1. Introduction

The global environmental crisis is one of the most pressing issues of the 21st Century [

1]. It includes various ecological crises happening in the world today, including climate change. The scientific evidence for anthropogenic climate change is overwhelming; 97% of peer-reviewed papers accept that global climate change results from human activities [

2,

3]. Before this situation, human reactions varied along emotional, cognitive, and behavioral dimensions, forming a complex mixture of related variables that can be studied at different levels of abstraction, both as causes and consequences. The ultimate goal is always to act in line with what improves or at least does not worsen the environmental crisis, which is not always easy because when it comes to acting pro-environmentally, there is not one behavior but many very different types. This study contributes to this goal by developing an emotional measure of willingness for environmental behavior and analyzing its relationships with antecedent variables such as climate change perceptions, eco-anxiety, and trust in science.

1.1. Perception and Behavior: An Essential Path but not Sufficient

It is assumed that perceptions about climate change play a role in whether people take actions to mitigate their environmental impacts and whether they support government climate policies [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. In this respect, reliable perceptions about climate change can be considered a success of many disciplines in the last decades to make us aware of the incredible variety of climate change consequences. Such perceptions can be considered indisputably necessary, and there are good current models to explain what variables depend on [

10,

11,

12].

However, it is also well known that good perceptions of reality do not necessarily connect with coherent behaviors [

5,

13]. Many other variables may also explain why good perceptions about the situation are necessary but not enough to change behaviors and make significant impacts. To bridge this gap, the Theory of Reasoned Action long ago proposed the behavioral intention variable as a mediator between perception and behavior and, above all, insisted on the need to use variables at the same level of abstraction [

14,

15].

An additional difficulty in the context of the climate crisis is that the pro-environmental behaviors and their corresponding specific behavioral intentions are innumerable, of very different scopes, and even of a different nature [

16,

17,

18]. They may range from voluntarily “doing new things” such as recycling, planting trees, protesting, eating a vegetarian diet, composting, reusing towels in hotel rooms, participating in local politics, buying local and organic food, to “not doing other many things” (do not bathe, do not consume, whether in general or a product, or a brand, or a service, do not use plastics, reduce driving, use less water and electricity), passing through accepting the social restrictions that many governments are beginning to impose, such as prohibiting air travel for short trips, prohibiting single-use plastics, prohibiting heating or cooling spaces above or below a specific temperature, paying extra by parking, gasoline, air or water. As a result, the authors are forced to select as the dependent variable the set that best describes a person with a high intention to act in favor of the environment.

The lack of general measures of behavioral willingness prevents researchers from connecting general perceptions about the climate situation (abstract) at the same high level of abstraction with the great diversity of pro-environmental intentions and behaviors grouped for each occasion (specific). This also prevents the adequate study of variables, such as eco-anxiety and trust in science, which could mediate the relationship between general perceptions about the situation and general willingness to act accordingly.

1.2. Eco-Anxiety: An Unpleasant Consequence that Precedes Willingness for Environmental Behavior

Nowadays, feeling anxious about the state of the planet appears to be universal [

19], with evidence currently emerging from Europe [

20,

21], America [

22], Canada [

23], Pacific Islands [

24] and China [

25]. Despite this, there is much to study about its role and optimal level in promoting consistent behaviors that should resolve the causes that originate it.

Technically, eco-anxiety is described as any anxiety related to the global ecological crisis, including climate anxiety [

26,

27,

28]. This broader perspective that examines anxiety in relation to a multitude of environmental issues places eco-anxiety at a high level of abstraction. That is why most authors define it as an emotional reaction of concern, worry, and fear given global climate change threats and concurrent environmental degradation [

29].

Such a general perspective does not prevent eco-anxiety from being understood as a multi-faceted concept [

30]. At least four dimensions have been studied: affective symptoms, behavioral symptoms, negative emotionality, and rumination [

31]. Because these underlying dimensions seem to be distinct from stress and depression, there is some consensus when considering eco-anxiety as a rational reaction to the enormity of the ecological threat humanity and the planet is facing [

31]. In this respect, it would be considered a “practical anxiety” [

32], leading to problem-solving attitudes [

28,

33] and pro-environmental actions [

34].

Although experiences of anxiety relating to environmental crises include negative emotions and feelings of uncertainty, unpredictability, and uncontrollability, all of which are classic ingredients in anxiety disorders [

28], most forms of eco-anxiety can be considered non-pathological. This non-pathological eco-version of anxiety is currently being associated with pro-ecological worldviews, green self-identity, and specific pro-environmental behaviors such as saving energy in the household, trying to influence family and friends to act pro-environmentally, taking public transportation instead of the car, or avoid food waste [

18,

35]. These initial results suggest that eco-anxiety would not always be a state to be resolved or avoided but rather a desirable state that, together with other variables, such as trust in science that provides cognitive security to the unpleasant atmosphere created by eco-anxiety, can play an active and positive role in promoting a wide range of pro-environmental behaviors.

1.3. Trust in Science as a Metacognition of Confidence in One’s Own Beliefs about the Climate Crisis

Science is the most trusted source of information about climate change [

36,

37]. It is estimated that there is 98% agreement amongst climate scientists that it is real and human-caused [

41,

42]. Although skepticism about climate change seems to be a prevalent answer that also tries to find support on scientific arguments [

37,

40], it is estimated that climate change denial or skepticism is less widespread than often assumed (Steg, 2018; van Valkengoed et al., 2021). So, trust in science mostly means confidence about one’s own climate change beliefs, that is, the existence and danger of climate change.

Additionally, when people’s ability and motivation to carefully process scientific information is limited, which is the case for most people most of the time [

43,

44], it is expected people to use message source as a heuristic cue in evaluating the message, with more congruent change in response to scientist sources [

45,

46]. Since trusting in science can exempt us from thinking carefully, it is possible to suggest that it can work as a metacognition that provides cognitive confidence and security in one’s own perceptions about climate change that may be positively related to willingness to act.

Generally, trust in science has been associated with more significant concerns about environmental issues [

37,

47]. It has also been associated with political ideology, where Liberals are more likely than Conservatives to trust in science as a source of information about climate change [

48]. These connections are promising, but much remains to be done to outline the role of trust in science concerning other variables. In this respect, we anticipated that trust in science could be the perfect partner for eco-anxiety, adding cognitive security to the emotional discomfort provided by eco-anxiety.

1.4. Objectives and Hypothesis

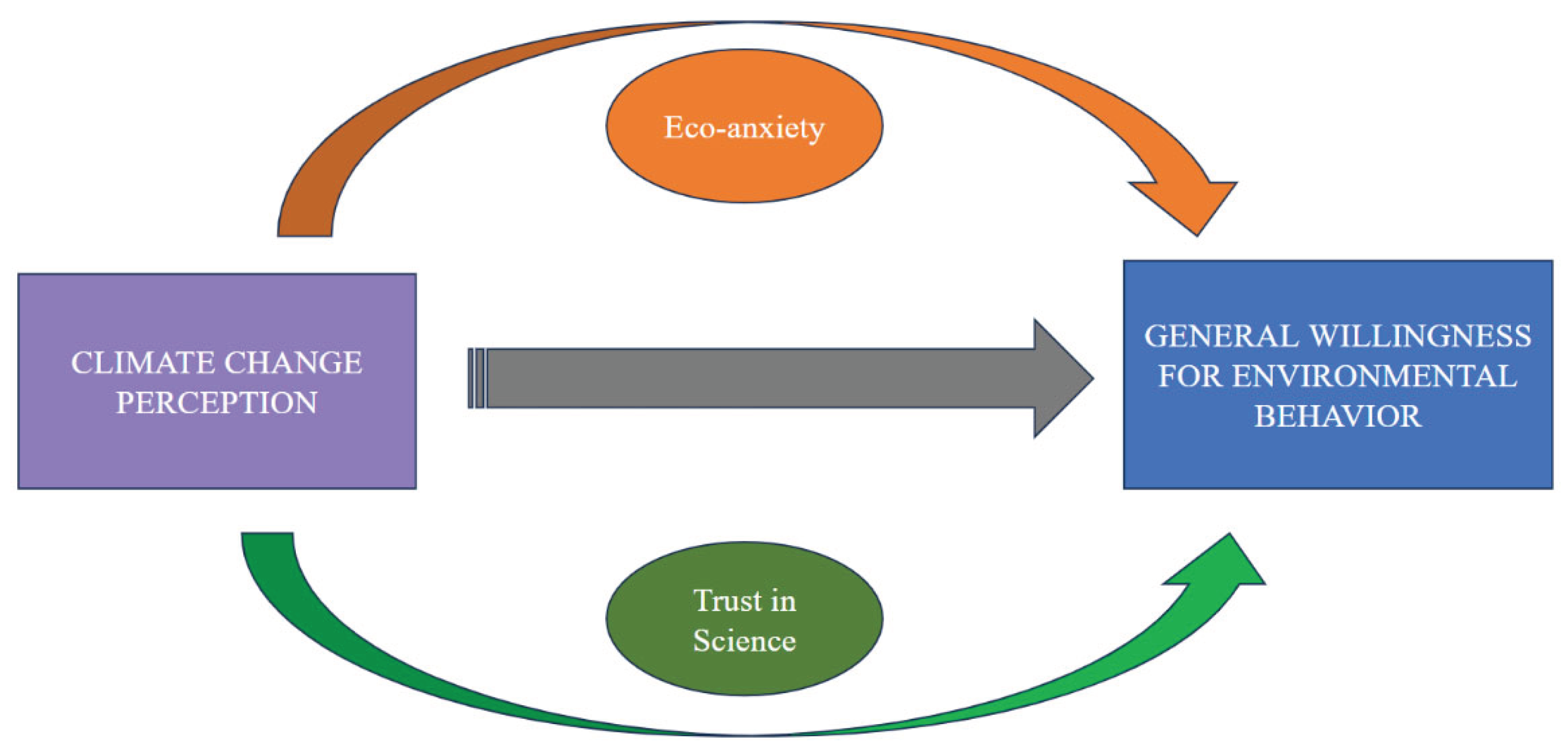

In this paper, we aim for two objectives: 1) developing a general measure of willingness for environmental behavior that makes it possible to connect at a high level of abstraction psychological variables and 2) testing two indirect paths that, through the unpleasant emotion of eco-anxiety and the metacognition of trust in science, allow to connect climate change perceptions with willingness for environmental behavior (see

Figure 1). These two related objectives may be useful in designing policies and communication strategies to join increasingly individual efforts against climate change.

Regarding objective 1, we started from the idea that using a single item to evaluate the intention to act in favor of the environment can be simple and very common [

49,

50] but perhaps also insufficient to capture its true meaning, especially if we take into account the great diversity of pro-environmental behaviors. These behaviors may imply doing and the opposite, not doing, and also accepting doing and accepting not doing at the request of governments that begin to legislate in this way, forcing and prohibiting the entire population from doing and not doing. So, we tested only four items precisely to tap our idea of a general willingness for environmental behavior, which was emotional and not reducible to any particular behavior but open to all. The items were initially written in Spanish. Their translation into English can be seen in

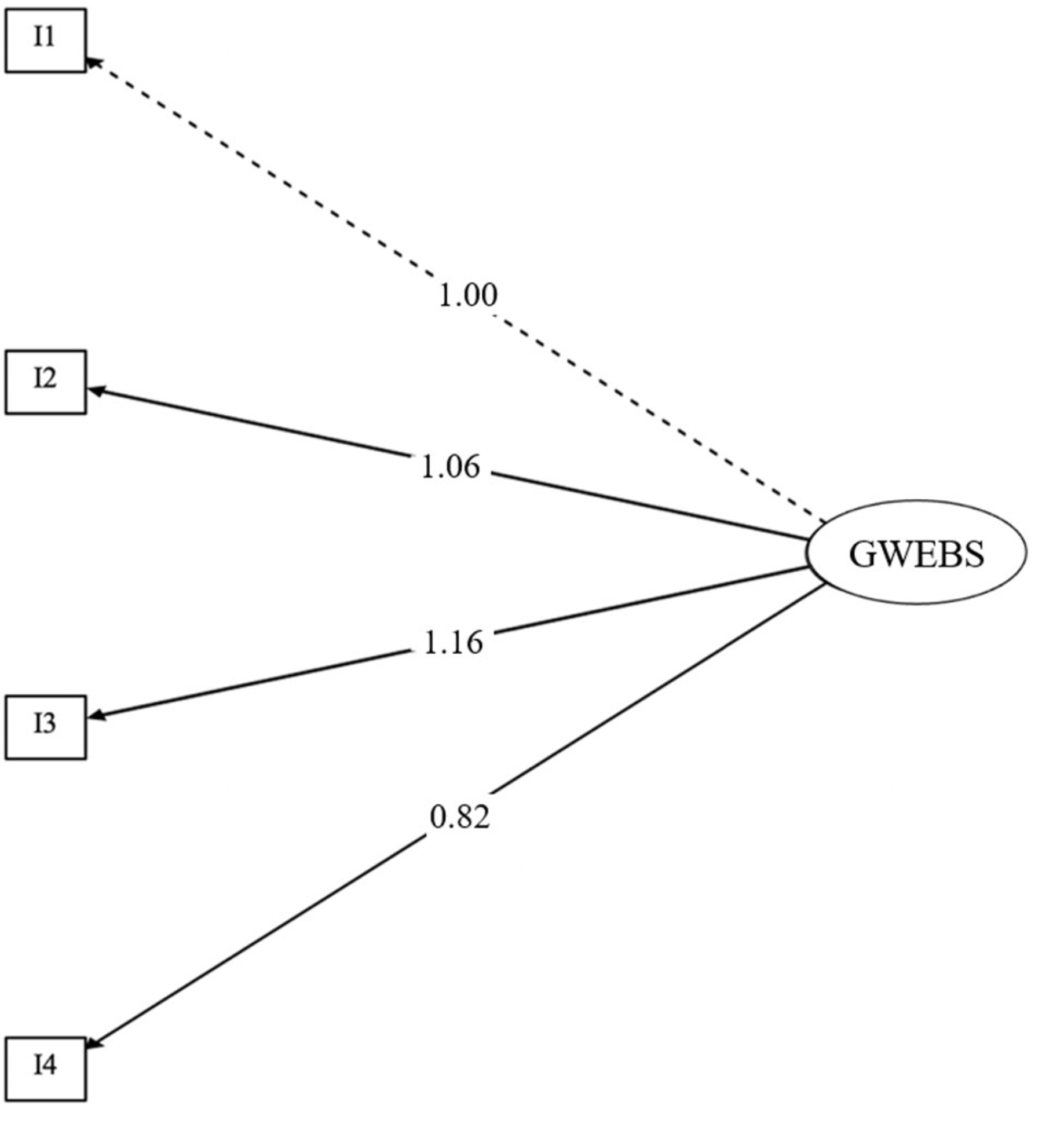

Table 1. A one-factor structure was hypothesized, meaning we propose a latent concept composed of four observed variables.

Regarding objective 2, we hypothesized that perceptions about climate change would be related to the previously developed General Willingness for Environmental Behavior Scale (GWEBS) through eco-anxiety and trust in science both directly and indirectly. In this regard, we started from the idea that each variable has shown a connection with specific pro-environmental behaviors but not in relationship models of several variables and does not concern a general intention on which different subsets of specific pro-environmental behaviors may depend. Because being female and holding liberal political views are generally associated with higher climate change risk perceptions and willingness to take action in order to mitigate climate change [

11,

48,

51,

52], we controlled in our mediation model gender and political orientation. Additionally, we controlled different levels of environmental sensitivity operationalized as belonging to a group in defense of the environment.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

Participants were recruited through social media, websites, and well-known associations with environmental purposes. We looked for diversity in the sample composition to control gender, political orientation, and levels of environmental sensitivity. Additionally, we used the snowball procedure and the express instruction that we were looking for people with diverse perspectives on the climate situation, from the most favorable to the most contrary. It was a non-probabilistic convenience sampling. Participants self-reported their answers online before signing an informed consent. The university ethics committee approved the study’s procedures (Ref. 0407202327123).

Given the variables involved in this study, the target sample size was predetermined accordingly through an a priori statistical power analysis using G*Power 3.1 (Faul et al., 2009)#. Assuming a small effect size of f2 = 0.02, with a = 0.05 and power = 0.80, the needed sample size was N = 395. The sample was finally composed of 403 participants (35.3% men and 64.3% women) of Spanish nationality, with an age range between 18 and 81 years (M = 42.74, SD = 14.91). Twenty-five percent of the participants were involved in an environmental association. Regarding political orientation, 67% self-reported being left-wing, whereas 33% were center-right orientation.

2.2. Instruments

Climate Change Perceptions Scale [

42] measures five dimensions of climate change: the perceived reality, human causes, negative consequences, spatial proximity, and temporal distance of consequences. We used the short version of five items (1 = completely disagree; 5 = completely agree). The items were the following: ‘I believe that climate change is real’ (reality), ‘The main causes of climate change are human activities’ (causes), ‘Climate change will bring about serious negative consequences’ (valence of consequences), ‘My local area will be influenced by climate change’ (spatial distance of consequences),’ It will be a long time before the consequences of climate change are felt’ (temporal distance of consequences. R). ” The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.82.

The Hogg Eco-Anxiety Scale (HEAS-13) [

31] measures anxiety in response to the global environmental crisis through four underlying factors: affective symptoms, behavioral symptoms, negative emotionality, and rumination.

It focuses on enduring and non-pathological forms of anxiety at a high level of abstraction. A 6-month time frame was used in the instructions to ensure the stability of the measure, saying the following: “Over the last six months, how often have you been bothered by the following problems when thinking about climate change and other global environmental conditions (e.g., global warming, ecological degradation, resource depletion, species extinction, ozone hole, pollution of the oceans, deforestation)? Some item examples are the following: “Worrying too much” (affective symptom), “Unable to stop thinking about past events related to climate change” (rumination), “Difficulty working and/or studying” (behavioral symptom), “Feeling anxious about the impact of your behaviors on the earth” (negative emotionality). The range of responses on the scale was the following: 0 = not at all, 1 = several of the days, 2 = over half the days, 3 = nearly every day”. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.91.

Credibility of science. We used a single item asking participants their agreement with the following sentence “I trust the veracity of the information on the climate crisis offered by science”. Responses range from 1 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree.

2.3. Data Analyses

First, to develop a global measure of willingness to behave in favor of the environment, the total sample was randomly divided into two subsamples of the same size. The mean age of the first group is 41.83, with a standard deviation of 15.16. The second subsample has a mean age of 44.07 years and a standard deviation 14.91. We used the first subsample to obtain descriptive statistics for the items and to observe whether they fit the normal distribution. We tested the multivariate normal distribution assumption using the Mardia test in the R software (version 3.6.3 [

54]). Subsequently, after checking the matrix data with the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin coefficient (KMO) and Bartlett’s test—whether there was an adequate intercorrelation between items—we also performed an exploratory factor analysis (EFA). This allowed the examination of the items’ distribution patterns and the underlying dimensions using principal axis estimation and direct oblique rotation [

55]. We retained the dimension numbers based on a parallel analysis and the Goodness of model fit [

56].

Second, a confirmatory factor analysis was performed using R software with the first subsample [

54]. We conducted the CFA using the robust maximum likelihood estimation method. We assessed the model fit using the chi-square (χ2) test, comparative fit index (CFI), the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) with a 90% confidence interval, and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). Values less than or equal to 0.08 and less than or equal to 0.06 for RMSEA indicated an excellent and a good fit, respectively. TLI values higher than 0.95 and between 0.90 and 0.95 indicated the excellent and acceptable fit of the model to the data, respectively. Otherwise, values less than or equal to 0.08 for SRMR indicated an excellent fit [

57]. After confirming that the model fits well, the second sample was used to perform cross-validation. Subsequently, the total sample was also used to obtain factor coefficients through a CFA analysis. The R program was used in these procedures. Later, with the total sample, we calculated the internal consistency for the scale through McDonald’s Omega total coefficients using the Factor 9.2 program.

Third, to check the validity of evidence based on relations with other variables, we calculated the correlations of the GWEBS with climate change perceptions, eco-anxiety, and trust in science. Finally, a parallel mediation analysis was run with the total sample using PROCESS (Version 2; Model 4; [

58] to examine the indirect effect of climate change perceptions (X) on willingness to behave in favor of the environment (Y) based on rates of eco-anxiety (M1) and trust in science (M2), and controlling for the influence of sociodemographic and ideological characteristics (i.e., gender, environmental activism, and political orientation). Following Hayes’ [

58] procedures for testing indirect effects with serial mediators, bias-corrected confidence intervals for indirect associations were estimated based on 5,000 bootstrap samples. A CI that does not include 0 in these models indicates a statistically meaningful association.

3. Results

We started with preliminary and exploratory analyses. In this respect, skewness and kurtosis values for the observed variables (i.e., item) were acceptable in subsample 1. However, the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test (univariate normality) was significant for all items (ps < 0.001), as was the Mardia test (multi-variate normality) (MS = 242.25, p < 0.001; MK = 10.48, p < 0.001), indicating that the samples did not follow a strictly normal distribution (see

Table 1).

Bartlett’s test (χ2 = 638,81, df = 6, p < 0.001) and the KMO coefficient (0.78) in subsample 1 pointed toward an adequate intercorrelation among these items, allowing the interpretation of the factorial solution. Specifically, the EFA resulted in a one-factor solution (eigenvalue of 2.66) that explained 66.5% of the total variance, which is supported acceptably by the goodness-of-fit indices (χ2[6] = 638.81, p < 0.001, TLI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.062, SMRS = 0.03). Likewise, as

Table 1 shows, the items presented suitable factor loadings and discrimination indices (> 0.50).

3.1. Evidence Based on Internal Structure and Relationships with Other Variables

The first subsample was first used to check the one-factor structure. The fit indices obtained were χ2[6] = 291.91, p < 0.001, TLI = 0.98, CFI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.059 90%CI [0.00, 0.20], SMRS = 0.01. With the second subsample, the fit was checked with the following fit indices: χ2[6] = 364.43, p < 0.001, TLI = 0.98, CFI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.069 90%CI [0.00, 0.20], SMRS = 0.01. In both subsamples, all indices indicated a good model fit (Byrne et al., 1989). Finally, to verify the adequacy of the one-factor structure, the analysis was repeated with the entire sample to obtain the estimates (see

Figure 2). The final fit was excellent: χ2[6] = 643.86, p < 0.001, TLI = 0.98, CFI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.061 90%CI [0.00, 0.16], SMRS = 0.01. Likewise, the factor showed an excellent internal consistency of 0.83.

In seeking evidence of validity relative to other variables, the score for the GWEBS was correlated with the total scores obtained by the participants in all the studied variables. As

Table 2 shows, the GWEBS was positively related to climate change perceptions, eco-anxiety, and trust in science.

4. Discussion

There are many perspectives from which the results of this study can be approached, and all are intended and potentially useful. We can focus on the good statistical indicators obtained by our general measure of willingness for environmental behavior, the GWEBS. We can also focus on the full mediating role of eco-anxiety, which becomes a valuable variable in connecting climate change perceptions and the general willingness to act accordingly. It is also possible to observe the results in light of the partial mediating role of trust in science. This metacognition provides security to the beliefs that people have about climate change.

Our main objective was to develop a general measure of willingness for environmental behavior because the existing ones can be considered arbitrary selections of concrete actions made by what the authors consider an excellent description of someone concerned about the environment [

9,

11,

49,

60]. Assessing the willingness for environmental behavior could help better connect constructs of the same level of abstraction, as Fishbein and Azjen [

15] already suggested.

In this respect, the exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses showed a perfect fit for our general four-item scale, the GWEBS, which was not limited to any particular pro-environmental action but rather the general willingness to do, not to do (decreasing), accept social restrictions and ultimately “do your bit” for the environment. This measure can function as a dependent variable, which is how it was used in this study subsequently, and serve to investigate mechanisms that promote it. The GWEBS can also be used as an independent or mediating variable regarding the great diversity of behaviors that people can perform in their particular situations. In this respect, it is necessary to consider that a person can be considered an environmentalist by carrying out different subsets of pro-environmental behaviors, and the GWEBS should be able to explain all of them. This is a straightforward way for future research. In any case, the GWEBS have a reliable one-factor structure that relates well to climate change perceptions, eco-anxiety, and trust in science.

Regarding our second objective, we sought to investigate mechanisms explaining why climate change perceptions do not seem to be associated as frequently as would be desirable with actions [

11]. We tested the mediating role of both eco-anxiety and trust in science. In this respect, we can conclude that eco-anxiety, understood as a non-pathological emotional response of discomfort regarding the global environmental crisis, fully mediated the relationship between climate change perceptions and the GWEBS. That makes eco-anxiety a necessary variable to mobilize the intention to act according to the perception. Second, trusting the veracity of scientific information on climate change partially mediated the relationship between climate change perceptions and the GWEBS. This can be interpreted as saying that climate change perception remains important, but also trust in science. Overall, the tested model shows that eco-anxiety, completely, and trust in science partially contribute to strengthening the desired relationship between the perception of climate change understood as real, negative, proximate, and caused by human beings and the general willingness to take action, operationalized in this study as the willingness to do new pro-environmental actions, to decrease, to accept social restrictions and ultimately to “do your bit.”

We agree that there are many reasons to feel eco-anxiety nowadays [

28], especially if you trust science’s information about the climate crisis [

36,

37]. However, studying how eco-anxiety and trust in science can be channeled into adaptive responses for the person who feels it and the environment is essential. This is considered paramount to address practical issues such as climate change communications and public policies [

12]. Our results contribute to this objective by showing an empirical connection between climate change perceptions and behavioral intentions through a pair of mediating variables: eco-anxiety and trust in science. The first one may be activating a necessary emotional discomfort, and the second may be a cognitive security that may legitimize it.

On a practical level, we can anticipate that changing the people’s behaviors that do not work for the planet may require hope and optimism regarding the solutions. However, according to our results, it also requires distressing discourses that mobilize the necessary doses of non-pathological anxiety that drive action. Parallel trust in science could be reinforced since it works for most people as a confidence heuristic in their thoughts about climate change. Feeling anxious but sure of the causes can mobilize the general desire to act pro-environmentally.

This article has some limitations. First, we acknowledge that willingness for environmental behavior is different from actual enacted behavior. It is an urgently important objective to investigate the connection of the GWEBS with the great diversity of possible pro-environmental behaviors, grouped into very different sets according to the conditions in which each person lives. Nonetheless, studying and promoting the general willingness for environmental behavior is important because communication campaigns can be carried out on the desire to act pro-environmentally regardless of the specific set of behaviors. In this respect, activating general willingness to act could be considered the first step in a chain that ends in specific behaviors. It may not seem like much, but it is important because activating people’s desire to act in a pro-environmental direction can involve many behaviors. Not all of them can be done, but different combinations can. Studying the variables that can predispose people in this direction is necessary and is part of the change.

Secondly, we used a convenience sample and a cross-sectional design, which do not allow us to test for the cause-and-effect relationships hypothesized. Therefore, future lines of research should employ longitudinal designs to overcome these limitations and test the practical implications of our model. It would also be interesting to validate the GWEBS in other age groups, cultural contexts, and languages to explore possible cultural differences in the presented results.

Finally, we know that individuals are not the only actors in the play. Governments and companies also have an important role to play [

61]. However, changes at the individual level are crucial and urgent [

62] because, ultimately, individuals consume, protest, vote, and have the strength to promote important changes when they are a clear majority fully aware of the crisis. The results of this study tell us that there is still work to do so that people perceive and feel the magnitude of scientific data. Despite that, some valuable pieces of information can be extracted. In this respect, eco-anxiety is an unpleasant but necessary emotion that should be activated. So is trust in science that provides heuristically security in the existing information on climate change. Both variables seem to help connect climate change perceptions and willingness to behave accordingly, even when gender, political orientation, and ecological sensitivity are controlled.

5. Conclusions

The present study analyzes the relationship between perceptions of climate change and general willingness for environmental behavior and how eco-anxiety and scientific confidence may moderate this relationship. First, we developed and validated the General Willingness for Environmental Behavior Scale (GWEBS) to do this. This scale, not limited to any specific pro-environmental action, measures the general willingness to act, decrease actions, accept social restrictions, and contribute to the environment. The GWEBS demonstrated a reliable one-factor structure and strongly correlated with climate change perceptions, eco-anxiety, and trust in science.

In second place, the study found that eco-anxiety fully mediated the relationship between climate change perceptions and the GWEBS, making it a crucial variable to mobilize the intention to act following the perception. Trust in science partially mediated the relationship between climate change perceptions and the GWEBS, suggesting that both climate change perception and trust in science are important.

Overall, the model tested in the study indicates that eco-anxiety and trust in science contribute to strengthening the relationship between the perception of climate change and the general willingness to take action. This study provides a clear direction for future research and contributes to our understanding of the psychological mechanisms that drive pro-environmental behavior.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.L.V. and C.D.S.; methodology, M.L.V. and C.D.S.; software, M.L.V. and M.A.F.; validation, M.L.V. and M.A.F.; formal analysis, M.L.V. and M.A.F.; investigation, M.L.V., C.D.S. and L.L.G.; resources, C.D.S. and L.L.G.; data curation, M.L.V. and M.A.F.; writing—original draft preparation, M.L.V.; writing—review and editing, C.D.S.; visualization, C.D.S. and L.L.G.; supervision, M.L.V. and C.D.S.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Universidad Rey Juan Carlos (protocol code 0407202327123, september 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; The Australian National University: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, J.; Oreskes, N.; Doran, P. T.; Anderegg, W. R. L.; Verheggen, B.; Maibach, E. W.; Carlton, J. S.; Lewandowsky, S.; Skuce, A. G.; Green, S. A.; Nuccitelli, D.; Jacobs, P.; Richardson, M.; Winkler, B.; Painting, R.; Rice, K. Consensus on Consensus: A Synthesis of Consensus Estimates on Human-Caused Global Warming. Environ. Res. Lett. 2016, 11 (4). [CrossRef]

- Van der Linden, S. L.; Leiserowitz, A. A.; Feinberg, G. D.; Maibach, E. W. How to communicate the scientific consensus on climate change: plain facts, pie charts or metaphors? Climatic Change 2014 126(1–2), 255–262. [CrossRef]

- Bradley, G. L.; Babutsidze, Z.; Chai, A.; Reser, J. P. The Role of Climate Change Risk Perception, Response Efficacy, and Psychological Adaptation in pro-Environmental Behavior: A Two Nation Study. J. Environ Psychol. 2020, 68, 101410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brügger, A.; Dessai, S.; Devine-Wright, P.; Morton, T. A.; Pidgeon, N. F. Psychological Responses to the Proximity of Climate Change. Nat. Clim. Change. 2015, pp 1031–1037. [CrossRef]

- Lorenzoni, I.; Nicholson-Cole, S.; Whitmarsh, L. Barriers Perceived to Engaging with Climate Change among the UK Public and Their Policy Implications. Global Environ. Change 2007, 17 (3–4), 445–459. [CrossRef]

- Leiserowitz, A. Climate Change Risk Perception and Policy Preferences: The Role of Affect, Imagery, and Values. Clim. Change; 2006, 77, 45–72. [CrossRef]

- Spence, A.; Poortinga, W.; Pidgeon, N. The Psychological Distance of Climate Change. Risk Analysis 2012, 32(6), 957–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobler, C.; Visschers, V. H. M.; Siegrist, M. Addressing Climate Change: Determinants of Consumers’ Willingness to Act and to Support Policy Measures. J. Environ Psychol. 2012, 32(3), 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Linden, S. The Social-Psychological Determinants of Climate Change Risk Perceptions: Towards a Comprehensive Model. J. Environ Psychol. 2015, 41, 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, B.; Brewer, M. B.; Hayes, B. K.; McDonald, R. I.; Newell, B. R. Predicting Climate Change Risk Perception and Willingness to Act. J. Environ Psychol. 2019, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Eck, C. W.; Mulder, B. C.; van der Linden, S. Climate Change Risk Perceptions of Audiences in the Climate Change Blogosphere. Sustainability 2020, 12(19), 7990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, P.; Tarafder, T.; Pearson, D.; Henryks, J. Intention-Behaviour Gap and Perceived Behavioural Control-Behaviour Gap in Theory of Planned Behaviour: Moderating Roles of Communication, Satisfaction and Trust in Organic Food Consumption. Food Qual. Prefer. 2020, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. From Intentions to Actions: A Theory of Planned Behavior. In Action control: From cognition to behavior; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 1985; pp. 11–39. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research. Read. PA Addison Wesley 1975, 6, 244–245. [Google Scholar]

- Babutsidze, Z.; Chai, A. Look at Me Saving the Planet! The Imitation of Visible Green Behavior and Its Impact on the Climate Value-Action Gap. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 146, 290–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T. H.; Jan, F. H.; Huang, G. W. The Influence of Recreation Experiences on Environmentally Responsible Behavior: The Case of Liuqiu Island, Taiwan. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 947–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maartensson, H.; Loi, N. M. Exploring the Relationships between Risk Perception, Behavioural Willingness, and Constructive Hope in pro-Environmental Behaviour. Environ. Educ. Res. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Climate Change Impacts on Mental Health in Europe; 2020.

- Haaland, T.N. Growing up to a Disaster–How the Youth Conceptualize Life and Their Future in Anticipation of Climate Change; University of Stavanger: Stavanger, Norway, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrance, E.; Thompson, R.; Fontana, G.; Jennings, N. The Impact of Climate Change on Mental Health and Emotional Wellbeing: Current Evidence and Implications for Policy and Practice; 2021.

- Leiserowitz, A.; Maibach, E.; Rosenthal, S.; Kotcher, J.; Ballew, M.; Goldberg, M.; Gustafson, A. Climate Change in the American Mind: December 2018. Yale University and George Mason University. New Haven, CT: Yale Program on Climate Change Communication, 48. 2018.

- Durkalec, A.; Furgal, C.; Skinner, M. W.; Sheldon, T. Climate Change Influences on Environment as a Determinant of Indigenous Health: Relationships to Place, Sea Ice, and Health in an Inuit Community. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 136, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, K. E.; Barnett, J.; Haslam, N.; Kaplan, I. The Mental Health Impacts of Climate Change: Findings from a Pacific Island Atoll Nation. J. Anxiety Disord. 2020, 73, 102237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, F.; Song, L. Environmental Concern in China: A Multilevel Analysis. Chin. Sociol. Rev. 2020, 52, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S. Climate Anxiety: Psychological Responses to Climate Change. J. Anxiety Disord. 2020, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hickman, C. We Need to (Find a Way to) Talk about … Eco-Anxiety. J. Soc. Work Pract. 2020, 34(4), 411–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihkala, P. Anxiety and the Ecological Crisis: An Analysis of Eco-Anxiety and Climate Anxiety. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2020, 12 (19). [CrossRef]

- Boluda-Verdú, I.; Senent-Valero, M.; Casas-Escolano, M.; Matijasevich, A.; Pastor-Valero, M. Fear for the Future: Eco-Anxiety and Health Implications, a Systematic Review. J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 84, 101904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S.; Karazsia, B. T. Development and Validation of a Measure of Climate Change Anxiety. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, T. L.; Stanley, S. K.; O’Brien, L. V.; Wilson, M. S.; Watsford, C. R. The Hogg Eco-Anxiety Scale: Development and Validation of a Multidimensional Scale. Global Environ. Change 2021, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurth, C.; Pihkala, P. Eco-Anxiety: What It Is and Why It Matters. Frontiers in Psychology. Frontiers Media S.A. September 23, 2022. 23 September. [CrossRef]

- Parreira, N.; Mouro, C. Living by the Sea: Place Attachment, Coastal Risk Perception, and Eco-Anxiety When Coping with Climate Change. Front Psychol 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verplanken, B.; Marks, E.; Dobromir, A. I. On the Nature of Eco-Anxiety: How Constructive or Unconstructive Is Habitual Worry about Global Warming? J Environ Psychol 2020, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunbode, C. A.; Doran, R.; Hanss, D.; Ojala, M.; Salmela-Aro, K.; van den Broek, K. L.; Bhullar, N.; Aquino, S. D.; Marot, T.; Schermer, J. A.; Wlodarczyk, A.; Lu, S.; Jiang, F.; Maran, D. A.; Yadav, R.; Ardi, R.; Chegeni, R.; Ghanbarian, E.; Zand, S.; Najafi, R.; Park, J.; Tsubakita, T.; Tan, C. S.; Chukwuorji, J. B. C.; Ojewumi, K. A.; Tahir, H.; Albzour, M.; Reyes, M. E. S.; Lins, S.; Enea, V.; Volkodav, T.; Sollar, T.; Navarro-Carrillo, G.; Torres-Marín, J.; Mbungu, W.; Ayanian, A. H.; Ghorayeb, J.; Onyutha, C.; Lomas, M. J.; Helmy, M.; Martínez-Buelvas, L.; Bayad, A.; Karasu, M. Climate Anxiety, Wellbeing and pro-Environmental Action: Correlates of Negative Emotional Responses to Climate Change in 32 Countries. J Environ Psychol 2022, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buys, L.; Aird, R.; van Megen, K.; Miller, E.; Sommerfeld, J. Perceptions of Climate Change and Trust in Information Providers in Rural Australia. Public Understanding of Sc. 2014, 23(2), 170–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiserowitz, A.; Maibach, E. W.; Roser-Renouf, C.; Feinberg, G.; Howe, P. Climate Change in the American Mind: Americans’ Global Warming Beliefs and Attitudes in April 2013. SSRN Electronic Journal 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderegg, W. R. L.; Prall, J. W.; Harold, J.; Schneider, S. H. Expert credibility in climate change. Proceedings of the Nat. Academy of Sci. of the USA. 2010, 107(27), 12107–12109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doran, P. T.; Zimmerman, M. K. Examining the scientific consensus on climate change. In Eos 2009, 90(3) pp. 22–23. [CrossRef]

- Leviston, Z.; Price, J.; Malkin, S.; McCrea, R. Fourth annual survey of Australian attitudes to climate change: Interim report. CSIR0: Perth, Australia, 2014.

- Steg, L. Limiting Climate Change Requires Research on Climate Action. Nat Clim Chang 2018, 8(9), 759–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Valkengoed, A. M.; Steg, L.; Perlaviciute, G. Development and Validation of a Climate Change Perceptions Scale. J. Environ Psychol. 2021, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briñol, P.; Petty R., E. Source Factors in Persuasion: A Self-Validation Approach. Eur Rev Soc Psychol 2009, 20(1), 49–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petty, R. E.; Briñol, P. The Elaboration Likelihood and Metacognitive Models of Attitudes. Dual-process theories of the social mind 2014, 172–187.

- Brewer, P. R.; Ley, B. L. Whose Science Do You Believe? Explaining Trust in Sources of Scientific Information about the Environment. Sci Commun 2013, 35(1), 115–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hmielowski, J. D.; Feldman, L.; Myers, T. A.; Leiserowitz, A.; Maibach, E. An Attack on Science? Media

Use, Trust in Scientists, and Perceptions of Global Warming. Public Understanding of Science 2014, 23 (7),

866–883. [CrossRef]

- Malka, A.; Krosnick, J. A.; Langer, G. The Association of Knowledge with Concern about Global Warming: Trusted Information Sources Shape Public Thinking. Risk Analysis 2009, 29(5), 633–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, L. C.; Hartter, J.; Saito, K. Trust in Scientists on Climate Change and Vaccines. Sage Open 2015, 5 (3). [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, M. H.; Carmichael, C. L.; Lacroix, K.; Gustafson, A.; Rosenthal, S. A.; Leiserowitz, A. Perceptions and Correspondence of Climate Change Beliefs and Behavior among Romantic Couples. J Environ Psychol 2022, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparks, A. C.; Ehret, P. J.; Brick, C. Measuring Pro-Environmental Orientation Measuring pro-Environmental Orientation: Testing and Building Scales. J Environ Psychol 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brody, S. D.; Zahran, S.; Vedlitz, A.; Grover, H. Examining the Relationship between Physical Vulnerability and Public Perceptions of Global Climate Change in the United States. Environ Behav 2008, 40(1), 72–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundblad, E. L.; Biel, A.; Gärling, T. Cognitive and Affective Risk Judgements Related to Climate Change. J Environ Psychol 2007, 27(2), 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A. G. Statistical Power Analyses Using GPower 3.1: Tests for Correlation and Regression Analyses. Behav Res Methods 2009, 41 (4), 1149–1160. [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. https://Www.R-Project.Org/ 2017.

- Osborne, J. W. Best Practices in Exploratory Factor Analysis; Create Space Independent Publishing, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Brown, T. A. Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research; The Guilford Press, 2015.

- MacCallum, R. C.; Browne, M. W.; Sugawara, H. M. Power Analysis and Determination of Sample Size for Covariance Structure Modeling. Psychol Methods 1996, 1(2), 130–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; The Guilford Press, 2013. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24018134.

- Byrne, B. M.; Shavelson, R. J.; Muthén, B. Testing for the Equivalence of Factor Covariance and Mean Structures: The Issue of Partial Measurement In Variance. Psychol Bull 1989, 105(3), 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, S.; Rees, J.; Seebauer, S. Collective Climate Action: Determinants of Participation Intention in Community-Based pro-Environmental Initiatives. J Environ Psychol 2015, 43, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadez, S.; Czerny, A.; Letmathe, P. Stakeholder Pressures and Corporate Climate Change Mitigation Strategies. Bus Strategy Environ 2019, 28(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilandzic, H.; Kalch, A.; Soentgen, J. Effects of Goal Framing and Emotions on Perceived Threat and Willingness to Sacrifice for Climate Change. Sci Commun 2017, 39(4), 466–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).