Submitted:

16 February 2024

Posted:

19 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction.

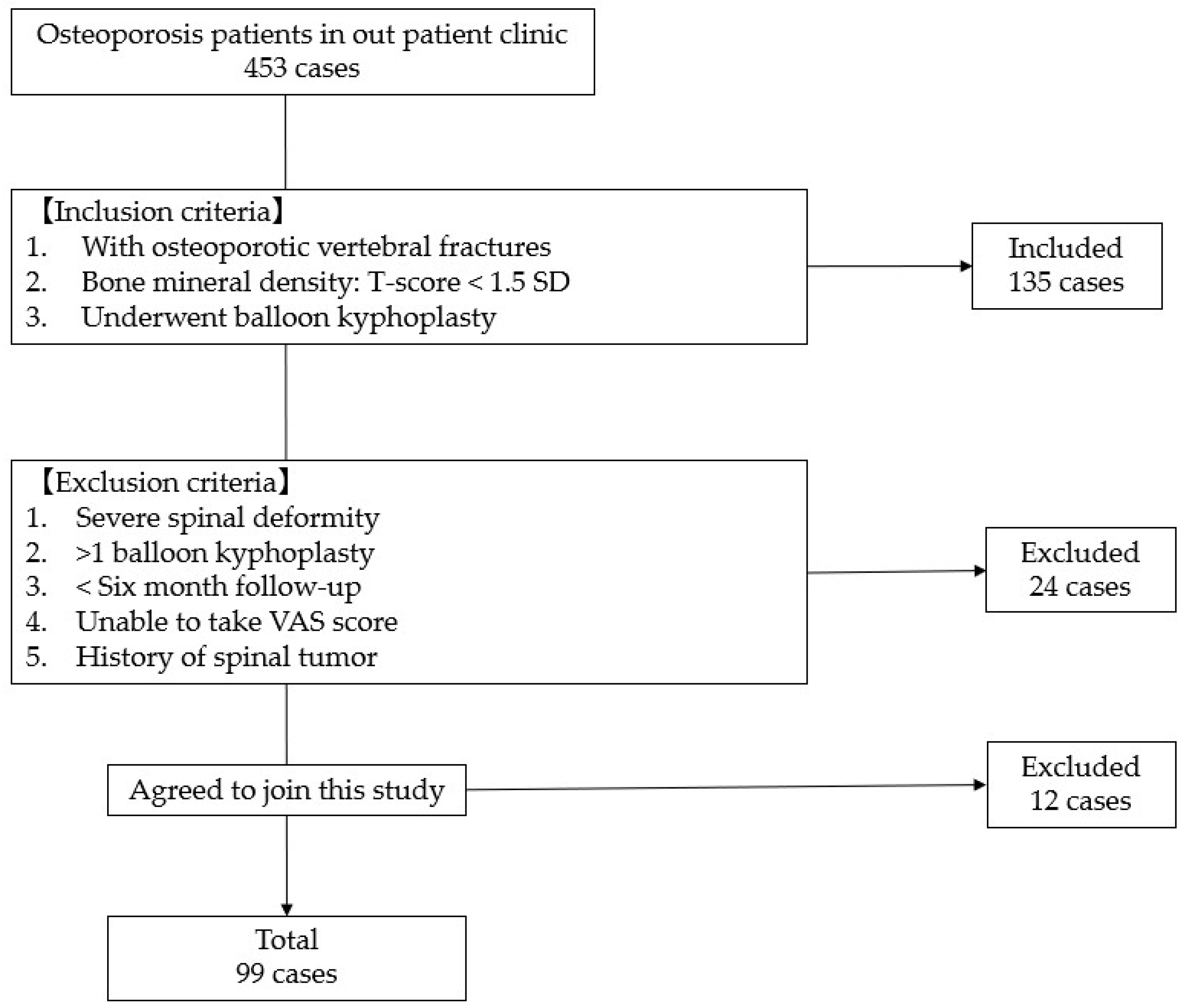

2. Materials and Methods

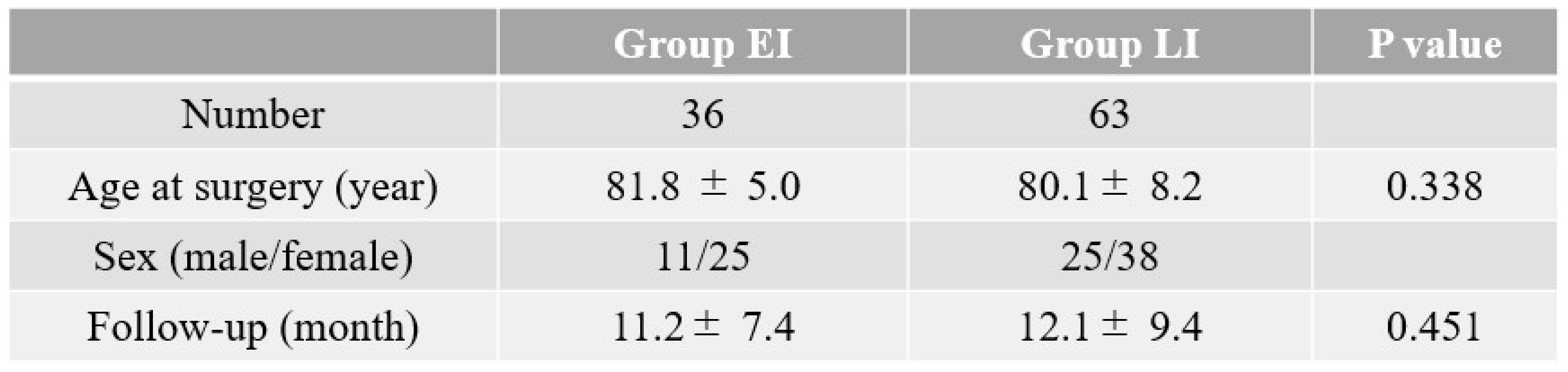

2.1. Clinical evaluation

2.2. Radiological evaluation

2.3. Statistical evaluation

2.4. Surgery.

3. Results.

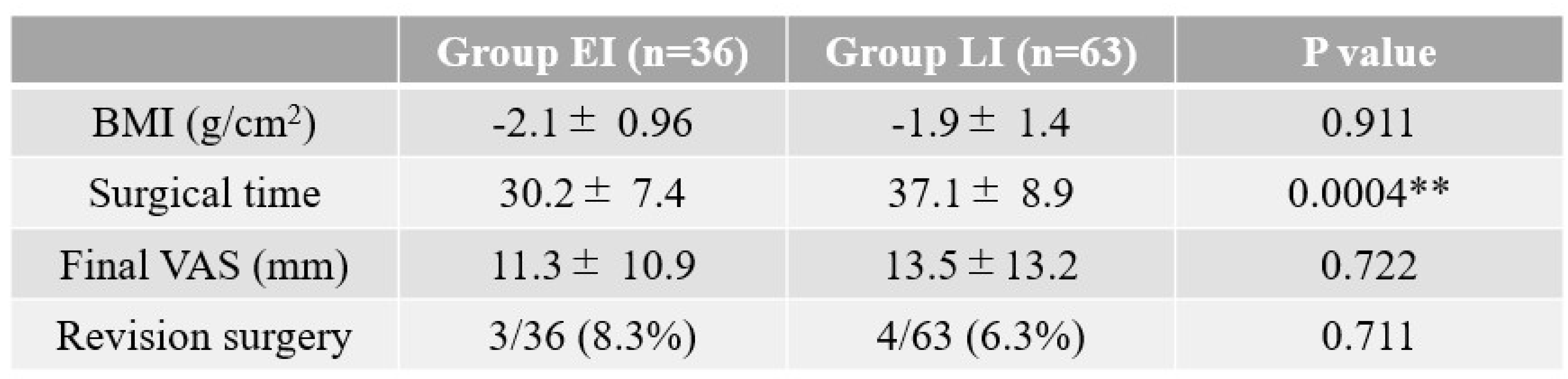

3.1. Clinical results

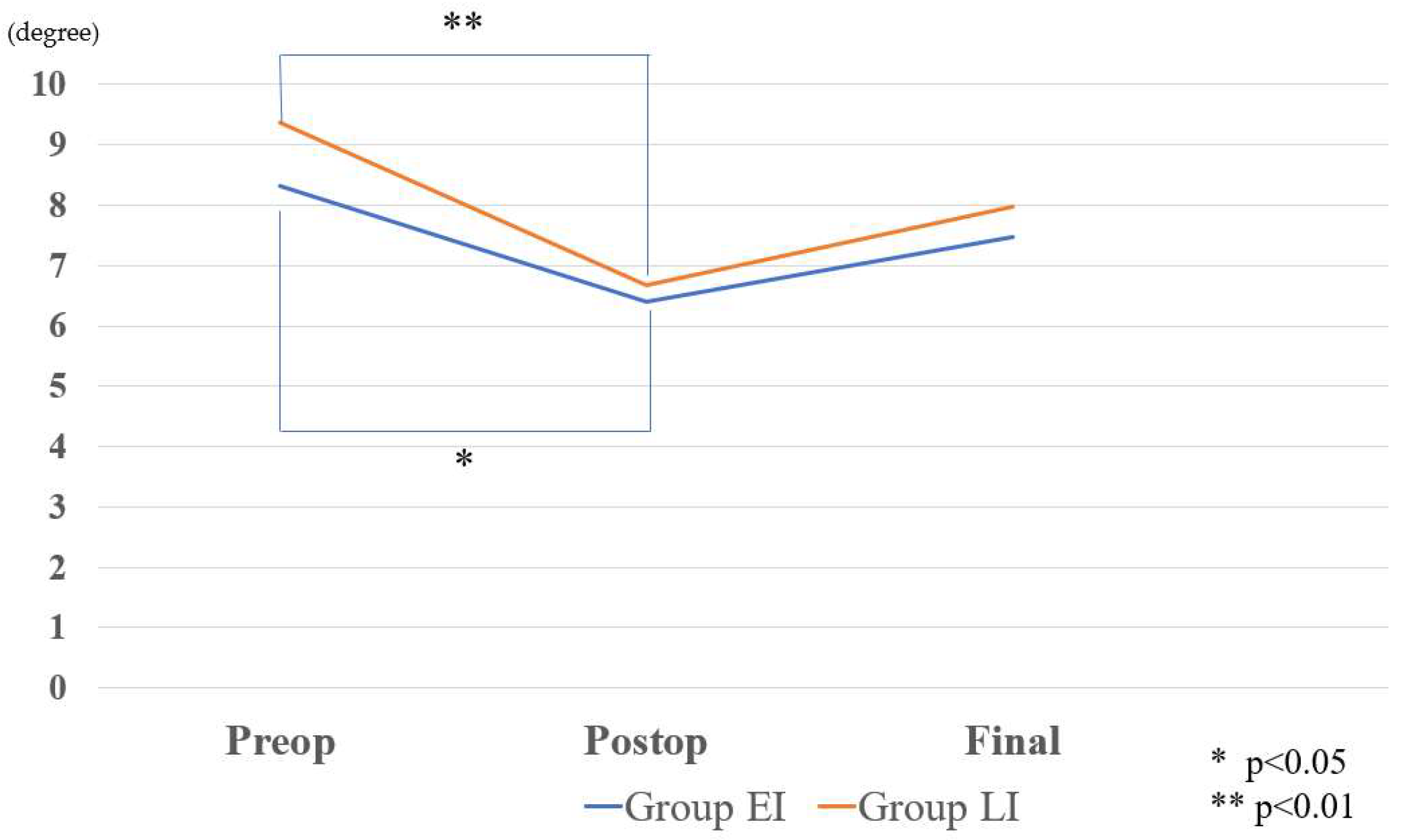

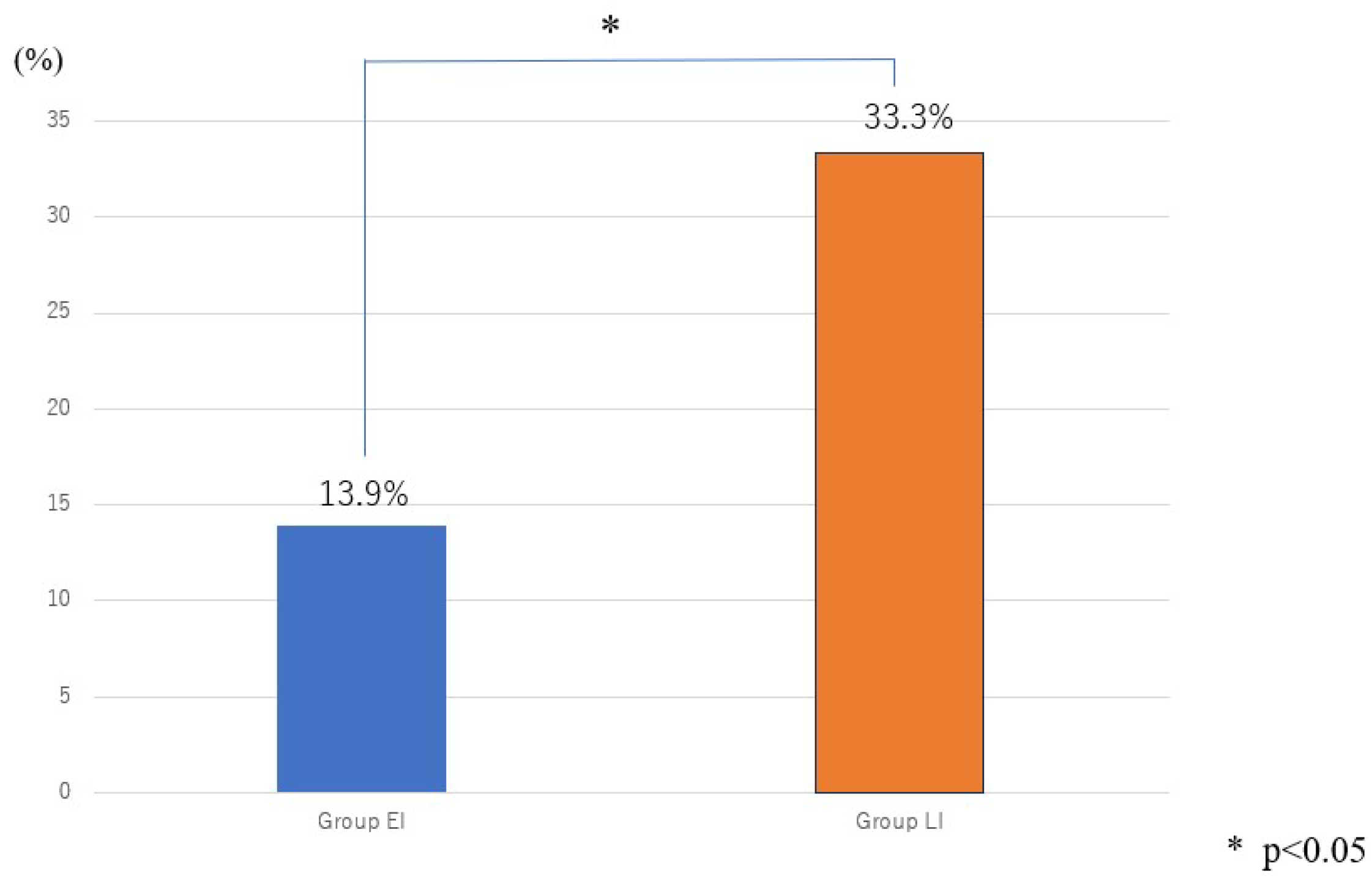

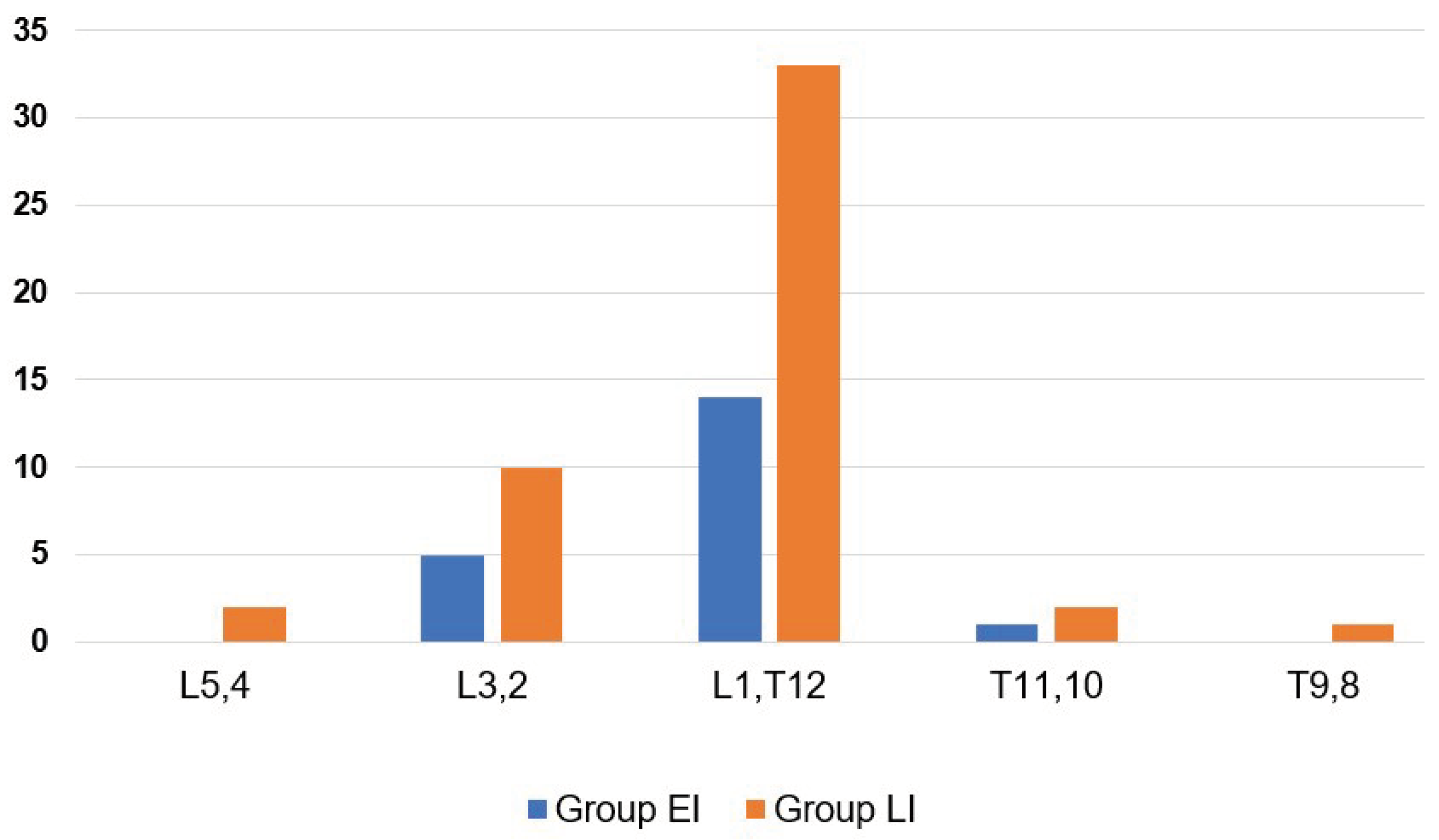

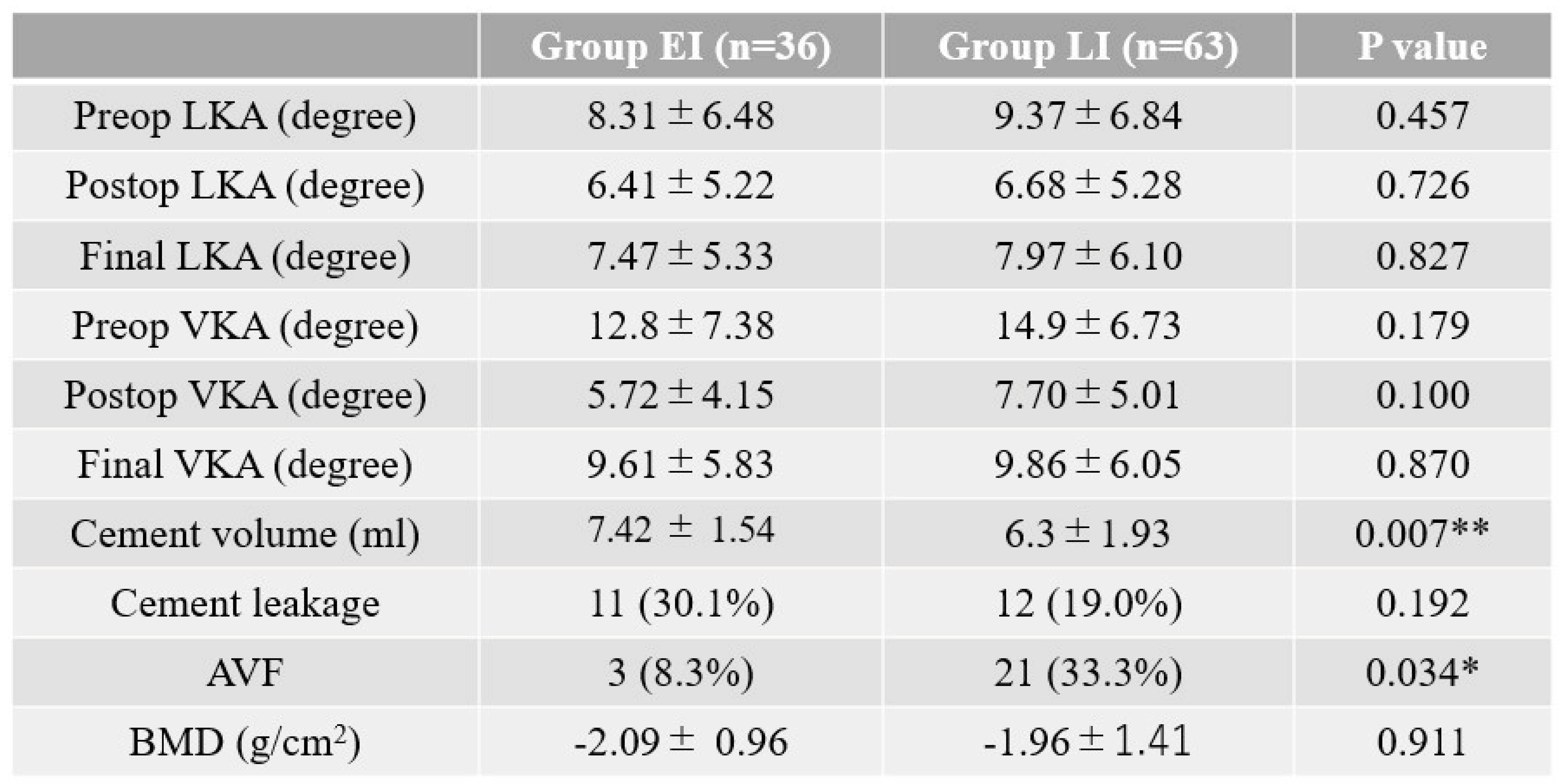

3.2. Radiographic results

4. Discussion

Conclusions

References

- Reginster JY, Burlet N. Osteoporosis: A still increasing prevalence. Bone 2006; 38:S4-S9. [CrossRef]

- Ploeg WT, Veldhuizen AG, The B, Sietsma MS. Percutaneous vertebroplasty as a treatment for osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures: A systematic review. Eur Spine J 2006; 15:1749-1758. [CrossRef]

- Johnell O. Advances in osteoporosis: Better identification of risk factors can reduce morbidity and mortality. J Intern Med 1996; 239:299-304. [CrossRef]

- Minamide A, Maeda T, Yamada H, et al. Early versus delayed kyphoplasty for thoracolumbar osteoporotic vertebral fractures: The effect of timing on clinical and radiographic outcomes and subsequent compression fractures. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2018; 173:176-181. [CrossRef]

- to Y, Hasegawa Y, Toda K, Nakahara S. Pathogenesis, and diagnosis of delayed vertebral collapse resulting from osteoporotic spinal fracture. Spine J 2002; 2:101-106. [CrossRef]

- Takahashi S, Hoshino M, Terai H, et al. Differences in short-term clinical and radiological outcomes depending on timing of balloon kyphoplasty for painful osteoporotic vertebral fracture. J Orthop Sci 2018; 23:51-56. [CrossRef]

- Garfin SR, Yuan HA, Reiley MA. New technologies in spine: Kyphoplasty and vertebroplasty for the treatment of painful osteoporotic compression fractures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2001; 26:1511-1515.

- Oh GS, Kim HS, Ju CI, Kim SW, Lee SM, Shin H. Comparison of the results of balloon kyphoplasty performed at different times after injury. J Korean Neurosurg Soc 2010; 47:199-202. [CrossRef]

- Klazen CA, Lohle PN, de Vries J, et al. Vertebroplasty versus conservative treatment in acute osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures (Vertos II): An open-label randomised trial. Lancet 2010; 376:1085-1092. [CrossRef]

- Edidin AA, Ong KL, Lau E, Kurtz SM. Morbidity, and mortality after vertebral fractures: Comparison of vertebral augmentation and nonoperative management in the Medicare population. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2015; 40:1228-1241.

- Liu D, Xu J, Wang Q, Zhang L, Yin S, Qian B, Li X, Wen T, Jia Z. Timing of Percutaneous Balloon Kyphoplasty for Osteoporotic Vertebral Compression Fractures. Pain Physician. 2023 May;26(3):231-243.

- Kanis JA, Harvey NC, McCloskey E, et al. Algorithm for the management of patients at low, high, and very high risk of osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int 2020; 31:1-12. [CrossRef]

- Zhou X, Meng X, Zhu H, Zhu Y, Yuan W. Early versus late percutaneous kyphoplasty for treating osteoporotic vertebral compression fracture: A retrospective study. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2019; 180:101-105. [CrossRef]

- Goldstein S, Smorgick Y, Mirovsky Y, Anekstein Y, Blecher R, Tal S. Clinical and radiological factors affecting progressive collapse of acute osteoporotic compression spinal fractures. J Clin Neurosci. 2016 Sep;31:122-6. [CrossRef]

- B. Garg, V. Dixit, S. Batra, R. Malhotra, and A. Sharan, “Non-surgical management of acute osteoporotic vertebral compression fracture: a review,” Journal of Clinical Orthopaedics and Trauma, vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 131–138, 2017. [CrossRef]

- N. Evaniew, “Vertebral augmentation for osteoporotic compression fractures: review of the fracture reduction evaluation trial,” Journal of Long-Term Effects of Medical Implants, vol. 26, no. 3, pp. 205–208, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Zhang T, Peng Y, Li J. Comparison of clinical and radiological outcomes of vertebral body stenting versus percutaneous kyphoplasty for the treatment of osteoporotic vertebral compression fracture: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Jt Dis Relat Surg. 2024 Jan 1;35(1):218-230. [CrossRef]

- R. Rousing, K. L. Hansen, M. O. Andersen, S. M. Jespersen, K. Thomsen, and J. M. Lauritsen, “Twelve-months follow-up in forty-nine patients with acute/semiacute osteoporotic vertebral fractures treated conservatively or with percutaneous vertebroplasty: a clinical randomized study,” Spine (Phila Pa 1976), vol. 35, no. 5, pp. 478–482, 2010.

- J. Berenson, R. Pflugmacher, P. Jarzem et al., “Balloon kyphoplasty versus non-surgical fracture management for treatment of painful vertebral body compression fractures in patients with cancer: a multicentre, randomised controlled trial,” The Lancet Oncology, vol. 12, no. 3, pp. 225–235, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Cooper, C., Atkinson, E. J., O'Fallon, W. M., & Melton, L. J. (1992). Incidence of clinically diagnosed vertebral fractures: a population-based study in Rochester, Minnesota, 1985-1989. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research, 7(2), 221-227.

- Son HJ, Park SJ, Kim JK, Park JS. Mortality risk after the first occurrence of osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures in the general population: A nationwide cohort study. PLoS One. 2023 Sep 14;18(9):e0291561. [CrossRef]

- Patel, N., Jacobs, D., John, J. K., Fayed, M., Nerusu, L., Tandron, M., ... & Aiyer, R. (2022). Balloon Kyphoplasty vs Vertebroplasty: A Systematic Review of Height Restoration in Osteoporotic Vertebral Compression Fractures. Journal of Pain Research, 15, 1233-1245. [CrossRef]

- Kallmes DF, Schweickert PA, Marx WF, et al. Vertebroplasty in the mid- and upper thoracic spine. AJNR Am J Neu- orodadiol. 2002 23(7):1117–112026. Kim D, Yun Y, Wang J. Nerve root injections for the relief of pain in patients with osteoporotic vertebral fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2003 85B(2):250–253.

- Cosman F, de Beur SJ, LeBoff MS, Lewiecki EM, Tanner B, Randall S, Lindsay R, National Osteoporosis F (2014) Clinician's guide to prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 25:2359–2381.

- Kanis JA, Cooper C, Rizzoli R, Reginster JY (2019) Scientific advisory board of the European society for C, Economic aspects of O, the committees of Scientific A, national societies of the international osteoporosis F European guidance for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int 30:3–44.

- H. Guan, H. Yang, X. Mei, T. Liu, and J. Guo, “Early or delayed operation, which is more optimal for kyphoplasty? A retrospective study on cement leakage during kyphoplasty,” Injury, vol. 43, no. 10, pp. 1698–1703, 2012. [CrossRef]

- G. Baroud and M. Bohner, “Biomechanical impact of vertebroplasty,” Joint Bone Spine, vol. 73, no. 2, pp. 144–150, 2006. [CrossRef]

- G. Zhao, X. Liu, and F. Li, “Balloon kyphoplasty versus percutaneous vertebroplasty for treatment of osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures (OVCFs),” Osteoporosis International: a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA, vol. 27, no. 9, pp. 2823–2834, 2016.

- Li, Y., Tao, W., Wan, Q., Li, Q., Yang, Y., Lin, Y., Zhang, S., & Li, W. (2015). Erratum for Jiang et al., Zoonotic and Potentially Host-Adapted Enterocytozoon bieneusi Genotypes in Sheep and Cattle in Northeast China and an Increasing Concern about the Zoonotic Importance of Previously Considered Ruminant-Adapted Genotypes. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 81, 5278-5278. [CrossRef]

- C. C. Yang, J. T. Chien, T. Y. Tsai, K. T. Yeh, R. P. Lee, and W. T. Wu, “Earlier vertebroplasty for osteoporotic thoracolumbar compression fracture may minimize the subsequent development of adjacent fractures: a retrospective study,” Pain Physician, vol. 21, no. 5, pp. E483–e491, 2018.

- He B, Zhao J, Zhang M, Jiang G, Tang K, Quan Z. Effect of Surgical Timing on the Refracture Rate after Percutaneous Vertebroplasty: A Retrospective Analysis of at Least 4-Year Follow-Up. Biomed Res Int. 2021 Nov 27;2021:5503022. [CrossRef]

- Taylor RS, Taylor RJ, Fritzell P. Balloon kyphoplasty and vertebroplasty for vertebral compression fractures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) November 2006;31(23):2747e55. [CrossRef]

- Ma, X., Sun, H., Liu, S., Sang, L., Wang, K., Dong, Y., & Qi, X. (2022). Cement Leakage in Vertebral Compression Fractures Between Unilateral and Bilateral Percutaneous Vertebral Augmentation: A Meta-Analysis. Turkish Neurosurgery.

- Y.J. Chen, W.H. Chen, H.T. Chen, H.C. Hsu, Repeat needle insertion in vertebro- plasty to prevent re-collapse of the treated vertebrae, Eur. J. Radiol. 81 (2012) 558–561.

- Y. Kishikawa, Initial non-weight-bearing therapy is important for preventing ver- tebral body collapse in elderly patients with clinical vertebral fractures, Int. J. Gen. Med. 5 (2012) 373–380.

- Park HTL, Lee CB, Ha JH, Choi SJ, Kim MS, Ha JM (2010) Results of kyphoplasty according to the operative timing. Current Orthopaedic Practice 21:489–493.

- L D. Crandall, D. Slaughter, P.J. Hankins, C. Moore, J. Jerman, Acute versus chronic vertebral compression fractures treated with kyphoplasty: early results, Spine J. 4 (2004) 418–424.

- S. Erkan, T.R. Ozalp, H.S. Yercan, G. Okcu, Does timing matter in performing ky- phoplasty? Acute versus chronic compression fractures, Acta Orthop. Belg. 75 (2009) 396–404.

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).