1. Introduction

Melatonin (

N-acetyl-5-methoxytryptamine), which is an indole hormone commonly found in animals, plants, and microorganisms, was first detected in plants in 1995 [

1,

2]. Numerous studies have demonstrated that melatonin plays a significant role in regulating various plant growth and developmental processes, including seed germination, root development, leaf senescence, flower development, fruit maturation, fruit storage, and seedling growth [

3,

4]. Moreover, melatonin can function as an antioxidant, thereby enhancing plant tolerance to abiotic stresses (e.g., drought, salinity, alkalinity, and temperature extremes) [

5,

6]. Thus, it may be useful for improving future agricultural production. However, most of the physiological effects of melatonin were determined via the administration of exogenous melatonin. Although plants can increase their endogenous melatonin levels by absorbing exogenous melatonin, the effects of exogenous and endogenous melatonin may differ [

5,

7]. Accordingly, plant melatonin synthase genes will need to be identified and functionally characterized to more comprehensively elucidate endogenous melatonin effects.

Phytomelatonin biosynthesis involves four main pathways, all of which require tryptophan as the initial substrate and at least six enzymes, namely tryptophan decarboxylase (TDC), tryptophan hydroxylase (TPH), tryptamine 5-hydroxylase (T5H), serotonin N-acetyltransferase (SNAT), N-acetylserotonin methyltransferase (ASMT), and caffeic-O-methyltransferase (COMT) [

8,

9]. Among these enzymes, TDC belongs to a group of aromatic-L-amino acid decarboxylases (AADCs), which catalyze the conversion of aromatic L-amino acids to aromatic monoamines and play a crucial role in the synthesis of secondary metabolites in plants [

10]. Two important AADCs in plants are TDC and tyrosine decarboxylase (TyrDC) [

11], of which TDC uses tryptophan as a substrate, whereas TyrDC uses tyrosine, but both enzymes are involved in the synthesis of various alkaloid metabolites [

10,

12]. Additionally, TDC is responsible for catalyzing the rate-limiting reaction during the synthesis of melatonin. More specifically, in the first enzymatic reaction leading to the synthesis of melatonin, tryptophan is decarboxylated by TDC, resulting in the formation of tryptamine [

5,

13].

The

TDC gene family in plants is relatively small; the first plant TDC-encoding gene was isolated from

Catharanthus roseus [

14]. The subsequent advancements in genome sequencing technology facilitated the identification of additional

TDC genes in various plants, including

Oryza sativa [

15],

Ophiorrhiza pumila [

16],

Citrus species [

17],

Aegilops variabilis [

18], and

Camptotheca acuminata [

19]. The regulatory functions of the proteins encoded by these genes have been gradually elucidated. However, the

Nicotiana tabacum and Arabidopsis genomes lack

TDC genes [

13]. Earlier research indicated that upregulated

TDC expression in plants leads to increases in tryptamine, serotonin, and melatonin levels [

20,

21,

22], whereas the downregulated expression of

TDC genes has the opposite effect [

15]. These results reflect the importance of TDC for the synthesis of melatonin in plants. A recent study showed that silencing

TDC expression in rice via RNA interference (RNAi) results in semi-dwarfism [

15]. In contrast, another study demonstrated that the overexpression of

TDC in rice leads to stunted growth and low fertility [

22]. Additionally,

TDC expression can enhance the ability of plants to tolerate drought and saline conditions [

7], suggestive of a key regulatory role influencing plant growth and stress responses. However, TDC functions have not been thoroughly characterized and additional research is required to clarify TDC regulatory effects and the underlying mechanisms.

Cucumber (

Cucumis sativus L.) is a vegetable crop that is cultivated worldwide, but it is susceptible to environmental stresses [

23]. Numerous studies have revealed the positive effects of exogenous melatonin on plant growth and stress tolerance, but there have been relatively few studies on the functions of endogenous melatonin. Therefore, the genes responsible for melatonin synthesis in different species should be identified and their regulatory functions will need to be determined. Although

TDC gene family members have been identified in some species, there is only limited available information regarding cucumber

TDC genes and their functions. Thus, in this study, we identified two

TDC genes in the cucumber genome. These genes were characterized on the basis of analyses of their promoter cis-elements, tissue-specific expression patterns, and responses to different stresses and plant hormones. To further verify the biological functions of

CsTDC genes, we conducted a subcellular localization analysis and transiently overexpressed the genes in tobacco to preliminarily explore their roles in plant responses to salt, drought, and low-temperature stresses. The study findings may form a theoretical foundation for future in-depth investigations on the potential functions of

CsTDC genes and the regulatory effects of endogenous melatonin.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Identification and analysis of TDC genes in cucumber

2.2. Analysis of cis-elements in the promoter regions

To investigate the cis-elements in the promoter regions of the two identified

TDC genes, we downloaded the genomic sequence 2 kb upstream of the initiation codon (ATG) of each gene from the cucumber genome database (Additional file 1). The putative cis-regulatory elements in the promoter sequences were analyzed using the PlantCARE database (

http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html) [

27].

2.3. Plant materials and treatments

Cucumber seedlings (Cucumis sativus L. cv. ‘Changchunmici’) were cultivated in a climate-controlled chamber (12-h light, 25 °C:12-h dark, 18 °C) at the College of Life Science, Gannan Normal University, Ganzhou, China. After an approximately 10-day cucumber fruit growth period, the following tissues were collected from each plant: basal old leaves (OL), upper young leaves (YL), middle mature leaves (ML), young stems (YS), roots (R), blooming female flower petals (FF), ovaries (O), blooming male flowers (MF), tendrils (T), fruits (F), and seeds (S). The collected samples were promptly frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C for the gene expression analysis.

For each stress and exogenous hormone treatment, 12 cucumber seedlings (half-expanded first true leaf) were transplanted to a plastic basin (33 cm × 25 cm × 11 cm) containing 5 L half-strength Hoagland nutrient solution [

23]. When the seedlings reached the two-leaf stage, the nutrient solution was supplemented with 100 mM NaCl, 10% PEG 6000, 50 mM NaHCO

3, 100 μmol ABA, 100 μmol JA, 100 μmol SA, 50 μmol 2,4-D, 50 μmol ETH, or 50 μmol GA. For the temperature treatments, the seedlings were transferred to a light incubator maintained at 40 °C (high-temperature stress) or 5 °C (low-temperature stress). The nutrient solution was refreshed every 2 days. Cucumber seedling roots and leaves were collected at 0, 0.5, 1, 3, 6, 12, and 24 h post-treatment. The collected samples were promptly frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C for the gene expression analysis.

2.4. RNA extraction and qRT-PCR analysis

Total RNA was extracted using the RNA prep pure Plant Kit (TANGEN). First-strand cDNA was synthesized following the instructions of the PrimeScript™ RT reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (Perfect Real Time) (TaKaRa). The qPCR amplification was performed using Hieff

® qPCR SYBR Green Master Mix (Yeasen) in a LightCycler

® 96 Instrument (Roche). Relative gene expression was calculated using the 2−

△△Ct method [

28]. The primers used for gene expression analysis can be found in Additional file 2.

2.5. Subcellular localization analysis

The CsTDC1 and CsTDC2 coding sequences (without the stop codon) were amplified by PCR and then inserted into the pCAMBIA2300-GFP vector (digested with XbaI and SmaⅠ) to generate the recombinant plasmids pCAMBIA2300-CsTDC1-GFP and pCAMBIA2300-CsTDC2-GFP (the primers are shown in Additional file 2). Next, Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101 cells were transformed with the recombinant plasmids or the empty pCAMBIA2300-GFP vector (negative control). The A. tumefaciens cells carrying pCAMBIA2300-GFP, pCAMBIA2300-CsTDC1/2-GFP, P19, or AtPIP2-mCherry (plasma membrane marker) were cultured with shaking until the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) reached 0.6–0.8. The cells were collected and resuspended in infiltration buffer (10 mM MES-KOH, pH 5.6, 10 mM MgCl2, and 100 μM acetosyringone) for an OD600 of 0.6. The cell solutions were then mixed in a 1:1:1 volume ratio (empty vector or recombinant plasmid: P19: AtPIP2-mCherry) and then injected into the lower epidermis of tobacco leaves. After 3 days, GFP fluorescence was observed using the SP8 MP confocal laser scanning microscope (Leica, Germany).

2.6. Transient overexpression of CsTDC genes in tobacco leaves

The CsTDC1 and CsTDC2 coding sequences were amplified by PCR and then inserted into the overexpression vector pCAMBIA 1305.4 to generate the recombinant plasmids pCAMBIA 1305.4-CsTDC1 and pCAMBIA 1305.4-CsTDC2 (the primers are shown in Additional file 2). Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101 cells were transformed with the recombinant plasmids or the empty pCAMBIA 1305.4 vector (negative control) and then cultured until the OD600 reached 0.6–0.8. The cells were collected, resuspended in infiltration buffer, and then mixed in a 1:1 volume ratio (empty vector or recombinant plasmid: P19) before being injected into 4-week-old tobacco leaves.

2.7. Determination of TDC activity and melatonin content

The injected tobacco leaf samples were collected after 2 and 4 days of transient expression of CsTDCs. The TDC activity was analyzed according to instructions of the Plant tryptophan decarboxylase (TDC) ELISA kit (LOT: 231103122O), which was purchased from Jiangsu Meimian industrial Co., Ltd (Jiangsu, China). The melatonin content was determined by Jiangsu Meimian industrial Co., Ltd using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC; LC-20AT, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan).

2.8. Transient overexpression of CsTDC genes and abiotic stress treatments

After the

CsTDC genes were transiently expressed in tobacco leaves for 2 days, the leaves were detached from the plants. The petioles were then immersed in 100 mL Erlenmeyer flasks filled with distilled water, 200 mM NaCl solution, or 0.5% PEG solution. The leaves were secured in place using a sponge. The treatments were conducted in a light incubator set at 23 °C with a 12-h light (70 µmol/m

2·s):12-h dark cycle and 65% relative humidity. For the low-temperature treatment, the leaves were placed in a light incubator set at 0 °C. The post-treatment fresh weight was compared with the initial fresh weight to calculate the leaf water loss rate. Negative values indicated the leaves absorbed water. The relative water content was measured as described by Hong et al. (2008) [

29]. The MDA content and electrolyte leakage rate were determined as described by Li et al. (2023) [

30].

2.9. Statistical analyses

Values presented are means ± standard deviation (SD) of three replicates. Significance analysis was conducted using Stst software by one-way ANOVA method and Duncan test.

4. Discussion

Melatonin, which is a novel plant growth regulator, plays a critical role in regulating various growth and developmental processes, while also enhancing plant stress tolerance, making it a promising candidate for future agricultural applications [

31]. However, in terms of their functions, endogenous melatonin has not been as thoroughly analyzed as exogenous melatonin. Therefore, the melatonin synthase-encoding genes in diverse species must be comprehensively identified and characterized regarding their regulatory effects. The biosynthesis of plant melatonin involves four main pathways; the initial reactions in all of these pathways involve tryptophan [

8,

9]. In most cases, tryptophan is decarboxylated by TDC to form tryptamine. Thus, TDC is considered to be the initial rate-limiting enzyme in the melatonin synthesis pathway. The final two rate-limiting steps in this pathway are mediated by SNAT, ASMT, and COMT. However, in plants, the

TDC gene family is smaller than the

ASMT [

32] and

COMT [

33] gene families. Most plants contain only one

TDC gene, but some plants, including

C. acuminata and

Capsicum annuum, have two

TDC genes, while others, such as

O. sativa and

Solanum lycopersicum L., have three

TDC genes [

34]. A previous study showed that

CsSNAT enhances salt tolerance and promotes growth in cucumber seedlings because it promotes melatonin synthesis [

35]. To the best of our knowledge, there are no reports regarding the cloning and characterization of the cucumber

TDC gene(s).

In this study, we identified two homologous

TDC genes (

CsTDC1 and

CsTDC2) in the cucumber genome (

Table 1). The subcellular localization results indicated that the CsTDC proteins are primarily located in the cytoplasm and plasma membrane (

Figure 4). Tissue-specific expression analyses revealed differences in the

CsTDC1 and

CsTDC2 expression levels among the 11 examined cucumber tissues (

Figure 1). The expression levels were highest in the seeds, followed by the roots and stems. The genes were expressed at relatively low levels in the leaves and reproductive organs. Hence, CsTDC1 and CsTDC2 may be important for regulating cucumber vegetative and reproductive growth processes, especially seed development and root growth. Earlier research confirmed that melatonin plays a vital role in strengthening plant stems [

36]. For example, melatonin treatments of peony leaves can significantly strengthen the pedicels. In accordance with this finding, silencing the peony melatonin synthesis-related gene

PlTDC results in a decrease in the endogenous melatonin content and weakens the pedicels. Furthermore, melatonin reportedly regulates the germination of Arabidopsis seeds by modulating the levels of endogenous hormones (e.g., ABA, GA, and IAA) [

37]. Additionally, exogenous melatonin promotes the germination of cucumber seeds and stimulates lateral root growth [

38]. Numerous studies have demonstrated that the application of exogenous melatonin increases the endogenous melatonin content, while the synthesis of endogenous melatonin is mediated by various enzymes, including TDC. Interestingly, the current study revealed

CsTDC1 and

CsTDC2 are highly expressed in the seeds, roots, and stems, suggestive of the importance of TDC for multiple melatonin-mediated processes (e.g., seed germination, lateral root growth, and strengthening of the stem). However, the associated regulatory mechanisms remain to be more thoroughly investigated.

Cis-elements are crucial for regulating gene expression. In this study, we identified four types of cis-elements (i.e., related to stress, hormone, and light responses as well as development) in the

CsTDC1 and

CsTDC2 promoters (

Table 2). Intriguingly, the number and diversity of the cis-elements were greater for the

CsTDC2 promoter than for the

CsTDC1 promoter. According to the qRT-PCR data,

CsTDC1 and

CsTDC2 expression levels increased substantially in response to various abiotic stresses (NaCl, NaHCO

3, PEG, cold, and heat) (

Figure 2) as well as exogenous hormones (ABA, SA, JA, ETH, 2,4-D, and GA) (

Figure 3). Notably, the JA treatment resulted in a 1,277-fold increase in the

CsTDC1 expression level in the roots. The ABA treatment also significantly increased the expression of

CsTDC1 and

CsTDC2 by 184-fold and 159-fold, respectively. These results suggest that

CsTDC1 and

CsTDC2 are responsive to abiotic stresses and exogenous hormones. The encoded proteins may have distinct but partially overlapping regulatory effects on cucumber stress tolerance as well as the perception and transduction of hormone signals, particularly JA and ABA signals.

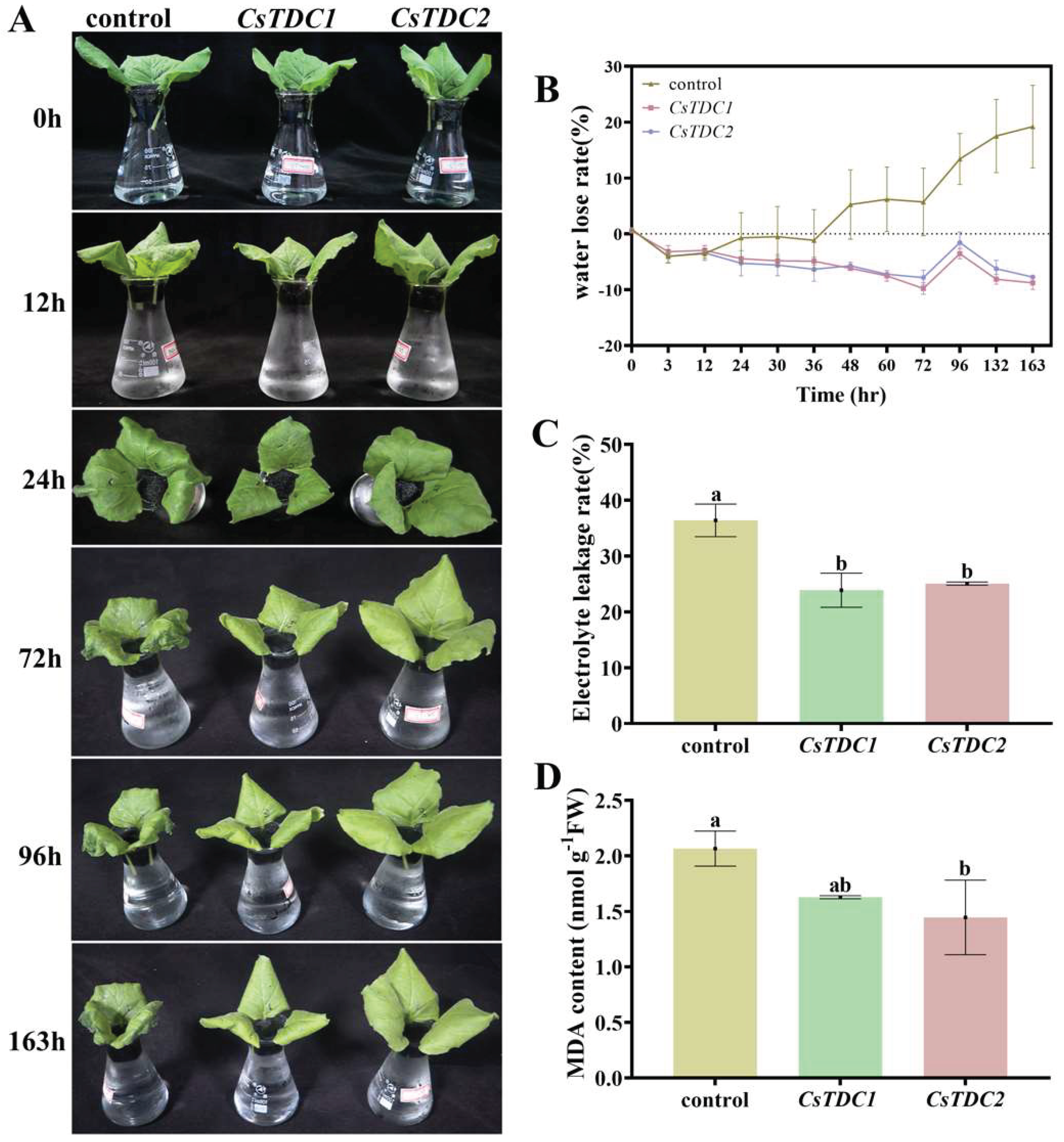

To further explore how CsTDC1 and CsTDC2 contribute to cucumber stress responses, we transiently overexpressed

CsTDC1 and

CsTDC2 in tobacco leaves, which underwent various abiotic stress treatments. On the basis of the results, the overexpression of

CsTDC1 and

CsTDC2 apparently leads to increases in the TDC activity and melatonin content in tobacco leaves (

Figure 5). Moreover, it can enhance the tolerance of tobacco leaves to salt (

Figure 7), drought (

Figure 8), and low-temperature stresses (

Figure 9). The overexpression of

CsTDC2 appears to have a more pronounced effect than the overexpression of

CsTDC1. In addition, in the absence of stress, the detached leaves overexpressing

CsTDC1 and

CsTDC2 had a significantly lower water loss rate and were less wilted than the control leaves, implying CsTDC1 and CsTDC2 can enhance the absorption and retention of water by tobacco leaves (

Figure 6). A previous study demonstrated that ABA induces stomatal closure, thereby limiting transpiration [

39]. In the current study,

CsTDC1 and

CsTDC2 were highly expressed in response to ABA, suggestive of a regulatory role in ABA-mediated stomatal closure. Earlier research indicated that low temperatures induce

TDC gene expression in cucumber plants [

40,

41]. Moreover, the addition of exogenous melatonin promotes melatonin production in cucumber and enhances seedling cold tolerance [

40,

41]. Similarly, the application of exogenous melatonin also increases melatonin production in loquat leaves and improves the ability of loquat seedlings to withstand drought conditions [

42]. Furthermore, exogenous melatonin helps regulate the salinity–alkalinity tolerance of certain horticultural crops (e.g., grapes and tomatoes) [

43,

44]. Its antioxidant and free radical scavenging properties may be the primary reasons for the positive effects of melatonin on plant stress tolerance [

45]. Plant growth, development, and stress tolerance are controlled by a complex process involving numerous genes, proteins, and regulatory mechanisms. Therefore, to further functionally characterize melatonin and clarify the associated gene regulatory network, additional research on endogenous melatonin is required. The present study provides preliminary evidence that

CsTDC1 and

CsTDC2 encode positive regulators of cucumber stress tolerance and establishes a theoretical foundation for future research on the roles of TDC and endogenous melatonin in cucumber and related crops.

Figure 1.

CsTDC expression levels in different tissues. A qRT-PCR analysis was performed to analyze CsTDC expression levels in the basal old leaves (OL), upper young leaves (YL), middle mature leaves (ML), roots (R), isolated seeds (S), young stems (YS), blooming female flower petals (FF), ovaries (O), blooming male flowers (MF), tendrils (T), and fruits (F). The expression levels in OL were set as 1. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 3). Different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

Figure 1.

CsTDC expression levels in different tissues. A qRT-PCR analysis was performed to analyze CsTDC expression levels in the basal old leaves (OL), upper young leaves (YL), middle mature leaves (ML), roots (R), isolated seeds (S), young stems (YS), blooming female flower petals (FF), ovaries (O), blooming male flowers (MF), tendrils (T), and fruits (F). The expression levels in OL were set as 1. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 3). Different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

Figure 2.

Analysis of CsTDC expression following abiotic stress treatments. The gene expression levels under non-stressed conditions were set as 1. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 3). Different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

Figure 2.

Analysis of CsTDC expression following abiotic stress treatments. The gene expression levels under non-stressed conditions were set as 1. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 3). Different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

Figure 3.

Analysis of CsTDC expression following exogenous phytohormone treatments. The gene expression levels before the treatments (0 h) were set as 1. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 3). Different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

Figure 3.

Analysis of CsTDC expression following exogenous phytohormone treatments. The gene expression levels before the treatments (0 h) were set as 1. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 3). Different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

Figure 4.

Subcellular localization of CsTDC1 and CsTDC2. A. Plasmid used for the subcellular localization assay. B. Subcellular localization of CsTDC1 and CsTDC2 in tobacco leaf epidermal cells. Bars = 20 μm.

Figure 4.

Subcellular localization of CsTDC1 and CsTDC2. A. Plasmid used for the subcellular localization assay. B. Subcellular localization of CsTDC1 and CsTDC2 in tobacco leaf epidermal cells. Bars = 20 μm.

Figure 5.

Effects of the transient overexpression of CsTDC genes in tobacco leaves on the TDC activity and melatonin content. A. Plasmid used for the transient overexpression assay. The empty pCAMBIA 1305.4 vector (control) and the recombinant plasmids carrying CsTDC1 and CsTDC2 were used for the transient expression analysis involving tobacco leaves. The injected leaf tissues were collected after 2 and 4 days to determine the TDC activity (B) and melatonin content (C). Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 3). Different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

Figure 5.

Effects of the transient overexpression of CsTDC genes in tobacco leaves on the TDC activity and melatonin content. A. Plasmid used for the transient overexpression assay. The empty pCAMBIA 1305.4 vector (control) and the recombinant plasmids carrying CsTDC1 and CsTDC2 were used for the transient expression analysis involving tobacco leaves. The injected leaf tissues were collected after 2 and 4 days to determine the TDC activity (B) and melatonin content (C). Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 3). Different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

Figure 6.

Physiological analysis of transgenic plants transiently overexpressing CsTDC1 or CsTDC2 and negative control (pCAMBIA 1305.4) plants under normal conditions. A. Phenotype of detached leaves placed in a 100 mL Erlenmeyer flask containing distilled water. B. Water loss rate of detached leaves. The electrolyte leakage rate (C) and MDA content (D) were measured when the detached leaves were maintained in distilled water for 36 h. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 3). Different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

Figure 6.

Physiological analysis of transgenic plants transiently overexpressing CsTDC1 or CsTDC2 and negative control (pCAMBIA 1305.4) plants under normal conditions. A. Phenotype of detached leaves placed in a 100 mL Erlenmeyer flask containing distilled water. B. Water loss rate of detached leaves. The electrolyte leakage rate (C) and MDA content (D) were measured when the detached leaves were maintained in distilled water for 36 h. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 3). Different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

Figure 7.

Transient overexpression of CsTDC1 and CsTDC2 increased the tolerance of tobacco to salt stress. A. Phenotype of detached leaves after the NaCl treatment. B. Water loss rate of detached leaves. The electrolyte leakage rate (C) and MDA content (D) were measured when the detached leaves were maintained in the NaCl solution for 36 h. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 3). Different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

Figure 7.

Transient overexpression of CsTDC1 and CsTDC2 increased the tolerance of tobacco to salt stress. A. Phenotype of detached leaves after the NaCl treatment. B. Water loss rate of detached leaves. The electrolyte leakage rate (C) and MDA content (D) were measured when the detached leaves were maintained in the NaCl solution for 36 h. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 3). Different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

Figure 8.

Transient overexpression of CsTDC1 and CsTDC2 increased the tolerance of tobacco to drought stress. A. Phenotype of detached leaves after the PEG treatment. B. Water loss rate of detached leaves. The electrolyte leakage rate (C), MDA content (D), and relative water content (E) were measured when the detached leaves were maintained in the PEG solution for 24 h. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 3). Different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

Figure 8.

Transient overexpression of CsTDC1 and CsTDC2 increased the tolerance of tobacco to drought stress. A. Phenotype of detached leaves after the PEG treatment. B. Water loss rate of detached leaves. The electrolyte leakage rate (C), MDA content (D), and relative water content (E) were measured when the detached leaves were maintained in the PEG solution for 24 h. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 3). Different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

Figure 9.

Transient overexpression of CsTDC1 and CsTDC2 increased the tolerance of tobacco to cold stress. A. Phenotype of detached leaves after the cold treatment. B. Water loss rate of detached leaves. The electrolyte leakage rate (C) and MDA content (D) were measured when the detached leaves were maintained at 0 °C for 163 h. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 3). Different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

Figure 9.

Transient overexpression of CsTDC1 and CsTDC2 increased the tolerance of tobacco to cold stress. A. Phenotype of detached leaves after the cold treatment. B. Water loss rate of detached leaves. The electrolyte leakage rate (C) and MDA content (D) were measured when the detached leaves were maintained at 0 °C for 163 h. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 3). Different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the tryptophan decarboxylases in cucumber.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the tryptophan decarboxylases in cucumber.

| Gene ID |

Length (aa) |

Molecular Weight (KD) |

Chromosome |

Location |

pI |

Strand Direction |

Subcellular Location |

| CsaV3_1G036910 |

499 |

55.7 |

1 |

22824145-22827250 |

6.34 |

– |

cytoplasm, plasmamembrane |

| CsaV3_3G028450 |

486 |

54.6 |

3 |

24862649-24886753 |

5.79 |

– |

cytoplasm, plasmamembrane |

Table 2.

Analysis of cis-elements in CsTDC promoters. The numbers represent the number of repeats of each cis-element.

Table 2.

Analysis of cis-elements in CsTDC promoters. The numbers represent the number of repeats of each cis-element.

| Cis-element |

Function |

CsTDC1 CsTDC2 |

| Stress-related |

|

|

| ARE |

cis-element essential for the anaerobic induction |

2 5 |

| WRE3 |

wound response elements |

1 1 |

| LTR |

cis-element involved in low-temperature responsiveness |

0 1 |

| STRE |

stress response elements |

4 2 |

| MYB |

stress response elements |

1 3 |

| MYC |

drought and cold responsive elements |

1 3 |

| Hormone-related |

|

|

| ERE |

ethylene-responsive element |

1 5 |

| ABRE |

cis-element involved in the abscisic acid responsiveness |

1 1 |

| CGTCA-motif |

cis-element involved in the MeJA-responsiveness |

0 2 |

| TCA-element |

cis-element involved in salicylic acid responsiveness |

1 0 |

| TGA-element |

auxin-responsive element |

0 1 |

| TGACG-motif |

cis-element involved in the MeJA-responsiveness |

0 2 |

| Development-related |

|

|

| AACA_motif |

involved in endosperm-specific negative expression |

1 0 |

| circadian |

cis-acting regulatory element involved in circadian control |

1 0 |

| as-1 |

cis-element involved in the root-specific expression |

0 2 |

| CAT-box |

cis-acting regulatory element related to meristem expression |

0 2 |

| Light-related |

|

|

| AE-box |

part of a module for light response |

0 1 |

| Box 4

|

a conserved DNA module involved in light responsiveness |

4 7 |

| GATA-motif |

part of a light responsive element |

1 0 |

| GT1-motif |

light responsive element |

0 3 |

| TCCC-motif |

part of a light responsive element |

1 0 |

| TCT-motif |

part of a light responsive element |

1 0 |

| G-Box |

cis-element involved in light responsiveness |

1 2 |

| G-box |

cis-element involved in light responsiveness |

0 1 |

| GA-motif |

part of a light responsive element |

0 1 |

| MRE |

MYB binding site involved in light responsiveness |

4 1 |

| AAAC-motif |

light responsive element |

1 0 |