Submitted:

03 March 2024

Posted:

05 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

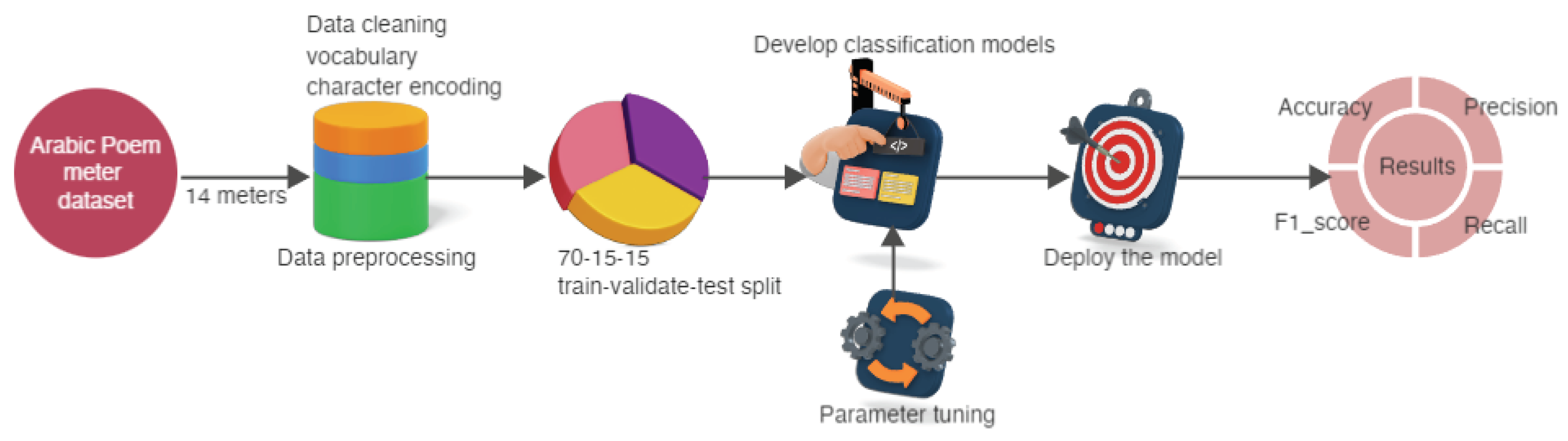

3. Materials and Method

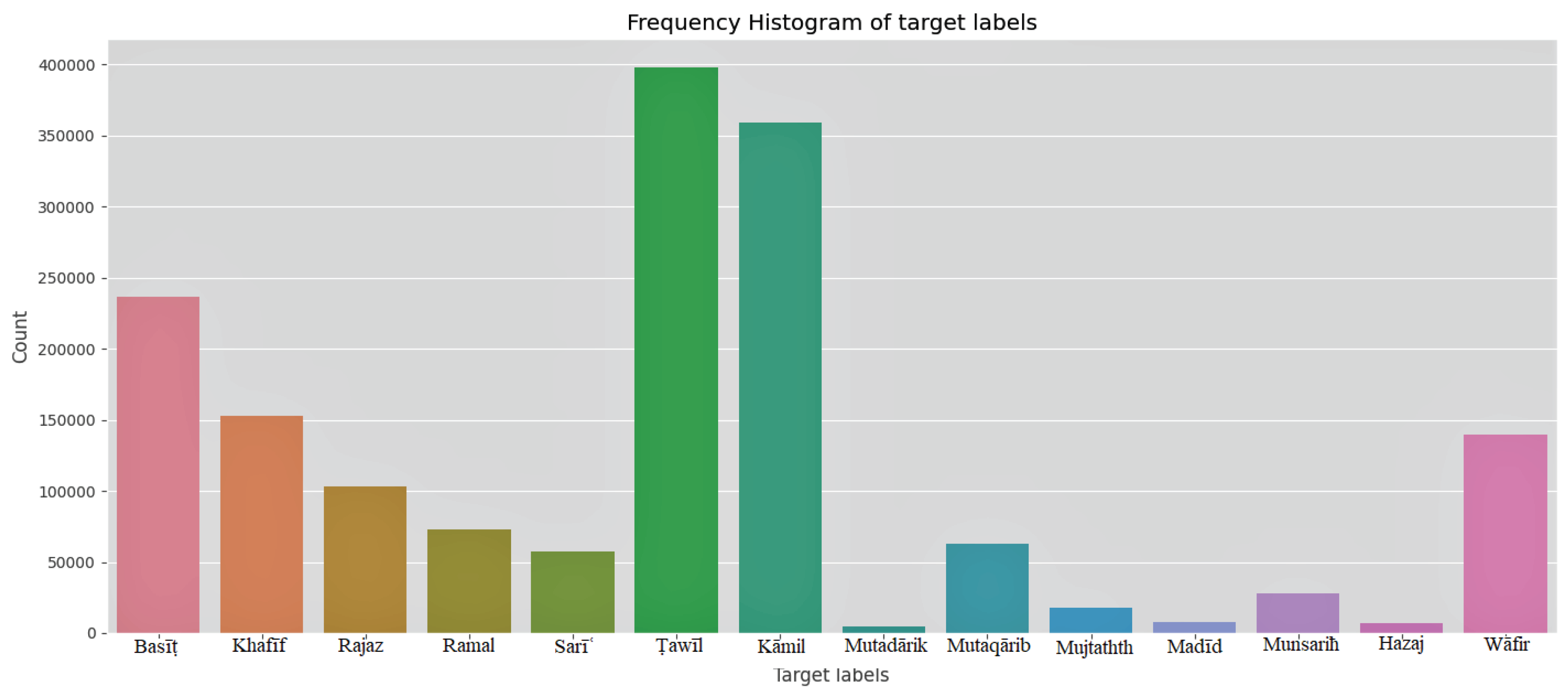

3.1. Dataset and Preprocessing

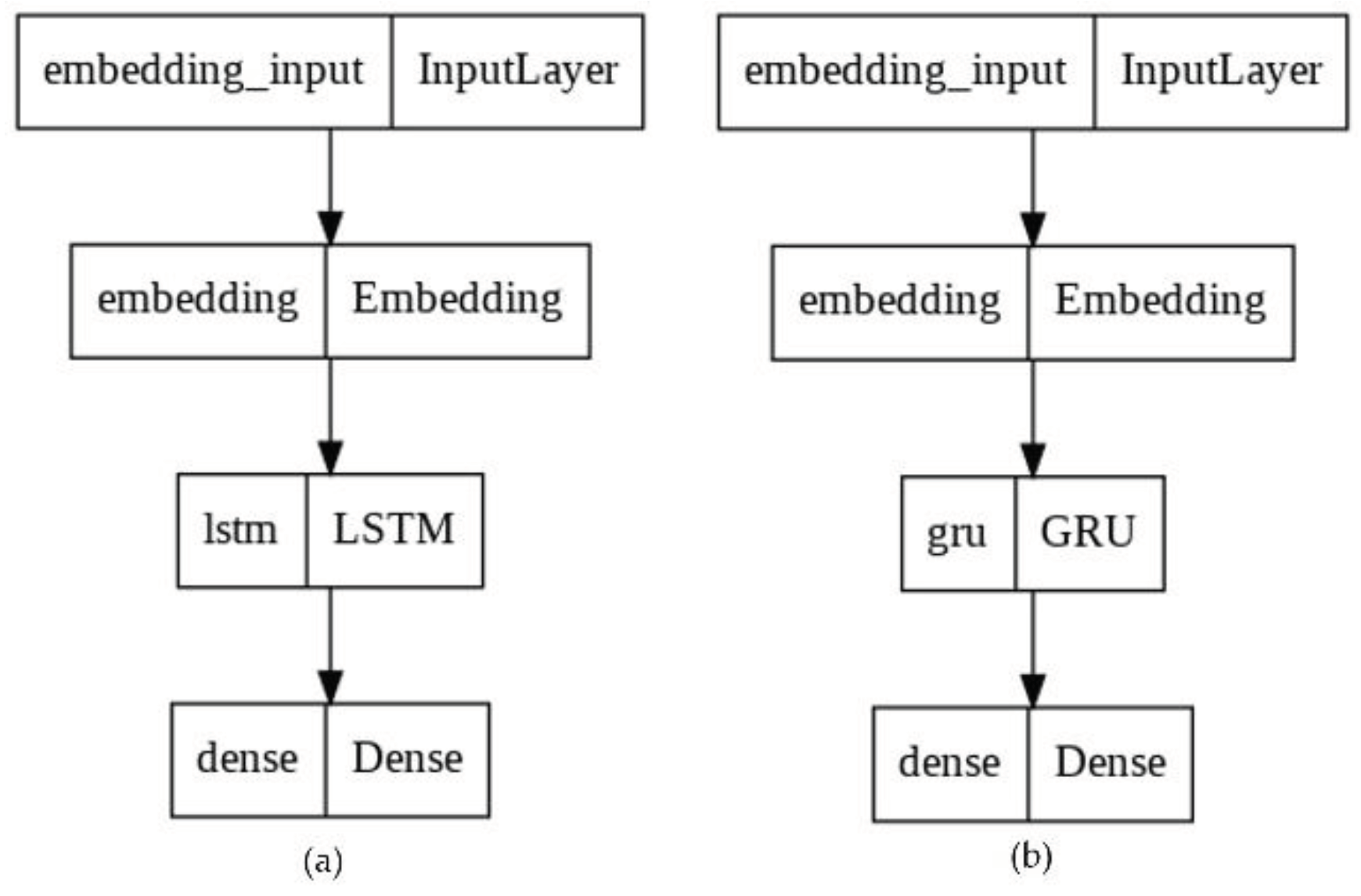

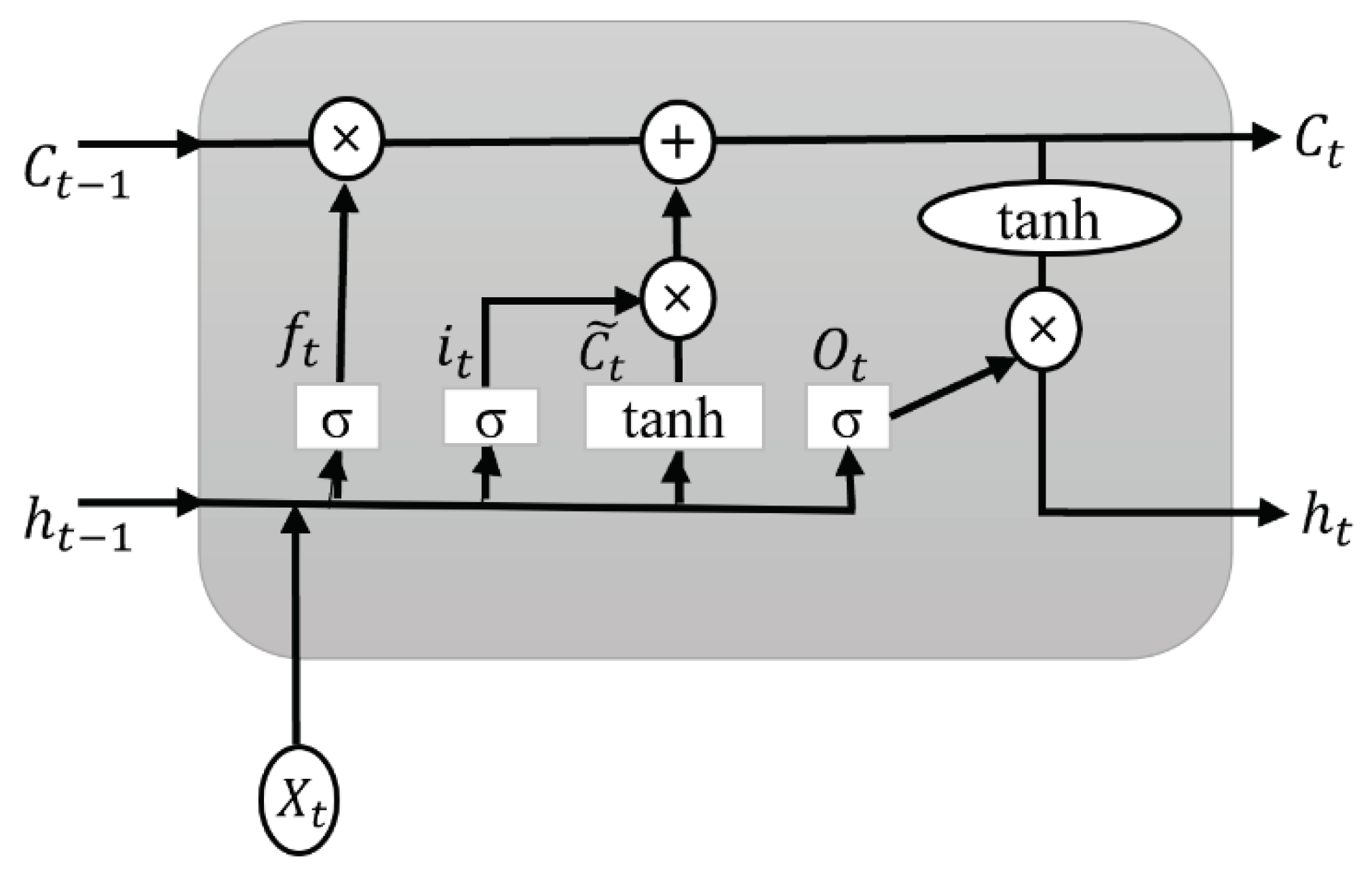

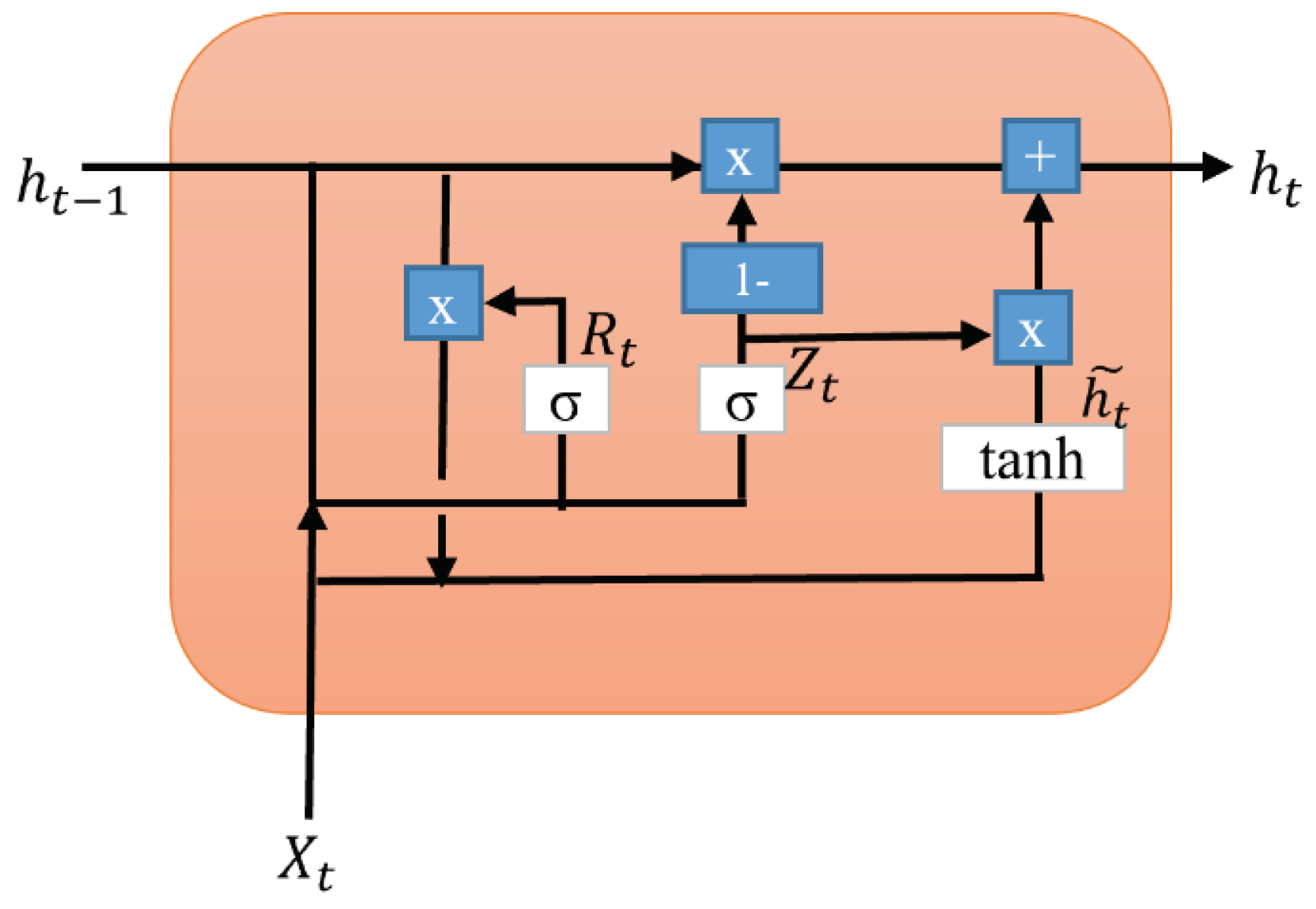

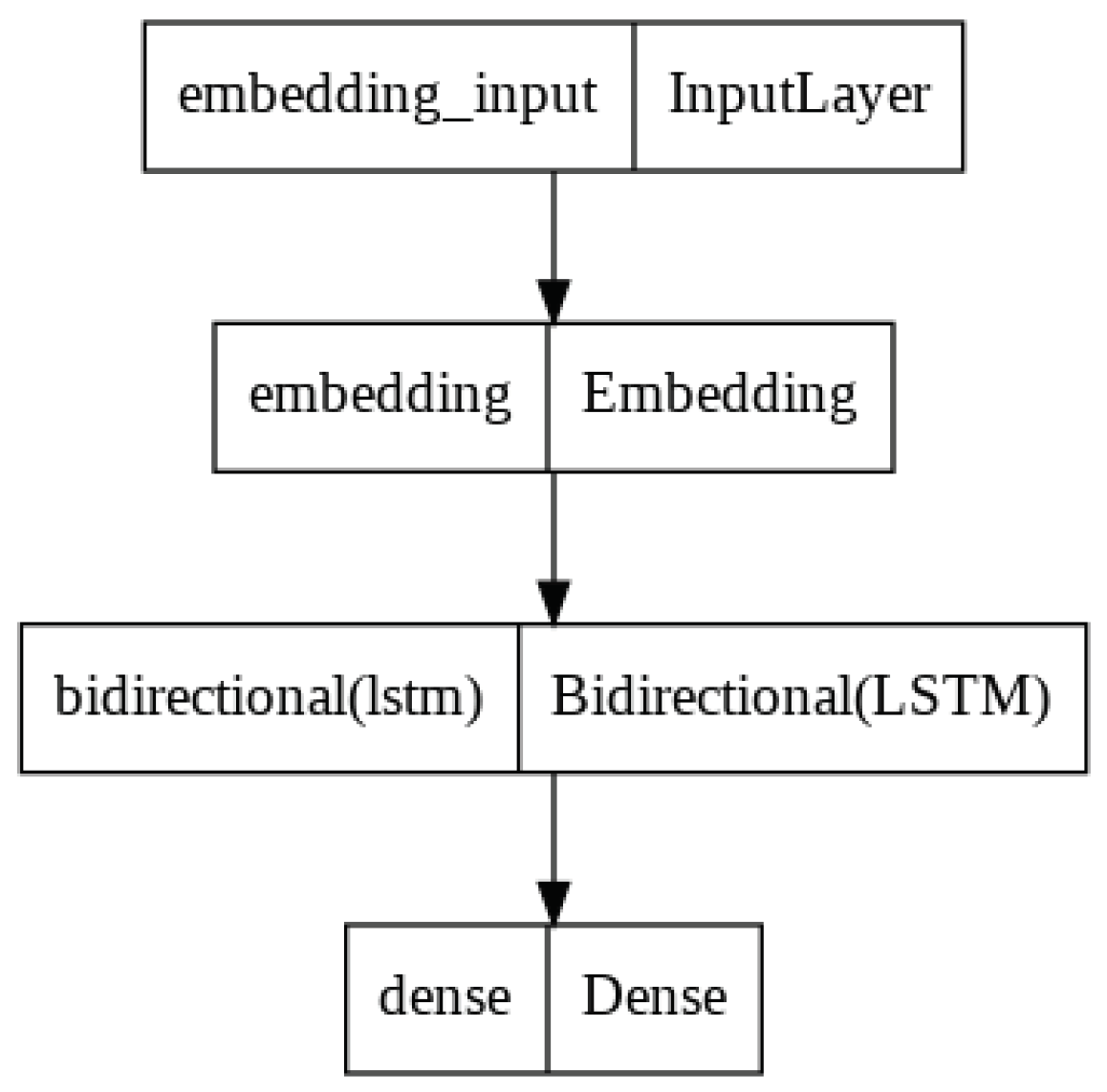

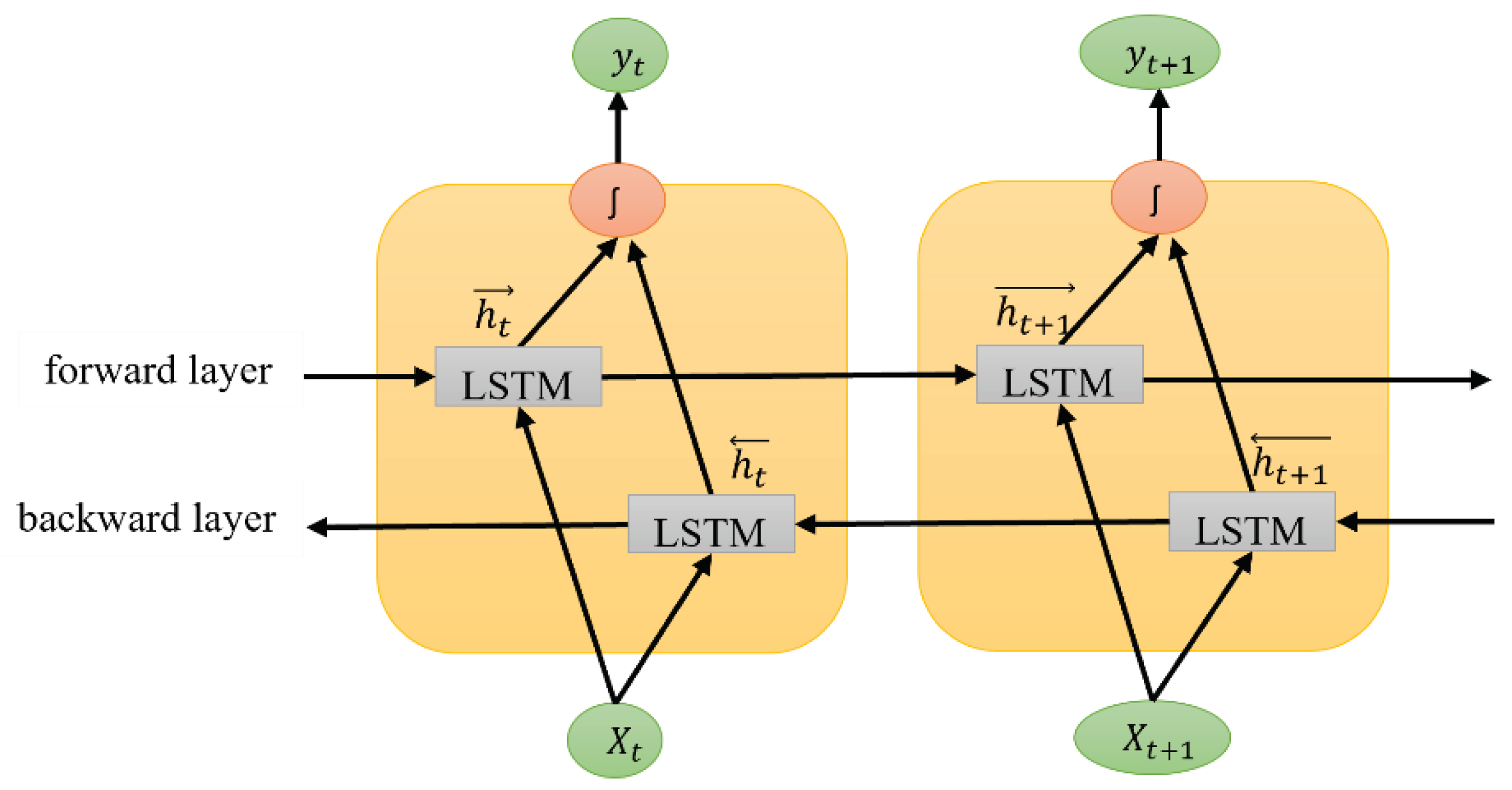

3.2. Deep Learning Models

3.2.1. Hyper-Parameter Tuning

3.3. Evaluation Metrics

4. Results

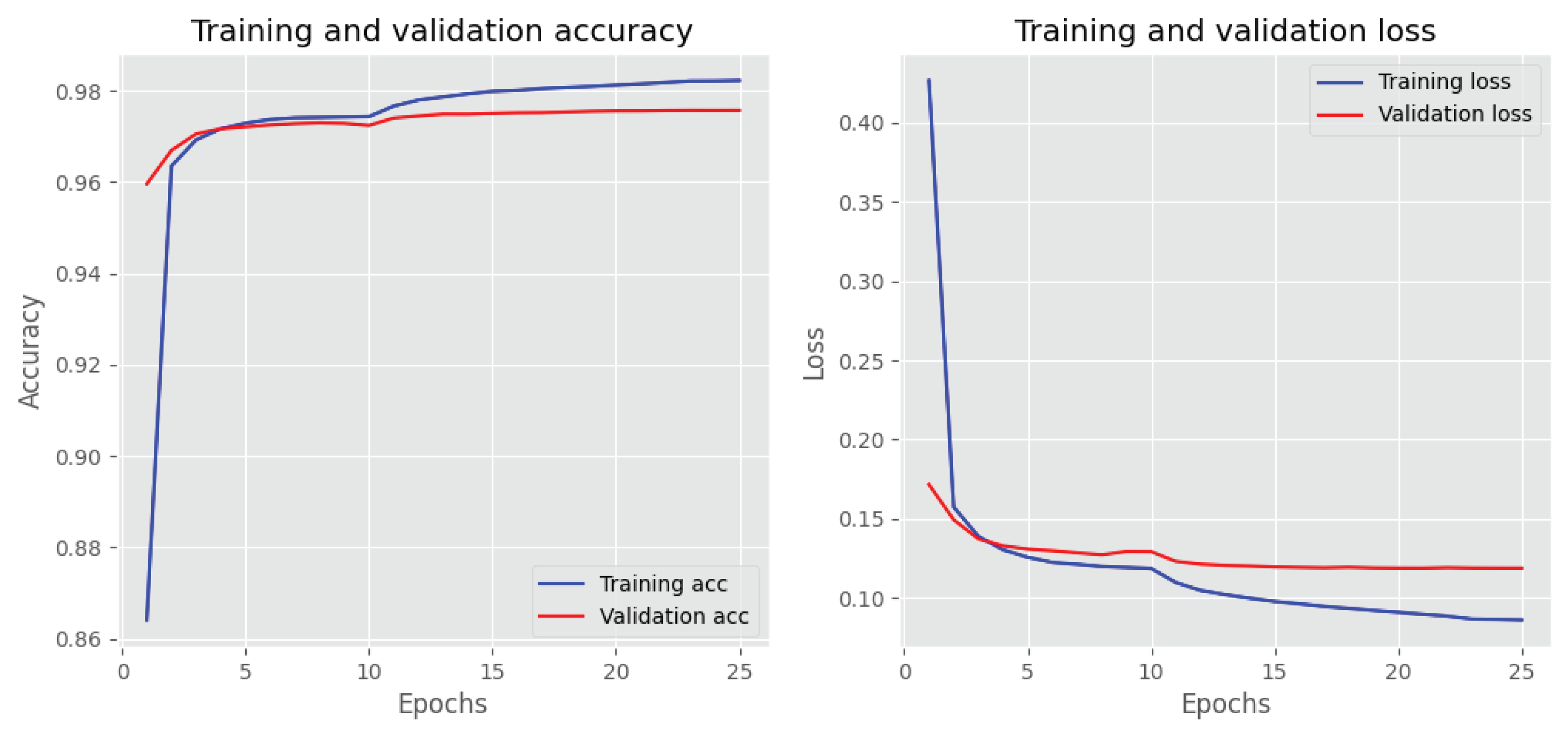

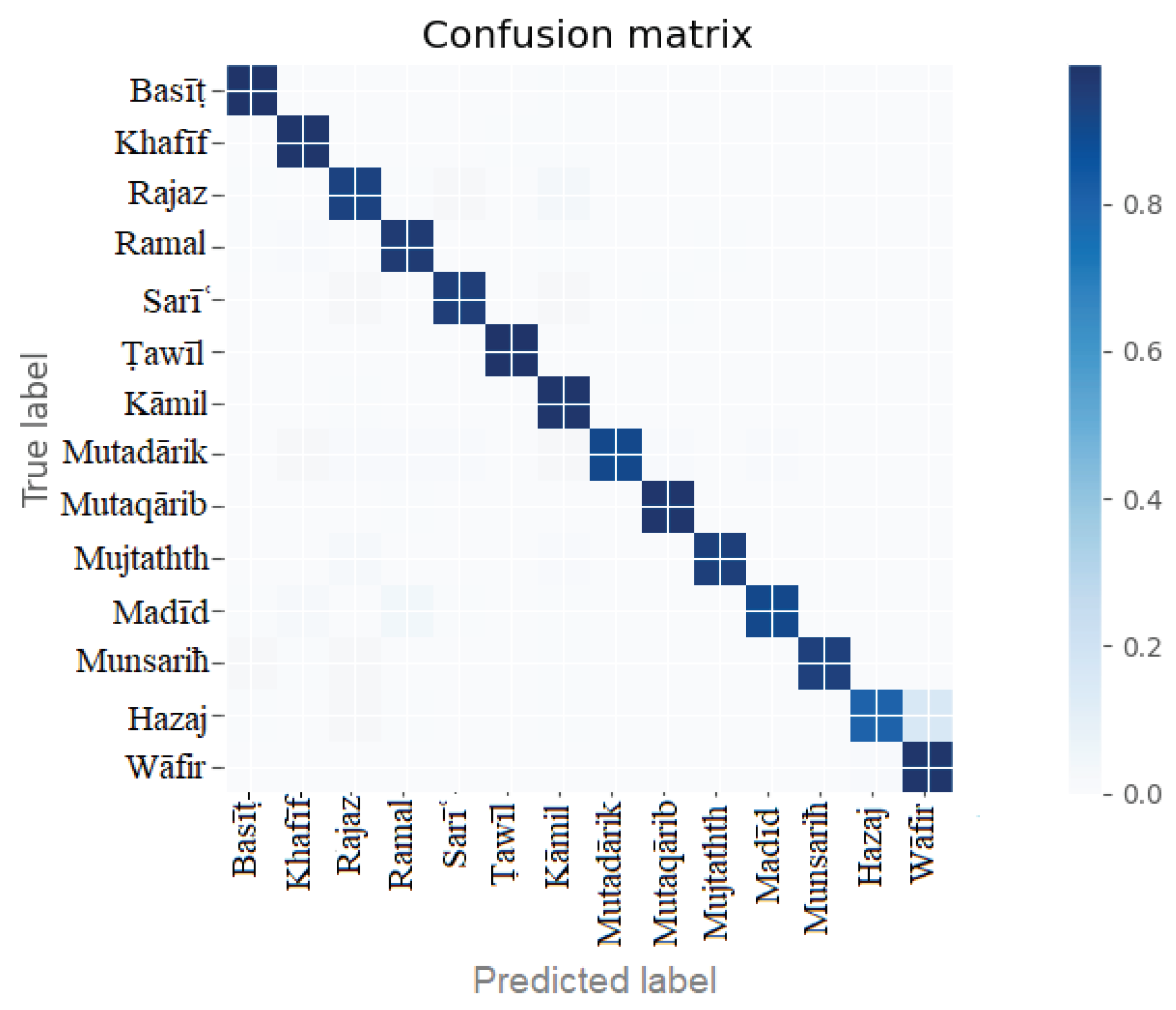

4.1. Training and Testing Using Full-Verse

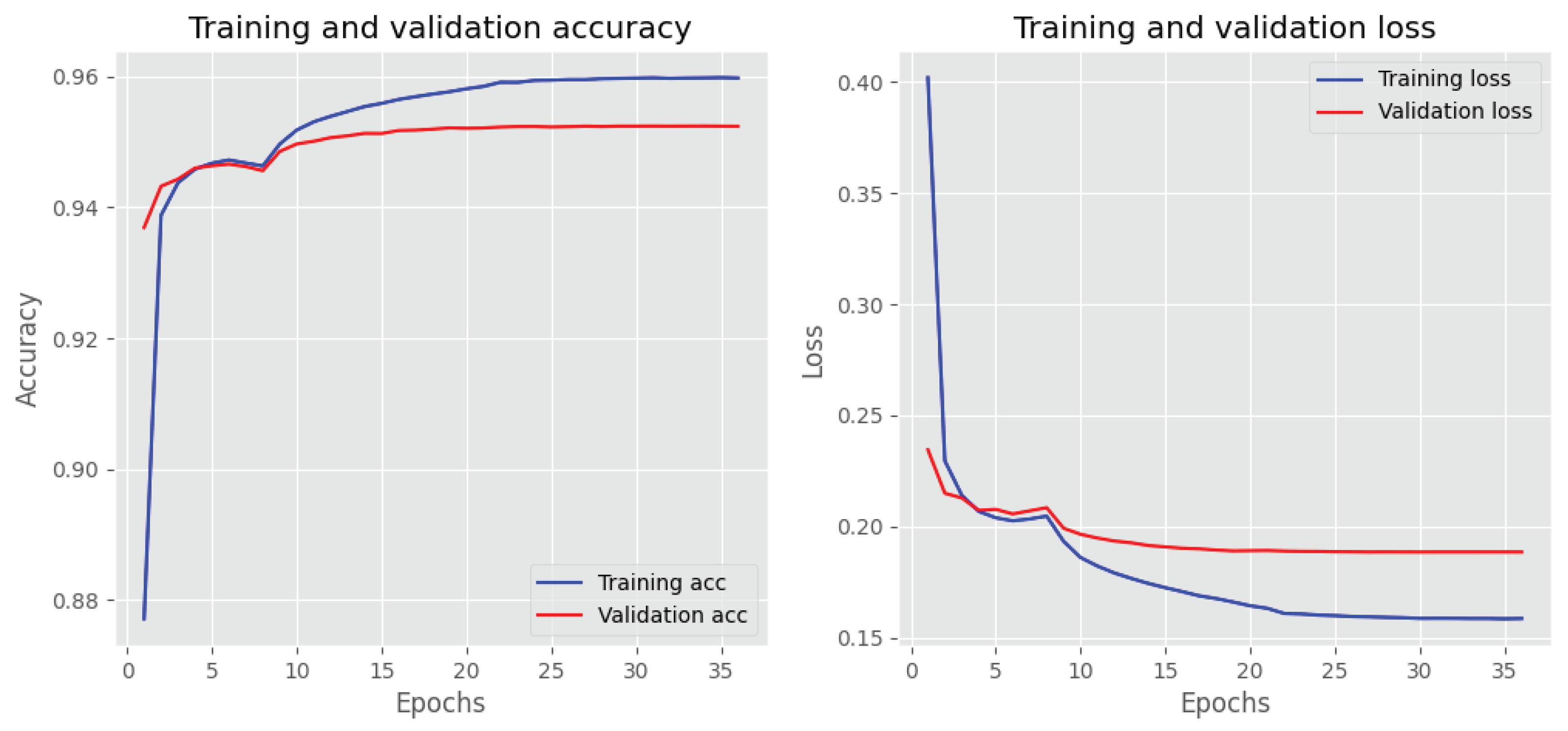

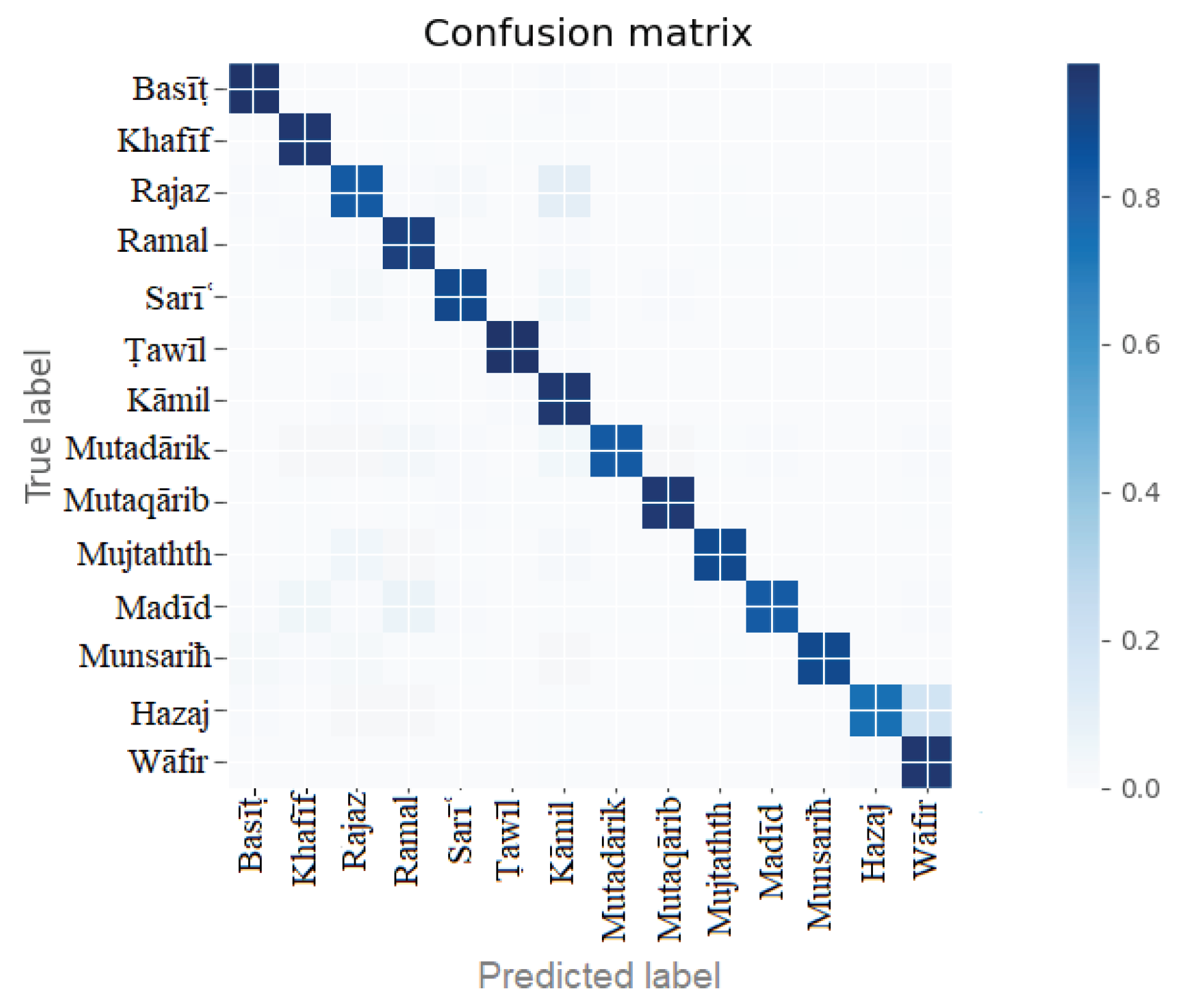

4.2. Training and Testing Using Half-Verse

5. Discussions

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jones, A. Early Arabic Poetry: Select Poems. Available online: https://api.pageplace.de/preview/DT0400.9780863725555_A25858721/preview-9780863725555_A25858721.pdf (accessed on 9 September 2022).

- Alnagdawi, M.; Rashaideh, H.; Aburumman, A. Finding Arabic Poem Meter using Context Free Grammar. Journal of Communications and Computer Engineering 2013, 3, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abandah, G.A.; Suyyagh, A.E.; Abdel-Majeed, M.R. Transfer learning and multi-phase training for accurate diacritization of Arabic poetry. Journal of King Saud University-Computer and Information Sciences 2022, 34, 3744–3757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abandah, G.A.; Khedher, M.Z.; Abdel-Majeed, M.R.; Mansour, H.M.; Hulliel, S.F.; Bisharat, L.M. Classifying and diacritizing Arabic poems using deep recurrent neural networks. Journal of King Saud University-Computer and Information Sciences 2020, 34, 3775–3788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Han, H.; Wang, X.; Sun, S. Research on artificial intelligence enhancing internet of things security: A survey. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 153826–153848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davenport, T.; Kalakota, R. The potential for artificial intelligence in healthcare. Future healthcare journal 2019, 6, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manoharan, S. An improved safety algorithm for artificial intelligence enabled processors in self driving cars. Journal of artificial intelligence 2019, 1, 95–104. [Google Scholar]

- Fietkiewicz, K.; Ilhan, A. Fitness tracking technologies: Data privacy doesn’t matter? The (un) concerns of users, former users, and non-users. Proceedings of the 53rd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gochoo, M.; Tahir, S.B.U.D.; Jalal, A.; Kim, K. Monitoring Real-time Personal Locomotion Behaviors over Smart Indoor-outdoor Environments via Body-Worn Sensors. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 70556–70570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Dey, A.; Pal, A.; Roy, N. Applications of artificial intelligence in machine learning: review and prospect. International Journal of Computer Applications 2015, 115, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeCun, Y.; Bengio, Y.; Hinton, G. Deep learning. nature 2015, 521, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, T.; Qureshi, S. The survey: Text generation models in deep learning. Journal of King Saud University - Computer and Information Sciences 2022, 34, 2515–2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, M.; Paliwal, K.K. Bidirectional recurrent neural networks. IEEE transactions on Signal Processing 1997, 45, 2673–2681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baïna, K.; Moutassaref, H. An Efficient Lightweight Algorithm for Automatic Meters Identification and Error Management in Arabic Poetry. Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Intelligent Systems: Theories and Applications 2020, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albaddawi, M.M.; Abandah, G.A. Pattern and Poet Recognition of Arabic Poems Using BiLSTM Networks. 2021 IEEE Jordan International Joint Conference on Electrical Engineering and Information Technology (JEEIT) 2021, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-shaibani, M.S.; Alyafeai, Z.; Ahmad, I. Meter classification of Arabic poems using deep bidirectional recurrent neural networks. Pattern Recognition Letters 2020, 136, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.A.; Hasan, R.A.; Ali, A.H.; Mohammed, M.A. The classification of the modern arabic poetry using machine learning. Telkomnika 2019, 17, 2667–2674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, A.-Z.A.K.; Elshafei, M. Arabic poetry meter identification system and method. US Patent US Patent No. 8,219,386, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Abuata, B.; Al-Omari, A. A rule-based algorithm for the detection of arud meter in CLASSICAL Arabic poetry. International Arab Journal of Information Technology 2018, 15, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Khalaf, Z.; Alabbas, M.; Ali, S. Computerization of Arabic poetry meters. UOS Journal of Pure & Applied Science 2009, 6, 41–62. [Google Scholar]

- Zeyada, S.; Eladawy, M.; Ismail, M.; Keshk, H. A Proposed System for the Identification of Modem Arabic Poetry Meters (IMAP). 2020 15th International Conference on Computer Engineering and Systems (ICCES) 2020, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Talabani, A.K. Automatic recognition of Arabic poetry meter from speech signal using long short-term memory and support vector machine. ARO-The Scientific Journal of Koya University 2020, 8, 50–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almuhareb, A.; Almutairi, W.A.; Al-Tuwaijri, H.; Almubarak, A.; Khan, M. Recognition of Modern Arabic Poems. Journal of Software. 2015, 10, 454–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkani, A.; Holzer, A.; Stoffel, K. Pattern matching in meter detection of Arabic classical poetry. 2020 IEEE/ACS 17th International Conference on Computer Systems and Applications (AICCSA) 2020, -8, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long short-term memory. Neural computation 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, K.; Van Merriënboer, B.; Gulcehre, C.; Bahdanau, D.; Bougares, F.; Schwenk, H.; Bengio, Y. Learning phrase representations using RNN encoder-decoder for statistical machine translation. Proceedings of the 2014 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP) 2014, 1724–1734. [Google Scholar]

- Dey, R.; Salem, F.M. Gate-variants of gated recurrent unit (GRU) neural networks. 2017 IEEE 60th international midwest symposium on circuits and systems (MWSCAS) 2017, 1597–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, D.; Zhang, Y. AC-BLSTM: asymmetric convolutional bidirectional LSTM networks for text classification. arXiv preprint 2016, arXiv:1611.01884. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z.; Xu, W.; Yu, K. Bidirectional LSTM-CRF models for sequence tagging. arXiv preprint 2015, arXiv:1508.01991 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wazery, Y.M.; Saleh, M.E.; Alharbi, A.; Ali, A.A. Abstractive Arabic Text Summarization Based on Deep Learning. Computational Intelligence and Neuroscience 2022, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, W.; Kann, K.; Yu, M.; Schütze, H. Comparative study of CNN and RNN for natural language processing. arXiv preprint 2017, arXiv:1702.01923 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z.; Xu, W.; Yu, K. Bidirectional LSTM-CRF models for sequence tagging. arXiv preprint 2015, arXiv:1508.01991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Rifai, H.; Al Qadi, L.; Elnagar, A. Arabic text classification: the need for multi-labeling systems. Neural Computing and Applications 2022, 34, 1135–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Wu, L.; Chen, J.; Lu, W.; Ding, J. A comparative study of automated legal text classification using random forests and deep learning. Information Processing & Management 2022, 59, 102798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulghani, F.A.; Abdullah, N.A. A Survey on Arabic Text Classification Using Deep and Machine Learning Algorithms. Iraqi Journal of Science 2022, 409–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqasemi, F.; Salah, A.-H.; Abdu, N.A.A.; Al-Helali, B.; Al-Gaphari, G. Arabic Poetry Meter Categorization Using Machine Learning Based on Customized Feature Extraction. 2021 International Conference on Intelligent Technology, System and Service for Internet of Everything (ITSS-IoE) 2021, -4, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousef, W.A.; Ibrahime, O.M.; Madbouly, T.M.; Mahmoud, M.A. Learning meters of Arabic and English poems with Recurrent Neural Networks: a step forward for language understanding and synthesis. arXiv preprint 2019, arXiv:1905.05700 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sherstinsky, A. Fundamentals of recurrent neural network (RNN) and long short-term memory (LSTM) network. Physica D: Nonlinear Phenomena 2020, 404, 132306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrou, F.; Sun, Y.; Hering, A.S.; Madakyaru, M.; Dairi, A. Chapter 7 - Unsupervised recurrent deep learning scheme for process monitoring. In Statistical Process Monitoring Using Advanced Data-Driven and Deep Learning Approaches; Harrou, F., Sun, Y., Hering, A.S., Madakyaru, M., Dairi, A., Eds.; Elsevier, 2021; pp. 225–253. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Harfiya, L.N.; Purwandari, K.; Lin, Y.-D. Real-Time Cuffless Continuous Blood Pressure Estimation Using Deep Learning Model. Sensors 2020, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. arXiv preprint 2014, arXiv:1412.6980. [Google Scholar]

- Sturm, B.L. Classification accuracy is not enough. Journal of Intelligent Information Systems 2013, 41, 371–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandini, M.; Bagli, E.; Visani, G. Metrics for multi-class classification: an overview. arXiv preprint 2020, arXiv:2008.05756 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tharwat, A. Classification assessment methods. Applied Computing and Informatics 2020, 17, 168–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abadi, M.; Barham, P.; Chen, J.; Chen, Z.; Davis, A.; Dean, J.; Devin, M.; Ghemawat, S.; Irving, G.; Isard, M.; et al. TensorFlow: A system for large-scale machine learning. arXiv 2016, 16, 265–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atassi, A.; El Azami, I. Comparison and generation of a poem in Arabic language using the LSTM, BILSTM and GRU. Journal of Management Information & Decision Sciences 2022, 25, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

| Diacritic | Types | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Harakat | “fatha” “dahmmah” “kasrah” “sukon” | شَرِب الطفْلُ الحليبَ |

| Tanween | Tanween fateh, tanween dham and tanween kasr | بارداً , باردٌ , باردٍ |

| Dhawabet | Shad, mad | الشَّمس , آية |

| Resource | Specification |

|---|---|

| OS | Windows 10, 64-bit |

| RAM | 16 GB |

| CPU | Intel(R) Core (TM) i7-4770K @ 3.50GHz |

| GPU | Nvidia GeForce GTX 1080 Ti, Nvidia Titan V |

| Libraries with version | Python 3.9, Tensorflow 2.7, Scikit-learn 1.0, PyArabic 0.6.14 |

| Models | Hidden layers | Parameters (in millions) | Accuracy | Training Epochs | Training Time (in hours) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSTM | 1 | 0.34 | 0.9720 | 28 | 89.95 |

| 2 | 0.86 | 0.9733 | 26 | 148.17 | |

| 3 | 1.38 | 0.9737 | 35 | 286.15 | |

| GRU | 1 | 0.26 | 0.9710 | 28 | 166.93 |

| 2 | 0.65 | 0.9723 | 37 | 212.63 | |

| 3 | 1.05 | 0.9726 | 60 | 455.93 | |

| BiLSTM | 1 | 0.67 | 0.9698 | 19 | 110.02 |

| 2 | 2.24 | 0.9744 | 26 | 249.97 | |

| 3 | 3.82 | 0.9753 | 25 | 442.50 |

| Meter | Precision | Recall | f1-score | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basit | 0.98 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| Khafif | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.98 |

| Rajaz | 0.94 | 0.93 | 0.94 | 0.93 |

| Ramal | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.96 |

| Sari | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 |

| Tawil | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| Kamil | 0.97 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.98 |

| Mutadarik | 0.91 | 0.90 | 0.91 | 0.90 |

| Mutaqarib | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.98 | 0.97 |

| Mujtathth | 0.91 | 0.95 | 0.93 | 0.95 |

| Madid | 0.91 | 0.90 | 0.91 | 0.90 |

| Munsarih | 0.96 | 0.94 | 0.95 | 0.94 |

| Hazaj | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.80 |

| Wafir | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.98 |

| Models | Hidden layers | Parameters (in millions) | Accuracy | Training Epochs | Training Time (in hours) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSTM | 1 | 0.34 | 0.9465 | 34 | 153.23 |

| 2 | 0.86 | 0.9494 | 24 | 166.08 | |

| 3 | 1.39 | 0.9509 | 28 | 283.33 | |

| GRU | 1 | 0.26 | 0.9455 | 34 | 305.82 |

| 2 | 0.65 | 0.9470 | 34 | 238.78 | |

| 3 | 1.05 | 0.9459 | 60 | 667.97 | |

| BiLSTM | 1 | 0.67 | 0.9446 | 18 | 153.98 |

| 2 | 2.24 | 0.9496 | 33 | 510.00 | |

| 3 | 3.82 | 0.9523 | 36 | 711.05 |

| Meter | Precision | Recall | f1_score | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basit | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.98 |

| Khafif | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.96 |

| Rajaz | 0.88 | 0.83 | 0.85 | 0.83 |

| Ramal | 0.92 | 0.93 | 0.92 | 0.93 |

| Sari | 0.91 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.90 |

| Tawil | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.98 |

| Kamil | 0.94 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.96 |

| Mutadarik | 0.84 | 0.83 | 0.83 | 0.83 |

| Mutaqarib | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.96 |

| Mujtathth | 0.86 | 0.89 | 0.87 | 0.89 |

| Madid | 0.84 | 0.82 | 0.83 | 0.82 |

| Munsarih | 0.93 | 0.89 | 0.91 | 0.89 |

| Hazaj | 0.71 | 0.74 | 0.73 | 0.74 |

| Wafir | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.96 |

| Reference | Technique used | Dataset size | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| [16] | BiGRU-5 | 55,400 verses | 94.32% (full-verse), 88.80% (half-verse) |

| [4] | BiLSTM-4 | 1,657,003 verses | 97.00% (full-verse) |

| [37] | BiLSTM-7 | 1,722,321 verses | 96.38% (full-verse) |

| Our Proposed work | BiLSTM-3 | 1,646,771 verses | 97.53% (full-verse), 95.23% (half-verse) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).