The onset of the COVID-19 crisis triggered immediate and prolonged concerns that disrupted individuals' coping mechanisms (Brenning et al., 2022). In the initial stages of the crisis, widespread apprehensions focused on health, the availability of medical supplies, and food security (Carroll et al., 2020; Barman et al., 2021). However, as time unfolded, other worries emerged, encompassing financial instability and uncertainties regarding the duration and unpredictability of the crisis (Kämpfen et al., 2020). The persistent nature of these stressors hindered personal growth and effective coping for some individuals, resulting in a wide spectrum of responses to the crisis.

To examine the factors conducive to personal growth and well-being during these challenging times, this research adopts a Self-Determination Theory (SDT) framework (Ryan & Deci, 2017; Ryan et al., 2021). SDT provides a multidimensional understanding of human functioning, elucidating how individuals interpret and shape their experiences while integrating and regulating their values, behaviors, and emotions (Ryan et al., 2021). The theory distinguishes between autonomous and controlled forms of motivation, emphasizing the advantages of autonomy for internal harmony, flexibility, healthy development, and effective self-regulation (Ryan, 2005; Ryan et al., 2016; Vansteenkiste & Ryan, 2013). Feeling autonomous in life is deemed a fundamental psychological "need," critical for living a meaningful life and experiencing well-being (Ryan & Deci, 2017).

Indeed, SDT posits three basic psychological needs—autonomy, competence, and relatedness (Ryan et al., 2021). Autonomy involves feeling volitional in one's actions, competence relates to feelings of successfully mastering one's environment, and relatedness pertains to feelings of care and closeness in relationships (Ryan & Deci, 2017; Vansteenkiste et al., 2020). Autonomy support, characterized by autonomous environments, enhances the satisfaction of these needs, fostering healthy growth and subjective well-being (Vansteenkiste et al., 2020; Koestner et al., 2019).

Repeatedly, autonomy support has been related with increased in psychological need satisfaction, which then results in enhanced subjective well-being and fostered autonomous growth processes, such as integrative regulation and posttraumatic growth (Deci & Ryan, 2000; Gorin et al., 2014; Koestner et al., 2012; Koestner et al., 2015; Powers et al., 2008). Consequently, it is hypothesized that autonomy support may contribute to greater psychological need satisfaction, indirectly predicting increases in integrative regulation, posttraumatic growth, positive affect, and life satisfaction within the unique context of the COVID-19 crisis. These key concepts will be described in the subsequent sections.

Autonomy Support

Autonomy support forms the cornerstone of positive interpersonal connections, mutual care, and the overall quality of relationships (Ryan & Deci, 2019; Levine et al., 2021). Fundamentally, it involves support that fosters autonomous behaviors and feelings by offering choices through empathic perspective-taking. Autonomy-supportive individuals adopt an accepting stance, demonstrating genuine interest, respect, and care for others' feelings, creating an environment where individuals feel truly understood (Koestner et al., 2014; Levine et al., 2021). They exhibit openness, listen attentively to unfolding emotions, and refrain from hastily imposing their own perspectives on others (Roth et al., 2018).

Notably, autonomy support is related with a myriad of positive outcomes, including higher subjective well-being, progress towards personal goals, positive affect, happiness, psychological need satisfaction, and has even demonstrated the ability to bolster psychological resilience, particularly during the challenges imposed by the COVID-19 crisis (Audet et al., 2021; Ebersold et al., 2019; Froiland et al., 2019; Koestner et al., 2019; Neubauer et al., 2021). Specifically, individuals receiving autonomy support reported improved coping behaviors, enhanced interpersonal functioning, enriched relationship quality, and better mental health outcomes (Akram et al., 2022; Bülow et al., 2021; Neubauer et al., 2021). In essence, autonomy support cultivates a sense of initiative and choice, empowering individuals to act in ways that are authentically self-endorsed and purposeful to them—a true sense of autonomy.

The COVID-19 crisis presented an overwhelming period severing our connections to people for many. As of June 2023, there have been over 700 million confirmed cases of COVID-19, with nearly 7 million reported deaths (World Health Organization [WHO], 2023). Beyond the escalating financial and healthcare disparities, widespread governmental restrictions led to lockdowns, homelessness, poverty, precarious employment, and stringent enforcement of social isolation (Abrams & Szefler, 2020; Ajilore & Thames, 2020; WHO, 2023). Social and economic shutdowns disrupted the lives of many, resulting in the cancellation or postponement of daily activities and events (Levine et al., 2022; Masiero et al., 2020). This upheaval correlated with significant increases in mental health difficulties, traumatic grief experiences, and a profound sense of loss of identity and role for many (Masiero et al., 2020; Prati & Mancini, 2021; Serafini et al., 2020; Jassim et al., 2021; Wu et al., 2021).

Consequently, for some individuals, this period of restriction and control significantly diminished their sense of choice and experiencing their actions as being self-endorsed (Legate & Weinstein, 2021). Given that autonomy support fosters a sense of autonomy, the current research hypothesized that such support was particularly pivotal during the COVID-19 crisis—a time when individuals faced unparalleled challenges that compromised their sense of self and their capacity to feel genuinely autonomous (Brenning et al., 2022; Kämpfen et al., 2020).

Emotion Regulation Processes

Cultivating awareness of one's emotions plays a pivotal role in fostering adaptive and autonomous emotion regulation processes (Benita et al., 2020; Roth et al., 2018). However, thus far, there has been a very limited amount of research investigating emotion regulation within the context of the COVID-19 crisis. Emotions are valuable sources of information, which intricately shape individuals' choices and actions in meaningful ways, directly influencing well-being and life satisfaction (Ryan et al., 2006; Vansteenkiste et al., 2010; Schultz & Ryan, 2015). The complex landscape of emotion regulation encompasses the varied behaviors individuals employ to influence how, when, and in what manner they express and share their feelings (Calkins & Hill, 2007; Gross, 1998). This diversity extends to the nature, intensity, and expression of emotions, as well as individuals' responses to them—ranging from feelings of autonomy to feelings of control (Benita et al., 2020).

At the forefront of adaptive emotion regulation stands integrative regulation, an autonomous process that does not involve actively inhibiting or immediately altering emotional experiences. Instead, it centers on allowing and actively engaging with the meaning behind emotions (Roth et al., 2018). Research conducted during the COVID-19 crisis suggests that individuals who adopt strategies of integrative regulation may be benefited in higher life satisfaction, better sleep, and less anxiety and depression (Waterschoot et al., 2021). Other studies conducted before the COVID-19 crisis also suggest that integrative regulation fosters resilience in the face of challenging events (Roth et al., 2019; Weinstein et al., 2013).

In contrast to integrative regulation stands emotional dysregulation and suppression, emotional reactions which are experienced as pressuring, fragmenting, or overwhelming, leading to behaviors that feel more controlled than autonomous. In such cases, individuals may feel paralyzed or constrained in how they use or express their emotions, resulting in dysregulation or defensive suppression (Hodgins & Knee, 2002; Ryan, 2005). Research has shown these more controlled forms of emotion regulation processes, such as emotional dysregulation, pose a risk for mental health difficulties due to the sense of uncontrollability they bring (Compas et al., 2017). These processes of emotion regulation are predictive of maladjustments and psychopathology (Cole et al., 2013; Gross, 2015).

Taken together, integrative regulation, in essence, involves approaching emotions without the intention of altering, minimizing, ignoring, or flattening them (Roth et al., 2018). This process demands an active exploration of emotional reactions and their alignment with other facets of the self, such as values, short- and long-term goals, and personal preferences (Roth et al., 2018; Schultz & Ryan, 2015). Such a curious and attentive exploration positions individuals to make informed, volitional, and heartfelt choices, whether those entails expressing their emotions and seeking support or voluntarily withholding their emotions (Ryan et al., 2005; Kim et al., 2002). Integrative regulation empowers individuals to respond to their emotions autonomously. Given that autonomy support from close others encourages a sense of autonomy (Levine et al., 2020), the current study posits that such support would enable individuals to feel more autonomous in their emotions and way of being, aligning with the principles of integrative regulation.

Posttraumatic Growth

Furthermore, individuals exhibit significant variability in their responses to adverse events (Orejuela-Davila et al., 2019). Posttraumatic growth (PTG), a phenomenon elucidated by Tedeschi and Calhoun (2004), encapsulates the capacity of individuals to manifest growth and resilience in the aftermath of stressful or traumatic experiences. This growth is manifested through a heightened sense of personal strength, closer interpersonal relationships, and increased life satisfaction (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2004; Triplett et al., 2012). The COVID-19 crisis has been characterized as a collective trauma since it is marked by shared discourses and repeated co-constructed narratives (Hirschberger, 2018), entailing profound social, cultural, and economic upheavals (Abrams & Szefler, 2020; Ajilore & Thames, 2020; WHO, 2023). Therefore, examining how coping and resilience unfolded during is imperative not only for understanding the aftermath of the COVID-19 crisis but also for informing responses to future global crises, including climate change impacts, pandemics, and financial upheavals.

Numerous studies have demonstrated the positive relations of PTG with increased well-being, improved quality and meaning of life, enhanced psychological adjustment, and positive interpersonal gains. That is, PTG has been identified as a valuable resource for fostering healthy adaptation in the aftermath of challenging circumstances, such as those posed by the COVID-19 crisis (Cann et al., 2010; Chan et al., 2016; Husson et al., 2017; Ruini & Vescovelli, 2012; Kalaitzaki et al., 2021). The limited studies investigating PTG in relation to emotion regulation processes suggest a notable relation with integrative regulation (Orejuela-Davila et al., 2019; Larsen & Berenbaum, 2015). Specifically, prior research indicates that PTG is related to increased engagement with emotions, reduced emotional suppression, and lowered levels of psychological distress (Orejuela-Davila et al., 2019; Larsen & Berenbaum, 2015; Zhou et al., 2016).

Our hypothesis thus posits that autonomy support may contribute to greater PTG over time during the crisis. In this stressful context, the support for autonomy may be considered crucial for the development of PTG, as it encourages individuals to view the experience as a challenge to overcome rather than a threat or misfortune. This perspective, in turn, may assist individuals in re-evaluating the experience in a more meaningful and autonomous manner. Given the acknowledged benefits of PTG in adjusting to adverse events (Orejuela-Davila et al., 2019; Zhou et al., 2016), considering it alongside other positive outcomes such as integrative regulation, positive affect, and life satisfaction is undeniably crucial for developing strategies to address forthcoming global emergencies.

Present Investigation

The primary objective of the current study was to investigate the relationship between autonomy support from close individuals and key psychological outcomes—integrative regulation, posttraumatic growth, positive affect, and life satisfaction—during the tumultuous period of the COVID-19 crisis. Three hypotheses were formulated to guide this exploration. First, it was anticipated that autonomy support would relate to psychological need satisfaction, integrative regulation, posttraumatic growth, and subjective well-being (i.e., positive affect and life satisfaction; hypothesis 1). Second, the study hypothesized that psychological need satisfaction, as influenced by autonomy support, would serve as a significant predictor of integrative regulation, posttraumatic growth, and subjective well-being (i.e., positive affect and life satisfaction; hypothesis 2). Lastly, building on prior motivational research, the study proposed that psychological need satisfaction might act as a mediator in the relationship between autonomy support and integrative regulation, posttraumatic growth, and subjective well-being (i.e., positive affect and life satisfaction; hypothesis 3). This hypothesis aimed to shed light on the underlying mechanisms through which autonomy support contributes to positive psychological and emotional outcomes during challenging times.

Method

Participants and Procedure

This longitudinal study, comprising 535 community adults, was initiated during a highly challenging and unpredictable phase of the COVID-19 crisis, coinciding with the emergence of the first Omicron variant in November 2021. This period, marked by heightened stress and a sense of uncontrollability, provided a unique backdrop for investigating individuals' responses to the ongoing crisis. Recruitment was facilitated through the well-established research recruitment company, Leger. Over a span of nine months, participants engaged in three distinct phases of data collection, with a detailed summary of sample characteristics available in

Table 1.

The initial questionnaire (T1) was administered in November 2021, and required approximately 30-45 minutes for completion. Subsequently, the second questionnaire (T2) was dispatched in February 2022, with a reduced completion time of 10-15 minutes (retention rate of 85.59%). The final follow-up questionnaire (T3) was sent in July 2022, maintaining a similar completion timeframe of 10-15 minutes (retention rate of 79.63%). The distribution of questionnaires was facilitated through the online survey platform Qualtrics, and participants had one week to submit their responses.

To acknowledge and appreciate participants' contribution to the study, a compensation of CAD 8.50 per survey was provided. Prior to engaging in the study, participants were required to complete a consent form, affirming the confidential handling of their responses, assuring them of no adverse consequences for discontinuing participation, and underscoring the anonymization of their data to safeguard personal information. The study received ethical approval from the McGill University Research and Ethics Board, ensuring the adherence to ethical standards throughout the research process.

Transparency and Openness

The datasets generated and analyzed in the current study are not publicly available because they constitute an excerpt of research in progress but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

1

Measures

Autonomy Support

During the initial assessment (T1), participants were tasked with identifying four close individuals who had provided support throughout the challenging circumstances of the COVID-19 crisis, and elucidated the nature of their relationships. Examples, such as family members (e.g., siblings) or friends, were provided as reference points. The degree of perceived autonomy support from these identified supporters was gauged using a set of four items meticulously crafted for this purpose, drawing upon established measures from previous research on the COVID-19 crisis (Nguyen et al., 2019).

Participants responded to inquiries regarding the supportive behaviors of each individual, with questions structured to capture facets of autonomy support. For instance, participants considered statements like "Listens to my opinion and perspective when I’ve got a problem." Responses were recorded on a 5-point scale, spanning from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). To generate a comprehensive measure of perceived autonomy support, a mean score was computed for each supporter. These individual scores were then averaged across all participants, yielding a collective perceived autonomy support score indicative of the overall level of supportiveness from close others. The four-item autonomy support scale demonstrated high reliability, with a Cronbach's alpha of α = .93, affirming its internal consistency.

Psychological Need Satisfaction

At the second assessment (T2), the Balanced Measure of Psychological Needs scale (BPNS) was employed as a robust and widely recognized instrument for gauging satisfaction of the psychological needs (Sheldon & Hilpert, 2012; Van der Kaap-Deeder et al., 2020). Acknowledged for its reliability and validity, the BPNS comprises nine items distributed across three subscales, each addressing a fundamental psychological need. For the need for autonomy, an illustrative item reads, “I was free to do things my own way.” The need for competence is reflected in items such as “I was successfully completing difficult tasks and projects,” while the need for relatedness is encapsulated in statements like “I felt a sense of contact with people who care for me, and whom I care for.”

Participants expressed their responses to each item on a seven-point scale, ranging from 1 (not true at all) to 7 (very true). This nuanced approach allowed for a comprehensive exploration of participants' experiences in relation to their psychological needs. In the current dataset, the BPNS demonstrated high reliability, boasting a Cronbach's alpha of α = .86, affirming its internal consistency and reinforcing its standing as a dependable measure for evaluating psychological need satisfaction.

Integrative Regulation

The evaluation of individuals' emotion regulation processes at both T1 and T3 was conducted using an adapted version of the Emotion Regulation Inventory by Roth et al. (2009). Specifically tailored to capture the nuances of regulating emotions amidst the uncertainties and threats posed by the COVID-19 crisis, participants were tasked with rating their responses on a seven-point scale, spanning from 1 (not at all true) to 7 (very true). Integrative regulation was evaluated with three items exemplified by statements such as "In situations where I feel stressed or anxious, it is important for me to try to understand why I feel that way".

Mean scores were calculated at both time points, providing an overarching perspective on individuals' autonomous regulation tendencies. The reliability of the items demonstrated robust internal consistency, with Cronbach's alpha values being α = .88 at T1, and α = .89 at T3. These reliability measures underscore the stability and consistency of the instrument across both assessment periods, affirming its efficacy in capturing nuanced emotion regulation dynamics.

Posttraumatic Growth Inventory

To capture pandemic-specific posttraumatic growth, participants underwent evaluation at both T1 and T3 using an adapted version of the revised Posttraumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI-X; Tedeschi et al., 2017). This instrument prompted participants to reflect on significant changes in their personal narratives, encompassing life events, alterations in relationships, shifts in self-esteem/self-confidence, and changes in priorities or aspirations since the onset of the COVID-19 crisis. The PTGI is recognized as one of the most widely employed scales for assessing positive transformations following highly stressful or potentially traumatic events (Helgeson et al., 2006; Linley & Joseph, 2004; Tedeschi et al., 2017). Its adaptability to assess pandemic-specific posttraumatic growth has been evident across diverse populations (Chen et al., 2021; Feng et al., 2021; Li et al., 2021; Zhen and Zhou, 2022). Comprising 16 items distributed across five aspects—personal strengths, appreciation of life, new possibilities, spiritual changes, and relation to others—the PTGI delves into various dimensions of posttraumatic growth. For instance, statements like "I have a greater appreciation for the value of my own life" gauge appreciation of life, while "I established a new path for my life" assesses new possibilities, and "I have a greater sense of closeness with others" explores changes in relation to others.

Participants provided ratings for each item on a seven-point scale, spanning from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Mean scores were computed for each aspect at both time points, offering a comprehensive overview of participants' pandemic-specific posttraumatic growth. The PTGI demonstrated strong internal consistency, with reliability values of α = .89 at T1 and α = .90 at T3, affirming its robustness as a measure of positive transformations in the wake of the ongoing pandemic.

Subjective Well-Being

Subjective well-being, as conceptualized by Diener and colleagues, serves as a pivotal metric, encapsulating the evaluative judgment of one's life as a whole and the frequency of both pleasant and unpleasant emotional experiences (Diener et al., 1985, 1997). Established as a cornerstone in positive psychological health, these components have undergone extensive scrutiny and discussion, contributing significantly to the understanding of human well-being (Diener et al., 1985, 1997, 2013; Larsen & Diener, 1985; Pavot & Diener, 1993, 2013). The assessment of life satisfaction and affect occurred at both T1 and T3. Standardization preceded the calculation of means to facilitate comparisons across components.

Life Satisfaction, gauged through five items such as “The conditions of my life are excellent” employed a seven-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The reliability of this scale in the current dataset stood at α = .88 at T1 and increased to α = .93 at T3, affirming its consistency over time. Affect was measured using a nine-item scale, encompassing four positive (e.g., joyful) and five negative (e.g., frustrated) items. Responses were recorded on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 7 (extremely). The positive items demonstrated strong reliability, with α = .89 at T1 and α = .91 at T3. Conversely, the negative items, reverse-coded for analysis, exhibited a reliability of α = .75 at T1, rising to α = .88 at T3. These measures collectively provide a nuanced understanding of participants' subjective well-being, capturing both cognitive evaluations and emotional experiences across the dynamic landscape of the ongoing study.

Analytic Plan

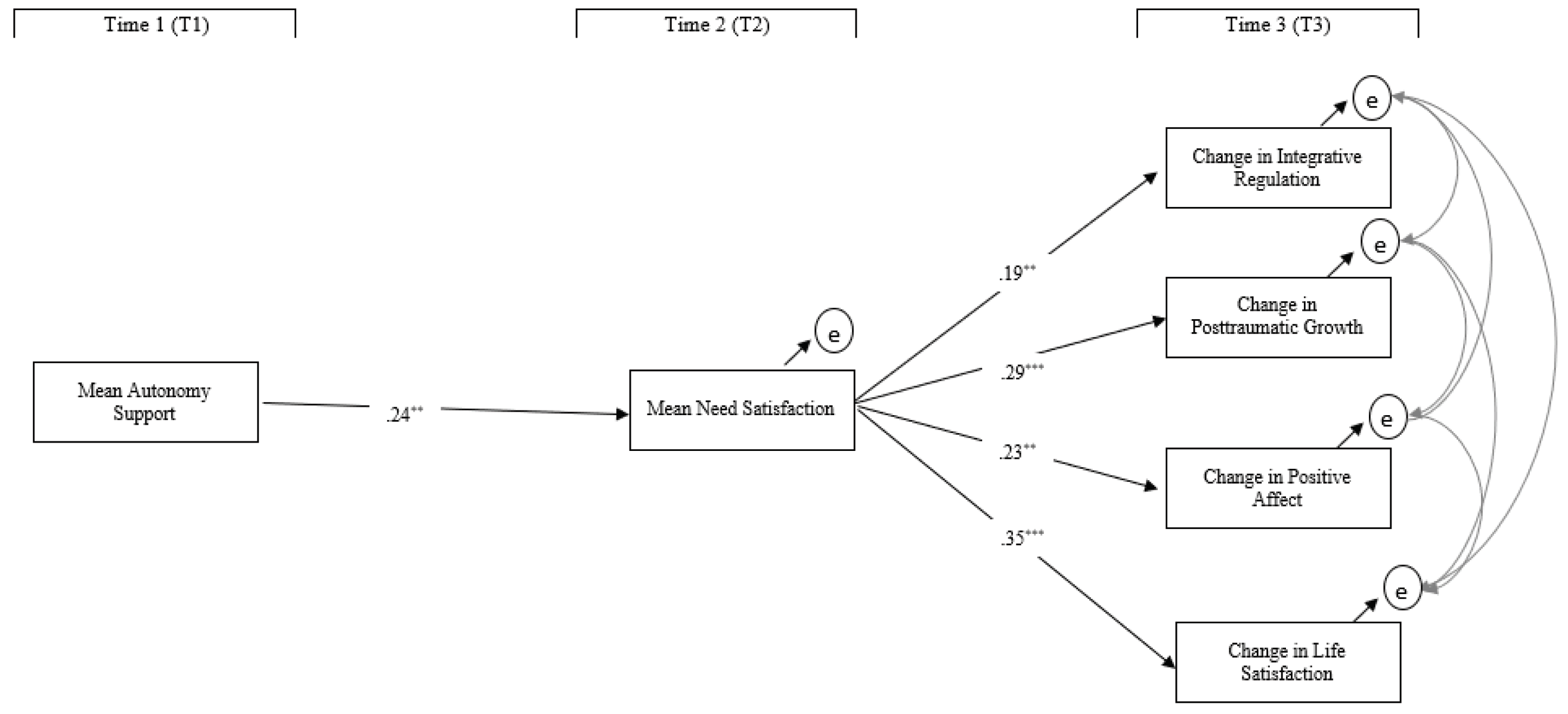

Preliminary descriptive analyses were first conducted, unveiling a comprehensive depiction of the study variables and their interrelations. These initial steps aimed to define the landscape of autonomy support from close others, psychological need satisfaction, integrative regulation, posttraumatic growth, affect, and life satisfaction, setting the stage for subsequent investigations. The focal point of the analysis was Structural Equation Modeling (SEM), a robust statistical technique employed to scrutinize the intricate relationships among variables over time, as illustrated in

Figure 1. Standardized residual change scores were calculated for integrative regulation, posttraumatic growth, positive affect, and life satisfaction, offering a nuanced understanding of changes from baseline to T3. Analyses included self-reported gender, age, native language, SES, ethnicity, and baseline measures as control variables.

To execute the SEM, robust maximum likelihood estimation (MLR) procedures provided by MPlus (Version 7.3; Muthén & Muthén, 2012) were implemented. This approach, known for its resilience to potential deviations from normality, ensured the reliability and accuracy of the model. The evaluation of model fit hinged on several key indices: the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR). A model was deemed acceptable if the CFI exceeded .90 and the RMSEA and SRMR remained at or below 0.06 (Kline, 2011). These fit indices served as crucial benchmarks, guiding the assessment of the SEM's appropriateness in elucidating the intricate dynamics of autonomy support, psychological need satisfaction, and their cascading effects on integrative regulation, posttraumatic growth, positive affect, and life satisfaction over the study's temporal trajectory.

Results

Descriptive and Correlation Analyses

Table 2 provides a comprehensive overview of key variables, depicting their descriptive statistics and intercorrelations. Integrative regulation exhibited no significant change over time, T1:

M=1.96,

SD=0.62; T3:

M=2.02,

SD=0.66;

t(134) = 0.07,

p = .34. In contrast, positive affect experienced a significant increase from T1,

M=2.84,

SD=0.98 to T3,

M=2.03,

SD= 1.07;

t(134) = 3.92,

p = .001. Similarly, life satisfaction saw a notable increase at T3,

M = 11.03,

SD = 4.32 compared to T1,

M = 9.75,

SD = 4.36;

t(133) = 3.40,

p = .001. However, posttraumatic growth exhibited a decrease over the year, T1:

M = 17.50,

SD = 14.34; T3:

M = 15.63,

SD = 11.05;

t(140) = 3.42,

p = .001, despite its retest stability over time,

r(141) = .69,

p < .001.

The bivariate associations in

Table 2 highlight positive correlations between autonomy support, psychological need satisfaction, and temporal changes in integrative regulation, posttraumatic growth, positive affect, and life satisfaction. Specifically, increased posttraumatic growth was related with the composite score of increases in all three subjective indicators,

r = .18,

p = .002.

Structural Equation Model (SEM)

The SEM depicted the intricate dynamics within the studied constructs. Autonomy support at T1 was related with T2 psychological need satisfaction, β = 0.23, SE = 0.09, 95% CI = [0.08, 0.51]. Subsequently, T2 psychological need satisfaction was related with changes in integrative regulation, β = 0.20, SE = 0.06, 95% CI = [0.04, 0.23], posttraumatic growth, β = 0.30, SE = 0.08, 95% CI = [0.13, 0.27], positive affect, β = 0.24, SE = 0.09, 95% CI = [.05, .71], and life satisfaction, β = 0.26, SE = 0.10, 95% CI = [0.19, 0.65], from T1 to T3.

All indirect paths were significant, underscoring the mediating role of psychological need satisfaction in explaining the correlations between autonomy support and integrative regulation, posttraumatic growth, positive affect, and life satisfaction. Specifically, integrative regulation, β = 0.04, SE = 0.03, 95% CI = [0.02, 0.10], posttraumatic growth, β = 0.06, SE = 0.06, 95% CI = [0.01, .013], positive affect, β = 0.07, SE = 0.04, 95% CI = [0.01, 0.14], and life satisfaction, β = 0.08, SE = 0.05, 95% CI = [0.03, 0.16], all demonstrated significant relations.

Overall, the proposed model, portrayed in

Figure 1, exhibited acceptable fit indices: MLR χ²(

df = 4) = 3.25,

p = .45, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = 0.00 (0.00, 0.11), SRMR = 0.03. These results validate the proposed correlations, elucidating the mediating role of psychological need satisfaction in delineating the indirect correlations between autonomy support and positive outcomes over the academic year.

Discussion

The COVID-19 crisis has left many individuals grappling with fear, terror, and concerns about an uncertain future. The collective trauma experienced during this period, characterized by financial and healthcare disparities, loss of loved ones, and widespread lockdowns, necessitates a nuanced understanding of individual responses and coping mechanisms (Stanley et al., 2021; Masiero et al., 2020; Schimmenti et al., 2020). Thus, this study delved into the exploration of variables influencing individuals' ability to derive personal meaning from the hardships of the COVID-19 crisis, focusing on the pivotal role of autonomy support.

Autonomy Support and Emotion Regulation

Consistent with the hypotheses, autonomy support emerged as a significant factor related to integrative regulation, a more adaptive form of emotion regulation. This may suggest that the supportive environment fostered by autonomy support encourages individuals to approach their emotional experiences with curiosity and non-judgment, even in the face of catastrophic events (Roth et al., 2018). Notably, these findings persisted during an intensely stressful period of the COVID-19 crisis, characterized by heightened frustration, fear, and exhaustion due to factors like the emergence of the Omicron variant (Moghadam & Moghadam, 2022; Kadir et al., 2022). Despite these challenges, close others seemed to have been able to effectively provide autonomous support, enabling their close ones to navigate and accept their emotions with awareness and volition.

Autonomy Support and Posttraumatic Growth

Building on the premise that autonomy support fosters autonomy and self-understanding, the current study hypothesized and found empirical support that it may also enhances posttraumatic growth (PTG). Autonomy support, by adopting an understanding stance and displaying genuine interest and care, aligns with the requisites of PTG, prompting individuals to reevaluate their lives, strengths, relationships, and possibilities. The current study contributes to the existing literature, reinforcing the idea that autonomy support plays a pivotal role not only in general well-being but also in facilitating personal growth during challenging circumstances (Audet et al., 2021; Akram et al., 2022; Bülow et al., 2021; Koestner et al., 2019; Levine et al., 2020; Ryan et al., 2021; Neubauer et al., 2021).

Autonomy Support and Subjective Well-Being

As anticipated based on prior research, autonomy support was found to enhance positive affect and life satisfaction, collectively contributing to subjective well-being. The study thus reinforcing past findings and further underscores the valuable benefits of perceiving autonomous forms of support, especially in the context of the COVID-19 crisis, which heightened isolation and mental health difficulties (Masiero et al., 2020; Prati & Mancini, 2021; Serafini et al., 2020; Jassim et al., 2021; Wu et al., 2021). Autonomy support emerged as a particularly meaningful source of support, countering feelings of control and impaired freedom during the crisis (Brenning et al., 2022; Legate & Weinstein, 2021; Kämpfen et al., 2020).

Psychological Need Satisfaction

Furthermore, autonomy support was hypothesized to increase psychological need satisfaction, thereby indirectly predicting increases in integrative regulation, posttraumatic growth, positive affect, and life satisfaction. This aligns with a robust body of literature linking autonomy support to psychological need satisfaction and its subsequent positive impact on well-being and personal growth processes (Deci & Ryan, 2000; Gorin et al., 2014; Koestner et al., 2012; Koestner et al., 2015; Powers et al., 2008). The current study extends these findings to the unique context of the COVID-19 crisis, emphasizing the resilience of these processes even during experiences of collective trauma.

In conclusion, this research contributes valuable insights into the role of autonomy support in promoting integrative regulation, posttraumatic growth, positive affect, and life satisfaction during the challenging events of the COVID-19 crisis. Understanding how close others can provide essential support to strengthen personal growth processes and well-being has broader implications for fostering resilience during demanding times. This knowledge can inform interventions and support systems to better navigate future global emergencies and crises.

Limitations

While this study encompasses strengths such as employing a robust three-wave, longitudinal design, validated measures, and a substantial sample size, it is essential to acknowledge and address several limitations that temper the generalizability and interpretability of the findings. First, the correlational design of the study hinders the establishment of causal relationships. Although hypotheses were grounded in theoretical frameworks and supported by prior research, caution is warranted in making definitive causal inferences. Future studies employing experimental designs or intervention studies would provide a more robust basis for causal claims. Second, a crucial limitation lies in the inability to ascertain the objective severity of stressors faced by individuals during the COVID-19 crisis. The study did not differentiate whether participants encountered concrete stressful events (e.g., financial struggles, health issues, etc.) or if individual differences influenced subjective perceptions of stress. Incorporating objective stress assessments would enhance the precision of understanding the actual distress experienced by individuals.

Third, the study utilized an online recruitment company, potentially introducing biases in sample representation. Future research should strive to replicate findings with more diverse samples, accounting for various life circumstances. It is plausible that individuals facing significant adversity during the COVID-19 crisis, such as those with lower socio-economic status, may be underrepresented. A more comprehensive exploration of diverse populations would strengthen the external validity of the study. Fourth, the sole reliance on self-report measures introduces inherent limitations, including potential biases such as social desirability or exaggeration. While self-reports are commonly employed in social science research and generally accurate, incorporating more objective assessments or adopting a multi-informant approach would bolster the robustness of the findings. Including external reports or psychophysiological indicators of stress reactivity would provide a more comprehensive understanding of the variables under investigation.

Finally, the findings of the study are specific to the unique circumstances of the COVID-19 crisis and cannot be extrapolated to other crisis situations. Future research could explore how the relationships between these variables unfold in diverse crises to enhance the generalizability of the findings. In conclusion, while the current study contributes valuable insights, these limitations underscore the need for continued research refinement. Addressing these concerns will fortify the validity and reliability of the findings and will also facilitate a more nuanced understanding of the complex interplay between autonomy support, psychological need satisfaction, emotion regulation, posttraumatic growth, positive affect, and life satisfaction during times of crisis.

Implications and Future Directions

Despite the acknowledged limitations, the findings of this study hold important implications for both research and practical applications, paving the way for targeted interventions and enriching interpersonal dynamics. First, the study advocates for the integration of autonomy support in interventions and counseling programs. Tailoring interventions to emphasize and enhance autonomous forms of support, both in giving and receiving, could prove instrumental. Workshops designed to educate individuals on providing this type of support—embracing compassion, respecting emotional expressions, and acknowledging the withholding of emotions—could be developed. Such initiatives would contribute to fostering more genuine, intimate, and harmonious interpersonal relationships.

In addition, the study underscores the potential benefits of promoting open awareness and non-judgmental exploration of emotions. Interventions and educational programs could teach individuals the value of welcoming and acknowledging their emotional experiences, understanding the roots of these emotions, and then determining deliberate and autonomous responses. This knowledge can empower individuals to engage with their emotions thoughtfully, fortifying adaptive coping mechanisms and facilitating personal growth, particularly in challenging circumstances.

In summary, the study suggests that perceiving autonomy support from close others contributes to individuals being more open, non-judgmental, and mindful of their emotions. This, in turn, facilitates personal growth and enhances subjective well-being, even in the face of chaotic circumstances. The profound impact of autonomy support emphasizes its role as a catalyst for coping and thriving during global uncertainty. These implications collectively underscore the potential for autonomy support to serve as a cornerstone for promoting personal growth and subjective well-being, offering avenues for innovative research and practical interventions that can positively shape individuals' experiences in challenging times.

Conclusion

The relentless waves of stress unleashed by the COVID-19 crisis left an indelible mark on individuals, unveiling profound disparities in their responses and adaptive capacities. In seeking to unravel the intricacies of personal growth and subjective well-being amidst the crisis, this three-wave, longitudinal study employed a robust design to illuminate the inherent tendencies within individuals. The findings suggests that psychological need satisfaction had profound relations on integrative regulation, posttraumatic growth, positive affect, and life satisfaction. Notably, the intricate web of correlations were significantly influenced by autonomy support—a poignant reminder of the transformative power embedded in acts of listening, providing choices, and offering empathy, even during collective crisis.

In essence, as the world grapples with the enduring aftermath of the COVID-19 crisis, this study underscores the pivotal role of autonomous environments in nurturing personal growth, meaning-making, and flourishing. It accentuates the imperative of fostering environments that recognize and meet psychological needs, while underscoring the transformative potential embedded in the simple yet powerful acts of autonomy support. As we navigate the uncertain terrain ahead, these insights gesture towards a future where individuals not only weather the storms but emerge, resilient and flourishing, on the other side.

Conflicts of Interest

We have no conflicts of interest to disclose. The study was conducted in compliance with APA ethical standards. The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The preparation of this manuscript was supported by a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada grant (767-2022-1914).

| 1 |

No other work has yet been published using this dataset. |

References

- Abrams, E.M.; Szefler, S.J. COVID-19 and the impact of social determinants of health. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine 2020, 8, 659–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajilore, O.; Thames, A.D. The fire this time: the stress of racism, inflammation and COVID-19. Brain, behavior, and immunity 2020, 88, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akram, A.R.; Abidin, F.A.; Lubis, F.Y. Parental Autonomy Support and Psychological Well-Being in University Students During the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Role of Autonomy Satisfaction. The Open Psychology Journal 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonucci, T.C.; Birditt, K.S.; Sherman, C.W.; Trinh, S. Stability and change in the Intergenerational family: A convoy approach. Aging and Society 2011, 31, 1084–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Audet, É.C.; Levine, S.L.; Holding, A.C.; Koestner, R.; Powers, T.A. A remarkable alliance: Sibling autonomy support and goal progress in emerging adulthood. Family Relations 2021, 70, 1571–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audet, É.C.; Levine, S.L.; Holding, A.C.; Powers, T.A.; Koestner, R. Navigating the ups and downs: peer and family autonomy support during personal goals and crises on identity development. Self and Identity 2021, 1-18, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Barman, A.; Das, R.; De, P.K. Impact of COVID-19 in food supply chain: Disruptions and recovery strategy. Current Research in Behavioral Sciences 2021, 2, 100017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchaine, T.P.; Cicchetti, D. Emotion dysregulation and emerging psychopathology: A transdiagnostic, transdisciplinary perspective. Development and psychopathology 2019, 31, 799–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benita, M. Freedom to feel: A self-determination theory account of emotion regulation. Social and personality psychology compass 2020, 14, e12563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenning, K.; Soenens, B.; Van Petegem, S.; Vansteenkiste, M. Perceived maternal autonomy support and early adolescent emotion regulation: A longitudinal study. Social Development 2015, 24, 561–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenning, K., Waterschoot, J., Dieleman, L., Morbée, S., Vermote, B., Soenens, B., ... & Vansteenkiste, M. (2022). The role of emotion regulation in mental health during the COVID-19 outbreak: A 10-wave longitudinal study. Stress and Health. [CrossRef]

- Blanke, E.S.; Brose, A.; Kalokerinos, E.K.; Erbas, Y.; Riediger, M.; Kuppens, P. Mix it to fix it: Emotion regulation variability in daily life. Emotion 2020, 20, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bülow, A.; Keijsers, L.; Boele, S.; van Roekel, E.; Denissen, J.J.A. Parenting adolescents in times of a pandemic: Changes in relationship quality, autonomy support, and parental control? Developmental Psychology 2021, 57, 1582–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bindman, S.W.; Pomerantz, E.M.; Roisman, G.I. Do children’s executive functions account for associations between early autonomy-supportive parenting and achievement through high school? Journal of educational psychology 2015, 107, 756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calkins, S.D., & Hill, A. (2007). Caregiver influences on emerging emotion regulation. Handbook of emotion regulation, 229248.

- Carroll, N., Sadowski, A., Laila, A., Hruska, V., Nixon, M., Ma, D.W., ... & Guelph Family Health Study. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on health behavior, stress, financial and food security among middle to high income Canadian families with young children. Nutrients, 12, 2352. [CrossRef]

- Compas, B.E., Jaser, S.S., Bettis, A.H., Watson, K.H., Gruhn, M.A., Dunbar, J.P., ... & Thigpen, J.C. (2017). Coping, emotion regulation, and psychopathology in childhood and adolescence: A meta-analysis and narrative review. Psychological bulletin, 143, 939. [CrossRef]

- Cann, A.; Calhoun, L.G.; Tedeschi, R.G.; Solomon, D.T. Posttraumatic growth and depreciation as independent experiences and predictors of well-being. Journal of Loss and Trauma 2010, 15, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.J.; Young, M.Y.; Sharif, N. Well-being after trauma: A review of posttraumatic growth among refugees. Canadian Psychology/psychologie canadienne 2016, 57, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Sun, C.; Chen, J.J.; Jen, H.J.; Kang, X.L.; Kao, C.C.; Chou, K.R. A large-scale survey on trauma, burnout, and posttraumatic growth among nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic. International journal of mental health nursing 2021, 30, 102–116. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cicchetti, D., Toth, S.L., Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Hilt, L.M. (2009). A developmental psychopathology perspective on adolescent depression. Handbook of depression in adolescents, 3-32.

- Ebersold, S.; Rahm, T.; Heise, E. Autonomy support and well-being in teachers: differential mediations through basic psychological need satisfaction and frustration. Social Psychology of Education 2019, 22, 921–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Yin, R. Social support and hope mediate the relationship between gratitude and depression among front-line medical staff during the pandemic of COVID-19. Frontiers in Psychology 2021, 12, 623873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Froiland, J.M.; Worrell, F.C.; Oh, H. Teacher–student relationships, psychological need satisfaction, and happiness among diverse students. Psychology in the Schools 2019, 56, 856–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, B.Q.; Gross, J.J. Why beliefs about emotion matter: An emotion-regulation perspective. Current Directions in Psychological Science 2019, 28, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. (2018). PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling [White paper]. Retrieved from http://www.afhayes.com/ public/process2018.pdf.

- Helgeson, V.S.; Reynolds, K.A.; Tomich, P.L. A meta-analytic review of benefit finding and growth. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology 2006, 74, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschberger, G. Collective trauma and the social construction of meaning. Frontiers in psychology 2018, 9, 1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgins, H.S.; Knee, C.R. The integrating self and conscious experience. Handbook of self-determination research 2002, 87, 86–98. [Google Scholar]

- Husson, O.; Zebrack, B.; Block, R.; Embry, L.; Aguilar, C.; Hayes-Lattin, B.; Cole, S. Posttraumatic growth and well-being among adolescents and young adults (AYAs) with cancer: a longitudinal study. Supportive Care in Cancer 2017, 25, 2881–2890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jassim, G.; Jameel, M.; Brennan, E.; Yusuf, M.; Hasan, N.; Alwatani, Y. Psychological impact of COVID-19, isolation, and quarantine: A cross-sectional study. Neuropsychiatric disease and treatment 2021, 1413–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadir, A.; Deby, S.; Muhammad, A. A systematic review of omicron outbreak in Indonesia: a case record and Howthe country is weathering the new variant of COVID-19. Eur. J. Mol. Clin. Med 2022, 9, 364–373. [Google Scholar]

- Kalaitzaki, A., Tsouvelas, G., & Tamioolaki, A. (2021). Posttraumatic Growth During Two Consecutive COVID-19 Lockdowns in Greece: Shared and Unique Predictors of its Constructive Aspect. Available at SSRN 3970761. [CrossRef]

- Kämpfen, F.; Kohler, I.V.; Ciancio, A.; Bruine de Bruin, W.; Maurer, J.; Kohler, H.P. Predictors of mental health during the Covid-19 pandemic in the US: Role of economic concerns, health worries and social distancing. PloS one 2020, 15, e0241895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koestner, R.; Lekes, N.; Powers, T.A.; Chicoine, E. Attaining personal goals: self-concordance plus implementation intentions equals success. Journal of personality and social psychology 2002, 83, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koestner, R.; Powers, T.A.; Carbonneau, N.; Milyavskaya, M.; Chua, S.N. Distinguishing autonomous and directive forms of goal support: Their effects on goal progress, relationship quality, and subjective well-being. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 2012, 38, 1609–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koestner, R.; Powers, T.A.; Holding, A.; Hope, N.; Milyavskaya, M. The relation of parental support of emerging adults’ goals to well-being over time: the mediating roles of goal progress and autonomy need satisfaction. Motivation Science 2020, 6, 374–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koestner, R.; Powers, T.A.; Milyavskaya, M.; Carbonneau, N.; Hope, N. Goal internalization and persistence as a function of autonomous and directive forms of goal support. Journal of Personality 2015, 83, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koestner, R.; Powers, T.A.; Milyavskaya, M.; Carbonneau, N.; Hope, N. Goal internalization and persistence as a function of autonomous and directive forms of goal support. Journal of Personality 2015, 83, 179–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.; Deci, E.L.; Zuckerman, M. The development of the self-regulation of withholding negative emotions questionnaire. Educational and Psychological Measurement 2002, 62, 316–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laporte, N.; Soenens, B.; Brenning, K.; Vansteenkiste, M. Adolescents as active managers of their own psychological needs: The role of psychological need crafting in adolescents’ mental health. Journal of Adolescence 2021, 88, 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, S.E.; Berenbaum, H. Are specific emotion regulation strategies differentially associated with posttraumatic growth versus stress? Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma 2015, 24, 794–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legate, N.; Weinstein, N. Can we communicate autonomy support and a mandate? How motivating messages relate to motivation for staying at home across time during the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Communication 2022, 37, 1842–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, S.L.; Holding, A.C.; Milyavskaya, M.; Powers, T.A.; Koestner, R. Collaborative autonomy: The dynamic relations between personal goal autonomy and perceived autonomy support in emerging adulthood results in positive affect and goal progress. Motivation Science 2021, 7, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Sun, Y.; Maccallum, F.; Chow, A.Y. Depression, anxiety and post-traumatic growth among bereaved adults: A latent class analysis. Frontiers in Psychology 2021, 11, 575311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linley, P.A.; Joseph, S. Positive change following trauma and adversity: A review. Journal of traumatic stress: official publication of the international society for traumatic stress studies 2004, 17, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masiero, M.; Mazzocco, K.; Harnois, C.; Cropley, M.; Pravettoni, G. From individual to social trauma: Sources of everyday trauma in Italy, the US and UK during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation 2020, 21, 513–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghadam, Z.T.; Moghadam, M.T. Psychological problems and increased stress in pregnant women in the prevalence of Omicron variant. Iranian Red Crescent Medical Journal 2022, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neubauer, A.B.; Schmidt, A.; Kramer, A.C.; Schmiedek, F. A little autonomy support goes a long way: Daily autonomy-supportive parenting, child well-being, parental need fulfillment, and change in child, family, and parent adjustment across the adaptation to the COVID-19 pandemic. Child Development 2021, 92, 1679–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orejuela-Dávila, A.I.; Levens, S.M.; Sagui-Henson, S.J.; Tedeschi, R.G.; Sheppes, G. The relation between emotion regulation choice and posttraumatic growth. Cognition and Emotion 2019, 33, 1709–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prati, G.; Mancini, A.D. The psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns: a review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies and natural experiments. Psychological medicine 2021, 51, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, G.; Assor, A. The costs of parental pressure to express emotions: Conditional regard and autonomy support as predictors of emotion regulation and intimacy. Journal of adolescence 2012, 35, 799–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roth, G.; Vansteenkiste, M.; Ryan, R.M. Integrative emotion regulation: Process and development from a self-determination theory perspective. Development and psychopathology 2019, 31, 945–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, G.; Assor, A.; Niemiec, C.P.; Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. The emotional and academic consequences of parental conditional regard: comparing conditional positive regard, conditional negative regard, and autonomy support as parenting practices. Developmental psychology 2009, 45, 1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruini, C.; Offidani, E.; Vescovelli, F. Life stressors, allostatic overload, and their impact on posttraumatic growth. Journal of Loss and Trauma 2015, 20, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L.; Vansteenkiste, M. Autonomy and autonomy disturbances in self-development and psychopathology: Research on motivation, attachment, and clinical process. Developmental psychopathology 2016, 1, 385–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M. The developmental line of autonomy in the etiology, dynamics, and treatment of borderline personality disorders. Development and psychopathology 2005, 17, 987–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L.; Vansteenkiste, M. Autonomy and autonomy disturbances in self-development and psychopathology: Research on motivation, attachment, and clinical process. Developmental psychopathology 2016, 1, 385–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M., Ryan, W.S., Di Domenico, S.I., & Deci, E.L. (2019). The nature and the conditions of human autonomy and flourishing: Self-determination theory and basic psychological needs. [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L.; Vansteenkiste, M. Autonomy and autonomy disturbances in self-development and psychopathology: Research on motivation, attachment, and clinical process. Developmental psychopathology 2016, 1, 385–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M., & Deci, E.L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. Guilford Publications.

- Schultz, P.P.; Ryan, R.M.; Niemiec, C.P.; Legate, N.; Williams, G.C. Mindfulness, work climate, and psychological need satisfaction in employee well-being. Mindfulness 2015, 6, 971–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schimmenti, A.; Billieux, J.; Starcevic, V. The four horsemen of fear: An integrated model of understanding fear experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. Clinical Neuropsychiatry 2020, 17, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serafini, G., Parmigiani, B., Amerio, A., Aguglia, A., Sher, L., & Amore, M. (2020). The psychological impact of COVID-19 on the mental health in the general population. [CrossRef]

- Sheppes, G.; Suri, G.; Gross, J.J. Emotion regulation and psychopathology. Annual review of clinical psychology 2015, 11, 379–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahar, B.H.; Kalman-Halevi, M.; Roth, G. Emotion regulation and intimacy quality: The consequences of emotional integration, emotional distancing, and suppression. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 2019, 36, 3343–3361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi, R.G.; Cann, A.; Taku, K.; Senol-Durak, E.; Calhoun, L.G. The posttraumatic growth inventory: A revision integrating existential and spiritual change. Journal of Traumatic Stress 2017, 30, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tedeschi, R.G.; Calhoun, L.G. A clinical approach to posttraumatic growth. Positive psychology in practice 2004, 405–419. [Google Scholar]

- Triplett, K.N.; Tedeschi, R.G.; Cann, A.; Calhoun, L.G.; Reeve, C.L. Posttraumatic growth, meaning in life, and life satisfaction in response to trauma. Psychological trauma: Theory, research, practice, and policy 2012, 4, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vansteenkiste, M.; Ryan, R.M. On psychological growth and vulnerability: basic psychological need satisfaction and need frustration as a unifying principle. Journal of psychotherapy integration 2013, 23, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vansteenkiste, M., Niemiec, C.P., & Soenens, B. (2010). The development of the five mini-theories of self-determination theory: An historical overview, emerging trends, and future directions. The decade ahead: Theoretical perspectives on motivation and achievement.

- Van der Kaap-Deeder, J.; Vansteenkiste, M.; Soenens, B.; Mabbe, E. Children’s daily well-being: The role of mothers’, teachers’, and siblings’ autonomy support and psychological control. Developmental psychology 2017, 53, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasquez, A.C.; Patall, E.A.; Fong, C.J.; Corrigan, A.S.; Pine, L. Parent autonomy support, academic achievement, and psychosocial functioning: A meta-analysis of research. Educational Psychology Review 2016, 28, 605–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vansteenkiste, M.; Ryan, R.M.; Soenens, B. Basic psychological need theory: advancements, critical themes, and future directions. Motivation and Emotion 2020, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterschoot, J.; Van der Kaap-Deeder, J.; Morbée, S.; Soenens, B.; Vansteenkiste, M. “How to unlock myself from boredom?” The role of mindfulness and a dual awareness-and action-oriented pathway during the COVID-19 lockdown. Personality and Individual Differences 2021, 175, 110729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waterschoot, J.; Morbée, S.; Vermote, B.; Brenning, K.; Flamant, N.; Vansteenkiste, M.; Soenens, B. Emotion regulation in times of COVID-19: A person-centered approach based on self-determination theory. Current psychology 2022, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Jia, X.; Shi, H.; Niu, J.; Yin, X.; Xie, J.; Wang, X. Prevalence of mental health problems during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of affective disorders 2021, 281, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, R.; Zhou, X. Latent patterns of posttraumatic stress symptoms, depression, and posttraumatic growth among adolescents during the covid-19 pandemic. Journal of Traumatic Stress 2022, 35, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Wu, X.; Zeng, M.; Tian, Y. The relationship between emotion regulation and PTSD/PTG among adolescents after the Ya’an earthquake: The moderating role of social support. Acta Psychologica Sinica 2016, 48, 969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).