Submitted:

04 March 2024

Posted:

05 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Initial ink and preparation of the ink extract

2.2. Raw fish and fish canning

2.3. Determination of lipid content and composition

2.4. Assessment of lipid oxidation development

2.5. Determination of muscle colour changes and TMA value

2.6. Statistical analysis

3. Results and discussion

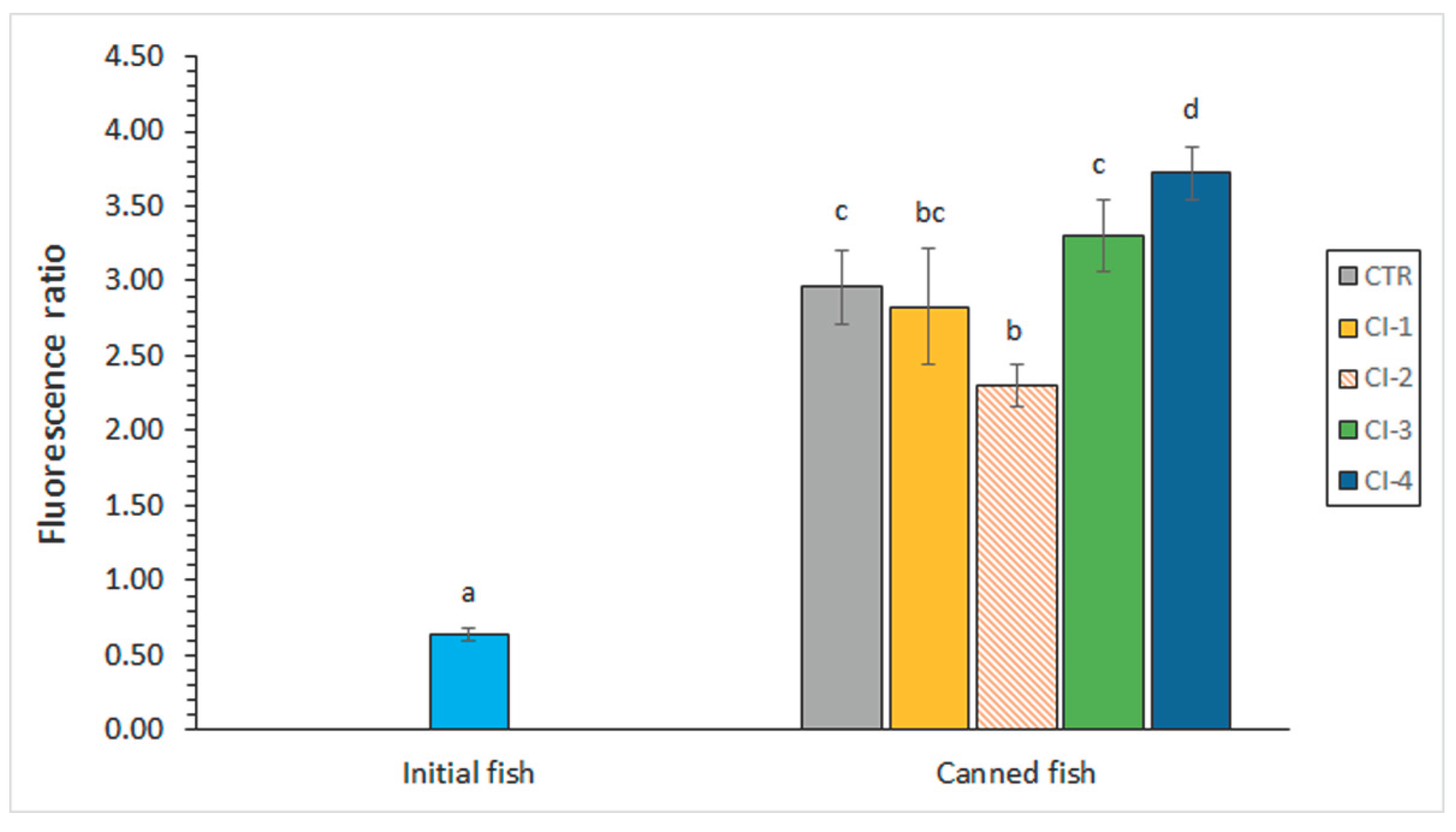

3.1. Determination of lipid oxidation evolution

3.2. Determination of FFA and PL content

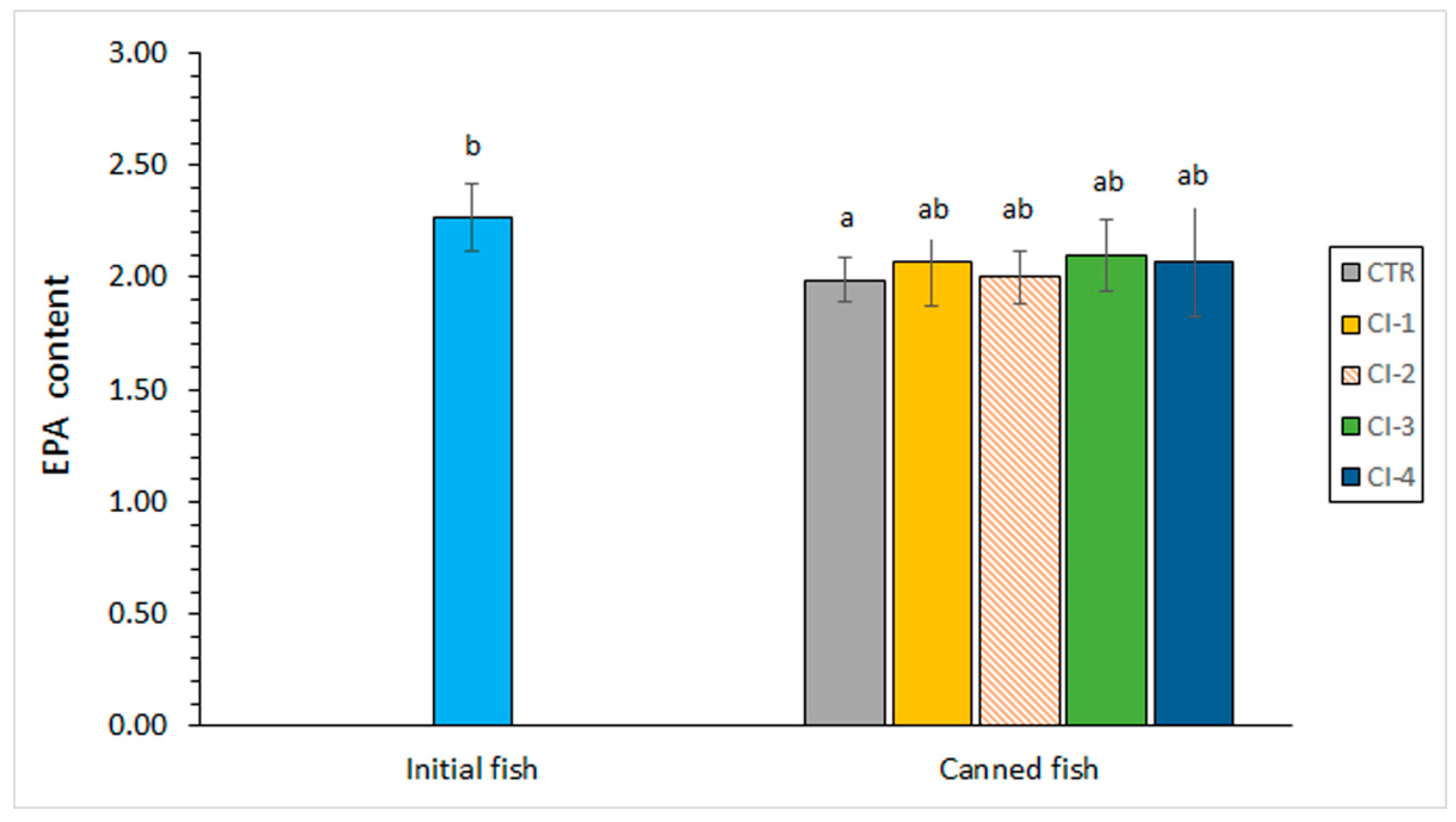

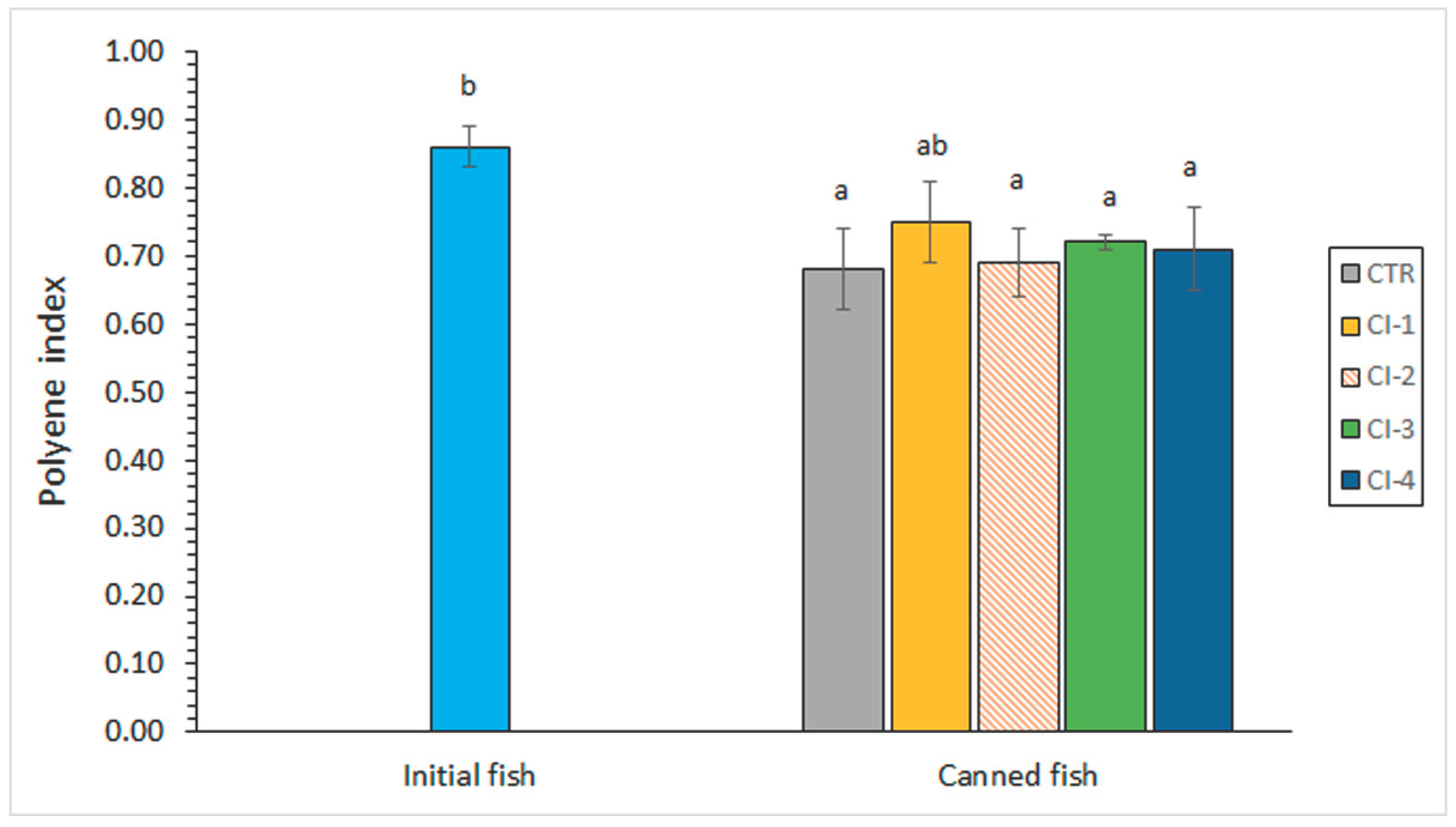

3.3. Analysis of the FA profile

3.4. Determination of colour changes in canned fish muscle

3.5. Determination of TMA content

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rustad, T.; Storro, I.; Slizyte, R. Possibilities for the utilisation of marine by-products. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 46, 2001–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, R.L.; Toppe, J.; Karunasagar, I. Challenges and realistic opportunities in the use of by-products from processing of fish and shellfish. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 36, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atef, M.; Ojagh, M. Health benefits and food applications of bioactive compounds from fish byproducts: A review. J. Funct. Foods 2017, 35, 673–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez, J.A.; Meduiña, A.; Durán, A.I.; Nogueira, M.; Fernández-Compás, A.; Pérez-Martín, R.I.; Rodríguez-Amado, I. Production of valuable compounds and bioactive metabolites from by-products of fish discards using chemical processing, enzymatic hydrolysis, and bacterial fermentation. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fahmy, S.R.; Ali, E.M.; Ahmed, N.S. Therapeutic effect of Sepia ink extract against invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in mice. J. Basic App. Zool. 2014, 67, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solano, F. Melanin and melanin-related polymers as materials with biomedical and biotechnological applications—Cuttlefish ink and mussel foot proteins as inspired biomolecules. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momenzadeh, N.; Hajian, S.; Shabankare, A.; Ghavimi, R.; Kabiri-Samani, S.; Kabiri, H.; Hesami-Zadeh, K.; Shabankareh, A.N.T.; Nazaraghay, R.; Nabipour, I.; Mohammadi, M. Photothermic therapy with cuttlefish ink-based nanoparticles in combination with anti-OX40 mAb achieve remission of triple-negative breast cancer. Int. Immunopharm. 2023, 115, 109622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neifar, A.; Abdelmalek, I.B.; Bouajila, G.; Kolsi, R.; Bradai, M.N.; Abdelmouleh, A.; Gargouri, A.; Ayed, N. Purification and incorporation of the black ink of cuttlefish Sepia officinalis in eye cosmetic products. Color. Technol. 2013, 129, 150–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Xu, T.; Zheng, B.; Cao, M.; Gao, F.; Zhou, G.; Ma, C.; Dang, J.; Yao, W.; Wu, K.; Liu, T.; Yuan, Y.; Fu, Q.; Wang, N. Cuttlefish ink loaded polyamidoxime adsorbent with excellent photothermal conversion and antibacterial activity for highly efficient uranium capture from natural seawater. J. Hazard. Mat. 2022, 433, 128789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, N.U.; Sadzali, N.L.; Hassan, M. Effects of squid ink as edible coating on squid sp. (Loligo duvauceli) spoilage during chilled storage. Int. Food Res. J. 2016, 23, 1895–1901. [Google Scholar]

- Vate, N.K.; Benjakul, S.; Agustini, T.W. Application of melanin-free ink as a new antioxidative gel enhancer in sardine surimi gel. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2015, 95, 2201–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trigo, M.; Paz, D.; Bote, A.; Aubourg, S.P. Antioxidant activity of an aqueous extract of cuttlefish (Sepia officinalis) ink during fish muscle heating. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Y.; Han, Y.; Dan, J.; Li, R.; Sun, H.; Wang, J.; Zhang, W. A high-efficient and stable artificial superoxide dismutase based on functionalized melanin nanoparticles from cuttlefish ink for food preservation. Food Res. Int. 2023, 163, 112211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derby, C.D. Cephalopod Ink: Production, chemistry, functions and applications. Mar. Drugs 2014, 12, 2700–2730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Xue, C.; Li, Y.; Gao, Z.; Ma, Q. Studies on the free radical scavenging activities of melanin from squid ink. China J. Mar. Drugs, 2007, 26, 24–27. [Google Scholar]

- Vate, N.K.; Benjakul, S. Antioxidative activity of melanin-free ink from splendid squid (Loligo formosana). Int. Aquat. Res. 2013, 5, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senan, V.P. Antibacterial activity of methanolic extract of the ink of cuttlefish, Sepia pharaonis, against pathogenic bacterial strains. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Res. 2015, 6, 1705–1710. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, J.; Li, H.; Che, H.; Dong, X.; Yang, X.; Xie, W. Extraction, physicochemical characterisation, and bioactive properties of ink melanin from cuttlefish (Sepia esculenta). Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 56, 3627–3640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horner, W. Canning fish and fish products. In Fish Processing Technology, 2nd edition; Hall, G., Ed.; Blackie Academic and Professional, Chapman and Hall: London, UK, 1997; pp. 119–159. [Google Scholar]

- Veiga, A.; Martínez, E.; Ojea, G.; Caride, A. Principles of thermal processing in canned seafood. In Quality Parameters in Canned Seafoods; Cabado, A.G., Vieites, J.M., Eds.; Nova Science Publishers, Inc.: New York, USA, 2008; pp. 83–103. [Google Scholar]

- Lukoshkina, M.; Odoeva, G. Kinetics of chemical reactions for prediction of quality of canned fish during storage. App. Biochem. Microb. 2003, 39, 321–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, B.; Tang, J.; Kong, F.; Mitcham, E.J.; Wang, S. Kinetics of food quality changes during thermal processing: A review. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2015, 8, 343–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitarch, J.L.; Vilas, C.; de Prada, C.; Palacín, C.G.; Alonso, A.A. Optimal operation of thermal processing of canned tuna under product variability. J. Food Eng. 2021, 304, 110594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokur, B.; Korkmaz, K. Novel thermal sterilization technologies in seafood processing. In Innovative Technologies in Seafood Processing; Özoğul, Y., Ed.; CRC Press, Taylor and Francis Group: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020; pp. 303–322. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Roso, B.; Cuesta, I.; Pérez, M.; Borrego, E.; Pérez-Olleros, L.; Varela, G. Lipid composition and palatability of canned sardines. Influence of the canning process and storage in olive oil for five years. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1998, 77, 244–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bligh, E.; Dyer, W. A rapid method of total extraction and purification. Can. J. Biochem. Physiol. 1959, 37, 911–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herbes, S.E.; Allen, C.P. Lipid quantification of freshwater invertebrates: Method modification for microquantitation. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 1983, 40, 1315–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowry, R.; Tinsley, I. Rapid colorimetric determination of free fatty acids. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 1976, 53, 470–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raheja, R.; Kaur, C.; Singh, A.; Bhatia, A. New colorimetric method for the quantitative determination of phospholipids without acid digestion. J. Lipid Res. 1973, 14, 695–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbosa, R.G.; Trigo, M.; Campos, C.A.; Aubourg, S.P. Preservative effect of algae extracts on lipid composition and rancidity development in brine-canned Atlantic Chub mackerel (Scomber colias). Eur. J. Lipid Sci.Technol. 2019, 1900129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, R.; McKay, J. The estimation of peroxides in fats and oils by the ferric thiocyanate method. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 1949, 26, 360–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyncke, W. Direct determination of the thiobarbituric acid value in trichloracetic acid extracts of fish as a measure of oxidative rancidity. Fette, Seifen, Anstrichm. 1970, 72, 1084–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubourg, S.P.; Medina, I.; Pérez-Martín, R.I. A comparison between conventional and fluorescence detection methods of cooking-induced damage to tuna fish lipids. Z. Lebensm. Unters. Forsch. 1995, 200, 252–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tozawa, H.; Erokibara, K.; Amano, K. Proposed modification of Dyer’s method for trimethylamine determination in codfish. In Fish Inspection and Quality Control; Kreuzer, R., Ed.; Fishing News Books Ltd.: London, UK, 1971; pp. 187–190. [Google Scholar]

- Naseri, M.; Rezaei, M. Lipid changes during long-term storage of canned sprat. J. Aquat. Food Prod. Technol. 2012, 21, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez, L.; Trigo, M.; Zhang, B.; Aubourg, S.P. Antioxidant effect of octopus by-products in canned horse mackerel (Trachurus trachurus) previously subjected to different frozen storage times. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nawar, W.W. Lipids. In Food Chemistry, 3rd edition; Fennema, O., Ed.; Marcel Dekker: New York, NY, USA, 1996; pp. 225–314. [Google Scholar]

- Pokorný, J. Introduction. In Antioxidants in Foods. Practical Applications; Pokorný, J., Yanishlieva, N., Gordon, M., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, USA, 2001; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Ramanathan, L.; Das, N. Studies on the control of lipid oxidation in ground fish by some polyphenolic natural products. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1992, 40, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, I.; Satué, M.T.; German, J.B.; Frankel, E. Comparison of natural polyphenols antioxidant from extra virgin olive oil with synthetic antioxidants in tuna lipids during thermal oxidation. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1999, 47, 4873–4879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Essid, I.; Aroussia, H.; Soufi, E.; Bouriga, N.; Gharbi, S.; Bellagha, S. Improving quality of smoked sardine fillets by soaking in cuttlefish ink. Food Sci. Technol, Campinas, 2022, 42, e65020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caponio, F.; Summo, C.; Pasqualone, A.; Gomes, T. Fatty acid composition and degradation level of the oils used in canned fish as a function of the different types of fish. J. Food Comp. Anal. 2011, 24, 1117–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, C.O.; Remya, S.; Murthy, L.N.; Ravishankar, C.N.; Kumar, K.A. Effect of filling medium on cooking time and quality of canned yellowfin tuna (Thunnus albacares). Food Cont. 2015, 50, 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kınay, A.G.; Duyar, H.A. Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis) as a preservative agent in canned bonito (Sarda sarda). Mar. Sci. Tech. Bull. 2021, 10, 406–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouriga, N.; Bahri, W.R.; Mili, S.; Massoudi, S.; Quignard, J.P.; Trabelsi, M. Variations in nutritional quality and fatty acids composition of sardine (Sardina pilchardus) during canning process in grape seed and olive oils. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 59, 4844–4852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, J.A.; Vivanco, J.P.; Aubourg, S.P. Lipid and sensory quality of canned Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar): Effect of the use of different seaweed extracts as covering liquids. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2014, 116, 596–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, R.G.; Trigo, M.; Fett, R.; Aubourg, S.P. Impact of a packing medium with alga Bifurcaria bifurcata extract on canned Atlantic mackerel (Scomber scombrus) quality. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2018, 98, 3462–3467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medina, I.; Sacchi, R.; Aubourg, S.P. A 13C-NMR study of lipid alterations during fish canning: Effect of filling medium. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1995, 69, 445–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labuza, T. Kinetics of lipid oxidation in foods. CRC Crit. Rev. Food Technol. 1971, 2, 355–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyashita, K.; Tagagi, T. Study on the oxidative rate and prooxidant activity of free fatty acids. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 1986, 63, 1380–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malga, J.M.; Trigo, M.; Martínez, B.; Aubourg, S.P. Preservative effect on canned mackerel (Scomber colias) lipids by addition of octopus (Octopus vulgaris) cooking liquor in the packaging medium. Molecules 2022, 27, 739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Küllenberg, D.; Taylor, L.A.; Schneider, M.; Massing, U. Health effects of dietary phospholipids. Lipids Health Dis. 2012, 11, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Wang, X.; Zhang, T.; Huang, Z.; Luo, X.; Deng, Y. A review on phospholipids and their main applications in drug delivery systems. Asian J. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 10, 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubourg, S.P.; Medina, I.; Pérez-Martín, R. Polyunsaturated fatty acids in tuna phospholipids: Distribution in the sn-2 location and changes during cooking. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1996, 44, 585–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, K.; Inoue, Y. Marine by-product phospholipids as booster of medicinal compounds. Adv. Food Nutr. Res. 2012, 65, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, J.P.; Müller, M.; Rainger, G.; Steegenga, W. Fish oil supplements, longevity and aging. Aging 2016, 8, 1578–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devassy, J.G.; Leng, S.; Gabbs, M.; Monirujjaman, M.; Aukema, H.M. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and oxylipins in neuroinflammation and management of Alzheimer disease. Adv. Nutr. 2016, 7, 905–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, S.; Block, R.; Mousa, S. Omega-3 fatty acids EPA and DHA: Health benefits throughout life. Adv. Nutr. 2012, 3, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofosu, F.K.; Daliri, E.B.M.; Lee, B.H.; Yu, X. Current trends and future perspectives on omega-3 fatty acids. Res. J. Biol. 2017, 5, 11–20. [Google Scholar]

- Uauy, R.; Valenzuela, A. Marine oils: The health benefits of n-3 fatty acids. Nutrition 2000, 16, 680–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komprda, T. Eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acids as inflammation-modulating and lipid homeostasis influencing nutraceuticals: A review. J. Funct. Foods 2012, 4, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simopoulos, A.P. The importance of the ratio of omega-6/omega-3 essential fatty acids. Biomed. Pharm. 2002, 56, 365–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rustad, T. Lipid oxidation. In Handbook of Seafood and Seafood Products Analysis; Nollet, L.M., Toldrá, F., Eds.; CRC Press, Francis and Taylor Group: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2010; pp. 87–95. [Google Scholar]

- Schubring, R. Quality Assessment of Fish and Fishery Products by Color Measurement. In Handbook of Seafood and Seafood Products Analysis; Nollet, L.M., Toldrá, F., Eds.; CRC Press, Francis and Taylor Group: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2010; pp. 395–424. [Google Scholar]

- Mohan, C.O.; Remya, S.; Ravishankar, C.N.; Vijayan, P.K.; Srinivasa Gopal, T.K. Effect of filling ingredient on the quality of canned yellowfin tuna (Thunnus albacares). Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 49, 1557–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Limia, L.; Carballo, J.; Rodríguez-González, M.; Martínez, S. Impact of the filling medium on the colour and sensory characteristics of canned European eels (Anguilla anguilla L.). Foods 2022, 11, 1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özoğul, Y. Methods for freshness quality and deterioration. In Handbook of Seafood and Seafood Products Analysis; Nollet, L.M., Toldrá, F., Eds.; CRC Press, Francis and Taylor Group: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2010; pp. 189–214. [Google Scholar]

- Selmi, S.; Monser, L.; Sadok, S. The influence of local canning process and storage on pelagic fish from Tunisia: Fatty acids profile and quality indicators. J. Food Proc. Preserv. 2008, 32, 443–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubourg, S.P.; Trigo, M.; Martínez, B.; Rodríguez, A. Effect of prior chilling period and alga-extract packaging on the quality of a canned underutilised fish species. Foods 2020, 9, 1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadok, S.; Abdelmoulah, A.; El Abed, A. Combined effect of sepia soaking and temperature on the shelf life of peeled shrimp Penaeus kerathurus. Food Chem. 2004, 88, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Initial or canned sample | Lipid oxidation index | |

|---|---|---|

| Peroxide value (meq. active oxygen·kg-1 lipids) | Thiobarbituric acid index (mg malondialdehyde·kg-1 muscle) | |

| Initial fish | 1.65 ab (0.34) |

0.08 a (0.02) |

| CTR | 1.10 a (0.18) |

0.07 a (0.03) |

| CI-1 | 2.06 b (0.53) |

0.08 a (0.03) |

| CI-2 | 1.37 ab (0.63) |

0.09 a (0.03) |

| CI-3 | 1.53 ab (0.19) |

0.10 a (0.02) |

| CI-4 | 1.98 ab (0.85) |

0.13 a (0.03) |

| Initial or canned sample | Chemical determination | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| FFA (g·kg-1 lipids) |

PL (g·kg-1 lipids) |

TMA (mg TMA-N·kg-1 muscle) |

|

| Initial fish | 0.49 a (0.05) |

39.69 b (3.84) |

2.71 a (0.33) |

| CTR | 1.58 b (0.31) |

29.30 a (3.74) |

5.25 c (0.94) |

| CI-1 | 1.90 b (0.26) |

35.01 ab (3.39) |

3.92 bc (0.41) |

| CI-2 | 1.87 b (0.19) |

27.01 a (4.51) |

3.90 b (0.30) |

| CI-3 | 1.96 b (0.60) |

28.75 a (3.46) |

4.51 bc (0.74) |

| CI-4 | 1.97 b (0.27) |

29.42 a (3.14) |

3.93 bc (0.42) |

| Initial or canned sample | FA parameter | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| DHA | Total ω3 | ω3/ω6 ratio | |

| Initial fish | 11.96 b (0.74) |

16.62 b (0.94) |

0.57 b (0.03) |

| CTR | 8.74 a (1.14) |

12.88 a (1.26) |

0.42 a (0.05) |

| CI-1 | 9.70 a (0.95) |

13.89 a (1.23) |

0.46 a (0.04) |

| CI-2 | 9.12 a (0.34) |

13.58 a (0.19) |

0.47 a (0.01) |

| CI-3 | 8.41 a (1.13) |

12.50 a (1.15) |

0.42 a (0.05) |

| CI-4 | 8.66 a (0.95) |

12.90 a (1.30) |

0.42 a (0.05) |

| Initial or canned sample | Colour parameter | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| L* | a* | b* | |

| Initial fish | 46.35 a (0.96) |

2.21 b (0.76) |

-3.76 a (0.24) |

| CTR | 81.40 c (2.03) |

-1.07 a (0.51) |

8.98 b (0.68) |

| CI-1 | 55.54 ab (8.39) |

2.18 b (0.67) |

6.81 b (1.79) |

| CI-2 | 63.48 b(6.09) | 1.38 b (0.83) |

7.31 b (1.06) |

| CI-3 | 62.46 b (4.58) |

1.53 b (0.36) |

8.66 b (1.95) |

| CI-4 | 60.39 b (5.50) |

1.91 b (0.36) |

7.39 b (0.99) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).