1. Introduction

The food-based dietary guidelines issued in 2000 (partly revised in 2016) for the Japanese population [

1] recommend well-balanced meals comprising staples (cereal grains), main courses (proteins), and sides (vegetables). Furthermore, the “Japanese Food Guide Spinning Top” was formulated in 2005. Mortality risk from cardiovascular [

2,

3] and cerebrovascular [

3] diseases decreased in individuals who adhered to the sex- and age-recommended daily amounts of various food groups, as indicated in the 2005 Japanese Food Guide Spinning Top [

4]. The Japanese government has set a goal to ensure that the proportion of Japanese individuals who consume meals comprising staple foods, main courses, and side dishes at least twice daily increases to at least 50% of the population by 2025. However, in 2020, the actual figures remained extremely low at 36.4% [

5]. The Hyogo Nutrition and Diet Survey conducted in 2021 showed that, among respondents aged ≥20 years, compared to males and females aged 60–69 years (38.9% and 47.3%, respectively), the proportion of those who consumed meals that comprised staples, main courses, and side dishes at least twice a day on “6 or 7 days per week” was the lowest among males and females aged 20–29 years (26.5% and 25.8%, respectively), followed by males and females aged 30–39 years (27.4% and 32.7%, respectively); the proportion was the lowest among the younger generation [

6].

Besides the problem of not consuming well-balanced diets, younger adults have another problem: skipping breakfast. Daily breakfast consumption is recommended by health and nutrition professionals and governments worldwide [

7]. Breakfast consumption is associated with better dietary quality [

8,

9] and helps prevent stroke in Japan [

10]. However, a global decline in breakfast consumption has been noted in many countries [

11]. Similarly, Japan is not exempt from this behaviour; according to the 2017 National Health and Nutrition Survey [

12], the percentage of individuals who skipped breakfast was the highest in males and females aged 20–29 years (30.6% and 23.6%, respectively). The Hyogo Nutrition and Diet Survey conducted in 2021 [

6] showed that, among the respondents aged ≥20 years, the proportion of those who ate breakfast “6 or 7 days per week” was the lowest among males, compared to females, aged 20–29 years (47.0% vs. 64.9%). Therefore, skipping breakfast is a common dietary issue among younger adults, along with the infrequent consumption of diets that contain staples, main courses, and side dishes. Low health awareness might be a key factor mediating the above-mentioned problems in younger adults [

13], especially among males [

14].

The United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) [

15] necessitate a transition to sustainable food systems, which involves major improvements in food-production practices, a substantial shift toward mostly plant-based diets, and marked reductions in food loss and waste [

16], to reduce environmental impacts and achieve a better food future. The EAT-Lancet Commission confirmed the need for a shift toward the Planetary Health Diet [

17]; accordingly, the Sustainable Healthy Diets Guiding Principles [

18] were published by the WHO in 2019. Moreover, food-based dietary guidelines implemented with the assistance of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) incorporate the need for sustainability. Thus, a planetary health diet is recommended to achieve the SDGs worldwide. A recent survey in Japan [

19] showed an SDG awareness rate of 86.0%, which had increased by more than 30% and approximately six times from that in the fourth and first surveys conducted in January 2021 and February 2018, respectively. When stratified by sex and age, SDG awareness was higher among teenage males (94.6%) and those in their 30s (91.8%). Therefore, relatively young adults are expected to be slightly more interested in planetary environment-related issues rather than health-related issues. As breakfast consumption has been associated with better dietary quality (8,9), we hypothesised that combined adherence to the recommended planetary health diet and regular breakfast consumption might promote the adoption of a well-balanced diet among young Japanese males. This theory indicates the need to examine the associations of planetary health diet consumption with regular breakfast consumption and the intake of a well-balanced diet to promote a healthy diet among young adults.

In this study, we aimed to comprehensively determine the associations between regular breakfast consumption and adherence to planetary health and well-balanced diets among Japanese male university students. The planetary health diet encompasses foods recommended to achieve the SDGs, and this research assessed the impact of the planetary health diet and eating breakfast on well-balanced diets in this demographic. Recommending the planetary health diet [

17,

18] should aid in promoting a healthy diet and ameliorating prevalent issues [

6,

12], such as poorly balanced diets and irregular breakfast habits among young adults.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

The study was conducted at a public university in Hyogo Prefecture, Japan. The target group consisted of 1624 engineering students aged 18–24 years (1397 male and 227 female). We asked the university students to complete a questionnaire survey through the notice board of the university portal site and flyers with a QR code for Google Forms. The response period was from November 7 to December 10, 2022. Posters with QR codes were also displayed at conspicuous locations across the university. In total, 222 students completed the questionnaire. Among them, female students (n = 37) and those who had missing values were excluded, leaving 142 eligible male students (age: 20.0 ± 1.3 years, who were selected (80.6% valid response rate) for the analysis.

This study was conducted in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving study participants were approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Hyogo. After informed consent was provided to all participants prior to their participation in the original study, those who responded to the survey were considered to have consented to participate in the study.

2.2. Measures

The questionnaire for this study included items pertaining to the respondents’ characteristics, including age, breakfast regularity (eating breakfast regularly: ≥4 days/week or not eating breakfast regularly: ≤3 days/week or less), living arrangement (living alone or with family), regular exercise (exercise for ≥30 min) (3 times per week for ≥1 year/2 times per week for ≥1 year/2 times per week and <1 year continuously/Once per week/Little or no exercise/No exercise at all), importance of breakfast for healthy living (Very important /Somewhat important/Not very important/Not important at all), and self-assessment of diet (What do you think of your current dietary habits?) (Very good/Good/A few problems/Many problems), frequency of eating well-balanced diet at least twice daily per week (6 or 7 days/4 or 5 days/2 or 3 days/≤1 day/Not at all), frequency of eating meals with family or friends per week (6 or 7 days/4 or 5 days/2 or 3 days/≤1 day/Not at all), planetary health diet initiatives (Working already (>6 months)/Working already (<6 months)/Intend to start soon (within 1 month)/Intend to start soon (within 6 months)/Interested, but not working/Not interested), and self-reported height and body weight. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as body weight (kg)/height (m)2. Well-balanced diets were defined as the regular consumption of meals composed of staples, main courses, and side dishes at least twice daily.

Food constituting the planetary health diet was defined based on a previous study [

17], that is, consumption of two “abstain” items (beef and pork dishes) and eight “recommended” items (chicken dishes, fish dishes, egg dishes, soybeans/soybean products, nuts, dairy foods, vegetable-based dishes, and fruit). The students were asked to choose only one option for the frequency of each item and assigned scores as follows: 7 = at least twice daily, 6 = once daily, 5 = 5 or 6 times/week, 4 = 3 or 4 times/week, 3 = 1 or 2 times/week, 2 = 1–3 times/month, and 1 = Not at all for each item.

2.3. Data Analysis

The mean values for age by breakfast regularity (eating breakfast regularly: ≥4 days/week or not eating breakfast regularly: ≤3 days/week or less) were compared using a Student’s t-test, and proportions (BMI, living arrangement) by breakfast regularity were compared using the chi-square test. The variables of regular exercise, importance of breakfast for healthy living, self-assessment of diet, frequency of well-balanced diets, frequency of eating meals with family or friends, planetary health diet initiatives, and each consumption item of planetary health diets were analysed on an interval scale. Welch’s t-test was used to compare the above-specified items by breakfast regularity.

We developed an initial hypothetical model (

Figure 1) using factors potentially associated with the intake of a well-balanced diet at least twice daily, including regular breakfast consumption and the eight variables recommended for planetary health diet consumption. We performed a covariance structure analysis to validate the hypothetical model. Based on the path direction, standardised estimates, coefficient of determination, and fit indices, such as the goodness-of-fit index (GFI), adjusted GFI (AGFI), comparative fit index (CFI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and Akaike’s information criterion (AIC), we repeatedly modified the model (for example, by deleting non-significant paths) until the best possible fit was achieved. We determined that the goodness of fit of the model was better when the GFI, AGFI, and CFI indices were ≥0.9, RMSEA was ≤0.05, and AIC was lower than those of the other models. The sample size was calculated using RMSEA for the null hypothesis: ε0 ≤ 0.1, and RMSEA for the alternative hypothesis: ε1 = 0.01, with the power of the not close fit test = 0.8, model degrees of freedom = 19, a significance level of 5%. With 19 model degrees of freedom, the minimum sample size calculated was 117 [

20]. Statistical significance was set at

p < 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 26 (IBM Japan, Ltd., Tokyo, 2019).

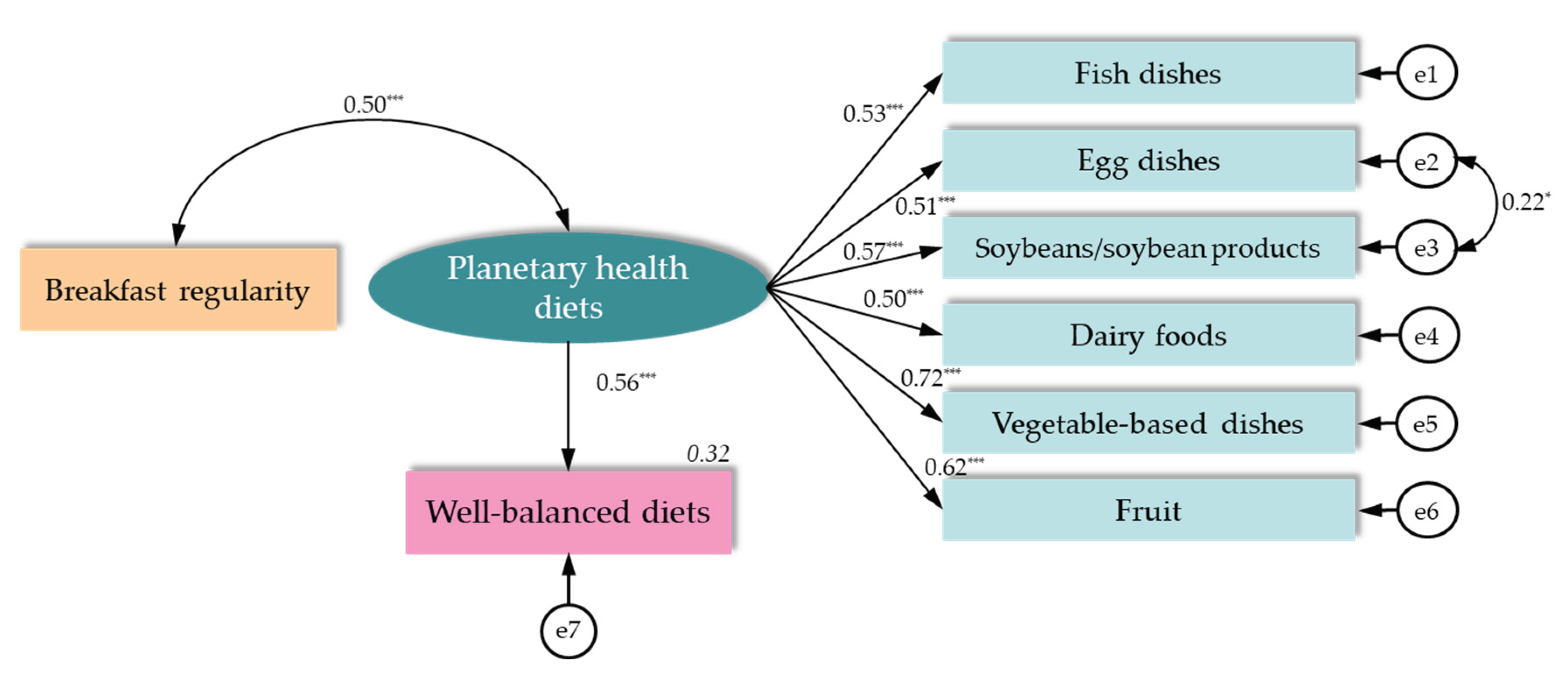

The bidirectional arc arrow shows an association, and the straight arrows indicate significant paths.

3. Results

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the participants and the results of comparisons by breakfast regularity. Among participants who consumed breakfast regularly, those living with family accounted for the highest percentage (78.2%). In contrast, among participants who did not eat breakfast regularly, 56.1% lived alone, with a significant intergroup difference (

p < 0.001). A significantly higher percentage of those with and without regular breakfast consumption (74.3% and 39.0%, respectively) indicated that breakfast was crucial for healthy living (

p < 0.001). In terms of self-assessment of diet for the question “What do you think of your current dietary habits?” Of the participants with and without regular breakfast consumption, 47.5% and 53.7% reported good and few problems, respectively, with a significant intergroup difference (

p < 0.001). Comparisons of breakfast regularity showed no intergroup difference in the frequency of working on a planetary health diet; however, there was a significant intergroup difference (

p < 0.001) in the frequency of eating a balanced diet comprising staples, main courses, and side dishes at least twice per day for 6 or 7 days/week, which was the highest and lowest among participants with and without regular breakfast consumption (35.6% and 2.4%, respectively).

Table 2 shows the results of the comparisons of planetary health diets (abstain/recommended) based on breakfast regularity. In the analysis based on breakfast regularity, for the abstinence items of the planetary health diet, there was a significantly higher frequency of intake of pork dishes (

p = 0.027) among participants with regular breakfast consumption compared to those without it; however, there was no significant intergroup difference in the frequency of intake of beef dishes. In the analysis based on breakfast regularity, for the eight recommended items of the planetary health diet, there were significant intergroup differences for all items except chicken (fish,

p = 0.005; eggs,

p = 0.006; soybeans/soybean products,

p = 0.002; nuts,

p = 0.008; dairy foods,

p = 0.001; vegetables,

p < 0.001; and fruits,

p < 0.001).

In the initial hypothetical model (

Figure 1), the results of the covariance structure analysis did not show acceptable goodness of fit (χ

2 = 69.419,

df = 34, GFI = 0.915, AGFI = 0.863, CFI = 0.873, RMSEA = 0.086, and AIC = 111.419). Therefore, by excluding chicken dishes and nuts from the eight recommended items of the planetary health diet, an acceptable goodness of fit was obtained (χ

2 = 24.586,

df = 19, GFI = 0.962, AGFI = 0.927, CFI = 0.975, RMSEA = 0.046, AIC = 58.586). Frequent consumption of the remaining six items of a planetary health diet, namely fish, eggs, soybeans/soybean products, dairy foods, vegetables, and fruits, had a significant positive correlation (0.50,

p < 0.001) with breakfast regularity and a significant positive path (standardised estimate 0.56,

p < 0.001) to transition to well-balanced diets (

Figure 2).

The numbers in regular font in the path diagram are standardised estimates (next to the straight arrows) and correlation coefficients (above the bidirectional arc arrow). The numbers in italics are R2 values (coefficients of determination). Statistical significance was set at * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, and *** p < 0.001. The covariance structure analysis results suggested that the hypothetical model had acceptable goodness of fit (χ2 = 24.586, df = 19 (p = 0.175), GFI = 0.962, AGFI = 0.927, CFI = 0.975, RMSEA = 0.046, AIC = 58.586).

4. Discussion

In this study, we investigated whether recommending regular breakfast habits and a planetary health diet [

17,

18], including chicken, fish, eggs, soybeans/soybean products, nuts, dairy foods, vegetables, and fruits, might help ameliorate dietary issues [

6,

12] such as poorly balanced diets among young Japanese adults. Accordingly, a structural analysis of the covariance of the hypothesised model was performed using planetary health diet consumption, regular breakfast consumption, and well-balanced diet intake in young males.

After excluding chicken and nuts, the final hypothetical model of this study comprised six of the eight recommended items of the planetary health diet, namely, fish, eggs, soybeans/soybean products, dairy foods, vegetables, and fruits. The results of this study showed that, despite the higher frequency of intake of chicken dishes than that of beef or pork dishes, there was no significant intergroup difference in the frequency of intake of chicken dishes in the subgroup analysis stratified by breakfast regularity; therefore, intake of chicken dishes was excluded from the final model. The analysis also excluded the intake of nuts, potentially due to their infrequent consumption. Nuts are not commonly consumed in Japanese dietary habits.

Among the G20 countries, Japan has relatively low per-capita food-related greenhouse gas emissions [

21,

22]. Furthermore, adherence to a well-balanced diet, characterised by a combination of staple foods, main courses, and side dishes, as outlined in the 2000 Japanese food-based dietary guidelines, is currently recommended. The origin of Japanese cuisine is attributed to “

honzen ryori” (

honzen cuisine), which was used to entertain guests of the samurai families in the Muromachi period (AD 1336–1573), and its basic form is “

ichijyu sansai” (one soup and three dishes: vinegared, simmered, and grilled) in addition to rice and savoury dishes [

23,

24,

25]. Throughout its extensive history, Japanese food culture has permeated the existing dietary habits of the Japanese people, which includes eating “

okazu” (the main course and side dishes) with rice – the staple food – as the main ingredient. Dairy products were not a part of the common people’s diet until after World War II. The Ministry of Health and Welfare (now the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare) established a Ministerial Ordinance on Ingredient Standards for Dairy Products in 1951. This is possibly why the current daily intake of Japanese people remains at a low average of 110.7 g [

26]. However, in this study, dairy foods were included among the six recommended items of the planetary health diet. The percentage of adults (age ≥20 years) who ate rice for breakfast daily (17.7% in the 2016 Hyogo Dietary Survey) [

27] was lower than that 13 years ago (24.8% in 2003). In contrast, the highest percentage of breakfast content in the 2016 Hyogo Dietary Survey [

27] comprised staple foods (91.9%), whereas dairy foods accounted for 47.6%, which was higher than the 37.5% and 36.7% contents of main and side dishes, respectively. This may be due to the intake of dairy foods, along with bread and non-rice cereals, as a staple for breakfast. Therefore, because they are regularly consumed at breakfast, dairy foods may have been retained as one of the six items in the planetary health diet.

For more than 20 years, the National Health and Nutrition Survey in Japan has indicated that the lower consumption of fish (50.8 g vs. 59.2 g), soybeans/soybean products (46.2 g vs. 63.4 g), vegetables (222.6 g vs. 268.6 g), and fruits (46.9 g vs. 70.6 g) per day among young adults than among middle-aged and older adults (age groups 20s vs. 50s, respectively) constitutes a problem [

26]. In this study, dietary issues in young adults accounted for four of the six recommended items in the planetary health diet. Therefore, improving the intake of these items in combination with regular breakfast consumption may lead to a healthy and well-balanced diet.

The importance of breakfast has been reported in various countries, including higher dietary quality among American adults [

9], Australian adults [

28], and European adolescents [

29] who consumed breakfast, and the contribution of breakfast to the overall dietary quality among Malaysian [

30] and Indonesian [

31] adults. The intake of foods associated with planetary health diets may vary slightly in each country. Nonetheless, the combination of the recommended planetary health diet and regular breakfast consumption may be an effective strategy to improve diet quality not only in Japan but also in other countries worldwide.

The strengths of the present study include the examination of dietary issues such as adherence to a balanced diet and skipping breakfast among young Japanese individuals, which may be ameliorated through an interventional approach that incorporates a focus on the planetary health diet to achieve the SDGs. Importantly, our study also serves to integrate the findings that foods that were identified as problematic through low consumption among young adults were nearly identical to the foods recommended in the planetary health diet.

The limitations of this study include the fact that the participants were male students enrolled in an engineering program at a university in Hyogo Prefecture. Therefore, they are not representative of the overall Japanese population aged 18–24 years. Further research involving female participants of different ages should be conducted to confirm these results. Moreover, because this was a cross-sectional study, we were unable to ascertain a causal relationship between regular breakfast consumption-related changes in adherence to the recommendations of the planetary health diet to protect the planet’s environment and habituation to a well-balanced diet. An additional study of the effects of a well-balanced diet through interventional research that promotes regular breakfast consumption according to the recommendations of the planetary health diet for young adults will be helpful in this regard.

In summary, we examined the structural associations between planetary health diet consumption and regular breakfast and well-balanced diet intake in young males. In male university students, the association of regular breakfast consumption with adherence to the planetary health diet, which includes foods recommended to achieve the SDGs, may lead to the consumption of a well-balanced diet.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we suggested that recommending regular breakfast habits and a planetary health diet, which helps meet the SDGs set by the United Nations, might help ameliorate dietary issues such as poorly balanced diets among young Japanese adults.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.K. and M.N.; methodology, E.K. and M.N.; validation, E.K.; formal analysis, E.K.; investigation, E.K. and M.N.; resources, E.K. and M.N.; data curation, M.N.; writing—original draft preparation, E.K.; writing—review and editing, M.N.; visualisation, E.K.; supervision, E.K. and M.N.; project administration, E.K. and M.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partly funded by the Hyogo Prefectural Government (no grant number is available). The Hyogo Prefectural Government had no involvement in the study design, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and writing of the report. Neither had any restrictions regarding the submission or publication of the report.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving the study participants were approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Hyogo (Code: 297, Date: 14 November 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Data Availability Statement

The data in this study are available on request from the corresponding authors. The data are not publicly available due to confidentiality reasons.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the staff of the Academic Affairs Division for their assistance in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Food-based dietary guidelines. Japan. Available online: https://www.fao.org/nutrition/education/food-dietary-guidelines/regions/countries/japan/en/ (accessed on 23 August 2023).

- Oba, S.; Nagata, C.; Nakamura, K.; Fujii, K.; Kawachi, T.; Takatsuka, N.; Shimizu, H. Diet based on the Japanese Food Guide Spinning Top and subsequent mortality among men and women in a general Japanese population. J Am Diet Assoc 2009, 109, 1540–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurotani, K.; Akter, S.; Kashino, I.; Goto, A.; Mizoue, T.; Noda, M.; Sasazuki, S.; Sawada, N.; Tsugane, S.; Japan Public Health Center based Prospective Study Group. Quality of diet and mortality among Japanese men and women: Japan Public Health Center based prospective study. BMJ 2016, 352, i1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshiike, N.; Hayashi, F.; Takemi, Y.; Mizoguchi, K.; Seino, F. A new food guide in Japan: the Japanese food guide Spinning Top. Nutr Rev 2007, 65, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Japan Minister of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. The fourth basic program for Shokuiku promotion (provisional translation); March 2021. Available online: https://www.maff.go.jp/j/syokuiku/attach/pdf/kannrennhou-30.pdf (accessed on 23 August 2023).

- Hyogo Prefecture. The Hyogo Nutrition and Diet Survey Report in 2021. Available online: https://web.pref.hyogo.lg.jp/kf17/hyogoeiyoushokuseikatujittaichousa.html (accessed on 29 September 2023). (In Japanese).

- Gibney, M.J.; Barr, S.I.; Bellisle, F. Drewnowski, A.; Fagt, S.; Livingstone, B.; Masset, G.; Varela Moreiras, G.; Moreno, L.A.; Smith, J.; Vieux, F. Breakfast in human nutrition: the International Breakfast Research Initiative. Nutrients 2018, 10, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellisle, F.; Hébel, P.; Salmon-Legagneur, A.; Vieux, F. Breakfast consumption in French children, adolescents, and adults: a nationally representative cross-sectional survey examined in the context of the International Breakfast Research Initiative. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drewnowski, A.; Rehm, C.D.; Vieux, F. Breakfast in the United States: food and nutrient intakes in relation to diet quality in National Health and Examination Survey 2011⁻2014. A Study from the International Breakfast Research Initiative. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubota, Y.; Iso, H.; Sawada, N.; Tsugane, S. JPHC Study Group. Association of breakfast intake with incident stroke and coronary heart disease: the Japan Public Health Center-Based Study. Stroke 2016, 47, 477–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazzeri, G.; Ahluwalia, N.; Niclasen, B.; Pammolli, A.; Vereecken, C.; Rasmussen, M.; Pedersen, T.P.; Kelly, C. Trends from 2002 to 2010 in daily breakfast consumption and its socio-demographic correlates in adolescents across 31 countries participating in the HBSC Study. PLOS ONE 2016, 11, e0151052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Japan Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. The National Health and Nutrition Survey in Japan. 2017. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/kenkou_iryou/kenkou/eiyou/h29-houkoku.html (accessed on 29 September 2023). (In Japanese).

- Okobi, O.E.; Adeyemi, A.H.; Nwimo, P.N.; Nwachukwu, O.B.; Eziyi, U.K.; Okolie, C.O.; Orisakwe, G.; Olasoju, F.A.; Omoike, O.J.; Ihekire, L.N.; Afrifa-Yamoah, J. Age group differences in the awareness of lifestyle factors impacting cardiovascular risk: A population-level study. Cureus 2023, 15, e41917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kibayashi, E.; Nakade, M.; Morooka, A. Dietary habits and health awareness in regular eaters of well-balanced breakfasts (Consisting of shushoku, shusai, and fukusai). (Abstract in English) Jpn J Nutr Diet 2020, 78, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Sustainable development goals. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 29 September 2023).

- Rockström, J.; Gaffney, O.; Rogelj, J.; Meinshausen, M.; Nakicenovic, N.; Schellnhuber, H.J. A roadmap for rapid decarbonization. Science 2017, 355, 1269–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willett, W.; Rockström, J.; Loken, B.; Springmann, M.; Lang, T.; Vermeulen, S.; Garnett, T.; Tilman, D.; DeClerck, F.; Wood, A.; Jonell, M. Food in the Anthropocene: the EAT-Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet 2019, 393, 447–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Sustainable healthy diets: guiding principles. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241516648 (accessed on 4 January 2023).

- Dentsu Macromill Insight, Inc. Dentsu conducts fifth consumer survey on sustainable development goals (Marketing Reports in 2022). Available online: https://www.dentsu.co.jp/en/news/release/2022/0427-010519.html#:~:text=Survey%20Findings-,1.,carried%20out%20in%20February%202018 (accessed on 1 October 2023).

- MacCallum, R.C.; Browne, M.W.; Sugawara, H.M. Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychol Methods 1996, 1, 130–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EAT. Diets for a better future: rebooting and reimagining healthy and sustainable food systems in the G20 (Uploaded in 2020). Available online: https://eatforum.org/content/uploads/2020/07/Diets-for-a-Better-Future_G20_National-Dietary-Guidelines.pdf (accessed on 8 October 2023).

- Springmann, M.; Spajic, L.; Clark, M.A.; Poore, J.; Herforth, A.; Webb, P.; Rayner, M.; Scarborough, P. The healthiness and sustainability of national and global food based dietary guidelines: modelling study. BMJ 2020, 370, m2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanjyonishi, S. Sanetaka koki, bottom of vol. 5 [実隆公記〈巻5下〉] (Editor: Takahashi, R.); Zokugunshoruiju-kanseikai, Ltd.: Tokyo, Japan, 1963 (bankrupt in 2006, now taken over by Yagi-Shoten, Ltd.: Tokyo, Japan); http://www.books-yagi.co.jp/. (In Japanese).

- Yamashina, T. Tokikuni kyoki, No. 4: Shiryo sanshu [言国卿記 第4(史料纂集)] (Editor: Toyoda, T., Itakura, H.); Zokugunshoruiju-kanseikai, Ltd.: Tokyo, Japan, 1977 (bankrupt in 2006, now taken over by Yagi-Shoten, Ltd.: Tokyo, Japan); http://www.books-yagi.co.jp/. (In Japanese).

- Maeda, H. Tairyo-ko nikki, No. 4: Shiryo sanshu [太梁公日記 第4(史料纂集)], Editor (in publishing, etc.): Sonkeikaku Bunko, Nagayama, N.; Yagi-Shoten, Ltd.: Tokyo, Japan, 2012; http://www.books-yagi.co.jp/. (In Japanese).

- Japan Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. The National Health and Nutrition Survey in Japan. 2019. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/kenkou_iryou/kenkou/eiyou/r1-houkoku_00002.html (accessed on 8 October 2023). (In Japanese).

- Hyogo Prefecture. The Hyogo Dietary Survey Report in 2016. Available online: https://web.pref.hyogo.lg.jp/kf17/kf17/28shokuseikatu-jittaichousa.html (accessed on 8 October 2023). (In Japanese).

- Wang, W.; Grech, A.; Gemming, L.; Rangan, A. Breakfast size is associated with daily energy intake and diet quality. Nutrition 2020, 75-76, 110764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giménez-Legarre, N.; Santaliestra-Pasías, A.M.; De Henauw, S.; Forsner, M.; González-Gross, M.; Jurado-Fasoli, L.; Kafatos, A.; Karaglani, E.; Lambrinou, C.P.; Molnár, D.; Sjöström, M. Breakfast consumption and its relationship with diet quality and adherence to Mediterranean diet in European adolescents: the HELENA study. Eur J Clin Nutr 2022, 76, 1690–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mognard, E.; Sanubari, T.P.E.; Alem, Y.; Yuen, J.L.; Ragavan, N.A.; Ismail, M.N.; Poulain, J.P. Breakfast practices in Malaysia, nutrient intake and diet quality: a study based on the Malaysian Food Barometer. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khusun, H.; Anggraini, R.; Februhartanty, J.; Mognard, E.; Fauzia, K.; Maulida, N.R.; Linda, O.; Poulain, J.P. Breakfast consumption and quality of macro- and micronutrient intake in Indonesia: a study from the Indonesian Food Barometer. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).