Submitted:

21 February 2024

Posted:

22 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

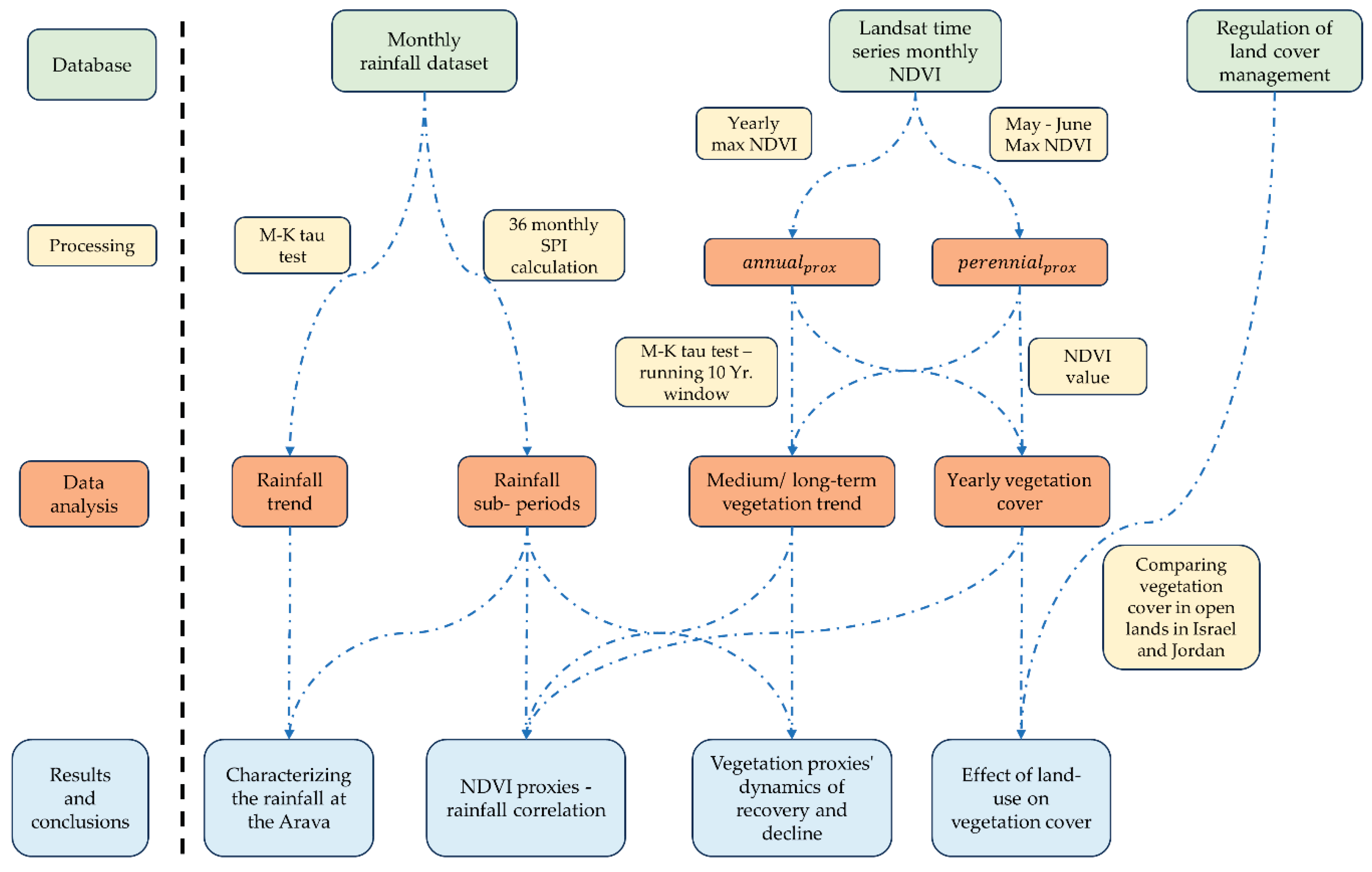

- Assessing the long-term trends in rainfall patterns in the Arava Valley over the past four decades and investigating the potential subdivision into climatic periods based on clusters of distinct "wet" and "dry" sub-periods;

- Evaluating the correlation between the yearly and the multi yearly accumulated rainfall and NDVI proxies for perennial and annual vegetation in a hyper-arid environment;

- Comparing the temporal dynamics of vegetation recovery and decline in response to climatic changes within the Arava Valley, specifically examining whether these dynamics differ between annual and perennial vegetation types;

- Identifying differences in vegetation growth between grazed and non-grazed areas within a hyper-arid environment.

2. Methodology

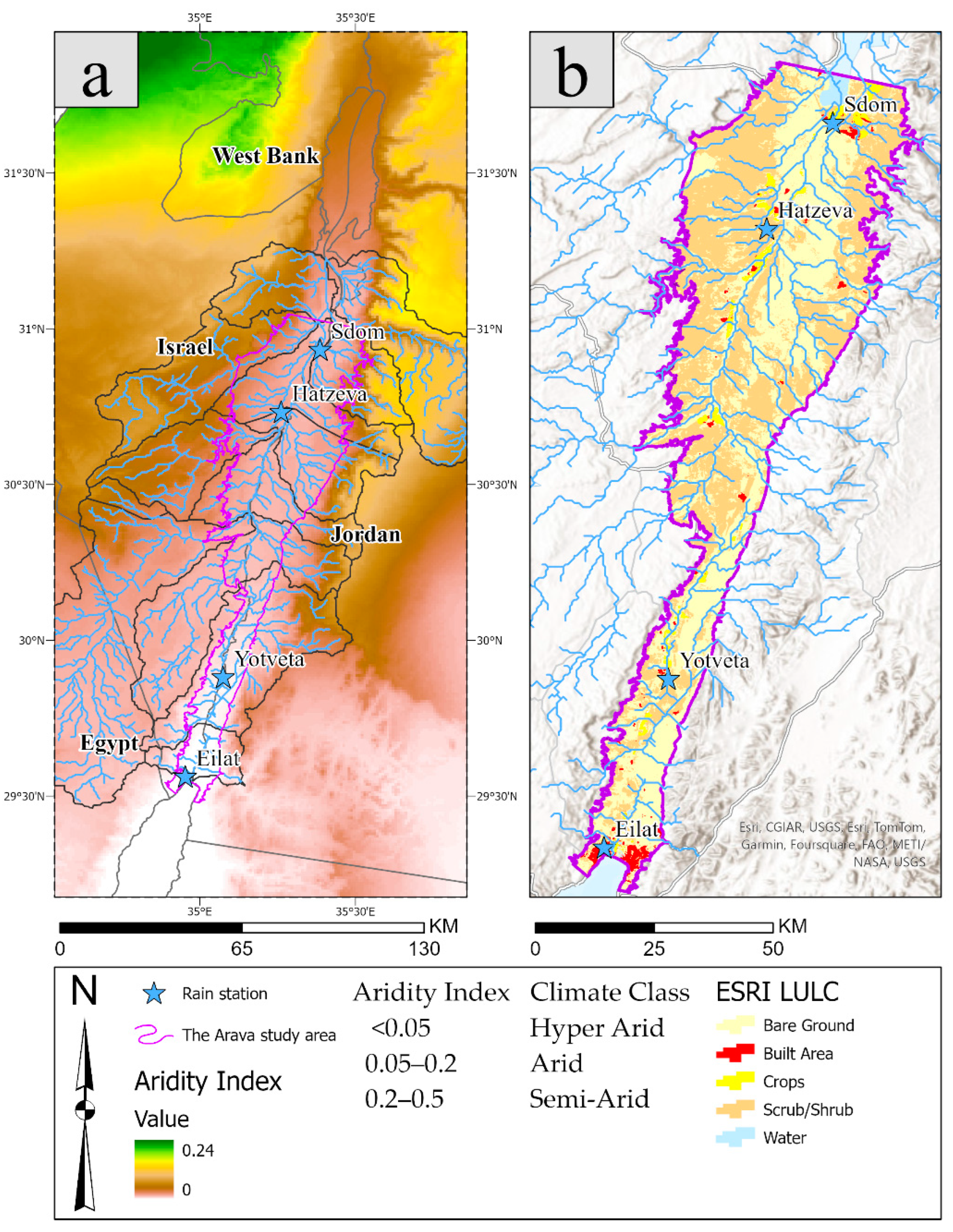

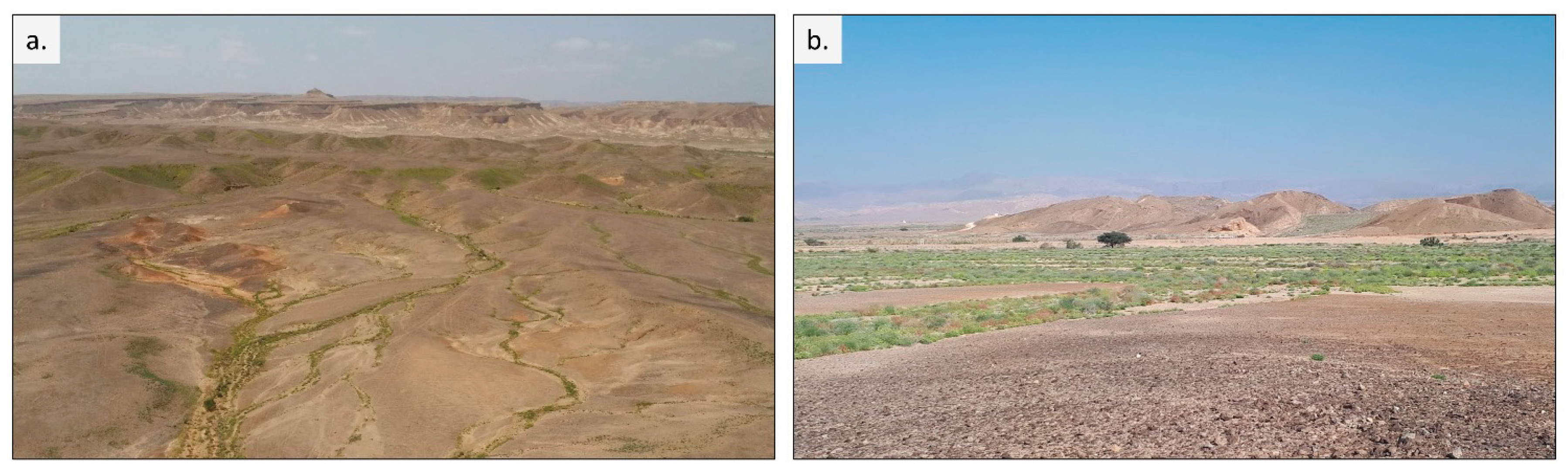

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Database, Processing and Analysis

2.2.1. Meteorological Rainfall Data

Assessing the Rainfall Trend

Computing the Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI)

Evaluating Climatic Sub-Periods

2.2.2. Remote Sensing Imagery

Proxies of Vegetation Cover

-

Annual vegetation cover reaches its highest NDVI values following a few intensive rainfall events and diminishes quickly as temperatures rise and water becomes unavailable at the end of the winter season [66,67,68].

- Thus, for every image in the Landsat collection, we calculated per-pixel the yearly maximum NDVI values within the rainfall season, (a 12-month period beginning October 1) and constructed them as a yearly mosaic of the maximum NDVI values. Together they form the time series of the annual vegetation for the years 1984-2021. The proxy is referred, annualprox. The annualprox cover was done similarly to [14,69]

-

Perennial vegetation can be photosynthetically active throughout the year but shows its highest spectral response towards the late spring (May-June), while at this time the annual vegetation is mostly absent [12,68].

- Thus, for every set of annual images in the Landsat collection, we calculated per-pixel the yearly maximum NDVI values found in May and June (i.e., late spring) and constructed them as a yearly mosaic of the values. Together they form the time series of the proxy for perennial vegetation for the years 1984-2021 The proxy is referred, perennialprox.

Data Sampling

2.2.3. Trend Analysis of Vegetation Cover

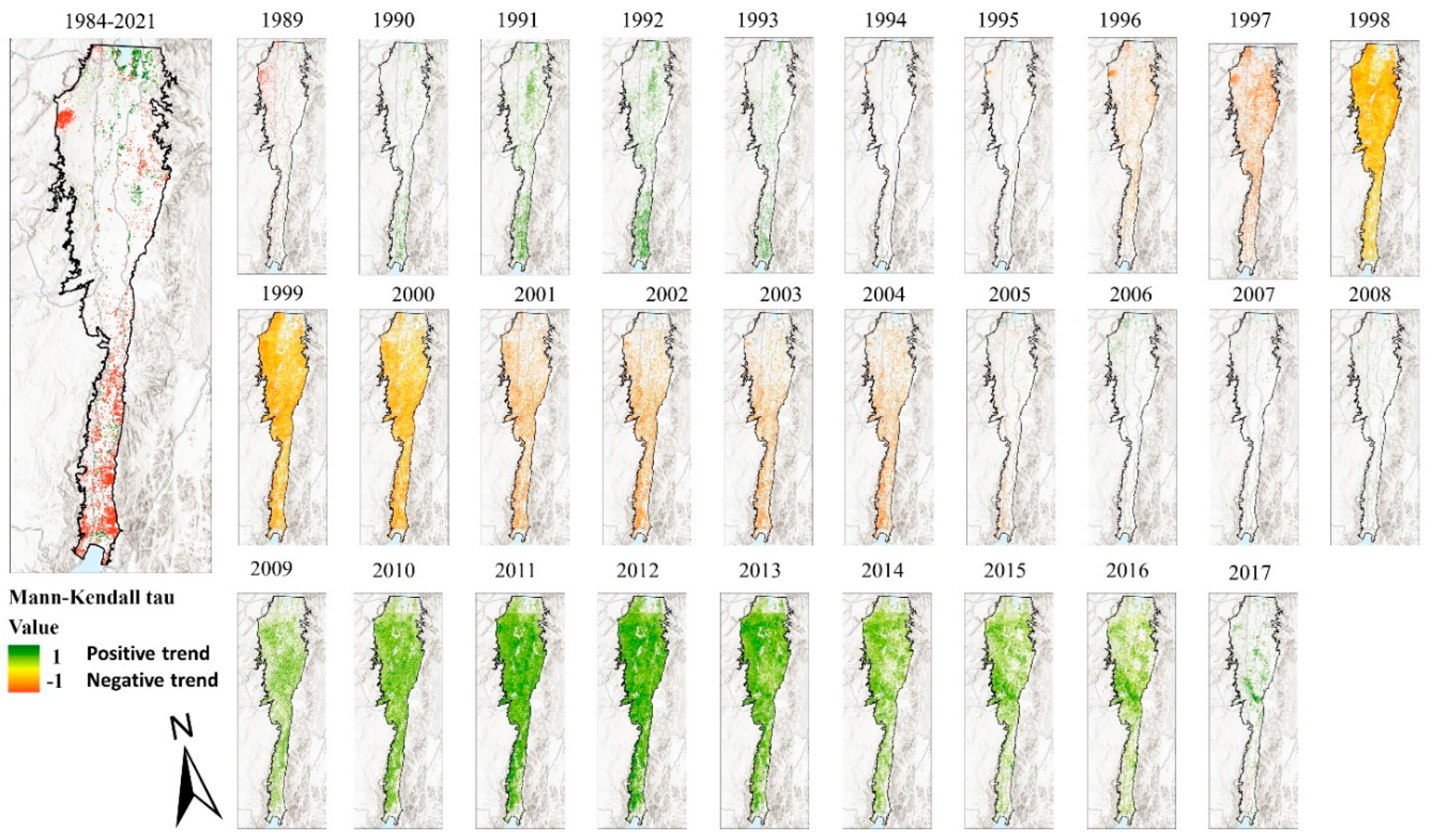

- Each time series of the NDVI proxies (annual and perennial) dataset was divided into 29 short 10-year periods of consecutive years.

- We executed the M-K Tau test for each short period (e.g., 1990-1999, 1991-2000, 1992-2001, etc.).

- The M-K calculation provided a new, pixel-based imagery dataset composed of a pair of images: a 10-year trend image (ranging between -1 to +1, for negative and positive trends), and a significant level image.

- We used the significant level imagery at p ≤ 0.01, pixels whose significance level were lower than sig0.01 received a new value of 0, and the two images were multiplied.

- Each of the two newly constructed datasets contains 29 images expressing a 10-year NDVI trend at a high significance level. Hereafter, the new datasets will be referred to as M-K time series.

- In the M-K time series, each image refers to the middle of the measured period; for example, M-K annual/perennial 1990 refers to the M-K test based on NDVI time series for the years 1985 – 1994 for annual or perennial vegetation.

2.2.4. Effect of Land Use

3. Results

3.1. Rainfall Correlation and Climatic Periods

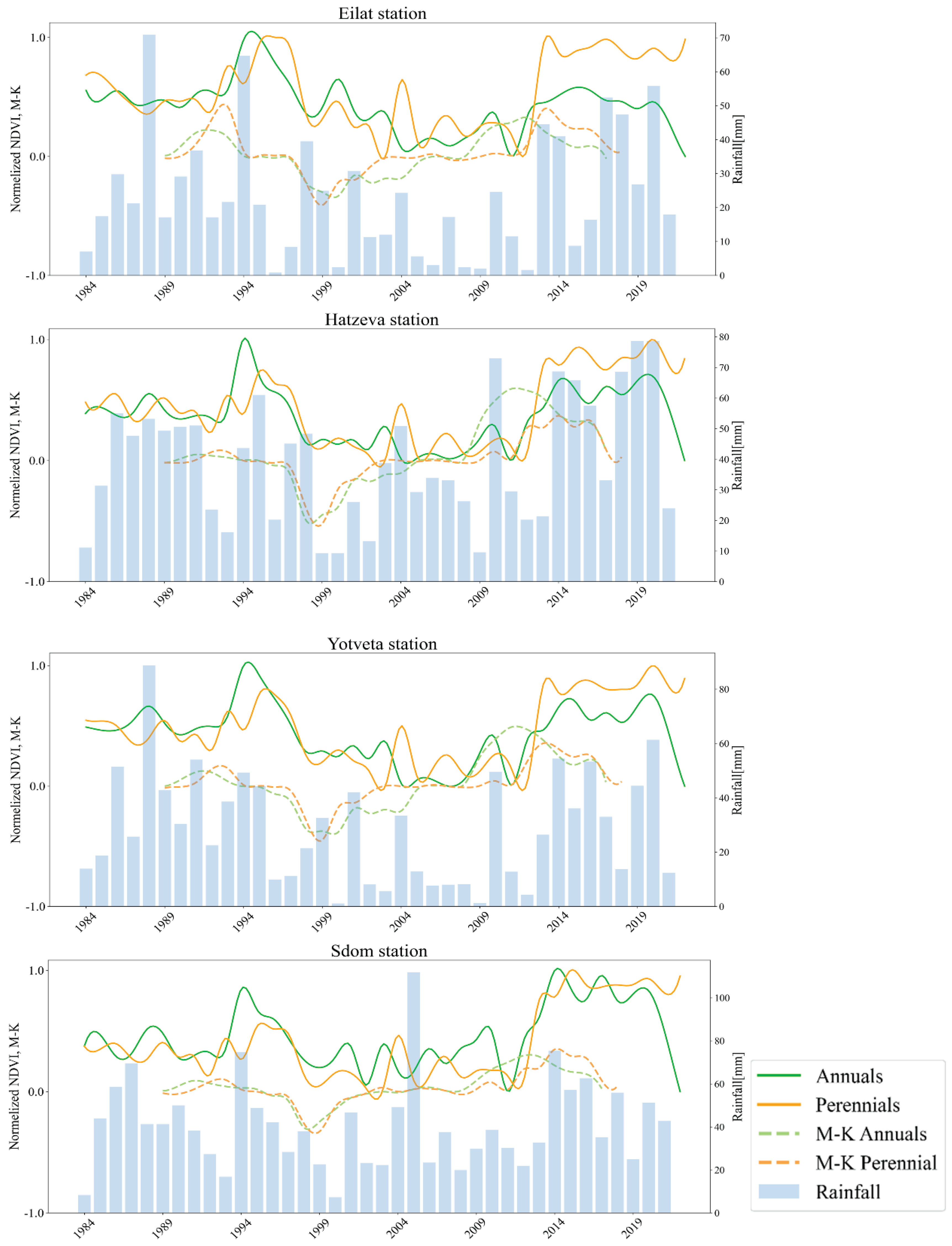

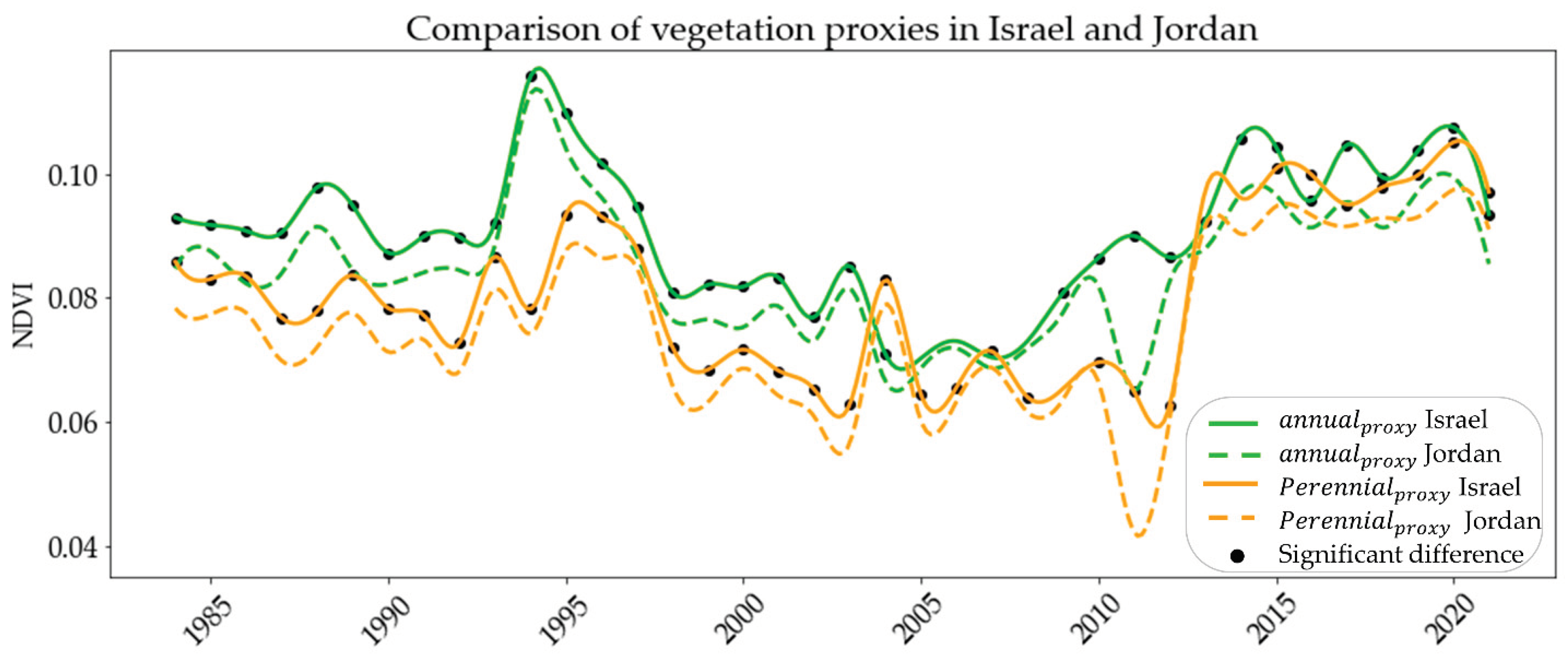

3.2. Yearly Vegetation Cover

3.2.1. Correlations between the Yearly Vegetation Proxies along the Arava Valley

3.2.2. Correlations between Rainfall and Vegetation Proxies

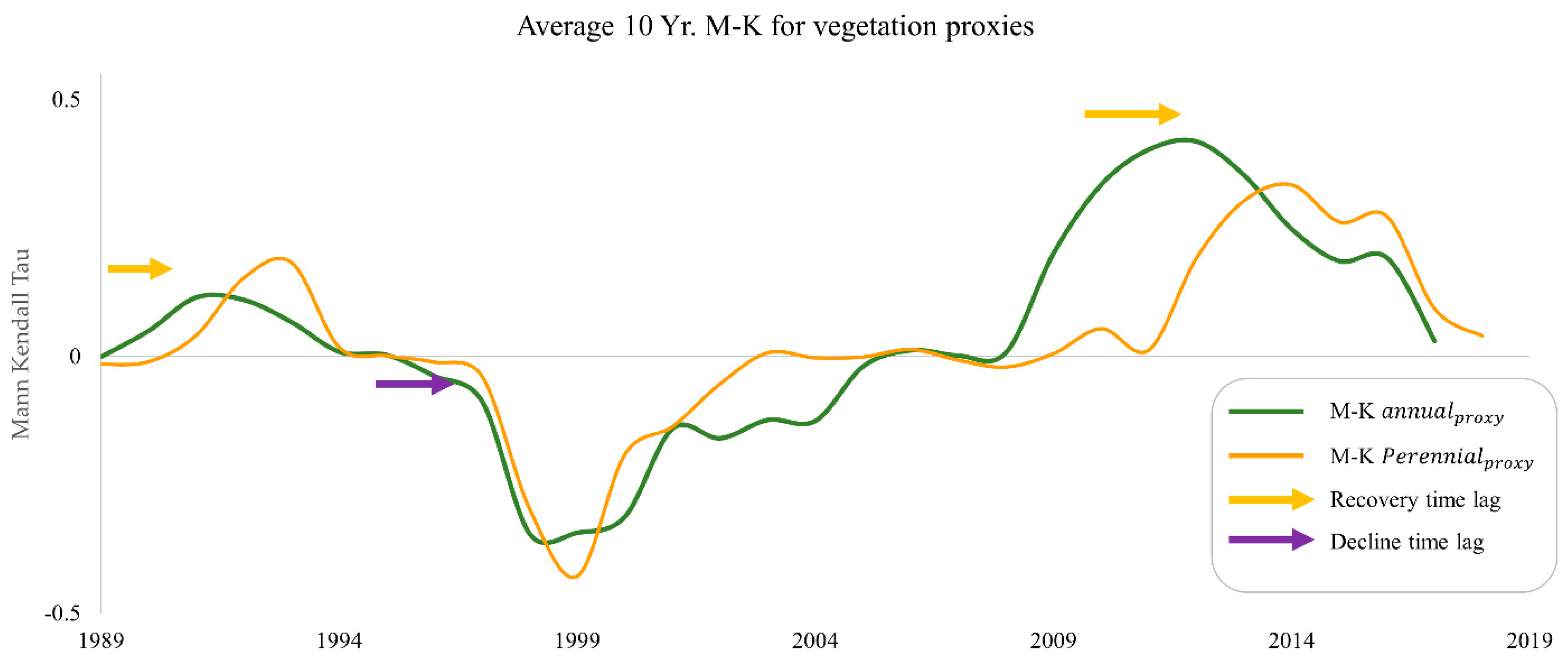

3.3. The Medium- and Long-Term Trends of the Vegetation

3.3.1. Time Lags in the Recovery and Decline of NDVI Proxies

| Trend | M-K annualprox | M-K perennialprox |

|---|---|---|

| Positive | 1989- 1995 | 1991- 1995 |

| Negative | 1996-2005 | 1997-2003 |

| Positive | 2008-2017 | 2011-2018 |

3.4. Differences in Vegetation Cover Affected by Land Management

4. Discussion

4.1. Climatic Trend and Sub-Periods in the Arava Valley

4.2. The Spatial Correlation between Rainfall and Vegetation Proxies

4.2.1. The Correlation between Rainfall and Vegetation Proxies

4.3. Vegetation Dynamics in Response to Rainfall Fluctuations

4.3.1. The Mann-Kendall Time Series Approach

4.3.2. Differences in the Recovery and Decline between the Vegetation Proxies

4.4. The Impact of Land Use

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kimura, R.; Moriyama, M. Recent Trends of Annual Aridity Indices and Classification of Arid Regions with Satellite-Based Aridity Indices. Remote Sensing in Earth Systems Sciences 2019, 2, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, T.; Williams, C.A.; De Kauwe, M.G.; Schwalm, C.R.; Medlyn, B.E. Patterns of Post-Drought Recovery Are Strongly Influenced by Drought Duration, Frequency, Post-Drought Wetness, and Bioclimatic Setting. Global Change Biology 2021, 27, 4630–4643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morin, E. To Know What We Cannot Know: Global Mapping of Minimal Detectable Absolute Trends in Annual Precipitation: MINIMAL DETECTABLE PRECIPITATION TRENDS. Water Resour. Res. 2011, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlow, M.; Zaitchik, B.; Paz, S.; Black, E.; Evans, J.; Hoell, A. A Review of Drought in the Middle East and Southwest Asia. Journal of Climate 2016, 29, 8547–8574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groner, E.; Babad, A.; Berda Swiderski, N.; Shachak, M. Toward an Extreme World: The Hyper-Arid Ecosystem as a Natural Model. Ecosphere 2023, 14, e4586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabari, H.; Willems, P. More Prolonged Droughts by the End of the Century in the Middle East. Environ. Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 104005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamdarloo, E.H.; Manesh, M.B.; Khosravi, H. Probability Assessment of Vegetation Vulnerability to Drought Based on Remote Sensing Data. Environ Monit Assess 2018, 190, 702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutterman, Y. Survival Strategies of Annual Desert Plants; Springer Science & Business Media, 2002; ISBN 978-3-540-43172-5.

- Peng, J.; Wu, C.; Zhang, X.; Wang, X.; Gonsamo, A. Satellite Detection of Cumulative and Lagged Effects of Drought on Autumn Leaf Senescence over the Northern Hemisphere. Global Change Biology 2019, 25, 2174–2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, A.; Yu, Q.; Feng, L.; Zhang, A.; Pei, T. Evaluating the Cumulative and Time-Lag Effects of Drought on Grassland Vegetation: A Case Study in the Chinese Loess Plateau. Journal of environmental management 2020, 261, 110214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Liu, H.; Li, X.; Ciais, P.; Babst, F.; Guo, W.; Zhang, C.; Magliulo, V.; Pavelka, M.; Liu, S.; et al. Differentiating Drought Legacy Effects on Vegetation Growth over the Temperate Northern Hemisphere. Global Change Biology 2018, 24, 504–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegal, Z.; Tsoar, H.; Karnieli, A. Effects of Prolonged Drought on the Vegetation Cover of Sand Dunes in the NW Negev Desert: Field Survey, Remote Sensing and Conceptual Modeling. Aeolian Research 2013, 9, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asner, G.P.; Elmore, A.J.; Olander, L.P.; Martin, R.E.; Harris, A.T. Grazing Systems, Ecosystem Responses, and Global Change. Annual Review of Environment and Resources 2004, 29, 261–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meroz, A.M.; Yin, H.; Levin, N. Unveiling the Impact of Traditional Land Practices on Natural Vegetation Using Large-Scale Exclosures: National Borders and Military Bases. Journal of Arid Environments 2023, 211, 104930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noy-Meir, I. Desert Ecosystems: Environment and Producers. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 1973, 4, 25–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otterman, J. Baring High-Albedo Soils by Overgrazing: A Hypothesized Desertification Mechanism. Science 1974, 186, 531–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seifan, M. Long-Term Effects of Anthropogenic Activities on Semi-Arid Sand Dunes. Journal of Arid Environments 2009, 73, 332–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WMO SPI: Standardized Precipitation Index; european commission, 2013.

- Ejaz, N.; Bahrawi, J. Assessment of Drought Severity and Their Spatio-Temporal Variations in the Hyper Arid Regions of Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: A Case Study from Al-Lith and Khafji Watersheds. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosravi, H.; Haydari, E.; Shekoohizadegan, S.; Zareie, S. Assessment the Effect of Drought on Vegetation in Desert Area Using Landsat Data. The Egyptian Journal of Remote Sensing and Space Science 2017, 20, S3–S12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAuliffe, J.R.; Hamerlynck, E.P. Perennial Plant Mortality in the Sonoran and Mojave Deserts in Response to Severe, Multi-Year Drought. Journal of Arid Environments 2010, 74, 885–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noy, K.; Ohana-Levi, N.; Panov, N.; Silver, M.; Karnieli, A. A Long-Term Spatiotemporal Analysis of Biocrusts across a Diverse Arid Environment: The Case of the Israeli-Egyptian Sandfield. Science of The Total Environment 2021, 774, 145154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, C.J. Red and Photographic Infrared Linear Combinations for Monitoring Vegetation. Remote Sensing of Environment 1979, 8, 127–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaacson, S.; Ephrath, J.E.; Rachmilevitch, S.; Maman, S.; Ginat, H.; Blumberg, D.G. Long and Short Term Population Dynamics of Acacia Trees via Remote Sensing and Spatial Analysis: Case Study in the Southern Negev Desert. Remote Sensing of Environment 2017, 198, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnieli, A.; Gilad, U.; Ponzet, M.; Svoray, T.; Mirzadinov, R.; Fedorina, O. Assessing Land-Cover Change and Degradation in the Central Asian Deserts Using Satellite Image Processing and Geostatistical Methods. Journal of Arid Environments 2008, 72, 2093–2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewińska, K.E.; Ives, A.R.; Morrow, C.J.; Rogova, N.; Yin, H.; Elsen, P.R.; de Beurs, K.; Hostert, P.; Radeloff, V.C. Beyond “Greening” and “Browning”: Trends in Grassland Ground Cover Fractions across Eurasia That Account for Spatial and Temporal Autocorrelation. Global Change Biology 2023, n/a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chávez, R.O.; Moreira-Muñoz, A.; Galleguillos, M.; Olea, M.; Aguayo, J.; Latín, A.; Aguilera-Betti, I.; Muñoz, A.A.; Manríquez, H. GIMMS NDVI Time Series Reveal the Extent, Duration, and Intensity of “Blooming Desert” Events in the Hyper-Arid Atacama Desert, Northern Chile. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 2019, 76, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruins, H.J.; Sherzer, Z.; Ginat, H.; Batarseh, S. Degradation of Springs in the Arava Valley: Anthropogenic and Climatic Factors. Land Degradation & Development 2012, 23, 365–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armoza-Zvuloni, R.; Shlomi, Y.; Shem-Tov, R.; Stavi, I.; Abadi, I. Drought and Anthropogenic Effects on Acacia Populations: A Case Study from the Hyper-Arid Southern Israel. Soil Systems 2021, 5, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginat, H.; Shlomi, Y.; Batarseh, S.; Vogel, J. REDUCTION IN PRECIPITATION LEVELS IN THE ARAVA VALLEY (SOUTHERN ISRAEL AND JORDAN), 1949-2009. Journal of Dead-Sea and Arava Research 2011, 3, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Saaroni, H.; Ziv, B.; fregmant, R.; Halfon, N. Fluctuations in the Negev rains in the last fifty years - Is there evidence of climate change? Ecology & Environment 2012, 3, 62–72. [Google Scholar]

- Babad, A.; Silver, M. Is there a trend of change in the amount of precipitation in the high Negev? Dead Sea and science center 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Franklin, J.F. Importance and Justification of Long-Term Studies in Ecology. In Long-Term Studies in Ecology: Approaches and Alternatives; Likens, G.E., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, 1989; pp. 3–19. ISBN 978-1-4615-7358-6. [Google Scholar]

- Tielbörger, K.; Bilton, M.C.; Metz, J.; Kigel, J.; Holzapfel, C.; Lebrija-Trejos, E.; Konsens, I.; Parag, H.A.; Sternberg, M. Middle-Eastern Plant Communities Tolerate 9 Years of Drought in a Multi-Site Climate Manipulation Experiment. Nat Commun 2014, 5, 5102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.; Cao, L.; Zhong, S.; Liu, G.; Yang, Y.; Zhu, S.; Luo, X.; Di, L. Trends in Global Vegetative Drought From Long-Term Satellite Remote Sensing Data. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing 2020, 13, 815–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziv, B.; Saaroni, H.; Pargament, R.; Harpaz, T.; Alpert, P. Trends in Rainfall Regime over Israel, 1975–2010, and Their Relationship to Large-Scale Variability. Reg Environ Change 2014, 14, 1751–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danin, A. Flora and Vegetation of Israel and Adjacent Areas. herbmedit 1988, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Raunkiær, C. The Life Forms of Plants and Statistical Plant Geography Being the Collected Papers of C. Raunkiaer; Oxford at the Clarendon Press, 1934.

- Brown, J.H.; Ernest, S.K.M. Rain and Rodents: Complex Dynamics of Desert Consumers. BioScience 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.O.; Ustin, S.L.; Adams, J.B.; Gillespie, A.R. Vegetation in Deserts: II. Environmental Influences on Regional Abundance. Remote Sensing of Environment 1990, 31, 27–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AQUASTAT (FAO) Map of Aridity (Global - ~19km) 2023.

- Spinoni, J.; Micale, F.; Carrao, H.; Naumann, G.; Barbosa, P.; Vogt, J. Global and Continental Changes of Arid Areas Using the FAO Aridity Index over the Periods 1951-1980 and 1981-2010. 2013, EGU2013-9262.

- Lehner, B.; Grill, G. Global River Hydrography and Network Routing: Baseline Data and New Approaches to Study the World’s Large River Systems. Hydrological Processes 2013, 27, 2171–2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ESRI ESRI Land Use Land Cover 2020.

- Avni, Y.; Bartov, Y.; Garfunkel, Z.; Ginat, H. The Arava Formation-A Pliocene Sequence in the Arava Valley and Its Western Margin, Southern Israel. Israel Journal of Earth Sciences 2001, 50, 101–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porat, N.; Amit, R.; Zilberman, E.; Enzel, Y. Luminescence Dating of Fault-Related Alluvial Fan Sediments in the Southern Arava Valley, Israel. Quaternary Science Reviews 1997, 16, 397–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahana, R.; Ziv, B.; Enzel, Y.; Dayan, U. Synoptic Climatology of Major Floods in the Negev Desert, Israel. International Journal of Climatology 2002, 22, 867–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krichak, S.O.; Alpert, P.; Krishnamurti, T.N. Red Sea Trough/Cyclone Development — Numerical Investigation. Meteorl. Atmos. Phys. 1997, 63, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drori, R.; Ziv, B.; Saaroni, H.; Etkin, A.; Sheffer, E. Recent Changes in the Rain Regime over the Mediterranean Climate Region of Israel. Climatic Change 2021, 167, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldreich, Y.; Karni, O. Climate and Precipitation Regime in the Arava Valley, Israel. Israel Journal of Earth Sciences 2001, 50, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifan, M.; Zohar, Y.; Werner, Y.L. Reptile Distribution May Identify Terrestrial Islands for Conservation: The Levant’s ‘Arava Valley as a Model. Journal of Natural History 2016, 50, 2783–2801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frumkin, R.; Pinshow, B.; Kleinhaus, S. A Review of Bird Migration over Israel. J Ornithol 1995, 136, 127–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordo, O.; Sanz, J.J. The Relative Importance of Conditions in Wintering and Passage Areas on Spring Arrival Dates: The Case of Long-Distance Iberian Migrants. J Ornithol 2008, 149, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, M.G. Rank Correlation Methods; Rank correlation methods; Griffin: Oxford, England, 1948. [Google Scholar]

- Mann, H.B. Nonparametric Tests Against Trend. Econometrica 1945, 13, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neeti, N.; Eastman, J.R. A Contextual Mann-Kendall Approach for the Assessment of Trend Significance in Image Time Series. Transactions in GIS 2011, 15, 599–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.N.; Murthy, C.S.; Sai, M.V.R.S.; Roy, P.S. On the Use of Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI) for Drought Intensity Assessment. Meteorological Applications 2009, 16, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryee, J.N.A. Climate Indices/ SPI Calculation. Available online: https://github.com/jeffjay88/Climate_Indices/blob/main/1D_spi_pandas.ipynb (accessed on 3 September 2023).

- McKee, T.B.; Doesken, N.J.; Kleist, J. THE RELATIONSHIP OF DROUGHT FREQUENCY AND DURATION TO TIME SCALES. 1993, 6.

- Svoboda, M.; Hayes, M.; Wood, D. Standardized Precipitation Index User Guide; 2012; p. 25.

- Huete, A.R. A Soil-Adjusted Vegetation Index (SAVI). Remote Sensing of Environment 1988, 25, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq Ahmad Spectral Vegetation Indices Performance Evaluated for Cholistan Desert. J. Geogr. Reg. Plann. 2012, 5. [CrossRef]

- Masek, J.G.; Vermote, E.F.; Saleous, N.E.; Wolfe, R.; Hall, F.G.; Huemmrich, K.F.; Gao, F.; Kutler, J.; Lim, T.-K. A Landsat Surface Reflectance Dataset for North America, 1990-2000. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters 2006, 3, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermote, E.; Justice, C.; Claverie, M.; Franch, B. Preliminary Analysis of the Performance of the Landsat 8/OLI Land Surface Reflectance Product. Remote Sensing of Environment 2016, 185, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venter, Z.S.; Barton, D.N.; Chakraborty, T.; Simensen, T.; Singh, G. Global 10 m Land Use Land Cover Datasets: A Comparison of Dynamic World, World Cover and Esri Land Cover. Remote Sensing 2022, 14, 4101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danin, A. The vegetation of the Negev (North of Nahal Paran). Poaliim 1977.

- Danin, A.; Orshan, G. The Distribution of Raunkiaer Life Forms in Israel in Relation to the Environment. Journal of Vegetation Science 1990, 1, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, H.; Karnieli, A. Remote Sensing of the Seasonal Variability of Vegetation in a Semi-Arid Environment. Journal of Arid Environments 2000, 45, 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, N. Human Factors Explain the Majority of MODIS-Derived Trends in Vegetation Cover in Israel: A Densely Populated Country in the Eastern Mediterranean. Reg Environ Change 2016, 16, 1197–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehner, B.; Verdin, K.; Jarvis, A. New Global Hydrography Derived From Spaceborne Elevation Data. Eos, Transactions American Geophysical Union 2008, 89, 93–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albalawneh, A.; Al-Assaf, A.; Sweity, A.; Hammour, W.A.; Kloub, K.; Hjazin, A.; Kabariti, R.; Abu Nowar, L.; Tadros, M.J.; Aljaafreh, S.; et al. Mapping Cultural Ecosystem Services in the Hyper Arid Environment of South of Jordan. Frontiers in Environmental Science 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albalawneh, A.; Nawash, O.; Al-Assaf, A.; Hjazin, A.; Tadros, M.; Kabariti, R.; Nowar, L.A.; Albashbsheh, G.; Diab, M.; Aljaafreh, S.; et al. Traditional Knowledge of Wild Plant Species Used by Local People Inhabiting the Southern Part of Wadi Araba Desert in South-West Jordan; In Review, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Sneh, A.; Bartov, Y.; Weissbrod, T; Rosensaft, M Geological Map of Israel, 1:200,000 1998.

- Ben-Gai, T.; Bitan, A.; Manes, A.; Alpert, P. Long-Term Changes in Annual Rainfall Patterns in Southern Israel. Theor Appl Climatol 1994, 49, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, Z.; Halfon, N.; Alpert, P. Reassessment of Rain Enhancement Experiments and Operations in Israel Including Synoptic Considerations. Atmospheric Research 2010, 97, 513–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaroni, H.; Halfon, N.; Ziv, B.; Alpert, P.; Kutiel, H. Links between the rainfall regime in Israel and location and intensity of Cyprus lows. International Journal of Climatology 2010, 30, 1014–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yosef, Y.; Saaroni, H.; Alpert, P. Trends in Daily Rainfall Intensity Over Israel 1950/1-2003/4. The Open Atmospheric Science Journal 2009, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yosef, Y.; Aguilar, E.; Alpert, P. Changes in Extreme Temperature and Precipitation Indices: Using an Innovative Daily Homogenized Database in Israel. Int J Climatol 2019, 39, 5022–5045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochman, A.; Harpaz, T.; Saaroni, H.; Alpert, P. The Seasons’ Length in 21st Century CMIP5 Projections over the Eastern Mediterranean. International Journal of Climatology 2018, 38, 2627–2637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luković, J.; Bajat, B.; Blagojević, D.; Kilibarda, M. Spatial Pattern of Recent Rainfall Trends in Serbia (1961–2009). Reg Environ Change 2014, 14, 1789–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.; Roderick, M.L.; Farquhar, G.D. Rainfall Statistics, Stationarity, and Climate Change. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2018, 115, 2305–2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crawford, C.S.; Gosz, J.R. Desert Ecosystems: Their Resources in Space and Time. Environmental Conservation 1982, 9, 181–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, M.; Tavili, A.; Panahi, F.; Zandi Esfahan, E.; Ghorbani, M. Characteristics of Arid and Desert Ecosystems. In Reclamation of Arid Lands; Jafari, M., Tavili, A., Panahi, F., Zandi Esfahan, E., Ghorbani, M., Eds.; Environmental Science and Engineering; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2018; pp. 21–91. ISBN 978-3-319-54828-9. [Google Scholar]

- Casenave, A.; Valentin, C. A Runoff Capability Classification System Based on Surface Features Criteria in Semi-Arid Areas of West Africa. Journal of Hydrology 1992, 130, 231–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E. Zilberman,; Y. Avni; A. Sneh The Nizzana Sheet 2014.

- Wieler, N. Geological and Microbiological Features of Rock Weathering in Arid Environments, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev: Beer-Sheva, 2018.

- Schmiedel, U.; Jacke, V.; Hachfeld, B.; Oldeland, J. Response of Kalahari Vegetation to Seasonal Climate and Herbivory: Results of 15 Years of Vegetation Monitoring. Journal of Vegetation Science 2021, 32, e12927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozenstein, O.; Agam, N.; Serio, C.; Masiello, G.; Venafra, S.; Achal, S.; Puckrin, E.; Karnieli, A. Diurnal Emissivity Dynamics in Bare versus Biocrusted Sand Dunes. Science of The Total Environment 2015, 506–507, 422–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saltz, D.; Schmidt, H.; Rowen, M.; Karnieli, A.; Ward, D.; Schmidt, I. Assessing Grazing Impacts by Remote Sensing in Hyper-Arid Environments. Journal of Range Management 1999, 52, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q. Slow Recovery in Desert Perennial Vegetation Following Prolonged Human Disturbance. Journal of Vegetation Science 2004, 15, 757–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, N.; Ben dor, E.; Kidron, G. The influence of human factors on the temporal changes in the stabilization rate of the Ashdod-Nizzanim sand dune. Tel Aviv 2003. [Google Scholar]

| SPI values | Drought and humid category |

|---|---|

| ≥ (+) 2 | Extreme wet |

| (+) 1.5 to (+) 1.99 | Very wet |

| (+) 1 to (+) 1.49 | Moderate wet |

| 0 to (+) 0.99 | Mild wet |

| 0 to (-) 0.99 | Mild drought |

| (-) 1 to (-) 1.49 | Moderate drought |

| (-) 1.5 to (-) 1.99 | Severe drought |

| ≤ (-) 2 | Extreme drought |

| Correlations for monthly rainfall | Correlations for SPI | ||||

| Eilat | Yotveta | Hatzeva | Sdom | ||

| Eilat | 0.77* | 0.55* | -0.07 | ||

| Yotveta | 0.64* | 0.61* | 0.03 | ||

| Hatzeva | 0.58* | 0.53* | 0.48* | ||

| Sdom | 0.28 | 0.30 | 0.37 | ||

| Rain stations | Prior to the Landsat time series | During the Landsat time series | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eilat | Wet 1952-1957 |

Dry 1958-1964 |

Wet 1965-1971, 1973-1978 |

Wet 1987-1990 |

Dry 1996-2014 |

Wet 2017-2023 |

| Yotveta | Dry 1958-1965 |

Dry 1978-1980 |

Wet 1985-1997 |

Dry 2003-2014 |

Wet 2015-2023 |

|

| Hatzeva | Wet 1987-1993 |

Dry 1998-2005, 2008-2014 |

Wet 2015-2022 |

|||

| Sdom | Wet 1968-1971 1972-1977 |

Dry 1978-1986 |

Dry 1997-2004 |

Wet 2005-2013, 2015-2021 |

||

| perennialprox | |||||

| annualprox | Stations | Eilat | Yotveta | Hatzeva | Sdom |

| Eilat | 0.97* | 0.94* | 0.89* | ||

| Yotveta | 0.86* | 0.98* | 0.95* | ||

| Hatzeva | 0.78* | 0.97* | 0.97* | ||

| Sdom | 0.53* | 0.76* | 0.85* | ||

| Rainfall | Vegetation proxy | Eilat | Yotveta | Hatzeva | Sdom |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yearly rainfall | annualprox | 0.26 | 0.56* | 0.48* | 0.27 |

| 2 Yr. average rainfall | 0.36* | 0.65* | 0.64* | 0.33 | |

| 3 Yr. average rainfall | 0.44* | 0.62* | 0.65* | 0.46* | |

| 4 Yr. average rainfall | 0.17 | 0.55* | 0.52* | 0.26 | |

| Yearly rainfall | perennialprox | 0.31 | 0.43* | 0.55** | 0.25* |

| 2 Yr. average rainfall | 0.45* | 0.50* | 0.73* | 0.38* | |

| 3 Yr. average rainfall | 0.49* | 0.53* | 0.79* | 0.44* | |

| 4 Yr. average rainfall | 0.52* | 0.54* | 0.73* | 0.53* | |

| 5 Yr. average rainfall | 0.57* | 0.54* | 0.70* | 0.35 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).