1. Introduction

Aquatic bodies are essential for sustaining life of aquatic and terrestrial living things and they are a major economical and touristic resource, therefore, they generate a special attention for a proper monitoring and protection. Most ecosystem are highly dynamic in terms of both their species composition and abundances and their functioning. The abiotic and biotic elements of rivers and streams watersheds are described as having pronounced ecological unpredictability, particularly since the industrial age began and now – another challenge as Covid-19 pandemic. The diversity and structure of microbial communities are inevitably impacted by environmental stress that reveals some of the pollution-associated risks to the health of natural ecosystems as well as its capacity for resilience under the impact of selective pressure from wastewater plants effluents.

The overexploitation of water during the anthropic activities conducted to water depletion and/or pollution which triggered a warning sign on a proper water resource management. Furthermore, wastewaters are known sources of chemical pollutants which mainly originate from human activities and the private consumption of pharmaceuticals results in a continuous emission of parent and metabolized molecules that flow into domestic wastewater [

1,

2].

Wastewater treatment plants (WWTP) are part of this water resource management plan to reduce chemical or microbiological pollution [

3]. Water, besides being a strategic resource for society, is an important vector in spreading infectious diseases over large areas. Certainly, it was the case of Covid-19 pandemic when water management was a major factor in SARS-CoV-2 virus spreading as well as its associated infections [

4].

Despite the primary mechanism of SARS-CoV-2 transmission was via respiratory droplets that people cough, sneeze or exhale, an increasing number of articles reported the detection of this virus in feces of Covid-19 patients that may remain viable, infectious and/or able to replicate in stool under certain conditions. In the same time, during the epidemic peak, a massive use of pharmaceuticals, most of which had never been used before in such amount, has occurred, causing a sudden increase in the concentrations of these drugs in wastewaters and consecutively an increased chance of microorganism’s resistance [

1,

5]. Correlating the presence of the virus in both wastewater and faecal matter and also the presence of faecal matter in wastewater, changes in the microbial structures in sewage treatment plants are inevitable.

The origin point of Covid-19 pandemic was China, Wuhan province, had a very fast progression reaching European countries in a just few months, when by March 2020 all European countries confirmed the infection presence. The very fast virus worldwide spreading took be surprise the medical authorities which, in response, im-posed long periods of harsh social measures, such as lockdowns, to minimize the spread of the virus.

In Romania, the Covid-19 pandemic steadily spread from second part of 2020, reaching an infection peak in the middle of 2021. Covid-19 spreading rate into population was mainly monitored by hospital units, but there were reports that it could be efficiently monitored by Covid-19 quantification in domestic wastewater [

6]. Furthermore, many studies have shown that wastewater-based epidemiology has become a practical approach for monitoring Covid-19 outbreaks. At the same time, microbiological analyses of wastewater could provide indirect data of Covid-19 progression among certain human communities. The concept of wastewater-based epidemiology indicates that wastewater is one of the main ways of introduction and transmission of antimicrobials and resistant microorganisms in the environments and it also shows the correlation between them [

3,

7].

Large amounts of wastewater, including those from hospital units, have been daily generated into the sewage system from where they reached as influents the municipal WWTPs [

6,

8]. The modern WWTPs could process large quantities of wastewater (up to 440 000 000m3/year) and subsequently help to maintain a safe urban development and a clean environment. Consequently, it is necessary for WWTPs to have an efficient and stable physco-chemical and microbiological treatment steps. The microbiological treatment step relies on activated sludge, which is a unique microbial community with a high bacterial diversity and high concentration of bio-mass based on wastewater pollutants composition [

9]. Any impairment of wastewater treatment steps decreases the effluents quality thus posing high risk to downstream users and environment, especially to the aquatic systems [

10].

There is a clear link between monitoring Covid-19 presence and spreading rate in wastewater and the indirect effect of Covid-19 on microbial populations due to its medical treatment in hospitals. Unfortunately, pathogenic microorganisms and pharmaceutical compounds, abundantly present in hospital wastewaters, are partially bio-degraded by the microbial communities from the activated sludge during a biological treatment step. In addition, the activated sludge is a hot spot for selection and dissemination of bacterial resistance under the pressure of chemicals.

World Health Organization acknowledged the bacterial multidrug resistance as one humanity greater challenge, especially of ESKAPE group, composed by Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and species of the genus Enterobacter spp. 50% of patients with severe SARS-CoV-2 infections were reported to develop bacterial coinfections, especially with bacteria from ESKAPE that have been isolated from several extra-hospital reservoirs such as various water sources, including wastewater [

11,

12].

Aquatic environments under anthropic pressure have been good incubators for antibiotics and antibiotic resistance genes. In addition to them, municipal WWTPs are also major incubators for antibiotic resistant bacteria and antibiotic resistance genes due to the fact that most antibiotics used in medical systems are excreted via urine and feces, stimulating the bacterial resistance mechanisms [

13].

The COVID-19 pandemic offered a unique opportunity to study shifts in environmental antibiotic resistance that could be associated with the changes in disinfectant and/or antibiotic usage patterns, coinfections, or other behaviors. COVID-19 cases positively correlated with the disinfectants/antiseptics group of ARGs and negatively correlated with the sulfonamide and aminoglycoside resistance classes. Discussion is provided regarding the correspondence of these observations with antibiotic prescription pattern changes during the study period. Putative waterborne pathogens were identified, which is of potential interest for understanding the prevalence of community coinfections [

14]

As Surleac shows in his studies, the great majority of fecal bacteria strains isolated from effluent, influent and clinical samples were multidrug resistant and they especially are resistant to the same antibiotics (beta-lactams) [

15].

Upon entering the hospital wastewater, antibiotic residues can adversely affect nature biota at multiple trophic levels, thereby exacerbating antibiotic resistance genes pollution in water and the ESKAPE group may be a relevant component of drug resistant distribution [

8]. Unfortunately, antibiotics released from clinical units reached the municipal sewage system and therefore they could be found into an aquatic environment where they were further in contact with to opportunistic pathogens, enhancing the bacterial resistance mechanism [

16]. Recent studies (Popa L. and colab. 2021) showed that the isolation of the same clone from both hospital and WWTP influent and effluent after chlorination suggests the highly adaptive potential of the clone [

17]. In addition, to pharmaceutical compounds, also could reach the sewage systems through excreted feces from infected people.

Municipal WWTPs reduce the abiotic and biotic pollution by three main treatment steps such as primary treatment to reduce the solid matter, secondary biological treatment to break down the organic waste matter and tertiary treatment to remove pathogenic organisms through chlorine disinfection.

In spite of progress in water treatment systems, the occurrence of waterborne infections remained a worldwide hot issue [

18,

19]. The enteric bacteria are the most commonly used bacterial indicator groups of fecal pollution, these being used as indicators to evaluate the quality of wastewater influents, effluents and rivers. The evaluation of faecal bacteria dynamics in sewage systems, including the wastewater treatment facilities, and their resistance and resilience to pharmaceutical compounds is essential for establishing a potential impact of con-trolled or uncontrolled wastewater discharges on the aquatic environment. Pathogenic or potentially pathogenic faecal bacteria in aquatic ecosystems could be used as warning bioindicators of a major pollution with a public health harmful potential, especially when they are resistant to pharmaceutical compounds widely used in the Covid-19 pandemic. [

6].

This work analyzed the microbiological modifications induced in influent and effluent wastewaters from three WWTPs in Romania during ante-Covid-19 and the peak period of the Covid-19 pandemic.

The centralized sewage systems that were studied are implemented in regions with moderate to high socio-economic capacity that have experienced a large number of cases of COVID-19. The aim of this study was to highlight the conditions that indicate an urgent need for monitoring programs and adapted risk assessments of SARS-Cov-2 in wastewater, which can help in the early detection and limitation of future outbreaks of viral diseases.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling

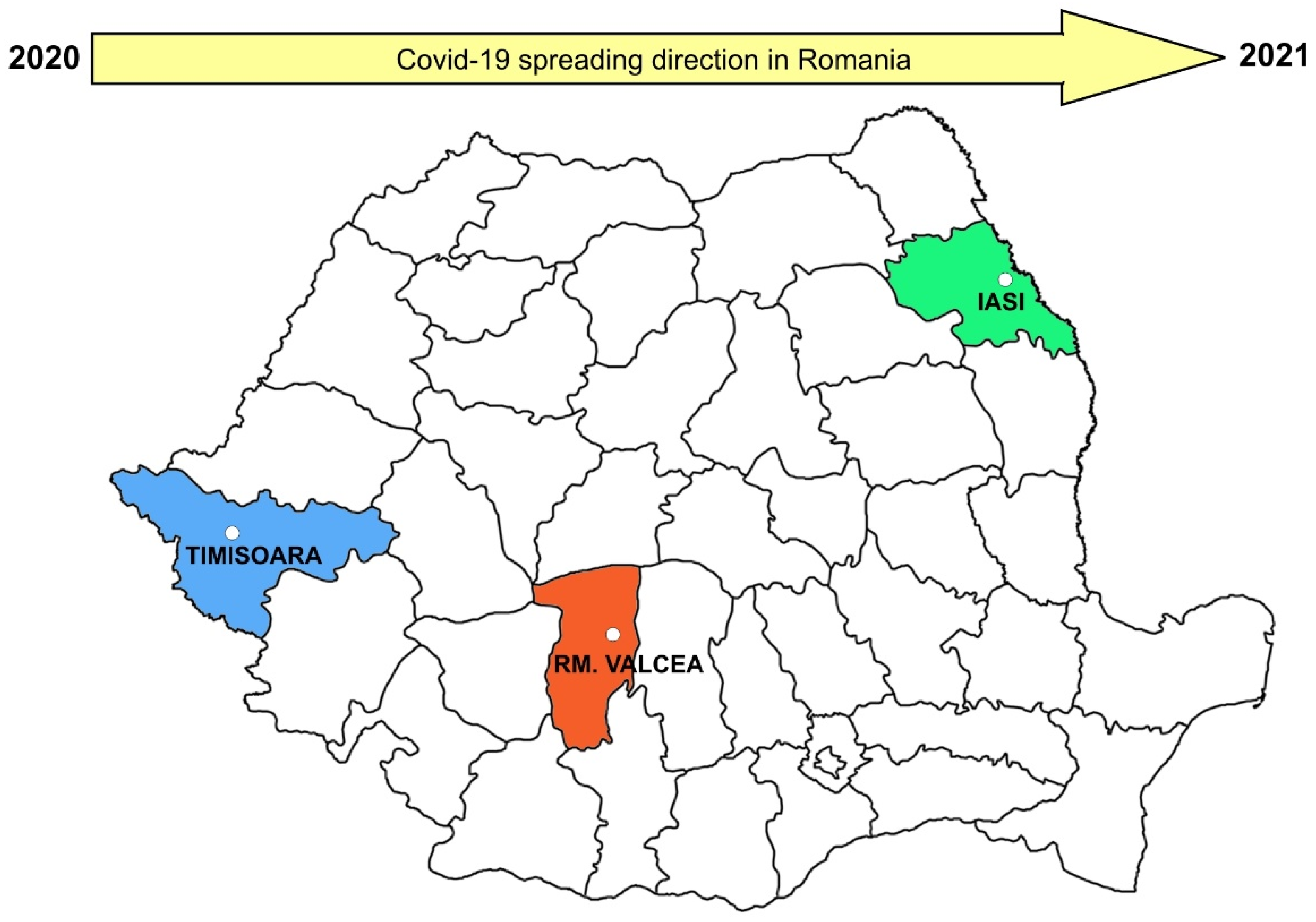

Three areas in Romania were selected (

Figure 1). These are urban agglomerations with population between 150,000 and 800,000 inhabitants: Iasi (800,000 inhabitants), Rm. Valcea (150,000 inhabitants), and Timisoara (500,000 inhabitants). The sampling period was carried out in three annual campaigns and covered the evolution of COVID-19 pandemic in Romania (2019-2021). The sampling campaigns were grouped into two important periods: the ante-Covid-19 pandemic (April 2019-September 2020) and a peak period for Covid-19 (October 2020-June 2021).

Influent and effluent samples were collected from each WWTP and surface water samples were collected from the. river into which each WWTP discharges: Bahlui River (Iasi), Olt River (Rm. Valcea) and Bega River (Timisoara). A volume of 1L of each water type was collected in replicates from each point of interest. The samples were taken in sterile containers in accordance with ISO 19458 [

20] and then transported within a maximum of 24 hours in conditions of 4-5°C.

2.2. Microbiological Analysis

The Most Probable Number Method (MPN - IDEXX) was used in duplicate for quantification of coliform bacteria densities [

21]. The samples were analyzed on decimal dilutions (up to 10

−6) from which a homogenous suspension was prepared from 100 mL of sample with Colilert-18 medium (Idexx Laboratories, Inc, Westbrook, US).

The obtain suspension was distributed in Idexx bags 49/48 wells, one form detecting the number of total coliform bacteria and another for the quantification of fecal coliforms. An incubation time of 18-22 hours was needed for densities quantification, with specific temperature for total coliforms (36 ± 2°C) and fecal coliforms (44.5°C). All steps were controlled by using positive controls such as Escherichia coli (ATCC25922) (Sharlab SL, Barcelona, Spain), Citrobacter freundii (ATCC 8090) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, US) and Klebsiella aerogenes (ATCC 13048) (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, US) and negative control such as Enterococcus faecalis (ATCC 29212) (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, US).

The membrane filtration method [

22] was performed for detection and enumeration of enterococcus. The presumption test required filtering the sample through a membrane with 45 µm pore diameter and placing it on Slanetz and Bartley agar (Oxoid, Basinstoke, England) plates. The membranes on which the reddish-brown colonies grew after 48 hours at 36 ± 2°C were transferred on Bile Aesculine Agar (Sharlab SL, Barcelona, Spain) that were incubated for 2 hours at 44°C.

Enterococcus faecalis (ATCC 29212) (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, US) and

Escherichia coli (ATCC25922) (Sharlab SL, Barcelona, Spain) were used for control the technique efficiency.

Sample dilutions were made with sterile distilled water, which was also used for the blank control.

All finally results were reported 100 mL: MPN/ 100 mL for total and fecal coliforms and CFU (colony forming units)/ 100 mL for enterococcus density.

2.3. Statistically Analysis

The statistical results were carried out using ANOVA function of Microsoft excel.

3. Results and Discussion

The sampling points were analyzed from West to East of Romania base on the Covid-19 progression. The Covid-19 incidence average was around 5 in the city of Timisoara (West side of Romania) and 3 for Rm. Valcea (central part of Romania) and Iasi (Eastern part of Romania) (

Figure 1).

The Covid-19 pandemic was also associate with digestive issues in human infected with SARS-CoV-2 during infection. The binding of the virus to the proteases of the intestinal tract led to the production of inflammatory factors secondary to the viral infection that were potentially harmful to the intestinal barrier. The imbalances of the intestinal microbiota from secondary Covid-19 infections [

23] have caused an increase in the number of hospitalized patients with both SARS-CoV-2 infections and secondary bacterial infections. A clinical research study from Romania demonstrated that both the number of hospitalized patients and the number of bacterial isolates was lower before the emergence and installation of the Covid-19 pandemic. This phenomenon also led to the excretion and dissemination of bacteria from secondary infections in the wastewater and then in the receiving aquatic environments. [

24].

In addition, the Covid-19 treatment procedures heavily relied on antibiotic and biocides chemical which in fact disturbed the balance of intestinal bacterial communities, including generation of antibiotic resistant bacteria. Even before the establishment of SARS-CoV-2 infections the bacterial resistance was a global problem, after this period the resistance rate of pathogenic microorganisms isolated from both clinical cases and the environment increased. The pathogenic microorganism from patients were released into the sewage system and therefore could spread their resistance during the steps of WWTP. The influence of disinfection processes and specific infection treatments with antibiotics caused the dissemination of antibiotic resistance. The antibiotics present in wastewater can exert selective pressure and promote the emergence of antibiotic resistance genes and it can change in microbial community structures [

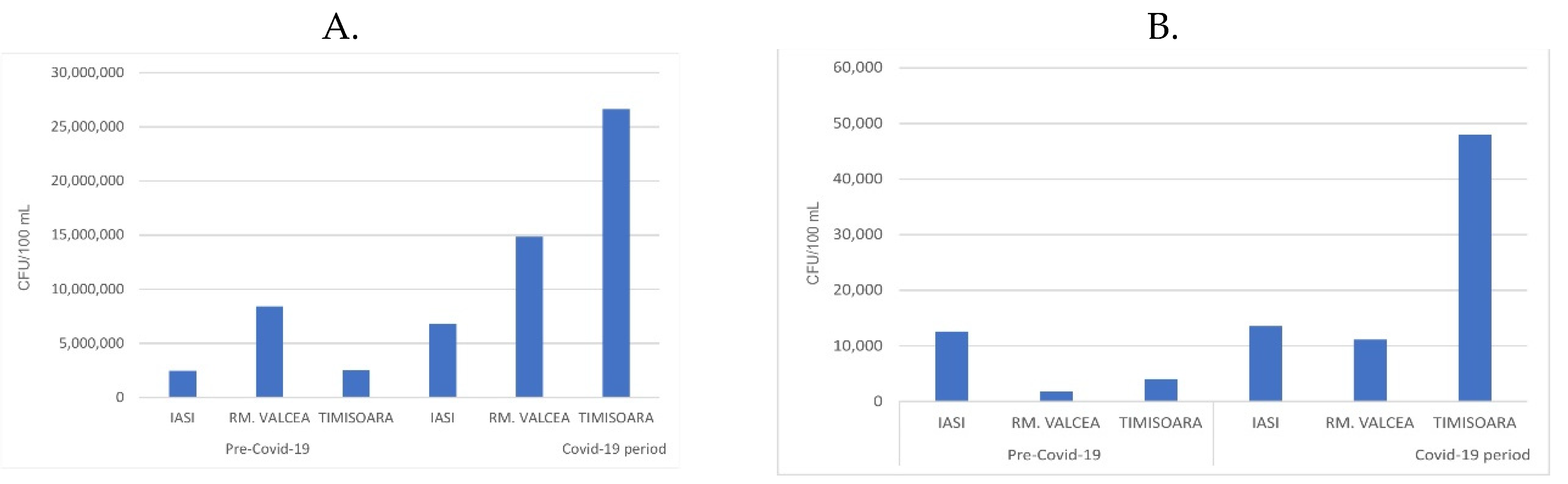

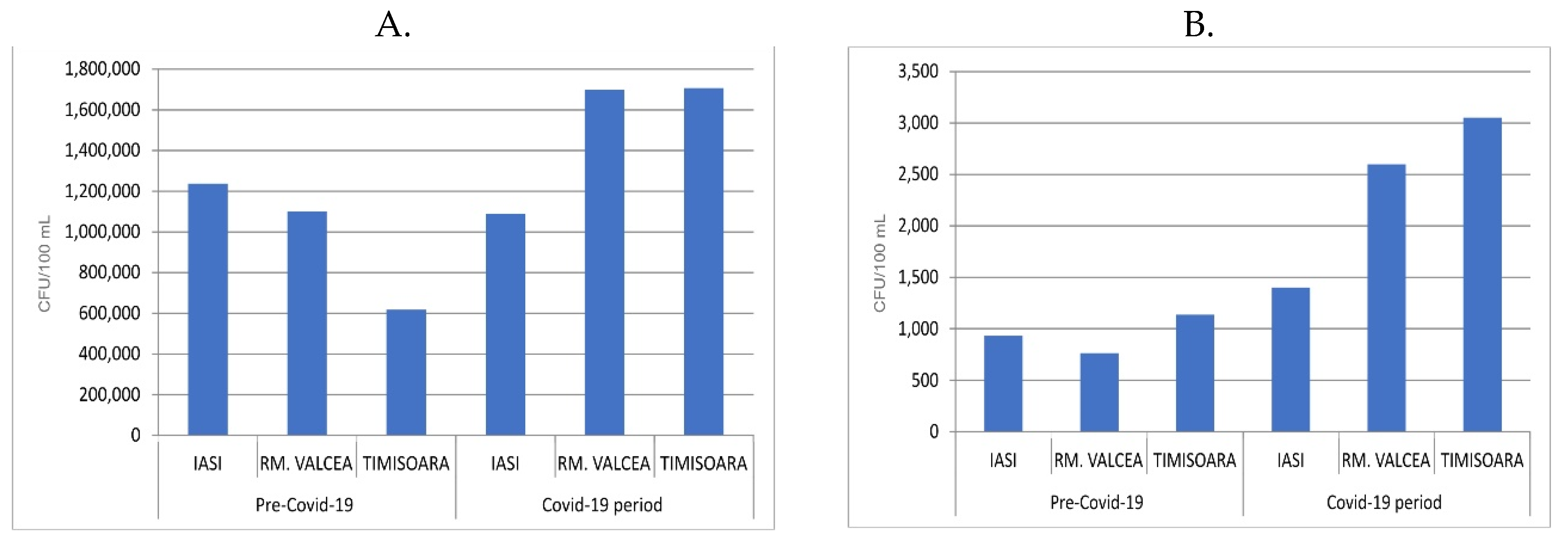

25]. The fecal bacteria from the sewage systems, especially in the WWTP influents, increased during Covid-19 progression compared to the period before Covid-19 pandemic (

Figure 2A). The ratio between fecal from Covid-19 vs ante-Covid-19 was similar in Iasi (2.8 ration Covid-19/ante-Covid-19) and Rm. Valcea (2 ration Covid-19/ante-Covid-19). Interestingly, in Timisoara, a city with higher Covid-19 incidence, compared to Iasi and Rm. Valcea, the fecal ration between Covid-19 and ante-Covid-19 increased to 10.8.

The WWTP efficiency in removing the bacterial load from influent (around 1.5 x 10

7 CFU/100 mL) to effluent (around 1.5 x 10

4 CFU/100 mL) was very high by decreasing the bacterial magnitude range load with 1 x 10

3 CFU/100 mL. In spite of this significant reduction of the bacterial load, the fecal presence in effluent was still substantial and their fecal ratio between Covid-19 and ante-Covid-19 was up to 6 for Rm. Valcea and up to 13 for Timisoara, but decreased almost to 1 for Iasi. (

Figure 2B). The overall tendency of fecal presence was to be increased during Covid-19 pandemic compared to ante-Covid-19 progression.

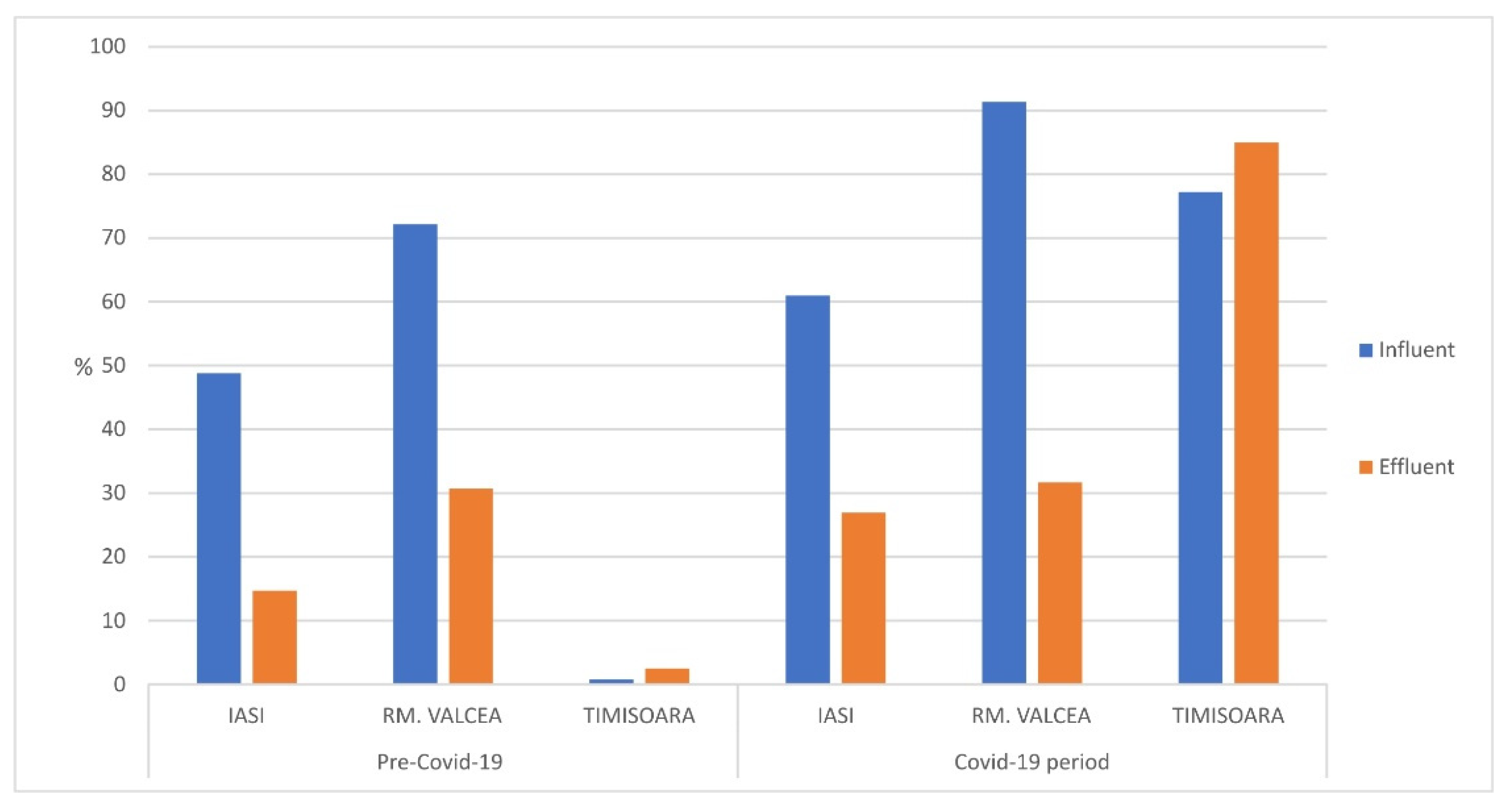

The fraction of fecal bacteria detected in total coliforms from WWTP’s influents and effluents was increased during Covid-19 pandemic compared to ante-Covid-19 (

Figure 3). In the city of Iasi (Eastern part of Romania) the percentage raise, during Covid-19 pandemic, in influent was around 10% compared to ante-Covid-19 time. A more significant fecal percentage raise (around 15%) was observed in effluent and this could be explained by an acquired resistance of fecal coliforms to WWTP treatment steps and chemical inputs, such as pharmaceutical compounds used in hospital units and released in the sewage system.

In Rm. Valcea (central part of Romania) the fecal coliforms percentage raised on total coliforms was observed only for WWTP influent, which was up to 20% in Covid-19 compared to ante-Covid-19. No significant changes in the fecal percentage from total coliforms in effluent. In Timisoara (Western part of Romania) it was observed a significant raised of fecal percentage from total coliforms during Covid-19, regardless of influent or effluent. This could be explained by the fact that Timisoara was the SARS-CoV-2 entrance gate in Romania and therefore the Covid-19 incidence was higher than central and eastern side of Romania as well as the medical treatment was implemented earlier which could induce an early acquired resistance of fecal bacteria to pharmaceutical compounds.

Some studies showed that Gram-negative bacteria antibiotic resistance, especially faecal such as E. coli, increased during the COVID-19 progression compared to Gram-positive bacteria [

24].

In this respect, during SARS-CoV-2 infection, Gram-negative bacteria such as total coliforms and E. coli were in contact with a large amount of pharmaceutical compounds, compared to ante-COVID-19 pandemic, increasing the resistance mechanism and subsequently the resistant Gram-negative bacterial population. This case scenario was analysed for Romanian WWTP during before Covid-19 pandemic and infection progression.

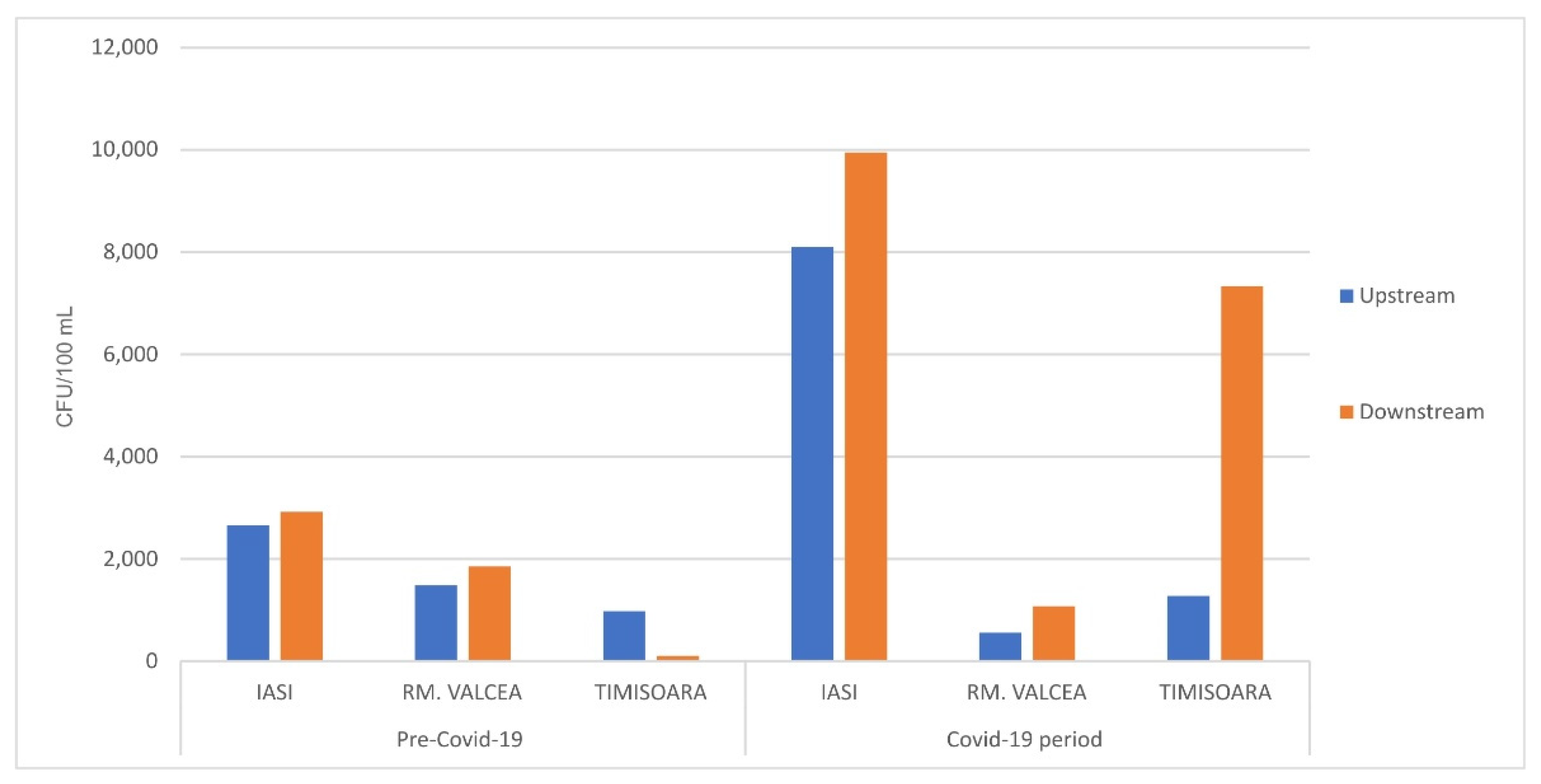

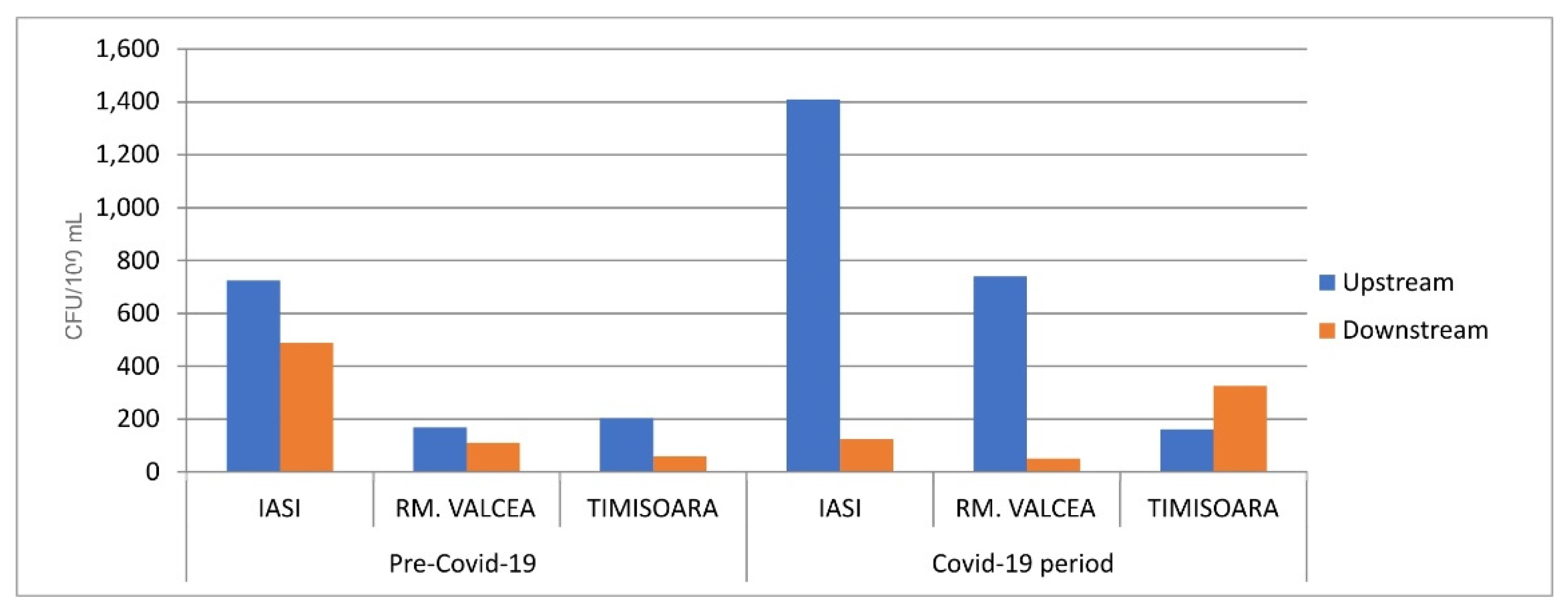

The fecal bacterial load from the streams, upstream the WWTP discharge site, was in the same rage in Covid-19 and ante-Covid-19 pandemic (

Figure 4) with the exception of Iasi where the fecal bacterial load was massively increased during SARS-CoV-2 infection. Overall, the fecal bacterial load discharged into the environment had an effect of increasing the fecal contamination, downstream of WWTP discharge site. Downstream fecal coliforms load from Iasi and Rm. Valcea had a comparable increase in the bacterial contamination between ante-Covid-19 and Covid-19 (

Figure 4). Timisoara, with a much higher SARS-CoV-2 incidence, showed a huge fecal contamination of WWTP downstream during Covid-19 compared to ante-Covid-19, in spite of having a comparable fecal load into the environment, upstream WWTP discharge site.

At Iasi, Salmonella spp.; a pathogenic bacteria belonging to fecal group, was detected in influent, effluent, downstream and upstream sites regardless of the sampling campaigned period, before Covid-19 infection or Covid-19 pandemic (data not shown). The same pattern of Salmonella spp. presence regardless or the sampling campaign was identified for WWTP’ influent from Rm. Valcea. A very interesting case was observed for Timisoara when Salmonella spp. was detected only in upstream during Covid-19 compared to ante-Covid-19 when Salmonella spp was detected in influent, effluent and upstream (data not shown). This could be explained by Salmonella spp sensitivity for pharmaceutical compounds present in the sewage system and discharged into the environment by the WWTP. The Covid-19 pandemic in Timisoara was characterized only by Salmonella spp presence in upstream which could be correlated with a high SARS-CoV-2 incidence, and subsequently with a high rate of usage of pharmaceutical compounds used during medical treatment for a large population. As an observation, Iasi (800k people) and Timisoara (500k people) have a comparable population, but a high Covid-19 incidence in Timisoara indirectly decreased Salmonella spp load due to an increased pharmaceutical treatment of Covid-19.

The enterococcal load pattern presence matched the fecal quantification in influent and effluent during ante-Covid-19 and after pandemic started. In Covid-19 progression, the enterococcal load increased, regardless of influent of effluent, compared to the period before pandemic (

Figure 5). In addition, the maximum increased was in Timisoara, which correlated with a high SARS-CoV-2 incidence compared to Rm. Valcea and Iasi.

The enterococcus loads ration between upstream and downstream increased during Covid-19 pointing out to a possible increased sensitivity of upstream bacterial loads to pharmaceutical WWTP discharges for all cities (

Figure 6). An interesting situation arose for Timisoara when upstream vs downstream enterococcus ration was inversed, perhaps due to an antibiotic resistance of enterococcus discharged from Timisoara WWTP. Previous results showed an increased antibiotic resistance due to a high pharmaceutical compounds usage [

26,

27]. Timisoara had a higher Covid-19 incidence than Iasi and Rm. Valcea and therefore Timisoara had a higher usage of pharmaceutical compounds which triggered the presence of more antibiotic resistant bacteria.

In Romanian clinics, the Covid-19 pandemic marked an increase number of Gram-negative pathogenic bacilli compared to the previous period when Gram-positive cocci were more common [

28]. This observation corroborated with a higher Covid-19 incidence in Timisoara, where the bacterial load had more interaction with larger amount of pharmaceutical which generated resistant bacteria ended up in natural streams (downstream) compared to the bacterial load from upstream.

According to recent studies [

4,

6,

29,

30,

31], the degree of pollution of the aquatic systems in Romania decreased with the decrease in the incidence of Covid-19 pandemic. Post-pandemic effects can be seen in the horizontal transmission of acquired antibiotic resistance and the perpetuation of resistant bacteria in aquatic environments with impacts on population health. Although the pandemic was significantly reduced, bacterial infections with resistant microorganisms continued to be present, especially in hospital units. Thus, various antimicrobial substances were still used, finally reaching the WWTP and affecting the subsequent treatment. Given that ecosystem stability is about temporal continuity, bacteria can continuously respond and adapt to secondary perturbations by changing patterns of assembly and function. Antimicrobial resistance remains a serious and emerging health system problem after Covid-19 that is exacerbated and widespread worldwide. This continues to generate unprecedented stimuli for doctors and researchers looking for the solution, prevention and management of this problem both at the medical level and at the environmental impact level.

4. Conclusions

Covid-19 had an indirect impact on microbial populations due the medical treatment against Covid-19 by using large amounts of pharmaceutical compounds, especially antibiotics. The Covid-19 progression in Romania could be monitored by the rise fecal bacterial loads from WWTP influent wastewaters. The same fecal pattern could be observed on enterococcus enteric bacteria. Enterococcus was linked to most of gastrointestinal infection and inflammatory bowel diseases, reported during Covid-19 peak period of time. Salmonella, another pathogenic bacteria, had no significant changes (monitored only by presence or absence) in influents and effluent, regardless of Covid-19 pandemic.

Unfortunately, it could be observed a clear fecal contamination of the natural aquatic bodies (downstream) by the WWTP effluent and this contamination seemed to increase in areas with a high Covid-19 incidence, Timisoara (5 – incidence number) city compared to Iasi and Valcea (3 – incidence number). The Enterococcus, Gram positive bacteria, got a more resistant rate when in contact with larger amount of pharmaceutical compounds and it could be observed in receptor river from Timisoara. In Valcea and Iasi with lower Covid-19 incidence rate the Enterococcus presence in downstream compared to upstream was similar, regardless of Covid-19 period of time. It was clear that a higher Covid-19 incidence increased the usage of pharmaceutical compounds which, at their turn, increased the number of resistant bacteria reaching the environment via WWTP effluents.

Fecal coliform bacteria in the final effluents play the role of quality indicators and indicate the presence of pathogens in wastewater with a high risk of transfer to natural water/environmental resources. In addition to information about the microbiological quality of wastewater or surface water, in the present case, coliforms also provide valuable subsequent information, such as the progression of Covid-19 and the increase in pharmaceutical use - phenomena with which they are correlated.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.R.B. and M.N.L.; Formal analysis A.R.B.; C.S.; S.G. and I.L.; Writing—original draft, A.R.B.; L.F.P.; L.F.; and M.N.L.; Writing—Review and Editing, A.R.B. and L.F.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the PN-III-P4-ID-PCCF-2016-0114 research project awarded by UEFISCDI.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to ongoing research in this field.

Acknowledgments

This work was “Nucleu” Program within the National Research Development and Innovation Plan 2019–2022 with the support of Romanian Ministry of Research, Innovation and Digitalization, contract no. 20N/2019, Project code PN 19 04 02 01.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cappelli, F.; Longoni, O.; Rigato, J.; Rusconi, M.; Sala, A.; Fochi, I.; Palumbo, M.T.; Polesello, S.; Roscioli, C.; Salerno, F.; et al. Suspect screening of wastewaters to trace anti-COVID-19 drugs: Potential adverse effects on aquatic environment. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 824, 153756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeras, I.; Burcea, A.; Banaduc, D.; Florea, D.I.; Curtean-Banaduc, A. Lotic ecosystem sediment microbial communities’ resilience to the impact of wastewater effluents in a polluted European Hotspot Mures Basin (Transylvania, Romania). Water 2024, 16, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osuolale, O.; Okoh, A. Human enteric bacteria and viruses in five wastewater treatment plants in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. J. Infect. Public Health 2017, 10, 541–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mare, R.; Mare, C.; Hadarean, A.; Hotupan, A.; Rus, T. COVID-19 and water variables: Review and scientometric analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaneti, R.N.; Girardi, V.; Spilki, F.R.; Mena, K.; Campos-Westphalen, A.P.; da Costa-Colares, E.R.; Pozzebon, A.G.; Etchepare, R.G. Quantitative microbial risk assessment of SARS-CoV-2 for workers in wastewater treatment plants. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 754, 142163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banciu, A.R.; Pascu, L.F.; Radulescu, D.M.; Stoica, C.; Gheorghe, S.; Lucaciu, I.; Ciobotaru, F.V.; Novac, L.; Manea, C. The COVID-19 pandemic impact of hospital wastewater on aquatic systems in Bucharest. Water 2024, 16, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johar, A.A.; Salih, M.A.; Abdelrahman, H.A.; Al Mana, H.; Hadi, H.A.; Eltai, N.O. Watewater-based epidemiology for tracking bacterial diversity and antibiotic resistance in COVID-19 isolation hospitals in Qatar. J. Hosp. Infect. 2023, 141, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdian, H.; Jamshidi, S. Performance evaluation of wastewater treatment plants under the sewage variations imposed by COVID-19 spread prevention action. J. Environ. Health Sci. Eng. 2021, 19, 1613–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Shen, Z.; Fang, W.; Gao, G. Composition of bacterial communities in municipal wastewater treatment plant. Sci. Total. Environ. 2019, 689, 1181–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makuwa, S.; Tiou, M.; Fosso-Kankeu, E.; Green, E. Evaluation of fecal coliform prevalence and physicochemical indicators in the effluent from a wastewater treatment plant in the North-West Province, South Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguilar-Salazar, A.; Martinez-Vazquez, A.V.; Aguilera-Arreola, G.; de Luna-Santillana, E.J.; Cruz-Hernandez, M.A.; Escobedo-Bonilla, C.M.; Lara-Ramirez, E.; Sanchez-Sanchez, M.; Guerrero, A.; Rivera, G.; et al. Prevalence of ESKAPE bacteria in surface water and wastewater sources: Multidrug resistance and molecular characterization, an updated review. Water 2023, 15, 3200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denissen, J.; Reyneke, B.; Waso-Reyneke, M.; Havenga, B.; Barnard, T.; Khan, S.; Khan, W. Prevalence of ESKAPE pathogens in the environment: Antibiotic resistance status, community-acquired infection and risk to human health. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. 2022, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loyola-Cruz, M.A.; Gonzales-Avila, L.U.; Martinez-Trejo, A.; Saldana-Padilla, A.; Hernandez-Cortez, C.; Bello-Lopez, J.M.; Castro-Escarpulli, G. ESKAPE and beyond: The burden of coinfections in the Covid-19 pandemic. Pathogens 2023, 12, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, A.S.; Ehasz, G.; Eramo, A.; Fahrenfeld, N. Changes in prevalence but not hosts of antibiotic resistance genes during the COVID-19 pandemic versus prepandemic in wastewater influent. ACS EST Water 2023, 3, 3626–3638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surleac, M.; Czobor-Barbu, I.; Paraschiv, S.; Popa, L.I.; Gheorghe, I.; Marutescu, L.; Popa, M.; Sarbu, I.; Talapan, D.; Nita, M.; et al. Whole genomic sequencing snapshot of multidrug resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae strains from hospitals and receiving wastewater treatment plants in southern Romania. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0228079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheorghe-Barbu, I.; Czobor-Barbu, I.; Popa, L.I.; Gradisteanu-Pircalaboiu, G.; Popa, M.; Marutescu, L.; Nita-Lazar, M.; Banciu, A.; Stoica, C.; Gheorghe, S.; et al. Temporo-spatial variations in resistance determinants and clonality of Acinetobacter baumannii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains from Romanian hospitals and wastewaters. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control. 2022, 11, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popa, L.P.; Gheorghe, I.; Czobor Barbu, I.; Surleac, M.; Paraschiv, S.; Marutescu, L.; Popa, M.; Gradisteanu-Pircalaboiu, G.; Talapan, D.; Nita-Lazar, M.; et al. Multidrug resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae ST101 Clone survival chain from inpatients to hospital effluent after chlorine treatment. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 610296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osunmakinde, C.O.; Selvarajan, R.; Mamba, B.B.; Msagati, T.A.M. Profiling bacterial diversity and potential pathogens in wastewater treatment plants using high-throughput sequencing analysis. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kokkinos, P.; Mandilara, G.; Nikolaidou, A.; Velegraki, A.; Theodoratos, P.; Kampa, D.; Blougoura, A.; Christopoulou, A.; Smeti, E.; Kamizoulis, G.; et al. Performance of three small-scale wastewater treatment plants. A challenge for possible reuse. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 17744–17752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

ISO 19458; Water Quality – Sampling for microbiological analysis. International Organisation for Standardization: Geneva, Zwitzerland, 2007.

-

ISO 9308-2; water quality – Detection and enumeration of coliform organisms thermotolerant coliform organisms and presumptive Escherichia coli – Part 2: Multiple Tube (Most Probable Number) Method. International organization for Standardization: Geneva, Zwitzerland, 2014.

-

ISO 7899-2; Water quality – detection and enumeration of intestinal Enterococci part 2: - Membrane filtration Method. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Zwitzerland, 2008.

- Durairajan, S.S.K.; Singh, A.K.; Saravanan, U.B.; Namachivayam, M.; Radhakrishnan, M.; Huang, J.D.; Dhodapkar, R.; Zhang, H. Gastrointestinal Manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 : Transmission, pathogenesis, immunomodulation, microflora dysbiosis, and clinical implications. Viruses 2023, 15, 1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbu, I.C.; Barbu-Gheorghe, I.; Grigore, G.A.; Vrancianu, C.O.; Chifiriuc, M.C. Antimicrobial resistance in Romania: Updates 454 on Gram-Negative ESCAPE pathogens in the clinical, veterinary, and aqautic sectors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Ziquan, L.; Liangqiang, L.; Xiaowei, L.; Jian, X.; Suli, H.; Yuhua, C.; Yulin, F.; Changfeng, P.; Tingting, C.; et al. Impact of Covid-19 pandemic on profiles of antibiotic-resistant genes and bacteria in hospital wastewater. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 334, 122133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugerwa, I.; Nabadda, S.N.; Midega, J.; Guma, C.; Kalyesubula, S.; Muwonge, A. Antimicrobial resistance situational analysis 2019-2020: Design and performance for human health surveillance in Uganda. Med. Infect. Dis. 2021, 6, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, S.; Hays, J.P.; Kemp, A.; Okechukwu, R.; Murugaiyan, J.; Ekwanzala, M.D.; Alvarez, M.J.; Paul-Satyaseela, M.; Iwu, C.D.; Balleste-Delpiere, C.; et al. The potential impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on global antimicrobial and biocide resistance: An AMR insights global perspective. JAC Antimicrob. Resist. 2021, 3, dlab038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golli, A.L.; Zlatian, O.; Cara, M.L. Pre- and post-Covid-19 antimicrobial resistance pattern of pathogens in an intensive care unit. Preprints.org. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccabella, L.; Palma, G.E.; Abenavoli, L.; Scarlata, G.G.M.; Boni, M.; Ianiro, G.; Santori, P.; Tack, J.F.; Scarpellini, E. Post-Coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic antimicrobial resistance. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, S.; Cao, W.; Wu, Q.; Cheng, S.; Jin, H.; Pang, H.; Zhou, A.; Feng, L.; Cao, J.; Luo, J. Dynamic microbiome disassembly and evolution induced by antimicrobial methylisothiazolinone in sludge anaerobic fermentation for volatile fatty acids generation. Water Res. 2024, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banciu, A.R.; Gheorghe, S.; Stoica, C.; Lucaciu, I.; Nita-Lazar, M. Post-pandemic effects on faecal pollution of aquatic systems. E-SIMI 2021, 72–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).