Introduction

People get protection from Coronavirus infection, and consequent hospitalization and death if vaccinated [

1]. On 16

th January 2021, a vaccination drive started in India using the AstraZeneca made, Covishield and the indigenous vaccine Covaxin. Later on, other vaccines like Sputnik V and Corbevax were also approved for emergency use [

2].

The population with two vaccine doses showed 76 infected persons per 1000 person-months whereas the incidence rate was nine times higher in the unvaccinated counterparts. Population immunized with one dose showed 25 cases per 1000 person-months while 9 infected persons per 1000 person-months were seen in those who received two doses of vaccine [

3]. This shows taking both doses of vaccine is necessary to control the incidence rate of Corona.

Vaccine efficacy may dwindle slowly over time after the second dose of the vaccines [

4]. It is more in older people and a clinical risk group [

5,

6]. Earlier studies on the Covid-19 vaccine shows, that taking a booster dose after the primary vaccine course gives considerably more protection against the disease [

7,

8]. This shows that people need to take not only a second dose of their vaccine course but also a booster dose.

Vaccine rollout in India faced many practical problems like political polarization [

9], vaccine shortages [

10], confusion or misinformation [

11], problems with vaccine registrations, and availability [

12].

The reality of access to health care or immunization programs can be seen through vaccination coverage [

13]. Hesitancy towards the newly developed COVID-19 vaccines was a global phenomenon [

14]. Approximately eighteen systematic studies were carried out to understand the perception of Indian people toward the COVID-19 vaccine.

Most of these studies were pan-India studies carried out by online surveys [

15]. Few studies were carried out at the community level for specific states [

16]. There were a couple of studies focused on healthcare workers to understand their perception of the COVID-19 vaccine [

17].

Online surveys have their own set of limitations, inability to connect with people from remote areas [

18], high chances of survey fraud [

19,

20] sampling issues [

21,

22] response bias [

23,

24] survey fatigue [

25], increase in errors [

26], a large number of unanswered questions [

27], and difficult to interpret the sentiments behind answers [

28].

All the earlier studies carried out to understand the perception of people towards the COVID-19 vaccine are questionnaire-based online surveys which do not help to understand the exact action taken by people towards immunization. It is difficult to make out whether the person has taken primary and booster doses. In this study, the number of doses of the COVID-19 vaccine administered in the population will help us to understand the exact behavior of the people towards the vaccine.

All the earlier studies carried out on the Indian population to understand their perception towards the COVID-19 vaccine have shown varying degrees of hesitancy towards the vaccine. Considering the large population of the country, even if a small number of people are reluctant to vaccinate, it will still lead to millions of unvaccinated people. It remains unclear exactly how many individuals have taken their primary course and booster of vaccines in India.

Earlier studies in the Indian population were focused on the acceptance or hesitancy of the people towards vaccines. Here systematic study has been carried out to understand the attitude of people towards the primary dose, and booster dose of the COVID-19 vaccine. In this study, the number of doses administered in the population is used to understand the behavior of the people towards the COVID-19 vaccine which will give us a better idea than questionnaire-based surveys. Earlier studies were mostly regional or state-specific. In this paper, a nationwide study is carried out for every state and union territory. The study population here is not random but it is divided into subgroups like, above 18 years, 15-18 years, and 12-14 years for primary courses whereas they are broadly divided into 18-59 years and 60+, HCW, and FLW for a booster dose.

The data derived from this study will help in framing emergency guidelines to handle future threats; mainly in facilitating cross-country roll-out of resources. The results of this study will be of great help in the future emergency of COVID-19. The national-level and state-level analysis done here can be used to develop targeted behavior change communication campaigns.

Methods

Data Collection

The data up to 23rd December 2022 was considered for the current study as on 24th December 2022, the Ministry of Health & Family Welfare has implemented fresh guidelines for international arrivals. These new guidelines were implemented seeing the surge of COVID-19 cases in neighboring China.

For ease of analysis, the country is divided into seven main regions- 1)The northern region- six states- Himachal Pradesh, Punjab, Uttarakhand, Haryana, Delhi, and Uttar Pradesh; 2) the Southern region contains five states- Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala, Tamil Nadu, and Telangana; 3)Eastern region is consisting of the states of Bihar, Jharkhand, Odisha and West Bengal; 4)Western region states are Rajasthan, Maharashtra Gujarat and Goa; 5) Central region consists of two states- Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh; 6)North-East region includes-eight States viz. Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland, Sikkim, and Tripura; 7)Union territories-Andaman and Nicobar islands, Chandigarh, Dadra and Nagar Haveli, Daman and Diu, Lakshadweep, Puducherry, Ladakh and Jammu & Kashmir.

The population under the study is divided based on doses of vaccine administered. The population in which the first and second dose of vaccine is administered is divided into the sub-groups)18+ yrs, 2)15-18 yrs, 3)12-14 years. For the third or precautionary or booster dose, the population is divided into two sub-categories -1) 18-59 years and 2) Vulnerable population- 60+ years, Health Care Workers (HCW) and Front-Line Workers (FLW). The data for miscellaneous doses has been added in a separate table to avoid confusion during analysis.

The difference between the first dose and second dose of the COVID-19 vaccine administered in the population is calculated by simple mathematical operations. Total booster doses given to the 18-59 years population and vulnerable population are calculated by adding their values. The values obtained after calculations are rounded off to the nearest place value.

Results

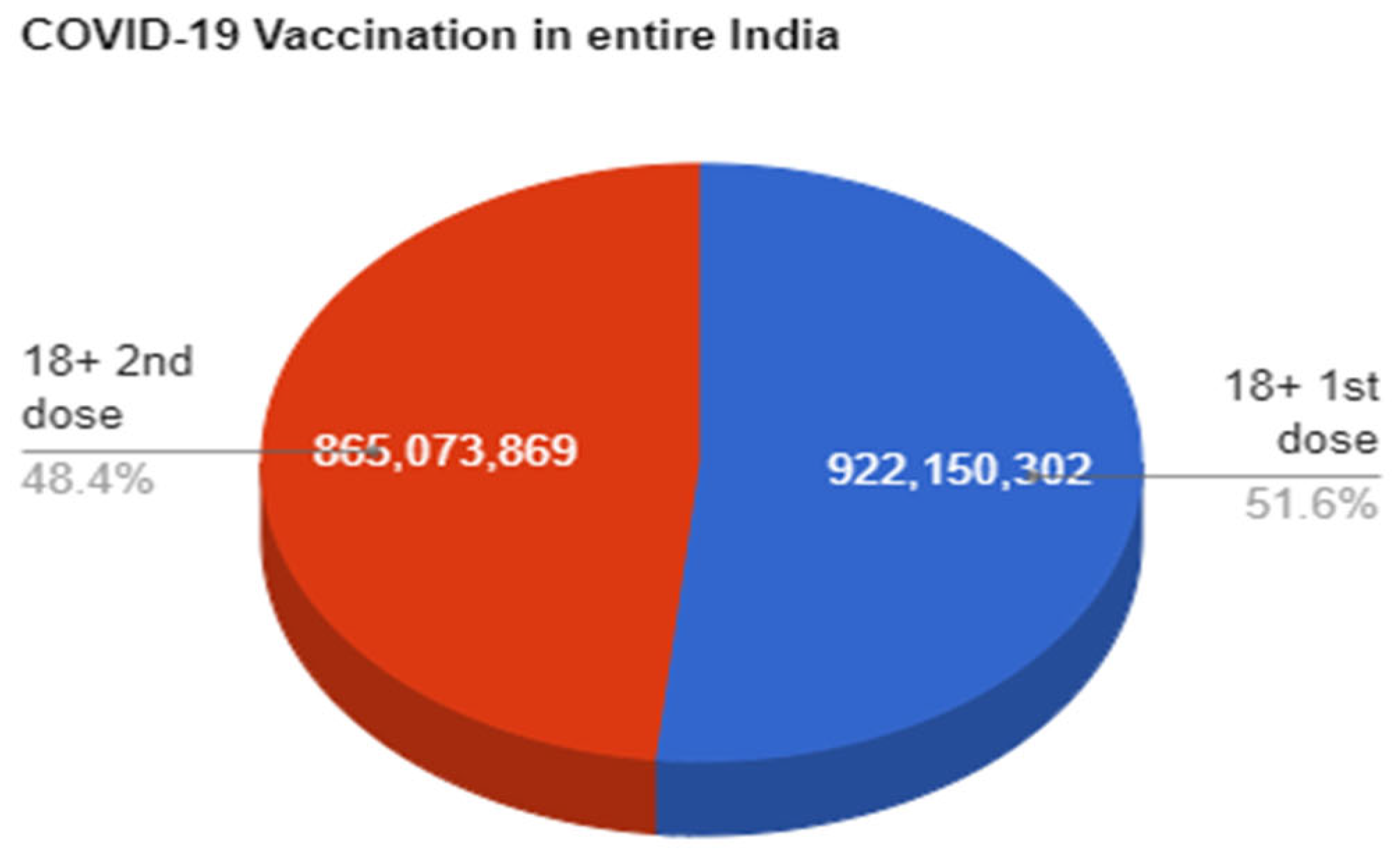

When the COVID-19 vaccine coverage data was analyzed at the country level, it showed that ~920 million doses had been administered in 18+ years age group as the first dose (Table-1). But out of this 920 million, only 870 million have taken the second dose (

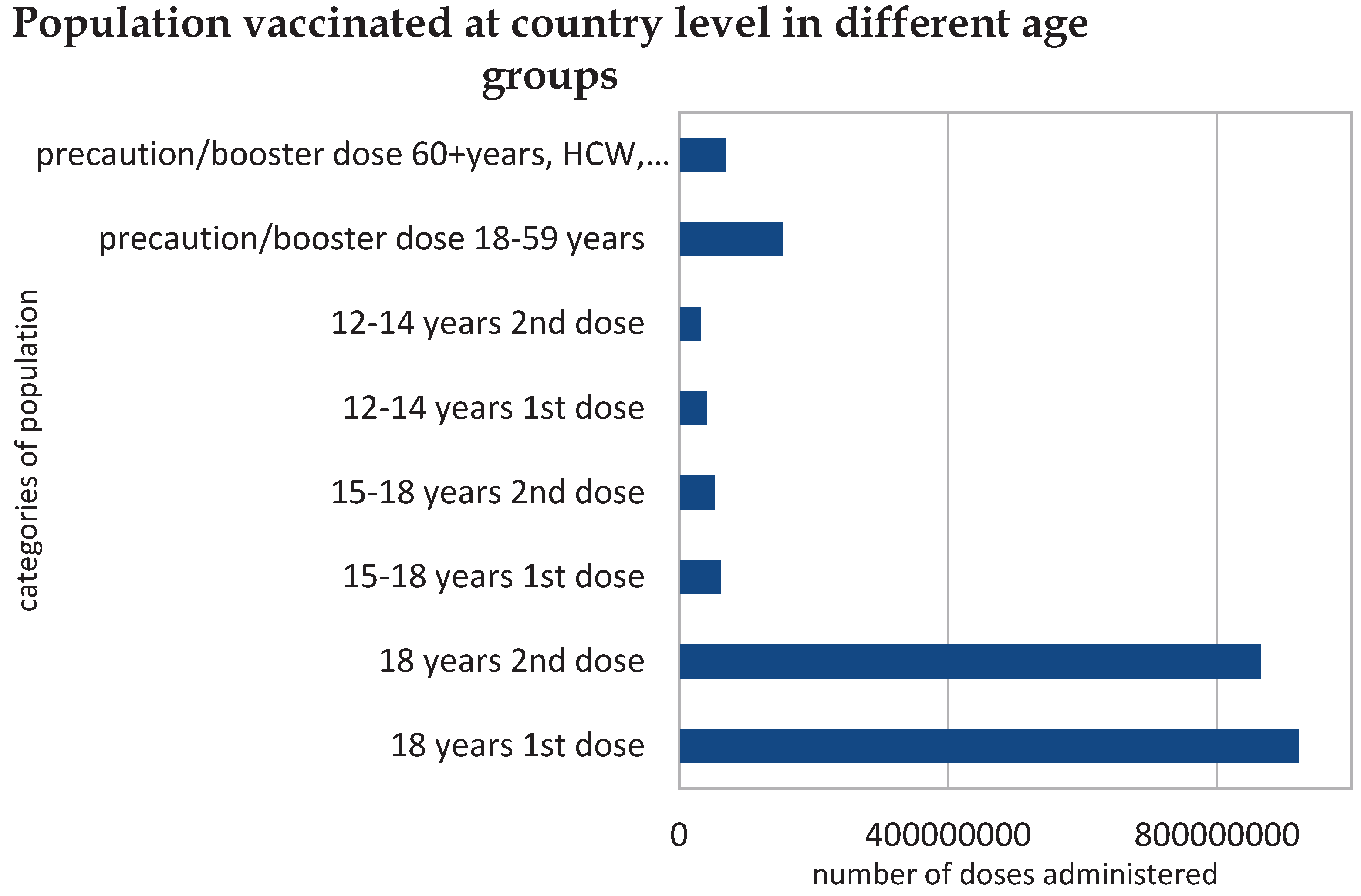

Figure 1). That means 60 million people have missed their second dose of the vaccine. The difference in first and second doses administered in the 15-18 years and 12-14 years age group categories has shown a difference of around 8.5 million and 8.8 million respectively.

The results for total booster doses administered in the population showed only 220 million as compared to ~920 million for the first dose of vaccine. Only 70 million booster doses were administered in vulnerable populations all over the country (

Figure 2).

When the vaccine coverage for the northern region of India is analyzed, the data entry error for 18+ population has been observed for Jammu and Kashmir. For these states, the number of second doses is more than the first one. Hence that reading was ignored. Out of 6 states of North India, Uttar Pradesh has administered the highest number (390 million) of total vaccines. Whereas the state of Himachal Pradesh has administered the lowest number of doses (15 million). In all the states of northern India, a considerable population in every age group has missed the second dose of vaccine. The highest number is seen in people of Uttar Pradesh (6.3 million) missed the second dose in the age group 18+, 0.9 million and 0.83 million missed their second dose in 15-18 years and 12-14 years respectively. These numbers are quite high if compared to the rest of the states of the northern region of India. The next state to Uttar Pradesh which missed the second dose in 18+ population is Haryana (3.2 million) followed by Punjab (2.8 million) and then Delhi (2.25 million). Uttarakhand (20 million) and Himachal Pradesh (15 million) have comparatively lower numbers for total doses administered as well as lower population (0.2 million per state) who missed the second dose of vaccine (Table-2).

When the data was analyzed for total booster doses administered in the population, Uttar Pradesh showed the highest number (45 million) in the northern region of India. But these doses are just one-third of the first dose. A more or less similar trend is noticed for the other states of the Northern region for booster doses. The highest number of booster doses in the vulnerable population (9.2 million) is seen in Uttar Pradesh only. This number is almost eight to nine times higher as compared to other states of north India.

In the southern region of India, a total of 491 million COVID-19 vaccine doses were administered (Table-3). For the states of Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka, the number of second doses administered in the age group 18+ population is more, hence considering it as a data error by MoHFW, these readings were ignored. In Kerala, a total 57 million doses were administered but 3.2 million in 18+ population, 0.36 million in 15-18 years and 0. 29 million in the 12-14 years population have missed the second dose of vaccine. A total of 3.06 million booster doses were administered in Kerala which is far less compared to the first dose of vaccine.

In Tamil Nādu, 127 million total vaccine doses were administered. 3.2 million people missed the second dose in the 18+ population. Whereas 0.4 million and 0.45 million people in the age group 15-18 years and 12-14 years have missed their second dose respectively. 9 million people in the 18+ population and vulnerable population have taken booster doses in Tamil Nādu.

In Telangana, a total of 77 million vaccine doses were administered. 29 million people in the 18+ population took the first dose but out of those who took the first dose, 0.55 million people missed their second dose. In the age group 15-18 years, 0.1 million people missed their second dose whereas 0.2 million missed the second dose in the 12-14 years of age group. In Telangana, the total booster doses administered were 13 million.

A total of 436 million COVID-19 vaccine doses were administered in the eastern region of India (Table-4). In Bihar and West Bengal, 155 million doses in each state were administered followed by Odisha (81 million) and Jharkhand (43 million). In Bihar and West Bengal, approximately 15 million booster doses in each state were administered followed by Odisha (13 million) and Jharkhand (1.95 million). In Bihar, 3.8 million, 0.89 million, and 0.88 million missed their second dose in the age group 18+, 15-18 years, and 12-14 years respectively.

In Jharkhand, 5.26 million, 0.49 million, and 0.44 million have missed the second dose in the age group 18+, 15-18 years, and 12-14 years respectively. In Odisha, the number who missed the second dose (1.5 million) is less as compared to the other three states of the region. In West Bengal, in contrast, 5.7 million people in the age group 18+ have missed their second dose. 0.56 million people in the age group 15-18 years and 12-14 years have missed their second dose of vaccine.

A total of 421 million vaccine doses have been administered in the western region of India (Table-5). The numbers of Gujarat for the second dose in the 18+ population are higher than the first dose. Considering it as an error, these figures are ignored. The highest doses in the western region 177 million were administered in the state of Maharashtra. It is followed by Gujarat (127 million) and then Rajasthan (115 million). Only 2.8 million doses were administered in Goa.

In Rajasthan, 51.1 million doses were administered as first dose but 4.59 million in 18+ population, 0.66 million in 15-18 years, and 0.84 million in 12-14 years missed their second dose. In Maharashtra, 13 million in 18+ population, 1.01 million in 15-18 years, and 1.02 million in 12-14 years have missed their second vaccine dose. In Goa, only 1.35 million people in the 18+ population took the first dose of the vaccine but 0.13 million missed their second dose. 7181 and 6626 respectively in the age group 15-18 years and 12-14 years missed the second dose. Only 0.13 million people took the booster dose in Goa.

The central region of India consists of Chhattisgarh and Madhya Pradesh where collectively 182 million doses were administered (Table-6). In Chhattisgarh (18 million) and in Madhya Pradesh (54 million) first doses were administered, out of which 0.4 million and 0.1 million people respectively missed their second doses of the COVID-19 vaccine. In Chhattisgarh, 0.18 million people in the age group 15-18 years and 0.32 million in 12-14 years have missed their second dose. In Madhya Pradesh, 0.7 million in 15-18 years and 0.71 million in 12-14 years have missed their second dose. In Chhattisgarh, 7.5 million people and in Madhya Pradesh, 13 million people were immunized with booster doses.

In the North-East region of India (Table-7), the highest COVID-19 vaccine doses (50 million) were administered in Assam whereas the lowest doses (1.36 million) were administered in Sikkim. Out of all the eight states except Sikkim, populations ranging from 0.11 million to 2.0 million have missed their second dose in the 18+ population. Assam is the state that has missed the highest number of second doses in the age group 15-18 years (0.29 million) and 12-14 years (0.39 million).

Among India's seven Union Territories, a data entry error has been noticed for the Andaman & Nicobar Islands. The highest number of vaccine doses were administered in Chandigarh (2.28 million) followed by Puducherry (2.27 million). The lowest numbers were administered in Lakshadweep (0.14 million). The highest booster doses (0.4 million) were administered in the population of Puducherry out of all the Union territories of India (Table 8). A total of 5295713 miscellaneous doses were given in the entire country which was used only for country-level analysis and not for regional-level analysis (Table-9).

Discussion

In the present analysis, we first explored the number of vaccine doses administered in the population at the country level as primary courses in the age groups, 18+ population, 15-18 years population, and 12-14 years population. A significant number of the population missed the second dose of the COVID-19 vaccine administered in all three age groups. Similar results were noticed in the other studies where people who started the primary series were initially positive towards vaccination but eventually either delayed or failed to complete the said course [

29].

Postponing or suspending the prescribed vaccine doses can hinder the government’s public healthcare strategy to control COVID-19 spread [

30,

31,

32]. Data on the population who have missed or delayed their vaccination is crucial to frame strategies to tackle the diffidence toward vaccines.

When the data for booster doses administered at the national level was studied, a considerable number of people from vulnerable populations like the 60+ population, Health Care Workers, and frontline workers have not taken booster doses. The total booster doses in the overall population of 18+ and vulnerable populations are far lower as compared to the first vaccine dose (Table 1).

Compared with booster dose recipients in 18–59 years of age, vulnerable people like recipients >60 years of age, HCW, and FLW might not have ignored the second dose. People above sixty years of age have comparably more time, as well as they have been given priority for vaccine availability by the Government. The high probability of getting the infection in older people might have forced them to complete the immunization schedule [

33]. The earlier study proves that fully or partially vaccinated healthcare workers have milder infections and less hospitalization when compared to their unvaccinated counterparts [

34].

The findings of this study clearly show that people in any age group including vulnerable groups are reluctant to take a second dose as well as a booster dose of COVID-19. This trend is worrisome especially for the vulnerable population as there is clear evidence from the studies of Horne et. al., 2022 and Nanishi et.al, 2022 that waning vaccine effectiveness is more in older people and a clinical risk group. Andrews et.al, 2022 and Shekhar et. al., 2021 have proved that booster doses give substantially increased immunity against disease.

In the region-wise analysis, the trend in northern, southern, western, eastern, central, and northeast regions of India matches with a national trend of vaccine coverage. Where a substantial population has missed the second dose in all three age groups. At the same time, a substantial population has not taken their booster doses, including vulnerable populations.

In Uttar Pradesh under the northern region, the highest number of total vaccine doses as well as booster doses were administered. But this is the same state which has shown the highest population in the region which missed the second dose of vaccine. In Uttar Pradesh, two-thirds population out of those who took the first dose have missed the booster dose. The reason behind the highest number of vaccine doses administered in Uttar Pradesh may be that it is the country's highest populated state [

35]. Another possible reason might be, that this is one of the severely affected states during the second wave of COVID-19 along with nine other states of the country. The Government decided to improve the speed of vaccination seeing the increasing number of new cases [

36].

The results for Delhi, being the national capital were, expected to be better, but the large population there too missed their second and booster dose. This result might be supported by the study where 39.1% of the population of Delhi has shown concern about the safety of the vaccine [

37]. Himachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand have shown the lowest number of doses administered compared to the other states of the northern region of the country. The possible reason behind the small number might be the small population of these states.

Seeing the geographical difficulties of the North-East region of the country, accessibility of the vaccine to the people of this area was an issue, which makes the data of the region important. Here delivering the vaccine was a bigger challenge for the government than the perception of the people towards the COVID-19 vaccine. Similar challenges were also seen for the Union territory of Andaman & Nicobar Islands. However, analysis of this study shows that enough total vaccine doses were administered throughout the Northeast region as well as in challenging Union Territories. The reason behind this might be

the Indian Council of Medical Research’s drone (i-Drone) response and outreach in North East delivered doses of the COVID-19 vaccine [

38].

Earlier studies support our findings where when compared with first-dose, recipients were more likely to have uncertainty about the next dose [

39]. Our research findings are also consistent with the Government of India’s Economic Survey, 2023. As per the survey report, till December 2022, overall, 91.65 l million people were vaccinated with the first dose and 76.565 million with the second dose [

40]. This report clearly shows when compared with 1

st dose, a considerable number of people have not taken the 2

nd dose. This gap might be due to various factors. Fear of side effects is one of the main reasons observed for missing second and recall doses [

41]. Another reason behind this behavior might be the reluctance to take leave from work for vaccination and post-vaccination side effects [

42,

43].

Earlier studies showed that COVID-19 vaccination was more prevalent in urban parts of the country than the rural ones [

44]. A similar possibility might be there in the case of the Indian scenario. Also, these observations of the present study emphasize the need to understand the mental blocks of the people towards immunization.

One peculiar problem of data has been noticed for some of the states where the number of second doses is higher than the first one. There is a possibility of human error during data entry at MoHFW website. Human errors like this can impact research output negatively [

45]. Hence the data for these states is mentioned but not considered for the conclusion. This needs further correction by MoHFW.

This is a systematic study based on data on the total number of vaccines administered at the national, regional, and state levels. This study highlights the number of people who took their first dose of the vaccine but missed their second dose in three age groups, 18+, 15-18 years, and 12-14 years. This also gives the idea of how many people have taken booster doses in the 18-59-year-old population and vulnerable population. But there is a need for further research to understand, out of the total population of the state, how many people have not taken even a single dose of COVID-19 vaccine.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

This study has made considerable contributions to the literature if considering the future threats of pandemics. This gives geographical zone-wise insight into the approach of people which can help in the future crisis for mobilization of resources. But there are some limitations also. These limitations can be addressed in future research. First, the limitations which are related to any secondary data are also related to this data. Human errors while reporting and feeding the data are a common challenge.

Conclusions and Policy Implications

The national, regional, and state-level analyses of COVID-19 vaccine coverage have shown that a substantial population has missed the second dose of the vaccine. Even for the states where this number is smallest, that number is in thousands. In every state, 50-75% of the population has not taken booster doses out of those who took the first dose of the primary series. One of the limitations we noticed here is discrepancies in data for some states. There is a need for further research to know how many people have not even taken a single dose of vaccine. The policy level changes are needed to cover the entire population of the country for at least a single dose and vulnerable populations for booster doses of the COVID-19 vaccine.

Research Highlights:

The World Health Organization (WHO) highlights the threat of more frequent pandemics in the future. There is a need to learn about health system preparedness from past experiences. This study highlights the patient's behavior towards completion of the vaccine course.

Managing and analyzing health data or information like this can help to innovate and build the capacity of health systems. Healthcare practitioners must strive to create high-quality databases by collecting and saving information about patient behavior towards not only vaccines but also about major medical aspects which can allow reliable research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, analysis, and investigation, writing, reviewing & editing of the draft - J. S 2) Supervision, statistical analysis, original draft preparation/writing, review, and editing- C. S. All authors have agreed to the submission of this manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study data is taken from the portal of the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. The study is based on secondary data that are available in the public domain and hence there is no ethical approval required for this study.

Conflicts of Interest/ Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Cabezas C, Coma E, Mora-Fernandez N, Li X, Martinez-Marcos M, Fina F et al. Associations of BNT162b2 vaccination with SARS-CoV-2 infection and hospital admission and death with COVID-19 in nursing homes and healthcare workers in Catalonia: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2021;374:n1868. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VaccinationMoHFWhttps:. Available from: http://www.mohfw.gov.in/pdf/COVIDVaccinationBooklet14SEP.pdf.

- Tsundue T, Namdon T, Tsewang T, Topgyal S, Dolma T, Lhadon D, et al. First and second doses of Covishield vaccine provided high level of protection against SARS-CoV-2 infection in highly transmissible settings: results from a prospective cohort of participants residing in congregate facilities in India. BMJ Glob Health. 2022;7(5):e008271. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levin, E.G.; Lustig, Y.; Cohen, C.; Fluss, R.; Indenbaum, V.; Amit, S.; Doolman, R.; Asraf, K.; Mendelson, E.; Ziv, A.; et al. Waning Immune Humoral Response to BNT162b2 Covid-19 Vaccine over 6 Months. New Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, e84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horne, E.M.F.; Hulme, W.J.; Keogh, R.H.; Palmer, T.M.; Williamson, E.J.; Parker, E.P.K.; Green, A.; Walker, V.; Walker, A.J.; Curtis, H.; et al. Waning effectiveness of BNT162b2 and ChAdOx1 covid-19 vaccines over six months since second dose: OpenSAFELY cohort study using linked electronic health records. BMJ 2022, 378, e071249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanishi, E.; Levy, O.; Ozonoff, A. Waning effectiveness of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines in older adults: a rapid review. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2022, 18, 2045857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekhar, R.; Garg, I.; Pal, S.; Kottewar, S.; Sheikh, A.B. COVID-19 Vaccine Booster: To Boost or Not to Boost. Infect. Dis. Rep. 2021, 13, 924–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, N.; Stowe, J.; Kirsebom, F.; Toffa, S.; Sachdeva, R.; Gower, C.; Ramsay, M.; Bernal, J.L. Effectiveness of COVID-19 booster vaccines against COVID-19-related symptoms, hospitalization and death in England. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 831–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, J. Is lockdown an effective strategy to control infections like COVID-19? Analysis. 2022.

- Ravi, D. COVID-19 in India vaccine shortages are leading to discrimination in access. BMJ. 2021:1-5.

- Vaghela, G.; Narain, K.; Isa, M.A.; Kanisetti, V.; Ahmadi, A.; Lucero-Prisno, D.E. World's largest vaccination drive in India: Challenges and recommendations. Heal. Sci. Rep. 2021, 4, e355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakraborty, C.; Sharma, A.R.; Bhattacharya, M.; Agoramoorthy, G.; Lee, S.-S. The current second wave and COVID-19 vaccination status in India. Brain, Behav. Immun. 2021, 96, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cutts FT, Claquin P, Danovaro-Holliday MC, Rhoda DA. Monitoring vaccination coverage: defining the role of surveys. Vaccine. 2016;34(35):4103-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sallam, M. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Worldwide: A Concise Systematic Review of Vaccine Acceptance Rates. Vaccines 2021, 9, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, U.; Kishore, J.; Ghai, G.; Heena; Kumar, P. Perception and attitude towards COVID-19 vaccination: A preliminary online survey from India. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2021, 10, 3116–3121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danabal, K.G.M.; Magesh, S.S.; Saravanan, S.; Gopichandran, V. Attitude towards COVID 19 vaccines and vaccine hesitancy in urban and rural communities in Tamil Nadu, India – a community based survey. BMC Heal. Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassi, S.; Bahl, D.; Thapliyal, N.; Maity, H.; Marathe, S.D.; Prakshale, B.B.; Shah, V.G.; Salunke, S.R.; Arora, M. COVID-19 vaccine knowledge, attitudes, perceptions and uptake among healthcare workers of Pune district, Maharashtra. J. Glob. Heal. Rep. 2022, 6, e2022041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveri, S.; Lanzoni, L.; Petrocchi, S.; Janssens, R.; Schoefs, E.; Huys, I.; Smith, M.Y.; Smith, I.P.; Veldwijk, J.; de Wit, G.A.; et al. Opportunities and Challenges of Web-Based and Remotely Administered Surveys for Patient Preference Studies in a Vulnerable Population. Patient Preference Adherence 2021, ume 15, 2509–2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teitcher JE, Bockting WO, Bauermeister JA, Hoefer CJ, Miner MH, Klitzman RL. Detecting, preventing, and responding to ”fraudsters” in internet research: ethics and tradeoffs. J Law Med Ethics. 2015 Spring;43(1):116-33. [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Sagar, R. A critical look at online survey or questionnaire-based research studies during COVID-19. Asian J. Psychiatry 2021, 65, 102850–102850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, D.; Nonnecke, B.; Preece, J. Electronic Survey Methodology: A Case Study in Reaching Hard-to-Involve Internet Users. Int. J. Human–Computer Interact. 2003, 16, 185–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, P.; Rainie, L.; Jones, S. Days and Nights on the Internet: The Impact of a Diffusing Technology. Am. Behav. Sci. 2001, 45, 383–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, C. The Limitations of Online Surveys. Indian J. Psychol. Med. 2020, 42, 575–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menachemi, N. Assessing response bias in a web survey at a university faculty. Evaluation Res. Educ. 2011, 24, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Koning, R.; Egiz, A.; Kotecha, J.; Ciuculete, A.C.; Ooi, S.Z.Y.; Bankole, N.D.A.; Erhabor, J.; Higginbotham, G.; Khan, M.; Dalle, D.U.; et al. Survey Fatigue During the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Analysis of Neurosurgery Survey Response Rates. Front. Surg. 2021, 8, 690680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, V.C.; Kuriwaki, S.; Isakov, M.; Sejdinovic, D.; Meng, X.-L.; Flaxman, S. Unrepresentative big surveys significantly overestimated US vaccine uptake. Nature 2021, 600, 695–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfreda, K.L.; Bosnjak, M.; Berzelak, J.; Haas, I.; Vehovar, V. Web Surveys versus other Survey Modes: A Meta-Analysis Comparing Response Rates. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2008, 50, 79–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einola, K.; Alvesson, M. Behind the Numbers: Questioning Questionnaires. J. Manag. Inq. 2020, 30, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anders, C. 15 million people in the U.S. have missed their second dose of the coronavirus vaccine, CDC says [cited Jan 30 2022]. Available from: https://www.washingtonpost.com/health/2021/07/02/missed-second-dose-covid19-vaccine.

- Bradley T, Grundberg E, Selvarangan R, LeMaster C, Fraley E, Banerjee D, et al. Antibody responses after a single dose of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(20):1959-61. [CrossRef]

- Bar-On, Y.M.; Goldberg, Y.; Mandel, M.; Bodenheimer, O.; Freedman, L.; Kalkstein, N.; Mizrahi, B.; Alroy-Preis, S.; Ash, N.; Milo, R.; et al. Protection of BNT162b2 Vaccine Booster against Covid-19 in Israel. New Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 1393–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doria-Rose, N.; Suthar, M.S.; Makowski, M.; O’Connell, S.; McDermott, A.B.; Flach, B.; Ledgerwood, J.E.; Mascola, J.R.; Graham, B.S.; Lin, B.C.; et al. Antibody Persistence through 6 Months after the Second Dose of mRNA-1273 Vaccine for Covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 2259–2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barek, A.; Aziz, A.; Islam, M.S. Impact of age, sex, comorbidities and clinical symptoms on the severity of COVID-19 cases: A meta-analysis with 55 studies and 10014 cases. Heliyon 2020, 6, e05684–e05684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamil; Bhattacharya, P. K.; Barman, B.; Lynrah, K.G.; Lyngdoh, M.; Tiewsoh, I.; Gupta, A.; Mandal, A.; Sahoo, D.P.; Sathees, V. COVID-19 Vaccination Status Among Healthcare Workers and Its Effect on Disease Manifestations: A Study From Northeast India. Cureus 2022, 14, e25159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, A.K. Population and development in Uttar Pradesh: a district level analysis using census data. Int. J. Heal. 2015, 3, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juyal, D.; Pal, S.; Thaledi, S.; Pandey, H. COVID-19: The vaccination drive in India and the Peltzman effect. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2021, 10, 3945–3947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.; Sharma, A. Perceptions and beliefs on vaccination for COVID-19 in Delhi: A cross-sectional study. Indian J. Med Spéc. 2021, 12, 151–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. India deploys drones to deliver COVID-19 vaccines; 2021.

- Meng, L.; Murthy, N.C.; Murthy, B.P.; Zell, E.; Saelee, R.; Irving, M.; Fast, H.E.; Roman, P.C.; Schiller, A.; Shaw, L.; et al. Factors Associated with Delayed or Missed Second-Dose mRNA COVID-19 Vaccination among Persons >12 Years of Age, United States. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2022, 28, 1633–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of India. p. 2022-23; 2023. Economic Survey. Available from: https://www.indiabudget.gov.

- Ismail, L. Doctors say some are opting out of second vaccine dose in fear of side effects [cited Mar 4 2022]. Available from: https://www.newschannel5.com/news/doctors-say-some-are-opting-out-of-second-vaccine-dose-in-fear-of-side-effects.

- Goldman, N.; Pebley, A.R.; Lee, K.; Andrasfay, T.; Pratt, B. Racial and ethnic differentials in COVID-19-related job exposures by occupational standing in the US. PLOS ONE 2021, 16, e0256085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamel L, Lopes L, Sparks G, Kirzinger A, Kearney A, Strokes M, et al. Kaiser Family Foundation. KFF COVID-19 vaccine monitor; 21 [cited Jan 30 2022]. Available from: https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-COVID-19/poll-finding/kff-COVID-19-vaccine-monitor-october-2021. 20 October.

- Saelee R, Zell E, Murthy BP, Castro-Roman P, Fast H, Meng L, et al. Disparities in COVID-19 vaccination coverage between urban and rural counties—United States, , 2020-January 31, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71(9):335-40. 14 December. [CrossRef]

- Barchard, K.A.; Pace, L.A. Preventing human error: The impact of data entry methods on data accuracy and statistical results. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2011, 27, 1834–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).