Submitted:

05 March 2024

Posted:

06 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Challenging Environments: Individualisation and Collaboration in Complex Scenarios

2.2. The Right to the City and Urban Complexity

2.3. Collective Creativity in Urban Spaces: Participation, Collaboration and Co-Creation

2.4. ‘Urban Laboratories’ and Temporary Use of the City

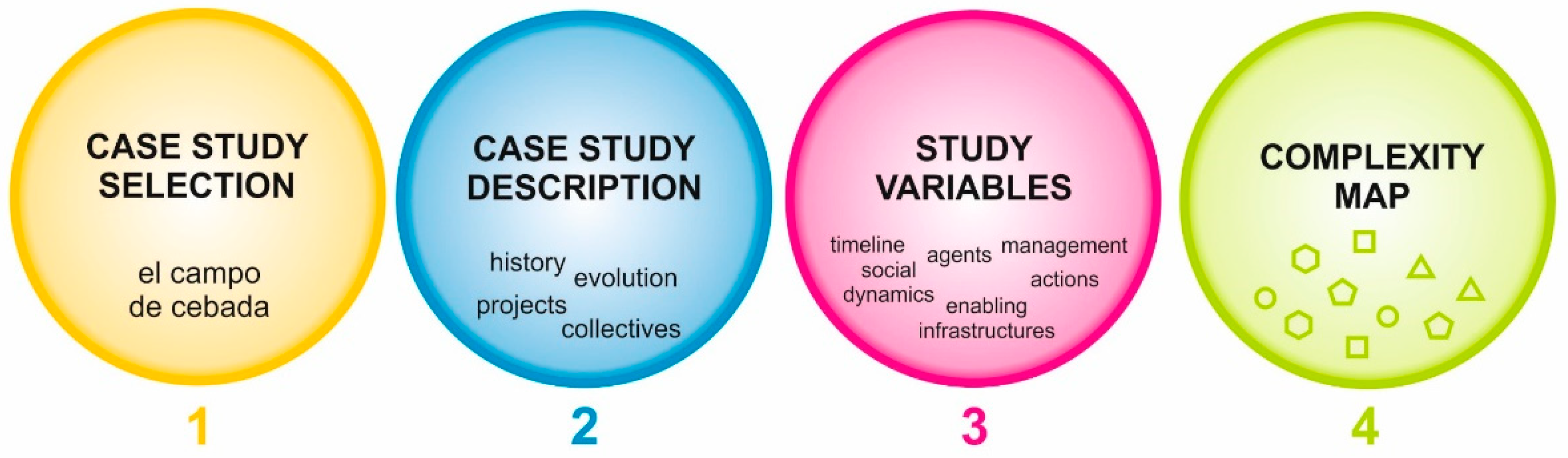

3. Methodology

3.1. Study Case Selection

3.2. Criteria for Case Selection

3.3. Analysis of the Case Study

3.4. Study Variables

3.5. Complexity Map

4. Results and Discussion

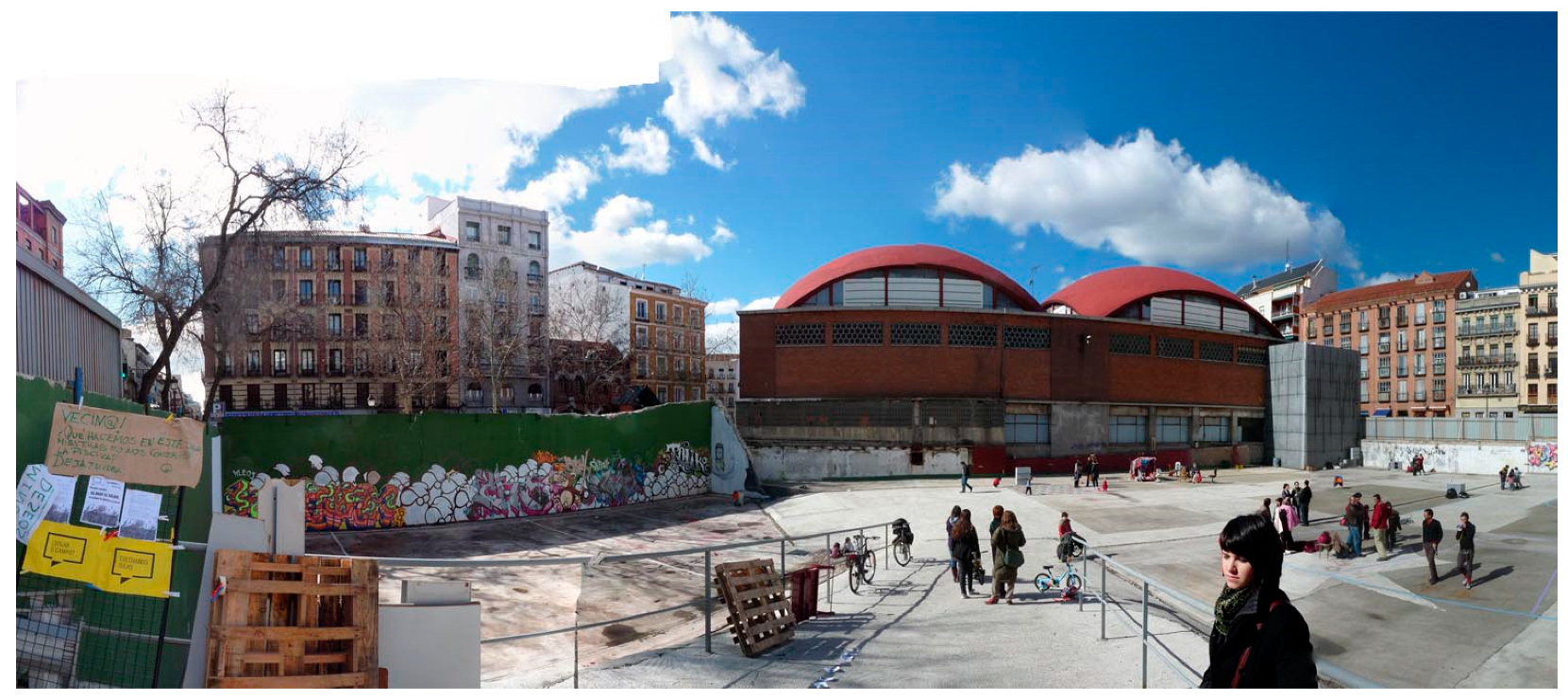

4.1. Description of the Study Case: ‘El Campo de Cebada’ as Complex ‘Urban Laboratory’

4.2. Research Variables: Measuring Elements of the Complexity of ‘El Campo de Cebada’

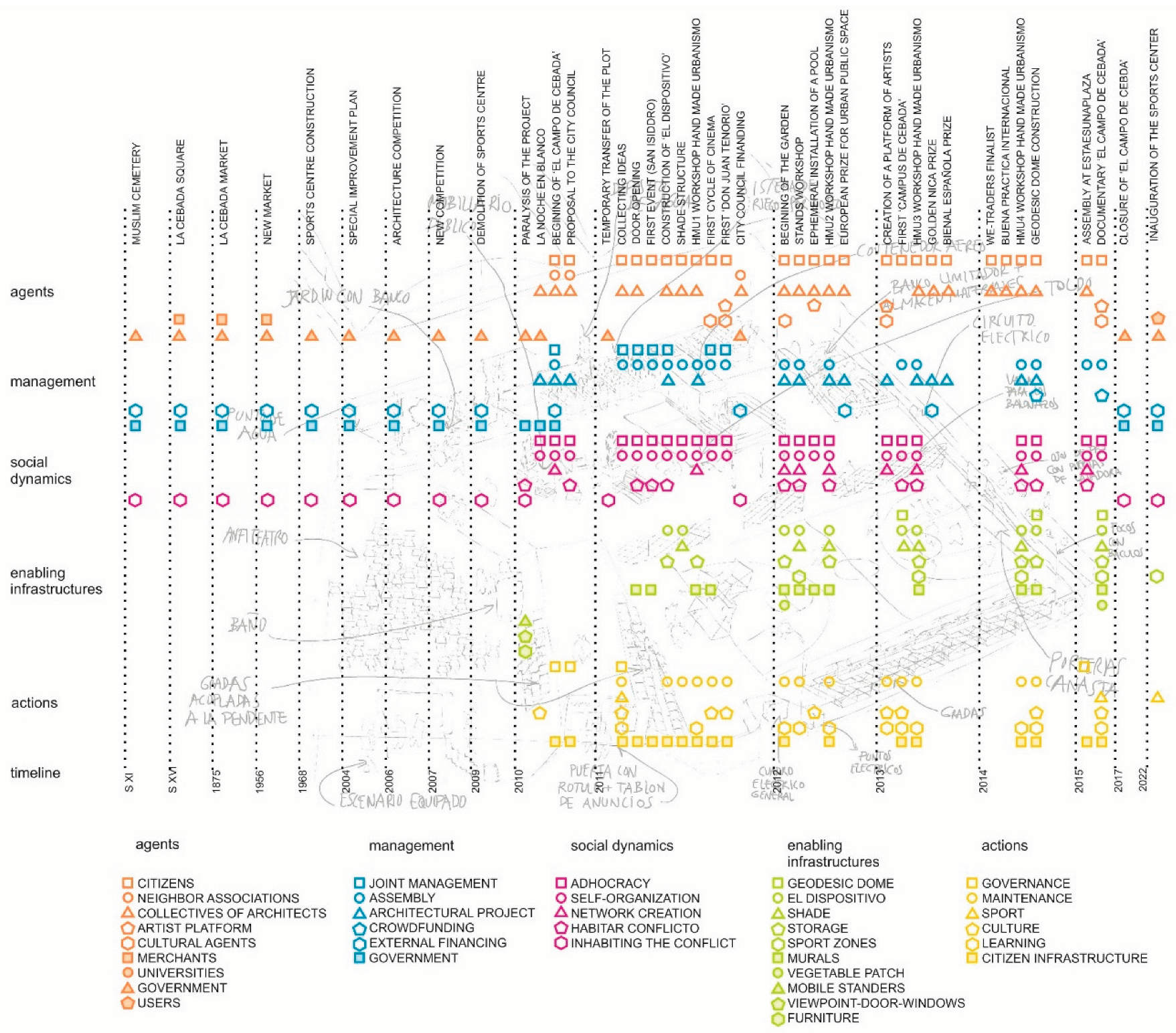

4.2.1. Timeline

4.2.2. Agents

4.2.3. Management

4.2.4. Social Dynamics

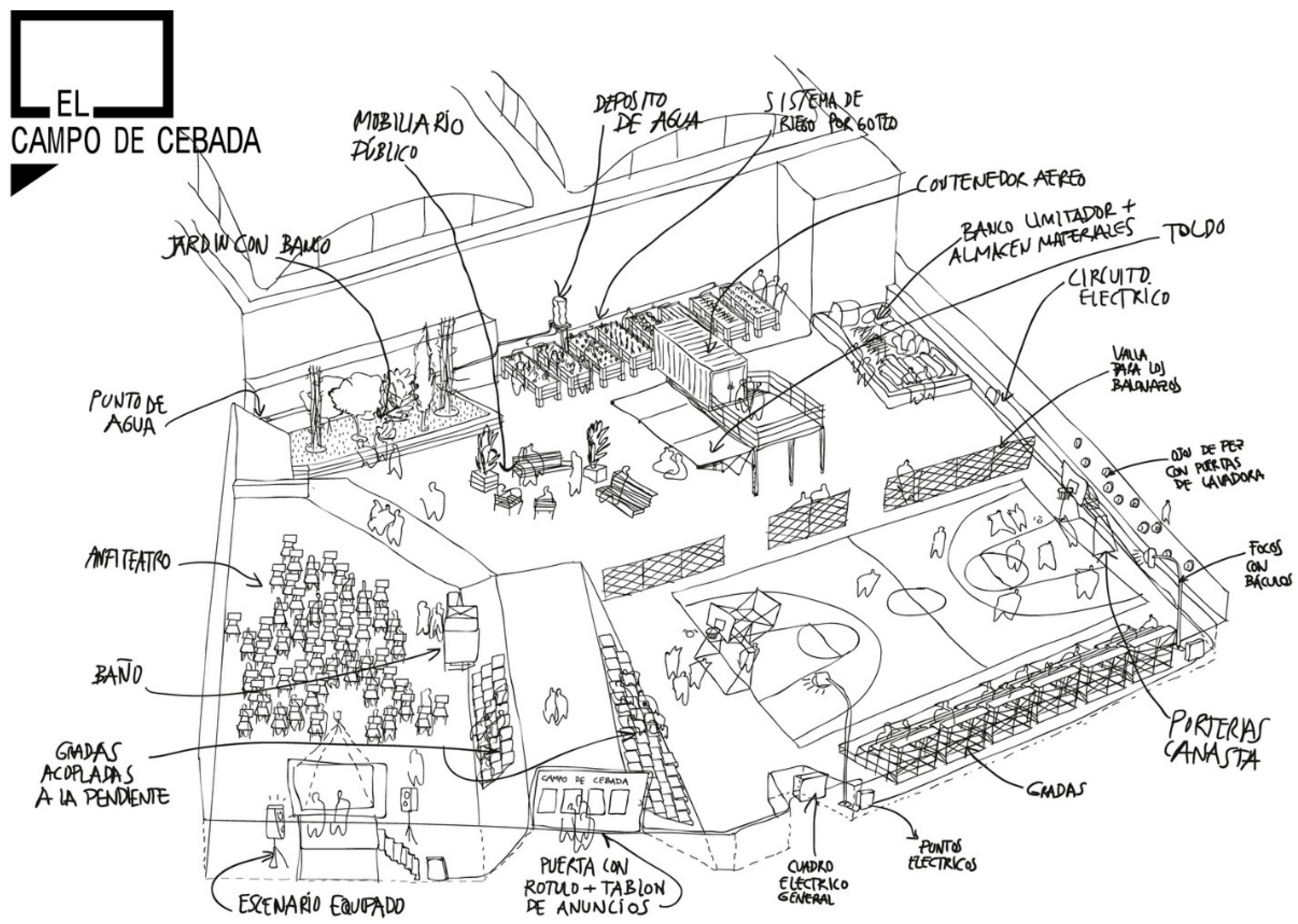

4.2.5. Enabling Infrastructures

4.2.6. Actions

4.3. Complexity Map of ‘El Campo de Cebada’

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cities—United Nations Sustainable Development Action 2015. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/cities/ (accessed on 20 December 2023).

- Harvey, D. The Right to the City. In The City Reader; Routledge: Seventh edition. | Abingdon, Oxon ; New York, NY : Routledge, 2020. | Series: Routledge urban reader series, 2008; pp. 23–40. ISBN 9780429261732.

- Purcell, M. Possible Worlds: Henri Lefebvre and the Right to the City. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/juaf.12034. 2016, 36, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, D. Rebel Cities: From the Right to the City to the Urban Revolution; Verso.; New York. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Garnier, J.-P. The Right to the City from Henri Lefebvre to David Harvey. Between Theories and Execution. Ciudades 2012, 15, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, H. La Révolution Urbaine; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Kennon, K. Does Collaboration Work? Architectural Design 2006, 76, 50–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawyer, R.K.; DeZutter, S. Distributed Creativity: How Collective Creations Emerge From Collaboration. Psychol Aesthet Creat Arts 2009, 3, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borkowski, A.; Branki, C.; Grabska, E.; Palacz, W. Towards Collaborative Creative Design. Autom Constr 2001, 10, 607–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, P.V.K.; Mosleh, W.S. Conflicts in Co-Design: Engaging with Tangible Artefacts in Multi-Stakeholder Collaboration. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2020.1740279 2021, 17, 473–492. [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, B.E. Collaborative Resilience: Moving Through Crisis to Opportunity; MIT Press, 2011. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Koutsikouri, D.; Austin, S.; Dainty, A. Critical Success Factors in Collaborative Multidisciplinary Design Projects. Journal of Engineering, Design and Technology 2008, 6, 198–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terrin, J.-J. Conception Collaborative Pour Innover En Architecture : Processus, Méthodes, Outils; L’Harmattan: Paris, 2009; ISBN 9782296075344. [Google Scholar]

- Karvonen, A.; van Heur, B. Urban Laboratories: Experiments in Reworking Cities. Int J Urban Reg Res 2014, 38, 379–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marvin, S.; Silver, J. The Urban Laboratory and Emerging Sites of Urban Experimentation. In The Experimental City; Taylor and Francis, 2016; pp. 47–60 ISBN 9781317517153.

- Rahmawan-Huizenga, S.; Ivanova, D. THE URBAN LAB: Imaginative Work in the City. Int J Urban Reg Res 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban Living Lab for Local Regeneration; Aernouts, N., Cognetti, F., Maranghi, E., Eds. The Urban Book Series; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2023; ISBN 978-3-031-19747-5.

- Scozzi, B.; Bellantuono, N.; Pontrandolfo, P. Managing Open Innovation in Urban Labs. Group Decis Negot 2017, 26, 857–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesti, G. Co-Production for Innovation: The Urban Living Lab Experience. Policy Soc 2018, 37, 310–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steen, K.; van Bueren, E. The Defining Characteristics of Urban Living Labs. Technology Innovation Management Review 2017, 7, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franz, Y. Designing Social Living Labs in Urban Research. Info 2015, 17, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevens, F.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Gorissen, L.; Loorbach, D. Urban Transition Labs: Co-Creating Transformative Action for Sustainable Cities. J Clean Prod 2013, 50, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puerari, E.; de Koning, J.I.J.C.; von Wirth, T.; Karré, P.M.; Mulder, I.J.; Loorbach, D.A. Co-Creation Dynamics in Urban Living Labs. Sustainability 2018, Vol. 10, Page 1893 2018, 10, 1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartagena, Y. Temporary Urbanism and Community Engagement: A Case Study of Piazza Scaravilli in Bologna. Advances in Science, Technology and Innovation 2022, 11–22.

- Bragaglia, F.; Caruso, N. Temporary Uses: A New Form of Inclusive Urban Regeneration or a Tool for Neoliberal Policy? https://doi.org/10.1080/17535069.2020.1775284 2020, 15, 194–214. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Conroy, M.M. Vacant Urban Land Temporary Use and Neighborhood Sustainability: A Comparative Study of Two Midwestern Cities. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352166.2023.2168551 2023, 1–25. [CrossRef]

- Ferreri, M. Occupying Vacant Spaces: Precarious Politics of Temporary Urban Reuse., 2013.

- Dubeaux, S.; Cunningham Sabot, E. Maximizing the Potential of Vacant Spaces within Shrinking Cities, a German Approach. Cities 2018, 75, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, S. Urban Complexity. In Machine Learning and the City; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., 2022; pp. 1–13.

- Massara Rocha, B. City and Complexity: Reflections on the Practice of Contemporary Design. Oculum Ensaios 2018, 15, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walloth, C.; Gurr, J.M.; Schmidt, J.A. Understanding Complex Urban Systems : Multidisciplinary Approaches to Modeling; Springer, 2012; ISBN 3-319-02995-9.

- Mosleh, W.S.; Larsen, H. Exploring the Complexity of Participation. CoDesign 2020, 17, 454–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J. Complexity Science in Collaborative Design. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710880500478346 2006, 1, 223–242. [CrossRef]

- Powers, A. Townscape as a Model of Organised Complexity. 2012, 37–41. [CrossRef]

- Portugali, J. Complexity Theories of Cities: Achievements, Criticism and Potentials. In Complexity Theories of Cities Have Come of Age; Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2012; pp. 47–62.

- Roo, G. de. ; Hillier, Jean.; Wezemael, J. van. Complexity and Planning : Systems, Assemblages and Simulations; Ashgate.; Routledge, 2016; ISBN 1-315-57319-9. [Google Scholar]

- Moroni, S.; Rauws, W.; Cozzolino, S. Forms of Self-Organization: Urban Complexity and Planning Implications. https://doi.org/10.1177/2399808319857721 2019, 47, 220–234. [CrossRef]

- Moroni, S. Complexity and the Inherent Limits of Explanation and Prediction: Urban Codes for Self-Organising Cities. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1473095214521104 2014, 14, 248–267. [CrossRef]

- Sanders, E.B.N.; Stappers, P.J. Probes, Toolkits and Prototypes: Three Approaches to Making in Codesigning. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2014.888183 2014, 10, 5–14. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chen, R. (Irene) An Experimental Study on Collaborative Effectiveness of Augmented Reality Potentials in Urban Design. Codesign-International Journal of Cocreation in Design and the Arts 2009, 5, 229–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baibarac, C.; Petrescu, D. Co-Design and Urban Resilience: Visioning Tools for Commoning Resilience Practices. CoDesign 2017, 15, 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyerlein, S.T.; Beyerlein, M.M.; Kennedy, F.H. Innovation through Collaboration; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bradford England, 2009; Vol. 12; ISBN 184950430X :Đ62.95; 9781849504300 :Đ62.95; 1572-0977.

- Bjone, C. Art and Architecture :Strategies in Collaboration; Birkhaeuser Verlag: Boston, MA, 2009; ISBN 9783764399436. [Google Scholar]

- Fernie, J. Two Minds :Artists and Architects in Collaboration; Black Dog: London, 2006; ISBN 1904772269. [Google Scholar]

- Miell, D.; Littleton, K. Collaborative Creativity :Contemporary Perspectives; Free Association Books: London, 2004; ISBN 1853437638. [Google Scholar]

- Gloor, P.A. Swarm Creativity :Competitive Advantage through Collaborative Innovation Networks; Oxford University Press: Oxford; New York, 2006; ISBN 9780195304121; 0195304128.

- Benjamin, W. Angelus Novus; Edhasa: Barcelona, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, U.; Beck-Gernsheim, E. Individualization: Institutionalized Individualism and Its Social and Political Consequences; Sage Publications Limited: London, 2002; Vol. 13. [Google Scholar]

- Kropotkin, P.A. Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution; Heinemann: Londres, 1902. [Google Scholar]

- Ball, P. Critical Mass: How One Things Leads Into Another; Random: London, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hardt, Michael. ; Negri, A. Multitude: War and Democracy in the Age of Empire; Penguin Press: New York, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lévy, P. L’intelligence Collective: Pour Une Anthropologie Du Cyberspace; La Découverte Paris, 1994.

- Lévy, P. Cyberculture; U of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, 2001; Vol. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Léfebvre, H. Le Droit À La Ville. Anthropos 1968.

- Johnson, S. Emergence: The Connected Lives of Ants, Brains, Cities and Software.; Allen Lane: New York, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, J. The Death and Life of Great American Cities; Vintage Books, 1961; Vol. V–241;

- Healey, P. On Creating the “City” as a Collective Resource. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0042098022000002957 2002, 39, 1777–1792. [CrossRef]

- Ermacora, T.; Bullivant, L. Recoded City: Co-Creating Urban Futures; Taylor and Francis, 2016; ISBN 9781317591429.

- Bratteteig, T.; Wagner, I. Spaces for Participatory Creativity. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2012.672576 2012, 8, 105–126. [CrossRef]

- Sanders, E.B.-N.; Stappers, P.J. Co-Creation and the New Landscapes of Design. Co-design 2008, 799–809. [CrossRef]

- Franqueira, T. Creative Places for Collaborative Cities: Proposal for the ‘Progetto Habitat e Cultura’ in Milan. http://dx.doi.org/10.2752/175470710X12735884220934 2015, 13, 199–216. [CrossRef]

- Amin, A. Collective Culture and Urban Public Space. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604810801933495 2008, 12, 5–24. [CrossRef]

- Sara, R.; Jones, M.; Rice, L. Austerity Urbanism: Connecting Strategies and Tactics for Participatory Placemaking. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2020.1761985 2020. [CrossRef]

- Estalella, A. Colectivos de Arquitectura: Otra Sensibilidad Urbana. Available online: http://www.prototyping.es/destacado/colectivos-de-arquitectura-otra-sensibilidad-urbana.

- Transversal, P. Friendly Madrid. El Mapa Ante El Cambio de Paradigma Arquitectónico. Pasajes de arquitectura y crítica, 2013; 39. [Google Scholar]

- Wachter, S. Governing with Urban Labs. In Urban Living Lab for Local Regeneration; 2023; pp. 39–52.

- Coenen, T.; Robijt, S. Heading for a FALL: A Framework for Agile Living Lab Projects. Technology Innovation Management Review 2017, 7, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haukipuro, L.; Väinämö, S.; Hyrkäs, P. Innovation Instruments to Co-Create Needs-Based Solutions in a Living Lab. Technology Innovation Management Review 2018, 8, 22–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kareborn, B.B.; Stahlbrost, A. Living Lab: An Open and Citizen-Centric Approach for Innovation. International Journal of Innovation and Regional Development 2009, 1, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Network of Living Labs (ENoLL). Available online: https://enoll.org/about-us/ (accessed on 15 September 2022).

- Bajgier, S.M.; Maragah, H.D.; Saccucci, M.S.; Verzilli, A.; Prybutok, V.R. Introducing Students to Community Operations Research by Using a City Neighborhood As A Living Laboratory. https://doi.org/10.1287/opre.39.5.701 1991, 39, 701–709. https://doi.org/10.1287/OPRE.39.5.701. [CrossRef]

- Scholl, C.; De Kraker, J.; Hoeflehner, T.; Eriksen, M.A.; Wlasak, P.; Drage, T. Transitioning Urban Experiments: Reflections on Doing Action Research with Urban Labs. GAIA 2018, 27, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, J.; Lu, H.; Chirkin, A.; Klein, B.; Schmitt, G. Citizen Design Science: A Strategy for Crowd-Creative Urban Design. Cities 2018, 72, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialski, P.; Derwanz, H.; Otto, B. ; Vollme, rHans Saving the City: Collective Low-budget Organizing and Urban Practice. Ephemera Journal 2015, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Sharifi, A.; Reza Khavarian-Garmsir, A.; Mela, A.; Tousi, E.; Melas, E.; Varelidis, G. Spatial Distribution and Quality of Urban Public Spaces in the Attica Region (Greece) during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Survey-Based Analysis. Urban Science 2024, Vol. 8, Page 2 2023, 8, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterman, R.H. Adhocracy: The Power to Change; Norton: New York, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Sanz de Haro, J. Ciudad Cebada: Un Artículo Sobre El Campo de La Cebada de Madrid, o La Ciudad Que Quizás Nos Espera. Available online: http://activistark.blogspot.com.es/2015/01/ciudad-cebada-un-articulo-sobre-el.html.

- Basurama Manifiesto Abierto Por Los Espacios Urbanos de Madrid. Available online: http://www.laciudadviva.org/blogs/?p=27961.

- Transversal, P. Escuchar y Transformar La Ciudad : Urbanismo Colaborativo y Participación Ciudadana; Madrid, 2018.

- Volont, L. DIY Urbanism and the Lens of the Commons: Observations from Spain: City Community 2019, 18, 257–279. 18. [CrossRef]

- Iveson, K. Cities within the City: Do-It-Yourself Urbanism and the Right to the City. Int J Urban Reg Res 2013, 37, 941–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanza, V.; Tilio, L.; Azzato, A.; Las Casas, G.B.; Pontrandolfi, P. From Urban Labs in the City to Urban Labs on the Web. Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics) 2012, 7334 LNCS, 686–698.

- Della Lucia, M. Creative Cities: Urban Experimental Labs. International Journal of Management Cases 2015, 17, 156–172. [Google Scholar]

- Rice, L. Occupied Space. Architectural Design 2013, 83, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonick, S. Indignation and Inclusion: Activism, Difference, and Emergent Urban Politics in Postcrash Madrid. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0263775815608852 2015, 34, 209–226. [CrossRef]

- Madanipour, A. Temporary Use of Space: Urban Processes between Flexibility, Opportunity and Precarity. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098017705546 2017, 55, 1093–1110. [CrossRef]

- Quentin, S. Temporary Uses of Urban Spaces: How Are They Understood as ‘Creative’? International Journal of Architectural Research 2018, 12, 90–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez Nieto, A. Emerging Systems for Urban Regeneration and Production of Public Space. Ciudades 2017, 179–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, P.; Williams, L. The Temporary City; Williams, L., Ed.; Routledge: London ;, 2012; ISBN 9780415670555.

- Feinberg, M.I. Don Juan Tenorio in the Campo de Cebada: Restaging Urban Space after 15-M. Journal of Spanish Cultural Studies 2014, 15, 143–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, I. El Campo de Cebada. Available online: http://elasuntourbano.mx/elcampodecebada/.

- Di Giovanni, A. Urban Voids as a Resource for the Design of Contemporary Public Spaces. Planum. The Journal of Urbanism 2019, 2, 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- n’UNDO Evolución Del Espacio Público de La Plaza de La Cebada…. Available online: https://mercadodelacebada.wordpress.com/2012/02/07/evolucion-del-espacio-publico-de-la-plaza-de-la-cebada/.

- Angulo Delgado, M.T. Arte, Participación y Comunidad: “El Campo de Cebada” Como Ejercicio de Intervención Crítica En El Espacio Público, 2019.

- Plan Especial Del Área de Planeamiento Específico 01.07/M ‘Plaza de La Cebada-Carrera de San Francisco’—Portal de Transparencia Del Ayuntamiento de Madrid. Available online: https://transparencia.madrid.es/portales/transparencia/es/Transparencia-por-sectores/Urbanismo/Planeamiento-urbanistico/Plan-Especial-del-Area-de-Planeamiento-Especifico-01-07-M-Plaza-de-la-Cebada-Carrera-de-San-Francisco/?vgnextfmt=default&vgnextoid=4556 (accessed on 18 February 2021).

- Avia Estrada, M. La Cebada No Tiene Una Identidad. Available online: https://espaciosilentes.wordpress.com/2015/04/29/el-campo-de-cebada-jacobo-garcia-fouz/.

- Lozano-Bright, C. El Campo de Cebada y Otros Laboratorios Urbanos. In; Clud de Debates Urbanos: Madrid, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous El Campo de Cebada: Gestión Vecinal de La Plaza de La Cebada,Madrid. Arquitectura Viva 2012, 52–55.

- EXYZT; Römer, A.; Basurama City Island. Available online: https://old.constructlab.net/projects/city-island/ (accessed on 29 December 2023).

- Rodríguez-Pina, G.; Bracero, A. Campo de Cebada, Manual de Montaje de Una Plaza Hecha a Mano Por y Para Los Vecinos. El Huffingtonpost 2015.

- Gutiérrez, B. The Open Source City as the Transnational Democratic Future. In State of power; 2016; pp. 164–181.

- Kolesnikov, D. El Campo de Cebada. Design as Politics 2013, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Morin, E. Introduction à La Pensée Complexe; ESPF: París, 1990; Vol. 1a. [Google Scholar]

- Terreros, J.M.S. de los Welcoming Sound: The Case of a Noise Complaint in the Weekly Assembly of El Campo de Cebada. Soc Mov Stud 2018, 17, 269–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoll, M. Winners Prix Ars Electronica 2013. Available online: http://www.aec.at/aeblog/en/2013/05/16/gewinnerinnen-prix-ars-electronica-2013/.

- Corsín Jiménez, A. The Right to Infrastructure: A Prototype for Open Source Urbanism. Environ Plan D 2014, 32, 342–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basurama Sobre Nuestra Capacidad de Imaginación Política Para El Espacio Público. Available online: http://basurama.org/txt/sobre-nuestra-capacidad-de-imaginacion-politica-para-el-espacio-publico/.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).