Submitted:

25 February 2024

Posted:

07 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

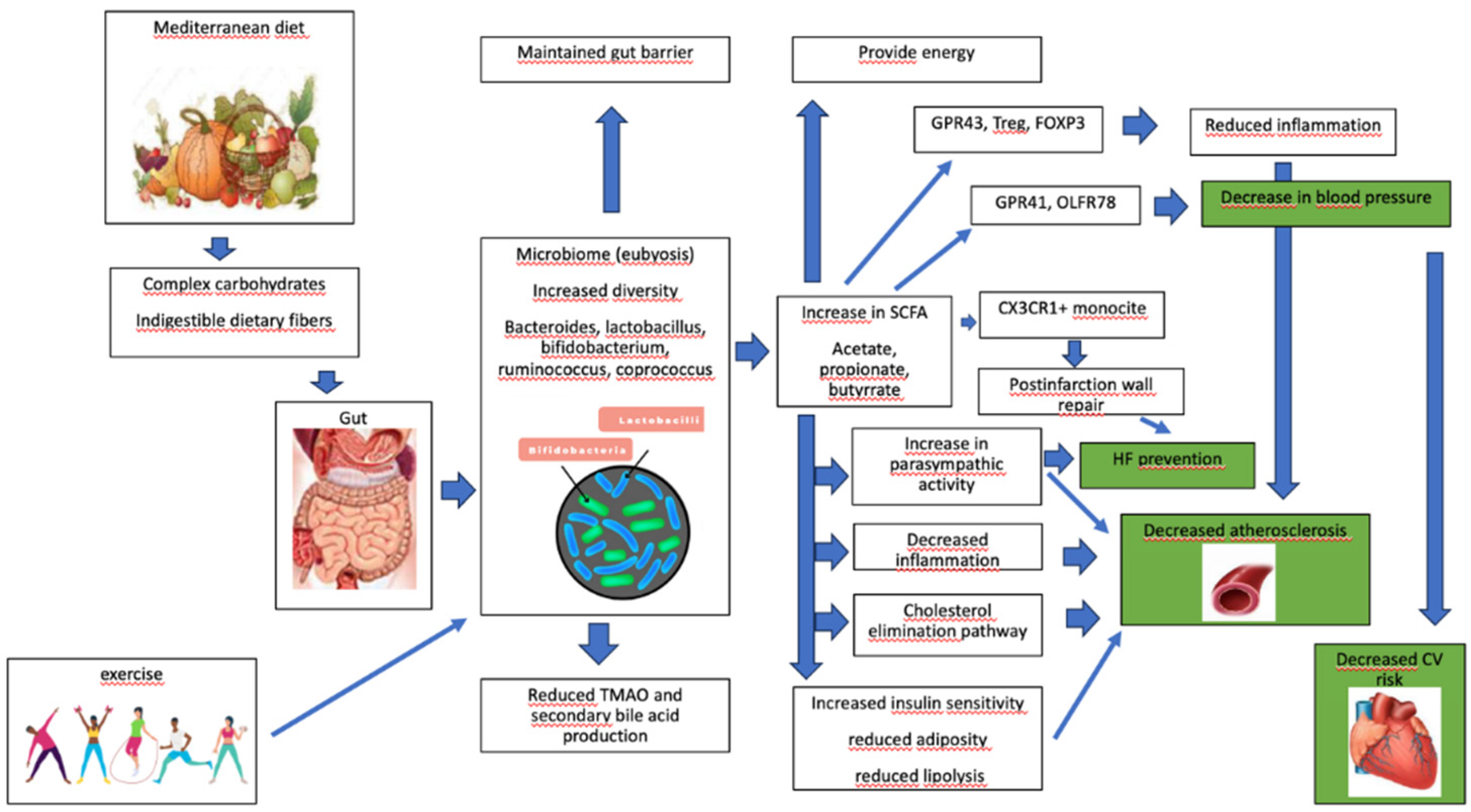

2. The Mediterranean Diet Components

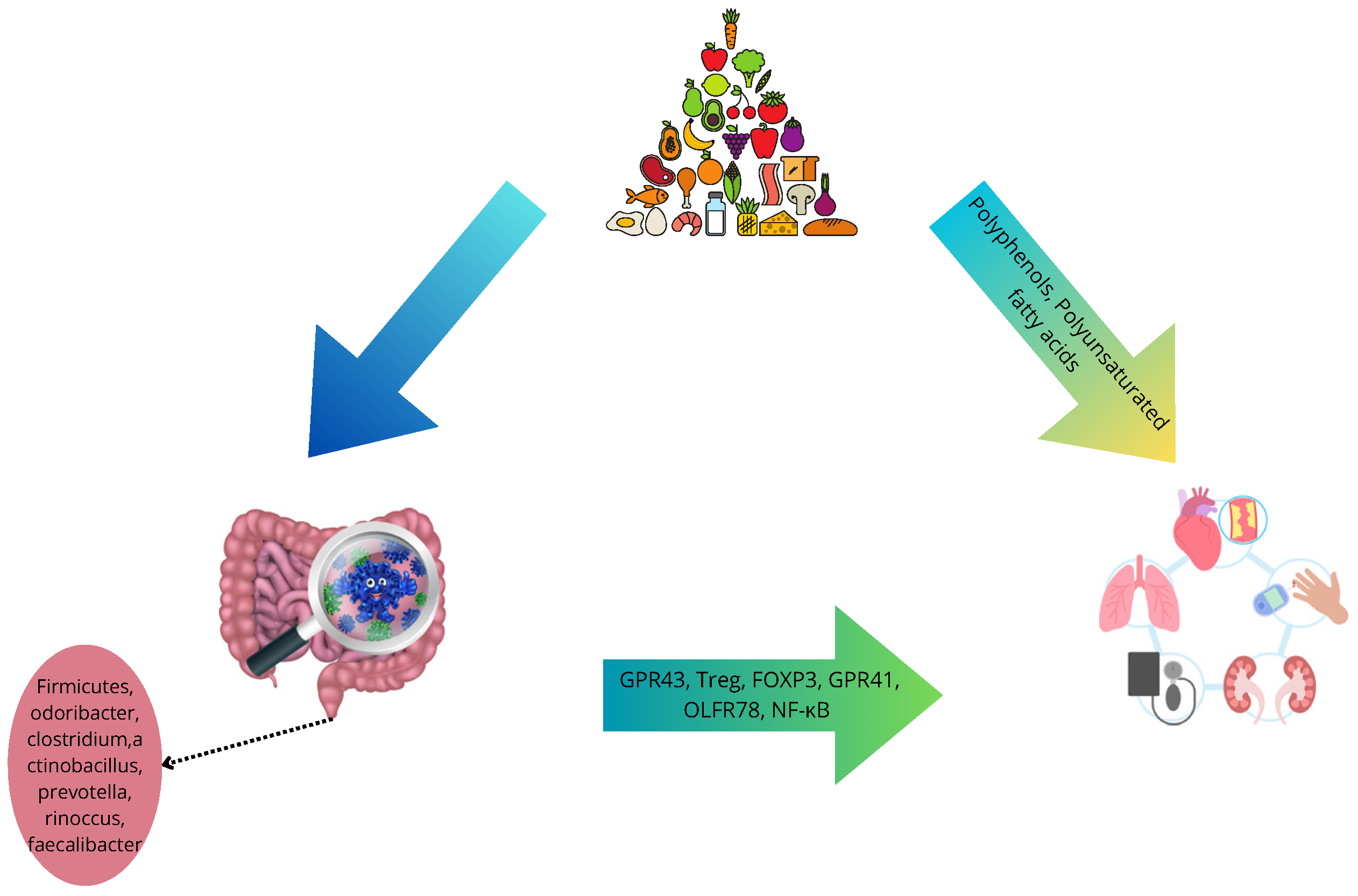

2.1. Extra-Virgin Olive Oil (EVOO)

2.2. Legumes, Cereals, and Nuts

2.3. Fruits and Vegetables

2.4. Dairy Products

2.5. Fish

3.1. Wine

4. MD and Cardiovascular Outcomes: Clinical, Epidemiological and Intervention Studies

5. Favorable Mechanisms of MD on Cardiovascular Health

6. Microbiota: Definitions and Functions

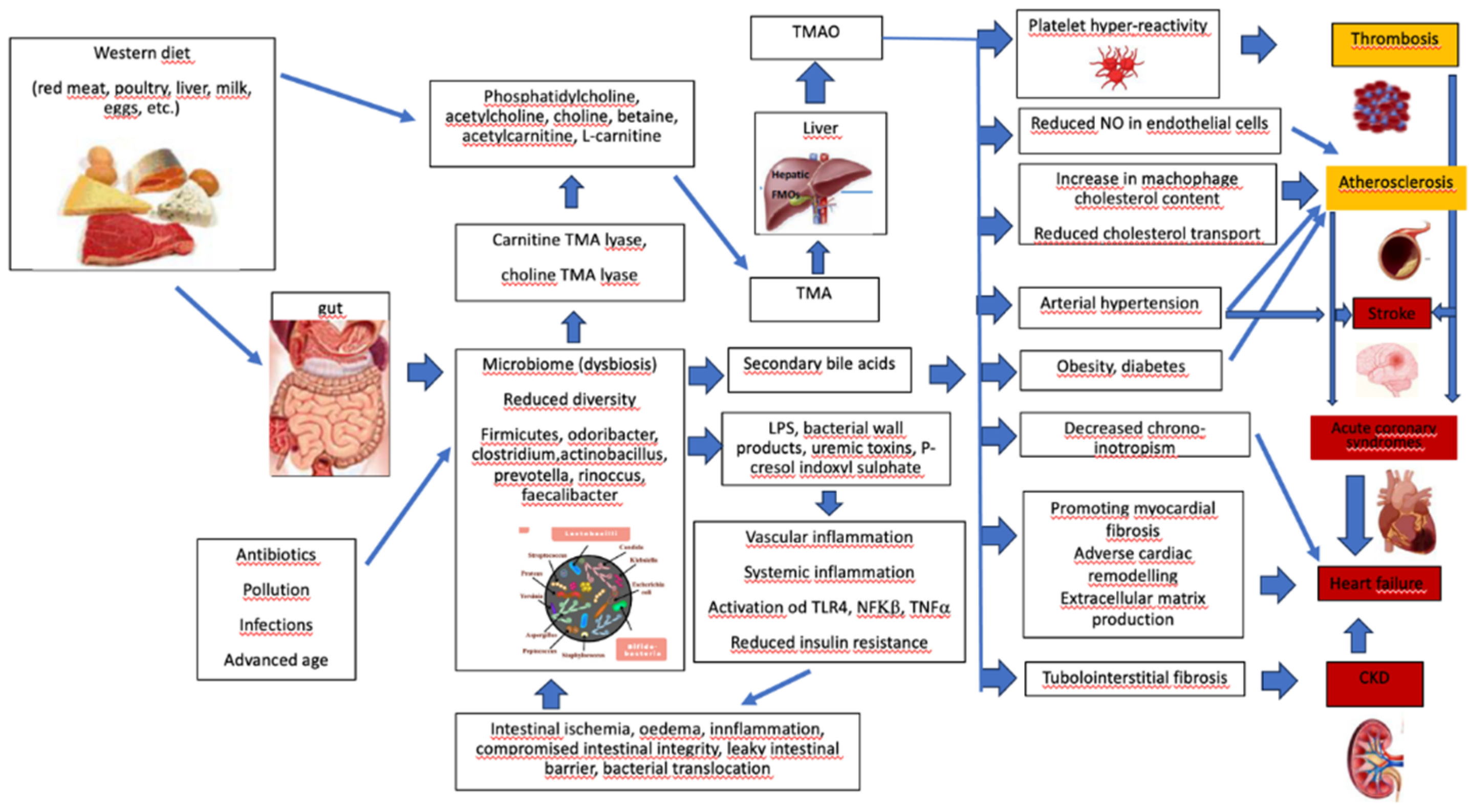

7. Western Diet, Microbiome, and Cardiovascular Diseases

8. Effects of Mediterreanen Diet on Microbiome

9. MD, Microbiome, and Cardiovascular Health

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Davis C, Bryan J, Hodgson J, Murphy K. Definition of the Mediterranean Diet; A Literature Review. Nutrients. 2015, 7, 9139–9153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bach-Faig A, Berry EM, Lairon D, et al. Mediterranean diet pyramid today. Science and cultural updates. Public. Health Nutr. 2011, 14, 2274–2284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meslier V, Laiola M, Roager HM, et al. Mediterranean diet intervention in overweight and obese subjects lowers plasma cholesterol and causes changes in the gut microbiome and metabolome independently of energy intake. Gut. 2020, 69, 1258–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh TS, Rampelli S, Jeffery IB, et al. Mediterranean diet intervention alters the gut microbiome in older people reducing frailty and improving health status: the NU-AGE 1-year dietary intervention across five European countries. Gut. 2020, 69, 1218–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiani AK, Medori MC, Bonetti G, et al. Modern vision of the Mediterranean diet. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2022, 63, 2S3:E36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucciantini M, Leri M, Nardiello P, Casamenti F, Stefani M. Olive Polyphenols: Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Properties. Antioxidants. 2021, 10, 1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casamenti F, Stefani M. Olive polyphenols: new promising agents to combat aging-associated neurodegeneration. Expert. Rev. Neurother. 2017, 17, 345–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes S, Prasain J, D’Alessandro T, et al. The metabolism and analysis of isoflavones and other dietary polyphenols in foods and biological systems. Food Funct. 2011, 2, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng Y, Hou C, Yang Z, et al. Hydroxytyrosol mildly improve cognitive function independent of APP processing in APP/PS1 mice. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2016, 60, 2331–2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Alarcon SA, Valenzuela R, Valenzuela A, Videla LA. Liver Protective Effects of Extra Virgin Olive Oil: Interaction between Its Chemical Composition and the Cell-signaling Pathways Involved in Protection. Endocr. Metab. Immune Disord—Drug Targets. 2017, 18, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadmehrabi S, Tang WHW. Gut microbiome and its role in cardiovascular diseases. Curr. Opin. Cardiol. 2017, 32, 761–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hornedo-Ortega R, Cerezo AB, De Pablos RM, et al. Phenolic Compounds Characteristic of the Mediterranean Diet in Mitigating Microglia-Mediated Neuroinflammation. Front. Cell Neurosci, 2018; 12, 373. [CrossRef]

- Naureen Z, Capodicasa N, Paolacci S, et al. Prevention of the proliferation of oral pathogens due to prolonged mask use based on α-cyclodextrin and hydroxytyrosol mouthwash. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2021, 25 (Suppl. S1), 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, G. The role of polyphenols in modern nutrition. Nutr. Bull. 2017, 42, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loke WM, Hodgson JM, Proudfoot JM, McKinley AJ, Puddey IB, Croft KD. Pure dietary flavonoids quercetin and (−)-epicatechin augment nitric oxide products and reduce endothelin-1 acutely in healthy men. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 88, 1018–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg T, Abdellatif M, Schroeder S, et al. Cardioprotection and lifespan extension by the natural polyamine spermidine. Nat. Med. 2016, 22, 1428–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira A, Maraschin M. Banana (Musa spp) from peel to pulp: Ethnopharmacology, source of bioactive compounds and its relevance for human health. J. Ethnopharmacol, 2015; 160, 149–163. [CrossRef]

- Thorburn AN, Macia L, Mackay CR. Diet, Metabolites, and “Western-Lifestyle” Inflammatory Diseases. Immunity. 2014, 40, 833–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clinton SK, Giovannucci EL, Hursting SD. The World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research Third Expert Report on Diet, Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Cancer: Impact and Future Directions. J. Nutr. 2020, 150, 663–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surh, Y.J. Cancer chemoprevention with dietary phytochemicals. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2003, 3, 768–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şanlier N, Gökcen BB, Sezgin AC. Health benefits of fermented foods. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 59, 506–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barengolts E, Smith E, Reutrakul S, Tonucci L, Anothaisintawee T. The Effect of Probiotic Yogurt on Glycemic Control in Type 2 Diabetes or Obesity: A Meta-Analysis of Nine Randomized Controlled Trials. Nutrients. 2019, 11, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira DL, Costabile A, Wilbey RA, Grandison AS, Duarte LC, Roseiro LB. In vitro evaluation of the fermentation properties and potential prebiotic activity of caprine cheese whey oligosaccharides in batch culture systems. BioFactors. 2012, 38, 440–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cani P, Delzenne N. The Role of the Gut Microbiota in Energy Metabolism and Metabolic Disease. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2009, 15, 1546–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang L, Wang J, Xiong K, Xu L, Zhang B, Ma A. Intake of Fish and Marine n-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease Mortality: A Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. Nutrients. 2021, 13, 2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siscovick DS, Barringer TA, Fretts AM, et al. Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid (Fish Oil) Supplementation and the Prevention of Clinical Cardiovascular Disease: A Science Advisory From the American Heart Association. Circulation, 2017; 135. [CrossRef]

- Detopoulou P, Demopoulos CA, Antonopoulou S. Micronutrients, Phytochemicals and Mediterranean Diet: A Potential Protective Role against COVID-19 through Modulation of PAF Actions and Metabolism. Nutrients. 2021, 13, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vázquez-Fresno R, Llorach R, Perera A, et al. Clinical phenotype clustering in cardiovascular risk patients for the identification of responsive metabotypes after red wine polyphenol intake. J. Nutr. Biochem, 2016; 28, 114–120. [CrossRef]

- Morselli E, Mariño G, Bennetzen MV, et al. Spermidine and resveratrol induce autophagy by distinct pathways converging on the acetylproteome. J. Cell Biol. 2011, 192, 615–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corella D, Coltell O, Macian F, Ordovás JM. Advances in Understanding the Molecular Basis of the Mediterranean Diet Effect. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 9, 227–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Meyer GRY, Grootaert MOJ, Michiels CF, Kurdi A, Schrijvers DM, Martinet W. Autophagy in Vascular Disease. Circ. Res. 2015, 116, 468–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razani B, Feng C, Coleman T, et al. Autophagy Links Inflammasomes to Atherosclerotic Progression. Cell Metab. 2012, 15, 534–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cangemi R, Miglionico M, D’Amico T, et al. Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet in Preventing Major Cardiovascular Events in Patients with Ischemic Heart Disease: The EVA Study. Nutrients. 2023, 15, 3150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaccio M, Di Castelnuovo A, Pounis G, et al. High adherence to the Mediterranean diet is associated with cardiovascular protection in higher but not in lower socioeconomic groups: prospective findings from the Moli-sani study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 46, 1478–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagiotakos DB, Chrysohoou C, Pitsavos C, et al. The association of Mediterranean diet with lower risk of acute coronary syndromes in hypertensive subjects. Int. J. Cardiol. 2002, 82, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panagiotakos DB, Arapi S, Pitsavos C, et al. The relationship between adherence to the Mediterranean diet and the severity and short-term prognosis of acute coronary syndromes (ACS): The Greek Study of ACS (The GREECS). Nutrition, 2006; 22, 722–730. [CrossRef]

- Pitsavos C, Panagiotakos DB, Chrysohoou C, et al. The effect of Mediterranean diet on the risk of the development of acute coronary syndromes in hypercholesterolemic people: a case–control study (CARDIO2000). Coron. Artery Dis. 2002, 13, 295–300. [CrossRef]

- Tektonidis TG, Åkesson A, Gigante B, Wolk A, Larsson SC. A Mediterranean diet and risk of myocardial infarction, heart failure and stroke: A population-based cohort study. Atherosclerosis. 2015, 243, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-González MA, García-López M, Bes-Rastrollo M, et al. Mediterranean diet and the incidence of cardiovascular disease: A Spanish cohort. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. Published online January 21, 2010:S0939475309002403. [CrossRef]

- Miró Ò, Estruch R, Martín-Sánchez FJ, et al. Adherence to Mediterranean Diet and All-Cause Mortality After an Episode of Acute Heart Failure. JACC Heart Fail. 2018, 6, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waldeyer C, Brunner FJ, Braetz J, et al. Adherence to Mediterranean diet, high-sensitive C-reactive protein, and severity of coronary artery disease: Contemporary data from the INTERCATH cohort. Atherosclerosis, 2018; 275, 256–261. [CrossRef]

- Levitan EB, Lewis CE, Tinker LF, et al. Mediterranean and DASH Diet Scores and Mortality in Women With Heart Failure: The Women’s Health Initiative. Circ. Heart Fail. 2013, 6, 1116–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shikany JM, Safford MM, Bryan J, et al. Dietary Patterns and Mediterranean Diet Score and Hazard of Recurrent Coronary Heart Disease Events and All-Cause Mortality in the REGARDS Study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2018, 7, e008078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodge AM, Bassett JK, Dugué PA, et al. Dietary inflammatory index or Mediterranean diet score as risk factors for total and cardiovascular mortality. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2018, 28, 461–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang CY, Lee CL, Liu WJ, Wang JS. Association of Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet with All-Cause Mortality in Subjects with Heart Failure. Nutrients. 2022, 14, 842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung TT, Rexrode KM, Mantzoros CS, Manson JE, Willett WC, Hu FB. Mediterranean Diet and Incidence of and Mortality From Coronary Heart Disease and Stroke in Women. Circulation. 2009, 119, 1093–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang KW, Lee CL, Liu WJ. Lower All-Cause Mortality for Coronary Heart or Stroke Patients Who Adhere Better to Mediterranean Diet-An NHANES Analysis. Nutrients. 2022, 14, 3203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong TYN, Wareham NJ, Khaw KT, Imamura F, Forouhi NG. Prospective association of the Mediterranean diet with cardiovascular disease incidence and mortality and its population impact in a non-Mediterranean population: the EPIC-Norfolk study. BMC Med. 2016, 14, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefler D, Malyutina S, Kubinova R, et al. Mediterranean diet score and total and cardiovascular mortality in Eastern Europe: the HAPIEE study. Eur. J. Nutr. 2017, 56, 421–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lorgeril M, Salen P, Martin JL, Monjaud I, Delaye J, Mamelle N. Mediterranean Diet, Traditional Risk Factors, and the Rate of Cardiovascular Complications After Myocardial Infarction: Final Report of the Lyon Diet Heart Study. Circulation. 1999, 99, 779–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-González MA, Fernández-Jarne E, Serrano-Martínez M, Marti A, Martinez JA, Martín-Moreno JM. Mediterranean diet and reduction in the risk of a first acute myocardial infarction: an operational healthy dietary score. Eur. J. Nutr. 2002, 41, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgado-Lista J, Alcala-Diaz JF, Torres-Peña JD, et al. Long-term secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a Mediterranean diet and a low-fat diet (CORDIOPREV): a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. 2022, 399, 1876–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rees K, Takeda A, Martin N, et al. Mediterranean-style diet for the primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Heart Group, ed. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev, 2019; 2019. [CrossRef]

- Gupta UC, Gupta SC, Gupta SS. An Evidence Base for Heart Disease Prevention using a MediterraneanDiet Comprised Primarily of Vegetarian Food. Recent. Adv. Food Nutr. Agric. 2023, 14, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laffond A, Rivera-Picón C, Rodríguez-Muñoz PM, et al. Mediterranean Diet for Primary and Secondary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease and Mortality: An Updated Systematic Review. Nutrients. 2023, 15, 3356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saulle R, Lia L, De Giusti M. A systematic overview of the scientific literature on the association between Mediterranean Diet and the Stroke prevention. Clin. Ter, 2019; 396–408. [CrossRef]

- Liyanage T, Ninomiya T, Wang A, et al. Effects of the Mediterranean Diet on Cardiovascular Outcomes—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Wright JM, ed. PLOS ONE. 2016, 11, e0159252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Gonzalez MA, Bes-Rastrollo M. Dietary patterns, Mediterranean diet, and cardiovascular disease. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 2014, 25, 20–26. [CrossRef]

- Grosso G, Marventano S, Yang J, et al. A comprehensive meta-analysis on evidence of Mediterranean diet and cardiovascular disease: Are individual components equal? Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 3218–3232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosato V, Temple NJ, La Vecchia C, Castellan G, Tavani A, Guercio V. Mediterranean diet and cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Eur. J. Nutr. 2019, 58, 173–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pant A, Gribbin S, McIntyre D, et al. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in women with a Mediterranean diet: systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart. 2023, 109, 1208–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinu M, Pagliai G, Casini A, Sofi F. Mediterranean diet and multiple health outcomes: an umbrella review of meta-analyses of observational studies and randomised trials. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 72, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- La Torre G, Saulle R, Di Murro F, et al. Mediterranean diet adherence and synergy with acute myocardial infarction and its determinants: A multicenter case-control study in Italy. Lazzeri C, ed. PLOS ONE. 2018, 13, e0193360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korakas E, Dimitriadis G, Raptis A, Lambadiari V. Dietary Composition and Cardiovascular Risk: A Mediator or a Bystander? Nutrients. 2018, 10, 1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-González MÁ, Ruiz-Canela M, Hruby A, Liang L, Trichopoulou A, Hu FB. Intervention Trials with the Mediterranean Diet in Cardiovascular Prevention: Understanding Potential Mechanisms through Metabolomic Profiling. J. Nutr. 2016, 146, 913S–919S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gepner Y, Shelef I, Komy O, et al. The beneficial effects of Mediterranean diet over low-fat diet may be mediated by decreasing hepatic fat content. J. Hepatol. 2019, 71, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whayne, T.F. Ischemic Heart Disease and the Mediterranean Diet. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 2014, 16, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galié S, García-Gavilán J, Papandreou C, et al. Effects of Mediterranean Diet on plasma metabolites and their relationship with insulin resistance and gut microbiota composition in a crossover randomized clinical trial. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 3798–3806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitó M, Estruch R, Salas-Salvadó J, et al. Effect of the Mediterranean diet on heart failure biomarkers: a randomized sample from the PREDIMED trial. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2014, 16, 543–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solá R, Fitó M, Estruch R, et al. Effect of a traditional Mediterranean diet on apolipoproteins B, A-I, and their ratio: A randomized, controlled trial. Atherosclerosis. 2011, 218, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casas R, Sacanella E, Urpí-Sardà M, et al. The Effects of the Mediterranean Diet on Biomarkers of Vascular Wall Inflammation and Plaque Vulnerability in Subjects with High Risk for Cardiovascular Disease. A Randomized Trial. Hribal ML, ed. PLoS ONE. 2014, 9, e100084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giroli MG, Werba JP, Risé P, et al. Effects of Mediterranean Diet or Low-Fat Diet on Blood Fatty Acids in Patients with Coronary Heart Disease. A Randomized Intervention Study. Nutrients. 2021, 13, 2389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuttolomondo A, Simonetta I, Daidone M, Mogavero A, Ortello A, Pinto A. Metabolic and Vascular Effect of the Mediterranean Diet. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlos S, De La Fuente-Arrillaga C, Bes-Rastrollo M, et al. Mediterranean Diet and Health Outcomes in the SUN Cohort. Nutrients. 2018, 10, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai J, Lampert R, Wilson PW, Goldberg J, Ziegler TR, Vaccarino V. Mediterranean Dietary Pattern Is Associated With Improved Cardiac Autonomic Function Among Middle-Aged Men: A Twin Study. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes. 2010, 3, 366–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Giosia P, Stamerra CA, Giorgini P, Jamialahamdi T, Butler AE, Sahebkar A. The role of nutrition in inflammaging. Ageing Res. Rev, 2022; 77, 101596. [CrossRef]

- Kerley, C.P. Dietary patterns and components to prevent and treat heart failure: a comprehensive review of human studies. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2019, 32, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giugliano D, Esposito K. Mediterranean Diet and Cardiovascular Health. Ann. N. Y Acad. Sci. 2005, 1056, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itsiopoulos C, Mayr HL, Thomas CJ. The anti-inflammatory effects of a Mediterranean diet: a review. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care. 2022, 25, 415–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yubero-Serrano EM, Fernandez-Gandara C, Garcia-Rios A, et al. Mediterranean diet and endothelial function in patients with coronary heart disease: An analysis of the CORDIOPREV randomized controlled trial. Rahimi K, ed. PLOS Med. 2020, 17, e1003282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrail L, Garelnabi M. Polyphenolic Compounds and Gut Microbiome in Cardiovascular Diseases. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2020, 21, 578–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turpin W, Dong M, Sasson G, et al. Mediterranean-Like Dietary Pattern Associations With Gut Microbiome Composition and Subclinical Gastrointestinal Inflammation. Gastroenterology. 2022, 163, 685–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Díaz I, Fernández-Navarro T, Sánchez B, Margolles A, González S. Mediterranean diet and faecal microbiota: a transversal study. Food Funct. 2016, 7, 2347–2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson LA, Izuora K, Basu A. Mediterranean Diet and Its Association with Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 2022, 19, 12762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogel RA, Corretti MC, Plotnick GD. The postprandial effect of components of the mediterranean diet on endothelial function. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2000, 36, 1455–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shannon OM, Mendes I, KÖchl C, et al. Mediterranean Diet Increases Endothelial Function in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Nutr. 2020, 150, 1151–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yubero-Serrano EM, Fernandez-Gandara C, Garcia-Rios A, et al. Mediterranean diet and endothelial function in patients with coronary heart disease: An analysis of the CORDIOPREV randomized controlled trial. Rahimi K, ed. PLOS Med. 2020, 17, e1003282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattioli AV, Palmiero P, Manfrini O, et al. Mediterranean diet impact on cardiovascular diseases: a narrative review. J. Cardiovasc. Med. 2017, 18, 925–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu Y, Milner M, Klonizakis M. Physiological effects of a short-term lifestyle intervention based on the Mediterranean diet: comparison between older and younger healthy, sedentary adults. Nutrition, 2018; 55–56, 185–191. [CrossRef]

- Jimenez-Torres J, Alcalá-Diaz JF, Torres-Peña JD, et al. Mediterranean Diet Reduces Atherosclerosis Progression in Coronary Heart Disease: An Analysis of the CORDIOPREV Randomized Controlled Trial. Stroke. 2021, 52, 3440–3449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosti V, Bertozzi B, Fontana L. Health Benefits of the Mediterranean Diet: Metabolic and Molecular Mechanisms. J. Gerontol. Ser. A. 2018, 73, 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin Q, Black A, Kales SN, Vattem D, Ruiz-Canela M, Sotos-Prieto M. Metabolomics and Microbiomes as Potential Tools to Evaluate the Effects of the Mediterranean Diet. Nutrients. 2019, 11, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang WHW, Li DY, Hazen SL. Dietary metabolism, the gut microbiome, and heart failure. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2019, 16, 137–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drapkina OM, Ashniev GA, Zlobovskaya OA, et al. Diversities in the Gut Microbial Patterns in Patients with Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Diseases and Certain Heart Failure Phenotypes. Biomedicines. 2022, 10, 2762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asensio EM, Ortega-Azorín C, Barragán R, et al. Association between Microbiome-Related Human Genetic Variants and Fasting Plasma Glucose in a High-Cardiovascular-Risk Mediterranean Population. Medicina (Mex). 2022, 58, 1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beale AL, O’Donnell JA, Nakai ME, et al. The Gut Microbiome of Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2021, 10, e020654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katsimichas T, Antonopoulos AS, Katsimichas A, Ohtani T, Sakata Y, Tousoulis D. The intestinal microbiota and cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc. Res. 2019, 115, 1471–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alam MJ, Puppala V, Uppulapu SK, Das B, Banerjee SK. Human microbiome and cardiovascular diseases. In: Progress in Molecular Biology and Translational Science. Vol 192. Elsevier; 2022:231-279. [CrossRef]

- Masenga SK, Povia JP, Lwiindi PC, Kirabo A. Recent Advances in Microbiota-Associated Metabolites in Heart Failure. Biomedicines. 2023, 11, 2313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou W, Cheng Y, Zhu P, Nasser MI, Zhang X, Zhao M. Implication of Gut Microbiota in Cardiovascular Diseases. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2020; 2020, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Lv S, Wang Y, Zhang W, Shang H. Trimethylamine oxide: a potential target for heart failure therapy. Heart. 2022, 108, 917–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan A, Hazen SL. Gut Microbiota Involvement in Ventricular Remodeling Post–Myocardial Infarction: New Insights Into How to Heal a Broken Heart. Circulation. 2019, 139, 660–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang W, Dong XY, Huang R. Gut Microbiota in Ischemic Stroke: Role of Gut Bacteria-Derived Metabolites. Transl. Stroke Res. 2023, 14, 811–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suganya K, Son T, Kim KW, Koo BS. Impact of gut microbiota: How it could play roles beyond the digestive system on development of cardiovascular and renal diseases. Microb. Pathog, 2021; 152, 104583. [CrossRef]

- Kasahara K, Rey FE. The emerging role of gut microbial metabolism on cardiovascular disease. Curr. Opin. Microbiol, 2019; 50, 64–70. [CrossRef]

- Naik SS, Ramphall S, Rijal S, et al. Association of Gut Microbial Dysbiosis and Hypertension: A Systematic Review. Cureus, Published online. 4 October 2022. [CrossRef]

- Tousoulis D, Guzik T, Padro T, et al. Mechanisms, therapeutic implications, and methodological challenges of gut microbiota and cardiovascular diseases: a position paper by the ESC Working Group on Coronary Pathophysiology and Microcirculation. Cardiovasc. Res. 2022, 118, 3171–3182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia Q, Xie Y, Lu C, et al. Endocrine organs of cardiovascular diseases: Gut microbiota. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2019, 23, 2314–2323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang WHW, Hazen SL. The contributory role of gut microbiota in cardiovascular disease. J. Clin. Invest. 2014, 124, 4204–4211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuteja S, Ferguson JF. Gut Microbiome and Response to Cardiovascular Drugs. Circ. Genomic Precis. Med. 2019, 12, e002314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKay M, Yang BH, Dursun SM, Baker GB. The Gut-Brain Axis and the Microbiome in Anxiety Disorders, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Curr. Neuropharmacol, 2023; 21.

- Chen X, Zhang H, Ren S, et al. Gut microbiota and microbiota-derived metabolites in cardiovascular diseases. Chin Med J (Engl). 2023, 136, 2269–2284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen Y, Sun Z, Xie S, et al. Intestinal Flora Derived Metabolites Affect the Occurrence and Development of Cardiovascular Disease. J. Multidiscip. Healthc, 2022; 15, 2591–2603. [CrossRef]

- Khan I, Khan I, Jianye Z, et al. Exploring blood microbial communities and their influence on human cardiovascular disease. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2022, 36, e24354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly TN, Bazzano LA, Ajami NJ, et al. Gut Microbiome Associates With Lifetime Cardiovascular Disease Risk Profile Among Bogalusa Heart Study Participants. Circ. Res. 2016, 119, 956–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen L, Ishigami T, Doi H, Arakawa K, Tamura K. The Types and Proportions of Commensal Microbiota Have a Predictive Value in Coronary Heart Disease. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 3120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence G, Midtervoll I, Samuelsen SO, Kristoffersen AK, Enersen M, Håheim LL. The blood microbiome and its association to cardiovascular disease mortality: case-cohort study. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2022, 22, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmu J, Börschel CS, Ortega-Alonso A, et al. Gut microbiome and atrial fibrillation—results from a large population-based study. eBioMedicine, 2023; 91, 104583. [CrossRef]

- Wan C, Zhu C, Jin G, Zhu M, Hua J, He Y. Analysis of Gut Microbiota in Patients with Coronary Artery Disease and Hypertension. Wan JY, ed. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat Med, 2021; 2021, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Liao L, Huang J, Zheng J, Ma X, Huang L, Xu W. Gut microbiota in Chinese and Japanese patients with cardiovascular diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Saudi Med. 2023, 43, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pevsner-Fischer M, Blacher E, Tatirovsky E, Ben-Dov IZ, Elinav E. The gut microbiome and hypertension. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 2017, 26, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Sata Y, Marques FZ, Kaye DM. The Emerging Role of Gut Dysbiosis in Cardio-metabolic Risk Factors for Heart Failure. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2020, 22, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dao MC, Everard A, Aron-Wisnewsky J, et al. Akkermansia muciniphila and improved metabolic health during a dietary intervention in obesity: relationship with gut microbiome richness and ecology. Gut. 2016, 65, 426–436. [CrossRef]

- Marques FZ, Mackay CR, Kaye DM. Beyond gut feelings: how the gut microbiota regulates blood pressure. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2018, 15, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anselmi G, Gagliardi L, Egidi G, et al. Gut Microbiota and Cardiovascular Diseases: A Critical Review. Cardiol. Rev. 2021, 29, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moszak M, Szulińska M, Bogdański P. You Are What You Eat—The Relationship between Diet, Microbiota, and Metabolic Disorders—A Review. Nutrients. 2020, 12, 1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar T, Dutta RR, Velagala VR, Ghosh B, Mudey A. Analyzing the Complicated Connection Between Intestinal Microbiota and Cardiovascular Diseases. Cureus, Published online. 19 August 2022. [CrossRef]

- Tuohy KM, Fava F, Viola R. ‘The way to a man’s heart is through his gut microbiota’—dietary pro- and prebiotics for the management of cardiovascular risk. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2014, 73, 172–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesci A, Carnuccio C, Ruggieri V, et al. Gut Microbiota and Cardiovascular Disease: Evidence on the Metabolic and Inflammatory Background of a Complex Relationship. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang WHW, Hazen SL. The Gut Microbiome and Its Role in Cardiovascular Diseases. Circulation. 2017, 135, 1008–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özsoy S, Sultanoglu N, Sanlidag T. The role of mediterranean diet and gut microbiota in type- diabetes mellitus associated with obesity (diabesity). J. Prev. Med. Hyg, 2022; 63, 2S3:E87. [CrossRef]

- Merra G, Noce A, Marrone G, et al. Influence of Mediterranean Diet on Human Gut Microbiota. Nutrients. 2020, 13, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borton MA, Shaffer M, Hoyt DW, et al. Targeted curation of the gut microbial gene content modulating human cardiovascular disease. Messaoudi L, ed. mBio. 2023, 14, e01511-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poli, A. What connection is there between intestinal microbiota and heart disease? Eur. Heart J. Suppl. 2020, 22 (Suppl. L), L117–L120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Rubaye H, Perfetti G, Kaski JC. The Role of Microbiota in Cardiovascular Risk: Focus on Trimethylamine Oxide. Curr. Probl. Cardiol. 2019, 44, 182–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemmati M, Kashanipoor S, Mazaheri P, et al. Importance of gut microbiota metabolites in the development of cardiovascular diseases (CVD). Life Sci. 2023; 329, 121947. [CrossRef]

- Kanitsoraphan C, Rattanawong P, Charoensri S, Senthong V. Trimethylamine N-Oxide and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease and Mortality. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2018, 7, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts AB, Gu X, Buffa JA, et al. Development of a gut microbe–targeted nonlethal therapeutic to inhibit thrombosis potential. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 1407–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palombaro M, Raoul P, Cintoni M, et al. Impact of Diet on Gut Microbiota Composition and Microbiota-Associated Functions in Heart Failure: A Systematic Review of In Vivo Animal Studies. Metabolites. 2022, 12, 1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagatomo Y, Tang WHW. Intersections Between Microbiome and Heart Failure: Revisiting the Gut Hypothesis. J. Card. Fail. 2015, 21, 973–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koay YC, Chen YC, Wali JA, et al. Plasma levels of trimethylamine-N-oxide can be increased with ‘healthy’ and ‘unhealthy’ diets and do not correlate with the extent of atherosclerosis but with plaque instability. Cardiovasc. Res. 2021, 117, 435–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringel C, Dittrich J, Gaudl A, et al. Association of plasma trimethylamine N-oxide levels with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and factors of the metabolic syndrome. Atherosclerosis, 2021; 335, 62–67. [CrossRef]

- Lee Y, Nemet I, Wang Z, et al. Longitudinal Plasma Measures of Trimethylamine N-Oxide and Risk of Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease Events in Community-Based Older Adults. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2021, 10, e020646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gencer B, Li XS, Gurmu Y, et al. Gut Microbiota-Dependent Trimethylamine N-oxide and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Patients With Prior Myocardial Infarction: A Nested Case Control Study From the PEGASUS-TIMI 54 Trial. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2020, 9, e015331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou X, Jin M, Liu L, Yu Z, Lu X, Zhang H. Trimethylamine N-oxide and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with chronic heart failure after myocardial infarction. ESC Heart Fail. 2020, 7, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li W, Huang A, Zhu H, et al. Gut microbiota-derived trimethylamine N. -oxide is associated with poor prognosis in patients with heart failure. Med. J. Aust. 2020, 213, 374–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen G, He L, Dou X, Liu T. Association of Trimethylamine-N-Oxide Levels with Risk of Cardiovascular Disease and Mortality among Elderly Subjects: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cardiorenal Med. 2022, 12, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren H, Zhu B, An Y, Xie F, Wang Y, Tan Y. Immune communication between the intestinal microbiota and the cardiovascular system. Immunol. Lett, 2023; 254, 13–20. [CrossRef]

- Bu J, Wang Z. Cross-Talk between Gut Microbiota and Heart via the Routes of Metabolite and Immunity. Gastroenterol. Res. Pract, 2018; 2018, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Trøseid M, Andersen GØ, Broch K, Hov JR. The gut microbiome in coronary artery disease and heart failure: Current knowledge and future directions. EBioMedicine, 2020; 52, 102649. [CrossRef]

- Dubinski P, Czarzasta K, Cudnoch-Jedrzejewska A. The Influence of Gut Microbiota on the Cardiovascular System Under Conditions of Obesity and Chronic Stress. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2021, 23, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastori D, Carnevale R, Nocella C, et al. Gut-Derived Serum Lipopolysaccharide is Associated With Enhanced Risk of Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events in Atrial Fibrillation: Effect of Adherence to Mediterranean Diet. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2017, 6, e005784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Ruiz P, Amezcua-Guerra LM, López-Vidal Y, et al. Comparative characterization of inflammatory profile and oral microbiome according to an inflammation-based risk score in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol, 2023; 13, 1095380. [CrossRef]

- Zabell A, Tang WHW. Targeting the Microbiome in Heart Failure. Curr. Treat. Options Cardiovasc. Med. 2017, 19, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitai T, Tang WHW. Gut microbiota in cardiovascular disease and heart failure. Clin. Sci. 2018, 132, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamic P, Chaikijurajai T, Tang WHW. Gut microbiome—A potential mediator of pathogenesis in heart failure and its comorbidities: State-of-the-art review. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol, 2021; 152, 105–117. [CrossRef]

- Anderson KM, Ferranti EP, Alagha EC, Mykityshyn E, French CE, Reilly CM. The heart and gut relationship: a systematic review of the evaluation of the microbiome and trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO) in heart failure. Heart Fail. Rev. 2022, 27, 2223–2249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo A, Macerola N, Favuzzi AM, Nicolazzi MA, Gasbarrini A, Montalto M. The Gut in Heart Failure: Current Knowledge and Novel Frontiers. Med. Princ. Pract. 2022, 31, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimble R, Gouinguenet P, Ashor A, et al. Effects of a mediterranean diet on the gut microbiota and microbial metabolites: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials and observational studies. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 63, 8698–8719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rejeski JJ, Wilson FM, Nagpal R, Yadav H, Weinberg RB. The Impact of a Mediterranean Diet on the Gut Microbiome in Healthy Human Subjects: A Pilot Study. Digestion. 2022, 103, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagliai G, Russo E, Niccolai E, et al. Influence of a 3-month low-calorie Mediterranean diet compared to the vegetarian diet on human gut microbiota and SCFA: the CARDIVEG Study. Eur. J. Nutr. 2020, 59, 2011–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitsou EK, Kakali A, Antonopoulou S, et al. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet is associated with the gut microbiota pattern and gastrointestinal characteristics in an adult population. Br. J. Nutr. 2017, 117, 1645–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barber TM, Kabisch S, Pfeiffer AFH, Weickert MO. The Effects of the Mediterranean Diet on Health and Gut Microbiota. Nutrients. 2023, 15, 2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Mantrana I, Selma-Royo M, Alcantara C, Collado MC. Shifts on Gut Microbiota Associated to Mediterranean Diet Adherence and Specific Dietary Intakes on General Adult Population. Front. Microbiol, 2018; 9, 890. [CrossRef]

- Tagliamonte S, Laiola M, Ferracane R, et al. Mediterranean diet consumption affects the endocannabinoid system in overweight and obese subjects: possible links with gut microbiome, insulin resistance and inflammation. Eur. J. Nutr. 2021, 60, 3703–3716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muralidharan J, Moreno-Indias I, Bulló M, et al. Effect on gut microbiota of a 1-y lifestyle intervention with Mediterranean diet compared with energy-reduced Mediterranean diet and physical activity promotion: PREDIMED-Plus Study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 114, 1148–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pisanu S, Palmas V, Madau V, et al. Impact of a Moderately Hypocaloric Mediterranean Diet on the Gut Microbiota Composition of Italian Obese Patients. Nutrients. 2020, 12, 2707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ismael S, Silvestre MP, Vasques M, et al. A Pilot Study on the Metabolic Impact of Mediterranean Diet in Type 2 Diabetes: Is Gut Microbiota the Key? Nutrients. 2021, 13, 1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundogdu A, Nalbantoglu OU. The role of the Mediterranean diet in modulating the gut microbiome: A review of current evidence. Nutrition, 2023; 114, 112118. [CrossRef]

- Rosés C, Cuevas-Sierra A, Quintana S, et al. Gut Microbiota Bacterial Species Associated with Mediterranean Diet-Related Food Groups in a Northern Spanish Population. Nutrients. 2021, 13, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Filippis F, Pellegrini N, Vannini L, et al. High-level adherence to a Mediterranean diet beneficially impacts the gut microbiota and associated metabolome. Gut. 2016, 65, 1812–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark JS, Simpson BS, Murphy KJ. The role of a Mediterranean diet and physical activity in decreasing age-related inflammation through modulation of the gut microbiota composition. Br. J. Nutr. 2022, 128, 1299–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muralitharan RR, Jama HA, Xie L, Peh A, Snelson M, Marques FZ. Microbial Peer Pressure: The Role of the Gut Microbiota in Hypertension and Its Complications. Hypertension. 2020, 76, 1674–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-López M, Martínez-González M, Basterra-Gortari F, Barrio-López M, Gea A, Beunza J. Adherence to the Mediterranean dietary pattern and heart rate in the SUN project. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2014, 21, 521–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yntema T, Koonen DPY, Kuipers F. Emerging Roles of Gut Microbial Modulation of Bile Acid Composition in the Etiology of Cardiovascular Diseases. Nutrients. 2023, 15, 1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey MA, Holscher HD. Microbiome-Mediated Effects of the Mediterranean Diet on Inflammation. Adv. Nutr. 2018, 9, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Disease/Condition | Main Microbial Agents |

|---|---|

| Cardiovascular risk factors | Prevotella 2, Prevotella 7, Tyzzerella and Tyzzerella 4 genera, Bacteroides uniformis and B. vulgatus (low prevalence of Alloprevotella Prevotella copri. and Catenibacterium) |

| Arterial hypertension | Catabacter, Robinsoleilla, Serratia, Enterobacteriaceae, Ruminococcus torques, Parasutterella, Escherichia, Shigella, and Klebsiella (decreased abundance of Sporobacter, Roseburia hominis, Romboutsia spp., and Roseburia) |

| Atrial fibrillation | Enorma and Bifidobacterium genera |

| Diabetes mellitus | order Rhizobiales, family Desulfovibrionaceae, genus Romboutsia. |

| Coronary heart disease | Proteobacteria and Actinobacteria phyla, Bacteroides, Prevotella, Firmicutes, Veillonella, Clostridium, Lactobacillaceae (Lactobacillus plantarum) and Streptococcus (decreased prevalence of Caulobacterales order and Caulobacteraceae family, aminococcaceae and Odoribacteraceae) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | Firmicutes, Proteobacteria and Actinobacteria phyla |

| Heart failure | Ruminococcus gnavus, Escherichia Shigella, Streptococcus sp (sanguinus and parasanguinis), Veillonella sp, and Actinobacteria (relative depletion of Eubacterium, Prevotella, Faecalibacterium, SMB53, aminococcaceae, Odoribacteraceae and Megamonas) |

| Cardiovascular mortality | genera Kocuria and Enhydrobacter (genera Paracoccus was inversely related) |

| Increase | Decrease |

|---|---|

|

Akkermansia muciniphila, Anaerostipes hadrus, Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron, Bifidobacteria animalis, Candida albicans, Catenibacterium, Christensenellaceae, Clostridium (cluster XIVa, leptum) Enterorhabdus, Eubacterium rectale, Faecalibacterium (Lactococcus, prausnitzii) Lachnoclostridium, Lachnospiraceae, Oscillospira (Flavonifractor), Parabacteroides, Phascolarctobacterium, Prevotellaceae, Prevotellae, Proteobacteria, Roseburia faecis, Ruminococcaceae bromii and plautii, Sphingobacteriaceae |

Actinomyces lignae, Butyricicoccus, Catenibacterium, Clostridium ramosum, Collinsella aerofaciens, Coprococcus Anaerostipes and comes, Dorea formicigenerans, Escherichia coli, Eubacterium hallii, Firmicutes, Flavonifractor plautii, Haemophilus, Lachnospiraceae Megamonas, Ruminiclostridium, Ruminococcus gnavus and torques Veillonella dispar |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).