1. Introduction

In tissue engineering, living cells combined with bioactive materials aim to create biohybrid constructs that can replace or regenerate damaged tissues when implanted. Recent methods focus on using patient-derived cells. The process involves isolating autologous cells, often stem cells, expanding them in culture, and seeding them onto scaffolds (

Figure 1) [

1]. These cells adapt to the new material, which can be influenced through growth factors or mechanical stimulation to encourage desired cell types [

2,

3].

However, tissue engineering's clinical applications remain mostly limited to thin or avascular tissues, like cartilage [

4]. One main challenge is the oxygen supply to cells within engineered constructs. Oxygen and nutrients rely on diffusion, meaning cells must be close to capillaries [

5]. Promoting vascularization is crucial to ensure oxygen and nutrient delivery to cells within larger implants [

4,

6].

While spontaneous blood vessel growth from the host occurs after implantation, it's slow and can lead to insufficient oxygen supply [

4], which might result in cell death or inconsistent responses. To overcome this, in vitro pre-vascularization is proposed. This involves creating capillary-like networks using endothelial cells on a fibroblast or mesenchymal stem cell feeder-layer within a fibrin gel matrix [

5,

7].

Fibrin gel's unique properties make it an excellent matrix for promoting angiogenesis (blood vessel formation) [

8,

9]. In both two-dimensional and three-dimensional settings, fibrin gel offers stability, porosity, and the possibility to incorporate growth factors [

10]. In a three-dimensional environment, fibrin gel mimics the natural extracellular matrix, making it ideal for regenerative medicine [

11,

12].

Fibrin's biodegradability allows gradual replacement of the scaffold with new tissue over time. However, its rapid degradation might limit long-term use. Polymer fibers can reinforce the scaffold, controlling its degradation profile for tissue regeneration [

13]. Combining a fibrin-based hydrogel with 3D-printed polymer fibers offers a biocompatible, viscoelastic environment that promotes cellular attachment and mimics the natural extracellular matrix [

10,

14]. This approach accommodates cellular needs post-implantation.

This technique employs autologous sources for cells, fibrinogen, and thrombin, making it promising for generating fully autologous implants. This minimizes rejection and foreign body responses, potentially leading to clinical applications.

In summary, tissue engineering merges living cells with bioactive materials to create biohybrid constructs for tissue replacement. Patient-derived cells, especially stem cells, are used with scaffolds and growth factors to encourage desired cell types [

15]. Vascularization is a challenge for larger constructs due to oxygen diffusion limitations. In vitro pre-vascularization using endothelial cells in a fibrin gel matrix addresses this issue. Fibrin's properties promote angiogenesis and gradual scaffold replacement, although its rapid degradation is a concern. Polymer fibers reinforce the scaffold's degradation profile and provide a biocompatible environment, with autologous sources making it a promising approach for clinical applications.

For that we used new adjustable fibrin-based hydrogels to which we linked the

N-vinylpyrrolidone-based copolymer PVP

12400-co-GMA

10mol%, which was synthesized by RAFT polymerization [

15,

16]. The functional copolymer contains 10 mol% of glycidyl methacrylate (GMA) to enable covalent bond formation towards the amine- and thiol-groups of the fibrin (

Figure 2).

Impact Statement

The experiments presented here provide conclusive results regarding the influence of the mechanical controllability of fibrin hydrogels on capillarization. By using copolymers, we succeed in obtaining a positive effect on capillary growth on and within hydrogels. This is an important starting point, for example, in the field of wound healing, as even larger poorly healing wounds can heal as quickly as possible, and the tissues can be supplied with blood again. At the same time, this tissue engineering approach offers far-reaching possibilities about the growth of artificial organoids and organs to achieve a nutrient supply beyond the diffusion limit.

2. Results

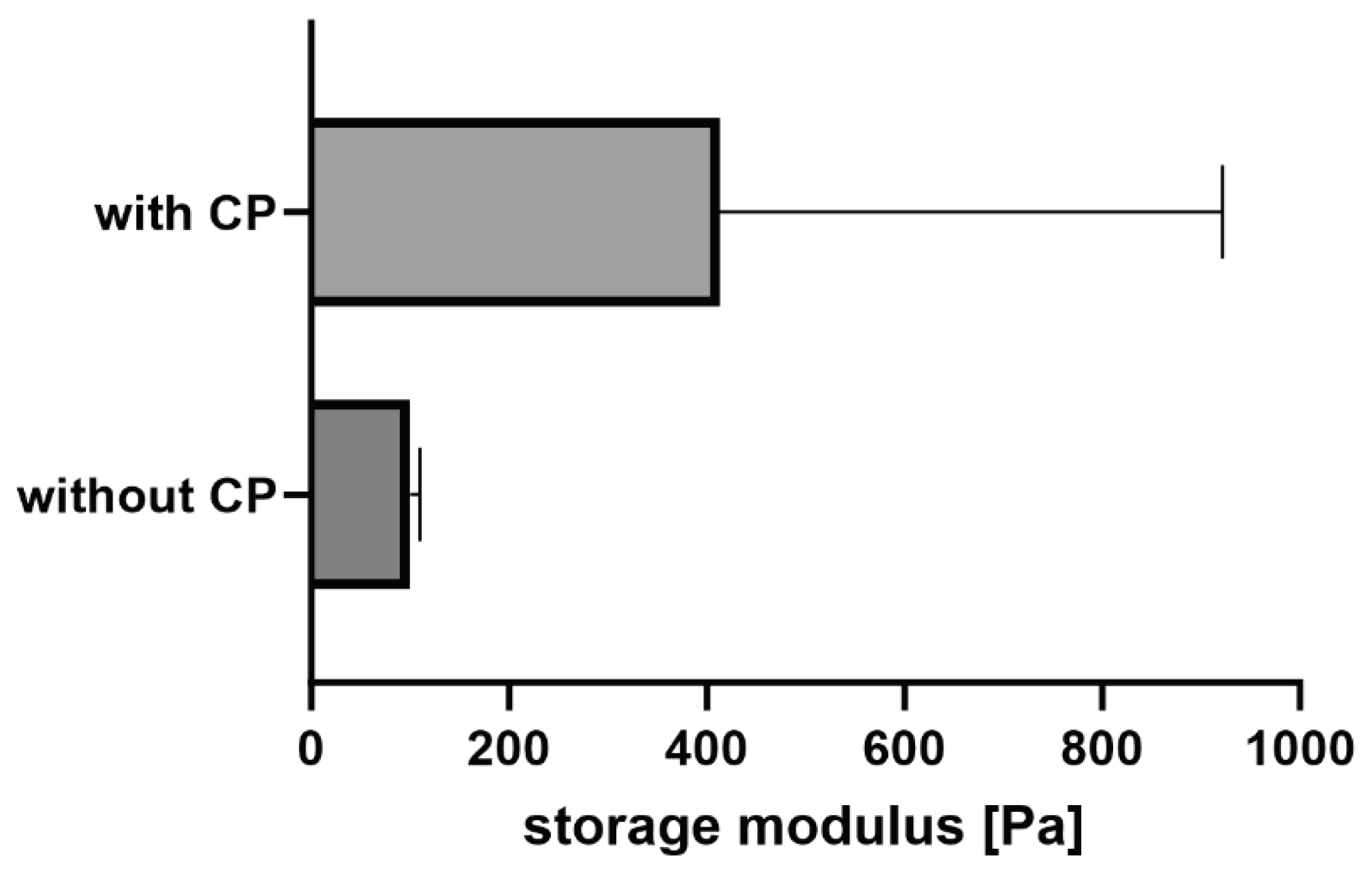

2.1. Rheology

Both hydrogel types, with and without the fibrin fiber copolymer, exhibit typical viscoelastic behavior akin to fibrin-based hydrogels, though with differing strengths. Results are shown in

Figure 3, with gelation taking 45 minutes. Linear viscoelasticity ends around a critical strain of 10% for both samples. The functional copolymer enhances the storage modulus of fibrin-based hydrogels due to covalent crosslinks between the copolymer's epoxy groups and fibrin's thiols or amines [

15]. Frequency-dependent measurements confirm the hydrogel nature of the enhanced system; storage and loss moduli remain independent of frequency until a critical value.

Both samples show slight strain-stiffening, though it's weaker in the copolymer-containing sample compared to pure fibrin. This is attributed to additional covalent bonds between the copolymer and fibrin, leading to a denser, less flexible network. While previous studies with lower copolymer concentrations showed enhanced strain-stiffening, higher copolymer concentration here leads to denser networks and increased storage modulus, yet limits fiber movement dynamics, resulting in weaker strain-stiffening behavior.

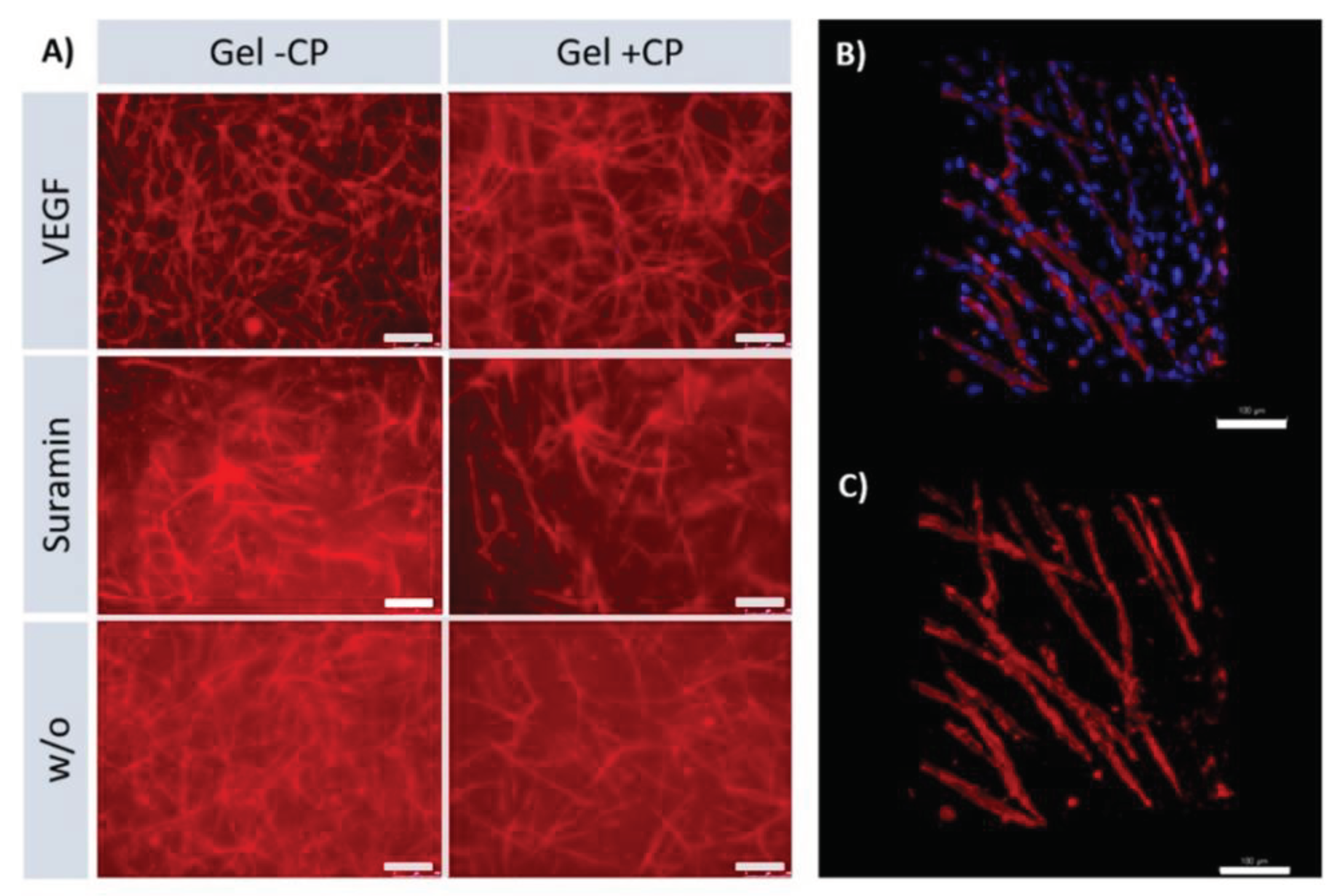

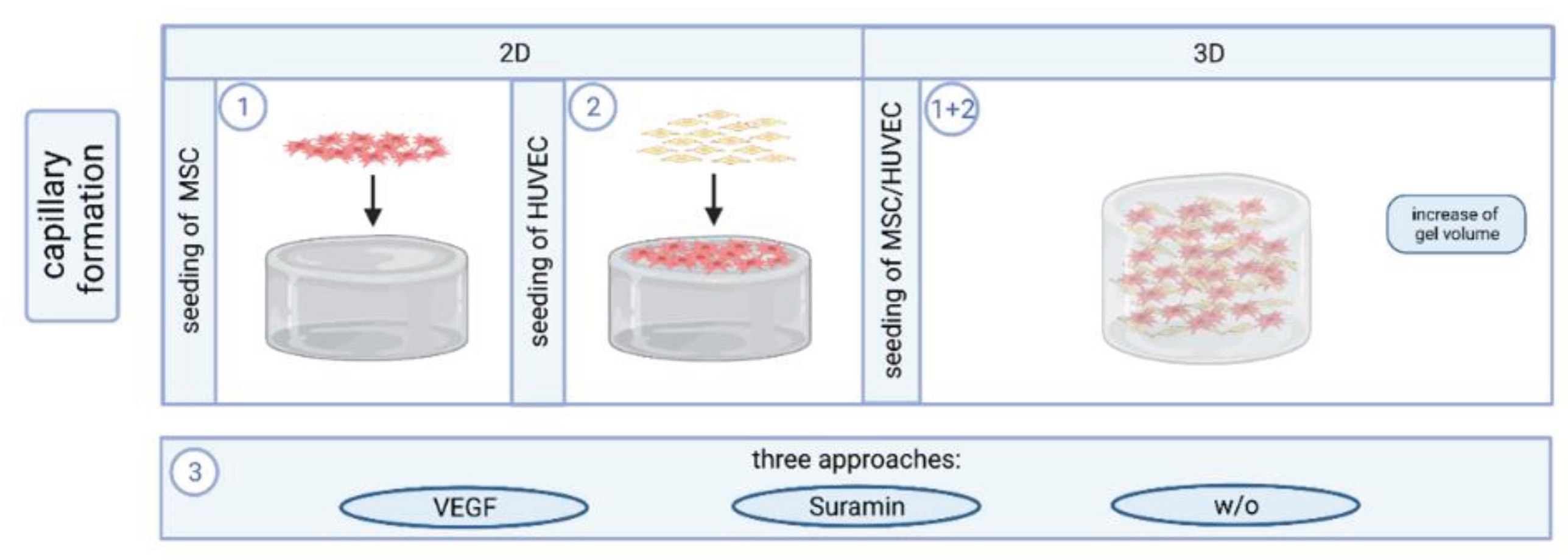

2.2. Capillary-Like Structures on Hydrogels with and without Copolymer

The addition of the copolymer PVP

12400-co-GMA

10mol%, to the fibrinogen solution allows for the modulation of the gel’s mechanical properties, such as increased storage modulus, as well as its degradation rate as described before by Al Enezy-Ulbrich et.al. [

15]. To investigate the behavior of HUVEC on these copolymer-modified fibrin gels, HUVEC were seeded on a layer of MSC on the hydrogel surface and formation of capillary-like structures was observed.

The effect of different approaches was analyzed by comparing samples cultured on the same material and receiving different supplements. As expected, significant differences in the length and number of junctions were found between VEGF and suramin supplementation on all three materials (

Figure 4 B, C). On TCPS and gel with copolymer, length and number of branches were significantly higher in the VEGF approach than without supplements. Quantification showed that within each approach, the mean length of structures formed, and the mean number of branches were higher on gels than on TCPS. The results show that the copolymer-modified fibrin hydrogel has a positive effect on angiogenesis. Comparing the TCPS against the fibrin hydrogel condition, the fibrin hydrogel triggers angiogenesis in every case. On fibrin hydrogels, a clearly strengthened network can be seen with and without the use of copolymer. With the use of copolymer modified fibrin hydrogel longer branches and higher interconnectivity are achieved. It is noteworthy that the addition of the inhibitor suramin on TCPS completely prevents angiogenesis, resulting in the typical islet formation (

Figure 4 A). On the copolymer modified fibrin hydrogel, capillaries are formed even in this condition to a higher degree. This shows the positive influence of the new copolymer; if this is added to the gel, the branch length and the number of junctions is increased significantly (

Figure 4 B, C). In the VEGF approach, the results are similar both with copolymer and without, as the fibrin gel as a material in combination with the growth factor generally stimulates and supports angiogenesis. Remarkably when suramin is added to the sample as an inhibitor, the use of the copolymer in the gel continues to have a significantly positive effect on angiogenesis. Despite the inhibitor, we were able to achieve an increased number of junctions and prolonged branch length with our newly modified gel. The reason for this could be that the use of the copolymer, which is associated with mechanical controllability which increases the stiffness of the gel, so that there is a positive influence on angiogenesis. This effect continues over the inhibition by suramin.

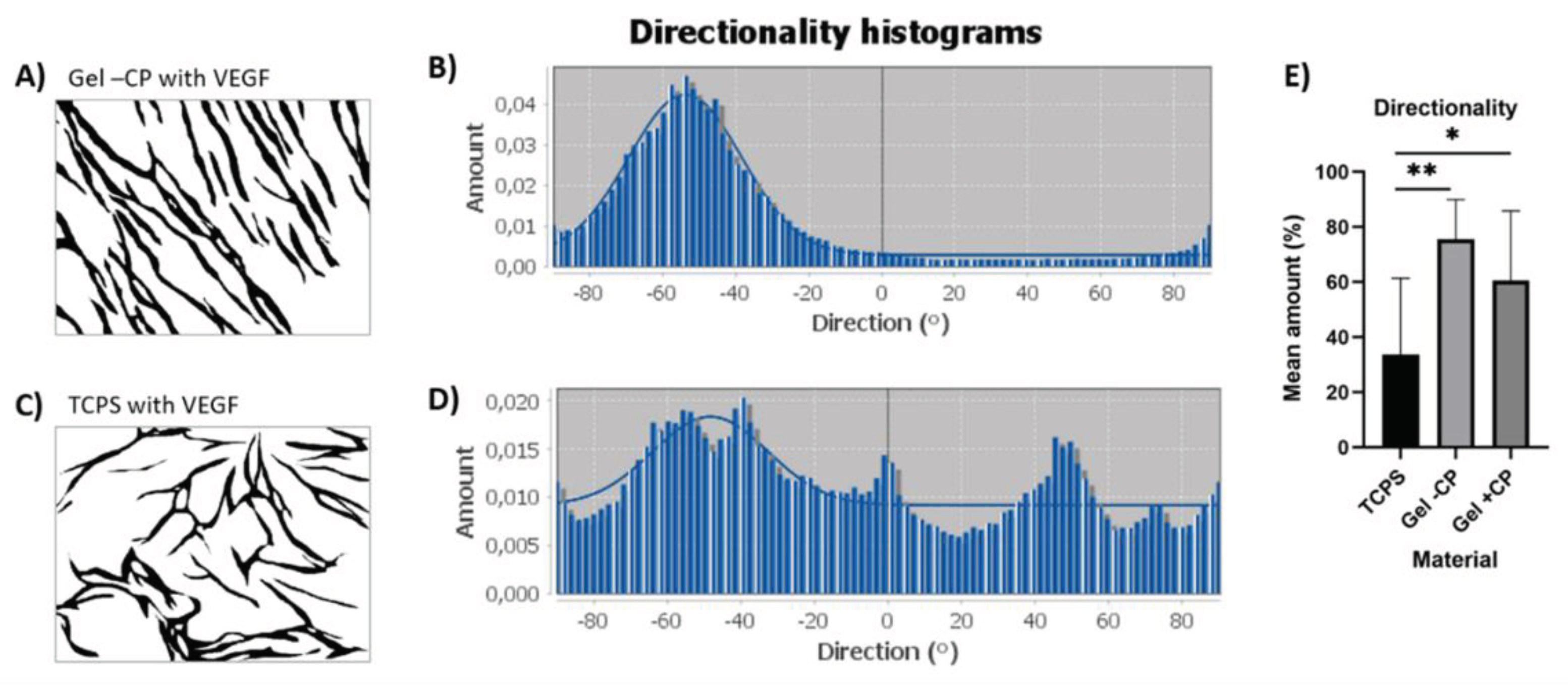

2.3. Parallel Alignment of Capillary-Like Structures on Hydrogel Surfaces

The parallel alignment of the capillaries on the fibrin hydrogels was remarkable. Known from the state of art, patterning and alignment of endothelial cells on hydrogels have been reported in cases in which this behavior was actively initiated. Strategies to induce such an alignment include exposure to cyclic mechanical strain, exposure to flow or specific scaffold design features, including endothelial cell pre-seeding on tubular structures and parallel arrangement of microfibers [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. Possible reasons for the spontaneous alignment here could be an alignment of HUVEC along the fibrin fibers present in the gel, likely mediated by integrin-based adhesion or an alignment caused by the surface curvature of the gels. To analyze whether the alignment is a result of flexing or traction of the gel during polymerization phase, an experiment was carried out in which the gels were removed from the well plate after casting, rotated by 180 degrees and only then populated. By inverting the gels tension is removed. Nevertheless, the capillaries that formed on the surface of flipped gels, presented the parallel orientation that has been observed before (

Figure 5 A). SEM images showed the surface of the gel as well as areas in which the gel was pulled open to reveal the arrangement of fibers. Despite amorphous surfaces, the targeted alignment of the capillaries is evident.

2.4. Formation of Capillary-Like Structures in a 3D Environment

In the tissue engineering field, the transfer to three-dimensional domains is of great importance. In the two-dimensional field, we could show that we achieved significantly longer branches and more junctions by using fibrin hydrogel in combination with our new copolymer. This observation should also be verified in the 3D domain. Based on the work of Kniebs

et al., the number of cells used for resuspension in the fibrinogen solution was increased for 3D approaches to 5.25*10 [

5] cells per cell type per well [

25]. With a complete translation to a 3D coculture-system both MSC and HUVEC were suspended in the fibrinogen solution before polymerization. Successful capillary network formation was observed in all approaches (

Figure 6). We were able to show that even in the multidimensional range our fibrin hydrogel supports angiogenesis well and delivers stable results. Capillaries were formed to a lesser extent with the addition of Suramin but were also present in this approach despite inhibitor.

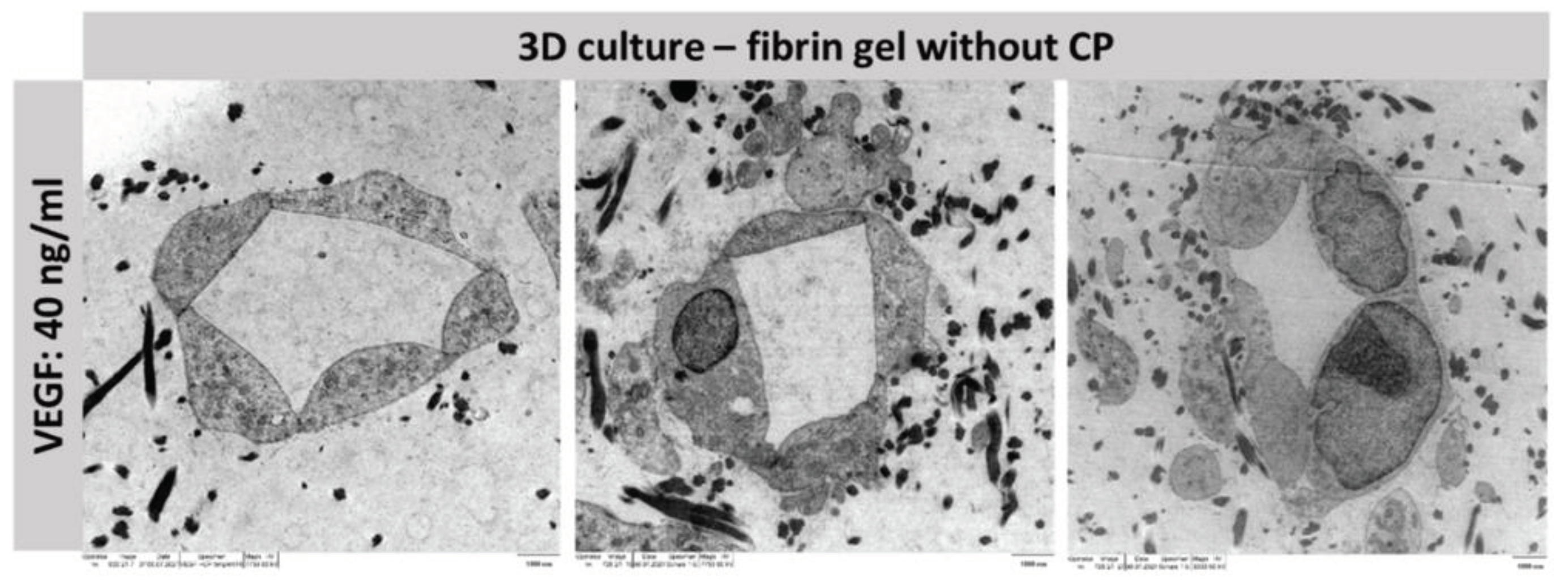

2.5. Lumen Detection

To prove that the tubes formed functional capillaries, it is essential to analyze the lumen of the structure. For this purpose, a three-dimensional co-culture of MSC and HUVEC was established in fibrin-based hydrogels without copolymer in a preliminary experiment. By adding VEGF at a concentration of 40 ng/ml, stable capillary formation was achieved, which was then subsequently analyzed using TEM (

Figure 7).

3. Discussion

3.1. Mechanical Adjustability of Fibrin Gels

The addition of a functional copolymer does not influence the gelation properties as shown in

Figure 3 A. Already at the start of the time-dependent measurement, the storage modulus is above the loss modulus, indicating that the gelation is fast and takes place before the instrument starts recording the data. The storage and the loss modulus are parallel to the x-axis with increasing frequency in the frequency-dependent measurements (

Figure 3 B). This means that both gels have viscoelastic properties. The addition of the copolymer does not influence the frequency dependent behavior but at a higher modulus value. Both hydrogels also show a slight strain-stiffening behavior with increasing strain (

Figure 3 C). This behavior is typical for biological tissues like fibrin to withstand forces like the blood flow. That the reinforcement of the fibrin-based hydrogels with the functional copolymer can even enhance the strain-stiffening has already been shown in our previous work [

15]. The copolymer also increases the storage modulus of the material and therefore its stiffness but at a concentration of approximately 11 w% the increase of the averaged storage modulus is not significant (

Figure 8).

In our previous work we have demonstrated that the highest storage modulus was achieved at a copolymer concentration of approximately 2 w% [

15]. A further increase of the concentration was not beneficial for the storage modulus. The reason for this is that the copolymer can already react with the thiols and amines of the fibrinogen in the solution before the gelation starts. With an increasing copolymer concentration, the probability also increases that covalent bonds from the functional copolymer towards the thrombin binding site increases. In this case the fiber formation would be disturbed resulting in a lower storage modulus compared to these achieved at lower copolymer concentrations.

3.2. Capillary-Like Structures on Hydrogels with and without Copolymer

Remarkably, the capillary-like structures formed on the gels showed a parallel orientation, independent of donor, age, or supply of additional factors. To further characterize the alignment of capillary-like structures that was observed on both gels but not on TCPS, pre-processed pictures of the VEGF approach were used for directionality analysis with ImageJ. In short, the analysis of an image results in a histogram reflecting the number of structures in the image that are subjected to a certain angular direction. For the highest peak of the histogram, the program fits a gaussian curve and displays an “amount”-value, which indicates the percentage of the present structures that align in the specific direction of the highest peak and fit under its respective curve. Two exemplary images and histograms are given in

Figure 9 A-D. Capillary-like structures on TCPS, gels with and without copolymers show means of 33.7%, 60.6% and 75.5%, respectively. Structures on both gels show a significantly higher mean, thus a significantly clearer directionality, when compared to TCPS (

Figure 9E). Consequently, the parallel alignment on the fibrin gels with and without copolymer is remarkably enhanced in comparison to TCPS, confirming the impression of parallel structure orientation that occurs predominantly on gel surfaces.

Comparing the formation of capillary-like structures on gels and TCPS, it was observed that the gels induced an alignment of the resulting capillaries on gels and that the gels triggered the formation of capillary-like structures to some extent even in the Suramin and w/o approaches.

The reason that capillaries arrange themselves in parallel when growing on fibrin hydrogels is likely due to the mechanical and biological properties of the hydrogel. Fibrin hydrogels have a 3D network structure that can influence the orientation and alignment of the growing capillaries. The biochemical signals in the hydrogel can direct the migration and alignment of capillary cells, leading to the formation of parallel structures. [

26,

27] Furthermore, factors such as oxygen gradients and nutrient availability also play a role in shaping the organization of capillaries on fibrin hydrogels.

3.3. Formation of Capillary-Like Structures in a 3D Environment

The fact that the capillary networks formed in the hydrogels with copolymer appear less dense is because additional crosslinks provided by the copolymer improve the mechanical properties of the material and simultaneously create an ultrastructure with thicker fibrin strands that are tightly linked together, resulting in an altered porosity. A homogeneous, structured angiogenesis in a three-dimensional context is present here. In contrast to the 2D endothelial networks, images of the 3D structures could not be quantified with the previously applied method due to their multi-layered nature. Images taken with the fluorescence microscope only present a fraction of the gel’s depth and therefore only a fraction of the formed network. With 2 photon microscopy, it is feasible to make a more detailed statement.

3.4. Lumen Detection

The TEM views demonstrate that the resulting structures are real capillaries with closed lumen. The individual cells arrange themselves around a lumen located in the center. However, this is of course only an exemplary location of the entire capillary; further experiments must be conducted to analyze whether the capillary has a lumen throughout and could guarantee a blood flow. Staining with Texas-red labelled dextran can be applied to allow for conclusions about the maturity of the capillaries and can reveal potential leakage [

28,

29].

4. Conclusions

In the present project, in vitro angiogenesis was successfully performed reproducibly on the surface and within a 3D environment of fibrin-based hydrogels. A capillary-like network with a remarkable parallel arrangement was formed. A comparison of network formation on three materials was performed: TCPS and gels with and without copolymer. HUVEC co-cultured with MSC on gels formed dense networks with a clear orientation of capillary-like structures. In addition to the formation of endothelial cell networks on gel surfaces, the in vitro angiogenesis protocol was successfully transferred to a 3D context.

The experiments compared the influence of pure fibrin hydrogel on angiogenesis and, in contrast, the use of a mechanically controllable fibrin hydrogel by incorporating the copolymer PVP12400-co-GMA10mol%.

The formation of three-dimensional capillary-like networks in fibrin-based hydrogels with the copolymer was successfully demonstrated in the experiments presented.

In future the fabrication of more complex scaffolds using 3D printing could be considered so that different functional layers can be generated. The embedding of specific growth factors in functionalized hydrogels also offers a further advantage here, so that the corresponding constructs can be adapted to the respective application.

Our experiments have shown that the formation of capillaries can be successfully induced on and in fibrin hydrogels and that they provide an optimal scaffold. Our new approach of using the copolymer in combination with the fibrin hydrogel additionally offers the possibility to optimize the mechanical properties of the gel and to adapt it to the respective application. A significant improvement of angiogenesis can be achieved regarding the number of junctions and the length of the branches. Basically, it can be said that the properties of the fibrin hydrogel are proangiogenic and by using our new innovative copolymer a further improvement of the environmental conditions can be achieved. Noteworthy here is the fact that the use of our copolymer supports capillary formation under the molecular inhibitor suramin to a special degree; this offers a starting point for further medical research, as this finding is an important factor in the field of poorly healing wounds. [

30,

31] The use of fibrin hydrogel in combination with copolymer can help these wound areas to heal faster and to be supplied with blood again quickly.

We have demonstrated a biohybrid system which can be used as a base tissue engineering implant with adjustable mechanical properties, and which has great potential to alleviate the problem of organ donor shortage and outperform conventional implant types in terms of functionality, biocompatibility, and longevity. The vascularization of these biohybrid implants is critical for maintaining cell viability during the in vitro maturation phase and for supplying oxygen and nutrients required for the growth, remodeling, and repair processes occurring in vivo [

32].

Once the interactions at the cell-biomaterial interface are thoroughly characterized, the present strategy for vascularizing constructs via fibrin-based hydrogels in combination with specific copolymers may be more broadly applicable. Especially for further approaches the use of different copolymers, the interaction with fibrin hydrogels and their crosslinking will open a new field of biohybrid tissues.

5. Materials and Methods

Preparation of Fibrin-Based Hydrogels

Fibrinogen powder (100 mg) from human plasma (62% protein, Sigma Aldrich/Merck) was diluted in 5 ml aqua ad iniectabilia and 5 ml incomplete GBSH5 buffer (without D-Glucose, containing 0.37 g L−1 KCl, 0.2 g L−1 MgCl2 in 6H2O, 0.15 g L−1 MgSO4 in 7H2O, 7.00 g L−1 NaCl, 0.12 g L−1 Na2HPO4, 1.19 g L−1 HEPES). Dialysis tubing was prepared by heating tubes of approximately 30 cm length in 1 mM EDTA, placed in a boiling water bath for 10 minutes. Tubes were rinsed with aqua ad and knotted at one end. When completely dissolved, the fibrinogen suspension was transferred to the prepared dialysis tubes; tubes were knotted at the other end, covered in incomplete GBSH5, and stored at 4°C overnight. Dialysis tubes were emptied into falcon tubes and centrifuged at 5000 g for 30 minutes. The supernatant containing the fibrinogen was collected, sterile filtered, and stored in aliquots of 1 ml (6.2 mg fibrinogen/ml) at -80°C until usage.

A fibrinogen-buffer suspension was prepared according to

Table 1. For experiments with gels of both fibrin and the copolymer PVP

12400-co-GMA

10mol%, the copolymer was dissolved in 4.6 ml incomplete GBSH

5 (30 mg/ml) to maintain the same overall volume of gels with and without copolymer. To prepare the gels in 24-well plates, thrombin was transferred to the bottom of the well, fibrinogen-buffer suspension was added and mixed quickly. Gels were incubated at 37 °C for 15 minutes before cell seeding (

Figure 10).

5.1. Rheology

Rheological measurements were conducted to analyze the mechanical properties of the hydrogels. A TA Instrument Discovery HR-3 hybrid rheometer, which was equipped with a 20 mm cone plate geometry (2° cone) with a solvent trap, was used. The solutions for the hydrogel synthesis were prepared as stated above. After the addition of the thrombin solution to the mixture and a fast shaking of the vial, 74 µL of the liquid were pipetted on the Peltier plate of the rheometer, which was heated to 37 °C. The gap was adjusted to 51 µm. To avoid evaporation and drying of the hydrogel, the solvent trap was filled with some water and the setup was closed with a lid. A time-dependent measurement at a fixed frequency of 1 Hz and a fixed strain of 0.1 % was performed to ensure a complete gelation of the sample. Then, at a fixed strain of 0.1 %, a frequency-dependent measurement was conducted. In this experiment, the frequency was increased from 0.01 Hz to 100 Hz. Lastly, an amplitude sweep was conducted. In the strain-dependent measurement, the frequency was kept at 1 Hz and the strain was increased from 0.1 to 1000 %. To analyze the reproducibility of the results, the measurements were conducted twice.

5.2. Cell Culture and Capillary Formation In Vitro

Experiments were performed with mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) and human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) isolated by protocols well established in the group [

17].

Prepared hydrogels were covered with 4*10

4 MSC in 400 µL SCM per well and incubated (37° C, 5% CO

2) for two days. Then, 4*10

4 HUVEC in 400 µL EGM-2 were seeded on top of the MSC layer (2D approach). Three different approaches with (i) 6 µL VEGF (2.5 µg/mL) per well, (ii) 5 µL Suramin (1 mM) per well and (iii) untreated control were investigated in triplicates [

18,

19]. VEGF acts as a stimulator and suramin as an inhibitor of angiogenesis. After HUVEC seeding, cells were incubated for two hours to allow for adherence before the respective angiogenesis stimulating or inhibiting factor was added. Medium and VEGF/suramin supplementation were renewed every other day until fixation after seven days of co-culture. For experiments on cells inside the gel, the cell density was adjusted to 5.25 * 10

5 cells/mL for each cell type, gel volumes were increased to 350 µL per well; the ratio of the individual components remained unaltered (3D approach;

Figure 11).

5.3. Immunofluorescence Staining and Microscopy

Samples were fixed with 4% PFA for 60 minutes. Samples were washed with PBS for 45 minutes, blocked with 3% BSA for 60 minutes and again washed with PBS for 5 minutes. The primary antibody (mouse anti-human anti-CD31, 1:400 in 1% BSA) was added, samples were incubated at 37°C for 60 minutes and subsequently washed with PBS at 4°C overnight. The secondary antibody (goat anti-mouse labelled with Alexa Flour 488) was applied and washed under avoidance of light exposure. Samples were treated with DAPI solution (1 µg/ml) for 5 minutes, then washed three times with PBS and stored at 4°C until image acquisition at the microscope. Per cavity on a 24-well plate, 400 µl PFA, PBS and 3% BSA were pipetted; the dilutions of the first and second antibody were used at volumes of 200 µl per well. Unless indicated differently, all steps were carried out at room temperature. The third well of each approach was used as a control for autofluorescence and unspecific binding and was as such only treated with the secondary antibody. When HUVEC were seeded inside the gels, the incubation with the primary and secondary antibody was extended to an overnight incubation. For qualitative analysis, three images, roughly on one line from left to right, were taken per well at 100x magnification at the fluorescence microscope. One image was taken per control well. For quantitative analysis, five images per well were taken in positions that were set in advance to sample inspection.

To assess the gel ultrastructure and lumen formation in capillary-like structures, samples were also visualized by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Visible remnants on SEM images were characterized using energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX).

5.4. VEGF Detection

During the angiogenesis assays, supernatant medium was collected every second day after the seeding of MSC. One pooled sample was collected for each approach; VEGF concentration was measured in duplicate by ELISA. Maxisorp-plates (96-well) were coated with capture antibody overnight and the ELISA was carried out according to the manufacturer’s protocol (R&D Systems, Wiesbaden, Germany).

5.5. Quantification and Statistical Analysis

Images were processed in GIMP 2.10.12 to remove background and cell monolayers and to create an inverted binary image of the present capillary-like structures. MATLAB AngioQuant was used to analyze the total length of the network in pixels as well as the total number of junctions. Threshold settings in AngioQuant were adjusted manually (low threshold: 130, high threshold: 200) to ensure that all structures were recognized in the skeletonized images. The same fixed thresholds were applied to all images in the batch analysis. Directionality analysis was carried out using the directionality plugin for ImageJ. GraphPad Prism 9.1.2 was used for graphs and statistical analyses. Two-way ANOVA was applied (α = 0.05) with a Tukey post-hoc test.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Svenja Wein; Data curation, Carina Schemmer; Formal analysis, Svenja Wein and Carina Schemmer; Funding acquisition, Sabine Neuss; Investigation, Svenja Wein, Carina Schemmer, Miriam Al Enezy-Ulbrich and Shannon Jung; Methodology, Svenja Wein and Carina Schemmer; Project administration, Sabine Neuss; Supervision, Danny Jonigk, Wilhelm Jahnen-Dechent, Andrij Pich and Sabine Neuss; Validation, Stephan Rütten; Visualization, Svenja Wein, Carina Schemmer and Miriam Al Enezy-Ulbrich; Writing – original draft, Svenja Wein; Writing – review & editing, Carina Schemmer, Miriam Al Enezy-Ulbrich, Shannon Jung, Danny Jonigk, Wilhelm Jahnen-Dechent, Andrij Pich and Sabine Neuss.

Svenja Wein, Carina Schemmer, Andrij Pich and Sabine Neuss contributed equally to this work.

Funding

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) in the framework of the joint project “Towards a model-based control of biohybrid implant maturation” (PAK961) by the grant NE 1650/4-2 and PI 614/13-2.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Human cells were isolated according to approvals (EK 300/13; EK 116/19) of our local ethics committee.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Vytautas Kucikas for the preparation of the 2-photon microscopic images. The authors thank the Clinic for Orthopaedic Surgery for providing bone spongiosa to isolate human mesenchymal stem cells and the Clinic for Gynaecology and Obstetrics assistance for providing umbilical cords. The authors acknowledge Prof. Dr. Arnold Gillner from Fraunhofer ILT Aachen for producing Figures 1, 10 and 11 using the BioRender software.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kim, B.S., and Mooney, D.J., Development of biocompatible synthetic extracellular matrices for tissue engineering. Trends Biotechnol 16, 224, 1998. [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.-A., Lee, H.-Y., Lee, J.H., Kim, T.-H., Jang, J.-H., Kim, H.-W., and Wall, I., Collagen three-dimensional hydrogel matrix carrying basic fibroblast growth factor for the cultivation of mesenchymal stem cells and osteogenic differentiation. Tissue Eng Part A 18, 1087, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Park, J.S., Chu, J.S.F., Cheng, C., Chen, F., Chen, D., and Li, S., Differential effects of equiaxial and uniaxial strain on mesenchymal stem cells. Biotechnol Bioeng 88, 359, 2004. [CrossRef]

- Rouwkema, J., Rivron, N.C., and van Blitterswijk, C.A., Vascularization in tissue engineering. Trends Biotechnol 26, 434, 2008. [CrossRef]

- Rouwkema, J., and Khademhosseini, A., Vascularization and Angiogenesis in Tissue Engineering: Beyond Creating Static Networks. Trends Biotechnol 34, 733, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Mastrullo, V., Cathery, W., Velliou, E., Madeddu, P., and Campagnolo, P., Angiogenesis in Tissue Engineering: As Nature Intended? Front Bioeng Biotechnol 8, 188, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Malda, J., Rouwkema, J., Martens, D.E., Le Comte, E.P., Kooy, F.K., Tramper, J., van Blitterswijk, C.A., and Riesle, J., Oxygen gradients in tissue-engineered PEGT/PBT cartilaginous constructs: measurement and modeling. BIOTECHNOL BIOENG 86, 9, 2004. [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, F.M., Callanan, A., Kavanagh, E.G., Burke, P.E., Grace, P.A., and McGloughlin, T.M., Fibrin: a natural biodegradable scaffold in vascular tissue engineering. Cells Tissues Organs 188, 333, 2008. [CrossRef]

- La Puente, P. de, and Ludeña, D., Cell culture in autologous fibrin scaffolds for applications in tissue engineering. Exp Cell Res 322, 1, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Bienert, M., Hoss, M., Bartneck, M., Weinandy, S., Böbel, M., Jockenhövel, S., Knüchel, R., Pottbacker, K., Wöltje, M., Jahnen-Dechent, W., and Neuss, S., Growth factor-functionalized silk membranes support wound healing in vitro. Biomed Mater 12, 45023, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Park, C.H., and Woo, K.M., Fibrin-Based Biomaterial Applications in Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine. Adv Exp Med Biol 1064, 253, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Ye, Q., Zünd, G., Benedikt, P., Jockenhoevel, S., Hoerstrup, S.P., Sakyama, S., Hubbell, J.A., and Turina, M., Fibrin gel as a three dimensional matrix in cardiovascular tissue engineering. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 17, 587, 2000. [CrossRef]

- Hokugo, A., Takamoto, T., and Tabata, Y., Preparation of hybrid scaffold from fibrin and biodegradable polymer fiber. Biomaterials 27, 61, 2006. [CrossRef]

- Su, X., Wang, T., and Guo, S., Applications of 3D printed bone tissue engineering scaffolds in the stem cell field. Regen Ther 16, 63, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Al Enezy-Ulbrich, M.A., Malyaran, H., Lange, R.D., Labude, N., Plum, R., Rütten, S., Terefenko, N., Wein, S., Neuss, S., and Pich, A., Impact of Reactive Amphiphilic Copolymers on Mechanical Properties and Cell Responses of Fibrin-Based Hydrogels. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 2003528, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Peng, H., Rübsam, K., Hu, C., Jakob, F., Schwaneberg, U., and Pich, A., Stimuli-Responsive Poly(N-Vinyllactams) with Glycidyl Side Groups: Synthesis, Characterization, and Conjugation with Enzymes. Biomacromolecules 20, 992, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Neuss, S., Becher, E., Wöltje, M., Tietze, L., and Jahnen-Dechent, W., Functional expression of HGF and HGF receptor/c-met in adult human mesenchymal stem cells suggests a role in cell mobilization, tissue repair, and wound healing. Stem Cells 22, 405, 2004. [CrossRef]

- Meyers, M.O., Gagliardi, A.R., Flattmann, G.J., Su, J.L., Wang, Y.Z., and Woltering, E.A., Suramin analogs inhibit human angiogenesis in vitro. J Surg Res 91, 130, 2000. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, S.M., Siegman, S.N., and Segura, T., The effect of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) presentation within fibrin matrices on endothelial cell branching. Biomaterials 32, 7432, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Ceccarelli, J., Cheng, A., and Putnam, A.J., Mechanical strain controls endothelial patterning during angiogenic sprouting. Cell Mol Bioeng 5, 463, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Hadjizadeh, A., and Doillon, C.J., Directional migration of endothelial cells towards angiogenesis using polymer fibres in a 3D co-culture system. J Tissue Eng Regen Med 4, 524, 2010. [CrossRef]

- McCoy, M.G., Wei, J.M., Choi, S., Goerger, J.P., Zipfel, W., and Fischbach, C., Collagen Fiber Orientation Regulates 3D Vascular Network Formation and Alignment. ACS Biomater Sci Eng 4, 2967, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Morin, K.T., Dries-Devlin, J.L., and Tranquillo, R.T., Engineered microvessels with strong alignment and high lumen density via cell-induced fibrin gel compaction and interstitial flow. Tissue Eng Part A 20, 553, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Sukmana, I., and Vermette, P., The effects of co-culture with fibroblasts and angiogenic growth factors on microvascular maturation and multi-cellular lumen formation in HUVEC-oriented polymer fibre constructs. Biomaterials 31, 5091, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Kniebs, C., Kreimendahl, F., Köpf, M., Fischer, H., Jockenhoevel, S., and Thiebes, A.L., Influence of Different Cell Types and Sources on Pre-Vascularisation in Fibrin and Agarose-Collagen Gels. Organogenesis 16, 14, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Oh, H.H., Lu, H., Kawazoe, N., and Chen, G., Spatially guided angiogenesis by three-dimensional collagen scaffolds micropatterned with vascular endothelial growth factor. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed 23, 2185, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Farrukh, A., Paez, J.I., and del Campo, A., 4D Biomaterials for Light-Guided Angiogenesis. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, 1807734, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Grainger, S.J., and Putnam, A.J., Assessing the permeability of engineered capillary networks in a 3D culture. PLoS One 6, e22086, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Andrée, B., Ichanti, H., Kalies, S., Heisterkamp, A., Strauß, S., Vogt, P.-M., Haverich, A., and Hilfiker, A., Formation of three-dimensional tubular endothelial cell networks under defined serum-free cell culture conditions in human collagen hydrogels. Sci Rep 9, 5437, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Azari, Z., Nazarnezhad, S., Webster, T.J., Hoseini, S.J., Brouki Milan, P., Baino, F., and Kargozar, S., Stem cell-mediated angiogenesis in skin tissue engineering and wound healing. Wound Repair Regen 30, 421, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Veith, A.P., Henderson, K., Spencer, A., Sligar, A.D., and Baker, A.B., Therapeutic strategies for enhancing angiogenesis in wound healing. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 146, 97, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Werlein, C., Ackermann, M., Stark, H., Shah, H.R., Tzankov, A., Haslbauer, J.D., Stillfried, S. von, Bülow, R.D., El-Armouche, A., Kuenzel, S., Robertus, J.L., Reichardt, M., Haverich, A., Höfer, A., Neubert, L., Plucinski, E., Braubach, P., Verleden, S., Salditt, T., Marx, N., Welte, T., Bauersachs, J., Kreipe, H.-H., Mentzer, S.J., Boor, P., Black, S.M., Länger, F., Kuehnel, M., and Jonigk, D., Inflammation and vascular remodeling in COVID-19 hearts. Angiogenesis 26, 233, 2023. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).