1. Introduction

The loss of highly experienced personnel translates into significant replacement costs, making today's high staff turnover a severe issue for organizations and, by extension, Human Resources Management (Reiche, 2008). Because they are seen as essential resources for the company and its human capital sets it apart from competitors, holding onto the finest workers is crucial. According to the "Resource-based view" idea, organizations that can retain their top people will have an advantage over their competitors in a job market that is constantly changing. This is because their human capital will be more complex for competitors to replicate. (Afiouni, 2007; Barney, 1991). According to several authors, the best approach to accomplishing this retention is to give workers the impression that the company values them (Eisenberger et al., 1986) by investing in developing their competencies (Jimenez and Valle, 2013).

This investment in the development of specialized competencies in employees can be seen in the context of Schultz's Human Capital Theory (1961), which views knowledge as a type of capital. When employees see these procedures as highly valuable, they get emotionally invested in the company and put in more effort to meet its goals (Arthur, 1994; Wood and Menezes, 1998). According to Colquitt et al. (2014), it is the outcome of a conversation between the company and the worker in reaction to the proper treatment they receive. In such circumstances, the employee experiences affective commitment to the company or emotional attachment, which decreases their turnover intentions (Meyer et al., 1993).

This study aims to investigate two main questions: First, does affective commitment mediate the relationship between organizational competencies development practices and turnover intentions? If so, how? Secondly, does this relationship change depending on the participant's generation?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Organizational Competence Development Practices

Organizational support methods that employees believe advance their professional development are known as Organizational Competence Development Practices (OCDP) (Campion et al, 1994; Schneider et al., 1996). Employees place a high value on OCDP because it helps them become more competent and knowledgeable in a particular area that improves performance. It also makes them feel more employable; the more highly they value OCDP, the more likely they will stay in their current position (Campion et al., 1994; Schneider et al., 1996).

According to Bitencourt (2005), the elements that stand out in the development of competences can be summarized through the existence of the following factors:

Competencies are associated with the development of concepts, competencies, and attitudes.

They require competencies and translate into mobilizing resources in work practices.

They imply the articulation of resources and serve as a pillar in the search for better performance.

They produce constant questioning and trigger a process of individual learning, in which the greatest responsibility must be attributed to the individual themselves (self-development).

They are transferred and consolidated through relationships with other people (interaction).

"All activities carried out by the organization and the employee to maintain or improve the employee's functional performance, learning, and competences" is a comprehensive definition of OCDP, according to De Vos et al. (2011, p. 440). Therefore, OCDP includes career development programs, efforts to enhance on-the-job learning, and more conventional training formats. Van der Heijden et al. (2009) assert that it is crucial to consider various learning modalities when examining competence development.

2.2. Turnover Intentions

Turnover intentions are understood as employees' desire to leave their current organization within a certain period and start looking for a new place of work (Benson, 2006), considered the best predictor of voluntary turnover (Hom et al., 2017). Despite the existence of authors who question this relationship (Cohen et al., 2016), this is one of the reasons why this construct has been widely studied, especially when one of the current objectives of organizations is to retain the best employees (Long et al., 2012; Park & Shaw, 2013).

2.2.1. Organizational Competence Development Practices and Turnover Intentions

As mentioned earlier, the development of employee competencies has become crucial in organizations, so they must invest in practices aimed at this, with these employees expressing fewer turnover intentions (Kim, 2005). Eisenberger et al. (2001) state that employees normally do not reveal turnover intentions when they believe that the company values them and is working to help them enhance their competencies. Additionally, it was discovered in a study by Martini et al. (2023) that employee competency development had a negative and significant impact on turnover intentions. The first hypothesis is thus formulated:

Hypothesis 1: OCDPs have a negative and significant effect on turnover intentions.

2.3. Affective Commitment

Organizational commitment is a psychological state that binds employees to their organization (Meyer and Allen, 1991). According to Ng (2015), this psychological connection is a stabilizing force that binds employees to organizations. According to the Meyer and Allen (1991) model, organizational commitment comprises three components: affective commitment, calculative commitment, and normative commitment.

Affective commitment is the employee's emotional attachment, identification, and involvement with the organization (Meyer & Allen, 1984). Affective commitment results from an exchange between the organization and the employee (Colquitt et al., 2014), i.e. when the employee feels that they are treated well by the organization, they develop affective feelings towards it, manifesting a high level of affective commitment. According to Kumari and Afroz (2013), employees with high affective commitment have high feelings of belonging to the organization and feel psychologically attached to it.

2.3.1. Organizational Competence Development Practices and Affective Commitment

According to Shore et al. (2006), social exchange connections that foster employee sentiments of commitment are linked to higher levels of organizational investment. They are therefore motivated by this sense of duty to go above and beyond the call of duty to further the organization's interests. Accordingly, OCDP considerably affects employee attitudes and behaviors based on the reciprocity norm (Gouldner, 1960) and the social exchange theory (Blau, 1964). OCDPs can affect workers' perceptions of their professional worth, which may encourage workers to do their jobs in a more upbeat manner (Maurer et al., 2002). According to Moreira et al. (2022), employees see that organizations that prioritize competency development can demonstrate their concern for them, encouraging them to commit more to the organization.

Hypothesis 2: OCDP has a positive and significant effect on affective commitment.

2.3.2. Affective Commitment and Turnover intentions

Nowadays, most organizations find it difficult to retain their best employees. From the perspective of Luturlean and Prasetio (2019), an employee stays with the organization due to the affective commitment they develop towards it. The components of organizational commitment, especially affective commitment, are negatively associated with behaviors that are detrimental to the organization and positively associated with behaviors that are favorable to the organization.

Among the consequences of affective commitment is a reduction in turnover intentions to leave the organization, since if the employee feels emotionally attached to the organization, they will feel that they should remain there, leading to a reduction in their turnover intentions as well as unjustified absences from work (Meyer et al., 2002). Meyer and Allen (1991) state the great interest in studying affective commitment is because it is considered the best reducer of turnover intentions. In a study by Nguyen et al. (2020), the authors also confirmed that affective commitment is the best reducer of intentions to leave. This is the reasoning that leads us to formulate the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3: Affective commitment negatively and significantly affects turnover intentions.

2.4. Mediating effect of Affective Commitment

Recent empirical research has revealed a retention path between employee development and turnover intention, mainly due to increased employees' affective commitment towards their employer (Koster et al., 2011; Lee & Bruvold, 2003; Rodrigues et al., 2019).

Lee and Bruvold (2003) reported that affective commitment mediates the relationship between OCDP and turnover intentions, and more recent studies have reached similar conclusions (Koster et al., 2011; Nguyen et al., 2020; Rodrigues et al., 2019). The common conclusion of previous studies is that when an organization takes care of its employees by investing in their development, employees reciprocate through more significant commitment and decreased intentions to leave. More specifically, OCDPs increase affective commitment, reducing turnover intentions.

This is the reasoning that leads us to deduce that affective commitment is the mechanism that explains the relationship between OCDP and turnover intentions, thus formulating the hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4: Affective commitment has a mediating effect on the relationship between OCDPs and turnover intentions.

2.5. Generations

Organizations, HR specialists, and researchers have recently shown a growing interest in studying generational disparities. According to Saba (2013), there are three reasons for this interest:

The employees from different generations work together for extended periods due to rising retirement ages.

They are said to have incompatible values and expectations regarding their jobs.

There are no practices tailored to the needs of each generation.

The needs for skill development and the values attached to these practices may vary throughout generations if they have different expectations and attitudes regarding the nature of employment.

This study will consider three generations: the baby boomers, generation X and generation Y (or Millennials).

Born between 1946 and 1964, baby boomers are known for being workaholics who believe in hard work and sacrifice themselves for success (Santos et al., 2011); they respect hierarchy and authority (Gursoy et al., 2008); they value face-to-face communication, getting up and going to another colleague to deal with work-related issues (Eisner, 2005); they feel loyal to the organization (The Ken Blanchard Companies, 2009); and they value seniority in the organization (Gursoy et al., 2008).

Born between 1965 and 1981, generation X is characterized by the following: they value professional success while keeping their family in mind (Santos et al., 2011); they are more cooperative (Cogin, 2012); they enjoy working in teams; they are flexible and entrepreneurial; they enjoy feedback and short-term rewards (Tulgan, 2004); they believe that developing one's skills is the best way to ensure one's job and career security (Reisenwitz and Fowler, 2019); they believe that developing one's skills is the best way to ensure job and career security (Eisner, 2005); and they are more devoted to their profession than to their employer.

Last but not least, the primary traits of Generation Y, defined as those born between 1982 and 2000, are as follows: they are less autonomous and require more supervision (The Ken Blanchard Companies, 2009), presumably because their parents tried to monitor everything their kids did, socially, academically, and even at work (Glass, 2007); they question authority (Veloso et al., 2011); they are the most knowledgeable about new technologies (Cogin, 2012; Santos et al., 2011); they enjoy daily feedback and seek out new challenges that push them to the limit (Lancaster & Stillman, 2002); they value the development of competences for career progression (Deloitte, 2011); they don't value job stability (Martin, 2005); and what keeps them engaged and enthusiastic is the meaning and value of their work (Morrison et al., 2006).

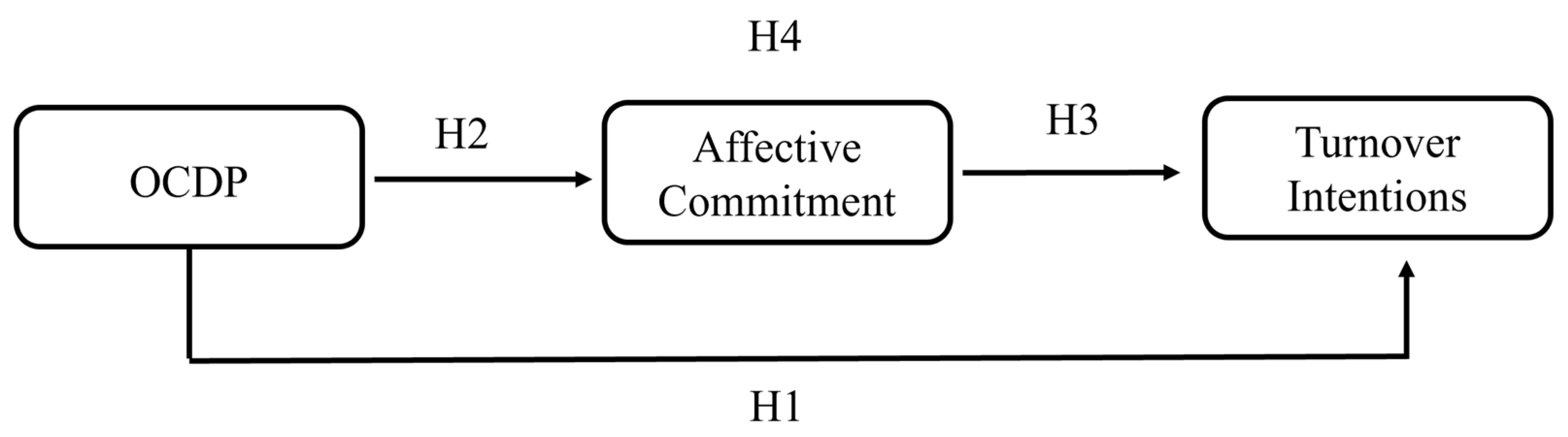

The model shown in

Figure 1 summarizes the hypotheses formulated in this study.

3. Method

3.1. Data Collection Procedure

A total of 2134 participants took part in this study on a voluntary basis. However, only 2123 were considered since 11 of the participants needed to meet the essential condition for taking part in this study, which was to have been working for at least six months in organizations located in Portugal. The sampling process was non-probabilistic, convenient, and intentional snowball sampling (Trochim, 2000).

The questionnaire, which was posted online on the Google Docs platform, contained information about the purpose of the study. It was also stated that the confidentiality of the answers would be guaranteed. After reading the informed consent form, the participants had to answer a question about their willingness to take part in the study. If they did not agree to take part in the study, they were referred to the end of the questionnaire. The questionnaire comprised seven questions to characterize the sample (age, gender, educational qualifications, seniority in the organization, seniority in the position, type of employment contract and sector of work) and three scales (organizational practices for developing competencies, affective commitment, and turnover intentions). The data was collected between 2019 and 2021.

3.2. Participants

As far as gender is concerned, the number of female and male participants is almost identical (

Table 1). However, about the generation to which the participant belongs, they mainly belong to Generation Y (

Table 1). Regarding academic qualifications, the highest percentage of participants had a degree (Table). Most participants have a permanent contract, have been with the organization for 5 years or less and work in the private sector (

Table 1).

3.3. Data Analysis Procedure

The initial step was importing the data into the IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA SPSS Statistics 29 program. Initially, each instrument's validity was examined. Since the turnover intentions instrument only has three questions, an exploratory factor analysis was done. After calculation, the KMO value was determined to be more than 0.70 (Sharma, 1996). Additionally, we computed the average extracted variance, which ought to exceed 50%. Every item with a factor weight higher than 0.50 was considered when calculating each item's factor weights. Using AMOS Graphics for Windows 29 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), confirmatory factor analysis was used to assess the validity of the remaining two instruments. A "model generation" logic was followed in the process (Jöreskog & Sörbom, 1993). By the established guidelines (Hu & Bentler, 1999), the following six fit indices were combined: Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), Root Mean Square Residual (RMSR), Goodness-of-fit Index (GFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), Chi-square ratio/degrees of freedom (χ²/gl), and Comparative Fit Index (CFI). It is acceptable if the chi-square/degrees of freedom ratio (χ²/gl) are less than 5. A good fit is indicated by values above 0.90 for the CFI, GFI, and TLI, and an adequate fit is indicated by values above 0.80. A good match is indicated by RMSEA values less than 0.08 (McCallum et al., 1996). The fit is better when the RMSR is lower (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Next, we examined the construct dependability for every dimension on the scale, where a value greater than 0.70 is expected. The average variance extracted (AVE), which should be more than 0.50, was used to test for convergent validity (Fornell and Larcker, 1981). However, AVE values larger than 0.40 are acceptable, suggesting good convergent validity when Cronbach's alpha value is greater than 0.70 (Hair et al., 2011). The square root of the AVE's value must be higher than the factor's correlation value for discriminant validity to be present (Anderson and Gerbin, 1988; Fornell and Larcker, 1981).

By calculating Cronbach's alpha, which needs to be greater than 0.70, the internal consistency of each instrument was evaluated (Bryman and Cramer, 2003).

Lastly, each participant took part in a test to see how sensitive the items were. All response points on the items must have an answer, the median cannot be near one of the extremes, and the absolute kurtosis and skewness values cannot be greater than 2 or 7, respectively (Finney and DiStefano, 2013). To perform descriptive statistics on the variables under study and to test whether the participants' answers differed significantly from the scale's central point, the parametric one-sample Student's t-test was used. The effect of generations on the variables under study was tested using the One-Way ANOVA parametric test after checking the respective assumptions. The association between the variables under study was tested using Pearson's correlations. The hypotheses formulated in this study were tested through Path Analysis in AMOS Graphics for Windows 29 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA. To test hypothesis 4, as it presupposes a mediating effect, the procedures proposed by Baron and Kenny (1986) were followed.

3.4. Instruments

We employed the De Vos et al. (2011) tool, translated into Portuguese by Moreira and Cesário (2022), to assess organizational competence development practices. Twelve items make up this measure, which is rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 being "Never" to 5 being "Always"). These 12 items fall under three dimensions: training, individualized support, and functional rotation. The confirmatory factor analysis was used to assess their validity. The obtained adjustment indices (\²/gl = 3.75; GFI = 0.99; CFI = 0.99; TLI = 0.99; RMSEA = 0.036; SRMR = 0.029) were deemed sufficient. Nevertheless, items 1 and 6 had to be eliminated because of their low factor weight. Training scored 0.93, individualized support scored 0.72, and functional rotation scored 0.78 regarding construct reliability—values above 0.70 (Bryman and Cramer, 2003). Training and functional rotation have respective Ave values of 0.74 and 0.64, indicating strong convergent validity. Individualized support is the only one with an AVE value of 0.47 (below 0.50), although convergent validity is still considered adequate because it has a Cronbach's alpha value over 0.70 (Hair et al., 2011). Regarding internal consistency, all dimensions exhibit Cronbach's alpha values greater than 0.70, including training at 0.88, individualized support at 0.71, and functional rotation at 0.78.

The corresponding subscale of Meyer and Allen's (1997) organizational commitment instrument, which consists of six items rated on a seven-point Likert scale (ranging from 1 for "Strongly Disagree" to 7 for "Strongly Agree"), was utilized to measure affective commitment. Additionally satisfactory are the fit indices found in the confirmatory factor analysis (TMI =.99; RMSEA =.028; χ²/gl = 2.62; GFI =.99; CFI =.99; TLI =.99). This subscale has a construct reliability of 0.88 and convergent validity with an AVE of 0.56. A Cronbach's alpha value of 0.89 was found for internal consistency.

The three items that comprise the instrument created by Bozeman & Perrewé (2001) were used to test turnover intentions, and the results were rated on a 5-point scale (1 being "Strongly Disagree" to 5 being "Strongly Agree"). An exploratory factor analysis was performed since there are only three items in this instrument. The results showed a KMO of 0.68 and an explained variance of 68.52%. Additionally, the results of Bartlett's test of sphericity were significant at p < 0.001, suggesting that the data originated from a multivariate population that is normally distributed (Pestana & Gageiro, 2003). Its Cronbach's alpha value for internal consistency is 0.77. Additionally, it was discovered that none of the components of the three instruments seriously deviated from normality.

The generations were categorized by Twenge's (2010) guidelines. After providing their birth year, participants were divided into three groups: baby boomers (1946–1964), generation X (1965–1981), and generation Y (1982–2000).

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics of the Variables under Study

Initially, we tried to understand the position of the answers given by the participants in the variables under study. The results show that the participants in this study have a perception of organizational skills development practices that are significantly below the central point of the scale (3) (

Table 2). They revealed high turnover intentions, significantly above the scale's central point (3) (

Table 2). They also revealed themselves to be affectively committed to the organization where they work, since the results obtained are significantly above the central point of the scale (4) (

Table 2).

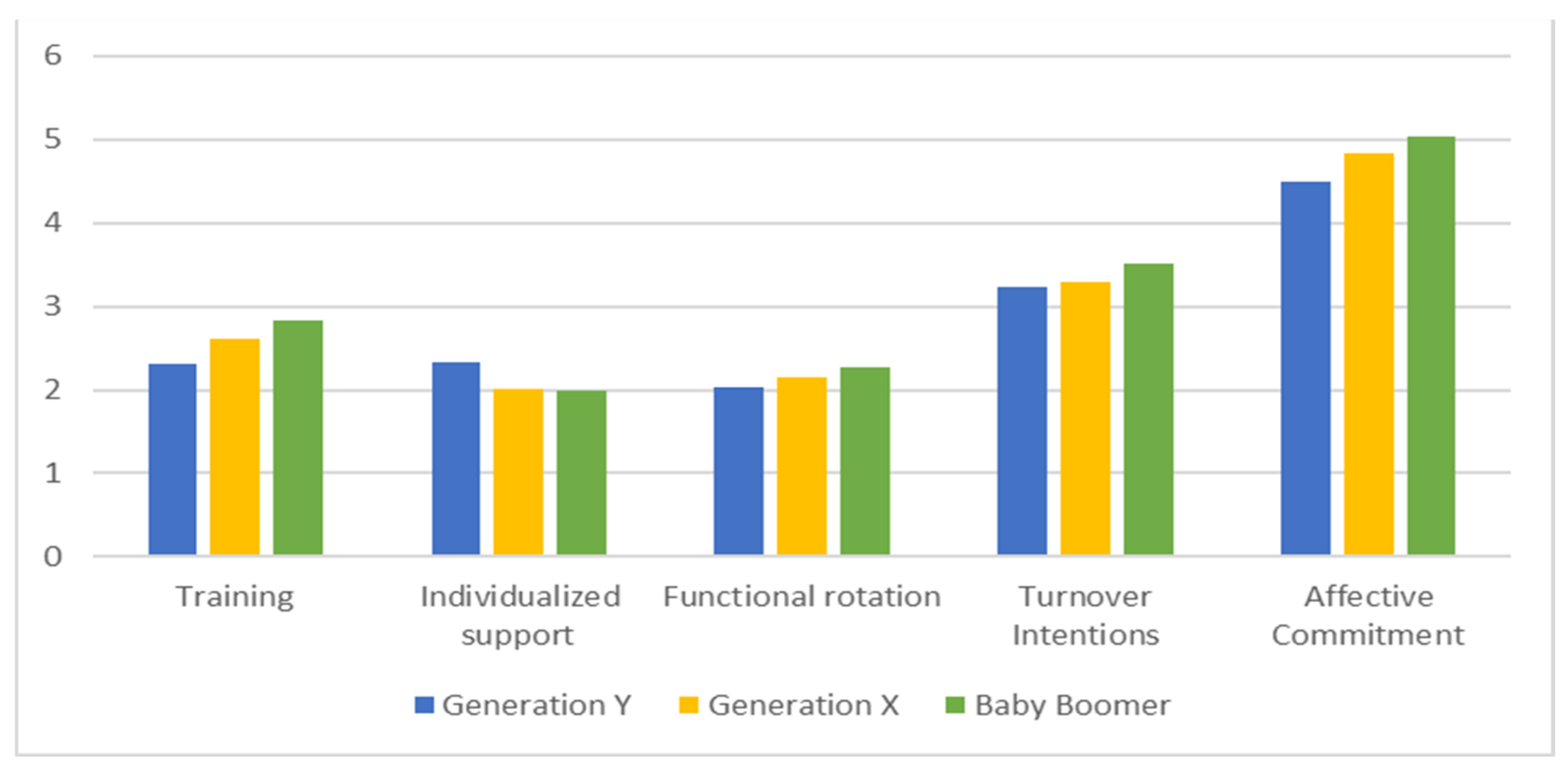

We then tested whether the generations significantly affected the variables under study. The various One-Way ANOVA tests suggested that there were statistically significant differences for training (F (2, 2120) = 30.40; p < 0.001), individualized support (F (2, 2120) = 26.30 p < 0.001), functional rotation (F (2, 2120) = 4.25; p = 0.014 and affective commitment (F (2, 2120) = 14.70; p < 0.001). No statistically significant differences existed for turnover intentions (F (2, 2120) = 3.61; p = 0.081).

Participants from the Baby Boomer generation showed a higher perception of training and functional rotation, and a higher affective commitment than participants from other generations (

Figure 2). As far as individualized support is concerned, Generation Y participants have the highest perception (

Figure 2).

4.2. Association between Variables

Pearson's correlations show that training, individualized support, functional rotation and affective commitment are negatively and significantly associated with turnover intentions (

Table 3). Training, individualized support and functional rotation are positively and significantly associated with affective commitment (

Table 3).

4.3. Hypothesis

4.3.1. Hypothesis 1

The results show that training, individualized support, and functional rotation negatively and significantly affect turnover intentions (

Table 4). The model explains 12% of the variability in turnover intentions (

Table 4).

Next, the effect of organizational competencies development practices on turnover intentions was tested, separating the participants by generation. For Generation Y, training, individualized support, and functional rotation negatively and significantly affect turnover intentions (

Table 5). The model explains 13% of the variability in turnover intentions (

Table 5).

For Generation X, training, individualized support, and functional rotation negatively and significantly affect turnover intentions (

Table 5). The model explains 11% of the variability in turnover intentions (

Table 5).

For the baby boomer generation, only individualized support negatively and significantly affects turnover intentions (

Table 5). The model explains 38% of the variability in turnover intentions (

Table 5).

Hypothesis 1 was supported.

4.3.2. Hypothesis 2

The results show that training, individualized support, and functional rotation positively and significantly affect affective commitment (

Table 6). The model explains 24% of the variability in affective commitment (

Table 6).

Next, the effect of organizational competencies development practices on affective commitment was tested, separating the participants by generation. For Generation Y, training, individualized support, and functional rotation positively and significantly affect affective commitment (

Table 7). The model explains 25% of the variability in affective commitment (

Table 7).

For Generation X, training, individualized support, and functional rotation positively and significantly affect affective commitment (

Table 7). The model explains 22% of the variability in affective commitment (

Table 7).

For the baby boomer generation, only individualized support negatively and significantly affects affective commitment (

Table 7). The model explains 25% of the variability in affective commitment (

Table 7).

Hypothesis 2 was supported.

4.3.3. Hypothesis 3

The results show that affective commitment negatively and significantly affect turnover intentions (

Table 8). The model explains 26% of the variability in turnover intentions (

Table 8).

Next, the effect of affective commitment on turnover intentions was tested, separating the participants by generation. For Generation Y, affective commitment negatively and significantly affects turnover intentions (

Table 9). The model explains 1273% of the variability in turnover intentions (

Table 9).

For Generation X, affective commitment negatively and significantly affects turnover intentions (

Table 9). The model explains 27% of the variability in turnover intentions (

Table 9).

For the baby boomer generation, affective commitment negatively and significantly affects turnover intentions (

Table 9). The model explains 26% of the variability in turnover intentions (

Table 9).

Hypothesis 3 was supported.

4.3.4. Hypothesis 4

According to Baron and Kenny (1986), the assumptions for testing the mediating effect were tested in hypotheses 1, 2 and 3.

The results show a total mediating effect of affective commitment in the relationship between training and turnover intentions and between functional rotation and turnover intentions since training and functional rotation no longer significantly affect turnover intentions (

Table 10).

As for the mediating effect of affective commitment on the relationship between individualized support and turnover intentions, there was a partial mediation effect since the effect of individualized support on turnover intentions continued to be significant but decreased in intensity (β

1 = -0.24; β

2 = -0.14) (

Table 4 and

Table 10).

The model explains 26% of the variability in turnover intentions. There was an increase in variability of 14%.

The mediating effect was then tested according to the generation to which the participant belonged.

For Generation Y, the results show a total mediating effect of affective commitment in the relationship between training and turnover intentions and between functional rotation and turnover intentions since training and functional rotation no longer significantly affect turnover intentions (

Table 11). As for the mediating effect of affective commitment on the relationship between individualized support and turnover intentions, there was a partial mediation effect since the effect of individualized support on turnover intentions continued to be significant but decreased in intensity (β

1 = -0.23; β

2 = -0.10) (

Table 4 and

Table 11). The model explains 28% of the variability in turnover intentions. There was an increase in variability of 15%.

For Generation X, the results show a total mediating effect of affective commitment in the relationship between training and turnover intentions and between functional rotation and turnover intentions since training and functional rotation no longer significantly affect turnover intentions (

Table 11). As for the mediating effect of affective commitment on the relationship between individualized support and turnover intentions, there was a partial mediation effect since the effect of individualized support on turnover intentions continued to be significant but decreased in intensity (β

1 = -0.18; β

2 = -0.09) (

Table 4 and

Table 11). The model explains 28% of the variability in turnover intentions. There was an increase in variability of 17%.

For Generation Baby Boomer, the results show a partial mediation effect since the effect of individualized support on turnover intentions continued to be significant but decreased in intensity (β

1 = -0.62; β

2 = -0.51) (

Table 4 and

Table 11). The model explains 41% of the variability in turnover intentions. There was an increase in variability of 16%.

Hypothesis 4 was supported

5. Discussion

This study aimed to study the effect of organizational skills development practices (training, individualized support, and functional rotation) and whether this relationship was mediated by affective commitment. Another objective was to test whether these relationships changed depending on the generation to which the participant belonged.

Hypothesis 1 was confirmed since training, individualized support, and functional rotation negatively and significantly affect turnover intentions. These results align with the literature, which states that developing employees' competences reduces their turnover intention (Martini et al., 2023). However, when it was tested whether these relationships varied according to the generation to which the participant belongs, it was found that for Generation Y and Generation X, the results remained the same. However, this was different for the baby boomer generation, where only individualized support negatively and significantly affected turnover intentions.

As expected, hypothesis 2 was confirmed since the results indicate that training, individualized support, and functional rotation positively and significantly affect affective commitment. These results are also in line with the literature since Nguyen et al. (2020) state that when an organization is concerned with developing the competences of its employees, they feel emotionally attached to it. Once again, for generations Y and X, the results remain the same. However, for the baby boomer generation, only individualized support positively and significantly affects affective commitment.

Hypothesis 3, which assumed a negative and significant effect of affective commitment on turnover intentions, was also confirmed. These results also corroborate what the literature tells us: affective commitment has a negative and significant effect on turnover intentions since employees stay with the organization when they feel affectively committed to it (Luturlean and Prasetio, 2019; Meyer and Allen, 1991). This result holds for participants from all three Generations.

Once again, among the variables under study, the one that proved to be the best reducer of intentions to leave was affective commitment, in line with the results obtained in previous studies (Moreira et al., 2022; Martins et al., 2023).

Finally, a total mediation effect of affective commitment was confirmed in the relationship between training and turnover intentions and between functional rotation and turnover intentions. Only a partial mediation effect was confirmed in the relationship between individualized support and turnover intentions. These results confirm what the literature tells us: that affective commitment mediates the relationship between OCDP and turnover intentions (Koster et al., 2011; Nguyen et al., 2020; Rodrigues et al., 2019). When an organization takes care of its employees by investing in their development, employees reciprocate through more significant commitment and decreased turnover intentions.

When the descriptive statistics of the variables under study were carried out, it was found that the participants in this study had a low perception of the existence of OCDP in their organization. Training is perceived as the most frequent, and functional rotation is perceived as the least frequent. According to Whitney (2001), these practices often exist but are not perceived by employees as the organization would like. The participants who perceived training and functional rotation as most frequent were those from the baby boomer generation. As for individualized support, the Generation Y participants perceived it most frequently. These results are natural since the items in this dimension refer to support for career progression. Generation Y values developing skills for career progression (Deloitte, 2011) and looking for quick leadership programs (Glass, 2007). Turnover intentions are significantly above the mid-point of the scale, and the baby boomer participants have shown the highest turnover intentions. These results go against what was expected since, according to the literature, generation Y does not value job stability, jumping from project to project, position to position, department to department, or organization to organization (Martin, 2005). About affective commitment, the participants in this study showed high levels of affective commitment, with the baby boomer generation showing the highest levels.

5.1. Limitations

The main limitations were the procedures employed for collecting the data and the fact that the questionnaires were self-reporting tools with closed-ended questions and required responses, which may have influenced the participants' responses.

Another limitation is the small number of participants from the baby boomer generation compared to the other generations.

Lastly, because the study was cross-sectional, it was unable to determine a causal association between the factors. It would take a long-term investigation to investigate causal linkages. Several methodological and statistical guidelines were followed to lessen the impact of common method variance (Podsakoff et al., 2003).

5.2. Practical Implications

According to Saba (2013), one of the reasons it has become so important to investigate the generational effect is that this study demonstrates how various generations also view and value the competencies development strategies that organizations support.

This study also shows that, although employees do not view competencies development activities as the organization would like them to be, there is still a need for organizations to invest more in them and make them visible to staff (Whitener, 2001). Human resources management uses these techniques frequently. Employees do not, however, view them as they would like, maybe due to their lack of clarity and the fact that they are not given the credit they merit for improving their abilities.

One of its strongest points is this study's indication of the existence of an affective organizational commitment mediation influence on the relationship between OCDP and turnover intentions. Organizations must use specific competencies development practices appropriate for their workforce to retain their best employees. This is because these employees are difficult to replace and, according to the "Resource-Based View" theory (Afiouni, 2007; Barney, 1991), they become a competitive advantage in today's labor market.

5. Conclusions

At a time when one of the biggest problems facing organizations is high employee turnover (Reiche, 2008; Martins et al., 2023), this study has confirmed that if an organization wants to retain its best employees, it must invest in developing their skills in order to boost their emotional commitment and reduce their intentions to leave (Koster et al., 2011; Nguyen et al., 2020; Rodrigues et al., 2019).

Another indication from this study is that organizations should consider the generation to which the employee belongs, especially regarding competences development, as interests and needs vary from generation to generation (Kapoor and Solomon, 2011).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A. M., C. T., and A. A.; methodology, A. M.; software, A. M.; validation, A. M., C. T. and A. A.; formal analysis, A. M.; investigation, A. M.; resources, A. M.; data curation, A. M.; writing—original draft preparation, A. M. and C. T..; writing—review and editing, A. M., C. T. and A. A..; visualization, A, M.; supervision, A. M.; project administration, A. M.; funding acquisition, A. M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, as all participants (before answering the questionnaire) needed to read the informed consent. After reading the informed consent, they had to answer a question as to whether they agreed to answer the questionnaire. Only if they agreed could they complete the questionnaire. If they disagreed, they could not do so. The participants were informed about the study's purpose and the confidentiality of the results since the individual results would never be known and would only be analyzed as a whole.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available because in their informed consent, participants were informed that the data were confidential and that individual responses would never be known, as data analysis would be of all participants combined.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Afiouni, Fida. Human Resource Management and Knowledge Management: A Road Map Toward Improving Organizational Performance. Journal of American Academy of Business, Cambridge 2007, 11, 124–130.

- Anderson, James C. , and David W. Gerbing. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur, Jeffrey B. Effects of human resource systems on manufacturing performance and turnover. Academy of Management Journal 1994, 37, 670–687. [Google Scholar]

- Barney, Jay B. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar]

- Baron, Reuben M. , and David A. Kenny. The Moderator-Mediator Variable Distinction in Social Psychological Research: Conceptual, Strategic, and Statistical Considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, George S. Employee development, commitment and intention to turnover: A test of “employability” policies in action. Human Resource Management Journal 2006, 16, 173–192. [Google Scholar]

- Bitencourt, Cláudia C. Competência gerencial e aprendizagem nas organizações, 2005.

- Blau, Peter M. Exchange and Power in Social Life, 1964.

- Bozeman, Dennis P. , and Pamela Perrewé. The effect of item content overlap on organizational commitment questionnaire—Turnover cognitions relationships. Journal of Applied Psychology 2001, 86, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryman, Alan, and Duncan Cramer. Análise de dados em ciências sociais. Introdução às técnicas utilizando o SPSS para windows, 2003.

- Campion, M. ichael A., Ellen M. Papper, and Gina J. Medsker. Relations between work team characteristics and effectiveness: A replication and extension. Personnel Psychology 1996, 49, 429–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cogin, Julie. Are generational diferences in work values fact or fiction? Multi-country evidence and implications. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 2012, 23, 2268–2294. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Galia, Robert S. Blake, and Doug Goodman. Does turnover intention matter? Evaluating the usefulness of turnover intention rate as a predictor of actual turnover rate. Rev. Pub. Person. Adm. 2016, 36, 240–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colquitt, Jason A., Michael D. Baer, David M. Long, and Marie D. K. Halvorsen-Ganepola. Scale indicators of social exchange relationships: A comparison of relative content validity. Journal of Applied Psychology 2014, 99, 599–618. [CrossRef]

- De Vos, Ans, Sara De Hauw, and Beatrice I. J.M. Van der Heijden. Competency development and career success: The mediating role of employability. Journal of Vocational Behavior 2011, 79, 438–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deloitte. Talent edge 2020: Building the recovery together—what talent expects and how leaders are responding. 2011. https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/insights/topics/talent/talent-edge-2020-building-the-recovery-together.html (accessed ). 5 December.

- Eisenberger, Robert, Robin Huntington, Steven Hutchison, and Debora Sowa. Perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology 1986, 71, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, Robert, Armeli, S., Rexwinkel, B., Patrick D. Lynch, and Linda Rhodes. Reciprocation of perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology 2001, 86, 42–51.

- Eisner, Susan P. Managing Generation Y. SAM Advanced Management Journal 2005, 70, 4–12.

- Finney, Sara J. , Sara J., and Cristine DiStefano. Nonnormal and categorical data in structural equation modeling. In Structural Equation Modeling: A Second Course; Hancock, G.R., Mueller, R.O., Eds.; IAP Information Age Publishing: Charlotte, NC, USA, 2013; pp. 439–492. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, Claes, and David F. Larcker. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glass, Amy. Understanding generational differences for competitive success. Industrial and Commercial Training 2007, 39, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouldner, Alvin W. The norm of reciprocity: A preliminary statement. American Sociological Review 1960, 25, 161–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, Dogan, Thomas A. Maier, T., and Christina G. Chi. Generational differences: An examination of work values and generational gaps in the hospitality workforce. 2008, 27, 448–458. International Journal of Hospitality Management 2008, 27, 448–458.

- Hair, Joseph, Christian Ringle, and Marko Sarstedt. PLS-SEM: Indeed a Silver Bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice 2011, 19, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hom, Peter W. , Thomas Lee, Jason D. Shaw, John P. Hausknecht. One hundred years of employee turnover theory and research. J. Appl. Psychol. 2017, 102, 530.

- Hu, Li-tze, and Peter M. Bentler. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez-Jimenez, Daniel and Sanz-Valle, R. Studying the Effect of HRM Practices on the Knowledge Management Process. Personnel Review 2013, 42, 28–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jöreskog, Karl G., and Dag Sörbom. LISREL8: Structural Equation Modelling with the SIMPLIS Command Language. 1993.

- Kapoor, Camille, Nicole and Solomon, N. "Understanding and managing generational differences in the workplace", Worldwide Hospitality and Tourism Themes 2011, 3, 308–318. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Soonhee. Factors affecting state government information technology employee turnover intentions. American Review of Public Administration 2005, 35, 137–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koster Ernst, H. , Evi De Lissnyder, Nazarin Derakshan, Rudi De Raedt. Understanding depressive rumination from a cognitive science perspective: The impaired disengagement hypothesis. Clin Psychol Rev 2011, 31, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, Neha, and Nishat Afroz. “The Impact of Affective Commitment in Employees Life Satisfaction”. Global Journal of Management and Business Research 2013, 13, 25–30. Available online: https://journalofbusiness.org/index.php/GJMBR/article/view/100435.

- Lancaster, Lynne C., and David Stillman. When Generations Collide, 2002; Harper Collins: New York.

- Lee, Chay Hoon, and Norman T. Bruvold. Creating value for employees: Investment in employee development. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 2003, 14, 981–1000. [CrossRef]

- Long, Choi Sang, Panniruky Perumal, and Musibau Akintunde Ajagbe. The impact of human resource management practices on employees’ turnover intention: A conceptual model. Interdisciplinary Journal of Contemporary Research in Business 2012, 4, 629–641. [Google Scholar]

- Luturlean, Bachruddin Saleh, and Arif Partono Prasetio. Antecedents of employee’s affective commitment the direct effect of work stress and the mediation of job satisfaction. Journal of Applied Management 2019, 17, 697–712. [CrossRef]

- Martin, Carolyn A. From High Maintenance to High Productivity: What Managers Need to Know About Generation Y. Industrial and Commercial Training 2005, 37, 39–44. [CrossRef]

- Martini, Mattia, Tiziano Gerosa, and Dario Cavenago. How does employee development affect turnover intention? Exploring alternative relationships. International Journal of Training and Development 2023, 27, 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, Patrícia, Generosa Nascimento, G. , and Ana Moreira. Leadership and Turnover Intentions in a Public Hospital: The Mediating Effect of Organisational Commitment and Moderating Effect by Activity Department. Administrative Sciences 2023, 13, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurer, Todd J., Heather R. Pierce, and Lynn M. Shore. Perceived beneficiary of employee development activity: A three-dimensional social exchange model. Academy of Management Review 2002, 27, 432–444. [CrossRef]

- McCallum, Robert, Michael Browne, and Hazuki Sugawara. Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structural modelling. Psychol. Methods 1996, 1, 130–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, John P., and Nathalie J. Allen. Testing the “side-bet theory” of organizational commitment: Some methodological considerations. Journal of Applied Psychology 1984, 69, 372–378. [CrossRef]

- Meyer, John P., and Nathalie J. Allen. A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Human Resource Management Review 1991, 1, 61–89. [CrossRef]

- Meyer, John P., and Nathalie J. Allen. Commitment in the workplace: Theory, research, and application, S: CA, 1997.

- Meyer, John P., and Nathalie J. Allen, and cCathetine A. Smith. Commitment to organizations and occupations: Extension and test of a three-component conceptualization. Journal of Applied Psychology 1993, 78, 538–551. [CrossRef]

- Meyer, John P. , David J. Stanley, Lynne Herscovitch, and Laryssa Topolnytsky. Affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization: A meta-analysis of antecedents, correlates, and consequences. Journal of Vocational Behavior 2002, 61, 20–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, Ana, and Francisco Cesário. Organizational Practices of Competencies Development: Adaptation and Validation of an Instrument. Academia Letters 2022, 5232. [CrossRef]

- Moreira, Ana, Maria José Sousa, and Francisco Cesário. Competencies development: The role of organizational commitment and the perception of employability. Social Sciences 2022, 11, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, Robert, Tamara Erickson, and Ken Dychtwald. Managing middlescence. Harvard Business Review 2006, 84, 79–86. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, Thomas W. H. The incremental validity of organizational commitment, organizational trust, and organizational identification. Journal of Vocational Behavior 2015, 88, 154–163.

- Nguyen, Hoa Dinh, Diem My Thi Tran, Thanh Ba Vu, and Phuong Thuy Thi Le.An Empirical Study of Affective Commitment: The Case of Machinery Enterprises in Hochiminh City. Organizations and Markets in Emerging Economies 2020, 11, 429–445. [CrossRef]

- Park, Tae-Youn, and Jason D. Shaw. Turnover rates and organizational performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology 2013, 98, 268–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pestana, Maria Helena, and João Nunes Gageiro. Análise de Dados para Ciências Sociais—A Complementaridade do SPSS, 2003.

- Podsakoff, Phillip M. , Scott B. MacKenzie, Jeong Y. Lee, and Nathan P. Podsakoff. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiche, B. Sebastian. The configuration of employee retention practices in multinational corporations’ foreign subsidiaries. International Business Review 2008, 17, 676–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisenwitz, Timothy H., and Jie G. Fowler. Information Sources and the Tourism Decision-making Process: An Examination of Generation X and Generation Y Consumers. , 2019, 20, 1372–1392. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, Ricardo, Christina L. Butler, and David Guest. Evaluating the employability paradox: When does organizational investment in human capital pay off? The International Journal of Human Resource Management 2019, 31, 1134–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saba, Tania. Understanding generational differences in the workplace: Findings and Conclusions. Working paper Industrial Relations Centers – Queens University. Kingston. 2013.

- Santos, Cristiane, Marina Ariente, Marcos Diniz, M., and Aline Dovigo. O processo evolutivo entre as gerações X, Y e Baby Boomers. Comunicação apresentada no XIV SemeAD Seminários em Administração, São Paulo, Brasil. 2011.

- Schneider, Benjamim, Arthur P. Brief, and Richard Guzzo. Creating a climate and culture for sustainable organizational change. Organizational Dynamics 1996, 24, 6–19. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, Theodore W. Investment in Human Capital. The American Economic Review 1961, 51, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, Subhash. Applied Multivariate Techniques, 1996.

- Shore, Lynn M., Lois E. Tetrick, Patricia Lynch, and Kevin Barksdale. Social and economic exchange: Construct development and validation. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 2006, 36, 837–867. [CrossRef]

- The Ken Blanchard Companies.<i> The next generation of workers</i>. Escondido, U.S.A. The Ken Blanchard Companies. The next generation of workers, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Trochim, William. The Research Methods Knowledge Base, 2000.

- Tulgan, B. Trends point to a dramatic generational shift in the future workplace. Employment Relations Today 2004, 30, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twenge, Jean M. A review of the empirical evidence on generational differences in work attitudes. Journal of Business and Psychology 2010, 25, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Heijden, B. I. J. M., Jo Boon. Employability enhancement through formal and informal learning: An empirical study among Dutch non-academic university staff members. International Journal of Training and Development 2009, 13, 19–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitener, Ellen M. Do “high commitment” human resource practices affect employee commitment? A cross-level analysis using hierarchical linear modeling. Journal of Management 2001, 27, 515–535. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, Stephan, and Lilian de Menezes. High commitment management in the U.K.: Evidence from the workplace industrial relations survey and employers’ manpower and skills practices survey. Human Relations 1998, 51, 485–515. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).