Submitted:

27 February 2024

Posted:

27 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Research Method

2.1. Tourism Resources Database

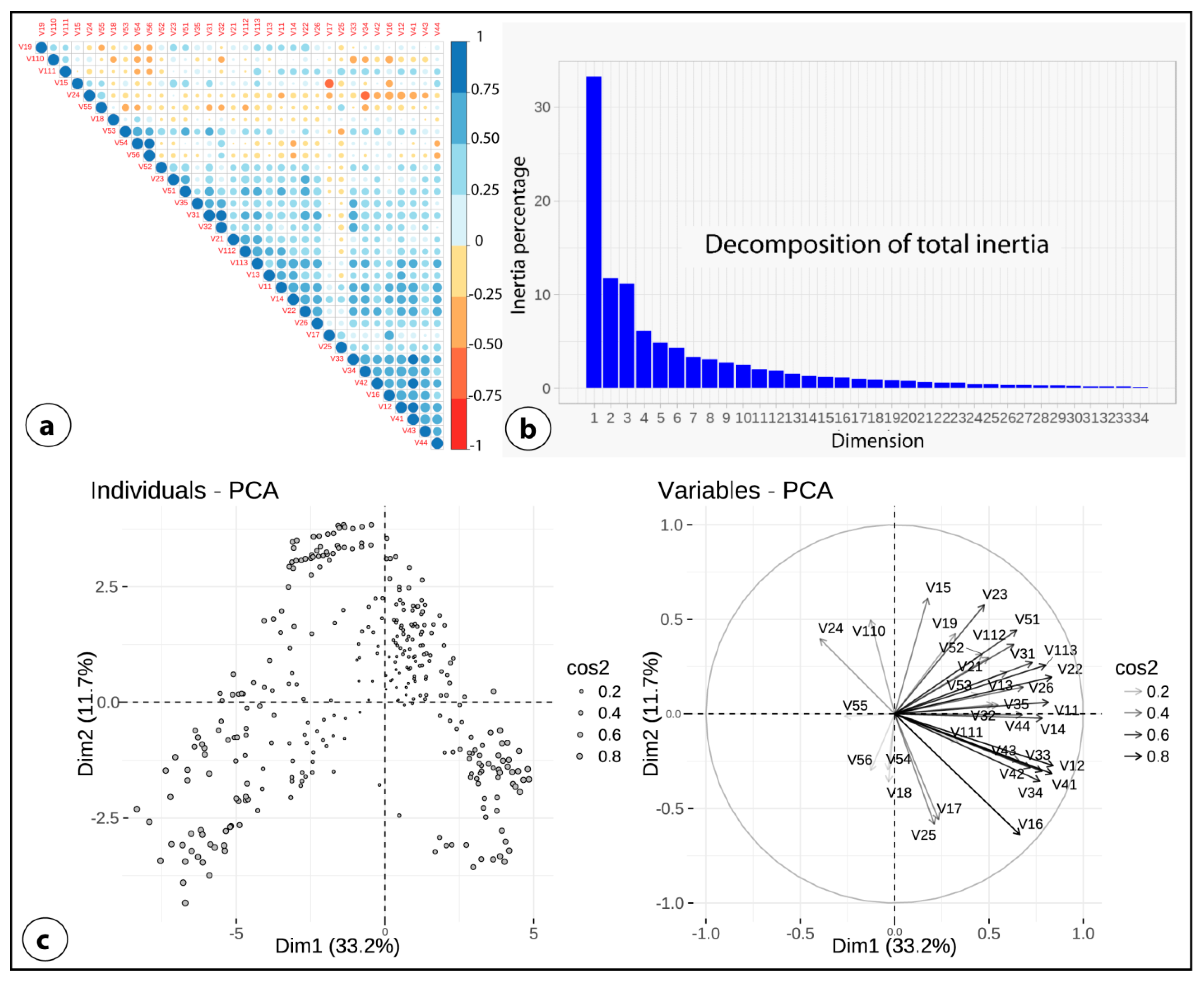

2.2. Quantitative Evaluation of Destination Choice Criteria and Tourist Typology

3. Results

3.1. Geomorphosite Features

3.1.1. Imi-n-Ifri Natural Bridge (X=6° 58’ 18 ’’ ; Y=31° 43’ 26’’ ; Z=1069 m)

3.1.2. Ait Bouguemez Valley (X=6°31’38’’ ; Y=31°37’59’’; Z=2080 m)

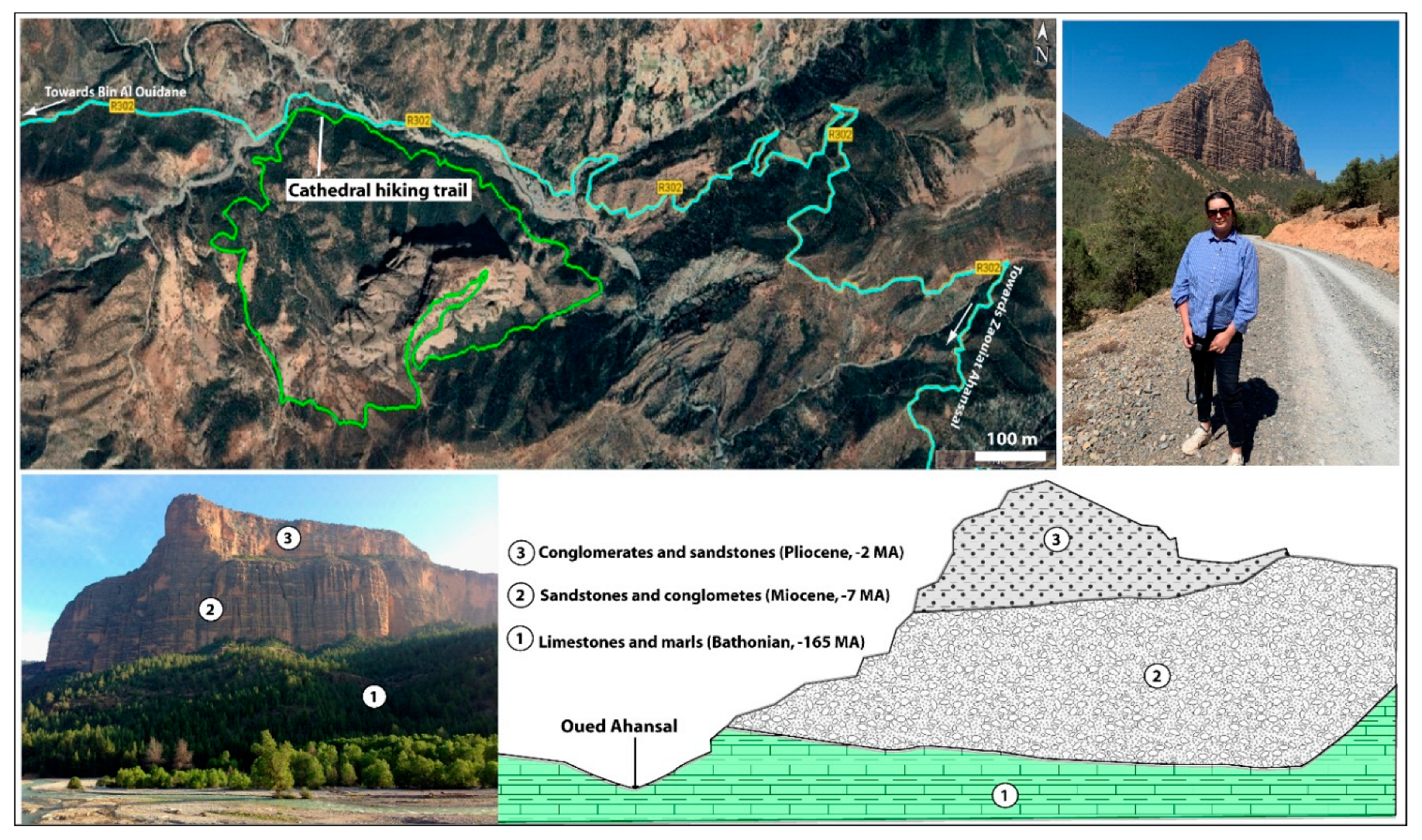

3.1.3. Imsfran Cathedral (X=6°8’55’’; Y=31°59’37’’; Z= 1272 m)

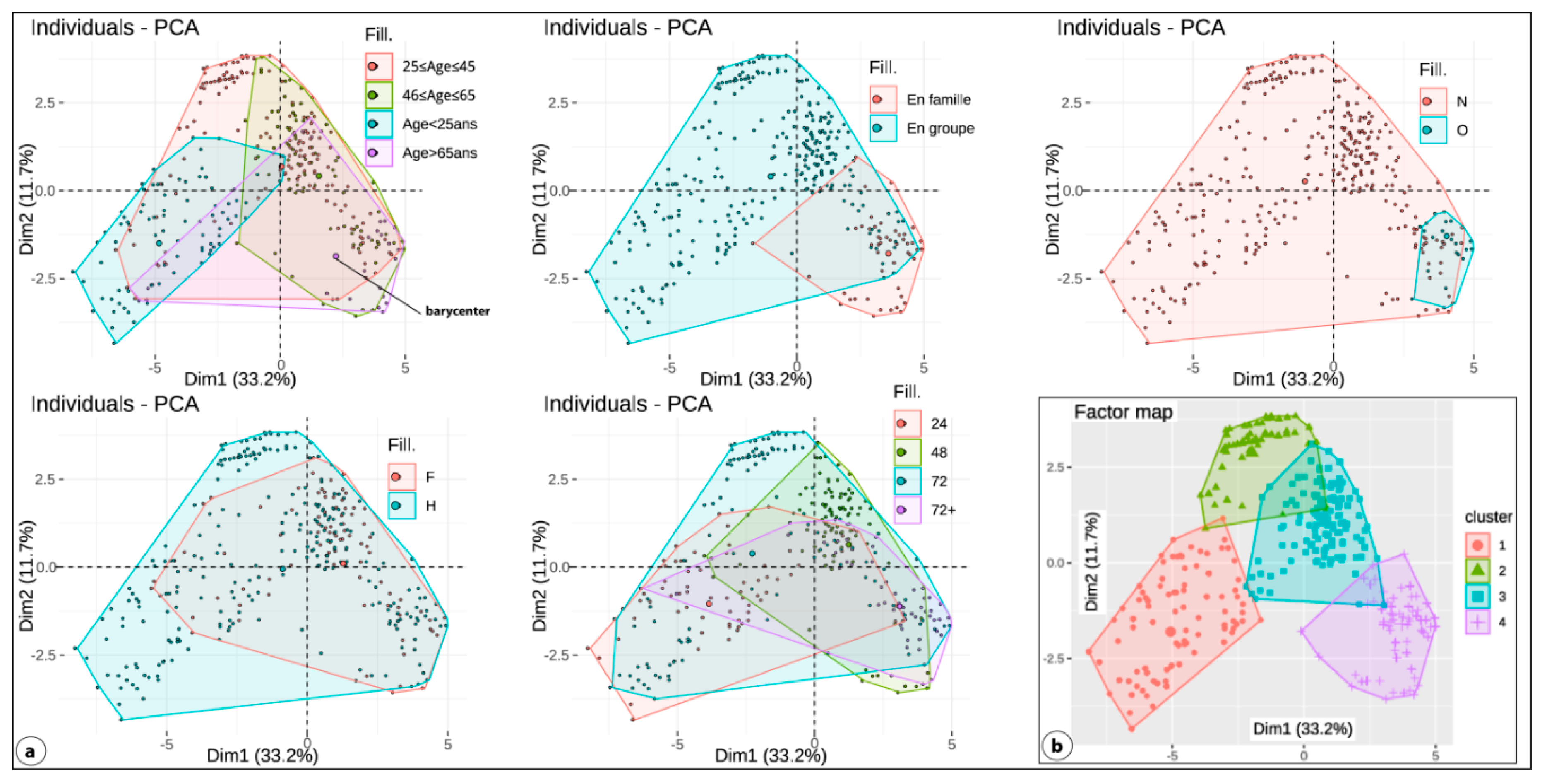

3.2. Quantitative Experiential Analysis of Attraction Criteria

- 1.

- Young sportsmen and women with a passion for the challenge of summit conquest

- 2.

- Families and passive tourists inspired by culture and landscape

- 3.

- Geotourism enthusiasts

- 4.

- Visitors looking for leisure activities

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Husson F., Lê S., Pagès J (2009), Analyse de données avec R. Presses Universitaires de Rennes. Package FactoMineR pour faire des ACP : http://factominer.free.fr/index_fr.html.

- R Development Core Team (2021).,R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. URL https://www.R-project.org/.

- Portal C (2010), Reliefs et patrimoine géomorphologique. Applications aux parcs naturels de la façade atlantique européenne. Thèse en Géographie. Université de Nantes, 2010. Français. ffNNT, 447p.

- OIRY-VARACCA M (2013),From trekking to heritage tourism: identity, a lever for the territorial reconstruction of the AïtBouguemez valley, High Atlas, Morocco. In: Collection EDYTEM. Cahiers de géographie, 14, 2013. 45-56.

- Tomić N.; Božić S (2014), A modified Geosite Assessment Model (M-GAM) and its Application on the Lazar Canyon area (Serbia). Int. J. Environ. Res., 8(4), pp.1041-1052. [CrossRef]

- Trukhachev A (2015), Methodology for Evaluating the Rural Tourism Potentials: A Tool to Ensure Sustainable Development of Rural Settlements. Sustainability 2015, 7, 3052-3070; [CrossRef]

- Slehat M. (2018). Evaluation of Potential Tourism Resources for Developing Different Forms of Tourism: Case Study of Iraq Al-Amir and its surrounding areas – Jordan. Thesis, edit. CatholischeUniversitat, Eichstätt, 2018, 285p.

- Tranquarda M., Riffonb O (2018), Démarche d’attribution du statut international de géoparc : proposition d’une méthodologie d’analyse multicritère pour l’évaluation du potentiel des territoires et l’intégration des objectifs de développement durable. Revue Organisations&Territoires, Volume 27, 1, pp. 1-20. [CrossRef]

- Neto de Carvalho C., Baucon A., Bayet-Goll A., Belo J. (2021). The Penha Garcia Ichnological Park at Naturtejo UNESCO Global Geopark (Portugal): A geotourism destination in the footprint of the Great Ordovician Biodiversification Event. GeoconservationResearch, 4(1):70-79. [CrossRef]

- Billand A. (1996). Développement touristique des parcs de montagne au Maroc : principes de zonage et d'aménagement / Tourismdevelopment in the mountainparks of Morocco : planning and zoning principles. In: Revue de géographie alpine, tome 84, n°4, 1996. pp. 95-108. [CrossRef]

- Cayla N., Duval-Massaloux M. (2013). Le géotourisme : patrimoines, pratiques, acteurs et perspectives marocaines. In: Collection EDYTEM. Cahiers de géographie, 14, 2013. Ressources patrimoniales et alternatives touristiques, entre oasis et montagne. pp. 101-116. [CrossRef]

- Mehdioui S. El Hadi H. ,Tahiri A. , Brilha J. , El Haibi H., Tahiri M (2020),Inventory and Quantitative Assessment of Geosites in Rabat-Tiflet Region (North Western Morocco): Preliminary Study to Evaluate the Potential of the Area to Become a Geopark. Geoheritage (2020) 12:35. [CrossRef]

- Ait Omar T,2021, Les géopatrimoines de la partie Nord-Est du géoparc régional du M’Goun (Moyen et Haut Atlas Central, Maroc) : Inventaire, évaluation et valorisation. Thèse de doctorat, Univ. Sultan Mouly Slimane-Univ. Angers, 500p.

- Elkaichi A., Errami E., Patel N (2021),Quantitative assessment of the geodiversity of M’Goun UNESCO Geopark, Central High Atlas (Morocco). Arabian Journal of Geosciences (2021) 14:2829. [CrossRef]

- Fodness D (1994), Measuring Tourist Motivation, Annals of Tourism Research, A Social Sciences Journal, Vol. 21 (3), pp. 555-581. [CrossRef]

- Oppermann M (1995), Travel life cycle. Annals of Tourism Research, Volume 22, Issue 3, pp. 535-552. [CrossRef]

- Gagnon S (2007), Attractivité touristique et « sens » géo-anthropologique des territoires. Téoros, 26(2), 5–11. [CrossRef]

- Dupeyras A., MacCallum N (2013), Indicators for Measuring Competitiveness in Tourism: A Guidance Document, OECD Tourism Papers, 2013/02, OECD Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Boley B.-B.; Nickerson N.-P. (2013),Profilinggeotravelers: An a priori segmentation identifying and defining. sustainable travelers using the Geotraveler Tendency Scale (GTS). J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 21, 314–330. [CrossRef]

- WallissJ.,Kok K (2014),New interpretative strategies for geotourism: an exploration of two Australian mining sites, Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change, 12:1, 33-49. [CrossRef]

- Ólafsdóttir R., Tverijonaite E (2018),Geotourism: A Systematic Literature Review. Geosciences 8(7):234. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y., Linjie Jiao L., Yu Z., Lin Z., Gan M (2020), A Tourism Route-Planning Approach Based on Comprehensive Attractiveness. IEEE Access. [CrossRef]

- Pearce P.-L., Lee UL (2005),Tourist behavior: Developing the travel career approach to tourist motivation. Journal of Travel Research, Vol. 4, N° 3, p. 226-237. [CrossRef]

- Morgan M., Lugosi P., Ritchie Brent J.-R (2010),The Tourism and Leisure Experience: Consumer and Managerial Perspectives. Annals of Tourism Research 38(3):1205–1206. [CrossRef]

- Chen C. M., Chen S. H., Lee H. T (2011),The destination competitiveness of Kinmen’s tourism industry: exploring the interrelationships between tourist perceptions, service performance, customer satisfaction and sustainable tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 19, 247–264. [CrossRef]

- Duglio S., Bonadonna A., Letey M., PeiraG., Zavattaro L. and Lombardi G (2019),Tourism Development in Inner Mountain Areas—The Local Stakeholders’ Point of View through a Mixed Method Approach. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5997; [CrossRef]

- Cao Q., Sarker M., Zhang D, Sun J., Xiong T., Ding J (2022), Tourism Competitiveness Evaluation: Evidence From Mountain Tourism in China. Front. Psychol. 13:809314. [CrossRef]

- Rid W., Ezeuduji O.-I., Probstl-Haider U (2014), “Segmentation by motivationfor rural tourism activities in The Gambia”, Tourism Management, Vol. 40, pp. 102-116. [CrossRef]

- Le S, Josse J, Husson F (2008), FactoMineR: An R Package for Multivariate Analysis. Journal of Statistical Software, 25(1), 1-18. [CrossRef]

- Kassambara A, Mundt F (2020), Factoextra: Extract and Visualize the Results of Multivariate Data Analyses_. R package version 1.0.7, <https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=factoextra>.

- Strang G (2016), Introduction to Linear Algebra, 5th Edition. Wellesley - Cambridge Press, 2016, ISBN 978-0-9802327-7-6, 574 pages.

- Szekely G., Rizzo M (2005),Hierarchical Clustering via Joint Between-Within Distances: Extending Ward's Minimum Variance Method. Journal of Classification 22, 151–183. [CrossRef]

- Jain A K (2010),Data clustering: 50 years beyond k-means. Pattern Recogn. Lett. 31(8), 651–666.

- Husson F., Josse J., Pagès J (2010),Principal component methods - hierarchical clustering - partitional clustering: why would we need to choose for visualizing data? Technical Report – Agrocampus.Available online: http://www.sthda.com/english/upload/hcpc_husson_josse.pdf (accessed on 03 October 2023).

- Le Marrec A (1985), Carte géologique du Maroc au 1/100.000, feuille deDemnat. Notes et Mémoires du Service Géologique du Maroc, Rabat,338.

- Jenny J (1985), Carte géologique du Maroc au 1 : 100 000, feuille Azilal. Notes Mém. Serv. géol.Maroc , Rabat, n° 339.

- Haddoumi H., Charrière A., Mojon PO (2010), Stratigraphie et sédimentologie des « Couches rouges » continentales du Jurassique- Crétacé du Haut Atlas central (Maroc): implications paléogéographiques et géodynamiques. Geobios 43(4):433–451. [CrossRef]

- Charrière A., Ibouh H. &Haddoumi H. (2011). Circuit C7, Le Haut Atlas central de Beni Mellal à Imilchil. In Michard et al. (Eds.), Nouveaux guides géologiques et miniers du Maroc, vol. 7, Notes Mém. Serv. Géol. Maroc, n° 559, 109-162.

- Guezal J., El Baghdadi M., Barakat A (2013), Les basaltes de l’Atlas de Béni-Mellal (Haut Atlas Central, Maroc): un volcanisme transitionnel intraplaque associé aux stades de l’évolution géodynamique du domaine atlasique. Anuário Instit Geociê 36(2):70–85. [CrossRef]

- Hancock PL, Chalmers RML, Altunel E, Çakir Z (1999), Travitonics: using travertines in active fault studies. Journal of Structural Geology, Volume 21, Issues 8–9, Pages 903-916. [CrossRef]

- Pentecost A (2005), Morphology and Facies. Chap. IV In: Travertine. Springer, Dordrecht. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg. [CrossRef]

- Souhel A (1996), The Mesozoic in the High Atlas of BeniMellal (Morocco): stratigraphy, sedimentology and geodynamic evolution. Doctoral thesis State Sci., Marrakech, Strata, Toulouse, 2, 27, 235 p.

- Nouri J., Dıaz-Martınez I., Perez-Lorente F (2011),Tetradactyl Footprints of an Unknown Affinity Theropod Dinosaur from the Upper Jurassic of Morocco. PLoS ONE 6(12): e26882. [CrossRef]

- Boutakiout M., Hadri M., Nouri J., Diaz-Martinz I. and Perez-LorenteF. (2009),Rastrilladas de icnitasterópodasgigantesdelJurásico Superior (Sinclinal de Iouaridène, Marruecos). Revista Espanola de Paleontologia24(1): 31–46. [CrossRef]

- Bussard J., Martin S., Monbaron M., ReynardE., El Khalki Y (2022),Les paysages géomorphologiques du Haut Atlas central (Maroc) : potentiel éducatif et éléments pour la médiation scientifique. Géomorphologie, 28(3), pp. 173-185. [CrossRef]

- Boutakiout M., Masrour M., Ladel L., DíazMartínez I., Pérez Lorente F (2010),Nuevosyacimientos de icnitasdomerienses en Ibaqalliwn (Alt Bou Guemez, Alto Atlas Central. Marruecos). Geogaceta, vol. 48, pp. 91-94.

- Ibouh H. (1995). Tectonique en décrochement et intrusions magmatiques au Jurassique; tectogenèse polyphasée des rides jurassiques d'Imilchil (Haut Atlas central, Maroc). Thèse de 3ème cycle, Univ. Cadi Ayyad, Marrakech, 225 p.

- Ibouh H. (2004). Du rift avorté au bassin sur décrochement, contrôles tectonique et sédimentaire pendant le Jurassique (Haut Atlas central, Maroc). Thèse d’état Es-Sciences, Univ. Cadi Ayyad, Marrakech, 224p.

- Ibouh H and Chafiki D (2017) ,La tectonique de l’Atlas : âge etmodalités. S. G. F. Géologues 194, 24-28.

- Roch E (1939), Description géologique des montagnes à l'Est de Marrakech. Notes et Mém. Serv. Mines et Carte géol. Maroc, 51, 438 pp., 91 fig., 7 pl. h. t.

- Fabry N., Zeghni.S. (2021).La gestion intelligente des destinations tirée par les émotions et les small data. Journée d’études “ Progression des usages : du tourisme innovant au smart tourisme ”. Axe 1 : Usage du numérique pour réinventer l’expérience touristique, April 2021, Marne-la-Vallée (en ligne), France. ffhal-03186425f.

- Hosany, S., Martin, D., Woodside, AG (2020). Emotions in Tourism: Theoretical Designs, Measurements, Analytics, and Interpretations, Journal of Travel Research, 60(7), pp.1-17. [CrossRef]

- Klonsky E., Victor S., Hibbert A. &Hajcak G (2019), The Multidimensional Emotion Questionnaire (MEQ): Rationale and Initial Psychometric Properties, Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment 41(3):1-16. [CrossRef]

- Bastiaansen M, Straatman S, Driessen E, Mitas O, Stekelenburg J and Wang L, 2016,My destination in your brain: A novel neuromarketing approach for evaluating the effectiveness of destination marketing, Journal od Destination Marketing & Management, vol.7, 76-88. [CrossRef]

- BakhtiyariK,Husain H, 2013, Fuzzy Model on Human Emotions Recognition. 12th WSEAS International Conference on Applications of Computer Engineering (ACE '13) At: Cambridge, MA, USA. Conference Paper, January 2013. [CrossRef]

- Hosany S., Gilbert D. (2010). Measuring Tourists' Emotional Experiences toward Hedonic Holiday Destinations. Journal of Travel Research, 48(2), pp. 513–526. [CrossRef]

- Li S., Cui T., Alam M (2021), Reliabilityanalysis of the internet of thingsusingSpaceFault Network. Alexandria Engineering Journal, Volume 60, Issue 1, February 2021, Pages 1259-1270. [CrossRef]

- Brühlmann F., Petralito S., Aeschbach L. F. , Opwis K. (2020), The quality of data collected online: An investigation of careless responding in a crowdsourced sample. Methods in Psychology, Volume 2, November 2020, 100022. [CrossRef]

- Al-Salom P, Carlin JM, 2017, The problem with online data collection: predicting invalid responding in undergraduate samples. Modern Psychological Studies: Vol. 22 (2). Available at: https://scholar.utc.edu/mps/vol22/iss2/2.

- Ward M. K., Pond SB (2015), Using virtual presence and survey instructions to minimize careless responding on Internet-based surveys. Computers in Human Behavior, 48, 554–568. [CrossRef]

- Barratt M J, Ferris JA, Lenton S, 2015,Hidden Populations, Online Purposive Sampling, and ExternalValidity:Taking off the Blindfold. Field Methods, 27(1), 3–21. [CrossRef]

- Aust F, Diedenhofen B, Ullrich S, Musch J, 2013, Seriousness checks are useful to improve data validity in online research. Behavior Research Methods, 45(2), 527– 535. [CrossRef]

- China Daily (2017),The State Council of China. Guidance on the Promotion of the Development of All-for-One Tourism. Available at: http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/opinion/2017-03/09/content_28486265.htm.

- Calderón-Vargas F.; Asmat-Campos D.; Carretero-Gómez A (2019), Sustainable tourism and renewable energy: Binomial for local development in Cocachimba, Amazonas, Peru. Sustainability, 11(18), 4891. [CrossRef]

| Gender (H, F) | Number | % | Fromabroad (O, N) | Number | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Man | 511 | 66.62 | Morocco | 637 | 83.05 |

| Woman | 256 | 33.38 | Foreign | 130 | 16.95 |

| Age | Number | % | Duration of experience | Number | % |

| Lessthan 25 yearsold | 133 | 17.34 | 24H | 103 | 13.43 |

| Between 25 and 45 yearsold | 349 | 45.50 | 48H | 281 | 36.64 |

| Between 46 and 65 yearsold | 216 | 28.16 | 72H | 236 | 30.76 |

| Over 65 years | 69 | 9.00 | Plus de 72H | 147 | 19.17 |

| Travel type | Number | % | Sites visited among the 13 selected for study | Number | % |

| With the family | 141 | 18.39 | ≤3 | 162 | 21.12 |

| Withfriends | 481 | 62.71 | Entre 4 et 7 | 407 | 53.06 |

| Organized by an agency | 145 | 18.90 | >7 | 198 | 25.82 |

| Factor (Fi) weight, Vexpl. |

Criteria (variable Vij) | Overall rating | Average | Deviation | Internalweight (%) | Overallweight (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Territoryattributes (F1) 36.96 % |

Easy access (V11) | 3393 | 4.42 | 0.77 | 8.38 | 3.10 |

| Accommodation capacity (V12) | 2657 | 3.46 | 1.21 | 6.56 | 2.42 | |

| Access to basic services (V13) | 3584 | 4.67 | 0.62 | 8.85 | 3.27 | |

| Feeling safe and secure (V14) | 3524 | 4.59 | 0.62 | 8.70 | 3.22 | |

| Feeling overcoming the difficulty of walking (V15) | 3266 | 4.26 | 1.10 | 8.06 | 2.98 | |

| Easyhikes (V16) | 1932 | 2.52 | 1.60 | 4.77 | 1.76 | |

| Condition of hiking trails (V17) | 2355 | 3.07 | 0.79 | 5.81 | 2.15 | |

| Enjoy walking in unspoilt countryside (V18) | 3670 | 4.78 | 0.41 | 9.06 | 3.35 | |

| Entertainment and leisure activities (V19) | 3312 | 4.32 | 0.81 | 8.18 | 3.02 | |

| Popularity and visibility of the circuit and sub-circuits on social networks (V110) | 3318 | 4.33 | 1.14 | 8.19 | 3.03 | |

| Length of time required to complete the tours (V111) | 2343 | 3.05 | 1.26 | 5.78 | 2.14 | |

| Enjoying contributing to local economic development (V112) | 3649 | 4.76 | 0.52 | 9.01 | 3.33 | |

| Feeling to promote sustainable rural tourism (V113) | 3502 | 4.57 | 0.70 | 8.65 | 3.20 | |

| Value of landscape resources (F2) 19.16 % |

Beautifulnaturallandscapes (V21) | 3761 | 4.90 | 0.26 | 17.91 | 3.43 |

| Contrast with the environment (V22) | 2565 | 3.34 | 0.79 | 12.22 | 2.34 | |

| Differentviews (V23) | 3671 | 4.79 | 0.41 | 17.48 | 3.35 | |

| Feeling the majesty of the high peaks (V24) | 3704 | 4.83 | 0.46 | 17.64 | 3.38 | |

| Discoveringvirgin nature (V25) | 3734 | 4.87 | 0.34 | 17.78 | 3.41 | |

| Diversity of geomorphological features (V26) | 3562 | 4.64 | 0.53 | 16.96 | 3.25 | |

| Value of geological resources (F3) 13.92 % |

Geological value (V31) | 3149 | 4.11 | 0.80 | 20.64 | 2.87 |

| Variety of the geological landscape (V32) | 3322 | 4.33 | 0.62 | 21.78 | 3.03 | |

| Regional, national and international representation of the Atlas chain (V33) | 2454 | 3.20 | 1.16 | 16.09 | 2.24 | |

| Degree of preservation of the geological sites (V34) | 2843 | 3.71 | 0.72 | 18.64 | 2.59 | |

| To understand the geological history of the mountains (V35) | 3486 | 4.54 | 0.50 | 22.85 | 3.18 | |

| Value of ecological resources (F4) 9.85 % |

Biological value (V41) | 2995 | 3.90 | 0.78 | 27.75 | 2.73 |

| Biodiversity (V42) | 2512 | 3.28 | 0.51 | 23.28 | 2.29 | |

| Typical ecosystem (V43) | 2540 | 3.31 | 0.46 | 23.54 | 2.32 | |

| Degree of biodiversity conservation (V44) | 2745 | 3.58 | 0.49 | 25.44 | 2.50 | |

| Value of culture resources (F5) 20.11 % |

Rich and distinctive cultural heritage of the region (V51) | 3684 | 4.80 | 0.40 | 16.71 | 3.36 |

| Hospitality (V52) | 3768 | 4.91 | 0.28 | 17.09 | 3.44 | |

| Discovering local customs and traditions (V53) | 3573 | 4.66 | 0.48 | 16.21 | 3.26 | |

| Discovering local gastronomy and organic food (V54) | 3668 | 4.78 | 0.41 | 16.64 | 3.35 | |

| Celebrating with the local residents (V55) | 3647 | 4.75 | 0.43 | 16.54 | 3.33 | |

| Feeling the value of living simple (V56) | 3704 | 4.83 | 0.38 | 16.80 | 3.38 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).