1. Introduction

With increased energy use and environmental damage, the search for alternative and green energy has become a top issue [

1]. Furthermore, the greenhouse effect, along with a scarcity of non-renewable fossil fuel energy, raises the need for cleaner and more effective energy conversion technologies [

2].Global energy issues and pollution pose a huge threat to human survival and prosperity [

3]. Electrochemical storage and energy conversion technologies have transformed the energy industry and impacted the lives of billions [

4]. The progress of materials is essential in accelerating electrochemical processes and facilitating the innovation of revolutionary technologies, spanning from batteries and capacitors to fuel cells and electrolyzers [

5]. Fuel cells have received a lot of interest among the various devices produced due to their independence from fossil energy as well as high theoretical energy and power densities. These advantages are particularly advantageous in resolving the energy and environmental issues [

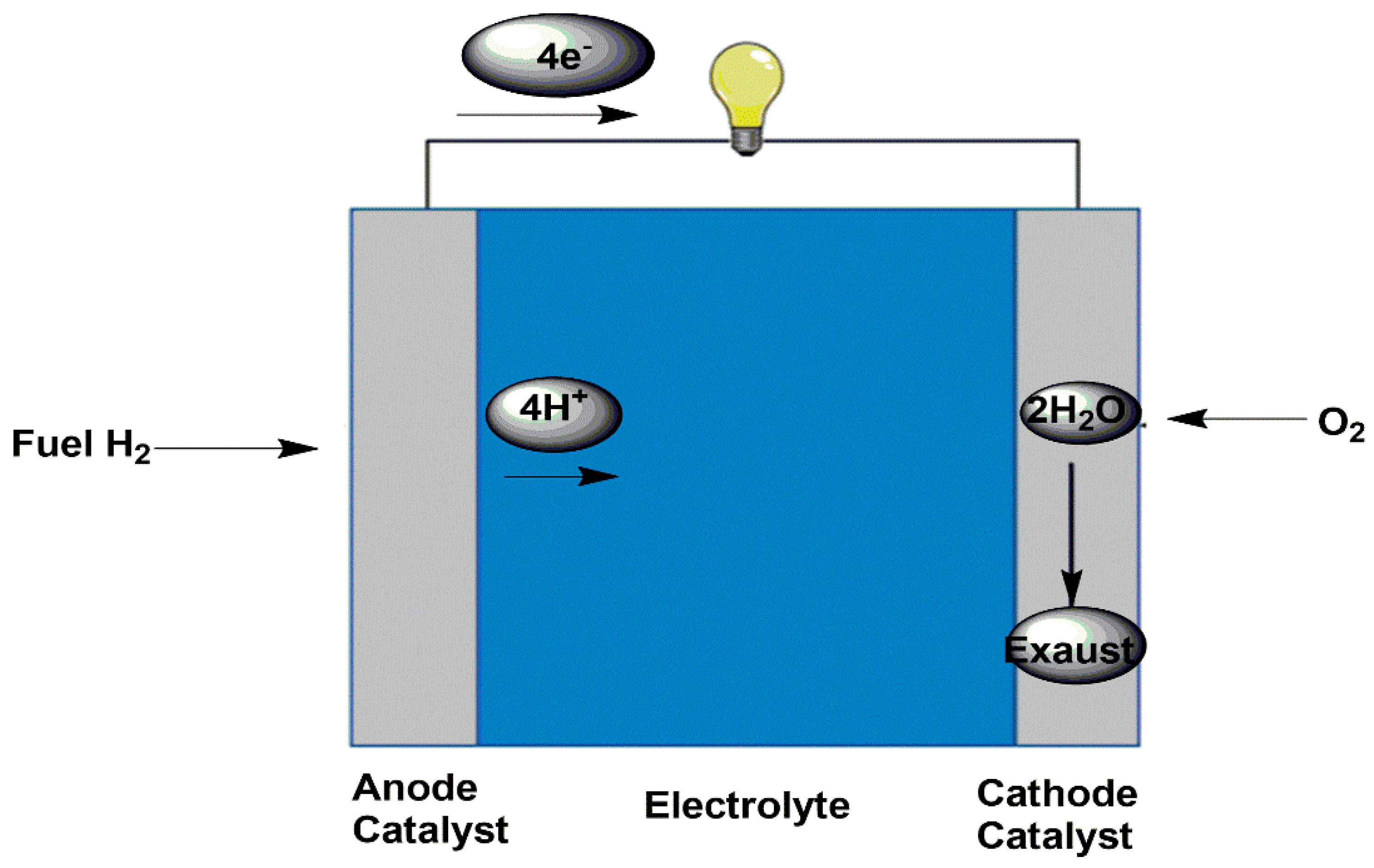

6]. Fuel cells directly generate electricity through the electrochemical reduction of oxygen and oxidation of fuel, resulting in water as the sole product [

7]. Significantly, the use of oxygen as an oxidant enables fuel cells to efficiently convert the chemical energy stored in biomass-derived fuel cells, such as methanol (CH

3OH) and Hydrogen (H

2), into electrical energy, promoting environmental friendliness [

8]. As a result, efficient ORR catalysis is necessary in fuel cells to transform electrochemical energy [

9]. Consequently, the continuous pursuit of discovering and refining innovative fuel cell catalysts has consistently propelled academic and business research globally. Additionally, the oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) is widely acknowledged as a model multielectron process, extensively employed in various electrocatalytic reactions [

10].

Figure 1.

A Schematic Representation of Fuel Cell.

Figure 1.

A Schematic Representation of Fuel Cell.

The ORR on the cathode is a key bottleneck in fuel cells due to the slow kinetics [

11]. The problem with oxygen reduction is caused by the extremely high energy of the O

2 bond (498 kJ/mol) and the slow kinetic activation [

12]. Platinum based catalyst have traditionally been proved to have the greatest ORR catalyst [

13]. However, this form of precious metal material, is costly, prone to methanol toxicity, and difficult to manufacture [

14]. These defects not only deactivate the catalyst and fuel cross-effects, but also hinder fuel cells from being widely used. Because of their low cost, high efficiency, and stability, non-precious metal (NPM)-based ORR electrocatalysts are being evaluated as viable replacements for Pt [

15]. It should also be noted that non-Pt-based electrocatalysts are commonly used in a wide pH range. It should also be mentioned that non-Pt-based electrocatalysts are typically utilised in a broad pH range [

16]. In this study we summarize some of these essential ideas and present our current understanding of the ORR process in the context of the most often researched metal catalyst.

2. Oxygen Reduction Reaction

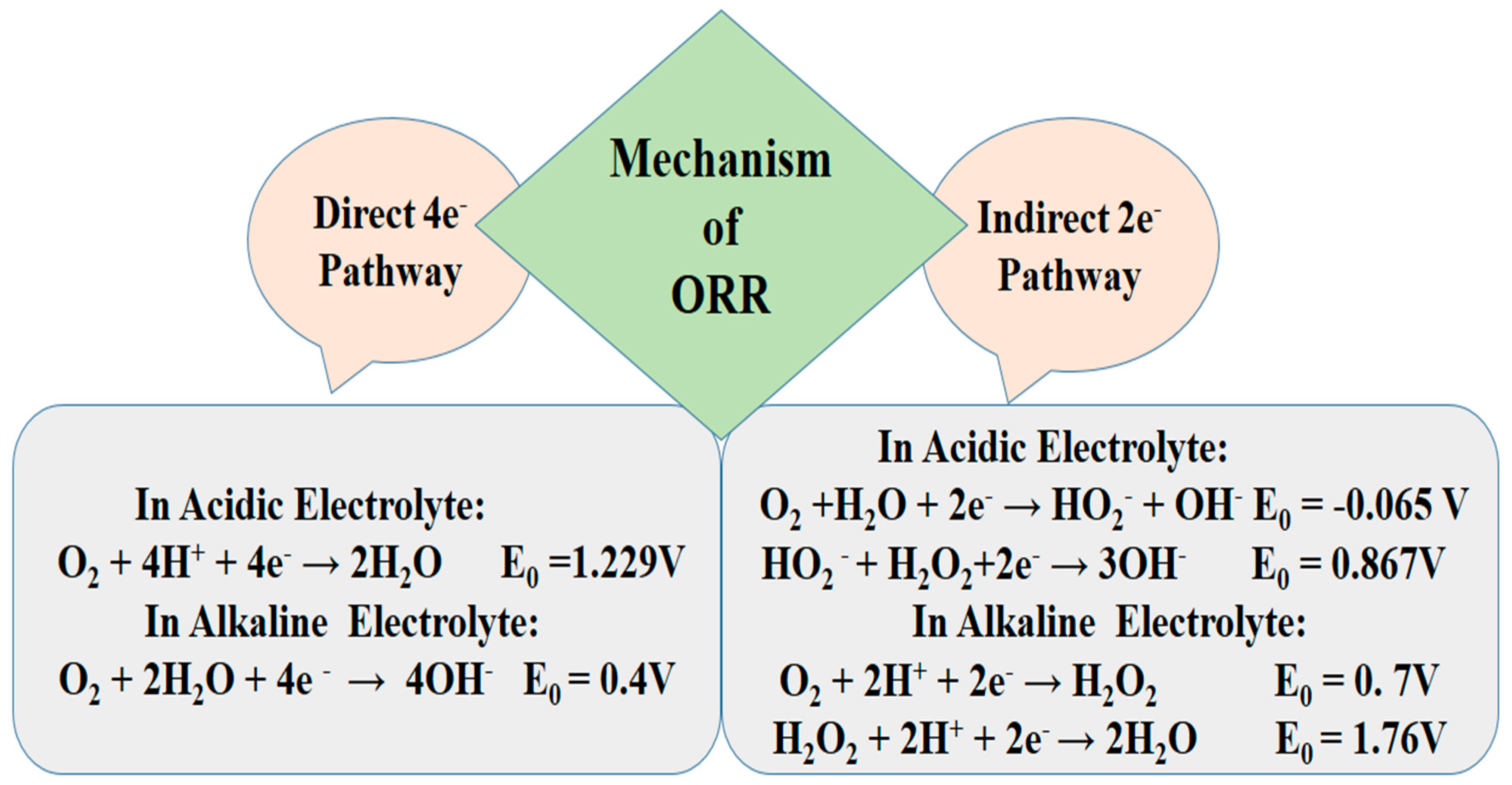

2.1. Mechanism of Oxygen Reduction Reaction

Oxygen stands out as the most prevalent element within the structure of Earth crust. The Oxygen Reduction Reaction (ORR) holds significance in various biological and chemical energy conversion processes. With the cathode serving as the focal point for the electrochemical reduction of oxygen in numerous fuel cells, there has been a noticeable surge in the exploration of electrochemical ORR methods [

17]. The way oxygen molecules are built plays a crucial role in how they can be electrochemically reduced. Following Hund’s rule, oxygen exists in a “triple state” meaning it has two unpaired electrons spinning in the same direction. These reside in the p

* orbital, separate from the main “sigma bond” and two “pi bonds” that holds the oxygen atoms together. While the bond order and energy tell us how strong the O-O bond is (2 in order, 498.7KJ/mol), breaking it entirely isn’t the first step in oxygen’s electrochemical reduction. Instead, it often takes a detour, forming a temporary partnership with an electron becoming the superoxide ion (O

2-) This interaction is weaker (bond energy of 350 KJ/mol), making it a more favorable initial step [

18]. The electrochemical reduction of oxygen is a complex process with multiple interconnected phases happening simultaneously. Each phase involves shift in electron pairing and bond adjustments, eventually leading to water formation [

19]. The primary pathways for ORR in aqueous environment involve either a four-electron transition from Oxygen (O

2) to water (H

2O) or a two electron conversion to H

2O

2, with the widely accepted mechanism initially proposed by Damjanovic [

20] as shown in

Figure 2. Wroblowa and his coworkers [

21] further refined Damjanovic model, making the complex reaction pathway easier to understand. Their work highlighted the comparable rates of both pathways, emphasizing the delicate balance at play in oxygen reduction on metal surfaces. The progression of ORR pathways is influenced by the acidity or alkalinity of the electrolyte [

22].

The complexity of the indirect 2e

− Oxygen Reduction Reaction (ORR) pathway is evident, surpassing that of the direct 4e− pathway in both acidic and basic electrolyte environments. The involvement of H

2O

2, known for its potent oxidizing effect, introduces challenges. H

2O

2 not only participates in reversible reactions, re-engaging O

2 in the reaction and thereby diminishing overall efficiency, but it also poses a potential threat to the cathode properties, potentially causing damage [

23]. The design goal for the ideal cathode catalyst is to enhance the efficiency of the oxygen reduction reaction by favoring the 4e− pathway, operating at higher potential, and facilitating the direct conversion of oxygen to water in one step [

24]. These features collectively contribute to achieving high output voltage and energy conversion rates in fuel cells. Researchers and scientists in the field of electrocatalysis and fuel cell technology continually work towards developing catalysts that meet these criteria to advance the performance of fuel cells for clean energy applications.

3. Design of ORR Electrocatalyst

Despite a decade of intense research and investment, widespread use of high-efficiency fuel cells, particularly Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells (PEMFCs), remains hindered by two major barriers: expensive and unstable ORR catalysts. Achieving significant breakthroughs in the design and development of ORR catalysts, specifically enhancing their activity and durability, could drastically transform the landscape of fuel cells and related energy technologies [

25]. ORR is a crucial reaction in these energy conversion devices, and the electrocatalyst plays a vital role in enhancing the reaction kinetics and overall performance. The design of an Oxygen Reduction Reaction (ORR) electrocatalyst involves creating a material that efficiently catalyzes the reduction of oxygen molecules in fuel cells or metal-air batteries [

26]. We need to create active sites that promote rapid oxygen reduction while ensuring these sites are readily accessible for transport of reactants like oxygen, protons, and electrons and products like water [

27]. Additionally, these vital sites must possess exceptional durability, lasting up to 30,000 hours in applications like heavy-duty vehicles [

28]. As a result, it is crucial to synthesize economically efficient electrocatalysts for oxygen reduction reactions (ORR) that exhibit efficient activity and increased durability. This is essential to promote the extensive adoption of emerging energy conversion technologies.

3.1. Platinum Group Metal Electrocatalyst

Precious metal alloys and composites are gaining significant research due to their superior ability to facilitate the oxygen reduction reaction (ORR). Pt-based alloys dramatically enhance ORR performance, but they also reduce the amount of expensive and potentially toxic platinum needed, making them a promising avenue for developing more sustainable and efficient catalysts [

29]. Early fuel cell development relied solely on black Pt nanoparticles (NPs) as catalysts for both the anode and cathode. While Pt catalysts boast superior activity and durability compared to other single noble metal options, achieving high power density necessitates a significant Pt loading due to the catalyst’s high overpotential [

30].Unfortunately, as the concentration of Pt increases in unsupported catalysts, tiny Pt nanoparticles (NPs) clump together, forming bigger structures. This “agglomeration” shrinks the overall surface area available for reactions, ultimately stifling the catalyst’s performance [

31] as shown in

Table 1.

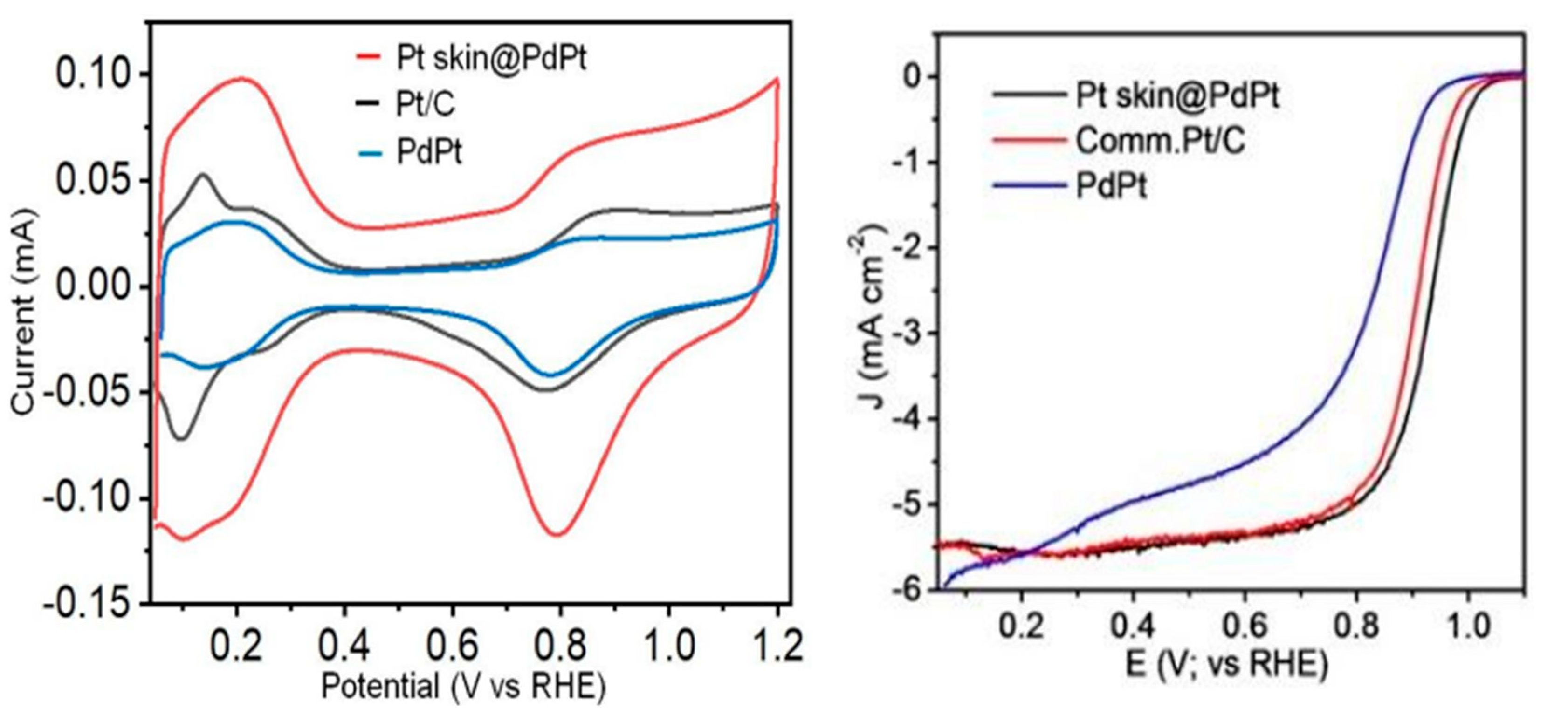

The incorporation of carbon support materials, such as carbon black (CB), carbon nanotubes (CNTs), carbon nanofibers (CNFs), carbon nanohorns, and graphene, represents a practicle shift in fuel cell catalyst design. These carbonaceous materials offer several critical advantages over unsupported Platinium (Pt) Nanoparticles (NPs) [

32]. Pure Pt nanoparticles have been ruled out as the leading catalyst for fuel cell electrodes. Despite their inherent activity and durability, the high cost and insufficient performance at achievable loadings have forced them to take a backseat. Additionally, Pt its susceptibility to CO poisoning. When it is used as single unit, CO, an intermediate in the reaction, readily adsorbs onto Pt surface, blocking active sites and decreasing overall efficiency. Therefore, modern fuel cells demand more and sophisticated solutions. By introducing a second metal, Pt gains significance when it comes to CO: faster desorption and easier oxidation. This potent combination enhances the active sites on Pt that dramatically results in accelerating reaction kinetics [

33]. Recent focus on Pt–M (M = Au, Ru, Co, Fe, Cu, or Ni) catalysts have received great attention due to their distinctive open, 3D structure. This configuration increases the accessible surface area by optimizing the utilization of noble metal atoms, resulting in increased exposure of active sites and subsequent improvements in catalytic performance [

34]. Scientists have achieved a breakthrough in catalyst design, significantly improving the durability of palladium-based catalysts while maintaining excellent activity for the oxygen reduction reaction (ORR). This was achieved by coating a thin layer of platinum (Pt) onto the palladium core, creating a “Pt skin@PdPt/C” structure. Notably, this design, when used with a low concentration of PdPt in the catalyst, demonstrated an impressive 8.8-fold enhancement in stability compared to conventional Pt/C catalysts after undergoing repeated cycles in a 0.1 M hydrochloric acid solution as shown in

Figure 3. This remarkable improvement suggests that the Pt skin effectively shields the underlying palladium, preventing its degradation while preserving the catalyst’s ORR activity. This development holds significant promise for advancing fuel cell technology and other applications that rely on efficient and durable ORR catalysts [

35]. However, complex nanostructures often face limitations due to unavoidable deformation and aggregation. Recognizing this challenge, Kim and his coworkers proposed a novel Pt-based nano-framework supported by an intermetallic compound structure. This innovative design aims to tackle these issues, offering both excellent ORR activity and superior durability in electrocatalysts [

36].

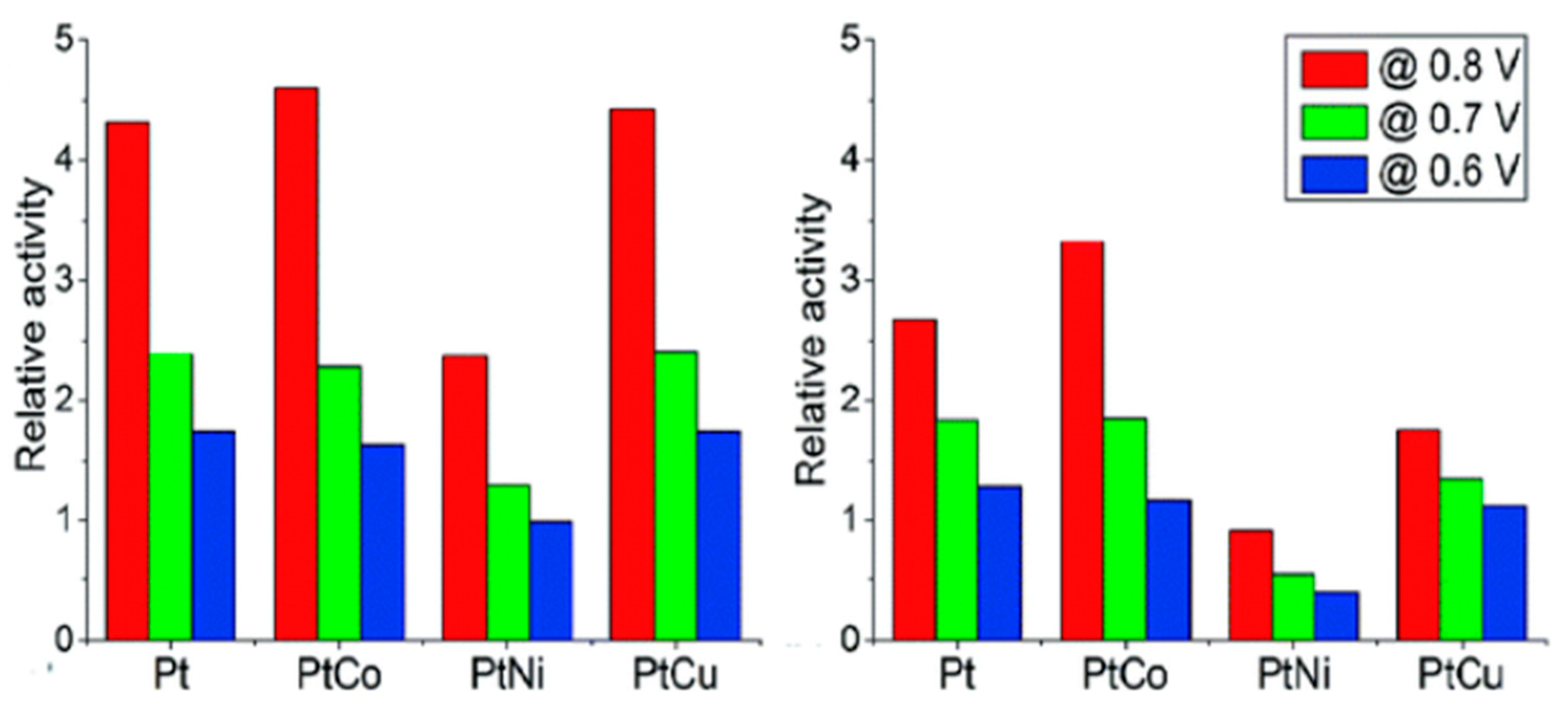

In addition Sorsa developed a method to synthesize more active catalysts for the oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) in polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cells (PEMFCs). They used a technique called potentiostatic electrodeposition to prepare PtCo, PtNi, and PtCu catalysts. All three catalysts were more efficient than commercially available Pt/C, with PtCo being the most effective performer and showed higher mass activities [

37] as shown in

Figure 4.

3.2. Non-Platinium Transition Metal Electrocatalysts

Platinum (Pt)-based catalysts hold the crown for driving the oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) in fuel cells. However, this reign comes with a high price tag and hidden vulnerabilities. While Pt boasts impressive initialization (speed of starting the reaction) and a favorable half-wave potential (voltage needed for peak activity). The first drawback is the high cost of this precious metal. Its scarcity further intensifies the issue, limiting accessibility and hindering widespread adoption of fuel cell technology. Moreover, Pt suffers from limited stability, degrading over time and requiring frequent replacements, adding to the overall expense [

38]. But the most concerning flaw is its vulnerability to methanol crossover. In applications like direct methanol fuel cells (DMFCs), fuel molecules can “leak” across the membrane, poisoning the Pt catalyst and significantly reducing its performance. This significantly limits the real-world usability of Pt-based catalysts in certain fuel cell types. These limitations highlight the urgent need for efficient and economical non-noble metal catalysts (NNMCs) to replace Pt and pave the way for a sustainable future. Replacing Pt with readily available and inexpensive alternatives would drastically reduce costs, enhance accessibility, and promote the widespread adoption of fuel cell technology. Additionally, NNMCs resistant to methanol crossover would unlock the full potential of DMFCs, particularly for portable power applications [

39]. Many studies have been done in order to reduce the cost of Platinium by reducing the amount of Pt by tuning the electrical surface of Platinium and introducing alloys. Furthermore, Pt-free catalytic materials result in significant cost-cutting measures. Recent research has shown promise in transition metal compounds like carbides, oxides, sulphides, and nitrides. These materials offer a compelling alternative to Pt and other noble metals for the oxygen reduction reaction (ORR)

, a crucial step in fuel cell operation. These abundant and earth-friendly materials could pave the way for more affordable and sustainable fuel cell technology, unlocking its full potential in various applications [

40].

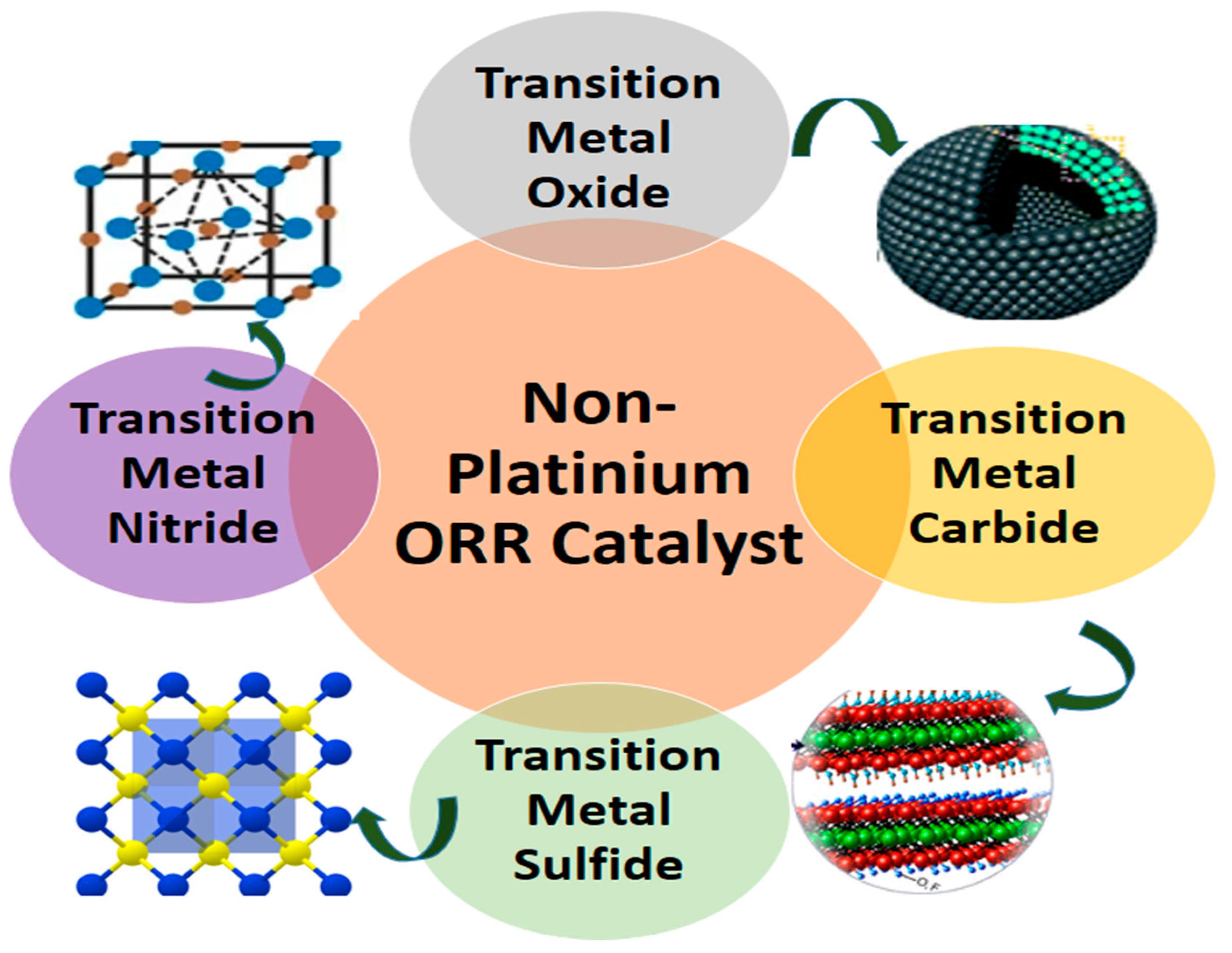

The primary focus of this section lies in discovering Pt-free materials that can achieve excellent oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) activity

. These alternative materials must not only exhibit comparable efficiency in driving the ORR reaction but also possess exceptional material stability

, matching or exceeding that of Pt. Additionally, achieving this performance at a significantly lower cost is paramount. This section covers non-Platinium ORR catalyst i.e Transition metal carbide (TMC), Transition metal Oxide (TMO), Transition metal Sulfide (TMS) and Transition metal Nitride (TMN) shown in

Figure 5

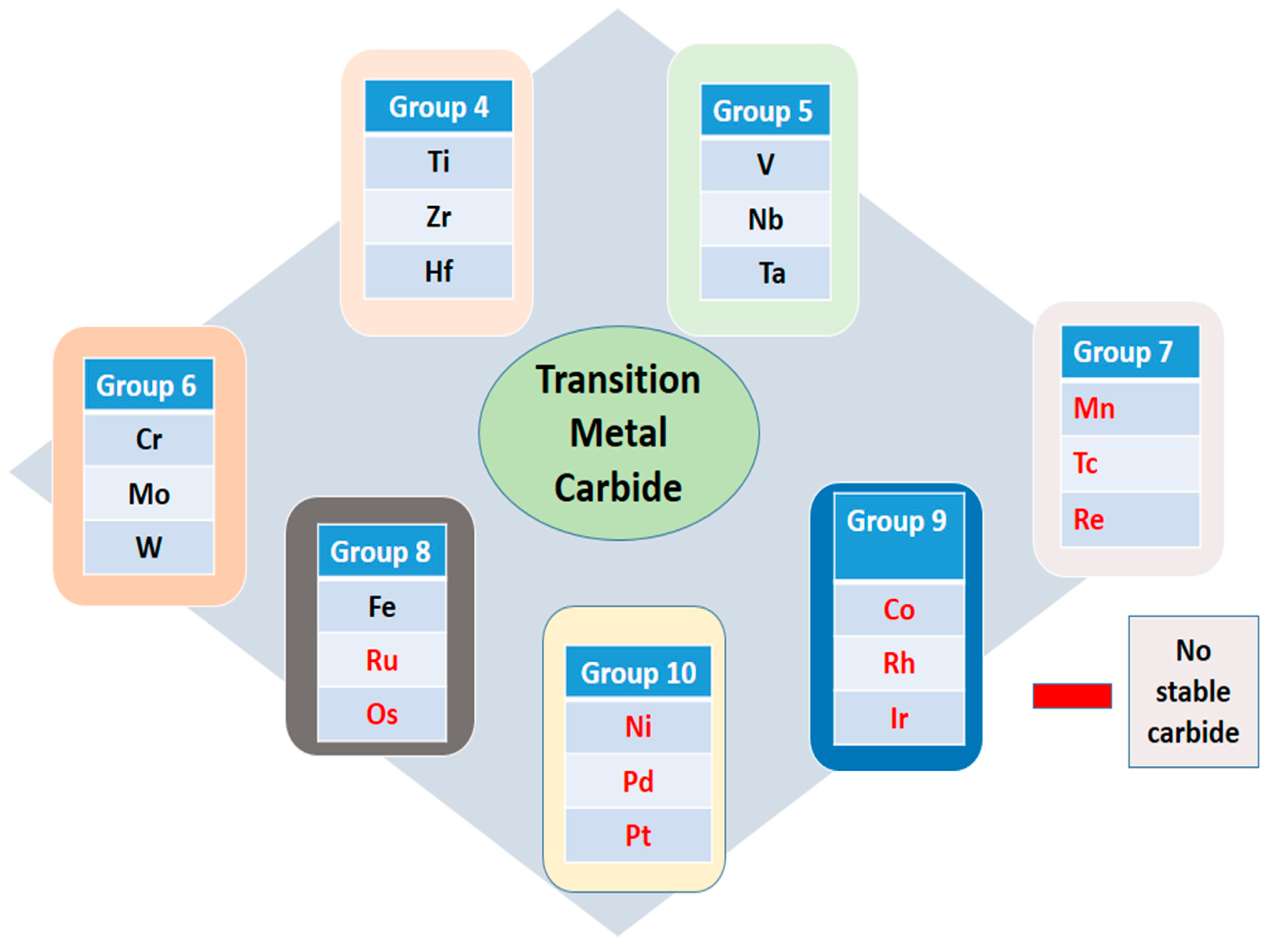

3.2.1. Transition Metal Carbide

The search for platinum replacements in fuel cells is taking an interesting turn with tungsten carbide (WC) inorganic nanoparticles emerging as promising candidates. Their surface electrical properties resemble those of metallic platinum, offering a potential alternative to the precious metal’s high cost and scarcity [

41].

Figure 6.

Transition Metal Carbide [

42]

.

Figure 6.

Transition Metal Carbide [

42]

.

Additionally, WC nanoparticles are widely available in natural deposits, further enhancing their appeal. While WC nanoparticles hold promise, research currently focuses on their utilization as anode electrocatalysts rather than ORR (oxygen reduction reaction) catalysts which have exceptional catalytic activity [

43]. However, tungsten carbide materials are unstable under high acidic and oxidation environment. The use of pure WC material as an ORR electrocatalyst in the fuel cell cathode does not appear to be feasible without modifying its composition and structure. Huang et al. used a spherical graphite-carbon-coated tungsten carbide (GC-WC) nanocomposites using a solid-state process using melamine and WO

3 as precursors [

44]. Encapsulating Fe

3C in a protective graphite shell significantly improves its stability and electrocatalytic activity in acidic media. This was demonstrated by Hu and his co-workers who showed that hollow spheres of Fe

3C encapsulated in a graphitic shell exhibited high stability and an electrochemical activity of 0.9 V, comparable to that of Pt/C (1 V). The graphitic shell protects the Fe

3C from corrosion, while the Fe

3C activates the surrounding graphite shell for the oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) [

45]. Titanium carbide has demonstrated its potential to work as ORR catalyst [

46]

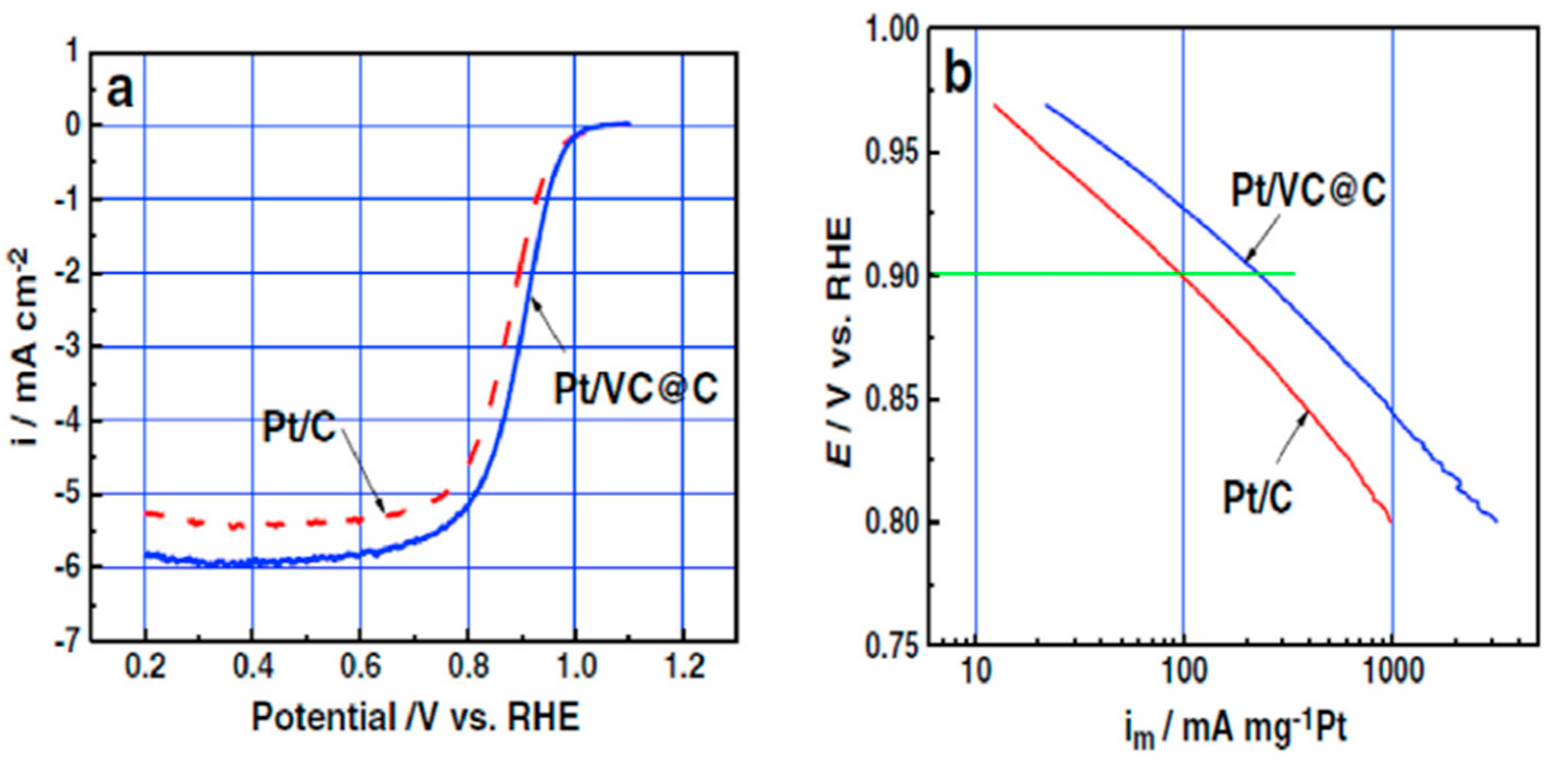

. Researchers have achieved a significant breakthrough in preparing vanadium carbide nanoparticles for electrocatalysis. Using a simple hydrothermal method, they successfully deposited uniform V

8C

7 nanoparticles with a size of 5-15 nm directly onto the surface of carbon. (Pt/VC@C) displayed outstanding ORR activity

, performing 2.4 times better than Pt/C at 0.9 V as shown in

Figure 7. The prepared V

8C

7 catalyst with impressive oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) activity suggests the effectiveness of combining platinum with vanadium carbide. Compared to the standard Pt/C catalyst, this material exhibited a significantly lower onset potential, meaning it starts working at a lower voltage (23 mV and 51 mV lower, respectively). While the introduction of nitrogen atoms slightly decreased the number of electrons involved in the ORR (from 3.9 to 3.3), this change brought two significant benefits: a reduction in the ORR overpotential by 28 mV and a notable improvement in the catalyst’s stability. Essentially, the new catalyst offers both faster and more durable performance for ORR applications [

47].

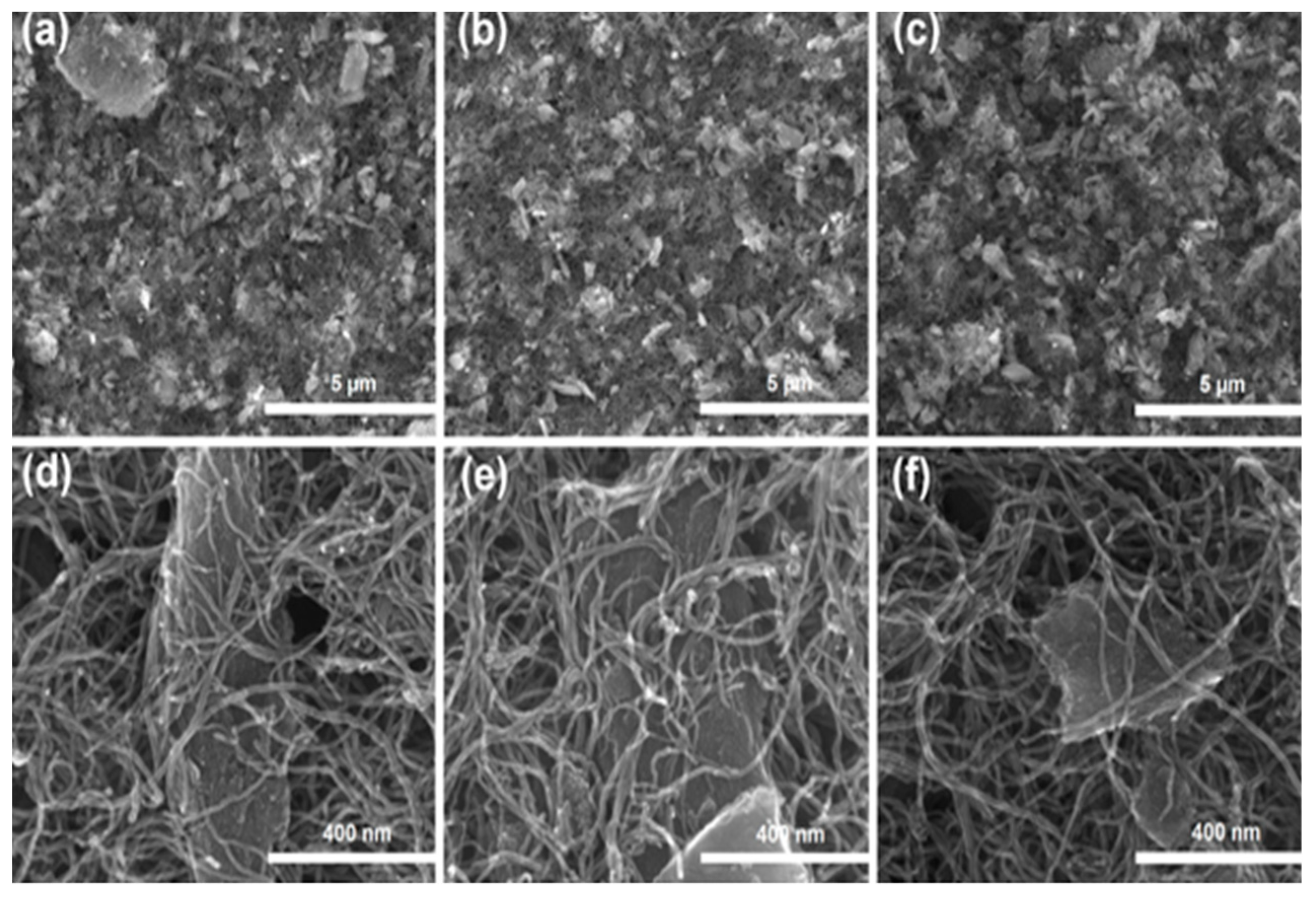

There is a wide range of carbon compounds available, but carbide-derived carbons (CDCs) are an excellent choice because they have a very high specific surface area, which is why they are widely used in electrochemical capacitors. Furthermore, CDCs may give other benefits, such as increasing the stability of ORR catalysts. CDC materials can be created from a range of carbide sources (such as SiC, TiC, ZrC, B

4C, and Mo

2C) and by altering the synthesis conditions (such as chlorination temperature), allowing the CDC porous structure to be changed and easily replicated in large quantities [

48] as illustrated in

Figure 8.

3.2.3. Transition Metal Sulfide

Transition metal sulfides (TMS) hold immense promise for electrocatalysis applications. This potential stems from their versatile electronic structure and unique physical properties. These characteristics offer flexibility in tailoring TMS materials to specific catalytic reactions, allowing researchers to optimize their performance and efficiency [

53]. Transition metal sulfides represent a fascinating class of cluster crystals. Formed through the interaction between metal centers and sulfur, they create an environment that promotes efficient oxygen adsorption and electron transfer. Additionally, the process of sulfidation alters the surface chemistry of these materials. This change protects the metal center from oxidation during electrocatalyst fabrication. Compared to metal oxides, this results in superior stability when used in acidic electrolytes [

54]. Transition metal sulfides containing elements like cobalt, iron, and nickel demonstrate exceptional potential as catalysts for the oxygen reduction reaction (ORR). However, to maximize their performance, strategies are needed to enhance their electrical conductivity. One effective approach involves integrating them with carbon matrices. Researchers have successfully created highly active ORR composite electrocatalysts by combining transition metal sulfides with carbon-based support materials. Moving forward, the development of cost-effective, efficient, and stable ORR electrocatalysts remains a crucial research focus for realizing the full potential of renewable energy technologies [

55]. Bimetallic sulfides stand out as promising electrocatalytic materials due to their advantageous properties. They boast enhanced electrical conductivity compared to their single-metal counterparts, allowing for more efficient transfer of electrons during reactions. Additionally, these materials exhibit diverse valence states, meaning the central metal atoms can exist in multiple oxidation states. This versatility offers greater flexibility in tailoring them for specific electrocatalytic processes [

56].

3.2.4. Transition Metal Nitride

Transition metal nitrides (MNx), where M represents metals like Ti, Mo, Co, or Fe, hold potential as catalysts for the oxygen reduction reaction (ORR). They demonstrate remarkable stability due to their resistance to the etching and dissolving processes that affect other transition metals under high overpotential conditions. However, this very same stability makes transition metal nitrides somewhat difficult to work with in terms of modifying or shaping them as needed [

57]. The following are the reasons for the ORR activity.

During the formation of transition metal microcrystals, nitrogen atoms readily incorporate themselves into the metal’s structure. This integration has a significant impact on the electronic properties of the material. It strengthens the d-band structure and lowers the Fermi energy level of the transition metal. This process ultimately results in the creation of transition metal nitrides (typically containing 4-6 nitrogen atoms) that exhibit characteristics remarkably similar to precious metals [

58].

Within transition metal nitrides, the nitrogen atoms carry a slight negative charge. This charge imbalance leads to electron transfer within the material, influencing the catalyst’s surface properties. Specifically, it can create either acidic or basic sites on the surface of the catalyst. Additionally, the charge transfer impacts the electron density within the d-band, a feature that directly affects the catalyst’s ability to drive the oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) more efficiently [

59].

Researchers have discovered that zirconium oxynitride and tantalum oxynitride exhibit exceptional performance in the oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) when used in sulfuric acid environments. This impressive performance is complemented by their remarkable chemical resistance, making them highly attractive materials for potential applications [

60].

Researchers synthesized a new catalyst for the oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) by combining titanium-cobalt nitride nanoparticles (Ti-Co-Np) with nitrogen-doped reduced graphene oxide (NrGO)

. This unique combination significantly outperforms both individual components and commercially available Pt/C catalysts, particularly in basic environments. The new catalyst boasts an impressive half-wave potential (E₁/₂) of 0.902 V against the reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE), surpassing Pt/C by 30 mV. Furthermore, it delivers a remarkable current density of 2.51 mA/cm² at 0.9 V (vs. RHE), signifying its efficiency in driving the ORR. Notably, the combination of Ti-Co-Np and NrGO creates a synergistic effect, leading to substantially faster ORR activity compared to either material used alone. This suggests that the two components interact in a way that enhances their individual functionalities. Additionally, the catalyst maintains its high activity even after repeated testing cycles, indicating its potential for long-lasting applications [

61]. Molybdenum carbide (Mo₂C) exhibits electrical properties similar to platinum, creating a synergistic effect when combined with a platinum catalyst. Researchers successfully produced well-dispersed 3-nanometer Mo₂C particles on carbon nanotubes using a microwave-assisted method. This platinum supported molybdenum carbide catalyst displayed a high ratio of electrochemically active surface area to volume and a higher oxygen reduction initiation voltage compared to platinum alone on carbon nanotubes. Additionally, metal carbonitrides like ZrCN, TaCN, and NbCN show exceptional efficiency in oxygen reduction, particularly after partial oxidation. Their impressive ORR onset potentials are 0.97 V, 0.9 V, and 0.89 V, respectively [

62].

Conclusion and Future Perspectives

This review explores recent advancements in developing electrocatalysts for the oxygen reduction reaction (ORR). While many promising materials, both platinum-based and non-platinum-based, demonstrate excellent performance in alkaline environments, their efficiency in acidic media remains a significant hurdle. This limitation renders metal oxides, with their low intrinsic activity and insulating properties, unsuitable for cathode electrocatalysts in acidic fuel cells. To address this challenge, researchers are seeking stable ORR electrocatalysts with high electrical conductivity and enhanced stability in acidic environments. This pursuit aims to create catalysts that can effectively function across a broad range of pH levels, paving the way for more versatile applications.

Future design of high-performance ORR electrocatalysts requires careful consideration of three key aspects: material composition, dynamic structure during operation, and maintaining high purity during synthesis. Achieving an efficient, stable, affordable, and environmentally friendly electrocatalyst remains a crucial challenge. Single-atom catalysts (SACs) have attracted significant interest due to their exceptional catalytic activity, stability, and selectivity. However, their application faces limitations. The low metal content (around 1%) in SACs arises from the limited surface area of the supporting material and the weak bond between the metal atom and the support. This inevitably hinders their overall electrochemical efficiency. Consequently, novel porous nanomaterials hold promise as viable carriers for SACs, but their implementation presents challenges in both material design and synthesis.

References

- Z. Yang, H. Nie, X. Chen, and S. Huang, “Recent progress in doped carbon nanomaterials as effective cathode catalysts for fuel cell oxygen reduction reaction,” Journal of Power Sources, vol. 236, pp. 238-249, 2013.

- Jin, H., Guo, C., Liu, X., Liu, J., Vasileff, A., Jiao, Y., ... & Qiao, S. Z. (2018). Emerging two-dimensional nanomaterials for electrocatalysis. Chemical reviews, 118(13), 6337-6408. [CrossRef]

- Kendall, M. (2018). Fuel cell development for New Energy Vehicles (NEVs) and clean air in China. Progress in Natural Science: Materials International, 28(2), 113-120. [CrossRef]

- Yoo, R., Pranada, E., Johnson, D., Qiao, Z., & Djire, A. (2022). The Oxygen Reduction Reaction on MXene-Based Catalysts: Progress and Prospects. Journal of The Electrochemical Society, 169(6), 063513. [CrossRef]

- Chu, S., & Majumdar, A. (2012). Opportunities and challenges for a sustainable energy future. nature, 488(7411), 294-303. [CrossRef]

- Yang, L., & Hu, Z. (2018). Carbon-Based, Metal-Free Catalysts for Electrocatalysis of ORR. Carbon-Based Metal-Free Catalysts: Design and Applications, 2, 335-368. [CrossRef]

- Dai, L., Xue, Y., Qu, L., Choi, H. J., & Baek, J. B. (2015). Metal-free catalysts for oxygen reduction reaction. Chemical reviews, 115(11), 4823-4892. [CrossRef]

- Wang, M., Cao, L., Li, Z., & Su, K. (2022). Herbal residue-derived N, P co-doped porous hollow carbon spheres as high-performance electrocatalysts for oxygen reduction reaction under both alkaline and acidic conditions. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials, 329, 111556. [CrossRef]

- Stoerzinger, K. A., Risch, M., Han, B., & Shao-Horn, Y. (2015). Recent insights into manganese oxides in catalyzing oxygen reduction kinetics. ACS Catalysis, 5(10), 6021-6031. [CrossRef]

- Zaman, S., Huang, L., Douka, A. I., Yang, H., You, B., & Xia, B. Y. (2021). Oxygen reduction electrocatalysts toward practical fuel cells: progress and perspectives. Angewandte Chemie, 133(33), 17976-17996. [CrossRef]

- Di Noto, V., Negro, E., Patil, B., Lorandi, F., Boudjelida, S., Bang, Y. H., ... & Nale, A. (2022). Hierarchical Metal–[Carbon Nitride Shell/Carbon Core] Electrocatalysts: A Promising New General Approach to Tackle the ORR Bottleneck in Low-Temperature Fuel Cells. ACS catalysis, 12(19), 12291-12301. [CrossRef]

- Singh, H., Zhuang, S., Ingis, B., Nunna, B. B., & Lee, E. S. (2019). Carbon-based catalysts for oxygen reduction reaction: A review on degradation mechanisms. Carbon, 151, 160-174. [CrossRef]

- Huang, L., Zaman, S., Tian, X., Wang, Z., Fang, W., & Xia, B. Y. (2021). Advanced platinum-based oxygen reduction electrocatalysts for fuel cells. Accounts of Chemical Research, 54(2), 311-322. [CrossRef]

- Shaari, N., Kamarudin, S. K., Bahru, R., Osman, S. H., & Md Ishak, N. A. I. (2021). Progress and challenges: Review for direct liquid fuel cell. International Journal of Energy Research, 45(5), 6644-6688. [CrossRef]

- Wan, C., Duan, X., & Huang, Y. (2020). Molecular design of single-atom catalysts for oxygen reduction reaction. Advanced Energy Materials, 10(14), 1903815. [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S., Biswas, A., & Dey, R. S. (2022). Oxygen reduction reaction by non-noble metal-based catalysts. In Oxygen Reduction Reaction (pp. 205-239). Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Singh, S. K., Takeyasu, K., & Nakamura, J. (2019). Active sites and mechanism of oxygen reduction reaction electrocatalysis on nitrogen-doped carbon materials. Advanced Materials, 31(13), 1804297. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Wang, D., & Li, Y. (2021). A fundamental comprehension and recent progress in advanced Pt-based ORR nanocatalysts. SmartMat, 2(1), 56-75. [CrossRef]

- Wang, N., Ma, S., Zuo, P., Duan, J., & Hou, B. (2021). Recent progress of electrochemical production of hydrogen peroxide by two-electron oxygen reduction reaction. Advanced Science, 8(15), 2100076. [CrossRef]

- Damjanovic, A., Genshaw, M. A., & Bockris, J. M. (1967). The mechanism of oxygen reduction at platinum in alkaline solutions with special reference to H 2 O 2. Journal of the Electrochemical Society, 114(11), 1107. [CrossRef]

- Wroblowa, H. S., & Razumney, G. (1976). Electroreduction of oxygen: A new mechanistic criterion. Journal of Electroanalytical Chemistry and Interfacial Electrochemistry, 69(2), 195-201. [CrossRef]

- Yap, M. H., Fow, K. L., & Chen, G. Z. (2017). Synthesis and applications of MOF-derived porous nanostructures. Green Energy & Environment, 2(3), 218-245. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z., Cao, C., Zheng, Y., Chen, S., & Zhao, F. (2014). Abiotic oxygen reduction reaction catalysts used in microbial fuel cells. ChemElectroChem, 1(11), 1813-1821. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L., Jiang, S., Ma, W., & Zhou, Z. (2022). Oxygen reduction reaction on Pt-based electrocatalysts: four-electron vs. two-electron pathway. Chinese Journal of Catalysis, 43(6), 1433-1443. [CrossRef]

- Spendelow, J. S., Chen, K., Li, K., Wang, X., & Wu, G. (2023, August). Advanced ORR Catalysts Based on Intermetallic Nanoparticles and Metal Organic Frameworks. In Electrochemical Society Meeting Abstracts 243 (No. 38, pp. 2207-2207). The Electrochemical Society, Inc. [CrossRef]

- Huang, L., Zaman, S., Tian, X., Wang, Z., Fang, W., & Xia, B. Y. (2021). Advanced platinum-based oxygen reduction electrocatalysts for fuel cells. Accounts of Chemical Research, 54(2), 311-322. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D., Zhuang, Z., Cao, X., Zhang, C., Peng, Q., Chen, C., & Li, Y. (2020). Atomic site electrocatalysts for water splitting, oxygen reduction and selective oxidation. Chemical Society Reviews, 49(7), 2215-2264.

- Gittleman, C. S., Jia, H., De Castro, E. S., Chisholm, C. R., & Kim, Y. S. (2021). Proton conductors for heavy-duty vehicle fuel cells. Joule, 5(7), 1660-1677. [CrossRef]

- Ren, X., Lv, Q., Liu, L., Liu, B., Wang, Y., Liu, A., & Wu, G. (2020). Current progress of Pt and Pt-based electrocatalysts used for fuel cells. Sustainable Energy & Fuels, 4(1), 15-30. [CrossRef]

- Yu, X., & Ye, S. (2007). Recent advances in activity and durability enhancement of Pt/C catalytic cathode in PEMFC. Journal of Power Sources, 1(172), 133-144. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M. M., Inaba, K., Batnyagt, G., Saikawa, M., Kato, Y., Awata, R., ... & Takeguchi, T. (2021). Synthesis of catalysts with fine platinum particles supported by high-surface-area activated carbons and optimization of their catalytic activities for polymer electrolyte fuel cells. RSC advances, 11(33), 20601-20611. [CrossRef]

- Peera, S. G., Koutavarapu, R., Akula, S., Asokan, A., Moni, P., Selvaraj, M., ... & Sahu, A. K. (2021). Carbon nanofibers as potential catalyst support for fuel cell cathodes: A review. Energy & Fuels, 35(15), 11761-11799. [CrossRef]

- Bhunia, K., Khilari, S., & Pradhan, D. (2017). Trimetallic PtAuNi alloy nanoparticles as an efficient electrocatalyst for the methanol electrooxidation reaction. Dalton Transactions, 46(44), 15558-15566. [CrossRef]

- Tong, Y., Yan, X., Liang, J., & Dou, S. X. (2021). Metal-based electrocatalysts for methanol electro-oxidation: progress, opportunities, and challenges. Small, 17(9), 1904126. [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z., Yang, T., Sun, L., Zhao, Y., Li, W., Luan, J., ... & Liu, C. T. (2020). A novel multinary intermetallic as an active electrocatalyst for hydrogen evolution. Advanced Materials, 32(21), 2000385. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H. Y., Kwon, T., Ha, Y., Jun, M., Baik, H., Jeong, H. Y., ... & Joo, S. H. (2020). Intermetallic PtCu nanoframes as efficient oxygen reduction electrocatalysts. Nano Letters, 20(10), 7413-7421. [CrossRef]

- Sorsa, O., Romar, H., Lassi, U., & Kallio, T. (2017). Co-electrodeposited mesoporous PtM (M= Co, Ni, Cu) as an active catalyst for oxygen reduction reaction in a polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cell. Electrochimica Acta, 230, 49-57. [CrossRef]

- Kavanagh, P. (2021). On the use of surface-confined molecular catalysts in fuel cell development. Current Opinion in Electrochemistry, 29, 100765. [CrossRef]

- Peera, S. G., & Liu, C. (2022). Unconventional and scalable synthesis of non-precious metal electrocatalysts for practical proton exchange membrane and alkaline fuel cells: A solid-state co-ordination synthesis approach. Coordination Chemistry Reviews, 463, 214554. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K., Gairola, P., Lions, M., Ranjbar-Sahraie, N., Mermoux, M., Dubau, L., ... & Maillard, F. (2018). Physical and chemical considerations for improving catalytic activity and stability of non-precious-metal oxygen reduction reaction catalysts. ACS Catalysis, 8(12), 11264-11276. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y., Polani, S., Luo, F., Ott, S., Strasser, P., & Dionigi, F. (2021). Advancements in cathode catalyst and cathode layer design for proton exchange membrane fuel cells. Nature communications, 12(1), 5984. [CrossRef]

- Zarmehri, E., Raudsepp, R., Danilson, M., Šutka, A., & Kruusenberg, I. (2023). Vanadium and carbon composite electrocatalyst for oxygen reduction reaction. Materials Chemistry and Physics, 307, 128162. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Kelly, T. G., Chen, J. G., & Mustain, W. E. (2013). Metal carbides as alternative electrocatalyst supports. Acs Catalysis, 3(6), 1184-1194. [CrossRef]

- Lori, O., Gonen, S., Kapon, O., & Elbaz, L. (2021). Durable tungsten carbide support for Pt-based fuel cells cathodes. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, 13(7), 8315-8323. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y., Jensen, J. O., Zhang, W., Cleemann, L. N., Xing, W., Bjerrum, N. J., & Li, Q. (2014). Hollow spheres of iron carbide nanoparticles encased in graphitic layers as oxygen reduction catalysts. Angewandte Chemie International Edition, 53(14), 3675-3679. [CrossRef]

- Abdelkareem, M. A., Wilberforce, T., Elsaid, K., Sayed, E. T., Abdelghani, E. A., & Olabi, A. G. (2021). Transition metal carbides and nitrides as oxygen reduction reaction catalyst or catalyst support in proton exchange membrane fuel cells (PEMFCs). International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 46(45), 23529-23547. [CrossRef]

- Adabi, H., Shakouri, A., Zitolo, A., Asset, T., Khan, A., Bohannon, J., ... & Mustain, W. E. (2023). Multi-atom Pt and PtRu catalysts for high performance AEMFCs with ultra-low PGM content. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental, 325, 122375. [CrossRef]

- Lilloja, J., Kibena-Põldsepp, E., Sarapuu, A., Douglin, J. C., Käärik, M., Kozlova, J., ... & Tammeveski, K. (2021). Transition-metal-and nitrogen-doped carbide-derived carbon/carbon nanotube composites as cathode catalysts for anion-exchange membrane fuel cells. Acs Catalysis, 11(4), 1920-1931. [CrossRef]

- Morales, D. M., Kazakova, M. A., Dieckhöfer, S., Selyutin, A. G., Golubtsov, G. V., Schuhmann, W., & Masa, J. (2020). Trimetallic Mn-Fe-Ni oxide nanoparticles supported on multi-walled carbon nanotubes as high-performance bifunctional ORR/OER electrocatalyst in alkaline media. Advanced Functional Materials, 30(6), 1905992. [CrossRef]

- Alkhadra, M. A., Su, X., Suss, M. E., Tian, H., Guyes, E. N., Shocron, A. N., ... & Bazant, M. Z. (2022). Electrochemical methods for water purification, ion separations, and energy conversion. Chemical reviews, 122(16), 13547-13635. [CrossRef]

- Guo, L., Hwang, S., Li, B., Yang, F., Wang, M., Chen, M., ... & Xu, H. (2021). Promoting atomically dispersed MnN4 sites via sulfur doping for oxygen reduction: unveiling intrinsic activity and degradation in fuel cells. ACS nano, 15(4), 6886-6899. [CrossRef]

- Stracensky, T., Jiao, L., Sun, Q., Liu, E., Yang, F., Zhong, S., ... & Xu, H. (2023). Bypassing Formation of Oxide Intermediate via Chemical Vapor Deposition for the Synthesis of an Mn-NC Catalyst with Improved ORR Activity. ACS catalysis, 13(22), 14782-14791. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S., Zhai, D., Sun, T., Han, A., Zhai, Y., Cheong, W. C., ... & Li, Y. (2019). In situ embedding Co9S8 into nitrogen and sulfur codoped hollow porous carbon as a bifunctional electrocatalyst for oxygen reduction and hydrogen evolution reactions. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental, 254, 186-193. [CrossRef]

- Wang, M., Zhang, L., He, Y., & Zhu, H. (2021). Recent advances in transition-metal-sulfide-based bifunctional electrocatalysts for overall water splitting. Journal of Materials Chemistry A, 9(9), 5320-5363. [CrossRef]

- Noor, T., Yaqoob, L., & Iqbal, N. (2021). Recent advances in electrocatalysis of oxygen evolution reaction using noble-metal, transition-metal, and carbon-based materials. ChemElectroChem, 8(3), 447-483. [CrossRef]

- Shiraz, H. G., Crispin, X., & Berggren, M. (2021). Transition metal sulfides for electrochemical hydrogen evolution. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 46(47), 24060-24077. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H., Li, J., Li, K., Lin, Y., Chen, J., Gao, L., ... & Lee, J. M. (2021). Transition metal nitrides for electrochemical energy applications. Chemical Society Reviews, 50(2), 1354-1390. [CrossRef]

- Ścigała, A., Szłyk, E., Dobrzańska, L., Gregory, D. H., & Szczęsny, R. (2021). From binary to multinary copper based nitrides–Unlocking the potential of new applications. Coordination Chemistry Reviews, 436, 213791. [CrossRef]

- Luo, J., Qiao, X., Jin, J., Tian, X., Fan, H., Yu, D., ... & Deng, Y. (2020). A strategy to unlock the potential of CrN as a highly active oxygen reduction reaction catalyst. Journal of materials chemistry A, 8(17), 8575-8585. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, F., Kainat, K. E., & Farooq, U. (2022). A comprehensive review on materials having high oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) activity. Journal of Chemical Reviews, 4, 374-422. [CrossRef]

- Suppuraj, P., Parthiban, S., Swaminathan, M., & Muthuvel, I. (2019). Hydrothermal fabrication of ternary NrGO-TiO2/ZnFe2O4 nanocomposites for effective photocatalytic and fuel cell applications. Materials Today: Proceedings, 15, 429-437. [CrossRef]

- Hamo, E. R., Saporta, R., & Rosen, B. A. (2021). Active and stable oxygen reduction catalysts prepared by electrodeposition of platinum on Mo2C at low overpotential. ACS Applied Energy Materials, 4(3), 2130-2137. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).