1. Introduction

The health-promoting effects of bioactive peptides have made them standout as natural and harmless candidates for the development of functional foods and nutraceuticals. Their significance becomes apparent when considering their biological roles in the human body and nutritional value due to their content of essential amino acids [

1]. Bioactive peptides from marine sources exert a wide spectrum of biological effects on cardiovascular, immune, nervous, and gastrointestinal systems [

2]. However, coming mostly from fish and mollusks, most marine-derived proteins and peptides are not accepted by vegan and vegetarian communities. Therefore, using marine sources of bioactive nutrients that are also compatible with standards of these communities could be a research priority.

Seaweed has traditionally been considered as a source of food consumed either directly or as a food supplement with medicinal effects. It has been documented that local inhabitants near shores of many parts of the world have harvested seaweeds and used them as home remedies and natural marine drugs for treating different diseases [

3]. In recent years, advancements in the study of natural products derived from marine algae have revealed their potential as valuable sources of bioactive compounds with potential medicinal applications [

4,

5]. The red seaweed dulse (

Palmaria palmata) is regarded for its appealing taste with a potential in culinary applications both as a stand-alone food and as an ingredient. This seaweed species is abundant in the cold Atlantic waters and can be [

6] harvested from the wild or cultivated in sea and land-based pools [

7].

P. palmata has been introduced as a viable alternative source of nutrients such as proteins and peptides [

8] with possible medicinal effects [

9,

10]. For instance, it was shown that peptides obtained by protein hydrolysis could potentially be used in the formulations of pharmaceuticals and nutraceuticals as an antidiabetic agent [

10]. A recent study even discovered the role of nutrients in the seaweed to make it a promising prebiotic to be potentially used as a neuroprotective agent in multiple sclerosis patients [

11].

Despite the bioactivity and health benefits of proteins and peptides from the seaweed, their extraction from the species is not a straightforward process, mainly due to its rigid cell wall with its complex backbone comprising polysaccharides, proteins, and polyphenols [

6], which poses a challenge to reach intracellular nutrients. One remedy to overcome this barrier is the application of polysaccharidase to disintegrate the cell wall, which has been reported to yield favorable protein recovery from the seaweed. For instance, it was shown that application of a polysaccharidase along with a protease in the aqueous solution and sequentially performed alkaline extraction would facilitate a favorable recovery of protein from this seaweed [

8]. Since proteins are hydrolyzed during enzymatic/alkaline extraction, the resulting extract should contain bioactive peptides of smaller sizes and even free amino acids. Peptides and amino acids in protein hydrolysates from other sources were shown to have antioxidant properties [

12]. Likewise, peptides obtained from other seaweed species have also been demonstrated to have antioxidative properties [

13]. It is noteworthy that the extracts obtained from seaweeds could also act as antioxidants via other nutrients such as phenolic compounds and therefore, there are still controversies on whether antioxidant properties of seaweed-derived extracts, either in terms of radical scavenging or metal chelation, originated from peptides and amino acids or polyphenols or even other nutrients such as polysaccharides [

14].

In addition, all the studies analyzing the antioxidant effects of seaweed extracts applied the crude extract, whether as a liquid fraction or powdered form, without further treatment. However, we hypothesized that the crude extract obtained after enzymatic/alkaline extraction could potentially exert more favorable effects with further treatment.

Ultrasonication is reputable as a green treatment technique with a wide array of applications. Ultrasonication has been used as an assistance during alkaline extraction of protein from plants [

15]; however, to the best of our knowledge, there has been no report on the effect of ultrasonication on seaweed (or even plant) extracts after extraction. The theoretical framework in this study regarding the effect of ultrasonicating the extracts after extraction when the biomass is practically removed is as follows: (i) stabilization of extracted bioactive compounds by preserving them from degradation; (ii) smaller size of bioactive compounds that improves their solubility, bioavailability, and bioactivity; (iii) disruption of aggregates and crystalline structure that would increase their availability in the treated extracts; (iv) degassing effect of ultrasonication that would remove dissolved gases such as oxygen from the extracts contributing to higher stability in terms of the oxidation of bioactive compounds; and (v) further release of bioactive compounds from unknown agglomerated structures such as cell remnants. Additionally, there are generally two distinct methods for ultrasonication, i.e., bath and probe, which are known to exert ultrasonic energy in different ways and thus, yield different results [

16]. Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate whether ultrasonication treatment of

P. palmata extracts obtained by combined enzymatic/alkaline extraction would improve the antioxidative properties of the extract. A second aim was to compare two different ultrasonication methods: ultrasound bath versus ultrasound probe at two different treatment times.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Protein Content, Degree of Hydrolysis, Protein Recovery, and Nitrogen-to-Protein Conversion Factor

The protein content of freeze-dried seaweed and enzymatic/alkaline extracts (% dry matter), degree of hydrolysis (DH), and protein recovered in hydrolysates and remained in solid residues collected after enzymatic hydrolysis and alkaline extraction are presented in

Table 1. The dried seaweed’s protein content corresponded with the harvest season of the P. palmata. The seaweed studied in the present study was obtained from a batch harvested in a period between late spring and early autumn when the protein content is expected to be the lowest due to limited water nutrients during these months and destructive effect of sunlight on proteins [

17]. Furthermore, protein recovered in hydrolysates and solid residues were found to be circa 91-94% and 3-5%, respectively. No significant difference was detected in terms of protein recovery both in hydrolysates and solid residues (p>0.05).

Unrealistic reports of protein content in

P. palmata (e.g., 35%) can be found in literature, which should be taken with care due to the possible risk of overestimation when applying the nitrogen-to-protein conversion factor of 6.25 (compared with 5 considered in this study) [

18]. This discrepancy in protein content of

P. palmata could be owing to the presence of non-protein nitrogenous compounds such as ammonium salts, amines, and nitrates [

19].

Table 2 provides a comparison of protein contents of dried seaweed and enzymatic/alkaline extracts considering three conversion factors (6.25, 5, and 4) and accurate protein content and conversion factor obtained considering the estimated total amino acids. The results of this study in terms of amino acid contents (See

Section 2.3) revealed that the conversion factor of 4.6-4.7 could be a viable choice for estimation of protein content of

P. palmata extracts obtained through sequential enzymatic and alkaline treatments. It has been stated that direct amino acid analysis resonates the most accurate method of protein quantification, especially in emerging alternative protein sources such as seaweeds, and provides a ground on which the accuracy of other methods such as Kjeldal and DUMAS may be biased [

20]. Nevertheless, it is noteworthy that the method taken in the present study to measure amino acid content does not determine all amino acids. Furthermore, the gained water during protein hydrolysis stage should also be considered to adopt total amino acid content as a measure for protein content. As can be seen in

Table 2, considerably lower nitrogen-to-protein conversion factors were obtained by accounting for the water gained during protein hydrolysis to measure protein content based on total amino acid in the biomass and hydrolysates. The conversion factor was calculated to be 4.54 for the dried seaweed and 3.91-4.20 for the hydrolysates. Therefore, one should think twice before calculating the protein content and consequently protein recovery in seaweed (or at least

P. palmata) extracts via the nitrogen-to-protein conversion factor of 5, because the results of the present study revealed that the conversion factor of 5 might overestimate the actual protein content in seaweed extracts and even in raw biomass. It is worth noting that the conversion factors calculated here are for the hydrolysates obtained after sequential enzymatic and alkaline treatments, whereas another study determining conversion factors of enzymatically obtained (yet by using different enzymes) hydrolysates (i.e., without the pursuing alkaline extraction) reported much lower conversion factors for liquid extracts ranging from 2.5 to 3.6 [

19]. It needs to be evaluated whether these differences are due to the additional alkaline extraction stage in this study or different choices of enzymes in the present study (Celluclast + Alcalase) versus the above-mentioned research (Xylanase, Xylanase + Umamizyme, and Umamizyme). It is noteworthy that the conversion factor for freeze-dried

P. palmata in the above study (i.e., 4.7) was quite comparable to the ones calculated in the current research (i.e., 4.8 or 4.54 as explained above), which downplays the risk of discrepancies caused by external factors such as accuracy of measurements and/or human errors.

DH of the hydrolysates ranged between circa 25% and 33%; however, no significant difference was detected among the samples in terms of DH (p>0.05). Data on the degree of hydrolysis for seaweed is sparse, which makes it challenging to make comparisons in terms of enzymes adopted, species of seaweed, and hydrolysis conditions such as time, temperature, and pH. However, Alcalase has been reported to yield favorable DH when used to hydrolyze protein from different sources [

21]. Research is required to discover the effect of using different enzymes simultaneously or sequentially on the degree of hydrolysis. Furthermore, since a polysaccharidase was used here to disintegrate the cell wall of the seaweed to facilitate the protein hydrolysis by the protease, possible synergism and/or antagonism between the protease and polysaccharidase in terms of their effect on degree of hydrolysis merit consideration.

A substantial amount of protein in the raw material was recovered in the hydrolysates as evidenced by >91% protein recovery in all the samples. In a previous study from our lab [

8] where pH was shifted from approximately 13 to 3 after combined enzymatic/alkaline extraction, the protein recovery in the liquid fractions (as called hydrolysates in the present study) ranged between circa 56% and 70% when Alcalase was used in combination with other enzymes such as Celluclast. The results indicate that pH adjustment of the resulting slurry after enzymatic and alkaline treatments to a range between 8.5 and 9 contributed to the solubility of a significant quantity of resulting peptides and amino acids. The pH range of 8-9 was recommended as the most favorable range for protein solubility, since proteins have zero charge at their isoelectric point and form zwitterion structures leading to protein aggregation and thus, minimized solubility [

22]. The substantial increase in solubility of seaweed protein in enzymatic/alkaline extracts may be attributed to different factors. The high ionic strength resulting from mineral content may contribute to elevated solubility of proteins at alkaline pH [

23]. Additionally, availability of hydrophobic and free sulfhydryl groups for interaction as a result of protein unfolding via the increased mutual repulsion forces in the polypeptide chains as well as the increased participation of cysteine in thiol-disulphide exchange reactions may improve protein solubility at alkaline pH [

22]. The latter is potentially supported by the results of amino acid analysis in the present study showing that cystine, which was literally absent in the raw material, formed approximately 11-13% of total amino acids in the hydrolysates (

Table 3). It was hypothesized that ultrasonication of the enzymatic/alkaline extracts, either by ultrasonic bath or ultrasound probe, would further improve protein solubility by fueling intermolecular interactions that brings about the conformational changes in secondary structure of peptides exposing hydrophilic regions to water [

24]; however, no significant difference was seen here in protein recovered in the hydrolysates obtained with or without ultrasonication of the extracts (p>0.05). This could be accounted for by the overshadowing effect of pH that had already solubilized the highest possible quantity of protein and peptides before ultrasonication.

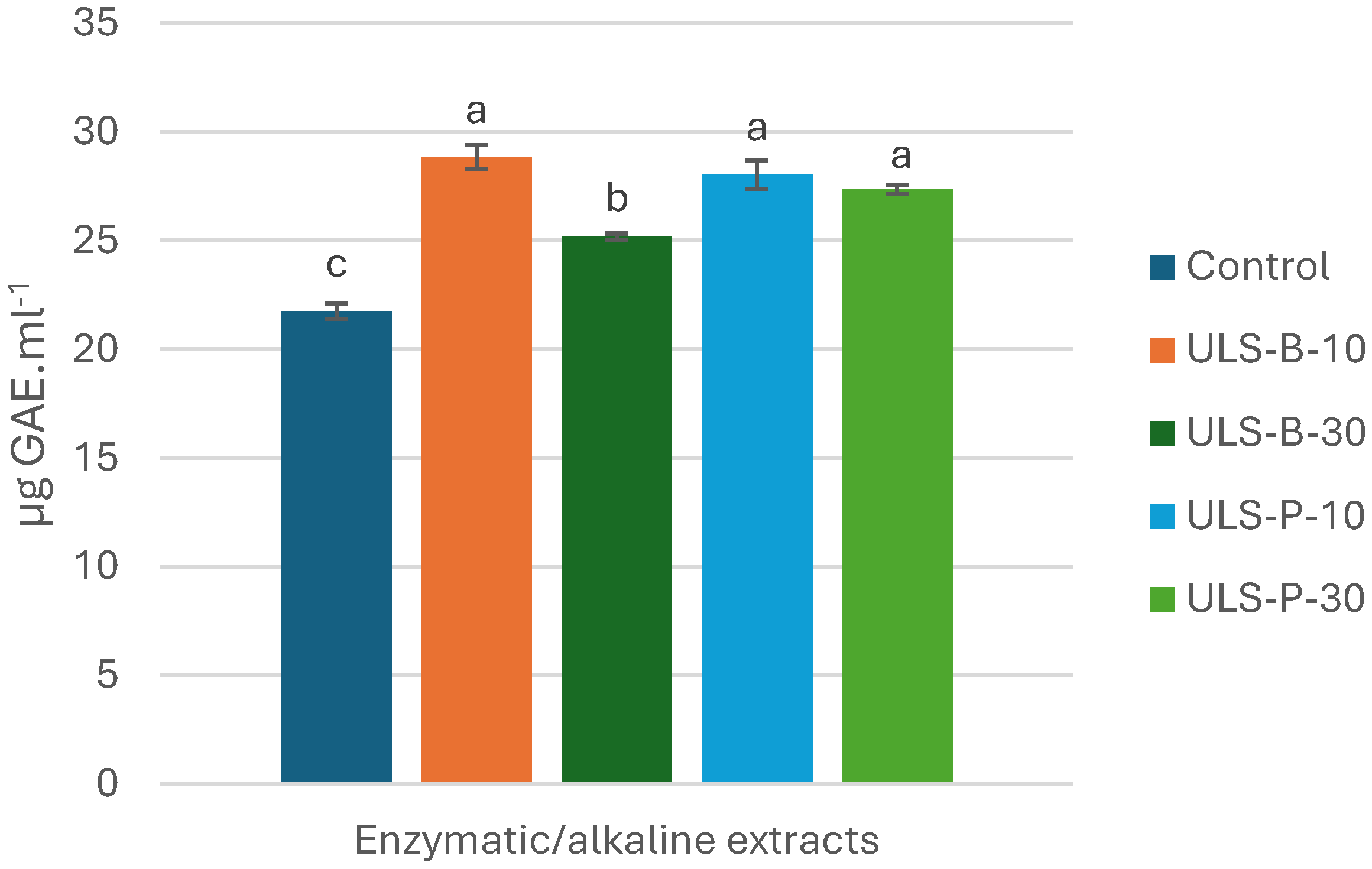

2.2. Total Phenolic Compounds

The content of total phenolic compounds (TPC) underwent considerable change after ultrasonication of the resulting enzymatic/alkaline extracts (

Figure 1). TPC in the control sample (no ultrasonication) was significantly lower than that in ultrasonicated enzymatic/alkaline extracts (p<0.05). The highest TPC was found in ULS-B-10 (ultrasonic bath for 10 min), but it was not significantly different from values obtained in enzymatic/alkaline extracts ultrasonicated using a probe for 10 and 30 minutes (p>0.05). However, TPC of ULS-B-30 (ultrasonic bath for 30 min) was significantly lower than that of other ultrasonicated extracts (p<0.05), but still significantly higher than that of control (p<0.05), which further highlighted the substantial effect of ultrasonication on the content of phenolic compounds of the extracts.

Several studies have emphasized the efficiency of ultrasound-assisted extraction on achieving substantial quantity of phenolic compounds [

25], but this may not be relevant here because ultrasound in this study was applied on the extracts after sieving out the biomass. Therefore, it is unlikely that significantly higher TPC in the ultrasonicated extracts would be owing to the effect of ultrasound on the disintegration of seaweed cell walls since intact cells are less likely to be present in the extracts after removing the solid residue through sieving. One explanation for this observation in the present study is that although intact cells may not exist after removing the biomass, there might still be residual cellular structures or compounds that are trapped in cellular remnants that are soluble at alkaline pH. Therefore, through the generation of mechanical forces, ultrasound treatment can further break down these remnants and consequently enhance the release of phenolic compounds. This additional disruption may lead to the elevated recovery of phenolic compounds and justify the observed significant differences between control and ultrasonicated extracts. Another explanation could be the fact that ultrasonication could have yielded smaller peptides and free amino acids, thereby reducing the interactions of protein and algal polyphenols that would otherwise have led to the formation of polyphenol-protein complexes through hydrogen bonding, π-bonding, hydrophobic interactions, and ionic and covalent linkage [

26]. Moreover, the Folin-Ciocalteu reagent not only reacts with phenolic compounds but could also react with amino acids containing free hydroxyl groups such as serine, threonine, tyrosine, and glutamic acid. Therefore, a third explanation could be that these amino acids became more accessible for reaction with the Folin-Ciocalteu reagent after ultrasonication treatment.

Moreover, the observed significant decrease in TPC after ultrasonication through ultrasonic bath for longer duration (which was not seen in extracts treated with ultrasound probe) might be rooted in differences in the distribution of ultrasonic energy through bath and probe. In ultrasonic bath, the ultrasonic energy is unevenly spread, which leads to an uncontrolled and less localized distribution of the sonication effect compared to ultrasound probes [

16]. Therefore, upon extended exposure of the extract in ultrasonic bath, sensitive phenolic compounds might be exposed to degradation. However, more localized distribution of ultrasonic energy using ultrasound probe could minimize the risk of the degradation of susceptible phenolic compounds, even if longer ultrasonication times are considered.

2.3. Amino Acid Composition

Table 3 summarizes the amino acid composition of freeze-dried seaweed and enzymatic/alkaline extracts with or without following ultrasonication either by ultrasonic bath or ultrasound probe. Most of the amino acids were present in the raw material and hydrolysate, except for tryptophan and cysteine (destroyed and converted to cystine, respectively, during acid hydrolysis), as well as hydroxyproline, which is consistent with the results of a study on enzyme-assisted protein extraction from

P. palmata [

8]. Furthermore, histidine was detected in the freeze-dried seaweed, while it was absent in the hydrolysates, which could be related to the imidazole ring of this amino acid. The imidazole ring of histidine is known to be the only amino acid side chain in proteins to act as a pH buffer, where two nitrogen molecules of the ring are capable of protonation or deprotonation to generate the acid or base forms [

27]. The change in the protonation state of histidine could bring about alterations in histidine structure and even degradation, which might contribute to its disappearance in the hydrolysates. In addition, cystine was found to be significantly higher in hydrolysates than in free-dried seaweed, which is likely to be due to the use of NAC as a reducing agent during alkaline extraction stage [

8].

In terms of the influence of ultrasonication through bath or probe on amino acid composition, it was witnessed that prolonged exposure of extracts to ultrasonic energy in the bath caused the reduction of all amino acids in hydrolysates (

Table 3). However, there were fluctuations in the quantity of amino acids when comparing the hydrolysates obtained after 10 and 30 minutes of ultrasonication by probe, which is in line with the results of TPC (see section 2.2). Uneven distribution of ultrasound energy in the bath might have led to the partial degradation of amino acids in the hydrolysate. In addition, the ratio of essential to non-essential amino acids considerably increased from almost 35% in the raw material to approximately 42% in hydrolysates (

Table 3), which indicates the role of enzymatic/alkaline treatment on increased quantity of essential amino acids in the resulting extracts. Improved ratio of essential to non-essential amino acids after sequential treatment of

P. palmata through enzymatic and alkaline processes was also observed by Mæhre et al. [

28]. It should be noted that although prolonged ultrasonication, whether by bath or probe, led to the decreased quantity of amino acids in hydrolysates, it did not cause a considerable change in the ratio of essential to non-essential amino acids in hydrolysates.

2.4. In Vitro Antioxidant Properties

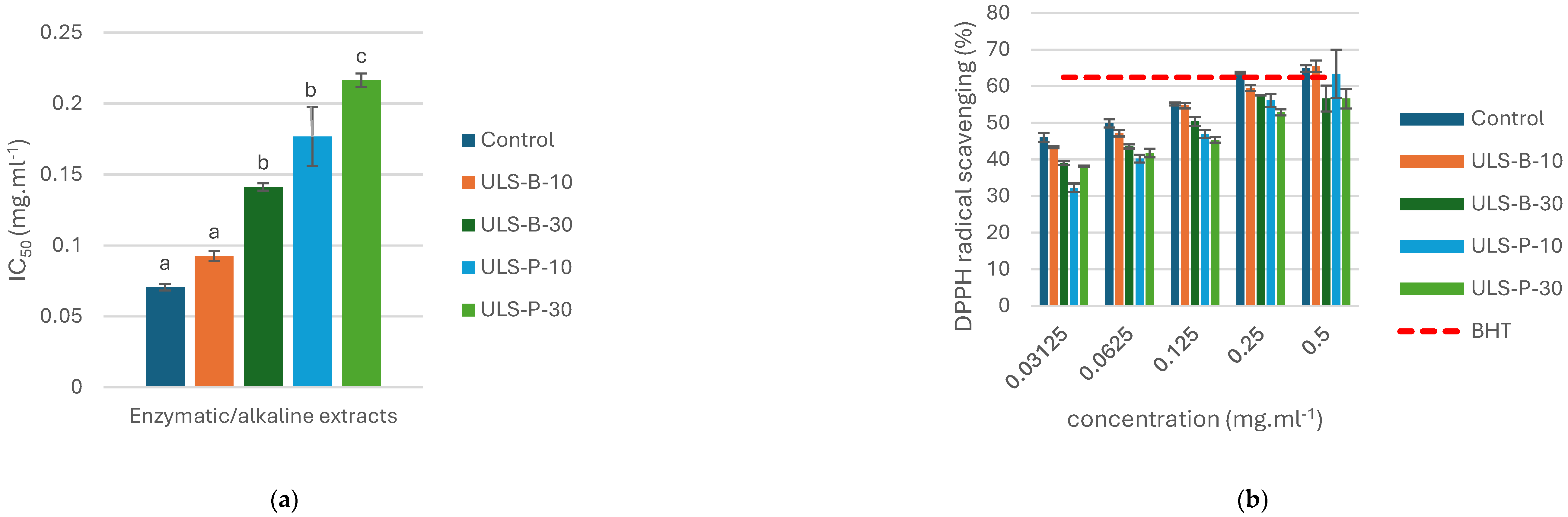

2.4.1. 1,1-Diphenyl-2-Picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) Radical Scavenging Activity

Figure 2a depicts the IC

50 values for DPPH radical scavenging activity of the enzymatic/alkaline extracts. The strongest DPPH radical scavenging activity was observed for the extracts obtained without ultrasonication or ultrasonicated for 10 minutes in bath with IC

50 values lower than 0.1 mg.ml

-1 (p<0.05). Continuing ultrasonication in bath for 30 minutes resulted in significant increase in IC

50 value and therefore, substantial decrease in DPPH radical scavenging activity of the extract (p<0.05). Ultrasonication using probe significantly decreased DPPH radical scavenging activity of the extracts compared with the ones with no ultrasonication or ultrasonication in bath for 10 minutes (p<0.05). Moreover, the results revealed that DPPH radical scavenging activity of the extract ultrasonicated for 30 minutes using probe was significantly lower than that of other samples, as evidenced by significant differences in IC

50 values of this extract with its counterparts (p<0.05). DPPH radical scavenging activity of enzymatic/alkaline extracts incremented dose-dependently (

Figure 2b). In this study, butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT) at the concentration of 0.2 mg.ml

-1 was used as a positive control. When applied at 0.25 mg.ml

-1, only control sample reached the same DPPH radical scavenging activity of the positive control. However, at higher concentration of 0.5 mg.ml

-1, in addition to control, the extracts ultrasonicated (whether by bath or probe) for 10 minutes also reached almost the same DPPH scavenging activity of BHT (0.2 mg.ml

-1).

DPPH scavenging activity of enzymatic/alkaline extracts of

P. palmata was attributed to its content of phenolic compounds and low molecular weight peptides and amino acids [

26]. However, the significant differences observed in the present study do not correspond with TPC content of the extracts. Furthermore, ultrasonication using probe is supposed to exert more localized sonication energy to the extracts, which in theory should lead to the formation of peptides with lower molecular weight. Therefore, there could be other attributes contributing to significantly higher DPPH activity of control and ULS-B-10 compared with other extracts. One explanation could be the fact that the decline in cystine content in the extracts corresponded to dipped DPPH radical scavenging activity. As cystine levels dropped, the IC

50 values soared, indicating a probable direct correlation between cystine content of the hydrolysates and their effectiveness in scavenging DPPH radicals. Accordingly, it was stated that phenolic compounds would have synergistic effect with S-allyl-L-cysteine, a cysteine derivative, and exhibit strong DPPH radical scavenging activity [

29]. Cysteine is a sulfur-containing amino acid characterized by its thiol group, and it is known to have biological activity in terms of its antioxidant properties, while cystine is the dimeric form of cysteine, resulting from the oxidation of two cysteine molecules, and it may exhibit similar properties to cysteine [

30]. Nevertheless, one might propose that this justification seems too good to be true, given the fact that the differences in the content of cystine among the hydrolysates is not significant (p>0.05). Another explanation is the possibility of degradation of bioactive compounds during ultrasonication using probe due to the elevated degassing effect as well as changes in characteristics of medium as a result of the heating caused by ultrasonic probe [

16]. As to the present study, removal of gases from the extracts might have caused cavitation bubbles, which generated intense localized energy and mechanical stress that might have degraded susceptible bioactive compounds in the extracts and led to noticeably lower DPPH radical scavenging activity.

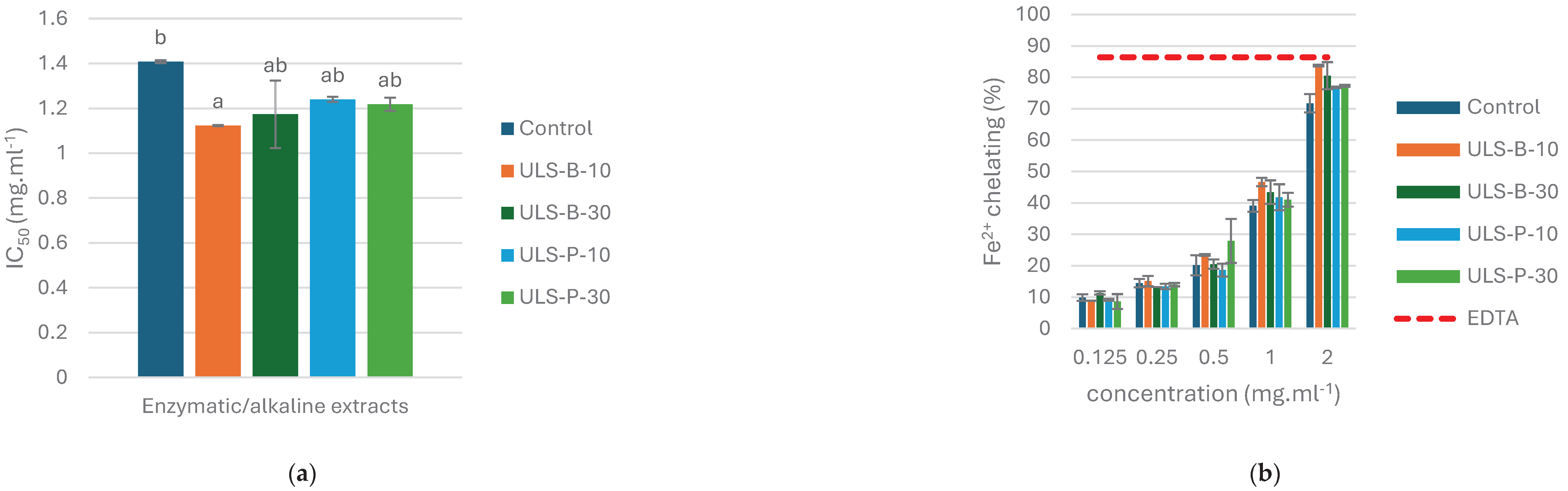

2.4.2. Fe2+ Chelating Activity

The IC

50 values of the extracts to chelate Fe

2+ are illustrated in

Figure 3a. In contrast to DPPH radical scavenging activity, the lowest Fe

2+ chelating activity was detected in control sample, which had no significant difference with samples ultrasonicated for 30 minutes in bath and both samples ultrasonicated in probe (p>0.05). Conversely, a significant difference was witnessed in the iron chelating activity of samples without ultrasonication and ultrasonicated for 10 minutes in bath (p<0.05). As expected, the iron chelating activity of the extracts showed a direct correlation with the dose applied (

Figure 3b). In the present study, 0.06 mM ethylene diamine tetra acetic acid (EDTA) was considered as a positive control and showed high Fe

2+ chelating activity. None of the extracts, even when tested at the concentration of 2 mg.ml

-1, could reach the threshold defined by the iron chelating activity of the positive control.

Metal ion chelating activity could be attributed to peptides and amino acids in any given extract with some studies stating that low molecular weight peptides are responsible for Fe

2+ chelating activity [

31], whereas other studies mentioned high molecular weight peptides to be more effective iron chelators [

26]. It was reported that phenolic compounds in

P. palmata extracts are not effective metal chelators [

26], which contrasts with the results obtained in the present study. Fe

2+ chelating activity of the extracts here corresponds to the TPC concentrations (

Figure 1). TPC content in the sample ultrasonicated in bath for 10 minutes is significantly higher than that in control (p<0.05), which is directly correlated with significantly lower IC

50 value of this sample compared with that of control. Moreover, as stated in

Section 2.4.1, synergy between phenolic compounds and cysteine derivatives may contribute to higher DPPH radical scavenging activity. One might consider that a similar synergy would also account for higher metal chelation; however, the possibility of such a synergistic effect in terms of metal chelation remains to be elucidated. In addition, this interpretation should be taken with care, because in order for compounds to be considered efficient metal chelators, they need to possess functional groups such as hydroxyl (-OH), thiol (-SH), carboxyl (-COOH), phosphoric acid (-PO

3H

2), carbonyl (C═O), amino (-NR

2), sulfide (-S-), or ether (-O-), while majority of phenolic compounds only contain hydroxyl group [

32]. The discrepancy existing in literature on the role of polyphenol in the metal chelating activity of seaweed extracts was also reported elsewhere [

14]. With respect to the present study, the better chelating activity of ultrasonicated extracts could alternatively be due to the formation of shorter peptides with lower molecular weights or the release of other compounds such as phospholipids (which are mentioned as good metal chelators [

32]) from cell remnants after ultrasonication.

2.4.3. In Vitro Antioxidant Activity of Enzymatic/Alkaline Extracts versus Other Types of Extracts

Table 4 provides a comparative overview of IC

50 values for the in vitro antioxidant activities obtained here in this study by using enzymatic/alkaline extracts and ethanol, water, chloroform, ethyl acetate, and methanol extracts from

P. palmata reported in other studies. As can be seen, IC

50 values for DPPH radical scavenging in the present study for all extracts are substantially lower than those for ethanol and water extracts [

14] as well as for chloroform, ethyl acetate, and methanol extracts [

33]. However, IC

50 values for Fe

2+ chelating activity in ethanol and chloroform extracts were lower than the ones obtained in the present study with enzymatic/alkaline extracts. Considering the enzymatic treatment performed here using polysaccharidase and protease and possibility of formation of amino acids and peptides with low molecular weight, it seems affordable to conclude that peptides in seaweed (or at least in

P. palmata) extracts are to be cherished for their radical scavenging role. However, apparently, the effect of other compounds such as phospholipids, polysaccharides, and/or polyphenols to chelate metal ions outweigh that of proteins, peptides, and amino acids in different seaweed extracts.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Seaweed Biomass Preparation

Air-dried P. palmata obtained from a batch harvested in a period between late spring and early autumn from Faroe Islands coasts was purchased from a Danish company (DanskTANG, Nykøbing Sj., Denmark). To decide on the feasibility of freeze drying the biomass before extraction, the dry matter of the retained biomass was calculated after vaporization at 102-105 °C for 24 h and the content of dry matter was expressed as (weight) % of the biomass weight. Since the dry matter of the seaweed biomass was 88.2652 ± 0.0075 %, the biomass was freeze-dried using a ScanVac CoolSafe freeze-dryer (LaboGene A/S, Allerod, Denmark) to remove as much moisture as possible. The freeze-dried seaweed biomass was then pulverized using a laboratory mill (KnifeTecTM 1095, Foss Tecator, Hillerød, Denmark). Afterwards, the resulting coarse powder was sieved to obtain finer powder and stored in zip-lock plastic bags at -20 °C.

3.2. Enzymes and Chemicals

Celluclast® 1.5 L and Alcalase® 2.4 L FG were kindly provided by Novozymes A/S (Bagsværd, Denmark). All solvents used were of high-performance, liquid chromatography (HPLC) grade and purchased from Lab-Scan (Dublin, Ireland). Amino acid standards were purchased from Sigma- Aldrich (St. Louis, IL, USA). HPLC grade water was prepared at DTU Food using Milli-Q® Advantage A10 water deionizing system from Millipore Corporation (Billerica, MA, USA). BHT, EDTA, and DPPH were obtained from Sigma–Aldrich (Steinheim, Germany). All other chemicals, such as NaOH and NAC, were obtained from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany).

3.3. Preparation of Enzymatic/Alkaline Extracts

The enzymatic/alkaline extraction from

P. palmata was carried out according to Naseri et al. [

8] with some modifications to ensure achieving the highest possible solubility of resulting proteins, peptides, and amino acids in liquid extracts. Ten Erlenmeyer flasks (treatments in duplicate) containing 4 g of biomass powder and 80 ml of deionized water (1:20 w/v) were placed in water bath at 50 °C for 1 h for biomass rehydration. Afterwards, pH was adjusted to 8 (recommended in [

8] as the most favorable pH for the simultaneous action of enzymes used) using either hydrochloric acid (HCl) or sodium carbonate (Na

2CO

3). Celluclast

® and Alcalase

® were each introduced at the same time at a concentration of 0.2% of biomass weight and enzymatic extraction was performed in water bath at 50 °C for 14 h. Then, the content of each flask was filtered through a sieve (ca. 1 mm mesh size) and the liquid extract was poured into a separate blue-capped bottle and stored at 4 °C. The remaining solid fraction from each flask was re-suspended in 80 ml of the alkaline solution containing 1 g.L

-1 of NAC and 4 g.L

-1 of NaOH and the first round of alkaline extraction was performed on an orbital shaker at 130 rpm and room temperature for 1.5 h. Two more rounds of alkaline extraction were performed using the solid residue from the previous round suspended in fresh alkaline solution. The liquid extracts from all three rounds of alkaline extraction were pooled together with enzymatic extract in each blue-capped bottle and stored at 4 °C overnight. The solid residues after enzymatic/alkaline extraction were dried in an oven at 50 °C and stored at -20 °C before protein content analysis. Next, the pH of enzymatic/alkaline extracts was adjusted to 8.5-9 to ensure the solubility of proteins, peptides, and amino acids. This pH range was found to be efficient to solubilize the protein, peptide, and amino acid content of the extracts because centrifuging (at 4400 g for 15 min at 4 °C) at the end of the whole process yielded almost no solid residues. Ultrasonication was performed after pH adjustment using either an ultrasonic bath (Cole-Parmer 8893, 42 KHz, Illinois, USA) or ultrasound probe (Qsonica XL2000, 22.5 KHz, Connecticut, USA) and the control sample was kept at room temperature when other samples were being ultrasonicated. The treatments were as follows:

Control: enzymatic/alkaline extract without ultrasonication

ULS-B-10: enzymatic/alkaline extract ultrasonicated by bath for 10 minutes.

ULS-B-30: enzymatic/alkaline extract ultrasonicated by bath for 30 minutes.

ULS-P-10: enzymatic/alkaline extract ultrasonicated by probe for 10 minutes.

ULS-P-30: enzymatic/alkaline extract ultrasonicated by probe for 30 minutes.

Then, the extracts were pre-frozen in -20 °C for 2 h and then transferred to -80 °C freezer for 24 h before they were freeze dried (LaboGene A/S, Allerod, Denmark). The resulting powders were transferred to zip-lock plastic bags and stored at -80 °C until analysis. It should be noted that all fractions were weighed using a laboratory balance with readability of 0.01 g at different steps to perform the mass balance calculations.

3.4. Protein Content and Recovery

To measure the protein content of biomass powder, freeze-dried extracts, and oven-dried solid residues collected after enzymatic/alkaline extraction, total nitrogen content of the samples was determined through the DUMAS combustion method using a fully automated rapid MAX N (Elementar Analysensysteme GmbH, Langenselbold, Germany). Approximately 200 mg of samples were fed into the system, and the exact weight was recorded. The protein content was determined by multiplying the nitrogen content by a factor of 5.0 [

8].

Protein recovery in the extracts and solid residues were calculated based on the following equation:

where

MF,

PF,

MS, and

PS stand for mass of the fraction (extract or solid residue), protein percentage of the fraction, mass of the seaweed, and protein percentage of the seaweed, respectively.

3.5. Total Phenolic Content

TPC in the extracts was determined according to [

34]. An aliquot (100 μl) of extract was mixed with 0.75 ml of Folin–Ciocalteu reagent (1:10 diluted) and left at room temperature for 5 min. Sodium bicarbonate (6%, 0.75 ml) was added to the mixture and incubated at room temperature for 90 min. The absorbance was measured at 725 nm using a spectrophotometer (Shimadzu UV mini 1240, Duisburg, Germany). A standard curve was plotted using different concentrations of gallic acid and the amount of total phenolics was calculated as gallic acid equivalents in µg.ml

-1.

3.6. Amino Acid Profile

Approximately 30 mg of the dried sample were hydrolyzed with 6 M HCl at 110 °C for 18 h. Afterwards, the hydrolysates were filtered into 4 ml vials through 0.22 µm cellulose acetate spray filters using 1-ml syringes and then, 100 µl of the filtered hydrolysates were pipetted into 4-ml vials. The pH adjustment was carried out by slowly adding 1.5 ml of 0.2 M KOH to the hydrolysates followed by an additional 1.6 ml of ammonium acetate buffer (100 mM; pH 3.1 adjusted with formic acid) to obtain a dilution factor of 32. The amino acid composition was determined by liquid chromatography using mass spectrometry (Agilent 1260 Infinity II Series, LC/MSD Trap, Agilent technologies, USA) with a BioZen 2.6 µm Glycan, 100 x 2.1 mm (00D-4773-AN) column (Phenomenex, USA) connected to a Quadrupole 6120 MS (Agilent technologies, USA) with an ESI ion source. The following settings were used; a flow rate of 0.5 ml.min-1, a column temperature of 40 °C, 1 µl injection volume, and 16 minutes run time. A gradient mix of two mobile phases A (10 mM ammonium formate in acetonitrile) and B (10 mM ammonium formate in MilliQ water) was used as following: 0-2 min 0-5 % phase B, 2-7 min 5-20 % phase B, 7-8 min 20-80 % phase B, 12.1 min 0 % phase B and 12.1-16 min 0 % phase B. A mix of amino acid standards containing 17 amino acids (not containing glutamine, tryptophan, or asparagine) was run in five different concentrations to make standard curves. Samples were analyzed and amino acids quantitated using MassHunter Quantitative analysis version 7.0 software. Due to the initial hydrolyzation of the samples, the method can’t detect glutamine, asparagine, tryptophan, or cysteine. Glutamine is hydrolyzed into glutamic acid, while asparagine is hydrolyzed into aspartic acid. Tryptophan and cysteine are destroyed during hydrolysis.

3.7. Nitrogen-to-Protein Conversion Factor

Nitrogen-to-protein conversion factors were calculated based on protein content obtained in

Section 3.4 (considering the nitrogen-to-protein factor of 5) and protein content (%) based on total amino acids achieved from

Section 3.5 as followed:

where

Paa and

PD denote protein content (%) based on total amino acids and protein content (%) based on protein content (%) obtained from DUMAS by considering the conversion fact of 5 [

8].

3.8. DPPH Radical Scavenging Activity

DPPH radical scavenging activity was measured according to [

35] modified using microtiter plates and a multiplate reader. The extracts were dissolved in distilled water to acquire solutions with different concentrations. Afterwards, 150 μL of the solution was mixed with 150 μl of 0.1 mM ethanolic solution of DPPH and then kept in the dark at ambient temperature for 30 min. The absorbance was read at 515 nm by an Eon™ microplate spectrophotometer (BioTek Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT, USA). For the blank, distilled water was used instead of the sample. Control was prepared with 150 μl of sample and 150 μl of 95% ethanol. All the measurements were carried out in triplicate. For positive control, BHT solution (0.2 mg.ml

-1) was used. DPPH-scavenging capacity was derived as follows:

where

As,

Ac, and

Ab stand for absorbance of sample, control, and blank, respectively. Furthermore, sample concentrations (mg protein.ml

-1) needed to inhibit 50% of DPPH activity (IC

50 values) were determined by drawing dose response curves.

3.9. Fe2+ Chelating Activity

Fe

2+ chelating activity of the extracts was measured according to [

36] modified using microtiter plates and a multiplate reader. The extracts were dissolved in distilled water to obtain different concentrations. Then, each extract solution (200 μl) was blended with distilled water (270 μl) plus ferrous chloride 2 mM (10 μl). The reaction was blocked after 3 min by using 20 μl of ferrozine solution 5 mM. The mixture was then shaken vigorously. After 10 min at ambient temperature, the absorbance was read at 562 nm by an Eon™ microplate spectrophotometer (BioTek Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT, USA). For the blank, distilled water was used instead of the sample. Sample control was prepared without adding ferrozine. All the measurements were carried out in triplicate. For positive control, 0.06 mM EDTA was used. The metal chelating activity was calculated as follows:

where

As,

Ac, and

Ab stand for absorbance of sample, control, and blank, respectively. Also, sample concentrations (mg protein.ml

-1) needed to chelate 50% of Fe

2+ (IC

50 values) were determined by drawing dose response curves.

3.10. Statistical Analysis

The acquired data were analyzed via Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) and differences between means were determined by Tukey test. All the statistical operations were performed in OriginPro 2023 (OriginLab Co., Northampton, MA, USA). Differences were considered significant at p < 0.05.

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, the previously used nitrogen-to-protein conversion factor of 5 was found to be too high for the extracts, as evidenced by the results obtained regarding the total amino acid compositions as a measure of protein content by accounting for water gained during protein hydrolysis stage. Enzymatic/alkaline extraction in this study facilitated the development of antioxidant extracts from P. palmata. All the extracts generally exhibited favorable radical scavenging and metal chelating activities. Ultrasonication, either by bath or probe, seemed to have no significant effect on degree of hydrolysis and protein recovery in the extracts. According to the results of the study, it is advisable to exert ultrasonication for a short time (e.g., 10 min) by using an ultrasonic bath on the extracts after removing the biomass, because the resulting extract showed significantly higher metal chelating activity than control sample. Consistently, the extract ultrasonicated in bath for the shorter time was the only sample that had no significant difference with control sample in terms of their potency to scavenge free radicals. To top it off, the extract ultrasonicated in bath for the shorter period contained significantly higher content of phenolic compounds compared with the one sonicated the same way but for longer period and with the extracts treated with post-extraction ultrasonication using ultrasound probe. However, the mutual relationships and interactions between phenolic compounds, peptides and amino acids, and other compounds such as carbohydrates should be considered to make more accurate inferences. Overall, according to the results obtained from the present study, treatment of enzymatic/alkaline extracts with ultrasound energy in an ultrasonic bath for a short time could potentially be a new and economical way to improve their bioactivity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.G., A.-D.M.S., and C.J.; methodology, S.G., A.-D.M.S., and C.J.; validation, S.G., ; formal analysis, S.G., ; investigation, S.G., A.-D.M.S., M.H. and C.J.; data curation, S.G., A.-D.M.S., and C.J.; writing— original draft preparation, S.G. and M.H.; writing—review and editing, S.G., A.-D.M.S., M.H. and C.J.; visualization, S.G. and M.H.; supervision, C.J.; project administration, S.G. and C.J.; funding acquisition, S.G. and C.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The project is funded by the European Union under the Horizon Europe grant. The project is part of DOEP, a Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions (MSCA) European Postdoctoral Fellowship Project.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in the article.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the European Union under the Horizon Europe grant as a part of DOEP, a Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions (MSCA) European Postdoctoral Fellowship Project. Susan Løvstad Holdt is thanked for her advice regarding seaweed. The authors also wish to acknowledge Inge Holmberg for technical assistance in the laboratory.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Martínez Leo, E.E.; Martín Ortega, A.M.; Segura Campos, M.R. Bioactive Peptides—Impact in Cancer Therapy. Therapeutic, Probiotic, and Unconventional Foods 2018, 157–166. [CrossRef]

- Hajfathalian, M.; Ghelichi, S.; García-Moreno, P.J.; Moltke Sørensen, A.D.; Jacobsen, C. Peptides: Production, Bioactivity, Functionality, and Applications. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2018, 58, 3097–3129. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Lloréns, J.L.; Critchley, A.T.; Cornish, M.L.; Mouritsen, O.G. Saved by Seaweeds (II): Traditional Knowledge, Home Remedies, Medicine, Surgery, and Pharmacopoeia. J Appl Phycol 2023, 35, 2049–2068. [CrossRef]

- Menaa, F.; Wijesinghe, U.; Thiripuranathar, G.; Althobaiti, N.A.; Albalawi, A.E.; Khan, B.A.; Menaa, B. Marine Algae-Derived Bioactive Compounds: A New Wave of Nanodrugs? Marine Drugs 2021, Vol. 19, Page 484 2021, 19, 484. [CrossRef]

- Dai, N.; Wang, Q.; Xu, B.; Chen, H. Remarkable Natural Biological Resource of Algae for Medical Applications. Front Mar Sci 2022, 9, 912924. [CrossRef]

- Dumay, J.; Cognie, B.; Fleurence, J.; Morançais, M.; Turpin, V.; Gavilan, M.C.; Le Strat, Y.; Decottignies, P. Palmaria Species: From Ecology and Cultivation to Its Use in Food and Health Benefits. Sustainable Global Resources Of Seaweeds Volume 1: Bioresources , cultivation, trade and multifarious applications 2022, 1, 45–61. [CrossRef]

- Mouritsen, O.G.; Dawczynski, C.; Duelund, L.; Jahreis, G.; Vetter, W.; Schröder, M. On the Human Consumption of the Red Seaweed Dulse (Palmaria Palmata (L.) Weber & Mohr). J Appl Phycol 2013, 25, 1777–1791. [CrossRef]

- Naseri, A.; Marinho, G.S.; Holdt, S.L.; Bartela, J.M.; Jacobsen, C. Enzyme-Assisted Extraction and Characterization of Protein from Red Seaweed Palmaria Palmata. Algal Res 2020, 47, 101849. [CrossRef]

- Harnedy, P.A.; FitzGerald, R.J. In Vitro Assessment of the Cardioprotective, Anti-Diabetic and Antioxidant Potential of Palmaria Palmata Protein Hydrolysates. J Appl Phycol 2013, 25, 1793–1803. [CrossRef]

- Harnedy-Rothwell, P.A.; McLaughlin, C.M.; Le Gouic, A. V.; Mullen, C.; Parthsarathy, V.; Allsopp, P.J.; McSorley, E.M.; FitzGerald, R.J.; O’Harte, F.P.M. In Vitro and In Vivo Effects of Palmaria Palmata Derived Peptides on Glucose Metabolism. Int J Pept Res Ther 2021, 27, 1667–1676. [CrossRef]

- Yousof, S.M.; Alghamdi, B.S.; Alqurashi, T.; Alam, M.Z.; Tash, R.; Tanvir, I.; Kaddam, L.A.G. Modulation of Gut Microbiome Community Mitigates Multiple Sclerosis in a Mouse Model: The Promising Role of Palmaria Palmata Alga as a Prebiotic. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 1355. [CrossRef]

- Ghelichi, S.; Sørensen, A.D.M.; García-Moreno, P.J.; Hajfathalian, M.; Jacobsen, C. Physical and Oxidative Stability of Fish Oil-in-Water Emulsions Fortified with Enzymatic Hydrolysates from Common Carp (Cyprinus Carpio) Roe. Food Chem 2017, 237, 1048–1057. [CrossRef]

- Yesiltas, B.; García-Moreno, P.J.; Gregersen, S.; Olsen, T.H.; Jones, N.C.; Hoffmann, S. V.; Marcatili, P.; Overgaard, M.T.; Hansen, E.B.; Jacobsen, C. Antioxidant Peptides Derived from Potato, Seaweed, Microbial and Spinach Proteins: Oxidative Stability of 5% Fish Oil-in-Water Emulsions. Food Chem 2022, 385, 132699. [CrossRef]

- Sabeena Farvin, K.H.; Jacobsen, C. Phenolic Compounds and Antioxidant Activities of Selected Species of Seaweeds from Danish Coast. Food Chem 2013, 138, 1670–1681. [CrossRef]

- Hadidi, M.; Aghababaei, F.; McClements, D.J. Enhanced Alkaline Extraction Techniques for Isolating and Modifying Plant-Based Proteins. Food Hydrocoll 2023, 145, 109132. [CrossRef]

- Lavilla, I.; Bendicho, C. Fundamentals of Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction. Water Extraction of Bioactive Compounds: From Plants to Drug Development 2017, 291–316. [CrossRef]

- Galland-Irmouli, A.V.; Fleurence, J.; Lamghari, R.; Luçon, M.; Rouxel, C.; Barbaroux, O.; Bronowicki, J.P.; Villaume, C.; Guéant, J.L. Nutritional Value of Proteins from Edible Seaweed Palmaria Palmata (Dulse). J Nutr Biochem 1999, 10, 353–359. [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, J.A.; Adams, J.M.M.; Turner, L.B.; Kirby, M.E.; Toop, T.A.; Mirza, M.W.; Theodorou, M.K. Bio-Processing of Macroalgae Palmaria Palmata: Metabolite Fractionation from Pressed Fresh Material and Ensiling Considerations for Long-Term Storage. J Appl Phycol 2021, 33, 533–544. [CrossRef]

- Bjarnadóttir, M.; Aðalbjörnsson, B.V.; Nilsson, A.; Slizyte, R.; Roleda, M.Y.; Hreggviðsson, G.Ó.; Friðjónsson, Ó.H.; Jónsdóttir, R. Palmaria Palmata as an Alternative Protein Source: Enzymatic Protein Extraction, Amino Acid Composition, and Nitrogen-to-Protein Conversion Factor. J Appl Phycol 2018, 30, 2061–2070. [CrossRef]

- Hayes, M. Measuring Protein Content in Food: An Overview of Methods. Foods 2020, Vol. 9, Page 1340 2020, 9, 1340. [CrossRef]

- Tacias-Pascacio, V.G.; Morellon-Sterling, R.; Siar, E.H.; Tavano, O.; Berenguer-Murcia, Á.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R. Use of Alcalase in the Production of Bioactive Peptides: A Review. Int J Biol Macromol 2020, 165, 2143–2196. [CrossRef]

- Derkach, S.R.; Kuchina, Y.A.; Kolotova, D.S.; Petrova, L.A.; Volchenko, V.I.; Glukharev, A.Y.; Grokhovsky, V.A. Properties of Protein Isolates from Marine Hydrobionts Obtained by Isoelectric Solubilisation/Precipitation: Influence of Temperature and Processing Time. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, Vol. 23, Page 14221 2022, 23, 14221. [CrossRef]

- Veide Vilg, J.; Undeland, I. pH-Driven Solubilization and Isoelectric Precipitation of Proteins from the Brown Seaweed Saccharina Latissima—Effects of Osmotic Shock, Water Volume and Temperature. J Appl Phycol 2017, 29, 585–593. [CrossRef]

- Bernardi, S.; Lupatini-Menegotto, A.L.; Kalschne, D.L.; Moraes Flores, É.L.; Bittencourt, P.R.S.; Colla, E.; Canan, C. Ultrasound: A Suitable Technology to Improve the Extraction and Techno-Functional Properties of Vegetable Food Proteins. Plant Foods for Human Nutrition 2021, 76, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Cotas, J.; Leandro, A.; Monteiro, P.; Pacheco, D.; Figueirinha, A.; Goncąlves, A.M.M.; Da Silva, G.J.; Pereira, L. Seaweed Phenolics: From Extraction to Applications. Marine Drugs 2020, Vol. 18, Page 384 2020, 18, 384. [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Jónsdóttir, R.; Kristinsson, H.G.; Hreggvidsson, G.O.; Jónsson, J.Ó.; Thorkelsson, G.; Ólafsdóttir, G. Enzyme-Enhanced Extraction of Antioxidant Ingredients from Red Algae Palmaria Palmata. LWT - Food Science and Technology 2010, 43, 1387–1393. [CrossRef]

- Holeček, M. Histidine in Health and Disease: Metabolism, Physiological Importance, and Use as a Supplement. Nutrients 2020, Vol. 12, Page 848 2020, 12, 848. [CrossRef]

- Mæhre, H.K.; Jensen, I.J.; Eilertsen, K.E. Enzymatic Pre-Treatment Increases the Protein Bioaccessibility and Extractability in Dulse (Palmaria Palmata). Marine Drugs 2016, Vol. 14, Page 196 2016, 14, 196. [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.; Zhao, G.; Tao, L.; Qiu, F.; Wang, S.; Wang, B.; Liu, J.; Duan, S. Antioxidant Interactions between S-Allyl-L-Cysteine and Polyphenols Using Interaction Index and Isobolographic Analysis. Molecules 2022, Vol. 27, Page 4089 2022, 27, 4089. [CrossRef]

- Currell, K. Cysteine and Cystine. Nutritional Supplements in Sport, Exercise and Health: An A-Z Guide 2015, 102–102. [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.; Wang, X.; Song, X.; Sun, R.; Liu, R.; Sui, W.; Jin, Y.; Wu, T.; Zhang, M. Identification of a Novel Walnut Iron Chelating Peptide with Potential High Antioxidant Activity and Analysis of Its Possible Binding Sites. Foods 2023, Vol. 12, Page 226 2023, 12, 226. [CrossRef]

- Sumampouw, G.A.; Jacobsen, C.; Getachew, A.T. Optimization of Phenolic Antioxidants Extraction from Fucus Vesiculosus by Pressurized Liquid Extraction. J Appl Phycol 2021, 33, 1195–1207. [CrossRef]

- Darsih, C.; Indrianingsih, A.W.; Poeloengasih, C.D.; Prasetyo, D.J.; Indirayati, N. In Vitro Antioxidant Activity of Macroalgae Sargassum Duplicatum and Palmaria Palmata Extracts Collected from Sepanjang Beach, Gunungkidul, Yogyakarta. IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng 2021, 1011, 012052. [CrossRef]

- Singleton, V.L.; Rossi, J.A. Colorimetry of Total Phenolics with Phosphomolybdic-Phosphotungstic Acid Reagents. Am J Enol Vitic 1965, 16, 144–158. [CrossRef]

- Shimada, K.; Fujikawa, K.; Yahara, K.; Nakamura, T. Antioxidative Properties of Xanthan on the Autoxidation of Soybean Oil in Cyclodextrin Emulsion. J Agric Food Chem 1992, 40, 945–948. [CrossRef]

- Dinis, T.C.P.; Madeira, V.M.C.; Almeida, L.M. Action of Phenolic Derivatives (Acetaminophen, Salicylate, and 5-Aminosalicylate) as Inhibitors of Membrane Lipid Peroxidation and as Peroxyl Radical Scavengers. Arch Biochem Biophys 1994, 315, 161–169. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).