Submitted:

05 March 2024

Posted:

06 March 2024

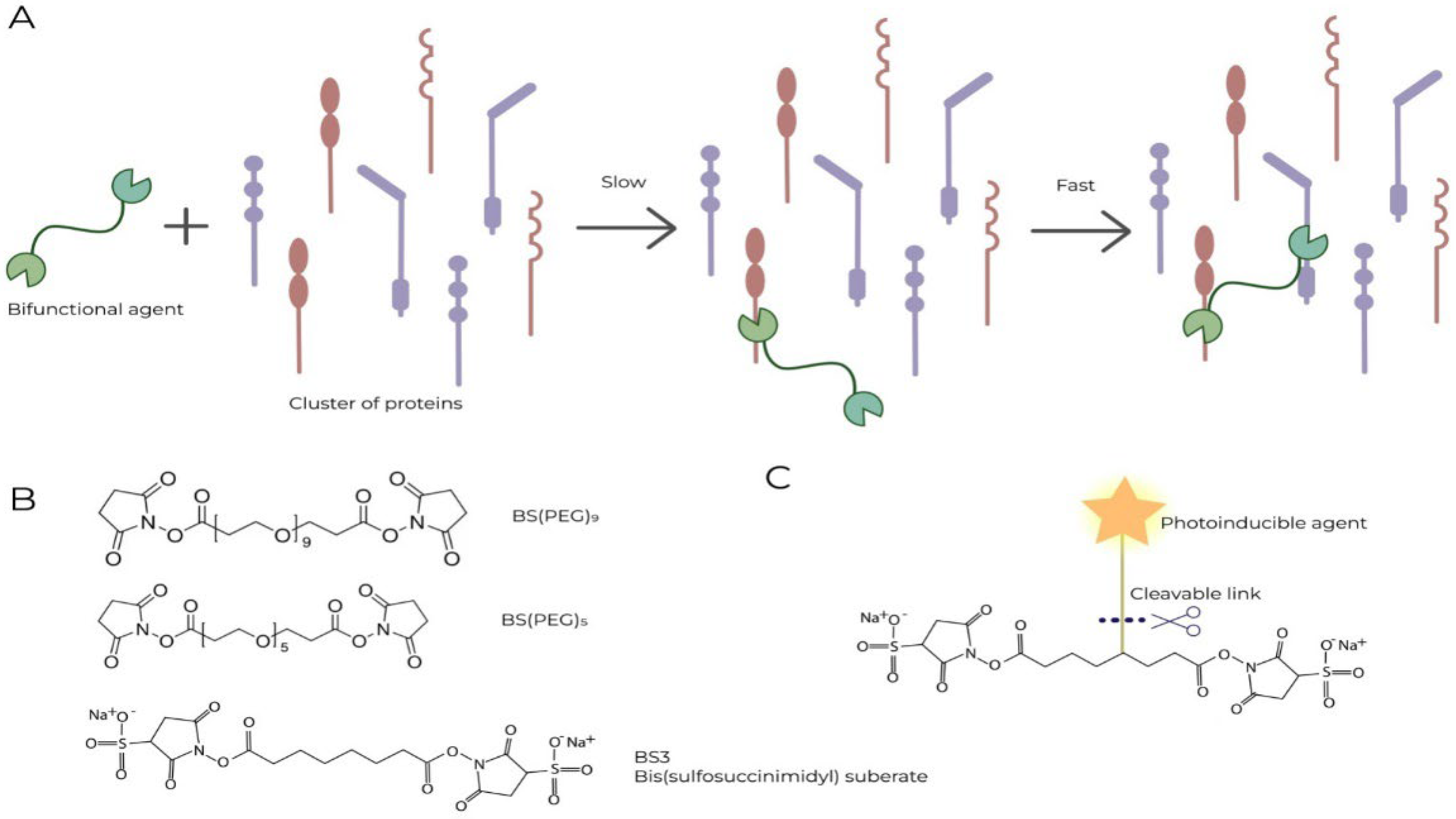

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction. Chemotherapy: Fame and Failure

2. Basic Definitions, Terms, and a Brief Presentation of Available Information

2.1. Tumor Tissue Compartments

2.2. Basement Membrane and Extracellular Matrix

2.3. Tumor Microenvironment (TME)

2.4. Extracellular Matrix

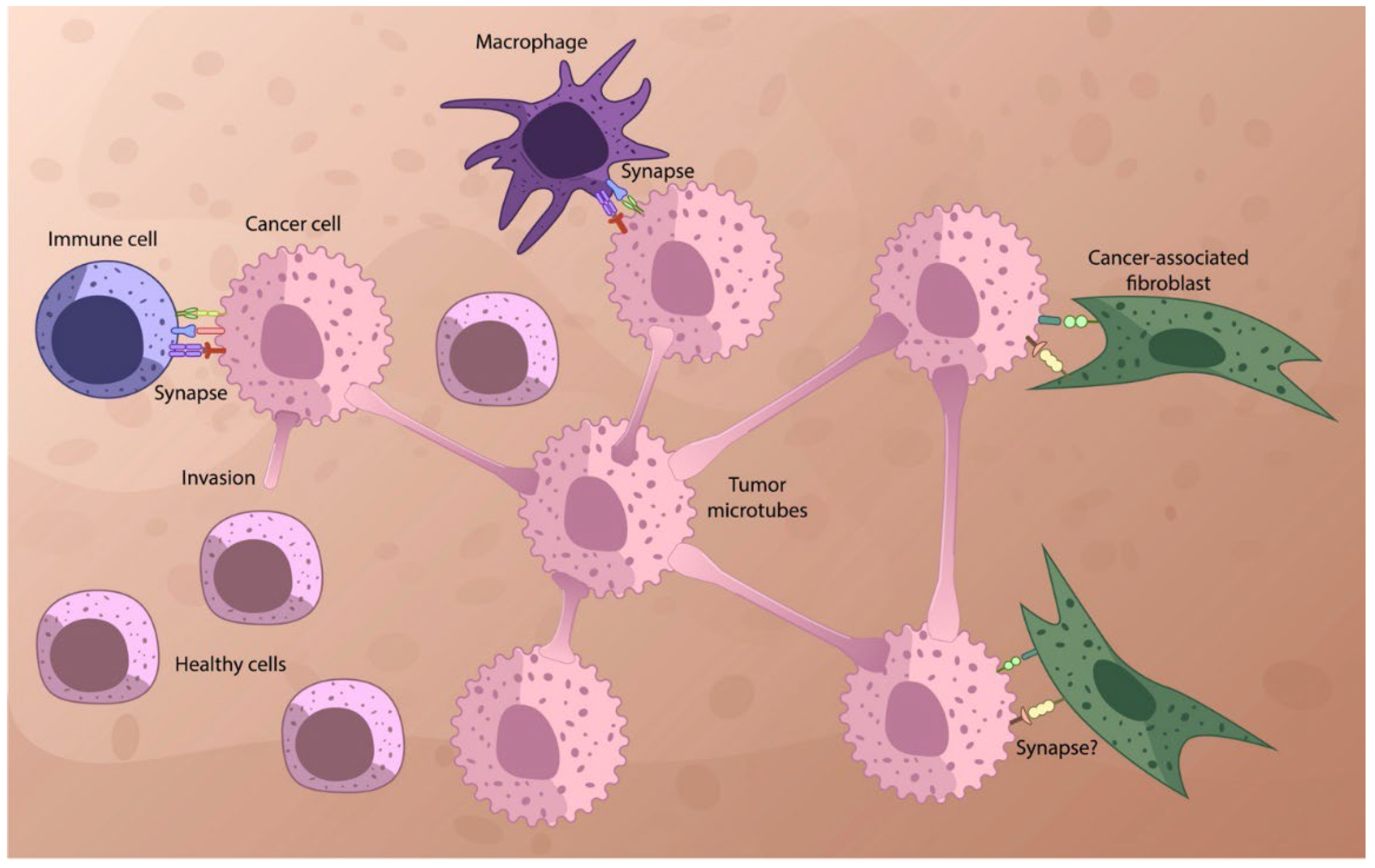

2.5. Paracrine and Juxtacrine: Two Types of Cell Signaling

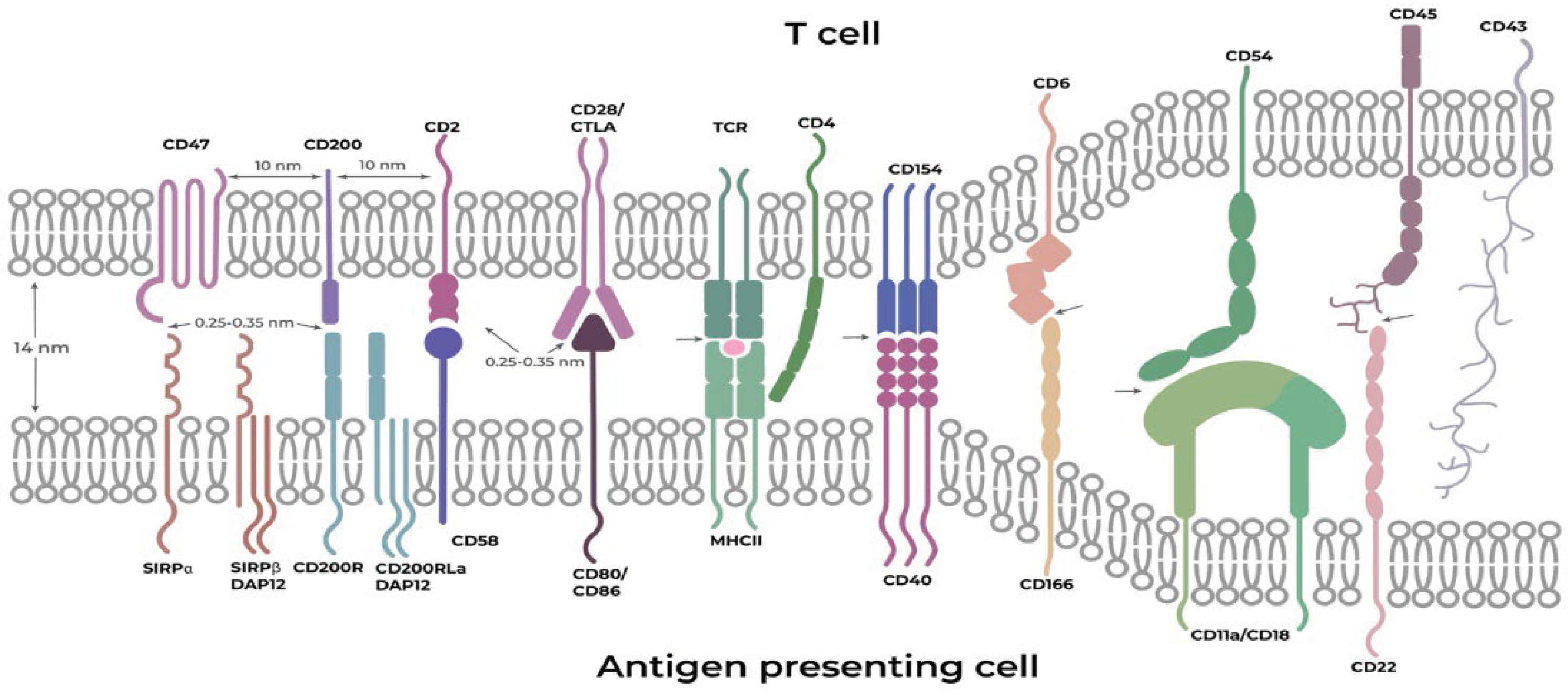

3. General Physicochemical Principles of Direct Intercellular Contacts

3.1. Two Postulate Principle

3.2. Immune and Other Cells within Tumor Compartments: A Quick Glance

3.3. Fibroblasts, Immune and Cancer Cells Interactions

3.4. Communication of the Cancer and Microenvironmental cells—a Supramolecular Target for Chemotherapy

4. Simple Principles of Specific Chemical Effects on Synapses

5. Instead of a Conclusion: Immunochemotherapy as a General Strategy Aimed at Poorly Fortified Areas of Cancer Tumors

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brawley, O.W.; Goldberg, P. The 50 years’ war: The history and outcomes of the National Cancer Act of 1971. Cancer 2021, 127, 4534–4540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanahan, D. Rethinking the war on cancer. Lancet 2014, 383, 558–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surh, Y.-J. The 50-year war on cancer revisited: should we continue to fight the enemy within? Journal of Cancer Prevention 2021, 26, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henson, D.E. 25th Anniversary of the Signing of the National Cancer Act, December 23, 1971. Introduction. Cancer 1996, 78, 2582–2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, H. Warhead. EMBO Rep 2011, 12, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnenschein, C.; Soto, A.M. Over a century of cancer research: Inconvenient truths and promising leads. PLoS biology 2020, 18, e3000670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, M. Is cancer chemotherapy dying? Asian journal of transfusion science 2016, 10, S1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bizzarri, M. Do new anticancer drugs really work? A serious concern. Organisms. Journal of Biological Sciences 2017, 1, 9–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Fazal, Z.; Freemantle, S.J.; Spinella, M.J. Mechanisms of cisplatin sensitivity and resistance in testicular germ cell tumors. Cancer Drug Resist 2019, 2, 580–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emens, L.A.; Middleton, G. The interplay of immunotherapy and chemotherapy: harnessing potential synergies. Cancer Immunol Res 2015, 3, 436–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wargo, J.A.; Reuben, A.; Cooper, Z.A.; Oh, K.S.; Sullivan, R.J. Immune Effects of Chemotherapy, Radiation, and Targeted Therapy and Opportunities for Combination With Immunotherapy. Semin Oncol 2015, 42, 601–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Waxman, D.J. Immunogenic chemotherapy: Dose and schedule dependence and combination with immunotherapy. Cancer Lett 2018, 419, 210–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sverdlov, E.D. Genetic surgery—a right strategy to attack cancer. Curr Gene Ther 2011, 11, 501–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Ren, Y.; Weng, S.; Xu, H.; Li, L.; Han, X. A New Trend in Cancer Treatment: The Combination of Epigenetics and Immunotherapy. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 809761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alekseenko, I.; Kondratyeva, L.; Chernov, I.; Sverdlov, E. From the Catastrophic Objective Irreproducibility of Cancer Research and Unavoidable Failures of Molecular Targeted Therapies to the Sparkling Hope of Supramolecular Targeted Strategies. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, U.; Dey, A.; Chandel, A.K.S.; Sanyal, R.; Mishra, A.; Pandey, D.K.; De Falco, V.; Upadhyay, A.; Kandimalla, R.; Chaudhary, A.; et al. Cancer chemotherapy and beyond: Current status, drug candidates, associated risks and progress in targeted therapeutics. Genes Dis 2023, 10, 1367–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Lei, X.; Zhu, J.; Zhong, Y.; Yang, J.; Wang, J.; Tan, H. Radiotherapy/Chemotherapy-Immunotherapy for Cancer Management: From Mechanisms to Clinical Implications. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 2023, 2023, 7530794, PMID: 36778203; PMCID: PMC9911251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanahan, D. Hallmarks of Cancer: New Dimensions. Cancer Discov 2022, 12, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, T.; Dai, L.J.; Wu, S.Y.; Xiao, Y.; Ma, D.; Jiang, Y.Z.; Shao, Z.M. Spatial architecture of the immune microenvironment orchestrates tumor immunity and therapeutic response. J Hematol Oncol 2021, 14, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendry, S.; Salgado, R.; Gevaert, T.; al., e. Assessing Tumor-infiltrating Lymphocytes in Solid Tumors: A Practical Review for Pathologists and Proposal for a Standardized Method From the International Immunooncology Biomarkers Working Group: Part 1: Assessing the Host Immune Response, TILs in Invasive Breast Carcinoma and Ductal Carcinoma In Situ, Metastatic Tumor Deposits and Areas for Further Research. Adv Anat Pathol 2017, 24, 235-251. [CrossRef]

- Koelzer, V.H.; Lugli, A. The tumor border configuration of colorectal cancer as a histomorphological prognostic indicator. Front Oncol 2014, 4, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, D.; Liu, J.; Qian, H.; Zhuang, Q. Cancer-associated fibroblasts: from basic science to anticancer therapy. Experimental & Molecular Medicine 2023, 55, 1322–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalluri, R. The biology and function of fibroblasts in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2016, 16, 582–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, G.F.; Xu, R.H. Function of cancer cell-derived extracellular matrix in tumor progression. J. Cancer. Metastasis. Treat. 2016, 2, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Chaudhuri, O. Beyond proteases: Basement membrane mechanics and cancer invasion. J Cell Biol 2019, 218, 2456–2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brás, M.M.; Sousa, S.R.; Carneiro, F.; Radmacher, M.; Granja, P.L. Mechanobiology of Colorectal Cancer. Cancers 2022, 14, 1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bane, A. Ductal carcinoma in situ: what the pathologist needs to know and why. Int J Breast Cancer 2013, 2013, 914053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelley, L.C.; Lohmer, L.L.; Hagedorn, E.J.; Sherwood, D.R. Traversing the basement membrane in vivo: a diversity of strategies. Journal of Cell Biology 2014, 204, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazari, S.S.; Doyle, A.D.; Yamada, K.M. Mechanisms of Basement Membrane Micro-Perforation during Cancer Cell Invasion into a 3D Collagen Gel. Gels 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaggioli, C.; Hooper, S.; Hidalgo-Carcedo, C.; Grosse, R.; Marshall, J.F.; Harrington, K.; Sahai, E. Fibroblast-led collective invasion of carcinoma cells with differing roles for RhoGTPases in leading and following cells. Nature Cell Biology 2007, 9, 1392–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, A.; Cortes, E.; Lachowski, D.; Oertle, P.; Matellan, C.; Thorpe, S.D.; Ghose, R.; Wang, H.; Lee, D.A.; Plodinec, M.; et al. GPER Activation Inhibits Cancer Cell Mechanotransduction and Basement Membrane Invasion via RhoA. Cancers (Basel) 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo-Cordero, J.J.; Hodgson, L.; Condeelis, J.S. Spatial regulation of tumor cell protrusions by RhoC. Cell Adh Migr 2014, 8, 263–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glentis, A.; Oertle, P.; Mariani, P.; Chikina, A.; El Marjou, F.; Attieh, Y.; Zaccarini, F.; Lae, M.; Loew, D.; Dingli, F.; et al. Cancer-associated fibroblasts induce metalloprotease-independent cancer cell invasion of the basement membrane. Nature Communications 2017, 8, 924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Arcangelo, E.; Wu, N.C.; Cadavid, J.L.; McGuigan, A.P. The life cycle of cancer-associated fibroblasts within the tumour stroma and its importance in disease outcome. British Journal of Cancer 2020, 122, 931–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido-Urbani, S.; Vonlaufen, A.; Stalin, J.; De Grandis, M.; Ropraz, P.; Jemelin, S.; Bardin, F.; Scheib, H.; Aurrand-Lions, M.; Imhof, B.A. Junctional adhesion molecule C (JAM-C) dimerization aids cancer cell migration and metastasis. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)—Molecular Cell Research 2018, 1865, 638–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardiner, J.C.; Cukierman, E. Meaningful connections: Interrogating the role of physical fibroblast cell-cell communication in cancer. Adv Cancer Res 2022, 154, 141–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamanos, N.K.; Piperigkou, Z.; Passi, A.; Gotte, M.; Rousselle, P.; Vlodavsky, I. Extracellular matrix-based cancer targeting. Trends Mol Med 2021, 27, 1000–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popova, N.V.; Jücker, M. The Functional Role of Extracellular Matrix Proteins in Cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rijal, G.; Becker, S. Carcinoma Cell-Based Extracellular Matrix Modulates Cancer Cell Communication. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Tian, C.; Öhlund, D.; Rickelt, S.; Lidström, T.; Huang, Y.; Hao, L.; Zhao, R.T.; Franklin, O.; Bhatia, S.N.; Tuveson, D.A.; et al. Cancer Cell–Derived Matrisome Proteins Promote Metastasis in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Cancer Research 2020, 80, 1461–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, A.D.; Nazari, S.S.; Yamada, K.M. Cell-extracellular matrix dynamics. Phys Biol 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyas, M.; Demehri, S. The extracellular matrix and immunity: breaking the old barrier in cancer. Trends in Immunology 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Wu, B.; Chiang, H.C.; Deng, H.; Zhang, X.; Xiong, W.; Liu, J.; Rozeboom, A.M.; Harris, B.T.; Blommaert, E.; et al. Tumour DDR1 promotes collagen fibre alignment to instigate immune exclusion. Nature 2021, 599, 673–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakravarthy, A.; Khan, L.; Bensler, N.P.; Bose, P.; De Carvalho, D.D. TGF-β-associated extracellular matrix genes link cancer-associated fibroblasts to immune evasion and immunotherapy failure. Nature communications 2018, 9, 4692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, C.; Sebastian, A.; Hinckley, A.; Rios-Arce, N.D.; Hynes, W.F.; Edwards, S.A.; He, W.; Hum, N.R.; Wheeler, E.K.; Loots, G.G. Extracellular matrix modulates T cell clearance of malignant cells in vitro. Biomaterials 2022, 282, 121378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorsson, V.; Gibbs, D.L.; Brown, S.D.; Wolf, D.; Bortone, D.S.; Yang, T.-H.O.; Porta-Pardo, E.; Gao, G.F.; Plaisier, C.L.; Eddy, J.A. The immune landscape of cancer. Immunity 2018, 48, 812–830.e814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, T.E.; Dyer, D.P.; Allen, J.E. The extracellular matrix and the immune system: A mutually dependent relationship. Science 2023, 379, eabp8964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwager, S.C.; Taufalele, P.V.; Reinhart-King, C.A. Cell-Cell Mechanical Communication in Cancer. 2019, 12, 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Almagro, J.; Messal, H.A. Volume imaging to interrogate cancer cell-tumor microenvironment interactions in space and time. Frontiers in Immunology 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishida-Aoki, N.; Gujral, T.S. Emerging approaches to study cell-cell interactions in tumor microenvironment. Oncotarget 2019, 10, 785–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrimon, N.; Pitsouli, C.; Shilo, B.Z. Signaling mechanisms controlling cell fate and embryonic patterning. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2012, 4, a005975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alekseenko, I.V.; Chernov, I.P.; Kostrov, S.V.; Sverdlov, E.D. Are Synapse-Like Structures a Possible Way for Crosstalk of Cancer with Its Microenvironment? Cancers (Basel) 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sverdlov, E. Missed Druggable Cancer Hallmark: Cancer-Stroma Symbiotic Crosstalk as Paradigm and Hypothesis for Cancer Therapy. Bioessays 2018, 40, e1800079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattes, B.; Scholpp, S. Emerging role of contact-mediated cell communication in tissue development and diseases. Histochem Cell Biol 2018, 150, 431–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, S.F. “Juxtacrine Signaling” In Developmental biology 6ed.; (ed.), N.b., Ed.; Sunderland, Mass.: Sinauer Assoc.: 2000.

- Oliveira, M.C.; Verswyvel, H.; Smits, E.; Cordeiro, R.M.; Bogaerts, A.; Lin, A. The pro- and anti-tumoral properties of gap junctions in cancer and their role in therapeutic strategies. Redox Biol 2022, 57, 102503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzo, L.; Gousset, K.; Zurzolo, C. Multifaceted roles of tunneling nanotubes in intercellular communication. Front Physiol 2012, 3, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abounit, S.; Zurzolo, C. Wiring through tunneling nanotubes--from electrical signals to organelle transfer. J Cell Sci 2012, 125, 1089–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casas-Tintó, S.; Portela, M. Cytonemes, Their Formation, Regulation, and Roles in Signaling and Communication in Tumorigenesis. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roehlecke, C.; Schmidt, M.H.H. Tunneling Nanotubes and Tumor Microtubes in Cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, E.T.; Daly, C.A.; Zhang, Y.; Dillard, M.E.; Ogden, S.K. Fixation of Embryonic Mouse Tissue for Cytoneme Analysis. JoVE (Journal of Visualized Experiments) 2022, e64100. [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, Y.M.; Inaba, M.; Buszczak, M. Specialized Intercellular Communications via Cytonemes and Nanotubes. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 2018, 34, 59–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allegra, A.; Di Gioacchino, M.; Cancemi, G.; Casciaro, M.; Petrarca, C.; Musolino, C.; Gangemi, S. Specialized Intercellular Communications via Tunnelling Nanotubes in Acute and Chronic Leukemia. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eugenin, E.A. Role of cell-to-cell communication in cancer: New features, insights, and directions. 2019, 2, e1228. [CrossRef]

- Sato, A.; Rahman, N.I.A.; Shimizu, A.; Ogita, H. Cell-to-cell contact-mediated regulation of tumor behavior in the tumor microenvironment. Cancer science 2021, 112, 4005–4012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominiak, A.; Chelstowska, B.; Olejarz, W.; Nowicka, G. Communication in the Cancer Microenvironment as a Target for Therapeutic Interventions. Cancers (Basel) 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ljubojevic, N.; Henderson, J.M.; Zurzolo, C. The Ways of Actin: Why Tunneling Nanotubes Are Unique Cell Protrusions. Trends Cell Biol 2021, 31, 130–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, G.; Brou, C.; Zurzolo, C. Tunneling Nanotubes: The Fuel of Tumor Progression? Trends Cancer 2020, 6, 874–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaccard, C.R.; Rinaldo, C.R.; Mailliard, R.B. Linked in: immunologic membrane nanotube networks. J Leukoc Biol 2016, 100, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, C.; Shi, Y.; You, J. Immune Cell Connection by Tunneling Nanotubes: The Impact of Intercellular Cross-Talk on the Immune Response and Its Therapeutic Applications. Mol Pharm 2021, 18, 772–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Sun, Y.; Qi, Z.; Cao, L.; Ding, S. Mitochondrial transfer/transplantation: an emerging therapeutic approach for multiple diseases. Cell Biosci 2022, 12, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driscoll, J.; Gondaliya, P.; Patel, T. Tunneling Nanotube-Mediated Communication: A Mechanism of Intercellular Nucleic Acid Transfer. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCoy-Simandle, K.; Hanna, S.J.; Cox, D. Exosomes and nanotubes: Control of immune cell communication. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2016, 71, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurzolo, C. Tunneling nanotubes: Reshaping connectivity. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2021, 71, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, F.; Bénard, M.; Jean-Jacques, B.; Schapman, D.; Roberge, H.; Lebon, A.; Goux, D.; Monterroso, B.; Elie, N.; Komuro, H.; et al. Investigating Tunneling Nanotubes in Cancer Cells: Guidelines for Structural and Functional Studies through Cell Imaging. Biomed Res Int 2020, 2020, 2701345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sontheimer, H. Tumour cells on neighbourhood watch. Nature 2015, 528, 49–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yu, X.; Ye, J.; Li, H.; Hu, J.; Tan, Y.; Fang, Y.; Akbay, E.; Yu, F.; Weng, C.; et al. Systematic investigation of mitochondrial transfer between cancer cells and T cells at single-cell resolution. Cancer Cell 2023, 41, 1788–1802 e1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Öhlund, D.; Handly-Santana, A.; Biffi, G.; Elyada, E.; Almeida, A.S.; Ponz-Sarvise, M.; Corbo, V.; Oni, T.E.; Hearn, S.A.; Lee, E.J. Distinct populations of inflammatory fibroblasts and myofibroblasts in pancreatic cancer. Journal of Experimental Medicine 2017, 214, 579–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sperb, N.; Tsesmelis, M.; Wirth, T. Crosstalk between tumor and stromal cells in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. International journal of molecular sciences 2020, 21, 5486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahu, P.; Jena, S.R.; Samanta, L. Tunneling Nanotubes: A Versatile Target for Cancer Therapy. Curr Cancer Drug Targets 2018, 18, 514–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauveau, A.; Aucher, A.; Eissmann, P.; Vivier, E.; Davis, D.M. Membrane nanotubes facilitate long-distance interactions between natural killer cells and target cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010, 107, 5545–5550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jash, E.; Prasad, P.; Kumar, N.; Sharma, T.; Goldman, A.; Sehrawat, S. Perspective on nanochannels as cellular mediators in different disease conditions. Cell Communication and Signaling 2018, 16, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linares, J.; Marin-Jimenez, J.A.; Badia-Ramentol, J.; Calon, A. Determinants and Functions of CAFs Secretome During Cancer Progression and Therapy. Front Cell Dev Biol 2020, 8, 621070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Luo, Y.; Mao, N.; Huang, G.; Teng, C.; Wang, H.; Wu, J.; Liao, X.; Yang, J. Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts Accelerate Malignant Progression of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer via Connexin 43-Formed Unidirectional Gap Junctional Intercellular Communication. Cell Physiol Biochem 2018, 51, 315–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aasen, T.; Leithe, E.; Graham, S.V.; Kameritsch, P.; Mayán, M.D.; Mesnil, M.; Pogoda, K.; Tabernero, A. Connexins in cancer: bridging the gap to the clinic. Oncogene 2019, 38, 4429–4451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aasen, T.; Mesnil, M.; Naus, C.C.; Lampe, P.D.; Laird, D.W. Gap junctions and cancer: communicating for 50 years. Nat Rev Cancer 2016, 16, 775–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finetti, F.; Cassioli, C.; Baldari, C.T. Transcellular communication at the immunological synapse: a vesicular traffic-mediated mutual exchange. F1000Res 2017, 6, 1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belardi, B.; Son, S.; Felce, J.H.; Dustin, M.L.; Fletcher, D.A. Cell-cell interfaces as specialized compartments directing cell function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2020, 21, 750–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolotto, C.; Rosillo, J.C.; Botti, B.; Fernández, A.S. “Synapse-like” Connections between Adipocytes and Stem Cells: Morphological and Molecular Features of Human Adipose Tissue. J Stem Cell Dev Biol 2018, 1, 100003. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Parajo, M.F.; Cambi, A.; Torreno-Pina, J.A.; Thompson, N.; Jacobson, K. Nanoclustering as a dominant feature of plasma membrane organization. J Cell Sci 2014, 127, 4995–5005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, G.J. Signal initiation in biological systems: the properties and detection of transient extracellular protein interactions. Molecular bioSystems 2009, 5, 1405–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.K.; Tonelli, F.M.; Silva, D.A.; Gomes, K.N.; Ladeira, L.O.; Resende, R.R. The role of cell adhesion, cell junctions, and extracellular matrix in development and carcinogenesis. Trends in Stem Cell Proliferation and Cancer Research 2013, 13–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalluri, R.; LeBleu, V.S. The biology, function, and biomedical applications of exosomes. 2020, 367. [CrossRef]

- Naito, Y.; Yoshioka, Y.; Ochiya, T. Intercellular crosstalk between cancer cells and cancer-associated fibroblasts via extracellular vesicles. Cancer Cell Int 2022, 22, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.J.; Wang, C. A review of the regulatory mechanisms of extracellular vesicles-mediated intercellular communication. Cell Commun Signal 2023, 21, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valadi, H.; Ekström, K.; Bossios, A.; Sjöstrand, M.; Lee, J.J.; Lötvall, J.O. Exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and microRNAs is a novel mechanism of genetic exchange between cells. Nature Cell Biology 2007, 9, 654–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Margolis, L.; Sadovsky, Y. The biology of extracellular vesicles: The known unknowns. PLoS Biol 2019, 17, e3000363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somiya, M. Where does the cargo go?: Solutions to provide experimental support for the “extracellular vesicle cargo transfer hypothesis”. Journal of Cell Communication and Signaling 2020, 14, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Monte, U. Does the cell number 109 still really fit one gram of tumor tissue? Cell Cycle 2009, 8, 505–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wang, G.; Abhange, K.; Xue, F.; Quinn, Z.; Mao, W.; Wan, Y. Factors influencing the measurement of the secretion rate of extracellular vesicles. Analyst 2020, 145, 5870–5877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auber, M.; Svenningsen, P. An estimate of extracellular vesicle secretion rates of human blood cells. Journal of Extracellular Biology 2022, 1, e46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Sanchez, R.; Churruca-Schuind, A.; Martinez-Ival, M.; Salazar, E.P. Cancer-associated Fibroblasts Communicate with Breast Tumor Cells Through Extracellular Vesicles in Tumor Development. Technol Cancer Res Treat 2022, 21, 15330338221131647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sverdlov, E.D. Amedeo Avogadro’s cry: what is 1 microg of exosomes? Bioessays 2012, 34, 873–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piffoux, M.; Volatron, J.; Silva, A.K.A.; Gazeau, F. Thinking Quantitatively of RNA-Based Information Transfer via Extracellular Vesicles: Lessons to Learn for the Design of RNA-Loaded EVs. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Jong, O.G.; Murphy, D.E.; Mäger, I.; Willms, E.; Garcia-Guerra, A.; Gitz-Francois, J.J.; Lefferts, J.; Gupta, D.; Steenbeek, S.C.; van Rheenen, J.; et al. A CRISPR-Cas9-based reporter system for single-cell detection of extracellular vesicle-mediated functional transfer of RNA. Nature Communications 2020, 11, 1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inaba, M.; Ridwan, S.M.; Antel, M. Removal of cellular protrusions. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2022, 129, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, Q.; Wang, A.; Yuan, Y.; Zhu, B.; Long, H. Heterogeneity of the tumor immune microenvironment and its clinical relevance. Exp Hematol Oncol 2022, 11, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mezheyeuski, A.; Micke, P. The Immune Landscape of Colorectal Cancer. 2021, 13. [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Sakakibara, R.; Honda, T.; Kirimura, S.; Daroonpan, P.; Kobayashi, M.; Ando, K.; Ujiie, H.; Kato, T.; Kaga, K.; et al. High density and proximity of CD8(+) T cells to tumor cells are correlated with better response to nivolumab treatment in metastatic pleural mesothelioma. Thorac Cancer 2023, 14, 1991–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon-Weeks, A.; Yuzhalin, A.E. Cancer Extracellular Matrix Proteins Regulate Tumour Immunity. Cancers 2020, 12, 3331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayashi, K.; Nogawa, D.; Kobayashi, M.; Asakawa, A.; Ohata, Y.; Kitagawa, S.; Kubota, K.; Takahashi, H.; Yamada, M.; Oda, G.; et al. Quantitative high-throughput analysis of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes in breast cancer. Front Oncol 2022, 12, 901591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finotello, F.; Eduati, F. Multi-Omics Profiling of the Tumor Microenvironment: Paving the Way to Precision Immuno-Oncology. Front Oncol 2018, 8, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minini, M.; Fouassier, L. Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts and Extracellular Matrix: Therapeutical Strategies for Modulating the Cholangiocarcinoma Microenvironment. Current Oncology 2023, 30, 4185–4196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aden, D.; Zaheer, S.; Ahluwalia, H.; Ranga, S. Cancer-associated fibroblasts: Is it a key to an intricate lock of tumorigenesis? Cell Biology International 2023, 47, 859–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, M.; Nguyen, T.; Gundre, E.; Ogunlusi, O.; El-Sobky, M.; Giri, B.; Sarkar, T.R. Cancer-associated fibroblasts: The chief architect in the tumor microenvironment. Front Cell Dev Biol 2023, 11, 1089068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goenka, A.; Khan, F.; Verma, B.; Sinha, P.; Dmello, C.C.; Jogalekar, M.P.; Gangadaran, P.; Ahn, B.-C. Tumor microenvironment signaling and therapeutics in cancer progression. Cancer Communications 2023, 43, 525–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, K.; Ly, T.; Kriet, M.; Czirok, A.; Thomas, S.M. Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts: Master Tumor Microenvironment Modifiers. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamaguchi, H.; Sakai, R. Direct Interaction between Carcinoma Cells and Cancer Associated Fibroblasts for the Regulation of Cancer Invasion. Cancers (Basel) 2015, 7, 2054–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asif, P.J.; Longobardi, C.; Hahne, M.; Medema, J.P. The Role of Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts in Cancer Invasion and Metastasis. Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezheyeuski, A.; Bergsland, C.H.; Backman, M.; Djureinovic, D.; Sjöblom, T.; Bruun, J.; Micke, P. Multispectral imaging for quantitative and compartment-specific immune infiltrates reveals distinct immune profiles that classify lung cancer patients. The Journal of pathology 2018, 244, 421–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gide, T.N.; Silva, I.P.; Quek, C.; Ahmed, T.; Menzies, A.M.; Carlino, M.S.; Saw, R.P.; Thompson, J.F.; Batten, M.; Long, G.V. Close proximity of immune and tumor cells underlies response to anti-PD-1 based therapies in metastatic melanoma patients. Oncoimmunology 2020, 9, 1659093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feichtenbeiner, A.; Haas, M.; Büttner, M.; Grabenbauer, G.G.; Fietkau, R.; Distel, L.V. Critical role of spatial interaction between CD8+ and Foxp3+ cells in human gastric cancer: the distance matters. Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy 2014, 63, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marusyk, A.; Tabassum, D.P.; Janiszewska, M.; Place, A.E.; Trinh, A.; Rozhok, A.I.; Pyne, S.; Guerriero, J.L.; Shu, S.; Ekram, M.; et al. Spatial Proximity to Fibroblasts Impacts Molecular Features and Therapeutic Sensitivity of Breast Cancer Cells Influencing Clinical Outcomes. Cancer Res 2016, 76, 6495–6506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fletcher, A.L.; Turley, S.J. Who am I? (re-)Defining fibroblast identity and immunological function in the age of bioinformatics. Immunol Rev 2021, 302, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Qiu, Y.; Zhang, Y. Research Progress on Therapeutic Targeting of Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts to Tackle Treatment-Resistant NSCLC. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; Wang, H.; Li, C.; Fang, J.Y.; Xu, J. Cancer Cell-Intrinsic PD-1 and Implications in Combinatorial Immunotherapy. Front Immunol 2018, 9, 1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauken, K.E.; Torchia, J.A.; Chaudhri, A.; Sharpe, A.H.; Freeman, G.J. Emerging concepts in PD-1 checkpoint biology. Seminars in Immunology 2021, 52, 101480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Wu, J.; Mao, L.; Xu, H.; Wang, S. Revisiting PD-1/PD-L pathway in T and B cell response: Beyond immunosuppression. Cytokine & Growth Factor Reviews 2022, 67, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu-Monette, Z.Y.; Zhang, M.; Li, J.; Young, K.H. PD-1/PD-L1 Blockade: Have We Found the Key to Unleash the Antitumor Immune Response? Front Immunol 2017, 8, 1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, C.D.; Pulanco, M.C.; Cui, W.; Lu, L.; Zang, X. PD-L1 and B7-1 Cis-Interaction: New Mechanisms in Immune Checkpoints and Immunotherapies. Trends in molecular medicine 2021, 27, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, R.L.; Pure, E. Cancer-associated fibroblasts and their influence on tumor immunity and immunotherapy. Elife 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliani, A.; Fais, S. Proposal to Consider Chemical/Physical Microenvironment as a New Therapeutic Off-Target Approach. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sverdlov, E.D. Multidimensional Complexity of Cancer. Simple Solutions Are Needed. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2016, 81, 731–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, S.P.; Sharma, A.; Patil, V.M. Molecular Processes Exploited as Drug Targets for Cancer Chemotherapy. Anticancer Agents Med Chem 2021, 21, 1638–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Conforti, R.; Aymeric, L.; Locher, C.; Kepp, O.; Kroemer, G.; Zitvogel, L. How to improve the immunogenicity of chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Cancer Metastasis Rev 2011, 30, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomeroy, A.E.; Schmidt, E.V.; Sorger, P.K.; Palmer, A.C. Drug independence and the curability of cancer by combination chemotherapy. Trends Cancer 2022, 8, 915–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finetti, F.; Baldari, C.T. The immunological synapse as a pharmacological target. Pharmacol Res 2018, 134, 118–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, D.J.; Nelson, W.J. Secret handshakes: cell-cell interactions and cellular mimics. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2018, 50, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebnet, K.; Kummer, D.; Steinbacher, T.; Singh, A.; Nakayama, M.; Matis, M. Regulation of cell polarity by cell adhesion receptors. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2018, 81, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bausch-Fluck, D.; Milani, E.S.; Wollscheid, B. Surfaceome nanoscale organization and extracellular interaction networks. Curr Opin Chem Biol 2019, 48, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Wang, X. Opportunities and Challenges in Tunneling Nanotubes Research: How Far from Clinical Application? Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Q.; Huang, B.; Huang, Z.; Cai, J.; Gong, L.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, J.; Dong, W.; Wang, Z. Tumor cell-fibroblast heterotypic aggregates in malignant ascites of patients with ovarian cancer. Int J Mol Med 2019, 44, 2245–2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dustin, M.L.; Choudhuri, K. Signaling and Polarized Communication Across the T Cell Immunological Synapse. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 2016, 32, 303–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatherley, D.; Lea, S.M.; Johnson, S.; Barclay, A.N. Structures of CD200/CD200 receptor family and implications for topology, regulation, and evolution. Structure 2013, 21, 820–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padhan, K.; Varma, R. Immunological synapse: a multi-protein signalling cellular apparatus for controlling gene expression. Immunology 2010, 129, 322–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, P.A.; Carreno, L.J.; Cespedes, P.F.; Bueno, S.M.; Riedel, C.A.; Kalergis, A.M. Modulation of tumor immunity by soluble and membrane-bound molecules at the immunological synapse. Clin Dev Immunol 2013, 2013, 450291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, S.; Nelson, W.J. Synapses: sites of cell recognition, adhesion, and functional specification. Annu Rev Biochem 2007, 76, 267–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayliss, R.J.; Piguet, V. Masters of manipulation: Viral modulation of the immunological synapse. Cell Microbiol 2018, 20, e12944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dustin, M.L. Modular design of immunological synapses and kinapses. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2009, 1, a002873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dustin, M.L.; Baldari, C.T. The Immune Synapse: Past, Present, and Future. Methods Mol Biol 2017, 1584, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garber, K. Beyond ipilimumab: new approaches target the immunological synapse. J Natl Cancer Inst 2011, 103, 1079–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, I.A.; Boija, A.; Afeyan, L.K.; Hawken, S.W.; Fan, M.; Dall’Agnese, A.; Oksuz, O.; Henninger, J.E.; Shrinivas, K.; Sabari, B.R.; et al. Partitioning of cancer therapeutics in nuclear condensates. Science 2020, 368, 1386–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, M.; Hance, K.W.; Yadavilli, S.; Smothers, J.; Waight, J.D. Emergence of the CD226 Axis in Cancer Immunotherapy. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 914406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizoguchi, A.; Nakanishi, H.; Kimura, K.; Matsubara, K.; Ozaki-Kuroda, K.; Katata, T.; Honda, T.; Kiyohara, Y.; Heo, K.; Higashi, M.; et al. Nectin: an adhesion molecule involved in formation of synapses. J Cell Biol 2002, 156, 555–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermans, D.; Rodriguez-Mogeda, C.; Kemps, H.; Bronckaers, A.; de Vries, H.E.; Broux, B. Nectins and Nectin-like molecules drive vascular development and barrier function. Angiogenesis 2023, 26, 349–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ledford, H. Cancer trial results show power of weaponized antibodies. Nature 2023, 623, 231–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portsmouth, D.; Hlavaty, J.; Renner, M. Suicide genes for cancer therapy. Mol Aspects Med 2007, 28, 4–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alekseenko, I.V.; Snezhkov, E.V.; Chernov, I.P.; Pleshkan, V.V.; Potapov, V.K.; Sass, A.V.; Monastyrskaya, G.S.; Kopantzev, E.P.; Vinogradova, T.V.; Khramtsov, Y.V.; et al. Therapeutic properties of a vector carrying the HSV thymidine kinase and GM-CSF genes and delivered as a complex with a cationic copolymer. J Transl Med 2015, 13, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alekseenko, I.; Kuzmich, A.; Kondratyeva, L.; Kondratieva, S.; Pleshkan, V.; Sverdlov, E. Step-by-Step Immune Activation for Suicide Gene Therapy Reinforcement. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aznar, M.A.; Tinari, N.; Rullan, A.J.; Sanchez-Paulete, A.R.; Rodriguez-Ruiz, M.E.; Melero, I. Intratumoral Delivery of Immunotherapy-Act Locally, Think Globally. J Immunol 2017, 198, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melero, I.; Castanon, E.; Alvarez, M.; Champiat, S.; Marabelle, A. Intratumoural administration and tumour tissue targeting of cancer immunotherapies. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2021, 18, 558–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- First two CAR-T cell medicines recommended for approval in the European Unio. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/first-two-car-t-cell-medicines-recommended-approval-european-union (accessed on 24.11.2023).

- Andrews, M. Insurers And Government Are Slow To Cover Expensive CAR-T Cancer Therapy. Available online: https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2018/07/17/629543151/insurers-and-government-are-slow-to-cover-expensive-car-t-cancer-therapy (accessed on 24.11.2023).

- LifeSciencesIntelligence. The Top 5 Most Expensive FDA-Approved Gene Therapies. Available online: https://lifesciencesintelligence.com/features/the-top-5-most-expensive-fda-approved-gene-therapies (accessed on 12.11.2023).

- Ahmed, L.; Constantinidou, A.; Chatzittofis, A. Patients’ perspectives related to ethical issues and risks in precision medicine: a systematic review. Front Med (Lausanne) 2023, 10, 1215663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).