Submitted:

26 February 2024

Posted:

26 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Column Experiment

| Value | pH | Conductivity, µs/cm | Turbidity, NTU |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Stormwater/ After filtration |

Initial Stormwater/ After filtration |

Initial Stormwater/ After filtration |

|

| Minimum | 6.66/7.05 | 86.5/118.5 | 0.10/0.15 |

| Medium | 6.92/7.46 | 92.6/189.4 | 0.15/0.21 |

| Maximum | 7.74/8.07 | 100.6/429.0 | 0.19/0.38 |

| Initial Stormwater |

I | II | III | IV | V | VI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | 7.9 | 5.5 | 6.6 | 5.8 | 6.5 | 5.9 | 6.8 |

| Conductivity, µS/cm |

2.9 | 649 | 601 | 569 | 741 | 524 | 492 |

| Turbidity, NTU | 0.173 | 0.041 | 0.003 | 1.543 | 0.180 | 0.005 | 0.007 |

| Color, AV | 1.193 | 0.169 | 0.008 | 0.072 | 0.012 | 0.005 | 0.031 |

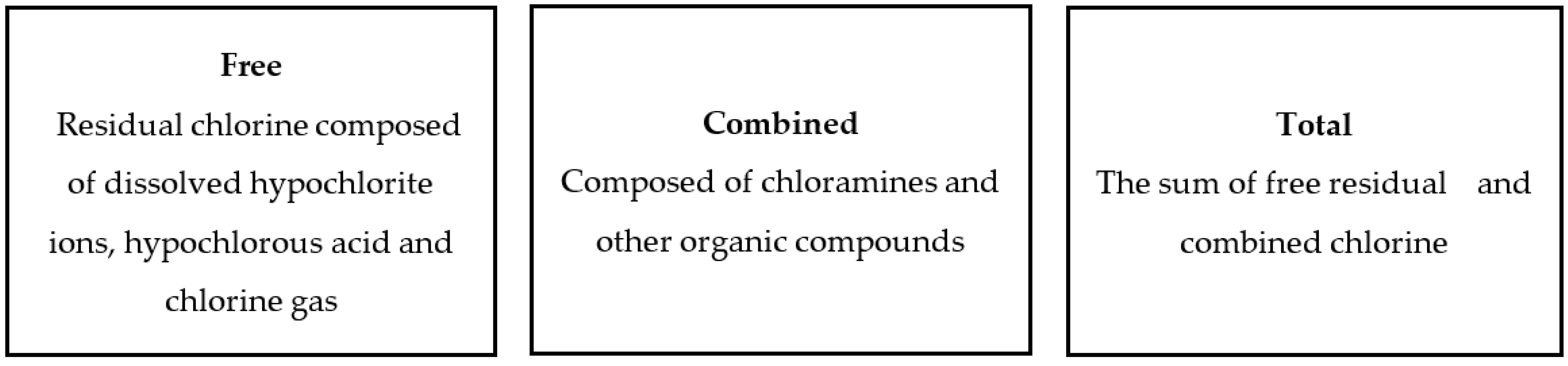

| Residual chlorine, ppm |

<0.01 | 0.02 | 0.60 | 0.46 | 0.08 | 0.01 | <0.01 |

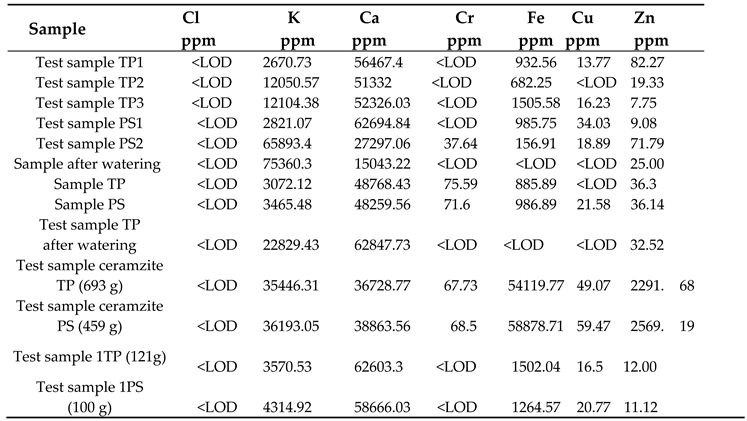

3.2. Batch Test

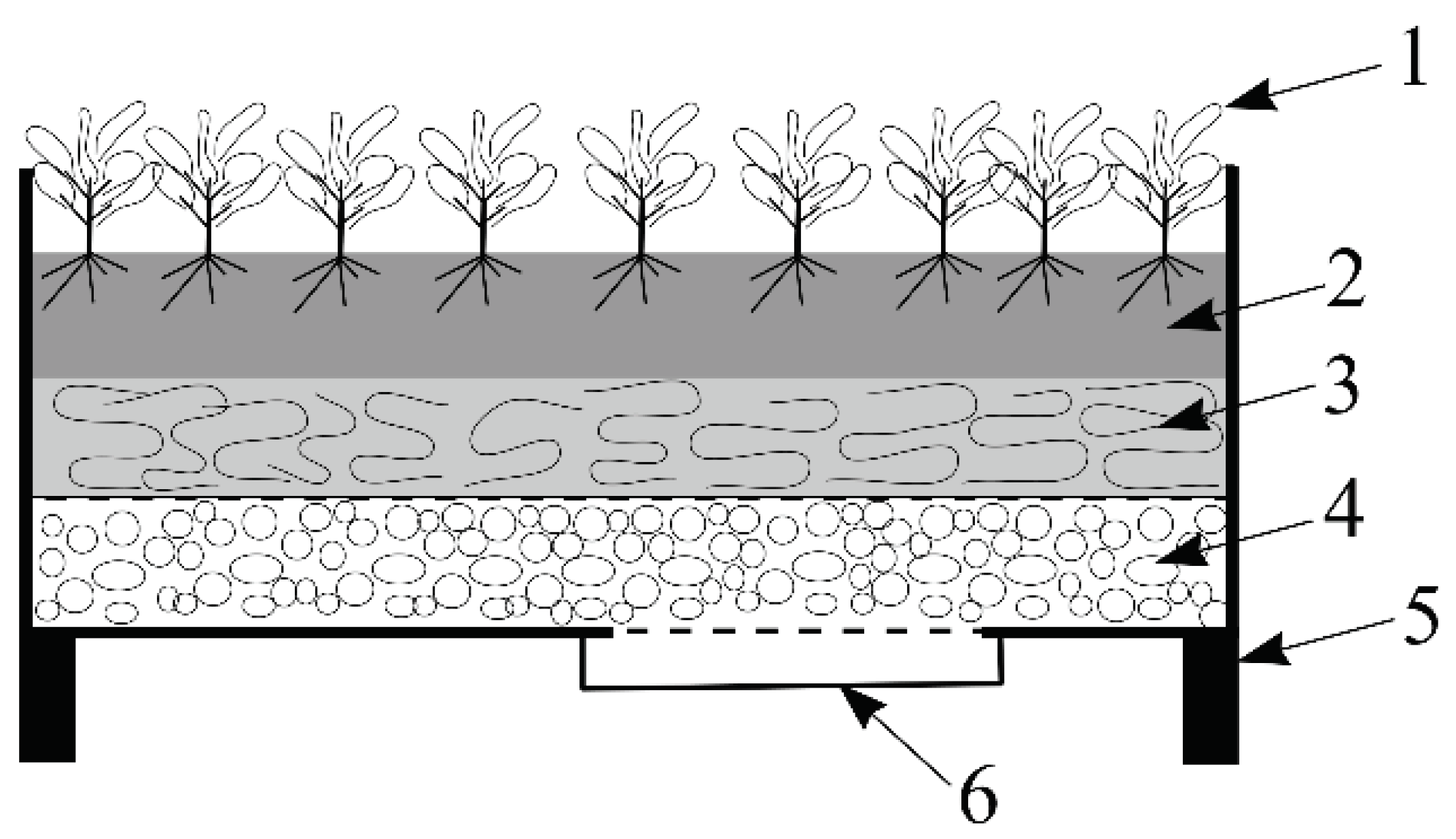

3.2. Raised Garden Bed

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- European Commision proposal for a DIRECTIVE OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL concerning urban wastewater treatment (recast) COM/2022/541 final https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52022PC0541 (accessed 26 November 2023.

- Feng, W.; Liu, Y.; Gao, L. Stormwater treatment for reuse: Current practice and future development - A review. Journal of Environ Management 2022, 301, 113830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boguniewicz-Zabłocka, J.; Capodaglio, A.G. Analysis of Alternatives for Sustainable Stormwater Management in Small Developments of Polish Urban Catchments. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commision. 2020 REGULATION (EU) 2020/741 OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL on minimum requirements for water reuse https://environment.ec.europa.eu/topics/water/water-reuse_en (accessed 26 November 2023).

- HELCOM. 2021 Recommendation 23/5-Rev. Reduction of discharges from urban areas byt the proper management of stormwater systems https://helcom.fi/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Rec-23-5-Rev.1.pdf (accessed 26 November 2023).

- Hopkins, K.G.; Grimm, N.B.; York, A.M. Influence of governance structure on green stormwater infrastructure investment. Environmental Science & Policy 2018, 84, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Kumar, S.; Singh, A. Assessment of Green Infrastructure for sustainable urban water management. Environment, Development & Sustainability, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Hong, J.; Jia, H.; Liang, S.; Xu, T. Life cycle environmental and economic assessment of a LID-BMP treatment train system: A case study in China. Journal of Cleaner Production 2017, 149, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union, 2013 European Union: European Commission, Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions Green Infrastructure (GI) — Enhancing Europe’s Natural Capital, COM/2013/0249 final. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A52013DC024 (accessed 26 November 2026).

- Mobilia, M.; Longobardi, A.; Sartor, J.F. Including A-Priori Assessment of Actual Evapotranspiration for Green Roof Daily Scale Hydrological Modelling. Water 2017, 9, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanakis, A.I. The Role of Constructed Wetlands as Green Infrastructure for Sustainable Urban Water Management. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grădinaru, S.R.; Hersperger, A., M. Green infrastructure in strategic spatial plans: Evidence from European urban regions. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening. 2019, 40, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orta-Ortiz, S.; Geneletti, D.M. What variables matter when designing nature-based solutions for stormwater management? A review of impacts on ecosystem services. Environmental Impact Assessment Review 2022, 95, 106802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Wang, Z.; Wang, C.; Huang, J.; Zhou, M. Chlorination in the pandemic times: The current state of the art for monitoring chlorine residual in water and chlorine exposure in air. Science of The Total Environment 2022, 838, 156193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, W.; Fang, C.; Deng, Y.; Xu, Z. Intensified Disinfection Amid COVID-19 Pandemic Poses Potential Risks to Water Quality and Safety. Environmental Science &Technology 2021, 55, 4084–4086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotirov, A. Increasing quantity of disinfectants at the environment. Academia Letters, 2021, Article 1290.

- Xue, B.; Guo, X.; Cao, J.; Yang, S.; Qiu, Z.; Wang, J.; Shen, Z. The occurrence, ecological risk and control of disinfection by-products from intensified wastewater disinfection during the COVID 19 pandemic. Science of The Total Environment 2023, 900, 165602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L.; Song, S.; Graham, N.J.D.; Yu, W. Direct generation of DBPs from city dust during chlorine-based disinfection. Water Research 2024, 248, 120839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poćwiardowski, W. The potential of swimming pool rinsing water for irrigation of green areas: a case study. Environmental Science & Pollution Research 2023, 30, 57174–57177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Ling, H.; Huang, X.; Li, J.; Li, W.; Yi, C.; Zhang, T.; Jiang, Y.; He, Y.; Deng, S.; Zhang, X.; Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, G.; Qu, J. Potential spreading risks and disinfection challenges of medical wastewater by the presence of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) viral RNA in septic tanks of Fangcang Hospital. Science of the Total Environment 2020, 74, 40445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, I.A.; Joshi, L.T. 2021 Biocide Use in the Antimicrobial Era: A Review. Molecules 2021, 26, 2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Praveen N., Chowdhury S. & Goel, S. 2022 Environmental impacts of the widespread use of chlorine-based disinfectants during the COVID-19 pandemic. Environmental Science & Pollution Research 29, 85742–85760. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, X. Comparative toxicity of new halophenolic DBPs in chlorinated saline wastewater effluents against a marine alga: halophenolic DBPs are generally more toxic than haloaliphatic ones. Water Research 2014, 65, 64–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fakour, H.; Lo, S.L. Formation of trihalomethanes as disinfection byproducts in herbal spa pools. Scientific Report 2018, 8, 5709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clayton, G. E.; Thorn, R. M. S.; Reynolds, D. M. Comparison of Trihalomethane Formation Using Chlorine-Based Disinfectants Within a Model System; Applications Within Point-of-Use Drinking Water Treatment. Frontiers in Environmental Science 2019, 7, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza. L.P.; Graça, C.A.L.; Teixeira, A.C.S.C.; Chiavone-Filho, O. Degradation of 2,4,6-trichlorophenol in aqueous systems through the association of zero-valent-copper-mediated reduction and UVC/H2O2: effect of water matrix and toxicity assessment. Environmental Science Pollution Research 2021, 28, 24057–24066. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Lu, T.; Zhang, J.; Sun, L.; Hu, B.; Hu, J.; Peñuelas, J.; Zhu, L.; Qian, H. Residual chlorine disrupts the microbialcommunities and spreads antibiotic resistance in freshwater. Journal of Hazard Materials 2022, 423, 127152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hwaiti, M.; Aziz, H.A.; Ahmad, M.A.; Al-Shawabkeh, R. Chlorine and chlorinated compounds removal from industrial wastewater discharges: A review. CMUJ. Nat. Sci. 2021, 20, e2021047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentukeviciene, M.; Andriulaityte, I.; Chadysas, V. Assessment of Residual Chlorine Interaction with Different Microelements in Stormwater Sediments. Molecules 2023, 28, 5358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, R.D.F.S.; Barbosa, M.L.S.; Silva, F.J.G.; Sousa, S.R.; Sousa, V.F.C.; Ferreira, B.O. Study of the Chlorine Influence on the Corrosion of Three Steels to Be Used in Water Treatment Municipal Facilities. Materials 2023, 16, 2514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhat, S.A.; Sher, F.; Kumar, R.; Karahmet, E.; Haq UA, S.; Zafar, A.; Lima, E.C. Environmental and health impacts of spraying COVID-19 disinfectants with associated challenges. Environmetal Science & Pollution Research 2021, 29, 85648–85657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentukeviciene, M.; Andriulaityte, I.; Zurauskiene, R. Experimental Research on the Treatment of Stormwater Contaminated by Disinfectants Using Recycled Materials—Hemp Fiber and Ceramzite. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19, 14486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gevorgyan, S.A.; Hayrapetyan, S.S.; Hayrapetyan, M.S.; Khachatryan, H.G. Express evaluation of sorption mechanism on peat containing materials. Periodico Tche Quimica 2020, 17, 469–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laohaprapanon, S.; Marques, M.; Hogland, W. Removal of Organic Pollutants from Wastewater Using Wood Fly Ash as a Low-Cost Sorbent. Clean Soil Air Water 2010, 38, 1055–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bus A;, Karczmarczyk, A.; Baryla, A. Wybór materiału reaktywnego do usuwania fosforu z wód i ścieków na przykładzie kruszywa popiołoporytowego Pollytag® (Choosing of reactive material for phosphorous removal from water and wastewater on the example of lightweight aggregate Pollytag®) Inżynieria Ekologiczna 2014, 39, 2014, 33–41, Poland.

- Karczmarczyk, A.; Baryła, A.; Bus, A. 2014 Effect of P-Reactive Drainage Aggregates on Green Roof Runoff Quality. Water 2014, 6, 2575–2589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Cleaning and Disinfection of Environmental Surfaces in the Context of COVID-19: Interim Guidance; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/332096 (accessed 26 November 2023). [Google Scholar]

- Samudro, G.; Mangkoedihardjo, S. Mixed plant operations for phytoremediation in polluted environments – A critical review. Journal of Phytology 2020, 12, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Faiq, M.E.; Elahi, S.; Hashmi, S.I.; Akhtar, S.; Jamil, A.; Sharif, M.; Ullah, S.; Zakerullah; Mansoor, S.; Nazir, R. Phytoremediation of pollutants from wastewater using hydrophytes: A case study of Islamabad, Pakistan. Journal of Biodiversity and Environmental Sciences 2021, 19, 36–49, https://www.innspub.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/JBES-V19-No5-p36-49.pdf (accesed 27 November 2023). [Google Scholar]

- Obinna, I.B.; Ebere, E., C. Phytoremediation of Polluted Waterbodies with Aquatic Plants: Recent Progress on Heavy Metal and Organic Pollutants Analytical Methods in Environmental Chemistry Journal 2019. https://www.preprints.org/manuscript/201909.0020/v1 (accessed 27 November 2023).

- Kulandaiswamy, N. D. M.; Nithyanandam, M. Feasibility Studies on Treatment of Household Greywater Using Phytoremediation Plants Research Square 2021. [CrossRef]

- Sivaram, A.K.; Logeshwaran, P.; Lockington, R.; Naidu, R.; Megharaj, M. Phytoremediation efficacy assessment of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons contaminated soils using garden pea (Pisum sativum) and earthworms (Eisenia fetida). Chemosphere 2019, 229, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biswal, B.; Singh, S. K.; Patra, A.; Mohapatra, K.K. Evaluation of phytoremediation capability of French marigold (Tagetes patula) and African marigold (Tagetes erecta) under heavy metals contaminated soils, International Journal of Phytoremediation 2022, 24, 945-954. [CrossRef]

- Fridrick, L.; Valentukevičienė, M. Hemp as a sorbent for disinfectant – polluted watertreatment. Conference: AQUA 2021, Plock, Poland. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/358125963_HEMP_AS_A_SORBENT_FOR_DISINFECTANT-POLLUTED_WATER_TREATMENT (accessed 26 November 2023).

- Cheng, Z.; Guan, H.; Meng, J.; Wang, X. Dual-Functional Porous Wood Filter for Simultaneous Oil/Water Separation and Organic Pollutant Removal. ASC Omega 2020, 5, 14096–14103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, I. , Asim M.; Khan T.A. Low cost adsorbents for the removal of organic pollutants from wastewater. Journal of Environmental Management. 2012, 113, 170–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šimėnaitė R. Fitoremediacija: augalų įvairovė ir ekspozicijos įrengimas. https://www.botanikos-sodas.vu.lt/files/fitor1.pdf (accessed 27 November 2023).

- Ansari, A. A.; Naeem, M.; Gill, S.S.; Alzuaibr, F.M. Phytoremediation of contaminated waters: An eco-friendly technology based on aquatic macrophytes application. The Egyptian Journal of Aquatic Research 2020, 46, 4–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Initial Stormwater |

I | II | III | IV | V | VI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | 7.5 | 8.9 | 9.8 | 9.9 | 10.1 | 10.1 | 10.8 |

| Conductivity, µS/cm |

20.9 | 481 | 553 | 604 | 581 | 615 | 522 |

| Turbidity, NTU | 1.248 | 1.396 | 1.345 | 1.312 | 1.244 | 1.217 | 1.266 |

| Color, AV | 0.128 | 0.224 | 0.192 | 0.163 | 0.130 | 0.119 | 0.142 |

| Residual chlorine, ppm |

<0.01 | 0.35 | 0.29 | 0.22 | 0.23 | 0.39 | 0.15 |

| Initial Stormwater |

I | II | III | IV | V | VI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | 8.3 | 9.8 | 8.3 | 8.1 | 7.6 | 8.3 | 8.6 |

| Conductivity, µS/cm |

40.6 | 643 | 600 | 764 | 671 | 643 | 639 |

| Turbidity, NTU | 1.151 | 1.249 | 1.370 | 1.205 | 1.265 | 1.160 | 1.131 |

| Color, AV | 0.084 | 0.104 | 0.118 | 0.089 | 0.131 | 0.080 | 0.067 |

| Residual chlorine, ppm |

<0.01 | 0.48 | 0.28 | 0.17 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.08 |

| Ceramzite mass, g | I ppm |

II ppm |

III ppm |

IV ppm |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial stormwater | 3.52 | 4.02 | 3.97 | 4.11 | |

| J1 | 159.93 | 2.00 | 3.36 | 3.84 | 3.80 |

| J2 | 178.36 | 2.03 | 2.18 | 3.38 | 3.83 |

| J3 | 151.34 | 2.03 | 3.52 | 3.54 | 3.89 |

| J4 | 65.16 | 1.54 | 1.08 | 1.25 | 0.89 |

| J6 | 71.70 | 0.87 | 0.72 | 0.81 | 1.97 |

| J7 | 72.43 | 1.17 | 1.03 | 1.63 | 1.07 |

| Ceramzite mass, g | I ppm |

II ppm |

III ppm |

IV ppm |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial stormwater | 2.26 | 4.06 | 3.56 | 2.08 | |

| J7 | 172.51 | 1.88 | 3.78 | 3.48 | 2.04 |

| J8 | 185.02 | 1.58 | 3.72 | 3.46 | 1.84 |

| J9 | 159.75 | 2.23 | 4.02 | 3.40 | 1.80 |

| J10 | 181.97 | 1.92 | 3.86 | 3.32 | 1.82 |

| J11 | 187.53 | 1.98 | 3.24 | 2.76 | 2.00 |

| J12 | 190.74 | 1.64 | 3.66 | 3.18 | 1.88 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).