Submitted:

07 March 2024

Posted:

08 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Statistical Analysis

- 1.

- Simpon’s Diversity index:where ni is the number of individuals of one particular species found, N is the total number of individuals found.D = Σ[(ni/N)2]

- 2.

- Shannon index (H’) []:where ni is the number of individuals of one particular species found, N is the total number of individuals found.H’ = -Σ[ni/N*log(ni/N)

- 3.

- Pielou's evenness:where S is the total number of species.E = H’/ln S

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wende, B.; Gossner, M.; Grass, I.; Arnstadt, T.; Hofrichter, M.; Floren, A.; Linsenmair, K. E.; Weisser, W.; Steffan-Dewenter, I. Trophic level, successional age and trait matching determine specialization of deadwood-based interaction networks of saproxylic beetles. Proc. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 2017, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, I.; Spence, J. R.; Langor, D. W. Succession of saproxylic beetles associated with decomposition of boreal white spruce logs. Agric. For. Entomol. 2014, 16, 391–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffa, K.F.; Grégoire, J.; Staffan Lindgren, B. Bark Beetles. Evolution and Diversity of Bark and Ambrosia Beetles. In Bark Beetles: biology and ecology of native and invasive species; Vega, F. E., Hofstetter, R.W., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, USA, 2014; pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frühbrodt, T.; Schebeck, M.; Andersson, M.N; Holighaus, G.; Kreuzwieser, J.; Burzlaff, T.; Delb, H.; Biedermann, P.H.W. Verbenone—the universal bark beetle repellent? Its origin, effects, and ecological roles. J. Pest Sci. 2024, 97, 35–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkendall, L.R.; Biedermann, P.H.W.; Jordal, B.H. Bark Beetles. In Bark Beetles: biology and ecology of native and invasive species; Vega, F. E., Hofstetter, R.W., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, USA, 2014; pp. 85–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staffan Lindgren, B.; Miller, D. R. Effect of Verbenone on Five Species of Bark Beetles (Coleoptera: Scolytidae) in Lodgepole Pine Forests. Environ. Entomol. 2002, 31, 759–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, R.M.; Birkemoe, T.; Sverdrup-Thygeson, A. Priority effects of early successional insects influence late successional fungi in dead wood. Ecol. Evol. 2015, 5, 4896–4905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedard, W.D.; Tilden, P.E.; Lindahl, K.Q.; Wood, D.L.; Rauch, P.A. Effects of verbenone andtrans-verbenol on the response of Dendroctonus brevicomis to natural and synthetic attractant in the field. J. Chem. Ecol. 1980, 6, 997–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentz, B.J.; Kegley, S.; Gibson, K.; Their, R. A test of high-dose verbenone for stand-level protection of lodgepole and whitebark pine from mountain pine beetle (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae) attacks. J. Econ. Entomol. 2005, 98, 1614–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fettig, C.J.; Munson, A.S. Efficacy of verbenone and a blend of verbenone and nonhost volatiles for protecting lodgepole pine from mountain pine beetle (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). Agr.Forest. Entomol. 2020, 22, 373–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fettig, C. J.; Munson, A.S.; Reinke, M.; Mafra-Neto, A. A novel semiochemical tool for protecting lodgepole pine from mortality attributed to mountain pine beetle (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 2015, 108, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fettig, C.J.; Steed, B.E.; Bulaon, B.M.; Mortenson, L.; Progar, R.; Bradley, C.; Munson, S.; Mafra-Neto, A. The efficacy of SPLAT® verb for protecting individual Pinus contorta, Pinus ponderosa, and Pinus lambertiana from colonization by Dendroctonus ponderosae. J. Entomol. Soc. B.C. 2016, 113, 11–20. [Google Scholar]

- Progar, R.; Fettig, C.J.; Munson, A.S.; Mortenson, L.; Snyder, C.; Kegley, S.; Cluck, D.; Steed, B.; Mafra-Neto, A.; Rinella, M. Comparisons of Efficiency of Two Formulations of Verbenone (4, 6, 6-trimethylbicyclo [3.1.1] hept-3-en-2-one) for Protecting Whitebark Pine, Pinus albicaulis (Pinales: Pinaceae) from Mountain Pine Beetle (Colopetera: Curculionidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 2021, 114, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bracalini, M.; Croci, F.; Tiberi, R.; Panzavolta, T. Studying Ips sexdentatus (Börner) outbreaks in Italian coastal pine stands: Technical issues behind trapping in warmer climates. In Proceedings of the XI European Congress of Entomology, Naples, Italy, 2–6 July 2018; p. 171. [Google Scholar]

- Martín, A.; Etxebeste, I.; Pérez, G.; Álvarez, G.; Sánchez, E.; Pajares, J. Modified pheromone traps help reduce bycatch of bark-beetle natural enemies. Agric. For. Entomol. 2013, 15, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracalini, M.; Croci, F.; Ciardi, E.; Mannucci, G.; Papucci, E.; Gestri, G.; Tiberi, R.; Panzavolta, T. Ips sexdentatus Mass-Trapping: Mitigation of Its Negative Effects on Saproxylic Beetles Larger Than the Target. Forests 2021, 12, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimmel, M.L.; Ferro, M.L. General Overview of Saproxylic Coleoptera. In Saproxylic Insects. Zoological Monographs, vol 1; Ulyshen, M., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 1, 51–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmain, G.; Bouget, C.; Müller, J.; Horak, J.; Gossner, M.M.; Lachat, T.; Isacson, G. Can rove beetles (Staphylinidae) be excluded in studies focusing on saproxylic beetles in central European beech forests? Bull. Entom. Res. 2015, 105, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baqué, M.; Amendt, J. Strengthen forensic entomology in court – the need for data exploration and the validation of a generalised additive mixed model. Int. J. Leg. 2013, 127, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benni, S.; Pastell, M.; Bonora, F.; Tassinari, P.; Torreggiani, D. A generalised additive model to characterise dairy cows’ responses to heat stress. Animal 2020, 14, 418–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, S.N. Fast stable restricted maximum likelihood and marginal likelihood estimation of semiparametric generalized linear models. J. R. Stat. B Methodol. 2011, 73, 3–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, S.N.; Pya, N.; Saefken, B. Smoothing parameter and model selection for general smooth models (with discussion). JASA 2016, 111, 1548–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 15 February 26, 2024).

- Magurran, A. E. Ecological Diversity and Its Measurement; Princeton University Press: New Jersey, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Paiva, M. R.; Pessoa, M. F.; Vité, J. P. Reduction in the pheromone attractant response of Orthotomicus erosus (Woll.) and Ips sexdentatus Boern. (Col., Scolytidae). J. Appl. Entomol. 1988, 106, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romón, P.; Iturrondobeitia, J.C.; Gibson, K.; Lindgren, B.S.; Goldarazena, A. Quantitative association of bark beetles with pitch canker fungus and effects of verbenone on their semiochemical communication in Monterey pine forests in Northern Spain. Environ. Entomol. 2007, 36, 743–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etxebeste, I.; Pajares, J.A. Verbenone protects pine trees from colonization by the six-toothed pine bark beetle, Ips sexdentatus Boern. (Col.: Scolytinae). J. Appl. Entomol. 2011, 135, 258–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etxebeste, I.; Lencina, J.L.; Pajares, J. Saproxylic community, guild and species responses to varying pheromone components of a pine bark beetle. Bull. Entomol. Res. 2013, 103, 497–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etxebeste, I.; Álvarez, G.; Pajares, J. Log colonization by Ips sexdentatus prevented by increasing host unsuitability signaled by verbenone. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 2013, 147, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meurisse, N.; Pawson, S. Quantifying dispersal of a non-aggressive saprophytic bark beetle. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0174111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panzavolta, T.; Bracalini, M.; Bonuomo, L.; Croci, F.; Tiberi, R. Field response of non-target beetles to Ips sexdentatus aggregation pheromone and pine volatiles. J. Appl. Entomol. 2014, 138, 586–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarikaya, O.; Ibis, H.M. Predatory Species of Bark Beetles in the Pine Forests of Izmir Region in Turkey with New Records for Turkish Fauna. Egypt. J. Biol. Pest Control. 2016, 26, 651–656. [Google Scholar]

- Tutku, G.; Sarikaya, O. Predatory Species of Scolytinae in Bursa Province of Turkey. Int. J. Biol. Chem. 2023, 16, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünal, S. Bark beetles and their predatories with parasites of oriental spruce (Picea orientalis (L.) Link) forests in Turkey. nwsaecolife 2010, 5, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staffan Lindgren, B.; Miller, D. R. Effect of Verbenone on Attraction of Predatory and Woodboring Beetles (Coleoptera) to Kairomones in Lodgepole Pine Forests. Environ. Entomol. 2002, 31, 766–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocoş, D.; Etxebeste, I.; Schroeder, M. An efficient detection method for the red-listed beetle Acanthocinus griseus based on attractant-baited traps. Insect Conserv. Divers. 2017, 10, 294–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seibold, S.; Bässler, C.; Brandl, R.; Büche, B.; Szallies, A.; Thorn, S.; Ulyshen, M. D.; Müller, J. Microclimate and habitat heterogeneity as the major drivers of beetle diversity in dead wood. J. Appl. Entomol. 2016, 53, 934–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graf, M.; Lettenmaier, L.; Müller, J.; Hagge, J. Saproxylic beetles trace deadwood and differentiate between deadwood niches before their arrival on potential hosts. Insect Conserv. Divers. 2021, 15, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Species/Feeding guild | Family | No. of specimens |

|---|---|---|

| Bark beetles | Curculionidae | 7528 |

| Ips sexdentatus (Boern) | 114 | |

| Crypturgus mediterraneus Eichhoff | 3 | |

| Crypturgus pusillus (Gyllenhal) | 8 | |

| Hylastes linearis Erichson | 1 | |

| Hylurgus ligniperda (Fabricius) | 272 | |

| Hylurgus micklitzi Wachtl | 1 | |

| Orthotomicus erosus (Wollaston) | 7101 | |

| Pityogenes bidentatus (Herbst) | 16 | |

| Xylocleptes biuncus Reitter | 11 | |

| Xyleborus saxesenii (Ratzeburg) | 1 | |

| Predators | 1628 | |

| Bradycellus verbasci (Duftschmid) | Carabidae | 6 |

| Dromius meridionalis Dejean | Carabidae | 5 |

| Olisthopus Dejean | Carabidae | 1 |

| Thanasimus formicarius (Linnaeus) | Cleridae | 93 |

| Lacon punctatus (Herbst) | Elateridae | 3 |

| Paromalus parallelepipedus (Herbst) | Histeridae | 1 |

| Platysoma elongatum (Thunberg) | Histeridae | 2 |

| Plegaderus otti Marseul | Histeridae | 67 |

| Rhizophagus depressus (Fabricius) | Monotomidae | 214 |

| Temnochila caerulea (Olivier) | Trogossitidae | 976 |

| Corticeus pini (Panzer) | Tenebrionidae | 95 |

| Aulonium ruficorne (Olivier) | Zopheridae | 165 |

| Other saproxylic beetles | 174 | |

| N.D. | Anobiidae | 27 |

| Hirticomus hispidus (Rossi) | Anthicidae | 2 |

| N.D. | Anthicidae | 1 |

| Pseudeuparius centromaculatus (Gyllenhal) | Anthribidae | 1 |

| Anthaxia Solier | Buprestidae | 2 |

| Buprestis novemmaculata Linnaeus | Buprestidae | 1 |

| Acanthocinus griseus (Fabricius) | Cerambycidae | 61 |

| Cerylon Latreille | Cerylonidae | 1 |

| Brachyderes incanus (Linnaeus) | Curculionidae | 20 |

| Brachytemnus porcatus (Germar) | Curculionidae | 31 |

| Carphoborus pini Eichhoff | Curculionidae | 4 |

| Pissodes castaneus (De Geer) | Curculionidae | 1 |

| Trinodes hirsutus (Fabricius) | Dermestidae | 1 |

| Cardiophorus collaris Erichson | Elateridae | 7 |

| Melanotus Eschscholtz | Elateridae | 1 |

| N.D. | Eucinetidae | 2 |

| Margarinotus Marseul | Histeridae | 1 |

| Enicmus Thomson | Latridiidae | 2 |

| Nacerdes melanura (Linnaeus) | Oedemeridae | 1 |

| N.D. | Oedemeridae | 1 |

| N.D. | Scraptiidae | 2 |

| N.D. | Silvanidae | 3 |

| Diaperis boleti (Linnaeus) | Tenebrionidae | 1 |

| Non-saproxylic beetles | 110 | |

| Dicladispa testacea (Linné) | Chrysomelidae | 1 |

| Hydroglyphus pusillus (Fabricius) | Dytiscidae | 1 |

| Ochthebius Leach | Hydraenidae | 61 |

| Cryptopleurum Mulsant | Hydrophilidae | 1 |

| Leiodes Latreille | Leiodidae | 1 |

| Meligethes Stephens | Nitidulidae | 1 |

| Pria dulcamarae (Scopoli) | Nitidulidae | 2 |

| Onthophagus Latreille | Scarabaeidae | 2 |

| Onthophagus furcatus (Fabricius) | Scarabaeidae | 1 |

| Pleurophorus mediterranicus Pittino & Mariani | Scarabaeidae | 1 |

| Isomira Mulsant | Tenebrionidae | 35 |

| Lagria Fabricius | Tenebrionidae | 3 |

| Total | 9440 |

| Ph-trap catches | Ph+V-trap catches | Results of GAMM analysis | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| intercept | Verbenone effect | Seasonal effect | |||||||

| coeff. | F | P | edf | F | P | ||||

| Bark beetles | |||||||||

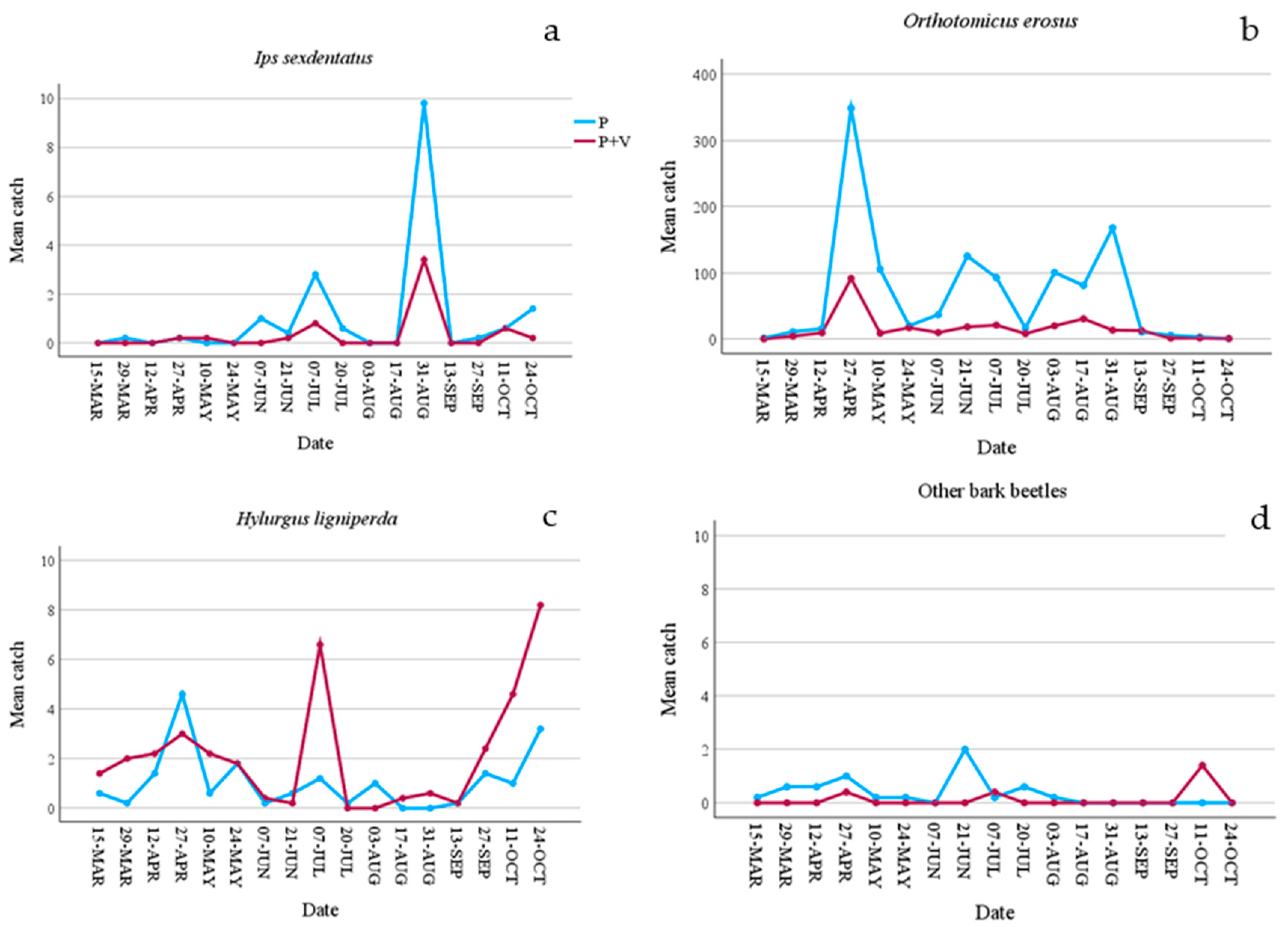

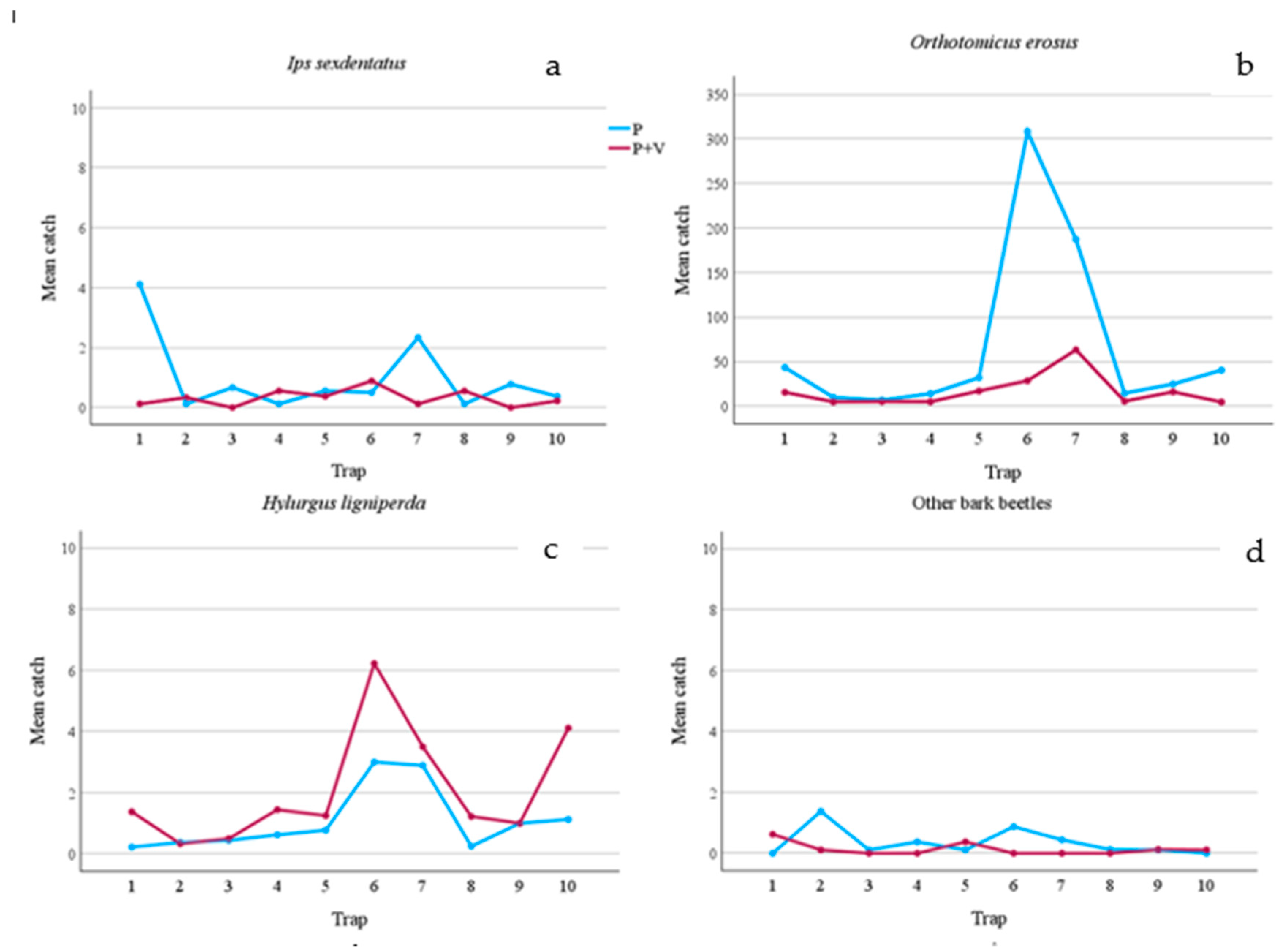

| I. sexdentatus | 86 | 28 | -1.237 | -0.968 | 18.37 | <0.001 | 8.187 | 17.22 | <0.001 |

| O. erosus | 5736 | 1365 | 2.680 | -1.495 | 2316.00 | <0.001 | 8.979 | 531.80 | <0.001 |

| H. ligniperda | 91 | 181 | -0.551 | 0.643 | 24.24 | <0.001 | 8.033 | 17.77 | <0.001 |

| Predators | |||||||||

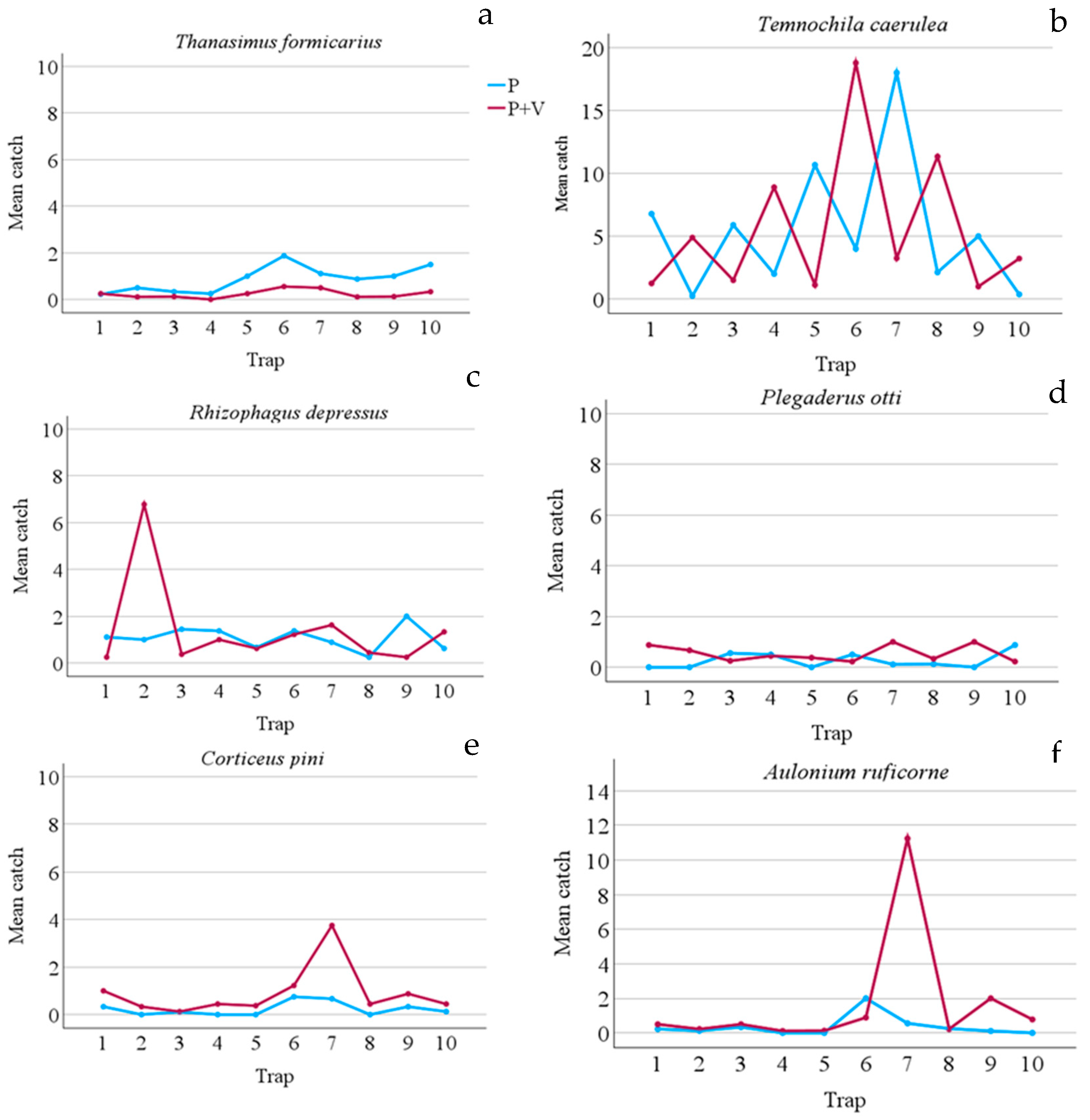

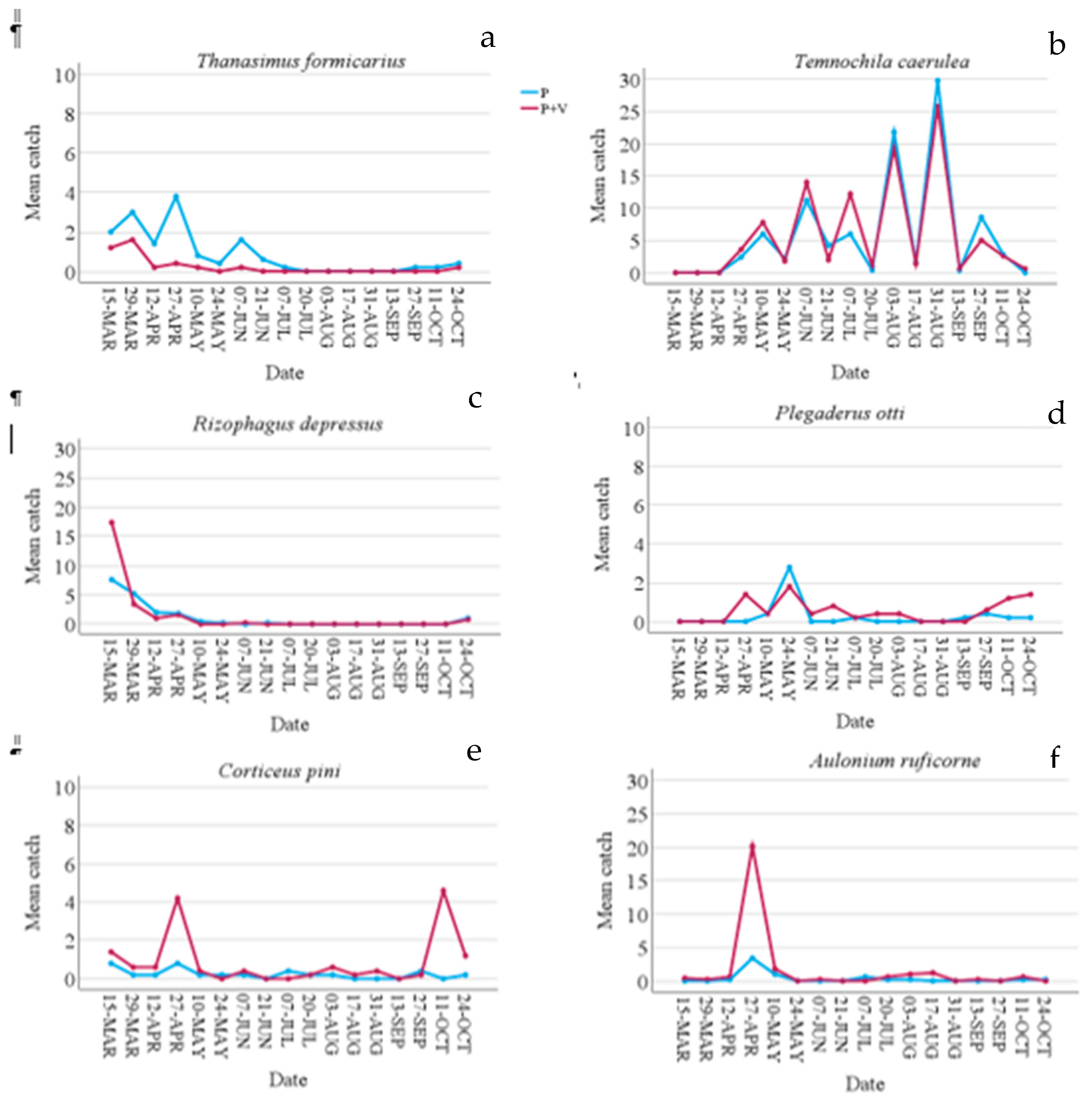

| T. formicarius | 73 | 20 | -1.098 | -1.323 | 26.93 | <0.001 | 4.04 | 17.53 | <0.001 |

| T. caerulea | 487 | 489 | 0.662 | 0.004 | 0.00 | ns | 7.478 | 42.53 | <0.001 |

| R. depressus | 92 | 122 | -2.580 | 0.076 | 0.24 | ns | 4.537 | 59.94 | <0.001 |

| P. otti | 22 | 45 | -2.049 | 0.716 | 7.48 | <0.01 | 5.41 | 7.41 | <0.001 |

| C. pini | 20 | 75 | -2.238 | 1.343 | 27.54 | <0.001 | 7.985 | 7.82 | <0.001 |

| A. ruficorne | 30 | 135 | -2.978 | 1.214 | 30.82 | <0.001 | 8.453 | 36.52 | <0.001 |

| Other saproxylic beetles | |||||||||

| total | 110 | 64 | 0.125 | -0.524 | 10.92 | <0.001 | 1.555 | 5.17 | ns |

| Non-saproxylic beetles | |||||||||

| total | 50 | 60 | -1.280 | 0.199 | 1.08 | ns | 6.995 | 18.68 | <0.001 |

| Species no. | Unique species | Relative abundance (%) | Species no. | Unique species | Relative abundance (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ph | Ph+V | Ph | Ph+V | Ph | Ph+V | OA | CA | OA | CA | OA | CA | |

| Bark beetles | 9 | 6 | 4 | 1 | 86.91 | 60.94 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 64.69 | 87.88 |

| Predators | 10 | 11 | 1 | 2 | 10.76 | 34.29 | 10 | 10 | 5 | 3 | 29.53 | 11.33 |

| Other saproxylic beetles | 15 | 16 | 9 | 8 | 1.61 | 2.46 | 10 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 3.37 | 0.60 |

| Non-saproxylic beetles | 7 | 9 | 3 | 5 | 0.73 | 2.31 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 2.44 | 0.19 |

| Total | 41 | 42 | 15 | 16 | 32 | 26 | 13 | 7 | ||||

| Shared species | 26 | 19 | ||||||||||

| Trap no. | 10 10 | 2 | 2 | |||||||||

| Total specimens | 6839 2601 | 861 | 5791 | |||||||||

| Simpson’s index | 0.709 0.322 | 0.378 | 0.725 | |||||||||

| Shannon index | 0.80 | 1.70 | 1.61 | 0.62 | ||||||||

| Evenness | 0.149 0.313 | 0.322 | 0.132 | |||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).