1. Introduction

The post-pandemic landscape has drastically reshaped the world of work, not only by introducing a new paradigm marked by heightened stress and anxiety among workers, but also by accelerating the adoption of work from home (WFH). The 2023 Gallup workplace survey revealed a concerning trend: 42% of workers worldwide are grappling with daily work-related stress, with the numbers climbing to 52% in the US and Canada (Gallup, 2023). Similarly, in the UK, a 14% increase in work-related stress, anxiety, and depression has been reported since 2020 by the Health and Safety Executive (HSE, 2023). Deloitte’s 2023 global survey of Gen Z and Millennial workers likewise reported that nearly half of Gen Zers and 39% of Millennials feel almost constantly anxious and stressed (Deloitte, 2023). The World Health Organization estimates that this workplace stress and anxiety costs the global economy US$1 trillion per year in lost productivity (World Health Organization, 2022). While these statistics provide insights into the prevalence of workplace anxiety (WA), it is important to consider the rising prevalence of WFH practices, which have become a significant feature of the post-pandemic work environment.

The varied experiences of employees reflect the complex nature of WFH. One respondent to the Gallup (2023) poll shared a positive view, stating, “I have more time to spend with my family, with my wife, with my dogs, so I spend less time in traffic and more quality time,” thereby highlighting the work-life balance benefits. In contrast, another employee pointed out the challenges of blurring work-life boundaries: “I guess having my workplace at home has made it more challenging to separate myself and step away from work.” This reflects a common struggle in separating professional and personal spaces. Furthermore, a third perspective underscores the social aspect: “At home, I feel like my job is just work. Like there’s not the, you know, the fun stuff. The camaraderie, right? The relationship building is a little bit harder.” This sentiment highlights the missing elements of workplace interactions and team bonding in the WFH environment. These quotes collectively paint a picture of the multifaceted implications of WFH on employees’ work experiences and overall well-being. To improve the employee experience and sustain productivity in the WFH environment, organizations equip their employees with digital technologies and infrastructure. This may include Virtual Private Networks, Zoom, and Microsoft Teams, as well as essential hardware such as webcams, monitors, reliable Wi-Fi connections, and ergonomic seating options (Rangarajan et al., 2021).

In the Global Survey of Working Arrangements

1 (GSWA), Aksoy et al. (2022) noted a significant and enduring transition toward WFH practices because of the COVID-19 pandemic, albeit with a notably higher prevalence in English-speaking countries. For instance, in nations like Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the UK, and the US, full-time employees spent approximately 28% of their workdays working from home. In contrast, Asian countries reported an average of 14% of workdays being spent at home, European countries at 16%, and a combination of four Latin American countries (Argentina, Chile, Brazil, Mexico) plus South Africa averaging 18%. Overall, across the 34 countries surveyed, 67% of full-time employees were found to work entirely on business premises five days a week; 26% engaged in hybrid work arrangements; and 8% worked exclusively from home. A notable observation from the GSWA was regarding the disparity between employee preferences and employer plans regarding WFH days. Globally, employees expressed a desire to WFH for an average of 2.0 days per week, however employers were inclined to offer only approximately 1.1 WFH days per week. This mismatch between employee desires and employer provisions for WFH was consistently observed across all 34 countries, which prompted two questions: a) What is the nature of the relationship between a WFH environment and WA; and b) Does gender influence the relationship between a WFH environment and WA?

While much of the existing literature on WA tends to emphasize its detrimental effects, recent research suggests a more nuanced view, indicating that WA can have both positive and negative outcomes. On the one hand, studies have linked WA to adverse impacts such as diminished job performance (McCarthy et al., 2016), unethical behaviors (Hillebrandt & Barclay, 2022), and increased turnover intentions (Haider et al., 2020), yet on the other, there is evidence to suggest that WA can also contribute positively by enhancing personal initiative and citizenship behaviors (Cheng et al., 2023), as well as fostering problem prevention behaviors (Barclay & Kiefer, 2019). This dual perspective highlights the complex and multifaceted nature of WA. Adding to this complexity, Mao et al. (2021) contributed an interesting WA perspective with their finding that a moderate level of anxiety within a team could potentially stimulate creative processes, while too little or too much anxiety might hinder these outcomes.

These findings highlight that WA has both adaptive and maladaptive effects, aligning closely with Lazarus's (2006) assertion that: “From an evolutionary standpoint, emotions facilitate the struggles of warm-blooded mammals to survive and flourish. It must be acknowledged, however, that emotions can also impair adaptation” (p. 10). Lazarus added that anxiety is an emotional mechanism that triggers defensive actions in the face of perceived, non-specific threats. By integrating this definition of anxiety with the conservation of resources theory (COR) (Hobfoll, 1989), which identifies stress as a reaction to the real or perceived threat of resource loss, we get a different perspective on WA. COR theory suggests that WA may not just be a psychological state, but also a manifestation of resource depletion. This perspective implies that WA could be both a result of, and a response to, the dwindling of psychological capital (PsyCap), a personal resource necessary for managing workplace demands and challenges (Avey et al., 2011). This prompts two questions: a) What is the nature of the relationship between WA and PsyCap; and b) Do job resources such as characteristics of digital technologies that support WFH influence the WA-PsyCap relationship?

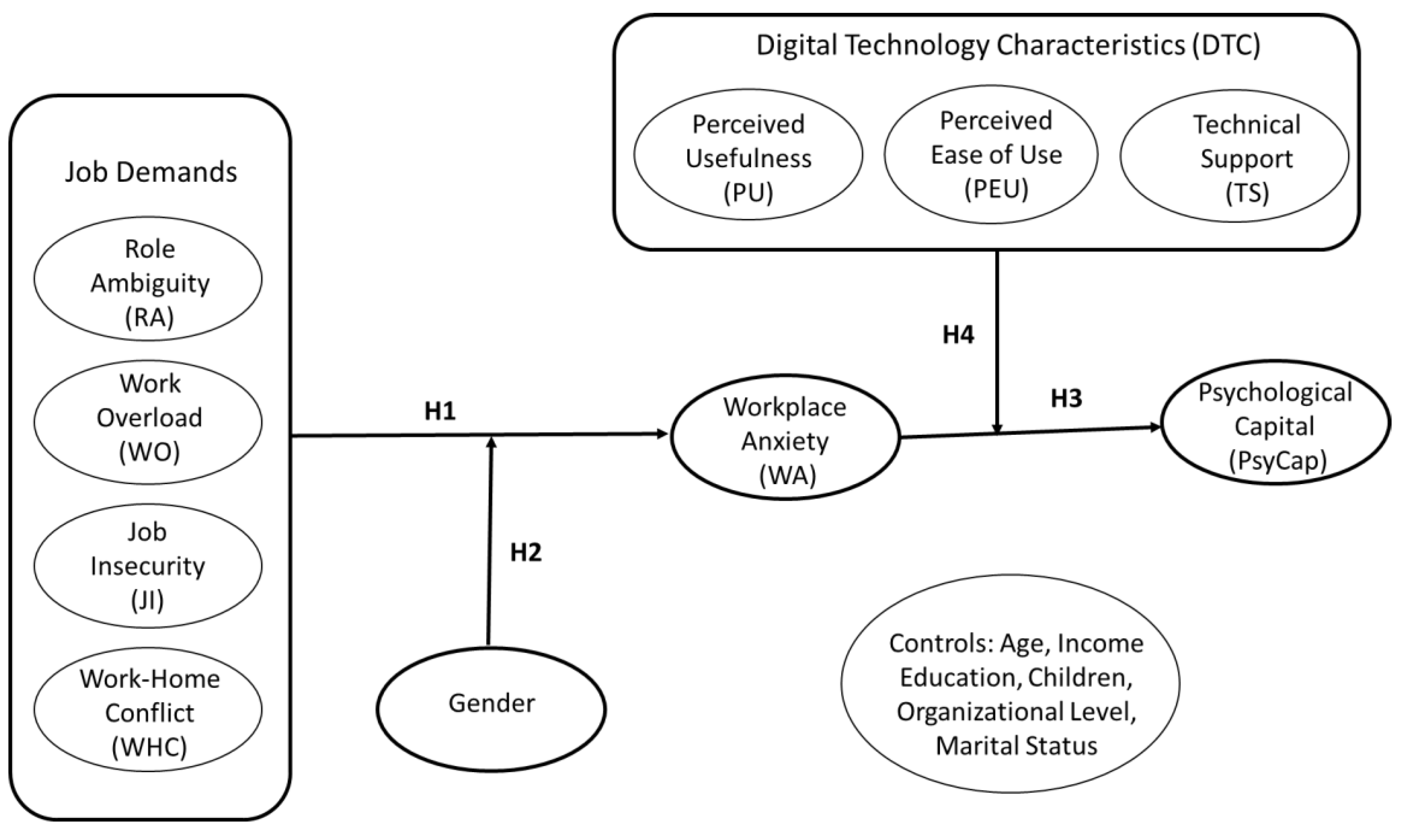

In conclusion, this study aimed to comprehensively address the four research questions outlined above. Our primary objective was to determine the influence of a WFH environment on WA and, in turn, how WA affects PsyCap. This study carefully differentiated between the external factors, namely the WFH environment, and the resultant internal emotional responses, specifically WA, as we sought to better understand the intricate relationships linking the WFH environment, emotional reactions, and the PsyCap of employees. Additionally, our research extended to analyzing two moderating factors: the influence of gender on the relationship between WFH environment and WA, and the role of job resources (i.e., digital technology characteristics (DTC)) on the association between WA and PsyCap.

We aimed to make four key theoretical contributions. First, by applying the theory of workplace anxiety (TWA) (Cheng & McCarthy, 2018), we illuminate how a WFH environment uniquely impacts WA, addressing critical gaps identified by researchers such as Rangarajan et al. (2021). This investigation was enriched by examining gender as a key moderating factor, providing deeper insights into the conditions under which a WFH environment influences WA, and answering the call by Cheng and McCarthy (2018) for research on moderators in the TWA. We argue that given the growth in WFH noted earlier, it is crucial to understand how a WFH environment affects WA.

Second, in response to scholars (e.g., Barclay & Kiefer, 2019; Cheng & McCarthy, 2018; McCarthy et al., 2016), and given the pervasive and damaging effects of WA noted earlier, we delved into the downstream effects of WA, particularly its impact on PsyCap, and responded to the call by researchers (e.g., Avey et al., 2011; Luthans et al., 2017) for more research on the predictors of PsyCap. Our argument posits WA as a state of resource depletion, a concept that aligns with Hobfoll’s (1989) perspective on humans’ evolutionary need to acquire and conserve resources. Furthermore, by identifying and analyzing the role of DTC as moderators in the WA-PsyCap relationship, we provide a more nuanced understanding of this relationship.

Third, our study heeded the call for empirical testing of the TWA by Cheng and McCarthy (2018). By employing a diverse South African sample, we extended the examination of TWA beyond the typical focus on Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic (WEIRD) populations (Henrich et al., 2010). This approach not only broadened the applicability of TWA, but also marked a critical step in its empirical validation. Finally, and as a noteworthy aspect, this study sought to enhance existing knowledge by focusing on the examination of employees’ WA in the context of working from home.

Collectively, these contributions not only responded to existing calls in literature, but also paved the way for future research, offering novel insights and perspectives on the intersection of a WFH environment, DTC, PsyCap and WA in the post-pandemic work environment. The structure of this article is as follows. First, we present a brief literature review and develop hypotheses, leading to the study’s conceptual model. Next, the conceptual model is empirically tested with a dataset (n = 162), using both linear and logistic regression. Finally, we discuss the main findings, limitations, and implications of the study, before giving recommendations for future research.

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Conceptual Framework

Scholars (e.g., Lazarus, 2006; Smith & Ellsworth, 1985) have stated that emotions can be distinguished by specific dimensions, allowing for the differentiation of one emotion from another. These dimensions include valence, arousal, and cognitive appraisals. Valence pertains to the degree of pleasantness or unpleasantness associated with an emotion; arousal relates to the intensity or energy level of the emotional experience; and cognitive appraisals are tendencies to evaluate and interpret events and the environment, for example, the level of control and certainty. For instance, anxiety is typically characterized as a negative valence, high arousal emotion that involves cognitive appraisals of uncertainty and low control. This characterization aligns well with Spielberger’s (1985) widely cited definition of anxiety as “feelings of tension, apprehension, and dread, and cognitions of impending danger” (p. 173). This definition highlights the multifaceted nature of anxiety as it makes a crucial distinction between situational (state) and dispositional (trait).

Whereas state anxiety is defined as a temporary response to challenging situations, embodying an immediate reaction to stressors, trait anxiety is defined as a more enduring characteristic – a consistent individual difference that predisposes a person to experience anxiety across various circumstances, essentially constituting a personality trait (Spielberger, 1972; 1985). In addition, Spielberger (1972) distinguished anxiety from stress by stating that stress should “be used exclusively to denote environmental conditions or circumstances that are characterized by some degree of objective physical or psychological danger” (p. 488), while anxiety should “be used to refer to the emotional reaction or pattern of response [to perceived threat]” (p. 488). Anxiety and stress are conceptually distinct from stressors, which Podsakoff et al. (2007) defined as challenging circumstances that can potentially lead to adverse effects on emotions, thoughts, behavior, physiological health, and overall well-being.

Cheng and McCarthy (2018) formulated the TWA by expanding upon the foundational research on anxiety, broader psychological literature (e.g., clinical, stress, sport, music, and educational psychology), and the dominant work psychological models, like the job demands-resources (JD-R) (Demerouti et al., 2001), which elucidate the influence of job demands, job resources, and personal resources on employees’ performance and functioning in the workplace. Within the TWA framework, WA is conceptualized as “feelings of nervousness, uneasiness, and tension about job-related performance” (p. 537). Cheng and McCarthy (2018) posited that WA is influenced by both individual predispositions and environmental situations, and thus manifests as both dispositional WA and situational WA. Whereas dispositional WA is conceptualized as “individual differences in feelings of nervousness, uneasiness, and tension about job performance” (p. 539), situational WA is conceptualized as a “transient emotional state reflecting nervousness, uneasiness, and tension about specific job performance episodes” (p. 539).

The TWA incorporates a dual-perspective approach to understanding the origins and manifestations of anxiety in the workplace. The dispositional aspect of this theory, grounded in trait-based perspectives, postulates that individual differences, such as demographics, core self-evaluations, and physical health, contribute to dispositional WA. This form of anxiety is considered a more stable, enduring trait that varies among individuals, suggesting that some employees may have a higher propensity for anxiety due to inherent personal characteristics. Conversely, the situational aspect of TWA emphasizes the state-based, transient nature of WA. It is posited that situational factors, including the emotional demands of labor, task requirements, and broader organizational demands, together with job-specific characteristics—such as job type, job demands, and the degree of autonomy—influence the immediate experience of situational WA. This suggests that situational WA can fluctuate and is sensitive to the dynamic conditions of the work environment such as WFH.

The TWA further posits a bidirectional relationship between dispositional WA and situational WA, suggesting that an individual's inherent anxiety traits (dispositional WA) can influence their reactions to specific workplace scenarios (situational WA), and vice versa. This reciprocal dynamic indicates that not only can a person’s general tendency towards anxiety shape their response to workplace stressors, but the exposure to certain job-related demands and conditions can, over time, affect their baseline anxiety levels. This bidirectional model acknowledges the complexity of WA, where personal characteristics and situational factors are in continuous interaction, each shaping the experience of the other. Finally, according to the TWA, both dispositional and situational WA “can exert negative and positive effects on job performance” (Cheng & McCarthy, 2018, p. 538). The current study is focused on situational WA because it sought to explore employees’ WA triggered by WFH environment.

2.2. Work from Home Job Demands and Workplace Anxiety

Grounded in comprehensive psychological literature on emotion, affect, and stress, the TWA theorizes that “situational characteristics and job characteristics are the core antecedents of situational workplace anxiety” (Cheng & McCarthy, 2018, p. 546). Our study investigated the association between situational WA and four important aspects of a WFH environment: role ambiguity (RA), work overload (WO), job insecurity (JI), and work-home conflict (WHC).

2 These were chosen because they are recognized as the most extensively examined job demands or stressors in the literature (Podsakoff et al., 2007), and are defined within the framework of the JD-R model as “physical, psychological, social, or organizational aspects of the job that require sustained physical and/or psychological (cognitive or emotional) effort or skills and are therefore associated with certain physiological and/or psychological costs” (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007, p. 312). This can manifest in various forms of strain such as “burnout, depression, emotional exhaustion, fatigue, frustration, mental, psychological, and physical symptoms, and tension” (Podsakoff et al., 2007, p. 442). Thus, in the present study, WFH job demands encompass role ambiguity, which is uncertainty about required actions for role fulfillment; work overload, where time and resources are insufficient for meeting role obligations; job insecurity, the perceived probability of job loss based on one’s interpretation of the work environment; and work-home conflict, the perceived clash between work and family demands.

Podsakoff et al.’s (2007) meta-analytical study, which examined 183 independent samples, found that job demands significantly exacerbated strain. As the TWA is relatively nascent with limited empirical testing, only one extant study by Wang et al. (2021) has corroborated the predicted strong positive associated between job demands, specifically informational overload, and WA. However, the extant job demands literature findings are that work overload (Alnazly et al., 2023), role ambiguity (Pretorius & Padmanabhanunni, 2022), work-home conflict (Sanz-Vergel et al., 2011), and job insecurity (Cheng & Chang, 2008) significantly positively predict anxiety.

3 Consistent with the TWA and the preceding discussion, we proposed the following hypothesis:

H1. WFH job demands (i.e., WO, RA, JI, WHC) will each significantly predict WA.

2.3. Gender as a Moderator

While the TWA does not explicitly suggest moderation between situational and job characteristics (i.e., job demands) and WA, existing literature on job demands has identified potential moderators like gender, dependents, seniority, tenure, personality, and leader–member exchange. In this context, we hypothesize that gender moderates the relationship between WFH job demands and WA. This is supported by various theories explaining gender differences in areas such as cognitive performance, personality, social behaviors, and psychological well-being (Hyde, 2014). Evolutionary theories (e.g., Buss & Schmitt, 1993) suggest that psychological gender differences are evolutionary adaptations with varying behavioral benefits for males and females. Cognitive social learning theory (Bussey & Bandura, 1999) views these differences as outcomes of distinct social reinforcements and cognitive processes like attention and self-efficacy. Social role theory (Eagly & Wood, 1999) attributes contemporary psychological gender differences to historical divisions of labor, leading to the development of gender-specific psychological traits.

These theoretical perspectives provide a foundation for understanding the empirical findings of gender-related research. For example, regarding psychological well-being, Hyde (2014) noted that adult women are twice as likely to experience depression as men, which is influenced by affective, biological, and cognitive factors. While research directly addressing gender’s moderating role between WFH job demands and WA is scarce, Harlos et al. (2023) provided relevant insights. Their study, while not focusing on WA, examined gender as a moderator between job demands (i.e., role ambiguity, role conflict, role overload) and psychological strain (i.e., workplace bullying). They found a significant interaction between role conflict and gender, such that the effect of role conflict was stronger for women than men. Based on these discussions, we put forward the following hypothesis:

H2.Gender moderates the association between WFH job demands (i.e., WO, RA, JI, WHC) and WA such that the effects of job demands will be stronger for women than men.

2.4. Workplace Anxiety and Psychological Capital

In the current study, we explored PsyCap as a personal resource that can be depleted by high levels of WA. Hobfoll (1989) defined personal resources as flexible capacities that reflect an individual’s perceived capability to impact and contribute positively to their work environment. PsyCap “plays a decisive role in employees’ functioning at work” (Xanthopoulou et al., 2007, p. 124), and was defined by Luthans and Youssef-Morgan (2017, p. 2) as:

“an individual’s positive psychological state of development characterized by: (1) having confidence (self-efficacy) to take on and put in the necessary effort to succeed at challenging tasks; (2) making a positive attribution (optimism) about succeeding now and in the future; (3) persevering toward goals, and, if needed, redirecting paths to goals (hope) to achieve success; and (4) when faced with problems and adversity, sustaining and bouncing back and even beyond (resilience) to attain success.”

COR theory posits that resource loss is a major component of stressful encounters, such as those experienced with job demands. Following the TWA, we earlier hypothesized that WFH job demands positively influence WA, and from COR theory, we earlier argued that WA represents a state of resource loss. This implies that heightened WA could lead to resource depletion, diminishing PsyCap levels. This line of reasoning was empirically supported by Zeidner and colleagues (Zeidner et al., 2011; Zeidner & Ben-Zur, 2014), whose experimental studies demonstrated that stressful encounters cause significantly high levels of negative affect, like anxiety, and reduce psychological resources. Additionally, Cao et al. (2022), in a cross-sectional study using instrumental variables to address endogeneity, observed a robust negative relationship between negative affect (e.g., anxiety) and PsyCap. Similarly, Yu and Li (2020) reported a strong negative correlation between anxiety and PsyCap. In alignment with COR theory and the discussions above, we therefore propose the following hypothesis:

H3.WA will be negatively associated with PsyCap.

The resource investment principle of COR theory states that to avert resource loss, recover from losses, and acquire new resources, individuals need to invest their existing resources. This means that when facing adversity, individuals will deploy their remaining resources to overcome ongoing challenges, thereby limiting resource loss and reducing negative outcomes. Within an organizational setting, job resources play a critical role in this regard. Job resources encompass the physical, psychological, social, and/or organizational elements of a job that serve one or more of the following functions: aid in accomplishing work objectives, alleviate job demands and their related physical and mental burdens, and foster individual growth, learning, and development (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007). In the context of employees working from home and encountering job demands, the digital technologies provided by the employer represent a major job resource. According to the JD-R model, job resources contribute to a motivational process by aiding individuals in reinforcing their core self-concept and successfully achieving their work roles and goals. Inversely, a lack of job resources, such as limited control, can impede employees’ ability to fulfill their roles, thereby resulting in heightened role stress and diminished levels of work engagement.

Job resources have been defined broadly with the JD-R model. For example, Schaufeli’s (2017) energy compass instrument categorizes job resources into four groups: social, work, organizational, and development resources. Social resources encompass support from coworkers and supervisors, team dynamics, role clarity, expectation fulfillment, and recognition. Work resources cover aspects like job control, alignment with personal skills, task variety, participation in decision-making, skill utilization, and the availability of necessary tools. Organizational resources include effective communication, alignment with organizational goals, leadership trust, fairness in organizational justice and pay, and value congruence. Finally, developmental resources focus on performance feedback, opportunities for learning and career development, and prospects for career advancement.

The JD-R model has been widely utilized in numerous studies examining employee functioning in the workplace, including research by Bakker and Demerouti (2007) and Xanthopoulou et al. (2007). Findings consistently show that greater job resources are strongly linked to positive outcomes, such as reduced strain, increased engagement, and enhanced well-being. The JD-R model suggests a buffering interaction process, where high job resources (e.g., DTC) mitigate the adverse effects of high job demands (e.g., WA) on job strain (e.g., diminished PsyCap). In demanding work environments, employees with abundant resources have more tools at their disposal, making them better equipped to handle these demands. Consequently, they are likely to experience lower levels of negative outcomes. Building on the buffering interaction process, we propose that high DTC will lessen the impact of WA on PsyCap by bolstering employees’ confidence in managing these demands. Rangarajan et al. (2022) identified three critical DTC – perceived usefulness (PU), perceived ease of use (PEU), and technical support (TS) – and demonstrated their moderating effect. Specifically, their study revealed significant interactions between WA and PU, as well as WA and TS, illustrating the moderating function of these DT characteristics on the association between WA and employee normative and affective commitment to WFH. In alignment with the JD-R model, COR theory and the discussions above, we propose the following hypothesis:

H4.DTC (i.e., PU, PEU, TS) will moderate the negative association between WA and PsyCap such that higher levels of PU, PEU, and TS will buffer the negative impact of WA on PsyCap.

Figure 1 represents the conceptual model developed for the study.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants and Procedure

Following university ethics approval, an online survey was created and pretested with 10 individuals to ensure that the questions were clear and appropriate. Subsequent minor revisions led to a final survey comprising an introduction; demographic details; WFH job demands; DTC; WA; and PsyCap. The survey, designed to take between 15 and 20 minutes, was specified as being for full-time employees who had transitioned to working entirely from home due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The survey was disseminated through personal contacts, social media platforms (WhatsApp, Facebook, and LinkedIn) and snowballing techniques from July 21 to September 5, 2022, yielding 162 complete responses with no missing data due to the compulsory nature of all the questions. The data were analyzed using SAS 9.4 software.

3.2. Measures

The survey instrument for this study was carefully adapted from established measures found in existing literature. For all variables except demographic ones, we employed 7-point Likert-type scales. These scales allowed respondents to express their level of agreement, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The psychometric properties of these scales have demonstrated robustness in previous studies. Moreover, in the current study, each scale displayed satisfactory internal consistency and reliability.

3.2.1. WFH Job Demands

Participants evaluated four specific job demands, each measured by distinct items from the scale developed by Rangarajan et al. (2021). For WO, a representative item was, “WFH creates many more requests, problems or complaints in my job than I would otherwise experience.” RA was assessed with an item like, “I am unsure whether I have to deal with my WFH problems or with my work activities.” JI was gauged through statements such as, “WFH will advance to an extent where my present job can be performed by a less skilled individual.” Lastly, WHC was measured by items including, “I do not get everything done at home because I find myself completing job-related work because of WFH.” The responses to these items were averaged to generate a single composite score for each job demand, with higher scores indicating greater job demands.

3.2.2. Workplace Anxiety

We used the 8-item scale developed by McCarthy et al. (2016). Two sample items were: “I often feel anxious that I will not be able to perform my job duties in the time allotted” and “I feel nervous and apprehensive about not being able to meet performance targets.” The responses to these items were averaged to generate a single composite score, with higher scores indicating greater WA.

3.2.3. Digital Technology Characteristics

Participants evaluated three specific DT characteristics, each measured by distinct items from the scale developed by Rangarajan et al. (2021). For PU, a representative item was, “Use of DT enhances my job effectiveness when I WFH,” while PEU was assessed with an item like, “I find our DT for WFH to be easy to use.” Lastly, TS was measured by items including, “The training provided for DT is complete and sufficient.” The responses to these items were averaged to generate a single composite score for each characteristic, with higher scores indicating greater satisfaction.

3.2.4. Psychological Capital

We modified four items from the scale created by Luthans and Youssef-Morgan (2017) to represent the four facets of PsyCap: hope, self-efficacy, resilience, and optimism. Two sample items were: “I believe that I can bounce back from any setbacks that have occurred” and “I expect good things to happen in the future.” The responses to these items were averaged to generate a single composite score, with higher scores indicating greater PsyCap.

The following demographic information was also gathered, and in line with the literature, was used as control variables: gender, age (18 to 34, 35 to 44, 45 to 54, 55 to 64); education (less than degree, degree, postgraduate); marital status (never married, married, divorced); dependent children (yes/no); organizational level (junior, middle, senior, executive); and annual income (less than R400K, R400K to R700K, R700K to R1,500K, more than R1,500K).

3.3. Statistical Analysis

The first dependent variable in this study, WA, was continuous and had an approximately normal distribution, with a mean = 3.22, median = 2.75, and standard deviation = 1.59. Both skewness (0.38) and kurtosis (-1.05) were within the acceptable range of -2 to +2, so we used hierarchical ordinary least squares regression to estimate the effects of WFH job demands, gender, and their interactions on WA. The second dependent variable, PC, with a mean = 6.08, median = 6.25, and standard deviation = 1.08, exhibited a considerable leftward skewness (-2.35) and a high kurtosis (7.39), indicating a significant deviation from normality. Upon closer inspection, the PC scores predominantly grouped into two clusters – low and high PC levels, with few responses in the intermediate range. This pattern justified the decision to create a dichotomous variable of PC – the high as the median or higher and low as below the median. This approach not only addressed the issues arising from the skewed and leptokurtic distribution, but also aligned with the natural bifurcation. By categorizing PC into low and high groups based on the median, we aimed to capture the distribution of PC levels more effectively, while also ensuring robustness in our statistical analysis given the non-normal nature of the data distribution. We used hierarchical logistic regression to estimate the effects of WA, DTC, and their interactions on PsyCap.

The use of hierarchical regression was aligned with the theoretical frameworks utilized in this study and allowed for sequential inclusion of variable blocks in our regression models, enabling us to determine the changes in the amount of variance explained for each step. All the interaction terms were created as product terms and were added as the last step in the regression analyses, all continuous independent variables were centered before analysis, and unstandardized coefficients were used to test the significance of each of the variables (Aiken & West, 1991). All variance inflation factors fell below three, confirming the absence of multicollinearity concerns in our model. To address potential common method bias due to self-reports, we conducted Harman's single-factor test which showed that common method bias was not a concern in our dataset.

4. Results

4.1. Explanatory Factor Analysis And descriptive Statistics

For the current study, we performed an exploratory factor analysis to ascertain the dimensionality of the newly developed indices. We set the threshold for factor loadings at 0.60, with no cross loadings, and applied both Kaiser’s eigenvalue criterion (≥ 1) and the scree plot test to determine factor retention. The internal consistency reliability and convergent validity of the study’s focal constructs were confirmed with an acceptable Cronbach's alpha, composite reliability, and average variance extracted metrics. The factor analysis outcomes for the included items are detailed in

Table 1.

Table 2 illustrates the demographic profile of the participants. Two-thirds (66.67%) of the respondents were female, and most of the respondents were highly educated. Over half (55.56%) possessed postgraduate qualifications, were junior in their roles (58.64%), had dependent children (80.25%), were married (54.94%) and earned annual income between R700,000 and R1,500,000 (56.17%). Almost half (48.77%) of the respondents were aged 35 to 44.

Table 3 presents the descriptive statistics and the intercorrelations between the focal constructs of the study. In examining the descriptive statistics of our study, a nuanced understanding of the various facets of working from home emerged. Job demands or stressors, conceptualized as work overload, role ambiguity, job insecurity, and work-home conflict, presented relatively lower mean scores, suggesting low perceptions of the WFH job demands as stressors. On the other hand, WA showed a slightly higher mean score of 3.22 (SD = 1.59), pointing to a moderate level of anxiety experienced by employees. In contrast, the characteristics of digital technology used for WFH – perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and technical support – demonstrated high mean scores, suggesting strong perceptions of the efficacy and supportive nature of the WFH digital technology. Additionally, PsyCap had the highest mean score of 6.08 (SD = 1.08), suggesting very high levels of psychological resources among the respondents, which could play a critical role in positively influencing their WFH experience.

4.2. Hypothesis Testing

Linear hierarchical regression analysis was conducted for predicting WA. In the first step (not shown in

Table 4), WA was regressed on the control variables. In this model (F = 1.18, p = .2948, R

2 = .0163), all control variables were not significant predictors of WA. In the second step, the model (F = 3.83, p < .001, R

2 = .2504) incorporating WFH job demands (i.e., RA, WO, JI, WHC) accounted for an additional 23.41%

11.09, p < .001) of the variance in WA. In this model, JI (B = .26, t = 3.39, p < 0.01) and RA (B = .34, t = 3.09, p < 0.01) were significant predictors of WA. In the third step, the interactions of gender and WFH job demands were added as predictors of WA. This model (F = 4.33, p < .001, R

2 = .3092) accounted for an additional 5.88% (

= 2.94, p < .05) of the variance in WA. The inclusion of the interaction terms resulted in RA becoming nonsignificant (p = 0.2082) but JI (B = .41, t = 4.18, p < 0.001) retained significance. Three of the four interactions were significant: Male

WO (B = -.37, t = -2.29, p < 0.05), Male

JI (B = -.32, t = -2.08, p < 0.05) and Male

WHC (B = .45, t = 2.90, p < 0.01). Results are summarized in

Table 4.

Logistic hierarchical regression analysis was conducted for predicting PsyCap. On the first step (not shown in

Table 4), PsyCap was regressed on the control variables. In this model with pseudo-R

2 = .0342, all control variables were not significant predictors of PsyCap. On the second step, the model incorporating WA and DTC (i.e., PU, PEU, TS) accounted for an additional 9.31% (

= 41.78, p < .001) of the variance in PsyCap. In this model, only WA (B = .2765,

= 5.13, p < 0.05) was a significant predictor of PsyCap. On the third step, the interactions of DTC and WA were added as predictors of PsyCap. This model accounted for an additional 2.87% (

= 41.78, p < .01) of the variance in PsyCap and had two significant predictors of PsyCap: WA (B = .3518,

= 6.54, p < 0.05) and the interaction, PEU

WA (B = .3246,

= 4.03, p < 0.05). Results are summarized in

Table 4.

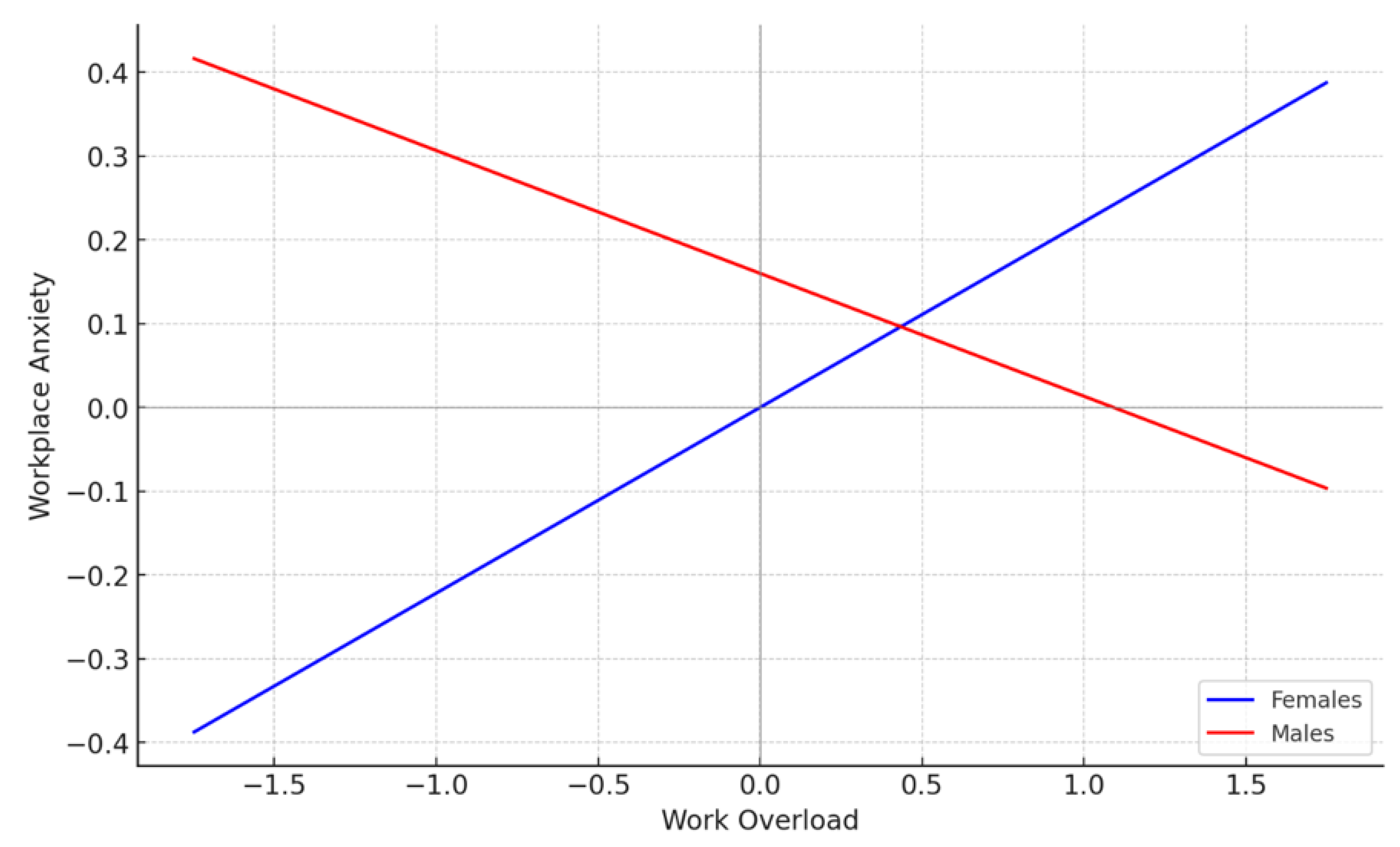

A simple slope analysis (Aiken & West, 1991) was conducted to probe the nature of the significant Male

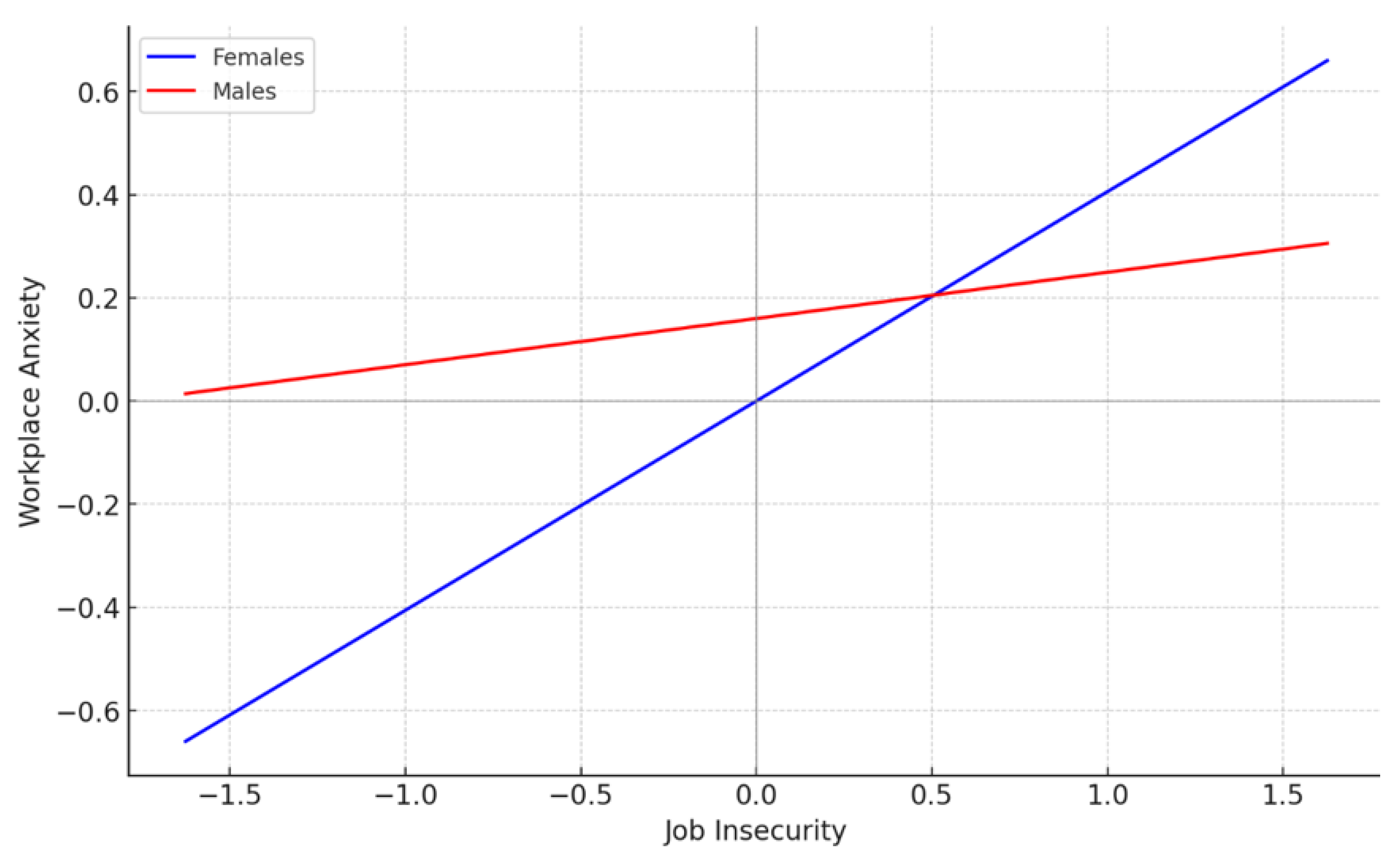

WO interaction. The simple slope for females (B = .2217, SE = .0933, t(138) = 2.377, p < .05) was significant, while the simple slope for males (B = -.1467, SE = 0.1845, t(138) = -0.795, p =.4278) was not significant, showing that for females, an increase in WO is associated with an increase in WA. For the Male

JI interaction, the simple slope for females (B = .4058, SE = .0971, t(138) = 4.178, p < .001) was significant, while the simple slope for males (B = .0896, SE = .1388, t(138) = .646, p =.5196) was not significant, showing that for females, an increase in JI is associated with an increase in WA. Interestingly, for the Male

WHC interaction, both slopes were only significant at the 10% level: females (B = -.1413, SE = .0781, t(138) = -1.809, p = .0726) and males (B = .3075, SE = .1849, t(138) = 1.663, p = .0986). These findings underscore the conditional influence of gender on the WO-WA and JI-WA associations. Specifically, the impact of WO and JI on WA is stronger for females.

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 illustrate the slopes.

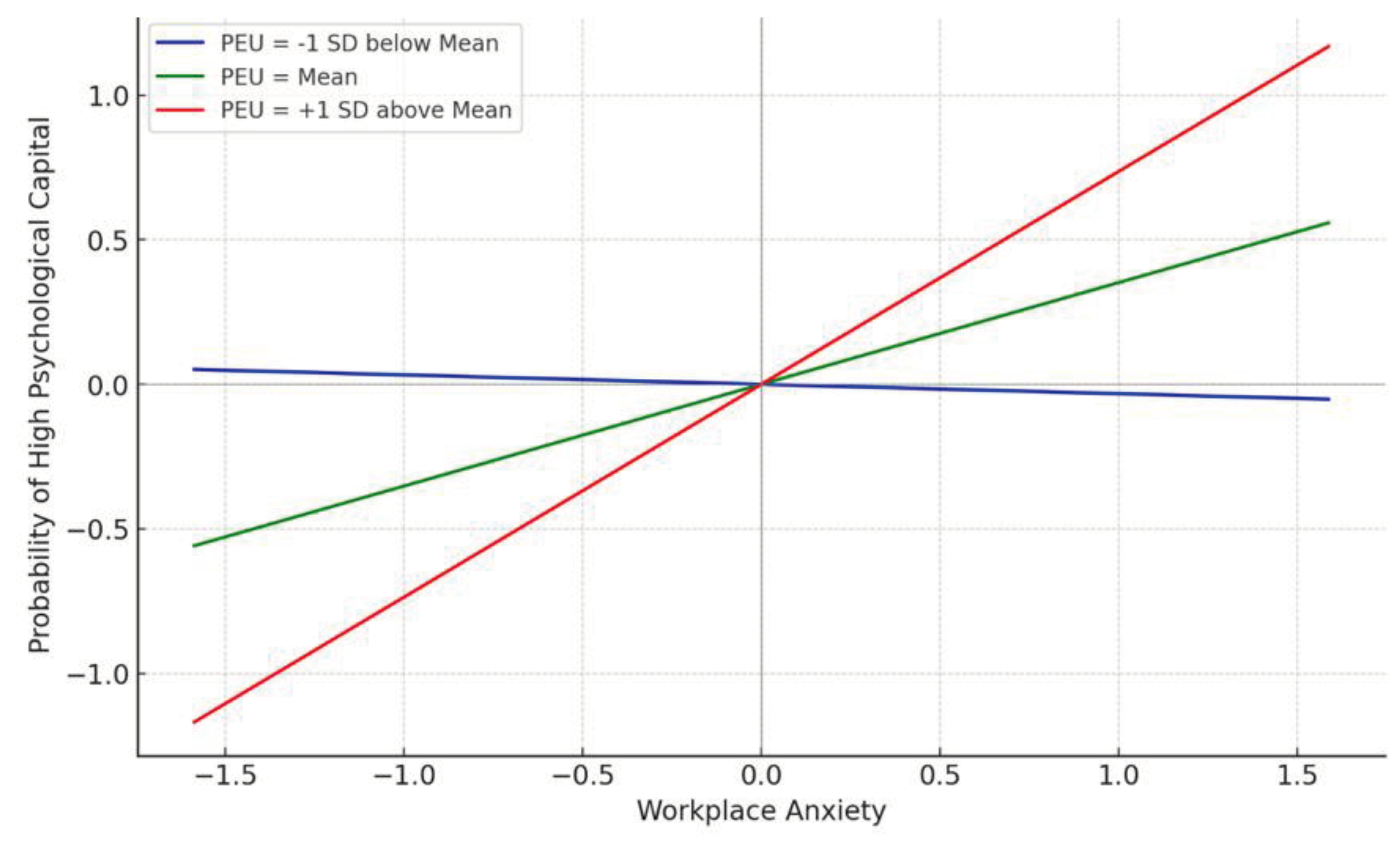

Simple slope analysis was conducted to probe the nature of the significant PEU

WA interaction. At one standard deviation below the mean of PEU, the relationship between WA and PsyCap was not statistically significant (B = -.0325, SE = .2710, t(139) = -.1198, p =.9048), indicating that lower PEU did not significantly alter the impact of WA on PsyCap. Conversely, at one standard deviation above the mean of PEU, the slope was positive and statistically significant (B = .7361, SE = .1941, t(139) = 3.7923, p < .01), suggesting that the impact of WA on PsyCap is stronger when PEU is higher. At the mean level of PEU, the effect of WA on PsyCap was positive and significant (B = .3518, SE = .1375, t(139) = 2.5585, p < .05). These findings underscore the conditional influence of PEU on the WA-PsyCap association. Specifically, the positive impact of WA on PsyCap is most pronounced under conditions of high PEU.

Figure 4 illustrates the slopes.

5. Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic precipitated a global, involuntary shift to WFH. Despite a post-pandemic reduction in WFH, there is scholarly consensus that WFH represents an enduring transition in the post-pandemic work environment (Aksoy et al., 2022). Given this enduring nature, it is crucial to understand the stressors it introduces and their consequent impact on employee emotions. Therefore, this study set out to investigate how WFH job demands affect WA and, subsequently, the influence of WA on PsyCap. Our research specifically aimed to deepen the understanding of WFH job demands and WA within the context of developing nations, notably South Africa, where such research is scarce. The focus on WFH and WA stems from their increasing prominence among both academics and practitioners since the onset of the pandemic. Addressing calls for more research to “understand how employees feel emotionally in organizational settings” (Yip et al., 2020, p. 3), this study contributes to the burgeoning scholarly focus, often termed the “affective revolution,” on how emotions influence workplace behavior. Moreover, to the best of our knowledge, our study is among the first empirical testing of the TWA, a theory still in its nascent stages of empirical validation.

Following the research objectives outlined earlier, our study addressed the following questions: What is the nature of the relationship between WFH environment and WA; and Does gender influence the WFH environment-WA relationship? First, we aimed to understand the nature of the relationship between WFH and WA, particularly the role of WFH job demands. Our findings, mostly aligned with our hypotheses, showed that all the WFH job demands, except RA, had direct (WO, JI) and/or indirect effects (WO, JI, WHC) on WA. The indirect effects, conditional on gender, answered our second question. Specifically, our findings showed that while both high WO and JI were associated with high WA, this relationship was stronger for females. Surprisingly, RA was found to have no direct or indirect effect on WA. A possible explanation for this finding is that our respondents might have adapted to a WHF environment where they leveraged the flexibility or autonomy inherent in such settings, rendering RA less impactful on their WA levels (Jackson & Schuler, 1985; Spector, 1986).

Our study also addressed these two questions: What is the nature of the relationship between WA and PsyCap; and Do DTC which support WFH, influence the WA-PsyCap relationship? Contrary to our expectations, there was a strong positive association between WA and PsyCap, however this finding is in line with previous research (e.g., Barclay & Kiefer, 2019; Cheng et al., 2023; Mao et al., 2021), which found that WA can have facilitative effects in the workplace. Because individuals with high PsyCap are characterized by resilience, optimism, self-efficacy, and hope, these traits could enable them to perceive and respond to anxiety differently, perhaps viewing challenging situations as opportunities for growth rather than threats, thus fostering a positive association with WA (Avey et al., 2011).

Our finding that the positive impact of WA on PsyCap is most pronounced under conditions of high PEU answered our second question, and suggests that individuals who perceive digital technology that supports WFH as easy to use benefit more from the facilitative effects of WA on PsyCap. This finding suggests that when employees find digital technology easy to use, their WA might be less likely to negatively impact their PsyCap. This is in line with Davis and colleagues’ (1989) technology acceptance model (TAM), which emphasizes the importance of ease of use in determining technology adoption and user attitudes. If employees find technology user-friendly, it can mitigate the anxiety associated with its use, thereby preserving, or even enhancing, their psychological resources. Contrary to expectations, the association between WA and PsyCap was not conditional on either PU or TS. The lack of significant moderation by TS and PU could be explained by the technology-organization-environment (TOE) framework by Tornatzky and Fleischer (1990), which suggests that the organizational and environmental context might play a more critical role than the perceived attributes of technology itself. It is possible that in our study’s context, factors such as organizational culture, support, and external environmental conditions overshadowed the influence of TS and PU.

5.1. Theoretical Contribution

This study makes several critical theoretical contributions. First, it contributes to the literature by offering support for the differential impact WFH job demands have on WA. Second, it offers empirical validation for the TWA, marking a significant step in the theory's development. Third, by examining interactions within the TWA framework, the research uncovers nuanced understandings of how job demands associated with WFH relate to WA, and how WA in turn influences PsyCap. Fourth, our findings contribute to the limited understanding of the impact of WA (Cheng et al., 2023) by elucidating the WA-PsyCap relationship and establishing WA as a key predictor of PsyCap, thus broadening the scope of understanding of the predictors of PsyCap. Fifth, the study corroborates Cheng and McCarthy’s (2018) proposition about the facilitative, or ‘bright side,’ effects of WA, reinforcing the idea that anxiety can sometimes enhance performance. Lastly, by centering on South Africa – a non-WEIRD context – this research responds to the call for more diverse samples in behavioral research (Henrich et al., 2010), thereby adding valuable insights from the developing world’s perspective.

5.2. Practical Implications

The findings of this study have several practical implications. Our research identifies the WFH job demands that are positively associated with WA, and in turn the positive influence of WA on PsyCap. This provides a starting point for how WA can be managed. On one hand, because feelings of job insecurity and too much work contribute to WA, leaders and managers can target these job demands to reduce WA since high WA has negative effects (McCarthy et al., 2016; Fu et al., 2020). On the other hand, because WA is positively related to PsyCap, this suggests that leaders and managers should not seek to eliminate anxiety completely from the workplace, but rather to understand how to use WA in beneficial ways. This means that leaders and managers should put processes in place to assess the levels of WA and apply appropriate interventions to either alleviate or harness it. The positive relationship found in our study between WA and PsyCap challenges the conventional view of WA as solely detrimental, paving the way for a more nuanced understanding of its role. Practically, organizations could implement training programs where employees learn to distinguish between maladaptive and adaptive WA. This is particularly important as companies design and implement their WFH policies for a post-pandemic work environment.

Further, the significant interaction between WFH job demands and gender underscores the necessity for gender-sensitive approaches in managing WA. Finally, the significant interaction between WA and PEU of digital technology suggests a proactive approach in training. By enhancing employees’ comfort and proficiency with these technologies, organizations can ensure that digital tools are perceived as user-friendly, further aiding in the beneficial management of WA. This approach is not only pertinent in adapting to new work arrangements, but also instrumental in fostering a productive and psychologically healthy work environment.

5.3. Strengths, Limitations, and Avenues for Future Research

This study has several strengths. Methodologically, the strength of our study lies in the use of hierarchical regression analysis, which not only incrementally elucidates the contribution of different variable blocks to the variance in WA and PsyCap, but also offers detailed insights critical for both theoretical understanding and practical application. Theoretically, our conceptual model (see

Figure 1), which is firmly grounded in the TWA and JD-R models, elucidates the complex associations between WFH job demands, WA, DTC, and PsyCap. Additionally, our study highlights the complex nature of WA by elucidating its adaptive function. Finally, this study contributes unique insights into WA from South Africa, a non-WEIRD (Henrich et al., 2010) setting, thereby enriching the understanding of WA.

Despite these strengths, limitations exist that suggest useful future research. First, the study’s cross-sectional design limits causal inference, thus future research should explore causal relationships using longitudinal or experimental designs. Second, reliance on self-reported data, while necessary, may introduce bias, however it is also important to recognize that the constructs being investigated are inherently subjective, making self-reporting a necessary and valuable approach for capturing personal experiences and perceptions. Third, the specific focus on the South African context, while valuable, may limit generalizability, highlighting the need for research in diverse cultural and economic settings. Fourth, the sample size of the present study and the highly skewed distribution of PC limited the use of more complex analytical techniques, such as structural equation modeling, which allows for the consideration of model fit. Future studies should consider larger sample sizes drawn from diverse populations and contexts.

Fifth, this study, while comprehensive, did not account for several established predictors of WA and PsyCap. These include dispositional WA and emotional labor demands (Cheng & McCarthy, 2018), along with organizational culture and broader macro-environmental factors encompassing health, politics, and economics (Yip et al., 2020). Additionally, known influences on PsyCap such as individual differences, core self-evaluations, and empowering leadership behaviors (Luthans et al., 2017) were not controlled for. Future research would benefit from incorporating these variables to provide a more holistic understanding of WA and PsyCap. Sixth, we recognize that our research, conducted through surveys involving employees from various organizations, lends a degree of generalizability to our findings, yet it is important to note that concentrating on a single organization could provide a more focused empirical testing of the TWA through the conceptual model developed in this study.

Seventh, although we showed that WA has a positive effect on PsyCap, we have not empirically investigated the specific mechanisms involved. Future research should examine whether WA increases PsyCap through: 1) heightened awareness and attention to detail, leading to fewer mistakes and higher quality output that boosts the self-efficacy component of PsyCap (Eysenck et al., 2007); and 2) the development of adaptive coping strategies (Aspinwall & Taylor, 1997) that contribute to resilience, a key component of PsyCap. Finally, while our study highlights a positive relationship between WA and PsyCap, a key limitation lies in the lack of guidance on the threshold at which the detrimental effects of high WA begin to manifest. While moderate levels of WA can be beneficial, as suggested by Eysenck et al. (2007), anxiety is often linked with negative outcomes such as diminished job performance (McCarthy et al., 2016; Fu et al., 2020), unethical behaviors (Hillebrandt & Barclay, 2022), and increased turnover intentions (Haider et al., 2020). Therefore, future research should aim through experimental methods to identify the ‘tipping point’ at which the adaptive aspects of WA give way to its detrimental effects. This would provide more nuanced insights into the complex dynamics of WA and enable practitioners to design interventions that harness its positive aspects while mitigating its negative impact.

6. Conclusion

This study provides a comprehensive investigation into the impact of WFH job demands on WA, and subsequently, how WA influences PsyCap. Our findings show that WO and JI exert both direct and gender-conditioned effects on WA. More importantly, we found that WA, often perceived with a negative connotation, can indeed have facilitative effects on PsyCap, suggesting its adaptive potential in the workplace. These insights offer a major contribution to the empirical validation of the TWA. We are optimistic that the conceptual model developed in this study will spark further scholarly inquiry into the dualistic nature of WA – unraveling both its adverse and beneficial facets. This research, therefore, not only extends the current research on WA, but also lays the groundwork for future studies to explore the complex interplay between environmental stressors, emotions, and psychological resources in the evolving post-pandemic work environment.

Author Contributions

Frank Magwegwe functioned as the principal designer of the article, overseeing its overall writing and editing, and bears the primary responsibility for its content and organization. The foundational data for this research, which contributed significantly to the article, were gathered by Snenhlanhla Sithole for her MBA research.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the GORDON INSTITUTE OF BUSINESS SCIENCE, UNIVERSITY OF PRETORIA.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available at the Open Science Framework repository, accessible via the following link:

https://osf.io/q8wtc/?view_only=30930ff9bbe940519256452e968d5030. This repository includes all relevant datasets necessary to interpret, replicate, and build upon the research results.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to express sincere gratitude to Nomathemba Magwegwe, who provided invaluable secretarial assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage.

- Aksoy, C. G., Barrero, J. M., Bloom, N., Davis, S. J., Dolls, M., & Zarate, P. (2022). Working from home around the world (No. w30446). National Bureau of Economic Research. https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w30446/w30446.pdf.

- Aksoy, C. G., Barrero, J. M., Bloom, N., Davis, S. J., Dolls, M., & Zarate, P. (2023). Working from home around the globe: 2023 Report (No. 53). EconPol Policy Brief. https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/275827/1/185640806X.pdf.

- Alnazly, E. K., Allari, R., Alshareef, B. E., & Abu Al-khair, F. (2023). Analyzing Role Overload, Mental Health, and Quality of Life Among Jordanian Female Healthcare Professionals: A Cross-Sectional Study. International Journal of Women's Health, 1917-1930. [CrossRef]

- Aspinwall, L. G., & Taylor, S. E. (1997). A stitch in time: self-regulation and proactive coping. Psychological Bulletin, 121(3), 417. [CrossRef]

- Avey, J. B., Reichard, R., Luthans, F., & Mhatre, K. (2011). Meta-analysis of the impact of positive psychological capital on employee attitudes, behaviors and performance. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 22, 127-152. [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2007). The job demands-resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22(3), 309-328. [CrossRef]

- Barclay, L. J., & Kiefer, T. (2019). In the aftermath of unfair events: Understanding the differential effects of anxiety and anger. Journal of Management, 45(5), 1802-1829. [CrossRef]

- Buss, D. M., & Schmitt, D. P. (1993). Sexual strategies theory: An evolutionary perspective on human mating. Psychological Review, 100(2), 204-232. [CrossRef]

- Bussey, K., & Bandura, A. (1999). Social cognitive theory of gender development and differentiation. Psychological Review, 106, 676-713. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G. H. L., & Chan, D. K. S. (2008). Who suffers more from job insecurity? A meta-analytic review. Applied Psychology, 57(2), 272-303. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, B. H., & McCarthy, J. M. (2018). Understanding the dark and bright sides of anxiety: A theory of workplace anxiety. Journal of Applied Psychology, 103(5), 537-560. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, B. H., Zhou, Y., & Chen, F. (2023). You've got mail! How work e-mail activity helps anxious workers enhance performance outcomes. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 144, 103881. [CrossRef]

- Davis, F. D., Bagozzi, R. P., & Warshaw, P. R. (1989). User acceptance of computer technology: A comparison of two theoretical models. Management Science, 35(8), 982-1003. [CrossRef]

- Deloitte. (2023). 2023 Gen Z and Millennial Survey. Retrieved January 18, 2023, from https://www.deloitte.com/global/en/issues/work/content/genzmillennialsurvey.html.

- Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 499-512. [CrossRef]

- Eagly, A. H., & Wood, W. (1999). The origins of sex differences in human behavior: Evolved dispositions versus social roles. American Psychologist, 54(6), 408-423. [CrossRef]

- Eysenck, M. W., Derakshan, N., Santos, R., & Calvo, M. G. (2007). Anxiety and cognitive performance: attentional control theory. Emotion, 7(2), 336. [CrossRef]

- Gallup. (2023). State of the Global Workplace Report 2022. Retrieved January 18, 2023, from https://www.gallup.com/workplace/349484/state-of-the-global-workplace.aspx.

- Haider, S., Fatima, N., & de Pablos-Heredero, C. (2020). A three-wave longitudinal study of moderated mediation between perceptions of politics and employee turnover intentions: The role of job anxiety and political skills. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 36, 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Harlos, K., Gulseren, D., O'Farrell, G., Josephson, W., Axelrod, L., Hinds, A., & Montanino, C. (2023). Gender and perceived organizational support as moderators in the relationship between role stressors and workplace bullying of targets. Frontiers in Communication, 8, 1176846. [CrossRef]

- Henrich, J., Heine, S. J., & Norenzayan, A. (2010). Most people are not WEIRD. Nature, 466(7302), 29. [CrossRef]

- Hillebrandt, A., & Barclay, L. J. (2022). How COVID-19 can promote workplace cheating behavior via employee anxiety and self-interest – And how prosocial messages may overcome this effect. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 43(5), 858-877. [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44, 513-524. [CrossRef]

- HSE. (2023). HSE work-related stress, depression, or anxiety statistics 2021/2022. Retrieved January 18, 2023, from https://www.hse.gov.uk/statistics/overview.htm.

- Hyde, J. S. (2014). Gender similarities and differences. Annual Review of Psychology, 65, 373-398. [CrossRef]

- Jackson, S. E., & Schuler, R. S. (1985). A meta-analysis and conceptual critique of research on role ambiguity and role conflict in work settings. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 36(1), 16-78. [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R. S. (2006). Emotions and interpersonal relationships: Toward a person-centered conceptualization of emotions and coping. Journal of Personality, 74(1), 9-46. [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F., & Youssef-Morgan, C. M. (2017). Psychological capital: An evidence-based positive approach. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 4(1), 339-366. [CrossRef]

- Mao, J., Chang, S., Gong, Y., & Xie, J. L. (2021). Team job-related anxiety and creativity: Investigating team-level and cross-level moderated curvilinear relationships. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 42(1), 34-47. [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, J. M., Trougakos, J. P., & Cheng, B. H. (2016). Are anxious workers less productive workers? It depends on the quality of social exchange. Journal of Applied Psychology, 101(2), 279-291. [CrossRef]

- Pretorius, T. B., & Padmanabhanunni, A. (2022). The beneficial effects of professional identity: the mediating role of teaching identification in the relationship between role stress and psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(18), 11339. [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, N. P., LePine, J. A., & LePine, M. A. (2007). Differential challenge stressor-hindrance stressor relationships with job attitudes, turnover intentions, turnover, and withdrawal behavior: a meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(2), 438-454. [CrossRef]

- Sanz-Vergel, A. I., Demerouti, E., Mayo, M., & Moreno-Jiménez, B. (2011). Work–home interaction and psychological strain: The moderating role of sleep quality. Applied Psychology, 60(2), 210-230. [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W. B. (2017). Applying the job demands-resources model: A ‘how to’ guide to measuring and tackling work engagement and burnout. Organizational Dynamics, 46(2), 120-132. [CrossRef]

- Smith, C. A., & Ellsworth, P. C. (1985). Patterns of cognitive appraisal in emotion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 48(4), 813. [CrossRef]

- Spielberger, C. D. (1972). Conceptual and methodological issues in anxiety research. In C. D. Spielberger (Ed.), Anxiety: Current trends in theory and research (pp. 481–493). Academic Press. [CrossRef]

- Spielberger, C. D. (1985). Anxiety, cognition, and affect: A state-trait perspective. In A. H. Tuma & J. D. Maser (Eds.), Anxiety and the anxiety disorders (pp.171–182). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

- Tornatzky, L. G., & Fleischer, M. (1990). The processes of technological innovation. Lexington Books.

- Wang, C., Yuan, T., Feng, J., & Peng, X. (2023). How can leaders alleviate employees' workplace anxiety caused by information overload on enterprise social media? Evidence from Chinese employees. Information Technology & People, 36(1), 224-244. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Mental health at work. Retrieved January 18, 2023, from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-at-work.

- Xanthopoulou, D., Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2007). The role of personal resources in the job demands-resources model. International Journal of Stress Management, 14(2), 121-141. [CrossRef]

- Yip, J. A., Levine, E. E., Brooks, A. W., & Schweitzer, M. E. (2020). Worry at work: How organizational culture promotes anxiety. Research in Organizational Behavior, 40, 100124. [CrossRef]

- Zeidner, M., & Ben-Zur, H. (2014). Effects of an experimental social stressor on resources loss, negative affect, and coping strategies. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 27(4), 376-393. [CrossRef]

- Zeidner, M., Ben-Zur, H., & Reshef-Weil, S. (2011). Vicarious life threat: An experimental test of Conservation of Resources (COR) theory. Personality and Individual Differences, 50(5), 641-645. [CrossRef]

| 1 |

The survey was conducted between April and May 2023, gathering a total of 42,426 responses from 34 different countries. The calculation for the percentage of workdays spent working from home was based on the standard five-day workweek model. |

| 2 |

These job demands are also referred to as role or work stressors and have been thoroughly examined in the psychological, sociological, and organizational studies literatures as contributors to role stress, defined as any aspects of role expectations that lead to negative outcomes (i.e., role strain) for those occupying the roles and a key component of role theory. |

| 3 |

Researchers used different measures of anxiety such as the STAI-T, a measure of trait anxiety, the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12) that has an anxiety component, and Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) scale. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).