Submitted:

08 March 2024

Posted:

12 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Take-Home Points

2. Introduction

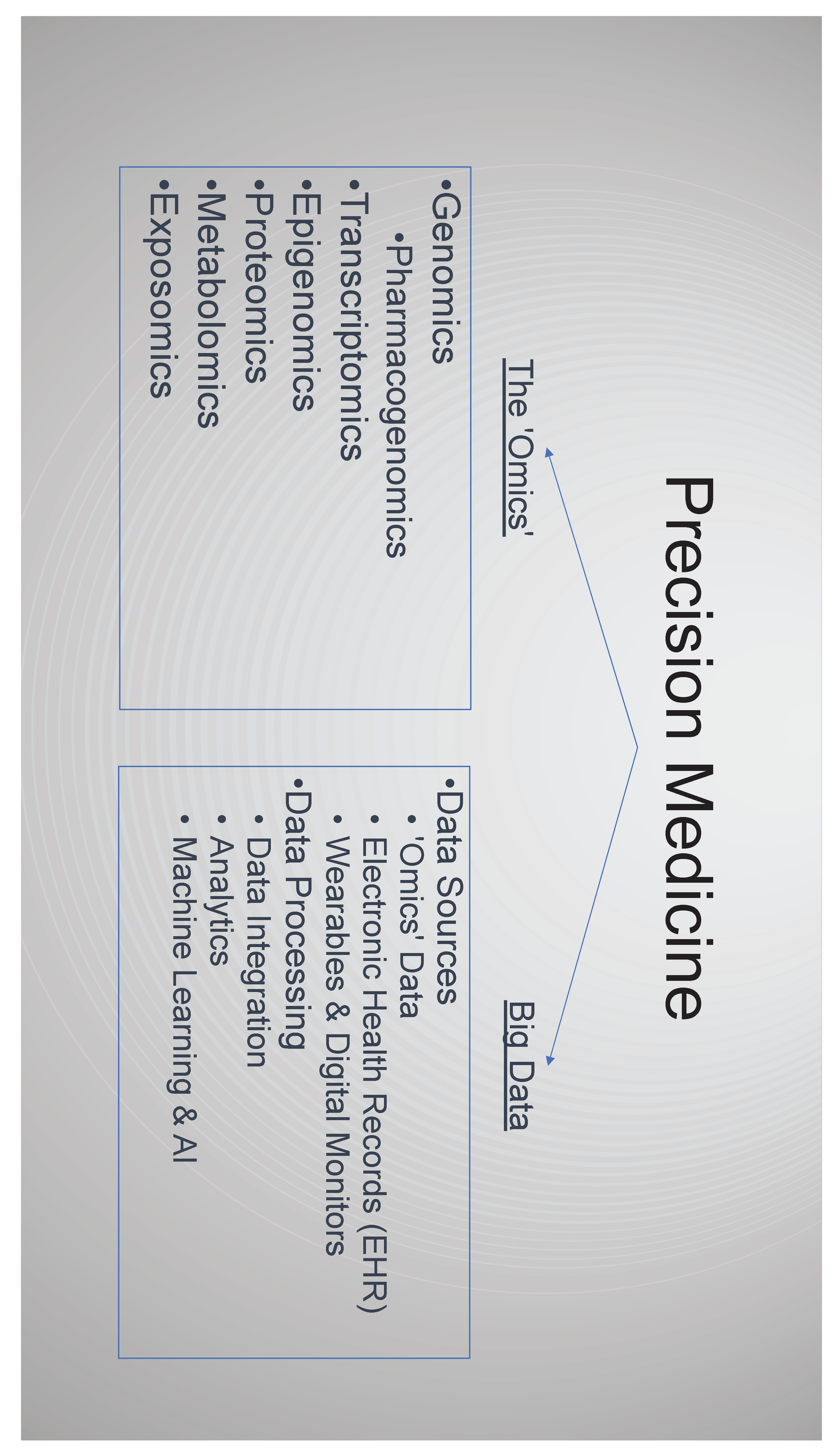

3. The Emergence of -Omics

3.1. Genomics

3.1.1. Molecular Disease Definition

3.1.2. Polygenic Risk Scores

3.1.3. Pharmacogenomics

- Improving drug efficacy. Variation in the cytochrome P450 gene CYP2D6 affects the metabolism and elimination of more than 100 drugs [46]. One of these drugs is the analgesic codeine which is metabolised to the bioactive form morphine. Patients can be classified by their rate of metabolism, with clinical implications for the ultra-rapid metabolisers (UMs) and poor-metabolisers [47], and pharmacogenomic guidance in the summary of product characteristics (SmPC) [48]. Variants for another cytochrome P450 gene, CYP2C19, can also significantly impact clopidogrel metabolism and efficacy with an FDA ‘black box warning’ for those carrying these variants [49].

- Testing at the time of prescribing. Typically, this is a single drug-gene test performed in advance of the prescription decision about to made. For example, in oncology DPYD testing in advance of initiating 5-FU, or in neonatal sepsis testing the RNR1 gene for variants associated with aminoglycoside induced hearing loss[53]. Opportunities for this approach, rapid testing for a single and significant gene-drug interaction, will broaden as molecular diagnostics continue to advance [54]. Although point of care testing (POCT) is already utilised in primary care [55], it is hard to see PGx POCT expand beyond a relatively limited number of indications. In primary care given the range of clinical presentations and prescribing decisions, the feasibility of POCT and the effect of even a modest delay on patient flow, an alternative approach is likely to be better suited.

- Testing patients in advance of prescribing decisions. This is a more distant prospect for primary care but would involve pre-emptively performing a PGx gene panel test for several key drug-gene interactions with the results captured to inform future prescribing decisions. This may involve testing at a separate time to the prescribing decision or triggered by prescribing a single drug on the panel, the specific drug information available to guide that treatment, and the other PGx information available for future reference. An attractive approach is to use existing sequencing data, captured for another indication to identify PGx variants, feasible given as an increasing proportion of the population has had genome or exome sequencing [52].

3.2. Transcriptomics, Epigenomics, Proteomics, Metabolomics & Exposomics

4. Big Data, Data Analytics and AI

4.1. Electronic Health Records

4.2. Digital Technologies Including Wearables

4.3. Prediction Modelling

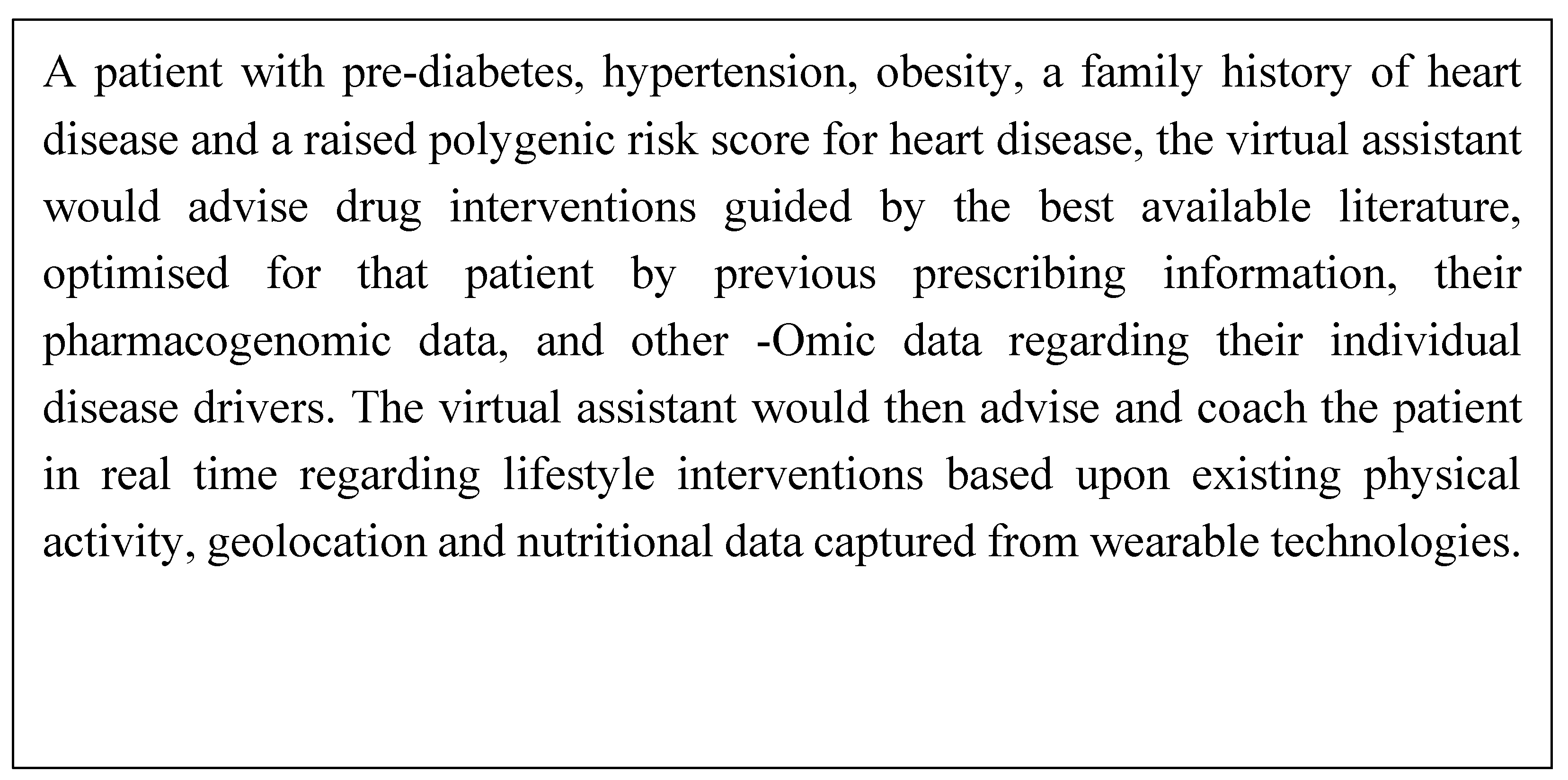

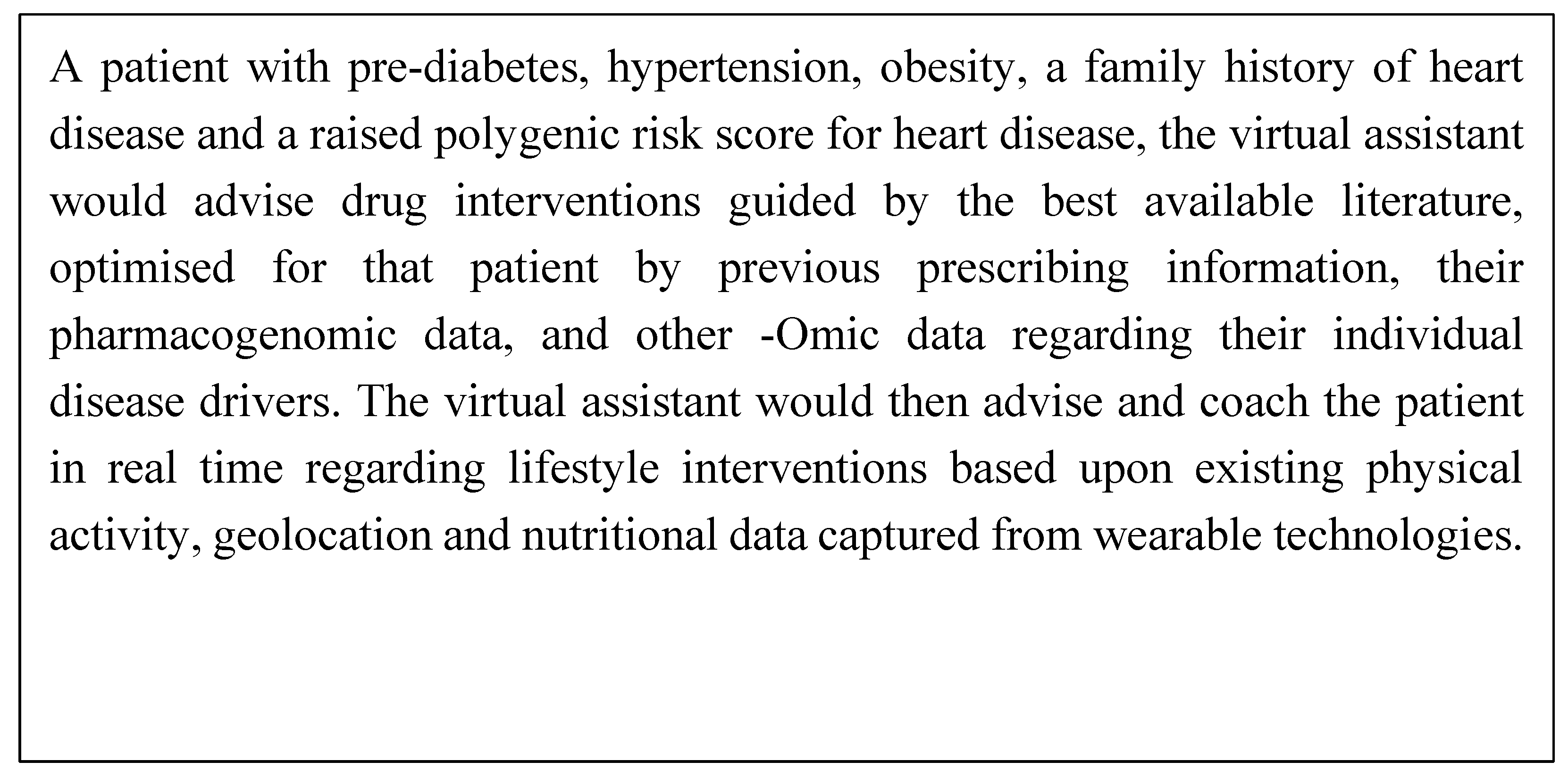

4.4. Artificial Intelligence (AI)

5. Discussion

- Co-development of technologies. To date, healthcare AI tools have often been driven by a focus on the technology and commercial need to find a marker rather than patient and clinician need [97]. Co-development of PM technologies with primary care clinicians, patients and the public, is key to ensure they address the needs and meet the standards and values of society and primary care. With a specific focus on ensuring an evidence base in the primary care setting they are to be deployed, consideration of their impact on continuity of care and how they fit into the consultation, how they will avoid overmedicalisation and increasing health anxiety [97]. It will also be important to ensure that the outputs of PM technologies are delivered in such a way to have optimal impact, effectively inform clinical decision making and create meaningful change in people’s behaviour.

- Real world evidence in the population and setting it is to be deployed. Unrepresentative and biased datasets lead to PM tools that may exacerbate health inequalities. Before implementing PM at scale, health strategies need to ensure that the foundations upon which PM is built: datasets, genetic databases, cohort studies and EHR datasets are appropriately diverse and representative of their intended use population. Endeavours such as the STANDING Together initiative, will be key to encourage representativeness in datasets and ensure transparency in how diversity is reported [116].

- Demonstrating the cost-effectiveness of PM. There is still much uncertainty about the affordability and health economic profile across the range of PM interventions [120]. PM enthusiasts, and frequently policy makers, highlight the potential cost savings of PM: avoiding ill health; promoting health prevention; streamlining diagnostic pathways with earlier diagnoses and making better therapeutic decisions, with less associated waste and adverse events and decreasing the disease burden for the public at large [72,121,122]. However, the evidence for these health system efficiencies is hard to capture, the PM interventions adding an upfront cost with the later benefit harder to measure. For example, currently drugs are prescribed without pharmacogenomic information. Will a net reduction in adverse events and inappropriate prescribing, and thus in health impact and cost, justify the expenditure of pharmacogenomic testing at a population level?

- Data collection sharing and transfer. Much of the potential of PM is dependent upon processing and analysing large amounts of data. Genomic sequencing has advanced at pace, however the availability of information on diverse well-phenotyped individuals has not kept pace, hampering the ability to establish connections between disease and genomics [125]. Optimising the quality of data recorded is key. To achieve this establishing standards for data recording, including clinical vocabulary that is used across care settings, and frameworks to share data, compliant with legal restrictions, that maintain patient privacy and incorporating individual preferences for their data use need to be prioritised.

- Impact upon holistic care. There is concern that the advance of PM interventions may reduce the need for human interaction, with the virtual clinical assistant taking a greater role and affecting the patient doctor relationship. As health care interventions become more personalised, derived from increasingly complex methodologies, the rational for the intervention may become more opaque [110,111]. Will this lack of transparency erode trust and further impact the doctor-patient relationship? Advocates of PM suggest that it will enable better use or resources, bringing together disparate information to support the clinician to make the best decision, thus freeing time for human intelligence and restoring empathy [129]. However, evidence for or against this position needs to be established, with robust primary care based qualitative research incorporating the views of clinicians and patients.

Funding

References

- Osler, W. On the educational value of the medical society. In: equanimitas with Other Addresses to Medical Students, Nurses and Practitioners of Medicine [Internet]. Philadelphia: Blakiston; 1904. p. 343–62. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04615.x.

- Schleidgen, S.; Klingler, C.; Bertram, T.; Rogowski, W.H.; Marckmann, G. What is personalized medicine: sharpening a vague term based on a systematic literature review. BMC Med Ethics. 2013, 14, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyer, M.S.; Widmer, D.; Cohidon, C.; Desvergne, B.; Cornuz, J.; Guessous, I. , et al. Representations of personalised medicine in family medicine: a qualitative analysis. BMC Prim Care. 2022, 23, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginsburg, G.S.; Phillips, K.A. Precision Medicine: From Science To Value. Health Aff Proj Hope. 2018, 37, 694–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Research Council Committee on AF for D a NT of D. The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. In Toward Precision Medicine: Building a Knowledge Network for Biomedical Research and a New Taxonomy of Disease; National Academies Press (US) National Academy of Sciences: Washington (DC), 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, R.S. Electronic Health Records: Then, Now, and in the Future. Yearb Med Inform. 2016, (Suppl 1) (Suppl 1), S48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelhalim, H.; Berber, A.; Lodi, M.; Jain, R.; Nair, A.; Pappu, A. , et al. Artificial Intelligence, Healthcare, Clinical Genomics, and Pharmacogenomics Approaches in Precision Medicine. Front Genet. 2022, 13, 929736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, F.S.; Varmus, H. A New Initiative on Precision Medicine. N Engl J Med. 2015, 372, 793–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Institutes of Health (NIH) All of Us [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Jun 13]. Available online: https://allofus.nih.gov/.

- Joyner, M.J.; Paneth, N. Promises, promises, and precision medicine. J Clin Invest. 3AD, 129, 946–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.P.; Meslin, E.M.; Marteau, T.M.; Caulfield, T. Genomics. Deflating the genomic bubble. Science 2011, 331, 861–2. [Google Scholar]

- Guttmacher, A.E.; Collins, F.S. Genomic Medicine — A Primer. Guttmacher AE, Collins FS, editors. N Engl J Med. 2002, 347, 1512–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, N.; Humphries, S.E.; Gray, H. Personalised medicine in general practice: the example of raised cholesterol. 2018 Feb 1. Available online: https://bjgp.org/content/68/667/68.

- Davies, S.C. Annual Report of the Chief Medical Officer 2016, Generation Genome, 2016 [Internet]. London KW -:-: Department of Health (2017); 2017. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/631043/CMO_annual_report_generation_genome.

- NHS England » Improving Outcomes through Personalised Medicine [Internet]. [cited 2023 Sep 18]. Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/improving-outcomes-through-personalised-medicine/.

- Orrantia-Borunda, E.; Anchondo-Nuñez, P.; Acuña-Aguilar, L.E.; Gómez-Valles, F.O.; Ramírez-Valdespino, C.A. Subtypes of Breast Cancer. In: Mayrovitz HN, editor. Breast Cancer [Internet]. Brisbane (AU): Exon Publications; 2022 [cited 2023 Oct 13]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK583808/.

- Wang, R.C.; Wang, Z. Precision Medicine: Disease Subtyping and Tailored Treatment. Cancers. 2023, 15, 3837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borish, L.; Culp, J.A. Asthma: a syndrome composed of heterogeneous diseases. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol Off Publ Am Coll Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2008, 101, 1–8, quiz 8–11, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuo, K.; Zhou, W.; Wang, Y.; Kanai, M.; Namba, S.; Gupta, R. , et al. Multi-ancestry meta-analysis of asthma identifies novel associations and highlights the value of increased power and diversity. Cell Genomics. 2022, 2, 100212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colicino, S.; Munblit, D.; Minelli, C.; Custovic, A.; Cullinan, P. Validation of childhood asthma predictive tools: A systematic review. Clin Exp Allergy. 2019, 49, 410–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linder, J.E.; Allworth, A.; Bland, H.T.; Caraballo, P.J.; Chisholm, R.L.; Clayton, E.W. , et al. Returning integrated genomic risk and clinical recommendations: The eMERGE study. Genet Med Off J Am Coll Med Genet. 2023, 25, 100006. [Google Scholar]

- NICE. Overview | Familial breast cancer: classification, care and managing breast cancer and related risks in people with a family history of breast cancer | Guidance | NICE [Internet]. NICE; 2017 [cited 2019 May 23]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg164. 23 May.

- Evans, D.G.; Astley, S.; Stavrinos, P.; Harkness, E.; Donnelly, L.S.; Dawe, S. , et al. Improvement in risk prediction, early detection and prevention of breast cancer in the NHS Breast Screening Programme and family history clinics: a dual cohort study [Internet]. Southampton (UK): NIHR Journals Library; 2016 [cited 2023 Sep 24]. (Programme Grants for Applied Research). Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK379488/.

- McHugh, J.K.; ni Raghallaigh, H.; Bancroft, E.; Kote-Jarai, Z.; Benafif, S.; Eeles, R.A. The BARCODE1 study in primary care: Early results targeting men with increased genetic risk of developing prostate cancer—Examining the interim data from a community-based screening program using polygenic risk score to target screening. J Clin Oncol. 2022, 40, (6_suppl). 231–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genomics E, unchanged E field is for validation purposes and should be left, Oxford U contacts, Cambridge U contacts, Cambridge M contacts, Use T of, et al. Genomics plc. 2022 [cited 2023 Sep 24]. Genomics plc announces successful world-first pilot using improved genomic risk assessment in cardiovascular disease prevention in the NHS. Available from: https://www.genomicsplc.com/news/successful-world-first-pilot-using-improved-genomic-risk-assessment-in-cardiovascular-disease-prevention-in-the-nhs/.

- Elliott, J.; Bodinier, B.; Bond, T.A.; Chadeau-Hyam, M.; Evangelou, E.; Moons, K.G.M. , et al. Predictive Accuracy of a Polygenic Risk Score-Enhanced Prediction Model vs a Clinical Risk Score for Coronary Artery Disease. JAMA. 2020, 323, 636–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.D.; Hurson, A.N.; Zhang, H.; Choudhury, P.P.; Easton, D.F.; Milne, R.L. , et al. Assessment of polygenic architecture and risk prediction based on common variants across fourteen cancers. Nat Commun. 2020, 11, 3353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hingorani, A.; Gratton, J.; Finan, C.; Schmidt, A.; Patel, R.; Sofat, R. , et al. Performance of polygenic risk scores in screening, prediction, and risk stratification [Internet]. medRxiv; 2022 [cited 2023 Aug 28]. p. 2022.02.18.22271049. Available from: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.02.18.22271049v2.

- Kiflen, M.; Le, A.; Mao, S.; Lali, R.; Narula, S.; Xie, F. , et al. Cost-Effectiveness of Polygenic Risk Scores to Guide Statin Therapy for Cardiovascular Disease Prevention. Circ Genomic Precis Med. 2022, 15, e003423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, R.; Xu, Z.; Arnold, M.; Ip, S.; Harrison, H.; Barrett, J. , et al. Using Polygenic Risk Scores for Prioritizing Individuals at Greatest Need of a Cardiovascular Disease Risk Assessment. J Am Heart Assoc. 2023, 12, e029296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GWAS to the people. Nat Med. 2018, 24, 1483–1483. [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.R.; Kanai, M.; Kamatani, Y.; Okada, Y.; Neale, B.M.; Daly, M.J. Current clinical use of polygenic scores will risk exacerbating health disparities. Nat Genet. 2019, 51, 584–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Namba, S.; Lopera, E.; Kerminen, S.; Tsuo, K.; Läll, K. , et al. Global Biobank analyses provide lessons for developing polygenic risk scores across diverse cohorts. Cell Genomics. 2023, 3, 100241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sud, A.; Horton, R.H.; Hingorani, A.D.; Tzoulaki, I.; Turnbull, C.; Houlston, R.S. , et al. Realistic expectations are key to realising the benefits of polygenic scores. The BMJ. 2023, 380, e073149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, A.; Mavaddat, N.; Wilcox, A.N.; Cunningham, A.P.; Carver, T.; Hartley, S. , et al. BOADICEA: a comprehensive breast cancer risk prediction model incorporating genetic and nongenetic risk factors. Genet Med Off J Am Coll Med Genet. 2019, 21, 1708–18. [Google Scholar]

- Resnik, D.B.; Vorhaus, D.B. Genetic modification and genetic determinism. Philos Ethics Humanit Med. 2006, 1, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Middlemass, J.B.; Yazdani, M.F.; Kai, J.; Standen, P.J.; Qureshi, N. Introducing genetic testing for cardiovascular disease in primary care: a qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract J R Coll Gen Pract. 2014, 64, e282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollands, G.J.; French, D.P.; Griffin, S.J.; Prevost, A.T.; Sutton, S.; King, S. , et al. The impact of communicating genetic risks of disease on risk-reducing health behaviour: systematic review with meta-analysis. Bmj. i1102–i1102.

- Adminstration UF and DK: Paving the Way for Personalized Medicine: FDA’s ROle in a New Era of Medical product development [Internet]. 2013. Available online: https://www.fdanews.com/ext/resources/files/10/10-28-13-Personalized-Medicine.

- Sadee, W.; Dai, Z. Pharmacogenetics/genomics and personalized medicine. Hum Mol Genet. 2005, 14 Spec No. 2, R207–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, L. An organisation with a memory. Clin Med [Internet]. 2002;2(5 KW-:-). Available online: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/a675/29ad58dbc031e82f33555d071a568a4e5c6c.pdf.

- Overview | Medicines optimisation: the safe and effective use of medicines to enable the best possible outcomes | Guidance | NICE [Internet]. NICE; 2015 [cited 2023 Sep 25]. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng5.

- Sultana, J.; Cutroneo, P.; Trifirò, G. Clinical and economic burden of adverse drug reactions. J Pharmacol Pharmacother. 2013, 4 (Suppl1), S73–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangamornsuksan, W.; Chaiyakunapruk, N.; Somkrua, R.; Lohitnavy, M.; Tassaneeyakul, W. Relationship between the HLA-B*1502 allele and carbamazepine-induced Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2013, 149, 1025–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BNF content published by NICE [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2023 Oct 20]. https://bnf.nice.org.uk.

- Bertilsson, L.; Dahl, M.L.; Dalén, P.; Al-Shurbaji, A. Molecular genetics of CYP2D6: Clinical relevance with focus on psychotropic drugs. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2002, 53, 111–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crews, K.R.; Gaedigk, A.; Dunnenberger, H.M.; Leeder, J.S.; Klein, T.E.; Caudle, K.E. , et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium guidelines for cytochrome P450 2D6 genotype and codeine therapy: 2014 update. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2014/01/25 ed. 2014, 95, 376–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Codeine Phosphate 30mg Tablets - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC) - (emc) [Internet]. [cited 2023 Sep 26]. 2375. Available online: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/2375/smpc#gref.

- Administration UF and, D. FDA Drug Safety Communication: Reduced effectiveness of Plavix (clopidogrel) in patients who are poor metabolizers of the drug | FDA [Internet]. US_FDA; 2010. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/postmarket-drug-safety-information-patients-and-providers/fda-drug-safety-communication-reduced-effectiveness-plavix-clopidogrel-patients-who-are-poor.

- Henricks, L.M.; Lunenburg, C.A.T.C.; Cats, A.; Mathijssen, R.H.J.; Guchelaar, H.J.; Schellens, J.H.M. DPYD genotype-guided dose individualisation of fluoropyrimidine therapy: who and how? – Authors’ reply. Lancet Oncol. 2019, 20, e67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PharmGKB [Internet]. [cited 2023 Sep 26]. PharmGKB. Available online: https://www.pharmgkb.org/.

- RCP London [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2023 Sep 25]. Personalised prescribing: using pharmacogenomics to improve patient outcomes. Available online: https://www.rcp.ac.uk/projects/outputs/personalised-prescribing-using-pharmacogenomics-improve-patient-outcomes.

- McDermott, J.H.; Mahaveer, A.; James, R.A.; Booth, N.; Turner, M.; Harvey, K.E. , et al. Rapid Point-of-Care Genotyping to Avoid Aminoglycoside-Induced Ototoxicity in Neonatal Intensive Care. JAMA Pediatr. 2022, 176, 486–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDermott, J.H.; Burn, J.; Donnai, D.; Newman, W.G. The rise of point-of-care genetics: how the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic will accelerate adoption of genetic testing in the acute setting. Eur J Hum Genet. 2021, 29, 891–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lingervelder, D.; Koffijberg, H.; Kusters, R.; IJzerman, M.J. Point-of-care testing in primary care: A systematic review on implementation aspects addressed in test evaluations. Int J Clin Pract. 2019, 73, e13392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vermeulen, R.; Schymanski, E.L.; Barabási, A.L.; Miller, G.W. The exposome and health: Where chemistry meets biology. Science. 2020, 367, 392–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Topol, E.J. Individualized Medicine from Prewomb to Tomb. Cell. 2014, 157, 241–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baccarelli, A.; Dolinoy, D.C.; Walker, C.L. A precision environmental health approach to prevention of human disease. Nat Commun. 2023, 14, 2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirola, L.; Balcerczyk, A.; Okabe, J.; El-Osta, A. Epigenetic phenomena linked to diabetic complications. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2010/11/04 ed. 2010, 6, 665–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Wang, L.; Chen, D.; Feng, M.; Lu, Y.; Chen, R. , et al. The application of proteomics in the diagnosis and treatment of bronchial asthma. Ann Transl Med. 2020, 8, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, Z.; Mohamed, K.; Zeeshan, S.; Dong, X. Artificial intelligence with multi-functional machine learning platform development for better healthcare and precision medicine. Database J Biol Databases Curation. 2020, 2020, baaa010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leon-Mimila, P.; Wang, J.; Huertas-Vazquez, A. Relevance of Multi-Omics Studies in Cardiovascular Diseases. Front Cardiovasc Med [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2023 Dec 8];6. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcvm.2019.00091.

- Wolf, A.; Dedman, D.; Campbell, J.; Booth, H.; Lunn, D.; Chapman, J. , et al. Data resource profile: Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD) Aurum. Int J Epidemiol. 2019, 48, 1740–1740g. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, C.; Yang, X.; Chen, A.; Smith, K.E.; PourNejatian, N.; Costa, A.B. A Study of Generative Large Language Model for Medical Research and Healthcare [Internet]. arXiv; 2023 [cited 2023 Oct 25]. Available online: http://arxiv.org/abs/2305.13523.

- Dzau, V.J.; Ginsburg, G.S. Realizing the Full Potential of Precision Medicine in Health and Health CarePotential of Precision Medicine in Health and Health CarePotential of Precision Medicine in Health and Health Care. JAMA. 2016, 316, 1659–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, L.A.; Nelder, J.R.; Fryer, J.M.; Alsop, P.H.; Geary, M.R.; Prince, M. , et al. Public opinion on sharing data from health services for clinical and research purposes without explicit consent: an anonymous online survey in the UK. BMJ Open. 2022, 12, e057579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, S. Pause plans for data sharing contract to ensure trust and patient consent, plead doctors’ leaders. BMJ. 2023, 383, p2674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parr, E. UK Biobank writes to all GP practices requesting they share patient data [Internet]. Pulse Today. 2023 [cited 2023 Oct 17]. 2023. Available online: https://www.pulsetoday.co.uk/news/technology/uk-biobank-writes-to-all-gp-practices-requesting-they-share-patient-data/.

- Izmailova, E.S.; Wagner, J.A.; Perakslis, E.D. Wearable Devices in Clinical Trials: Hype and Hypothesis. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2018, 104, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Topol Review [Internet]. [cited 2023 Sep 18]. Available online: https://topol.hee.nhs.uk/the-topol-review/.

- McGinnis, J.M.; Williams-Russo, P.; Knickman, J.R. The Case For More Active Policy Attention To Health Promotion. Health Aff (Millwood). 2002, 21, 78–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K.B.; Wei, W.; Weeraratne, D.; Frisse, M.E.; Misulis, K.; Rhee, K. , et al. Precision Medicine, AI, and the Future of Personalized Health Care. Clin Transl Sci. 2021, 14, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemingway, H.; Croft, P.; Perel, P.; Hayden, J.A.; Abrams, K.; Timmis, A. , et al. Prognosis research strategy (PROGRESS) 1: a framework for researching clinical outcomes. Bmj. 2013, 346, e5595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, D.R. Regression Models and Life-Tables. J R Stat Soc Ser B Methodol. 1972, 34, 187–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasan, R.S.; Beiser, A.; Seshadri, S.; Larson, M.G.; Kannel, W.B.; D’Agostino, R.B. , et al. Residual Lifetime Risk for Developing Hypertension in Middle-aged Women and MenThe Framingham Heart Study. JAMA. 2002, 287, 1003–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanis, J.A.; Johnell, O.; Oden, A.; Johansson, H.; McCloskey, E. FRAX and the assessment of fracture probability in men and women from the UK. Osteoporos Int J Establ Result Coop Eur Found Osteoporos Natl Osteoporos Found USA. 2008, 19, 385–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dent, E.; Kowal, P.; Hoogendijk, E.O. Frailty measurement in research and clinical practice: A review. Eur J Intern Med. 2016, 31, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hippisley-Cox, J.; Coupland, C.; Brindle, P. Development and validation of QRISK3 risk prediction algorithms to estimate future risk of cardiovascular disease: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2017, 357, j2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kingston, M.; Griffiths, R.; Hutchings, H.; Porter, A.; Russell, I.; Snooks, H. Emergency admission risk stratification tools in UK primary care: a cross-sectional survey of availability and use. Br J Gen Pract. 2020, 70, e740–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadakis, G.Z.; Karantanas, A.H.; Tsiknakis, M.; Tsatsakis, A.; Spandidos, D.A.; Marias, K. Deep learning opens new horizons in personalized medicine. Biomed Rep. 2019, 10, 215–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, S.F.; Reps, J.; Kai, J.; Garibaldi, J.M.; Qureshi, N. Can machine-learning improve cardiovascular risk prediction using routine clinical data? PLOS ONE. 2017, 2017. 12, e0174944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callender, T.; Imrie, F.; Cebere, B.; Pashayan, N.; Navani, N.; Schaar M van, d.e.r. , et al. Assessing eligibility for lung cancer screening using parsimonious ensemble machine learning models: A development and validation study. PLOS Med. 2023, 20, e1004287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montazeri, M.; Montazeri, M.; Bahaadinbeigy, K.; Montazeri, M.; Afraz, A. Application of machine learning methods in predicting schizophrenia and bipolar disorders: A systematic review. Health Sci Rep. 2022, 6, e962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, S.F.; Vaz, L.; Qureshi, N.; Kai, J. Prediction of premature all-cause mortality: A prospective general population cohort study comparing machine-learning and standard epidemiological approaches. PloS One. 2019, 14, e0214365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Topol, E.J. As artificial intelligence goes multimodal, medical applications multiply. Science. 2023, 381, adk6139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer-Williams, A. Microsoft and Epic expand AI collaboration to tackle current healthcare needs [Internet]. htn. 2023 [cited 2023 Aug 29]. Available from: Available from: https://htn.co.uk/2023/08/23/microsoft-and-epic-expand-ai-collaboration-to-tackle-current-healthcare-needs/.

- Lim, J.I.; Regillo, C.D.; Sadda, S.R.; Ipp, E.; Bhaskaranand, M.; Ramachandra, C. , et al. Artificial Intelligence Detection of Diabetic Retinopathy. Ophthalmol Sci. 2022, 3, 100228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poplin, R.; Varadarajan, A.V.; Blumer, K.; Liu, Y.; McConnell, M.V.; Corrado, G.S. , et al. Prediction of cardiovascular risk factors from retinal fundus photographs via deep learning. Nat Biomed Eng. 2018, 2, 158–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, C.Y.; Ran, A.R.; Wang, S.; Chan, V.T.T.; Sham, K.; Hilal, S. , et al. A deep learning model for detection of Alzheimer’s disease based on retinal photographs: a retrospective, multicentre case-control study. Lancet Digit Health. 2022, 4, e806–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Pinto, A.; Ravikumar, N.; Attar, R.; Suinesiaputra, A.; Zhao, Y.; Levelt, E.; et al. Predicting myocardial infarction through retinal scans and minimal personal information. Nat Mach Intell. 2022, 4, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, S.K.; Romero-Bascones, D.; Cortina-Borja, M.; Williamson, D.J.; Struyven, R.R.; Zhou, Y. Retinal Optical Coherence Tomography Features Associated With Incident and Prevalent Parkinson Disease. Neurology [Internet]. 2023 Aug 21 [cited 2023 Aug 31]; Available from: https://n.neurology.org/content/early/2023/08/21/WNL.0000000000207727.

- Scheetz, J.; Rothschild, P.; McGuinness, M.; Hadoux, X.; Soyer, H.P.; Janda, M. , et al. A survey of clinicians on the use of artificial intelligence in ophthalmology, dermatology, radiology and radiation oncology. Sci Rep. 2021, 11, 5193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du-Harpur, X.; Watt, F.M.; Luscombe, N.M.; Lynch, M.D. What is AI? Applications of artificial intelligence to dermatology. Br J Dermatol. 2020, 183, 423–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escalé-Besa, A.; Yélamos, O.; Vidal-Alaball, J.; Fuster-Casanovas, A.; Miró Catalina, Q.; Börve, A. , et al. Exploring the potential of artificial intelligence in improving skin lesion diagnosis in primary care. Sci Rep. 2023, 13, 4293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, K.; Hurault, G.; Arulkumaran, K.; Williams, H.C.; Tanaka, R.J. EczemaNet: Automating Detection and Severity Assessment of Atopic Dermatitis. In: Liu M, Yan P, Lian C, Cao X, editors. Machine Learning in Medical Imaging. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2020. p. 220–30. (Lecture Notes in Computer Science).

- Ambient Clinical Intelligence | Automatically Document Care | Nuance [Internet]. [cited 2023 Oct 4]. Available online: https://www.nuance.com/healthcare/ambient-clinical-intelligence.html.

- Mistry, P. Artificial intelligence in primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2019, 69, 422–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ChatGPT [Internet]. [cited 2023 Oct 5]. Available from: https://chat.openai.com.

- Bard - Chat Based AI Tool from Google, Powered by PaLM 2 [Internet]. [cited 2023 Oct 20]. Available from: https://bard.google.com.

- Yang, Z.; Li, L.; Lin, K.; Wang, J.; Lin, C.C.; Liu, Z. The Dawn of LMMs: Preliminary Explorations with GPT-4V(ision) [Internet]. arXiv; 2023 [cited 2023 Oct 16]. Available from: http://arxiv.org/abs/2309.17421.

- Magavern, E.F.; Smedley, D.; Caulfield, M.J. Factor V Leiden, oestrogen and multimorbidity association with venous thromboembolism in a British-South Asian Cohort. iScience [Internet]. 2023 Aug 31 [cited 2023 Sep 20];0(0). Available from: https://www.cell.com/iscience/abstract/S2589-0042(23)01872-2.

- Pandit, J.A.; Radin, J.M.; Quer, G.; Topol, E.J. Smartphone apps in the COVID-19 pandemic. Nat Biotechnol. 2022, 40, 1013–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Generative AI Country Automation [Internet]. [cited 2023 Oct 5]. Available from: http://ceros.mckinsey.com/generative-ai-country-automation.

- Pause Giant AI Experiments: An Open Letter [Internet]. Future of Life Institute. [cited 2023 Oct 20]. Available from: https://futureoflife.org/open-letter/pause-giant-ai-experiments/.

- Sanderson, S.; Zimmern, R.; Kroese, M.; Higgins, J.; Patch, C.; Emery, J. How can the evaluation of genetic tests be enhanced? Lessons learned from the ACCE framework and evaluating genetic tests in the United Kingdom. Genet Med Off J Am Coll Med Genet. 2005, 7, 495–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ACCE Model Process for Evaluating Genetic Tests | CDC [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2023 Oct 20]. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/genomics/gtesting/acce/index.htm.

- WHO outlines considerations for regulation of artificial intelligence for health [Internet]. [cited 2023 Oct 25]. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/19-10-2023-who-outlines-considerations-for-regulation-of-artificial-intelligence-for-health.

- About the AI and Digital Regulations Service - AI regulation service - NHS [Internet]. [cited 2023 Oct 25]. Available online: https://www.digitalregulations.innovation.nhs.uk/about-this-service/.

- Vries A, d.e. The growing energy footprint of artificial intelligence. Joule [Internet]. 2023 Oct 10 [cited 2023 Oct 12];0(0). 2023. Available online: https://www.cell.com/joule/abstract/S2542-4351(23)00365-3.

- Topol, E.J. High-performance medicine: the convergence of human and artificial intelligence. Nat Med. 2019, 25, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashimoto, D.A.; Witkowski, E.; Gao, L.; Meireles, O.; Rosman, G. Artificial Intelligence in Anesthesiology: Current Techniques, Clinical Applications, and Limitations. Anesthesiology. 2020, 132, 379–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, H.; Liu, X.; Zariffa, N.; Morris, A.D.; Denniston, A.K. Health data poverty: an assailable barrier to equitable digital health care. Lancet Digit Health. 2021, 3, e260–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fry, A.; Littlejohns, T.J.; Sudlow, C.; Doherty, N.; Adamska, L.; Sprosen, T. , et al. Comparison of Sociodemographic and Health-Related Characteristics of UK Biobank Participants With Those of the General Population. Am J Epidemiol. 2017/06/24 ed. 2017, 186, 1026–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arora, A.; Alderman, J.E.; Palmer, J.; Ganapathi, S.; Laws, E.; McCradden, M.D. , et al. The value of standards for health datasets in artificial intelligence-based applications. Nat Med. 2023, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Tobias, D.K.; Merino, J.; Ahmad, A.; Aiken, C.; Benham, J.L.; Bodhini, D. , et al. Second international consensus report on gaps and opportunities for the clinical translation of precision diabetes medicine. Nat Med. 2023, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Ganapathi, S.; Palmer, J.; Alderman, J.E.; Calvert, M.; Espinoza, C.; Gath, J. , et al. Tackling bias in AI health datasets through the STANDING Together initiative. Nat Med. 2022, 28, 2232–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, A.L.; Prince, C.; Fitzgerald, G.; Hanson, A.; Downing, J.; Reynolds, J. , et al. Implementation of genotype-guided dosing of warfarin with point-of-care genetic testing in three UK clinics: a matched cohort study. BMC Med. 2019, 17, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogaka, J.J.O.; James, S.E.; Chimbari, M.J. Leveraging implementation science to improve implementation outcomes in precision medicine. Am J Transl Res. 2020, 12, 4853–72. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Khoury, MJ. No Shortcuts on the Long Road to Evidence-Based Genomic Medicine. JAMA. 2017, 318, 27–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Anothaisintawee, T.; Butani, D.; Wang, Y.; Zemlyanska, Y.; Wong, C.B.N. Assessing the cost-effectiveness of precision medicine: protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2022, 12, e057537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathur, S.; Sutton, J. Personalized medicine could transform healthcare. Biomed Rep. 2017, 7, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, B.J.; Flockhart, D.A.; Meslin, E.M. Creating incentives for genomic research to improve targeting of therapies. Nat Med. 2020, 10, 1289–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasad, V.; De Jesús, K.; Mailankody, S. The high price of anticancer drugs: origins, implications, barriers, solutions. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2017, 14, 381–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, A.L.; Ziesche, S.; Yancy, C.; Carson, P.; D’Agostino, R.; Ferdinand, K. , et al. Combination of Isosorbide Dinitrate and Hydralazine in Blacks with Heart Failure. N Engl J Med. 2004, 351, 2049–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linder, J.E.; Bastarache, L.; Hughey, J.J.; Peterson, J.F. The Role of Electronic Health Records in Advancing Genomic Medicine. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2021, 22, 219–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lind, S. NHS England could take co-data controller responsibility for GP patient records [Internet]. Pulse Today. 2023 [cited 2023 Oct 17]. https://www.pulsetoday.co.uk/news/breaking-news/nhs-england-could-take-co-data-controller-responsibility-for-gp-patient-records/.

- NHS Long Term Plan » Overview and summary [Internet]. [cited 2023 Nov 3]. Available online: https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/online-version/overview-and-summary/.

- Syal, R. Abandoned NHS IT system has cost £10bn so far. The Guardian [Internet]. 2013 Sep 17 [cited 2023 Nov 3]; Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/society/2013/sep/18/nhs-records-system-10bn.

- Topol, E.J. Machines and empathy in medicine. The Lancet. 2023, 402, 1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).