuri, C.; Certo, R.; Trimarchi, F.; Ruggeri, R.M.; Bagnato, G.F. Skin fibrosis correlates with circulating thyrotropin levels in systemic sclerosis: Translational association with Hashimoto's thyroiditis. Endocrine 2016, 51, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallahi, P.; Ruffilli, I.; Giuggioli, D.; Colaci, M.; Ferrari, S.M.; Antonelli, A.; Ferri, C. Associations between systemic sclerosis and thyroid diseases. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2017, 8, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldini, E.; Odorisio, T.; Tuccilli, C.; Persechino, S.; Sorrenti, S.; Catania, A.; Pironi, D.; Carbotta, G.; Giacomelli, L.; Arcieri, S.; Vergine, M.; Monti, M.; Ulisse, S. Thyroid diseases and skin autoimmunity. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 2018, 19, 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunzler, E.; Hynan, L.S.; Chong, B.F. Autoimmune diseases in patients with cutaneous lupus erythematosus. JAMA Dermatol 2018, 154, 712–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, V.K.; Vashist, S.; Chauhan, P.S.; Mehta, K.I.S.; Sharma, V.; Sharma, A. Clinico-Epidemiological Profile of Patients with Vitiligo: A Retrospective Study from a Tertiary Care Center of North India. Indian Dermatol Online J 2019, 10, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomer, Y. Genetic susceptibility to autoimmune thyroid disease: Past, present, and future. Thyroid 2010, 20, 715–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furue, K.; Ito, T.; Tsuji, G.; Kadono, T.; Nakahara, T.; Furue, M. Autoimmunity and autoimmune co-morbidities in psoriasis. Immunology 2018, 154, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Liang, G.; Calderone, R.; Bellanti, J.A. Vitiligo and Hashimoto's thyroiditis: Autoimmune diseases linked by clinical presentation, biochemical commonality, and autoimmune/oxidative stress-mediated toxicity pathogenesis. Med Hypotheses 2019, 128, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diotallevi, F.; Campanati, A.; Martina, E.; Radi, G.; Paolinelli, M.; Marani, A.; Molinelli, E.; Candelora, M.; Taus, M.; Galeazzi, T.; Nicolai, A.; Offidani, A. The role of nutrition in immune-mediated, inflammatory skin disease: A narrative review. Nutrients 2022, 14, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McInnes, I.B.; Gravallese, E.M. Immune-mediated inflammatory disease therapeutics: Past, present and future. Nat Rev Immunol 2012, 21, 680–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldini, E.; Odorisio, T.; Sorrenti, S.; Catania, A.; Tartaglia, F.; Carbotta, G.; Pironi, D.; Rendina, R.; D'Armiento, E.; Persechino, S.; Ulisse, S. Vitiligo and Autoimmune Thyroid Disorders. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2017, 8, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bae, J.M.; Lee, J.H.; Yun, J.S.; Han, B.; Han, T.Y. Vitiligo and overt thyroid diseases: A nationwide population-based study in Korea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017, 76, 871–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.W.; Huang, Y.C. Vitiligo and autoantibodies: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2018, 16, 845–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrijman, C.; Kroon, M.W.; Limpens, J.; Leeflang, M.M.; Luiten, R.M.; van der Veen, J.P.; Wolkerstorfer, A.; Spuls, P.I. The prevalence of thyroid disease in patients with vitiligo: A systematic review. Br J Dermatol 2012, 167, 1224–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Sun, C.; Jiang, S.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, X.H.; Wu, Y.; Chen, H.D. The prevalence of thyroid disorders in patients with vitiligo: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2019, 9, 803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kheradmand, M.; Afshari, M.; Damiani, G.; Abediankenari, S.; Moosazadeh, M. Melasma and thyroid disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Dermatol 2019, 58, 1231–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiguradze, T.; Bruins, F.M.; Guido, N.; Bhattacharya, T.; Rademaker, A.; Florek, A.G.; Posligua, A.; Amin, S.; Laumann, A.E.; West, D.P.; Nardone, B. Evidence for the association of Hashimoto's thyroiditis with psoriasis: A cross-sectional retrospective study. Int J Dermatol 2017, 56, 553–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazanfar, M.N.; Kibsgaard, L.; Thomsen, S.F.; Vestergaard, C. Risk of comorbidities in patients diagnosed with chronic urticaria: A nationwide registry-study. World Allergy Organ J 2020, 13, 100097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafipour, M.; Zareizadeh, M.; Najafipour, F. Relationship between chronic urticaria and autoimmune thyroid disease. J Adv Pharm Technol Res 2018, 9, 158–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Diaz, S.N.; Sanchez-Borges, M.; Rangel-Gonzalez, D.M.; Guzman-Avilan, R.I.; Canseco-Villarreal, J.I.; Arias-Cruz, A. Chronic urticaria and thyroid pathology. World Allergy Organ J 2020, 13, 100101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, L.; Zarbo, A.; Isedeh, P.; Jacobsen, G.; Lim, H.W.; Hamzavi, I. Comorbid autoimmune diseases in patients with vitiligo: A cross-sectional study. J Am Acad Dermatol 2016, 74, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, T.Y.; Lee, J.H.; Noh, T.K.; Choi, M.W.; Yun, J.S.; Lee, K.H.; Bae, J.M. Alopecia areata and overt thyroid diseases: A nationwide population-based study. J Dermatol 2018, 45, 1411–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Lee, Y.B.; Kim, B.J.; Lee, W.S. Screening of thyroid function and autoantibodies in patients with alopecia areata: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2019, 80, 1410–1413.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarneri, F.; Giuffrida, R.; Di Bari, F.; Cannavò, S.P.; Benvenga, S. Thyroid autoimmunity and Lichen. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2017, 8, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robledo-Sierra, J.; Landin-Wilhelmsen, K.; Filipsson Nyström, H.; Eggertsen, R.; Larsson, L.; Dafar, A.; Warfvinge, G.; Mattsson, U.; Jontell, M. A mechanistic linkage between oral lichen planus and autoimmune thyroid disease. Oral Dis 2018, 24, 1001–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serni, L.; Barbato, L.; Nieri, M.; Mallardi, M.; Noce, D.; Cairo, F. Association between oral lichen planus and Hashimoto thyroiditis: A systematic review. Oral Dis 2023, Epub ahead of print. [CrossRef]

- Triggianese, P.; Conigliaro, P.; Chimenti, M.S.; Barbato, C.; Greco, E.; Kroegler, B.; De Carolis, C.; Perricone, R. Systemic sclerosis: Exploring the potential interplay between thyroid disorders and pregnancy outcome in an Italian Cohort. Isr Med Assoc J 2017, 19, 473–477. [Google Scholar]

- Niepomniszcze, H.; Huaier Amad, R. Skin disorders and thyroid diseases. J Endocrinol Invest 2001, 24, 628–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mysliwiec, J.; Oklota, M.; Nikolajuk, A.; Waligorski, D.; Gorska, M. Serum CD40/CD40L system in Graves' disease and Hashimoto's thyroiditis related to soluble Fas, FasL and humoral markers of autoimmune response. Immunol Invest 2007, 36, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandon N, Zhang L, Weetman AP. HLA associations with Hashimoto's thyroiditis. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1991, 34, 383–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Poon, A.; Yeung, C.; Helms, C.; Pons, J.; Bowcock, A.M.; Kwok, P.Y.; Liao, W. A genetic risk score combining ten psoriasis risk loci improves disease prediction. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e19454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vita, R.; Di Bari, F.; Perelli, S.; Capodicasa, G.; Benvenga, S. Thyroid vascularization is an important ultrasonographic parameter in untreated Graves' disease patients. J Clin Transl Endocrinol 2019, 15, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuen, H.Y.; Wong, K.T.; Ahuja, A.T. Sonography of diffuse thyroid disease. Australas J Ultrasound Med 2016, 19, 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medlock, D.; Chaljub, E.; Gavin, M.; Peiris, A.N. Shifting cervical lymphadenopathy in Hashimoto's disease. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 2019, 32, 235–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, R.; Al-Shaikh, S.; Akhtar, M. Hashimoto thyroiditis: A century later. Adv Anat Pathol 2012, 19, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).