Submitted:

11 March 2024

Posted:

12 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Traditional Recipes

2.2.1.1. Soy Juice

2.2.1.2. Tofu

2.2.1.3. Tempeh

2.2.1.4. Miso

2.2.1.5. Hydrated Soy Proteins

2.2.1.6. Commercial Tofu and Tempeh

2.2.2. ELISA

2.2.2.1. Samples Preparation

2.2.1.2. Assay

2.2.1.3. Characteristics of the ELISA

2.3. Statistical Treatments

3. Results

3.1. Impact of Traditional Process on Isoflavones Content in Tempeh and Miso

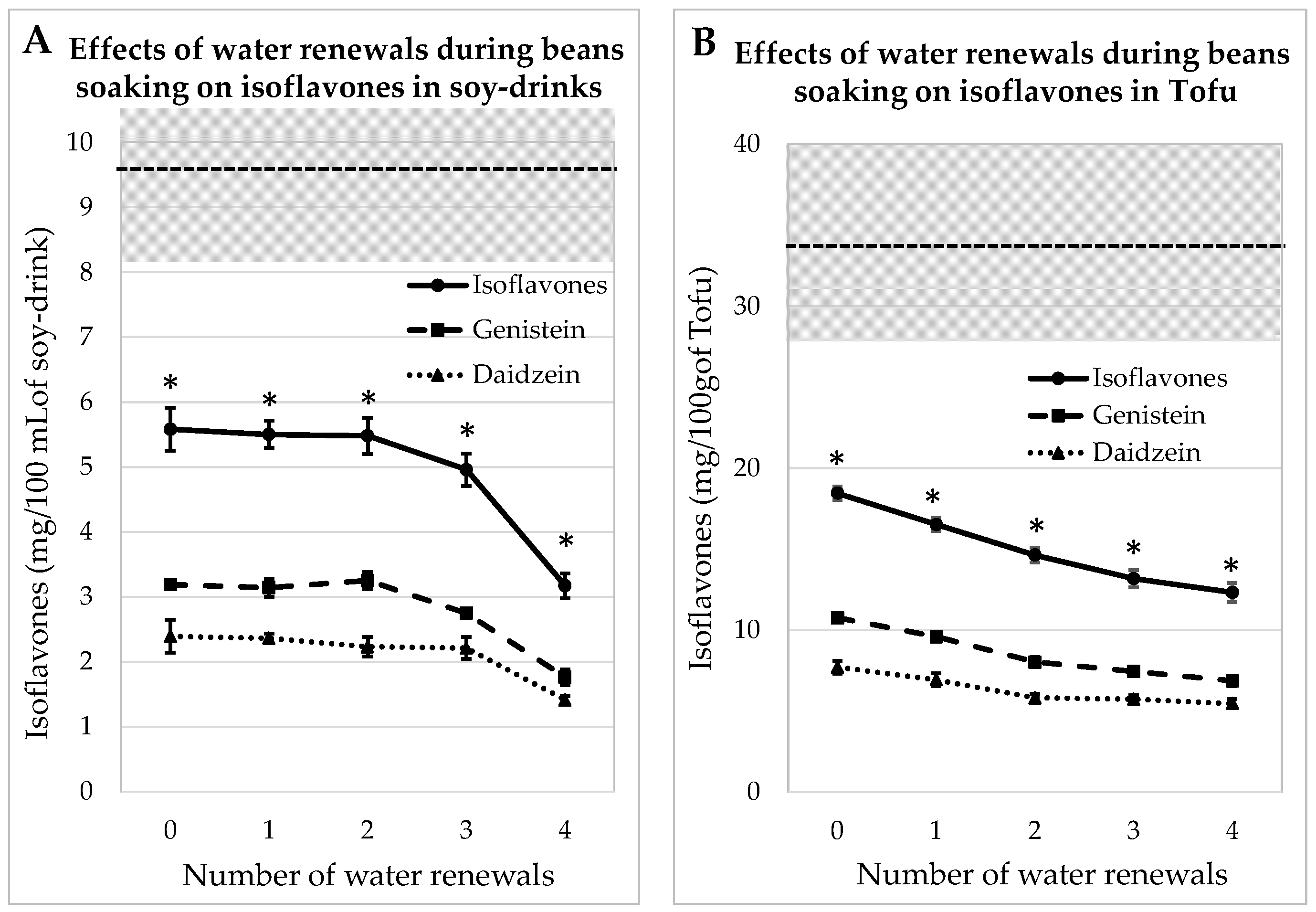

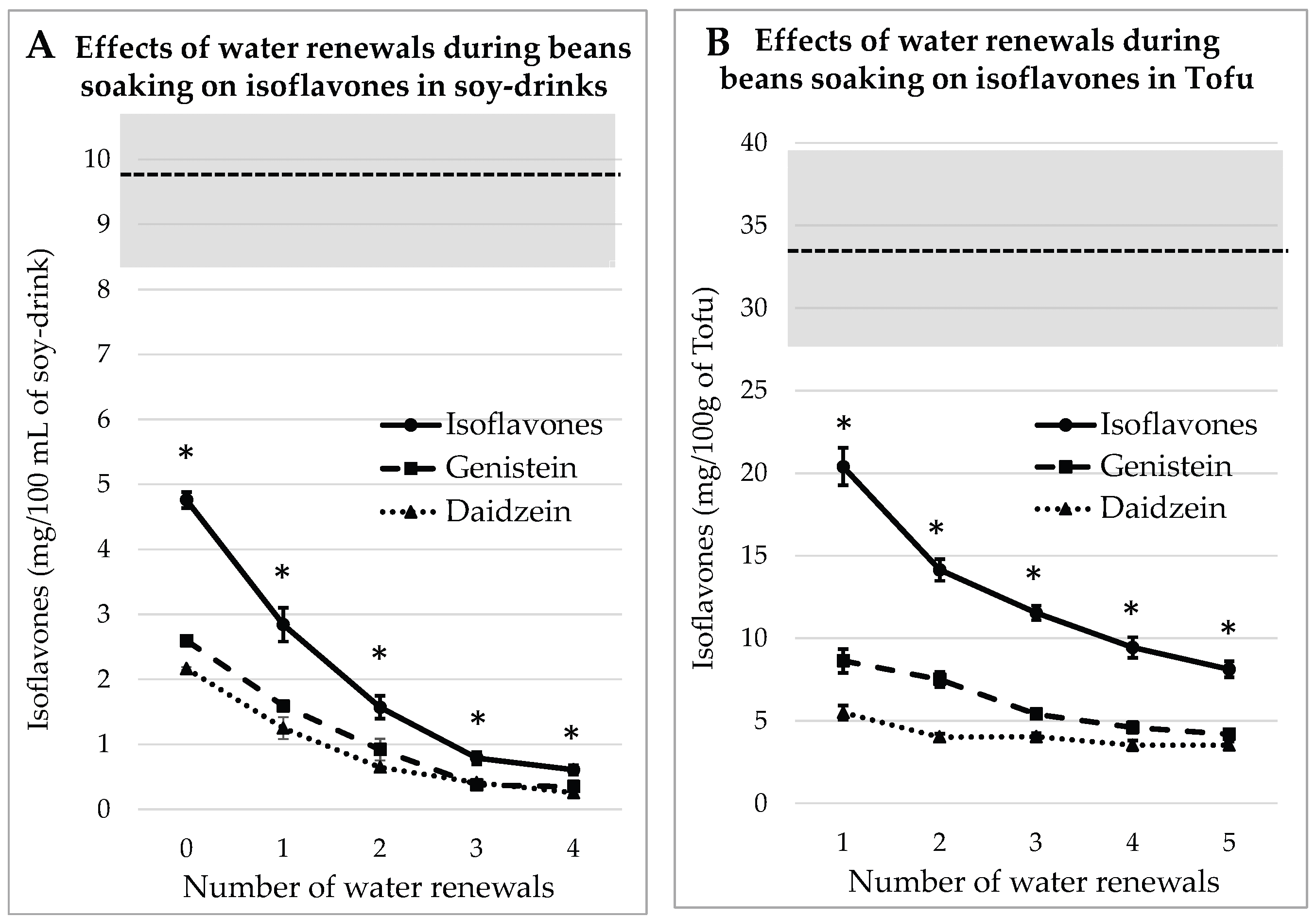

3.2. Impact of Water Renewals during Beans Soaking for Soy Juice and Tofu

3.2.1. Process Tested on Whole Soy-Beans

3.2.2. Process Tested on Dehulled Beans

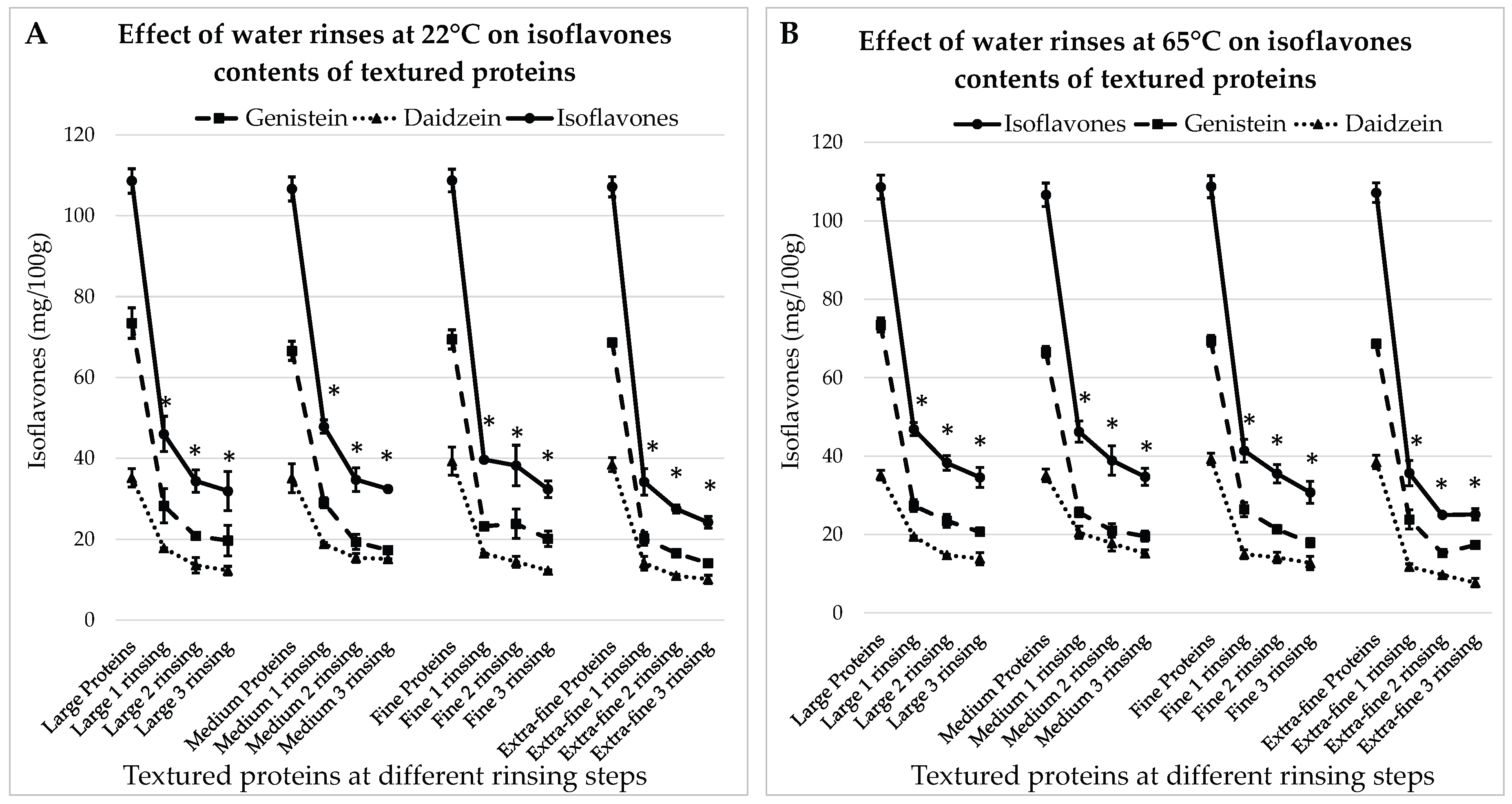

3.3. Impact of Water Renewals on the Levels of Isoflavones in Textured Proteins

3.3.1. Treatment with Water at 22°C

3.3.2. Treatment with Water at 65°C

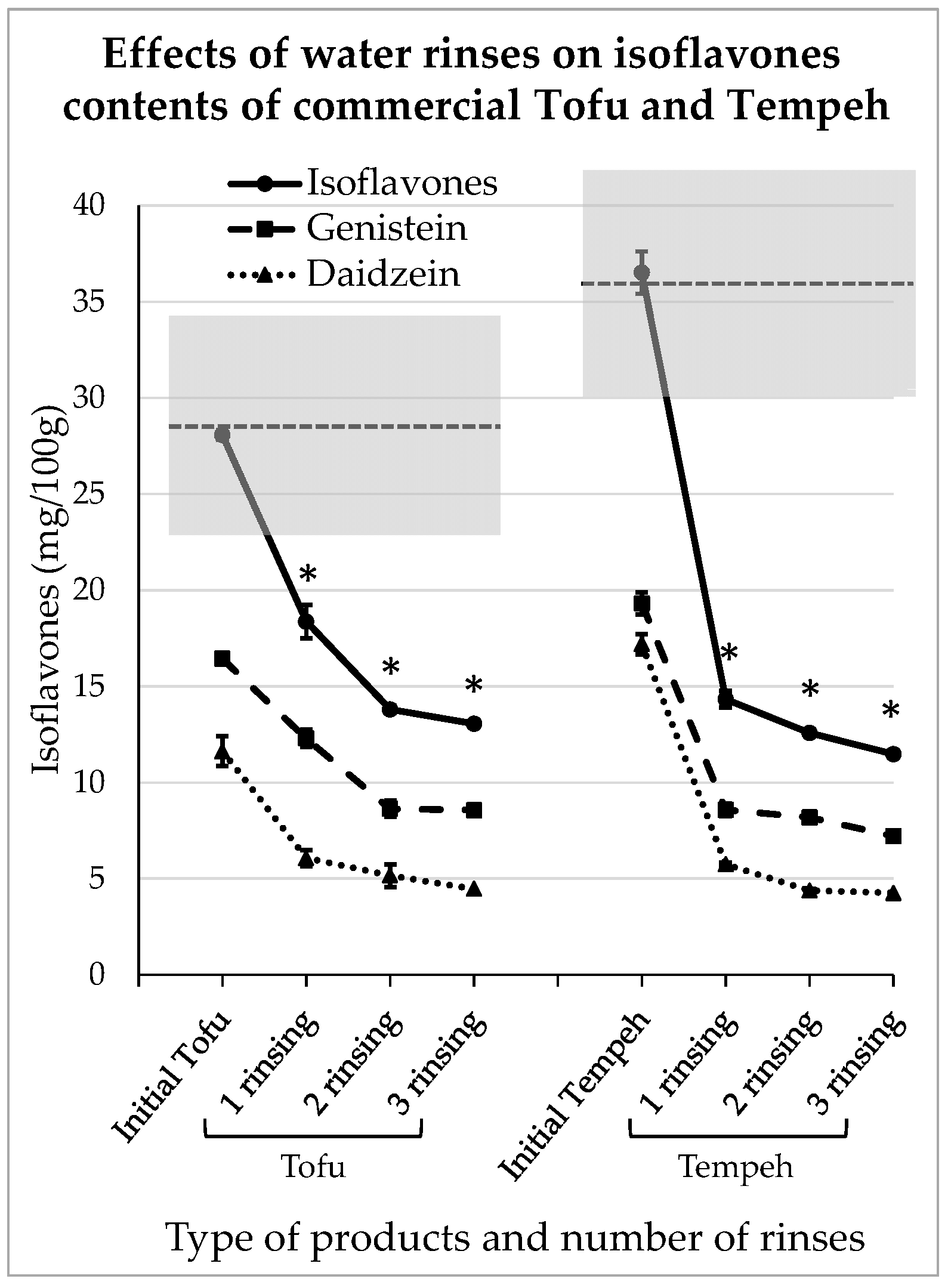

3.4. Impact of Domestic Rinsing on Isoflavones Content of Comercial Tofu and Tempeh

4. Discussion

4.1. Data Analysis

4.2. Traditional Treatments

4.3. Health Effects

4.3.1. Traditional Pharmacopeia

4.3.2. Toxic Effects and Reference Doses

4.3.3. Beneficial Health Effects for a Restricted Population

4.4. Consequences of This Finding on the Estimation of the Populations Exposure

| Location | Estimation method | Estimated IFs Intake (mg) | IFs Plasma (nM) | Time of plasma collection | Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Los Angeles | Hawaii Food Composition Database based on commercial items | 23.72 | 30.1 | No specific instruction |

[69] |

| China (Shanghai) |

USDA-ISU database based on commercial items |

23.5 | 106.3 | No specific instruction |

[70] |

| 58.15 | 119.9 | ||||

| 84.5 | 146.3 | ||||

| 284.0 | 188.3 | ||||

| Japan | From [71] (commercial items) | 46.4 | 419.2 | Overnight fasting | [72] |

| Japan | From [71] (commercial items) | 40.8 | 411.0 | After fasting > 5h | [73] |

| England | USDA-ISU database based on commercial items |

33.7 | 510 | Not precise | [74] |

| Japan | From [71] (commercial items) | 32.5 | 553* | No specific instruction |

[75] |

| 34.8 | 605* | ||||

| The Netherland | Strictly controlled soy protein diet |

48.5 | 2160 | Fasting samples after chronic intake |

[76] |

| 100.1 | 2530 | ||||

| 104.2 | 2900 | ||||

| 93.9 | 4800 | ||||

| Hawaii | USDA-ISU database based on commercial items |

96.0 | 5600 | 12h fasting and chronic intake | [77] |

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lee, A.; Bensaada, S.; Lamothe, V.; Lacoste, M.; Bennetau-Pelissero, C. Endocrine disruptors on and in fruits and vegetables: Estimation of the potential exposure of the French population. Food Chem. 2022, 373, 131513–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gier K, Preininger C, Sauer U. A Chip for Estrogen Receptor Action: Detection of Biomarkers Released by MCF-7 Cells through Estrogenic and Anti-Estrogenic Effects. Sensors (Basel). 2017, 17, 1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canivenc-Lavier MC, Bennetau-Pelissero C. Phytoestrogens and Health Effects. Nutrients. 2023, 15, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NTP. Multigenerational reproductive study of genistein (Cas No. 446-72-0) in Sprague-Dawley rats (feed study). Natl Toxicol Program Tech Rep Ser. 2008, 539, 1–266. [Google Scholar]

- NTP. Toxicology and carcinogenesis studies of genistein (Cas No. 446-72-0) in Sprague-Dawley rats (feed study). Natl Toxicol Program Tech Rep Ser. 2008, 545, 1–240. [Google Scholar]

- Cao ZH, Green-Johnson JM, Buckley ND, Lin QY. Bioactivity of soy-based fermented foods: A review. Biotechnol Adv. 2019, 37, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baraibar Norberg M, Deutsh L. The first soybean cycle (domestication to 900 CE). In The Soybean Through World History. Lessons for Sustainable Agrofood Systems 1st ed Routledge studies in Food, Society and the Environment Taylor & Francis UK, 2023; pp: 22-56.

- Zhao, Z. New Archaeobotanic Data for the Study of the Origins of Agriculture in China. Current Anthropology. 2011, 52, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee C-H, Kim ML. History of Fermented Foods in Northeast Asia. In Ethnic Fermented Foods and Alcoholic Beverages of Asia Tamang JP. Ed Spinger India 2016; pp: 1-16.

- Lander B, DuBois TDA. History of Soy in China: From Weedy Bean to Global Commodity In Ethnic Fermented Foods and Alcoholic Beverages of Asia In The age of the soybean: An environmental history of soy During the great acceleration da Silva CM, de Majo C. Eds 2022: pp 29-47.

- Traditional Tofu making experience in Debao Guangxi. Available online: https://twojadebowls.com/2013/08/16/traditional-tofu-making-experience-in-debao-guangxi/ (accessed on 27 February 2024).

- Bensaada S, Chabrier F, Ginisty P, Ferrand C, Peruzzi G, et al. Improved Food-Processing Techniques to Reduce Isoflavones in Soy-Based Foodstuffs. Foods. 2023, 12, 1540–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClure T, Cocuron JC, Osmark V, McHale LK, Alonso AP. Impact of Environment on the Biomass Composition of Soybean (Glycine max) seeds. J Agric Food Chem. 2017, 65, 6753–6761.

- Vergne S, Sauvant P, Lamothe V, Chantre P, Asselineau J, et al. Influence of ethnic origin (Asian v. Caucasian) and background diet on the bioavailability of dietary isoflavones. Br J Nutr. 2009, 102, 1642–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu J, Zhao Q, Qiu Y, Zhang Y, Cui S, et al. Soy Isoflavones Intake and Obesity in Chinese Adults: A Cross-Sectional Study in Shang-hai, China. Nutrients. 2021, 13, 2715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murai U, Sawada N, Charvat H, Inoue M, Yasuda N, et al. Soy product intake and risk of incident disabling dementia: the JPHC Disabling Dementia Study. Eur J Nutr. 2022, 61, 4045–4057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Lopez A, Lamothe V, Delample M, Denayrolles M, Bennetau-Pelissero C. Removing isoflavones from modern soyfood: Why and how? Food Chem. 2016, 210, 286–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Japanese Lab. How miso was made traditionally. Available online: https://thejapanesefoodlab.com/traditional-japanese-miso#how/ (accessed on 27 February 2024).

- Vergne S, Titier K, Bernard V, Asselineau J, Durand M, et al. Bioavailability and Urinary Excretion of Isoflavones in Humans: Effects of Soy-Based Supplements Formulation and Equol Production. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2007, 43, 1488–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinkaruk S, Durand M, Lamothe V, Carpaye A, Martinet A, et al. Bioavailability of Glycitein Relatively to Other Soy Isoflavones in Healthy Young Caucasian Men. Food Chem. 2012, 135, 1104–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennetau-Pelissero C, Le Houérou C, Lamothe V, Le Menn F, Babin P, et al. Synthesis of Haptens and Conjugates for ELISAs of Phytoestrogens. Development of the Immunological Tests. J Agric Food Chem. 2000, 48, 305–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Houerou C, Bennetau-Pelissero C, Lamothe V, Le Menn F, Babin P, et al. Syntheses of Novel Hapten-Protein Conjugates for Production of Highly Specific Antibodies to Formononetin, Daidzein and Genistein. Tetrahedron. 2000, 56, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennetau-Pelissero, C. Plant Proteins from Legumes. In: Mérillon, JM., Ramawat, K. (eds) Bioactive Molecules in Food Vol 1. Reference Series in Phytochemistry. Springer, Cham. 2018 pp. 223–66.

- Afssa, Afssaps. Sécurité et bénéfices des phyto-estrogènes apportés par l’alimentation – Recommandations Rapport d’expertise Mars 2005.

- Kao TH, Lu YF, Hsieh HC, Chen BH. Stability of isoflavone glucosides during processing of soymilk and tofu. Food Res Int. 2004, 37, 891–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung IM, Seo SH, Ahn JK, Kim SH. Effect of processing, fermentation, and aging treatment to content and profile of phenolic compounds in soybean seed, soy curd and soy paste. Food Chem. 2011, 127, 960–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puri A, Mir SR, Panda BP. Effect of sequential bio-processing conditions on the content and composition of vitamin K2 and isoflavones in fermented soy food. J Food Sci Technol. 2015, 52, 8228–8235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao Y, Zhang K, Zhang Z, Zhang C, Sun Y, et al. Fermented soybean foods: A review of their functional components, mechanism of action and factors influencing their health benefits. Food Res Int 2022, 158, 111575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuligowski M, Sobkowiak D, Polanowska K, Jasinska-Kuligowska I. Effect of different processing methods on isoflavone content in soybeans and soy products J Food Comp Anal 2022, 110, 104535–41.

- Shurtleff W, Aoyagi A. Early History of Soybeans and Soyfoods Worldwide (1024 BCE to 1899): Extensively Annotated Bibliography and Sourcebook. Lafayette, CA: Soyinfo Center. 2014.

- Wang S, Zhang S, Wang S, Gao P, Dai L. A comprehensive review on Pueraria: Insights on its chemistry and medicinal value. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020, 131, 110734–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennetts HW, Underwood EJ, Shier FL. A specific breeding problem of sheep on subterranean clover pastures in Western Australia. Aust Vet J. 1946, 23, 2–13. [Google Scholar]

- Findlay JK, Buckmaster JM, Chamley WA, Cumming IA, Hearnshaw H; et al. Release of luteinising hormone by œstradiol 17β and a gonadotrophin-releasing hormone in ewes affected with clover disease. Neuroendocrinol. 1973, 11, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen BL, Katz M. Further studies on pituitary and ovarian function in women receiving hormonal contraception. Contraception. 1981, 24, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassidy A, Bingham S, Setchell KD. Biological effects of a diet of soy protein rich in isoflavones on the menstrual cycle of premenopausal women. Am J Clin Nutr. 1994, 60, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrews MA, Schliep KC, Wactawski-Wende J, Stanford JB, Zarek SM, et al. Dietary factors and luteal phase deficiency in healthy eumenorrheic women. Hum Reprod. 2015, 30, 1942–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobsen BK, Jaceldo-Siegl K, Knutsen SF, Fan J, Oda K, et al. Soy isoflavone intake and the likelihood of ever becoming a mother: the Adventist Health Study-2. Int J Womens Health. 2014, 6, 377–384. [Google Scholar]

- Strom BL, Schinnar R, Ziegler EE, Barnhart KT, Sammel MD, et al. Exposure to soy-based formula in infancy and endocrinological and reproductive outcomes in young adulthood. JAMA. 2001, 286, 807–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upson K, Harmon QE, Laughlin-Tommaso SK, Umbach DM, Baird DD. Soy-based Infant Formula Feeding and Heavy Menstrual Bleeding Among Young African American Women. Epidemiology. 2016, 27, 716–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upson K, Adgent MA, Wegienka G, Baird DD. Soy-based infant formula feeding and menstrual pain in a cohort of women aged 23-35 years. Hum Reprod. 2019, 34, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin H, Lin Z, Vásquez E, Luan X, Guo F, Xu L. High soy isoflavone or soy-based food intake during infancy and in adulthood is associated with an increased risk of uterine fibroids in premenopausal women: a meta-analysis. Nutr Res. 2019, 71, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrareddy A, Muneyyirci-Delale O, McFarlane SI, Murad OM. Adverse effects of phytoestrogens on reproductive health: a report of three cases. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2008, 14, 132–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imai H, Nishikawa H, Suzuki A, Kodama E, Iida T, et al. Secondary Hypogonadism due to Excessive Ingestion of Isoflavone in a Man. Intern Med. 2022, 26. [Google Scholar]

- Chavarro JE, Toth TL, Sadio SM, Hauser R. Soy food and isoflavone intake in relation to semen quality parameters among men from an infertility clinic. Hum Reprod. 2008, 23, 2584–2590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toshima H, Suzuki Y, Imai K, Yoshinaga J, Shiraishi H, et al. Endocrine disrupting chemicals in urine of Japanese male partners of subfertile couples: a pilot study on exposure and semen quality. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2012, 215, 502–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia Y, Chen M, Zhu P, Lu C, Fu G, et al. Urinary phytoestrogen levels related to idiopathic male infertility in Chinese men. Environ Int. 2013, 59, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumford SL, Kim S, Chen Z, Boyd Barr D, Buck Louis GM. Urinary Phytoestrogens Are Associated with Subtle Indicators of Semen Quality among Male Partners of Couples Desiring Pregnancy. J Nutr. 2015, 145, 2535–2541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan G, Liu Y, Liu G, Wei L, Wen Y, et al. Associations between semen phytoestrogens concentrations and semen quality in Chinese men. Environ Int. 2019, 129, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt E, Dekant W, Stopper H. Assaying the estrogenicity of phytoestrogens in cells of different estrogen sensitive tissues. Toxicol In Vitro. 2001, 15, 433–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu Q, Yang Y, Yu J, Jin N. Soy isoflavone extracts stimulate the growth of nude mouse xenografts bearing estrogen-dependent human breast cancer cells (MCF-7). J Biomed Res. 2012, 26, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMichael-Phillips DF, Harding C, Morton M, Roberts SA, Howell A, et al. Effects of soy-protein supplementation on epithelial proliferation in the histologically normal human breast. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998, 68, 1431S–1435S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shike M, Doane AS, Russo L, Cabal R, Reis-Filho JS, et al. The effects of soy supplementation on gene expression in breast cancer: a randomized placebo-controlled study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014, 106, dju-189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Die MD, Bone KM, Visvanathan K, Kyrø C, Aune D, et al. Phytonutrients and outcomes following breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2024, 8, pkad104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messina, M. Impact of Soy Foods on the Development of Breast Cancer and the Prognosis of Breast Cancer Patients. Forsch Komplementmed. 2016, 23, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen M, Rao Y, Zheng Y, Wei S, Li Y, et al. Association between soy isoflavone intake and breast cancer risk for pre- and post-menopausal women: a meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. PLoS One 2014, 9, e89288. [Google Scholar]

- Finkeldey L, Schmitz E, Ellinger S. Effect of the Intake of Isoflavones on Risk Factors of Breast Cancer-A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Intervention Studies. Nutrients. 2021, 13, 2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caprio AM, Umano GR, Luongo C, Aiello F, Dello Iacono I, et al. Case report: Goiter and overt hypothyroidism in an iodine-deficient toddler on soy milk and hypoallergenic diet. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022, 13, 927726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fruzza AG, Demeterco-Berggren C, Jones KL. Unawareness of the effects of soy intake on the management of congenital hypothyroidism. Pediatrics. 2012, 130, e699–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conrad SC, Chiu H, Silverman BL. Soy formula complicates management of congenital hypothyroidism. Arch Dis Child. 2004, 89, 37–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan Y, Qian H, Wu Z, Li Z, Li X, et al. Exploratory analysis of the associations between urinary phytoestrogens and thyroid hormones among adolescents and adults in the United States: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2007-2010. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2022, 29, 2974–2984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathyapalan T, Manuchehri AM, Thatcher NJ, Rigby AS, Chapman T, et al. The effect of soy phytoestrogen supplementation on thyroid status and cardiovascular risk markers in patients with subclinical hypothyroidism: a randomized, double-blind, crossover study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011, 96, 1442–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo PP, Li P, Zhang XH, Liu N, Wang J, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine for natural and treatment-induced vasomotor symptoms: An overview of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2019, 36, 181–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen MN, Lin CC, Liu CF. Efficacy of phytoestrogens for menopausal symptoms: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Climacteric. 2015, 18, 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daily JW, Ko BS, Ryuk J, Liu M, Zhang W, et al. Equol Decreases Hot Flashes in Postmenopausal Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials. J Med Food. 2019, 22, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taku K, Melby MK, Kronenberg F, Kurzer MS, Messina M. Extracted or synthesized soybean isoflavones reduce menopausal hot flash frequency and severity: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Menopause. 2012, 19, 776–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam RM, Bell RJ, Rizvi F, Davis SR. Vasomotor symptoms in women in Asia appear comparable with women in Western countries: a systematic review. Menopause. 2017, 24, 1313–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taku K, Melby MK, Takebayashi J, Mizuno S, Ishimi Y, et al. Effect of soy isoflavone extract supplements on bone mineral density in menopausal women: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2010, 19, 33–42. [Google Scholar]

- Corbi G, Nobile V, Conti V, Cannavo A, Sorrenti V, et al. Equol and Resveratrol Improve Bone Turnover Biomarkers in Postmenopausal Women: A Clinical Trial. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24, 12063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu AH, Yu MC, Tseng CC, Twaddle NC, Doerge DR. Plasma isoflavone levels versus self-reported soy isoflavone levels in Asian-American women in Los Angeles County. Carcinogenesis. 2004, 25, 77–81. [Google Scholar]

- Frankenfeld CL, Lampe JW, Shannon J, Gao DL, Ray RM, et al. Frequency of soy food consumption and serum isoflavone concentrations among Chinese women in Shanghai. Public Health Nutr. 2004, 7, 765–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimira M, Arai Y, Shimoi K, Watanabe S. Japanese intake of flavonoids and isoflavonoids from foods. J Epidemiol. 1998, 8, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arai Y, Watanabe S, Kimira M, Shimoi K, Mochizuki R, et al. Dietary intakes of flavonols, flavones and isoflavones by Japanese women and the inverse correlation between quercetin intake and plasma LDL cholesterol concentration. J Nutr. 2000, 130, 2243–2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto S, Sobue T, Sasaki S, Kobayashi M, Arai Y, et al. Validity and reproducibility of a self-administered food-frequency questionnaire to assess isoflavone intake in a japanese population in comparison with dietary records and blood and urine isoflavones. J Nutr. 2001, 131, 2741–2747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verkasalo PK, Appleby PN, Allen NE, Davey G, Adlercreutz H, et al. Soya intake and plasma concentrations of daidzein and genistein: validity of dietary assessment among eighty British women (Oxford arm of the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition). Br J Nutr. 2001, 86, 415–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki M, Inoue M, Otani T, Sasazuki S, Kurahashi N, et al. Plasma isoflavone level and subsequent risk of breast cancer among Japanese women: a nested case-control study from the Japan Public Health Center-based prospective study group. J Clin Oncol. 2008, 26, 1677–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Velpen V, Hollman PC, van Nielen M, Schouten EG, Mensink M, et al. Large inter-individual variation in isoflavone plasma concentration limits use of isoflavone intake data for risk assessment. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2014, 68, 1141–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardner CD, Chatterjee LM, Franke AA. Effects of isoflavone supplements vs. soy foods on blood concentrations of genistein and daidzein in adults. J Nutr Biochem. 2009, 20, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan SG, Murphy PA, Ho SC, Kreiger N, Darlington G, et al. Isoflavonoid content of Hong Kong soy foods. J Agric Food Chem. 2009, 57, 5386–5390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Type of product | Number of Measurements | Portion Size (g) |

Mean GEN + DAI/portion (mg) | Standard Error of Mean/portion | Range of measurements * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raw soy beans | 5 | 100 | 84.6 | 8.3 | 72.5 to 100.6 |

| Toasted soy beans | 5 | 100 | 134.0 | 37.9 | 61.9 to 247.7 |

| Edamame | 2 | 120 | 49.2 | 14.1 | 35.1 to 63.3 |

| Soybean flour | 2 | 100 | 38.5 | 5.5 | 32.9 to 43.9 |

| Protein isolate (sports) | 3 | 165 | 52.2 | 12.3 | 39.8 to 64.5 |

| Soy-based drinks | 9 | 100 | 9.9 | 1.7 | 2.8 to 17.7 |

| Soy-based desert cream | 11 | 150 | 12.3 | 2.8 | 2.5 to 33.4 |

| Soy-based yogurt | 14 | 125 | 15.9 | 3.8 | 5.1 to 31.5 |

| Soy-based cream | 12 | 50 mL | 4.5 | 5.9 | 3.1 to 6.7 |

| Soy-based Vegan steak | 19 | 100 | 27.8 | 3.5 | 4.1 to 51.2 |

| Soy sausages | 4 | 90 | 24.8 | 7.3 | 11.1 to 44.1 |

| Soy-based raw pasta | 2 | 100 | 23.7 | 1.6 | 22.1 to 25.3 |

| Soy-based cooked pasta | 2 | 100 | 8.75 | 0.6 | 8.2 to 9.3 |

| Soy-based infant formulas | 6 | 4 months infants | 25.2 | 2.9 | 15.7 to 34.3 |

| Tempeh | 4 | 100 | 27.8 | 4.5 | 15.5 to 34.3 |

| Tofu | 13 | 100 | 34.8 | 5.9 | 9.4 to 79.8 |

| Soy-based cheese | 8 | 50 | 23.8 | 7.4 | 2.9 to 36.2 |

| Miso | 2 | 100 | 14.7 | 0.98 | 13.7 to 15.6 |

| Soy sauce | 9 | 10 mL | 0.16 | 0.004 | 0.16 to 0.17 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).