1. Introduction

Lung cancer is one of the leading cause of mortality among women and men, accounting for over 1.8 millions deaths worldwide per year [

1]. Treatment options and recommendations depend on cancer type, clinical stage and patient specific factors, and may include surgery, chemotherapy, radiation, targeted therapy, as well as, a combination of these methods [

2].

Pulmonary lobectomy is the most frequent surgical procedure for operable lung cancer. Method of lobe resection is mainly considered between two approaches: conventional open thoracotomy and video-assissted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS). In recent years, most of studies demonstrated that minimal invasive lobectomy has substantial advantages over standard thoracotomy for early stage of non-small cell lung cancer regarding its safety, feasibility, better quality of life, faster time to return to work, as well as, lower mortality rates, lesser blood loss during operation, decrease of postoperative pain, reduced analgesic intake, less postoperative shoulder dysfunction, shorter length of hospital stay and chest tube drainage [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. However, despite a growing number of evidence it is still not known whether VATS, due to its minimally invasive approach, allow to preserve better postoperative diaphragm muscle function compared to open thoracotomy. Many previous studies, which investigated diaphragm after pulmonary resection, indicate to a numerous postoperative disorders including reduction of active diaphragmatic contractility [

12], decrease of maximal transdiaphragmatic pressure [

13], increase of intercostal and accessory breathing muscles recruitment [

14], but the vast majority of this research were conducted on either VATS or thoracotomy population. In fact, only three papers compared this two approaches in range of this main breathing muscle working [

15,

16,

17]. However, these items have some limitations and not fully explored this issue. Given the above, we conducted this study to fill the gap in existing literature.

The purpose of the present study was to comprehensively assess the diaphragm muscle function parameters at early postoperative stage among patients undergone lobectomy via video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery or standard thoracotomy, as well as, to investigate the frequency of occurrence the postoperative diaphragm muscle dysfunction in each of two approaches for early stage non-small cell lung cancer.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants Selection Process and Eligibility Criteria

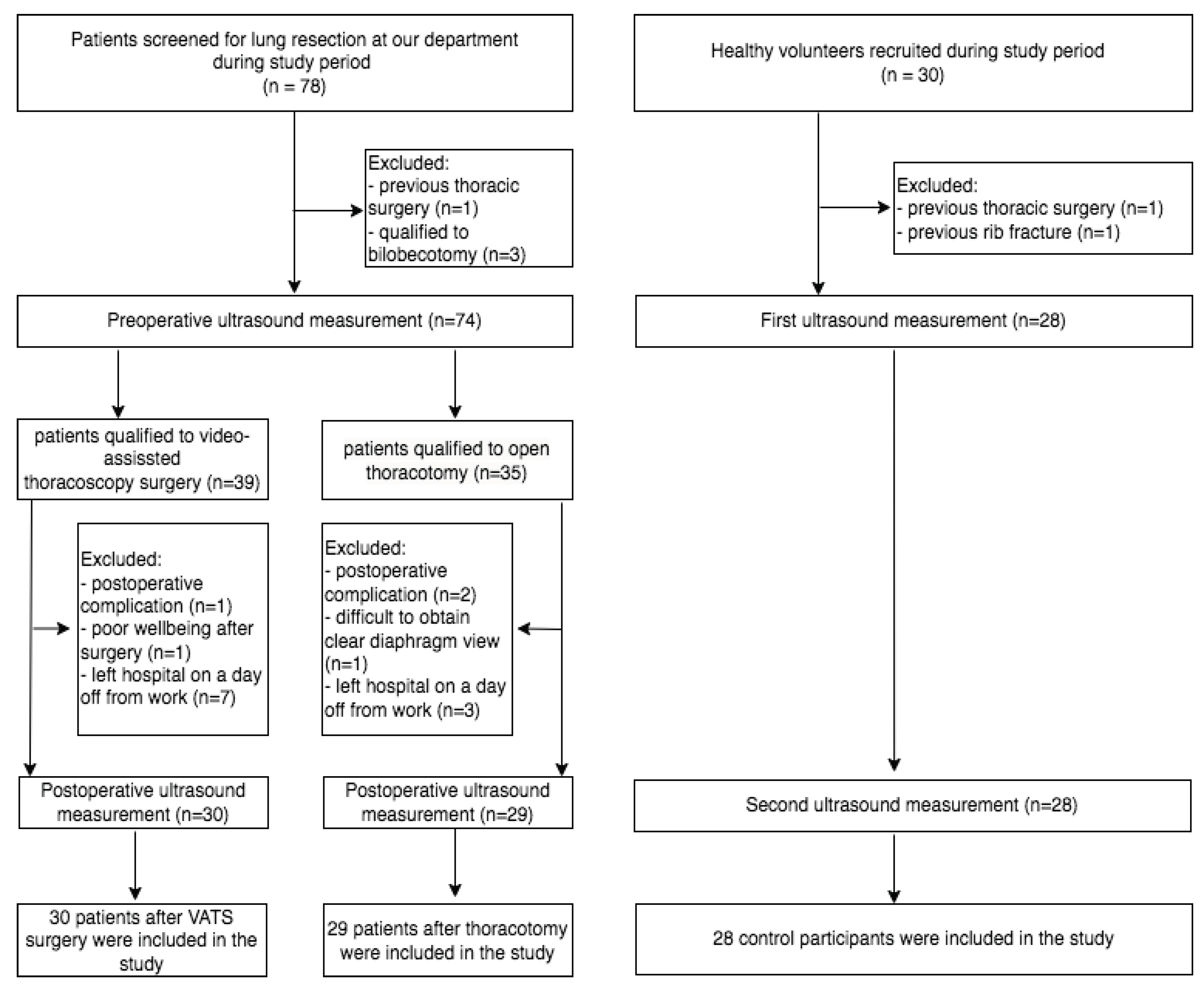

Our study included two groups of individuals. The first group (clinical) contained 59 adult diagnosed with resectable lung cancer pathologically confirmed, who were treated surgically. Of these, 50.84% (n=30) were undergone lung resection via video-assissted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) and the remaining 49.16% (n=29) were undergone open thoracotomy (OT). Patients who had the following features were excluded from the study: previous thoracic or/and abdominal surgery, concomitant diseases that can impair diaphragm function, poor ultrasound view of diaphragm muscle, patients inability to understand verbal instructions about breathing maneuvers. Cases with segmentectomy and bilobectomy were also denied. Demographics and preoperative informations such as age, height, weight, gender, involved side, and resected lobe were collected from the medical records of the patients.

The control group consisted of 28 adult volunteers. A subject data sheet was used to collect demographic data, such as age, sex, weight, height and medical status. The exclusion criteria for this group were as follows: history of thoracic or/and abdominal surgery, presence of chronic disease than can disturb diaphragm muscle work.

2.2. Surgical techniques

Surgical treatment of NSCLC involved anatomical resection of the lung lobe where the tumor was located (lobectomy) and removal of mediastinal lymph nodes (lymphadenectomy). All patients were operated by well-trained surgeons with long experience who worked at the Department of Thoracic Surgery. The surgical approach was non-randomly chosen between lateral thoracotomy approach or a minimally invasive method using videothoracoscopy by surgeon team performing lobectomy, based on clinical picture and attributes such as tumor size, patient age, pulmonary function and patient general condition.

Both procedures were carried out according to a standardized scheme. The classic method used access through an anterolateral thoracotomy, and after the procedure, two drains were placed in the pleural cavity through separate 2-3 cm incisions. The minimally invasive method was performed using the uniportal technique, i.e. through one incision about 4 cm long, into which one drain was inserted to pleural cavity. Each procedure was performed under general anesthesia (Propofol, Fentanyl, Sewofluran). Patients were intubated with a double-lumen tube and selectively ventilated to the lung on the side opposite to the operated one. Post surgery pain management was primarily achieved by oxycodone from an infusion pump supplemented with per os nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and paracetamol.

2.3. Diaphragm Muscle Ultrasound Assessment

Sonographic diaphragm muscle imaging was carried out using an Aloka Prosound Alpha 10 ultrasound machine. Patients were examined in the supine position that prevents any paradoxical movement, limits compensatory active expiration by the anterior abdominal wall which may mask paralysis, provides less variability, and reduce side to side variations. The high frequency (> 10MHz) linear array transducer was placed at the anterior axillary line in the area named zone of apposition and positioned to obtain a sagittal image at the intercostal space between the 8th and 10th ribs. In two-dimensional B-Mode set, the right and left hemidiaphragm was visualized through the liver and spleen window respectively, as a three layer structure with two outer echogenic layers of pleura and peritoneum lining an inner hipoechoic layer of muscle. During inspiratory and expiratory phases, this area normally thickens and shortens, respectively [

18,

19].

Before measurements, all participants were practically instructed about breathing maneuvers to perform. First, the subjects were examined during spontaneous respiration phase to identify the moving of a diaphragm. As a next stage, the patient was asked to perform a maximum inspiration and maximum forced expiration. The distance between the echogenic lines that determines inspiratory (ThIns) and expiratory (ThExp) thickness was measured in frozen images. For each breathing maneuver three readings were taken and the average values were finally included to statistical analysis. All participants were scanned two times by the same specialist with extensive experience. In the clinical group, measurements were done the day before the surgery and 3-5 days after the drains were removed. In the case of the control group, the second measurement took place 3-6 days after the first measurement.

Following diaphragm muscle function indices were calculated from obtained inspiratory and expiratory thickness [

18,

19]:

DTF (Diaphragm Thickness Fraction), reflecting magnitude of diaphragm effort. We used standardized formula: DTF = (ThIns - ThExp) / ThExp x 100%. The normal percentage for supine position is more or equal 65%. DTF values less than 20% are consistent with diaphragm muscle paralysis.

DTR (Diaphragm Thickening Ratio), reflecting the diaphragm muscle strength. This index was calculated using formula: DTR = ThIns / ThExp. Higher values represents a better outcome. The normal value are between 1.7 to 2.0.

Δ (Delta) - differences between preoperative (pre) and postoperative (post) values on each side were calculated using the formulas: Δ ThIns = ThIns (pre) - ThIns (post), Δ ThExp = ThExp (pre) - ThExp (post), ΔDTF = DTF (pre) - DTF (post), ΔDTR = DTR (pre) - DTR (post). For the precise comparative analysis, the differences between preoperative and postoperative values were also expressed as a percent of the preoperative amplitude: ΔThIns(%) = ΔThIns x 100 / ThIns(pre), ΔThExp(%) = ΔThExp x 100 / ThExp(pre), ΔDTF(%) = ΔDTF x 100 / DTF(pre), ΔDTR(%) = ΔDTR x 100 / DTR(pre).

StSv (Side to Side variability) - differences between left and right hemidiaphragm were calculated using the formulas: ThIns(StSv) = ThIns (left) - ThIns (right), ThExp(StSv) = ThExp(left) - ThExp(right), DTF(StSv) = DTF(left) - DTF(right), DTR(StSv) = DTR(left) - DTR(right). Obtained results are given as absolute values.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using PQ STAT software. The data distribution was tested using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Quantitative data were expressed as mean (M), standard deviation (SD) and 95% Confidence of Interval (CI), while quantitative and categorical variables were presented as a numbers and percentages. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and T-student test were accomplished to detect differences between groups. Chi-square test was used to check differences between proportions. To compare preoperative and postoperative data Wilcoxon signed rank test was chosen. For all analyses, a p value less than 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

3. Results

Flow chart for study participants is presented at

Figure 1.

There was no conversion to thoracotomy among patients who initially underwent VATS lobectomy. All three groups were comparable in respect to a number of participants, mean age and gender composition. Both clinical groups were also homogeneous in terms of involved side and lobe resection. Detailed baseline characteristics are given in

Table 1

There was no differences between three examined groups in relation to baseline parameters of the diaphragm function on the left (ThIns: [left] = 0.271, [right] = 0.291; ThExp: [left] = 0.356, [right] =0.364, DTF: [left] = 0.980, [right] = 0.923; DTR: [left] = 0.996, [right] = 0.915) and right (ThIns: [left] = 0.176, [right] = 0.415; ThExp: [left] = 0.795, [right] =, 0.741 DTF: [left] = 0.131, [right] = 0.320 DTR: [left] = 0.158, [right] = 0.313) sides of the body. We demonstrated a significant both sided postoperative decrease of inspiratory thickness, diaphragm thickness fraction and diaphragm thickening ratio compared to preoperative values, regardless to surgical approach and side of operation. However, the greater percentage deterioration of above mentioned parameters were noted among patients who underwent open thoracotomy than VATS (

Table 2 and

Table 3). In both clinical groups, most of patients had worse postoperative values of each analyzed diaphragm parameters, but in this point statistical significance between VATS and OT groups were not found.

In the control group, the differences between first and second measurements in case of inspiratory thickness (left side: 3.19±0.45 vs 3.20±0.49, p<0.822; right side: 3.16±0.43 vs 3.18±0.45, p<0.697), expiratory thickness (left side: 2.26±0.59 vs 2.28±0.61, p<0.746; right side: 2.23±0.62 vs 2.22±0.61, p<0.773), thickness fraction (left side: 39.62±17.86. vs 40.15±19.57, p<0.809; right side: 38.22±16.08 vs 38.74±17.44, p<0.811) and thickening ratio (left side: 1.62±0.23 vs 1.64±0.21, p<0.776; right side: 1.60±0.22 vs 1.61±0.20, p<0.001) were not observed. However, the presented values of diaphragm parameters obtained in second measurements were significantly higher in non-operated group - compared to post-surgery values measured in VATS (all p<0.001) and OT (all p<0.001) groups, respectively. In this group, only one of participants had worse outcomes, while 39.2%, 25%, 35.7%, and 42.8% had slightly better values of inspiratory and expiratory thickness, as well as, DTF and DTR indexes, respectively.

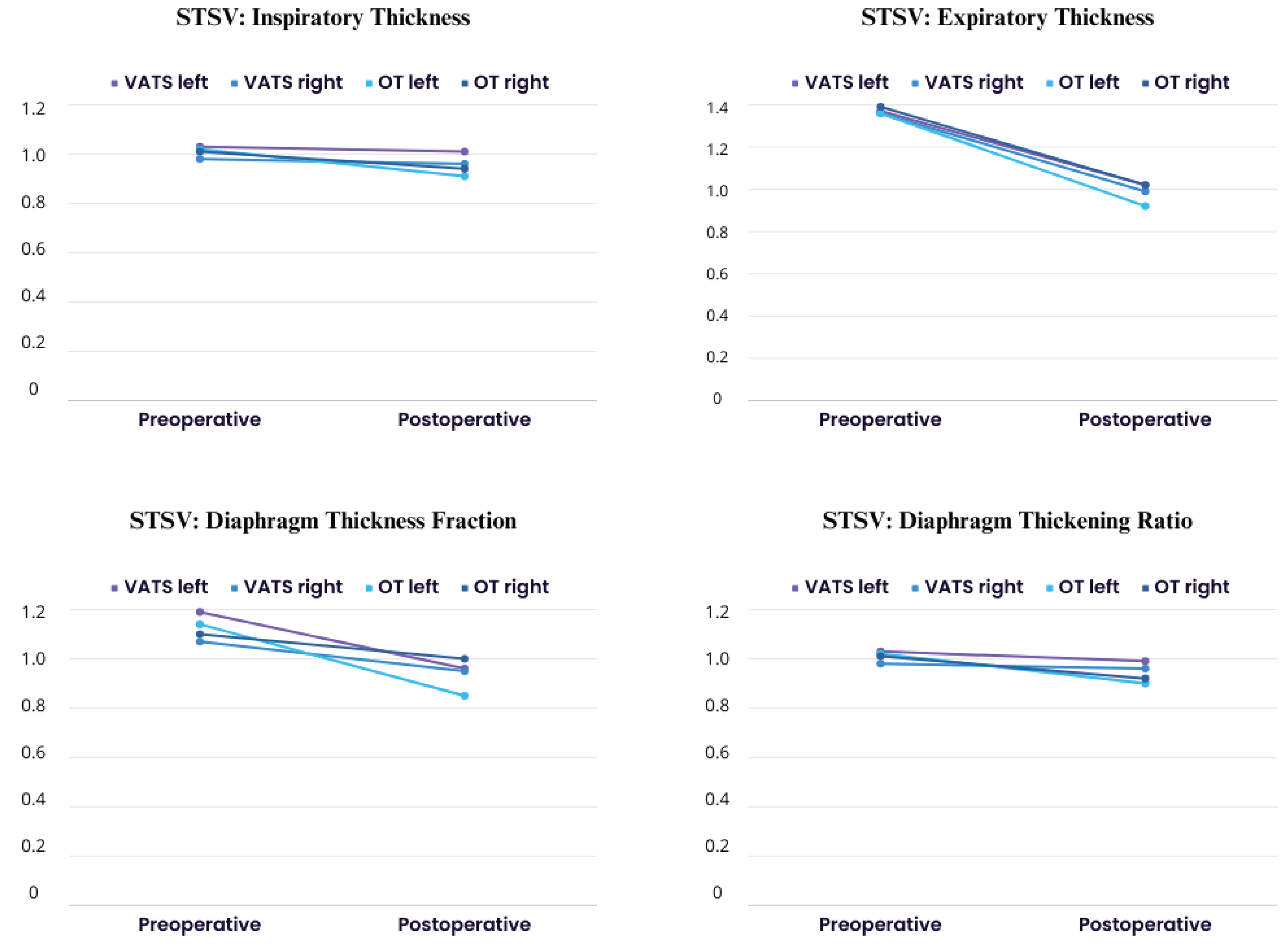

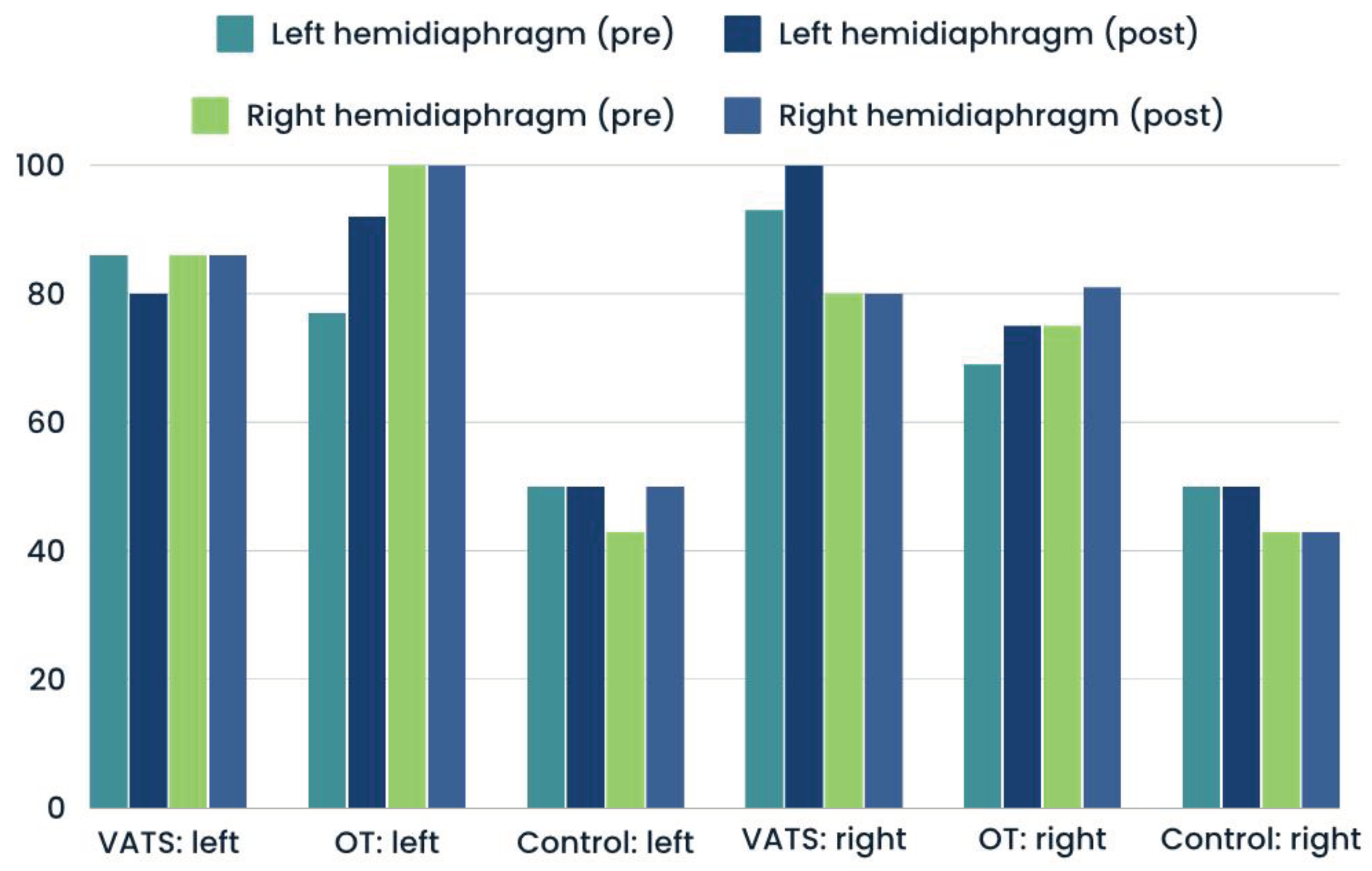

In

Figure 2, we presented values of stsv (side-to-side variability) index which measure differences between left and right hemidiaphragm. We demonstrated postoperative decrease compared to preoperative calculation in both groups in all parameters, what indicate on both diaphragm cupolaes dysfunction after lobectomy.

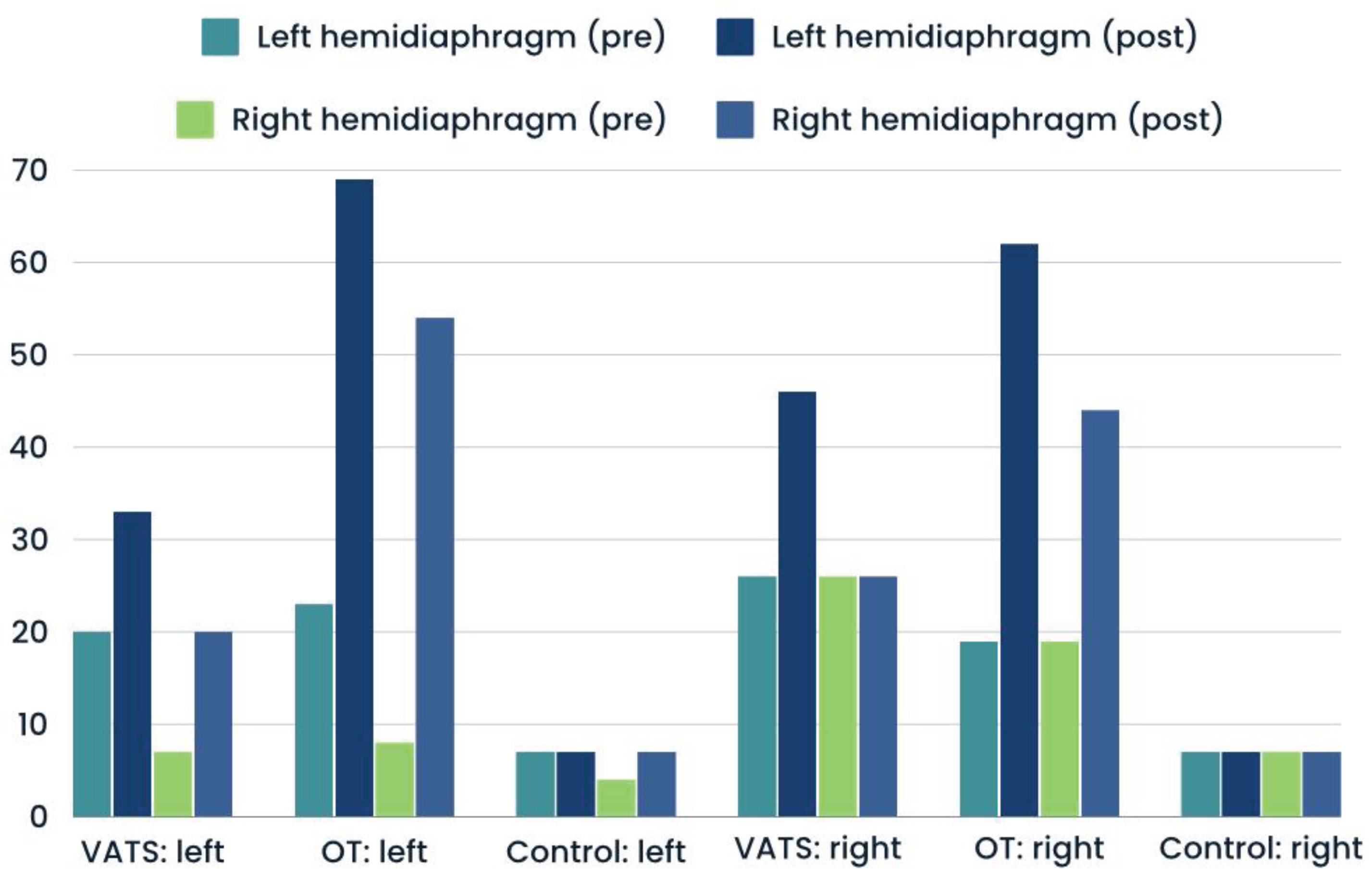

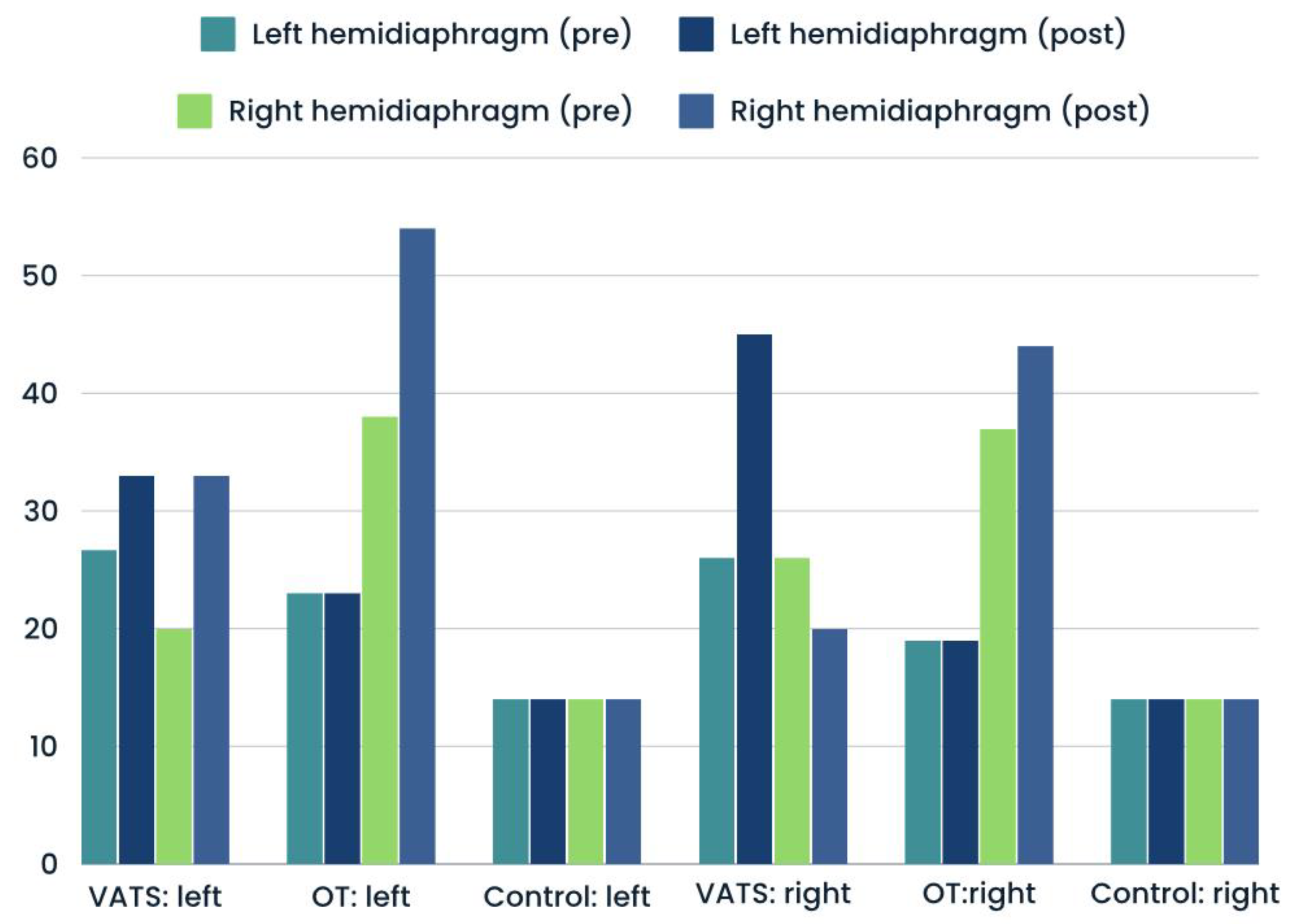

Significantly greater percentages of hemidiaphragm paralysis was found among patients who underwent open thoracotomy than VATS. This type of dysfuntion was present in similar number at operated and non-operated side (

Figure 3). The proportions of atrophy and weakness was only slightly higher after surgery in both groups - compared with input data (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5). In case of control group, we reported all three types of diaphragm dysfunctions on a similar level at first and second measurement (

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5).

Values of delta (Δ) index for diaphragm parameters divided into area of lung resection are given in

Table 4. Due to small sample size of patients with middle lobe resection were missed in analysis. Our findings showed each lobe resection was associated with impairment of analyzed parameters. The greatest postoperative diaphragm deterioration was identified in patients after upper left and right lobe resection - compered to lower lobes, but statistical significance was observed only in a few parameters. In all cases slightly higher values were observed on operated than non-operated side, but level of difference were not significant (

Table 4).

4. Discussion

Analysis of the data presented in

Table 2 and

Table 3, indicates that both surgical procedures were significantly associated with decrease of postoperative inspiratory diaphragm thickness, what was not observed in case of control group. Similarly, the values of diaphragm thickening ratio (DTR) reflecting diaphragm muscle strength were reduced - compared to baseline data. Taking into consideration the Delta Index, video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery had a less detrimental impact on above mentioned parameters than open thoracotomy. Our findings are consistent with previous studies. Bernard [

20] and Nomori [

21] also showed that conventional thoracotomy was associated with higher decrease of diaphragm muscle strength measured as Maximal Inspiratory Pressure (MIP) 2 days and 1 week after surgery, respectively. In contrast, Brocki [

22] et al., found that respiratory muscle strength was not affected postoperatively, but in this study second measurements were performed only 2 weeks after surgery.

Diaphragm Thickness Fraction (DTF) reflecting magnitude of diaphragm effort was more reduced after open procedures. Furthermore, the percentage of postoperative diaphragm paralysis, detected as DTF <20%, was also higher in this group. Mean values of postoperative expiratory diaphragm thickness were close to initial data. This finding allows to conclude that the redution of DTF index is primarily associated with decrease of inspiratory thickness than decrease of both parameters. No differences between groups were found in relation to percentage of diaphragm atrophies diagnosed as expiratory thickness less than 2 millimeters. To date, there are no previous studies comparing DTF index and expiratory thickness between OT and VATS, but one paper evaluated impact of surgery approach to diaphragm contractility by measuring its excursion. Spadaro et al., [

16] demonstrated that patients after VATS were characterized by better diaphragm excursion in first 24 hours after surgery. However, the measurements were performed only during spontaneous breathing, while DTF index refers to maximal inspiration.

All of the abnormalities we described here occurred on both operated and non-operated side. Also, the values of stsv (side to side variability) ratio showed dysfunction affected both side (

Figure 2). Our results are in opposition to other papers, in which authors described that diaphragm movement was strongly impaired on the operated side. In first paper, Spadaro et al., [

16] assessed diaphragm motion 2 and 24 hours after surgery, while in our study measurements were performed 3-5 days after surgery. At the base of this findings we can speculate that initially postoperative diaphragm dysfunction can be one-sided, but over time turns into both-side impairment. However, further studies precisely monitored postoperative diaphragm function day by day, are needed to confirm our hypothesis. In case of the second paper, the dissimilarities of the findings can be a result of different study populations. In Takazura [

14] study almost 70% patients were undergone upper lobes resection and bilobectomy, while our clinical group consisted of similar patient number for each resected lobes, as well as, we excluded patients after bilobectomy and segmentectomy. However, according to data presented in

Table 4, left and right upper lobe resection was associated with slightly greater impairment of hemidiaphragm strength and contractility on the operated side. Sekine et al., [

15] demonstrated that lobectomy of the lower portion resulted in better residual lung function than lobectomy of the upper portion in lung cancer patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

At this moment we don’t know whether described diaphragm dysfunctions are permanent or transient phenomenon, and if it is transient how long the diaphragm function returns to physiological values. A few previous studies reported faster recovery of respiratory muscle strength measured as Maximal Inspiratory Pressure [

20,

23,

24]. However, all of these studies have some limitations, because MIP is a general index not directly used to single assess diaphragm muscle, thereby not allow to evaluate hemidiaphragm and not differentiate dysfunction due to side of operation. Takazura [

14] showed that diaphragmatic motion on the operated side was significantly decreased, whilst on the nonoperated side was significantly increased as a compensatory mechanism. Maeda et al., [

25] showed an increase of intercostal muscle recruitment after pulmonary resection. Perhaps, with similar mechanisms can we encounter in the case of MIP improvement. For this reason, other studies should be designed to evaluate diaphragm function after thoracic surgeries in long-term perspective. However, we know that the reduce of DTF index emphasizes the necessity of use of pulmonary rehabilitation based on respiratory exercises after thoracic surgery procedures to restore the properly function of the diaphragm.

In summary, results of our study one more time emphasize lower invasiveness of the lobectomy via VATS versus conventional thoracotomy. The actual prevalence of post surgery diaphragmatic dysfunction may be underestimated as many patients may have no noticeable and specific symptoms, as well as, diaphragm ultrasound is not a gold standard in postoperative care [

26]. The causes of diaphragmatic dysfunction remain incompletely understood. Several mechanisms including changes in reflexogenic inhibition of phrenic nerve activation, pain, direct diaphragmatic muscle injury have been proposed [

27,

28]. However, according to latests study, the reduction in respiratory muscle function after operation is not affected by postoperative pain alone because pain relief by epidural anesthesia did not reduce diaphragm dysfunction [

29,

30]. Postoperative sedation and analgesia administered intravenously also did not influence on postoperative diaphragm dysfunction [

31]. In our study, the surgeons did not use electrocoagulation in the area of the phrenic nerve during lobectomy, which could cause damage or even temporary paralysis of the phrenic nerve. The periooperative diaphragm damage was also not reported.

5. Conclusions

On the basis of findings presented here, one may draw several clinically relevant conclusions with reference to the purposes defined at the beginning of the study.

1. Generally, greater diaphragm impairment was observed after lobectomy via conventional thoracotomy than VATS.

2. Inspiratory Thickness, Diaphragm Thickness Fraction (DTF) reflecting magnitude of diaphragm effort and Diaphragm Thickening Ratio (DTR) reflecting diaphragm muscle strength were significantly reduced after lobe resection in both groups, but the percentage of deterioration was greater after thoracotomy than VATS.

3. The percentage of hemidiaphragm paralysis was significantly higher after thoracotomy than VATS. Other types of diaphragm dysfunction (atrophy, weakness) were at similar level after surgery compared to preoperative data.

4. Degree of diaphragm impairment differed according to the location of the resected lobe. Left upper and right upper resection was associated with greater diaphragm impairment than in case of resection of other lobes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.K, M.R, D.C. and M.A; methodology, J.K and M.A.; formal analysis, J.K and M.R.; investigation, J.K and M.R.; resources, D.C and M.A.; data curation, J.K and M.R.; writing—original draft preparation, J.K and M.R.; writing—review and editing, M.A and D.C.; supervision, D.C, and M.A.; project administration, J.K and M.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of MEDICAL UNIVERSITY OF SILESIA, KATOWICE, POLAND (protocol code: KNW/0022/KB1/77/I/16; date of approval: 2016).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Global Burden of Disease Cancer Collaboration; Fitzmaurice, C.; Abate, D.; Abbasi, N.; et al. Global, Regional, and National Cancer Incidence, Mortality, Years of Life Lost, Years Lived With Disability, and Disability-Adjusted Life-Years for 29 Cancer Groups, 1990 to 2017: a Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. JAMA Oncol 2019, 5, 1749–1768. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Lee, H.; Huang, B.W. Lung Cancer: Diagnosis, Treatment Principles, and Screening. Am Fam Physician 2022, 105(5), 487–494. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Batihan, G.; Ceylan, K.C.; Usluer, O.; Kaya, S. Video-Assisted Thoracoscopic Surgery vs Thoracotomy for Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Greater Than 5 cm: Is VATS a feasible approach for large tumors? J Cardiothorac Surg. 2020, 15, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirby, T.J.; Mack, M.J.; Landreneau, R.J.; Rice, T.W. Lobectomy--video-assisted thoracic surgery versus muscle-sparing thoracotomy. A randomized trial. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1995, 109(5), 997–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, R.M.; Park, B.J.; Dycoco, J.; Aronova, A.; Hirth, Y.; Rizk, N.P.; et al. Lobectomy by video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) versus thoracotomy for lung cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009, 138, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landreneau, R.J.; Mack, M.J.; Hazelrigg, S.R.; et al. Prevalence of chronic pain after pulmonary resection by thoracotomy or video-assisted thoracic surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1994, 107, 1079–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.; Altorki, N.K.; Sheng, S.; Lee, P.C.; Harpole, D.; Onaitis, M.W.; et al. Thoracoscopic lobectomy is associated with lower morbidity than open lobectomy: a propensity-matched analysis from the STS database. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010, 139, 366–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagahiro, I.; Andou, A.; Aoe, M.; Sano, Y.; Date, H.; Shimizu, N. Pulmonary function, postoperative pain, and serum cytokine level after lobectomy: a comparison of VATS and conventional procedure. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001, 72, 362–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demmy, T.L.; Nwogu, C. Is video-assisted thoracic surgery lobectomy better? Quality of life considerations. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008, 85, S719–S728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Meyenfeldt, E.M.; Marres, G.M.H.; van Thiel, E.; et al. Variation in length of hospital stay after lung cancer surgery in the Netherlands. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2018, 54(3), 560–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nath, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; Tuheen, S.; et al. A Comparative Analysis of Video-Assisted Thoracoscopic Surgery and Thoracotomy in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer in Terms of Their Oncological Efficacy in Resection: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2022, 14(5), e25443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fratacci, M.D.; Kimball, W.R.; Wain, J.C.; Kacmarek, R.M.; Polaner, D.M.; Zapol, W.M. Diaphragmatic shortening after thoracic surgery in humans. Effects of mechanical ventilation and thoracic epidural anesthesia. Anesthesiology 1993, 79, 654–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, H.; Nakahara, K.; Ohno, K.; Kido, T.; Ikeda, M.; Kawashima, Y. Diaphragm function after pulmonary resection: relationship to postoperative respiratory failure. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1988, 137, 678–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takazakura, R.; Takahashi, M.; Nitta, N.; Sawai, S.; Tezuka, N.; Fujino, S.; et al. Assessment of diaphragmatic motion after lung resection using magnetic resonance imaging. Radiat Med. 2007, 25, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekine, Y.; Iwata, T.; Chiyo, M.; Yasufuku, K.; Motohashi, S.; Yoshida, S.; et al. Minimal alteration of pulmonary function after lobectomy in lung cancer patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003, 76, 356–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spadaro, S.; Grasso, S.; Dres, M.; Fogagnolo, A.; Dalla Corte, F.; Tamburini, N.; et al. Point of Care Ultrasound to Identify Diaphragmatic Dysfunction after Thoracic Surgery. Anesthesiology. 2019, 131, 266–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nomori, H.; Horio, H.; Naruke, T.; Suemasu, K. What is the advantage of a thoracoscopic lobectomy over a limited thoracotomy procedure for lung cancer surgery? Ann Thorac Surg. 2001, 72(3), 879–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarwal, A.; Walker, F.O.; Cartwright, M.S. Neuromuscular ultrasound for evaluation of the diaphragm. Muscle Nerve. 2013, 47(3), 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boussuges, A.; Rives, S.; Finance, J.; Chaumet, G.; Vallée, N.; Risso, J.J.; Brégeon, F. Ultrasound Assessment of Diaphragm Thickness and Thickening: Reference Values and Limits of Normality When in a Seated Position. Front Med (Lausanne) 2021, 27(8), 742703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, A.; Brondel, L.; Arnal, E.; Favre, J.P. Evaluation of respiratory muscle strength by randomized controlled trial comparing thoracoscopy, transaxillary thoracotomy, and posterolateral thoracotomy for lung biopsy. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2006, 29, 596–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nomori, H.; Horio, H.; Fuyuno, G.; Kobayashi, R.; Yashima, H. Respiratory muscle strength after lung resection with special reference to age and procedures of thoracotomy. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1996, 10, 352–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brocki, B.C.; Westerdahl, E.; Langer, D.; et al. Decrease in pulmonary function and oxygenation after lung resection. ERJ Open Res 2018, 4, 00055–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreetti, C.; Menna, C.; Ibrahim, M.; et al. Postoperative pain control: videothoracoscopic versus conservative mini-thoracotomic approach. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2014, 46(5), 907–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakata, M.; Saeki, H.; Yokoyama, N.; et al. Pulmonary function after lobectomy: video-assisted thoracic surgery versus thoracotomy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2000, 70(3), 938–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maeda, H.; Nakahara, K.; Ohno, K.; Kido, T.; Ikeda, M.; Kawashima, Y. Diaphragm function after pulmonary resection: relationship to postoperative respiratory failure. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1988, 137, 678–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siafakas, N.M.; Mitrouska, I.; Bouros, D.; et al. Surgery and the respiratory muscles. Thorax 1999, 54, 458–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ventura, L.; Zhao, W.; Chen, T.; et al. Significant diaphragm elevation suggestive of phrenic nerve injury after thoracoscopic lobectomy for lung cancer: an underestimated problem. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2020, 9(5), 1822–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piehler, J.M.; Pairolero, P.C.; Gracey, D.R.; Bernatz, P.E. Unexplained diaphragmatic paralysis: a harbinger of malignant disease? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1982, 84(6), 861–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenling, A.; Joachimsson, P.O.; Tyden, H.; Hedenstierna, G. Thoracic epidural analgesia as an adjunct to general anesthesia for cardiac surgery. Effects on pulmonary mechanics. Acta Anaesth Scand 2000, 44, 1071–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonneau, G.; Vivien, A.; Sartene, R.; Kunstlinger, F.; Samii, K.; Noviant, Y.; Duroux, P. Diaphragm dysfunction induced by upper abdominal surgery. Role of postoperative pain. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1983, 128(5), 899–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, H.; Doig, G.S.; Lv, Y. et al.; et al. Modifiable risk factors for ventilator associated diaphragmatic dysfunction: a multicenter observational study. BMC Pulm Med 2023, 23, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).