1. Introduction

Compartmental mathematical models are very popular and successful to describe the temporal evolution of pandemic and epidemic outbursts in populations of large size (for reviews see ref. [

1,

2,

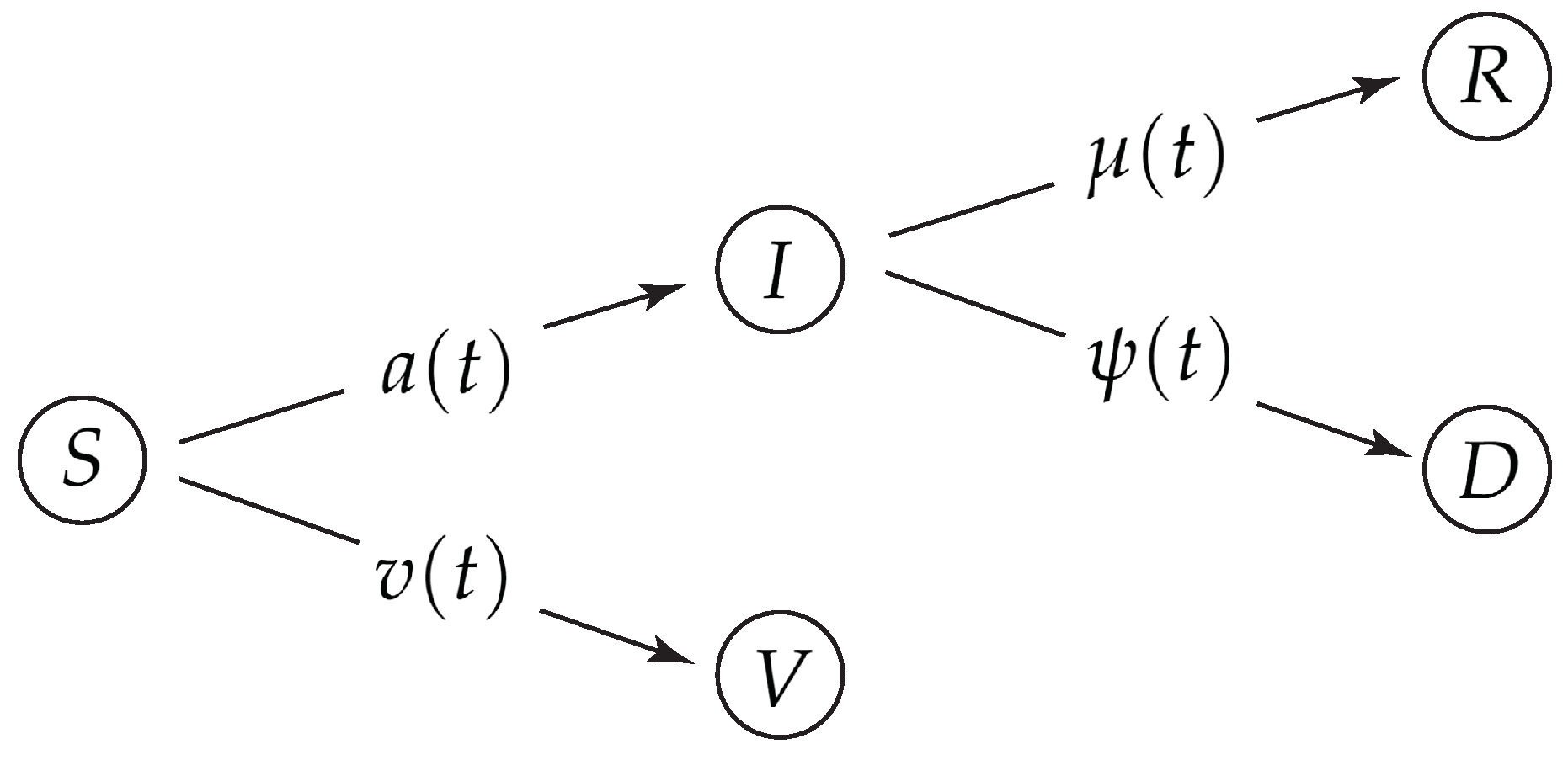

3]). Their forecasts on hospitalization and death rates help policy makers to install non-pharmaceutical interventions and/or vaccination campaigns at optimized times. As suitable compartments one introduces the fractions of susceptible persons (

S), infected persons (

I), recovered persons (

R), deceased persons (

D), and vaccinated persons (

V) that no longer can be infected. Individual time-dependent rates regulate the transition between the different compartments. The temporal evolution of the epidemic is then determined by the ratios

,

and

between the recovery (

), vaccination (

) and fatality (

) rates to the infection (

) rate, respectively. By discriminating e.g. between different age classes in each compartment these models can be generalized to a much larger number of compartments in order to investigate the effects of pandemic and epidemic outbursts on persons of certain age groups. However, from the health care point of view to provide sufficiently enough intensive care beds and facilities is independent from the age of the infected persons.

Historically, the first reasonable compartment model was the susceptible–infected–recovered/removed (SIR) epidemic model [

4,

5,

6,

7]. This has been refined to include the effect of vaccination campaigns leading to the susceptible–infected–recovered/removed–vaccinated (SIRV) epidemic model [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. The purpose of this manuscript is two-fold. First we will investigate new classes of exact solutions to the SIRVD and SIRD equations. Secondly we will apply the recently developed analytical approximation [

20,

21] for the SIR and SIRV models also to the more general SIRVD model. These accurate analytical approximations have been derived for all epidemic quantities of interest such as the rate of new infections

and the corresponding cumulative fraction of infections

. The main difference between the SIRVD and the SIRV model is the discrimination between recovered and deceased persons by introducing two different compartments. This is necessary as the omicron mutant the COVID-19 has a much smaller (about an order of magnitude) fatality rate than earlier mutants [

22]. This gradually changing fatality rate is not accompanied by a corresponding change in the time dependence of the recovery rate. Therefore a mathematical description with one combined recovery/removed compartment is not sufficiently accurate anymore.

The organization of the manuscript is as follows. In

Section 2, we introduce the starting dynamical equations for all considered compartment models both in terms of the real time

t and the reduced time

. It is beneficial for the analysis to express the equations in a form directly involving the observable quantities, such as the cumulative fraction of new infections

and the cumulative fraction of vaccinated persons

. It is shown that for given reduced time variations of the ratios

,

and

the SIRVD and SIRD equations represent complicated integro-differential equations for the rate of new infections

as well as the cumulative fraction of infections

, or

and

. However, the integro-differential equations can also be regarded as simpler determining equations for the sum of ratios

for given variations of the ratio

and the fraction

. This new approach is used in

Section 3 to derive fully exact analytical solutions for the SIRVD and SIRD models. Especially for the SIRD model it is an effective new method to construct a special class of exact solutions depending on two parameters which are chosen as the values of the ratio

at the start (

) and the end (

) of the epidemic outburst. The new method for the SIRD case is illustrated in

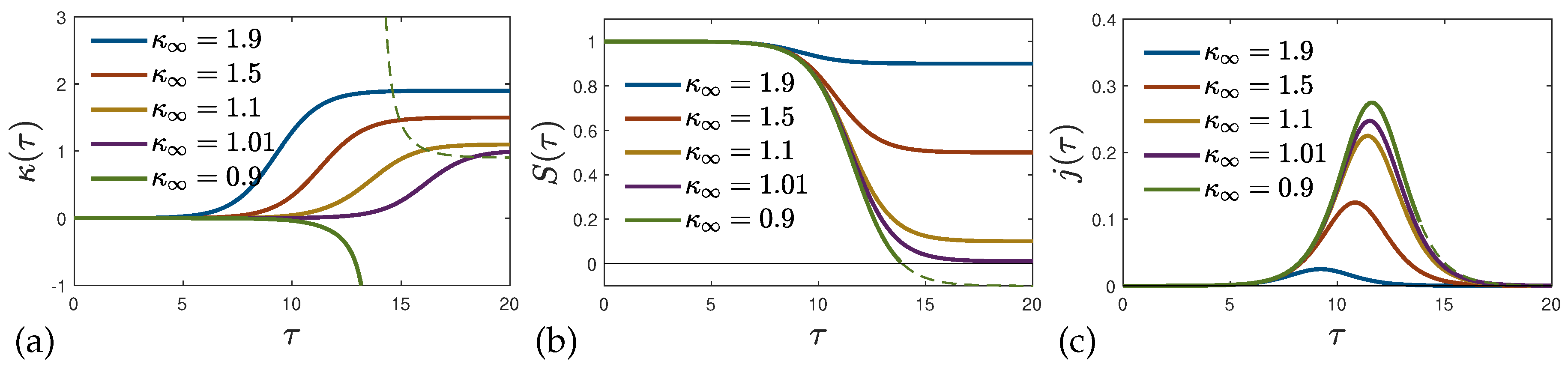

Section 4 for three different choices of the two parameters including a detailed investigation of the properties of the constructed solutions.

Section 5 and

Section 6 are concerned with the second main purpose of this manuscript, namely the application of the approximate analytical solution in the limit of small cumulative fractions

to the SIRVD model. For general reduced time dependencies of the ratios

,

and

the time dependence of all quantities of interest is derived in

Section 5, whereas in

Section 6 two applications are investigated which were inaccessible to analytical treatment before. Of special interest is the calculation of the death rate

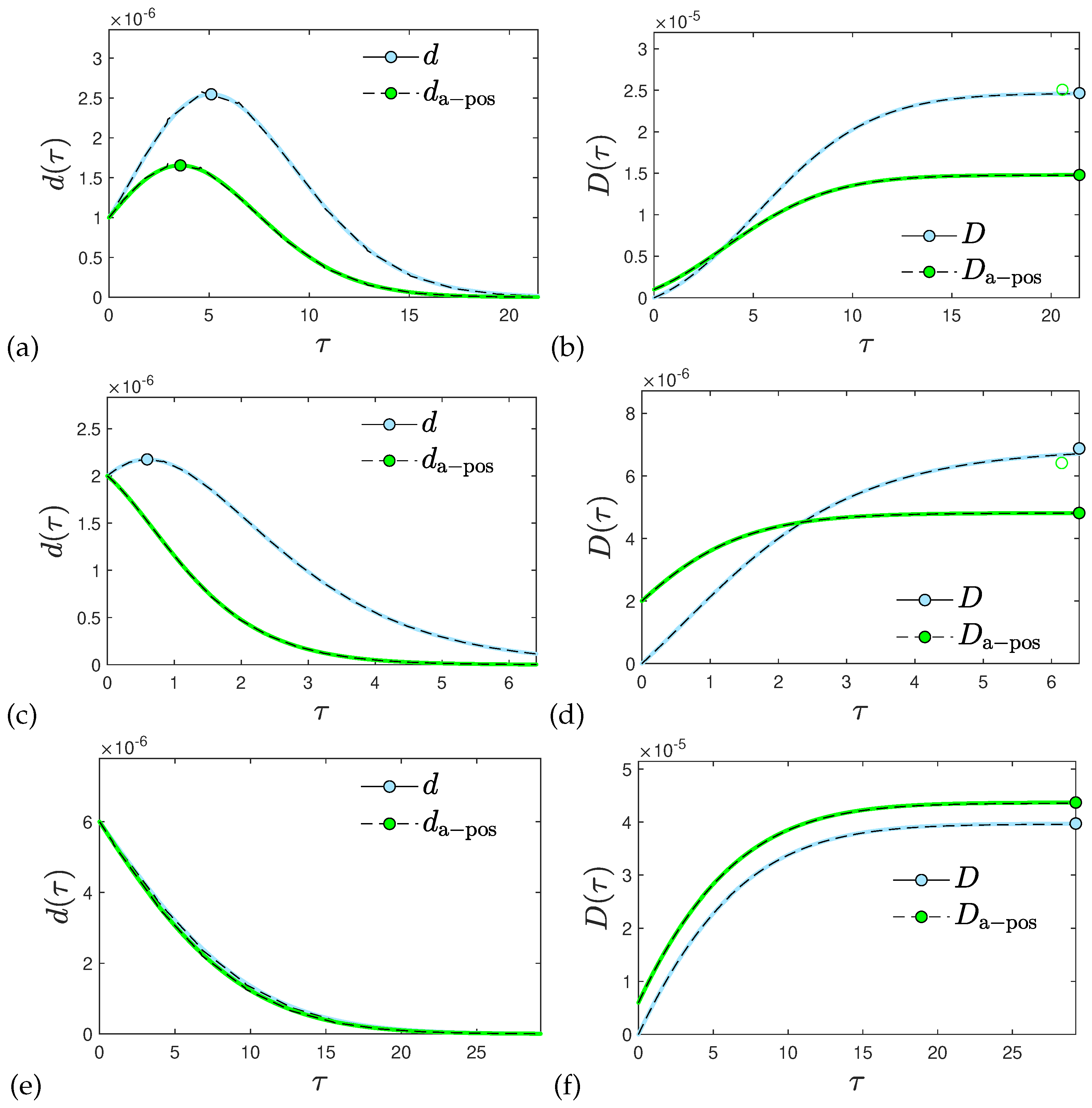

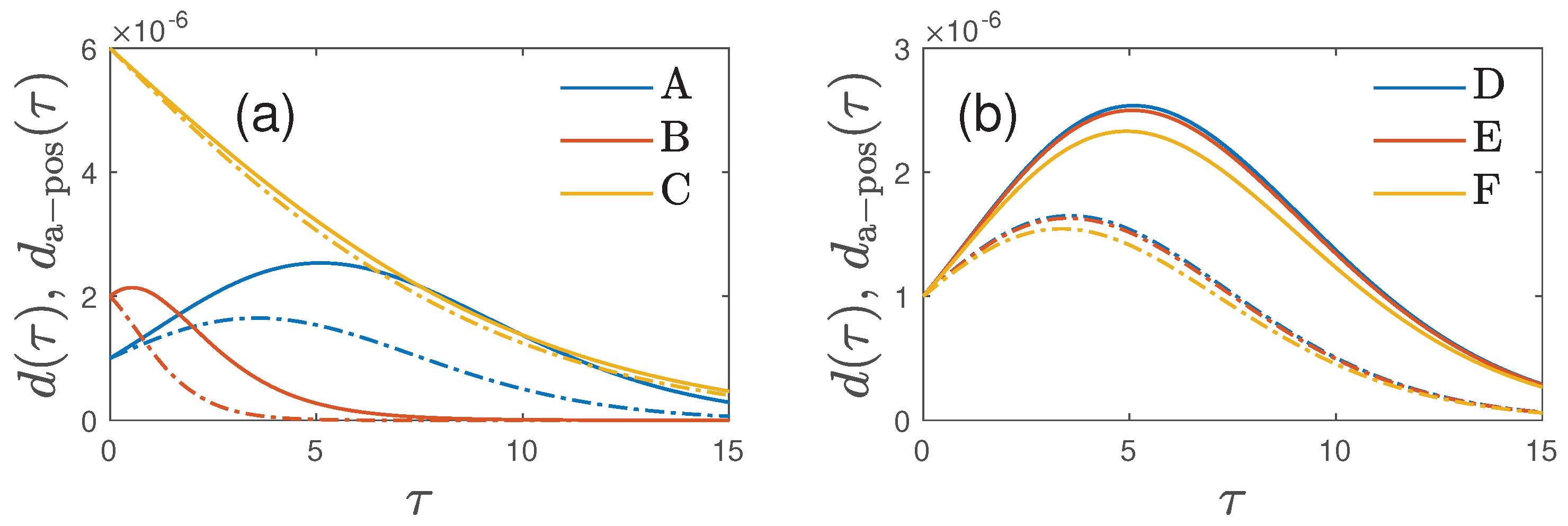

and the corresponding cumulative fraction of deceased persons

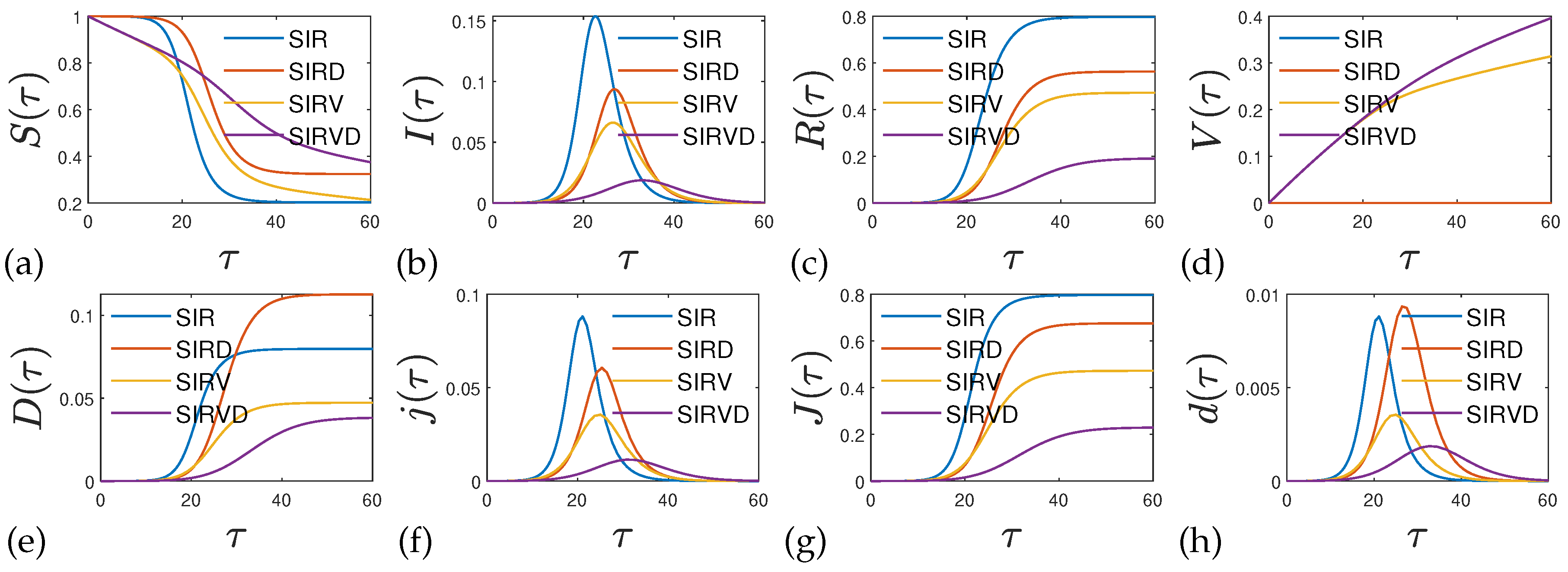

. Main differences occur between the considered compartment models which reflect two alternative points of view.

In the SIRVD and SIRD case with a predescribed fatality rate

, corresponding to the ratio

, the death rate is proportional to the fraction

. Moreover, any different reduced time dependencies of the ratios

and

correctly enter the dynamical equations. In contrast, in the SIR models no compartment of deceased persons has been considered. Instead the total fraction of recovered and removed (by death) populations

and the summed recovery/removed rate

are used. Then the solution for the rate of new infections

is employed to calculate an

a posteriori death rate as [

6]

from a specified fatality rate

. Of course, this fatality rate can be regarded as part of the summed recovery/removed rate, so that it also enters the dynamical SIR model equations. However, the main difference remains for the calculation of the death rate: in the SIRVD/SIRD cases it is proportional to

, whereas in many SIR models it is proportional to

. And the temporal dependence of

and

can be different. As we will show the disparity is most pronounced when the effect of vaccinations is included and/or when the real time dependence of the fatality rate

and the recovery rate

are different from each other. The a-posteriori approach not necessarily is incorrect but has his own justification. It assumes that the probability to die from the virus infection is only determined by being or having been infected with it, and thus is proportional to the rate of new infections

. In contrast in the SIRD and SIRVD models the probability to die is the same on every day being infected and thus depends on the duration of the infection. A summary and conclusion (

Section 7) completes the manuscript.

3. Special Exact Solutions

Equations (

28)–(

31) are complicated integro-differential equations in the SIRVD and SIRD case, respectively, for given reduced time variations of the ratios

,

and

. Hovever, they can also be regarded as simpler determining Equations for the ratios

for given variations of the ratio

and the fraction

. This can be used to derive fully exact analytical solutions for the SIRVD and SIRD models.

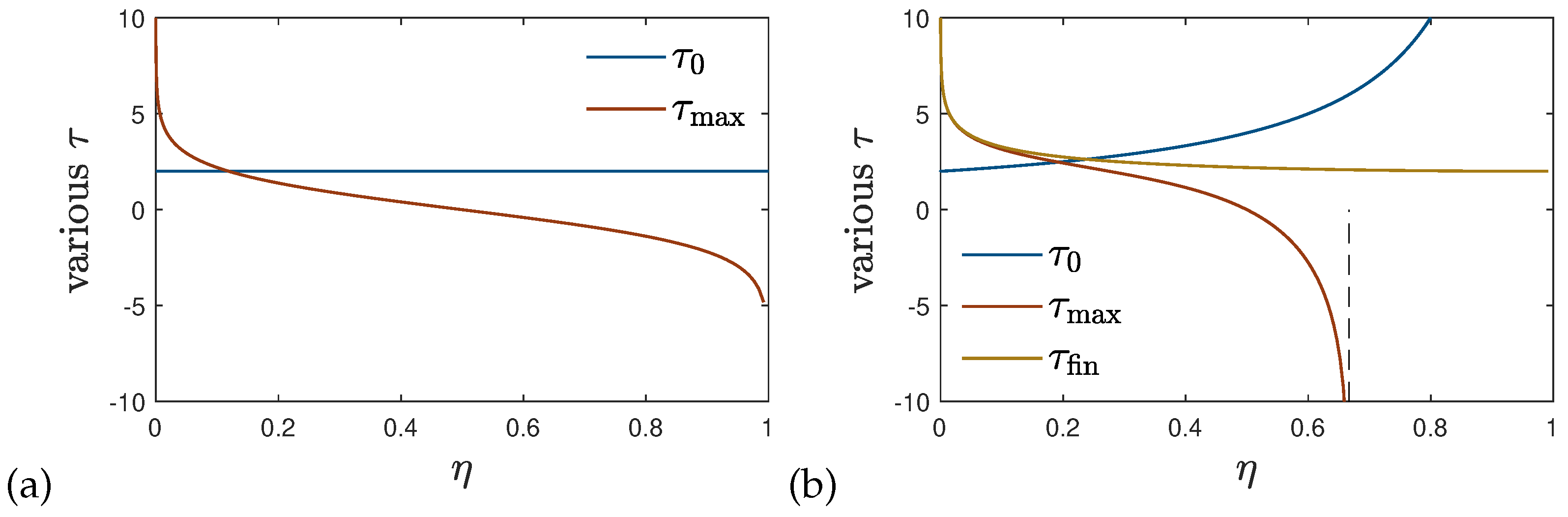

We know that

starts from the initial values

and monotonically decreases to its final nonnegative value

after finite or infinite time. We also require, in accord with Equation (

12) and the initial conditions specified in

Section 2.3, that

Therefore we adopt the reduced time variation

parameterized by

,

, and

. While

is formally correct,

may reach zero after finite time

. In that case

, irrespective of the value of the parameter

, that may therefore take positive or negative values in the expression (

36). One has

1

from Equation (

36). Only if the argument of the

resides in the interval

, a finite

exists. We are going to see that the special choice of

has to be treated with care; it will allow us to absorb with Equation (

36), along with a particular choice for

, the analytic solution of the SI model, for which

reaches

at

. Moreover, the initial condition

will be used to establish a relationship between

,

, and

.

We adopt without loss of generality positive values of

. The choice (

36) implies

With the first Equation (

15) we obtain for the dynamical SIRVD equation (

28)

After inserting Equations (

36) and (38b) this Equation becomes

For given reduced time variations

the combined rate (

40) corresponding to the fraction

in Equation (

36) can be inferred. In the following we simplify our analysis to the SIRD model.

3.1. SIRD Model

The choice (

36) implies for the SIRD model

,

and

The rate (

41a) is of generalized SI-type (see Equation (

A5)) with a width

different from 2 and a general

different from

. We thus investigate for which conditions generalized SI-type rates exactly solve the SIRDequations.

The requirement (

35) demands

We emphasize that the ansatz (

41a) includes the SI model as special case. Inserting the SI-values

,

,

and

, which follows from Equation (

42) for

, it is straightforward to show that Equation (

41a) correctly reproduces the SI-distribution (

A5).

The first Equation (

41a) then can be written as

Only for

the maximum rate of new infections at

is much larger than the initial value

. In this limit

while Equation (

39) for

simplifies to

Within the remainder of this subsection, we use the simplifying abbreviations

to derive expressions for

and

for the two qualitatively different cases of

and

. With the help of Equation (

47) the SIRDequation (

36) receives the form

or equivalently, upon replacing

using Equation (

42),

Similarly, using Equation (38c) in Equation (

46),

becomes

Using

, the initial value

can be read off from Equation (

50). This yields

where we inserted

from (

42) to arrive at the 2nd line in Equation (

51). Expression (

51) is valid for any

.

As long as

, the final value

can be also read off immediately from Equation (

50). While the last term in Equation (

50) diminishes with increasing

Y due to the leading

, the first terms readily evaluate upon replacing

by unity, so that

where we made use again of

from (

42). Calculating

for the remaining case of

requires more care, as the denominator in the last line of Equation (

50) does not anymore increase with increasing

Y. For

, one instead finds

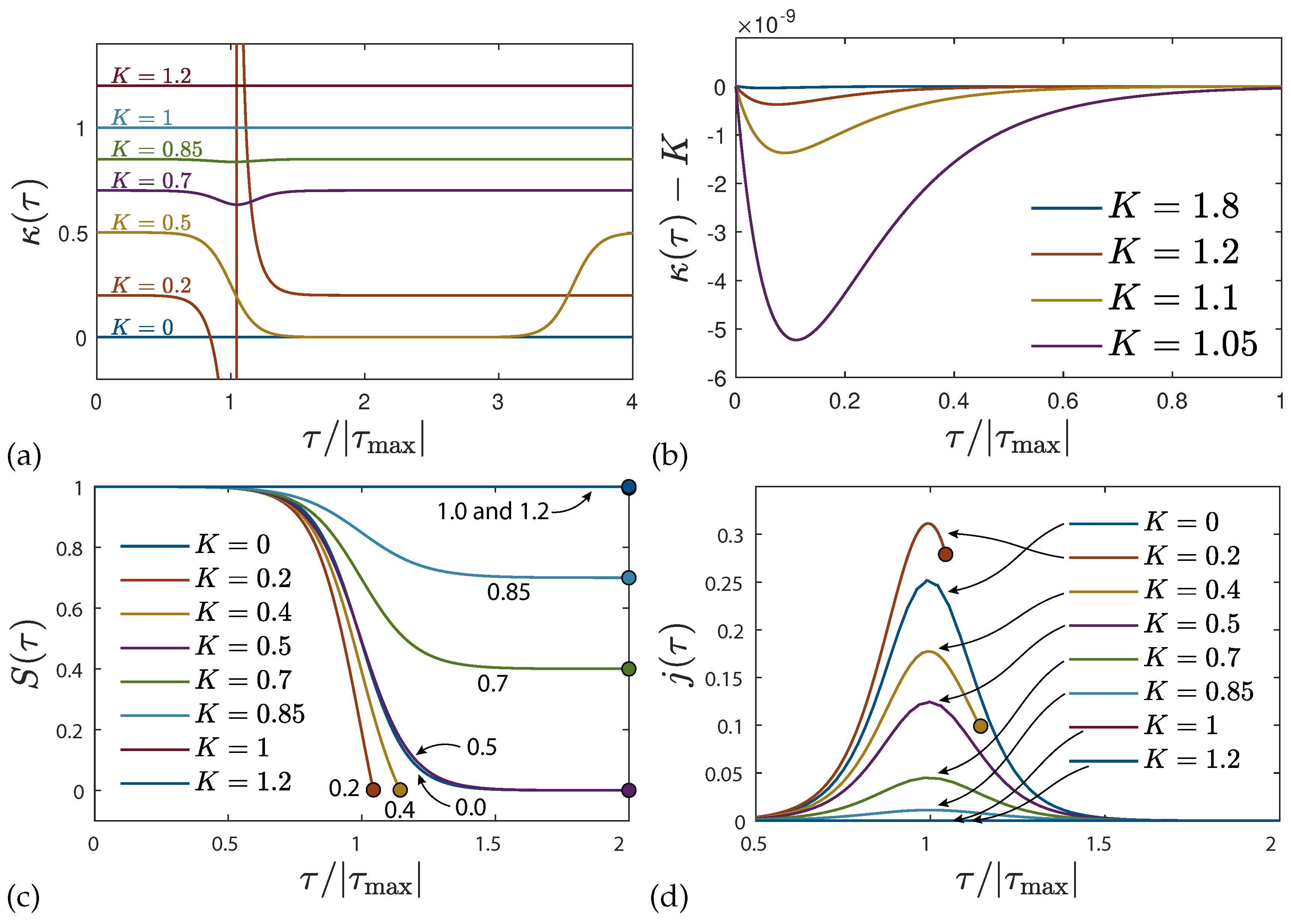

Note the apparent qualitative difference between the two cases. While for , one has for .

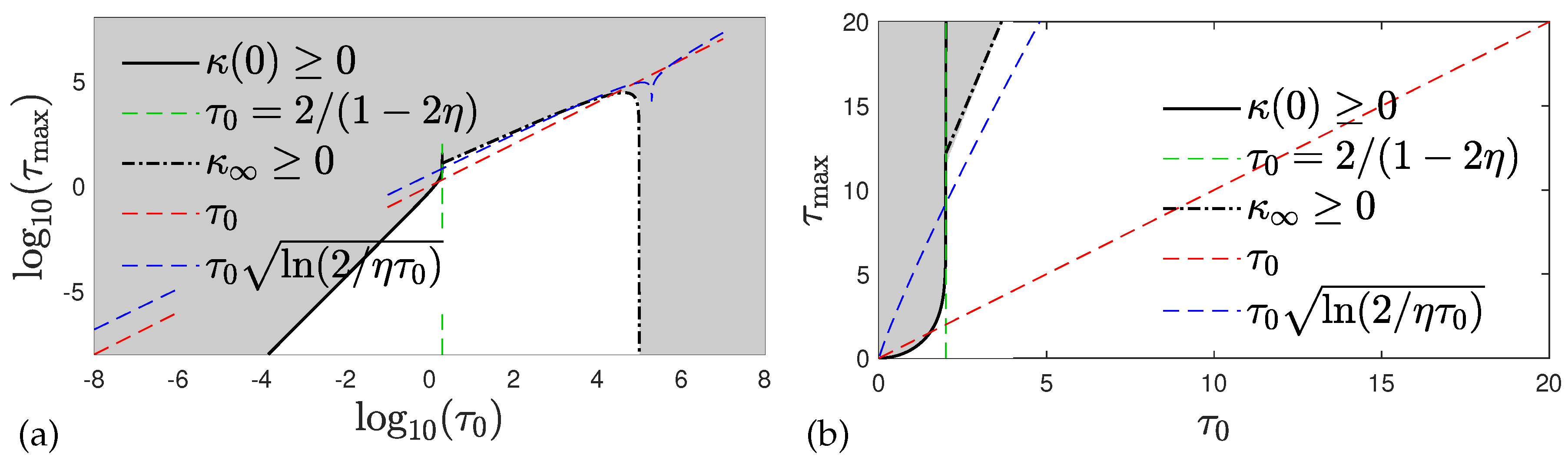

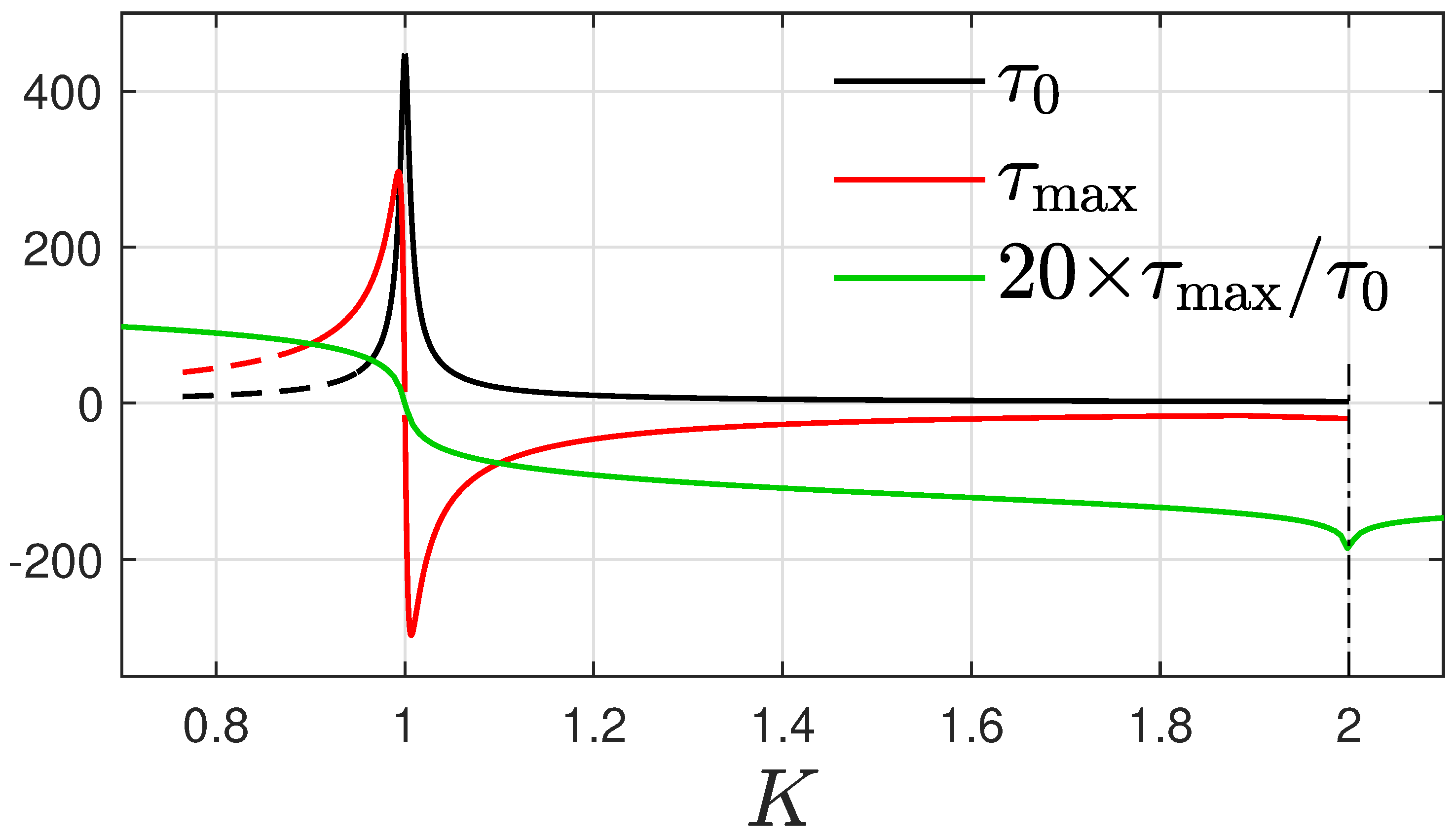

3.2. Constraints on the Function

We recall that values of the function smaller than unity describe the epidemic phase where the infection rate is larger than the sum of the recovery and death rate. Hence if still enough susceptible persons are available one expects a rising rate of new infections . In the opposite case of values of the function greater than unity the sum of recovery and death rates outnumbers the infection rate so that the rate of new infections will decrease in such a phase. Therefore it is appropriate to start with values of the function smaller than unity at small reduced times. Subsequently, the function approaches the value at infinitely large reduced times which can be either smaller or greater than unity depending on the chosen values of and . However, not all values for and are allowed.

The requirement of having a positive

leads to

This is automatically fulfilled for values of

as the right-hand-side of Equation (

55) is always smaller or equal than unity. For values of

it is required that

The inequality

, corresponding to

, is met as long as the following inequalities hold,

that follow from Equation (

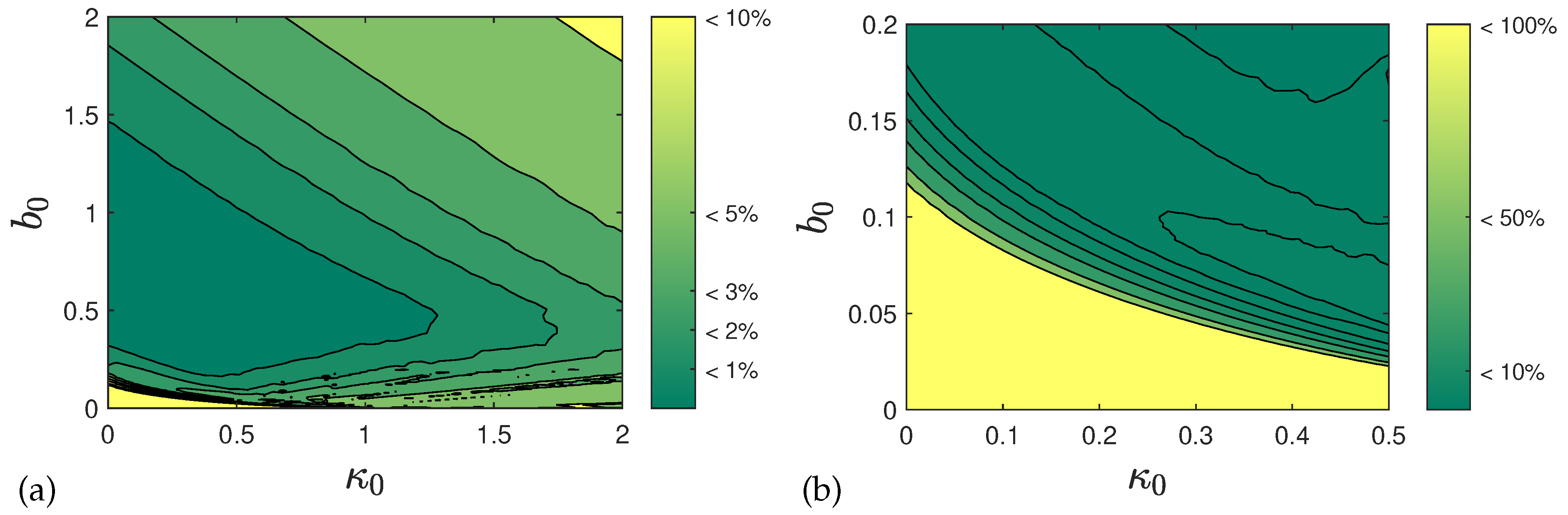

42). This condition (58), the regime between red and blue dashed lines in

Figure 3, is not compatible with condition (

56) but holds for certain values of

. The condition (

57) further guarantees that also

, and not only

, is non-negative at all times because

requires, according to Equation (

49),

or

which is fulfilled for

all times

because the left-hand side is always smaller than unity while the right-hand side is larger than unity due to condition (

57). In cases

, where the condition (

57) is not fulfilled,

vanishes at the finite time

already stated in Equation (

37). In this case the chosen solution (

36) or (

49) can only be used in the finite time interval

.

Equation (

50) can also be written as

where we used the identity

The function (

61) is positive for

and non-negative for all times in the admissible interval

. The ratio

is negative and contains singularities if it is used in the regime

.

7. Summary and Conclusions

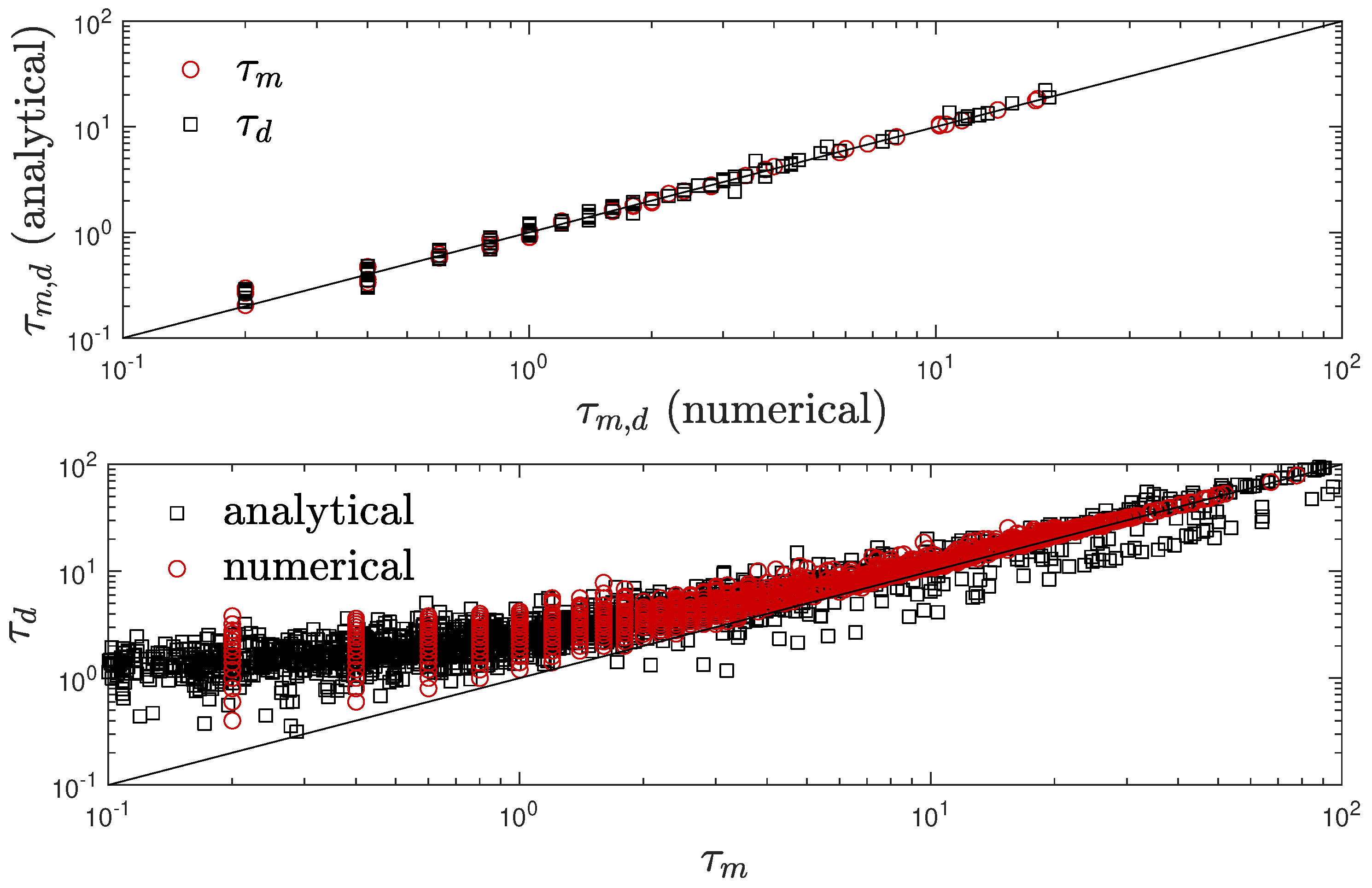

We have investigated a special class of exact solutions as well as accurate analytical approximations of the SIRVD and SIRD compartment models. For nonlinear models with a high-dimensional parameter space analytical solutions, exact or accurately approximative, are of high importance and interest: not only as suitable benchmarks for numerical codes, but especially as they allow us to understand the critical behavior of epidemic outbursts as well as the decisive role of certain parameters [

30]. For given reduced time variations of the ratios

,

and

the SIRVD and SIRD equations represent complicated integro-differential equations for the rate of new infections

as well as the cumulative fraction of infections

, or

and

. However, the integro-differential equations can also be regarded as simpler determining equations for the sum of ratios

for given variations of the ratio

and the fraction

. This new approach has been used to derive fully exact analytical solutions for the SIRVD and SIRD models. Especially for the SIRD model it is an effective new method to construct a special class of exact solutions depending on two parameters which are chosen as the values of the ratio

at the start (

) and the end (

) of the epidemic outburst. The new method for the SIRDcase is illustrated in

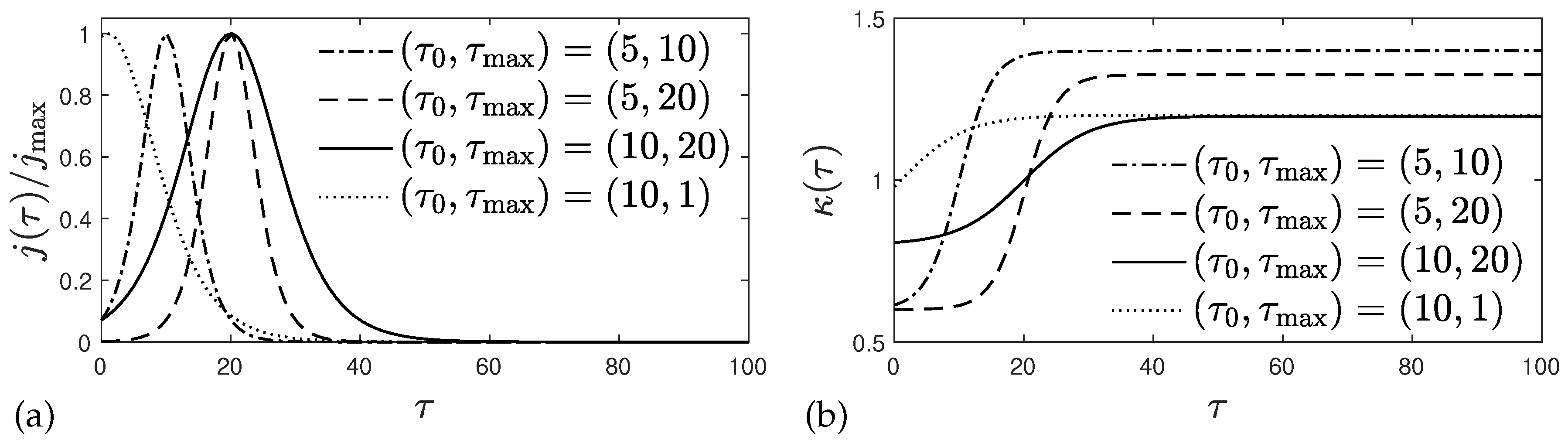

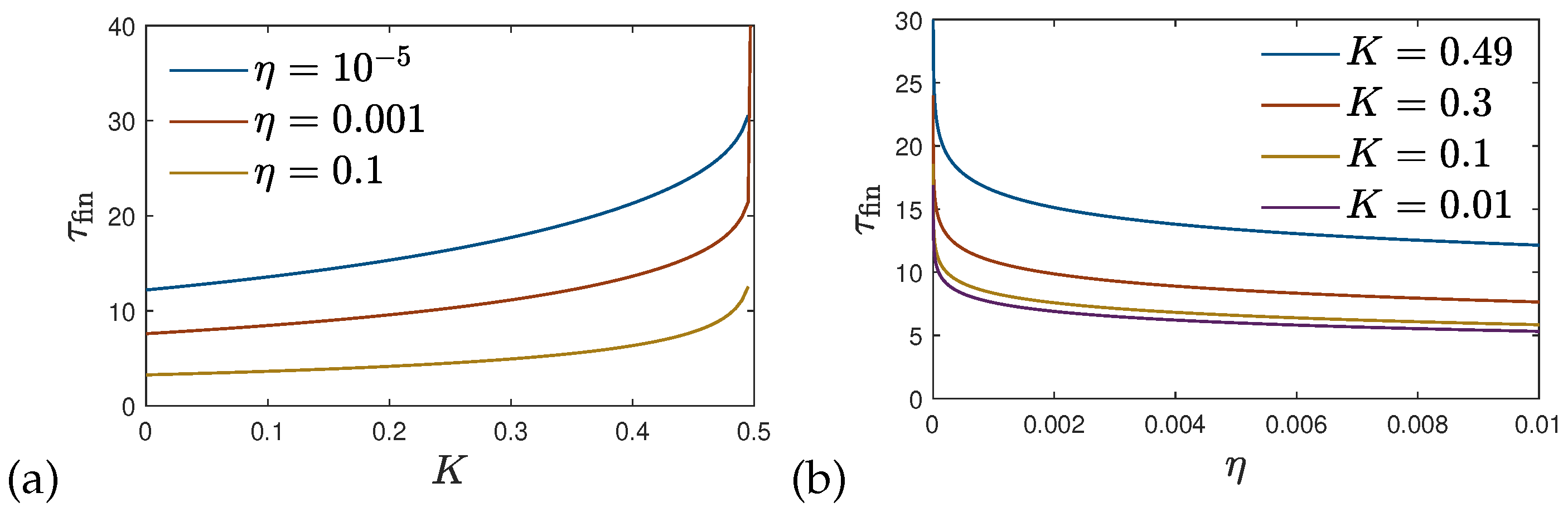

Section 4 for three different choices of the two parameters including a detailed investigation of the properties of the constructed solutions. Particular interesting are the cases where the combined ratio

at the start and the end of the epidemic outburst have values below

which corresponds to infection rates being twice as large as the sum of the recovery and fatality rate. In this case the epidemic outburst, described by the SI-type

-distribution for the rate of new infections, is so dominated by the rapid infections that at the finite reduced time

the outburst suddenly terminates as with

no more persons are available to be infected. The situation is comparable to a smooth running car where suddenly the car engine stops as no more fuel is available. For values greater than

the epidemic outburst lasts until infinitely large times.

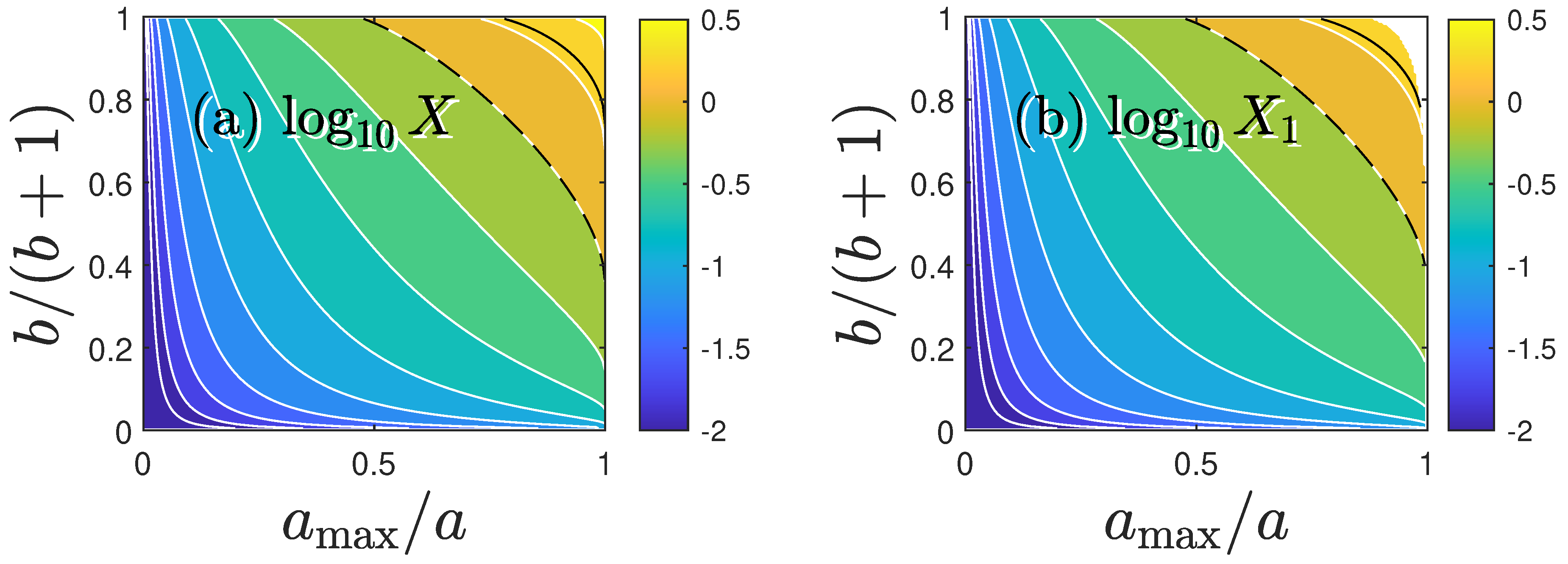

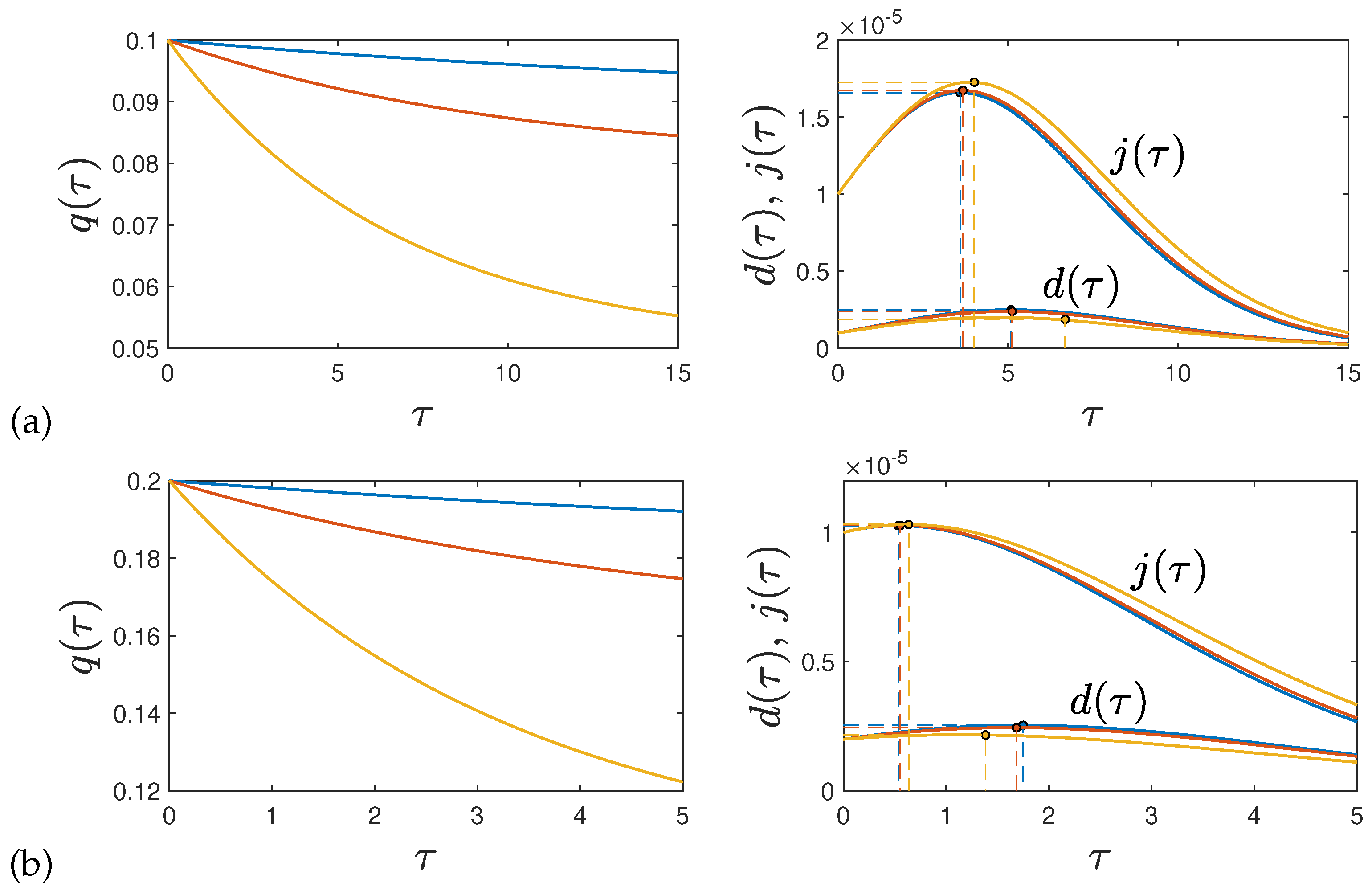

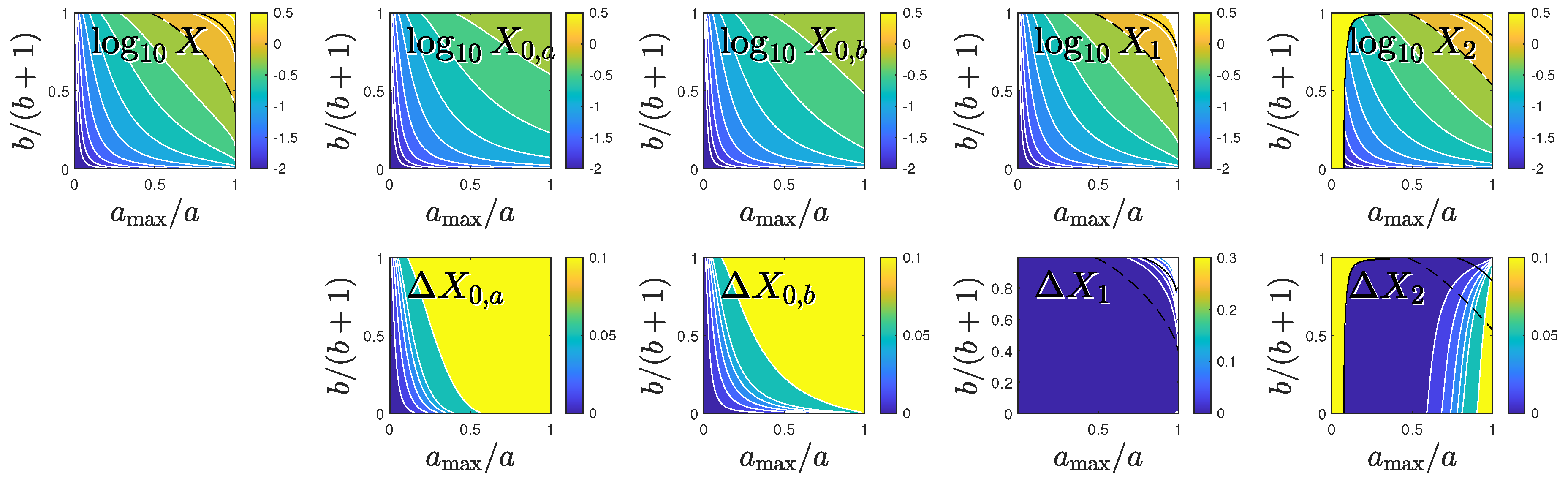

In the second part of the manuscript the recently developed analytical approximation [

20,

21] for the SIR and SIRV models are applied to the more general SIRVD model. In the limit of small cumulative fractions

, which very often is fulfilled, this approximation provides accurate analytical expressions for all epidemic quantities of interest such as the rate of new infections

and the fraction

of infected persons. As an aside, when determining

in

Appendix C we provided accurate approximative solutions to Wright’s transcendental equation (

A16), or equivalently, Equation (

178). The main difference of the SIRVD to the SIRV model is the discrimination between recovered and deceased persons by introducing two different compartments which affects the calculation of the death rate. In the SIRVD/SIRD cases it is proportional to

, whereas in many SIR models in an a-posteriori approach it is proportional to

. It is shown that the temporal dependence of

and

are different when the effect of vaccinations is included and/or when the real time dependence of the fatality rate

and the recovery rate

are different from each other. We illustrate these pronounced differences with two applications: one for stationary ratios

,

and

, and one for stationray ratios

but a gradually decreasing fatality rate. In our analysis, we observe earlier peak-times for the rate of newly infected individuals compared with death rates. Additionally, our findings indicate significantly smaller death rates compared with those obtained through the a-posteriori treatment. We are hopeful that these differences can be corroborated with past monitored pandemic data on the rate of new infections and the death rates of sufficient quality, with negligible underestimation. We didn’t account for the widely acknowledged 7-day delay between the onset of infection and the resulting death. This delay impacts both the death rate in our SIRVD model and the subsequent a-posteriori death rate analysis in a consistent manner. As a result, the derived difference in peak times remains unchanged.