1. Introduction

Mangrove forests are among the most productive ecosystems on Earth [

1]. They are of great importance to society; providing a wide array of goods and services to people including harvestable wood and non-wood products, coastal protection, biodiversity conservation, and climate regulations [

2,

3]. However, human influence on mangrove ecosystems is significant and has led to global loss and degradation of these forests at rates of 1-2% per year[

4,

5,

6]. Though the

rate of decline may now be less globally, loss of mangrove is ongoing and higher in certain areas [

7,

8]

In most governance contexts, the management of mangrove forests is a shared responsibility of different national or subnational agencies [

9,

10]. This often leads to conflicts due to poor institutional coordination or unclear delineation of competences [

11]. Some mangrove forests transcend international boundaries, further complicating their management across the transboundary areas. This is because international borders are political and thus any shared resources are separated and put under different management regimes. Marine ecosystems including mangroves are often characterized by unsustainable resource use patterns leading to habitat destruction, biodiversity loss, and increased suffering to people depending on them [

12,

13,

14,

15]. In transboundary areas this may even be exacerbated because of lack of enforcement and other governance priorities for such border regions [

16]. In the transboundary area of Kenya and Tanzania illegal and over-exploitation of resources, alterations of the freshwater flow, and climate-related hazards are some of the threats mangrove ecosystems are facing [

17,

18,

19]. Consequently, this has resulted to reduction in fisheries harvest, shortage of firewood and [

8,

20] building materials, and increased shoreline erosion [

10,

21]. A collaborative management framework is essential to ensure sustainability of natural capital within the transboundary areas. One of the governance approaches would be the establishment of transboundary conservation areas to protect ecosystems and mitigate threats that extend multiple jurisdictions and boundaries; development of joint management plans, across borders and including a wide range of mangrove management stakeholders. The governments of Kenya and Tanzania have initiated a process for the development of a transboundary conservation area (TBCA) spanning the coastal area from Diani in Kenya to Tanga in Tanzania. The projected TBCA aims at the conservation of land and seascape and the ecosystems present, for continued provisions of goods and services to people within the area [

18]. Prior to the establishment of TBCA bio-physical baseline data are required to enable the monitoring of changes over time. Some of the baseline data required include status and conditions on natural capital, house-hold data, and utilization patterns of key resources within and adjacent to the TBCA. The current study aimed at providing data and information on harvestable mangrove products within the Kenyan side of TBCA; their utilization patterns and drivers of change, in order to contribute to their sustainable utilization.

Mangrove management within and adjacent to the TBCA

Mangroves in Kenya and Tanzania are gazetted as forest reserves which restricts their use by communities. There have been significant advances regarding mangrove management at the national level in both Kenya and Tanzania that include development of national mangrove strategies. In Kenya, the development and sustainable management of forest resources, including mangroves, is provided by the Forest Conservation and Management Act (FCMA) of 2016 and its amendments. Communities have the legal mandate to co-manage designated forest areas through: registrations of a Community Forest Association (CFA), an approved Participatory Forest Management Plan (PFMP), and the signing of a Forest Management Agreement (FMA) specifying user rights and benefits that accrue to communities. Through the FCMA, communities are allowed access to both consumptive and non-consumptive forest resources and activities such as fuel wood collection; beekeeping; ecotourism; collection of medicinal herbs; harvesting of timber and other benefits which may from time to time be agreed upon between the CFA and KFS. The Fisheries Act 2016 and the Beach Management Unit (BMU) regulations and their revisions, authorize collaborative management of fisheries resources and provide for the protection of fish breeding areas, including mangroves[

22]

The Kenya Forest Service (KFS) is the national institution vested with responsibilities of managing all forests in the country, including mangroves. KFS issues licenses and monitors harvest operations. To remove a head load of firewood, community members pay KFS a cess equivalent to KSh100 (

USD 0.66) per month. A license to remove building poles costs about USD 100

per annum. With this permit, a licensee is granted quota to harvest mangroves within a designated area for one year [

23,

24]. Depending on the resource base, KFS can grant more than one licensee to operate in the same forest block. Licensees will then hire local cutters to remove the forest products. Cutters inform the licensee about the number of poles harvested and the licensee in turns informs KFS. The numbers cut are counted, the fee paid and the poles are hammer-marked [

23] making them ready for the market. In 2018, however, the Cabinet Secretary in charge of Environment and Forests in Kenya imposed a ban on further mangrove harvesting with the objective of increasing the country's forest cover and curb illegal logging of mangrove trees. In 2019 this ban was partially lifted in Lamu County where mangrove harvesting is a major livelihood activity.

In mainland Tanzania, the Forest Act (2002) provides for the participatory management of forests, including mangroves. Mangrove Collaborative Management Plans (MCMP) are developed to guide the use and conservation of mangrove ecosystems. Village Environmental Management Committees (VEMC) are established to implement the MCMPs. Despite forest-users having exclusive rights to the products, the forests remain the property of the Central Government [

15]. Harvesting mangroves for commercial purposes requires a harvesting permit from the District Forestry Officer (DFO). Communities living adjacent to forests are required to apply for a harvesting license for subsistence use. Priority is given to applicants with modern harvesting technologies; the area to be harvested should be indicated in the district harvesting plan and issuing the harvesting license will be based on the past experience of the applicant. The applicant will then be requested to report to the villages adjacent to the forest that will be harvested and present his/her license. Unlike in Kenya where it is the licensee who informs KFS the number of poles they have harvested, in Tanzania, the Village Council together with the DFO supervise the harvesting to make sure that the allowed species and numbers of trees are harvested, as indicated in the license [

25,

26].

Despite the existence of a legal framework for mangroves and the recognition of community rights in Kenya and Tanzania, there have been additional institutional challenges in mangrove management. For instance in Tanzania, inadequate coordination between forestry and marine conservation agencies has resulted in ineffective mangrove management [

27]. Poor interaction with local communities has also been highlighted as drawbacks for their efficient conservation [

28]. Governance and institutional issues which have intensified mangrove degradation in Kenya mainly include uncoordinated sectoral approach to management due to overlapping or conflicting mandates, weak enforcement of existing legislation and inadequate institutional capacities [

17].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Descriptions of the study area

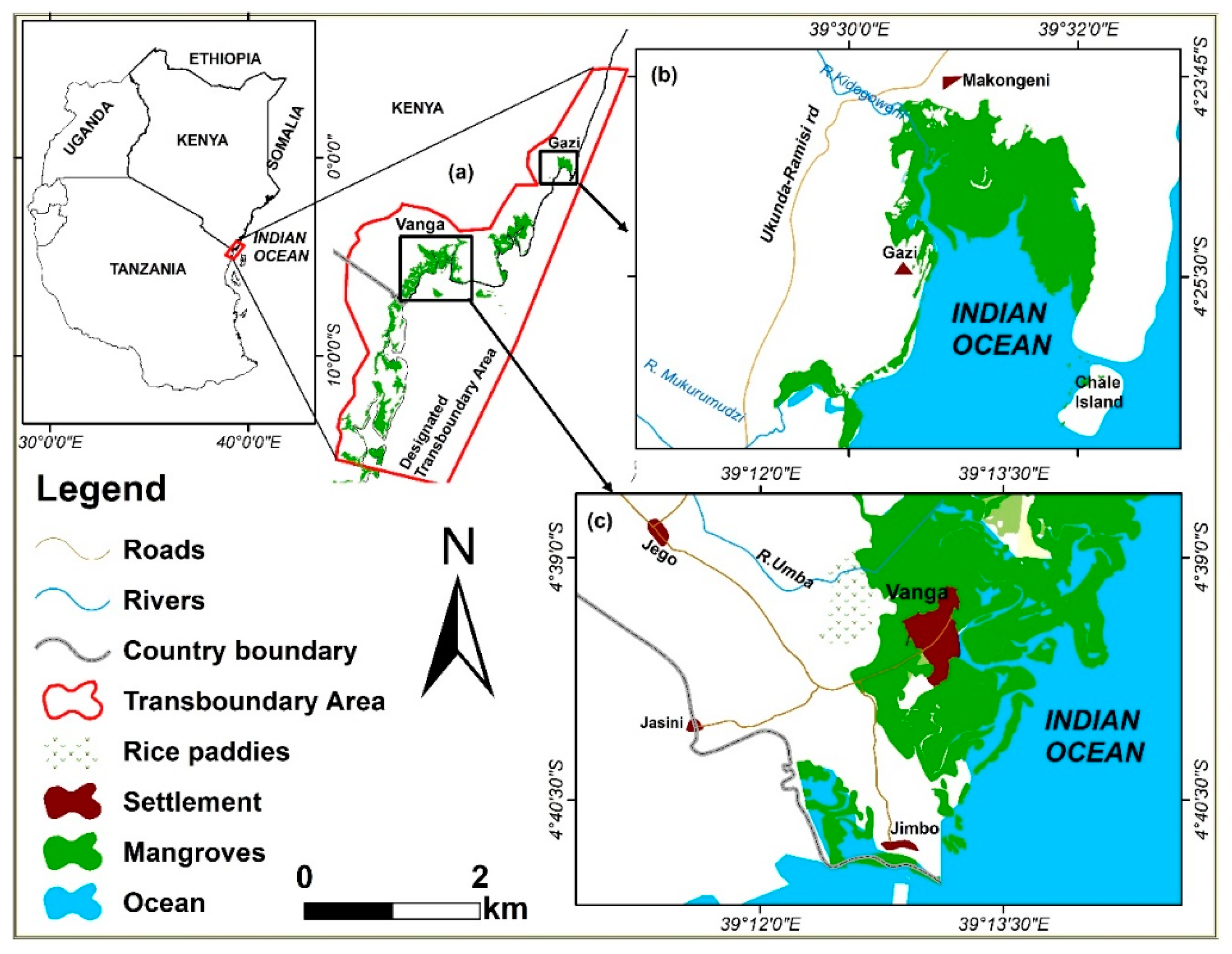

The projected Kenya-Tanzania Transboundary Conservation Area spans the coast from Diani in Kenya (39°0’0′′ E, 4°25’0′′ S) to Tanga in Tanzania (39°40’0′′ E, 5°10’0′′ S); a stretch of approx. 200 km (

Figure 1). The TBCA is endowed with numerous coastal and marine resources that play a significant role in local economies and national development. One of the significant ecosystems within the TBCA are mangrove forests [

18].

These forests provide harvestable goods and services to people such as building poles, firewood, fodder, fish, and honey, but there are also non-consumptive uses. Mangroves provide habitat for fish and other wildlife, protect shoreline from erosion, and contributes to offshore productivity [

17]. All the nine mangrove species described in the region occur within the TBCA. The dominant species are

Rhizophora mucronata (Swahili: Mkoko) and

Ceriops tagal (Mkandaa) occupying more than 70% of forest formation. Other mangrove species in the area include

Avicennia marina (Mchu),

Sonneratia alba (Mlilana)

, Brugueira gymnorrhiza (Muia)

, Xylocarpus moluccensis (Mkomafi dume)

, Xylocarpus granatum (Mkomafi),

Heritiera littoralis (Msikundazi) and

Lumnitzera racemosa (Kikandaa) [

19]. Other plant species associated with mangrove trees also occur but are quantitatively marginal.

In terms of socio-economic characteristics, the TBCA has a rapidly growing human population with nearly 60% of the rural communities dependent on marine and coastal resources for their livelihoods [

18]. These communities share many aspects of culture, religion, livelihoods and also have cross-border family ties, despite being separated by political boundaries (

ibid.). Fishing is the main economic activity of communities in the area, providing food and contributing to livelihood support. While fishing is predominantly a male activity, women engage in fish-related activities such as fish mongering. The current study concerned mangrove utilization within the Kenya’s side of TBCA.

Respondents were selected from Gazi Bay and Vanga area (Vanga, Jimbo, Jasini villages). Gazi Bay area has a population of approximately 6000 inhabitants distributed over Gazi and Makongeni villages. Total area of mangroves in Gazi Bay is estimated as 715 ha [

17]. Vanga area has a permanent human population of approximately 7900 people and a mangrove area of 4428 ha [

29,

30].

2.2. Methods

Systematic random sampling design was used to generate household data in the 5 study sites (2 villages in Gazi Bay area, 3 villages in Vanga area). Sampling was maintained at 10 – 15% of total households as recommended by Mugenda & Mugenda [

31]. Overall, some 152 household surveys (

Table 1) as well as 12 Nominal Group Technique-applications were conducted. The study took place in April 2019 (

Table 2).

The Nominal Group Technique, a structured approach to a Focus Group Discussion, followed the process described by Hugé and Mukherjee (2018) [

32]. Nominal Group Technique is an interactive group decision-making technique primarily to elicit judgment from stakeholders. It involves several steps where participants are first requested to provide information individually (hence nominal) to questions asked by a moderator and then all ideas generated are listed. Participants are then invited to seek clarification or further elaboration on any of the ideas proposed by the other participants. The moderator collates all information, creates a list of unique items and then asks participants to select and rank the ideas from the list generated. The most highly rated ideas are then the most favored actions

(ibid).

Dagaa-sardines

The data collected was cleaned, coded, and analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistics. Chi-square tests (χ²) were used to determine whether there was any significant difference (p< 0.05) in mangrove use patterns between the Vanga area and Gazi Bay as well as among the 5 villages. Ranking of mangrove goods and threats facing them was used to gauge the perceived levels of importance of these goods and the severity of the threats. Data analysis and graphical presentation of the results were performed using both Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version. 23 and Microsoft Excel platforms.

Ethical clearance for the study was granted by the Pwani University Ethical Review Committee, and the National Commission for Science, Technology, and Innovation issued the research permit. Further, research clearance was obtained from the local administration in the study sites to conduct the study.

3. Results

3.1. Use of Mangrove forest products

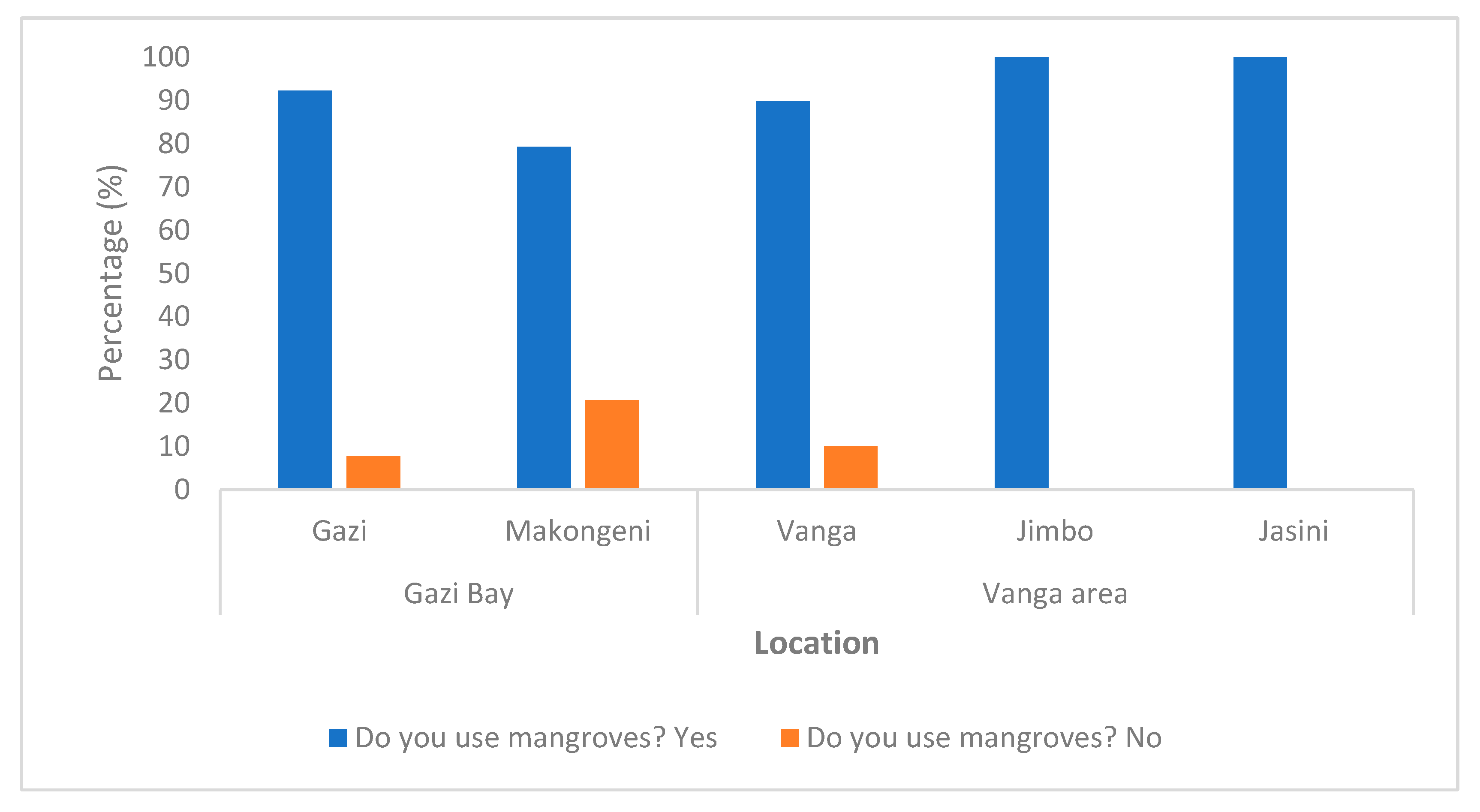

At least 90% of respondents indicated using mangrove goods directly (

Figure 2). There was no significant difference in the respondents use of mangrove goods among the study sites (χ² = 5.284, d.f = 8, p = 0.259).

A total of 16 different products were reported to be extracted from mangrove forests in the study area. The most valuable mangrove product as reported was firewood followed by fisheries resources, building poles, honey, and traditional medicine (

Table 3).

Non-wood resources extracted from the mangrove forests include honey, shellfish, bait, and traditional medicines. To reduce overdependence on mangrove wood for building and energy, communities within TBCA (Kenya) have resorted to using alternative products such as coconut husks and charcoal and timber sourced from terrestrial forests. There was a significant difference in the alternative sources of wood products across the sites (χ² = 16.9, d.f.=8, p=0.031). Further, communities in Gazi area (Gazi and Makongeni villages) have established woodlots of fast-growing terrestrial tree species to meet some of their wood requirements.

3.. Patterns of mangrove resource use in the TBCA (Kenya)

Of all mangrove products, fisheries products are the most important resource extracted daily from the forest, at 48% of reported use frequency (

Table 4).

On a weekly basis, the most extracted product was firewood (32%). Other forest products such as medicine and repair timber for houses and boats were extracted as their needs arose. In Jimbo village (Vanga area) and Gazi village (Gazi Bay area) the collected firewood was mainly used for boiling of sardine fish (or dagaa). A total of 125 and 20 registered dagaa dealers were reported in Jimbo and Gazi villages respectively. The frequency of use of firewood by the dagaa dealers depended on the quantity of fish they boiled per day (Table 5). On average, dagaa sellers boil 2-4 baskets of sardines per day. <<can we guess

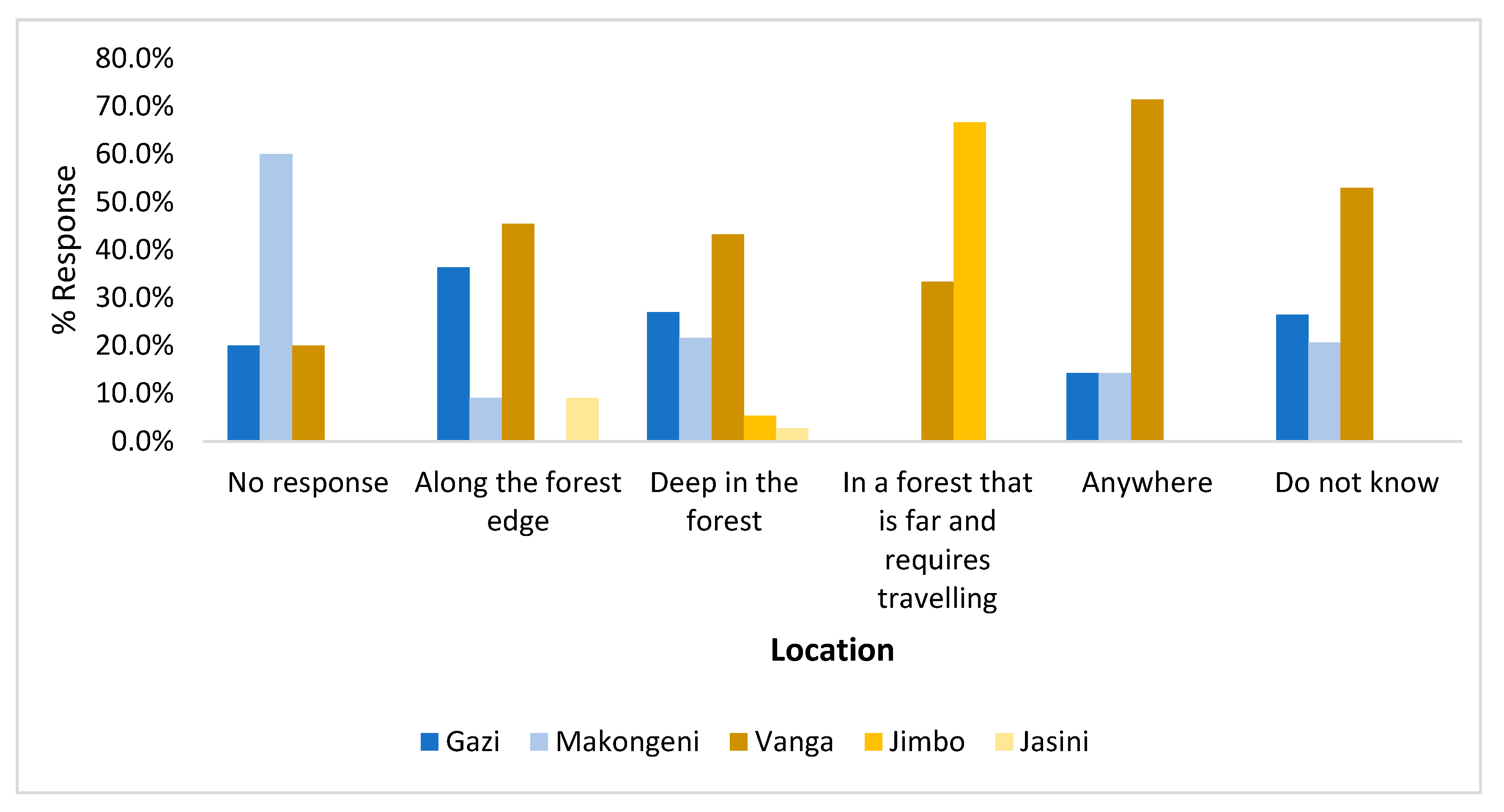

3.2.1. Harvesting locations

On the question where mangrove products were extracted, at least 50% of the respondents indicated that the products were sourced deep in the forest. Some 23% of the respondents were not aware how the mangrove products were extracted as they did not use the products or because they were not the ones who did the actual harvesting. About 15% of the respondents reported to collect firewood along the forest edge, 5% collected randomly, whereas 4% reported fetching firewood from deep in the forest (

Figure 3). There was a significant difference between areas where mangrove products were harvested across the study sites (χ² = 62.219, d.f = 20, p<0.001).

At least 66.7% of respondents in Jimbo village indicated collecting mangrove wood from deep in the forest. They specified crossing into the Tanzanian side and extracting firewood from Kigomeni, Mbayai and Kendwa sites.

3.2.2. Mangrove harvest permits

The respondents indicated applying for licenses to harvest mangrove wood products from KFS. However, the harvesting systems were different in Gazi and Vanga areas. While Gazi communities purchased mangrove poles directly from a licensed harvester at fixed price, in Vanga wood was purchased from different mangrove cutters at various prices. (

Table 6).

Firewood in Vanga area (Vanga, Jimbo and Jasini) is sold by harvesters at different prices depending on the quantity required (

Table 7). These cutters have continued with their activities despite the ban on harvesting mangrove products which is illegal.

There was no significant difference in the access level of mangrove products among the study sites (χ² = 15.935, d.f = 8, p = 0.048). When respondents were asked whether it has become easier or more difficult to harvest mangroves, 74% indicated that it has become more challenging due to access restrictions and shortages. Consequently, this has continued to negatively impact the people who lack alternative sources of wood for building and energy.

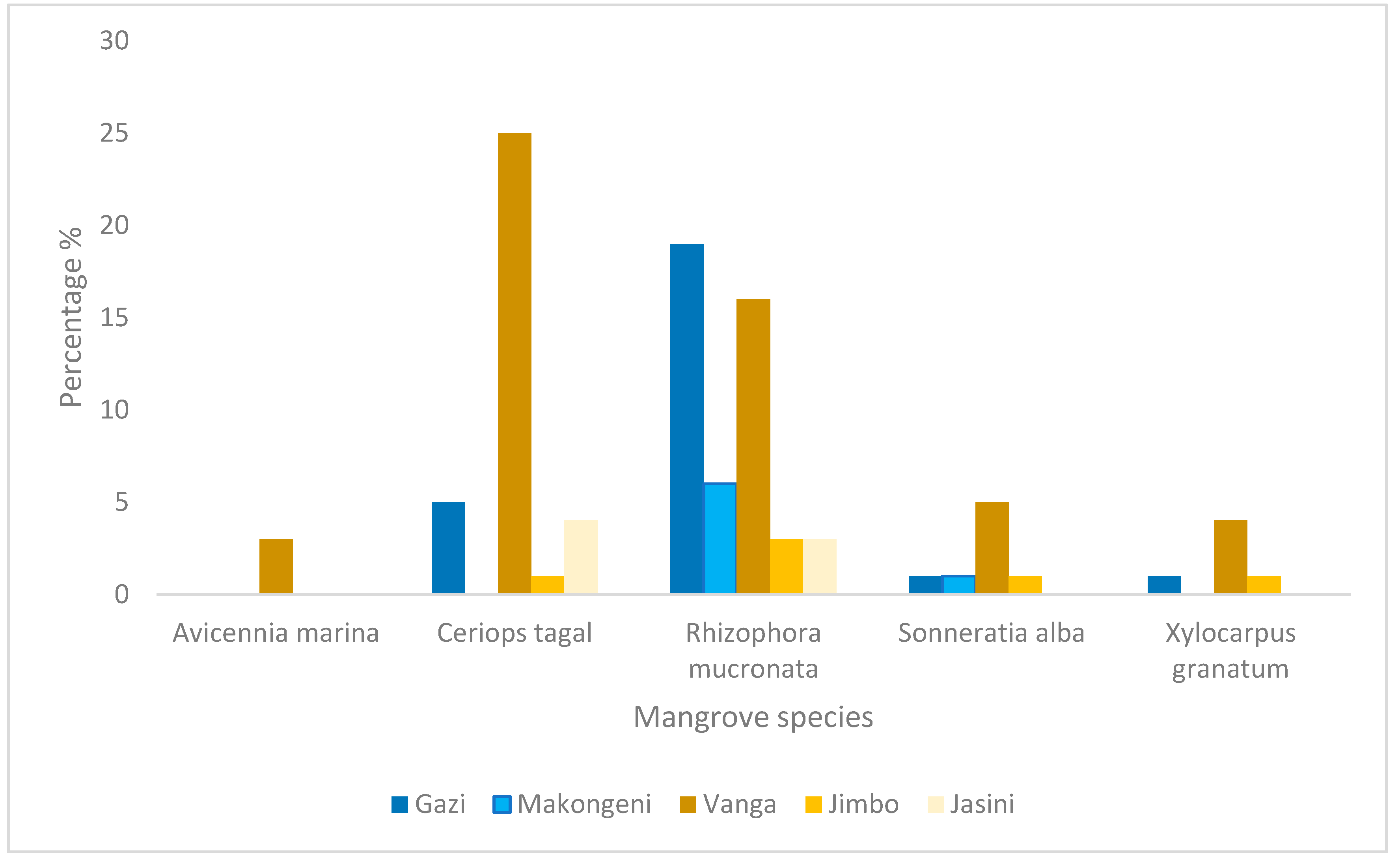

3.2.3. Mangrove species preference

Communities within TBCA could correctly identify different mangrove species in their areas, their local names, and the parts of the tree that are used (

Table 8).

Across all study sites, the preferred mangrove tree species are

Rhizophora mucronata (Mkoko),

Ceriops tagal (Mkandaa) and

Sonneratia alba (Mlilana) for wood. Mangrove trees are harvested by the local communities for building poles, firewood, furniture, and boat ribs. At Gazi Bay,

Rhizophora mucronata is the most exploited mangrove species, whereas in Vanga

Ceriops tagal is mostly preferred (

Figure 4). Communities also collect honey, traditional medicine, shellfish, and fish baits from mangrove areas.

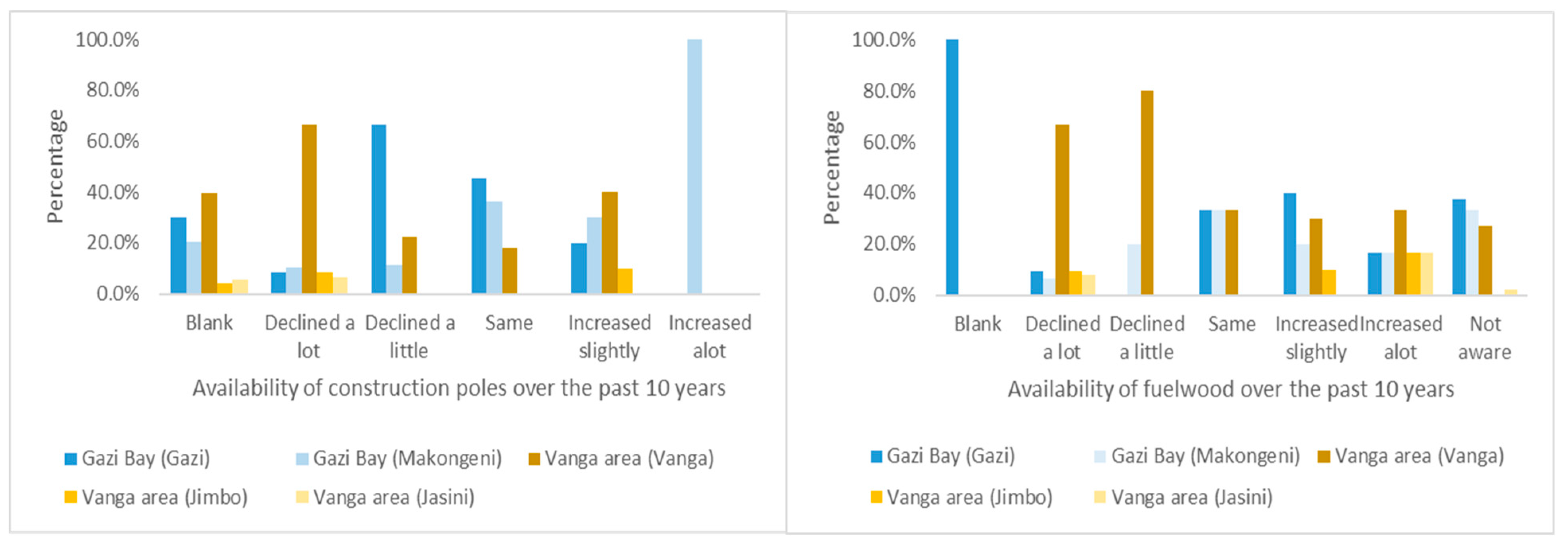

3.2.3. Perceived condition of mangroves in the TBCA (Kenya)

Fifty-two percent (52%) of the respondents gave their views on the availability of construction poles over the past 5 years. Thirty-seven percent (37%) of them felt that availability of construction poles had decreased, 7% indicated that availability had stayed the same, while 7% felt that the availability had slightly increased. From the 65% of the respondents who gave their views on the availability of firewood, 45% felt that the availability had decreased, 10% indicated that availability was the same, while 11% felt that firewood availability had increased. Decline in both construction poles and firewood was reported more in Vanga area as compared to Gazi Bay (

Figure 5).

3.3. Threats to mangroves within TBCA as reported by respondents.

Across all the sites, major threats facing mangroves within and adjacent to TBCA were reported as over-exploitation of wood products, shoreline change, and sedimentation. Other threats were identified as pollution, storm charges, insect infestation and climate change. Despite being mentioned in one workshop only, lack of security was indicated as a threat by 3 respondents. Threats that were mentioned in only one workshop were eliminated. This includes seedling trampling, use of power saws, freshwater obstruction, infrastructure development, clearing of mangroves for shrines, population increase, corruption and fire outbreak (

Table 9)

4. Discussion

4.1. Use of Mangrove forest products

Various mangrove tree species are used for different purposes worldwide [

11]. Within the Kenya-Tanzania transboundary area, mangrove forests provide harvestable wood and non-wood products such as building poles, and firewood, honey, traditional medicine, mangrove tannin , and fisheries resources. This is in addition to the habitat and protective functions provided by the forested ecosystem. Our results (for the projected Transboundary Conservation Area at the Kenyan side) are consistent with previous observations in Kenya [

33,

34] and other parts of the world such as Bangladesh Benin, , Brazil, India, Philippines and Thailand, where mangroves were shown to provide multiple goods and services to the society [

11,

35,

36].

Major use of mangroves within Kenyan side of the TBCA is in building and firewood. In Kenya, it is estimated that 70% of the wood requirement by the coastal communities is met by mangrove forests[

17]. Differences between villages in mangrove areas were observed, but are limited, a general pattern appears indeed. Mangrove wood is generally preferred for fuel because it is dense and of high heat capacity compared to other trees species [

11,

37,

38]. However, in Southwest Madagascar, communities prefer firewood obtained from dry forests for being drier and more easily combustible than local mangrove wood [

34]. Generalization is thus not possible as to the role of mangrove wood due to difference in preferences in different areas worldwide which makes local reports relevant. Several mangrove species are also resistant to termites and as such preferred for building and constructions [

17,

37,

38]. Different size classes of mangrove poles are used for construction within the TBCA,

Rhizophora mucronata is the preferred mangrove species for building because it grows tall, straight, and is resistant to termite attack[

19]. On the other hand,

Ceriops tagal is mainly used due to its high availability. Other species, like S

onneratia alba and

Xylocarpus granatum are used for boat building and furniture because they attain large sizes, and the wood is easy to adapt or fits to the required curve.

GOK 2017,[

16] indicates that more than 85% of fishing activities along the coast are carried out by artisanal fishermen in the shallow inshore areas within and adjacent to the mangroves, which directly employ more than 20,000 fishers. This was observed in the study site where fish is among the most important and frequently extracted resource from the forest with shrimp fry, prawn and crab collection providing food and contributing to household livelihood support. Non -wood products such as medicine is reported to come from

Xylocarpus granatum seeds, which are valued for their curative properties of jiggers, cramps and stomache, and body aches. This medicinal value has a positive impact on the local population’s health.

Avicennia marina leaves and those of Ceriops tagal on the other hand were reported to remove demons from a possessed person. These leaves are also used as insecticides i.e. mosquito repellant as well as to remove parasite from chicken. Mangrove tannin, which is used for decorating mats and a colorant used by women for beauty purposes, is extracted from the bark of

Rhizophora mucronata and

Ceriops tagal. Fruiting of

Sonneratia alba is reported to tell the current season, while falling of

Avicennia Marina leaves marks the beginning of dry season).

4.2. Mangrove use and conservation

There is a high frequency of harvesting mangrove wood products within the TBCA (here reported for Kenya). However, most of these harvesting campaigns are not legal and thus unreported to KFS. This was mainly observed in Vanga where there is a tendency of managing mangroves as an

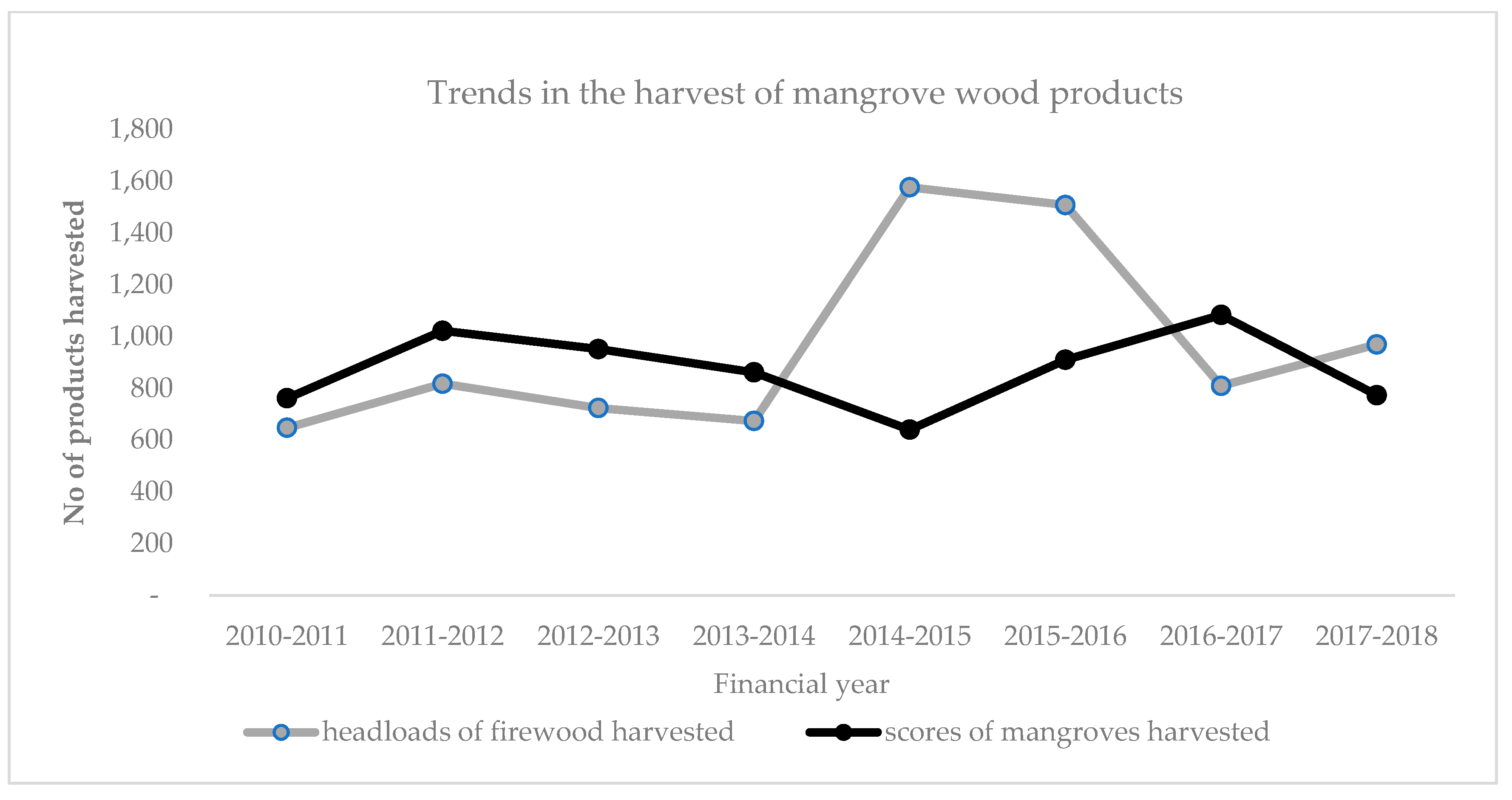

open pool system. These findings are contrary to the reported trends of mangrove wood utilization in the area that indicate minimal harvesting (

Figure 7).

Selective harvesting of mangroves (whether legal or illegal) is a common practice amongst communities within and adjacent to the TBCA. The findings are consistent with other studies elsewhere, whereby,

boriti sized poles (butt diameter

8-13 cm) are preferred for construction; with R. mucronata being the main targeted species [

33]

. This is followed by

mazio (7-9 cm and

pau (5-7 cm) utilization classes used for construction. This is consistent with results elsewhere in Kenya, e.g. in Lamu [

24], Mida [

33,

39], and Mtwapa Creek [

40] where selective removal of desired species and pole sizes have led to forest degradation or floristic shifts. In mixed stands of

Rhizophora mucronata and

Ceriops tagal, selective logging of

R. mucronata has been shown to promote colonization by

C. tagal .[

39]

Harvesting of mangrove wood products within the TBCA may be viewed mainly small scale which is often perceived to have limited ecological impact [

41]. However, studies elsewhere have revealed that if not controlled, small-scale harvesting practices result in cumulative effects leading to structural changes and species dominance shifts in the mangrove forest [

38,

42,

43,

44,

45].

Local people also intentionally forage for deadwood from the forest for fuel. They collect dry mangrove branches and stems on a weekly basis with consumption dramatically increasing during weddings and other celebrations, when households (including those that use alternative fuel) use mangrove wood for cooking. Demand for firewood for commercial purposes was also observed to be on the rise due to increase in number of

dagaa dealers who use firewood to boil sardines in the study sites. Foraging for deadwood can reduce levels of naturally occurring deadwood. Wang’ondu et al. (2017) [

46] observed that continued cutting of these preferred species before maturity, primarily for house construction, affects the stand structure of mangroves forests near human habitation. This was observed in the study sites where preference for certain mangrove species and a decline of products such as firewood and poles over the years have made community members in the study area go deeper into the forest in search for them. Decline in both construction poles and firewood was reported more in Vanga area as compared to Gazi Bay which is consistent with similar studies carried out in the area [

29] which showed Vanga to be a hotspot for mangrove loss and degradation.

Mazio and

boriti-sized poles (8-14 cm) have also been reported to be limited in the area due to illegal harvesting that is rampant and noticeable [

17]..

A temporary ban on mangrove logging imposed in 2018 has resulted in unsustainable practices and negative effects on community livelihoods due to a lack of (known) alternatives, For instance, in Vanga Bay, firewood collectors use boats to cross the border and access firewood from mangroves on the Tanzanian side from islands that are not occupied by people Apart from being illegal, these practices pose a management challenge to mangrove management in Tanzania.

There are however conservation efforts in the study sites that are supporting restoration and protection of mangrove forests within TBCA. Mikoko Pamoja, for example, an initiative by Gazi communities which seek to conserve and restore mangroves for community livelihood and environmental sustainability. Mikoko Pamoja is globally the first community-type project to protect and restore mangroves through the sale of carbon credits on the voluntary carbon market. Revenue generated from sales of carbon credits is used to support local development projects in water and sanitation, education, health and environmental management [

47]. The project has been replicated in Vanga Bay as the Vanga Blue Forest Project; also within the TBCA [

29]. These carbon projects are mitigating impacts of climate change, earning income for the local communities and also contributing to conservation of mangrove ecosystems.

4.3. Threats of mangroves within TBCA as reported

Like other areas in Kenya, mangroves within TBCA are threatened by a combination of human and natural factors. Major threats facing mangroves are overharvesting `of wood products for building and fuel. Poverty, economic pressure, poor governance, and lack of alternative livelihoods are identified as root causes of loss and degradation of mangroves in the area. Poor governance and law enforcement exhibit itself through mangrove land encroachment, dumping of solid waste, illegal mangrove harvesting activities. Cumulatively, these activities have led to the reported decline of mangrove forest cover and /or quality within TBCA [

19].

Climate change mediates threats such drought, flooding, soil erosion, and sedimentation which have negative impacts on mangroves in the study sites. The 1997/8 El Niño rains that hit most parts of the country resulted in heavy sedimentation and prolonged water stagnation which led to widespread mangrove die-backs in Gazi Bay among other mangrove sites along the Kenya coast [

17]. This process also caused shifts in species dominance. Sedimentation in the study sites is attributed to upstream activities such as damming of the river supplying sediments and freshwater downstream. Damming of the river Mkurumudzi, for instance, has affected sediment balance of the estuary in Gazi Bay leading to death of mangroves (

ibid.). Predicted sea-level rise associated with climate change [

48] is expected to accelerate loss and degradation of mangroves within TBCA. For instance, accelerated Sea Level Rise is projected to marginally outpace the net mangrove surface elevation in Vanga which would have a negative impact on mangroves of Vanga area.[

49] Other threats such as oil spills, plant parasites/woodborers have been documented in the area [

17], however, they were not mentioned in the workshop, most probably because they go unnoticed.

The numerous products and services derived from mangrove forests and the frequency of their extraction are a clear indication of their importance to the communities within TBCA (here reported for Kenya). Lack of access, therefore, results to increased illegal activities and degradation of the forest jeopardizing future provision of products and services.

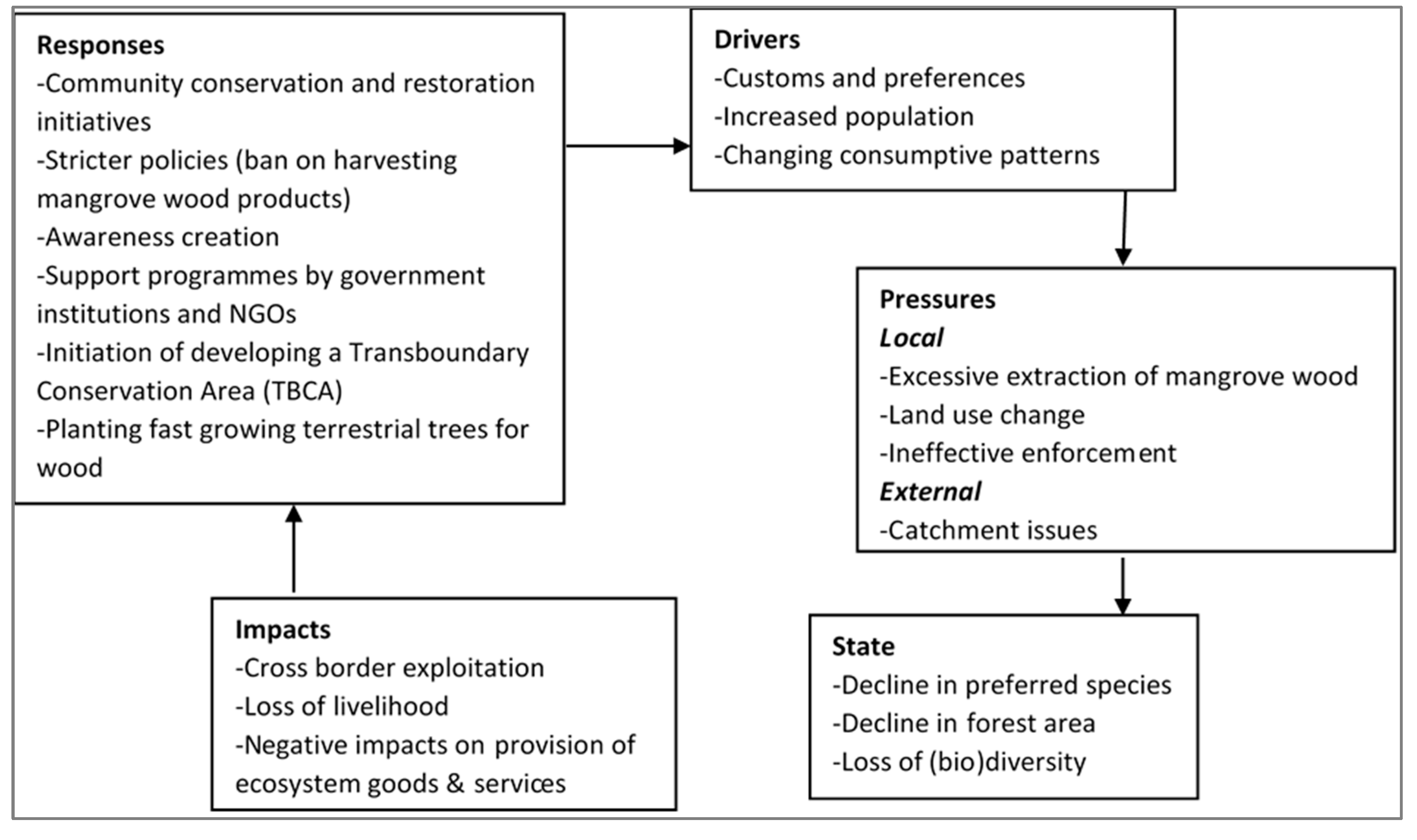

Figure 6.

DPSIR type scheme for TBCA (Kenya).

Figure 6.

DPSIR type scheme for TBCA (Kenya).

Figure 7.

Trends in the harvest of mangrove wood products Source: KFS records.

Figure 7.

Trends in the harvest of mangrove wood products Source: KFS records.

5. Conclusions

The numerous products derived from the mangrove forests, services provided by these ecosystems and the frequency of their extraction together are a clear indication of their importance to the communities within the Kenya-Tanzania TBCA. These products are vital for subsistence use and in meeting the sources of daily nutrition to the local communities. The products are also preferred because they are perceived to be more affordable and available compared to other alternatives, since they are often gotten for free from the mangroves.

Mangroves within Kenya’s side of the TBCA are characterized by mixed management systems. The forest within Gazi Bay enjoys a semi-access status following enhanced community-based mangrove management. Here, the sale of mangrove carbon offset credits on the voluntary market spearheaded through the Mikoko Pamoja has enabled communities to gain from conservation and restoration efforts. This is not the case in Vanga where open-access practices are the norm without community surveillance. Individuals enter the forest and extract construction poles and firewood illegally. . With the expansion of Mikoko Pamoja activities in Vanga, this approach is beginning to change for improved mangrove management in the area.

The TBCA (Kenyan part) is characterized by both sustainable and unsustainable resource use patterns. Unsustainable patterns are as a result of lack of access to the resource due to restrictions, personal preferences, lack of alternatives as well as cultural influences and practices. On the other hand, awareness raising, capacity building, provision of alternative source of wood products,as well as policies which regulate resource and enforcement of regulations have contributed to sustainable resource use patterns. Similar to other sites in Kenya there is preference of certain mangrove species and utilization classes within TBCA. Of the mangrove species, Rhizophora mucronata and Ceriops tagal are the preferred species for building and construction.

Mangroves in the TBCA are majorly threatened by illegal extraction of wood products. There is need for management interventions to regulate the removal of mangrove wood products for their sustainability. Development and implementation of mangrove harvesting plans will assist in guiding mangrove exploitation while planting of fast-growing terrestrial trees in community lands would provide alternative sources of wood products. There is a need to address the problems of open access through capacity building, education and awareness raising, as well as introduction of alternative livelihood options and acceptable and affordable goods for mangrove products to the communities in the area.

To further prepare for the projected TBCA, a similar research programme must be initiated at the Tanzanian side of the TBCA area, particularly because management entailing access for consumptive resource use must be coordinated between both countries within TBCA to overcome leakage of non-sustainable practices. The development of TBCA offers a prime opportunity to better manage and protect shared mangrove resources without jeopardizing livelihood, culture and well-being of communities depending on them, but it demands both research, continued monitoring and better (international) institutional coordination.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Figure S1: title; Table S1: title; Video S1: title.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: A.W.K., H.S., N.K., and J.G.K; MethodologyA.W.K J.H; Original draft preparation, A.W.K and J.G.K ; writing—review and editing, A.W.K., H.S., J.H., N.K and J.G.K supervision, H.S and J.G.K.; project administration; KVP; funding acquisition, J.G.K, KVP and N.K (promoter Trans-Coast project). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Trans-Coast project, grant number ZEIN2016PR425 by the Flemish Interuniversity Council VLIR-UOS and the APC was funded by the Pew Charitable Trust’s Contract: 00032875

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by Ethical Review Committee (ERC) of PWANI UNIVERSITY (Reference no ERC/MA/010/2019) and Date of approval 09/10/2020.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

My gratitude goes to the KMFRI staff and interns particularly the late Dr. Caroline Wanjiru, Nicolas Karani, Samson Obiene and Agnes Mukami for their support during my research work particularly in data collection. I am also grateful to my fellow students from Pwani University specifically Timothy Musa for the assistance they accorded me at the University. My appreciation also goes to the respondents who willingly provided me with the information needed to complete the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest

References

- Giri, C., Recent advancement in mangrove forests mapping and monitoring of the world using earth observation satellite data. 2021, MDPI. p. 563. [CrossRef]

- Barbier, E.B., Hacker, S.D., Kennedy, C., Koch, E.W., Stier, A.C. and Silliman, B.R.,, The value of estuarine and coastal ecosystem services Ecological monographs, 2011. 81(2), pp.169-193. [CrossRef]

- Huxham, M., A. Dencer-Brown, K. Diele, K. Kathiresan, I. Nagelkerken, and C. Wanjiru, Mangroves and people: local ecosystem services in a changing climate, in Mangrove Ecosystems: A Global Biogeographic Perspective: Structure, Function, and Services. 2017. p. 245-274.

- Valiela, I., Bowen, J.L. and York, J.K.,, Mangrove Forests: One of the World's Threatened Major Tropical Environments: At least 35% of the area of mangrove forests has been lost in the past two decades, losses that exceed those for tropical rain forests and coral reefs, two other well-known threatened environments Bioscience, 2001. 51(10), pp.807-815. [CrossRef]

- Giri, C., Ochieng, E., Tieszen, L.L., Zhu, Z., Singh, A., Loveland, T., Masek, J. and Duke, N.,, Status and distribution of mangrove forests of the world using earth observation satellite data. . Global Ecology and Biogeography, 2011. 20(1), pp.154-159. [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, L., D. Lagomasino, N. Thomas, and T. Fatoyinbo, Global declines in human-driven mangrove loss. Global change biology, 2020. 26(10): p. 5844-5855. [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, S.E. and D. Casey, Creation of a high spatio-temporal resolution global database of continuous mangrove forest cover for the 21st century (CGMFC-21). Global Ecology and Biogeography, 2016. 25(6): p. 729-738. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, N., P. Bunting, R. Lucas, A. Hardy, A. Rosenqvist, and T. Fatoyinbo, Mapping mangrove extent and change: A globally applicable approach. Remote Sensing, 2018. 10(9): p. 1466. [CrossRef]

- Bunting, P., Rosenqvist, A., Lucas, R.M., Rebelo, L.M., Hilarides, L., Thomas, N., Hardy, A., Itoh, T., Shimada, M. and Finlayson, C.M.,, The global mangrove watch—a new 2010 global baseline of mangrove extent. Remote Sensing, 2018. 10(10), p.1669. [CrossRef]

- Spalding, M. World atlas of mangroves; Routledge, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP-WCMC, The Importance of Mangroves to People: A Call to Action. 2014, United Nations Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre.

- Katsanevakis, S., Levin, N., Coll, M., Giakoumi, S., Shkedi, D., Mackelworth, P., Levy, R., Velegrakis, A., Koutsoubas, D., Caric, H. and Brokovich, E.,, Marine conservation challenges in an era of economic crisis and geopolitical instability: the case of the Mediterranean Sea Marine Policy, 2015. 51: p. pp.31-39. [CrossRef]

- Vosooghi, S., Panic-based overfishing in transboundary fisheries. Environmental and Resource Economics, , 2019. 73(4): p. pp.1287-1313. [CrossRef]

- Mason, N., Ward, M., Watson, J.E., Venter, O. and Runting, R.K.,. Global opportunities and challenges for transboundary conservation. . Nature ecology & evolution, , 2020. 4(5): p. pp.694-701. [CrossRef]

- Tuda, A.O., Kark, S. and Newton, A., , Polycentricity and adaptive governance of transboundary marine socio-ecological systems. Ocean & Coastal Management, 200, p.105412., 2021. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J., D.L. Yong, C.-Y. Choi, and L. Gibson, Transboundary frontiers: an emerging priority for biodiversity conservation. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 2020. 35(8): p. 679-690. [CrossRef]

- GoK, National mangrove ecosystem management plan. 2017: Nairobi, Kenya.

- Tanzania, M.P. and R. Unit, A Proposed Marine Transboundary Conservation Area Between Kenya and Tanzania. 2017.

- Mungai, F., J. Kairo, J. Mironga, B. Kirui, M. Mangora, and N. Koedam, Mangrove cover and cover change analysis in the transboundary area of Kenya and Tanzania during 1986–2016. Journal of the Indian Ocean Region, 2019. 15(2): p. 157-176. [CrossRef]

- Hagger, V., T.A. Worthington, C.E. Lovelock, M.F. Adame, T. Amano, B.M. Brown, D.A. Friess, E. Landis, P.J. Mumby, and T.H. Morrison, Drivers of global mangrove loss and gain in social-ecological systems. Nature Communications, 2022. 13(1): p. 6373. [CrossRef]

- FAO, Status and Trends in Mangrove Area Extend Worldwide. Working Paper No. 64. Forest Resource Division.” 64, no. 4: 367–79. 2005.

- GOK, Forest Conservation and Management Act. 2016.

- Mbuvi, M., A. Makee, and K. Mwenndwa, The Status of Mangrove Exploitation and Trade along the Kenyan Coastline. 2003.

- Riungu, P.M., J.M. Nyaga, M.N. Githaiga, and J.G. Kairo, Value chain and sustainability of mangrove wood harvesting in Lamu, Kenya. Trees, Forests and People, 2022. 9: p. 100322. [CrossRef]

- Tanzania, J.y.M.w., Mwongozo wa Uvunaji Endelevu na Biashara ya Mazao ya Misitu yanayovunwa katika miditu ya asili,, W.y.M.n. Utalii, Editor. 2017, Idara ya Misitu na Nyuki.

- Slobodian, L.N., Badoz, L., eds Tangled roots and changing tides: mangrove governance for conservation and.

-

sustainable use. . 2019. xii+280pp.

- Mshale, B., M. Senga, and E. Mwangi, Governing mangroves: unique challenges for managing Tanzania's coastal forests. 2017.

- Nyangoko, B.P., H. Berg, M.M. Mangora, M. Gullström, and M.S. Shalli, Community perceptions of mangrove ecosystem services and their determinants in the Rufiji Delta, Tanzania. Sustainability, 2020. 13(1): p. 63. [CrossRef]

- Plan Vivo. Vanga Blue Forest project Project Design Document 2019 14TH JULY 2022]. Available online: https://www.planvivo.org/Handlers/Download.ashx?IDMF=aae86576-2a6e-4eab-ac62-8f47dbf4b881.

-

Vanga, Jimbo and Kiwegu Participatory Mangrove Forest Management Plan (2019-2023). 2019.

- Mugenda, O.M. and A.G. Mugenda, Research methods: Quantitative and qualitative approaches. 1999: Acts press.

- Hugé, J. and N. Mukherjee, The nominal group technique in ecology & conservation: Application and challenges. Methods in ecology and evolution, 2018. 9(1): p. 33-41. [CrossRef]

- Dahdouh-Guebas, F., C. Mathenge, J. Kairo, and N. Koedam, Utilization of mangrove wood products around Mida Creek (Kenya) amongst subsistence and commercial users. Economic Botany, 2000: p. 513-527. [CrossRef]

- Hamza, A.J., L.S. Esteves, M. Cvitanović, and J.G. Kairo, Sustainable natural resource management must recognise community diversity. International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology, 2023: p. 1-18. [CrossRef]

- Gnansounou, S.C., M. Toyi, K.V. Salako, D.O. Ahossou, T.J.D. Akpona, R.C. Gbedomon, A.E. Assogbadjo, and R.G. Kakaï, Local uses of mangroves and perceived impacts of their degradation in Grand-Popo municipality, a hotspot of mangroves in Benin, West Africa. Trees, Forests and People, 2021. 4: p. 100080. [CrossRef]

- Islam, A.R., M.M. Hasan, M.T. Islam, and N. Tanaka, Ethnobotanical study of plants used by the Munda ethnic group living around the Sundarbans, the world's largest mangrove forest in southwestern Bangladesh. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 2022. 285: p. 114853. [CrossRef]

- Walters, B.B., P. Rönnbäck, J.M. Kovacs, B. Crona, S.A. Hussain, R. Badola, J.H. Primavera, E. Barbier, and F. Dahdouh-Guebas, Ethnobiology, socio-economics and management of mangrove forests: A review. Aquatic Botany, 2008. 89(2): p. 220-236. [CrossRef]

- Scales, I.R. and D.A. Friess, Patterns of mangrove forest disturbance and biomass removal due to small-scale harvesting in southwestern Madagascar. Wetlands Ecology and Management, 2019. 27: p. 609-625. [CrossRef]

- Kairo, J.G., F. Dahdouh-Guebas, P.O. Gwada, C. Ochieng, and N. Koedam, Regeneration status of mangrove forests in Mida Creek, Kenya: a compromised or secured future? AMBIO: A Journal of the Human Environment, 2002. 31(7): p. 562-568. [CrossRef]

- Okello, J.A., V.M. Alati, S. Kodikara, J. Kairo, F. Dahdouh-Guebas, and N. Koedam, The status of Mtwapa Creek mangroves as perceived by the local communities. Western Indian Ocean Journal of Marine Science, 2019. 18(1): p. 67-81. [CrossRef]

- Rasquinha, D.N. and D.R. Mishra, Impact of wood harvesting on mangrove forest structure, composition and biomass dynamics in India. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 2021. 248: p. 106974. [CrossRef]

- Blanco, J.F., E. Estrada, L.F. Ortiz, and L.E. Urrego, Ecosystem-wide impacts of deforestation in mangroves: the Urabá Gulf (Colombian Caribbean) case study. International Scholarly Research Notices, 2012. 2012. [CrossRef]

- Longonje, N.S. and R. Dave, Assessing ecosystem effects of small–scale cutting of Cameroon mangrove forests. Journal of Ecology and the Natural Environment, 2012. 4(5): p. 126-134. [CrossRef]

- Walters, B.B., Ecological effects of small-scale cutting of Philippine mangrove forests. Forest Ecology and Management, 2005. 206(1-3): p. 331-348. [CrossRef]

- Sillanpää, M., J. Vantellingen, and D.A. Friess, Vegetation regeneration in a sustainably harvested mangrove forest in West Papua, Indonesia. Forest Ecology and Management, 2017. 390: p. 137-146. [CrossRef]

- Wang’ondu, V.W., Muthumbi, A., Vanruesel, A., & Koedam, N., Phenology of mangroves and its implication on forest management: a case study of Mida Creek, Kenya. Western Indian Ocean Journal of Marine Science, 2017. 16(2), 41-51.

-

Plan Vivo. MIKOKO PAMOJA Mangrove conservation for community benefit 2020 [cited 2022 14th July 2022]. Available online: https://www.planvivo.org/Handlers/Download.ashx?IDMF=3faf7087-dec2-41ca-8a67-42a98e21c59d.

- IPCC, IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate, D.C.R. [H.-O. Pörtner, V. Masson-Delmotte, P. Zhai, M. Tignor, E. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Nicolai, A. Okem, J. Petzold, B. Rama, N.M. Weyer (eds.)], Editor. 2019.

- Kimeli, A.K., Sediment Dynamics in a Transboundary Mangrove Habitat: A Perspective of Sediment Sources and Sedimentation in the Vanga Estuary, Kenya. 2022, Universität Bremen.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).