Submitted:

02 March 2024

Posted:

04 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

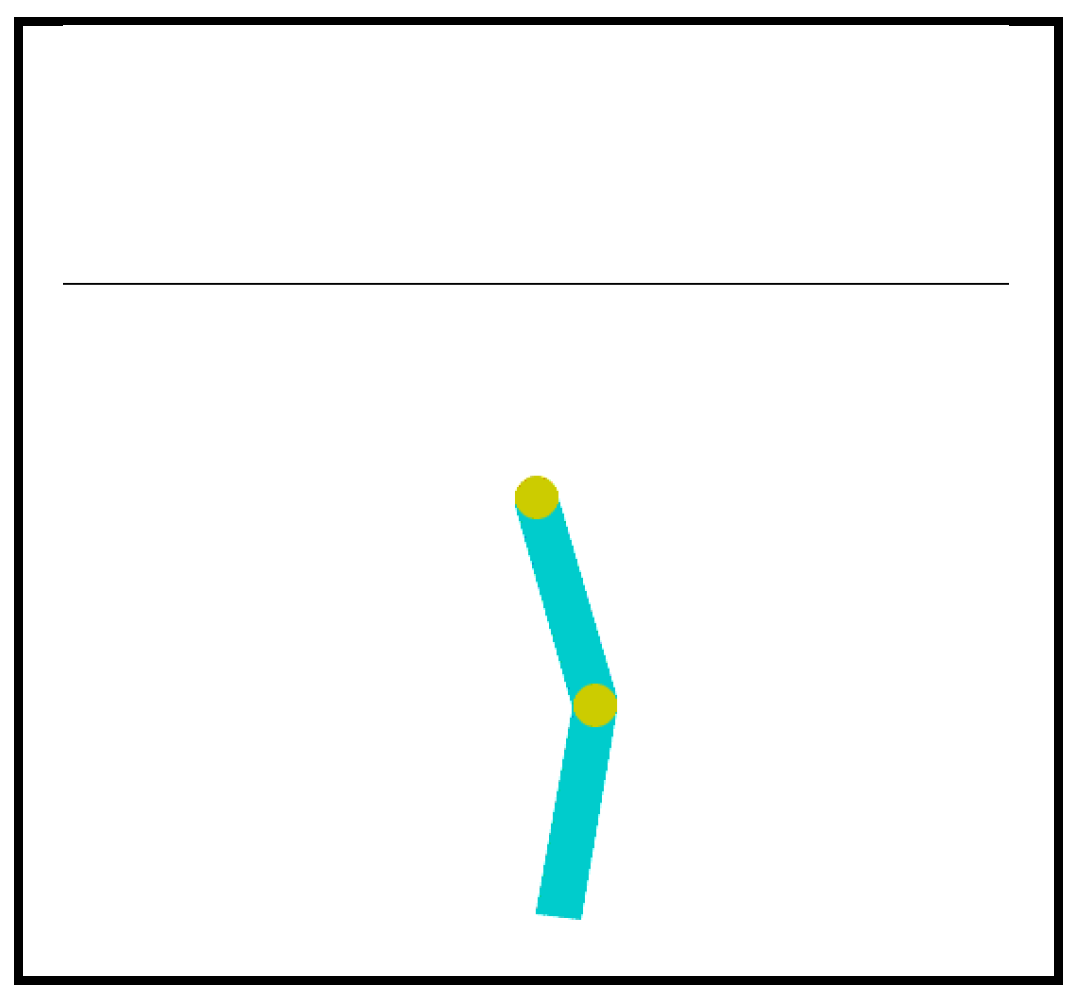

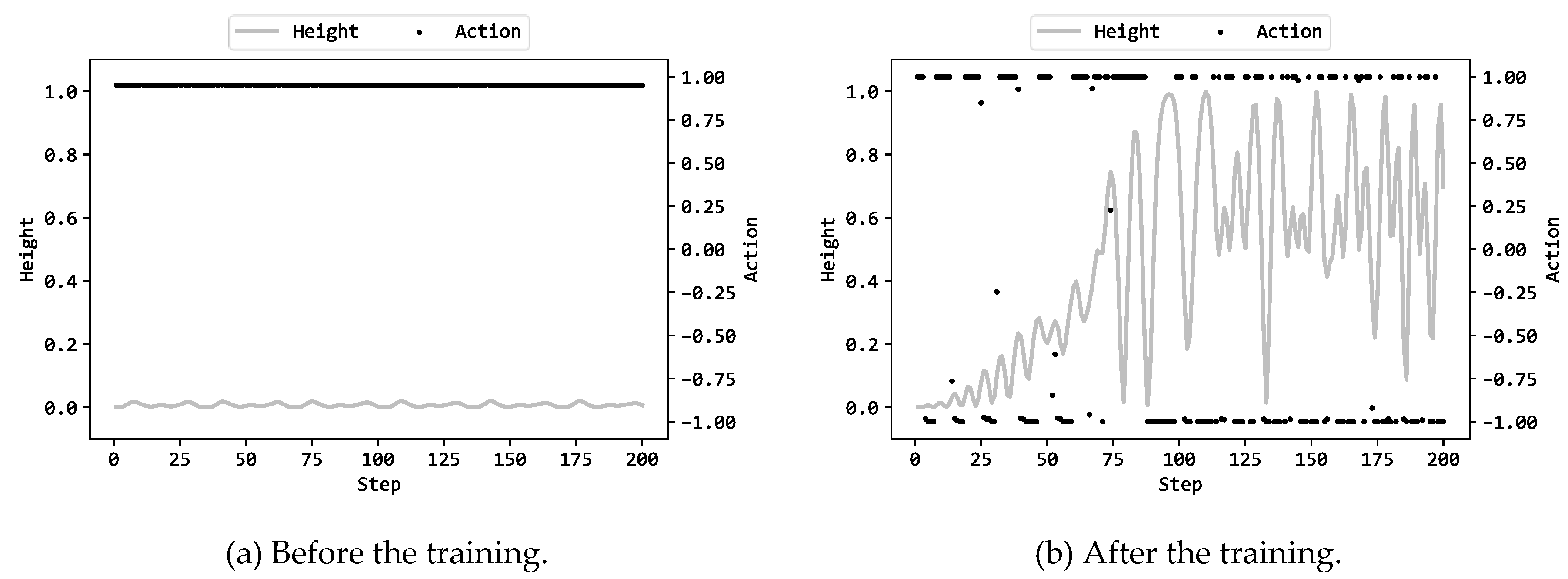

2. Acrobot Control Task

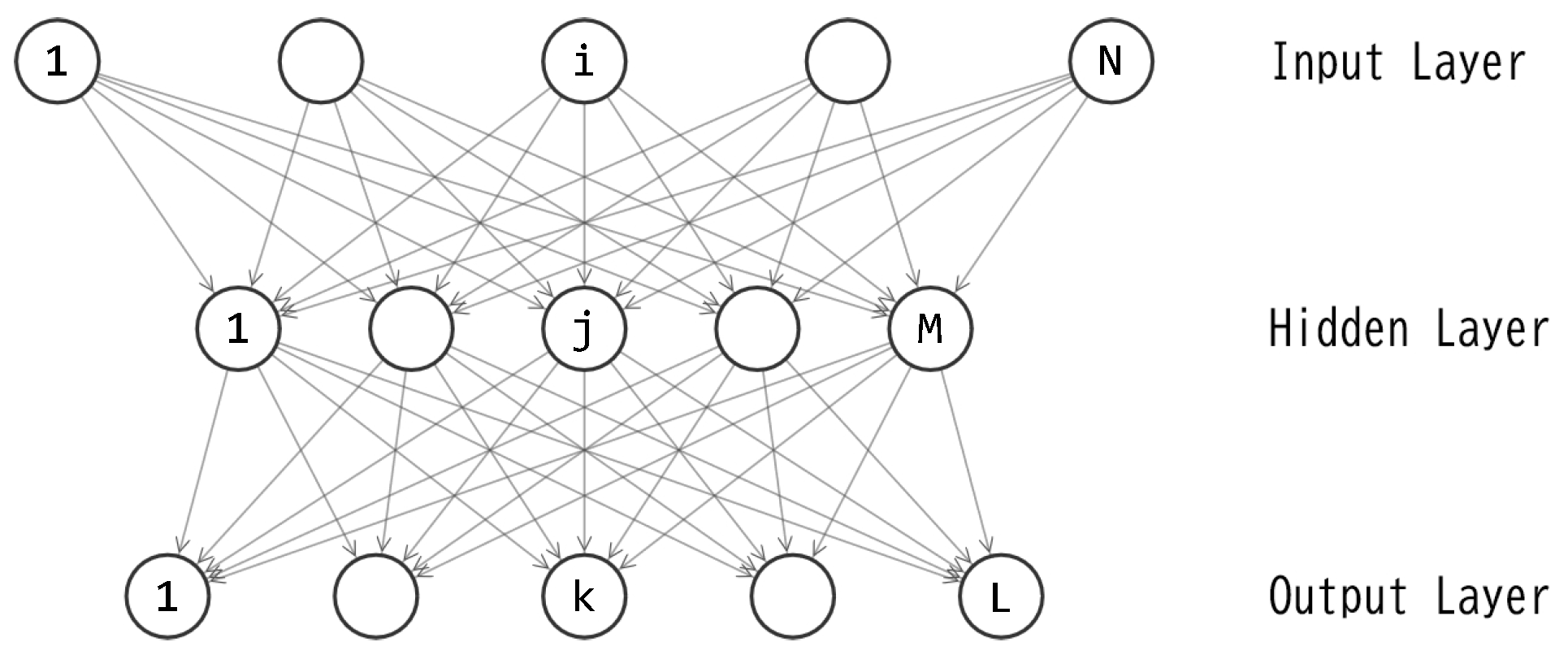

3. Neural Networks

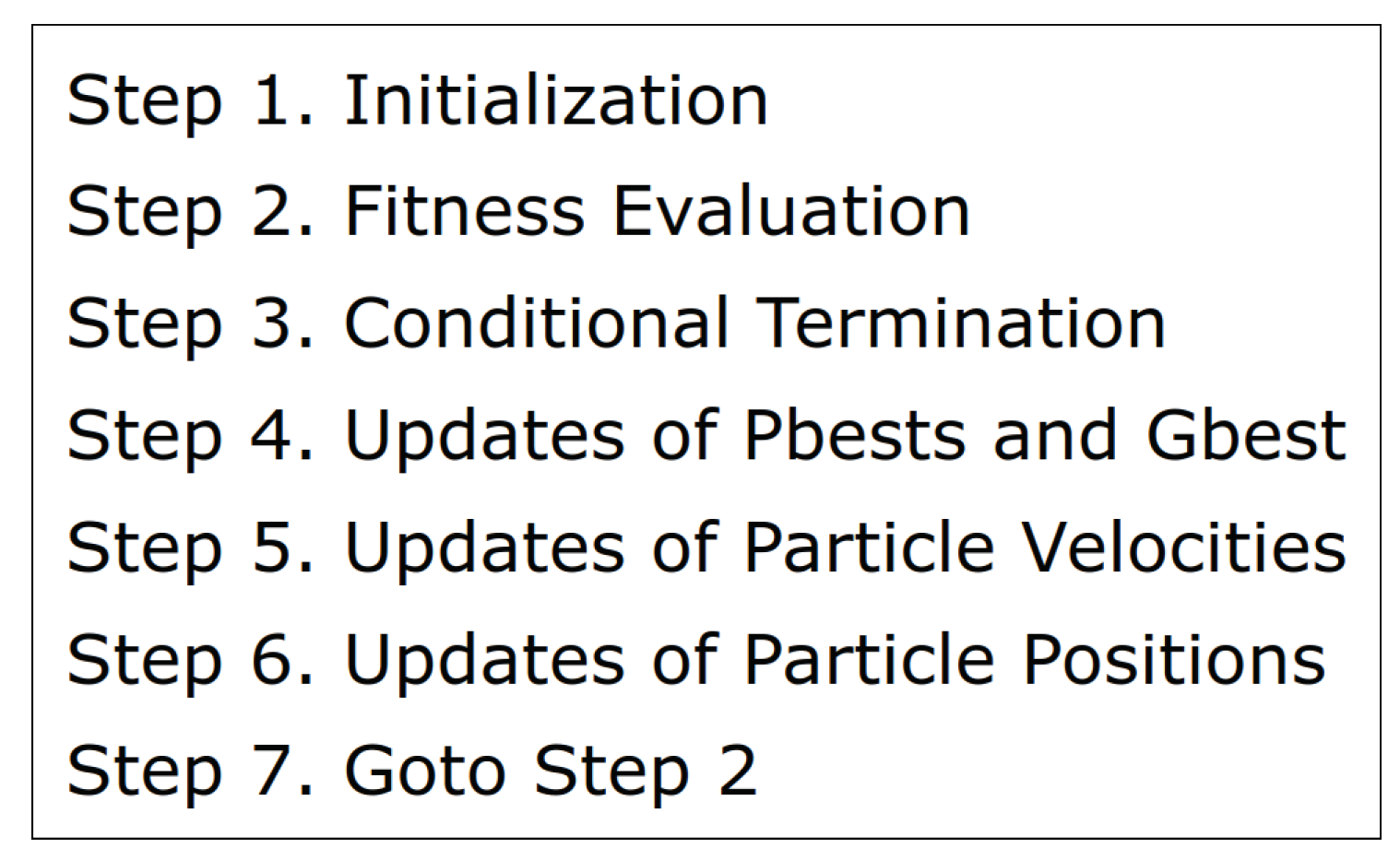

4. Training of Neural Networks by Particle Swarm Optimization

5. Experiment

6. Statistical Test to Compare Pso with De, Ga, And Es

7. Conclusion

- (1)

- The statistical tests revealed that PSO performed worse than all of DE, GA and ES. The difference between PSO and DE was statistically significant (p<.01).

- (2)

- The experiment in this study employed two configurations, which are consistent with the previous studies reported in Part1-3: maintaining a fixed number of 5000 fitness evaluations, (a) a greater number of particles, suitable for early-stage global exploration, and (b) a greater number of iterations, suitable for late-stage local exploitation. A comparative analysis of the results revealed that configuration (b) contributed significantly better than configuration (a). Configuration (b) can compensate for the limited capability of PSO in global exploration, thus making itself more beneficial than configuration (a). This result is consistent with the previous study in which ES was adopted [29].

- (3)

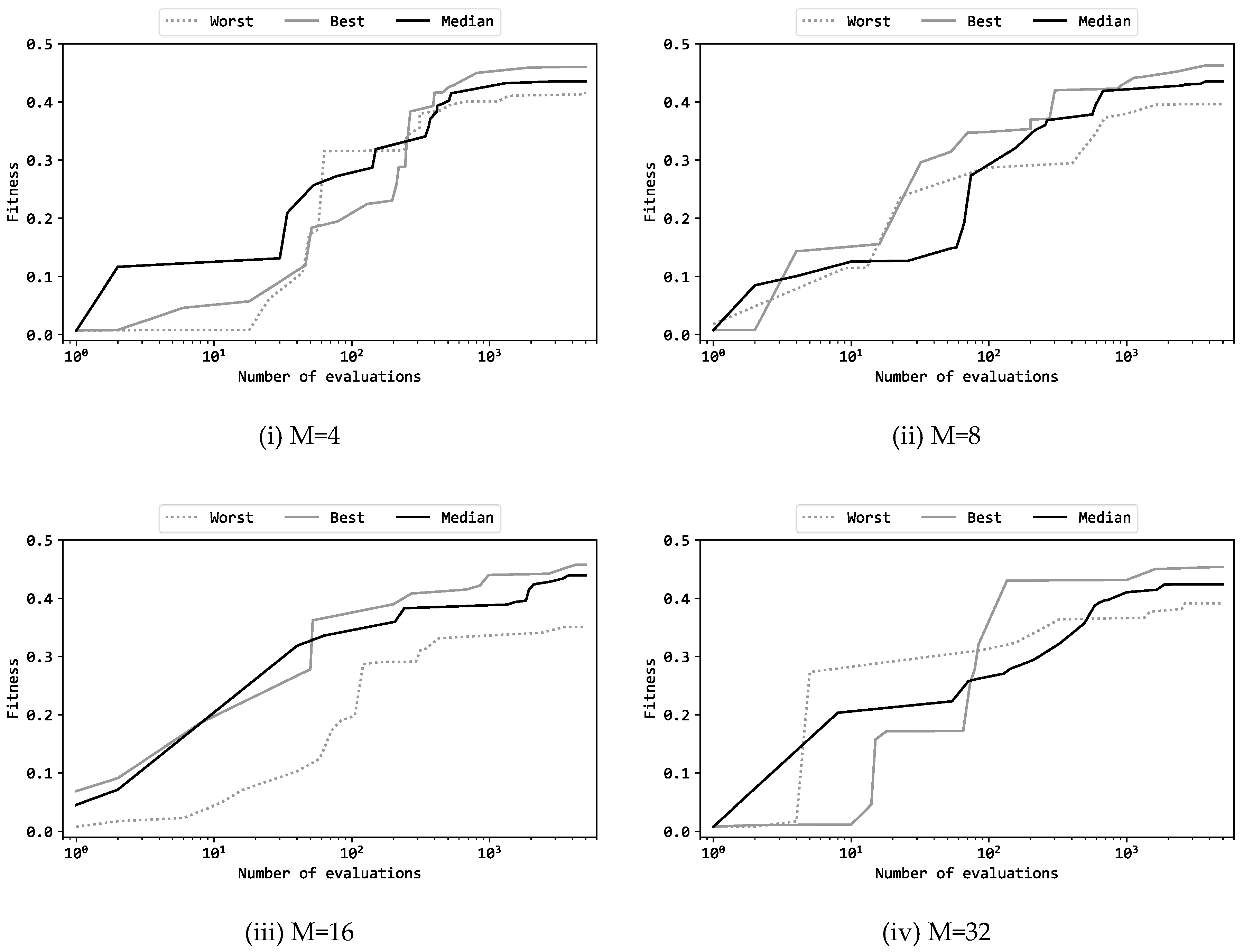

- Four different numbers of units in the hidden layer of the multilayer perceptron were compared: 4, 8, 16, and 32. The experimental results revealed that 4 units were found to be the optimal choice from the perspective of the trade-off between performance and model size. This result does not align with previous studies: 8 units were the best in the cases of DE, GA, and ES. PSO exhibited lower capability in exploring solutions in high-dimensional search spaces than DE, GA, and ES did.

Acknowledgments

References

- Bäck, T.; Schwefel, H.P. An overview of evolutionary algorithms for parameter optimization. Evolutionary computation 1993, 1, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogel, D.B. An introduction to simulated evolutionary optimization. IEEE transactions on neural networks 1994, 5, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bäck, T. Evolutionary algorithms in theory and practice: evolution strategies, evolutionary programming, genetic algorithms. Oxford university press, 1996.

- Eiben, Á.E.; Hinterding, R.; Michalewicz, Z. Parameter control in evolutionary algorithms. IEEE transactions on evolutionary computation 1999, 3, 124–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eiben, Á.E.; Smith, J.E. Introduction to evolutionary computing. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg, 2015.

- Bari, A.; Zhao, R.; Pothineni, J.S.; Saravanan, D. Swarm intelligence algorithms and applications: an experimental survey. Advances in swarm intelligence, ICSI 2023, Lecture notes in computer science, 13968, Springer, 2023.

- Tang, J.; Liu, G.; Pan, Q. A review on representative swarm intelligence algorithms for solving optimization problems: applications and trends. IEEE/CAA journal of automatica sinica 2021, 8, 1627–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavrovouniotis, M.; Li, C.; Yang, S. A survey of swarm intelligence for dynamic optimization: algorithms and applications. Swarm and evolutionary computation 2017, 33, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payal, M.; Kumar, A.; Díaz, V.G. A fundamental overview of different algorithms and performance optimization for swarm intelligence. Swarm intelligence optimization: algorithms and applications 2020, 1-19.

- Chu, SC.; Huang, HC.; Roddick, J.F.; Pan, JS.. Overview of algorithms for swarm intelligence. Computational collective intelligence, technologies and applications. ICCCI 2011. Lecture notes in computer science, 6922, Springer, 2011.

- Kennedy, J.; Eberhart, R. Particle swarm optimization. Proceedings of ICNN’95 - International conference on neural networks 1995, 4, 1942–1948. [Google Scholar]

- Eberhart, R.; Kennedy, J. A new optimizer using particle swarm theory. MHS’95. Proceedings of the sixth international symposium on micro machine and human science 1995, 39-43.

- Shi, Y.; Eberhart, R. A modified particle swarm optimizer. IEEE international conference on evolutionary computation proceedings 1998, 69–73. [Google Scholar]

- Dorigo, M.; Maniezzo, V.; Colorni, A. Ant system: optimization by a colony of cooperating agents. IEEE transactions on systems, man, and cybernetics, part b (cybernetics), 1996, 26, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorigo, M.; Gambardella, L.M. Ant colony system: a cooperative learning approach to the traveling salesman problem. IEEE Transactions on evolutionary computation 1997, 1, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaboga, D.; Basturk, B. Artificial bee colony (ABC) optimization algorithm for solving constrained optimization problems. International fuzzy systems association world congress 2007, 789–798. [Google Scholar]

- Karaboga, D.; Basturk, B. A powerful and efficient algorithm for numerical function optimization: artificial bee colony (ABC) algorithm. Journal of global optimization 2007, 39, 459–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.S.; Deb, S. Cuckoo search via Lévy flights. IEEE world congress on nature & biologically inspired computing 2009, 210-214.

- Yang, X.S.; Deb, S. Engineering optimisation by cuckoo search. International journal of mathematical modelling and numerical optimisation 2010, 1, 330–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwefel, H.P. Evolution strategies: A family of non-linear optimization techniques based on imitating some principles of organic evolution. Annals of operations research 1984, 1, 165–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyer, H.G.; Schwefel, H.P. Evolution strategies – a comprehensive introduction. Natural computing 2002, 1, 3–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, D.E.; Holland, J.H. Genetic algorithms and machine learning. Machine learning 1988, 3, 95–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, J.H. Genetic algorithms. Scientific American 1992, 267, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, M. An introduction to genetic algorithms. MIT press, 1998.

- Sastry, K.; Goldberg, D.; Kendall, G. Genetic algorithms. Search methodologies: introductory tutorials in optimization and decision support techniques 2005, 97-125.

- Storn, R.; Price, K. Differential evolution – a simple and efficient heuristic for global optimization over continuous spaces. Journal of global optimization 1997, 11, 341–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, K.; Storn, R.M.; Lampinen, J.A. Differential evolution: a practical approach to global optimization. Springer science & business media, 2006.

- Das, S.; Suganthan, P.N. Differential evolution: a survey of the state-of-the-art. IEEE transactions on evolutionary computation 2010, 15, 4–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, H. Evolutionary reinforcement learning of neural network controller for Acrobot task – Part1: evolution strategy. Preprints.org 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, H. Evolutionary reinforcement learning of neural network controller for Acrobot task – Part2: genetic algorithm. Preprints.org 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, H. Evolutionary reinforcement learning of neural network controller for Acrobot task – Part3: differential evolution. Preprints.org 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumelhart, D.E.; Hinton, G.E.; Williams, R.J. Learning internal representations by error propagation. Parallel distributed processing: explorations in the microstructure of cognition 1986, vol.1: foundations. MIT Press, 318-362.

- Collobert, R.; Bengio, S. Links between perceptrons, MLPs and SVMs. Proceedings of the twentyfirst international conference on machine learning (ICML 04), 2004. [CrossRef]

- Eberhart, R.C.; Shi, Y. Comparing inertia weights and constriction factors in particle swarm optimization. Proceedings of the 2000 congress on evolutionary computation (CEC00) 2000, 1, 84–88. [Google Scholar]

- Bonyadi, M.R.; Michalewicz, Z. Analysis of stability, local convergence, and transformation sensitivity of a variant of the particle swarm optimization algorithm. IEEE transactions on evolutionary computation 2015, 20, 370–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Hyperparameters | (a) | (b) |

|---|---|---|

| Number of particles () | 10 | 50 |

| Iterations | 500 | 100 |

| Fitness evaluations | 10500=5,000 | 50100=5,000 |

| Inertia weights (w) | 0.729 | 0.729 |

| Pbest coefficient (cp) | 1.49445 | 1.49445 |

| Gbest coefficient (cg) | 1.49445 | 1.49445 |

| M | Best | Worst | Average | Median | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (a) | 4 | 0.469 | 0.336 | 0.408 | 0.417 |

| 8 | 0.450 | 0.269 | 0.401 | 0.435 | |

| 16 | 0.467 | 0.333 | 0.424 | 0.439 | |

| 32 | 0.465 | 0.314 | 0.418 | 0.425 | |

| (b) | 4 | 0.460 | 0.416 | 0.440 | 0.436 |

| 8 | 0.463 | 0.396 | 0.437 | 0.436 | |

| 16 | 0.458 | 0.351 | 0.429 | 0.439 | |

| 32 | 0.453 | 0.391 | 0.425 | 0.424 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).