Submitted:

29 February 2024

Posted:

01 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

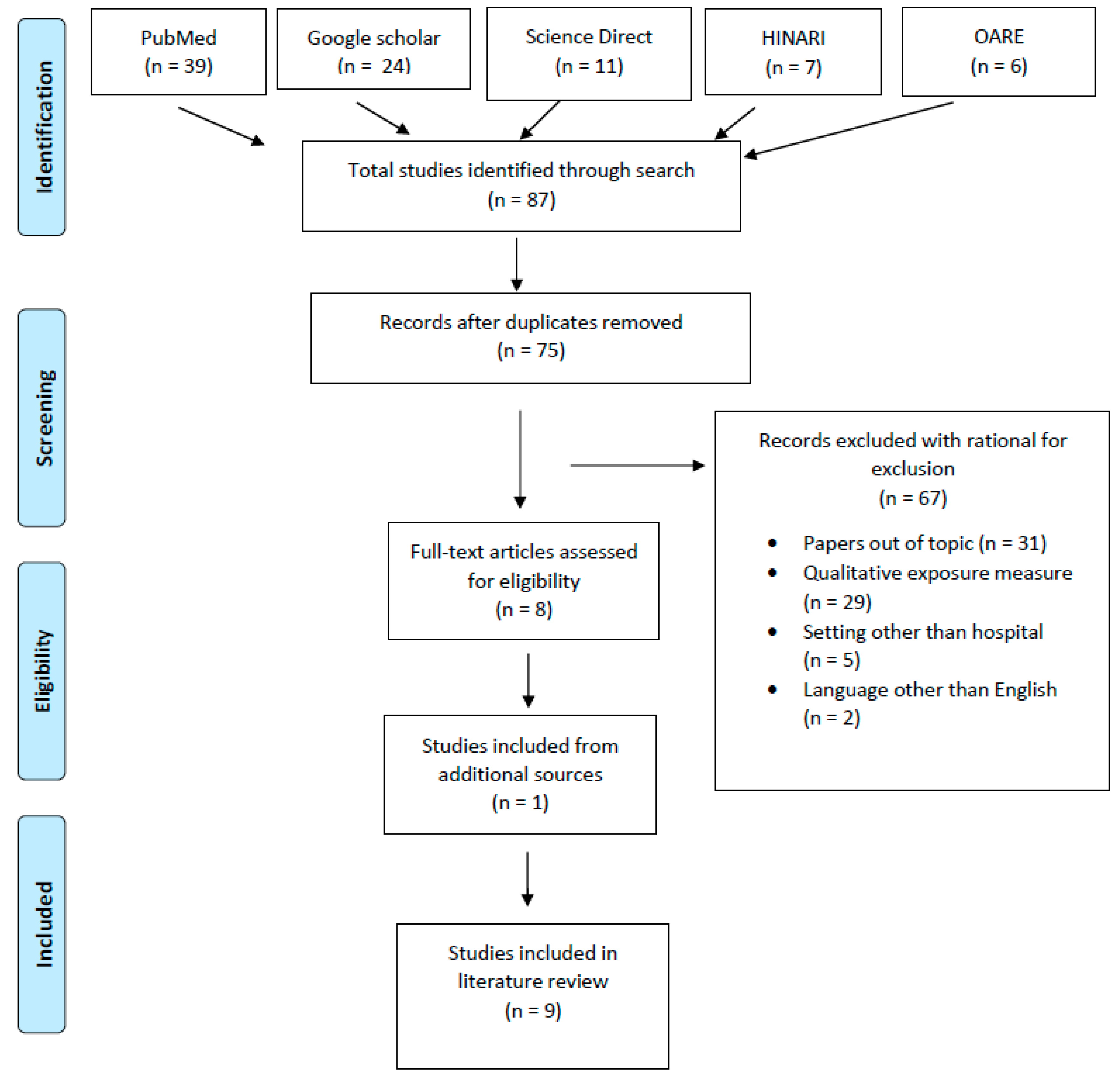

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

Biological Monitoring of Healthcare Workers

Surface Contamination of Work Surfaces

Significance to Public Health

5. Conclusion

References

- Ae, A. P., Schierl, R., Karlheinz, A. E., Carl-Heinz, H., Ae, G., Boos, K.-S., Nowak, D., Pethran, A., Schierl, R., Hauff, K., Grimm, C.-H., Boos, K.-S., & Nowak, D. (2003). Uptake of antineoplastic agents in pharmacy and hospital personnel. Part I: monitoring of urinary concentrations. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 76(1), 5–10. [CrossRef]

- Baniasadi, S., Alehashem, M., Yunesian, M., & Rastkari, N. (2018). Biological monitoring of healthcare workers exposed to antineoplastic drugs: Urinary assessment of cyclophosphamide and ifosfamide. Iranian Journal of Pharmaceutical Research, 17(4), 1458–1464. [CrossRef]

- Bray, F., Ferlay, J., Soerjomataram, I., Siegel, R. L., Torre, L. A., & Jemal, A. (2018). Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 68(6), 394–424. [CrossRef]

- 4. Cancer. (n.d.). Retrieved November 5, 2020, from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cancer.

- Connor, T. H. (2006). Hazardous anticancer drugs in health care: Environmental exposure assessment. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1076, 615–623. [CrossRef]

- Crul, M., Hilhorst, S., Breukels, O., Bouman-d’Onofrio, J. R. C., Stubbs, P., & van Rooij, J. G. (2020). Occupational exposure of pharmacy technicians and cleaning staff to cytotoxic drugs in Dutch hospitals. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Hygiene, 17(7–8), 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Dugheri, S., Bonari, A., Pompilio, I., Boccalon, P., Mucci, N., & Arcangeli, G. (2018). A new approach to assessing occupational exposure to antineoplastic drugs in hospital environments. Arhiv Za Higijenu Rada i Toksikologiju, 69(3), 226–237. [CrossRef]

- Graeve, C. U., McGovern, P. M., Alexander, B., Church, T., Ryan, A., & Polovich, M. (2017). Occupational Exposure to Antineoplastic Agents. Workplace Health and Safety, 65(1), 9–20. [CrossRef]

- Hall, A. L., Demers, P. A., Astrakianakis, G., Ge, C., & Peters, C. E. (2017). Estimating national-level exposure to antineoplastic agents in the workplace: CAREX Canada findings and future research needs. Annals of Work Exposures and Health, 61(6), 656–668. [CrossRef]

- Hazardous Drug Exposures in Health Care | NIOSH | CDC. (n.d.). Retrieved November 3, 2020, from https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/hazdrug/default.html.

- Hedmer, M., Tinnerberg, H., Axmon, A., & Jönsson, B. A. G. (2008). Environmental and biological monitoring of antineoplastic drugs in four workplaces in a Swedish hospital. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 81(7), 899–911. [CrossRef]

- Hon, C. Y., Teschke, K., Shen, H., Demers, P. A., & Venners, S. (2015). Antineoplastic drug contamination in the urine of Canadian healthcare workers. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 88(7), 933–941. [CrossRef]

- Loomis, D., Guha, N., Hall, A. L., & Straif, K. (2018). Identifying occupational carcinogens: An update from the IARC Monographs. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 75(8), 593–603. [CrossRef]

- Maeda, S., Miyawaki, K., Matsumoto, S., Oishi, M., Miwa, Y., & Kurokawa, N. (2010). Evaluation of environmental contaminations and occupational exposures involved in preparation of chemotherapeutic drugs. Yakugaku Zasshi, 130(6), 903–910. [CrossRef]

- Nyman, H., Jorgenson, J., & Slawson, M. (2007). Workplace Contamination with Antineoplastic Agents in a New Cancer Hospital Using a Closed-System Drug Transfer Device. Hospital Pharmacy, 42(3), 219–225. [CrossRef]

- Occupational exposure of pharmacy technicians and cleaning staff to cytotox...: EBSCOhost. (n.d.). Retrieved November 3, 2020, from http://web.a.ebscohost.com.periodicals.sgu.edu/ehost/detail/detail?vid=0&sid=96699d77-4514-4afd-99a7-8d31b5dfb0aa%40sdc-v-sessmgr03&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZQ%3D%3D#AN=32633703&db=mnh.

- Pałaszewska-Tkacz, A., Czerczak, S., Konieczko, K., & Kupczewska-Dobecka, M. (2019). Cytostatics as hazardous chemicals in healthcare workers’ environment. International Journal of Occupational Medicine and Environmental Health, 32(2), 141–159. [CrossRef]

- Peters, C. E., Ge, C. B., Hall, A. L., Davies, H. W., & Demers, P. A. (2015). CAREX Canada: An enhanced model for assessing occupational carcinogen exposure. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 72(1), 64–71. [CrossRef]

- Pethran, A., Schierl, R., Hauff, K., Grimm, C.-H., Boos, K.-S., & Nowak, D. (2003). Uptake of antineoplastic agents in pharmacy and hospital personnel. Part I: monitoring of urinary concentrations. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 76(1), 5–10. [CrossRef]

- Rai, R., Fritschi, L., Carey, R. N., Lewkowski, K., Glass, D. C., Dorji, N., & El-Zaemey, S. (2020). The estimated prevalence of exposure to carcinogens, asthmagens, and ototoxic agents among healthcare workers in Australia. American Journal of Industrial Medicine, 63(7), 624–633. [CrossRef]

- Ramphal, R., Bains, T., Goulet, G., & Vaillancourt, R. (2015). Occupational exposure to chemotherapy of pharmacy personnel at a single centre. Canadian Journal of Hospital Pharmacy, 68(2), 104–112. [CrossRef]

- Ratner, P. A., Spinelli, J. J., Beking, K., Lorenzi, M., Chow, Y., Teschke, K., Le, N. D., Gallagher, R. P., & Dimich-Ward, H. (2010). Cancer incidence and adverse pregnancy outcome in registered nurses potentially exposed to antineoplastic drugs. BMC Nursing, 9. [CrossRef]

- Scarselli, A., Montaruli, C., & Marinaccio, A. (2007). The Italian information system on occupational exposure to carcinogens (SIREP): Structure, contents and future perspectives. Annals of Occupational Hygiene, 51(5), 471–478. [CrossRef]

- Shahrasbi, A. A., Afshar, M., Shokraneh, F., Monji, F., Noroozi, M., Ebrahimi-Khojin, M., Madani, S. F., Ahadi-Barzoki, M., & Rajabi, M. (2014). Risks to health professionals from hazardous drugs in Iran: A pilot study of understanding of healthcare team to occupational exposure to cytotoxics. EXCLI Journal, 13, 491–501. [CrossRef]

- Sottani, C., Porro, B., Imbriani, M., & Minoia, C. (2012). Occupational exposure to antineoplastic drugs in four Italian health care settings. Toxicology Letters, 213(1), 107–115. [CrossRef]

- Sugiura, S. I., Asano, M., Kinoshita, K., Tanimura, M., & Nabeshima, T. (2011). Risks to health professionals from hazardous drugs in Japan: A pilot study of environmental and biological monitoring of occupational exposure to cyclophosphamide. Journal of Oncology Pharmacy Practice, 17(1), 14–19. [CrossRef]

- Wild, C. P. (2019). The global cancer burden: necessity is the mother of prevention. In Nature Reviews Cancer,19(3), 123–124. [CrossRef]

- Yu, E. (2020). Occupational Exposure in Health Care Personnel to Antineoplastic Drugs and Initiation of Safe Handling in Hong Kong. Journal of Infusion Nursing, 43(3), 121–133. [CrossRef]

| Study | Metdod | Study population (number) | Exposure drug assessed relevant to tdis review |

Number of persons exposed/ samples tested |

Limit of detection (LOD) | Results | Prevalence ratio |

| (Ae et al., 2003) |

Cross sectional | Nurses (87) Pharmacists (13) |

CP IFO |

100 persons exposed 670 samples tested: Nurses (589) Pharmacists (81) |

CP: 0.04 mcg/L IFO: 0.05 mcg/L |

Urine samples tested (670): Nurses: 11 positive samples for either CP or IFO Pharmacists: 31 positive samples for either CP or IFO CP: 72 samples >LOD IFO: 20 samples >LOD The concentrations of CP in urine ranged from 0.05 to 0.76 mcg/L, and IFO peaked at 1.90 mcg/L. |

Nurses: 0.02 (2%) Pharmacists: 0.38 (38%) Samples >LOD for CP: 0.11 (11%) Samples >LOD for IFO: 0.03 (3%) CP>IFO |

| (Hedmer et al., 2008) |

Cross sectional |

Nurses (15) Pharmacists (3) Other (4) |

CP IFO |

22 persons exposed |

CP: 10 ng/L IFO: 30 ng/L |

Drugs handled during biological monitoring: Nurses CP: average of 1.1g/day (range 0-5g) IFO: average of 2.4g/day (range 0-20g) Pharmacists CP: average of 12 g/day (range 2–36 g) IFO: average of 24 g (range 0–25 g) Drugs detected in urine during biological monitoring: Nurses: no CP/IFO detected in urine Pharmacists: no CP/IFO detected in urine |

Samples > LOD in urine: 0 Handling: IFO>CP Pharmacists>nurses |

| (Hon et al., 2015) |

Cross sectional | Nurses (29) Pharmacists (43) Others (31) |

CP | 103 persons, 98 provided a second sample, for a total of 201 urine samples |

CP: 0.05 ng/mL | Urinary concentrations of CP (in ng/mL): Slightly more than half of the samples (55 %) had CP levels greater than the LOD with a maximum reported concentration of 2.37 ng/mL The mean urinary CP concentration was 0.156 ng/mL |

Nurses: 0.56 (56%) of samples were >LOD Pharmacists: 0.44 (44%) of samples were >LOD |

| (Sottani et al., 2012) | Cross sectional | Nurses (78) Pharmacists (22) |

CP IFO |

100 persons | Not stated | CP or IFO not detected in urine | CP: 0 IFO: 0 |

| (Baniasadi et al., 2018) | Cross sectional | Nurses Nursing assistant |

CP IFO |

30 (1 sample per person) | Not stated | CP: 14 samples had detectable levels IFO: 5 samples had detectable levels CP and IFO concentrations were highest among nurses that administered these drugs |

CP: 0.466 (46.66%) IFO: 0.066 (6.66%) |

| Study | Metdod | Study population/ area |

Exposure drug assessed relevant to tdis review |

Surface samples collected | Limit of detection (LOD) | Results | Prevalence ratio |

| (Graeve et al., 2017) |

Cross sectional | Nursing station Physician work area Pharmacy |

CP MTX IFO |

62 | CP: 0.015 ng/cm2 MTX: 0.005 ng/cm2 IFO: 0.005 ng/cm2 |

Five (5) samples tested above the limit of detection for different antineoplastic agents Nursing station areas: 4 samples > LOD IFO >LOD in 3 samples at 0.06 ng/cm2 MTX was <LOD 1 sample tested above the LOD for a neoplastic agent not in this review Physician workroom areas: CP and IFO were <LOD Pharmacy areas: CP was <LOD 1 sample tested above the LOD for an antineoplastic agent not in this study |

Samples >LOD: 0.08 (8%) Nursing station samples >LOD: 0.06 (6%) Physician workroom samples >LOD: 0 Pharmacy area samples >LOD: 0.02 (2%) IFO>CP & MTX |

| (Hedmer et al., 2008) |

Cross sectional |

Oncology wards (231) Pharmacy (104) |

CP IFO |

335 | CP: 0.02 ng per wipe sample IFO: 0.05 ng per wipe sample |

Wipe sampling: Hospital oncology wards CP: ranged from not detectable (ND) – 3800pg cm2 IFO: ranged from ND – 2700pg cm2 Hospital pharmacy floor and work area CP: ranged from 2.2 – 45pg cm2 IFO: ranged from 11 – 78pg cm2 Measurable amounts of CP and IF were detected on most of the sampled surfaces |

Wards: 0.86-1.0 (86-100%) of samples were > LOD for CP 0.29-1 (29-100%) of samples were >LOD for IFO Pharmacy: 1.0 (100%) of samples were > LOD for both CP & IFO |

| (Ramphal et al., 2015) |

Cross sectional | Oncology pharmacy Main pharmacy (control) |

CP MTX IFO |

Not stated | Not stated | Wipe sampling before cleaning in oncology pharmacy CP: 0.08ng/cm2 MTX: 0.66ng/cm2 IFO: not measured Wipe sampling after cleaning in oncology pharmacy CP: ND-0.04ng/cm2 MTX: 0.25ng/cm2 IFO: 0.009ng/cm2 Wipe sampling in main pharmacy (control) CP: ND MTX: ND IFO: ND The before-cleaning surface wipes from the oncology pharmacy revealed CP contamination in 3 of 5 areas tested and MTX contamination in 1 of 6 areas tested |

CP: 0.6 (60%) MTX: 0.17 (17%) |

| (Dugheri et al., 2018) | Cross sectional | Nine (9) hospitals across Italy | CP MTX IFO |

4814 | Not stated | 1583 (32%) were above the LOD CP: 864 positive samples IFO: 762 positive samples MTX: 28 positive samples |

CP: 17.2% IFO: 15.4% MTX: 0.8% CP>IFO>MTX |

| (Sottani et al., 2012) | Cross sectional | Eight (8) pharmacies Nine (9) patient areas |

CP IFO |

Not stated | Not stated | Samples contaminated with antineoplastic agent: CP: 54% of samples IFO: 19% of samples |

CP: 0.54 (54%) IFO: 0.19 (19%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).