Submitted:

27 February 2024

Posted:

04 March 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

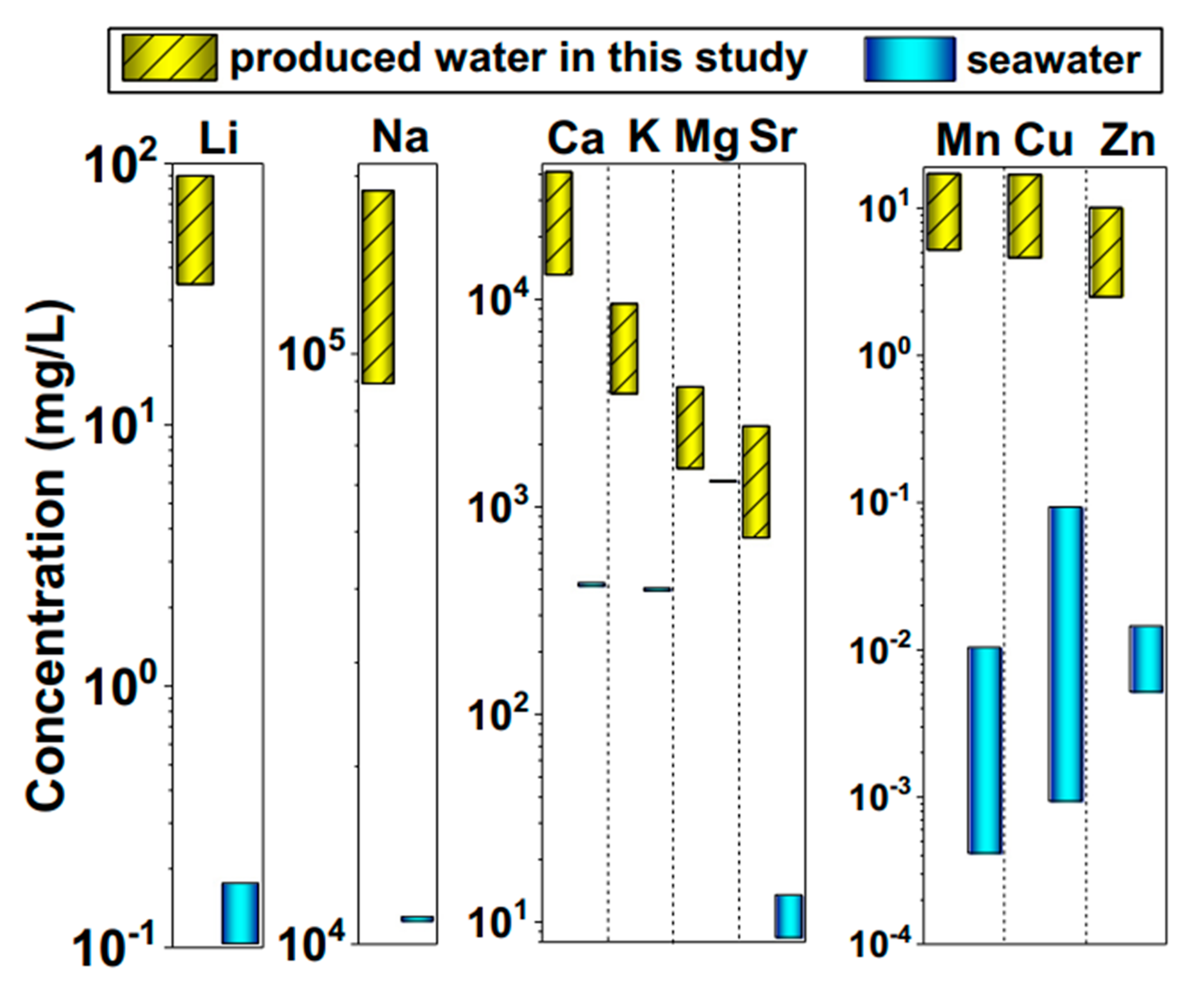

2.1. Characterization of Bakken Oilfield Produced Water

2.2. Experiments

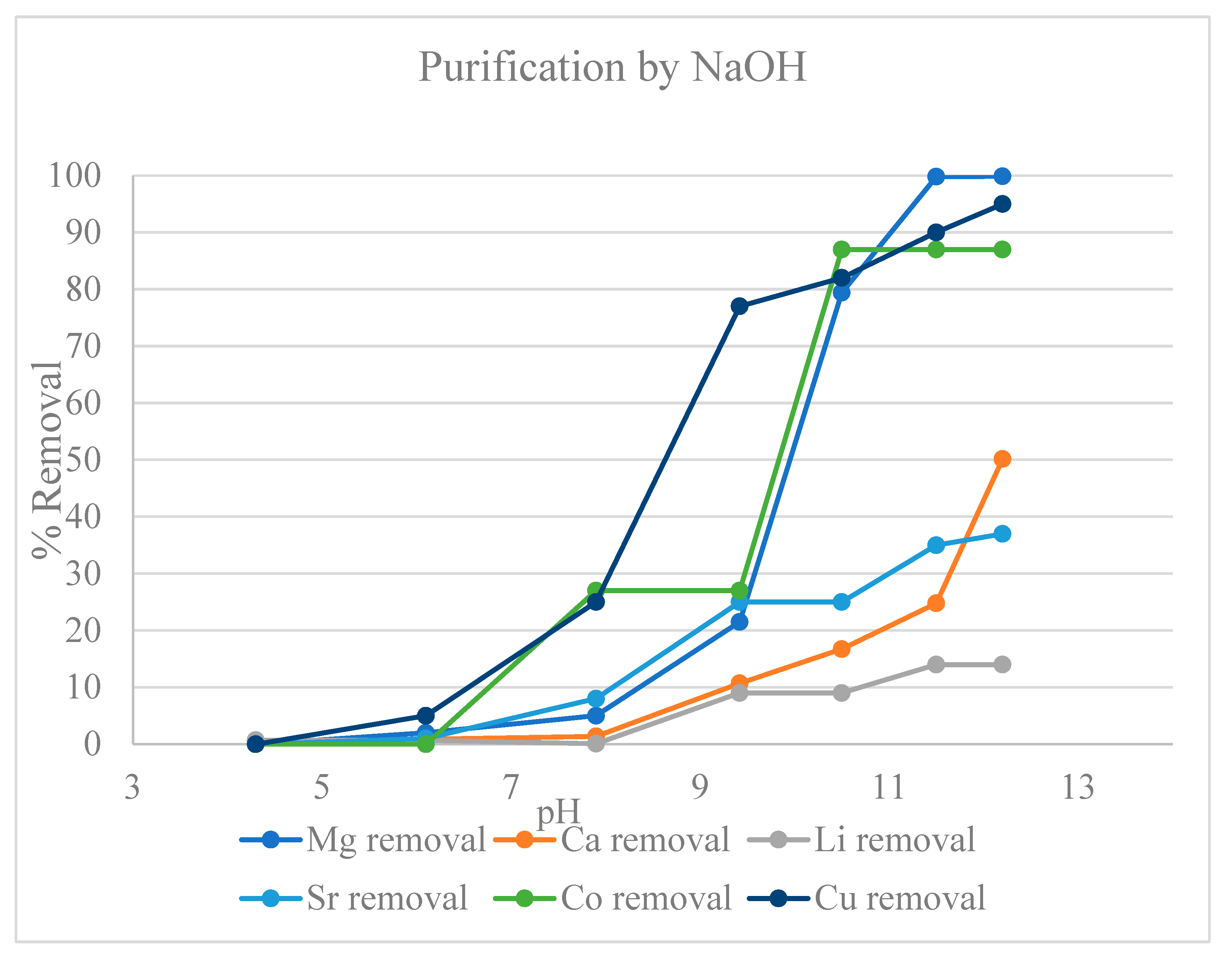

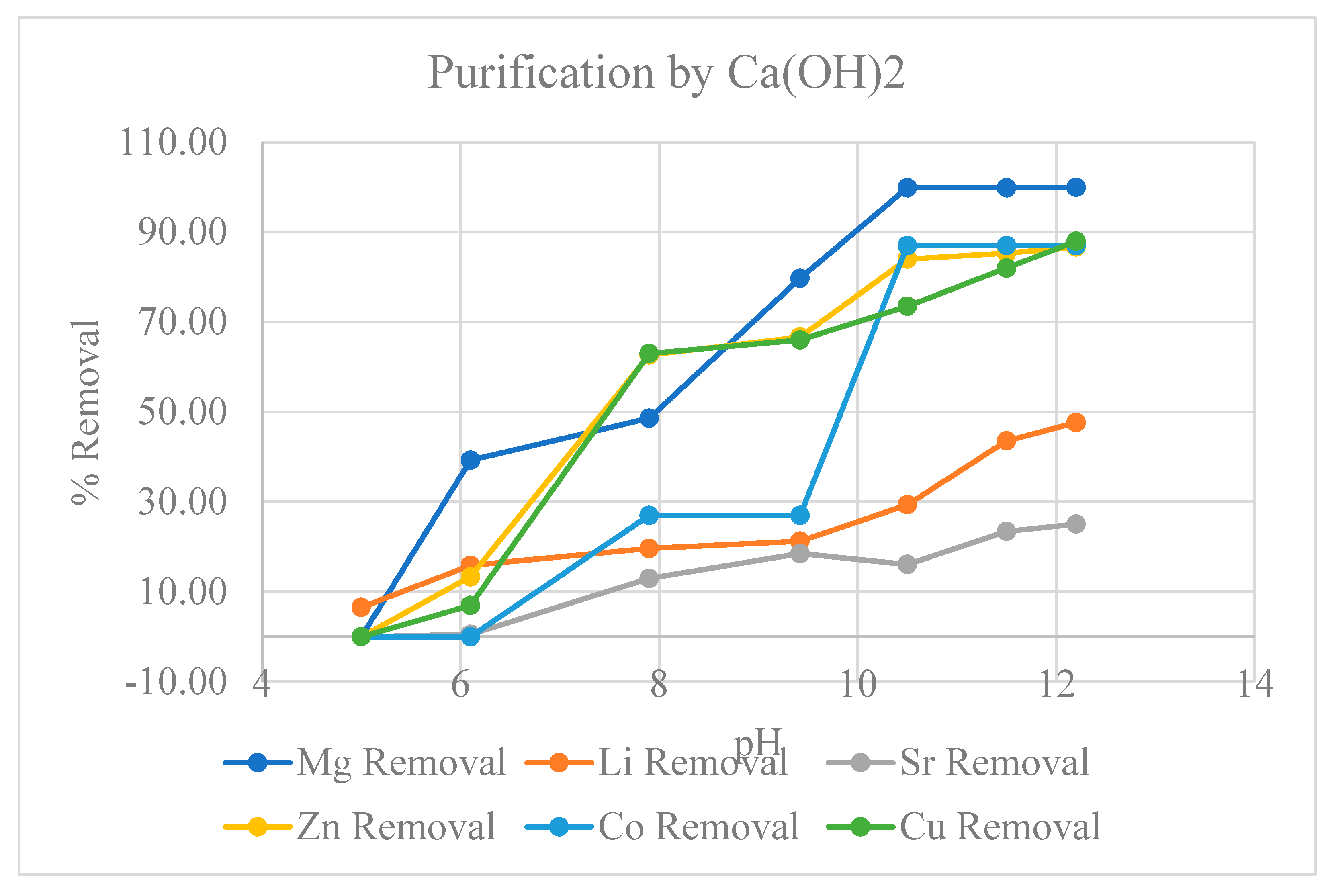

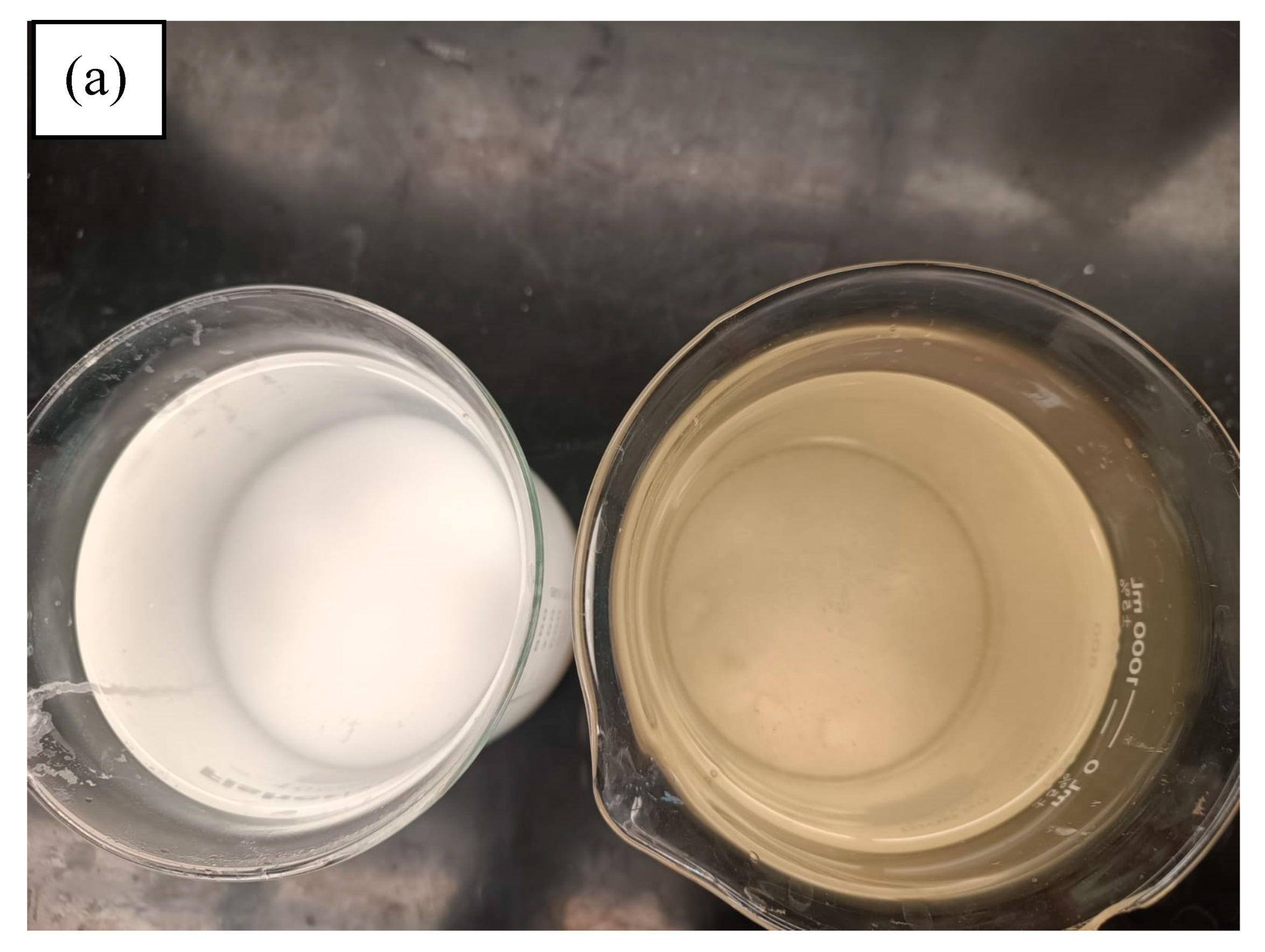

2.2.1. Precipitative Softening of Produced Water

2.2.3. Precipitative Lithium of Produced Water

3. Results

3.1. Metal Ion Extraction from Produced Water

3.2. Lithium Enrichment

4. Conclusion

References

- Aaldering, L.J.; Song, C.H. Tracing the technological development trajectory in post-lithium-ion battery technologies: A patent-based approach. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2019, 241, 118343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajao, A.; Lim, Y.H. (2023). Sustainable Management of Dams and Reservoirs in North Dakota: Sediment Transport Characterization.

- Aljarrah, S.; Alsabbagh, A.; Almahasneh, M. (2023). Selective recovery of lithium from Dead Sea end brines using UBK10 ion exchange resin. The Canadian Journal of Chemical Engineering, 101(3), 1185-1194. [CrossRef]

- Almousa, M.; Olusegun, T.; Lim, Y.; Al-Zboon, K.; Khraisat, I.; Alshami, A.; Ammary, B. "Chemical recovery of magnesium from the Dead Sea and its use in wastewater treatment." Journal of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene for Development (2024): washdev2024267. [CrossRef]

- U.S. EPA (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency).

- Almousa, M.; Olusegun, T.S.; Lim, Y.H.; Khraisat, I.; Ajao, A. . "Groundwater Management Strategies for Handling Produced Water Generated Prior Injection Operations in the Bakken Oilfield." In ARMA/DGS/SEG International Geomechanics Symposium, pp. ARMA-IGS. ARMA, 202.

- Almousa, M.; Lim, Y.H. "Salts Removal as an Effective and Economical Method of Bakken Formation Treatment" (2023). Civil Engineering Posters and Presentations https://commons.und.edu/cie-pp/1.

- Daitch, P.J. Lithium Extraction from Oilfield Brine. Master’s Thesis, The University of Texas at Austin, 2018.

- Disu, B.; Rafati, R.; Haddad, A.S.; Fierus, N. (2023, September). Lithium Extraction From North Sea Oilfield Brines Using Ion Exchange Membranes. In SPE Offshore Europe Conference and Exhibition (p. D021S004R001). SPE.

- Flexer, V.; Baspineiro, C.F.; Galli, C.I. (2018). Lithium recovery from brines: A vital raw material for green energies with a potential environmental impact in its mining and processing. Science of the Total Environment, 639, 1188-1204. [CrossRef]

- Gregory, K.B.; Vidic, R.D.; Dzombak, D.A. Water management challenges associated with the production of shale gas by hydraulic fracturing. Elements 2011, 7, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Fukuda, H.; Hatton, T.A.; Lienhard, J.H. (2019). Lithium recovery from oil and gas produced water: a need for a growing energy industry. ACS Energy Letters, 4, 1471-1474. [CrossRef]

- Lai, X.; Xiong, P.; Zhong, H. (2020). Extraction of lithium from brines with high Mg/Li ratio by the crystallization-precipitation method. Hydrometallurgy, 192, 105252. [CrossRef]

- Massari, S.; Ruberti, M. (2013). Rare earth elements as critical raw materials: Focus on international markets and future strategies. Resources Policy, 38(1), 36-43. [CrossRef]

- Mauk, J.L.; Karl, N.A.; San Juan, C. A. , Knudsen, L., Schmeda, G., Forbush, C.,... & Scott, P. (2021). The critical minerals initiative of the US geological survey’s mineral deposit database project: USMIN. Mining, Metallurgy & Exploration, 38(2), 775-797. [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Jing, Y.; Xiao, J.; Wang, X.; Yao, Y.; Jia, Y. (2017). Solvent extraction of lithium from aqueous solution using non-fluorinated functionalized ionic liquids as extraction agents. Separation and Purification Technology, 172, 473-479. [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, N.; Chilkoor, G.; Wilder, J.; Gadhamshetty, V.; Stone, J.J. 2017. Potential water resource impacts of hydraulic fracturing from unconventional oil production in the Bakken shale. Water Res. 108, 1–24. [CrossRef]

- Somrani AA, H.H.; Hamzaoui, A.H.; Pontie, M. (2013). Study on lithium separation from salt lake brines by nanofiltration (NF) and low pressure reverse osmosis (LPRO). Desalination. [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Zhao, Z. (2018). Recovery of lithium from spent lithium-ion batteries using precipitation and electrodialysis techniques. Separation and Purification Technology, 206, 335-342. [CrossRef]

- Talens Peiró, L. , Villalba Méndez, G., & Ayres, R. U. (2013). Lithium: Sources, production, uses, and recovery outlook. Jom, 65, 986-996. [CrossRef]

- Tandy, S. , Caniy, Z., 1993. LITHIUM PRODUCTION FROM HIGHLY SALINE DEAD SEA BRINES. Rev. Chem. Eng. 9, 293–318. [CrossRef]

- Torres, L. , Yadav, O.P., Khan, E., 2016. A review on risk assessment techniques for hydraulic fracturing water and produced water management implemented in onshore unconventional oil and gas production. Sci. Total Environ. 539, 478–493. [CrossRef]

- USGS, 2020a. Data on the domestic production and use of Li. https://pubs.usgs.gov/periodicals/mcs2020/mcs2020-lithium.

- Valdez, S. K. , Flores, H. R., & Orce, A. (2016). Influence of the evaporation rate over lithium recovery from brines.

- Virolainen, S. , Fini, M. F., Miettinen, V., Laitinen, A., Haapalainen, M., & Sainio, T. (2016). Removal of calcium and magnesium from lithium brine concentrate via continuous counter-current solvent extraction. Hydrometallurgy. [CrossRef]

- Waisi, B. I. H. Karim, U. F., Augustijn, D. C., Al-Furaiji, M. H. O., & Hulscher, S. J. (2015). A study on the quantities and potential use of produced water in southern Iraq. Water science and technology: water supply, 15(2), 370-376. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. , Zhong, Y., Du, B., Zhao, Y., & Wang, M. (2018). Recovery of both magnesium and lithium from high Mg/Li ratio brines using a novel process. Hydrometallurgy, 175, 102-108. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Ye, Yuehua Hu, Li Wang, and Wei Sun. "Systematic review of lithium extraction from salt-lake brines via precipitation approaches." Minerals Engineering 139 (2019): 105868. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z. , Si, X., Liu, X., He, L., & Liang, X. (2013). Li extraction from high Mg/Li ratio brine with LiFePO4/FePO4 as electrode materials. Hydrometallurgy, 133, 75-83. [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J. , Lin, S., & Yu, J. (2021). Li+ adsorption performance and mechanism using lithium/aluminum layered double hydroxides in low grade brines. Desalination, 505, 114983. [CrossRef]

| Results | |||

| Parameters | Units | PW1 | PW2 |

| pH | - | 4.5 | 5.2 |

| Conductivity | mS/cm | 98 | 135 |

| Alkalinity | (mg/L as CaCO3) | 140 | 120 |

| Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD) | mg/L | 380 | 120 |

| Suspended Solids (TSS) | mg/L | 220 | 180 |

| Total Organic Carbon (TOC) | mg/L | 11 | 4 |

| Color | - | Clear yellow | Clear yellow |

| Odor | - | significant | Not significant |

| Chloride | mg/L | 76,300 | 39,561 |

| Sulfate | mg/L | 2.5 | 0.3 |

| Lithium (Li) | mg/L | 53.5 | 22 |

| Calcium (Ca) | mg/L | 11,580 | 3221 |

| Magnesium (Mg) | mg/L | 1070 | 305 |

| Sodium (Na) | mg/L | 43,250 | 11,750 |

| Iron( Fe) | mg/L | 1.1 | 0 |

| Strontium (Sr) | mg/L | 1317 | 249 |

| Manganese (Mn) | mg/L | 0.8 | 0 |

| Aluminium (Al) | mg/L | 0.23 | 0 |

| pH | Temperature °C | Li (mg/l) | Mg (mg/l) | Ca (mg/l) | |

| Actual sample | 4.5 | 23 | 53.6 | 1070 | 11580 |

| Purification process (NaOH addition) | 11.5 | 23 | 52.1 | 1.2 | 6240 |

| DSP (2g) | 45 | 0 | - | ||

| STP (2g) | 10.45 | 50 | 41.2 | 0 | - |

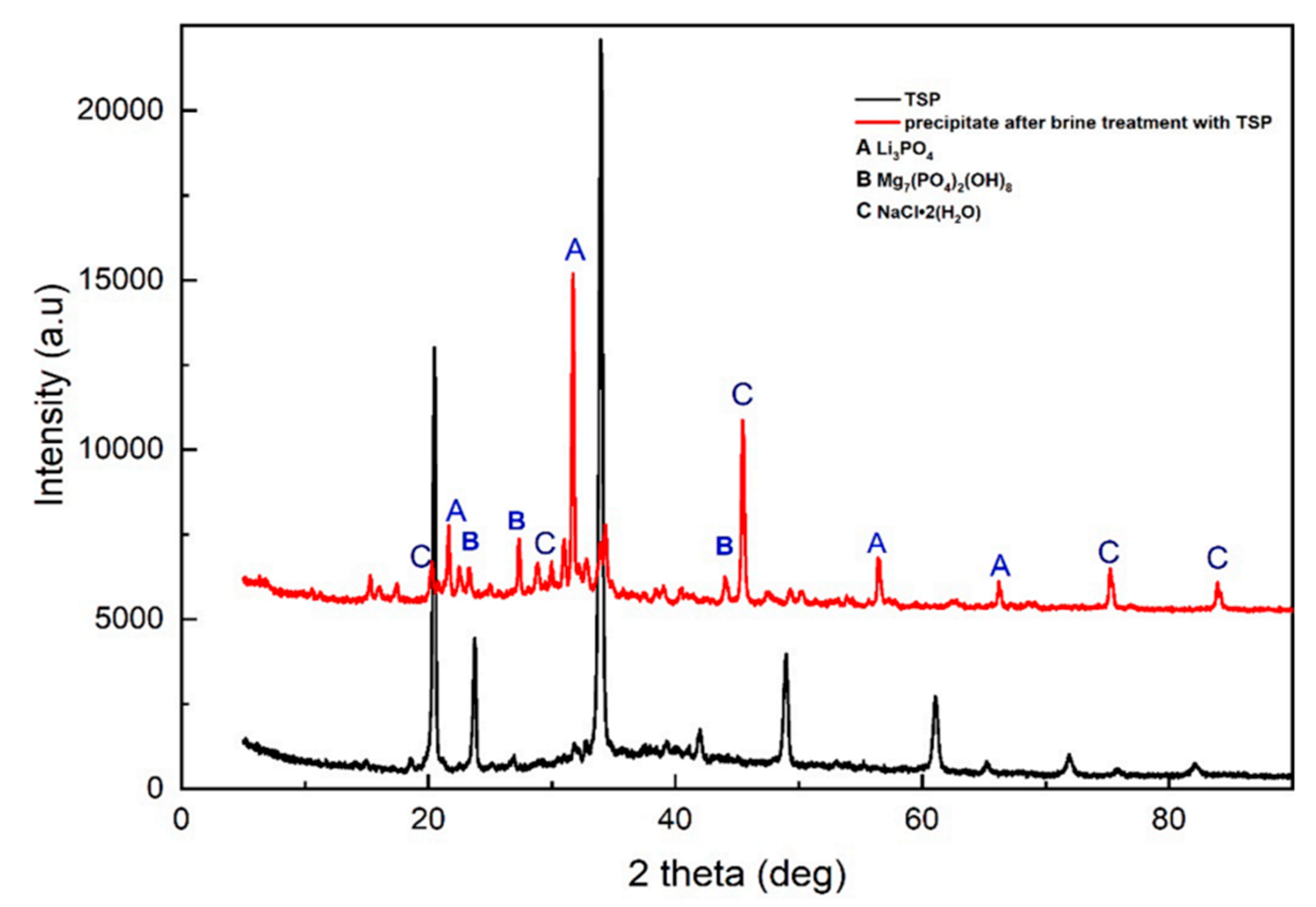

| TSP (2g) | 39.2 | 0 | - | ||

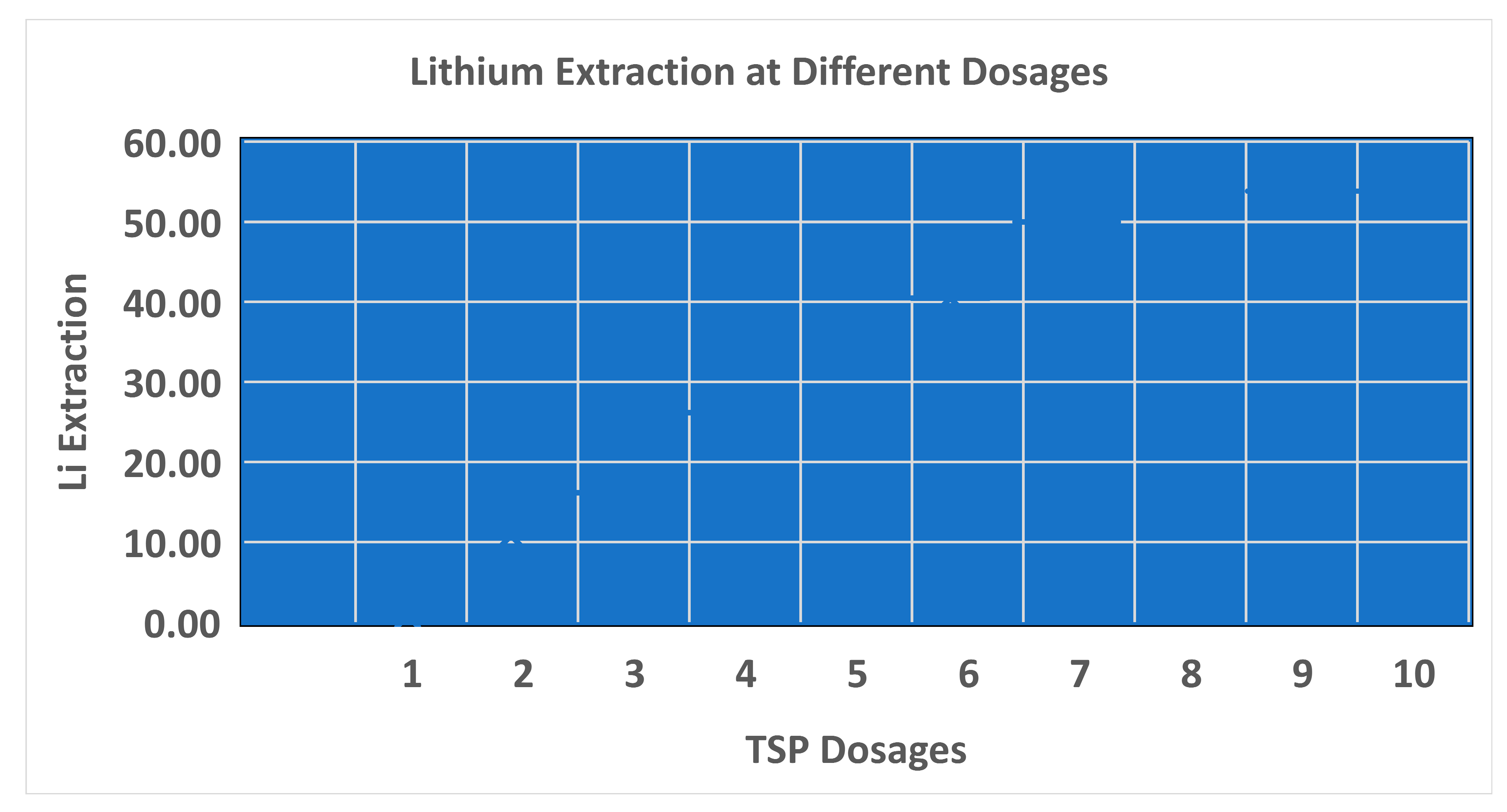

| Selected reagent (TSP)(TSP=5, 7, 10, 15 g) dosage | 11 | 50 | (37.5-39) | 0 | - |

| TSP (10g) | 10.5 | (50,60,80) | (40.5-42.7) | 0 | - |

| Removal% | 25% | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).